Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Crystals Preparation

| Sample ID | Precursor concentration (M) | Drop volume (mL) | Heating time (min) | Heating temperature (°C) | Solvent | Substrate |

| D1 | 0.3 | 10 | 5 | 150 | DMSO | ITO/glass |

| D2 | 0.2 | 10 | 5 | 150 | DMSO | ITO/glass |

| D3 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 5 | 150 | DMSO | Gold |

| D4 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 1 | 150 | DMSO | Gold |

| D5 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 150 | DMSO | Gold |

| D6 | 0.3 | 10 | 5 | 90 | DMSO | ITO/glass |

| D7 | 0.3 | 10 | 5 | 120 | DMSO | ITO/glass |

| D8 | 0.3 | 10 | 5 | 150 | DMF | ITO/glass |

2.2. Crystals Characterization

2.2.1. SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy)

2.2.2. AFM (Atomic Force Microscopy)

2.2.3. Optical Microscopy Analysis

2.2.4. XRD (X-Ray Diffraction Spectroscopy)

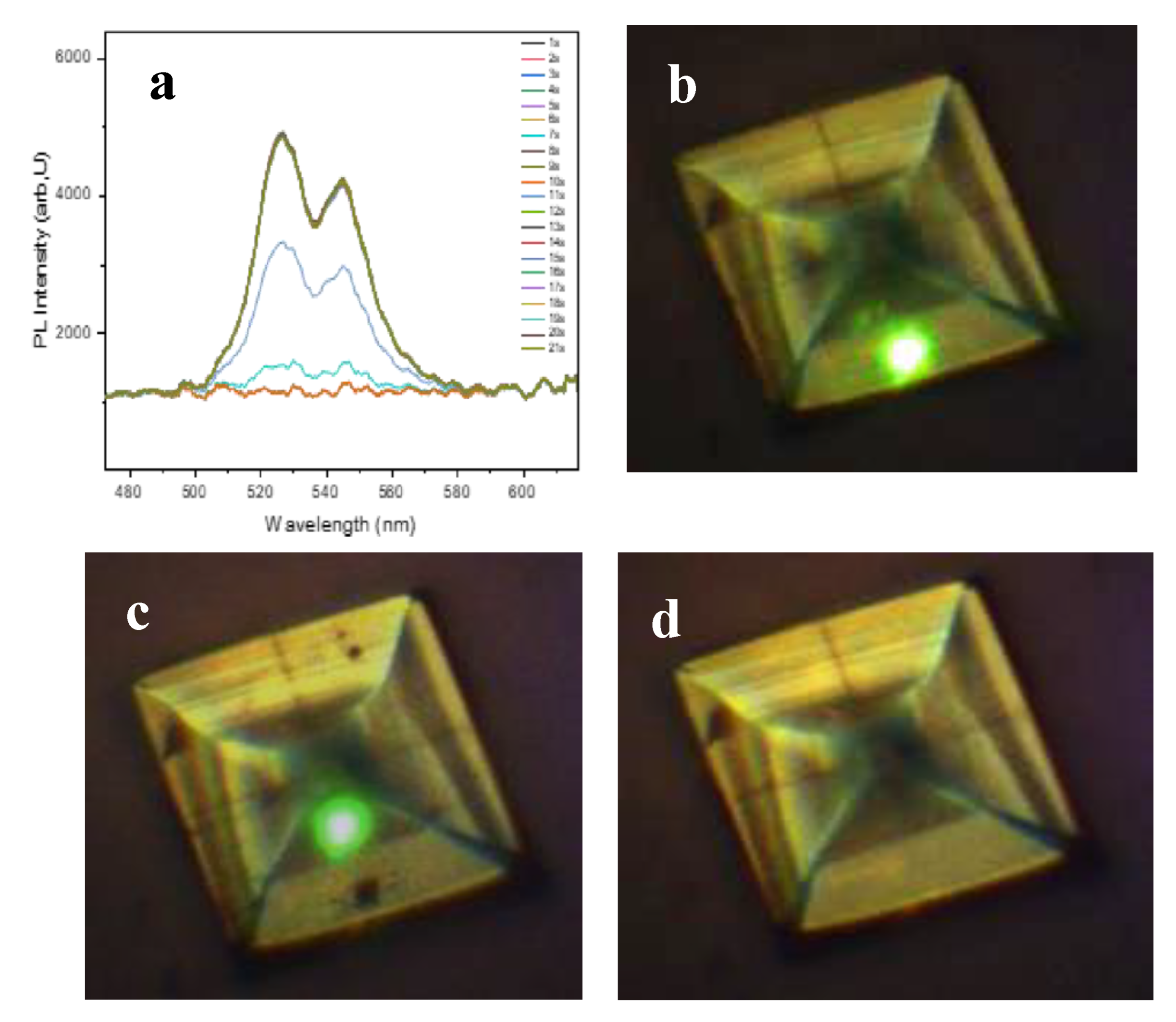

2.2.5. Confocal Microscopy

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| IGDORE | Institute for Globally Distributed Open Research and Education |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| NC | Nanocrystals |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| ITO | Indium-Tin oxide |

| USA | United States of America |

| RT | Room temperature |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| CCD | Charge-coupled device |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| GBL | γ-butyrolactone |

References

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Krieg, F.; Caputo, R.; Hendon, C.H.; Yang, R.X.; Walsh, A.; Kovalenko, M. V. Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut. Nano Letters 2015, 15, 3692–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Tan, S.; Li, D.; Meng, Q. The Stability of Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells: From Materials to Devices. Materials Futures 2023, 2, 32101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y. Recent Progress of All-Bromide Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Technology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cai, B.; Gu, Y.; Song, J.; Zeng, H. CsPbX3 Quantum Dots for Lighting and Displays: Roomerature Synthesis, Photoluminescence Superiorities, Underlying Origins and White Light-Emitting Diodes. Advanced Functional Materials 2016, 26, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Z.F.; Li, S.; Lei, L.Z.; Ji, H.F.; Wu, D.; Xu, T.T.; Tian, Y.T.; Li, X.J. High-Performance Perovskite Photodetectors Based on Solution-Processed All-Inorganic CsPbBr3 Thin Films. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2017, 5, 8355–8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, R.; Qi, W.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Hou, G. Encapsulation of Perovskite Solar Cells for Enhanced Stability : Structures, Materials and Characterization. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, T.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L. Perovskite CsPbBr3 Crystals: Growth and Applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2020, 8, 6326–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Mathews, N.; Lim, S.S.; Yantara, N.; Liu, X.; Sabba, D.; Grätzel, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Sum, T.C. Low-Temperature Solution-Processed Wavelength-Tunable Perovskites for Lasing; 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakita, Y.; Kedem, N.; Gupta, S.; Sadhanala, A.; Kalchenko, V.; Böhm, M.L.; Kulbak, M.; Friend, R.H.; Cahen, D.; Hodes, G. Low-Temperature Solution-Grown CsPbBr3 Single Crystals and Their Characterization. Crystal Growth and Design 2016, 16, 5717–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bealing, C.R.; Baumgardner, W.J.; Choi, J.J.; Hanrath, T.; Hennig, R.G. Predicting Nanocrystal Shape through Consideration of Surface-Ligand Interactions. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2118–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Xu, F.; Dong, Q.; Jia, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Ye, X. Facile, Low-Cost, and Large-Scale Synthesis of CsPbBr3 Nanorods at Room-Temperature with 86 % Photoluminescence Quantum Yield. Materials Research Bulletin 2020, 124, 110731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phys, J.A. Progress and Perspective on CsPbX 3 Nanocrystals for Light Emitting Diodes and Solar Cells Progress and Perspective on CsPbX 3 Nanocrystals for Light Emitting Diodes and Solar Cells. 2020, 050903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weerd, C.; Gregorkiewicz, T.; Gomez, L. All-Inorganic Perovskite Nanocrystals: Microscopy Insights in Structure and Optical Properties. Advanced Optical Materials 2018, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ni, C.; Yu, Y.; Attique, S.; Wei, S.; Ci, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, S. Design Principle of All-Inorganic Halide Perovskite-Related Nanocrystals. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2018, 6, 12484–12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiedh, K.; Dhanabalan, B.; Kutkan, S.; Lauciello, S.; Pasquale, L.; Toma, A.; Salerno, M.; Arciniegas, M.P.; Hassen, F.; Krahne, R. Surface-Dependent Properties and Tunable Photodetection of CsPbBr 3 Microcrystals Grown on Functional Substrates. 2021, 2101807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouloud, A.; Hassen, F.; Zaaboub, Z.; Salerno, M. Evaluating the Optoelectronic Properties of Individual CsPbBr3 Microcrystals by Electric AFM Techniques. Current Applied Physics 2024, 62, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Uddin, A.; Wang, H. ZnO Tetrapods: Synthesis and Applications in Solar Cells. Nanomaterials and Nanotechnology 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhu, Z.; Ray, S.; Azad, A.K.; Zhang, W.; He, M.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y. Optical and Dielectric Properties of ZnO Tetrapod Structures at Terahertz Frequencies. Applied Physics Letters 2006, 89, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, H.; Lee, Y.; Koh, W. kyu; Cho, E.; Kim, T.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Jeong, H.Y.; Jeong, S. Tailored Growth of Single-Crystalline InP Tetrapods. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, S.W.; Ahn, J.P.; Suh, Y.D.; Lee, J.S.; Lim, H.; Kim, D. Synthesis of Type II CdTe/CdSe Heterostructure Tetrapod Nanocrystals for PV Applications. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2009, 93, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Jung, M.; Ahn, J.; Woo, H.K.; Bang, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.Y.; Woo, H.Y.; Jeon, J.; Han, M.J.; et al. Post-Synthetic Oriented Attachment of CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystal Building Blocks: From First Principle Calculation to Experimental Demonstration of Size and Dimensionality (0D/1D/2D)† Sanghyun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.L.; Choo, Y.Y.; Huang, W.; Jiao, X.; Lu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Mcneill, C.R. Oriented Attachment as the Mechanism for Microstructure Evolution in Chloride-Derived Hybrid Perovskite Thin Films. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshadi, S.; Moghaddam, J.; Eskandarian, M. LaMer Diagram Approach to Study the Nucleation and Growth of Cu2O Nanoparticles Using Supersaturation Theory. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2014, 31, 2020–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Tran, T.; Truong, T.T.; Nguyen, T.M.; Nguyen, D.T.; Luu, Q.M.; Nguyen, H.H.; Tran, C.T.K.; Bui, H.T.T. Growth and Morphology Control of CH3NH3PbBr3 Crystals. Journal of Materials Science 2019, 54, 14797–14808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbrecht, K.G. The Physics of Snow Crystals. Reports on Progress in Physics 2005, 68, 855–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Yang, J.; Qu, S.; Lan, Z.; Sun, T.; Dong, Y.; Shang, Z.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Yan, L.; et al. Impact of Precursor Concentration on Perovskite Crystallization for Efficient Wide-Bandgap Solar Cells. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Riet, I.; Fang, H.H.; Adjokatse, S.; Kahmann, S.; Loi, M.A. Influence of Morphology on Photoluminescence Properties of Methylammonium Lead Tribromide Films. Journal of Luminescence 2020, 220, 117033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, H. Defect Suppression and Passivation for Perovskite Solar Cells: From the Birth to the Lifetime Operation. EnergyChem 2020, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Z.; Pang, S.; Yan, Y. Interaction Engineering in Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Perovskite Solar Cells Https://Doi.Org/10.1039/D0mh00745enteraction Engi. Materials Horizons;Materials Horizons 2020, 7((9) 7), 2208–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, J.C.; Schwartz, J.; Loo, Y.L. Influence of Solvent Coordination on Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Perovskite Formation. ACS Energy Letters 2018, 3, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharf, I.; Gramstad, T.; Makhija, R.; Onyszchuk, M. Synthesis and Vibrational Spectra of Some Lead(II) Halide Adducts with O-, S-, and N-Donor Atom Ligands. Canadian Journal of Chemistry 1976, 54, 3430–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diroll, B.T.; Zhou, H.; Schaller, R.D. Low-Temperature Absorption, Photoluminescence, and Lifetime of CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) Nanocrystals. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zheng, Z.; Fu, Q.; Guo, P.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Luo, W.; Tian, Y. Determination of Defect Levels in Melt-Grown All-Inorganic Perovskite CsPbBr3 Crystals by Thermally Stimulated Current Spectra. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2018, 122, 10309–10315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).