Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

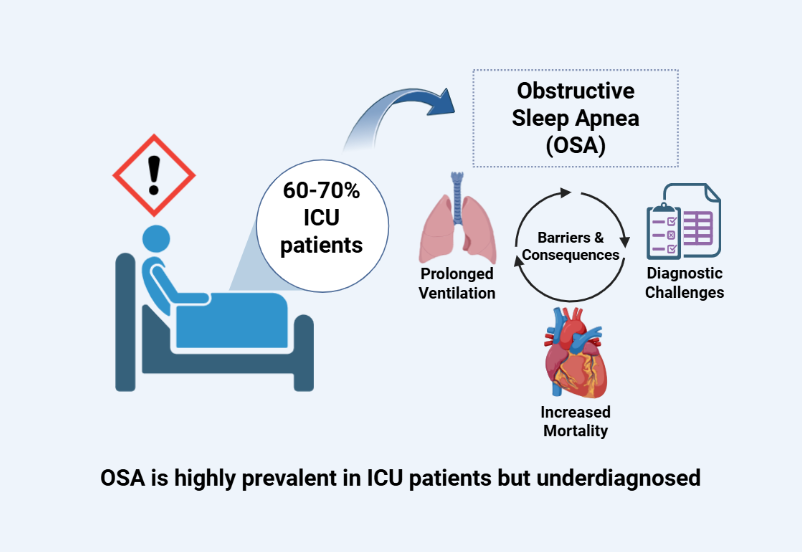

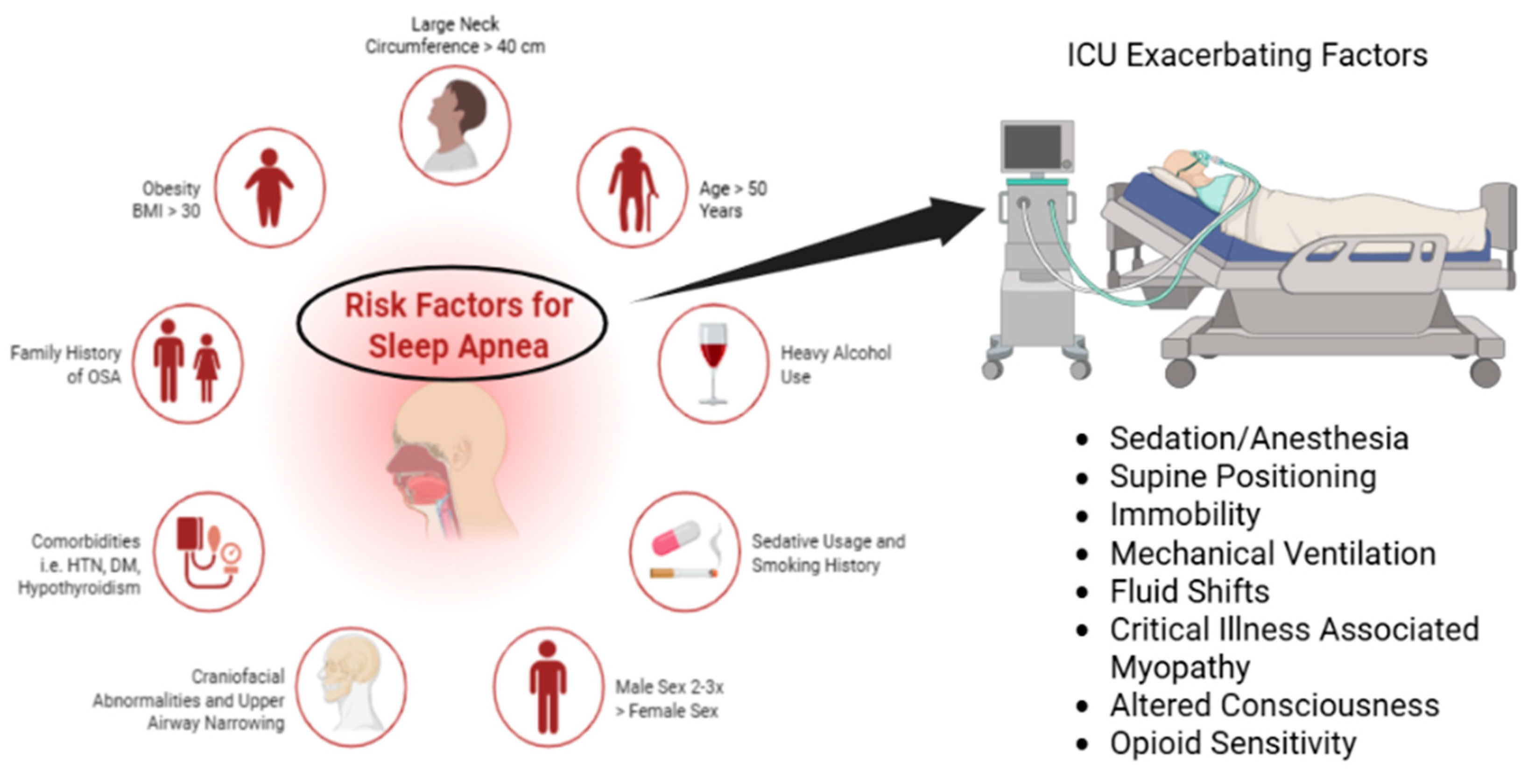

Epidemiology and Prevalence of OSA in ICU Settings

2. Results

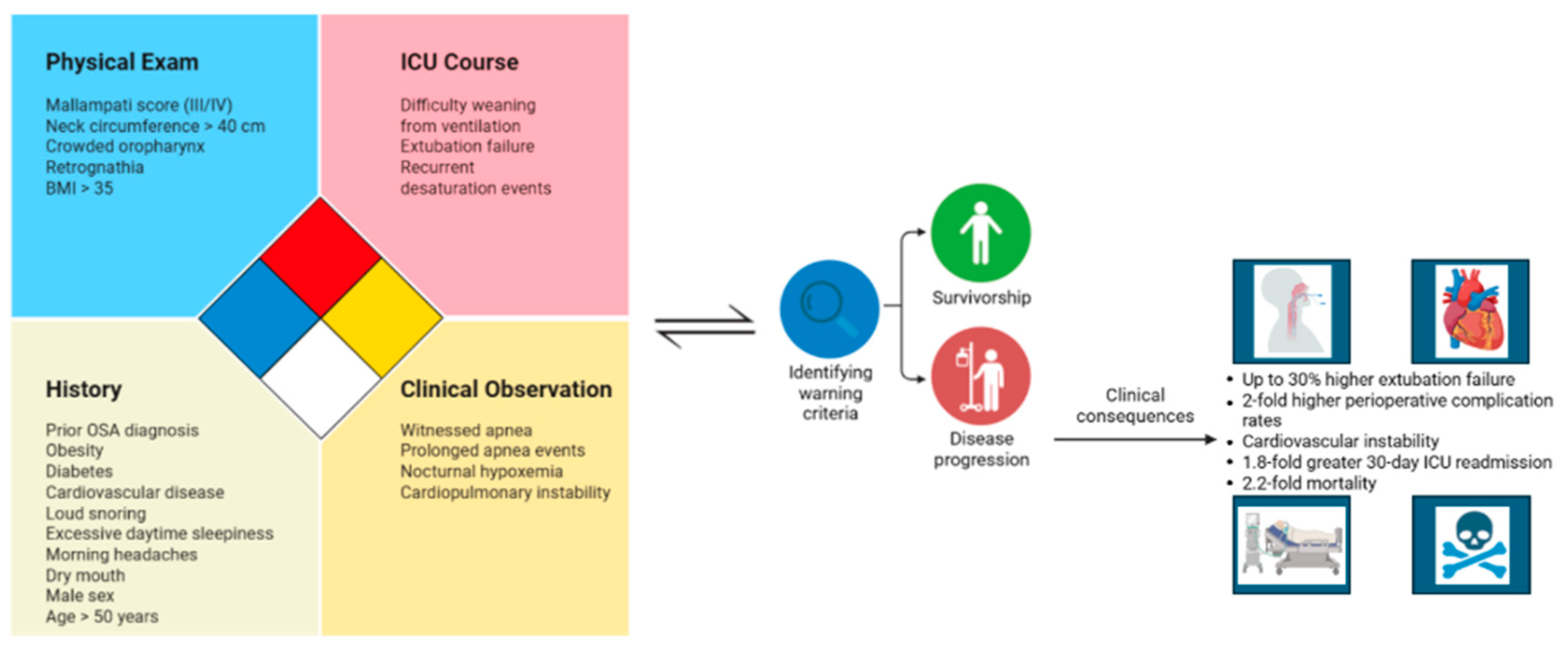

Clinical Implications of Unrecognized OSA in the ICU

3. Discussion

3.1. Diagnostic Challenges in the ICU

3.2. Current Approaches to Screening, Diagnosis, and Management

3.3. Future Research Directions

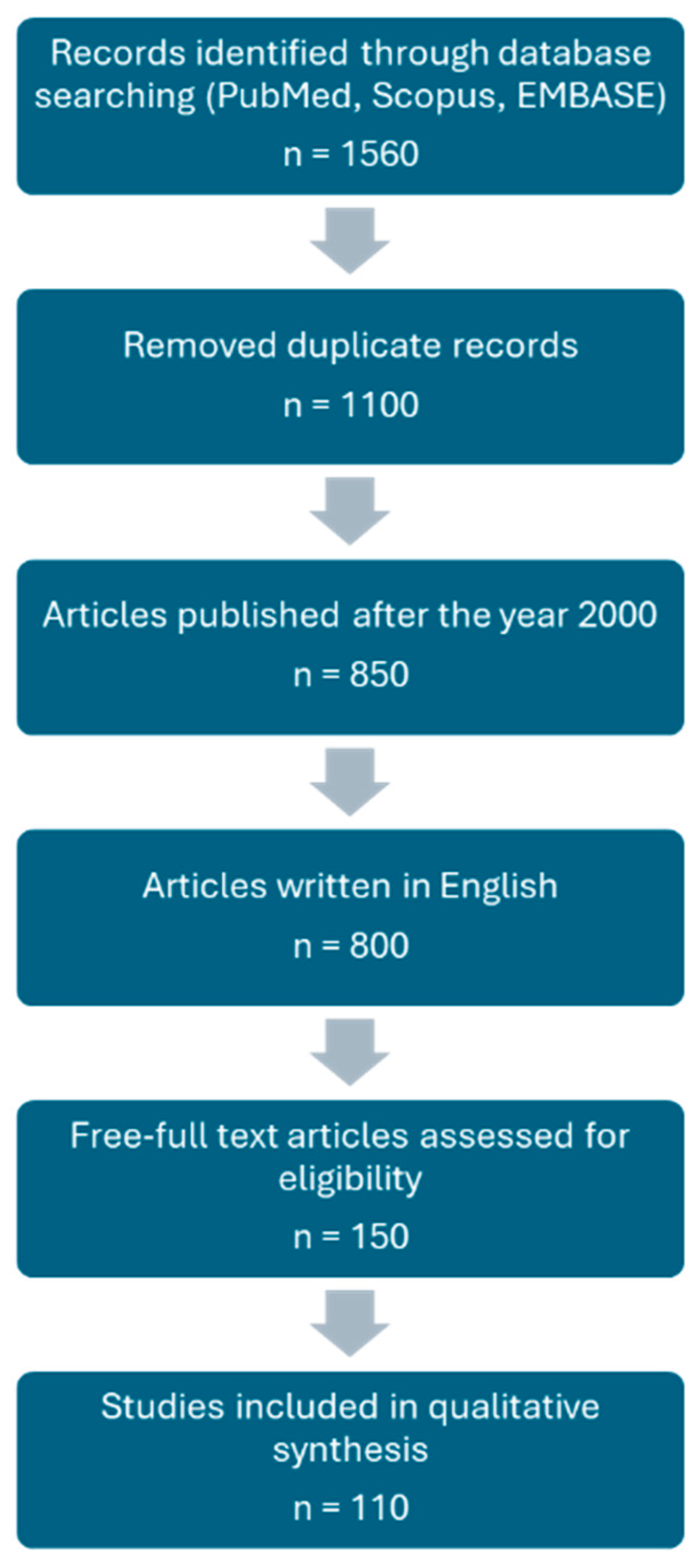

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSA | Obstructive sleep apnea |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| PSG | Polysomnography methods |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| PADIS | Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption |

| ODI | Oxygen desaturation index |

| STOP-BANG | Snoring, tiredness, observed apneas, high blood pressure, BMI > 35, age > 50, neck circumference > 40 cm, male gender |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ML | Machine learning |

| EHR | Electronic heath record |

| V/Q | Ventilation-perfusion |

| EPAP | Expiratory positive airway pressure |

| HST | Home sleep testing |

References

- Chronic intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea: A narrative review from pathophysiological pathways to a precision clinical approach | Sleep and Breathing. (2020). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11325-019-01967-4.

- McNicholas, W. T.; Korkalainen, H. Translation of obstructive sleep apnea pathophysiology and phenotypes to personalized treatment: A narrative review. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, W. T.; Pevernagie, D. Obstructive sleep apnea: Transition from pathophysiology to an integrative disease model. Journal of Sleep Research 2022, 31(4), e13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenauer, P. K.; Stefan, M. S.; Johnson, K. G.; Priya, A.; Pekow, P. S.; Rothberg, M. B. Prevalence, Treatment, and Outcomes Associated With OSA Among Patients Hospitalized With Pneumonia. CHEST 2014, 145(5), 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, Chun-Ying; Wang, An-Yi; Chang, Kai-Mei; et al. Dynamic Prevalence of Sleep Disturbance among Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Units and after Hospitalisation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 2023, 75, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasu, Tajender S., Ritu Grewal, and Karl Doghramji. “Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Perioperative Complications: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 8, no. 2. (2012). 199–207. [CrossRef]

- P22 Undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea in the perioperative period: Prevalence and management | BMJ Open Respiratory Research. 2022. Available online: https://bmjopenrespres.bmj.com/content/10/Suppl_1/A22.2.

- Benjafield, A. V.; Ayas, N. T.; Eastwood, P. R.; Heinzer, R.; Ip, M. S. M.; Morrell, M. J.; Nunez, C. M.; Patel, S. R.; Penzel, T.; Pépin, J.-L.; Peppard, P. E.; Sinha, S.; Tufik, S.; Valentine, K.; Malhotra, A. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: A literature-based analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine 2019, 7(8), 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppard, P. E.; Young, T.; Barnet, J. H.; Palta, M.; Hagen, E. W.; Hla, K. M. Increased Prevalence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Adults. American Journal of Epidemiology 2013, 177(9), 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Baisheng; Lei, Mingxing; Zhang, Jiaqi; Kang, Hongjun; Liu, Hui; Zhou, Feihu. Acute Lung Injury Caused by Sepsis: How Does It Happen? Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational investigations of obstructive sleep apnea and health outcomes | Sleep and Breathing. (2022). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11325-021-02384-2.

- Slowik, Jennifer M.; Sankari, Abdulghani; Collen, Jacob F. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, 2025; Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459252/.

- Grimm, Jessica. Sleep Deprivation in the Intensive Care Patient. Critical Care Nurse 2020, 40(no. 2), e16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiraja, R.; Quan, S. F. Long-term All-Cause Mortality Risk in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Using Hypopneas Defined by a ≥3 Percent Oxygen Desaturation or Arousal. Southwest Journal of Pulmonary & Critical Care 2021, 23, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyanto, T. I.; Kurniawan, A. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine 2021, 82, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchasson, Laura; Rault, Christophe; Le Pape, Sylvain; et al. Impact of Sleep Disturbances on Outcomes in Intensive Care Units. Critical Care 2024, 28(no. 1), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Xu, H.; Chang, Y.; Feng, B.; Wang, Q.; Li, W. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on inpatient outcomes of COVID-19: A propensity-score matching analysis of the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample. (2020). Frontiers in Medicine 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Lindsay; Garg, Shikha; O’Halloran, Alissa; et al. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-Hospital Mortality Among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the US Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 72(no. 9.), e206–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C. A.; Sonnad, S. S.; Garetz, S. L.; Helman, J. I.; Chervin, R. D. Quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review of the literature. Sleep Medicine 2001, 2(6), 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, D. J. Phenotypic approaches to obstructive sleep apnoea – New pathways for targeted therapy. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2018, 37, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randerath, W.; de Lange, J.; Hedner, J.; Ho, J. P. T. F.; Marklund, M.; Schiza, S.; Steier, J.; Verbraecken, J. Current and novel treatment options for obstructive sleep apnoea. ERJ Open Research 2022, 8(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, X. Spatiotemporal Trends in the Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Across China: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis Incorporating Geographic and Demographic Stratification (2000-2024). Nature and Science of Sleep 2025, 17, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Yuanfang; Loftus, Tyler J.; Guan, Ziyuan; et al. Computable Phenotypes to Characterize Changing Patient Brain Dysfunction in the Intensive Care Unit; arXiv, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, Selin; Macit Aydın, Eda; Nazlıel, Bijen; et al. Evaluation of Delirium Risk Factors in Intensive Care Patients. Turkish Journal of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, ahead of print, Turkish Journal of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Kyle C.; Serpa-Neto, Ary; Hurford, Rod; et al. Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in the Intensive Care Unit: Incidence, Patient Characteristics, Timing, Trajectory, Treatment, and Associated Outcomes. A Multicenter, Observational Study. Intensive Care Medicine 2023, 49(no. 9.), 1079–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayenew; Temesgen; Gete, Menberu; Gedfew, Mihretie; et al. Prevalence of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome among Intensive Care Unit-Survivors and Its Association with Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS One 2025, 20(no. 5), e0323311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, Hannah; Wagner, Jason; Herlim, Maximilian; Chong, David; Kramer, Andrew; Halpern, Scott D. ICU Occupancy and Mechanical Ventilator Use in the United States. Critical Care Medicine 2013, 41(no. 12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, John W.; Skrobik, Yoanna; Gélinas, Céline; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine 2018, 46(no. 9), e825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metrics of sleep apnea severity: Beyond the apnea-hypopnea index | SLEEP | Oxford Academic. 2021. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/44/7/zsab030/6164937.

- Ralls, Frank; Cutchen, Lisa. A Contemporary Review of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 2019, 25(no. 6), 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, Colin; Wong, Jean; Ryan, Clodagh M.; et al. Prevalence of Undiagnosed Obstructive Sleep Apnea Among Patients Hospitalized for Cardiovascular Disease and Associated In-Hospital Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9(no. 4.), 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleep monitoring by actigraphy in short-stay ICU patients | Critical Care | Full Text. 2012. Available online: https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/cc10927.

- Bucklin, Abigail A.; Ganglberger, Wolfgang; Quadri, Syed A.; et al. High Prevalence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing in the Intensive Care Unit — a Cross-Sectional Study. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2023, 27(no. 3), 1013–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucklin, A. A.; Ganglberger, W.; Quadri, S. A.; Tesh, R. A.; Adra, N.; Da Silva Cardoso, M.; Leone, M. J.; Krishnamurthy, P. V.; Hemmige, A.; Rajan, S.; Panneerselvam, E.; Paixao, L.; Higgins, J.; Ayub, M. A.; Shao, Y.-P.; Ye, E. M.; Coughlin, B.; Sun, H.; Cash, S. S.; Westover, M. B. High prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the intensive care unit—A cross-sectional study. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2023, 27(3), 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI).” Sleep Foundation, October 28, 2021. Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-apnea/ahi.

- Franca; Aires, Suelene; Toufen, Carlos; Hovnanian, André Luiz D.; et al. The Epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Failure in Hospitalized Patients: A Brazilian Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Critical Care 2011, 26(no. 3), 330.e1–330.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, Yasser; Jaschinski, Ulrich; Wittebole, Xavier; et al. Sepsis in Intensive Care Unit Patients: Worldwide Data From the Intensive Care over Nations Audit. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2018, 5(no. 12), ofy313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prediction of Extubation Failure in Intensive Care Units. Frontiers in Medicine 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, Mario; Willes, Leslee; Prillaman, Barbara A.; Quan, Stuart F.; Sharma, Sunil. Undiagnosed OSA May Significantly Affect Outcomes in Adults Admitted for COPD in an Inner-City Hospital. CHEST 2020, 158(no. 3), 1198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Jiali; Zhou, Ling; Tian, Weiwei; et al. Deep Insight into Cytokine Storm: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10(no. 1), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung; Hinson, Pak-Hin; Ye, Zi-Wei; Lee, Tak-Wang Terence; Chen, Honglin; Chan, Chi-Ping; Jin, Dong-Yan. PB1-F2 Protein of Highly Pathogenic Influenza A (H7N9) Virus Selectively Suppresses RNA-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation through Inhibition of MAVS-NLRP3 Interaction. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2020, 108(no. 5), 1655–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury, R. C.; Strollo, P. J. Clinical manifestations of sleep apnea. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2015, 7(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Terry; Skatrud, James; Peppard, Paul E. Risk Factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. JAMA 2004, 291(no. 16), 2013–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigating the Relationship between Obstructive Sleep Apnoea, Inflammation and Cardio-Metabolic Diseases. 2023. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/24/7/6807.

- Franklin, Karl A.; Lindberg, Eva. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is a Common Disorder in the Population—a Review on the Epidemiology of Sleep Apnea. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2015, 7(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsky, Andrea N.; Vakulin, Andrew; Coetzer, Ching Li Chai; McEvoy, R. D.; Adams, Robert J.; Kaambwa, Billingsley. Economic Evaluation of Diagnostic Sleep Studies for Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: A Systematic Review Protocol. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannella, Giannicola; Pace, Annalisa; Bellizzi, Mario Giuseppe; et al. The Global Burden of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Diagnostics 2025, 15(no. 9), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwelius, Lotti; Wilhelms, Susanne; Sjöberg, Folke. Is Comorbidity Alone Responsible for Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life among Critical Care Survivors? A Purpose-Specific Review. Critical Care 2024, 28, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The overlap of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea in hospitalizations for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Venessa L.; Sankari, Abdulghani; Sharma, Sandeep. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, 2025; Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482178/.

- Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome | Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-023-01496-3.

- Obstructive sleep apnea: Personalizing CPAP alternative therapies to individual physiology: Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine: Vol 16 , No 8—Get Access. (2022). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17476348.2022.2112669.

- Liu, K.; Geng, S.; Shen, P.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, P.; Liu, W. Development and application of a machine learning-based predictive model for obstructive sleep apnea screening. Frontiers in Big Data 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaw, R.; Chung, F.; Pasupuleti, V.; Mehta, J.; Gay, P. C.; Hernandez, A. V. Meta-analysis of the association between obstructive sleep apnoea and postoperative outcome. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2012, 109(6), 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Bustamante, A.; Bartels, K.; Clavijo, C.; Scott, B. K.; Kacmar, R.; Bullard, K.; Moss, A. F. D.; Henderson, W.; Juarez-Colunga, E.; Jameson, L. Preoperatively Screened Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is Associated With Worse Postoperative Outcomes Than Previously Diagnosed Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2017, 125(2), 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.; Yegneswaran, B.; Liao, P.; Chung, S. A.; Vairavanathan, S.; Islam, S.; Khajehdehi, A.; Shapiro, C. M. STOP Questionnaire: A Tool to Screen Patients for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology 2008, 108(5), 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Liao, P.; Kobah, S.; Wijeysundera, D. N.; Shapiro, C.; Chung, F. Proportion of surgical patients with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2013, 110(4), 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Guo, R.; Hao, W.; Gong, W.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, W.; Ai, H.; Que, B.; Hu, D.; Ma, C.; Ma, X.; Somers, V. K.; Nie, S. Association of obstructive sleep apnoea with cardiovascular events in women and men with acute coronary syndrome. European Respiratory Journal 2023, 61(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potential underdiagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea in the cardiology outpatient setting | Heart. 2015. Available online: https://heart.bmj.com/content/101/16/1288.

- Interactions of Obstructive Sleep Apnea With the Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Disease, Part 1: JACC State-of-the-Art Review | JACC. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Cardiometabolic Risk in Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome | JACC. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, U.; Rajagopala, S.; Kumar, A.; Ramachandran, P.; Devereaux, P. J.; D’Souza, G. A. Undiagnosed Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Postoperative Outcomes: A Prospective Observational Study. Respiration 2017, 94(1), 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhuang, J.; Zheng, H.; Yao, L.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Fan, C. A Machine Learning Prediction Model of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Based on Systematically Evaluated Common Clinical Biochemical Indicators. Nature and Science of Sleep 2024, 16, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic accuracy of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults in different clinical cohorts: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Sleep and Breathing. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Spurr, Kathy F.; Graven, Michael A.; Gilbert, Robert W. Prevalence of Unspecified Sleep Apnea and the Use of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Hospitalized Patients, 2004 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Sleep and Breathing 2008, 12(no. 3), 229–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best Clinical Practices for the Sleep Center Adjustment of Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NPPV) in Stable Chronic Alveolar Hypoventilation Syndromes. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2010, 6(no. 5), 491–509. [CrossRef]

- Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 2009. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/co-anesthesiology/abstract/2009/06000/screening_for_obstructive_sleep_apnea_before.18.aspx.

- Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with cardiovascular diseases cannot be detected by ESS, STOP-BANG, and Berlin questionnaires | Clinical Research in Cardiology. 2018. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00392-018-1282-7.

- Wolfe, R. M.; Pomerantz, J.; Miller, D. E.; Weiss-Coleman, R.; Solomonides, T. Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Preoperative Screening and Postoperative Care. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2016, 29(2), 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschbach, Erin; Wang, Jing. Sleep and Critical Illness: A Review. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10, 1199685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, J. W.; Evans, J. L.; Fang, E.; et al. A Randomised Trial of Peri-Operative Positive Airway Pressure for Postoperative Delirium in Patients at Risk for Obstructive Sleep Apnea after Regional Anaesthesia with Sedation or General Anaesthesia for Joint Arthroplasty. Anaesthesia 2017, 72(no. 6), 729–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Mohammed; Cascella, Marco. ICU Delirium. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, 2025; Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559280/.

- Outcomes Associated with ICU Delirium. Available online: https://www.icudelirium.org/medical-professionals/delirium/outcomes-associated-with-icu-delirium?ut (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Eadie, Rebekah; McKenzie, Cathrine A.; Hadfield, Daniel; et al. Opioid, Sedative, Preadmission Medication and Iatrogenic Withdrawal Risk in UK Adult Critically Ill Patients: A Point Prevalence Study. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2023, 45(no. 5), 1167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbraecken, Johan; Dieltjens, Marijke; Op de Beeck, Sara; et al. Non-CPAP Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnoea. Breathe 2022, 18(no. 3), 220164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, Jason; Boland, Elaine; Brooks, David. Importance of the Correct Diagnosis of Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression in Adult Cancer Patients and Titration of Naloxone. Clinical Medicine 2013, 13(no. 2), 149–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2016. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/abstract/2016/05000/does_obstructive_sleep_apnea_influence.18.aspx.

- Murphy, Glenn S.; Brull, Sorin J. Residual Neuromuscular Block: Lessons Unlearned. Part I: Definitions, Incidence, and Adverse Physiologic Effects of Residual Neuromuscular Block. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2010, 111(no. 1), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holfinger, S. J.; Lyons, M. M.; Keenan, B. T.; Mazzotti, D. R.; Mindel, J.; Maislin, G.; Cistulli, P. A.; Sutherland, K.; McArdle, N.; Singh, B.; Chen, N.-H.; Gislason, T.; Penzel, T.; Han, F.; Li, Q. Y.; Schwab, R.; Pack, A. I.; Magalang, U. J. Diagnostic Performance of Machine Learning-Derived OSA Prediction Tools in Large Clinical and Community-Based Samples. CHEST 2022, 161(3), 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chuang, L.-P.; Chen, N.-H.; Tu, Y.-K.; Hsieh, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Guilleminault, C. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: A bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2017, 36, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, R. A.; Zarmer, L.; West, K.; Chung, F. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Risk of Postoperative Complications after Non-Cardiac Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13(9), Article 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2017. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/abstract/2017/08000/preoperatively_screened_obstructive_sleep_apnea_is.34.aspx.

- Aboussouan, Loutfi S.; Bhat, Aparna; Coy, Todd; Kominsky, Alan. “Treatments for Obstructive Sleep Apnea: CPAP and Beyond.” Review. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2023, 90(no. 12), 755–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, Madeline; Kongpakpaisarn, Kullatham; Intihar, Taylor; Doyle, Margaret; Knauert, Melissa. 0846 Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Among Medical ICU Patients. Sleep 2023, 46, no. Supplement_1, A373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Effects of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on the Cardiovascular System: A Comprehensive Review. 2024. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/13/11/3223.

- Prediletto, Irene; Giancotti, Gilda; Nava, Stefano. COPD Exacerbation: Why It Is Important to Avoid ICU Admission. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12(no. 10), 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Validation of the STOP-Bang questionnaire as a screening tool for obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis | BMJ Open Respiratory Research. 2021. Available online: https://bmjopenrespres.bmj.com/content/8/1/e000848.

- The accuracy of simple, feasible alternatives to polysomnography for assessing sleep in intensive care: An observational study—Australian Critical Care. 2023. Available online: https://www.australiancriticalcare.com/article/S1036-7314(22)00030-3/abstract.

- Masa, J. F.; Corral, J.; Pereira, R.; Duran-Cantolla, J.; Cabello, M.; Hernández-Blasco, L.; Monasterio, C.; Alonso, A.; Chiner, E.; Rubio, M.; Garcia-Ledesma, E.; Cacelo, L.; Carpizo, R.; Sacristan, L.; Salord, N.; Carrera, M.; Sancho-Chust, J. N.; Embid, C.; Vázquez-Polo, F.-J.; Montserrat, J. M. Effectiveness of home respiratory polygraphy for the diagnosis of sleep apnoea and hypopnoea syndrome. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enhanced machine learning approaches for OSA patient screening: Model development and validation study | Scientific Reports. 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-70647-5.

- Benedetti, D.; Olcese, U.; Bruno, S.; Barsotti, M.; Tassoni, M. M.; Bonanni, E.; Siciliano, G.; Faraguna, U. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome Screening Through Wrist-Worn Smartbands: A Machine-Learning Approach. Nature and Science of Sleep 2022, 14, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Karin Gardner, and Douglas Clark Johnson. “Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing with Positive Airway Pressure Devices: Technology Update.” Medical Devices (Auckland, N.Z.) 8. (2015). 425–37. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Yizhong, Brendon J. Yee, Keith Wong, Ronald Grunstein, and Amanda Piper. “A Pilot Randomized Trial Comparing CPAP vs Bilevel PAP Spontaneous Mode in the Treatment of Hypoventilation Disorder in Patients with Obesity and Obstructive Airway Disease.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 18, no. 1. (2022). 99–107. [CrossRef]

- Nin, Nicolas; Muriel, Alfonso; Peñuelas, Oscar; et al. Severe Hypercapnia and Outcome of Mechanically Ventilated Patients with Moderate or Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Intensive Care Medicine 2017, 43(no. 2), 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extubation failure in intensive care unit: Predictors and management. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine 2008, 12(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Obstructive sleep apnoea heterogeneity and cardiovascular disease | Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2023. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41569-023-00846-6.

- DeMuro, Jonas P; Mongelli, Michael N; Hanna, Adel F. Use of Dexmedetomidine to Facilitate Non-Invasive Ventilation. International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science 2013, 3(no. 4), 274–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extubation in neurocritical care patients: The ENIO international prospective study | Intensive Care Medicine. 2022. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-022-06825-8.

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association | Circulation. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Risk: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Management | Current Cardiology Reports. 2020. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11886-020-1257-y.

- Prediletto, Irene; Giancotti, Gilda; Nava, Stefano. COPD Exacerbation: Why It Is Important to Avoid ICU Admission. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12(no. 10), 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Role of ICU-acquired weakness on extubation outcome among patients at high risk of reintubation | Critical Care | Full Text. 2020. Available online: https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-020-2807-9.

- Zhao, Q-Y; Wang, H; Luo, J-C; Luo, M-H; Liu, L-P; Yu, S-J; Liu, K; Zhang, Y-J; Sun, P; Tu, G-W; Luo, Z. Development and Validation of a Machine-Learning Model for Prediction of Extubation Failure in Intensive Care Units. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 676343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Santos, D.; Amorim, P.; Silva Martins, T.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Pereira Rodrigues, P. Enabling Early Obstructive Sleep Apnea Diagnosis With Machine Learning: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022, 24(9), e39452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatana, J.; Thavamani, A.; Umapathi, K. K.; Sankararaman, S.; Roy, A. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is Associated with Worsened Hospital Outcomes in Children Hospitalized with Asthma. Children 2024, 11(8), Article 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea and its association with pregnancy-related health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Sleep and Breathing. 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11325-018-1714-7.

- Borsoi, L.; Armeni, P.; Donin, G.; Costa, F.; Ferini-Strambi, L. The invisible costs of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): Systematic review and cost-of-illness analysis. PLOS ONE 2022, 17(5), e0268677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A. J. M. H.; Bansback, N.; Ayas, N. T. The Effect of OSA on Work Disability and Work-Related Injuries. CHEST 2015, 147(5), 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M. Obstructive sleep apnea screening protocol and safety measures: advancing treatment quality and reducing medical emergency team activation in patients with atrial fibrillation, respiratory diseases, and frailty. J Clin Sleep Med. 2024, 20(5), 673–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdul Jafar, N. K.; Mansfield, D. R. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Screening and Diagnosis Across Adult Populations: Are We Ready? Respirology 2025, 30(no. 7), 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Benchmarks | Findings from Literature | Clinical Relevance in ICU |

| Mechanical Ventilation |

|

|

| Extubation Failure |

|

|

| Perioperative Complications |

|

|

| Cardiovascular Risk |

|

|

| ICU Readmissions and Mortality |

|

|

| Neurocognitive/Functional Burden |

|

|

| Tool/Method | Description | Strengths | Limitations in ICU |

|

Overnight Oximetry / Overnight Pulse Oximetry |

|

|

|

| Machine Learning (ML) Models and Wearables |

|

|

|

| Respiratory Polygraphy / Home Sleep Testing (HST) |

|

|

|

| ASA OSA Checklist |

|

|

|

| STOP-BANG Questionnaire |

|

|

|

| Berlin Questionnaire |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).