1. Introduction

Special Relativity, formulated by Albert Einstein in 1905, constitutes one of the cornerstones of modern physics. Its empirical success is undeniable, yet its physical interpretation—particularly concerning the nature of length contraction and time dilation—remains profoundly counter-intuitive, relying on the geometry of a spacetime devoid of physical substance.

A prevalent misconception holds that the Michelson–Morley experiment (1887) "proved the absence of the ether." This interpretation rests on a specific conception of the ether as a substance distinct from space. We propose a radical alternative: not the abandonment of any medium, but the identification of the medium with space itself. As we demonstrate in

Appendix A, the experiment imposes only a constraint on how material dimensions must deform with velocity relative to this space-medium. Throughout this work, we emphasize that the proposed space-medium hypothesis does not introduce any additional entity beyond space itself. The medium is not a substance embedded in space; rather, space is identified as the sole physical substrate, endowed with elastic properties. Relativistic effects are therefore interpreted not as kinematic illusions but as genuine dynamical deformations of this substrate.

This article is thus founded on two postulates:

- 1.

Space possesses elastic properties and is the medium for the propagation of light waves.

- 2.

Matter consists of standing waves within this medium.

We demonstrate that these postulates necessarily lead to the equations of special relativity, with an intuitive physical interpretation: relativistic effects are genuine physical deformations of the wave-like structures constituting matter. Finally, we outline how this same space-medium paradigm provides a physical foundation for gravitational phenomena, bridging the conceptual gap between the kinematic framework of Special Relativity and the theory of General Relativity.

2. The Michelson–Morley Misconception and Its Rectification

2.1. The True Implication of the Experiment

The Michelson–Morley experiment aimed to detect Earth’s motion relative to a hypothetical "luminiferous ether," a postulated ad-hoc component of the universe. Its null result—the absence of a detectable fringe shift—was historically interpreted as evidence against the existence of a propagation medium for light. This conclusion, however, is premature.

As the detailed analysis in

Appendix A shows, the null result imposes only the condition:

where

and

are the effective lengths of the longitudinal and transverse arms, respectively,

v is the velocity relative to the medium, and

c is the speed of light.

2.2. Physical Interpretation of the Condition

Equation (

1) reveals that the null result can be explained by an

anisotropic deformation of the interferometer’s arms. This deformation can manifest in several equivalent forms. The Lorentz–FitzGerald postulate, where only the longitudinal arm contracts, arises from independent considerations separate from the Michelson–Morley experiment.

The crucial insight is that the experiment measures only ratios of travel times; it consequently cannot discriminate between distinct physical interpretations yielding identical ratios. Einstein’s abandonment of a medium was one possible postulate, but not the only one.

3. Matter as Standing Waves in the Medium

3.1. Fundamental Postulate: The Wave–Particle Identity

This article does not discuss the complete paradigm describing particles of matter as coupled sets of standing waves in detail (further information can be found in [

10,

11]). For the present purpose, we will proceed from the principle that material particles are constituted of waves and that Space is the elastic medium supporting their propagation.

Consider a particle at rest in the medium as a stable interference pattern.

Mathematically, such a standing wave can be expressed as:

with quantization conditions:

It is crucial to distinguish between the wave amplitude and the associated energy density. While the amplitude of a spherical wave component decays as , the corresponding energy density scales as the square of the gradient, i.e. as . All energetic considerations in the following sections refer explicitly to energy density rather than wave amplitude.

3.2. Rest Energy as the Energy of the Fundamental Pattern

The rest energy

corresponds to the total energy of the undeformed wave pattern. In an elastic medium, the energy of a wave is proportional to the integral of the square of its spatial and temporal derivatives:

4. Absolute Velocity as a State of Deformation

In the present framework, velocity is not a purely kinematic parameter but a dynamical state of deformation of the standing-wave structure constituting matter. Motion relative to the space-medium induces anisotropic Doppler shifts across the wave components, resulting in a stable but deformed resonance pattern.

4.1. Doppler Effect on Matter Waves

When a wave structure moves with absolute velocity (relative to the medium), its components in the direction of motion experience a Doppler effect.

For a wave propagating longitudinally, the effective frequency becomes:

However, in this context we are not considering emitted waves—the particle constitutes the standing wave itself. Motion modifies the resonance conditions.

4.2. Contraction of Longitudinal Wavelengths

For a standing wave pattern to persist during motion, the wavelengths in the direction of motion must contract:

This contraction is not arbitrary; it follows from the necessity for the wave’s nodes and antinodes to remain coherent despite the motion.

4.3. Corresponding Increase in Frequencies and Energy

The contraction of wavelengths implies an increase in frequencies:

In an elastic medium, the energy of a wave is proportional to the square of its frequency. The increased frequency of the longitudinal components thus translates into an increase in total energy. More precisely, the energy density stored in the deformation of the medium is quadratic in the spatial and temporal derivatives of the displacement field. This quadratic dependence ensures that both kinetic and elastic contributions to the energy scale as the square of the local oscillation frequency.

4.4. Complete Calculation for a 3D Standing Wave

Consider a spherically symmetric 3D standing wave at rest. Under motion with velocity

along the

x-axis, the quantization conditions become:

with

and

.

To maintain coherence,

must increase:

The dispersion relation yields the new fundamental frequency:

The total energy

of the deformed wave pattern is obtained by integrating the energy density over the deformed volume (see

Appendix C):

4.5. Kinetic Energy as Surplus Deformation Energy

The additional energy due to motion is therefore:

Identifying

, we recover exactly the relativistic kinetic energy:

However, the interpretation is novel: K is the surplus energy required to Doppler-deform the standing wave pattern.

5. Fundamental Correspondence: Velocity ⇔ Deformation ⇔ Energy

5.1. The Bijective Relationship

Our model establishes a fundamental correspondence:

| Absolute Velocity |

⟺ |

Doppler Deformation |

| ⇓ |

|

⇓ |

| Contraction |

⟹ |

Energy |

Each absolute velocity corresponds to a specific state of wave-pattern deformation, characterized by:

A contraction of longitudinal wavelengths,

An increase in the corresponding frequencies,

An energy surplus proportional to the deformation.

5.2. Mechanical Interpretation of Inertia

This approach provides an intuitive mechanical interpretation of inertia:

- 1.

Rest state (): Undeformed wave pattern, minimal energy .

- 2.

Motion state (): Wave pattern deformed by the Doppler effect, energy .

- 3.

Acceleration: A force progressively modifies the pattern’s deformation, altering the frequencies of its constituent waves.

- 4.

Inertial resistance: Any modification of the wave frequencies involves an energy exchange with the environment.

6. Relativity as an Emergent Perceptual Phenomenon

6.1. Each Particle as a Deformed Observer

A profound consequence of our model is that each particle perceives the universe through the filter of its own deformation state. In other words: Each particle "perceives" the universe according to its own proper reference frame, using its deformed length and time scales to conduct all transactions with its environment. This mechanistic foundation explains relativity’s empirical successes: the prolonged lifetime of atmospheric muons, the extended travel distances of unstable particles in accelerators, the operation of GPS satellites requiring relativistic corrections, the relativistic Doppler shift in astrophysics, and the velocity-dependent cross-sections in particle physics. Each phenomenon finds a natural explanation as particles with different deformation states interact through their respective, self-consistent perceptual frameworks.

6.2. Emergence of the Lorentz Transformations

Consider two reference frames: S (the medium) and (a particle moving with velocity along x).

In

, the particle measures with its deformed instruments. For the speed of light to remain

c in all frames, the transformations between

S and

must necessarily be:

with

.

These transformations follow directly from length contraction: (), invariance of c () and the principle of reciprocity.

An intuitive deduction of time dilation is presented in

Appendix B.

7. Consistency with Established Physics

7.1. Verification of Standard Predictions

Our model reproduces exactly all predictions of special relativity:

- 1.

Length contraction: (real contraction of matter waves)

- 2.

Time dilation: (slowing of internal oscillations)

- 3.

Relativistic velocity addition:

- 4.

Mass–energy equivalence:

- 5.

Energy–momentum relation:

7.2. Ontological Difference in Interpretation

The fundamental difference from the standard interpretation lies in ontological status:

Standard Relativity: Spacetime is a geometric entity; effects are properties of this geometry.

Our Model: Space is a substantive physical medium; Time is the rate at which internal processes within particles execute: each has its own proper time that depends on its velocity relative to the medium.

7.3. Conclusion

The derivation thus far demonstrates that the space-medium hypothesis is not only consistent with Special Relativity but actively produces its mathematical framework from physical first principles. This successful reconstruction of kinematics invites a pivotal question: can the same foundational concepts—standing waves in an elastic space—account for the dynamics of gravitation, leading to General Relativity? We now show that the answer is affirmative.

8. Why Gravitation Appears as Spacetime Curvature

In the space-medium paradigm, gravitation does not originate from a fundamental force but from gradients in the elastic energy density of space. Matter modifies the local deformation state of the medium, and free motion corresponds to the path of extremal energy exchange.

In this context, a geodesic is not a primitive postulate but an emergent trajectory: it represents the path along which a wave-based particle preserves the coherence of its standing-wave structure while minimizing variations in deformation energy. The apparent curvature of spacetime thus encodes how elastic energy gradients constrain admissible wave trajectories.

General covariance arises as a necessary condition for describing deformation dynamics independently of the chosen coordinate system. The metric tensor acquires a direct physical meaning: it quantifies how local rulers and clocks—constructed from deformed wave patterns—respond to spatial variations in elastic energy density.

9. From Special to General Relativity: Extending the Paradigm

Having established that the space-medium paradigm naturally recovers the complete mathematical structure of Special Relativity, we now demonstrate its profound explanatory reach by extending the same principles to gravitation. This shows that the theory is not merely compatible with relativistic kinematics, but provides a unified mechanistic foundation for both pillars of modern physics.

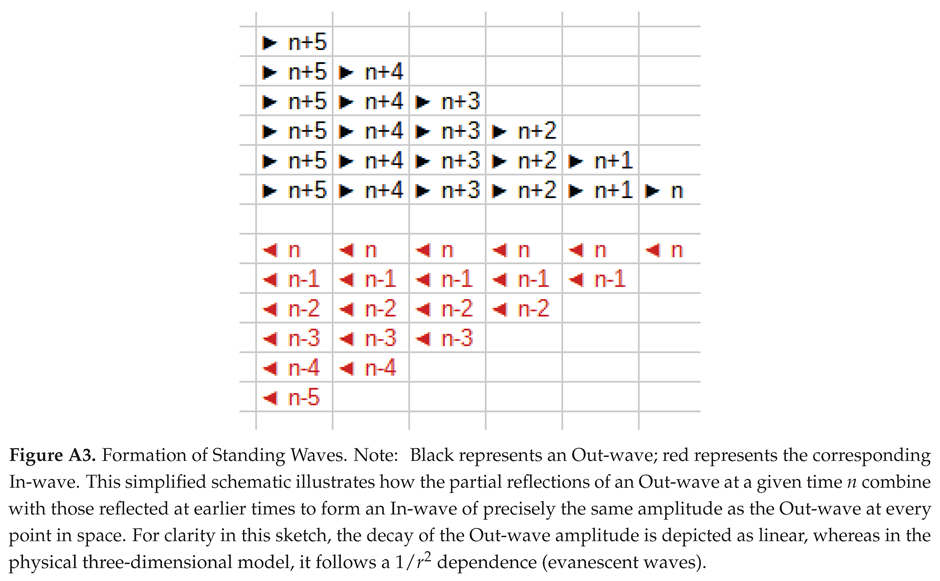

9.1. The Non-Local Wave Nature of Matter

To proceed, we must deepen our understanding of matter’s wave nature. A particle consists not of confined standing waves, but of evanescent standing waves (decaying as ) coupled at a geometric locus we call the "particle." This coupling zone establishes closed-loop energy circulation. These loops continuously lose energy through radiation—termed out-waves. Through gradual reflection, these out-waves generate corresponding in-waves. The complete set of in- and out-waves forms the standing wave pattern radiating from the particle. Thus, particles generate out-waves, while in-waves generate particles; the two are mutually dependent. This interdependence establishes matter’s non-local character and defines what we conventionally call "fields": these space-filling standing waves collectively constitute fields. Since these waves are vibrations throughout space, they represent genuine spatial deformations containing deformation energy.

9.2. Gravitational Fields as Spatial Deformations

Gravitational fields emerge from the collective in/out wave structure sourced by matter. Space around matter vibrates, storing deformation energy. We demonstrate that when masses approach, the reduction in total vibrational field energy equals their increase in kinetic energy.

Consider a scalar deformation field

with gravitational acceleration:

For a point mass

M at the origin, Poisson’s equation holds in the Newtonian limit:

with spherically symmetric solution (vanishing at infinity):

The inverse-square law emerges naturally from 3D geometry.

9.3. The Physical Meaning of Mass: Inertia and Gravity Unified

Within this framework, the concept of mass—traditionally considered an intrinsic property—acquires a concrete physical meaning as a measure of spatial deformation.

Mass as Deformation Energy: The mass-energy equivalence , derived from the wave model, reveals that the rest mass quantifies the total energy of the undeformed standing wave pattern. It is therefore a direct measure of the self-deformation of space required to sustain the particle.

Inertial-Gravitational Duality: This interpretation naturally resolves the long-standing puzzle of the equivalence between inertial mass () and gravitational mass ().

Inertial mass () measures the resistance to changing the particle’s state of deformation (i.e., its velocity). It is proportional to the stability of the wave pattern.

Gravitational mass () measures the particle’s capacity to produce a persistent deformation (the gravitational potential ) in the surrounding space-medium.

Both effects originate from the same physical substrate: the deformation of space by the wave structure of matter. Their quantitative equivalence () is therefore not a miraculous coincidence but a necessary consequence of a unified cause. The gravitational constant G then emerges as the universal coupling constant that relates the intensity of this deformation (mass) to the resulting gradient in the deformation field (gravity).

This provides a mechanistic foundation for the Equivalence Principle, the cornerstone of General Relativity.

9.4. Elastic Energy Interpretation

In linear elasticity theory, the energy density stored in a deformation field is quadratic in its gradient. Adopting this for space as an elastic medium:

where

is the medium’s elastic modulus. The total energy is:

Identifying and comparing with the standard gravitational field energy expression suggests . The negative sign indicates the attractive nature of gravity within this elastic analogy.

9.5. Interaction Energy Between Two Masses

For two masses

M separated by distance

D, the total field

yields energy:

The interaction term is computed via Green’s identity:

where

. Thus:

Setting

yields the correct Newtonian interaction:

9.6. Wave-Based Interpretation and Non-Locality

In the full wave-mechanical picture, the static potential

represents the time-averaged effect of oscillatory in/out waves. A more complete description replaces it with a radiating solution:

which satisfies the wave equation

. The time-averaged energy density

still scales as

, preserving the inverse-square law for energy flux.

This wave perspective naturally incorporates:

Non-locality: Waves extend throughout space, connecting distant masses.

Energy transfer: Kinetic energy gain equals field energy loss during approach.

Equivalence principle: Inertial and gravitational mass both measure wave deformation energy.

9.7. Connection to General Relativity

The elastic energy functional corresponds to the weak-field limit of the Einstein–Hilbert action, where the scalar deformation field u approximates the temporal component of the metric. In the fully relativistic regime, this scalar description generalizes to a tensorial deformation field , whose dynamics encode the nonlinear self-interactions of space’s elastic degrees of freedom. Full General Relativity emerges when:

- 1.

The deformation field becomes tensorial (metric ).

- 2.

Nonlinear self-interactions are included (higher-order terms in ).

- 3.

The constitutive relation incorporates Lorentz invariance.

Remarkably, the wave-medium paradigm suggests a physical interpretation: spacetime curvature measures the gradient of elastic deformation energy density. The Einstein field equations then express how matter (wave patterns) determines this deformation, which in turn guides matter’s motion—a perfect circular causality inherent to the in/out wave mechanism.

Note: A complete derivation from wave mechanics to full nonlinear General Relativity requires extensive treatment beyond this article’s scope. Our companion paper [

11] develops the new paradigm and the In/Out waves of matter.

10. Implications and New Perspectives

10.1. Conceptual Advantages of the New Paradigm

- 1.

Physically intuitive interpretation: Relativistic effects (length contraction, time dilation, mass-energy equivalence) are interpreted as direct, mechanical deformations of standing-wave structures, not as abstract properties of spacetime geometry.

- 2.

Velocity–Deformation Correspondence: A particle’s absolute velocity relative to the space-medium defines a unique, measurable state of Doppler deformation of its internal wave pattern.

- 3.

Kinetic Energy as Deformation Energy: The relativistic kinetic energy is directly identified as the energy surplus required to establish and maintain this velocity-dependent deformation state.

- 4.

Origin of Inertia: Inertial mass quantifies the resistance to changing this deformation state, providing a dynamical, wave-mechanical foundation for Newton’s law, .

- 5.

Foundation for the Equivalence Principle: The mechanistic interpretation of mass as a measure of spatial deformation provides a natural explanation for the equality of inertial and gravitational mass. Both inertia (resistance to changing a particle’s deformation state) and gravity (capacity to deform the surrounding space) originate from the same physical substrate—the interaction of standing-wave matter with the elastic space-medium. This makes the empirical equivalence a necessary consequence of a unified cause rather than a postulate.

- 6.

Natural Bridge to Quantum Mechanics: The ontological primacy of the wave description of matter creates a direct and necessary conceptual link to quantum theory.

- 7.

Paradox Resolution: Classical paradoxes, such as the twin paradox, resolve naturally from the self-consistency of physics within each particle’s deformed perceptual framework [

13].

- 8.

Falsifiability: Although the space-medium defines a preferred ontological frame, this frame remains dynamically inaccessible within the regimes explored by current experiments. As a result, all operational measurements performed by matter-based observers necessarily recover the relativistic symmetry structure.

10.2. Perspectives for Fundamental Physics

10.2.1. Manipulation of Inertia

If inertia results from wave–medium interaction, can it be modified?

Reduction of effective mass for propulsion

Materials with variable inertia

Exploration of very low-inertia states

10.2.2. Vacuum Energy

The medium, like any physical system, possesses a fundamental energy. Our model naturally predicts a non-zero vacuum energy.

11. Distinction from Neo-Lorentzian Ether Theories

11.1. Ontological Clarification: Space as the Sole Fundamental Entity

Having derived both Special and General Relativity from the postulates of a substantive elastic space, it is essential to distinguish our space-medium paradigm from classical and contemporary "neo-Lorentzian" ether theories (e.g., Cahill, 2005; Consoli, 2003). While these approaches also postulate a preferred frame and attempt to recover relativistic phenomenology, they typically:

Treat the ether as a distinct physical field or fluid permeating an otherwise passive space.

Require additional dynamical equations governing this ether field.

Often retain absolute simultaneity while explaining its empirical invisibility through complex dynamical or conspiratorial mechanisms.

Our approach adopts a radically minimalist and unified ontology: space itself is the only fundamental physical entity. It is not that waves propagate through space as through a container, but that space is the substantive, wave-bearing medium—its stable excitations constitute what we perceive as particles and fields. This eliminates the metaphysical oddity of "vibrating nothingness" inherent in the standard interpretation of Minkowski spacetime, while simultaneously avoiding the ontological proliferation of entities (space + ether) characteristic of ether-based theories.

The elastic properties we attribute to space are not additional qualities grafted onto it but are intrinsic to its physical nature as the sole constituent of reality. Consequently, our derivation of Lorentz transformations follows directly from the wave mechanics of deformable standing patterns within this single entity, without requiring ad-hoc contraction postulates or separate dynamical equations for a medium.

11.2. Comparison with Other Medium-Based Approaches

To further clarify our position, we contrast it with three broad categories of medium-based interpretations:

- 1.

Substantivalist Ether Theories: Posit a material ether filling Newtonian space (19th century). Our model rejects the dualism of container and content.

- 2.

Neo-Lorentzian/Dynamical Ether Theories: Introduce a preferred frame via a dynamical field (e.g., a condensate or quantum vacuum structure). Our model requires no such additional field; the preferred frame is simply (local) space itself.

- 3.

Geometric Ether Interpretations: Reinterpret the metric tensor of General Relativity as an ether state (e.g., Einstein’s later views). While closer in spirit, these often remain abstract. Our model provides a concrete mechanism—standing waves and their Doppler deformation—from which relativity emerges.

11.2.1. Connection with General Relativity

The wave nature of matter implies non-locality. While not discussed in detail here, a particle necessarily radiates energy but receives back the exact same amount (in the absence of acceleration). In our paradigm gravitational force is not of the same nature as other field interaction forces. It results from the energy density gradient in the spatial lattice induced by the presence of matter. This would account for the equivalence between gravitational and inertial mass, a longstanding puzzle in physics.

Our hypothesis aligns with and fully validates General Relativity, the only difference being its ontological interpretation.

11.2.2. Unification with Quantum Mechanics

Describing particles as waves in a single medium suggests a path toward unifying Relativity with Quantum Mechanics.

11.2.3. Space Expansion

A possible link between global gravitational potential energy and space expansion is discussed in our companion article [

12].

12. Proposed Experimental Research

- 1.

Search for residual anisotropies: Ultra-precise measurements to detect our motion relative to the medium.

- 2.

Experiments with strongly coupled systems: Search for anomalous inertial effects.

- 3.

Asymmetric collisions of ions with different masses: Detection of potential differences between H+/He+ and He+/H+ collisions, with one ion at rest in the laboratory.

- 4.

Measurements of c in strong fields: Detection of modifications to the medium’s properties.

Note on falsifiability: Since our model is empirically equivalent to standard relativity within experimentally validated regimes, its primary value lies in its unified explanatory power and conceptual implications for unification with quantum mechanics. The suggested experiments aim to explore potential limits of this empirical equivalence or to test extensions of the model to extreme regimes (strong fields, quantum couplings).

13. Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the hypothesis "space is the unique physical constituent of the universe and matter consists of standing waves within this medium" leads mathematically to the equations of special relativity. Our model thus establishes a complete empirical equivalence with Einstein’s theory: all quantitative predictions coincide.

The difference is purely ontological and interpretive. Whereas standard relativity describes a geometric spacetime empty of physical substance, our model identifies space as a substantive entity whose mechanical deformations naturally explain inertia, kinetic energy, and relativistic effects. Crucially, by interpreting mass as a measure of this deformation, the model unifies the concepts of inertial and gravitational mass, demystifying the Equivalence Principle—the cornerstone of General Relativity—as a necessary consequence rather than a foundational postulate.

Furthermore, by identifying gravitational fields with spatial deformation gradients and their energy, we provide a physical pathway from the wave-mechanical principles underlying Special Relativity to the framework of General Relativity. This interpretation not only offers a more intuitive picture but also opens new perspectives for unifying quantum mechanics and relativity, since the wave nature of matter becomes fundamental rather than emergent. The space-medium paradigm thus represents a physical reinterpretation of the mathematical successes of relativity, proposing a unique mechanistic foundation from which to reconstruct physics.

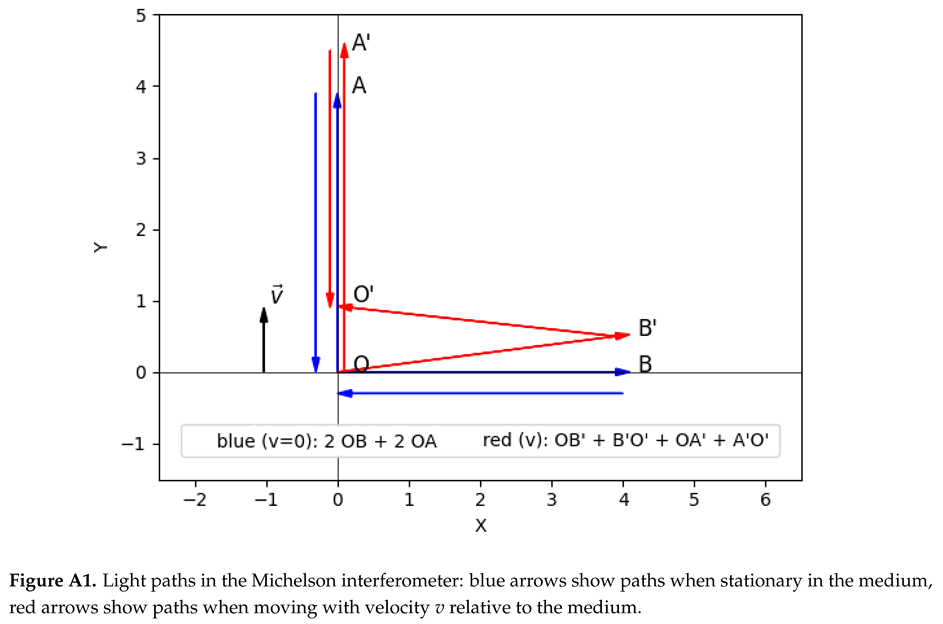

Appendix A. Complete Geometric Derivation of the Michelson–Morley Constraint

This appendix presents the complete derivation of the deformation constraint using a geometric analysis.

Appendix A.1. Experimental Setup and Light Path Analysis

Consider the interferometer moving with velocity

v relative to the medium. Let

be the proper length of each arm when at rest in the medium (

). When moving, the arms deform to lengths:

where

and

are absolute deformations that depend on the velocity

v relative to the medium. These factors describe how the physical length of the arms changes due to motion through the medium. The goal of our derivation is to find the relationship between

and

imposed by the Michelson–Morley null result.

Appendix A.2. Transverse Arm Analysis Using Figure A1

Distance traveled by light in the medium:

Travel time:

Let us consider the travel durations between the points:

Appendix A.3. Longitudinal Arm Analysis Using Figure A1

For the longitudinal arm (parallel to motion), the light path in the medium frame is:

Forward trip (from O to A’):

Return trip (from A’ to O’):

Appendix A.4. Null Result Condition

The experimental null result requires equal round-trip times:

This completes the derivation of Equation (

1).

Table A1.

Complete analysis of light paths in the Michelson–Morley experiment (medium frame)

Table A1.

Complete analysis of light paths in the Michelson–Morley experiment (medium frame)

| Parameter |

Longitudinal Arm |

Transverse Arm |

| Arm length in medium frame |

|

|

| Round-trip time |

|

|

| Null result condition |

|

| Lorentz–FitzGerald postulate |

|

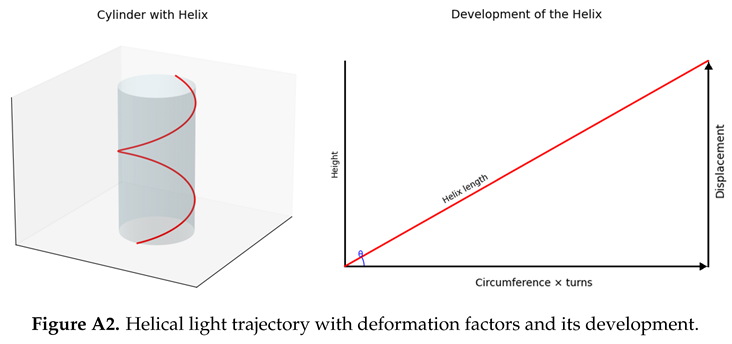

Appendix B. Generalized Derivation of Time Dilation from Helical Paths with Deformation Factors

Appendix B.1. Particle as a Confined Light Trajectory with Deformation

Consider a fundamental particle as a confined light-like trajectory. When at rest, the trajectory forms closed loops of proper radius . When moving with velocity v relative to the medium, the particle deforms according to the factors and .

The helical trajectory now has the following:

Appendix B.2. Generalized Helical Path Analysis

Developing the deformed helix gives a right triangle with:

Hypotenuse: total light path

Vertical leg: translation path

Horizontal leg: internal loop path

Applying Pythagoras’ theorem:

The function

accounts for how the deformation affects the internal path length. For

and

, we recover the standard result:

The proper time of a moving particle slows down relative to a particle at rest with respect to the medium.

Note: As shown, a particle’s velocity relative to the medium implies an increased frequency of its standing waves in the direction of motion, resulting in a contraction of their wavelengths, which geometrically contracts matter longitudinally. However, this contraction does not alter the speed of light in the medium. Thus, the reasoning above is not invalidated by length contraction.

Each particle possesses a Proper Time, dependent on its velocity: it represents the internal cadence of its processes, the number of cycles performed relative to the number of cycles executed by other particles in the universe. The elliptical trajectory perfectly illustrates the phenomenon of time slowing with absolute velocity: the more the waves’ path is devoted to translation, the less is devoted to executing closed trajectories, and the more their angular velocities are reduced: its proper time slows. This impacts how the particle ’perceives’ the rest of the universe and how it will interact with it, depending on whether its cadence and phase are aligned or not with those of other particles or the fields they generate.

Appendix C. Dynamical Foundations of Inertia and Kinetic Energy in the Wave-Medium Paradigm

Appendix C.1. Stationary and Quasi-Stationary States of a Particle-Field System

Within the proposed paradigm, an elementary particle is not a localized point object but a self-sustaining, coherent structure defined by the interference of its constituent waves. At absolute rest relative to the space-medium, this structure consists of a three-dimensional lattice of perfectly standing waves formed by the equilibrium between outgoing waves (OUT) radiated from a geometric locus and incoming waves (IN) resulting from their gradual reflection by the lattice. This standing-wave lattice and the particle locus are mutually dependent: the particle exists as a node of coherence within the lattice, while the lattice itself is sustained by the particle’s activity. The rest energy corresponds to the total energy of this self-consistent, stationary configuration.

Appendix C.2. Uniform Motion as a Deformed Quasi-Stationary State

When a particle travels at a uniform speed

relative to the medium, the symmetry of its standing wave pattern is broken. The Doppler effect, acting on the waves relative to the stationary lattice of the medium, alters their frequencies. Crucially, the frequency of the waves emitted forward (the Out waves) becomes higher than that of the In waves being progressively reflected back from that same direction. This occurs because the effective points of partial reflection in the medium ’recede’ ahead of the advancing Out waves—a situation directly analogous to the moving mirror in the longitudinal arm of the Michelson interferometer (see Figure A1 in

Appendix A).

Consequently, the interference pattern ceases to be perfectly stationary and becomes quasi-stationary, which inherently involves a net transport of energy. Thus, the particle’s energy, together with that of its associated field, is progressively transmitted from the rear to the front of the moving structure. This process sustains a stable deformed shape that propagates en bloc with the velocity . This deformed geometry is then characterized by:

- 1.

A contraction of spatial periodicity along the direction of motion by the Lorentz factor .

- 2.

A persistent, unidirectional energy flow along the quasi-stationary wave structure in the direction of motion. This flow represents the kinetic energy of the particle-field system.

Thus, a state of uniform velocity is not a kinematic label but a specific, stable dynamical state of deformation of the coupled particle-field entity.

Appendix C.3. Acceleration as a Dynamical Reconfiguration Process

Applying a force to the particle (e.g., via collision or field interaction) aims to change its velocity, i.e., to alter its state of wave-pattern deformation. This process is not instantaneous. The adjustment from one quasi-stationary configuration to another requires a finite reconfiguration wave to propagate through the entire extended field at the speed of light c. During this transient period, energy and momentum are exchanged between the external agent and the field.

Inertia is identified as the resistance to this reconfiguration. It quantifies how much work the external agent must perform against the elastic restoring forces of the lattice to establish the new deformation pattern corresponding to the target velocity. The resistance originates from the fact that all wave components, extending non-locally throughout space, must be coherently rephrased.

Appendix C.4. Kinetic Energy as the Directed Momentum Content of the Deformed Field

In this framework, the relativistic kinetic energy K is not an independent quantity but is directly tied to the momentum of the moving system. The total linear momentum of the particle-field complex is defined as the integrated directed energy flow within the quasi-stationary wave pattern. For motion along the x-axis, this is proportional to the surplus energy carried by the longitudinal wave components.

From the properties of the deformed state, it follows that the total energy

E and momentum

p of a particle moving with speed

v satisfy:

where

. The kinetic energy is then the surplus energy above the rest state:

Appendix C.5. Collisions: Exchange of Deformation States

A collision between two particles is fundamentally an interaction and exchange between their respective deformed wave fields. Consider a head-on elastic collision. During the interaction, the opposing energy flows and spatial deformations of the two fields interact. The fields transiently merge and reconfigure, mediating the transfer of directed energy-momentum. The quantity conserved and exchanged is precisely the field momentum , and the convertible energy is the kinetic energy. This process provides a mechanistic explanation for the relativistic conservation laws, which emerge as constraints on the possible reconfigurations of coupled wave patterns.

Appendix C.6. Synthesis and Interpretation

This model unifies several concepts:

Velocity is a specific deformation state of a particle’s wave field.

Inertial Mass () measures the stability of the rest-state wave pattern and the scale of energy required for its deformation.

Force is not an action-at-a-distance, but the rate of transfer of energy-momentum required to drive the reconfiguration wave through the field. This transfer occurs via the direct superposition and interaction of the wave fields of the particles involved.

Kinetic Energy is the manifest, directed energy-momentum content of the deformed field, available for transfer in interactions.

Consequently, the formalism of Special Relativity—Lorentz transformations, time dilation, length contraction, and the mass-energy-momentum relations—is recovered not as postulates of spacetime geometry, but as the effective, emergent mathematics describing the deformation dynamics of coherent wave structures in an elastic space-medium. The inertial resistance described by Newton’s Second Law finds its physical origin in the finite propagation speed of reconfiguration signals through the non-local wave field that constitutes matter.

References

- Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Annalen der Physik 1905, 17(10), 891–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, A. A.; Morley, E. W. On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether. American Journal of Science 1887, 34, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, H. A. Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity smaller than that of light. Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences 1904, 6, 809–831. [Google Scholar]

- de Broglie, L. Recherches sur la théorie des quanta. Annales de Physique 1924, 10(3), 22–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, R. T. The Michelson and Morley 1887 Experiment and the Discovery of Absolute Motion. Progress in Physics 2005, 3, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Haisch, B.; Rueda, A.; Puthoff, H. E. Inertia as a zero-point-field Lorentz force. Physical Review A 1994, 49(2), 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consoli, M.; Płoszajczak, M. Ether and Relativity. Foundations of Physics 2009, 39(7), 868–875. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, C.; Liberati, S.; Visser, M. Analogue Gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 2011, 14(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volovik, G. E. The Universe in a Helium Droplet; Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Furne Gouveia, G.

The Elastic Space Paradigm: A Wave-Based Reconstruction of Physics

. In Foundations, Predictions, and Testable Consequences; Preprints, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G.

The IN/OUT Wave Mechanism: A Non-Local Foundation for Quantum Behavior and the Double-Slit Experiment

. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G.

The Role of Energy Density Diffusion in Galactic Dynamics and Cosmic Expansion: A Unified Theory for MOND and Dark Energy

. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G.

The Twin Paradox and the Symmetry Problem in Relativity: A Century of Debates and a New Resolution

. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |