Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

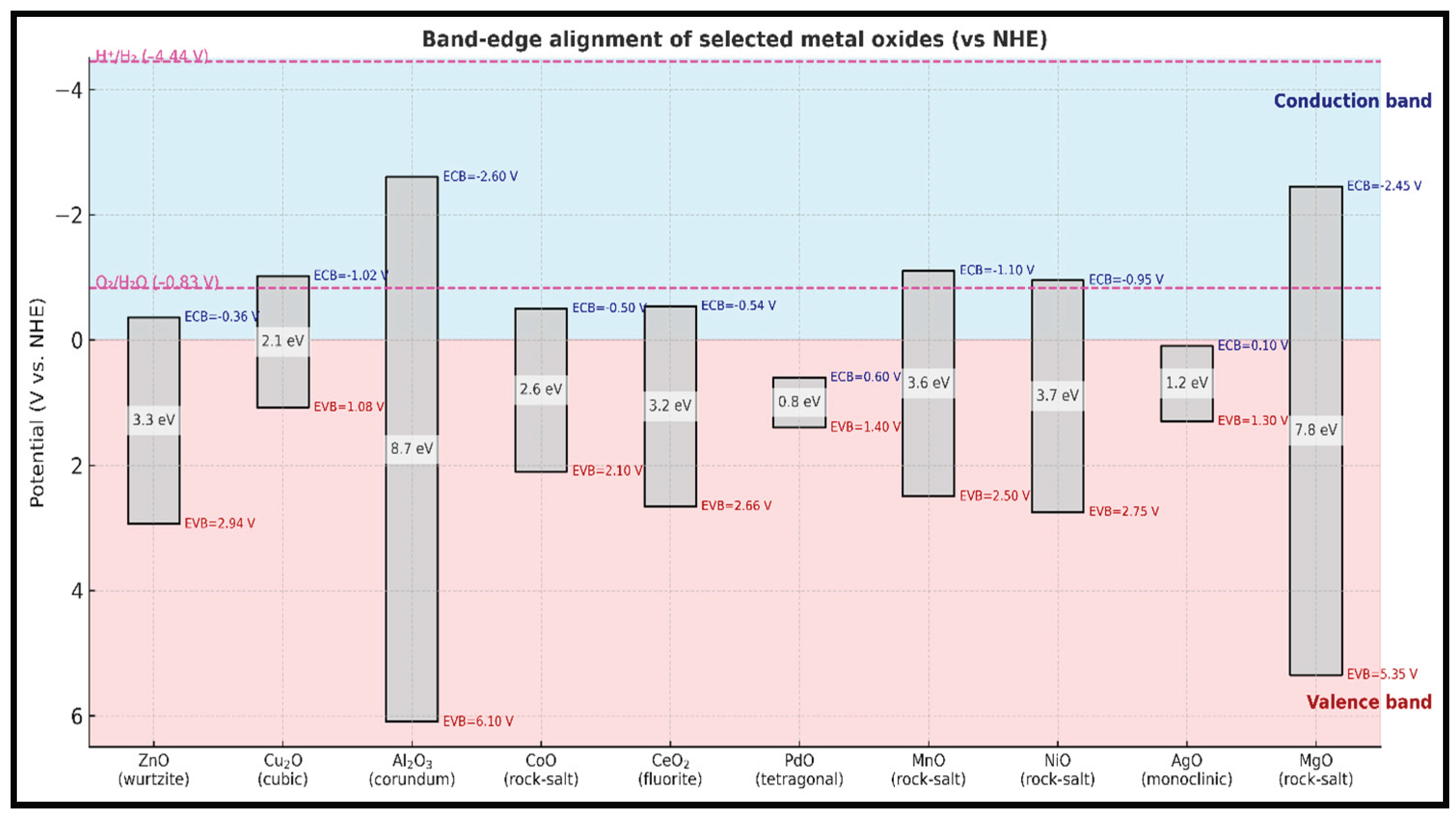

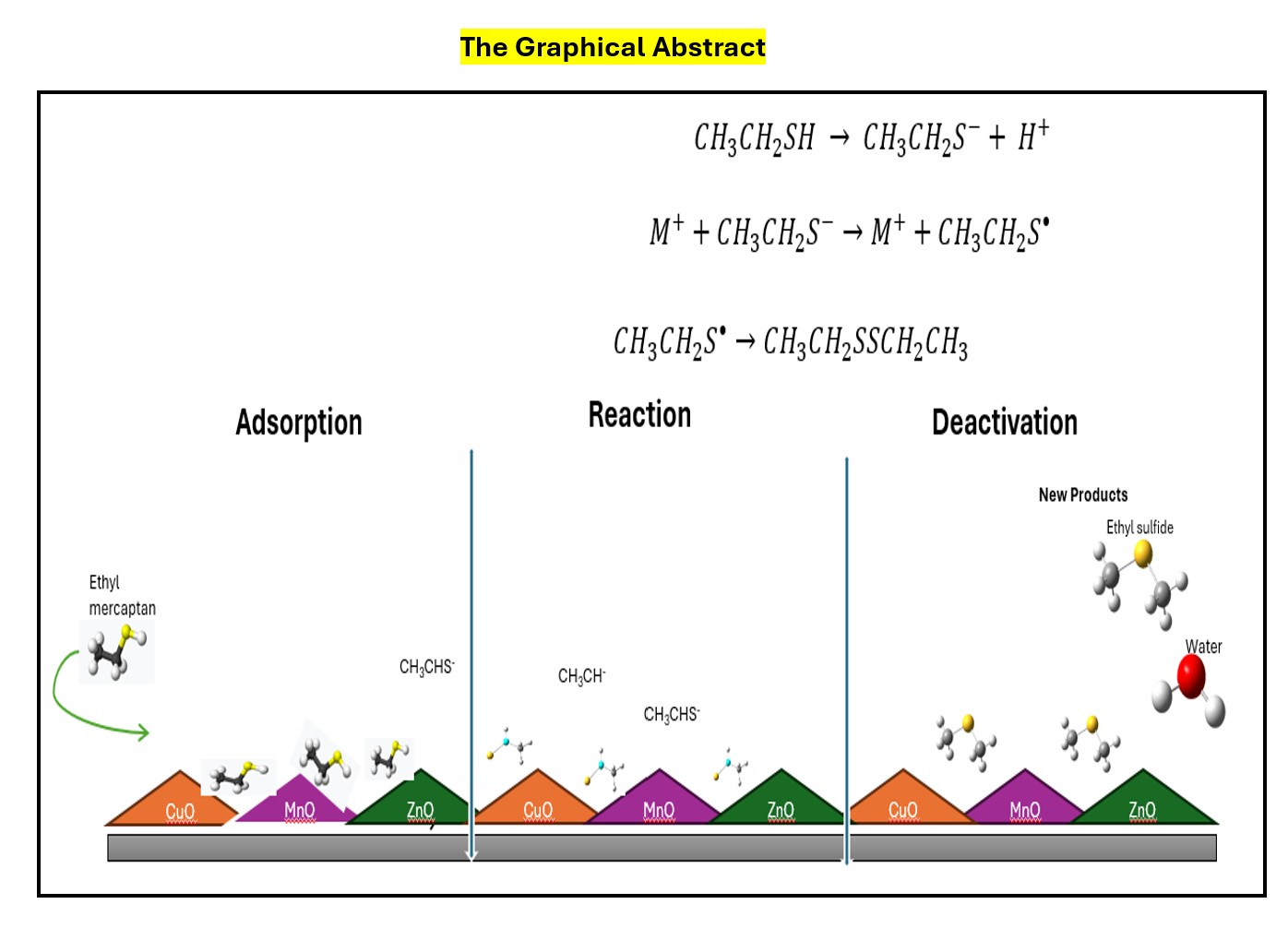

1.1. The Transition Metal Oxides

1.2. Selection of TMOs for the Catalyst Preparation

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Analysis of Breakthrough Time

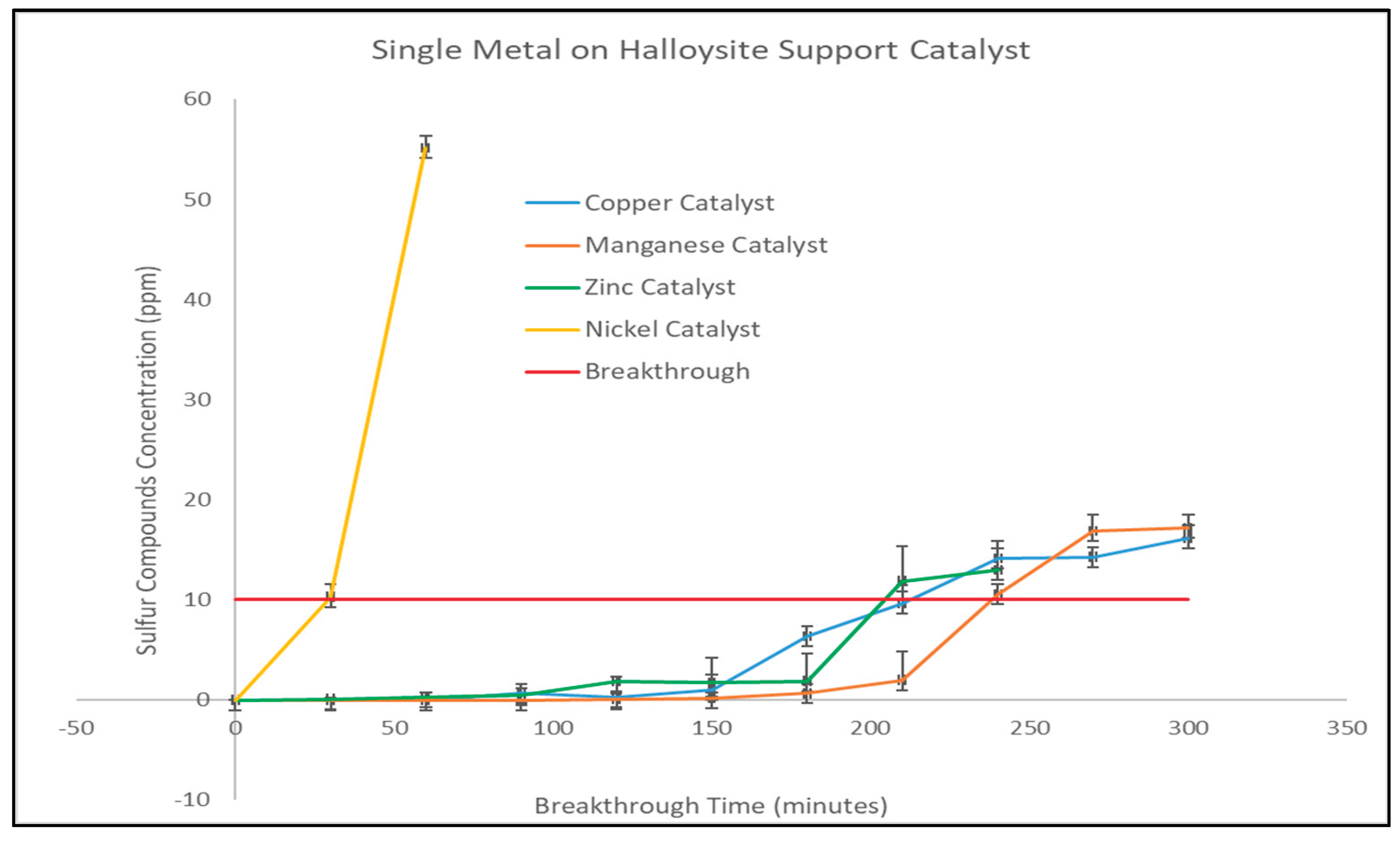

2.1.1. Single Metal on the Halloysite Support

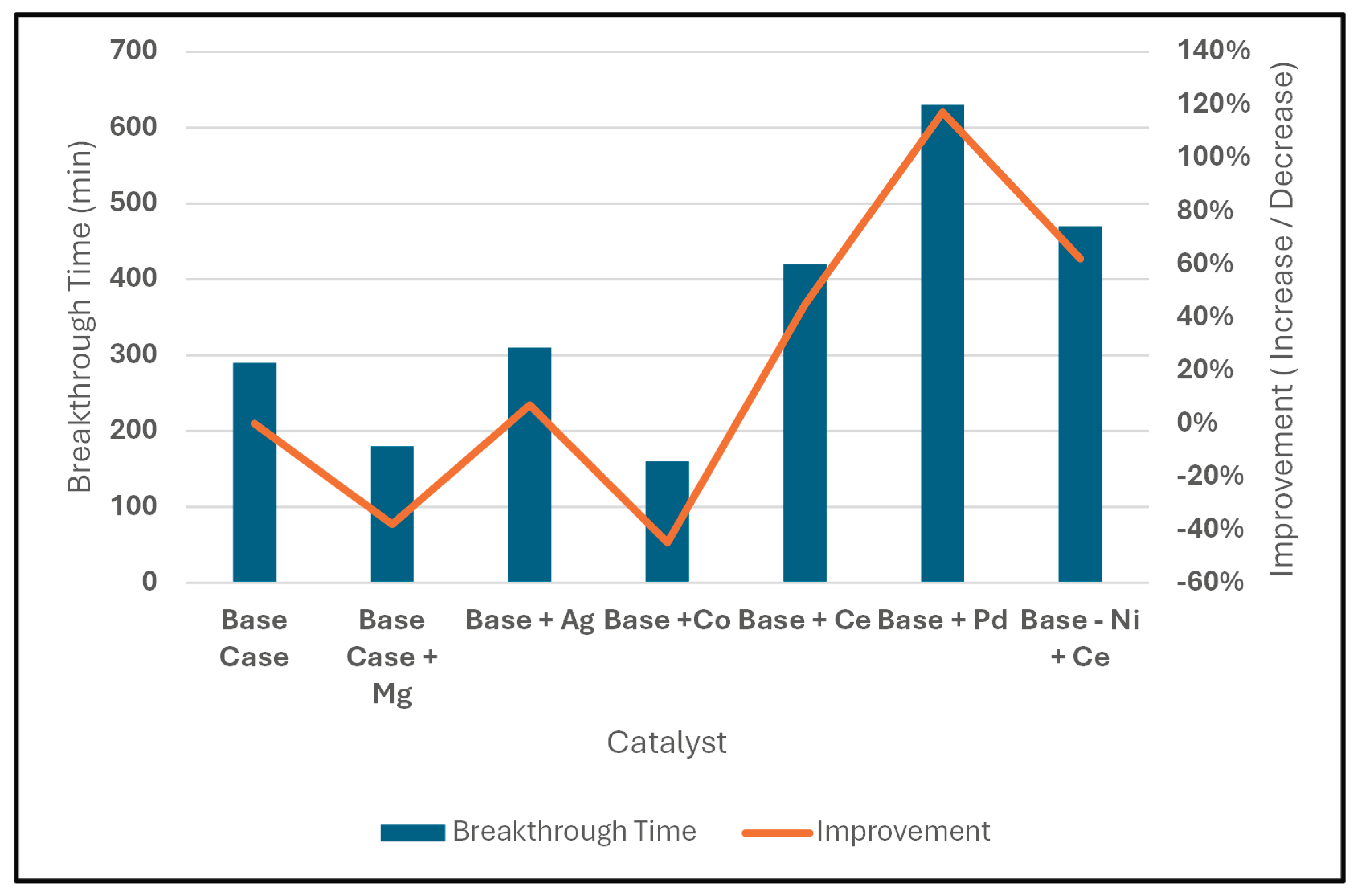

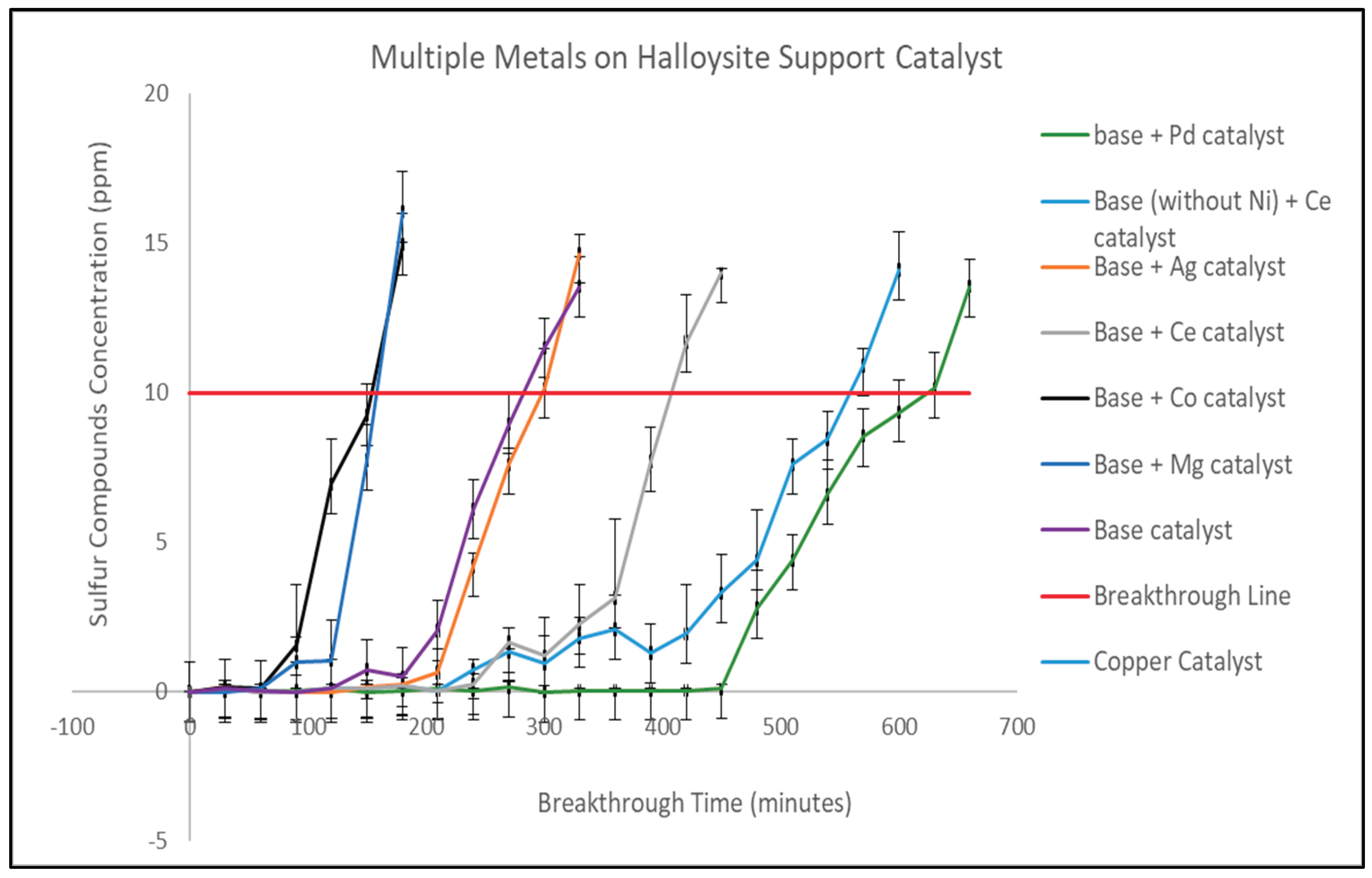

2.1.2. Multiple Metals on the Halloysite Support

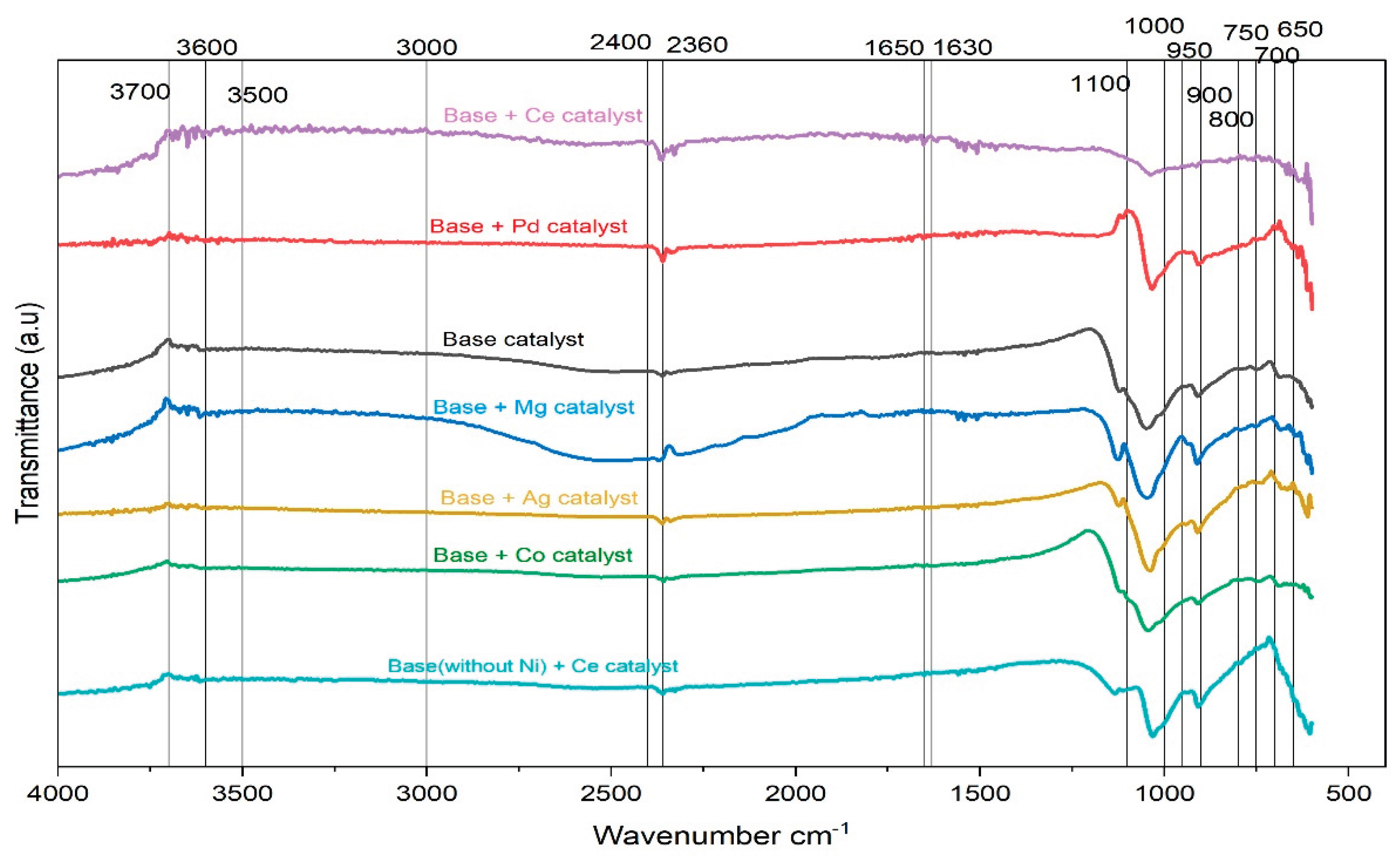

FTIR Analysis and Catalytic Implications of Multi-Metal Catalyst

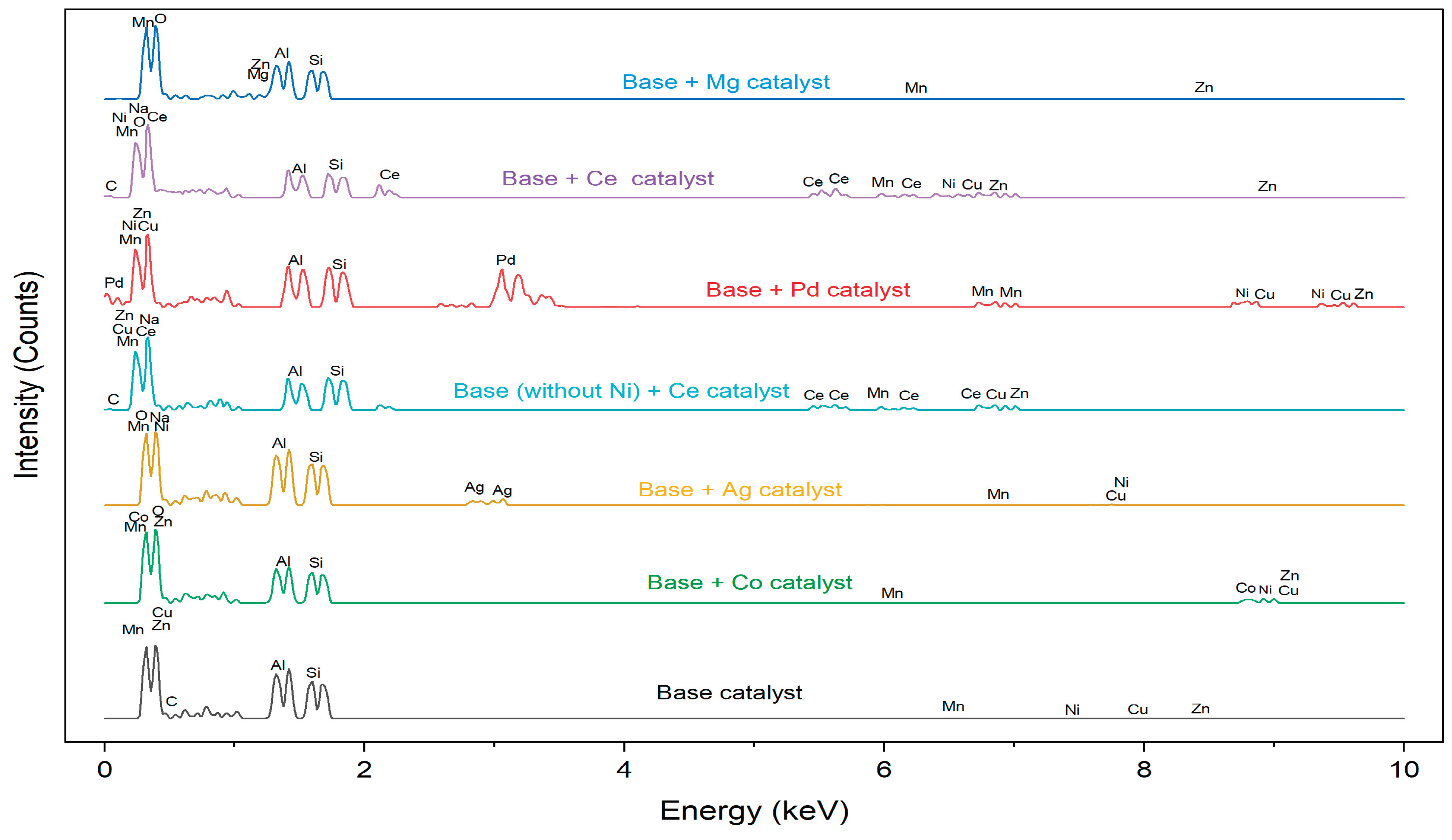

EDS Analysis and Catalytic Implications of Multi-Metal Halloysite Catalyst

2.2. The Analysis of Surface Morphology of the Prepared Catalyst

| Catalyst | Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 36.253 | 0.2165 | 238.8216 |

| Base + Mg | 50.9865 | 0.2544 | 194.1288 |

| Base + Ag | 48.3956 | 0.2420 | 199.9837 |

| Base + Co | 48.6031 | 0.2339 | 192.4566 |

| Base + Ce | 47.5022 | 0.2241 | 188.7434 |

| Base + Pd | 43.2712 | 0.2225 | 205.6373 |

| Base + Ce -Ni | 48.5709 | 0.2312 | 190.4318 |

2.3. Performance Summary

| Metal Oxide | Testing Conditions | Breakthrough | Improvement | Sulphur Capacity (q) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flowrate(mL/min) | Pressure (psi) | Temp (OC) | (mins) | (%) | mg S/g | |

| Base Case | 36 | 200 | 25 | 290 | 0% | 3967.2 |

| Base Case + Mg | 36 | 200 | 25 | 180 | -38% | 2462.2 |

| Base Case + Ag | 36 | 200 | 25 | 310 | 7% | 4240.8 |

| Base Case + Co | 36 | 200 | 25 | 160 | -45% | 2188.8 |

| Base Case + Ce | 36 | 200 | 25 | 420 | 45% | 5745.6 |

| Base Case + Pd | 36 | 200 | 25 | 630 | 117% | 8618.4 |

| Base Case - Ni +Ce | 36 | 200 | 25 | 570 | 62% | 7797.6 |

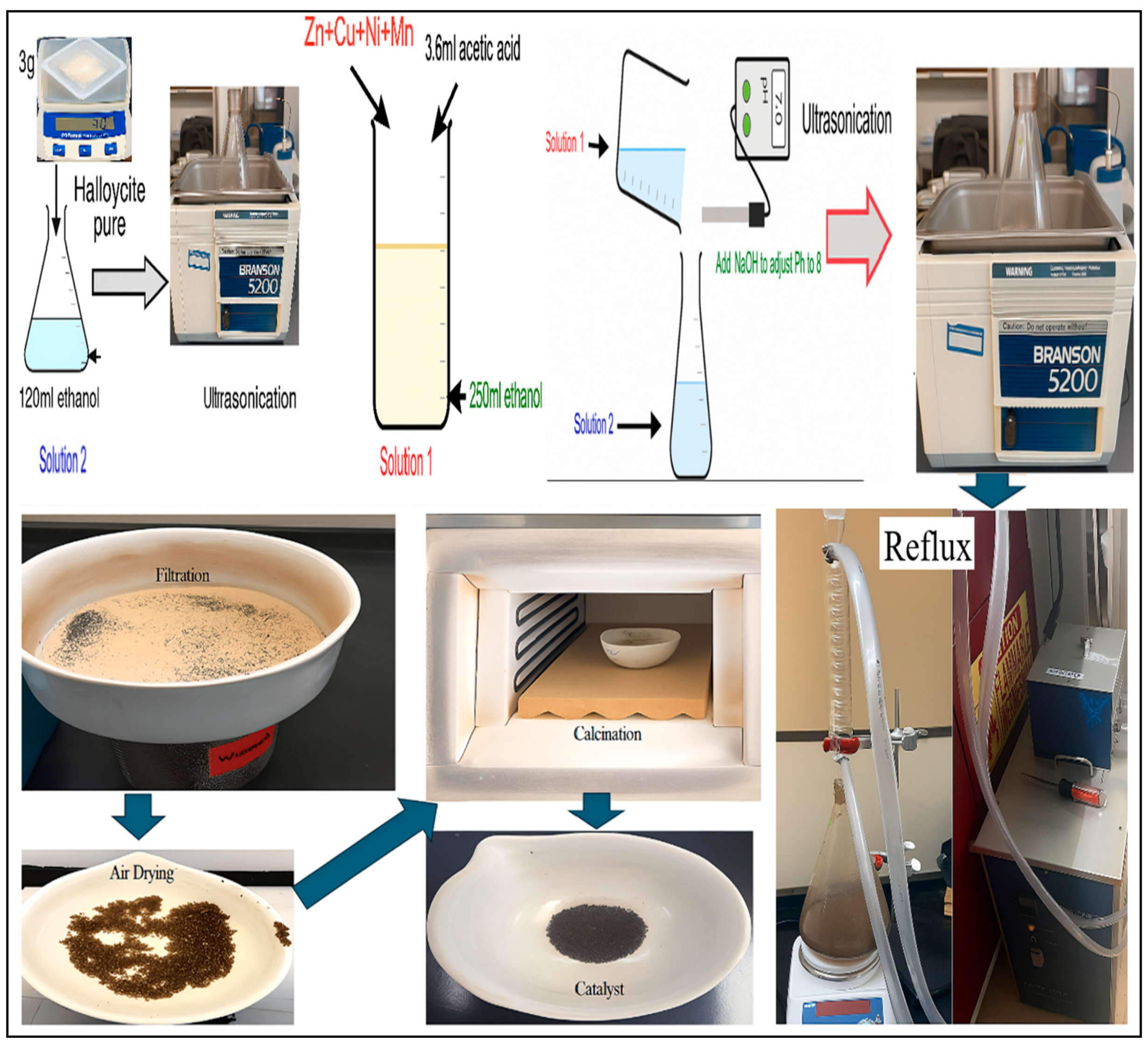

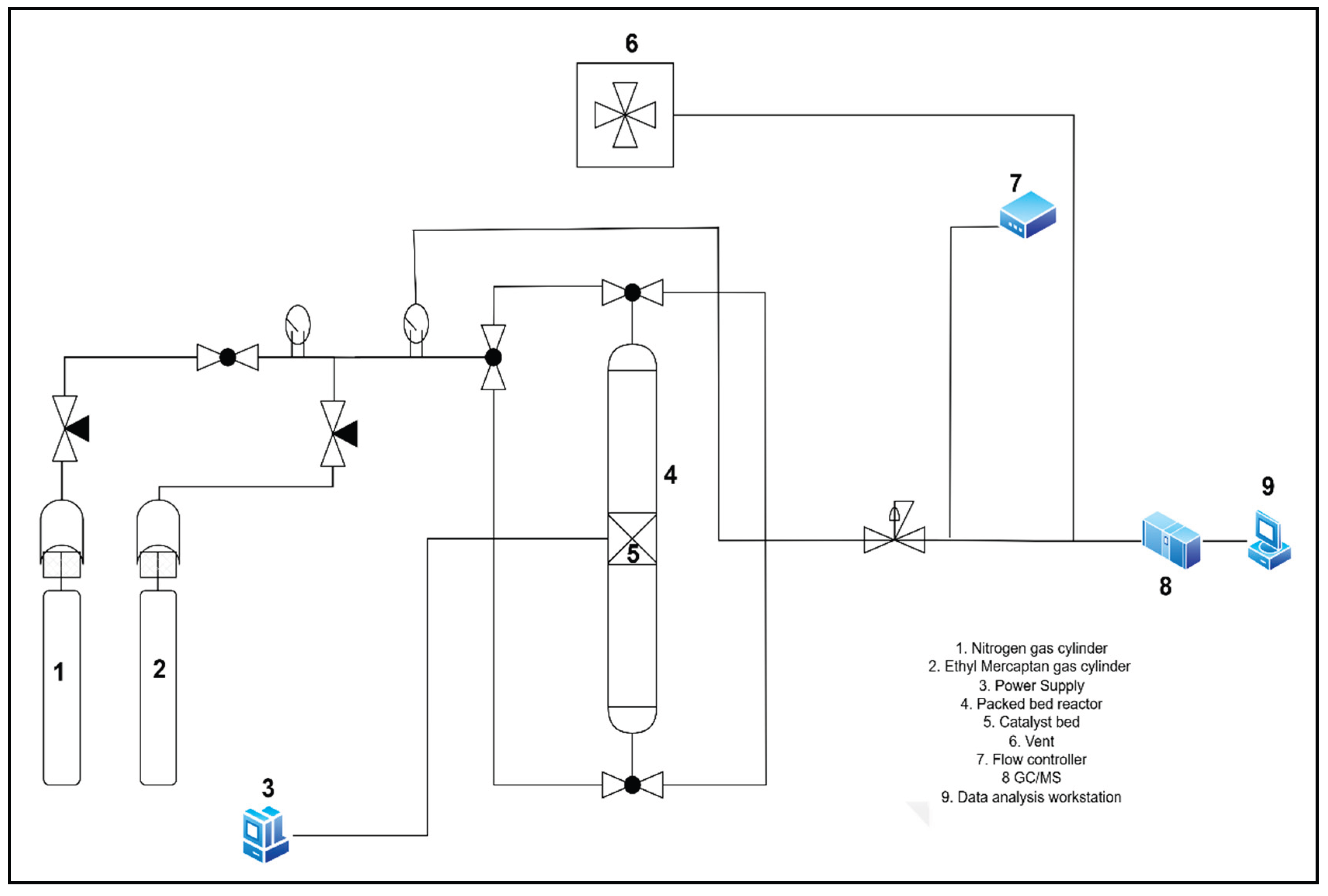

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Catalyst Preparation

3.2. Methods

4. Conclusions

- Metals with smaller bandgaps exhibited superior sulfur adsorption due to enhanced electron transfer and stronger surface sulfur interactions. Narrow bandgap oxides provided more active sites and faster charge mobility, leading to longer breakthrough times and better adsorption performance. In contrast, wider bandgap oxides limited charge exchange, resulting in weaker adsorption and reduced desulfurization efficiency.

- The Mg-modified catalyst is good for high dispersion and adsorption-dependent reactions since it has the largest surface area and pore volume. The smallest pores are seen in Ce-modified catalysts (Ce and Ce-Ni), which may increase catalytic stability and selectivity. With its moderate surface area and lowest pore volume, the Pd-modified catalyst exhibits a denser structure that may be advantageous for oxidation or hydrogenation processes. All things considered, added metals greatly improve texture and increase catalyst efficiency according to reaction needs.

- The breakthrough study demonstrates the influence of metal oxides and band gaps on the adsorption capabilities of the base catalyst. Composed primarily of aluminum silicate, zinc, copper, manganese, and nickel. The base catalyst achieved a breakthrough time of 290 minutes, reducing sulfur compounds concentration to a minimum of 10 ppm.

- The results indicate that optimal catalytic performance is attained when the base catalyst was modified with palladium oxide, extending the breakthrough time from 290 to 630 minutes and an improvement of nearly 117%. Addition of palladium oxide to the base catalyst showed the highest performance improvement, followed by the substitution of nickel oxide by cerium oxide. The superior performance of the modified catalyst is likely due to its chemical composition and metal band gap, which significantly enhances its catalytic activity in sulfur compounds adsorption (removal from natural gas stream) capacity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Future Work

References

- Zhao, S.; Yi, H.; Tang, X.; Gao, F.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, Y. Methyl mercaptan removal from gas streams using metal-modified activated carbon. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 87, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhu, J.; He, J.; Hu, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, D. Catalytic oxidation/photocatalytic degradation of ethyl mercaptan on α-MnO2@ H4Nb6O17-NS nanocomposite. Vacuum 2020, 182, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric chemistry and physics: from air pollution to climate change; John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson-Pitts, B.J.; Pitts, J.N., Jr. Chemistry of the upper and lower atmosphere: theory, experiments, and applications; Elsevier, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, S.E.; Mishchenko, M.I.; Lacis, A.A.; Zhang, S.; Perlwitz, J.; Metzger, S.M. Do sulfate and nitrate coatings on mineral dust have important effects on radiative properties and climate modeling? Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2007, 112(D6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkova, S.; Bagreev, A.; Bandosz, T.J. Activated Carbons as Adsorbents of Methyl Mercaptan. In Fuel Chemistry Deivienv Preprints; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, E.; Van Veen, J.R. On novel processes for removing sulphur from refinery streams. Catalysis today 2006, 116(4), 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbroko, O.W.; Piler, K.; Benson, T.J. A comprehensive review of H2S scavenger technologies from oil and gas streams. ChemBioEng Reviews 2017, 4(6), 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaheb, H.R.; Ghaemmaghami, F.; Mokhtarani, B. A review on removal of sulfur components from gasoline by pervaporation. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2012, 90(3), 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, L.; He, J.; 10. Adsorption and separation of ethyl mercaptan from methane gas on HNb3O8 nanosheets. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2021, 60(23), 8504–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhikov, A.; Hulea, V.; Tichit, D.; Leroi, C.; Anglerot, D.; Coq, B.; Trens, P. Methyl mercaptan and carbonyl sulfide traces removal through adsorption and catalysis on zeolites and layered double hydroxides. Applied Catalysis A: General 2011, 397(1-2), 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, H.E.; ZHAO, J.B.; LAN, Y.X. Adsorption and photocatalytic oxidation of dimethyl sulfide and ethyl mercaptan over layered K1-2xMnxTiNbO5 and K1-2xNixTiNbO5. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology 2009, 37(4), 485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Wu, L.W. The catalytic incineration of ethyl mercaptan over a MnO/Fe2O3 catalyst. Journal of Environmental Science & Health Part A 1998, 33(6), 1119–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Sehon, A.H.; deB. Darwent, B. The thermal decomposition of mercaptans. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1954, 76(19), 4806–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Sang, Å.O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health–A systematic review of reviews. Environmental research 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedighi, M.; Zamir, S. M.; Vahabzadeh, F. Cometabolic degradation of ethyl mercaptan by phenol-utilizing Ralstonia eutropha in suspended growth and gas-recycling trickle-bed reactor. Journal of environmental management 2016, 165, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, G.M. Developing Catalysts for the Removal of Methyl Mercaptan from Natural Gas; University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shingan, B.; Timung, S.; Jain, S.; Singh, V.P. Technological horizons in natural gas processing: A comprehensive review of recent developments. Separation Science and Technology 2024, 59(10-14), 1216–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandosz, T.J. Activated carbon surfaces in environmental remediation; Elsevier, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Tian, Y.; Qin, Z. Adsorption/oxidation of ethyl mercaptan on Fe-N-modified active carbon catalyst. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 393, 124680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Sarkar, U. Alkaline functionalization of granular activated carbon for the removal of volatile organo sulphur compounds (VOSCs) generated in sewage treatment plants. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2018, 6(2), 3510–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Sarkar, U. Alkaline functionalization of granular activated carbon for the removal of volatile organo sulphur compounds (VOSCs) generated in sewage treatment plants. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2018, 6(2), 3510–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagreev, A.; Katikaneni, S.; Parab, S.; Bandosz, T.J. Desulfurization of digester gas: prediction of activated carbon bed performance at low concentrations of hydrogen sulfide. Catalysis Today 2005, 99(3-4), 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Turn, S.Q.; Reese, M.A. Removal of sulfur compounds from utility pipelined synthetic natural gas using modified activated carbons. Catalysis Today 2009, 139(4), 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsi, H.C.; Rood, M.J.; Rostam-Abadi, M.; Chang, Y.M. Effects of sulfur, nitric acid, and thermal treatments on the properties and mercury adsorption of activated carbons from bituminous coals. Aerosol and Air Quality Research 2013, 13(2), 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti-Ramsden, M. G.; Asghar, H. M. A.; Hussain, S. N.; Roberts, E. P. L.; Brown, N. W. Removal of mercaptans from a gas stream using continuous adsorption-regeneration. Water science and technology 2012, 66(9), 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Tian, Y.; Qin, Z. Adsorption/oxidation of ethyl mercaptan on Fe-N-modified active carbon catalyst. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 393, 124680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhao, S.; Yi, H.; Gao, F.; Yu, Q.; Liu, J.; Tang, T.; Tang, X. Efficient catalytic oxidation of methyl mercaptan to sulfur dioxide with NiCuFe mixed metal oxides. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 26, 102252. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Yi, F.; Zhu, J. Characterization of aroma-active compounds and perceptual interaction between esters and sulfur compounds in Xi baijiu. European Food Research and Technology 2020, 246, 2517–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Liao, T.; Dou, Y.; Hwang, S.M.; Park, M.S.; Jiang, L.; Kim, J.H.; Dou, S.X. Generalized self-assembly of scalable two-dimensional transition metal oxide nanosheets. Nature communications 2014, 5(1), 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhu, J.; He, J. Adsorption and conversion of ethyl mercaptan on the surface of Ag-Mn/NS-HNbMoO6. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2022, 97(9), 2496–2510. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Xu, C.; Zhao, W.; Xin, M.; Xiang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Cao, X.; Yuan, H.; Ye, W.; Qiu, L.; Xu, G. Insight into the poisoning effects and mechanisms of CH3SH, CH3CH2SH, CH3SCH3, and CH3CH2SCH2CH3 on Pt/C catalysts in fuel cell HOR. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48(81), 31745–31757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Liu, H.; Chu, B.; Qin, Z.; Dong, L.; He, H.; Bin, L. Catalytic removal NO by CO over LaNi0. 5M0. 5O3 (M= Co, Mn, Cu) perovskite oxide catalysts: tune surface chemical composition to improve N2 selectivity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 369, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q. Development of quinary layered double hydroxide-derived high-entropy oxides for toluene catalytic removal. Catalysts 2023, 13(1), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Wickramathilaka, K. Y.; Njeri, E.; Silva, D.; Suib, S. L. A review on transition metal oxides in catalysis. Frontiers in Chemistry 2024, 12, 1374878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S. C.; Maneesha, P.; Sen, S.; Sen, S.; Sen, S. An introduction to metal oxides. In Optical Properties of Metal Oxide Nanostructures; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Chen, M.; Lv, C.; Wen, X.; Cui, Y.; Hu, X. Recent progresses in the design and fabrication of highly efficient Ni-based catalysts with advanced catalytic activity and enhanced anti-coke performance toward CO2 reforming of methane. Frontiers in Chemistry 2020, 8, 581923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniya, A.; Higashi, S. Towards dense single-atom catalysts for future automotive applications. Nature Catalysis 2019, 2(7), 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrashev, M. V.; Chernev, P.; Kubella, P.; Mohammadi, M. R.; Pasquini, C.; Dau, H.; Zaharieva, I. Origin of the heat-induced improvement of catalytic activity and stability of MnO x electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7(28), 17022–17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VS, M. M.; Jose, S.; Varghese, A. Harnessing transition metal oxide-carbon heterostructures: Pioneering electrocatalysts for energy systems and other applications. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Han, Z.; Zou, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Shu, D.; Suib, S. L. Ultrathin MnO2-coated FeOOH catalyst for indoor formaldehyde oxidation at ambient temperature: new insight into surface reactive oxygen species and in-field testing in an air cleaner. Environmental Science & Technology 2022, 56(15), 10963–10976. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, P.; Roy, D.; Jain, D.; Kumar, S.; Sil, S.; Bhunia, A.; Mandal, S. K. Uncovering the On-Pathway Reaction Intermediates for Metal-Free Atom Transfer Radical Addition to Olefins through Photogenerated Phenalenyl Radical Anion. ACS Catalysis 2024, 14(5), 3420–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, F. Natural Gas Conversion to Olefins via Chemical Looping. In Direct Natural Gas Conversion to Value-Added Chemicals; CRC Press, 2020; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Ethylene Production with Active Lattice Oxygen Under a Cyclic Redox Scheme; North Carolina State University, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; Xiao, F. S. Zeolites Containing Heteroatoms/Metal Nanoparticles for Catalytic Conversion of Light Alkanes. Micro-Mesoporous Metallosilicates: Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Applications 2024, 423–446. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J., Liu, Z., Wang, D., Zhao, L., Shi, D., He, Z., ... & Valtchev, V. Atomically Dispersed Zinc Sites Embedded in a Layered Silicalite-2 Zeolite with Enhanced Stability for Propane Dehydrogenation. Available at SSRN 4975063.

- Ping, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Fan, M.; Ling, L.; Zhang, R. Unraveling the surface state evolution of IrO2 in ethane chemical looping oxidative dehydrogenation. ACS Catalysis 2023, 13(2), 1381–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. P.; Wu, C. P.; Wang, W. W.; Jin, Z.; Liu, J. C.; Ma, C.; Jia, C. J. Boosting reactivity of water-gas shift reaction by synergistic function over CeO2-x/CoO1-x/Co dual interfacial structures. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Heterogeneous Catalyst Design and Synthesis with Controlled and Well-defined Strategies; The University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J. A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Kuhn, M.; Hrbek, J. Reaction of H2S and S2 with metal/oxide surfaces: band-gap size and chemical reactivity. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1998, 102(28), 5511–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. Recent advances in hybrid Cu 2 O-based heterogeneous nanostructures. Nanoscale 2015, 7(25), 10850–10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Rodriguez, J. A.; Brito, J. L. Characterization of pure and sulfided NiMoO 4 catalysts using synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and temperature-programmed reduction (TPR). Catalysis letters 1998, 51, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y. Solvation effects on the band edge positions of photocatalyst surfaces. In Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.; RSC Publishing, 2015; Volume 17, pp. 7075–7084. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. “Prediction of semiconductor band edge positions in aqueous environments from first-principles” 2012, arXiv:1203.1970v1.

- Abdullah, E. A. Band edge positions as a key parameter to a systematic classification of semiconductor photocatalysts. European Journal of Chemistry 2019, 10(1), 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Hedberg, J.; Blomberg, E.; Odnevall, I. Reactive oxygen species formed by metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in physiological media—a review of reactions of importance to nanotoxicity and proposal for categorization. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(11), 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Kuhn, M.; Hrbek, J. Reaction of H2S and S2 with metal/oxide surfaces: band-gap size and chemical reactivity. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1998, 102(28), 5511–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y. Influence of preparation route on metal dispersion and sulfur adsorption efficiency of mixed metal oxides. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 232, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik, A. M.; Shaban, M. Enhanced desulfurization performance of transition-metal-oxide catalysts: Role of preparation method on metal retention and surface chemistry. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9(5), 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Metal leaching and dispersion challenges in supported catalysts prepared via filtration: Impacts on structural stability and reactivity. Catalysis Today 2019, 327, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and oxides. Acta Crystallographica Section A 1976, 32(5), 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Adsorption and activation of thiol and sulfide molecules on metal oxide surfaces: Influence of band structure and surface electron density. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 203, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. T. Energetics of supported metal nanoparticles: Impact of size and support electronic properties on adsorption and reactivity. Journal of Catalysis 2013, 308, 380–390. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, C. H.; Farrauto, R. J. Fundamentals of Industrial Catalytic Processes, 2nd ed.; Wiley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Li, S.; Zhou, R.; Wang, X. Enhanced oxygen mobility and nickel stabilization in MgO-modified Ni catalysts for oxidation and reforming reactions. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2018, 224, 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak, W.; Stojek, Z. Kinetics of silver sulfide film formation on silver in sulfide-containing environments. Corrosion Science 1997, 39(4–5), 889–908. [Google Scholar]

- Briand, L. E.; Mosqueda, H.; Henderson, M. A. The interaction of sulfur- and thiol-containing molecules with silver surfaces: Formation and growth of Ag₂S layers. Surface Science 2002, 515, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hultquist, G.; Leger, P.; Seo, M. Sulphidation of silver and the formation of passivating Ag₂S layers. Corrosion Science 1991, 32(9), 1041–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Topsøe, H.; Nielsen, R. M. Activation of sulfur compounds on nickel-based catalysts: Fundamentals and performance expectations. Journal of Catalysis 1996, 161, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, S. T. Sulfur-resistant catalysts: Structure and reactivity of nickel and transition-metal sulfides. Catalysis Reviews 2003, 45(2), 231–287. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H. C.; Yu Yao, Y. F. Ceria in catalysis: Formation of cerium–silicate phases and their impact on redox properties. Journal of Catalysis 1997, 172, 367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Smith, R. L.; Inomata, H. Effects of silica–ceria interactions on oxygen-vacancy formation and redox behavior in CeO₂–SiO₂ mixed oxides. Chemistry of Materials 2008, 20, 859–867. [Google Scholar]

- Bera, P.; Ray, B. Synergistic interactions in Pd-modified mixed metal oxides: Influence of support band structure on redox and adsorption behavior. Journal of Catalysis 2006, 244, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J. A.; Goodman, D. W.; Bauschlicher, C. W. Electronic and structural effects in Pd-based oxide systems: Charge transfer, band-gap modification, and enhanced adsorption. Surface Science Reports 2000, 35, 1–81. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, W. R.; Raymond, K. N. Silver(I) complexation in aqueous solution: Stability and ligand-exchange behavior. Inorganic Chemistry 2005, 44, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Joussein, E.; et al. Halloysite clay minerals: Structure, properties and uses. Clay Minerals 2005, 40, 383–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, L. E.; Mosqueda, H.; Henderson, M. A. The interaction of sulfur- and thiol-containing molecules with silver surfaces: Formation and growth of Ag₂S layers. Surface Science 2002, 515, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rulíšek, L.; Havlas, Z. Aqueous solvation and hydrolysis of metal acetates: A theoretical study. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2000, 122, 10428–10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposito, G. The Chemistry of Soils, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. T. Ultrathin metal films and supported metal catalysts: Bonding, energetics, and interactions with oxide supports. Surface Science Reports 1997, 27, 1–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Huang, H.; Meng, X.; Shi, L. Desulfurization of liquid hydrocarbon streams via adsorption reactions by silver-modified bentonite. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2013, 52(18), 6112–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Selloni, A. Electronic structure and bonding properties of cobalt oxide in the spinel structure. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2011, 83(24), 245204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhrle, D.; Buck, T.; Hündorf, U.; Schulz-Ekloff, G.; Andreev, A. Phthalocyanines on mineral carriers, 4. Low-molecular-weight and polymeric phthalocyanines on SiO2, γ-Al2O3 and active charcoal as catalysts for the oxidation of 2-mercaptoethanol. Die Makromolekulare Chemie: Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 1989, 190(5), 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Zhou, L.; Luo, X.; Dai, W. Promoting the catalytic activity and SO2 resistance of CeO2 by Ti-doping for low-temperature NH3-SCR: Increasing surface activity and constructing Ce3+ sites. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 473, 145272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Albero, J.; Rodrıguez-Reinoso, F.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A. Improved metal-support interaction in Pt/CeO2/SiO2 catalysts after zinc addition. Journal of Catalysis 2002, 210(1), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Zhou, L.; Luo, X.; Dai, W. Promoting the catalytic activity and SO2 resistance of CeO2 by Ti-doping for low-temperature NH3-SCR: Increasing surface activity and constructing Ce3+ sites. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 473, 145272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Albero, J.; Rodrıguez-Reinoso, F.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A. Improved metal-support interaction in Pt/CeO2/SiO2 catalysts after zinc addition. Journal of Catalysis 2002, 210(1), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Jirsak, T. The bonding of sulfur to Pd surfaces: photoemission and molecular–orbital studies. Chemical physics letters 1998, 296(3-4), 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, A. G.; Charisiou, N. D.; Goula, M. A. Removal of hydrogen sulfide from various industrial gases: A review of the most promising adsorbing materials. Catalysts 2020, 10(5), 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.E.; Mishchenko, M.I.; Lacis, A.A.; Zhang, S.; Perlwitz, J.; Metzger, S.M. Do sulfate and nitrate coatings on mineral dust have important effects on radiative properties and climate modeling? Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2007, 112(D6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).