Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

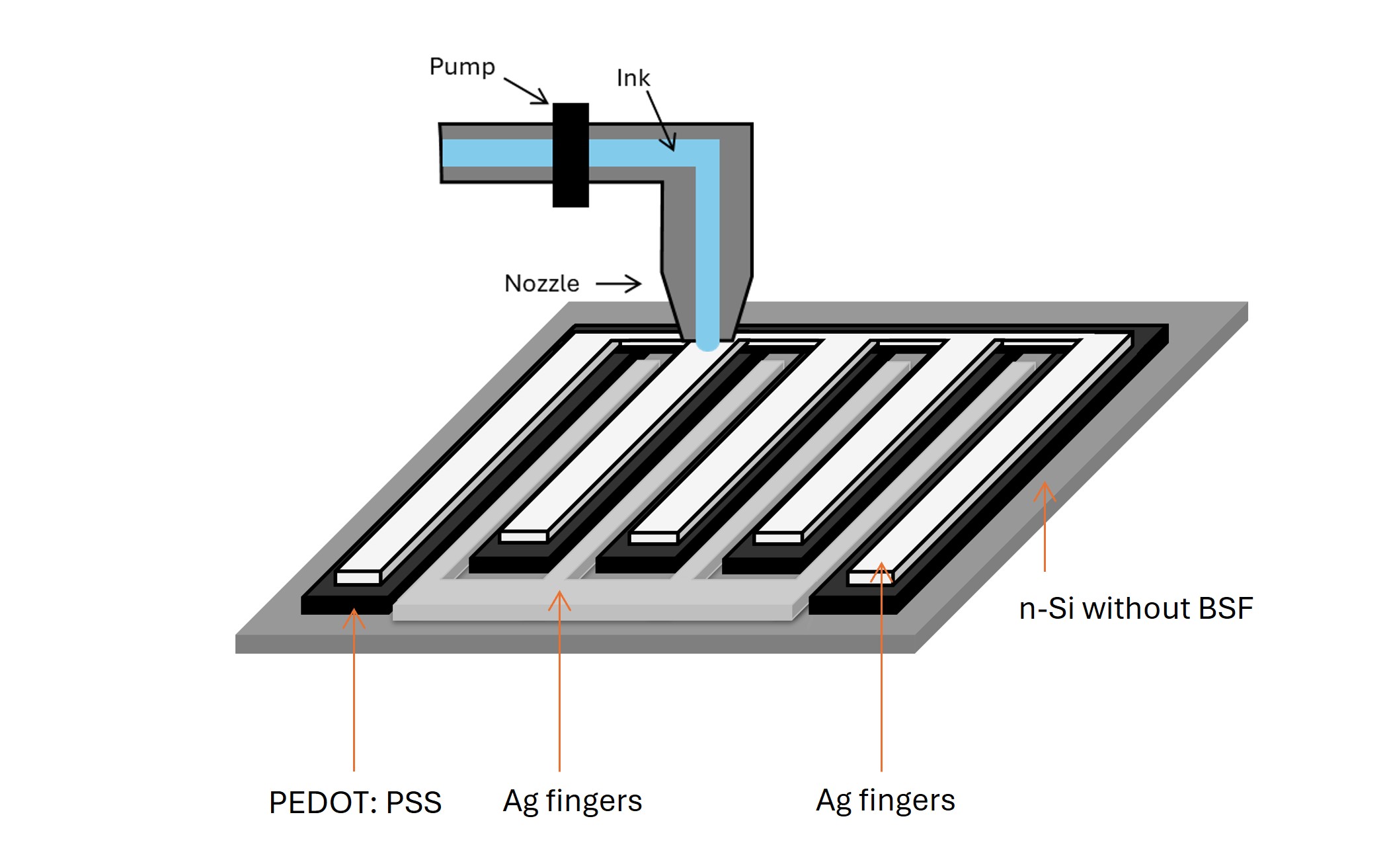

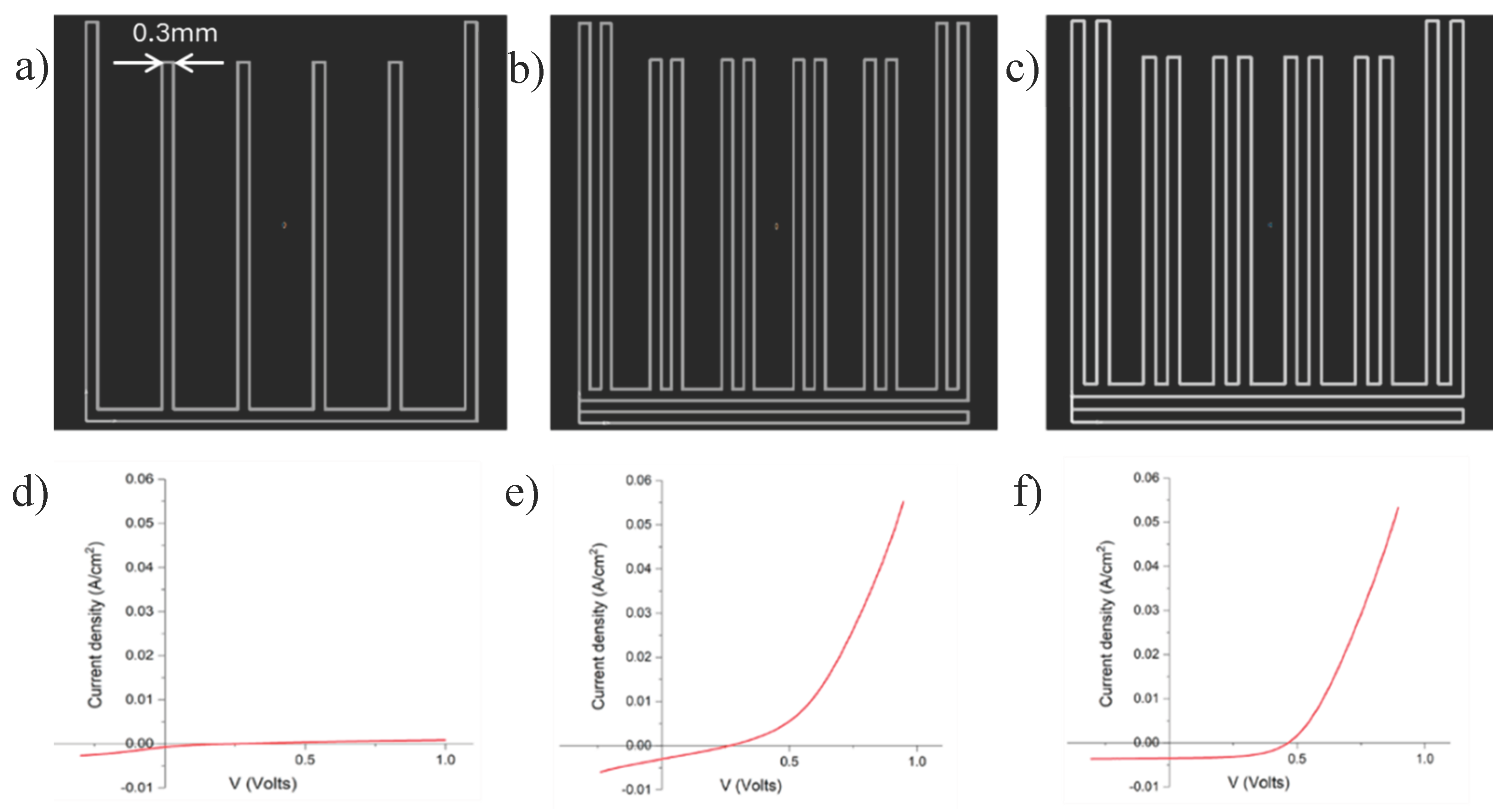

3.1. Inkjet Printing of PEDOT: PSS Layer

| Open Circuit Voltage (V) |

Short Circuit Current (mA/cm2) |

Fill Factor | Power Conversion Efficiency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 mm interval, Figure 2 (a) and (d) | 0.231 | 0.7 | 15.7 | 0.0 |

| 0.3 mm interval, Figure 2 (b) and (e) | 0.284 | 3.07 | 28.9 | 0.3 |

| 0.35 mm interval, Figure 2 (c) and (f) | 0.461 | 3.5 | 55.0 | 0.8 |

| 7% DMSO and 0.5% FS-3100 | 0.557 | 13.0 | 31.3 | 2.3 |

| Front contact, with only metal contact | 0.044 | 2.5 | 34.8 | 0.0 |

| Front contact, with only spin coated TiO2 and metal contact | 0.431 | 2.5 | 32.9 | 0.3 |

| IBC, with PEDOT (without cosolvent) | 0.284 | 3.7 | 28.9 | 0.3 |

| IBC, with PEDOT (without cosolvent) and TiO2 | 0.647 | 3.1 | 40.4 | 0.8 |

| IBC, no passivation, PEDOT ink (with cosolvent) | 0.557 | 13.0 | 31.3 | 2.3 |

| IBC, BQ/ME passivation, PEDOT ink (with cosolvent) | 0.559 | 19.1 | 31.9 | 3.4 |

| IBC, no passivation, PEDOT ink (with cosolvent) and TiO2 ink | 0.690 | 9.91 | 39.9 | 2.7 |

| IBC, BQ/ME passivation, PEDOT ink (with cosolvent) and TiO2 ink | 0.687 | 19.2 | 34.0 | 4.5 |

| Ag/PEDOT: PSS/Si/BSF/Al (both metal contacts are evaporated, PEDOT is printed) | 0.578 | 23.7 | 56.6 | 7.8 |

| Ag/PEDOT: PSS/Si/BSF/Al (Al is evaporated, Ag contact and PEDOT are printed) | 0.576 | 17.6 | 49.7 | 5.1 |

3.2. Effect of Ink Composition

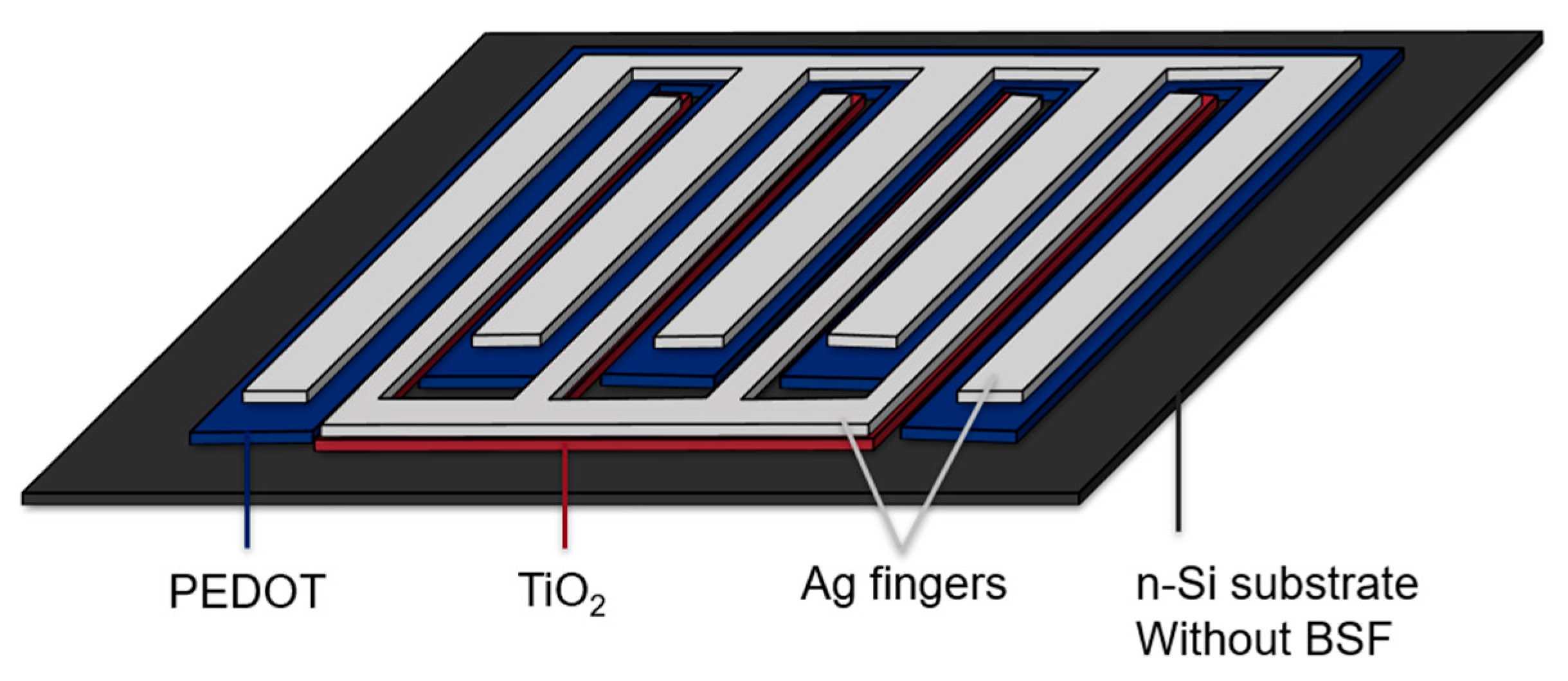

3.3. Electron Transport Layer Printing

3.4. Surface Passivation and Recombination

3.5. Inkjet-Printed Metal Contacts

3.6. Future Work

4. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PEDOT:PSS | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-polystyrene sulfonate |

| IBC | Interdigitated back contact |

References

- Liu, J.; Yao, Y.; Xiao, S.; Gu, X. Review of status developments of high-efficiency crystalline silicon solar cells. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2018, 51, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, S.; Ghosh, D.K.; Banerjee, D.; Maity, S. Analyzing the operational versatility of advanced IBC solar cells at different temperatures and also with variation in minority carrier lifetimes. Journal of Computational Electronics 2024, 23, 1170–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, H.-D.; Kim, N.; Lee, K.; Hwang, I.; Seo, J.H.; Seo, K. Dopant-free all-back-contact Si nanohole solar cells using MoO x and LiF films. Nano letters 2016, 16, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, B.; Singh, M.; Raj, B.; Devi, M. Evolutions of semiconductor solar cells. In Sustainable Energy and Fuels; CRC Press, 2024; pp. 86–107. [Google Scholar]

- Günes, S.; Sariciftci, N.S. Hybrid solar cells. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2008, 361, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, A.; Prajapat, P.; Tawale, J.S.; Pathi, P.; Gupta, G.; Srivastava, S.K. Graphene oxide as an effective interface passivation layer for enhanced performance of hybrid silicon solar cells. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2024, 7, 4710–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Lv, R.; Ansari, A.A.; Lin, J. Recent advances in additive manufacturing for solar cell based on organic/inorganic hybrid materials. InfoMat 2025, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajra, S.; Ali, A.; Panda, S.; Song, H.; Rajaitha, P.M.; Dubal, D.; Borras, A.; In-Na, P.; Vittayakorn, N.; Vivekananthan, V. Synergistic integration of nanogenerators and solar cells: advanced hybrid structures and applications. Advanced Energy Materials 2024, 14, 2400025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Hack, J.; Angel Trujillo, A.D.; Tew, B.; Zide, J.; Opila, R. Effects of Co-Solvents on the Performance of PEDOT:PSS Films and Hybrid Photovoltaic Devices. Applied Sciences 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mens, R.; Adriaensens, P.; Lutsen, L.; Swinnen, A.; Bertho, S.; Ruttens, B.; D'Haen, J.; Manca, J.; Cleij, T.; Vanderzande, D. NMR study of the nanomorphology in thin films of polymer blends used in organic PV devices: MDMO-PPV/PCBM. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2008, 46, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, F.C.; Jørgensen, M.; Norrman, K.; Hagemann, O.; Alstrup, J.; Nielsen, T.D.; Fyenbo, J.; Larsen, K.; Kristensen, J. A complete process for production of flexible large area polymer solar cells entirely using screen printing—first public demonstration. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2009, 93, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-S.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.-S.; Jo, J.; Larsen-Olsen, T.T.; Søndergaard, R.R.; Hösel, M.; Angmo, D.; Jørgensen, M.; Krebs, F.C. Silver front electrode grids for ITO-free all printed polymer solar cells with embedded and raised topographies, prepared by thermal imprint, flexographic and inkjet roll-to-roll processes. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 6032–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; He, D. Solution-processed back-contact PEDOT: PSS/n-Si heterojunction solar cells. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2022, 5, 5502–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Ding, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Yu, J.; Gao, P.; Ye, J.; Shen, W. Realization of interdigitated back contact silicon solar cells by using dopant-free heterocontacts for both polarities. Nano Energy 2018, 50, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yuan, J.; Shen, S.; Gao, M.; Chesman, A.S.R.; Yin, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Angmo, D. Perovskite and organic solar cells fabricated by inkjet printing: progress and prospects. Advanced Functional Materials 2017, 27, 1703704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggenhuisen, T.M.; Galagan, Y.; Biezemans, A.; Slaats, T.; Voorthuijzen, W.P.; Kommeren, S.; Shanmugam, S.; Teunissen, J.P.; Hadipour, A.; Verhees, W.J.H. High efficiency, fully inkjet printed organic solar cells with freedom of design. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3, 7255–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, R.; Diercks, A.; Petry, J.; Welle, A.; Pappenberger, R.; Schackmar, F.; Eggers, H.; Sutter, J.; Lemmer, U.; Paetzold, U.W. Hybrid Two-Step Inkjet-Printed Perovskite Solar Cells. Solar RRL 2024, 8, 2400165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagishi, H.; Noge, H.; Saito, K.; Kondo, M. Fabrication of interdigitated back-contact silicon heterojunction solar cells on a 53-µm-thick crystalline silicon substrate by using the optimized inkjet printing method for etching mask formation. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2017, 56, 040308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeier, N.; Kiefer, F.; Brendemühl, T.; Mettner, L.; Wolter, S.J.; Haase, F.; Peibst, R.; Holthausen, M.; Mispelkamp, D.; Mader, C.; et al. Inkjet-Printed In Situ Structured and Doped Polysilicon on Oxide Junctions. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2021, 11, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, P.C.; Lennon, A. Backsheet metallization of IBC silicon solar cells. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 39th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), 16-21 June 2013, 2013; pp. 2209–2211. [Google Scholar]

- Mirotznik, M.; Larimore, Z.; Parsons, P.; Good, A. Additively Manufactured RF Devices and Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation & USNC/URSI National Radio Science Meeting, 8-13 July 2018, 2018; pp. 1883–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, D.H.; Cuevas, A.; Kerr, M.J.; Samundsett, C.; Ruby, D.; Winderbaum, S.; Leo, A. Texturing industrial multicrystalline silicon solar cells. Solar Energy 2004, 76, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, H.; Csepregi, L.; Heuberger, A.; Baumgärtel, H. Anisotropic Etching of Crystalline Silicon in Alkaline Solutions: I. Orientation Dependence and Behavior of Passivation Layers. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 1990, 137, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hack, J.H.; Iyer, A.; Jones, K.J.; Opila, R.L. Radical-Driven Silicon Surface Passivation by Benzoquinone– and Hydroquinone–Methanol and Photoinitiators. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 21364–21373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Yang, D.; Opila, R.L.; Teplyakov, A.V. Chemical and electrical passivation of Si(111) surfaces. Applied Surface Science 2012, 258, 3019–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K.J.; Gupta, E.; Bonner, C.; Fessaras, T.; Mirotznik, M. Engineered substrates for metasurface antennas. Additive Manufacturing Letters 2024, 9, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotulak, N.A. Developing novel hybrid heterojunctions for high efficiency photovoltaics. Ph.D, University of Delaware, United States -- Delaware, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, J.L.; Kelly, C.A.; Marshall, J.E.; Jenkins, M.J. Effect of thickness on the electrical properties of PEDOT:PSS/Tween 80 films. Polymer Journal 2024, 56, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, X. Simulation and analysis of Si/PEDOT:PSS hybrid interdigitated back contact solar cell. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Electron Devices and Solid-State Circuits (EDSSC), 12-14 June 2019, 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Huang, X.; Chung, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, Y.; Liang, A.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Hole-selective-molecule doping improves the layer thickness tolerance of PEDOT:PSS for efficient organic solar cells. eScience 2025, 5, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, D.E.; Joo, J. Enhancement of electrical conductivity of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/poly(4-styrenesulfonate) by a change of solvents. Synthetic Metals 2002, 126, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanshayeva, L.; Favaron, V.; Lubineau, G. Macroscopic Modeling of Water Uptake Behavior of PEDOT:PSS Films. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 21883–21890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.P.; Leung, K.T. Defect-Minimized PEDOT:PSS/Planar-Si Solar Cell with Very High Efficiency. Advanced Functional Materials 2014, 24, 4978–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrues, T.; Vecchi, S.d.; d'Alonzo, G.; Muñoz, D.; Ribeyron, P.J. Influence of the emitter coverage on interdigitated back contact (IBC) silicon heterojunction (SHJ) solar cells. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 40th Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), 8-13 June 2014, 2014; pp. 0857–0861. [Google Scholar]

- Hermle, M.; Granek, F.; Schultz-Wittmann, O.; Glunz, S.W. Shading effects in back-junction back-contacted silicon solar cells. In Proceedings of the 2008 33rd IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, 11-16 May 2008, 2008; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, A.; Hack, J.; Angel Trujillo, D.A.; Tew, B.; Zide, J.; Opila, R. Effects of Co-Solvents on the Performance of PEDOT: PSS Films and Hybrid Photovoltaic Devices. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, L.V.; Lipomi, D.J. Stretchable conductive polymers and composites based on PEDOT and PEDOT: PSS. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1806133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.P.; Zhao, L.; McGillivray, D.; Leung, K.T. High-efficiency hybrid solar cells by nanostructural modification in PEDOT: PSS with co-solvent addition. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2014, 2, 2383–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Butt, H.J.; Bonaccurso, E. Influence of relative humidity on the nanoscopic topography and dielectric constant of thin films of PPy: PSS. small 2011, 7, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bießmann, L.; Kreuzer, L.P.; Widmann, T.; Hohn, N.; Moulin, J.-F.; Müller-Buschbaum, P. Monitoring the Swelling Behavior of PEDOT:PSS Electrodes under High Humidity Conditions. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 9865–9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Fan, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ouyang, J. Enhancement of the thermoelectric properties of PEDOT: PSS via one-step treatment with cosolvents or their solutions of organic salts. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 7080–7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidian, M.R.; Corey, J.M.; Kipke, D.R.; Martin, D.C. Conducting-polymer nanotubes improve electrical properties, mechanical adhesion, neural attachment, and neurite outgrowth of neural electrodes. small 2010, 6, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.F.; Kwon, H.-C.; Yang, W.; Hwang, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, E.; Ma, S.; Moon, J. La2O3 interface modification of mesoporous TiO2 nanostructures enabling highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 15478–15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-N.; Li, B.; Fu, L.; Li, Q.; Yin, L.-W. MOF-derived ZnO as electron transport layer for improving light harvesting and electron extraction efficiency in perovskite solar cells. Electrochimica Acta 2020, 330, 135280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Khalid, A.; Nawaz, F.; Mehran, M.T. Low-temperature electrospray-processed SnO2 nanosheets as an electron transporting layer for stable and high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2018, 532, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yu, X.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lei, M.; Xu, L.; Tang, Z.; Cui, C. Self-organized fullerene interfacial layer for efficient and low-temperature processed planar perovskite solar cells with high UV-light stability. Advanced science 2017, 4, 1700018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znidi, F.; Morsy, M.; Uddin, M.N. Recent advances of graphene-based materials in planar perovskite solar cells. Next Nanotechnology 2024, 5, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirin, D.N.; Cherniukh, I.; Yakunin, S.; Shynkarenko, Y.; Kovalenko, M.V. Solution-Grown CsPbBr3 Perovskite Single Crystals for Photon Detection. Chemistry of Materials 2016, 28, 8470–8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Denegri, G.; Colodrero, S.; Kramarenko, M.; Martorell, J. All-Nanoparticle SnO2/TiO2 Electron-Transporting Layers Processed at Low Temperature for Efficient Thin-Film Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2018, 1, 5548–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bi, Q.; Ali, H.; Davis, K.; Schoenfeld, W.V.; Weber, K. High-Performance TiO2-Based Electron-Selective Contacts for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Advanced Materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 2016, 28, 5891–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hack, H.J.; Lin, X.; Janotti, A.; Opila, L.R. Electronic Structure Characterization of Hydrogen Terminated n-type Silicon Passivated by Benzoquinone-Methanol Solutions. Coatings 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.R. Understanding and optimizing the performances of PEDOT: PSS based heterojunction solar cells; University of Delaware, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.