1. Introduction

Hypercapnic respiratory failure is a syndrome with systemic effects characterized by an increase in partial carbon dioxide (pCO2) as a result of hypoventilation. Chronic respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are typically associated with this clinical condition. Respiratory failure can directly impact patient survival due to inadequate oxygenation and hemodynamic alterations resulting from hypercapnia [

1,

2]. Hypercapnic respiratory failure extends beyond the respiratory system and may result in cardiovascular complications. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a frequent rhythmic condition observed in these patients and significantly impacts patient prognosis.

Analysis of the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation revealed that hypoxia and hypercapnia are significant factors. In hypercapnic individuals, factors such as intrathoracic pressure fluctuations, alterations in autonomic nervous system activity, and atrial stretching and remodeling contribute to the onset of AF [

3]. Moreover, hypercapnia and hypoxemia can induce right ventricular hypertension and right atrial dilation by increasing pulmonary arterial pressure. These alterations result in cardiac hemodynamic imbalances, promoting the onset of atrial fibrillation. This may not only increase the incidence of atrial fibrillation but also negatively impact clinical outcomes, including cardioversion efficacy, ablation results, and in-hospital mortality [

4].

In several patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure monitored in pulmonary intensive care units, concurrent atrial fibrillation has been noted to be associated with a poor prognosis. AF may worsen respiratory function problems, impair cardiopulmonary balance, and make therapeutic procedures more difficult for this patient population. The frequency of AF in individuals with COPD has been reported to be twice as high as that in those without COPD. Furthermore, the presence of AF increases the risk of mortality in these patients [

5].

The presence of AF in patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure is often accompanied by additional clinical risks, such as heart failure. Furthermore, alterations in echocardiographic findings and the increased relevance of certain laboratory parameters are inevitable in this context. Identifying the clinical profiles of patients with type 2 respiratory failure who also have AF is of great importance. Recognizing these profiles can facilitate earlier diagnosis and help determine which patients should undergo more frequent ECG screening for timely detection of arrhythmias [

6,

7].

Considering the well-known severe complications of AF—such as acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, valvular diseases, and ischemic cerebrovascular events—demonstrating its potential additive negative impact on mortality in this patient population would provide a meaningful contribution to the medical literature.

This study investigated the impact of AF on survival in patients with hypercapnic type 2 respiratory failure in a multidimensional way. This study specifically investigated how pulmonary hypertension, cardiac hemodynamics, and blood gas changes affect the onset of AF in this patient population. Additionally, the impact of AF on clinical outcomes such as diagnosis, treatment, and in-hospital mortality will be assessed. The findings of this study may aid in the formulation of clinical treatment plans for this diverse patient population.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Consent to publish the study findings was also obtained from all participants.

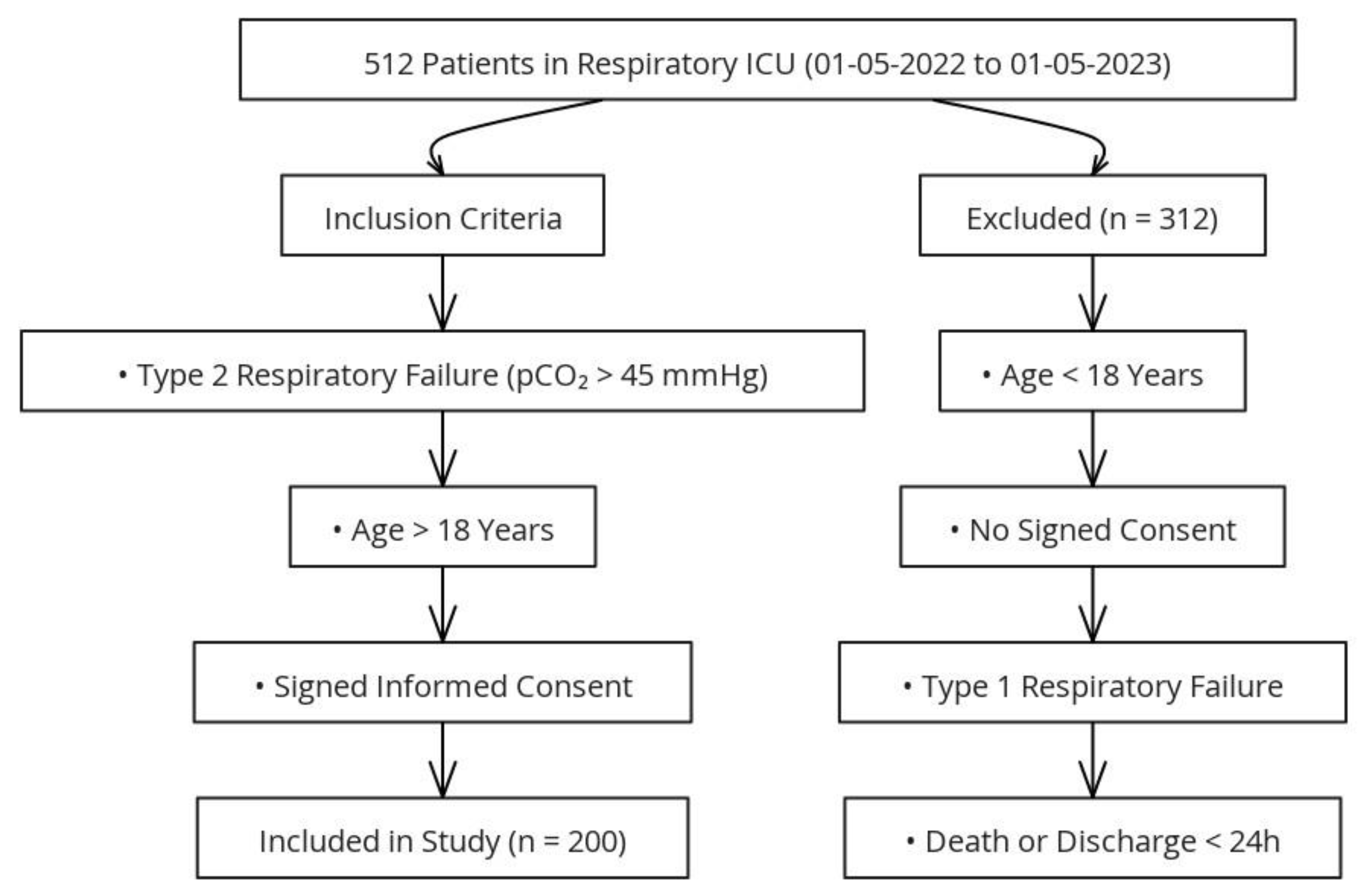

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ankara Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital (Date: 12.06.2024, Decision No: 2024-BÇEK/81). The study group consisted of 512 patients who were followed up in the respiratory intensive care unit between 01.05.2022 and 01.05.2023. Among these, 200 patients diagnosed with type 2 respiratory failure meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the study, while patients under the age of 18, those with incomplete medical records, patients with type 1 respiratory failure, and those referred to other centers were excluded (

Figure 1).

All data, including age, sex, comorbid conditions, laboratory findings, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and demographic and clinical data of the patients, were obtained from patient files and the hospital information management system. The diagnosis of "respiratory failure" was confirmed through arterial blood gas (ABG) values obtained during hospitalization and follow-up, whereas AF was confirmed via electrocardiography (ECG) at admission. Echocardiographic findings within the last year and the use of antiarrhythmic and anticoagulant drugs were reviewed.

The patients were divided into two groups: those with AF and those without AF. Blood parameters routinely analyzed during intensive care follow-up were retrospectively examined. These blood parameters were compared between the two groups, and their effects on mortality and length of hospital stay were evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses of the collected data were performed via IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for Windows, Version 30.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc version 23.2.1 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). The normality of distribution for numerical (continuous) data was assessed through descriptive statistics via the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov and Shapiro‒Wilk tests, skewness‒kurtosis values, histograms, and the proximity of outliers. Descriptive statistics are presented as the means and standard deviations for normally distributed numerical data and as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for nonnormally distributed data. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (n) and frequencies (%).

For the statistical analysis of categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. Student's t test was used for the analysis of normally distributed continuous variables with categorical variables, whereas the Mann‒Whitney U test was used for nonnormally distributed continuous variables with categorical variables. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical variables. In cases where any expected cell count was less than 5, Fisher’s exact test was applied. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed for survival evaluation, and the log-rank test was used to assess statistical significance. Cox regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors associated with mortality, and hazard ratios were reported with 95% confidence intervals. The data are presented within a 95% confidence interval. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

3. Results

The study was conducted with 200 patients who met the eligibility criteria. Among the patients, 118 (59%) were male. The mean age of the patients was 72±9 years. The most common comorbidity was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in

Table 1.

When the demographic characteristics of patients were evaluated on the basis of the presence of AF, patients with atrial fibrillation were older (p<0.001). An examination of comorbid conditions revealed that heart failure was more common and that the CCI was greater in these patients (p<0.001). Additionally, mortality was found to be greater in patients with AF (p=0.043) (

Table 2).

When patients with type 2 respiratory failure with AF were compared to those without AF based on arterial blood gas values at ICU admission, no statistically significant difference was found. The admission blood gas values of patients who were followed up with hypercapnic respiratory failure are presented in

Table 3.

AF was present in 50.5% of the patients included in the study. The blood test results of the patients based on the presence of AF are presented in

Table 4. Urea and creatinine levels were found to be higher in patients with AF (p<0.001). Among the complete blood count parameters, the hemoglobin, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and monocyte levels were lower in patients with AF (p<0.001, p=0.004, p=0.029, p=0.047, respectively). On the other hand, natriuretic peptide levels were greater in patients with AF (p<0.001) (

Table 4).

Among the patients included in the study, 42.5% passed away within 30 days of follow-up. The admission blood test results of the patients were evaluated on the basis of overall averages and mortality status. In deceased patients, urea, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), troponin, and D-dimer levels were significantly greater (p=0.046, p=0.017, p=0.02, p=0.011, respectively). Hemoglobin levels, on the other hand, were lower in deceased patients (p=0.06) (

Table 5).

A total of 125 patients underwent echocardiographic evaluation, of whom 65 had AF and 60 did not. Upon evaluating the echocardiographic findings of patients admitted to our intensive care unit with a diagnosis of type 2 respiratory failure, we identified certain statistically significant differences between those with and without AF. Patients with AF had more severe tricuspid and mitral regurgitation (p: 0.0047 and p: 0.0135, respectively). Ejection fraction values were also significantly lower in patients with AF (p: 0.001). Additionally, systolic pulmonary arterial pressures were significantly higher in patients with AF (p: 0.016). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of aortic regurgitation between the two groups (

Table 6).

To analyze the association of atrial fibrillation (AF) with other clinical conditions and comorbidities, the prevalence of additional diseases was examined in detail among patients with and without AF. Heart failure was the only comorbidity found to be significantly more common in patients with AF (p < 0.001). All other clinical conditions and comorbidities were statistically similar between the two groups (

Table 7).

Among patients admitted to the intensive care unit with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (AF), 19.8% were not prescribed anticoagulant therapy and 6.9% were not receiving antiarrhythmic medications at the time of admission (

Table 8).

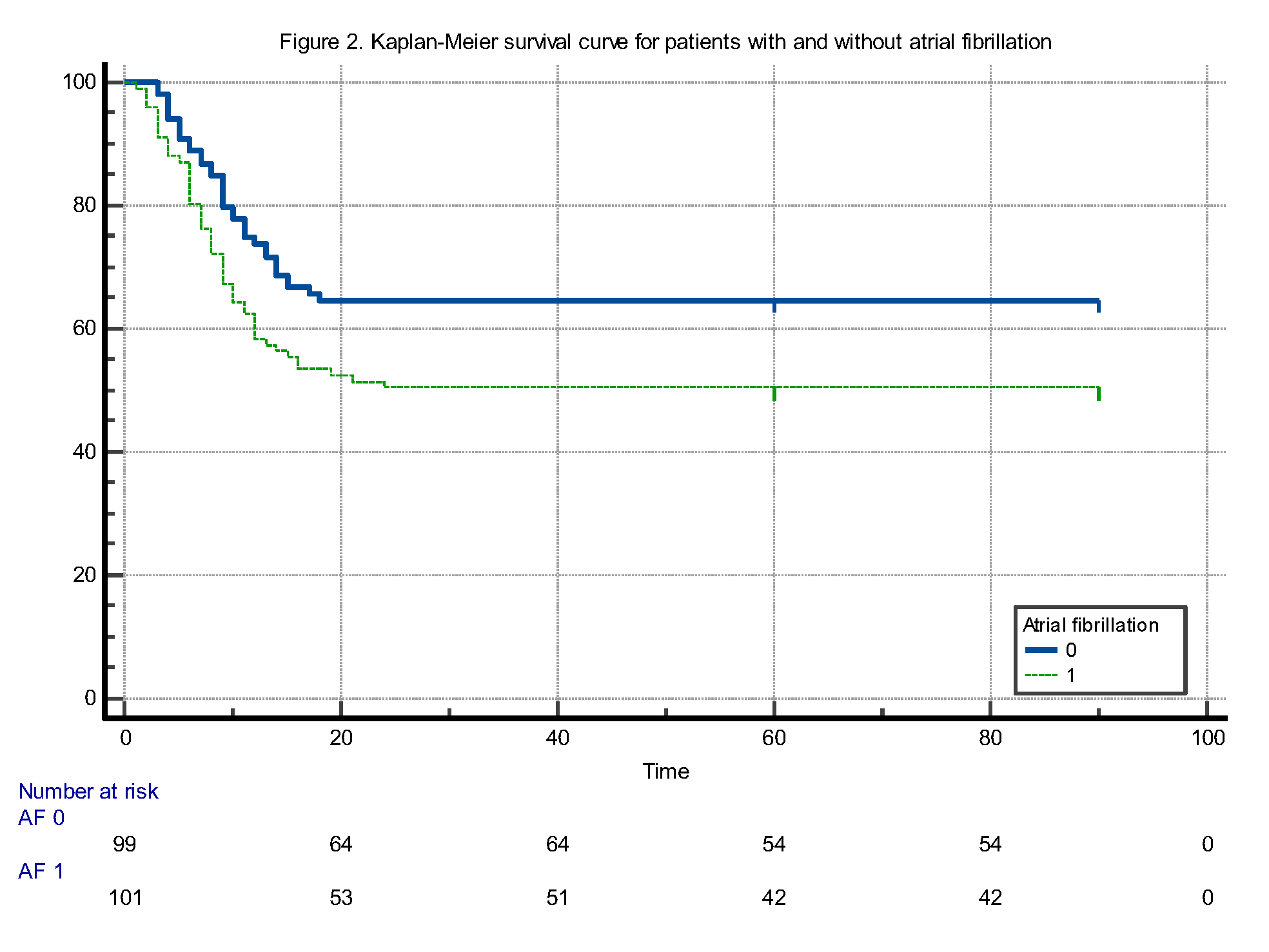

When comparing the survival times of patients with and without atrial fibrillation (AF), the mean survival time was found to be 49.6 (±4.07) days (95% CI: 41.6 to 57.6) for patients with AF and 61.4 (±3.8) days (95% CI: 53.8 to 69.05) for those without AF. The difference in survival times was statistically significant, favoring patients without AF (log-rank test: p = 0.031). Furthermore, according to this analysis, the mortality risk in patients with AF was calculated to be 1.6 times higher compared to those without AF (HR: 1.6084, 95% CI: 1.0437 to 2.4787) (Figure 2).

According to the backward stepwise Cox regression analysis, age and hemoglobin were identified as independent predictors of survival. Age was positively associated with mortality risk (HR: 1.057, 95% CI: 1.030–1.084, p<0.0001), indicating that each additional year of age increased the hazard by approximately 5.7%. Conversely, hemoglobin level was inversely related to mortality risk (HR: 0.877, 95% CI: 0.791–0.973, p: 0.0131), suggesting a protective effect. Each 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin level was associated with a 12.3% reduction in mortality risk. BNP level showed a borderline association with survival (p: 0.0917), but did not reach statistical significance. Variables such as urea, troponin, presence of AF, CCI and D-dimer were excluded from the final model (

Table 9).

4. Discussion

One of the most prominent findings of our study was the detection of AF in half of the patients admitted to our respiratory intensive care unit with a diagnosis of type 2 respiratory failure over a one-year period. In the literature, AF is recognized as the most common arrhythmia accompanying patients with type 2 respiratory failure and COPD [

8]. When we compared the clinical characteristics of patients with AF to those without AF among individuals with type 2 respiratory failure, we observed that patients with AF were older, had higher CCI scores—indicating a greater burden of comorbidities—and had a notably higher prevalence of heart failure. In parallel with our findings, the study conducted by Chen and Liao also demonstrated that patients with AF were older and had a higher prevalence of cardiac comorbidities, including heart failure, compared to those without AF [

9].

When further examining the characteristics of patients with AF in our study through laboratory test results, we observed that urea and creatinine levels were higher in patients with AF compared to those without AF and that natriuretic peptide levels were also elevated, consistent with the higher prevalence of heart failure in this group. Additionally, hemoglobin and lymphocyte levels were found to be lower in patients with AF. Rodríguez-Manero et al. reported elevated natriuretic peptide levels in patients with AF, attributing this to the high prevalence of heart failure in this population. Similarly, Terzano et al. found that urea and creatinine levels were higher in AF patients, explaining this finding in the context of heart failure and associated systemic hypoperfusion. Chen and Liao not only noted that anemia was more common in patients with AF, but—consistent with our findings—also emphasized its association with poor prognosis in this group. Furthermore, Romiti et al. suggested that lower lymphocyte counts observed in patients with AF reflect systemic inflammation and a weakened immune response [8-11].

When comparing the echocardiographic findings of our AF patients to those without AF among individuals with hypercapnic respiratory failure, we observed that advanced mitral and tricuspid regurgitation were more common in the AF group. Additionally, systolic pulmonary arterial pressures were higher, and ejection fraction values were lower in patients with AF. These findings suggest that AF in the context of hypercapnic respiratory failure is associated with more severe underlying cardiac dysfunction. Similarly, Terzano et al. reported that patients with COPD exacerbations and AF had significantly higher pulmonary artery pressures and a greater incidence of valvular abnormalities, particularly mitral regurgitation. Reduced ejection fraction was also more common in the AF group, highlighting the interplay between AF and impaired cardiac performance in respiratory patients [

5,

11].

Based on our survival analysis, we observed that patients with AF had shorter survival times compared to those without AF among individuals admitted to the intensive care unit with type 2 respiratory failure. However, in the backward stepwise Cox regression analysis—which included the parameters that differed significantly between survivors and non-survivors—AF did not emerge as an independent predictor of mortality [

12]. In the final model, only age, natriuretic peptide, and hemoglobin remained, with age and hemoglobin being the only variables that retained statistical significance. This finding aligns with results from Rodríguez-Mañero et al., who also found that while AF was associated with worse unadjusted survival in patients with COPD, it did not independently predict mortality after adjusting for age and comorbidities, emphasizing the stronger prognostic weight of systemic factors such as age and overall disease burden [

10]. Similarly, Xiao et al. reported that although AF prevalence was high in end-stage COPD patients, mortality was more strongly influenced by age, need for mechanical ventilation, and comorbidity burden rather than AF itself in multivariable analyses [

13]. Considering the contribution of low hemoglobin levels to mortality in type 2 respiratory failure, future studies may focus on this issue to determine whether a new transfusion threshold should be established specifically for this patient population. Just as the presence of cardiac disease can raise the transfusion threshold in intensive care units, type 2 respiratory failure itself—independent of cardiac comorbidities—may warrant a reassessment of red blood cell replacement criteria [

14].

In our study, there were no statistically significant differences in pCO₂, pO₂, pH, or HCO₃ levels between patients with and without AF at the time of ICU admission. This suggests that the presence of AF may not be directly related to the severity of gas exchange abnormalities at presentation. Supporting this, Lahousse et al. found that while reduced lung function was associated with increased AF risk over time, cross-sectional arterial blood gas values—such as pCO₂ and pH—did not differ significantly at baseline between patients who developed AF and those who did not, emphasizing the role of chronic pulmonary and cardiovascular remodeling over acute respiratory derangement in AF pathophysiology [

15].

In our study, we identified significant gaps in pre-ICU management by comparing AF diagnoses—based on ECGs obtained at ICU admission—with the patients’ ongoing anticoagulant and antiarrhythmic therapies at the time of admission. These deficiencies were particularly notable in anticoagulant therapy, which is vital for preventing thrombotic complications. Despite having a diagnosis of AF, approximately 20% of patients were not receiving any anticoagulant treatment prior to ICU admission, while about 7% were not on antiarrhythmic therapy [

16]. These findings are in line with the results of Wang et al., who reported substantial underutilization of anticoagulants in patients with AF, especially among those with chronic comorbidities such as COPD. Their study highlighted that up to one-quarter of eligible AF patients were not prescribed anticoagulants, often due to concerns about bleeding risk or a lack of cardiology follow-up, reflecting a broader issue of suboptimal adherence to evidence-based AF management in high-risk populations [

17].

Taken together, our findings highlight the multifactorial nature of AF in patients with type 2 respiratory failure, particularly within the intensive care setting. The coexistence of AF with elevated age, comorbidity burden, and cardiac dysfunction reflects a complex pathophysiological interaction rather than a direct effect of respiratory acidosis or gas exchange parameters. This complexity has been echoed in prior literature, where systemic inflammation, ventricular strain, and impaired myocardial oxygenation are increasingly recognized as key contributors to AF onset and progression in COPD and ICU cohorts. Furthermore, persistent gaps in the application of guideline-directed anticoagulation and rhythm control therapies suggest a real-world treatment inertia that may negatively impact outcomes. These findings underscore the need for a multidisciplinary approach to AF management in critically ill respiratory patients, incorporating early cardiology consultation, comprehensive risk stratification, and improved adherence to evidence-based therapies [18-20].

Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. First, it was designed as a retrospective, single-center study, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation was based solely on ECG recordings obtained at ICU admission, and paroxysmal AF cases may have been missed. Echocardiographic evaluations were not available for all patients and were conducted only in those with accessible records; therefore, cardiac functional data do not represent the entire study population. Furthermore, data on anticoagulant and antiarrhythmic therapy were extracted from hospital records, without access to detailed information regarding treatment adherence or reasons for discontinuation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that atrial fibrillation (AF) is highly prevalent among patients admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of type 2 respiratory failure. AF in this population was associated with older age, a greater burden of comorbidities, higher rates of heart failure, and abnormalities in both hematologic and cardiac biomarkers. Although AF appeared to be associated with increased mortality in univariate survival analyses, it did not emerge as an independent predictor in multivariable models. Instead, age and hemoglobin levels were identified as independent determinants of mortality. Our findings also revealed a noteworthy proportion of patients with AF who were not receiving appropriate anticoagulant therapy. Early recognition of AF, identification of cardiac dysfunction, and timely implementation of appropriate treatment strategies are crucial to improving prognosis in this patient group. In this context, multidisciplinary evaluation and future prospective studies with larger cohorts are warranted to enhance clinical management and outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and M.Y.; methodology, D.Ç.; software, F.C., M.A.; validation, O.M., E.A., Y.T.G. and T.Ö.; formal analysis, M.Y., O.M.; investigation, E.N.A.G.; resources, O.M. and M.Y; data curation, E.N.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M., M.Y..; writing—review and editing, T.Ö. and T.Ö..; visualization, M.A. and E.A.; supervision, O.M. and E.A.; project administration, O.M. and D.Ç..; funding acquisition, M.Y., Y.T.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors .

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ankara Atatürk Training and Research Hospital (approval date: 12.06.2024, decision number: 2024-BÇEK/81).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grippi, MA. Respiratory failure: an overview. In: Fishman AP; ed. Fishman's Pulmonary Disease and Disorders. 3rd ed. New York: Mc-Graw Hill; 1998:2525–35.

- Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–65.

- Bemis CE, Serur JR, Borkenhagen D, Sonnenblick EH, Urschel CW. Influence of right ventricular filling pressure on left ventricular pressure and dimension. Circ Res. 1974;34:498–50.

- Terzano C, Conti V, Di Stefano F, et al. Comorbidity, hospitalization, and mortality in COPD: results from a longitudinal study. Lung. 2010;188:321–329.

- Konecny T, Park JY, Somers KR, et al. Relation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:272–7.

- Ari M, Ari E. Efficacy of Age-Adjusted Dyspnea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidemia and Atrial Fibrillation Score in Predicting Long-Term Survival in COPD-Related Persistent Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. Life (Basel). 2025;15(4):533. Published 2025 Mar 24. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C. W. de M., SILVA, J. C., Bezerra, A. L. Q., Corsso, C. del, Sousa, M. B. V. de, Castro, B., Fedatto, M. C., Gutierrez, M., & Fausto, A. T. (2025). Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis, therapeutic management and prevention of thromboembolic complications in patients with heart disease. [CrossRef]

- Giulio Francesco Romiti, Bernadette Corica, Eugenia Pipitone, Marco Vitolo, Valeria Raparelli, Stefania Basili, Giuseppe Boriani, Sergio Harari, Gregory Y H Lip, Marco Proietti, the AF-COMET International Collaborative Group , Prevalence, management and impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4,200,000 patients, European Heart Journal, Volume 42, Issue 35, 14 September 2021, Pages 3541–3554. [CrossRef]

- Chen CY, Liao KM. The impact of atrial fibrillation in patients with COPD during hospitalization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2105-2112. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mañero M, López-Pardo E, Cordero A, Ruano-Ravina A, Novo-Platas J, Pereira-Vázquez M, Martínez-Gómez Á, García-Seara J, Martínez-Sande JL, Peña-Gil C, Mazón P, García-Acuña JM, Valdés-Cuadrado L, González-Juanatey JR. A prospective study of the clinical outcomes and prognosis associated with comorbid COPD in the atrial fibrillation population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019 Feb 12;14:371-380. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzano C, Romani S, Conti V, Paone G, Oriolo F, Vitarelli A. Atrial fibrillation in the acute, hypercapnic exacerbations of COPD. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014 Oct;18(19):2908-17. [PubMed]

- Mehreen T, Ishtiaq W, Rasheed G, Kharadi N, Kiani SS, Ilyas A, Kaleem MA, Abbas K. In-Hospital Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Versus Patients Without AF. Cureus. 2021 Oct 13;13(10):e18761. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X. Han, H., Wu, C., He, Q., Ruan, Y., Zhai, Y., Gao, Y., Zhao, X., & He, J. (2019). Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation in Hospital Encounters With End-Stage COPD on Home Oxygen: National Trends in the United States. Chest, 155, 918–927. [CrossRef]

- Schönhofer B, Wenzel M, Geibel M, Köhler D. Blood transfusion and lung function in chronically anemic patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Crit Care Med. 1998 Nov;26(11):1824-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grymonprez M, Vakaet V, Kavousi M, Stricker BH, Ikram MA, Heeringa J, Franco OH, Brusselle GG, Lahousse L. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the development of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2019 Feb 1;276:118-124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker C, Garavalia L, Garavalia B, et al. Exploring barriers to optimal anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: interviews with clinicians. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:129-135. [CrossRef]

- Moudallel S, van den Bemt BJF, Zwikker H, de Veer A, Rydant S, Dijk LV, Steurbaut S. Association of conflicting information from healthcare providers and poor shared decision making with suboptimal adherence in direct oral anticoagulant treatment: A cross-sectional study in patients with atrial fibrillation. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Jan;104(1):155-162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen LaPointe NM, Lokhnygina Y, Sanders GD, Peterson ED, Al-Khatib SM. Adherence to guideline recommendations for antiarrhythmic drugs in atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2013;166(5):871-878. [CrossRef]

- O'Neal WT, Sandesara P, Patel N, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18(7):725-729. [CrossRef]

- Jover E, Marín F, Roldán V, Montoro-García S, Valdés M, Lip GY. Atherosclerosis and thromboembolic risk in atrial fibrillation: focus on peripheral vascular disease. Ann Med. 2013 May;45(3):274-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).