Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

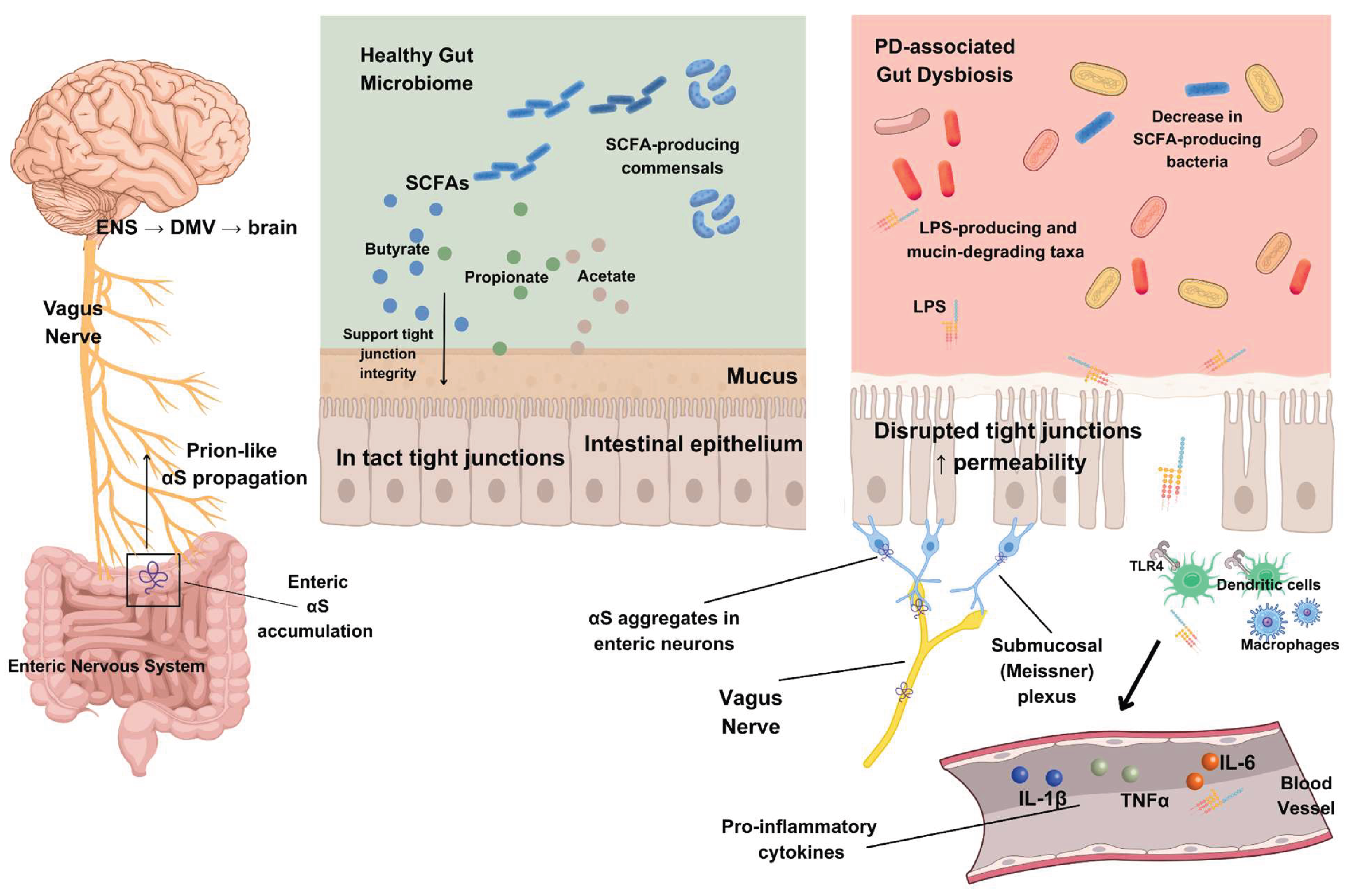

2. Gut-Brain Framework: ENS, Braak Hypothesis and αS Spread

2.1. The ENS and the Gut-Brain Axis

2.2. The Braak Hypothesis

2.3. Experimental Evidence for Prion-Like αS Propagation

3. Future Directions in Enteric αS Imaging

4. Barriers, Immunity, and Neurodegeneration Along the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

4.1. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, Lipopolysaccharide Signaling, and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption

4.2. Microglial Activation and αS-LPS Crosstalk

4.3. Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Selective Nigral Vulnerability

5. Gut Microbiome and Microbial Metabolites in PD

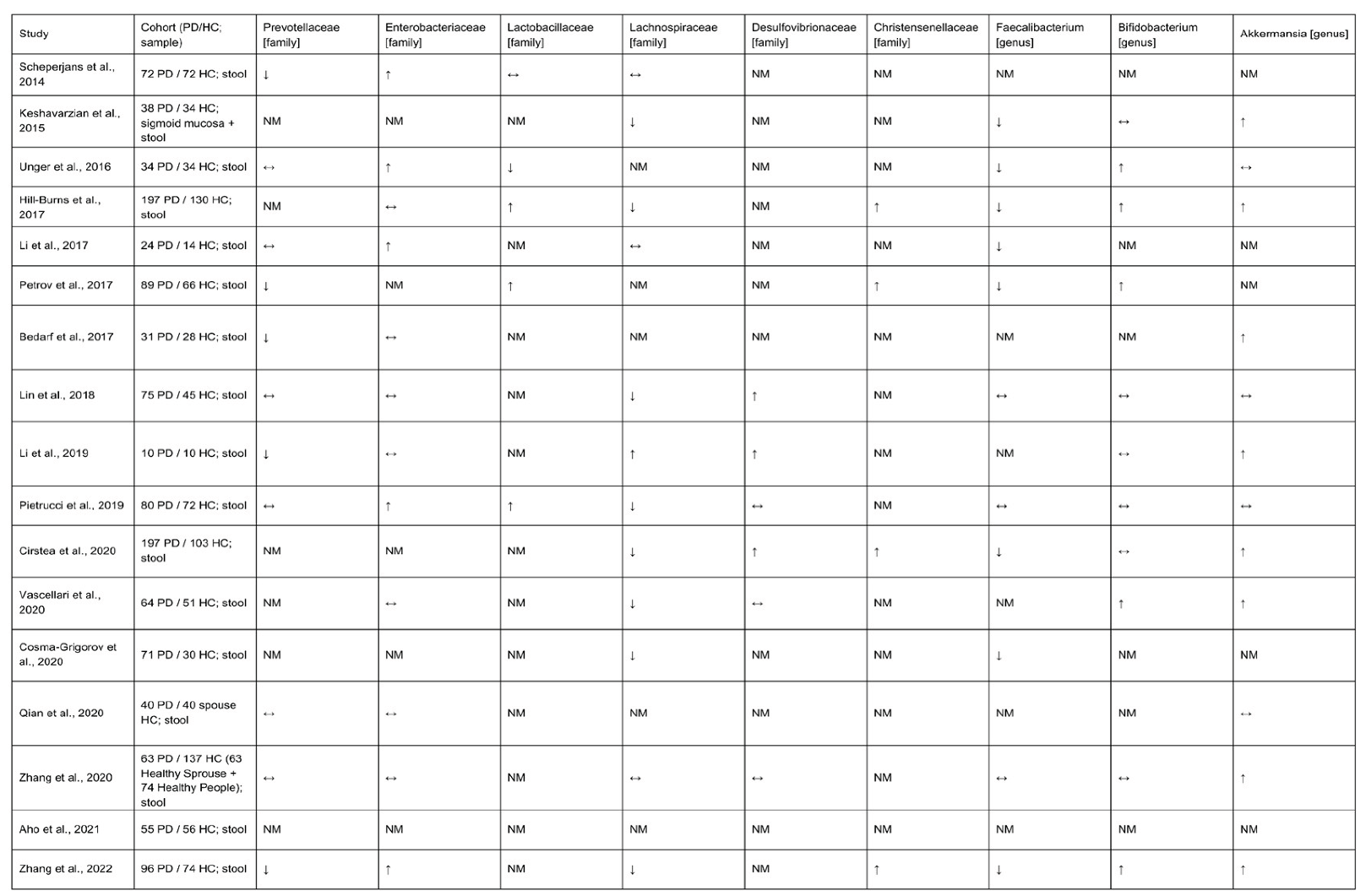

5.1. Gut Microbiome Composition in PD

5.2. Future Directions: Longitudinal Microbiome Cohorts

5.3. Short Chain Fatty Acids in Microbiota-Gut-Brain Mechanisms

5.4. Mucin-Degrading Taxa and αS Aggregation

6. Therapeutic Implications Along the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

6.1. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

6.2. Antibiotic Modulation: Rifaximin

6.3. Probiotic, Prebiotic and Synbiotic Approaches

7. Conclusions

References

- Kalia, L. V.; Lang, A. E. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet 2015, 386(9996), 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizek, P.; Kumar, N.; Jog, M. S. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2016, 188(16), 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Ye, X.; Huang, Z.; Ye, L.; Chen, C. Global burden of Parkinson’s disease from 1990 to 2021: a population-based study. BMJ Open 2025, 15(4), e095610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Cui, Y.; He, C.; Yin, P.; Bai, R.; Zhu, J.; Lam, J. S. T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Zheng, X.; Wu, J.; Zhao, D.; Wang, A.; Zhou, M.; Feng, T. Projections for prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: modelling study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ 2025, 388, e080952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeso, J. A.; Stamelou, M.; Goetz, C. G.; Poewe, W.; Lang, A. E.; Weintraub, D.; Burn, D.; Halliday, G. M.; Bezard, E.; Przedborski, S.; Lehericy, S.; Brooks, D. J.; Rothwell, J. C.; Hallett, M.; DeLong; Marras, C.; Tanner, C. M.; Ross, G. W.; Langston, J. W.; Klein, C.; Bonifati, V.; Jankovic, J.; Lozano, A. M.; Deuschl, G.; Bergman, H.; Tolosa, E.; Rodriguez-Violante, M.; Fahn, S.; Postuma, R. B.; Berg, D.; Marek, K.; Standaert, D. G.; Surmeier, D. J.; Olanow, C. W.; Kordower, J. H.; Calabresi, P.; Schapira, A. H. V.; Stoessl, A. J. Past, present, and future of Parkinson’s disease: A special essay on the 200th Anniversary of the Shaking Palsy. Movement Disorders 2017, 32(9), 1264–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E.; Compta, Y.; Gaig, C. The premotor phase of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2007, 13, S2–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeropoulos, M. H.; Lavedan, C.; Leroy, E.; Ide, S. E.; Dehejia, A.; Dutra, A.; Pike, B.; Root, H.; Rubenstein, J.; Boyer, R.; Stenroos, E. S.; Chandrasekharappa, S.; Athanassiadou, A.; Papapetropoulos, T.; Johnson, W. G.; Lazzarini, A. M.; Duvoisin, R. C.; Di Iorio, G.; Golbe, L. I.; Nussbaum, R. L. Mutation in the α-Synuclein Gene Identified in Families with Parkinson’s Disease. Science 1997, 276(5321), 2045–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M. G.; Crowther, R. A.; Jakes, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Goedert, M. α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95(11), 6469–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarthing, K.; Buff, S.; Rafaloff, G.; Pitzer, K.; Fiske, B.; Navangul, A.; Beissert, K.; Pilcicka, A.; Fuest, R.; Wyse, R. K.; Stott, S. R. W. Parkinson’s Disease Drug therapies in the clinical Trial pipeline: 2024 update. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2024, 14(5), 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 2001, 2(7), 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanis, L. -Synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2012, 2(2), a009399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, R.; Kling, K.; Anderson, J. P.; Banducci, K.; Cole, T.; Diep, L.; Fox, M.; Goldstein, J. M.; Soriano, F.; Seubert, P.; Chilcote, T. J. Red blood cells are the major source of Alpha-Synuclein in blood. Neurodegenerative Diseases 2008, 5(2), 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D. D.; Rueter, S. M.; Trojanowski, J. Q.; Lee, V. M. -y. Synucleins are developmentally expressed, and A-Synuclein regulates the size of the presynaptic vesicular pool in primary hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 20(9), 3214–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuscher, B.; Kamp, F.; Mehnert, T.; Odoy, S.; Haass, C.; Kahle, P. J.; Beyer, K. A-Synuclein has a high affinity for packing defects in a bilayer membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279(21), 21966–21975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendor, J. T.; Logan, T. P.; Edwards, R. H. The function of A-Synuclein. Neuron 2013, 79(6), 1044–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P. H.; Nielsen, M. S.; Jakes, R.; Dotti, C. G.; Goedert, M. Binding of A-Synuclein to brain vesicles is abolished by familial Parkinson’s disease mutation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273(41), 26292–26294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Gershon, M. D. The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2016, 13(9), 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M. D.; Margolis, K. G. The gut, its microbiome, and the brain: connections and communications. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2021, 131(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M. A.; Ehsan, L.; Moore, S. R.; Levin, D. E. The enteric nervous system and its emerging role as a therapeutic target. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, S.; Lomis, N.; Kahouli, I.; Dia, S. Y.; Singh, S. P.; Prakash, S. Microbiome, probiotics and neurodegenerative diseases: deciphering the gut brain axis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017, 74(20), 3769–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L. M. T. Gut bacteria and neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022, 10(9), 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Rüb, U.; Gai, W. P.; Del Tredici, K. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. Journal of Neural Transmission 2003, 110(5), 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K.; Rüb, U.; De Vos, R. A. I.; Steur, E. N. H. J.; Braak, E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging 2002, 24(2), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; De Vos, R. A. I.; Bohl, J.; Del Tredici, K. Gastric α-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neuroscience Letters 2005, 396(1), 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. J.; Wypych, J.; Steavenson, S.; Louis, J.-C.; Citron, M.; Biere, A. L. A-Synuclein fibrillogenesis is nucleation-dependent. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274(28), 19509–19512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, K. C.; Kehm, V. M.; Zhang, B.; O’Brien, P.; Trojanowski, J. Q.; Lee, V. M. Y. Intracerebral inoculation of pathological α-synuclein initiates a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative α-synucleinopathy in mice. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2012a, 209(5), 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, K. C.; Kehm, V.; Carroll, J.; Zhang, B.; O’Brien, P.; Trojanowski, J. Q.; Lee, V. M. -y. Pathological A-Synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 2012b, 338(6109), 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peelaerts, W.; Bousset, L.; Van Der Perren, A.; Moskalyuk, A.; Pulizzi, R.; Giugliano, M.; Van Den Haute, C.; Melki, R.; Baekelandt, V. α-Synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature 2015, 522(7556), 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recasens, A.; Dehay, B.; Bové, J.; Carballo-Carbajal, I.; Dovero, S.; Pérez-Villalba, A.; Fernagut, P.; Blesa, J.; Parent, A.; Perier, C.; Fariñas, I.; Obeso, J. A.; Bezard, E.; Vila, M. Lewy body extracts from Parkinson disease brains trigger α-synuclein pathology and neurodegeneration in mice and monkeys. Annals of Neurology 2014, 75(3), 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J. C.; Giles, K.; Oehler, A.; Middleton, L.; Dexter, D. T.; Gentleman, S. M.; DeArmond, S. J.; Prusiner, S. B. Transmission of multiple system atrophy prions to transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110(48), 19555–19560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Nonaka, T.; Hosokawa, M.; Oikawa, T.; Arai, T.; Akiyama, H.; Mann, D. M. A.; Hasegawa, M. Prion-like spreading of pathological α-synuclein in brain. Brain 2013, 136(4), 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paumier, K. L.; Luk, K. C.; Manfredsson, F. P.; Kanaan, N. M.; Lipton, J. W.; Collier, T. J.; Steece-Collier, K.; Kemp, C. J.; Celano, S.; Schulz, E.; Sandoval, I. M.; Fleming, S.; Dirr, E.; Polinski, N. K.; Trojanowski, J. Q.; Lee, V. M.; Sortwell, C. E. Intrastriatal injection of pre-formed mouse α-synuclein fibrils into rats triggers α-synuclein pathology and bilateral nigrostriatal degeneration. Neurobiology of Disease 2015, 82, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-Y.; Englund, E.; Holton, J. L.; Soulet, D.; Hagell, P.; Lees, A. J.; Lashley, T.; Quinn, N. P.; Rehncrona, S.; Björklund, A.; Widner, H.; Revesz, T.; Lindvall, O.; Brundin, P. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nature Medicine 2008, 14(5), 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordower, J. H.; Chu, Y.; Hauser, R. A.; Freeman, T. B.; Olanow, C. W. Lewy body–like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease. Nature Medicine 2008, 14(5), 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan-Montojo, F.; Schwarz, M.; Winkler, C.; Arnhold, M.; O’Sullivan, G. A.; Pal, A.; Said, J.; Marsico, G.; Verbavatz, J.-M.; Rodrigo-Angulo, M.; Gille, G.; Funk, R. H. W.; Reichmann, H. Environmental toxins trigger PD-like progression via increased alpha-synuclein release from enteric neurons in mice. Scientific Reports 2012, 2(1), 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, S.; Chutna, O.; Bousset, L.; Aldrin-Kirk, P.; Li, W.; Björklund, T.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Roybon, L.; Melki, R.; Li, J.-Y. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathologica 2014, 128(6), 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, S.-H.; Kam, T.-I.; Panicker, N.; Karuppagounder, S. S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, W. R.; Kook, M.; Foss, C. A.; Shen, C.; Lee, H.; Kulkarni, S.; Pasricha, P. J.; Lee, G.; Pomper, M. G.; Dawson, V. L.; Dawson, T. M.; Ko, H. S. Transneuronal Propagation of Pathologic α-Synuclein from the Gut to the Brain Models Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103(4), 627–641.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, N.; Yagi, H.; Uemura, M. T.; Hatanaka, Y.; Yamakado, H.; Takahashi, R. Inoculation of α-synuclein preformed fibrils into the mouse gastrointestinal tract induces Lewy body-like aggregates in the brainstem via the vagus nerve. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2018, 13(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, C.; Hori, A.; Sampson, T. R.; Yoo, B. B.; Challis, R. C.; Hamilton, A. M.; Mazmanian, S. K.; Volpicelli-Daley, L. A.; Gradinaru, V. Gut-seeded α-synuclein fibrils promote gut dysfunction and brain pathology specifically in aged mice. Nature Neuroscience 2020, 23(3), 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, N.; Yagi, H.; Uemura, M. T.; Yamakado, H.; Takahashi, R. Limited spread of pathology within the brainstem of α-synuclein BAC transgenic mice inoculated with preformed fibrils into the gastrointestinal tract. Neuroscience Letters 2019, 716, 134651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, E.; Horváth-Puhó, E.; Thomsen, R. W.; Djurhuus, J. C.; Pedersen, L.; Borghammer, P.; Sørensen, H. T. Vagotomy and subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology 2015, 78(4), 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Fang, F.; Pedersen, N. L.; Tillander, A.; Ludvigsson, J. F.; Ekbom, A.; Svenningsson, P.; Chen, H.; Wirdefeldt, K. Vagotomy and Parkinson disease. Neurology 2017, 88(21), 1996–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, T. G.; Adler, C. H.; Sue, L. I.; Vedders, L.; Lue, L.; White, C. L., III; Akiyama, H.; Caviness, J. N.; Shill, H. A.; Sabbagh, M. N.; Walker, D. G. Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated α-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathologica 2010, 119(6), 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanei, Z.-I.; Saito, Y.; Ito, S.; Matsubara, T.; Motoda, A.; Yamazaki, M.; Sakashita, Y.; Kawakami, I.; Ikemura, M.; Tanaka, S.; Sengoku, R.; Arai, T.; Murayama, S. Lewy pathology of the esophagus correlates with the progression of Lewy body disease: a Japanese cohort study of autopsy cases. Acta Neuropathologica 2020, 141(1), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annerino, D. M.; Arshad, S.; Taylor, G. M.; Adler, C. H.; Beach, T. G.; Greene, J. G. Parkinson’s disease is not associated with gastrointestinal myenteric ganglion neuron loss. Acta Neuropathologica 2012, 124(5), 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlsson, B.; Englund, E. Atrophic myenteric and submucosal neurons are observed in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson S Disease 2019, 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebouvier, T.; Chaumette, T.; Damier, P.; Coron, E.; Touchefeu, Y.; Vrignaud, S.; Naveilhan, P.; Galmiche, J.; Varannes, S. B. D.; Derkinderen, P.; Neunlist, M. Pathological lesions in colonic biopsies during Parkinson’s disease. Gut 2008, 57(12), 1741–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebouvier, T.; Neunlist, M.; Varannes, S. B. D.; Coron, E.; Drouard, A.; N’Guyen, J.-M.; Chaumette, T.; Tasselli, M.; Paillusson, S.; Flamand, M.; Galmiche, J.-P.; Damier, P.; Derkinderen, P. Colonic Biopsies to Assess the Neuropathology of Parkinson’s Disease and Its Relationship with Symptoms. PLoS ONE 2010, 5(9), e12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokholm, M. G.; Danielsen, E. H.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S. J.; Borghammer, P. Pathological α-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Annals of Neurology 2016, 79(6), 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmer, U.; Newman, A. J.; Luth, E. S.; Bartels, T.; Selkoe, D. In vivo cross-linking reveals principally oligomeric forms of A-Synuclein and Β-Synuclein in neurons and non-neural cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288(9), 6371–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbillé, A.; Neunlist, M.; Derkinderen, P. Cross-linking for the analysis of α-synuclein in the enteric nervous system. Journal of Neurochemistry 2016, 139(5), 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R. J.; Walter, G. C.; Wilder, S. L.; Baronowsky, E. A.; Powley, T. L. Alpha-synuclein-immunopositive myenteric neurons and vagal preganglionic terminals: Autonomic pathway implicated in Parkinson’s disease? Neuroscience 2008, 153(3), 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghool, O. M.; Van Dongen, G.; Van De Giessen, E.; Schoonmade, L.; Beaino, W. A-Synuclein Radiotracer development and in vivo imaging: recent advancements and new perspectives. Movement Disorders 2022, 37(5), 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Xiang, J.; Ye, K.; Zhang, Z. Development of Positron Emission Tomography Radiotracers for Imaging α-Synuclein Aggregates. Cells 2025, 14(12), 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldecoa, I.; Navarro-Otano, J.; Stefanova, N.; Sprenger, F. S.; Seppi, K.; Poewe, W.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Valldeoriola, F.; Gelpi, E.; Tolosa, E. Alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity patterns in the enteric nervous system. Neuroscience Letters 2015, 602, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A. The intestinal luminal sources of α-synuclein: a gastroenterologist perspective. Nutrition Reviews 2021, 80(2), 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuegbunam, B. C.; Li, J.; Paslawski, W.; Weber, W.; Svenningsson, P.; Ågren, H.; Yousefi, B. H. Toward novel [18F]Fluorine-Labeled radiotracers for the imaging of A-Synuclein fibrils. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14, 830704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, R.; Matsuoka, K.; Kimura, Y.; Kataoka, Y.; Oya, M.; Hirata, K.; Tagai, K.; Takahata, K.; Seki, C.; Kawamura, K.; Zhang, M.-R.; Higuchi, M.; Endo, H. Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of two novel α-synuclein PET tracers, 18F-SPAL-T-06 and 18F-C05-05. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, C. B.; Shannon, K. M.; Kordower, J. H.; Voigt, R. M.; Shaikh, M.; Jaglin, J. A.; Estes, J. D.; Dodiya, H. B.; Keshavarzian, A. Increased Intestinal Permeability Correlates with Sigmoid Mucosa alpha-Synuclein Staining and Endotoxin Exposure Markers in Early Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2011, 6(12), e28032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulak, A. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2015, 21(37), 10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietdijk, C. D.; Perez-Pardo, P.; Garssen, J.; Van Wezel, R. J. A.; Kraneveld, A. D. Exploring Braak’s hypothesis of Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Neurology 2017, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. P.; Carvey, P. M.; Keshavarzian, A.; Shannon, K. M.; Shaikh, M.; Bakay, R. a. E.; Kordower, J. H. Progression of intestinal permeability changes and alpha-synuclein expression in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2013, 29(8), 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanow, C. W.; Wakeman, D. R.; Kordower, J. H. Peripheral alpha-synuclein and Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2014, 29(8), 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Pardo, P.; Kliest, T.; Dodiya, H. B.; Broersen, L. M.; Garssen, J.; Keshavarzian, A.; Kraneveld, A. D. The gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease: Possibilities for food-based therapies. European Journal of Pharmacology 2017, 817, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Pardo, P.; Dodiya, H. B.; Engen, P. A.; Forsyth, C. B.; Huschens, A. M.; Shaikh, M.; Voigt, R. M.; Naqib, A.; Green, S. J.; Kordower, J. H.; Shannon, K. M.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A. D.; Keshavarzian, A. Role of TLR4 in the gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease: a translational study from men to mice. Gut 2018, 68(5), 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, D.; Ali, S. A.; Singh, R. K. Emerging role of gut microbiota in modulation of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration with emphasis on Alzheimer’s disease. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2020, 106, 110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, N.; Yamashiro, K.; Kuroki, T.; Tanaka, R.; Urabe, T.; Ueno, Y.; Miyamoto, N.; Takanashi, M.; Shimura, H.; Inaba, T.; Yamashiro, Y.; Nomoto, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Takahashi, T.; Tsuji, H.; Asahara, T.; Hattori, N. Metabolic endotoxemia promotes neuroinflammation after focal cerebral ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2020, 40(12), 2505–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Yang, L.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, L.; Fei, Z.; Li, X.; Hou, J.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Gut microbiota are associated with psychological Stress-Induced defections in intestinal and Blood–Brain barriers. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M. S. Microglia in Parkinson’s disease. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 2019, 1175, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. C. The Endotoxin Hypothesis of Neurodegeneration 2019, Vol. 16, 180. [CrossRef]

- Bodea, L. -g.; Wang, Y.; Linnartz-Gerlach, B.; Kopatz, J.; Sinkkonen, L.; Musgrove, R.; Kaoma, T.; Muller, A.; Vallar, L.; Di Monte, D. A.; Balling, R.; Neumann, H. Neurodegeneration by activation of the Microglial Complement-Phagosome pathway. Journal of Neuroscience 2014, 34(25), 8546–8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.; Brundin, P. Immunotherapy in Parkinson’s Disease: Micromanaging Alpha-Synuclein aggregation. Journal of Parkinson S Disease 2015, 5(3), 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roodveldt, C.; Labrador-Garrido, A.; Gonzalez-Rey, E.; Fernandez-Montesinos, R.; Caro, M.; Lachaud, C. C.; Waudby, C. A.; Delgado, M.; Dobson, C. M.; Pozo, D. Glial Innate Immunity Generated by Non-Aggregated Alpha-Synuclein in Mouse: Differences between Wild-type and Parkinson’s Disease-Linked Mutants. PLoS ONE 2010, 5(10), e13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, L.; Irschick, R.; Schanda, K.; Reindl, M.; Klimaschewski, L.; Poewe, W.; Wenning, G. K.; Stefanova, N. Toll-like receptor 4 is required for α-synuclein dependent activation of microglia and astroglia. Glia 2012, 61(3), 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, A. S.; Delic, V.; Thome, A. D.; Bryant, N.; Liu, Z.; Chandra, S.; Jurkuvenaite, A.; West, A. B. α-Synuclein fibrils recruit peripheral immune cells in the rat brain prior to neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2017, 5(1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croisier, E.; Moran, L. B.; Dexter, D. T.; Pearce, R. K.; Graeber, M. B. Microglial inflammation in the parkinsonian substantia nigra: relationship to alpha-synuclein deposition. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2005, 2(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. P.; Marmion, D. J.; Schonhoff, A. M.; Jurkuvenaite, A.; Won, W.-J.; Standaert, D. G.; Kordower, J. H.; Harms, A. S. T cell infiltration in both human multiple system atrophy and a novel mouse model of the disease. Acta Neuropathologica 2020, 139(5), 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, P. S. Inflammation as a causative factor in the aetiology of Parkinson’s disease. British Journal of Pharmacology 2007, 150(8), 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joers, V.; Tansey, M. G.; Mulas, G.; Carta, A. R. Microglial phenotypes in Parkinson’s disease and animal models of the disease. Progress in Neurobiology 2016, 155, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, M. Imaging of microglia in patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2012, 3, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J. G.; Kim, N.; Ju, I. G.; Eo, H.; Lim, S.-M.; Jang, S.-E.; Kim, D.-H.; Oh, M. S. Oral administration of Proteus mirabilis damages dopaminergic neurons and motor functions in mice. Scientific Reports 2018, 8(1), 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Bing, G. Aging enhances the neuroinflammatory response and α-synuclein nitration in rats. Neurobiology of Aging 2010, 31(9), 1649–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Mohite, G. M.; Krishnamoorthy, J.; Gayen, N.; Mehra, S.; Navalkar, A.; Kotler, S. A.; Ratha, B. N.; Ghosh, A.; Kumar, R.; Garai, K.; Mandal, A. K.; Maji, S. K.; Bhunia, A. Lipopolysaccharide from Gut Microbiota Modulates α-Synuclein Aggregation and Alters Its Biological Function. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2019, 10(5), 2229–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Nguyen, L. T. T.; Burlak, C.; Chegini, F.; Guo, F.; Chataway, T.; Ju, S.; Fisher, O. S.; Miller, D. W.; Datta, D.; Wu, F.; Wu, C.-X.; Landeru, A.; Wells, J. A.; Cookson, M. R.; Boxer, M. B.; Thomas, C. J.; Gai, W. P.; Ringe, D.; Petsko, G. A.; Hoang, Q. Q. Caspase-1 causes truncation and aggregation of the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein α-synuclein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113(34), 9587–9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. G.; Stribinskis, V.; Rane, M. J.; Demuth, D. R.; Gozal, E.; Roberts, A. M.; Jagadapillai, R.; Liu, R.; Choe, K.; Shivakumar, B.; Son, F.; Jin, S.; Kerber, R.; Adame, A.; Masliah, E.; Friedland, R. P. Exposure to the Functional Bacterial Amyloid Protein Curli Enhances Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation in Aged Fischer 344 Rats and Caenorhabditis elegans. Scientific Reports 2016, 6(1), 34477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavali, S.; Combs, C. K.; Ebadi, M. Reactive macrophages increase oxidative stress and Alpha-Synuclein nitration during death of dopaminergic neuronal cells in Co-Culture: Relevance to Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochemical Research 2006, 31(1), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizabal-Carvallo, J. F.; Alonso-Juarez, M. The Link between Gut Dysbiosis and Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroscience 2020, 432, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L. J.; Sagara, Y.; Arroyo, A.; Rockenstein, E.; Sisk, A.; Mallory, M.; Wong, J.; Takenouchi, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Masliah, E. A-Synuclein promotes mitochondrial deficit and oxidative stress. American Journal of Pathology 2000, 157(2), 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Sun, X.; Liao, X.; Zhang, X.; Zarabi, S.; Schimmer, A.; Hong, Y.; Ford, C.; Luo, Y.; Qi, X. Alpha-synuclein suppresses mitochondrial protease ClpP to trigger mitochondrial oxidative damage and neurotoxicity. Acta Neuropathologica 2019, 137(6), 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, W.; Jiménez, J.; McIIvin, M.; Saito, M. A.; Kwakye, G. F. A-Synuclein enhances cadmium uptake and neurotoxicity via oxidative stress and caspase activated cell death mechanisms in a dopaminergic cell model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicity Research 2017, 32(2), 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryanovski, D. I.; Guzman, J. N.; Xie, Z.; Galteri, D. J.; Volpicelli-Daley, L. A.; Lee, V. M.-Y.; Miller, R. J.; Schumacker, P. T.; Surmeier, D. J. Calcium entry and -Synuclein inclusions elevate dendritic mitochondrial oxidant stress in dopaminergic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33(24), 10154–10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapias, V.; Hu, X.; Luk, K. C.; Sanders, L. H.; Lee, V. M.; Greenamyre, J. T. Synthetic alpha-synuclein fibrils cause mitochondrial impairment and selective dopamine neurodegeneration in part via iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017, 74(15), 2851–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpartida, A. B.; Williamson, M.; Narendra, D. P.; Wade-Martins, R.; Ryan, B. J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson’s Disease: From mechanism to therapy. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2020, 46(4), 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Xiong, Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Gao, J.; Xu, H. Asiatic acid prevents oxidative stress and apoptosis by inhibiting the translocation of A-Synuclein into mitochondria. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, A.; Schwarzschild, M. A. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention. The Lancet Neurology 2016, 15(12), 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinderi, K.; Bostantjopoulou, S.; Fidani, L. The genetic background of Parkinson’s disease: current progress and future prospects. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2016, 134(5), 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.-M.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, H.; Kam, W.; Wilson, B.; Hong, J.-S. Neuroinflammation and A-Synuclein dysfunction potentiate each other, driving chronic progression of neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Environmental Health Perspectives 2011, 119(6), 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H. J. The impact of nutrition on the human microbiome. Nutrition Reviews 2012, 70, S10–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K. S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D. R.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Cao, J.; Wang, B.; Liang, H.; Zheng, H.; Xie, Y.; Tap, J.; Lepage, P.; Bertalan, M.; Batto, J.-M.; Hansen, T.; Paslier, D. L.; Linneberg, A.; Nielsen, H. B.; Pelletier, E.; Renault, P.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Turner, K.; Zhu, H.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Jian, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Qin, N.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Brunak, S.; Doré, J.; Guarner, F.; Kristiansen, K.; Pedersen, O.; Parkhill, J.; Weissenbach, J.; Bork, P.; Ehrlich, S. D.; Wang, J. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464(7285), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, L. J.; Gibson, D. L.; Klegeris, A. Unhealthy gut, unhealthy brain: The role of the intestinal microbiota in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochemistry International 2018, 120, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fülling, C.; Dinan, T. G.; Cryan, J. F. Gut Microbe to Brain Signaling: What Happens in Vagus…. Neuron 2019, 101(6), 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möhle, L.; Mattei, D.; Heimesaat, M. M.; Bereswill, S.; Fischer, A.; Alutis, M.; French, T.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Matzinger, P.; Dunay, I. R.; Wolf, S. A. Ly6Chi Monocytes Provide a Link between Antibiotic-Induced Changes in Gut Microbiota and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Cell Reports 2016, 15(9), 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braniste, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Tóth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L. G.; Kundu, P.; Gulyás, B.; Halldin, C.; Hultenby, K.; Nilsson, H.; Hebert, H.; Volpe, B. T.; Diamond, B.; Pettersson, S. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Science Translational Medicine 2014, 6(263), 263ra158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Shen, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, D.; Su, Z.; Chen, X. Constipation induced gut microbiota dysbiosis exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 mice. Journal of Translational Medicine 2021, 19(1), 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Fornai, M.; D’Antongiovanni, V.; Antonioli, L.; Bernardini, N.; Derkinderen, P. The intestinal barrier in disorders of the central nervous system. the Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 8(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome, M. O. Gut microbiota Disorder, gut epithelial and Blood–Brain barrier dysfunctions in etiopathogenesis of dementia: molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways. NeuroMolecular Medicine 2019, 21(3), 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E. C.; Neumann, M.; Desai, M. S. Interactions of commensal and pathogenic microorganisms with the intestinal mucosal barrier. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16(8), 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, Y.; Ma, W.; Yu, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, T.; Xiao, R. 27-Hydroxycholesterol contributes to cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice through microbiota dysbiosis and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2020, 17(1), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzian, A.; Green, S. J.; Engen, P. A.; Voigt, R. M.; Naqib, A.; Forsyth, C. B.; Mutlu, E.; Shannon, K. M. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2015, 30(10), 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P. a. B.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; Kinnunen, E.; Murros, K.; Auvinen, P. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Movement Disorders 2014, 30(3), 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, M. M.; Spiegel, J.; Dillmann, K.-U.; Grundmann, D.; Philippeit, H.; Bürmann, J.; Faßbender, K.; Schwiertz, A.; Schäfer, K.-H. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age-matched controls. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2016, 32, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Burns, E. M.; Debelius, J. W.; Morton, J. T.; Wissemann, W. T.; Lewis, M. R.; Wallen, Z. D.; Peddada, S. D.; Factor, S. A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C. P.; Knight, R.; Payami, H. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Movement Disorders 2017, 32(5), 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wu, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, T.; Liang, S.; Duan, Y.; Jin, F.; Qin, B. Structural changes of gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and its correlation with clinical features. Science China Life Sciences 2017, 60(11), 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, V. A.; Saltykova, I. V.; Zhukova, I. A.; Alifirova, V. M.; Zhukova, N. G.; Dorofeeva, Yu. B.; Tyakht, A. V.; Kovarsky, B. A.; Alekseev, D. G.; Kostryukova, E. S.; Mironova, Yu. S.; Izhboldina, O. P.; Nikitina, M. A.; Perevozchikova, T. V.; Fait, E. A.; Babenko, V. V.; Vakhitova, M. T.; Govorun, V. M.; Sazonov, A. E. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine 2017, 162(6), 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarf, J. R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L. P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Medicine 2017, 9(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Zheng, W.; He, Y.; Tang, W.; Wei, X.; He, R.; Huang, W.; Su, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xie, H. Gut microbiota in patients with Parkinson’s disease in southern China. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2018, 53, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Sui, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in North-Eastern Han Chinese population with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience Letters 2019, 707, 134297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucci, D.; Cerroni, R.; Unida, V.; Farcomeni, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N. B.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in a selected population of Parkinson’s patients. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2019, 65, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirstea, M. S.; Yu, A. C.; Golz, E.; Sundvick, K.; Kliger, D.; Radisavljevic, N.; Foulger, L. H.; Mackenzie, M.; Huan, T.; Finlay, B. B.; Appel-Cresswell, S. Microbiota composition and metabolism are associated with gut function in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2020, 35(7), 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma-Grigorov, A.; Meixner, H.; Mrochen, A.; Wirtz, S.; Winkler, J.; Marxreiter, F. Changes in gastrointestinal microbiome composition in PD: a pivotal role of covariates. Frontiers in Neurology 2020, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vascellari, S.; Palmas, V.; Melis, M.; Pisanu, S.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Perra, D.; Madau, V.; Sarchioto, M.; Oppo, V.; Simola, N.; Morelli, M.; Santoru, M. L.; Atzori, L.; Melis, M.; Cossu, G.; Manzin, A. Gut Microbiota and Metabolome Alterations Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. mSystems 2020, 5(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aho, V. T. E.; Houser, M. C.; Pereira, P. a. B.; Chang, J.; Rudi, K.; Paulin, L.; Hertzberg, V.; Auvinen, P.; Tansey, M. G.; Scheperjans, F. Relationships of gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, inflammation, and the gut barrier in Parkinson’s disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2021, 16(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Yue, L.; Fang, X.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Sun, X.; Jia, X.; Yang, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, C.; Ma, G.; Sang, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, P. Altered gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease patients/healthy spouses and its association with clinical features. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2020, 81, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, P.; Li, B.; Du, J.; He, Y.; Su, B.; Xu, L.-M.; Wang, L.; Huang, R.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Q. Gut metagenomics-derived genes as potential biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020, 143(8), 2474–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Paul, K. C.; Jacobs, J. P.; Chou, H.-C.; Folle, A. D.; Del Rosario, I.; Yu, Y.; Bronstein, J. M.; Keener, A. M.; Ritz, B. Parkinson’s Disease and the gut microbiome in rural California. Journal of Parkinson S Disease 2022, 12(8), 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Gasbarrini, A. Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: between good and evil. Gut 2016, 65(11), 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Redondo-Blanco, S.; Gutiérrez-Del-Río, I.; Miguélez, E. M.; Villar, C. J.; Lombó, F. Colon microbiota fermentation of dietary prebiotics towards short-chain fatty acids and their roles as anti-inflammatory and antitumour agents: A review. Journal of Functional Foods 2016, 25, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H. J.; Duncan, S. H.; Scott, K. P.; Louis, P. Links between diet, gut microbiota composition and gut metabolism. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2014, 74(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Long, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, L.; Hamaker, B. R. Fiber-utilizing capacity varies in Prevotella- versus Bacteroides-dominated gut microbiota. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, Z.-R.; Green, R. S.; Holzmanr, I. R.; Lin, J. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-Activated protein kinase in CACO-2 cell monolayers. Journal of Nutrition 2009, 139(9), 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plöger, S.; Stumpff, F.; Penner, G. B.; Schulzke, J.; Gäbel, G.; Martens, H.; Shen, Z.; Günzel, D.; Aschenbach, J. R. Microbial butyrate and its role for barrier function in the gastrointestinal tract. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2012, 1258(1), 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, S. C.; Barbara, G.; Buurman, W.; Ockhuizen, T.; Schulzke, J.-D.; Serino, M.; Tilg, H.; Watson, A.; Wells, J. M. Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterology 2014, 14(1), 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Asmakh, M.; Hedin, L. Microbiota and the control of blood-tissue barriers. Tissue Barriers 2015, 3(3), e1039691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspani, G.; Swann, J. Small talk: microbial metabolites involved in the signaling from microbiota to brain. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2019, 48, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-Chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165(6), 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, C. E.; Kim, D. H. J.; Pusceddu, M. M.; Knotts, T. A.; Rabasa, G.; Sladek, J. A.; Hsieh, M. T.; Honeycutt, M.; Brust-Mascher, I.; Barboza, M.; Gareau, M. G. Myelin as a regulator of development of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Brain Behavior and Immunity 2020, 91, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; De Angelis, A. L. H.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; Schwierzeck, V.; Utermöhlen, O.; Chun, E.; Garrett, W. S.; McCoy, K. D.; Diefenbach, A.; Staeheli, P.; Stecher, B.; Amit, I.; Prinz, M. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nature Neuroscience 2015, 18(7), 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, C. N.; Olofsson, L. E. The role of the gut microbiota in development, function and disorders of the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 2019, 31(5), e12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikachain, N.; Sungkaworn, T.; Muanprasat, C.; Asavapanumas, N. Neuroprotective effect of short-chain fatty acids against oxidative stress-induced SH-SY5Y injury via GPR43-dependent pathway. Journal of Neurochemistry 2023, 166(2), 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, P. S.; Dallas, S.; Wilson, B.; Block, M. L.; Wang, C.-C.; Kinyamu, H.; Lu, N.; Gao, X.; Leng, Y.; Chuang, D.-M.; Zhang, W.; Lu, R. B.; Hong, J.-S. Histone deacetylase inhibitors up-regulate astrocyte GDNF and BDNF gene transcription and protect dopaminergic neurons. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 11(08), 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S. K.; Schneider, J. S. Protection of dopaminergic cells from MPP+-mediated toxicity by histone deacetylase inhibition. Brain Research 2010, 1354, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canani, R. B. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2011, 17(12), 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrien, M.; Vaughan, E. E.; Plugge, C. M.; De Vos, W. M. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEMATIC AND EVOLUTIONARY MICROBIOLOGY 2004, 54(5), 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, D. P. A.; Bosque, B. P.; De Godoy, J. V. P.; Rodrigues, P. V.; Meneses, D. D.; Tostes, K.; Tonoli, C. C. C.; De Carvalho, H. F.; González-Billault, C.; De Castro Fonseca, M. Akkermansia muciniphila induces mitochondrial calcium overload and α -synuclein aggregation in an enteroendocrine cell line. iScience 2022, 25(3), 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Picón, M.; Laguna, A. New avenues for Parkinson’s Disease therapeutics: Disease-Modifying Strategies based on the gut Microbiota. Biomolecules 2021, 11(3), 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ning, J.; Bao, X.-Q.; Shang, M.; Ma, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, D. Fecal microbiota transplantation protects rotenone-induced Parkinson’s disease mice via suppressing inflammation mediated by the lipopolysaccharide-TLR4 signaling pathway through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Microbiome 2021, 9(1), 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, M.; Adampour, Z.; Dowlat, B. F.; Yaghmayee, S.; Tabaei, F. M.; Oksenych, V.; Naderian, R. A novel frontier in Gut–Brain axis Research: The transplantation of fecal microbiota in neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomedicines 2025, 13(4), 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsavath, T.; Laeeq, T.; Tun, K. M.; Hong, A. S. The Potential Role of fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson’s Disease: A systematic literature review. Applied Microbiology 2023, 3(3), 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-F.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Zhou, Z.-L.; Jia, X.-B.; Xu, Y.-D.; Yang, Q.; Cui, C.; Shen, Y.-Q. Neuroprotective effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice: Gut microbiota, glial reaction and TLR4/TNF-α signaling pathway. Brain Behavior and Immunity 2018, 70, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T. R.; Debelius, J. W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G. G.; Ilhan, Z. E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C. E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; Chesselet, M.-F.; Keshavarzian, A.; Shannon, K. M.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; Wittung-Stafshede, P.; Knight, R.; Mazmanian, S. K. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 2016, 167(6), 1469–1480.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Tan, G.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.; Ruan, G.; Ying, S.; Qie, J.; Hu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, F.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Y.; Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Wei, Y. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with Parkinson’s disease: clinical trial results from a randomized, placebo-controlled design. Gut Microbes 2023, 15(2), 2284247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuPont, H. L.; Suescun, J.; Jiang, Z.-D.; Brown, E. L.; Essigmann, H. T.; Alexander, A. S.; DuPont, A. W.; Iqbal, T.; Utay, N. S.; Newmark, M.; Schiess, M. C. Fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson’s disease—A randomized repeat-dose, placebo-controlled clinical pilot study. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruggeman, A.; Vandendriessche, C.; Hamerlinck, H.; De Looze, D.; Tate, D. J.; Vuylsteke, M.; De Commer, L.; Devolder, L.; Raes, J.; Verhasselt, B.; Laukens, D.; Vandenbroucke, R. E.; Santens, P. Safety and efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation in patients with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease (GUT-PARFECT): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 71, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Levo, R.; Bosch, B.; Lääperi, M.; Pereira, P. a. B.; Smolander, O.-P.; Aho, V. T. E.; Vetkas, N.; Toivio, L.; Kainulainen, V.; Fedorova, T. D.; Lahtinen, P.; Ortiz, R.; Kaasinen, V.; Satokari, R.; Arkkila, P. Fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurology 2024, 81(9), 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, L.; Zhang, M.; Shen, P.; Zhao, W.; Tong, Q.; Wu, S.; Dai, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplantation for Mild-to-Moderate Parkinson’s Disease: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Behavior and Immunity 2025, 130, 106086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, X.-Y.; Yao, X.-H.; Xu, L.-J.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Zhang, L.-P.; Liu, Y.; Pei, S.-F.; Zhou, C.-L. Evaluation of fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson’s disease patients with constipation. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.-J.; Yang, X.-Z.; Tong, Q.; Shen, P.; Ma, S.-J.; Wu, S.-N.; Zheng, J.-L.; Wang, H.-G. Fecal microbiota transplantation therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Medicine 2020, 99(35), e22035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xu, H.; Luo, Q.; He, J.; Li, M.; Chen, H.; Tang, W.; Nie, Y.; Zhou, Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation to treat Parkinson’s disease with constipation. Medicine 2019, 98(26), e16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcella, C.; Cui, B.; Kelly, C. R.; Ianiro, G.; Cammarota, G.; Zhang, F. Systematic review: the global incidence of faecal microbiota transplantation-related adverse events from 2000 to 2020. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020, 53(1), 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. S.; Zhu, A.; Benes, V.; Costea, P. I.; Hercog, R.; Hildebrand, F.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Salojärvi, J.; Voigt, A. Y.; Zeller, G.; Sunagawa, S.; De Vos, W. M.; Bork, P. Durable coexistence of donor and recipient strains after fecal microbiota transplantation. Science 2016, 352(6285), 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, C.; Xu, J.; Ye, C.; Chen, X.; Tian, H.; Zong, N.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Lv, X.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Cui, J.; Lin, Z.; Lu, J.; Yang, R.; Yin, F.; Qin, N.; Li, N.; Xu, Q.; Qin, H. Donor-recipient intermicrobial interactions impact transfer of subspecies and fecal microbiota transplantation outcome. Cell Host & Microbe 2024, 32(3), 349–365.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barboza, J. L.; Okun, M. S.; Moshiree, B. The treatment of gastroparesis, constipation and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2015, 16(16), 2449–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S. S. C.; Bhagatwala, J. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: clinical features and therapeutic management. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 2019, 10(10), e00078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, N.; Rydzewska-Rosołowska, A.; Kakareko, K.; Rosołowski, M.; Głowińska, I.; Hryszko, T. Show Me What You Have Inside—The Complex Interplay between SIBO and Multiple Medical Conditions—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 15(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F. R.; Zocco, M. A.; D’Aversa, F.; Pompili, M.; Gasbarrini, A. Eubiotic properties of rifaximin: Disruption of the traditional concepts in gut microbiota modulation. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2017, 23(25), 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Cheng, S.; Pan, F.; Liu, D.; Ho, R. C. M.; Ho, C. S. H. Rifaximin-mediated gut microbiota regulation modulates the function of microglia and protects against CUMS-induced depression-like behaviors in adolescent rat. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2021, 18(1), 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.-T.; Chan, L.; Chen, K.-Y.; Lee, H.-H.; Huang, L.-K.; Yang, Y.-C. S. H.; Liu, Y.-R.; Hu, C.-J. Rifaximin modifies gut microbiota and attenuates inflammation in Parkinson’s Disease: Preclinical and clinical studies. Cells 2022, 11(21), 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhocki, P. V.; Ronald, J. S.; Diehl, A. M. E.; Murdoch, D. M.; Doraiswamy, P. M. Probing gut-brain links in Alzheimer’s disease with rifaximin. Alzheimer S & Dementia Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2022, 8(1), e12225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Bove, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Petracca, M.; Zocco, M. A.; Ragazzoni, E.; Barbaro, F.; Piano, C.; Fortuna, S.; Tortora, A.; Di Giacopo, R.; Campanale, M.; Gigante, G.; Lauritano, E. C.; Navarra, P.; Marconi, S.; Gasbarrini, A.; Bentivoglio, A. R. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2013, 28(9), 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G. R.; Merenstein, D. J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R. B.; Flint, H. J.; Salminen, S.; Calder, P. C.; Sanders, M. E. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2014, 11(8), 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fijan, S. Microorganisms with Claimed Probiotic Properties: An Overview of Recent Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2014, 11(5), 4745–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, J. Fiber and Prebiotics: Mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients 2013, 5(4), 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J. M.; Lee, S. C.; Ham, C.; Kim, Y. W. Effect of probiotic supplementation on gastrointestinal motility, inflammation, motor, non-motor symptoms and mental health in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gut Pathogens 2023, 15(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The effect of probiotics on the production of Short-Chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12(4), 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinan, T. G.; Stanton, C.; Cryan, J. F. Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biological Psychiatry 2013, 74(10), 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long-Smith, C.; O’Riordan, K. J.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T. G.; Cryan, J. F. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: new therapeutic opportunities. The Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2019, 60(1), 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M. E.; Mostafa, T. M.; Ghali, A. A.; El-Afify, D. R. Randomized controlled trial evaluating synbiotic supplementation as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33(7), 3897–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-S.; Chang, H.-C.; Weng, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Kuo, Y.-S.; Tsai, Y.-C. The Add-On Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021, 8, 650053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-F.; Cheng, Y.-F.; You, S.-T.; Kuo, W.-C.; Huang, C.-W.; Chiou, J.-J.; Hsu, C.-C.; Hsieh-Li, H.-M.; Wang, S.; Tsai, Y.-C. Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 alleviates neurodegenerative progression in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behavior and Immunity 2020, 90, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Z.; Cheng, S.-H.; Chang, M.-Y.; Lin, Y.-F.; Wu, C.-C.; Tsai, Y.-C. Neuroprotective Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease: The Role of Gut Microbiota and MicroRNAs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(7), 6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmi, A.; Sandre, M.; Russo, F. P.; Tombesi, G.; Garrì, F.; Campagnolo, M.; Carecchio, M.; Biundo, R.; Spolverato, G.; Macchi, V.; Savarino, E.; Farinati, F.; Parchi, P.; Porzionato, A.; Bubacco, L.; De Caro, R.; Kovacs, G. G.; Antonini, A. Duodenal alpha-Synuclein pathology and enteric gliosis in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2023, 38(5), 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S. J.; Kim, J.; Lee, H. J.; Ryu, H.; Kim, K.; Lee, J. H.; Jung, K. W.; Kim, M. J.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y. J.; Yun, S.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Myung, S. Alpha-synuclein in gastric and colonic mucosa in Parkinson’s disease: Limited role as a biomarker. Movement Disorders 2016, 31(2), 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Park, S.-H.; Yun, J. Y.; Shin, J. H.; Yang, H.-K.; Lee, H.-J.; Kong, S.-H.; Suh, Y.-S.; Shen, G.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Jeon, B. Fundamental limit of alpha-synuclein pathology in gastrointestinal biopsy as a pathologic biomarker of Parkinson’s disease: Comparison with surgical specimens. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2017, 44, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffmann, C.; Bengoa-Vergniory, N.; Poggiolini, I.; Ritchie, D.; Hu, M. T.; Alegre-Abarrategui, J.; Parkkinen, L. Detection of alpha-synuclein conformational variants from gastro-intestinal biopsy tissue as a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology 2018, 44(7), 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visanji, N. P.; Marras, C.; Kern, D. S.; Dakheel, A. A.; Gao, A.; Liu, L. W. C.; Lang, A. E.; Hazrati, L.-N. Colonic mucosal α-synuclein lacks specificity as a biomarker for Parkinson disease. Neurology 2015, 84(6), 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubomski, M.; Tan, A. H.; Lim, S.-Y.; Holmes, A. J.; Davis, R. L.; Sue, C. M. Parkinson’s disease and the gastrointestinal microbiome. Journal of Neurology 2020, 267(9), 2507–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrove, R. E.; Helwig, M.; Bae, E.-J.; Aboutalebi, H.; Lee, S.-J.; Ulusoy, A.; Di Monte, D. A. Oxidative stress in vagal neurons promotes parkinsonian pathology and intercellular α-synuclein transfer. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2019, 129(9), 3738–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Van Esch, B. C. A. M.; Wagenaar, G. T. M.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G.; Henricks, P. A. J. Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. European Journal of Pharmacology 2018, 831, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnolo, M.; Weis, L.; Sandre, M.; Tushevski, A.; Russo, F. P.; Savarino, E.; Carecchio, M.; Stocco, E.; Macchi, V.; Caro, R.; Parchi, P.; Bubacco, L.; Porzionato, A.; Antonini, A.; Emmi, A. Immune Landscape of the Enteric Nervous System Differentiates Parkinson’s Disease Patients from Controls: The PADUA-CESNE Cohort. Neurobiology of Disease 2024, 196, 106609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizabal-Carvallo, J.; Alonso-Juarez, M. The Link between Gut Dysbiosis and Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroscience 2020, 432, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, E.; Murphy, S.; Martinson, H. Alpha-Synuclein Pathology and the Role of the Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D. K.; Kiyota, T.; Mosley, R.; Gendelman, H. A Model of Nitric Oxide Induced α-Synuclein Misfolding in Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroscience Letters 2012, 523, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-J.; Liang, C.-Y.; Yang, L.-Q.; Ren, S.; Xia, Y.; Cui, L.; Li, X.-F.; Gao, B. Association of Parkinson’s Disease With Microbes and Microbiological Therapy. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 619354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz de Ora, L.; Uyeda, K. S.; Bess, E. Discovery of a Gut Bacterial Metabolic Pathway that Drives α-Synuclein Aggregation. ACS Chemical Biology 2024, 19, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioghen, O.; Gaina, G.; Lambrescu, I.; Manole, E.; Pop, S.; Niculescu, T. M.; Mosoia, O.; Ceafalan, L.; Popescu, B. Bacterial Products Initiation of Alpha-Synuclein Pathology: An In Vitro Study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 81020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.; Robinson, L. S.; Pinkner, J.; Roth, R.; Heuser, J.; Hammar, M.; Normark, S.; Hultgren, S. Role of Escherichia coli Curli Operons in Directing Amyloid Fiber Formation. Science 2002, 295, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, B.; Guo, J. Parkinson’s Disease and Gut Microbiota: From Clinical to Mechanistic and Therapeutic Studies. Translational Neurodegeneration 2023, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, S.; Sahay, S.; Maji, S. α-Synuclein Misfolding and Aggregation: Implications in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 2019, 1867, 890–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, K.; Westermark, G.; Olsén, A.; Westermark, P. Protein Fibrils in Nature Can Enhance Amyloid Protein A Amyloidosis in Mice: Cross-Seeding as a Disease Mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 6098–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoite, S. S.; Han, Y.; Ruotolo, B.; Chapman, M. Mechanistic Insights into Accelerated α-Synuclein Aggregation Mediated by Human Microbiome-Associated Functional Amyloids. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298, 102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawska, M.; Jodynis-Liebert, J. What Is the Evidence that Parkinson’s Disease Is a Prion Disorder, Which Originates in the Gut? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Lin, C.-H. Gut Microenvironmental Changes as a Potential Trigger in Parkinson’s Disease through the Gut–Brain Axis. Journal of Biomedical Science 2022, 29, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.; Kluge, A.; Böttner, M.; Zunke, F.; Cossais, F.; Berg, D.; Arnold, P. Alpha Synuclein Connects the Gut–Brain Axis in Parkinson’s Disease Patients – A View on Clinical Aspects, Cellular Pathology and Analytical Methodology. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8, 573696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Trautwein, C.; Romani, J.; Salker, M.; Neckel, P.; Fraccaroli, I.; Abeditashi, M.; Woerner, N.; Admard, J.; Dhariwal, A.; Dueholm, M.; Schäfer, K.; Lang, F.; Otzen, D.; Lashuel, H.; Riess, O.; Casadei, N. Overexpression of Human Alpha-Synuclein Leads to Dysregulated Microbiome/Metabolites with Ageing in a Rat Model of Parkinson Disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2023, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, M.; Nishiwaki, H.; Hamaguchi, T.; Ohno, K. Gastrointestinal Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease and Other Lewy Body Diseases. NPJ Parkinson’s Disease 2023, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.; Zocco, M.; D’Aversa, F.; Pompili, M.; Gasbarrini, A. Eubiotic Properties of Rifaximin: Disruption of the Traditional Concepts in Gut Microbiota Modulation. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2017, 23, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.; Hiniker, A.; Kuo, Y.; Nussbaum, R.; Liddle, R. α-Synuclein in Gut Endocrine Cells and Its Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. JCI Insight 2017, 2(12), e92295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillusson, S.; Clairembault, T.; Biraud, M.; Neunlist, M.; Derkinderen, P. Activity-Dependent Secretion of Alpha-Synuclein by Enteric Neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry 2013, 125(4), 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).