1. Introduction

The detection of toxic gases such as carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide (NO), nitrogen dioxide (NO

2), ammonia (NH

3), sulfur dioxide (SO

2), and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) is of paramount importance due to their detrimental effects on both human health and the environment [

1,

2]. These gases are common pollutants originating from various industrial activities, vehicular emissions, and agricultural practices [

3]. In response to this pressing issue, researchers have continually sought advanced materials and methodologies to improve gas sensing technologies. Traditional gas sensing materials often face challenges in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and response time. Therefore, the exploration of new materials and sensing mechanisms is crucial for the development of advanced gas sensors capable of detecting low concentrations of toxic gases with high accuracy. Nowadays, two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as graphene [

4], transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) [

5], MoSi

2N

4 [

6], MXenes [

7], and phthalocyanine [

8], have gained significant attention their unique properties, high surface area, and tunable electronic structure [

9,

10,

11], which make them promising candidates for highly sensitive and selective gas sensors [

12].

Among these materials, the 2D InSe monolayer has emerged as a promising candidate for gas sensing applications [

13]. InSe is a layered material with a van der Waals structure, allowing for easy exfoliation into thin layers with large surface areas. This structural feature enhances the adsorption of gas molecules onto the InSe surface, facilitating interaction and detection at the molecular level [

14]. Additionally, InSe exhibits tunable electronic properties, enabling modulation of its conductivity in the presence of different gases through charge transfer mechanisms [

15]. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in exploring the gas sensing properties of 2D materials using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [

16]. For example, the Cai et al. [

13] and Ma et al. [

17] utilized the DFT method to investigate the adsorption behaviors and sensing properties of InSe monolayer to the CO, NO, NO

2, H

2S, NH

3, and found that InSe monolayer was sensitive to the NO and NO

2. Nevertheless, the InSe monolayer exhibits the poor capture ability towards these toxic gases due to the weak physisorption, which hinders the practical applications. Fortunately, there are several innovative strategies to enhance the performance of InSe-based gas sensors, including atomic doping [

18], surface functionalization [

19], defect engineering [

20], and the design of heterostructures [

21,

22]. Among them, the transition metal (TM) doping is regarded as an effective method to improve the sensitivity and selectivity. For instance, the Ru-modified InSe monolayer exhibits stable chemisorption and showcases the superior sensitivity for the NH

3, NO

2, and SO

2 [

23]. Also, the sensitivity of InSe monolayer to the CO

2 molecule can be enhanced after the doping of Pt, Ag, Au and Pd atoms [

24].

Apart from these noble metal atoms, the doping of low-cost TM atoms into 2D materials has been also widely applied in the gas sensors. Nickel (Ni) stands out among the TM elements due to its robust catalytic properties in interacting with gases. It is commonly utilized as a dopant to boost the adsorption and sensing capabilities of specific surfaces towards gas molecules. Consequently, the Ni modified InSe (Ni-InSe) monolayer has a great potential to be a promising sensing materials for the toxic gases. In this work, the first-principle calculations are employed to explore the adsorption mechanism and sensing performance of InSe monolayer towards 12 kinds of gases (CO, NO, NO2, NH3, SO2, H2S, H2O, CO2, CH4, H2, O2 and N2). Firstly, the investigation focuses on the potential stable adsorption of twelve gases on the Ni-InSe surface through the analyses of geometrical optimization, adsorption energy, charge density difference, and density of states. Then, the sensing properties of InSe monolayer to the target toxic gases are evaluated by analyzing the changes in conductivity, work function and recovery time before and after gas adsorption. In conclusion, this study aims to provide theoretical guidance for achieving online monitoring of Ni-InSe based gas sensors to these toxic gases.

2. Computational Method and Details

In this research, all DFT simulations were carried out using the DMol

3 package within the Materials Studio software [

25]. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional, which belongs to the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) family [

26], was employed to handle the electron exchange and correlation effects. Given that PBE has limitations in accurately describing dispersion interactions, a density functional theory correction for dispersion (DFT-D) was incorporated to address this shortfall. Specifically, the Grimme method [

26] was utilized for van der Waals force corrections. To further enhance the precision of the calculations, the double numerical polarization (DNP) basis set [

27] along with DFT semi-core pseudopotentials (DSSP) [

28] was used. This approach involves the simultaneous application of d and p orbital polarization functions in the atomic orbital computations, thereby improving the fidelity of the results. For the Brillouin zone integration [

29], a 7 × 7 × 1 k-point grid combined with a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell was employed to ensure sufficient segmentation accuracy. A vacuum layer of 20 Å was inserted into the computational model to prevent interactions between periodic images. The energy convergence threshold was set to 1.0 × 10

−5 Ha, while the maximum force was constrained to 0.002 Ha/Å, and the maximum displacement was limited to 0.005 Å. The self-consistent field (SCF) calculations were subject to a charge density convergence criterion of 1.0 × 10

−6 Ha. Furthermore, a real-space global orbital cutoff radius of 5.0 Å combined with a Gaussian smearing parameter of 0.005 Ha was implemented.

The binding energy (

Ebin) can be utilized to evaluate the stability of Ni modified InSe monolayer, which can be determined by [

30]:

where the

,

, and

are the total energies of Ni modified InSe, pristine InSe, and a single Ni atom, respectively. To access the interaction strength between the gases and InSe monolayer, the adsorption energy (

Eads) of each system can be calculated by [

31]:

In this equation, the

,

, and

are the total energies of gas adsorbed on Ni-InSe, clean Ni-InSe, and an isolated gas molecule, respectively. Besides, the adsorption strength of Ni-InSe towards the target gases can be also evaluated by the charge transfer (

QT), which can be obtained by the following equation [

32,

33]:

where the

and

represent the charge number of adsorbed gas and isolated gas, respectively. The negative

QT implies that the adsorbed gas gains electrons from the Ni-InSe monolayer, while the positive

QT means that the adsorbed gas losses some electrons transferring to the Ni-InSe monolayer.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Electronic Properties of Ni-InSe Monolayer

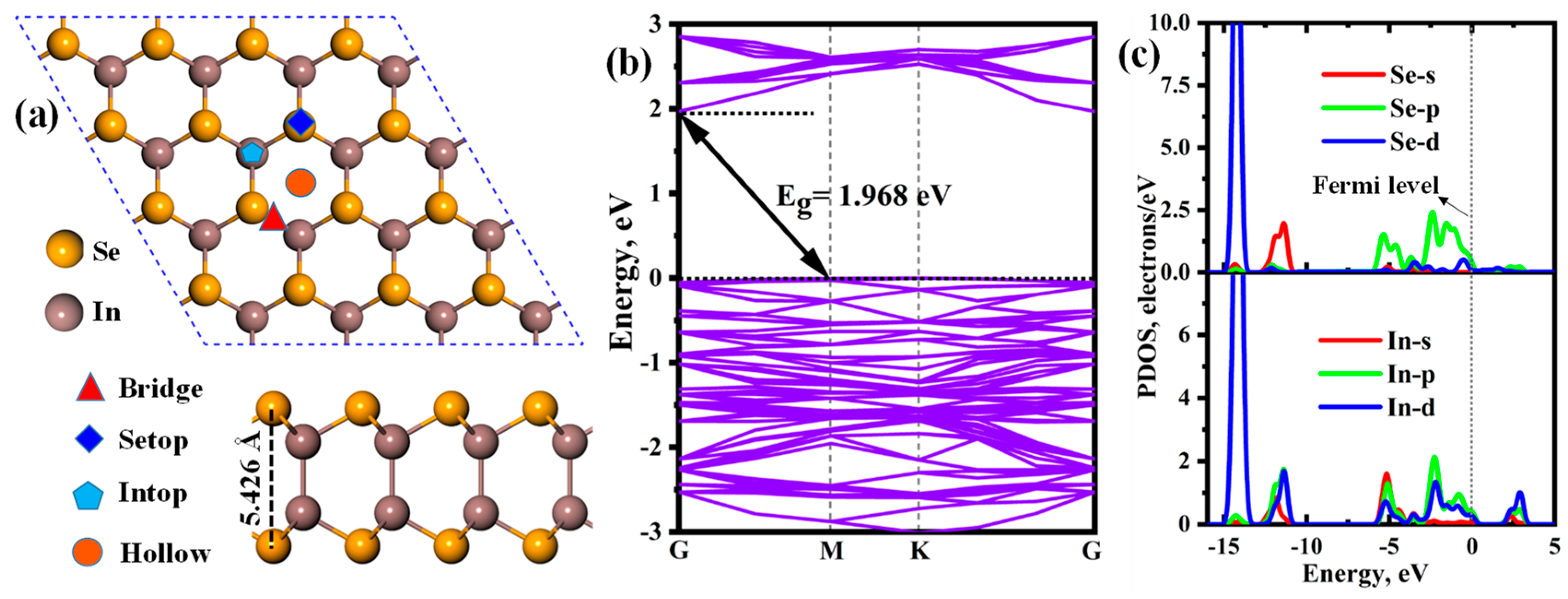

The crystal structure of two-dimensional InSe is a layered hexagonal lattice, with each layer consisting of indium and selenium atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern. The calculated lattice constant of the pristine InSe is approximately 4.07 Å with a space group of P-6m2. As shown in

Figure 1a, the 4×4×1 supercell encompasses 32 In atoms and 32 Se atoms, with respective bond lengths of 2.804 Å and 2.676 Å for the In-In and In-Se bonds. These parameters match well with the previously-reported results. The band structure and partial density of state (PDOS) of InSe monolayer are depicted in

Figure 1(b-c). Notably, the single-layer InSe exhibits a semiconductor characteristic with an indirect bandgap of 1.968 eV, which is consistent with the reported data (2.02 eV) [

14,

34] and experimental result [

35]. From

Figure 1c, obvious hybridizations can be observed between Se-p and In-p, d orbitals in the energy ranging from −6.00 eV to Fermi level. Moreover, the s, p, d orbitals of In atom also overlap with the Se-s orbital, and there exists a significant resonance peak at about –14.30 eV due to the hybridization between Se-d and In-d orbitals. This indicates that the strong In-Se covalent bond is formed and thus the InSe possesses excellent stability.

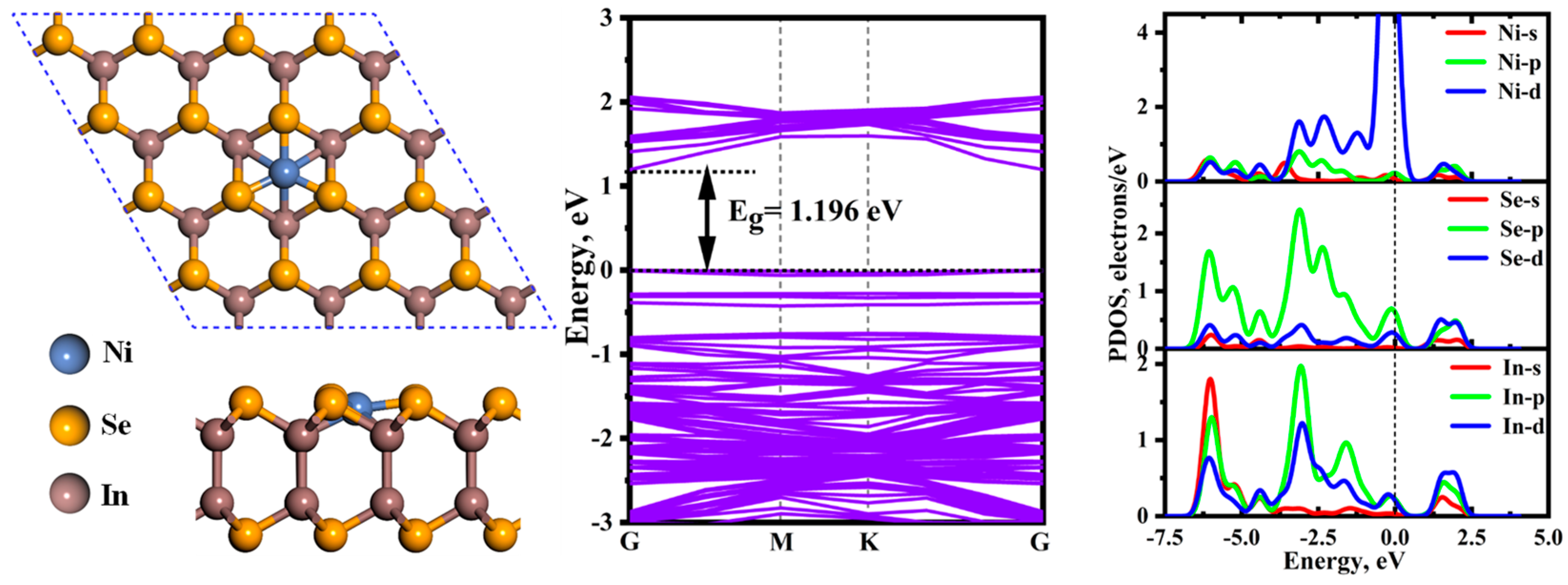

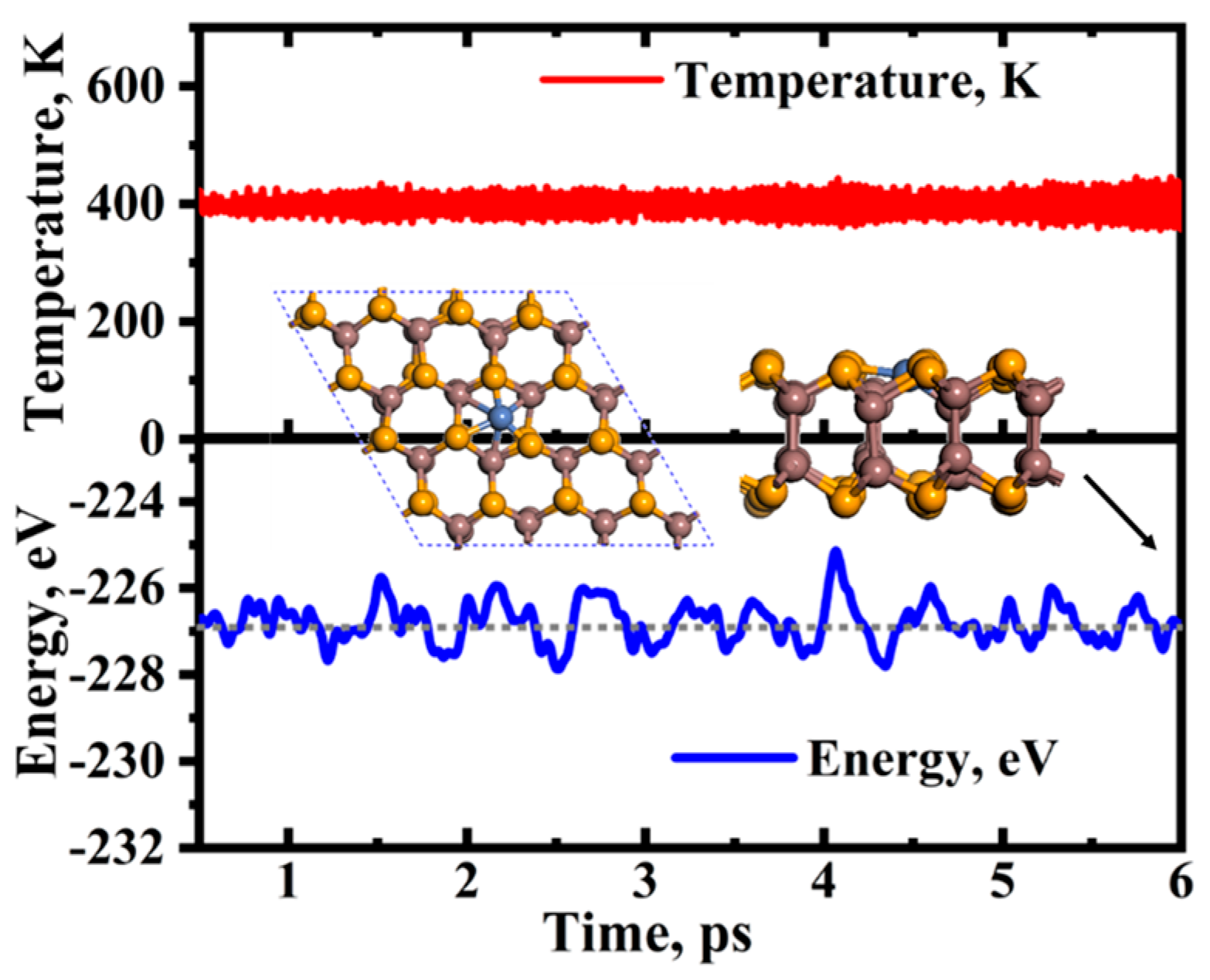

To explore the most thermodynamically stable Ni-InSe monolayer, different doping sites, including Bridge site, Setop site, Intop site and hollow site, are considered for the Ni atom (

Figure 1a). Following full relaxation, the largest binding energy occurs at the hollow site (−3.81 eV), followed by the bridge site (−3.76 eV), the Intop site (−3.25 eV), and the Setop site (−1.83 eV). Thus, the Ni atom is preferentially adsorbed on the hollow site, as depicted in

Figure 2a. Besides, it can be seen from

Figure 2b that that the introduction of the Ni atom causes the conduction band minimum (CBM) to shift towards the Fermi level, leading to a reduction in the bandgap from 1.968 eV to 1.196 eV. This indicates that Ni doping enhances the electrical conductivity of the InSe monolayer and proves beneficial in augmenting its gas-sensitive properties. Additionally, as displayed in the PDOS of Ni-InSe (

Figure 2c), the Ni-d orbital strongly interacts with the Se-p, In-p, d orbitals within the energy of −7.00 eV to 2.50 eV, with several resonance peaks observed at approximately −6.00 eV, −3.08 eV, −0.15 eV, and 1.52 eV. Moreover, the Ni-p orbital also overlaps with the Se-d and In-s orbital in the whole energy range. As a result, two robust Ni-Se and Ni-In bonds are established within the Ni-InSe monolayer. The stability of Ni-InSe is further assessed through ab initio molecular dynamic simulation at 398 K, as shown in

Figure 3. The temperature and potential energy of Ni-InSe display minimal fluctuations over the 10 ps duration, with no discernible disruption of existing bonding within the material. In conclusion, the Ni-InSe monolayer exhibits exceptional stability and holds promise as a highly efficient sensing material.

3.2. Adsorption of Different Gases on Ni-InSe Monolayer

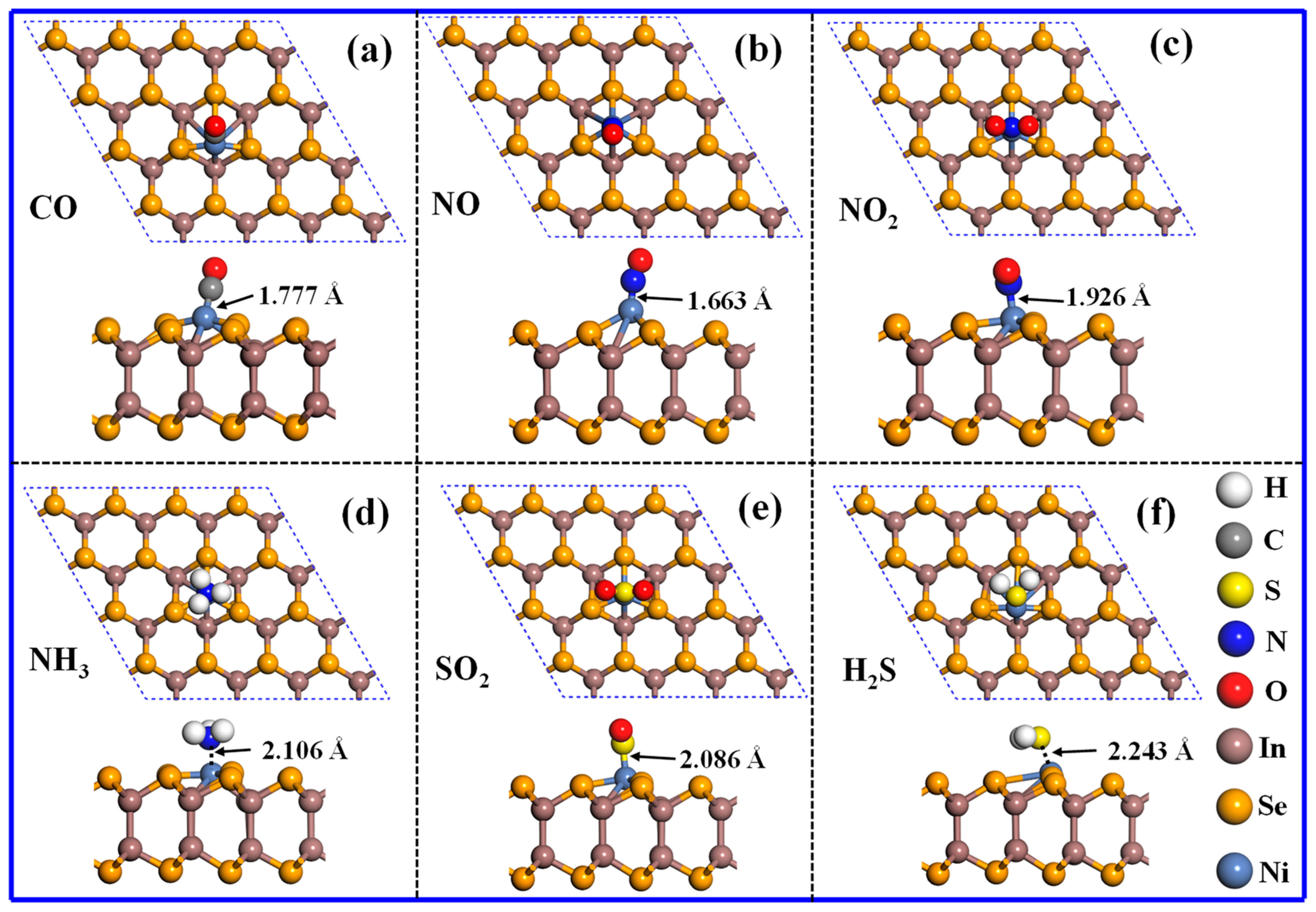

This section discusses the adsorption characteristics of 12 different gases on the surface of Ni-InSe, with the adsorption parameters shown in

Table 1. It is observed that six toxic gases (CO, NO, NO

2, NH

3, SO

2, H

2S) exhibit relatively high adsorption energy values of −0.74 eV to −1.35 eV, with adsorption distances ranging from 1.663 Å to 2.243 Å. As shown in

Figure 4, the CO, NO, H

2S are adsorbed on Ni-InSe monolayer with a small dip angle, while the NO

2, NH

3, SO

2 are perpendicularly adsorbed on the Ni-InSe surface. Evidently, the adsorption distances of these six noxious gases are all less than their respective

Rsum, indicating the formation of chemical bonds in those adsorption systems. Hence, these noxious gases are interpreted as undergoing chemical adsorption, wherein CO, NO, NH

3, H

2S denote a certain amount of electrons to the Ni-InSe and act electron donators. While NO

2 and SO

2 gain 0.223 e and 0.040 e from the Ni-InSe monolayer, respectively, and thus act as electron acceptors.

Additionally, the adsorption energy of N2 on the Ni-InSe monolayer is calculated to be −0.56 eV, with a corresponding charge transfer of 0.071 e and an adsorption distance of 1.828 Å. Thus, the N2 is also chemically adsorbed on the Ni-InSe surface. In contrast, the remaining gases (H2O, CO2, CH4, H2, O2) display low adsorption energy (−0.01 eV to −0.48 eV), large adsorption distances (2.311 Å ~ 3.492 Å), and minimal charge transfer (−0.007 e ~ 0.123 e). Consequently, the adsorption of these gases is categorized as physisorption and primarily depends on Van der Waals' forces. As is well known, a high level of selectivity is typically required for an exceptional sensing material. Based on the variance in adsorption strength outlined above, it is inferred that these toxic gases (CO, NO, NO2, NH3, SO2, H2S) can be effectively differentiated in the presence of H2O, CO2, CH4, H2, O2 and N2. In other words, the Ni-InSe monolayer exhibits outstanding selectivity towards the six noxious gases. Accordingly, only the adsorption of the six hazardous gases is explored in the subsequent section.

3.3. Electronic Properties of Different Adsorption Systems

To further reveal the microscopic bonding mechanism between the Ni-InSe and toxic gases, the total electron density (TED) and charge density difference (CDD) of Ni-InSe monolayer adsorbing CO, NO, NO

2, NH

3, SO

2, and H

2S are calculated, and the corresponding results are detailed in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. It can be seen that a substantial quantity of electrons accumulates in the spaces between the toxic gases and Ni-InSe monolayer, as depicted by

Figure 5(a-f), illustrating that these gases and Ni-InSe share the abundant electrons and thus the strong interactions occur between them. Additionally, as shown in the CDD plots of

Figure 6, the charge redistribution can be observed in the six adsorption systems after full relaxation. It is obvious that a large amount of charges are gathered between the gases and Ni-InSe monolayer, indicating their strong interactions. In particular, conspicuous electron-depleted regions are distributed around the CO, NO, NH

3, and H

2S, with the electron-depleted regions of NH

3 and H

2S being notably larger than those of CO and NO, as illustrated by the bule areas in

Figure 6(a, b, d, f). Conversely, the electron accumulation regions gather around the Ni atoms of Ni-InSe. Consequently, CO, NO, NH

3, and H

2S denote 0.164 e, 0.082 e, 0.246 e, and 0.235 e to the Ni-InSe monolayer. By contrast, for the NO

2 and SO

2 adsorption systems, as shown in

Figure 6(c, e), a large number of electrons are accumulated around the NO

2 and SO

2, with significant electron depletion regions appearing on the Ni-InSe surface. Thus, the Ni-InSe monolayer gain approximately 0.223 e and 0.04 e from the NO

2 and SO

2, respectively, and functions as an electron acceptor. In conclusion, the analyses of both TED and CDD plots suggest that the six toxic gases strongly interact with the Ni-InSe through chemical adsorption.

Figure 7 presents the partial density of states (PDOSs) of different adsorption systems. For the CO adsorption system (

Figure 7a), the strong affinity of Ni-InSe towards NO stems primarily from the hybridizations between C-p and Ni-d orbitals within the energy range of −13.00 eV to 2.75 eV, yielding several discernible resonance peaks at about −12.50 eV, −8.60 eV, −5.80 eV, and 2.20 eV. Additionally, the C-s orbital strongly hybridizes with the Ni-p orbital within the energy range of −10.00 eV to −5.00 eV, resulting in two significant resonance peaks at approximately −8.60 eV and −6.10 eV. Consequently, a strong Ni-C covalent bond is formed in the CO/Ni-InSe system. In the cases of NO, NO

2, and NH

3 adsorption systems, as depicted in

Figure 7(b-d), notable overlap is observed between the N-s, p orbitals of the three gases and Ni-d orbitals within the energy range spanning from −15.00 eV to 2.00 eV. Moreover, the number of resonance peaks for the NO adsorption system exceeds those for the NO

2 and NH

3 adsorption systems. Consequently, Ni-InSe demonstrates stronger adsorption capability towards NO in comparison to NO

2 and NH

3. With regard to the SO

2 and H

2S adsorption systems, the robust adsorption affinity of Ni-InSe for these two gases is primarily attributed to the hybridization between S-p and Ni-d orbitals. Conversely, the orbital overlap between N-s and Ni-s, p is relatively limited at similar energy levels. Particularly, the SO

2 adsorption system (

Figure 7e) displays four pronounced resonance peaks at −14.70 eV, −13.00 eV, −5.80 eV, and −3.05 eV, with comparable resonances also observed in the H

2S adsorption system. Thus, Ni-InSe exhibits comparable affinities for SO

2 and H

2S through chemisorption.

3.4. Effect of H2O on Adsorption

The emission of toxic gases usually occurs in humid atmospheres, making it crucial to study the impact of water molecules in the air. The most stable structure, PDOS, TED, and CDD of a single H

2O adsorbed on Ni-InSe monolayer are displayed in

Figure 8. It can be observed that the Ni-InSe exhibits weak adsorption strength due to the small adsorption energy of −0.48 eV. And the H

2O is adsorbed on the top of Ni atom with the adsorption distance of 2.311 Å, which is slightly smaller than the sum of radii of Ni and O atoms (2.25 Å). Besides, there are a little electrons shared between the H

2O and Ni-InSe, as indicated by the

Figure 8d. Thus, the adsorption of H

2O belongs to physisorption and mainly interacts with Ni-InSe monolayer through the Van der Waals' force.

As shown in the

Figure 8e, the significant electron depletion region is accumulated around the H

2O, while the electron accumulation region is primarily distributed on the Ni-InSe surface. Hence, about 0.123 e of H

2O is transferred to the Ni-InSe monolayer and the H

2O acts an electron donator, which agrees well with the above analysis of Mulliken charge. From

Figure 8c, the adsorption of H

2O is mainly ascribed by the hybridizations between O-p and Ni-s, p, d orbitals in the energy level of −7.50 eV ~ 2.50 eV, which results in three obvious resonance peak at about −6.00 eV, −3.20 eV and 0.00 eV. Furthermore, a significant orbital overlapping between O-s and Ni-s, p, d orbitals can be observed at about −12.50 eV. However, these orbital hybridizations are not strong enough and thus the adsorption of H

2O is relatively weak. As listed in

Table 1, the adsorption strength of six toxic gases (CO, NO, NO

2, NH

3, SO

2, H

2S) is much larger than that of the H

2O molecule. Consequently, the existence of water in the air has no influence on the adsorption, capture, and even sensing properties of Ni-InSe towards these harmful gases.

3.5. Gas Sensing Properties

The applicative efficacy and intrinsic value of gas sensors are intricately linked to their sensitivity, making it imperative to evaluate a sensing material's responsiveness to specific gases. The change in electrical conductivity of gas-sensitive materials after gas adsorption determines the sensitivity of resistive gas sensors to the target gases. And the relationship between electrical conductivity (σ) and band gap (

Eg) can be described by the equation [

3,

36]:

Where A, Eg, KB, T represent the constant, bandgap, Boltzmann constant, and temperature, respectively. Evidently, a smaller bandgap corresponds to higher conductivity. A notable alteration in electrical conductivity can elicit detectable electrical signals, thus facilitating the detection of the target gas molecules. Therefore, if the change in the substrate's bandgap pre and post gas adsorption is substantial, it will yield a discernible change in electrical conductivity, substantiating the material's high sensitivity to gas molecules.

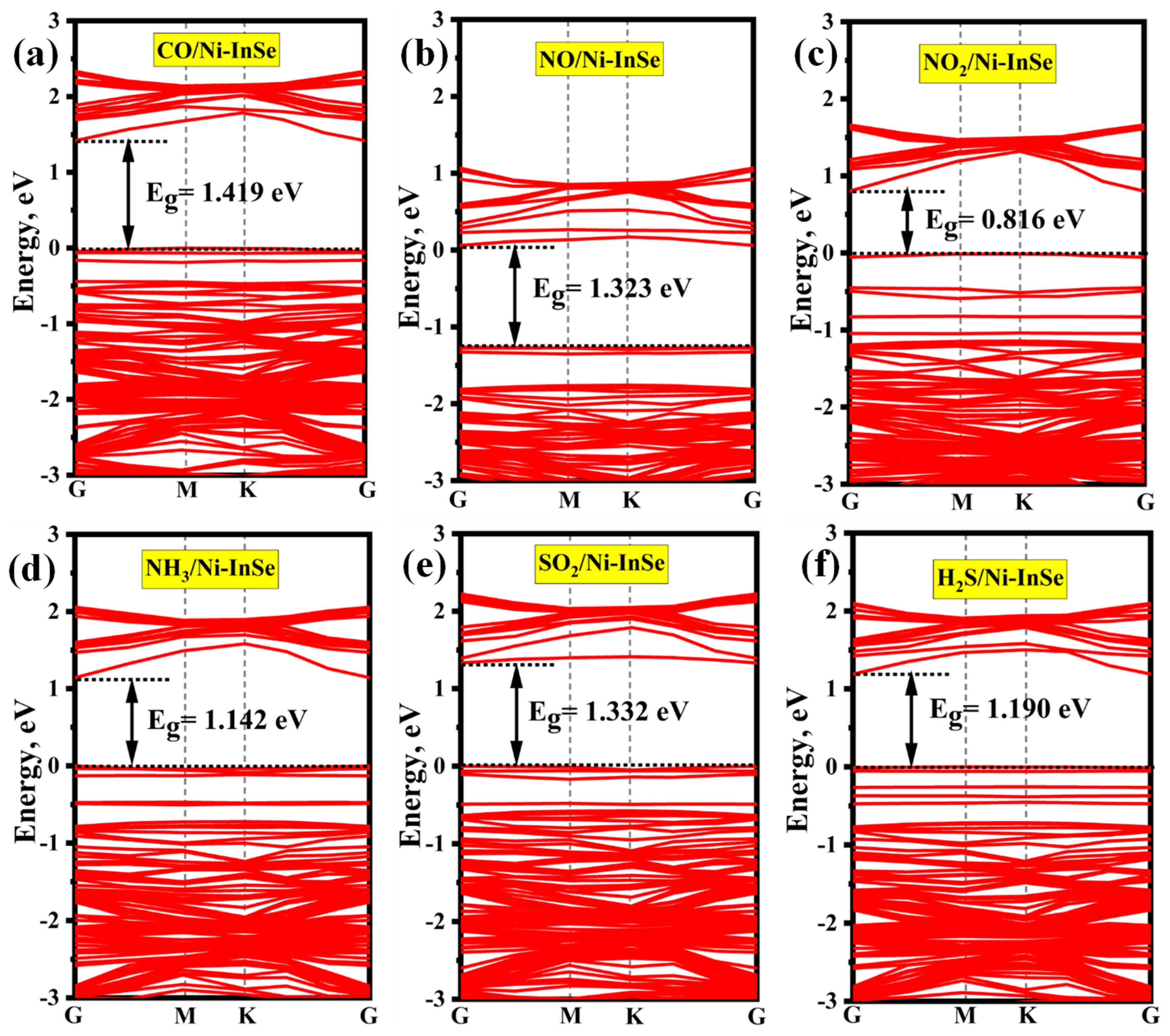

Figure 9 illustrates the band structures of the Ni-InSe monolayer upon the adsorption of various toxic gases. It is evident that the adsorption of CO, NO, and SO

2 causes the bandgap of the Ni-InSe monolayer to vary from 1.196 eV to 1.419 eV, 1.323 eV, and 1.332 eV, respectively. The extent of change in the bandgap adheres to the following order: CO (18.65%) > SO₂ (11.37%) > NO (10.62%), indicating that the Ni-InSe monolayer is highly sensitive to these three gas molecules. In contrast, the bandgap diminishes to 0.816 eV, 1.142 eV, and 1.190 eV for the adsorption of NO₂, NH₃, and H₂S, respectively. It is apparent that the NH₃/Ni-InSe and H₂S/Ni-InSe systems demonstrate minimal rates of change in bandgap, with respective values of −4.52 % and –0.50 %. Nevertheless, the Ni-InSe monolayer displays the highest sensitivity towards NO

2 due to the most substantial rate of change in bandgap (–31.77%). Consequently, it can be concluded that the Ni-InSe-based gas sensor exhibits superior sensitivity toward CO, SO

2, NO and NO

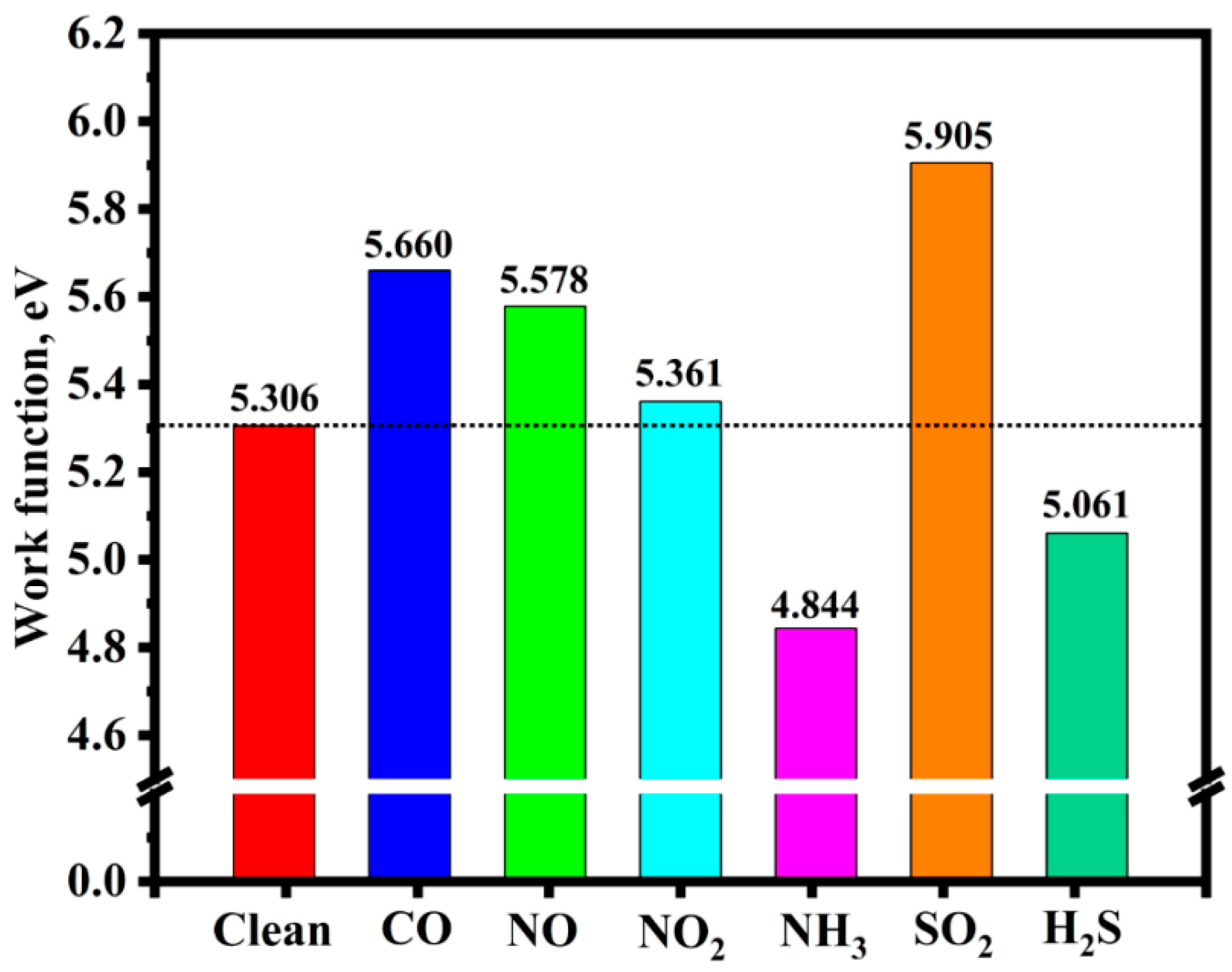

2. Furthermore, the work function (Φ) can also serve as an evaluative measure of gas sensor sensitivity, which is defined as [

37]:

Φ =

, where

and

are the vacuum level and Fermi level of a system, respectively. The work functions of the pristine Ni-InSe monolayer and various adsorption systems are presented in

Figure 10. It is observable that the adsorption of NH

3 and H

2S results in a reduction of the bandgap of Ni-InSe, while the adsorption of other gases leads to an increase in the bandgap of Ni-InSe. The rate of change in work function follows the sequence: SO

2 (11.29 %) > NH

3 (–8.72 %) >CO (6.67%) > NO (5.13%) > H

2S (–4.61 %) > SO

2 (1.03 %), suggesting that the Ni-InSe monolayer can function as an Φ-type gas sensor for SO

2, NH

3, and CO.

Generally, a favorable recovery characteristic is essential for gas sensors with high performance. In simulation calculations, the recovery process is considered as the reverse process of adsorption. According to transition state theory and the Van’t-Hoff Arrhenius expression, the recovery time (τ) can be calculated using the following equation [

38]:

where

υ0 is the attempt frequency (10

12 s

−1),

KB is the Boltzmann constant (8.62×10

−5 eV/K),

T is the work temperature (K), and

Eads is the adsorption energy of the system. The higher magnitude of the adsorption energy signifies a greater barrier for the desorption process. Consequently, the desorption process becomes more challenging, leading to an extended desorption time.

Table 2 presents the calculated recovery times of various adsorption systems at temperatures of 298 K, 348 K, and 398 K. It is evident that the recovery times for CO, NO, NO

2, NH

3 at room temperature are excessively lengthy, ranging from 7.80×10

3 s to 6.67×10

10 s. Even at an elevated temperature of 398 K, the recovery times for CO and NO remain prolonged, hindering the timely release of adsorbed CO and NO from the Ni-InSe surface. Conversely, NO

2 and NH

3 exhibit satisfactory recovery times of 0.79 s and 1.06 s at 398 K, suggesting that Ni-InSe can be effectively employed as a recyclable sensing material for NO

2 and NH

3 at high temperature. In contrast, the adsorption of SO

2 and H

2S on the Ni-InSe monolayer demonstrates moderate recovery times of 3.24 s and 22.72 s at 298 K. This desorption rate is adequate for gas sensor applications; hence, Ni-InSe-based gas sensors exhibit substantial reusability for detecting SO

2 and H

2S at room temperature.

4. Conclusions

In this study, first-principles calculations are employed to investigate the adsorption characteristics and electronic properties of the Ni-InSe monolayer with respect to twelve different gases. This is accomplished by analyzing adsorption energy, electronic structure, work function, and recovery time. The findings indicate that Ni doping enhances the electrical conductivity of the InSe monolayer and strengthens the adsorption capabilities for six toxic gases (CO, NO, NO2, NH3, SO2, H2S). Furthermore, analyses of both TED and CDD plots demonstrate that these toxic gases interact robustly with the Ni-InSe through chemical adsorption. Notably, these gases can be effectively distinguished in the presence of H2O, CO2, CH4, H2, O2, and N2 in the atmosphere. Additionally, the adsorption of CO, NO, NO2, and SO2 results in significant alterations to the bandgap of Ni-InSe, with changes of 18.65%, 11.37%, 10.62%, and –31.77%, respectively. This underscores the superior sensitivity of Ni-InSe to these four hazardous gases. Moreover, an analysis of recovery times indicates that SO2 and H2S on the Ni-InSe monolayer exhibit moderate recovery times of 3.24 s and 22.72 s at 298 K, while NO2 and NH3 demonstrate satisfactory recovery times of 0.79 s and 1.06 s at 398 K. Consequently, the Ni-InSe is positioned as a promising gas sensor for detecting SO2 and H2S at room temperature and for identifying NO2 and NH3 at high temperature. This work provides a theoretical foundation for the industrial application of Ni-InSe based gas sensors for the detection of toxic gases.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of Key Laboratory of General Universities in Guangdong Province (No.2023KSYS007), the Special Projects in Key Fields of Ordinary Universities in Guangdong Province (No.2024ZDZX3030), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No.2017B090921002), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province and Chaozhou (No.2018SS24) and Ceramic Culture Heritage and Innovative Application Research Center (No. PSB230604).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- T.T. Nguyet, C.M. Hung, H.S. Hong, N.X. Thai, P.V. Thang, C. Thi Xuan, N. Van Duy, L. Thi Theu, D. Van An, H. Nguyen, J.Z. Ou, N.D. Chien, N.D. Hoa, Enhanced response characteristics of NO2 gas sensor based on ultrathin SnS2 nanoplates: Experimental and DFT study, Sensor. Actuat. A- Phys., 373 (2024) 115384. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma, M. Yang, G. Deng, H. Xiong, Theoretical insights into gas-sensitive properties of B, Ga and In doped WS2 monolayer towards oxygen-containing toxic gases, Appl. Surf. Sci., 670 (2024) 160725. [CrossRef]

- S. Dolmaseven, N. Yuksel, M.F. Fellah, Au, Ag and Cu Doped BNNT for ethylene oxide gas detection: A density functional theory study, Sensor. Actuat. A- Phys., 350 (2023) 114109. [CrossRef]

- X. Gao, Q. Zhou, J. Wang, L. Xu, W. Zeng, Performance of intrinsic and modified graphene for the adsorption of H2S and CH4: A DFT study, Nanomaterials, 10 (2020) 299. [CrossRef]

- E. Norouzzadeh, S. Mohammadi, M. Moradinasab, First principles characterization of defect-free and vacancy-defected monolayer PtSe2 gas sensors, Sensor. Actuat. A- Phys., 313 (2020) 112209. [CrossRef]

- J. Zeng, L. Xu, X. Luo, T. Chen, S. H. Tang, X. Huang, L. L. Wang, Z-scheme systems of ASi2N4 (A = Mo or W) for photocatalytic water splitting and nanogenerators, Tungsten, 4 (2022) 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hu, W. Liu, D. Li, Q. Wu, Y. Chang, J. Wang, Q. Xia, L. Wang, A. Zhou, Hf3C2O2 MXene: A promising NH3 gas sensor with high selectivity/sensitivity and fast recover time at room temperature, Mater. Today Commun., 40 (2024) 109467. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma, G. Deng, H. Xiong, Density function theory investigation of bimetallic phthalocyanine as a potential sensor and scavenger for nitrogen-containing toxic gases, J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 12 (2024) 113687. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, Z. Peng, T. Chen, L. Xu, Z. Ma, G. Liu, K. Cen, Z. Xu, G. Zhou, Electronic structures and transport properties of low-dimensional GaN nanoderivatives: A first-principles study, Appl. Surf. Sci., 561 (2021) 150038. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang, P. Hu, F. Yang, X. J. Hua, B. Chen, L. Gao, K. S. Wang, Photocatalytic applications and modification methods of two-dimensional nanomaterials: a review, Tungsten, 6 (2024) 77-113. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Wang, S. W. Yang, F. B. Ma, Y. K. Zhao, S. N. Zhao, Z. Y. Xiong, D. Cai, H. D. Shen, K. Zhu, Q. Y. Zhang, Y. L. Cao, T. S. Wang, H. P. Zhang, RuCo alloy nanoparticles embedded within N-doped porous two-dimensional carbon nanosheets: a high-performance hydrogen evolution reaction catalyst, Tungsten, 6 (2024) 114-123. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, T. Chen, X. Dong, L. Huang, Z. Xu, X. Xiao, High gas sensing performance of inorganic and organic molecule sensing devices based on the BC3N2 monolayer, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 24 (2022) 23769-23778. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cai, G. Zhang, Y. W. Zhang, Charge Transfer and Functionalization of Monolayer InSe by Physisorption of Small Molecules for Gas Sensing, J. Phys. Chem. C, 121 (2017) 10182-10193. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen, X. Zhang, H. Cui, J. Tang, S. Pi, Z. Cui, Y. Li, Y. Zhang, High selectivity n-type InSe monolayer toward decomposition products of sulfur hexafluoride: A density functional theory study, Appl. Surf. Sci., 479 (2019) 852-862. [CrossRef]

- W. Zheng, C. Yang, Z. Li, J. Xie, C. Lou, G. Lei, X. Liu, J. Zhang, Indium selenide nanosheets for photoelectrical NO2 sensor with ultra sensitivity and full recovery at room temperature, Sensor. Actuat. B- Chem., 329 (2021) 129127. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, T. Chen, G. Zhou, Design high performance field-effect, strain/gas sensors of novel 2D penta-like Pd2P2SeX (X= O, S, Te) pin-junction nanodevices: A study of transport properties, J. Alloys Compd., 977 (2024) 173417-173428. [CrossRef]

- D. Ma, W. Ju, Y. Tang, Y. Chen, First-principles study of the small molecule adsorption on the InSe monolayer, Appl. Surf. Sci., 426 (2017) 244-252. [CrossRef]

- M. Yang, H. Xiong, Y. Ma, L. Yang, Theoretical investigation of Ag and Au modified CSiN monolayer as a potential gas sensor for air decomposition components detection, J. Mol. Liq., (2024) 125648. [CrossRef]

- A. Junkaew, R. Arróyave, Enhancement of the selectivity of MXenes (M2C, M = Ti, V, Nb, Mo) via oxygen-functionalization: promising materials for gas-sensing and -separation, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 20 (2018) 6073-6082. [CrossRef]

- D. Ma, T. Li, D. Yuan, C. He, Z. Lu, Z. Lu, Z. Yang, Y. Wang, The role of the intrinsic Se and In vacancies in the interaction of O2 and H2O molecules with the InSe monolayer, Appl. Surf. Sci., 434 (2018) 215-227. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, T. Chen, G. Zhou, Z. Xu, X. Xiao, Nonvolatile Electrical Control and Reversible Gas Capture by Ferroelectric Polarization Switching in 2D FeI2/In2S3 van der Waals Heterostructures, ACS Sens., 8 (2023) 1440-1449. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, T. Chen, G. Liu, L. Xie, G. Zhou, M. Long, Multifunctional 2D g-C4N3/MoS2 vdW Heterostructure-Based Nanodevices: Spin Filtering and Gas Sensing Properties, ACS Sens., 7 (2022) 3450–3460. [CrossRef]

- D. Lu, L. Huang, J. Zhang, Y. Zhang, W. Feng, W. Zeng, Q. Zhou, Rh- and Ru-Modified InSe Monolayers for Detection of NH3, NO2, and SO2 in Agricultural Greenhouse: A DFT Study, ACS Appl. Nano Mater., 6 (2023) 14447-14458. [CrossRef]

- W. Cheng, J. Ni, CO2 gas sensor based on Pt-, Ag-, Au- and Pd-doped InSe monolayer: a first-principles study, Semicond. Sci. Technol., 37 (2022) 095011. [CrossRef]

- B. Delley, From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach, J. Chem. Phys., 113 (2000) 7756-7764. [CrossRef]

- S. Grimme, Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction, J. Comput. Chem., 27 (2006) 1787-1799. [CrossRef]

- S. Rao, V. Chirkov, F. Dentener, R. Dingenen, S. Pachauri, P. Purohit, M. Amann, C. Heyes, P. Kinney, P. Kolp, Environmental Modeling and Methods for Estimation of the Global Health Impacts of Air Pollution, Environ. Model. Assess., 17 (2012) 613-622. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, L. Jia, X. Cui, W. Zeng, Q. Zhou, Adsorption and gas-sensing properties of SF6 decomposition components (SO2, SOF2 and SO2F2) on Co or Cr modified GeSe monolayer: a DFT study, Mater. Today Chem., 28 (2023) 101382. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Monkhorst, J.D. Pack, Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations, Phys. Rev. B, 13 (1976) 5188-5192. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, W. Zhou, J. Jiang, W. Zeng, Q. Zhou, First-Principles Investigation of Transition Metal (Co, Rh, and Ir)-Modified WS2 Monolayer Membranes: Adsorption and Detection of SF6 Decomposition Gases, ACS Appl. Nano Mater., 7 (2024) 13379-13391. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma, H. Xiong, J. Zhang, Proposals for gas-detection improvement of the FeMPc monolayer towards ethylene and formaldehyde by using bimetallic synergy, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 26 (2024) 12070-12083. [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, J. Cao, Y. Zhang, J. Liu, D. Chen, P. Jia, Crn (n=1–4) clustered (8, 0) single-walled CNT: Comparison of gas-sensitive properties to air discharge pollutants (CO, NOx), Surf. Interfaces, 44 (2024) 103619. [CrossRef]

- G. Qian, Q. Peng, D. Zou, S. Wang, B. Yan, Q. Zhou, First-Principles Insight Into Au-Doped MoS2 for Sensing C2H6 and C2H4, Front. Mater., 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- W. Ju, T. Li, Q. Zhou, H. Li, X. Li, D. Ma, Adsorption of 3d transition-metal atom on InSe monolayer: A first-principles study, Comp. Mater. Sci., 150 (2018) 33-41. [CrossRef]

- M. Brotons-Gisbert, D. Andres-Penares, J. Suh, F. Hidalgo, R. Abargues, P.J. Rodríguez-Cantó, A. Segura, A. Cros, G. Tobias, E. Canadell, P. Ordejón, J. Wu, J.P. Martínez-Pastor, J.F. Sánchez-Royo, Nanotexturing To Enhance Photoluminescent Response of Atomically Thin Indium Selenide with Highly Tunable Band Gap, Nano Lett., 16 (2016) 3221-3229. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, Y. Ma, H. Xiong, G. Deng, L. Yang, Z. Nie, Highly sensitive and selective sensing-performance of 2D Co-decorated phthalocyanine toward NH3, SO2, H2S and CO molecules, Surf. Interfaces, 36 (2023) 102641. [CrossRef]

- L. Lin, Z. Feng, Z. Dong, H. Tao, C. Hu, Transition metal disulfide (MoTe2, MoSe2 and MoS2) were modified to improve NO2 gas sensitivity sensing, J. Ind. Eng. Chem., 118 (2023) 533-543. [CrossRef]

- N. Naseem, F. Tariq, Y. Malik, W.A. Zahid, A.A. El-Fattah, K. Ayub, J. Iqbal, Sensing ability of carbon nitride (C6N8) for the detection of carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2), Sensor. Actuat. A- Phys., 366 (2024) 114947. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Top and side views of geometrical configuration, (b) band structure and partial density of state (PDOS) of the InSe monolayer.

Figure 1.

(a) Top and side views of geometrical configuration, (b) band structure and partial density of state (PDOS) of the InSe monolayer.

Figure 2.

(a) Top and side views of geometrical configuration, (b) band structure and partial density of state (PDOS) of the In doped InSe monolayer.

Figure 2.

(a) Top and side views of geometrical configuration, (b) band structure and partial density of state (PDOS) of the In doped InSe monolayer.

Figure 3.

Molecular dynamics simulations of Ni-InSe monolayer at 398 K.

Figure 3.

Molecular dynamics simulations of Ni-InSe monolayer at 398 K.

Figure 4.

Atomic configurations of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe.

Figure 4.

Atomic configurations of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe.

Figure 5.

Total electron density (TED) of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe. The iso-value of TED is 0.2 e/Å3.

Figure 5.

Total electron density (TED) of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe. The iso-value of TED is 0.2 e/Å3.

Figure 6.

Charge density difference (CDD) of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe. The iso-value of CDD is ±0.005 e/Å3, the pink and green regions represent the electron gains and losses, respectively.

Figure 6.

Charge density difference (CDD) of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe. The iso-value of CDD is ±0.005 e/Å3, the pink and green regions represent the electron gains and losses, respectively.

Figure 7.

Partial density of states (PDOSs) of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe.

Figure 7.

Partial density of states (PDOSs) of different adsorption systems. (a) CO/Ni-InSe, (b) NO/Ni-InSe, (c) NO2/Ni-InSe, (d) NH3/Ni-InSe, (e) SO2/Ni-InSe, (f) H2S/Ni-InSe.

Figure 8.

(a-b) Atomic structure, (c) PDOSs, (d) TED, and CDD of a single H2O adsorbed on Ni-InSe monolayer after full relaxation.

Figure 8.

(a-b) Atomic structure, (c) PDOSs, (d) TED, and CDD of a single H2O adsorbed on Ni-InSe monolayer after full relaxation.

Figure 9.

Band structures of different adsorption systems.

Figure 9.

Band structures of different adsorption systems.

Figure 10.

Work functions of the clean Ni-InSe monolayer and different adsorption systems.

Figure 10.

Work functions of the clean Ni-InSe monolayer and different adsorption systems.

Table 1.

Adsorption parameters, bandgap (Eg) and work function (Φ) of different gases adsorbed on Ni-InSe monolayer. D and Rsum are the adsorption distance and the theoretical sum of radii of two atoms.

Table 1.

Adsorption parameters, bandgap (Eg) and work function (Φ) of different gases adsorbed on Ni-InSe monolayer. D and Rsum are the adsorption distance and the theoretical sum of radii of two atoms.

| Gas Molecules |

Eads

|

QT, e |

D, Å |

Rsum, Å |

Eg, eV |

Φ, eV |

| CO |

−1.35 |

0.164 |

1.777 (Ni−C) |

2.44 (Ni−C) |

1.419 |

5.66 |

| NO |

−1.26 |

0.082 |

1.663 (Ni−N) |

2.33 (Ni−N) |

1.323 |

5.578 |

| NO2

|

−0.94 |

−0.223 |

1.926(Ni−N) |

2.33 (Ni−N) |

0.816 |

5.361 |

| NH3

|

−0.95 |

0.246 |

2.106 (Ni−N) |

2.33 (Ni−N) |

1.142 |

4.844 |

| SO2

|

−0.74 |

−0.040 |

2.086 (Ni−S) |

2.65 (Ni−S) |

1.332 |

5.905 |

| H2S |

−0.79 |

0.235 |

2.243(Ni−S) |

2.65 (Ni−S) |

1.190 |

5.061 |

| H2O |

−0.48 |

0.123 |

2.311 (Ni−O) |

2.25 (Ni−O) |

1.163 |

5.007 |

| CO2

|

−0.18 |

0.016 |

3.492 (Ni−C) |

2.44 (Ni−C) |

1.201 |

5.306 |

| CH4

|

−0.20 |

0.029 |

3.320 (Ni−C) |

2.44 (Ni−C) |

1.195 |

5.279 |

| H2

|

−0.13 |

0.014 |

2.690 (Ni−H) |

2.30 (Ni−H) |

1.202 |

5.306 |

| N2

|

−0.56 |

0.071 |

1.828 (Ni−N) |

2.33 (Ni−N) |

1.400 |

5.578 |

| O2

|

−0.01 |

−0.007 |

2.354 (Ni−O) |

2.25 (Ni−O) |

1.197 |

5.311 |

Table 2.

Recovery time (τ) of different toxic gases desorbing from the Ni-InSe monolayer at various temperatures.

Table 2.

Recovery time (τ) of different toxic gases desorbing from the Ni-InSe monolayer at various temperatures.

| Materials |

Gases |

Recovery time τ, s |

| 298 |

348 |

398 |

| Ni-InSe |

CO |

6.67×1010

|

3.51×107

|

1.23×105

|

| NO |

2.01×109

|

1.75×106

|

8.92×103

|

| NO2

|

7.80×103

|

40.60 |

0.79 |

| NH3

|

1.15×104

|

56.70 |

1.06 |

| SO2

|

3.24 |

5.17×10-2

|

2.33×10-3

|

| H2S |

22.72 |

0.27 |

0.01 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).