1. Introduction

1.1. The Central European Wolf Populations’ Ecology and Protection

The grey wolf (

Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758) historically had one of the broadest distributions of any terrestrial mammal across the Holarctic, spanning much of Europe as well as large portions of Asia and North America. [

1,

2]. Intense persecution extirpated wolves from much of Western Europe [

3,

4], but remnant populations later expanded under stricter protection (EU Habitats Directive; Bern Convention) [

5,

6]; the species is currently listed as Least Concern by IUCN [

7]. The Central European wolf population has been pivotal for Denmark’s recolonization [

4,

8,

9]. After 200 years of absence, wolves were recorded again in Denmark in October 2012, followed by immigrants from Germany [

9,

10]. Since 2017, a national program led by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency with the Natural History Museum Aarhus and Aarhus University has followed SCALP standards, integrating DNA, photo documentation, and validated public reports [

10,

11]. To date, 35 individuals have been genetically identified, mainly in remote heathland/forest areas with low human activity [

10,

12]. As DNA-based individual monitoring becomes increasingly costly, Denmark has since 2025 estimated population size by converting packs to individuals using a spring factor of 7 (IUCN-consistent range 6–8) [

10], highlighting the need for complementary non-invasive tools such as acoustic monitoring (Supplementary materials S1).

Bioacoustics monitoring, in particular passive acoustic monitoring (PAM), uses autonomous sound recorders to survey wildlife and their environments [

13,

14]. PAM has been successfully applied in terrestrial systems to monitor elephants, gibbons, red deer, birds and elusive carnivores such as wolves [

15,

16]. For wolves, acoustic monitoring includes not only passive recording but also simulated howls performed by observers, a widely used technique to elicit vocal responses and locate packs [

37,

39]. Recorders deployed unattended for days to weeks on predefined schedules can, under suitable conditions, monitor an area with a radius of approximately 3 km [

17], including remote or privately owned terrain that is otherwise difficult to access [

18,

19]. For wolves, PAM focuses on howls and is highly non-invasive, allowing detection of presence and packs over large areas and potentially providing information on individual animals. Bioacoustic data are analysed as spectrograms, and wolf howls, which are tonal and harmonic, can be characterised by their fundamental frequency (F0); variation in F0 among individuals enables individual discrimination and identification [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

1.2. Wolf Communication by Howling

Wolves use several channels of communication, but howling is their most conspicuous long-distance vocalisation [

22]. Adult howls are low, harmonically structured calls typically spanning a fundamental frequency of approximately 150–780 Hz [

20] and are produced solo or in choruses for territorial defence, maintaining contact among pack members and social bonding [

22,

23]. Active vocalizations of wolves allow us to study the significance of interspecies interactions [Palacios et al 2007], because howls travel over long distances, especially at night, they can convey information on location, identity, age and sex, and howling rates increase during the pre-breeding and breeding seasons [

22]. In human-dominated landscapes, wolves and prey often shift activity to avoid people; this “super-predator” effect compresses vocal activity into nocturnal windows, which is crucial for PAM deployment and interpretation [

24].

Vocal communication begins early in life: pups initially whine, moan and scream, and after two to three weeks, when they emerge above ground, they start howling daily [

20,

22]. At this stage, the fundamental frequency is high (around 1,000 Hz) and then declines over the following months; by six to seven months, pup howls resemble adult howls with fundamental frequencies around 350 Hz [

18]. In autumn, pups increasingly travel with the pack and contribute more frequently to howling events [

25]. These ontogenetic changes in howl production suggest that bioacoustic monitoring may help discriminate pups from adults and, consequently, provide a non-invasive indicator of local breeding activity [

22,

25].

Scope of the Study

Acoustic monitoring is a valuable complement to other methods. It enables systematic, long-range surveillance and requires less field effort than visual sightings, track-and-sign surveys, or extensive camera-trap deployment. In addition, it can reveal breeding activity and may allow identification of individuals. Although bioacoustics monitoring is now widely used, further refinement is needed to optimize its effectiveness for wolves.

In Denmark, interpretation of acoustic activity should account for (i) the standardized SCALP framework by identifying individuals in a pack and reproduction has been successful, (ii) the national shift to reporting reproductive units and estimating total abundance with a spring conversion factor (6–8; presently 7), and (iii) acoustic monitoring could be used as early warning when wolves have newly established in areas with livestock.

We hypothesize that autonomous passive acoustic monitoring in confirmed Danish wolf territories can reliably detect howling and that howl structure contains repeatable acoustic signatures that enable inference of (i) individual identity, (ii) age class (pup vs. adult), and (iii) sex among adults; furthermore, we hypothesize that standardized auditory playbacks can increase the probability of eliciting howls relative to baseline conditions. This study advances the use of autonomous acoustic recorders for monitoring free-ranging wolves in Denmark by:

- (1)

Quantifying howling activity from sunset to sunrise across autumn and winter to inform optimal deployment and sampling schedules.

- (2)

Testing whether fundamental-frequency features enable discrimination and classification of individual free-ranging wolves.

- (3)

Assessing whether pup howls can be distinguished from adult howls to provide a non-invasive indicator of breeding activity.

- (4)

Evaluating whether adult howls can be differentiated by sex (female vs. male) based on acoustic structure.

- (5)

Testing whether howling can be experimentally elicited under controlled playback conditions.

In breeding territories, adult howls (restricted to the adult-frequency range) are expected to show a bimodal distribution in maximum fundamental frequency (Max F0), consistent with sex-related differences in vocal output (with females exhibiting higher Max F0 than males). We further hypothesize that the higher-frequency cluster will account for a greater proportion of adult howls in late summer–autumn, when pups accompany the pack, reflecting sex-specific contributions to pup care, pack coordination, and territorial signaling.

We will evaluate these aims through bioacoustics monitoring within confirmed wolf territories across Denmark and analyze the recordings for statistically significant differences linked to specific behavioral tendencies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collecting Howls from Wild and Captive Wolves

Data comprised howls from captive wolves at a Danish zoological park and from free-ranging wolves in Denmark. Recordings were obtained through bioacoustics monitoring using a Song Meter SM4 Bioacoustics Recorder (Wildlife Acoustics Inc., Maynard, Massachusetts, United States). Audio files were saved in WAV format on secure digital cards with 128 gigabytes of storage. Wild-wolf recordings were collected in areas with known territories or recent observations. Initial information on wolf presence was compiled from wolf-tracking platforms, daily press reports, and social media. The Ulveatlas.dk website provided specific, up-to-date sighting records. Local personnel within the study areas contributed site knowledge, including guidance on optimal recorder placement.

2.1.1. Location Selection

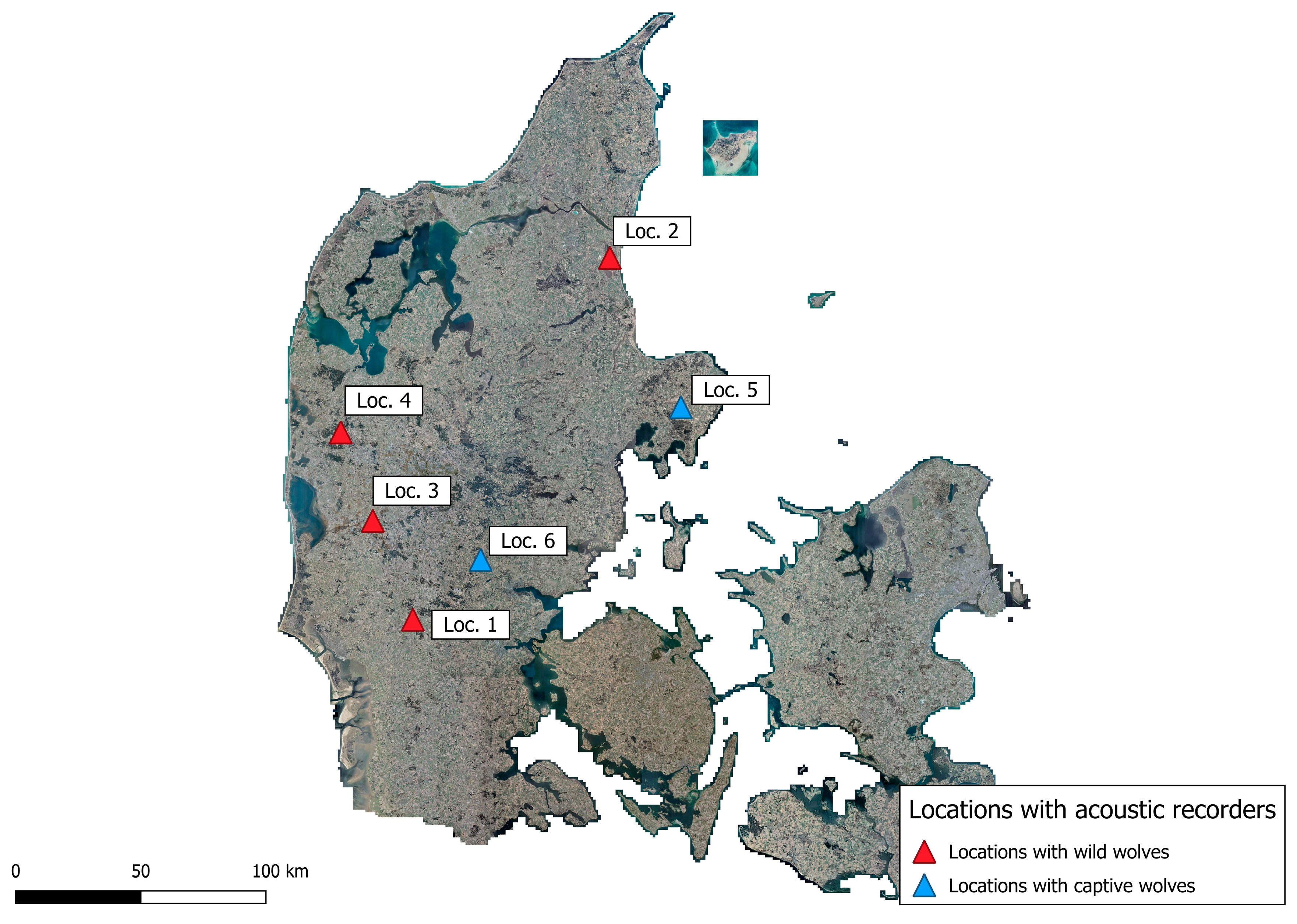

Four locations were chosen for collecting howls from wild wolves and two locations were chosen for collecting howls from wolves in captivity (

Figure 2.1).

Location 1 (55°35'36"N 8°55'13"E). Wolves were documented at this site [

10]. Acoustic recording was conducted from 26 August 2021 to 21 February 2022 (app.

Table A5.1).

Location 2 (56°52'54"N 10°12'13"E). A wolf was documented at this site [

10]. Recordings were collected during four periods: 10–31 July 2021, 25 August–13 September 2021, 14–28 December 2021, and 18 January–1 February 2022.

Location 3 (55°56'51"N 8°39'47"E). Wolves were documented at this site [

10]. Acoustic recording started in October 2021; audio data from January–February 2022 was lost due to equipment issues [

10] (app.

Figure A5.5).

Location 4 (56°14'08"N 8°29'47"E). Wolves have been present at this site [

10,

12,

26]. Acoustic recording started on 2 August 2021 [

10,

12,

26].

Location 5 (56°20'39"N 10°39'13"E)

. Wildlife Park/Zoo with three captive adult Eurasian wolves (

Canis lupus lupus), all siblings; two males and one female, all were sterilised. Recording began on 28 August 2021 (app.

Table A5.2).

Figure 2.1.

Locations in Denmark where bioacoustics recorders were deployed to collect wolf howls.

Figure 2.1.

Locations in Denmark where bioacoustics recorders were deployed to collect wolf howls.

Location 6 (55°48'27"N 9°21'07"E). Wildlife Park/Zoo with eleven captive male Mackenzie-Valley wolves (Canis lupus occidentalis) native to North America. A litter of five pups was born in 2021; pup sex was not recorded for this study, and pup vocalizations were present across the three recording periods. Recordings at this location were collected during three periods: 24 Oct–8 Nov 2021 (RecP1), 16–30 Nov 2021 (RecP2), and 7–30 Jan 2022 (RecP3), during which pup howls were present.

In the following

Table 2.1, you can view the different locations and recordings periods.

Table 2.1.

Overview of the six recording locations (Location 1–6), including venue type and wolf status (wild vs. captive), and the corresponding recording periods (deployment dates) used in this study.

Table 2.1.

Overview of the six recording locations (Location 1–6), including venue type and wolf status (wild vs. captive), and the corresponding recording periods (deployment dates) used in this study.

| Location |

Venue (Site Type) |

Wolf Status |

Recording Periods/Dates |

| Loc 1 |

fenced nature area |

wild |

20 Aug–3 Sep 2021; 28 Sep–13 Oct 2021; 13–26 Oct 2021; 26 Oct–8 Nov 2021; 22 Nov–5 Dec 2021; 21 Dec 2021–3 Jan 2022; 7–20 Feb 2022 |

| Loc 2 |

fenced nature area |

wild |

10–31 Jul 2021; 25 Aug–13 Sep 2021; 14–28 Dec 2021; 18 Jan–1 Feb 2022 |

| Loc 3 |

military training area |

wild |

Recording began Oct 2021 |

| Loc 4 |

forest–heath

mosaic |

wild |

Recording started 2 Aug 2021 (two units; one mobile, one stationary) |

| Loc 5 |

zoo |

captive |

28 Oct–11 Nov 2021; 16–29 Nov 2021; 17–31 Jan 2022 |

| Loc 6 |

zoo |

captive |

24 Oct–8 Nov 2021; 16–30 Nov 2021; 7–30 Jan 2022 (pup howls present across periods) |

2.1.2. Placement and Settings for the Acoustic Recorders

Operating time of autonomous recorders depends on environmental conditions, primarily temperature and moisture exposure. Low ambient temperatures reduce battery voltage and effective capacity, shortening operating time relative to room-temperature specifications, whereas persistent rain, high humidity, and freeze–thaw conditions can promote condensation or water ingress and may prematurely end deployments.

Each deployment lasted approximately three weeks, after which batteries and SD cards were replaced. Recorder settings were configured to capture the fundamental frequency ranges of both adult and pup howls. The sampling rate was 44.1 kHz with 16-bit amplitude resolution. A 220 Hz high-pass filter was applied to attenuate wind and anthropogenic noise.

Recorder sites were selected in collaboration with local personnel, who provided up-to-date information on wolf activity and frequently used areas to guide optimal placement. Units were strapped to trees at approximately 1.5 m height in semi-open forest, where surrounding vegetation provided wind shelter without obstructing sound transmission to the microphones. Recording schedules targeted peak vocal activity: because spontaneous wolf howling is concentrated from sunset through the night (often peaking in the evening hours) and chorus howls generally peak between sunset and sunrise, the schedule initially ran 20:00–07:00 and was later adjusted to 17:00–08:00 with the shift from summer to wintertime [

27,

28]. At Location 5, the recorder was positioned adjacent to the enclosure to allow battery and SD-card changes without staff assistance.

2.1.3. Spectrograms

Kaleidoscope Pro 5.4.3 (Wildlife Acoustics Inc., Maynard, MA, USA)—a bioacoustic analysis software package that provides spectrogram visualization and tools for automated detection and acoustic clustering of candidate signals in large audio datasets—was used to detect wolf howls [

29]. The detector was trained on annotated recordings with signal parameters set to 100–2000 Hz to encompass adult howls and the higher-frequency calls of pups (up to ~1100 Hz) [

20]. Detection length was constrained to 0.5–20 s, and the maximum inter-syllable gap (used to delimit signals) was 0.35 s [

16]. Detected events were then grouped using Kaleidoscope’s cluster analysis, which sorts files by acoustic similarity [

29]. For clustering, the maximum distance from the cluster center to include in the output (similarity threshold relative to the training set) was set to 1.0 [

16]. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) window was 21.33 ms, and the maximum number of states for the Hidden Markov Model was 12, following manufacturer guidance that higher settings can increase discrimination among clusters [

16,

29]. To control cluster formation, the maximum distance to the cluster center when building clusters was 0.5, and the maximum number of output clusters was capped at 500. Only the FFT parameter was set to its maximum; all other clustering parameters were left at default values. After automated processing, we conducted an initial review of clusters to locate groups of similar detections, followed by manual verification and labelling because some wolf howls were mixed with other species’ calls (e.g., red deer roars). Spectrograms and audio were inspected to assign call types: solo howls were labelled “wolf howl,” two overlapping howls “wolf duet,” and three or more overlapping howls “wolf chorus” [

30]. Finally, the dataset was rescanned to further train the software for wolf-howl detection.

2.2. Analysis of Wolf Howls

Duets and choruses were generally excluded because overlapping vocalizations obscure individual contours; they were retained only when individual howls could be reliably isolated and when assessing temporal howling activity at Location 1, Location 5 and Location 6. Because our analyses rely on extracting the fundamental-frequency contour (and maximum fundamental frequency) from spectrograms, we applied an additional quality-control step during acoustic measurement. Howls were excluded from fundamental-frequency–based analyses when the fundamental-frequency band was not clearly distinguishable on the spectrogram (for example, very hoarse low-frequency howls with diffuse harmonics), or when pitch extraction could not be performed reliably. This criterion was applied to avoid biased or spurious maximum fundamental-frequency values in the mixture analyses used for pup detection and sex-related clustering.

2.2.1. Howling Activity of Wild and Captive Wolves

All wolf howls from Location 1 and Location 5 were aggregated by hour within the recording schedule. To account for unequal recording effort across deployments, counts were normalized to howls per hour. This adjustment was particularly important for Location 1, which had more recording periods.

2.2.4. Individual Identification of Wolves

To identify individuals, isolated clips were assigned to presumed adult howls. Putative pup howls were excluded because, as shown in previous studies, pup vocalizations change substantially until adulthood, precluding reliable individual assignment [

20]. All howls from Location 1, Location 5 and Location 6 were attributed based on structural features in both the audio and spectrogram, which provided the clearest individual differences.

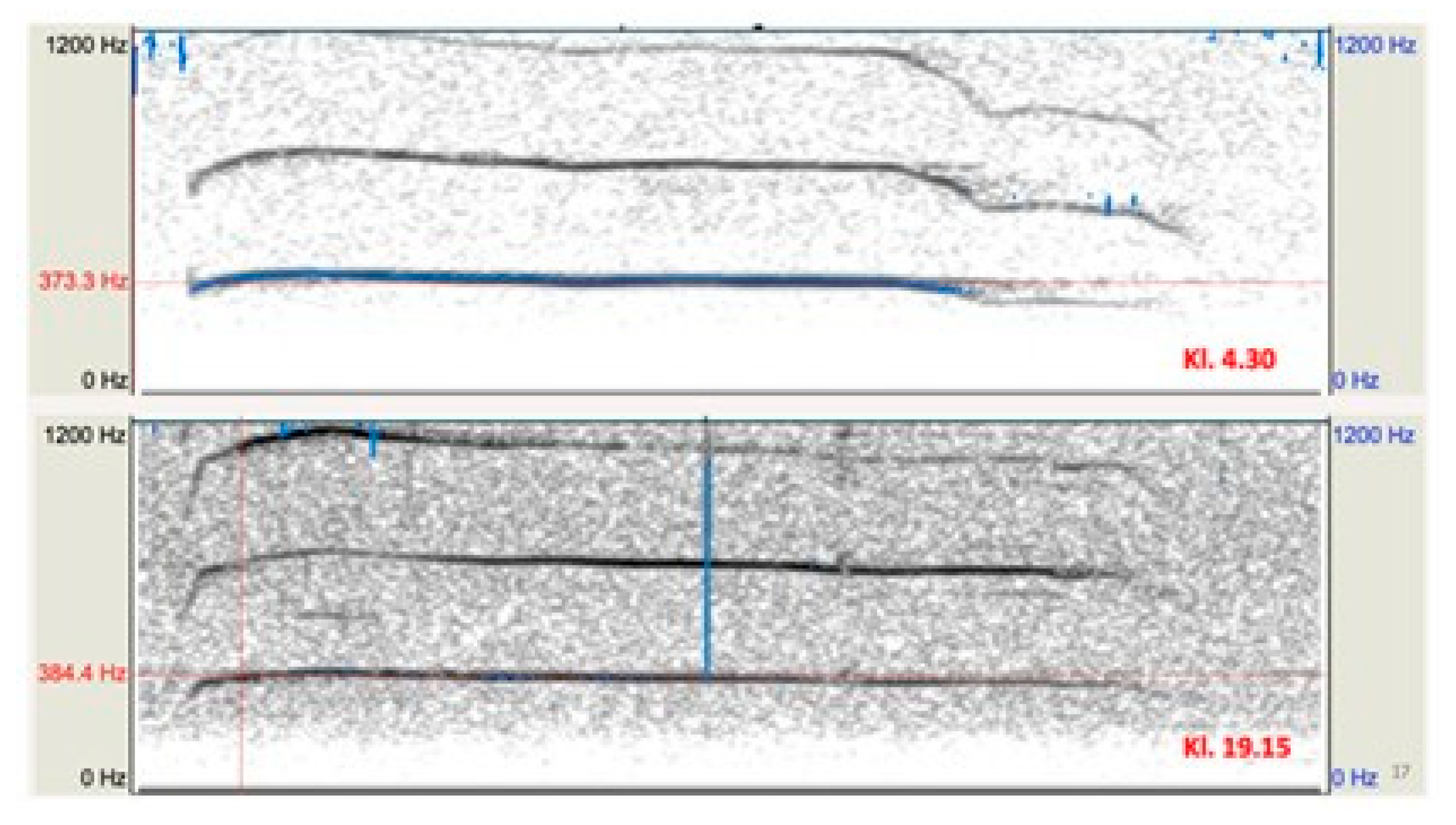

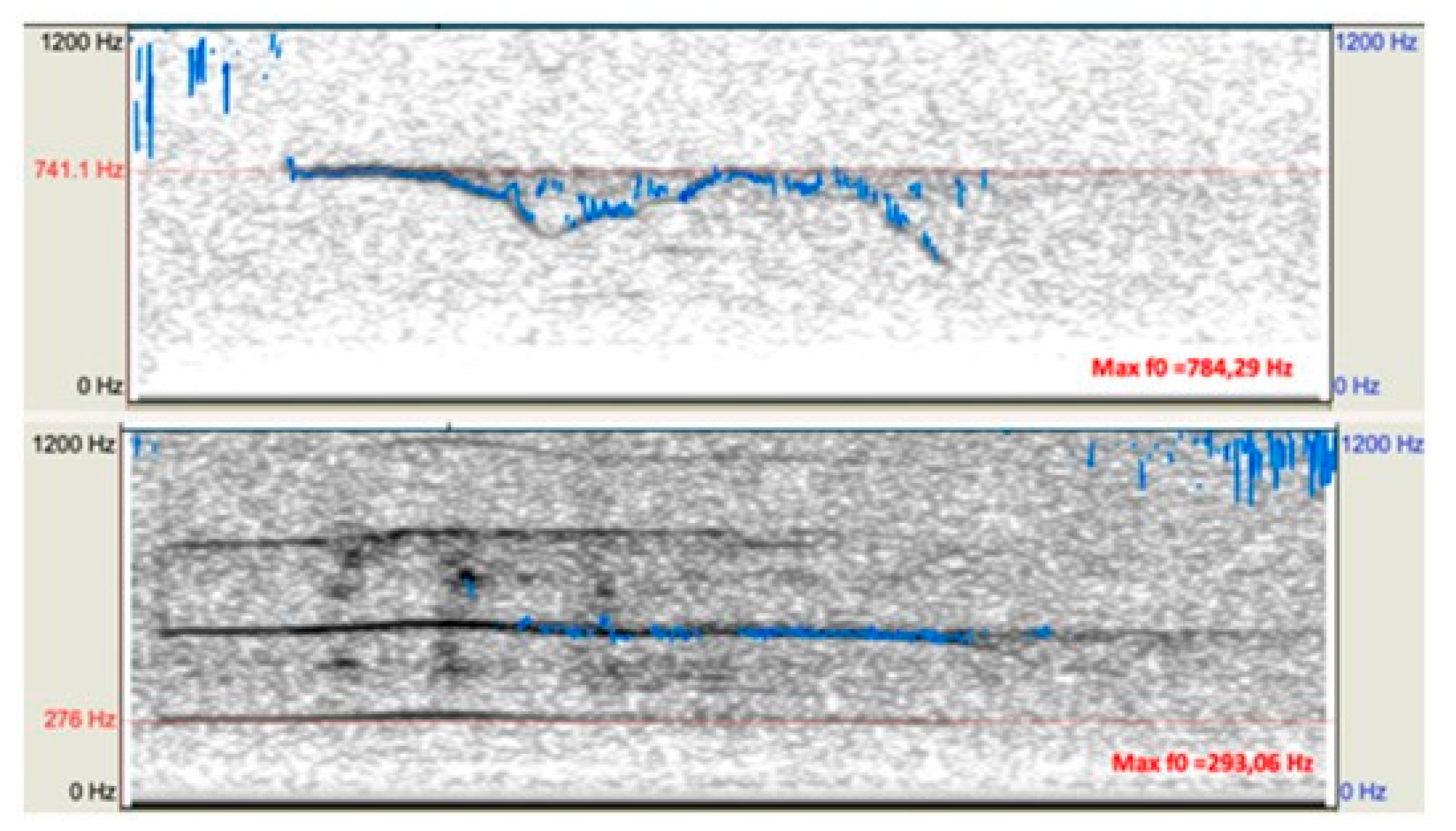

Only howls from Location 1 were used to estimate the number of adult wolves, as these deployments yielded the largest sample of wild vocalizations. The analysis comprised 40 howls attributed to two presumed adults. Isolated clips were assigned to adults based on distinctive structural features, the primary criterion, and 20 recordings were allocated to everyone. Howls with high maximum fundamental frequencies were excluded. Variables for individual identification were extracted in Praat via pitch analysis (

Figure 2.2,

Table 2.1).

Figure 2.2.

Spectrogram of two howls presumed to be from an adult wolf. The fundamental frequency and recording times are indicated. Howls were recorded at Location 1 and processed in Praat.

Figure 2.2.

Spectrogram of two howls presumed to be from an adult wolf. The fundamental frequency and recording times are indicated. Howls were recorded at Location 1 and processed in Praat.

Table 2.1.

Acoustic variables used to investigate individual identification in wolves and to assess differences between adult and pup howls [

16,

19].

Table 2.1.

Acoustic variables used to investigate individual identification in wolves and to assess differences between adult and pup howls [

16,

19].

| Variable |

Definition |

| Mean F0 |

Mean distribution of the fundamental frequency (Hz) |

| Min F0 |

Minimum fundamental frequency (Hz) |

| PosMin F0 |

Position of minimum frequency (time of min/duration) |

| Max F0 |

Maximum fundamental frequency (Hz) |

| PosMax F0 |

Position of maximum fundamental frequency (time of max/duration |

| Sd mean F0 |

Standard deviation of the mean fundamental frequency (Hz) |

| Cofv |

Coefficient of frequency variation (SD/Mean F0 x 100) |

| Slope |

Mean absolute slope of fundamental frequency F0 (Hz/s) |

| Range |

Range of fundamental frequency (Max F0 – Min F0) |

| Start F0 |

Start fundamental frequency (Hz) |

| End F0 |

End fundamental frequency (Hz) |

| Duration |

Duration of the howl (sec) |

To reduce multicollinearity, we calculated Pearson product-moment correlations among all variables for each howl and excluded those with r > 0.7 (Posmax F0, CovF, Start F0). We then evaluated classification of howls into two individuals using linear discriminant analysis in PAST, applied to the remaining variables: Mean F0, Min F0, Max F0, SD, Slope, Range, End F0, and Duration.

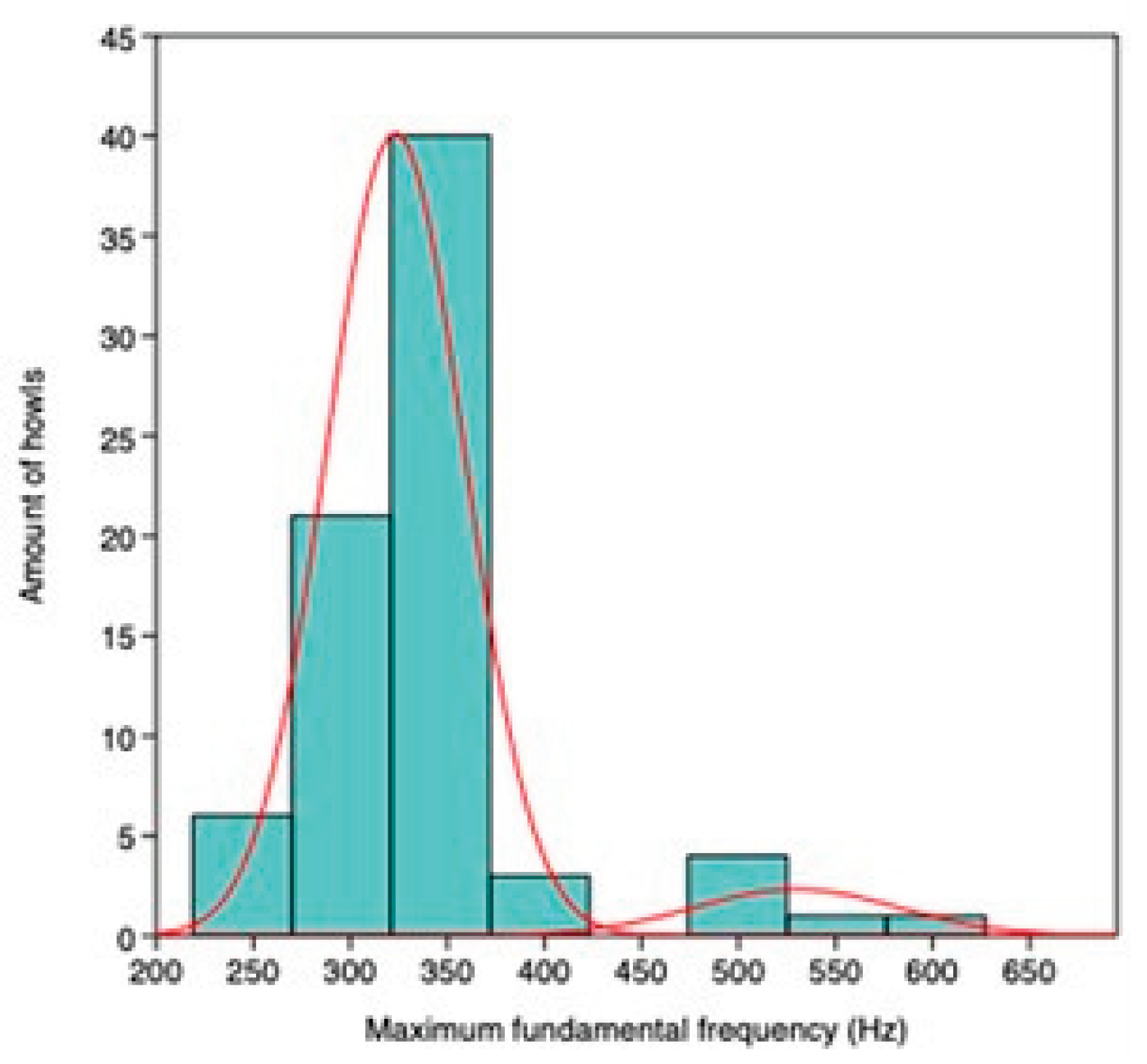

2.2.2. Identification of Howls from Pups

The speech analysis software Praat (Amsterdam, Netherlands) was used to analyse the acoustic structure of detected wolf howls from Location 1 and Location 6. At Location 1, at least four pups were born in April–May 2021 (all females), and recordings were collected from late August 2021 to February 2022; thus, pup howls were recorded during the pups’ first year. At Location 6, five pups were born in 2021, and recordings were made in October–November 2021 and January 2022; pup sex was not available and is therefore not reported. Maximum fundamental frequency (Max F0) was used to distinguish adults from pups in 148 howls from Location 1 (

Table 2.1) and 115 from Location 6 (

Table 2.1).

Table 2.1.

Number of howls per month used to distinguish pup from adult howls recorded at Location 1.

Table 2.1.

Number of howls per month used to distinguish pup from adult howls recorded at Location 1.

| |

Aug |

Sept |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

Feb |

| Number of howls used for identification |

11 |

4 |

32 |

44 |

54 |

3 |

Table 2.2.

Number of howls per month used to distinguish pup from adult howls recorded at Location 6.

Table 2.2.

Number of howls per month used to distinguish pup from adult howls recorded at Location 6.

| |

Oct |

Nov |

Jan |

| Number of howls used for identification |

37 |

37 |

41 |

Mixture analysis was conducted in PAST (In Supplementary materials S4). All howls were analyzed with a pitch ceiling of 1200 Hz. According to the literature, pup howls drop in frequency at 6–7 months of age [

22,

31]. Wolves generally whelp between mid-April and early May, with the majority of litters occurring in late April [

1,

3]. Consequently, pups were ~4 months old at the start of data collection in August. All recorded howls were included in the mixture analysis to separate higher– from lower–maximum fundamental frequencies, with the higher values presumed to be pup howls. This approach was used to track pup development, as howl frequency declines with age [

30]. Model fit was evaluated using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), and multivariate analyses—Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and MANOVA—assessed significance and group structure [

32].

2.2.3. Difference in Male and Female Wolf Howls

Howls with a maximum fundamental frequency (Max F0) below 550 Hz were used to distinguish males from females. Variables were extracted in Praat. A mixture analysis in PAST tested whether the Max F0 values from 64 howls could be partitioned into two groups [

33]. Model quality was evaluated with Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and MANOVA were used to assess significance and group structure [

32].

2.3. Eliciting Howls from Captive Wolves by Auditory Stimulation

Auditory stimulation to elicit howls from wolves has the potential to serve as a complementary method to Passive Acoustic Monitoring, as it can provoke howling from a distance and enable ‘on demand’ evaluation of wild populations.

To elicit howling, playback experiments were conducted at loc. 5 (30 March 2022) and loc. 6 (4 April 2022). At Location 5, three one-minute stimuli—an ambulance siren, church bells, and a howl from a female Arctic wolf (Canis lupus arctos)—were each broadcast 13 times in a fixed sequence with 10-minute intervals. This sequence was repeated three times, after which the stimulus that elicited the strongest response was played three consecutive times, and this was repeated twice. Start times of both playbacks and wolf responses were recorded.

Loc. 6 houses eleven captive male Mackenzie Valley wolves (

Canis lupus occidentalis), with five pups born the previous year. Two stimuli used at Location 5 (the Arctic female howl and church bells) were also broadcasted here, with the bell track modified to include five distinct bell tones to test tonal specificity, as these wolves are known to howl at local church bells and other stimuli of anthropogenic origin. The ambulance siren was replaced by a wolf duet recorded in 2020 in Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley (35 s) [

34]. Initially, the same clip was played four times at 10-minute intervals; subsequent broadcasts were single clips separated by 10 minutes. Finally, four additional stimuli were presented: a mixed-noise montage (bells, sirens, alarms, wolf howls), archival recordings of loc. 6 wolves in captivity from the previous year, field recordings from loc.1 (six howls near the recorder), and four bouts of human-produced howling at high volume. In total, 20 playbacks were conducted. After the first four trials, a 34-minute interruption occurred due to an event at the enclosure, after which the session resumed.

3. Results

3.1. Howling Activity of Wild and Captive Wolves

Most wild wolf howls were recorded at two of the four distribution sites (Location 1 and Location 3); at Location 2, the wolf’s presence during the study period was documented as a single yearling male (GW2368m), and in Location 1 the presence of the pair GW930f and GW1840m was confirmed. Location 1 produced the largest sample (486 observations in 1,549 hours of recording), while Location 3 produced six howls (app.

Table A5.1 and A5.2).

At Location 1, mean howling rate was low during RecP1–RecP3 (0.13, 0.05, 0.07 howls·h⁻¹), increased markedly in RecP4 (0.53), remained elevated in RecP5–RecP6 (0.29, 0.48), and declined in RecP7 (0.09). Within-night detections showed no consistent peak between sunset and sunrise, although relatively few howls occurred between 01:00 and 04:00 (

Table 3.1).

Table 3.1.

All recorded wolf howls (solo, duet, chorus) binned by hour for each recording period (RecP) in Location 1.

Table 3.1.

All recorded wolf howls (solo, duet, chorus) binned by hour for each recording period (RecP) in Location 1.

| |

17-18 |

18-19 |

19-20 |

20-21 |

21-22 |

22-23 |

23-00 |

00-01 |

01-02 |

02-03 |

03-04 |

04-05 |

05-06 |

06-07 |

07-08 |

| RecP1 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

| RecP2 |

- |

- |

1 |

13 |

16 |

0 |

23 |

45 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| RecP3 |

- |

- |

5 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| RecP4 |

0 |

2 |

62 |

40 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| RecP5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

23 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

16 |

1 |

1 |

| RecP6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

6 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

23 |

29 |

86 |

0 |

| RecP7 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Mean howling rates at Location 1 varied markedly among recording periods (

Table 3.X), with low rates in RecP1–RecP3, a peak in RecP4, sustained elevated rates in RecP5–RecP6, and a decline in RecP7.

Table 3.X.

Mean howling rate (howls h⁻¹) at Location 1 across recording periods (RecP1–RecP7), with corresponding deployment dates and total number of detected howls per period.

Table 3.X.

Mean howling rate (howls h⁻¹) at Location 1 across recording periods (RecP1–RecP7), with corresponding deployment dates and total number of detected howls per period.

| Recording Period |

Dates |

Total Howls |

Mean Howls (h-1) |

| RecP1 |

20 Aug–3 Sep 2021 |

29 |

0.13 |

| RecP2 |

28 Sep–13 Oct 2021 |

108 |

0.05 |

| RecP3 |

13–26 Oct 2021 |

13 |

0.07 |

| RecP4 |

26 Oct–8 Nov 2021 |

104 |

0.53 |

| RecP5 |

22 Nov–5 Dec 2021 |

56 |

0.29 |

| RecP6 |

21 Dec 2021–3 Jan 2022 |

159 |

0.48 |

| RecP7 |

7–20 Feb 2022 |

17 |

0.09 |

At Location 5 (captive wolves), mean howling rate was lowest in RecP1 (0.11 howls·h⁻¹) and higher in RecP2–RecP3 (0.45 and 0.38). Detections were concentrated around 21:00 and in the early morning hours before 06:00, with RecP1 restricted to 06:00–08:00 and RecP2–RecP3 spanning 20:00–08:00 (

Table 3.2).

Table 3.2.

All recorded wolf howls (solo, chorus) binned by hour for each recording period (RecP) in Location 5. Exact dates for each period are provided in

Table A5.2.

Table 3.2.

All recorded wolf howls (solo, chorus) binned by hour for each recording period (RecP) in Location 5. Exact dates for each period are provided in

Table A5.2.

| |

17-18 |

18-19 |

19-20 |

20-21 |

21-22 |

22-23 |

23-00 |

00-01 |

01-02 |

02-03 |

03-04 |

04-05 |

05-06 |

06-07 |

07-08 |

| RecP1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

10 |

| RecP2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

10 |

15 |

8 |

11 |

30 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

| RecP3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

19 |

3 |

9 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

14 |

2 |

5 |

In Location 5, recording period 1 had the lowest mean howls per hour (0.11). Periods 2 and 3 were higher, with period 2 the highest (0.45) and period 3 close behind (0.38).

At Location 6 (captive wolves), howling rates were substantially higher (2.86–5.05 howls·h⁻¹ across recording periods). Hourly distributions indicated concentrations in the evening and early morning hours (

Table 3.3), suggesting that calling activity may be influenced by activity around the enclosure and interactions with keepers.

Table 3.3.

All recorded wolf howls (solo, duet, chorus) sorted by time for each recording period (RecP). Recording period 2 is omitted because incorrect device timestamps prevented ordering. Howls were recorded at Location 6. Exact dates are provided in

Table A5.3.

Table 3.3.

All recorded wolf howls (solo, duet, chorus) sorted by time for each recording period (RecP). Recording period 2 is omitted because incorrect device timestamps prevented ordering. Howls were recorded at Location 6. Exact dates are provided in

Table A5.3.

| |

17-18 |

18-19 |

19-20 |

20-21 |

21-22 |

22-23 |

23-00 |

00-01 |

01-02 |

02-03 |

03-04 |

04-05 |

05-06 |

06-07 |

07-08 |

| RecP1 |

62 |

16 |

21 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

9 |

35 |

0 |

8 |

21 |

27 |

0 |

120 |

232 |

| RecP2 |

263 |

100 |

42 |

176 |

197 |

50 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

2 |

31 |

0 |

19 |

0 |

84 |

At Location 6, mean howls per hour were 2.86 in RecP1 (24 Oct–8 Nov 2021), 2.89 in RecP2 (16–30 Nov 2021), and peaked at 5.05 in RecP3 (7–30 Jan 2022), coinciding with the pre-breeding period for wolves [

35].

3.2. Individual Identification of Wolves

Linear discriminant analysis achieved 92 % correct classification: 19 howls were assigned to adult 1 (Loc 1.1) and 18 to adult 2 (Loc 1.2) (

Table 3.4). Hereafter, the two presumed adult individuals recorded at Location 1 are labelled Loc 1.1 and Loc 1.2, where Loc 1 denotes the recording site and .1/.2 are internal identifiers for each individual.

Table 3.4.

Confusion matrix from linear discriminant analysis (LDA) for individual identification at location 1. Forty presumed adult howls (n = 20 per individual; putative pup howls with high maximum fundamental frequency excluded) were classified into Loc 1.1 and Loc 1.2 using acoustic variables extracted in Praat. Rows indicate the priori individual label (assigned based on distinctive structural features in the spectrogram and audio), while columns indicate the individual label predicted by the LDA. Values on the diagonal represent correct classifications and off-diagonal values represent misclassifications. Overall classification accuracy was 92.5% (37/40), corresponding to 95% for Loc 1.1 (19/20) and 90% for Loc 1.2 (18/20).

Table 3.4.

Confusion matrix from linear discriminant analysis (LDA) for individual identification at location 1. Forty presumed adult howls (n = 20 per individual; putative pup howls with high maximum fundamental frequency excluded) were classified into Loc 1.1 and Loc 1.2 using acoustic variables extracted in Praat. Rows indicate the priori individual label (assigned based on distinctive structural features in the spectrogram and audio), while columns indicate the individual label predicted by the LDA. Values on the diagonal represent correct classifications and off-diagonal values represent misclassifications. Overall classification accuracy was 92.5% (37/40), corresponding to 95% for Loc 1.1 (19/20) and 90% for Loc 1.2 (18/20).

| |

Loc 1.1 |

Loc 1.2 |

Total |

| Loc 1.1 |

19 |

1 |

20 |

| Loc 1.2 |

2 |

18 |

20 |

| Total |

21 |

19 |

40 |

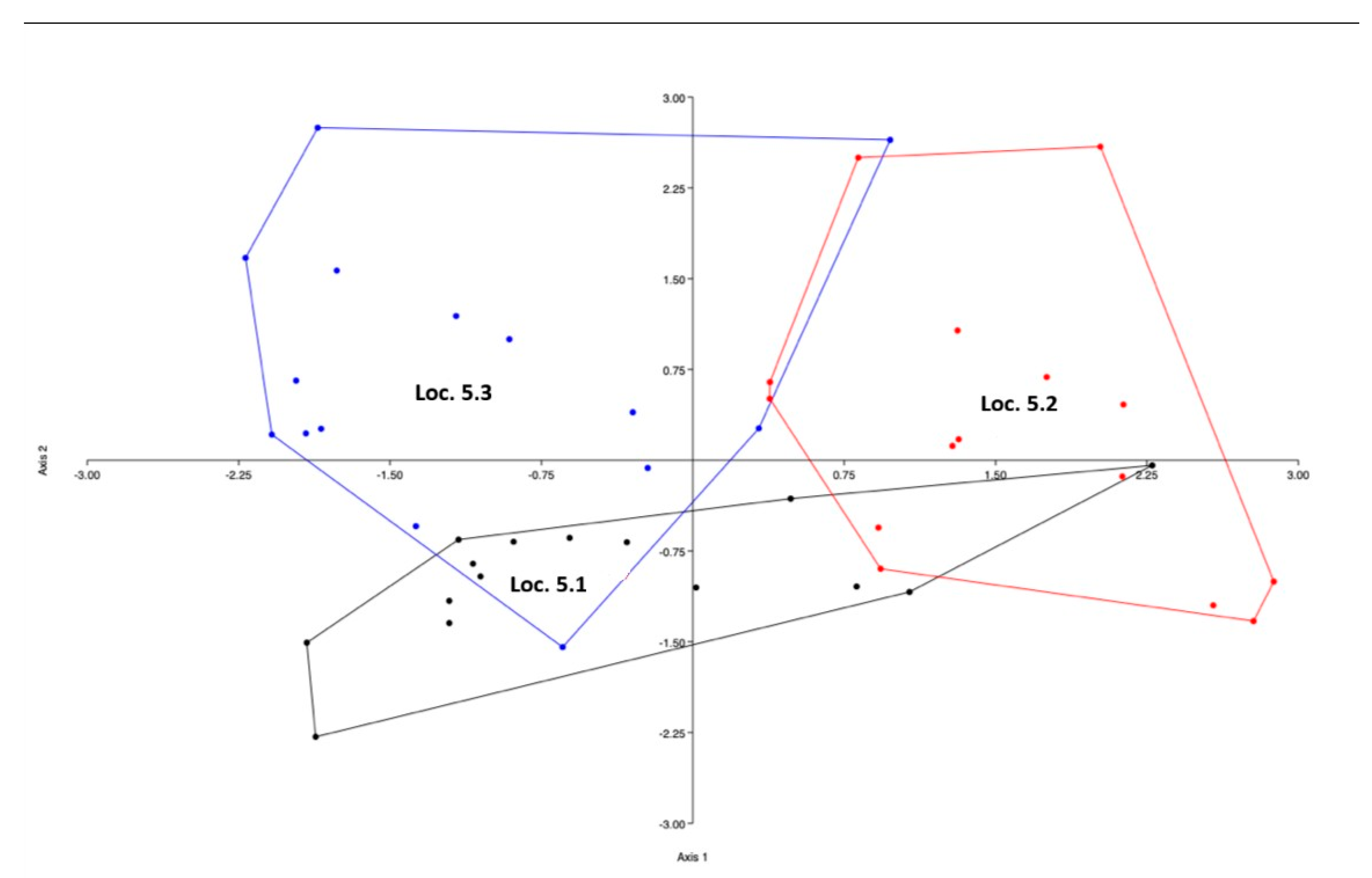

The same variables used for individual identification at Location 1 were applied to Location 5 and Location 6. For the three wolves in captivity at Location 5, the analysis achieved 84 % correct classification: 13 howls were assigned to Loc 5.1, 15 to Loc 5.2, and 10 to Loc 5.3 (

Table 3.5). Fifteen howls per individual were used in the analysis.

Table 3.5.

Confusion matrix from linear discriminant analysis of howls recorded at Location 5, showing the number of calls classified to adult 1 (Loc 5.1), adult 2 (Loc 5.2), and adult 3 (Loc 5.3).

Table 3.5.

Confusion matrix from linear discriminant analysis of howls recorded at Location 5, showing the number of calls classified to adult 1 (Loc 5.1), adult 2 (Loc 5.2), and adult 3 (Loc 5.3).

| |

Loc 5.1 |

Loc 5.2 |

Loc 5.3 |

Total |

| Loc 5.1 |

13 |

2 |

0 |

86.7 % |

| Loc 5.2 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

100 % |

| Loc 5.3 |

3 |

2 |

10 |

66.7 % |

| Total |

16 |

19 |

10 |

|

The corresponding LDA plot displays the relative positions of howls assigned to the three individuals. The groups show overlap, and some calls were classified using linear discriminant analysis (LDA). (

Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4.

Linear discriminant analysis plot showing the placement of correctly classified howls relative to the other individuals. All howls were recorded at Location 5.

Figure 3.4.

Linear discriminant analysis plot showing the placement of correctly classified howls relative to the other individuals. All howls were recorded at Location 5.

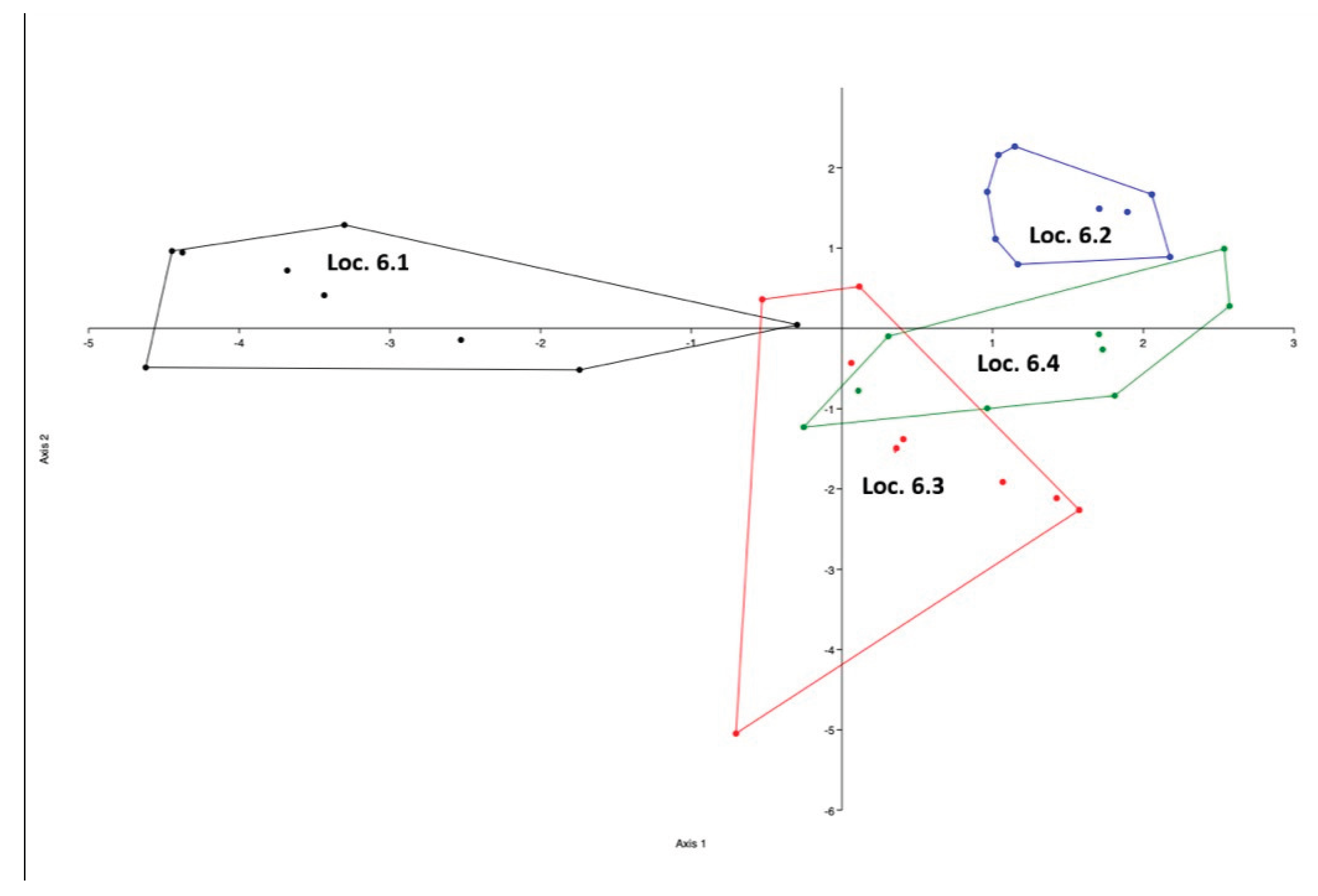

From Location 6, four individuals were assigned nine howls each for linear discriminant analysis. Using the selected variables, classification accuracy was 86 %. Wolf 1 (Loc 6.1) and Wolf 2 (Loc 6.2) achieved the highest individual accuracies— 89 % and 100%, respectively (

Table 3.6).

Table 3.6.

Confusion matrix from linear discriminant analysis of howls recorded at Location 6, showing the number of calls classified to adult 1 (Loc 6.1), adult 2 (Loc 6.2), adult 3 (Loc 6.3), and adult 4 (Loc 6.4).

Table 3.6.

Confusion matrix from linear discriminant analysis of howls recorded at Location 6, showing the number of calls classified to adult 1 (Loc 6.1), adult 2 (Loc 6.2), adult 3 (Loc 6.3), and adult 4 (Loc 6.4).

| |

Loc 6.1 |

Loc 6.2 |

Loc 6.3 |

Loc 6.4 |

Total |

Correct Classification (%) |

| Loc 6.1 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

88.9 |

| Loc 6.2 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

100 |

| Loc 6.3 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

2 |

9 |

77.8 |

| Loc 6.4 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

9 |

77.8 |

| Total |

8 |

10 |

8 |

10 |

36 |

|

The LDA plot shows overlap between calls assigned to wolf 2 (Loc 6.2) and wolf 3 (Loc 6.3), with some misclassifications. By contrast, calls for wolf 1 (Loc 6.1) form a distinct, non-overlapping cluster, consistent with its 100 % accuracy. Loc 6.2 exhibits limited overlap only with Loc 1.3, matching its 89 % accuracy (

Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5.

Linear discriminant analysis plot showing the placement of correctly classified howls relative to other individuals. All howls were recorded at Location 6.

Figure 3.5.

Linear discriminant analysis plot showing the placement of correctly classified howls relative to other individuals. All howls were recorded at Location 6.

3.3. Identification of Howls from Pups

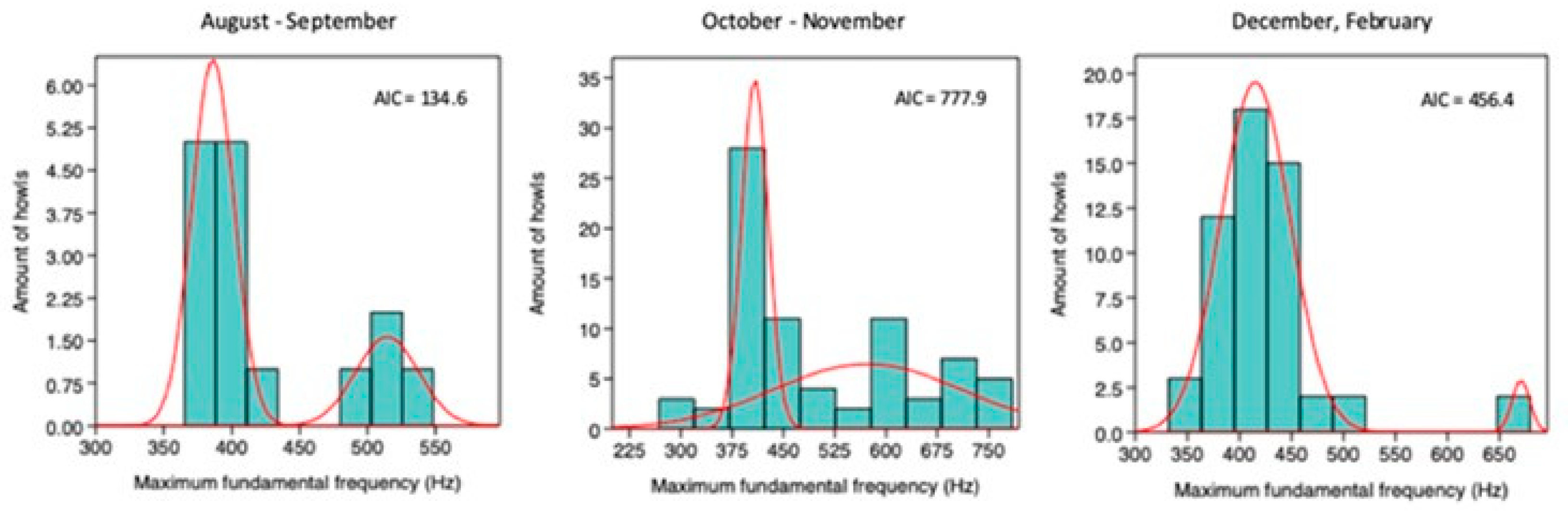

Monthly mixture analyses of Max F0 at Location 1 indicated an optimal two-group solution (k = 2) based on the lowest AIC. Across months, the higher–Max F0 cluster shifted toward lower values, consistent with pup maturation and the age-related decline in howl frequency. By December and February, only two howls exceeded 600 Hz, while the remainder had shifted to lower maximum (app.

Figure A5.2). In each monthly analysis, MANOVA confirmed a significant separation between the two groups, indicating clear bimodality in the data (

Table 3.7).

Table 3.7.

MANOVA indicated that the two-group solution (k = 2) was significant for every month.

Table 3.7.

MANOVA indicated that the two-group solution (k = 2) was significant for every month.

| |

k |

λ |

p |

F |

| August – September |

2 |

0.14 |

*** |

7.27 E06 |

| October – November |

2 |

0.25 |

*** |

110.8 |

| December, February |

2 |

7.97 E-149 |

*** |

3.20 E149 |

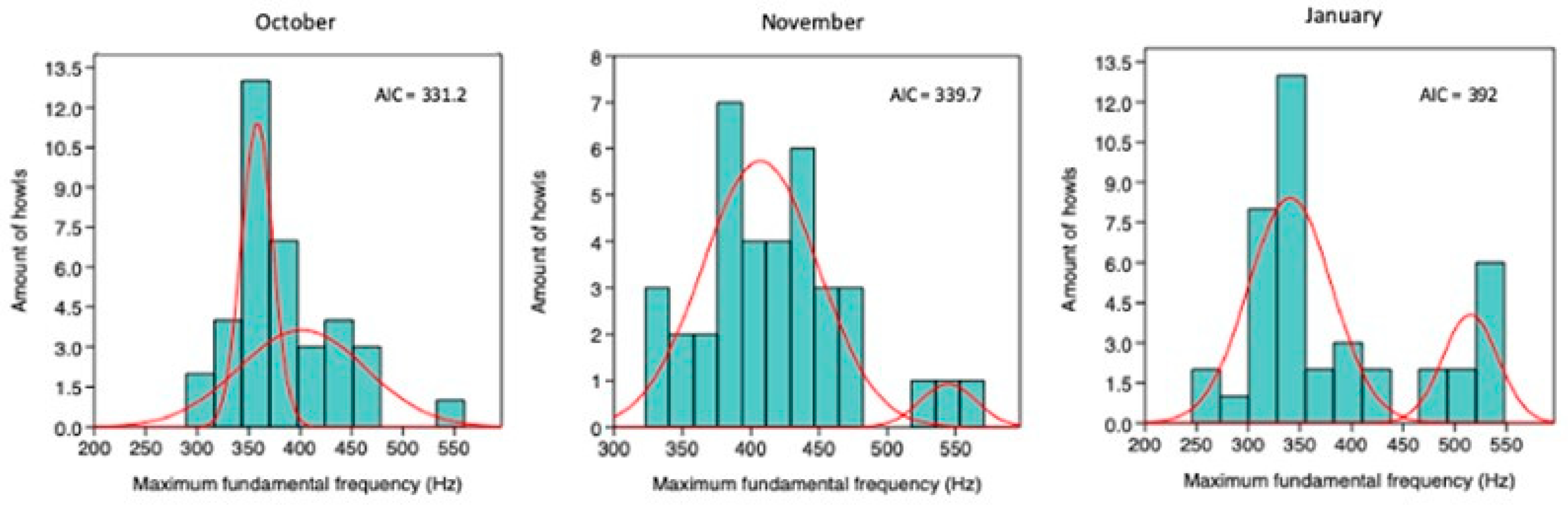

Mixture analysis of Max F0 in Location 6 indicated two groups (k = 2) as the optimal solution based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (

Figure 3.7). As in Location 1, the cluster with higher maximum fundamental frequencies shifted toward lower values over time, consistent with pup maturation. By January, the separation between the lower- and higher-frequency groups was smaller than in October (app.

Figure A5.3). For each month, a MANOVA with k = 2 confirmed a significant difference between groups, indicating a consistent bimodal structure.

Table 3.8.

MANOVA indicated that, for each month, the two-group solution (k = 2) was significant.

Table 3.8.

MANOVA indicated that, for each month, the two-group solution (k = 2) was significant.

| |

K |

λ |

p |

F |

| October |

2 |

0.26 |

*** |

49.5 |

| November |

2 |

0.09 |

*** |

162.3 |

| January |

2 |

0.16 |

**** |

103.5 |

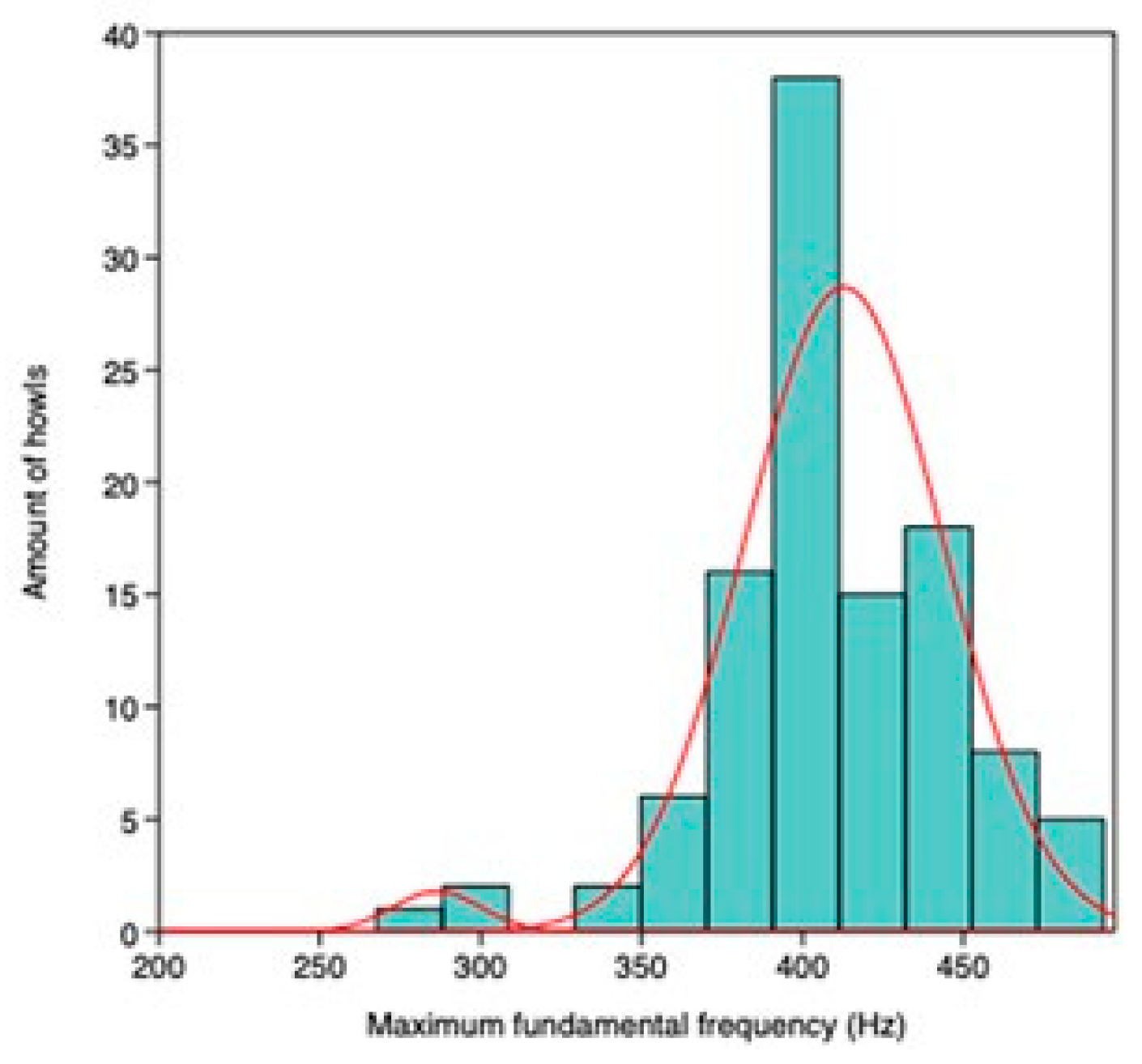

3.4. Identification of Howls from Female and Male Wolves

When testing whether howls from Location 1 could be partitioned by sex, a mixture analysis of Max F0 values < 500 Hz supported a two-group model (k = 2; AIC = 897.4) (app.

Figure A5.4). Principal Component Analysis further indicated a clear two-cluster structure (app.

Figure A5.5). MANOVA confirmed significant group separation (Wilks’ λ = 0.09, F = 539.5,

p< 0.001), indicating two distinguishable groups within the data.

A mixture analysis of howls from Location 5 indicated a two-group solution (AIC = 675.8). All howls were included, as no pups were present. A PCA plot illustrates the separation between groups. MANOVA confirmed significant differentiation (Wilks’ λ = 0.11, F = 291.1, p< 0.001), further supporting that the groups are distinct.

3.5. Eliciting Howls by Auditory Stimulation

No wolves responded to the playbacks by howling at either Location 5 or Location 6, though they did react behaviorally to some stimuli. At Location 5, overall interest was low. Early in the session, ambulance sirens and a female Arctic wolf’s howl elicited brief activity: the wolves ran around the enclosure, and during one howl playback, all three wagged their tails. By contrast, church-bell stimuli produced weak reactions, and by 42 minutes, all three wolves were lying down with no apparent response. Throughout, they frequently oriented toward the speaker and the observer. During the 10-minute intermissions, all wolves typically lie down. At the 10th clip, only one wolf stood and moved around for ~2 minutes before rejoining the others; at the 11th clip, none stood, and during the final 30 minutes, all three remained recumbent with no observable reaction (

Table 3.9).

Table 3.9.

The three wolves at Location 5 did not howl in response to the playback stimuli; accordingly, vocal responses are not shown. They did, however, exhibit non-vocal reactions. “Active reaction” denotes overt bodily movements; “no reaction” indicates no, or only minimal, observable change in behavior during and after playback. Audio clips were presented with 10-minute intermissions. At 14:00, a clip was played inadvertently, and the subsequent interval was extended by 2 minutes.

Table 3.9.

The three wolves at Location 5 did not howl in response to the playback stimuli; accordingly, vocal responses are not shown. They did, however, exhibit non-vocal reactions. “Active reaction” denotes overt bodily movements; “no reaction” indicates no, or only minimal, observable change in behavior during and after playback. Audio clips were presented with 10-minute intermissions. At 14:00, a clip was played inadvertently, and the subsequent interval was extended by 2 minutes.

| Time |

Audio Clip |

Behavioural Responses |

| 12.30 |

Ambulance |

Active reaction – two wolves immediately started running around the enclosure. Last wolf had no reaction. |

| 12.40 |

Wolf howl |

Active reaction – all wolves running around the enclosure. Seemingly looking for the sound. |

| 12.50 |

Church bells |

Wolves out of sight. |

| 13.00 |

Ambulance |

Active reaction – two wolves seeking the sound near the speaker. Last wolf had no reaction in the beginning but eventually followed the reaction of the others. |

| 13.10 |

Wolf howl |

Two wolves reacted after the third playback by running around the enclosure after the audio clip ended. Last wolf did not react. |

| 13.20 |

Church bells |

No reaction. One wolf looked in our direction when the last sound of the bells played. |

| 13.30 |

Ambulance |

Two wolves stood up – last wolf was lying down during and after the audio clip. |

| 13.40 |

Wolf howl |

All wolves wagged their tales. |

| 13.50 |

Wolf howl |

One wolf walked around the enclosure but at last, joined the other two wolves laying down. |

| 14.00 |

Wolf howl |

One wolf walked around the enclosure during the first minute of the audio clip, and shortly joined the other two who were laying down, |

| 14.12 |

Wolf howl |

No reaction – all three wolves were laying down. |

| 14.22 |

Ambulance |

No reaction – all three wolves were laying down. |

| 14.32 |

Ambulance |

No reaction – all three wolves were laying down. |

The wolves at Location 6 did not howl in response to the playbacks, but they did exhibit other reactions. During the third bell playback, pre-howling cues were observed: wolves moved around one another and lifted their heads. Similar behavior occurred during the second playback of the Arctic female howl, when whining was noted. A wolf-duet playback also elicited orienting responses toward the speaker, and archival playbacks of the pack’s 2020 howls prompted some movement [

16]. Linear discriminant analysis achieved 92% correct classification at Location 1 (40 solo adult howls; three misclassifications), indicating that two free-ranging adults could be distinguished using fundamental-frequency features. This performance is consistent with earlier work showing strong individual signatures in wolf howls. For example, Larsen et al. (2022) reported perfect (100%) individual classification for multiple wolves using discriminant analysis of howl features, and Root-Gutteridge et al. (2014) reported 100% correct classification for solo howls (and 97.4% for choruses) when combining fundamental-frequency and amplitude metrics. Our slightly lower accuracy relative to these best-case values likely reflects the more variable conditions of field recordings (e.g., distance and environmental noise) and our reliance on a limited set of frequency-based predictors. Importantly, accuracy declined when more individuals were classified in the captive datasets (84% for three wolves at Location 5; 86% for four wolves at Location 6), highlighting the expected increase in overlap as the number of individuals rises. Choruses were excluded from Location 1 for individual identification because overlapping calls prevented reliable pitch extraction; however, previous work suggests that incorporating chorus information—when individual contours can be resolved—may further strengthen population-level inference because choruses typically include contributions from multiple pack members. (

Table 3.10).

Table 3.10.

The eleven wolves at Location 6 did not howl in response to the playbacks; accordingly, vocal responses are not shown. Other behaviors were observed. “Active reaction” includes running, walking, and orienting within the enclosure or toward the sound. “No reaction” indicates that none of the wolves changed position before or after the clips; individuals remained lying or sitting. The session was paused 30 minutes after the start for a 30-minute public activity with the wolves.

Table 3.10.

The eleven wolves at Location 6 did not howl in response to the playbacks; accordingly, vocal responses are not shown. Other behaviors were observed. “Active reaction” includes running, walking, and orienting within the enclosure or toward the sound. “No reaction” indicates that none of the wolves changed position before or after the clips; individuals remained lying or sitting. The session was paused 30 minutes after the start for a 30-minute public activity with the wolves.

| Time |

Audio Clip |

Reactions |

| 10.40 |

Wolf duet |

Action reaction – many in the pack looked towards the sound |

| 10.50 |

Wolf duet |

Action reaction – many in the pack looked towards the sound |

| 11.00 |

Wolf duet |

Action reaction – many in the pack looked towards the sound |

| 11.10 |

Wolf duet |

Action reaction – many in the pack looked towards the sound |

| 11.54 |

Bell sounds |

Active reaction – wolves running around the enclosure during the audio clip. Distracted by a tractor passing by. |

| 12.04 |

Bell sounds |

No reaction. |

| 12.14 |

Bell sounds |

Active reaction – showed signs of howling behavior. Audio played two times. |

| 12.24 |

Bell sounds |

No reaction – distracted by a tractor passing by in the beginning of the audio clip. |

| 12.34 |

Wolf howl |

Active reaction – some movements from some of the wolves. Alpha male did not react. |

| 12.44 |

Wolf howl |

Audio played two times. Active reaction – whines and showed signs of howling behavior. Guests appeared during the audio clip. |

| 12.54 |

Wolf howl |

No reaction – guest appeared during the audio clip. |

| 13.04 |

Wolf howl |

No reaction – guest appeared during the audio clip. |

| 13.14 |

Ambulance |

Active reaction – wolves played before during and after the audio clip. |

| 13.24 |

Bell sounds |

No reaction. |

| 13.34 |

Bell sounds |

No reaction. |

| 13.44 |

Sound mix |

No reaction. |

| 13.54 |

Loc 6 howls (2020) |

Audio played two times.

Active reaction – some movements. |

| 14.04 |

Imitated howls |

No reaction. |

| 14.14 |

Loc 1 howls (2021) |

No reaction. |

| 14.24 |

Loc 1 howls (2021) |

No reaction. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Howling Activity of Wild and Captive Wolves

At Location 6, howling activity was higher in RecP3 (January 2022) than in the two earlier periods (RecP1–RecP2; October–November 2021); this increase was statistically significant (Poisson rate model with recording hours as exposure: RecP3 vs. RecP1 RR = 1.87, 95% CI 1.69–2.08,

p < 0.001; RecP3 vs. RecP2 RR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.58–1.94,

p < 0.001), whereas RecP1 vs. RecP2 was not significant (

p = 0.26). In a ten-year study of Yellowstone’s Northern Range, McIntyre et al. (2017) [

35] delineated seasonal phases: pre-breeding (December–January), breeding (February), post-breeding (March), denning (April), and pups in the den (May). Accordingly, our three high-activity periods align with pre-breeding and its lead-up, when elevated howling is also reported [

36,

37].

At Location 5, mean howls per hour peaked in period 2 (16–29 November), mirroring the elevated autumn calling at Location 1. Rates declined slightly in period 3 (17–31 January), consistent with McIntyre et al. (2017) [

35], who found lower calling during pre-breeding. Wolves in captivity at Location 5 howled somewhat more in the early morning, possibly reflecting keeper activity [

38]. Wild wolves at Location 1 called more sporadically through the night, although period 4 showed an evening maximum between 19:00 and 21:00, in line with reports of calling from sunset to sunrise [

27].

Location 1 yielded many detections. Recording began on 20 August 2021, when pups typically increase participation in howling [

18,

22]. Joslin (1967) [

18], studying captive timber wolves (

Canis lupus lycaon) in Algonquin Park, observed more howling in July–August; by September–October, pups howled independently in 13% of events. At Location 1, averages peaked in late autumn (period 4), consistent with McIntyre et al. (2017) [

25], who documented increased fall howling as pups begin travelling with the pack. Rates then declined in February—when breeding presumably occurs—contrary to some reports [

31,

36,

39,

40]. Note that the Location 1 deployments did not cover entire months or a full year, leaving gaps that may affect comparisons.

At Location 3, six howls were detected near the time a female was first photographed with a male: one on 24 October, four on 3 November, and one on 27 November. No howls were recorded at Location 4 despite its long-standing status as a wolf territory and camera evidence of a pair in 2021 [

10]. Field signs (feces, tracks, photographs) were scarce—atypical of an established pair—suggesting the wolves may have left the area [

10]. Sites with detections hosted more than one wolf, implying that absence at Location 4 could reflect either true absence during the study or recorders placed beyond detection range, even though howling had previously been heard there. No howls were detected at Location 2, where a single male has been observed since May 2021 with no reports of conspecifics.

Harrington and Mech (1979) [

36] examined responses to simulated howls in northeastern Minnesota: lone wolves replied in only two of 29 sessions—and only when at least two wolves were near the same kill—whereas packs responded far more often, with larger packs more likely to answer. Thus, lone wolves are typically less vocal than packs. Being solitary carries risks, and lone wolves tend to avoid packs [

41,

42]. This behavioural tendency may limit the effectiveness of acoustic monitoring, as the method relies on wolves vocalizing within the surveyed areas.

4.2. Individual Identification of Wolves

Linear discriminant analysis achieved 92 % correct classification, demonstrating that the two wolves at Location 1 could be reliably identified. Other bioacoustics studies have likewise successfully identified individuals from howls [

16,

21]. Larsen et al. (2022) [

16] showed that both Eurasian and Arctic wolves can be identified with high accuracy using fundamental-frequency features in discriminant analysis, reporting 100% correct classification for multiple individuals of both subspecies. Similarly, Root-Gutteridge et al. (2014) [

21] achieved 100% correct classification for solo howls and 97.4% for choruses by combining fundamental-frequency and amplitude metrics. Choruses from Location 1 were excluded here because overlapping calls prevented reliable pitch extraction; nonetheless, incorporating choruses in future work could be informative, as pack howls generally include contributions from most, and often all, members of the pack and may provide a rapid means to estimate the number of individuals in an area [

18,

23].

4.3. Identification of Howls from Pups and Separating Howls from Male and Female Wolves

The highest Max F0 observed in this study was 785 Hz, the lowest was 268 Hz and the median Max F0 across all recordings was 393.4 Hz. Mixture analysis separated higher- from lower-Max F0 howls; 27 howls with Max F0 of 552–785 Hz are tentatively attributed to pups, though further validation is needed to confirm age-based grouping. Wolfes studies in captivity would be optimal for ground-truthing by linking acoustic recordings to visually verified individuals. Coscia (1995) [

20] tracked pup vocal development from birth to six weeks, reporting howls up to ~1100 Hz at two weeks that declined to ~704 Hz by six weeks. Accordingly, additional bioacoustics work in areas where pups emerging from dens would help distinguish pups from adult howls. Harrington and Mech (1978) [

31] did not clearly separate older pups from adults but documented structural maturation (deeper, longer howls), with pup howls shorter on average; early pup howls may peak without the typical terminal drop [

20]. Such patterns could facilitate non-invasive detection of reproducing packs. The observed seasonal decline in Max F0, consistent with pup maturation, has important implications for acoustic monitoring. High frequency howls early in the season may serve as indicators of reproducing packs, whereas later recording dominated by lower frequencies could obscure pub presence. Highlighting this temporal pattern can help refine monitoring protocols by identifying optimal periods for detecting breeding activity.

A separate mixture analysis of Max F0 < 500 Hz identified 64 howls likely produced by adults at Location 1 and resolved two clusters, one calling more frequently and at higher frequencies. This group may represent the female, with the smaller, lower-frequency cluster representing the male. Although breeding females can be relatively silent early in the pup stage [

18], our recordings began when pups were ~4 months old. Females often predominate in pup care and protection, whereas males range more widely for foraging [

43]; if higher-frequency calls belong to the female, increased calling could reflect pup-related coordination or territorial warning. This behavioural pattern suggests that mid-summer, when females are more stationary near dens to care for pups, may represent an optimal period for detecting breeding status through acoustic monitoring. Definitive sex assignment will require controlled settings (e.g., wolves in captivity) where individuals can be observed and matched to howls. Therefore, this is a limitation in its application in the field. Finally, low-frequency hoarser howls were difficult to analyze because F0 bands were less distinct on spectrograms; these were excluded. Improved methods for extracting Max F0 from such signals could sharpen male–female differentiation and clarify sex-specific howling behavior.

An important methodological limitation is that some low-frequency, hoarse howls could not be analysed reliably because the fundamental-frequency band was indistinct on spectrograms, and these calls were therefore excluded from maximum fundamental-frequency–based analyses. This exclusion may reduce sensitivity to a subset of adult vocalisations and could bias sex-related inference if such hoarse/low-frequency howls are produced disproportionately by one sex or age class. Future work should test more robust pitch-extraction approaches and validate sex and age assignments in controlled conditions where callers can be visually confirmed.

5. Conclusions

Passive acoustic monitoring (sunset–sunrise) quantified wolf howling in Denmark during a single window (late Aug 2021–Feb 2022) in free-ranging and captive packs. Wild detections were largely confined to one site that yielded sufficient high-quality solo howls for individual-level analyses; most other sites produced few or no detections, underscoring sensitivity to site selection and recorder placement. Fundamental-frequency descriptors supported reliable individual discrimination and identified a high-frequency cluster that decreased over successive months, consistent with pup vocal maturation within the sampled period. A stable two-cluster structure within the adult range may reflect sex-related differences but requires ground-truth validation. Playback trials in captivity elicited behavioral responses without triggering howling, suggesting limited efficacy under the tested conditions. This will need more investigation to ensure successful howling activity from wild wolves. Because no spring–summer data were collected, annual seasonality cannot be inferred, and captive daily vocal patterns should not be compared to seasonal howling in the wild.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O. and L.Ø.J.; methodology, P.O. and L.Ø.J; software, P.O and L.Ø.J; validation, P.O. and L.Ø.J; formal analysis, P.O. and L.Ø.J; investigation, P.O. and L.Ø.J; resources, P.O. and L.Ø.J; data curation, P.O., L.Ø.J, C.P. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.O., L.Ø.J, C.P and S.P.; writing—review and editing, C.P. and S.P.; visualization, P.O., L.Ø.J; supervision, C.P. and S.P.; project administration, C.P. and S.P.; funding acquisition, C.P. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Aalborg Zoo Conservation Foundation AZCF: Grant number 07-2025 and The APC was funded by AZFC: 07-2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The following scientific study did not require an Institutional Review Board Statement, in accordance with current regulations. Not applicable.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was not required for this study and is therefore not applicable. The work relied exclusively on passive acoustic monitoring and non-invasive behavioral observations. Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the first and the second author on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance provided by wildlife parks and zoos for giving us access to their facilities after dark, and to the landowners who have wolves on their property or nearby for helping us install acoustic monitoring equipment. A special thanks goes to Ulvetracking.dk, Aage V. Jensen Nature Foundation, Lille Vildmose, Klelund Dyrehave and Janne Tofte, Scandinavian Wildlife Park. We also extend our sincere gratitude to Hanne Lyngholm Larsen for allowing us to use data from her master’s thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC |

Akaike Information Criterion |

| AZCF |

Aalborg Zoo Conservation Foundation |

| CEWP |

Central European Wolf Population |

| EU |

European Union |

| F0 |

Fundamental Frequency |

| Max F0 |

Maximum Fundamental Frequency |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier Transform |

| HMM |

Hidden Markov Model |

| IUCN |

International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| LDA |

Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| RecP |

Recording Period |

| SM4 |

Song Meter SM4 (bioacoustic recorder) |

| WAV |

Waveform Audio File Format |

| Loc. 1 |

Location with wild wolves |

| Loc. 2 |

Location with wild wolves |

| Loc. 3 |

Location with wild wolves |

| Loc. 4 |

Location with wild wolves |

| Loc. 5 |

Location with captive wolves |

| Loc. 6 |

Location with captive wolves |

| PAM |

Passive Acoustic Monitoring |

| SCALP |

Status and Conservation of the Alpine Lynx Population |

Appendix

Table A5.1.

Overview of recording periods, sites, recording schedules, and number of howls detected at Loc 1.

Table A5.1.

Overview of recording periods, sites, recording schedules, and number of howls detected at Loc 1.

| Recording Period |

Recording Period (Dates) |

Recording Schedule |

Solo Howls |

Duets |

Chorus |

Total Howls |

Average Howls pr. Hour |

| RecP1* |

20/8/2021 – 3/9/2021 |

20:00 – 7:00 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| RecP1 |

20/8/2021 – 3/9/2021 |

20:00 – 7:00 |

29 |

0 |

0 |

29 |

0.13 |

| RecP2 |

28/9/2021 – 13/10/2021 |

19:00 – 8:00 |

106 |

2 |

0 |

108 |

0.052 |

| RecP3 |

13/10/2021 – 26/10/2021 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

13 |

0.07 |

| RecP4 |

26/10/2021 – 8/11/2021 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

104 |

0 |

0 |

104 |

0.53 |

| RecP5 |

22/11/2021 – 5/12/2021 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

48 |

5 |

3 |

56 |

0.29 |

| RecP6 |

21/12/2021 – 3/1/2022 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

129 |

20 |

10 |

159 |

0.48 |

| RecP7 |

7/2/2022 – 20/2/2022 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

8 |

1 |

8 |

17 |

0.09 |

Table A5.2.

Overview of recording periods, sites, recording schedules, and number of howls detected at Loc 2.

Table A5.2.

Overview of recording periods, sites, recording schedules, and number of howls detected at Loc 2.

| Recording Period |

Location |

Recording Period (Dates) |

Recording Schedule |

Solo Howls |

Duets |

Chorus |

Total Howls |

Average Howls pr. Hour |

| RecP1 |

By enclosure |

28/10/2021 – 11/11/2021 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

0.11 |

| RecP2 |

By enclosure |

16/11/2021 – 29/11/2021 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

87 |

0 |

1 |

88 |

0.45 |

| RecP3 |

By enclosure |

17/01/2022 – 31/01/2022 |

17:00 – 8:00 |

69 |

0 |

6 |

75 |

0.35 |

Figure A5.1.

Example spectrograms of a pup howl (top) and an adult howl (bottom), each annotated with its maximum fundamental frequency (Max F0).

Figure A5.1.

Example spectrograms of a pup howl (top) and an adult howl (bottom), each annotated with its maximum fundamental frequency (Max F0).

Figure A5.2.

Mixture analysis of the maximum fundamental frequency of howls recorded at Location 1 from August 2021 to February 2022 (January excluded due to no detections). Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values are reported for each analysis.

Figure A5.2.

Mixture analysis of the maximum fundamental frequency of howls recorded at Location 1 from August 2021 to February 2022 (January excluded due to no detections). Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values are reported for each analysis.

Figure A5.3.

Mixture analysis of the maximum fundamental frequency of howls recorded in October, November, and January at Location 6. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values are reported for each analysis.

Figure A5.3.

Mixture analysis of the maximum fundamental frequency of howls recorded in October, November, and January at Location 6. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values are reported for each analysis.

Figure A5.4.

Mixture analysis of maximum fundamental frequencies ≤ 500 Hz for howls recorded from August 2021 to February 2022.

Figure A5.4.

Mixture analysis of maximum fundamental frequencies ≤ 500 Hz for howls recorded from August 2021 to February 2022.

Figure A5.5.

Mixture analysis of maximum fundamental frequencies for howls recorded in October, November, and January a Location 5.

Figure A5.5.

Mixture analysis of maximum fundamental frequencies for howls recorded in October, November, and January a Location 5.

References

- Boitani, L. Wolf Conservation and Recovery. In Chapter 13 Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation; Mech, L.D., Boitani, L., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003; pp. 317–340. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, C.; Holzapfel, M.; Kluth, G.; Reinhardt, I.; Ansorge, H. Wolf (Canis lupus) Feeding Habits During the First Eight Years of Its Occurrence in Germany. Mammalian Biology 2012, 77(3), 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, A.B.; Andersen, L.W.; Sunde, P. Ulve i Danmark—hvad kan vi forvente? DCE—Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi, Aarhus University: Aarhus, Denmark, 2013; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.S.; Olsen, K.; Sunde, P.; Vedel-Smith, C.; Madsen, A.B.; Andersen, L.W. Genindvandring af Ulven (Canis lupus) i Danmark. Flora og Fauna 2015, 121, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Randi, E. Genetics and Conservation of Wolves Canis lupus in Europe. Mammal Review 2011, 41(2), 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention), No. 104; Council of Europe.: Bern, Switzerland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Boitani, L.; Phillips, M.; Jhala, Y. Canis lupus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3746/163508960 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Reinhardt, I.; Kluth, G.; Nowak, S.; Mysłajek, R.W. Standards for the Monitoring of the Central European Wolf Population in Germany and Poland. In Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN) Federal Agency for Nature Conservation; Bonn, Germany, 2015; Volume 398, pp. 2–46. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, K.; Sunde, P. Antallet af ulve i Danmark. Oktober 2012-februar 2025; Aarhus University, DCE—National Centre for Environment and Energy: Aarhus, Denmark, 2025; Volume 26, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, K.; Sunde, P.; Vedel-Smith, C.; Hansen, M.; Thomsen, P. Status rapport fra den nationale overvågning af ulv (Canis lupus) i Danmark– 3. kvartal 2021; Aarhus University, DCE—National Centre for Environment and Energy: Aarhus, Denmark, 2021; Volume 86, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- DBBW. Scalp Criteria. Dokumentations- und Beratungsstelle des Bundes zum Thema Wolf. Available online: https://www.dbb-wolf.de/wolf-management//scalp-criteria (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Sunde, P.; Olsen, K. Ulve (Canis lupus) i Danmark 2012-2017. Oversigt og analyse af tilgængelig bestandsinformation; Aarhus University, DCE—National Centre for Environment and Energy: Aarhus, Denmark, 2018; Volume 258, pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, E.; Gibb, R.; Glover-Kapfer, P.; Jones, K.E. Passive Acoustic Monitoring in Ecology and Conservation; WWF-UK: Woking, UK, WWF Conservation Technology Series; 2017; Volume 1, 2, pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sugai, L.S.M.; Silva, T.S.F.; Ribeiro, J.W., Jr.; Llusia, D. Terrestrial Passive Acoustic Monitoring: Review and Perspectives. BioScience 2018, 69(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papin, M.; Pichenot, J.; Guérold, F.; Germain, E. Acoustic Localization at Large Scales: A Promising Method for Grey Wolf Monitoring. Frontiers in Zoology 2018, 15(11), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H.L.; Pertoldi, C.; Madsen, N.; Randi, E.; Stronen, A.V.; Root-Gutteridge, H.; Pagh, S. Bioacoustic Detection of Wolves: Identifying Subspecies and Individuals by Howls. Animals 2022, 12(5), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, S.M.; Giordano, M.; Nietlispach, S.; Apollonio, M.; Passilongo, D. Non Invasive Acoustic Detection of Wolves. Bioacoustics 2016, 26(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslin, P.W.B. Movements and Home Sites of Timber Wolves in Algonquin Park. AM. Zoologist 1967, 7, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, S.; Root-Gutteridge, H.; Habib, B. Identifying Uknown Indian Wolves by Their Distinctive Howls: Its Potential as a Non-invasive Survey Method. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, E.M. Ontogeny of Timber Wolf Vocalizations: Acoustic Properties and Behavioural Contexts. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalhousie University, Canada, 1995. Available online: https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/items/17ef6d5b-0994-475e-84b0-c4c6ad8cce6f (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Root-Gutteridge, H.; Bencsik, M.; Chebli, M.; Gentle, L.K.; Terrell-Nield, C.; Bourit, A.; Yarnell, R.W. Identifying Individual Wild Eastern Grey Wolves (Canis lupus lycaon) Using Fundamental Frequency and Amplitude of Howls. Bioacoustics. The International Journal of Animal Sound and its Recording 2014, 21(1), 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, F.H.; Asa, C.S.; Mech, L.D.; Boitani, L. Wolf Communication. In Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 2003; pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- Theberge, J.B.; Falls, J.B. Howling as Means of Communication in Timber Wolves. American Zoologist 1967, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, V.; Font, E.; Márquez, R. Iberian Wolf Howls: Acoustic Structure, Individual Variation, and a Comparison with North American Populations. Journal of Mammalogy 2007, 88(3), 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, K.; Say-Sallaz, E.; Clinchy, M.; Pallari, N.; Szewczyk, M.; Churski, M.; Szafrańska, P.A.; Gehrke, M.; Kirsch, A.J.; Dembek, P.; et al. Wolves and their prey all fear the human "super predator. Current Biology 2025, 35(20), 5111–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.; Theberge, J.B.; Theberge, M.T.; Smith, D.W. Behavioral and Ecological Implications of Seasonal Variation in the Frequency of Daytime Howling by Yellowstone Wolves. Journal of Mammalogy 2017, 98(3), 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K. Ulveparret i Ulfborg-reviret er Forsvundet. 2022b. Available online: https://www.ulveatlas.dk/nyheder/ulveparret-i-ulfborg-reviret-er-forsvundet/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Nowak, S.; Jędrzejewski, W.; Schmidt, K.; Theuerkauf, J.; Mysłajek, R.W.; Jędrzejewska, B. Howling Activity of Free-ranging Wolves (Canis lupus) in the Białowieża Primeval Forest and the Western Beskidy Mountains (Poland). Journal of Ethology 2007, 25(3), 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, H.; Olsen, K.; Sunde, P. Danske Ulves (Canis lupus lupus) Døgnaktivitets mønster Studeret med brug af Vildtkameraer. Flora og Fauna 2019, 125, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wildlife Acoustics Inc. Kaleidoscope pro 5 user guide. Technical report, Maynard, Mas sachusetts: Wildlife Acoustics Inc. 2020. Available online: https://www.wildlifeacoustics.com/uploads/user-guides/Kaleidoscope11112024.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Harrington, F.H.; Mech, L.D. Wolf vocalization. In Wolf and Man: Evolution in Parallel; Hall, R.L., Sharp, H.S., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.; Ryan, P. Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 2001, 4(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett, J. Sound Library- Wolves. 2020. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/photosmultimedia/sounds-wolves.htm (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- McIntyre, R.; Theberge, J.B.; Theberge, M.T.; Smith, D.W. Behavioral and Eco logical Implications of Seasonal Variation in the Frequency of Daytime Howling by Yellowstone Wolves. Journal of Mammalogy 2017, 98(3), 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, F.H.; Mech, L.D. Wolf Howling and Its Role in Territory Maintenance. Behaviour 1979, 68(3/4), 207–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaneza1, L.A.O.; Palacios, V.; Uzal, A. Monitoring Wolf Populations Using Howling Points Combined with Sign Survey Transects. Wildlife Biology in Practice 2005, 1(2), 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, V.; Barber-Meyer, S.M.; Martí-Domken, B.; Schmidt, L.J. Assessing Spontaneous Howling Rates in Captive Wolves Using Automatic Passive Recorders. Bioacoustics 2021, 31(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, F.H.; Mech, L.D. An Analysis of Howling Response Parameters Useful for Wolf Pack Censusing. The Journal of Wildlife Management 1982, 46(3), 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servín, J. Duration and Frequency of Chorus Howling of the Mexican Wolf (Canis Lupus Baileyi). Acta zoológica mexicana 2000, 80, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, R.J.; Mech, D.L. Scent-Marking in Lone Wolves and Newly Formed Pairs. Animal behaviour 1979, 27, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritts, S.H.; Mech, L.D. Dynamics, Movements, and Feeding Ecology of a Newly Protected Wolf Population in Northwestern Minnesota. Wildlife monographs 1981, 80, 3–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mech, L.D. Leadership in Wolf, Canis lupus, packs. Canadian Fiels Naturalist 2000, 114(2), 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkei, R.; Újváry, D.; Bakos, V.; Faragó, T. Adult, Intensively Socialized Wolves Show Features of Attachment Behaviour to Their Handler. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |