Introduction

Mental health challenges and political polarization have intensified across many societies, raising questions about how individual psychological traits might interact with ideological divisions. While anxiety and depression are typically examined in clinical terms, and political orientation through sociological or ideological lenses, few studies have empirically explored how these domains intersect. The present research addresses this gap by investigating whether key psychological constructs associated with well-being also relate to political preferences and tolerance for opposing values.

The study focuses on three constructs: locus of control, cognitive flexibility, and tolerance for diverse values. These concepts have held central roles in clinical psychology—particularly within the cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) tradition (Beck, 1976; Ellis, 1962; Meichenbaum, 1985)—yet their broader sociopolitical implications remain underexplored.

Locus of control (LOC) refers to individuals’ beliefs about the causes of life events—whether outcomes stem from personal effort (internal LOC) or external circumstances such as luck or institutional power (external LOC). An internal LOC has been linked to higher self-efficacy, better coping, and reduced distress (Rotter, 1966; Ng et al., 2006), whereas a predominantly external LOC may correlate with helplessness and lower well-being (Levenson, 1974; Seligman, 1975). Emerging findings in political psychology suggest that conservatives may emphasize personal responsibility and agency (i.e., internal LOC), while progressives may emphasize systemic inequality and structural barriers (i.e., external LOC) (Levenson & Miller, 1976; Sweetser, 2014).

Cognitive flexibility, or the ability to generate alternative interpretations and shift one’s thinking, is another key variable. It underpins emotional regulation and therapeutic processes such as reappraisal and cognitive restructuring (Dennis & Vander Wal, 2010; Keng et al., 2011). Higher flexibility is associated with psychological resilience and reduced vulnerability to anxiety and depression (Yu et al., 2019; Johnco et al., 2014). While traditionally examined in clinical settings, it may also influence political reasoning and openness to divergent views.

Tolerance for diverse values refers to individuals’ willingness to engage with beliefs that conflict with their own. This construct connects cognitive and emotional flexibility and may reduce affective polarization and moral rigidity (Moore & Healy, 2008; van Prooijen & Krouwel, 2019). From a CBT perspective, it mirrors mechanisms used in value-based interventions and group therapy to reduce rigid judgment and promote perspective-taking (Meichenbaum, 1985; Beck, 1976).

These three variables are examined in tandem to assess how they relate to both psychological well-being and political attitudes. While prior research often treats them in isolation, this study considers their dynamic interplay. For instance, the ability to tolerate conflicting views may rely on both balanced control beliefs and flexible cognition. Conversely, ideological rigidity may reflect unbalanced LOC orientations and cognitive inflexibility.

An additional aim is to assess whether political orientation itself—beyond its ideological content—is associated with well-being, either directly or through the mediating effects of tolerance, flexibility, and control beliefs. Though not intended as a formal theoretical model, the study is guided by the assumption that recursive feedback loops between cognition, emotion, and sociopolitical identity can shape both mental health and ideological expression.

The study was conducted in Finland, a politically stable Nordic country with relatively low levels of extremism. This moderate context provides a useful test case for evaluating whether psychological variables predict political orientations and value tolerance even in societies where polarization is less intense.

The analysis addresses five central questions: (1) whether individuals’ value preferences and judgments of legitimacy predict openness to ideologically mixed groups; (2) whether tolerance for diverse values differs across the political spectrum; (3) whether locus of control orientations vary by political orientation; (4) whether value tolerance, LOC, and cognitive flexibility predict psychological well-being; and (5) whether political orientation is indirectly linked to well-being through these mediating psychological variables.

Measures and Methods

A total of 136 young Finnish adults aged 18 to 30 (M = 23.99, SD = 3.72; 103 women, 24 men, and 9 identifying as other or preferring not to say) participated in this cross-sectional online study, conducted between March 9 and May 9, 2023. Participants were recruited through multiple channels to ensure sample diversity: youth organizations affiliated with Finnish parliamentary parties were contacted and asked to share the study link with their members, and the questionnaire was further disseminated via social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter.

The survey was available in Finnish, Swedish, and English. All participants gave informed consent prior to participation. Responses were anonymous, no identifying data were collected, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Upon survey completion (15-20 mins), participants received a multilingual debriefing form (FIN, SWE, ENG) outlining the purpose of the study, contact details for the researcher, and links to national mental health support services, including a 24/7 crisis hotline. The study design and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of New Bulgarian University (NBU), Sofia.

Participants first indicated their political orientation on a 7-point left–right scale (Political Position, PP) and then rated the extent to which they agreed with the values of their preferred political party (VOwn) and with those of other major parties (VOth). A derived variable (VDiff) captured the subjective distance between VOwn and VOth. Additionally, participants reported how strongly they preferred being in groups that share similar political values (VGr), which served as a proxy for ideological group preference or openness to value diversity. These variables were designed to reflect subjective perceptions of ideological identity, distance, and inclusion, rather than objective policy knowledge.

Cognitive flexibility was assessed using the “Alternatives” subscale of the Cognitive Flexibility Inventory, which measures an individual's tendency to generate multiple alternative explanations and perspectives in challenging situations. This dimension of flexibility has been linked to adaptive coping, perspective-taking, and reduced rigidity in evaluative thinking. Internal consistency in this sample was high (α = .90).

Locus of control was measured with the Levenson IPC scale, which distinguishes internal control (LOCi), powerful others (LOCp), and chance (LOCc). These subdimensions reflect differing causal attributions and have been shown to predict behavioral orientation, learned helplessness, and affective regulation under uncertainty. Cronbach’s alphas for LOC subscales ranged from .73 to .83 in this sample.

Well-being was assessed using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS), which includes seven items on positive affect, clear thinking, and functioning over the past two weeks. The scale is widely used in both clinical and population-level assessments and has demonstrated robust psychometric properties across cultural contexts. The present sample showed strong reliability (α = .89).

Demographic information was collected on age, gender, education level, and language preference. To reduce priming or order effects, all participants received the same item sequence. The dataset showed non-normal distributions on several key variables (e.g., political distance, well-being), and most items were ordinal in nature. Consequently, all inferential analyses used non-parametric techniques. Kruskal–Wallis H tests examined differences across political orientation groups, while ordinal logistic regression models assessed whether cognitive flexibility and locus of control predicted well-being and group preferences. Bivariate associations were explored through Kendall’s tau-b-rank correlations

All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 29, with alpha set at .05 for significance. Bonferroni corrections were applied to control for multiple comparisons in post-hoc tests.

Known Interactions Among Constructs

Although individual predictors of psychological well-being such as value alignment, cognitive flexibility, and locus of control have been studied extensively in isolation, less attention has been given to how these constructs interact. Emerging evidence suggests that their combined effects may be greater than the sum of their parts, especially in socio-political contexts that challenge identity coherence and cognitive-emotional regulation.

One such interaction occurs between value alignment and cognitive flexibility. When individuals experience high value distance from opposing political groups (VDiff), their psychological response may differ markedly depending on their level of cognitive flexibility (CF). Those with low CF may be more likely to interpret ideological opposition as a threat, reinforcing negative affect and reducing well-being. In contrast, individuals with higher CF can more easily reframe disagreement as a normative feature of pluralistic societies, allowing them to preserve well-being even in the face of strong political divergence. This supports the hypothesis that cognitive flexibility acts as a moderator that buffers the negative psychological impact of value misalignment (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Dennis & Vander Wal, 2010).

Interactions between locus of control and political identity processes also merit attention. For example, a person with a strong internal locus of control (LOCi) may interpret political inefficacy or group disagreement as a call for personal agency or change, rather than as an immutable external condition. Conversely, individuals with high external control beliefs—especially those who score high on powerful others (LOCp)—may be more prone to externalize blame and experience greater psychological distress when encountering opposing values or institutions. These patterns suggest that locus of control modulates how political identity-related stressors are interpreted and emotionally metabolized (Kay et al., 2008; Benassi et al., 1988).

The preference for value-homogeneous groups (VGr) appears to further condition the effects of VDiff. Those who strongly prefer like-minded groups and simultaneously perceive high value distance from others are likely to exhibit stronger affective polarization and a heightened threat response, particularly when cognitive flexibility is low. However, this effect can be attenuated if individuals possess high internal control, allowing them to disengage from affective conflict or focus on constructive coping. The presence of high CF and LOCi in tandem seems to promote more adaptive responses to ideological heterogeneity, whereas the combination of high VDiff, low CF, and high LOCp forms a potential risk cluster for both psychological distress and rigid group identification.

These dynamics echo findings in social-cognitive theory, which posit that the perception of control and the capacity for flexible reinterpretation are central to adaptive functioning under ideological threat (Bandura, 1991; Beck, 2011). Importantly, while constructs like VDiff or LOCp may pose a psychological burden in isolation, their effects are not deterministic; they are modulated by the presence (or absence) of compensatory mechanisms such as CF and LOCi. This multi-dimensional model reflects the complexity of psychological responses to sociopolitical diversity and contributes to a more nuanced understanding of resilience under value conflict.

By exploring these interactions, the present study seeks to move beyond simple correlational models and into a layered framework where constructs operate not in isolation but in tension and synergy. This shift is essential for understanding how value-laden social environments shape individual adaptation and for developing interventions that target not just individual traits, but also their dynamic interrelations.

Results

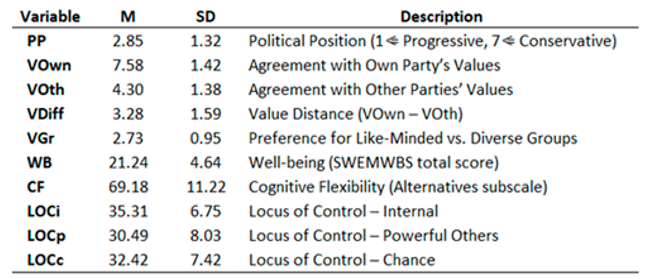

Variable abbreviations with main descriptive statistics are shown in

Table 1. On a scale from 1 (progressive) to 7 (conservative), the mean political orientation (PP) was 2.85 (SD = 1.32), indicating a moderately progressive sample. Notably, no participant selected the maximum value of 7, suggesting an absence of strongly conservative individuals. Agreement with one’s own party’s values (VOwn) was high (M = 7.58, SD = 1.42), whereas agreement with other parties’ values (VOth) was lower (M = 4.30, SD = 1.38), resulting in a moderate perceived value distance (VDiff; M = 3.28, SD = 1.59). Preference for ideologically diverse groups (VGr) was moderate (M = 2.73, SD = 0.95). Cognitive flexibility (CF) was relatively high (M = 69.18, SD = 11.22). Internal locus of control (LOCi; M = 35.31, SD = 6.75) was higher on average than powerful others (LOCp; M = 30.49, SD = 8.03) and chance locus of control (LOCc; M = 32.42, SD = 7.42). Well-being (WB), measured using the SWEMWBS, had a mean of 21.24 (SD = 4.64).

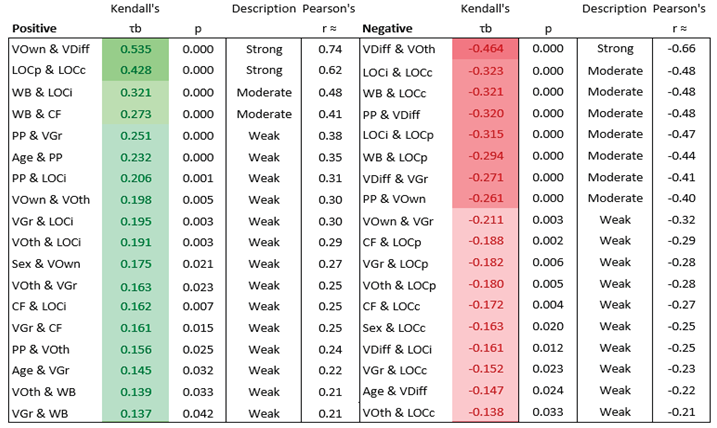

Kendall’s tau-b correlational analyses (ranked in

Table 2) revealed several significant and theoretically relevant associations. The strongest positive correlation was between VOwn and VDiff (τ = .535, p < .001), indicating that stronger endorsement of one’s own party values was associated with greater perceived distance from other parties’ values. A strong negative association was observed between VDiff and VOth (τ = −.464, p < .001).

Well-being (WB) was positively associated with internal locus of control (LOCi; τ = .321, p < .001) and cognitive flexibility (CF; τ = .273, p < .001), but negatively associated with powerful others (LOCp; τ = −.294, p < .001) and chance locus of control (LOCc; τ = −.552, p < .001).

Political orientation (PP) was positively associated with preference for ideologically diverse groups (VGr; τ = .251, p < .001), agreement with other parties’ values (VOth; τ = .156, p = .025), and internal locus of control (LOCi; τ = .206, p = .001). PP was negatively associated with VOwn (τ = −.261, p < .001) and VDiff (τ = −.320, p < .001). These patterns suggest that more conservative orientations in this sample were linked to greater ideological openness, lower own-party exclusivity, smaller perceived value gaps, and stronger internal control beliefs.

VOth and VGr were both positively associated with LOCi (τ = .191, p = .003 and τ = .195, p = .003, respectively) and showed negative associations with external locus dimensions. VGr was also positively related to CF (τ = .161, p = .015).

Ordinal regression analyses (95% CI, 1000 bootstrap samples) further supported the hypotheses. Models predicting VGr were significant: one with VOwn and VOth (χ²(15) = 38.02, p = .001; explained variance 10.4%–26.2%) and another with VDiff (χ²(9) = 25.55, p = .002; explained variance 7.0%–18.4%), with directions consistent with correlations.

Models predicting PP were significant: one with VOwn, VOth, and VGr (χ²(20) = 50.32, p < .001; explained variance 11.5%–32.2%) and another with VDiff and VGr (χ²(14) = 56.00, p < .001; explained variance 12.8%–35.2%). Greater value tolerance predicted more conservative orientation. A model predicting LOCi from PP was significant (χ²(28) = 47.14, p = .013; explained variance 10.8%–30.5%).

Models predicting WB showed strong effects: one with VOth, VGr, LOCi, LOCp, and LOCc (χ²(104) = 356.44, p < .001; explained variance 46.3%–93.0%), primarily driven by LOC variables; and another with CF, VOth, and VGr (χ²(53) = 71.76, p = .044; explained variance 9.3%–41.1%), with CF as a key positive predictor.

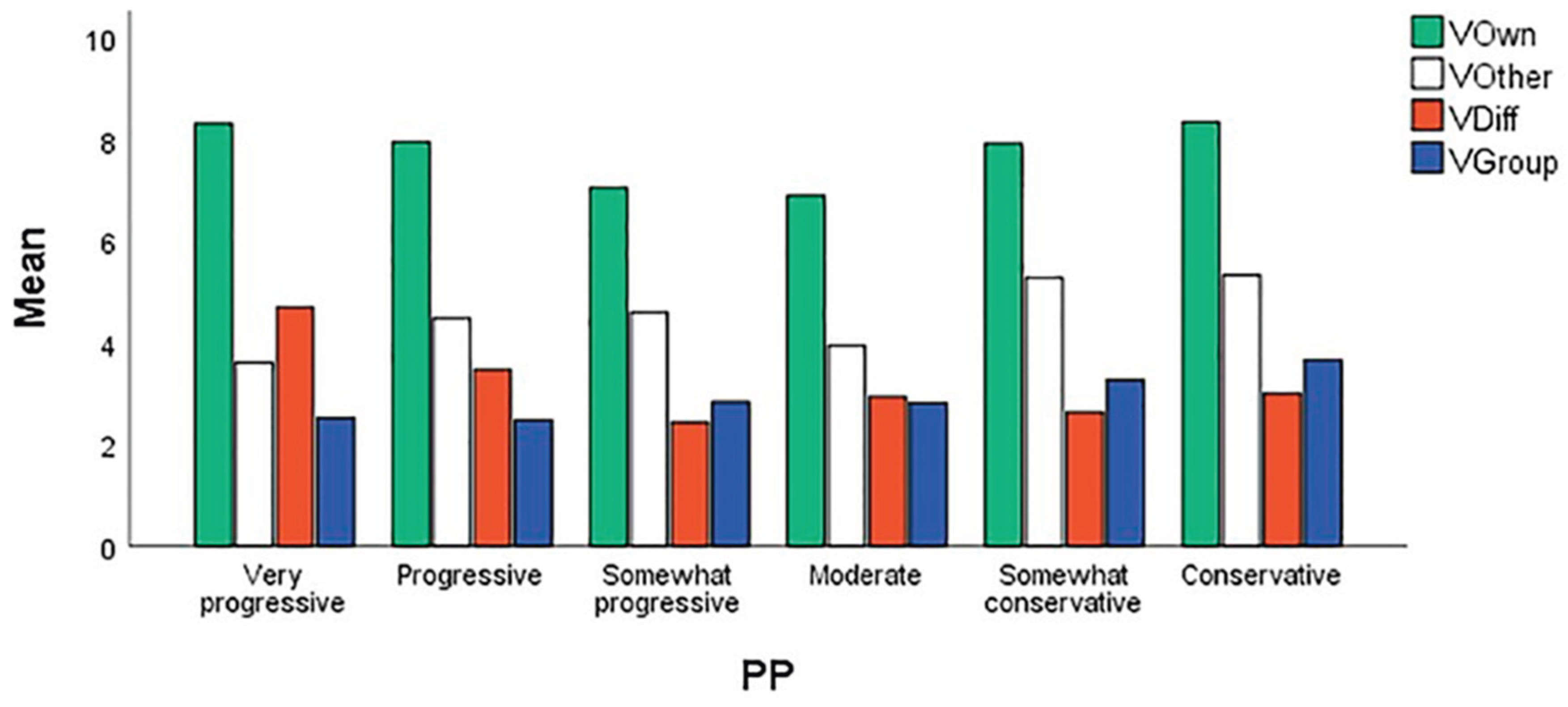

Non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests confirmed significant group differences across political orientation levels for VDiff, VOth, VGroup, and LOCi (all ps < .05 in original analyses). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that more conservative participants exhibited lower VDiff, higher VOth, higher VGroup, and higher LOCi relative to progressive participants. These group-level trends are visualized in

Figure 1, which illustrates how openness indicators and perceived value distance vary across political identities.

In summary, well-being was robustly linked to internal locus of control and cognitive flexibility. Indicators of ideological openness (higher VOth and VGr, lower VDiff) and internal control were more strongly associated with conservative orientation in this moderately progressive sample.

Discussion

The present study investigated the interplay between political orientation, tolerance for diverse values, locus of control, cognitive flexibility, and psychological well-being in a sample of young Finnish adults. The findings reveal consistent patterns that both align with established psychological principles and challenge certain assumptions in political psychology.

Well-being was most robustly associated with internal locus of control and cognitive flexibility. Higher internal locus of control (LOCi) and greater cognitive flexibility (CF) were linked to elevated well-being, whereas external locus dimensions—particularly chance (LOCc) and powerful others (LOCp)—showed negative associations. These results are consistent with extensive prior research emphasizing the role of perceived personal agency (Rotter, 1966; Levenson, 1974) and adaptive cognitive processing (Dennis & Vander Wal, 2010; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010) in promoting resilience, positive affect, and overall mental health. Ordinal regression models further underscored the predictive strength of these constructs, with locus of control variables explaining a substantial portion of variance in well-being.

A notable finding was the positive association between conservative political orientation and internal locus of control. More conservative participants (higher PP scores) reported stronger beliefs in personal agency, a pattern that emerged in both correlations and regression analyses. This aligns with theoretical perspectives linking conservatism to emphasis on personal responsibility (Sweetser, 2014) and extends earlier observations that internal control beliefs may vary across the ideological spectrum (Levenson & Miller, 1976).

Perhaps the most intriguing results concern indicators of ideological openness and tolerance. In this sample, more conservative orientation was associated with greater agreement with other parties’ values (VOth), stronger preference for ideologically diverse groups (VGr), and lower perceived value distance (VDiff). Conversely, progressive orientation correlated with higher own-party endorsement (VOwn) and greater perceived distance from others. These patterns were evident across bivariate correlations, ordinal regressions, and non-parametric group comparisons.

Although counter to some narratives portraying conservatism as inherently rigid or threat-sensitive (Jost et al., 2003), the findings resonate with growing evidence of ideological symmetry in dogmatism and affective polarization (Brandt et al., 2014; Baron & Jost, 2019). They suggest that intolerance or exclusivity can manifest on either side of the spectrum, influenced by contextual factors such as generational norms, cultural setting, or sample composition.

The moderately progressive skew of the sample—and the complete absence of strongly conservative identifiers (no PP = 7)—warrants caution in generalizing these patterns. Finland’s stable, low-polarisation political environment and the young adult cohort may contribute to these results. In such contexts, progressive identification might be more tied to strong in-group alignment, while conservative views could foster greater openness or perspective-taking as an adaptive strategy.

The interplay among constructs also highlights potential buffering mechanisms. Ideological openness (higher VOth and VGr) was positively linked to internal control and cognitive flexibility, suggesting that these psychological resources may facilitate tolerance for differing values. This supports cognitive-behavioral frameworks where flexible reinterpretation and agency beliefs mitigate threat responses to worldview conflict (Beck, 2011; Meichenbaum, 1985).

Overall, the study demonstrates that key predictors of well-being—internal locus of control and cognitive flexibility—are not uniformly distributed across the political spectrum but can cluster in context-specific ways. The findings underscore the value of examining political orientation alongside broader psychological traits, rather than isolating ideological content. They also caution against overgeneralizing stereotypes of ideological rigidity, which appear more symmetric and contingent than often assumed.

Practically, these results suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing well-being or reducing polarization might prioritize fostering internal agency and cognitive adaptability over directly targeting political beliefs. Such approaches could prove effective across ideological lines, promoting resilience in increasingly diverse societies.

Future research should replicate these patterns in more ideologically balanced samples, incorporate longitudinal designs to clarify directionality, and explore cultural variations to determine the extent to which these associations reflect universal psychological processes versus local sociopolitical dynamics.

Conclusions

Our study revealed a pattern of psychological dynamics that seem to resist common ideological stereotypes. Rather than finding conservatives to be more rigid or polarized, the data showed that it was the progressive participants who reported stronger alignment with their own political group, less appreciation for ideological outgroups, and greater perceived distance between their values and those of others. These findings challenge widely held assumptions in psychological science about the structure of political cognition and suggest that ideological openness may not map linearly onto traditional left–right divisions.

Instead, the results point to a more nuanced architecture in which psychological traits—particularly internal locus of control and cognitive flexibility—shape not only individual well-being, but also political tolerance and perceived ideological distance. Internal control beliefs emerged as a particularly robust predictor of well-being, reinforcing longstanding evidence that a sense of agency is central to mental health. Cognitive flexibility, while a weaker predictor of well-being than internal locus of control, nevertheless showed a significant and consistent relationship with ideological openness, hinting at its role in moderating polarization and fostering dialogue. Yet neither cognitive flexibility nor political openness were tied exclusively to one ideological position, further underscoring the contextual and generational specificity of these dynamics.

Taken together, the findings highlight the value of studying political identity not in isolation, but in conjunction with broader cognitive and emotional traits. They suggest that polarization may often reflect not immutable ideological divides, but underlying psychological configurations shaped by generational context, perceived social norms, and asymmetries in voice or status. This insight opens the door for interventions that do not attempt to shift political positions, but rather aim to strengthen personal agency, metacognitive awareness, and the capacity to tolerate or integrate conflicting perspectives.

As the boundaries between political identity and psychological health continue to blur—especially among younger generations—research that bridges these domains becomes increasingly important. This study contributes to that bridge by showing that individual well-being is not only a matter of personal beliefs or traits, but also of how one relates to the values of others, and how flexible or fixed those relationships become over time. Future research can build on this foundation by exploring how these patterns unfold across cultures, age groups, and political climates, and by developing tools that help individuals navigate ideological complexity without compromising psychological well-being.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the sample was not fully representative of the broader population, particularly in terms of political orientation. Although the scale ranged from 1 (progressive) to 7 (conservative), no participants selected the highest value, indicating a lack of respondents with strong conservative identification. This restriction may have narrowed the ideological spectrum and potentially influenced the distribution of tolerance and rigidity measures. Future studies should aim to include more politically diverse samples to allow for clearer comparisons across the full range of ideological positions.

Second, all measures relied on self-report instruments, which are inherently subject to biases such as social desirability and self-perception distortions. While the study controlled for acquiescence in the political value alignment scales and used established instruments for locus of control, cognitive flexibility, and well-being, these methods cannot fully eliminate subjective framing or situational influences on responses.

Third, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to infer causality. Although regression analyses suggested directional patterns—such as internal locus of control predicting well-being or political orientation—these findings remain correlational. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether psychological traits like internal control or flexibility precede changes in political openness, or whether shifts in social or ideological context shape these traits over time.

Finally, the cultural and generational context of the participants likely shaped both the expression and interpretation of political identity. What counts as “conservative” or “progressive” may vary significantly across societies and age groups.

References

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. [CrossRef]

- Baron, J., & Jost, J. T. (2019). False equivalence: Are liberals and conservatives in the United States equally biased? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(2), 292–303. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Benassi, V. A., Sweeney, P. D., & Dufour, C. L. (1988). Is there a relation between locus of control orientation and depression? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(3), 357–367. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, M. J., Reyna, C., Chambers, J. R.,Crawford, J. T., & Wetherell, G. (2014). The ideological-conflict hypothesis: Intolerance among both liberals and conservatives. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J. P., & Vander Wal, J. S. (2010). The Cognitive Flexibility Inventory: Instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(3), 241–253. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Lyle Stuart.

- Johnco, C., Wuthrich, V. M., & Rapee, R. M. (2014). The influence of cognitive flexibility on treatment outcome and cognitive restructuring skill acquisition during cognitive behavioural treatment for anxiety and depression in older adults: Results of a pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339–375. [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. [CrossRef]

- Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Napier, J. L., Callan, M. J., & Laurin, K. (2008). God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 18–35. [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. [CrossRef]

- Levenson, H. (1974). Activism and powerful others: Distinctions within the concept of internal-external control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 38(4), 377–383. [CrossRef]

- Levenson, H., & Miller, J. (1976). Multidimensional locus of control in sociopolitical activists of conservative and liberal ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33(2), 199–208. [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. M., & Rubin, R. B. (1995). A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychological Reports, 76(2), 623–626. [CrossRef]

- Meichenbaum, D. (1985). Stress inoculation training. Pergamon Press.

- Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502–517. [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W. H., Sorensen, K. L., & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1057–1087. [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. W. H. Freeman.

- Sweetser, K. D. (2014). Partisan personality: The psychological differences between Democrats and Republicans, and independents somewhere in between. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(9), 1183–1196. [CrossRef]

- van Prooijen, J.-W., & Krouwel, A. P. M. (2019). Psychological features of extreme political ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 159–163. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Yu, Y., & Lin, Y. (2019). Anxiety and depression aggravate impulsiveness: The mediating and moderating role of cognitive flexibility. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 25(1), 25–36. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |