Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

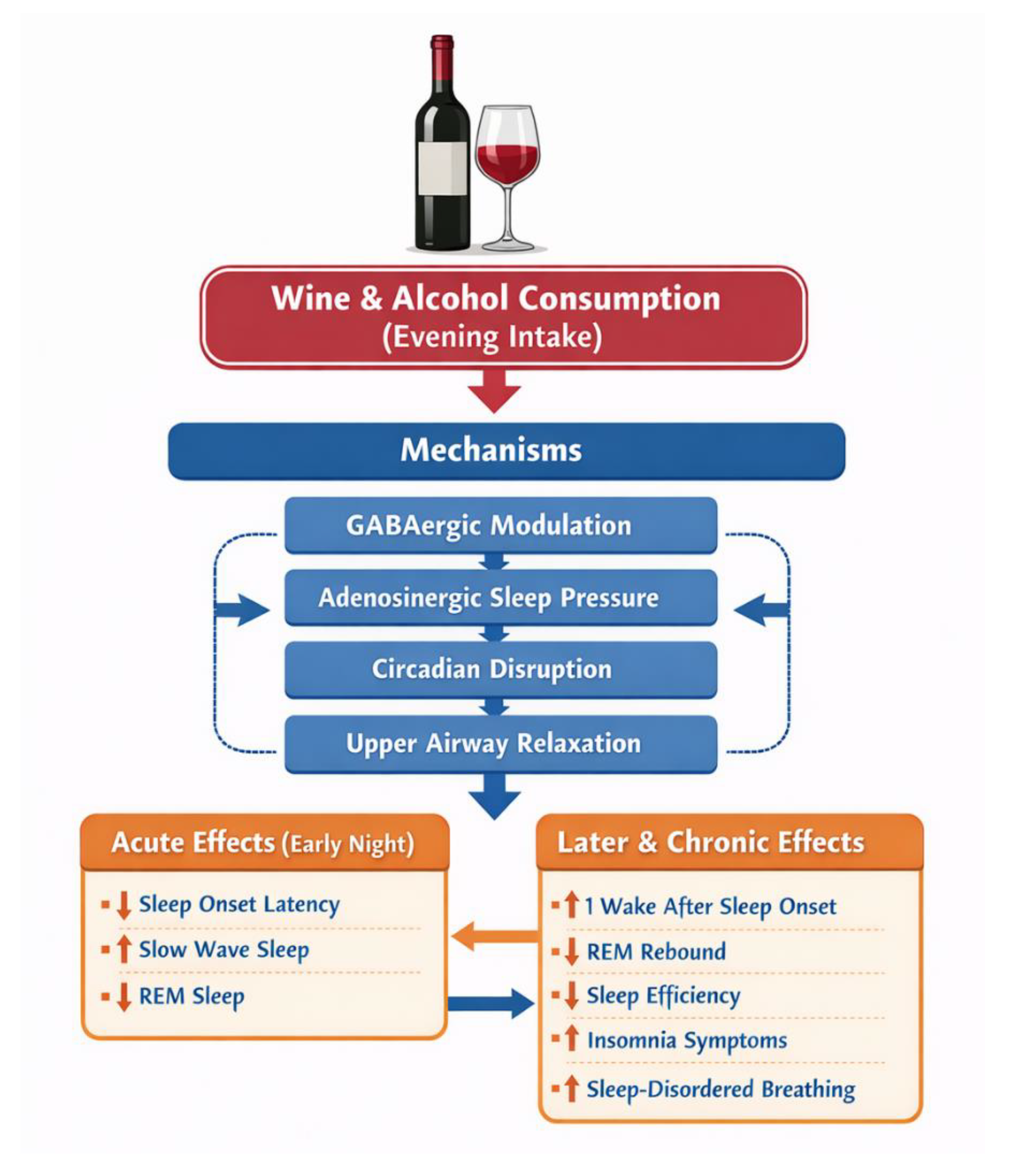

3. Acute Effects of Alcohol and Wine on Sleep

3.1. Sleep Initiation

3.2. Sleep Continuity and Fragmentation

3.3. Sleep Architecture

3.4. Key Recent Evidence on Alcohol and Sleep in Adults

4. Alcohol, Wine, and Sleep-Disordered Breathing

5. Chronic Alcohol Consumption, Insomnia, and Sleep Quality

6. Mechanisms Linking Alcohol to Sleep Disruption

7. Wine-Specific Considerations Within a Nutritional Context

7.1. Melatonin and Polyphenols

8. Effects of Sleep Patterns on Alcohol Consumption

9. Public Health and Clinical Implications

10. Future Research Directions

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| REM | Rapid eye movement |

References

- Bolling, C.; Cardoni, M.E.; Arnedt, J.T. Sleep and Substance Use: Exploring Reciprocal Impacts and Therapeutic Approaches. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2025, 27, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Weakley, J.; Burke, L.M.; Roach, G.D.; Sargent, C.; Maniar, N.; Huynh, M.; Miller, D.J.; Townshend, A.; Halson, S.L. The effect of alcohol on subsequent sleep in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2025, 80, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, H.E.; Badawi, J.C.; Schmitz, J.M.; Yoon, J.H.; Calvillo, D.J.; Becker, C.I.; Lane, S.D. Objective and subjective measurement of sleep in people who use substances: Emerging evidence and recommendations from a systematic review. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e14330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneo, D.; Bacaro, V.; Curati, S.; Russo, P.M.; Martoni, M.; Gelfo, F.; Baglioni, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between young adults’ sleep habits and substance use, with a focus on self-medication behaviours. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 70, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirtoli, R.; Mata, G.D.G.; Rodrigues, R.; Martinez-Vizcaíno, V.; López-Gil, J.F.; Guidoni, C.M.; Mesas, A.E. Is evening chronotype associated with higher alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chronobiol. Int. 2023, 40, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.J.; Soliman, P.S.; Rhew, R.; Cassidy, R.N.; Haass-Koffler, C.L. Disruption of circadian rhythms promotes alcohol use: a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2024, 59, agad083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Ma, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, L.; Cao, S. Alcohol consumption and incidence of sleep disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2020, 217, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inkelis, S.M.; Hasler, B.P.; Baker, F.C. Sleep and Alcohol Use in Women. Alcohol Res. 2020, 40, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Sanchez, C.; Jones, N.N.; Avillion, M.; Gibson, S.J.; Patel, J.A.; Neighbors, J.; Zaghi, S.; Camacho, M. Impact of Alcohol Consumption on Snoring and Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 163, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Colrain, I.M. Alcohol use disorder and sleep disturbances: a feed-forward allostatic framework. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K.; Peter, L.; Rodenbeck, A.; Weess, H.G.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Hillemacher, T. Shiftwork and Alcohol Consumption: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Eur. Addict. Res. 2021, 27, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhuenda, J.; Villaño, D.; Arcusa, R.; Zafrilla, P. Melatonin in Wine and Beer: Beneficial Effects. Molecules 2021, 26, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Hasler, B.P.; Chakravorty, S. Alcohol and sleep-related problems. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 30, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolla, B.P.; Foroughi, M.; Saeidifard, F.; Chakravorty, S.; Wang, Z.; Mansukhani, M.P. The impact of alcohol on breathing parameters during sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 42, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simou, E.; Britton, J.; Leonardi-Bee, J. Alcohol and the risk of sleep apnoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2018, 42, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, M.M.; Sharma, R.; Sahota, P. Alcohol disrupts sleep homeostasis. Alcohol. 2015, 49, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravorty, S.; Chaudhary, N.S.; Brower, K.J. Alcohol Dependence and Its Relationship With Insomnia and Other Sleep Disorders. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 2271–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colrain, I.M.; Nicholas, C.L.; Baker, F.C. Alcohol and the sleeping brain. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014, 125, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrs, T.; Zwyghuizen-Doorenbos, A.; Knox, M.; Moskowitz, H.; Roth, T. Sedating effects of ethanol and time of drinking. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1992, 16, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, I.O.; Shapiro, C.M.; Williams, A.J.; Fenwick, P.B. Alcohol and sleep I: effects on normal sleep. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, K.J.; Hoffmann, R.; Conroy, D.A.; Arnedt, J.T.; Armitage, R. Sleep homeostasis in alcohol-dependent, depressed and healthy control men. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 261, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnedt, J.T.; Rohsenow, D.J.; Almeida, A.B.; Hunt, S.K.; Gokhale, M.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Howland, J. Sleep following alcohol intoxication in healthy, young adults: effects of sex and family history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasler, B.P.; Pedersen, S.L. Sleep and circadian risk factors for alcohol problems: a brief overview and proposed mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 34, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwell, E.E.; Bujarski, S.; Glasner-Edwards, S.; Ray, L.A. The Association of Alcohol Severity and Sleep Quality in Problem Drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015, 50, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.W.; Ai, S.Z.; Chang, S.H.; Meng, S.Q.; Shi, L.; Deng, J.H.; Di, T.Q.; Liu, W.Y.; Chang, X.W.; Yue, J.L.; Yang, X.Q.; Zeng, N.; Bao, Y.P.; Sun, Y.; Lu, L.; Shi, J. Association between alcohol consumption and sleep traits: observational and mendelian randomization studies in the UK biobank. Mol. Psychiatry. 2024, 29, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, P.; Härmä, M.; Ojajärvi, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Leineweber, C.; Oksanen, T.; Salo, P.; Vahtera, J. Association of rotating shift work schedules and the use of prescribed sleep medication: A prospective cohort study. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, A; Karpyak, V.M. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2015, 156, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, H.P. Sleep homeostasis: a role for adenosine in humans? Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 75, 2070–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yao, M.; Li, Y.; Cao, K.; Deng, Y. Association of alcohol consumption with sleep disturbance among adolescents in China: a cross-sectional analysis. Front. Public Health. 2025, 13, 1564292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, B.P.; Schulz, C.T.; Pedersen, S.L. Sleep-Related Predictors of Risk for Alcohol Use and Related Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. Alcohol Res. 2024, 44, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazdowski, T.K.; Kelly, L.; Livingston, N.R.; Sheidow, A.J.; McCart, M.R. Within-Person Bidirectional Relations Between Sleep Problems and Alcohol, Cannabis, and Co-Use Problems in a Representative U.S. Sample. Subst. Use Misuse. 2025, 60, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helaakoski, V.; Zellers, S.; Hublin, C.; Ollila, H.M.; Latvala, A. Associations between sleep medication use and alcohol consumption over 36 years in Finnish twins. Alcohol. 2025, 124, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, J.; Ling, L.; Alonzo, R.T.; Rodrigues, R.; Nicholson, K.; Stranges, S.; Anderson, K.K. Associations between sleep patterns, smoking, and alcohol use among older adults in Canada: Insights from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Addict. Behav. 2022, 132, 107345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, A.J.; Hellard, D.W.; Slayton, P.C. Minimal effect of alcohol ingestion on breathing during the sleep of postmenopausal women. Chest. 1985, 88, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strüven, A.; Schlichtiger, J.; Hoppe, J.M.; Thiessen, I.; Brunner, S.; Stremmel, C. The Impact of Alcohol on Sleep Physiology: A Prospective Observational Study on Nocturnal Resting Heart Rate Using Smartwatch Technology. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Smith, D. Ingestion of ethanol just prior to sleep onset impairs memory for procedural but not declarative tasks. Sleep 2003, 26, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, B.; Gann, H.; Brueck, R.; Hornyak, M.; Litsch, S.; Hohagen, F.; Riemann, D. Effects of alcohol on polysomnographically recorded sleep in healthy subjects. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 30, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D.A.; Arnedt, J.T. Sleep and substance use disorders: an update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geoffroy, P.A.; Lejoyeux, M.; Rolland, B. Management of insomnia in alcohol use disorder. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 21, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Trinder, J.; Andrewes, H.E.; Colrain, I.M.; Nicholas, C.L. The acute effects of alcohol on sleep architecture in late adolescence. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullar, K.S.; Barker, D.H.; McGeary, J.E.; Saletin, J.M.; Gredvig-Ardito, C.; Swift, R.M.; Carskadon, M.A. Altered sleep architecture following consecutive nights of presleep alcohol. Sleep 2024, 47, zsae003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabon, E.; Greenlund, I.M.; Carter, J.R.; de Wit, H. Effects of alcohol on sleep and nocturnal heart rate: Relationships to intoxication and morning-after effects. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 46, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payseur, D.K.; Belhumeur, J.R.; Curtin, L.A.; Moody, A.M.; Collier, S.R. The effect of acute alcohol ingestion on systemic hemodynamics and sleep architecture in young, healthy men. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, M.W.; Martinez, C.E.; Wong, M.M.; Pearson, M.R.; Protective Strategies Study Team. Sleep disturbances relate to problematic alcohol use via effortful control and negative emotionality. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. (Hoboken) 2025, 49, 1554–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorrian, J.; Heath, G.; Sargent, C.; Banks, S.; Coates, A. Alcohol use in shiftworkers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 99, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehrs, T.; Papineau, K.; Rosenthal, L.; Roth, T. Ethanol as a hypnotic in insomniacs: self administration and effects on sleep and mood. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999, 20, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.J.; Troost, J.P.; Rizvydeen, M.; Kikyo, F.; Kebbeh, N.; Tan, M.; Roecklein, K.A.; King, A.C.; Hasler, B.P. Do sleep and circadian characteristics predict alcohol use in adult drinkers? Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. (Hoboken) 2024, 48, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, B.P.; Clark, D.B. Circadian misalignment, reward-related brain function, and adolescent alcohol involvement. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grao-Cruces, E.; Calvo, J.R.; Maldonado-Aibar, M.D.; Millan-Linares, M.D.C.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S. Mediterranean Diet and Melatonin: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbería-Latasa, M.; Martínez-González, M.A. The Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 2465–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year) | Design | Population | Exposure | Sleep Outcomes Assessed | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gardiner et al. (2025) [2] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Healthy adults | Acute alcohol intake | Sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, REM sleep, slow-wave sleep | Alcohol reduced sleep onset latency but increased wake after sleep onset and reduced sleep efficiency; REM sleep was suppressed early with rebound later in the night |

| Webber et al. (2025) [3] | Systematic review | Adults | Alcohol use | Objective and subjective sleep measures | Subjective sleep improvements often conflicted with objective measures; alcohol was consistently associated with sleep fragmentation |

| Meneo et al. (2023) [4] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Young and middle-aged adults | Sleep habits and substance use | Sleep disturbances (insomnia symptoms, sleep quality), sleep health dimensions (duration, satisfaction, efficiency, timing, daytime alertness), and circadian characteristics (chronotype) | Poor sleep habits were associated with greater alcohol use, supporting self-medication and bidirectional pathways |

| Hu et al. (2020) [7] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies | General adult population | Habitual alcohol consumption | Incident sleep disorders | Regular alcohol consumption was associated with increased risk of developing sleep disorders over time |

| Burgos-Sanchez et al. (2020) [9] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Adults | Alcohol consumption | Snoring, sleep architecture, apnea–hypopnea index | Alcohol consumption significantly increased snoring and obstructive sleep apnea severity |

| Kolla et al. (2018) [14] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Adults | Alcohol consumption | Breathing parameters during sleep | Alcohol worsened nocturnal oxygen desaturation and increased respiratory event duration |

| Simou et al. (2018) [15] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Adults | Alcohol consumption | Sleep apnea risk | Alcohol consumption was associated with an increased risk of sleep apnea |

| Bolling et al. (2025) [1] | Narrative review | Adults | Alcohol use | Sleep quality, insomnia symptoms | Alcohol and sleep disruption showed reciprocal effects; short-term sedative effects masked longer-term impairment |

| Inkelis et al. (2020) [8] | Narrative review | Adult women | Alcohol use | Insomnia symptoms, sleep quality | Women experienced greater sleep disruption at lower alcohol doses than men |

| Marhuenda et al. (2021) [12] | Narrative review | Adults | Wine (melatonin and polyphenols) | Sleep and circadian regulation | Melatonin and polyphenol content in wine was far below doses required to influence sleep; no evidence of meaningful sleep benefit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).