Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data Source, Search and Extraction

3. Pressure Injury Prevention in Perioperative Setting

3.1. Preoperative Phase

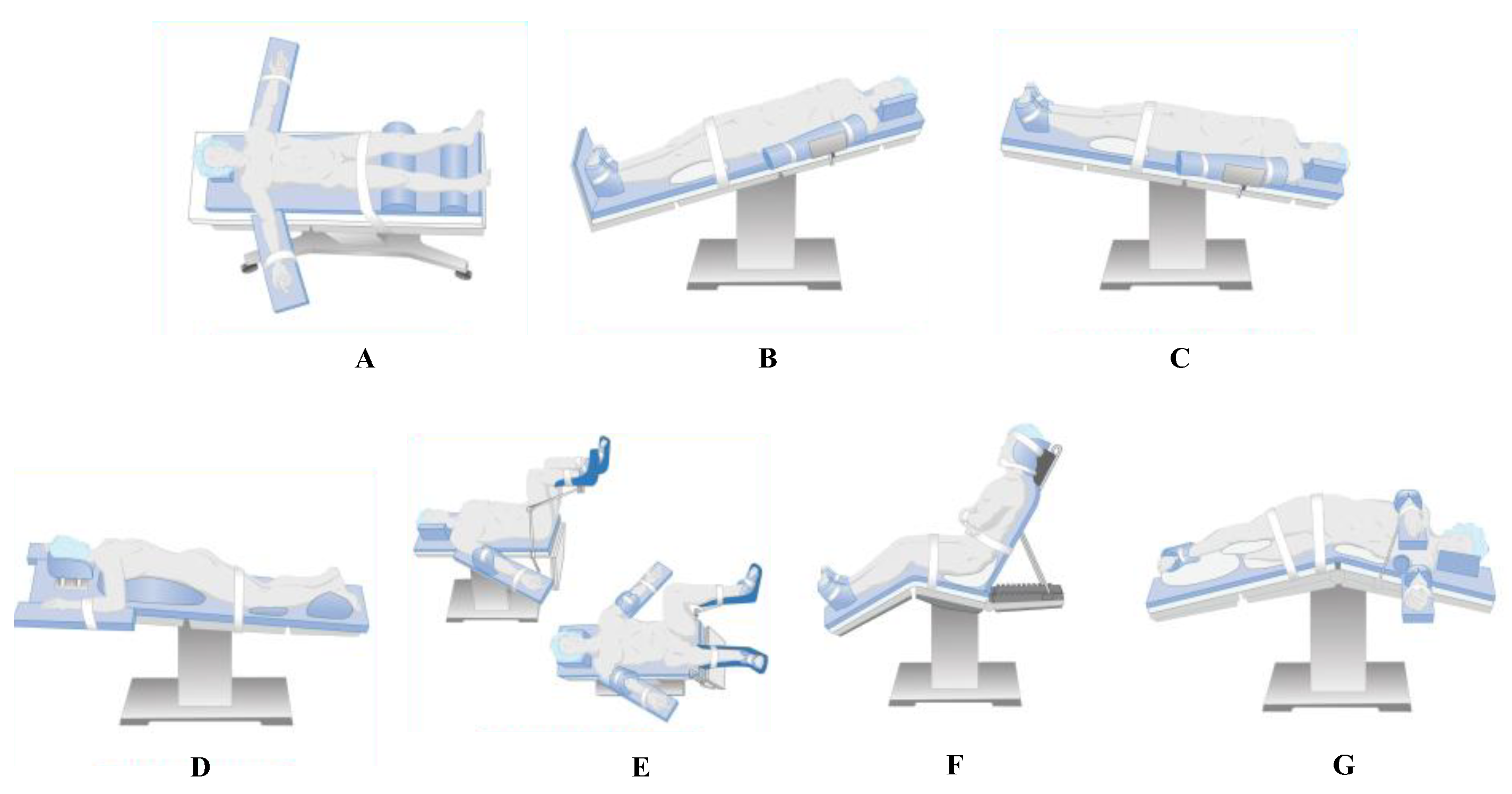

3.2. Intraoperative Phase

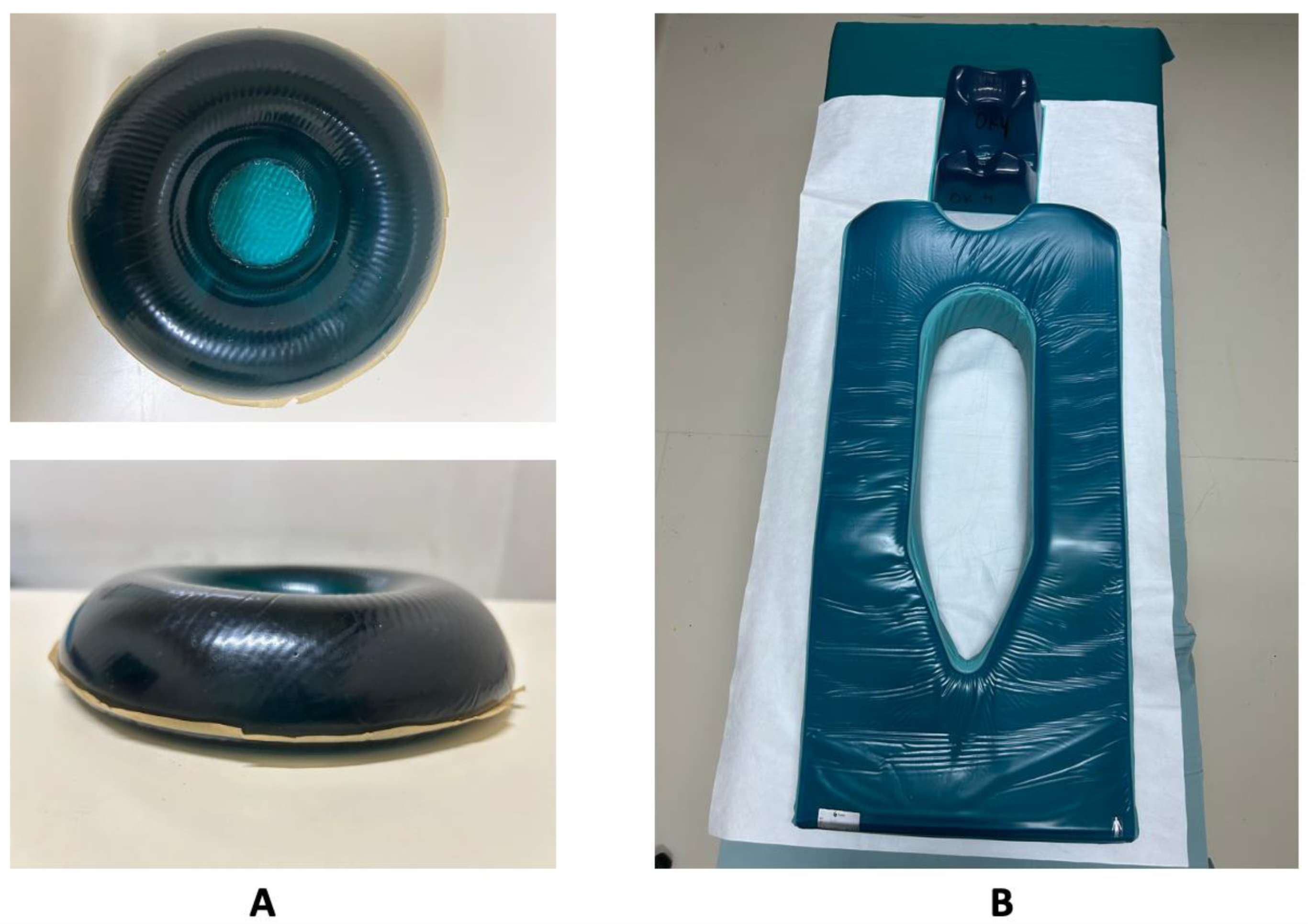

3.2.1. Pressure-Redistribution

3.2.2. Microclimate Regulation

3.2.3. Perfusion

3.2.4. Clinical Workflow Integration (Optional)

3.3. Postoperative Phase

3.3.1. Systematic Skin Assessment and Surveillance

3.3.2. Repositioning and Mobilization

3.3.3. Support Surfaces and Moisture

3.3.4. Interdisciplinary Communication and Care

4. Implication to Practice

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PI | Pressure Injury |

| PIs | Pressure Injuries |

| AORN | Association of periOperative Registered Nurses |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| IAPI | Intraoperatively Acquired Pressure Injury |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| PACU | Post-Anesthesia Care Unit |

| NPIAP | National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel |

| PRAMS | Perioperative Risk Assessment Measure for Skin |

References

- Suh, D.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, B.; Lee, S. An Exploratory Study of Risk Factors for Pressure Injury in Patients Undergoing Spine Surgery. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2020, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savcı, A.; Karacabay, K.; Aydın, E. Incidence and Risk Factors of Operating Room–Acquired Pressure Injury: A Cross-Sectional Study. Wound Manag Prev 2024, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guler, B.; Gurkan, A. Effect of Different Positioning before, during and after Surgery on Pressure Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Int J Clin Trials 2024, 11, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Cui, D.; Shan, L.; Li, H.; Feng, X.; Zeng, H.; Li, L. The Prediction Model for Intraoperatively Acquired Pressure Injuries in Orthopedics Based on the New Risk Factors: A Real-World Prospective Observational, Cross-Sectional Study. Front Physiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Chen, T.; Zheng, W.; Chen, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhuo, Q. Incidence and Risk Factors of Intraoperative Acquired Pressure Injury in Open Heart Surgical Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. European Journal of Medical Research 2025, 30 30, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xiong, X.; Lan, W. Prevention of Pressure Injuries in the Operating Room: Challenges and Strategies. J Adv Nurs 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, E. de O.; Kamada, I. MEDICAL-DEVICE-RELATED PRESSURE INJURY ON ADULTS: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Miao, M.; Shi, G.; Zhang, P.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Jiang, L. Operative Positioning and Intraoperative-Acquired Pressure Injury: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Adv Skin Wound Care 2024, 37, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lee, H.; Ha, T.; Na, S. Perioperative Factors Associated with Pressure Ulcer Development after Major Surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol 2017, 71, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruce, L. Prevention of Perioperative Pressure Injury. AORN J 2023, 117, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, W. V.; Delarmente, B.A. The National Cost of Hospital-acquired Pressure Injuries in the United States. Int Wound J 2019, 16, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantafyllou, C.; Chorianopoulou, E.; Kourkouni, E.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Kourlaba, G. Prevalence, Incidence, Length of Stay and Cost of Healthcare-Acquired Pressure Ulcers in Pediatric Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2021, 115, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afridi, A.; Rathore, F.A. Are Risk Assessment Tools Effective for the Prevention of Pressure Ulcers Formation?: A Cochrane Review Summary with Commentary. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020, 99, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussou, E.; Fasoi, G.; Stavropoulou, A.; Kelesi, M.; Vasilopoulos, G.; Gerogianni, G.; Alikari, V. Quality of Life of Patients with Pressure Ulcers: A Systematic Review. Med Pharm Rep 2023, 96, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, F.; Şenol Çelik, S. Knowledge and Practices of Operating Room Nurses in the Prevention of Pressure Injuries. J Tissue Viability 2022, 31, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, E.D.; Uslu, Y. Pressure Injuries in the Operating Room: Who Are at Risk? https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2023.32.Sup7a.cxxviii 2023, 32, CXXVIII–CXXXVI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AKAN, C.; SAYIN, Y.Y.; AKAN, C.; SAYIN, Y.Y. Prevalence of Pressure Injuries and Risk Factors in Long-Term Surgical Procedures. Bezmialem Science 2021, 9, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlkhan, E.; Sucu Dag, G. The Incidence and Risk Factors of Pressure Injuries in Surgical Patients. J Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, B.; Karayurt, Ö.; Ogce, F. The Effect of Selected Risk Factors on Perioperative Pressure Injury Development. AORN J 2019, 110, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AORN Updates to Guideline for Pressure Injury | Periop Today | AORN. Available online: https://www.aorn.org/article/key-takeaways-pressure-injury-guideline-updates-2023 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Picoito, R.; Manuel, T.; Vieira, S.; Azevedo, R.; Nunes, E.; Alves, P. Recommendations and Best Practices for the Risk Assessment of Pressure Injuries in Adults Admitted to Intensive Care Units: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports 2025, Vol. 15 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AHRQ Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/resource/pressureulcer/tool/index.html?utm (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Song, H.; Qu, T.; Zheng, C.; Wei, N. Clinical Application of Checklist Management in the Prevention of Pressure Injuries among Oncologic Surgical Patients. Supportive Care in Cancer 2025, 33, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AORN GUIDELINES FOR PERIOPERATIVE PRACTICE. 2023.

- Munro, C.A. The Development of a Pressure Ulcer Risk-Assessment Scale for Perioperative Patients. AORN J 2010, 92, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, H.; Scott, D.; Makic, M.B.F. Using Evidence to Prevent Risk Associated With Perioperative Pressure Injuries. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing 2022, 37, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Qian, Q.; Wu, B. Comparison of Four Risk Assessment Scales in Predicting the Risk of Intraoperative Acquired Pressure Injury in Adult Surgical Patients: A Prospective Study. Journal of International Medical Research 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, N.; Demuth, P.J.; Braden, B.J. A Clinical Trial of the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Nursing Clinics of North America 1987, 22, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, M.; Loretta; Foon, Y.; Lv, | Lin; Han, L. Predictive Validity of the Braden Scale for Pressure Injury Risk Assessment in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesler, E. National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Quick Reference Guide; The International Guideline: Fourth Edition, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.; Zhou, T.; Xu, X.; Wang, L. Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale in Adult Patients Undergoing General Anesthesia in the Operating Room. J Healthc Eng 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.S.; Acunã, A.A. Implantação Da Escala Munro de Avaliação de Risco de Lesão Por Pressão No Perioperatório. Revista SOBECC 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AORN Updates to Guideline for Pressure Injury | Periop Today | AORN. Available online: https://www.aorn.org/article/key-takeaways-pressure-injury-guideline-updates-2023 (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Meehan, A.J.; Beinlich, N.R.; Hammonds, T.L. A Nurse-Initiated Perioperative Pressure Injury Risk Assessment and Prevention Protocol. AORN J 2016, 104, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, A.J.; Beinlich, N.R.; Bena, J.F.; Mangira, C. Revalidation of a Perioperative Risk Assessment Measure for Skin. Nurs Res 2019, 68, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, R. Enhancing Perioperative Care: Implementing the Scott Triggers Tool to Prevent Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries in Vascular Surgery Patients - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40013702/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Cai, F.; Zhu, C.; Lin, S.; Huang, P.; Zhang, L. Nutritional Status as a Predictor of the Incidence of Pressure Injury in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, N.; Posthauer, M.E.; Cereda, E.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; Haesler, E. The Role of Nutrition for Pressure Injury Prevention and Healing: The 2019 International Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations. Adv Skin Wound Care 2020, 33, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AORN Pressure Injury Prevention: AORN Guideline Takeaways for Periop Nurses | AORN Periop Today | AORN. Available online: https://www-aorn-org.translate.goog/article/pressure-injury-prevention--aorn-guideline-takeaways-for-periop-nurses?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=id&_x_tr_hl=id&_x_tr_pto=sge (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Beatriz Cunha Prado, C.; Alves Silva Machado, E.; Dal Sasso Mendes, K.; Cristina de Campos Pereira Silveira, R.; Maria Galvão, C. Support Surfaces for Intraoperative Pressure Injury Prevention: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis*. Rev Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2021, 29, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.Y.; Shin, S.H. Effect of Soft Silicone Foam Dressings on Intraoperatively Acquired Pressure Injuries: A Randomized Study in Patients Undergoing Spinal Surgery. Wound Manag Prev 2020, 66, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.; Walker, R.; Gillespie, B.M. Pressure Injury Prevention in the Perioperative Setting: An Integrative Review. Journal of Perioperative Nursing 2018, 31, 27-35–27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. Lecture as Part of a Series by Parafricta Microclimate and Pressure Ulcer Development; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kottner, J.; Black, J.; Call, E.; Gefen, A.; Santamaria, N. Microclimate: A Critical Review in the Context of Pressure Ulcer Prevention. Clinical Biomechanics 2018, 59, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M.; Nakagami, G.; Iizaka, S.; Yoshida, M.; Uehata, Y.; Kohno, M.; Kasuya, Y.; Mae, T.; Yamasaki, T.; Sanada, H. Microclimate Is an Independent Risk Factor for the Development of Intraoperatively Acquired Pressure Ulcers in the Park-Bench Position: A Prospective Observational Study. Wound Repair Regen 2015, 23, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, F.; Liao, B.; Yang, X.; Zhuang, C.; Huang, J. Prevention of Intraoperative Acquired Pressure Injury in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer and Its Effect on Skin Microclimate: A Single-Blind Randomised Controlled Trial. Int Wound J 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderden, J.; Rondinelli, J.; Pepper, G.; Cummins, M.; Whitney, J.A. Risk Factors for Pressure Injuries among Critical Care Patients: A Systematic Review. Int J Nurs Stud 2017, 71, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dai, Y.; Cai, W.; Sun, M.; Sun, J. Monitoring of Perioperative Tissue Perfusion and Impact on Patient Outcomes. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 2025 20:1 2025, 20, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dai, Y.; Cai, W.; Sun, M.; Sun, J. Monitoring of Perioperative Tissue Perfusion and Impact on Patient Outcomes. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 2025 20:1 2025, 20, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadede, Ö.; Toğluk Yiğitoğlu, E.; Şeremet, H.; Özyilmaz Daştan, Ç. Incidence and Risk Factors for Perioperative Pressure Injuries: Prospective Descriptive Study. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing 2025, 40, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AORN 5 Essential Steps to Prevent Pressure Injuries in Surgery | AORN. Available online: https://www.aorn.org/article/5-essential-steps-to-prevent-pressure-injuries-in-surgery (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Speth, J. Guidelines in Practice: Prevention of Perioperative Pressure Injury. In AORN J; PAGE:STRING:ARTICLE/CHAPTER, 2023; Volume 118, pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisley, M.; Sørensen, J.A.; Sollie, M. Postoperative Pressure Injuries in Adults Having Surgery under General Anaesthesia: Systematic Review of Perioperative Risk Factors. BJS 2020, 107, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlkhan, E.; Sucu Dag, G. The Incidence and Risk Factors of Pressure Injuries in Surgical Patients. J Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, H.; Scott, D.; Makic, M.B.F. Using Evidence to Prevent Risk Associated With Perioperative Pressure Injuries. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing 2022, 37, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Wang, F.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, R.; Tung, T.H. The Accuracy of the Risk Assessment Scale for Pressure Ulcers in Adult Surgical Patients: A Network Meta-Analysis. BMC Surg 2025, 25, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NPIAP Support Surfaces — International Guideline. Available online: https://internationalguideline.com/surfaces (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Avsar, P.; Moore, Z. Repositioning for Preventing Pressure Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Wound Care 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenbruch, C. Microclimate Management So Much More than Just Airflow…. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haesler, E. WHAM Evidence Summary: Low Friction Fabric for Preventing Pressure Injuries. Wound Practice and Research 2020, 28, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, U.R. Impact of Multifaceted Interventions on Pressure Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review. BMC Nursing 2024, 24 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietl, J.E.; Derksen, C.; Keller, F.M.; Lippke, S. Interdisciplinary and Interprofessional Communication Intervention: How Psychological Safety Fosters Communication and Increases Patient Safety. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1164288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressure Injury Prevention: AORN Guideline Takeaways for Periop Nurses | AORN Periop Today | AORN. Available online: https://www.aorn.org/article/pressure-injury-prevention--aorn-guideline-takeaways-for-periop-nurses (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Zhu, W.; Pei, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q. Effects of Different Nursing Interventions for Intraoperative Acquired Pressure Injuries: A Network Meta-Analysis. BMC Nurs 2025, 24, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, L. Intraoperative Pressure Injury Prevention. Nursing Clinics of North America 2025, 60, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Tang, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z. A Predictive Model of Pressure Injury in Children Undergoing Living Donor Liver Transplantation Based on Machine Learning Algorithm. J Adv Nurs 2024, 81, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, W.D.; Limcangco, R.; Owens, P.L.; Steiner, C.A. Marginal Hospital Cost of Surgery-Related Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers. Med Care 2016, 54, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savcı, A.; Karacabay, K.; Aydın, E. Incidence and Risk Factors of Operating Room-Acquired Pressure Injury: A Cross-Sectional Study. Wound Manag Prev 2024, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Rong, R.; Guo, L.; Pei, Y.; Lu, X. Constructing Nursing Quality Indicators for Intraoperative Acquired Pressure Injury in Cancer Patients Based on Guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, X. Nomogram for Intraoperatively Acquired Pressure Injuries in Children Undergoing Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Retrospective Study. BMC Pediatr 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates-Jensen, B.M.; Crocker, J.; Nguyen, V.; Robertson, L.; Nourmand, D.; Chirila, E.; Laayouni, M.; Offendel, O.; Peng, K.; Romero, S.A.; et al. Decreasing Intraoperative Skin Damage in Prone-Position Surgeries. Adv Skin Wound Care 2024, 37, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, A.; Brienza, D.M.; Cuddigan, J.; Haesler, E.; Kottner, J. Our Contemporary Understanding of the Aetiology of Pressure Ulcers/Pressure Injuries. Int Wound J 2021, 19, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, C.R.; Droste, L.R.; Bonham, P.; Crestodina, L.; Johnson, J.J.; Kelechi, T.; Varnado, M.F.; Palmer, R.; Carroll, B. WOCN 2016 Guideline for Prevention and Management of Pressure Injuries (Ulcers): An Executive Summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017, 44, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Braden Scale | Munro Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Setting | General ward, long-term care | Operating theater, perioperative care |

| Assessment Timing | Static; at admission and daily reassessment | Dynamic; pre-, intra-, and postoperative reassessment |

| Focus | Functional and sensory impairment | Physiological and procedural risk factors |

| Variables | Six patient-based domains | Multi-phase domains (mobility, anesthesia, perfusion, positioning, blood loss) |

| Risk Scoring | 6–23 (lower = higher risk) | 0–100 (higher = higher risk, cumulative) |

| Suitability | General medical/surgical wards | Operating room and PACU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).