1. Introduction

Cat cafés are a popular type of coffee or tea shop which allows customers to play with cats that roam freely around the café. The prominent level of cat-cat and human-cat interactions, including the influx of daily customers, may facilitate the transmission of veterinary and zoonotic pathogens. A recent study found that the average number of times cats in a cat café were sick was greater than that of cats in foster care in the same geographic area [

1]. Human cases of giardiasis from the zoonotic agent

Giardia duodenalis have evidence of originating in cat cafés [

2]. Similarly, in China cat cafés are suspected of contributing to the rise of

Pasteurella multocida cases in humans [

3].

Since its initial discovery in China in 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has been the cause of one of the largest pandemics in human history. SARS-CoV-2 has been confirmed to infect a wide variety of mammalian hosts, which is attributed to its entry via the ACE-2 receptor [

4]. Domestic cats may become infected with SARS-CoV-2 through contact with other infected cats, infected humans, or SARS-CoV-2 contaminated environments [

5]. While many infected cats are asymptomatic [

6], some may have display clinical signs similar to human COVID-19 infections, including respiratory distress, coughing, sneezing, fever, nasal discharge, and others [

7]. Among central Texas pets living in houses with confirmed human cases of SARS-CoV-2 early in the pandemic, 43.8% of felines were found to have been infected with the virus [

8]. In rare circumstances, SARS-CoV-2-infected animals have been the source of infection to humans, including an instance of cat to human transmission [

9].

2. Materials and Methods

We quantified the level of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and infection among the feline residents of a new cat café in Brazos County, Texas, which opened in September 2021. The establishment consisted of an approximate 200 ft2 public room with tables, chairs, cat beds, cat trees, and numerous toys and enrichment activities for the cats. To enter the café, customers paid a small fee. The café was open 8 hours daily, 7 days per week, and a range of 40-100 unique customers visited the café daily during the period of our study (café management, personal communication). At the café’s opening, all resident cats were purebred and arrived at the café after being purchased from breeders or other homes. While many of the resident cats from the initial sampling point remained at the café through the last sampling point, several others were added through partnerships with local humane societies and adoption from other homes.

Cats were sampled opportunistically at 4 time periods in 2021-2022, approved by TAMU’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Nasal, oral, rectal, and external body (fur) swabs, immersed into 3 mL viral transport media (VTM; made following CDC SOP#: DSR-052-02), and blood samples were collected. Swabs were tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA using qRT-PCR targeting the RdRp gene. Sera were assayed for SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies using plaque reduction neutralization tests against SARS-CoV-2 Isolate USAIL1/2020, NR 52381 (BEI Resources, Manassas, VA, USA) following methods we previously reported [

10]. Samples which neutralized viral plaques by 50% or more (PRNT

50) were interpreted as seropositive. Those that were able to neutralize viral plaques by 90% or more (PRNT

90) were further tested at 2-fold dilutions, starting at 1:10, to determine 90% endpoint titers.

3. Results

In total, 25 unique cats were sampled across 4 café visits between September 30, 2021, and October 14, 2022, yielding 120 swabs and 40 blood samples in total. All qRT-PCR tests on swabs were negative. Eleven of the 22 cats that were blood-sampled at least once harbored neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 using a PRNT

50 cutoff for a 13-month period prevalence of 50%. Four cats also met PRNT

90 positivity criteria, all of which had endpoint titers of 10 (

Table 1).

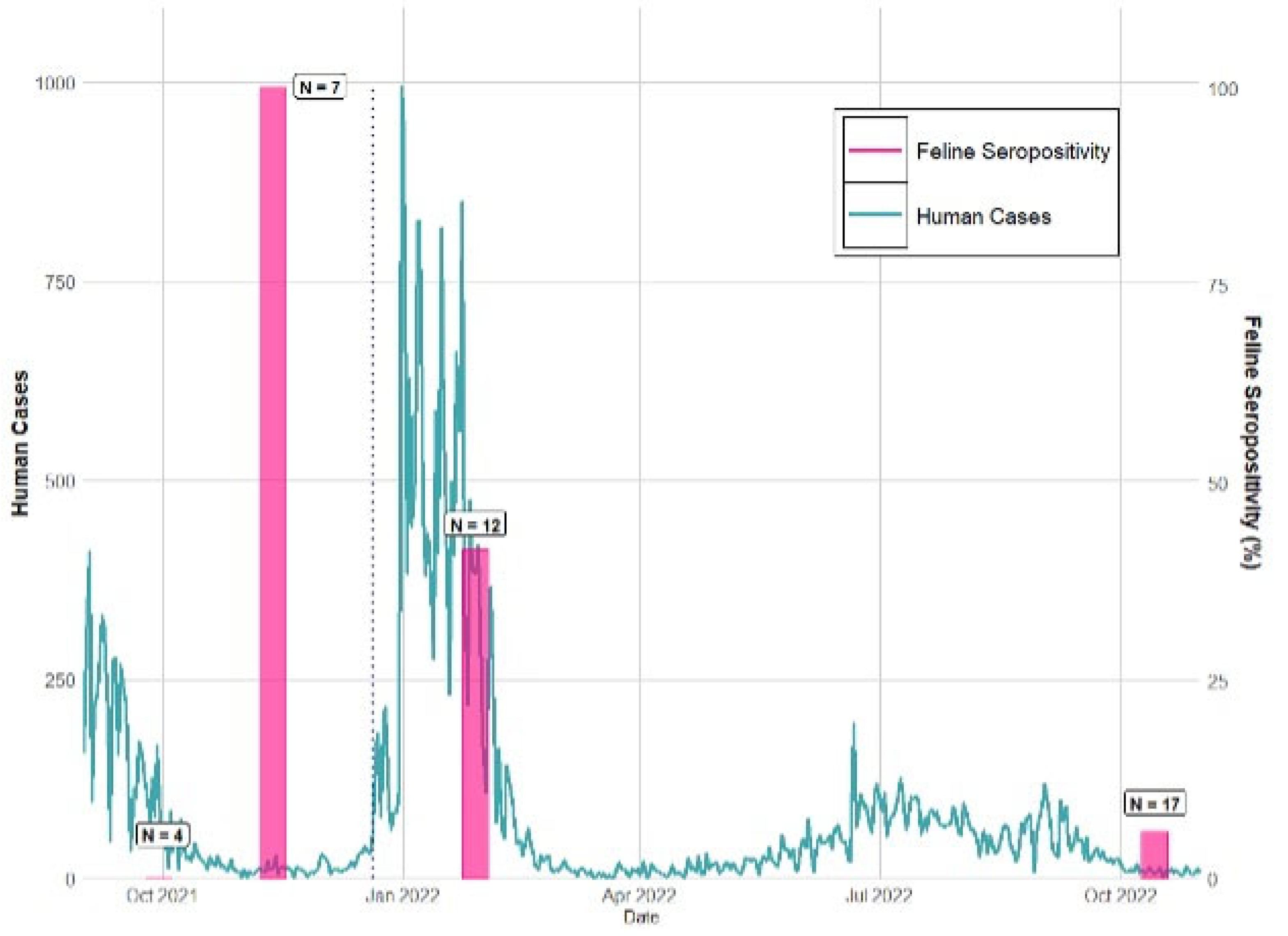

The proportion of cats seropositive varied over time, with a peak of 100% (7 of 7) in November 2021 when Delta was predominant in humans, with lower proportion seropositive in 2022 once Omicron emerged (

Figure 1). Three cats negative on the initial sampling date on Sept 30, 2021- the same month the café opened to the public- were later positive in November 2021, suggesting new infections were acquired between September 30 to early November 2021 when cats likely became accustomed to frequent interactions with customers. On January 28, 2022, 5 of 12 (41.6%) cats were seropositive. The collection took place after the introduction of Omicron to Brazos County, but Delta was still the primary variant circulating at this time (

Figure 1). Four of these 12 cats had been previously sampled in November, including 3 previously seropositive cats that seroreverted to negative, and one cat that remained positive 2.5 months later. Finally, on October 14, 2022- when the Omicron variant was dominant in the human population- only one of the 17 cats tested was seropositive (5.9%), and 7 cats were new to the café and had not been previously sampled. The single seropositive cat was also positive in January 2022, suggesting the retention of neutralizing antibodies at least 8 months or acquisition of a new infection, whereas four previously seropositive cats had reverted to seronegative. Consistent with our findings, prior study showed long-term immunity in domestic cats 3-8 months past the initial positive testing date, [

11], and immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in cats has been shown to protect against re-infection [

12]. Further, the lower proportion of seropositive cats at the end of our study supports experiments showing Omicron is less infectious to felines [

13].

4. Discussion

Studies of pet cats in households with confirmed COVID-19 cases in Texas, Washington, Utah, Idaho, and Ontario, Canada, showed 31%-52% of cats seropositive for SARS-CoV-2, with risk factors for cat infection including sleeping in bed with owners, or being held, pet, and kissed by infected owners [

8,

14,

15]. In contrast, despite the considerable number of human interactions each café cat in our study may have had, the interactions were brief, with most patrons spending only an hour or two at the café, and customers were not allowed to pick up or kiss the cats. This is consistent with research on best practices for human-cat interactions with café cats, which suggest that short, limited touch is ideal for feline comfort in this environment and may have mitigated further SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

The sampling at this café was at the discretion of the café owner. In some cases, the owner requested we not sample specific cats due to behavior or health problems, and so any cat with clinical signs from SARS-CoV-2 infection may not be represented in our sample. This café in Brazos County ultimately closed in February of 2023, citing financial issues. Notably, the café posted that they were dealing with several cases of zoonotic pathogens in the café during the period of our sampling on their social media, including cases of Tritrichomonas foetus, ringworm (Microsporum canis), and Bartonella. Zoonotic disease mitigation should be considered in all cat cafés.

Cat cafés may be high-risk settings for transmission of SARS-CoV-2, with varying patterns of cat infection across different waves of the pandemic. Such residential cats with no or limited travel outside of the café may serve as effective sentinels for the dynamics of transmission in the local human community.

Author Contributions

CD, LDA, and SH collected samples. CD prepared the initial manuscript text. WT and GLH conducted virology studies. CD, GLH and SH provided funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

“Conceptualization, C.D. and S.A.H.; methodology, W.T., G.L.H. and S.A.H.; formal analysis, C.D.; investigation, L.D.A.; C.D.; S.A.H.; and W.T.; resources, G.L.H. and S.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D..; writing—review and editing, C.D., L.D.A., W.T., G.L.H., and S.A.H; supervision, S.A.H; funding acquisition, C.L.D., C.D., S.A.H.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Sigma Xi Grants of Aid in Research [G20221001-4207] and Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Committee on Animal Use and Care (IACUC) with owner consent overseen by the Clinical Research and Review Committee (protocol code IACUC 2018-0460 CA; date of approval February 6, 2019).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank the management of the cat café for allowing our team to sample the animals. We thank Italo Zecca, Rachel Busselman, Ed Davila, and Chris Roundy for assistance with sampling and serologic analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE-2 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| PRNT |

Plaque reduction neutralization test |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| VTM |

Viral transport media |

References

- Ropski, M.K.; Pike, A.L.; Ramezani, N. Analysis of illness and length of stay for cats in a foster-based rescue organization compared with cats housed in a cat café. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 2023, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, J.; et al. Risk of human infection with Giardia duodenalis from cats in Japan and genotyping of the isolates to assess the route of infection in cats. Parasitology 2011, 138, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; et al. Characterization of Resistance and Virulence of Pasteurella multocida Isolated from Pet Cats in South China. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhards, N.M.; et al. Efficient Direct and Limited Environmental Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B. 1.22 in Domestic Cats. Microbiology Spectrum 2023, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault, N.N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, disease and transmission in domestic cats. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9, 2322–2332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liew, A.Y.; et al. Clinical and epidemiologic features of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats compiled through national surveillance in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2023, 261, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamer, S.A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Viral Isolations among Serially Tested Cats and Dogs in Households with Infected Owners in Texas, USA. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sila, T.; et al. Suspected Cat-to-Human Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Thailand, July-September 2021. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roundy, C.M.; et al. High Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) at One of Three Captive Cervid Facilities in Texas. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Decaro, N.; et al. Long-term persistence of neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in pets. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, 69, 3073–3076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bienzle, D.; et al. Risk Factors for SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Illness in Cats and Dogs. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.; et al. The Omicron Variant BA.1.1 Presents a Lower Pathogenicity than B.1 D614G and Delta Variants in a Feline Model of SARS CoV-2 Infection. Journal of Virology 2022, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Meisner, J.; et al. Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from Humans to Pets, Washington and Idaho, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28, 2425–2434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goryoka, G.W.; et al. One Health Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Seropositivity among Pets in Households with Confirmed Human COVID-19 Cases-Utah and Wisconsin, 2020. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).