Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

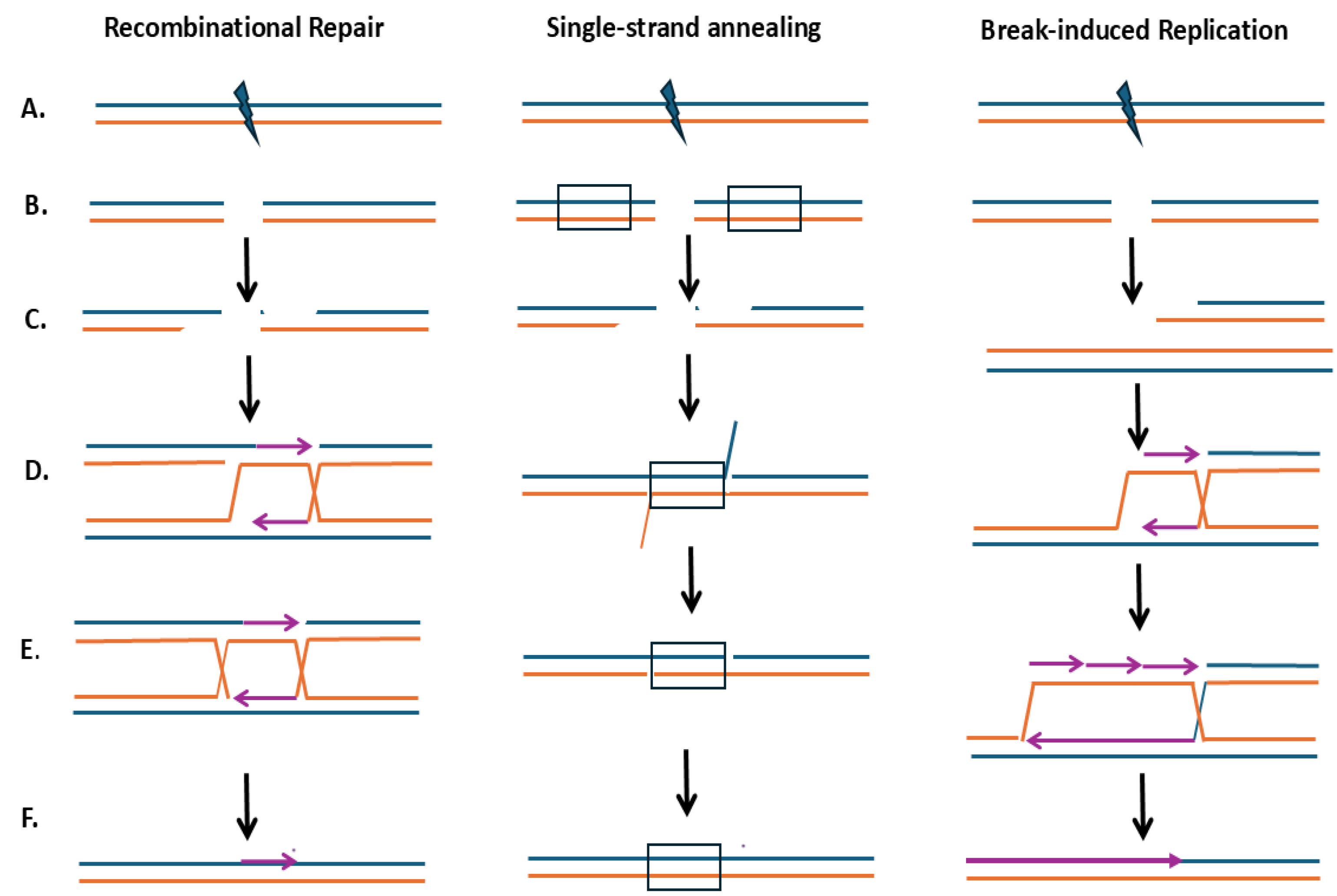

1. Introduction

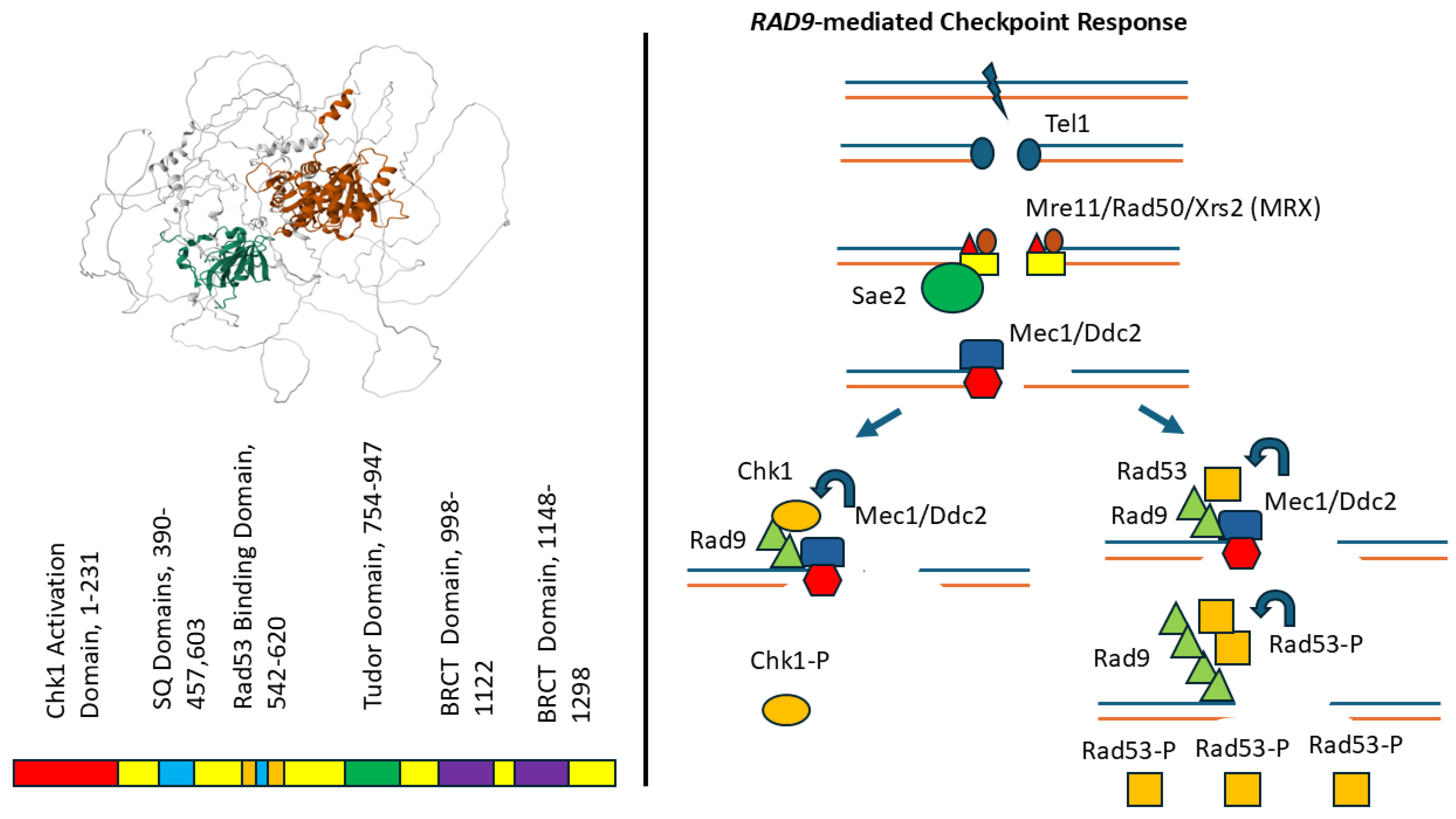

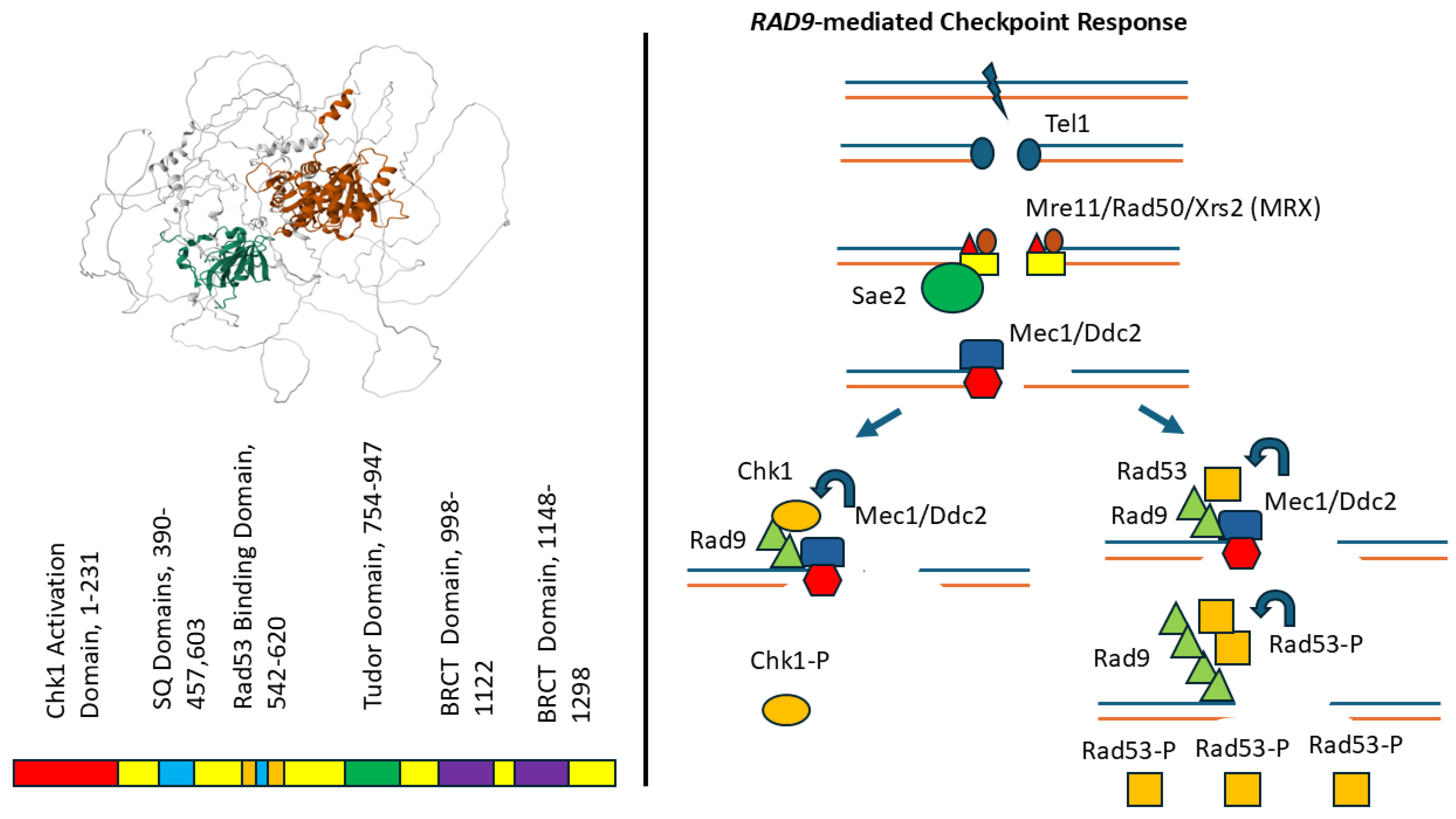

2. Rad9 Protein and Function

3. Hr Phenotypes of Rad9 Mutants

3.a. RAD9 Requirement for SCR

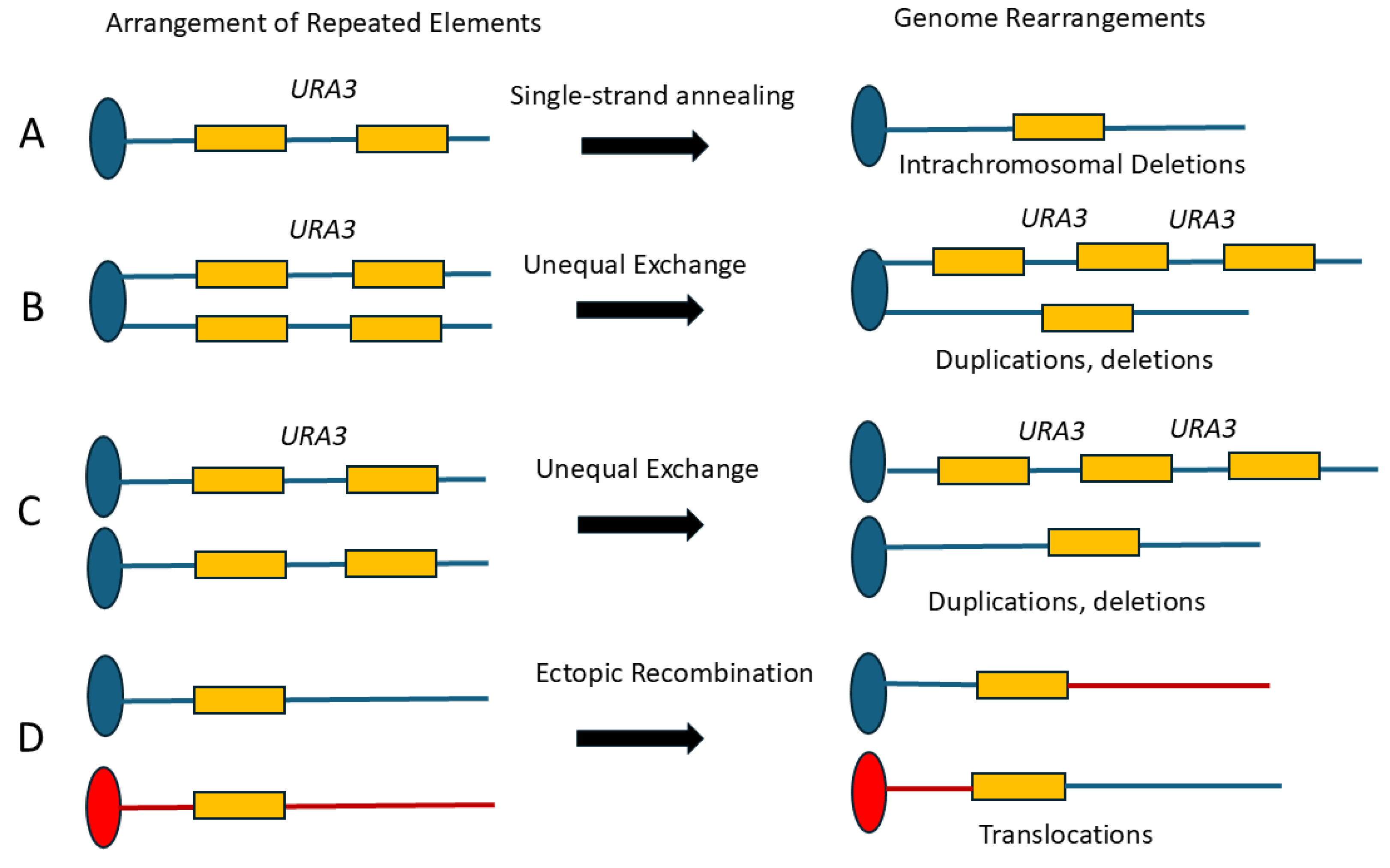

3.b. rDNA Repeat Instability and CNV

3.c. RAD9 Is Not Required for SSA Unless There Are Significant Mismatches Between Annealing Sequences

3.d. RAD9 Affects the Outcome of DSB-induced Homolog Recombination

3.e. RAD9 Suppresses Ectopic Recombination That Generates Translocations

3.f. RAD9 and RAD50 Group Genes Are Separate Pathways For Suppressing Ectopic Events in Diploid Strains

3.g. RAD9 and SGS1 Suppress HR Between Divergent Genes and Ty1 Elements

3.h. RAD9 Is Required for Enhanced Genetic Instability Due to HR Exhibited in mec1 Hypomorphs and Promotes Genetic Instability Resulting from DNA Replication Defects

4. Rad9 Role in Suppressing Gcrs

5. Similarities of Rad9 Orthologs in Promoting Genetic Stability

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Hartwell, L.H.; Weinert, T.A. Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science. 1989, 246, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, L. Lack of chemically induced mutation in repair-deficient mutants of yeast. Genetics 1974, 78, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argueso, J.L.; Westmoreland, J.; Mieczkowski, P.A.; Gawel, M.; Petes, T.D.; Resnick, M.A. Double-strand breaks associated with repetitive DNA can reshape the genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2008, 105, 11845–11850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.B.; Lewis, A.L.; Baldwin, K.K.; Resnick, M.A. Lethality induced by a single site-specific double-strand break in a dispensable yeast plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 5613–5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussiol, J.R.; Soares, B.L.; Oliveira, F.M.B. From yeast to humans: Understanding the biology of DNA Damage Response (DDR) kinases. Genet Mol Biol. 2019, 43, e20190071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, M.C.; Dibitetto, D.; Smolka, M.B. DNA damage kinase signaling: checkpoint and repair at 30 years. EMBO J. 2019, 16(38(18)), e101801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboussekhra, A.; Vialard, J.E.; Morrison, D.E.; de la Torre-Ruiz, M.A.; Cernakova, L.; Fabre, F.; Lowndes, N. F. A novel role for the budding yeast RAD9 checkpoint gene in DNA damage-dependent transcription. The EMBO Journal 1996, 15, 3912–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaehnig, E.J.; Kuo, D.; Hombauer, H.; Ideker, T.G.; Kolodner, R.D. Checkpoint kinases regulate a global network of transcription factors in response to DNA damage. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerici, M.; Trovesi, C.; Galbiati, A.; Lucchini, G.; Longhese, M.P. Mec1/ATR regulates the generation of single-stranded DNA that attenuates Tel1/ATM signaling at DNA ends. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casari, E.; Tisi, R.; Longhese, M. P. Checkpoint activation and recovery: regulation of the 9-1-1 axis by the PP2A phosphatase. DNA repair 2025, 103854–103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Niu, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, J.; Papusha, A.; Cui, D.; Pan, X.; Kwon, Y.; Sung, P.; Ira, G. Enrichment of Cdk1-cyclins at DNA double-strand breaks stimulates Fun30 phosphorylation and DNA end resection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 2742–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, D.P.; Haber, J.E.; Smolka, M.B. Checkpoint Responses to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Annu Rev Biochem. 2020, 89, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercero, J.A.; Diffley, J.F. Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature. 2001, 412, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Gn, K.; Lichten, M. Unresolved Recombination Intermediates Cause a RAD9-Dependent Cell Cycle Arrest in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2019, 213, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvik, B.; Carson, M.; Hartwell, L. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 1995, 15, 6128–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, V.; Sapountzi, M.; Granata, A.; Pellicioli, M.; Vaze, J.E.; Haber, J.; Plevani, P.; Lydall, D.; Muzi-Falconi, M. Histone methyltransferase Dot1 and Rad9 inhibit single-stranded DNA accumulation at DSBs and uncapped telomeres. EMBO J. 2008, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadis, C.; Nikolaou, C.; Fragiadakis, G.S.; Tsiliki, G.; Alexandraki, D. Rad9 interacts with Aft1 to facilitate genome surveillance in fragile genomic sites under non-DNA damage-inducing conditions in S. cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 12650–12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulovich, A.G.; Margulies, R.U.; Garvik, B.M.; Hartwell, L.H. RAD9, RAD17, and RAD24 are required for S phase regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in response to DNA damage. Genetics 1997, 145, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, N.A.; Bjornsti, M.A.; Fink, G.R. A novel mutation in DNA topoisomerase I of yeast causes DNA damage and RAD9-dependent cell cycle arrest. Genetics 1993, 133, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, Y.; Barcelo, J.M.; Rao, V.A.; Sordet, O.; Jobson, A.G.; Thibaut, L.; Miao, Z.H.; Seiler, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Marchand, C.; Agama, K.; Nitiss, J.L.; Redon, C. Repair of topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2006, 81, 179–229. [Google Scholar]

- Usui, T.; Shinohara, A. Rad9, a 53BP1 Ortholog of Budding Yeast, Is Insensitive to Spo11-Induced Double-Strand Breaks During Meiosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 635383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyndaker, A.M.; Goldfarb, T.; Alani, E. Mutants defective in Rad1-Rad10-Slx4 exhibit a unique pattern of viability during mating-type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2008, 179, 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Haber, J.E. Sources of DNA double-strand breaks and models of recombinational DNA repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014, 6(9), a016428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunborg, G.; Resnick, M.A.; Williamson, D.H. Cell-cycle-specific repair of DNA double strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Radiat Res. 1980, 82, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyk, L.C.; Hartwell, L.H. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1992, 132, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustig, A.J.; Petes, T.D. Identification of yeast mutants with altered telomere structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 1398–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, R.; Ogawa, H. An essential gene, ESR1, is required for mitotic cell growth, DNA repair, and meiotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 3104–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloh, Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat. Rev. 2003, 3, 3155–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ira, G.; Pellicioli, A.; Balijja, A.; Wang, X.; Fiorani, S.; Carotenuto, W.; Liberi, G.; Bressan, D.; Wan, L.; Hollingsworth, N.M.; Haber, J.E.; Foiani, M. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature 2004, 431, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, E. J.; Comstock, W. J.; Faça, V. M.; Vega, S. C.; Gnügge, R.; Symington, L. S.; et al. Phosphoproteomics reveals a distinctive Mec1/ATR signaling response upon DNA end hyper-resection. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flott, S.; Kwon, Y.; Pigli, Y.Z.; Rice, P.A.; Sung, P.; Jackson, S.P. Regulation of Rad51 function by phosphorylation. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, K.; Bashkirov, V.I.; Rolfsmeier, M.; Haghnazari, E.; McDonald, W.H.; Anderson, S.; Bashkirova, E.V.; Yates, J.R.; Heyer, W.D. Phosphorylation of Rad55 on serines 2, 8, and 14 is required for efficient homologous recombination in the recovery of stalled replication forks. Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 8396–8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Caldwell, J.M.; Pereira, E.; Baker, R.W.; Sanchez, Y. ATRMec1 phosphorylation-independent activation of Chk1 in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, Y.; Desany, B.A.; Jones, W.J; Liu, Q.; Wang, B.; Elledge, S.J. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science. 1996, 271, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, G.W.; Lowndes, N.F. Role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 protein in sensing and responding to DNA damage. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003, 31, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, Y.; Bachant, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, F.; Liu, D.; Tetzlaff, M.; Elledge, S.J. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science 1999, 286, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chabes, A.; Domkin, V.; Thelander, L.; Rothstein, R. The ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 is a new target of the Mec1/Rad53 kinase cascade during growth and in response to DNA damage. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 3544–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, T.; Foster, S.S.; Petrini, J.H. Maintenance of the DNA-damage checkpoint requires DNA-damage-induced mediator protein oligomerization. Mol Cell. 2009, 33, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Tang, Z.; Yu, H.; Cohen-Fix, O. Two distinct pathways for inhibiting pds1 ubiquitination in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 45027–45033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Qin, J.; Elledge, S.J. Regulation of the Bub2/Bfa1 GAP complex by Cdc5 and cell cycle checkpoints. Cell 2001, 107, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovets, S.; Blackburn, E.H. DNA damage signaling prevents deleterious telomere addition at DNA breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1383–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, V.; Kalck, V.; Horigome, C.; Towbin, B.D.; Gasser, S.M. Increased mobility of double-strand breaks requires Mec1, Rad9 and the homologous recombination machinery. Nat Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miné-Hattab, J.; Rothstein, R. Increased chromosome mobility facilitates homology search during recombination. Nat Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, G.H.; Balakrishnan, L.; Dubarry, M.; Campbell, J.L.; Lydall, D. The 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp stimulates DNA resection by Dna2-Sgs1 and Exo1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 10516–10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcomini, I.; Shimada, K.; Delgoshaie, N.; Yamamoto, I.; Seeber, A.; Cheblal, A.; Horigome, C.; Naumann, U.; Gasser, S.M. Asymmetric Processing of DNA Ends at a Double-Strand Break Leads to Unconstrained Dynamics and Ectopic Translocation. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 2614–2628.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, F.; Giannattasio, M.; Puddu, F.; Granata, M.; Pellicioli, A.; Plevani, P.; Muzi-Falconi, M. Checkpoint mechanisms at the intersection between DNA damage and repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009, 8, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, K.; Lowndes, N.F.; Grenon, M. Eukaryotic DNA damage checkpoint activation in response to double-strand breaks. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1447–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, B.O.; Symington, L.S. Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004, 38, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangloff, S.; McDonald, J.P.; Bendixen, C.; Arthur, L.; Rothstein, R. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994, 14, 8391–8398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, S.C.; Rass, U.; Blanco, M.G.; Flynn, H.R.; Skehel, J.M.; West, S.C. Identification of Holliday junction resolvases from humans and yeast. Nature. 2008, 20, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Dibitetto, D.; De Gregorio, G.; Eapen, V.V.; Rawal, C.C.; Lazzaro, F.; Tsabar, M.; Marini, F.; Haber, J.E.; Pellicioli, A. Functional interplay between the 53BP1-ortholog Rad9 and the Mre11 complex regulates resection, end-tethering and repair of a double-strand break. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1004928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussin, C.; Porubský, D.; Spierings, D.C.; Halsema, N.; Rentas, S.; Guryev, V.; Lansdorp, P.M.; Chang, M. Genome-wide mapping of sister chromatid exchange events in single yeast cells using Strand-seq. Elife 2017, 6e30560. [Google Scholar]

- Fasullo, M.; Giallanza, P.; Dong, Z.; Cera, C.; Bennett, T. Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad51 mutants are defective in DNA damage-associated sister chromatid exchanges but exhibit increased rates of homology-directed translocations. Genetics 2001, 158, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Fasullo, M. Multiple recombination pathways for sister chromatid exchange in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: role of RAD1 and the RAD52 epistasis group genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 2576–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, E.L.; Sugawara, N.; White, C.I.; Fabre, F.; Haber, J.E. Mutations in XRS2 and RAD50 delay but do not prevent mating-type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1994, 14(5), 3414–3425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Westmoreland, J.W.; Resnick, M.A. Recombinational repair of radiation-induced double-strand breaks occurs in the absence of extensive resection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 29, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, E.L.; Sugawara, N.; Fishman-Lobell, J.; Haber, J.E. Genetic requirements for the single-strand annealing pathway of double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1996, 142, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, F.; Aguilera, A. Role of reciprocal exchange, one-ended invasion crossover and single-strand annealing on inverted and direct repeat recombination in yeast: different requirements for the RAD1, RAD10, and RAD52 genes. Genetics 1995, 139, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiasen, D.P.; Lisby, M. Cell cycle regulation of homologous recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2014, 38, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saka, Y.; Esashi, F.; Matsusaka, T.; Mochida, S.; Yanagida, M. Damage and replication checkpoint control in fission yeast is ensured by interactions of Crb2, a protein with BRCT motif, with Cut5 and Chk1. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 3387–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpha-Bazin, B.; Lorphelin, A.; Nozerand, N.; Charier, G.; Marchetti, C.; Bérenguer, F.; Couprie, J.; Gilquin, B.; Zinn-Justin, S.; Quéméneur, E. Boundaries and physical characterization of a new domain shared between mammalian 53BP1 and yeast Rad9 checkpoint proteins. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnakwe, C.C.; Altaf, M.; Côté, J.; Kron, S.J. Dissection of Rad9 BRCT domain function in the mitotic checkpoint response to telomere uncapping. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009, 8, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siede, W.; Friedberg, A.S.; Friedberg, E.C. RAD9-dependent G1 arrest defines a second checkpoint for damaged DNA in the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A 1993, 90, 7985–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacal, J.; Moriel-Carretero, M.; Pardo, B.; Barthe, A.; Sharma, S.; Chabes, A.; Lengronne, A.; Pasero, P. Mrc1 and Rad9 cooperate to regulate initiation and elongation of DNA replication in response to DNA damage. EMBO J. 2018, 37, (21):e99319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Niu, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, J.; Papusha, A.; Cui, D.; Pan, X.; Kwon, Y.; Sung, P.; Ira, G. Enrichment of Cdk1-cyclins at DNA double-strand breaks stimulates Fun30 phosphorylation and DNA end resection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 2742–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; Bridgland, A.; Meyer, C.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Ballard, A.J.; Cowie, A.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Nikolov, S.; Jain, R.; Adler, J.; Back, T.; Petersen, S.; Reiman, D.; Clancy, E.; Zielinski, M.; Steinegger, M.; Pacholska, M.; Berghammer, T.; Bodenstein, S.; Silver, D.; Vinyals, O.; Senior, A.W.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kohli, P.; Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. Available online: https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/P14737. [CrossRef]

- Usui, T.; Foster, S.S.; Petrini, J.H. Maintenance of the DNA-damage checkpoint requires DNA-damage-induced mediator protein oligomerization. Mol Cell. 2009, 33, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancelot, N.; Charier, G.; Couprie, J.; Duband-Goulet, I.; Alpha-Bazin, B.; Quémeneur, E.; Ma, E.; Marsolier-Kergoat, M.C.; Ropars, V.; Charbonnier, J.B.; Miron, S.; Craescu, C.T.; Callebaut, I.; Gilquin, B.; Zinn-Justin, S. The checkpoint Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 protein contains a tandem tudor domain that recognizes DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 5898–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfander, B; Diffley, JF. Dpb11 coordinates Mec1 kinase activation with cell cycle-regulated Rad9 recruitment. EMBO J 2011, 30(24), 4897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.F.; Duong, J.K.; Sun, Z.; Morrow, J.S.; Pradhan, D.; Stern, D.F. Rad9 phosphorylation sites couple Rad53 to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2002, 9, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, M.; Lowndes, NF. Remodeling the Rad9 checkpoint complex: preparing Rad53 for action. Cell Cycle 2004, 3, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialard, J.E.; Gilbert, C.S.; Green, C.M.; Lowndes, NF. The budding yeast Rad9 checkpoint protein is subjected to Mec1/Tel1-dependent hyperphosphorylation and interacts with Rad53 after DNA damage. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 5679–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankley, R.T.; Lydall, D. A domain of Rad9 specifically required for activation of Chk1 in budding yeast. J Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinert, T.A.; Hartwell, L.H. Cell cycle arrest of cdc mutants and specificity of the RAD9 checkpoint. Genetics 1993, 134, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, H.L. Spontaneous chromosome loss in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is suppressed by DNA damage checkpoint functions. Genetics 2001, 159, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, J.F.; Irene, C.; Dershowitz, A.; Brost, R.L.; Tobin, M.L.; di Sanzo, F.M.; Wang, J.Y.; Boone, C.; Newlon, C.S. The DNA damage response pathway contributes to the stability of chromosome III derivatives lacking efficient replicators. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6(12), e1001227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, B.; Crabbé, L.; Pasero, P. Signaling pathways of replication stress in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 1(17(2)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallen, E.A.; Cross, F.R. Mutations in RAD27 define a potential link between G1 cyclins and DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1995, 15, 4291–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Rivera, M.; Phelps, S.; Sridharan, M.; Becker, J.; Lamb, N.A.; Kumar, C.; Sutton, M.D.; Bielinsky, A.; Balakrishnan, L.; Surtees, J.A. Elevated MSH2 MSH3 expression interferes with DNA metabolism in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 12185–12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrauwère, H.; Loeillet, S.; Lin, W.; Lopes, J.; Nicolas, A. Links between replication and recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a hypersensitive requirement for homologous recombination in the absence of Rad27 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 8263–8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M.; Bennett, T.; AhChing, P.; Koudelik, J. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD9 checkpoint reduces the DNA damage-associated stimulation of directed translocations. Mol Cell Biol. 1998, 18, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, F.; Refolio, E; Cordón-Preciado, V; Cortés-Ledesma, F; Aragón, L; Aguilera, A; San-Segundo, PA. The Dot1 histone methyltransferase and the Rad9 checkpoint adaptor contribute to cohesin-dependent double-strand break repair by sister chromatid recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2009, 182, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ström, L.; Karlsson, C.; Lindroos, H.B.; Wedahl, S.; Katou, Y.; Shirahige, K.; Sjögren, C. Postreplicative formation of cohesion is required for repair and induced by a single DNA break. Science 2007, 317, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwin, I.; Pilarczyk, E.; Wysocki, R. The Emerging Role of Cohesin in the DNA Damage Response. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M.; Dong, Z.; Sun, M.; Zeng, L. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD53 (CHK2) but not CHK1 is required for double-strand break-initiated SCE and DNA damage-associated SCE after exposure to X rays and chemical agents. DNA Repair (Amst). 2005, 4, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasullo, M.; Sun, M. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae checkpoint genes RAD9, CHK1 and PDS1 are required for elevated homologous recombination in a mec1 (ATR) hypomorphic mutant. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covo, S.; Chiou, E.; Gordenin, D.A.; Resnick, M.A. Suppression of allelic recombination and aneuploidy by cohesin is independent of Chk1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2014, 9(12), e113435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M.; Zeng, L.; Giallanza, P. Enhanced stimulation of chromosomal translocations by radiomimetic DNA damaging agents and camptothecin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad9 checkpoint mutants. Mutat Res. 2004, 547, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lawrence, C.W. The error-free component of the RAD6/RAD18 DNA damage tolerance pathway of budding yeast employs sister-strand recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 15954–15959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M; Sun, M. Both RAD5-dependent and independent pathways are involved in DNA damage-associated sister chromatid exchange in budding yeast. AIMS Genet 2017, 4, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, S.; Watanabe, K.; Watanabe, H.; Shirahige, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Maki, H. Abnormality in initiation program of DNA replication is monitored by the highly repetitive rRNA gene array on chromosome XII in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whale, A.J.; King, M.; Hull, R.M.; Krueger, F.; Houseley, J. Stimulation of adaptive gene amplification by origin firing under replication fork constraint. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMase, D.; Zeng, L.; Cera, C.; Fasullo, M. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PDS1 and RAD9 checkpoint genes control different DNA double-strand break repair pathways. DNA Repair 2005, 4, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.M.; Lyndaker, A.M.; Alani, E. The DNA damage checkpoint allows recombination between divergent DNA sequences in budding yeast. DNA Repair (Amst). 2011, 10, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flott, S.; Alabert, C.; Toh, G.W.; Toth, R.; Sugawara, N.; Campbell, D.G.; Haber, J.E.; Pasero, P.; Rouse, J. Phosphorylation of Slx4 by Mec1 and Tel1 regulates the single-strand annealing mode of DNA repair in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 6433–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, G.W.; Sugawara, N.; Dong, J.; Toth, R.; Lee, S.E.; Haber, J.E.; Rouse, J. Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation of Slx4 stimulates Rad1-Rad10-dependent cleavage of non-homologous DNA tails. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010, 9, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinert, T. A.; Hartwell, L. H. Characterization of the RAD9 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and evidence that it acts posttranslationally in cell cycle arrest after DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990, 10, 6554–6564. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, T.; Weinert, T. Ontogeny of Unstable Chromosomes Generated by Telomere Error in Budding Yeast. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12(10), e1006345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Sun, M.; Fasullo, M. Checkpoint and recombination pathways independently suppress rates of spontaneous homology-directed chromosomal translocations in budding yeast. Front Genet. 2025, 6, 1479307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, R.J.; Greenwell, P.W.; Dominska, M.; Petes, T.D. Regulation of genome stability by TEL1 and MEC1, yeast homologs of the mammalian ATM and ATR genes. Genetics 2002, 161, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, M.; Rawal, C.C.; Lodovichi, S.; Vietri, M.Y.; Pellicioli, A. Rad9/53BP1 promotes DNA repair via crossover recombination by limiting the Sgs1 and Mph1 helicases. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, D.M.; Connelly, C.; Hieter, P. Break copy" duplication: a model for chromosome fragment formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1997, 147, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Morishita, J.; Umezu, K.; Shirahige, K.; Maki, H. Involvement of RAD9-dependent damage checkpoint control in arrest of cell cycle, induction of cell death, and chromosome instability caused by defects in origin recognition complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 2002, 1, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, K.; Lowndes, N.F.; Grenon, M. Eukaryotic DNA damage checkpoint activation in response to double-strand breaks. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1447–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Game, J.C.; Williamson, M.S.; Spicakova, T.; Brown, J.M. The RAD6/BRE1 histone modification pathway in Saccharomyces confers radiation resistance through a RAD51-dependent process that is independent of RAD18. Genetics 2006, 173, 1951–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannunzio, N.R.; Manthey, G.M.; Bailis, A. M. RAD59 and RAD1 cooperate in translocation formation by single-strand annealing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Current genetics 210(56), 87–100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Kantake, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Kowalczykowski, S.C. Rad51 protein controls Rad52-mediated DNA annealing. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283, 14883–14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, D.N.; Pham, N.; Tsai, A.M.; Janto, N.V.; Choi, J.; Ira, G.; Haber, J.E. A Rad51-independent pathway promotes single-strand template repair in gene editing. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16(10), e1008689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.H.; Wu, J.; Kolodner, R.D. Control of translocations between highly diverged genes by Sgs1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the Bloom's syndrome protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 5406–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, S.; Deem, A.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Argueso, J.L.; Malkova, A. Cascades of genetic instability resulting from compromised break-induced replication. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10(2), e1004119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Bonetti, D.; Carraro, M.; Longhese, M.P. Rad9/53BP1 protects stalled replication forks from degradation in Mec1/ATR-defective cells. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrill, B.J.; Holm, C. A requirement for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is caused by DNA replication defects of mec1 mutants. Genetics. 1999, 153, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasullo, M.; Tsaponina, O.; Sun, M.; Chabes, A. Elevated dNTP levels suppress hyper-recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae S-phase checkpoint mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Sanford, E. J.; Hung, S. H.; Wagner, M.; Heyer, W. D.; Smolka, M. B. Multi-step control of homologous recombination via Mec1/ATR suppresses chromosomal rearrangements. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 3027–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivakovsky-Gonzalez, E.; Polleys, E.J.; Masnovo, C.; Cebrian, J.; Molina-Vargas, A.M.; Freudenreich, C.H.; Mirkin, S.M. Rad9-mediated checkpoint activation is responsible for elevated expansions of GAA repeats in CST-deficient yeast. Genetics 2021, 219(2), iyab125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paek, A.L.; Kaochar, S.; Jones, H.; Elezaby, A.; Shanks, L.; Weinert, T. Fusion of nearby inverted repeats by a replication-based mechanism leads to formation of dicentric and acentric chromosomes that cause genome instability in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 2861–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaochar, S.; Shanks, L.; Weinert, T. Checkpoint genes and Exo1 regulate nearby inverted repeat fusions that form dicentric chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 21605–21610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, K.; Datta, A.; Kolodner, R.D. Suppression of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements by S phase checkpoint functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 2001, 104, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.D.; Kolodner, R.D. Pathways and Mechanisms that Prevent Genome Instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2017, 206, 1187–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-Ruiz, M.; Lowndes, N.F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint is required for efficient repair of double strand breaks by non-homologous end joining. FEBS Lett. 2000, 467, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.K.; Kirchner, J.M.; Resnick, M.A. Requirement for end-joining and checkpoint functions, but not RAD52-mediated recombination, after EcoRI endonuclease cleavage of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998, 18, 1891–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, K.; Kolodner, R.D. Induction of genome instability by DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003, 2, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.N.; Zhao, X. Replication-Associated Recombinational Repair: Lessons from Budding Yeast. Genes (Basel) 2016, 17, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennaneach, V.; Kolodner, RD. Recombination and the Tel1 and Mec1 checkpoints differentially effect genome rearrangements driven by telomere dysfunction in yeast. Nat Genet. 2004, 36, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Smith, S.; Myung, K. Suppression of gross chromosomal rearrangements by yKu70-yKu80 heterodimer through DNA damage checkpoints. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Kolodner, R.D. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nat Genet. 1999, 23, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M.; Dave, P. Mating type regulates the radiation-associated stimulation of reciprocal translocation events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1994, 243, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M.; St Amour, C.; Zeng, L. Enhanced stimulation of chromosomal translocations and sister chromatid exchanges by either HO-induced double-strand breaks or ionizing radiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yku70 mutants. Mutat Res. 2005, 578, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.L.; Nakamura, T.M; Russell, P. Histone modification-dependent and -independent pathways for recruitment of checkpoint protein Crb2 to double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1583–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikley, E.J.; Tinline-Purvis, H.; Kasparek, T.R.; Marguerat, S.; Sarkar, S.; Hulme, L.; Hussey, S.; Wee, B.Y.; Deegan, R.S.; Walker, C.A.; Pai, C.C.; Bähler, J.; Nakagawa, T.; Humphrey, T.C. The DNA damage checkpoint pathway promotes extensive resection and nucleotide synthesis to facilitate homologous recombination repair and genome stability in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 5644–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarougkas, A.; Ismail, A.; Klement, K.; Goodarzi, A.A.; Conrad, S.; Freire, R.; Shibata, A.; Lobrich, M.; Jeggo, P.A. Opposing roles for 53BP1 during homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 9719–9731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Pinski, D.F.; Forsburg, S.L. Diploidy confers genomic instability in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2025, 230(2), iyaf078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspari, T.; Murray, J.M.; Carr, A.M. Cdc2-cyclin B kinase activity links Crb2 and Rqh1-topoisomerase III. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, D.; Lisby, M.; Rothstein, R. Genome-wide analysis of Rad52 foci reveals diverse mechanisms impacting recombination. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3(12), e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic Assay | DNA damaging agent and assay | rad9 phenotype1 | Ploidy specificity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrachromatid recombination | ||||

| SSA between homeologous repeats | HO-induced DSBs | Decreased | Haploid | [22] |

| SSA | HO-induced DSBs | NC | Haploid | [94] |

| Deletions at the rDNA locus | Spontaneous | Increased in orc1-4 mutants | Haploid | [92] |

| Sister chromatid recombination | ||||

| uSCR | Spontaneous | NC | Haploid | [82] |

| uSCR | X rays | Decreased | Haploid | [82] |

| uSCR | MMS | Decreased | Haploid | [82] |

| Equal SCR | 1-Sce1 induced break | Decreased | Haploid | [83] |

| Homolog recombination between heteroalleles | ||||

| Homolog recombination occurring between two heteroalleles | Spontaneous | Two-fold increase | Diploid | [101] |

| Allelic recombination | Spontaneous | MC | Diploid | [100,117] |

| Gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs) | ||||

| GCR | Spontaneous | Increased | Haploid | [119,123,127] |

| GCR | Spontaneous | Increased | Disome for VII | [117] |

| Recombination between repeats on non-homologous chromosomes | ||||

| Directed translocations | Spontaneous | Increased | Haploid and Diploid | [82] |

| Directed translocations | Radiation (X-ray, UV) | Increased | Diploid | [82] |

| Directed translocations | Topoisomerase Inhibitors | Increased | Diploid | [89] |

| Directed translocations | MMS | Increased | Diploid | [82,89] |

| Directed translocations | 4-NQO | No change | Diploid | [89] |

| Directed translocations | HO-induced breaks | No change | Diploid | [82] |

| Chromosoe III translocations | Spontaneous | Increased in orc1-4 mutants | Diploid | [104] |

| Ectopic Gene Conversion | Spontaneous | No Change | Haploid and Diploid Strain | Fasullo (unpublished) |

| Non-homologous end-joining between cohesive ends | ||||

| Chromosome Breaks | HO-induced breaks | Decrease | Haploid | [94,122] |

| Plasmid Breaks | pRS315 digested with BamH1 | Decrease | Haploid | [121] |

| Genotype | RAD52-Dependent Rearrangements | Gross Chromosomal Rearrangements (GCRs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| his3-repeat-directed translocations1 | CUP1 Copy Number Variation(CNV)2 | yel069c::URA3 CAN13 |

yel072w::URA3 CAN4 |

CenVII ade6 ADE3/ hxk2:CAN1 cenVII ADE6 ade3e. |

|

| WT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| rad9 | 7 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.9 | 23 |

| mrc1 | 4.1 | 2 | 19 | 4.2 | |

| rad53 sml1 | 10 | 1 | 27 | 16 | 42 |

| rad5 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 127 | 19 | 27 |

| rad27 | 2.1 | 1100 | 140 | ||

| rad52 | <0.1 | 0.08 | 126 | 0.6 | 73 |

| mec1-21 | 23 | ||||

| mec1-21 rad51 | 100 | ||||

| mec1 sml1 | 1 | 194 | 7.6 | 97 | |

| mec1 sml1 rad51 | 1271 | ||||

| Genotype of Single and Double Mutant | Recombination Assay | Ploidy | Fold Increase relative to WT1 | Fold Increase Compared to rad9 | Fold Increase Compared to single DNA metabolism mutant | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rad9 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 7 | 1 | NA | [82,100] |

| rad9 rad51 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 57 |

8 | 5.3 | [100] |

| rad9 rad55 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 77 | 11 | 6.2 | [100] |

| rad9 rad57 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 78 | 11 | 5.3 | [100] |

| rad9 rad54 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 55 | 8 | 24 | [100] |

| rad9 mre11 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 57 | 8 | 2 | [100] |

| rad9 mec1 | Directed translocations | Diploid | 6 | 1 | 0.3 | [100] |

| rad9 | GCR | Haploid | 6 | 1 | NA | [110] |

| rad9 sgs1 | GCR | Haploid | 213 (3%) | 37 | 9.7 | [110] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).