Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

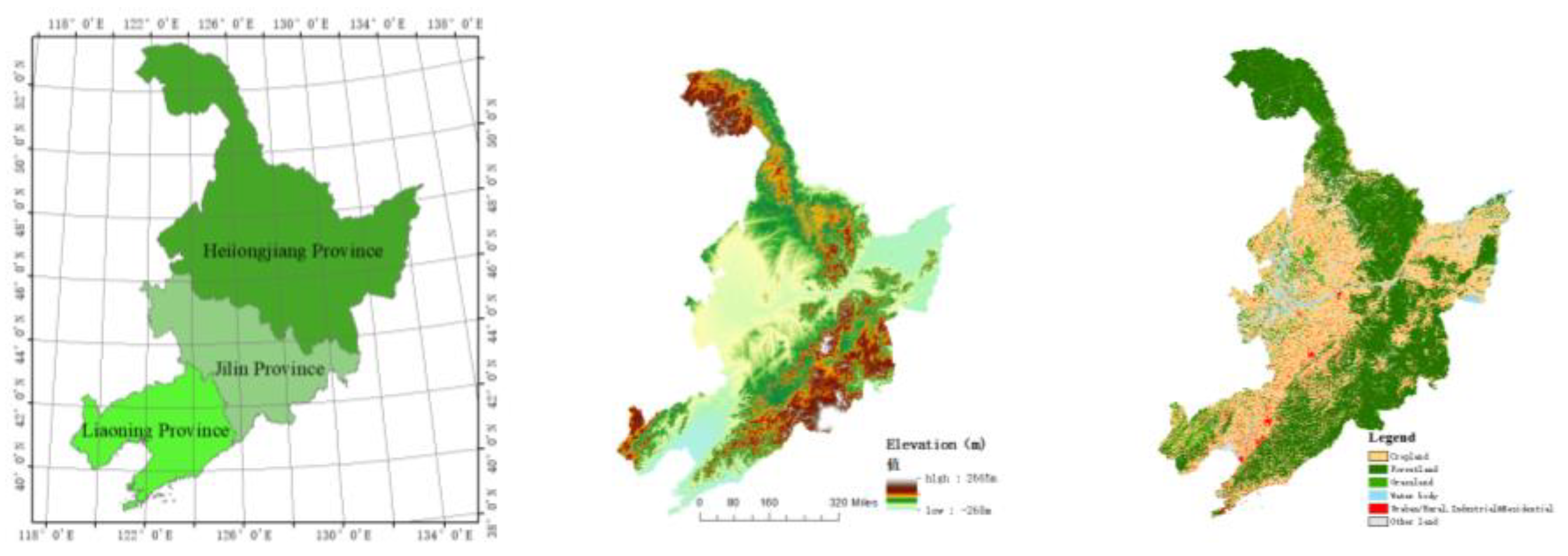

2. Overview of the Study Area and Data Sources

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Selection of Indicators and Data Sources

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Entropy Weight Method

3.2. Comprehensive Security Index

3.3. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

3.4. Obstacle Degree Model

4. Results and Analysis

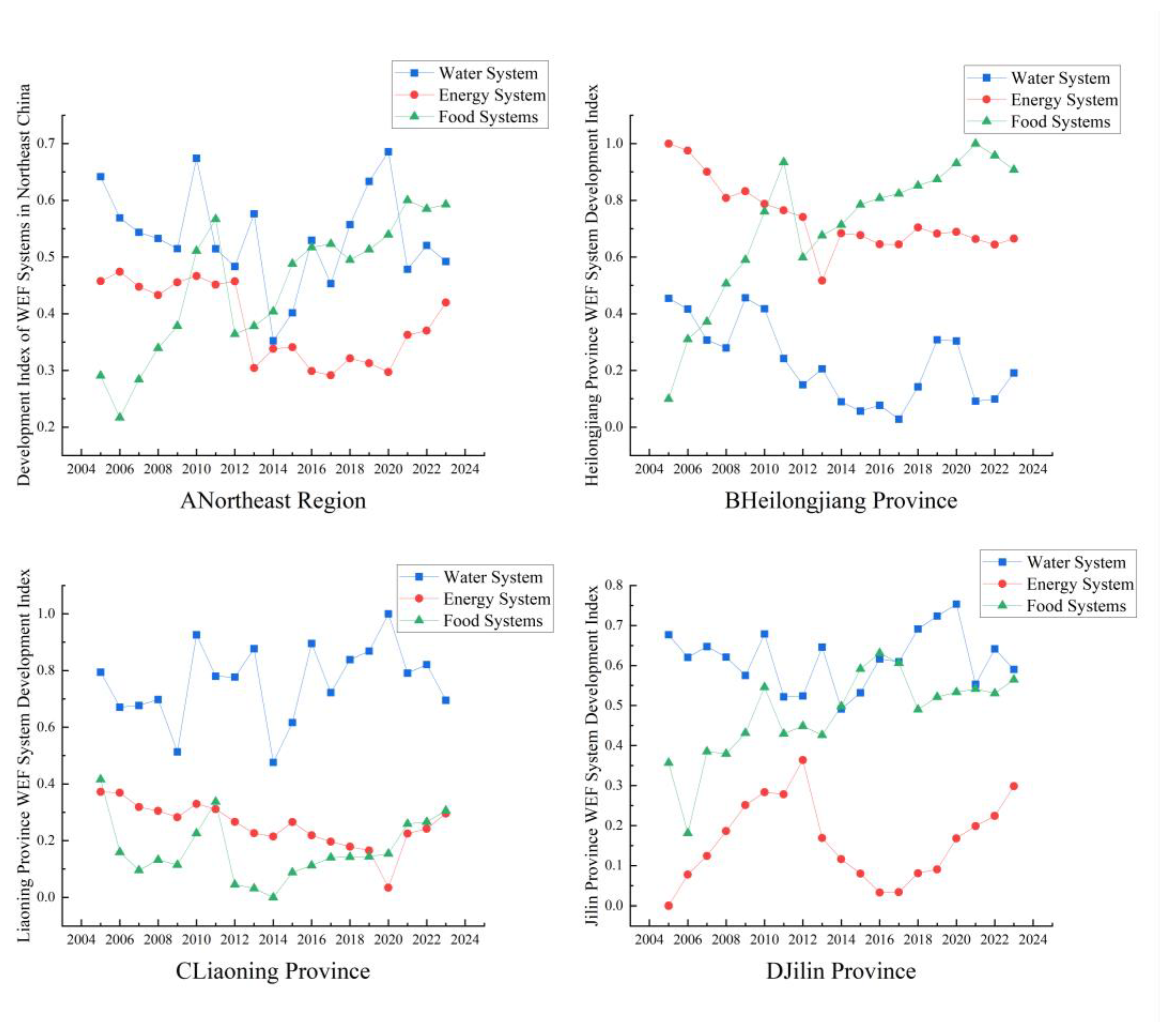

4.1. Development Level of the WEF Security System in Northeast China

4.1.1. Analysis of the Comprehensive Development Level

4.1.2. Analysis of Development Levels Across WEF Security Subsystems

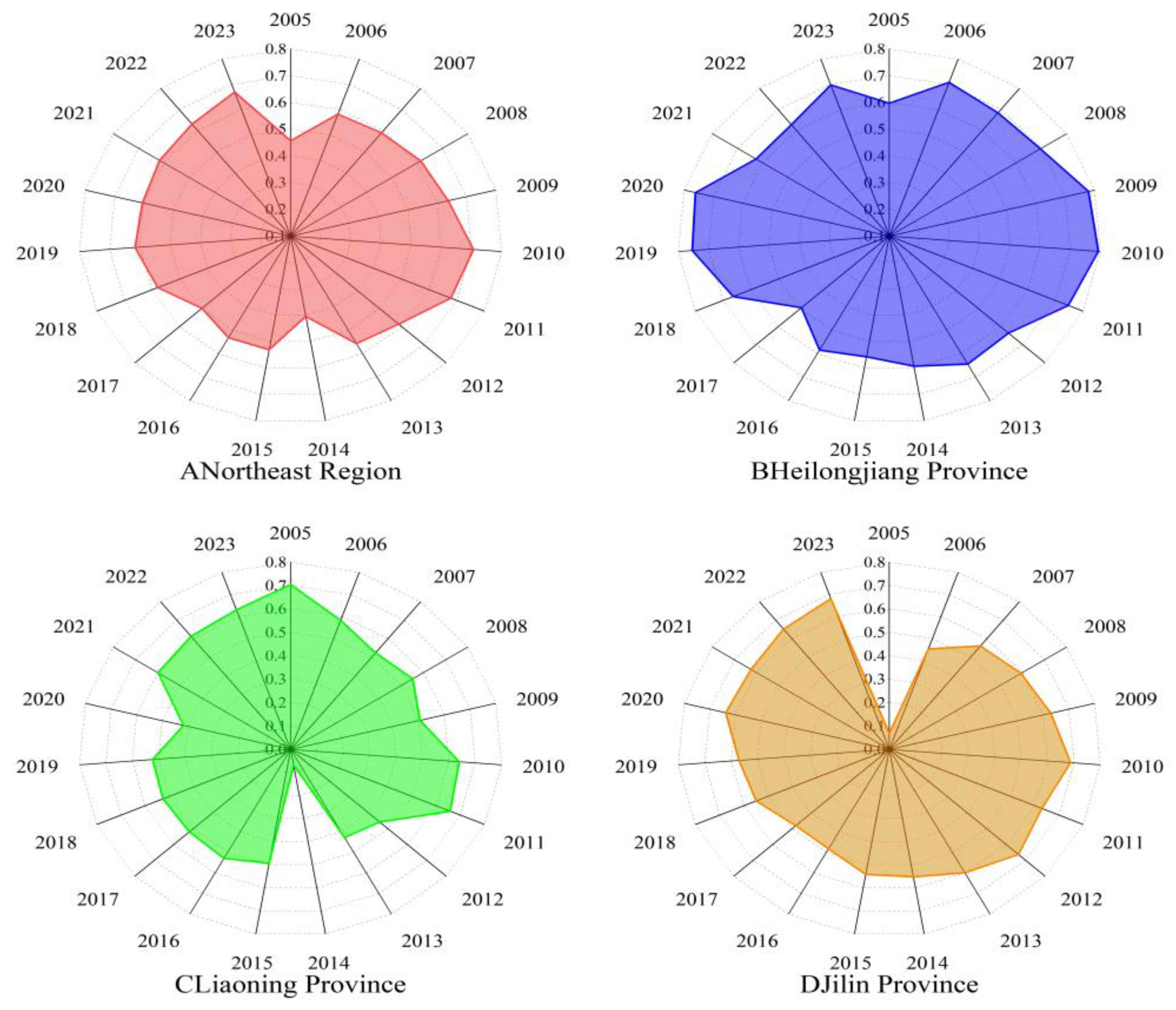

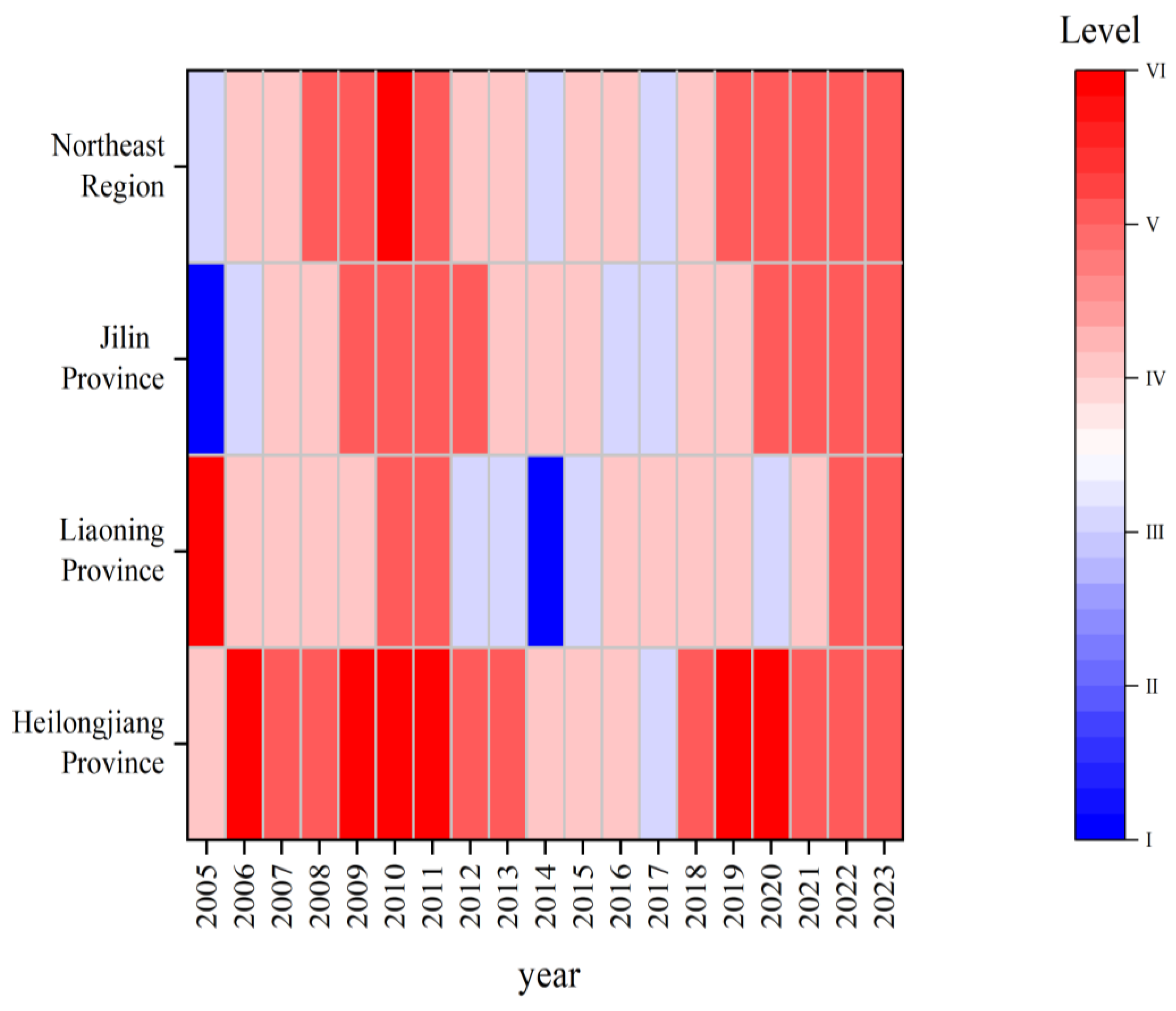

4.2. Coupling Coordination Analysis of the WEF Security System in Northeast China

4.2.1. Analysis of Coupling Coordination Degree

4.2.2. Analysis of Coupling Coordination Degree Levels

4.3. Research on Obstacle Factors Affecting the Coordinated Development of the WEF Security System in Northeast China

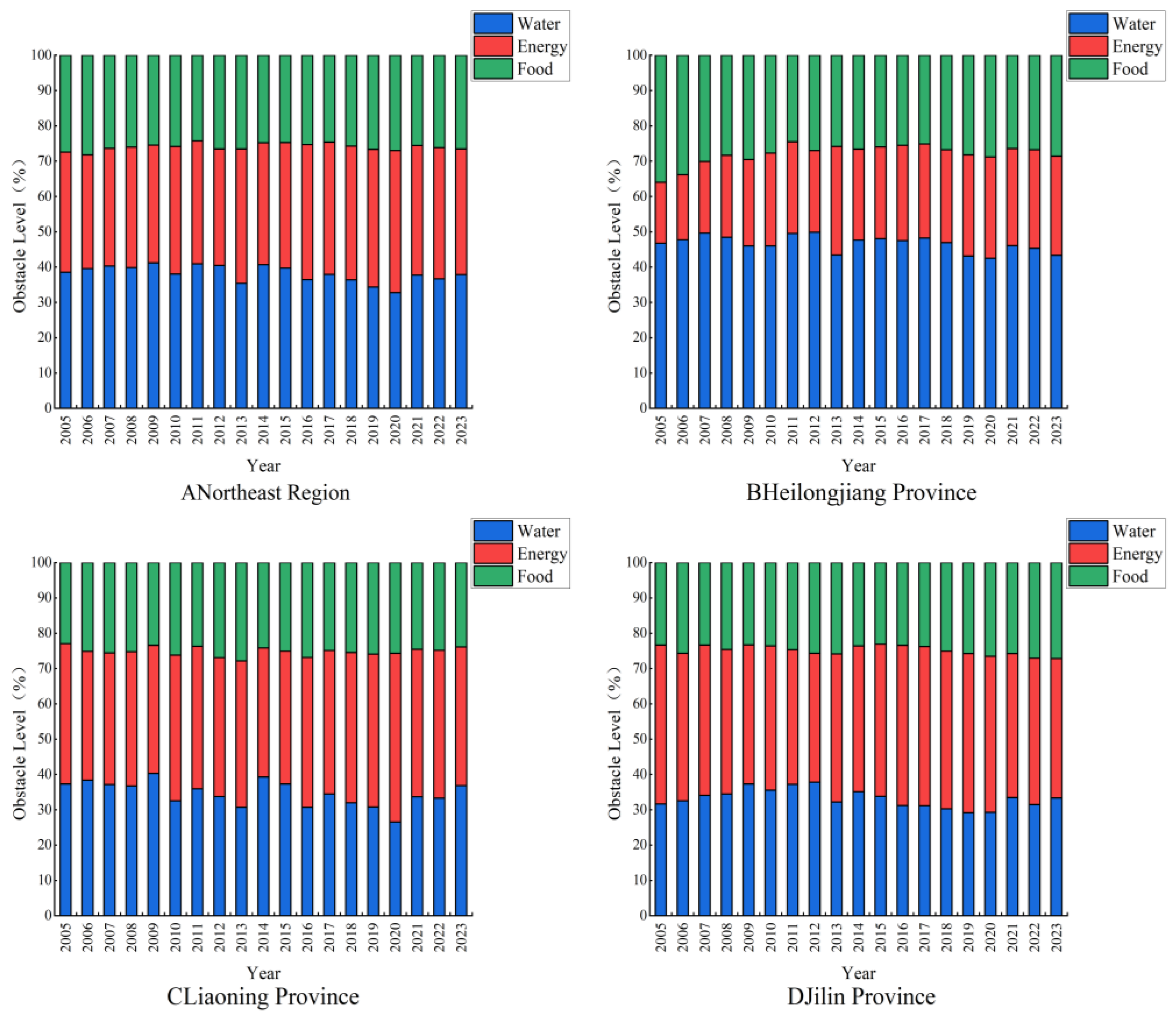

4.3.1. Analysis of Obstacle Factors at the System Level

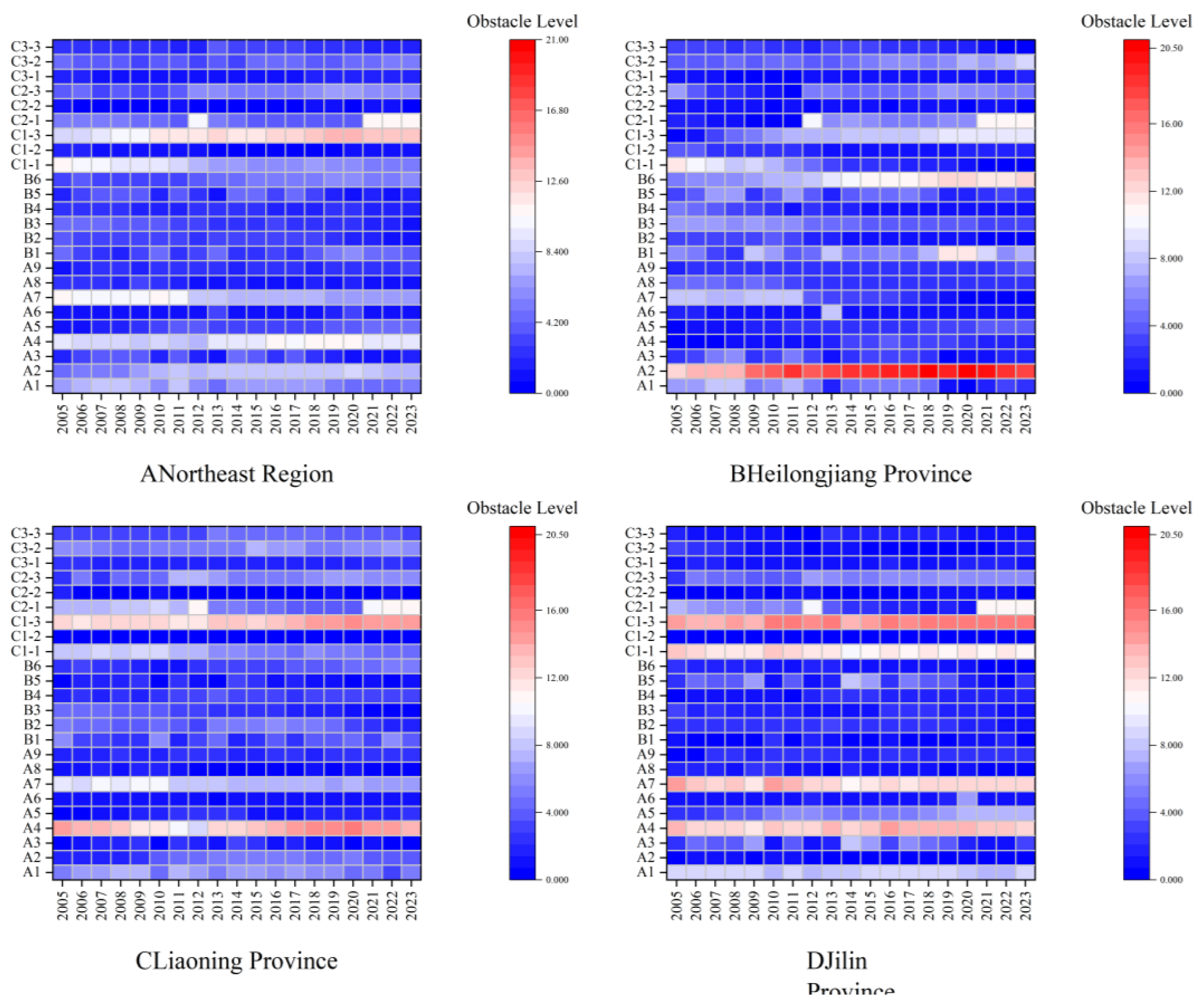

4.3.2. Analysis of Obstacle Factors at the Indicator Level

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, Y.; Li, G.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, C. Quantifying the water-energy-food nexus: Current status and trends. Energies 2016, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DP, U. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division, DVD edn 2015.

- Flammini, A.; Puri, M.; Pluschke, L.; Dubois, O. Walking the nexus talk: assessing the water-energy-food nexus in the context of the sustainable energy for all initiative; 2014.

- Mountford, H. Water: The environmental outlook to 2050. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the OECD Global Forum on Environment: Making Water Reform Happen, Paris, France, 2011; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, B. Water-energy-food nexus: challenges and opportunities. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2021, 35, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiying, A.; Caizhi, S.; Shuai, H. Supply-demand matching relationship of ecosystem services in Northeast our country: from the perspective of water-energy-food linkage. Acta Ecology 2024, 44, 4170–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, H. Understanding the nexus. background paper for the bonn2011 nexus conference: the water, energy and food security nexus. 2011.

- Zongyong, Z.; Junguo, L.; Kai, W.; Zhan, T.; Dandan, Z. Review of Water-Food-Energy Linkage System: Bibliometric and Analysis. Scientific Bulletin 2020, 65, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Smajgl, A.; Ward, J.; Pluschke, L. The water–food–energy Nexus–Realising a new paradigm. Journal of hydrology 2016, 533, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, S.; He, G.; Li, R.; Wang, X. Evaluating sustainability of water-energy-food (WEF) nexus using an improved matter-element extension model: A case study of China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 202, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuechun, H.; Zhiqiang, W.; Li, L.; Yi, W.; Peng, W. Research on Safety Evaluation and Identification of Obstacles to the “Water-Energy-Food” Systemin the Western Region. Chinese Journal of Agricultural Machinery and Chemistry 2023, 44, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bi, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y. Research Progress on Risk Management Based on Food-Energy-Water Relationship. Chinese Population, Resources and Environment 2018, 28, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chunfeng, H.; Cheng, Z.; Haiying, L.; Yaqin, Q. Quantitative Analysis and Risk Analysis of Water-Energy-Food Synergy Security in Northeast China. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Water Conservancy Conference (2022 Annual Conference of China Water Conservancy Society), Beijing, China, 2022; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, C.; Yang, S.; Fan, Y.; Wu, H.; Gong, C. Coupling efficiency assessment of food–energy–water (FEW) nexus based on urban resource consumption towards economic development: the case of Shenzhen Megacity, China. Land 2022, 11, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengshuang, S.; Haohao, S. Research on water-energy-food input-output efficiency based on DEA model. Journal of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture 2021, 37, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. European journal of operational research 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangang, G.; Jinlu, L.; Kai, X.; Lina, H. Research on the efficiency of water-energy-food link system in the Yellow River Basin. People’s Yellow River 2024, 46, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, E.; Feng, G.; Qu, B.; Hao, L.; Li, J.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Water–Energy–Food Synergistic Efficiency: A Case Study of Irrigation Districts in the Lower Yellow River. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Qu, S.; Jin, Y.; Tang, X.; Liang, S.; Chiu, A.S.; Xu, M. Uncovering urban food-energy-water nexus based on physical input-output analysis: The case of the Detroit Metropolitan Area. Applied Energy 2019, 252, 113422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M.; Al-Ansari, T.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Quantifying the energy, water and food nexus: A review of the latest developments based on life-cycle assessment. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 193, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Qu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Daigger, G.T.; Newell, J.P.; Miller, S.A.; Johnson, J.X.; Love, N.G.; Zhang, L. Quantifying the urban food–energy–water nexus: the case of the detroit metropolitan area. Environmental science & technology 2018, 53, 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Shibao, L.; Fan, Z.; Liang, P.; Weisheng, D.; Yangang, X. Water Resources Security in our country’s Five Typical Areas from the Perspective of Energy-Food Relationship. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Wallington, K.; Shafiee-Jood, M.; Marston, L. Understanding and managing the food-energy-water nexus–opportunities for water resources research. Advances in Water Resources 2018, 111, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Li, G.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, C. Quantifying the water-energy-food nexus: Current status and trends. Energies 2016, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.; Liu, G.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liang, S.; Asamoah, E.F.; Lombardi, G.V. Urban food-energy-water nexus indicators: A review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 151, 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.N.; Kenway, S.J.; Renouf, M.A.; Lam, K.L.; Wiedmann, T. A review of the water-related energy consumption of the food system in nexus studies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 279, 123414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejnowicz, A.; Thorn, J.; Giraudo, M.; Sallach, J.; Hartley, S.; Grugel, J.; Pueppke, S.; Emberson, L. Appraising the water-energy-food nexus from a sustainable development perspective: a maturing paradigm? Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittock, J.; Hussey, K.; McGlennon, S. Australian climate, energy and water policies: conflicts and synergies. Australian Geographer 2013, 44, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, E.; Martin, D.A. Learning from past coevolutionary processes to envision sustainable futures: Extending an action situations approach to the Water-Energy-Food nexus. Earth system governance 2023, 15, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longzai, Y.; Huixiao, W.; Yating, H.; Wendi, C.; Hongfang, L.; Guanhang, S. Research on the collaborative security and coupling coordination of water-energy-food system in the Inner Mongolia section of the Yellow River Basin. In South-to-North Water Diversion and Water Conservancy Science and Technology; pp. 1–14.

- Longzai, Y.; Huixiao, W.; Yating, H.; Wendi, C.; Hongfang, L.; Guanhang, S. Research on the collaborative security and coupling coordination of water-energy-food system in the Inner Mongolia section of the Yellow River Basin. South-to-North Water Diversion and Water Conservancy Science and Technology 2024, 22, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caizhi, S.; Yongjie, W.; Wenxin, L. Water poverty evaluation and obstacle factor analysis in Dalian based on entropy-weighted TOPSIS method. Water resources protection 2017, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Yang, F.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C. Quantization of the coupling mechanism between eco-environmental quality and urbanization from multisource remote sensing data. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 321, 128948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, B.; Shen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Su, B.; Yin, Q.; Zhou, S. Coupling coordination evaluation of ecology and economy and development optimization at town-scale. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 447, 141581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinlei, C.; Chenyue, X. Differences and obstacles to the coordinated development of food-ecology-energy security in the Yellow River Basin. In China’s agricultural resources and zoning; pp. 1–16.

- Libing, Z.; Chuanyu, K.; Juliang, J.; Yachao, B.; Qibing, Z.; Xiaofeng, C. Research on the coupling coordination and optimization of water-energy-food system in rice irrigation area under bilateral regulation of supply and demand. Journal of Water Resources 2023, 54, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yijia, H.; Yong, X.; Yang, Z.; Xiandong, L. Spatio-temporal dynamics and predictive analysis of water-energy-food system coupling and coordinated development in Northwest China. Soil and water conservation 2025, 32, 251–259+269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongfang, L.; Huixiao, W.; Ruxin, Z.; Yaxue, Y.; Jiahao, G. Water-energy-food symbiosis security risk probability based on Copula function. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE) 2021, 37, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Chengyu, L.; Shiqiang, Z. Coordination degree and influencing factors of water-energy-food coupling in China. Chinese population, resources and environment 2020, 30, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yali, C.; Qiang, Z.; Mingle, A.; Xiumei, L.; Pengyu, R. Analysis of spatio-temporal characteristics of meteorological drought in the Liao River Basin from 1959 to 2019. Water conservancy and hydropower technology (Chinese and English) 2023, 54, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunyang, L.; Feng, W.; Qingyuan, Y.; Linlin, C.; Huiming, Z. Urban Land Use Performance Evaluation and Obstacle Factor Diagnosis Based on Improved TOPSIS Method: A Case Study of Chongqing. Resource Science 2011, 33, 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Liangliang, Y.; Yinying, C. Performance evaluation and diagnosis of obstacle factors of economic compensation policy for cultivated land protection based on farmers’ satisfaction. Journal of Natural Resources 2015, 30, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar]

| Criterion Layer | Primary Indicator Layer | Secondary Indicator Layer | Formula/Unit | Direction | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security | Water Resources Subsystem | A1: Per Capita Water Resources | Total water resources / Permanent population (m³/person) | + | 0.046 |

| Water Resources Subsystem | A2: Per Capita Water Use | Total water use / Permanent population (m³/person) | – | 0.095 | |

| Water Resources Subsystem | A3: Water Resource Development & Utilization Rate | Total water use / Total water resources (%) | – | 0.043 | |

| Energy Subsystem | A4: Per Capita Energy Production | Total energy production / Permanent population (tce/person) | + | 0.076 | |

| Energy Subsystem | A5: Per Capita Energy Consumption | Total energy consumption / Permanent population (tce/person) | – | 0.035 | |

| Energy Subsystem | A6: Elasticity Coefficient of Energy Consumption | Growth rate of energy consumption / Growth rate of GDP (%) | – | 0.041 | |

| Food Subsystem | A7: Per Capita Cultivated Land Area | Cultivated land area / Permanent population (m²/person) | + | 0.064 | |

| Food Subsystem | A8: Grain Yield per Unit Area | Total grain output / Sown area of grain crops () | + | 0.020 | |

| Food Subsystem | A9: Grain Output Fluctuation Rate | | (Actual output in year t – Trend output in year t) / Trend output in year t | (%) | – | 0.019 | |

| Coordination | Water-Energy Nexus | B1: Water Consumption per Unit GDP | Total water use / GDP (m³/10⁴ CNY) | – | 0.052 |

| Water-Energy Nexus | B2: Water Consumption per Unit Energy Production | Industrial water use / Total energy production() | – | 0.030 | |

| Energy-Food Nexus | B3: Total Agricultural Machinery Power per Unit Area | Total power of agricultural machinery / Total sown area of crops () | + | 0.029 | |

| Energy-Food Nexus | B4: Proportion of Effective Irrigated Area | Effective irrigated area / Cultivated land area (%) | + | 0.021 | |

| Water-Food Nexus | B5: Proportion of Agricultural Water Use | Agricultural water use / Total water use (%) | – | 0.043 | |

| Water-Food Nexus | B6: Water Consumption per Unit Grain Output | Agricultural water use / Total grain output () | – | 0.055 | |

| Resilience | Coping Capacity | C1-1: Per Capita Grain Availability | Total grain output / Permanent population (kg/person) | + | 0.060 |

| Coping Capacity | C1-2: Total Reservoir Storage Capacity | (10⁸ m³) | + | 0.015 | |

| Coping Capacity | C1-3: Energy Self-Sufficiency Rate | Total energy production / Total energy consumption (%) | + | 0.078 | |

| Recovery Capacity | C2-1: Proportion of Water-Saving Irrigated Area | Water-saving irrigated area / Effective irrigated area (%) | + | 0.052 | |

| Recovery Capacity | C2-2: Growth Rate of Rural Electricity Consumption | (Current year’s consumption – Previous year’s consumption) / Previous year’s consumption (%) | + | 0.010 | |

| Recovery Capacity | C2-3: Multiple Cropping Index | Total sown area of crops / Cultivated land area (%) | + | 0.036 | |

| Adaptive Capacity | C3-1: Comprehensive Agricultural Mechanization Level | Mechanized plowing area / Cultivated land area (%) | + | 0.014 | |

| Adaptive Capacity | C3-2: Proportion of Coal Consumption | Coal consumption / Total energy consumption (%) | – | 0.041 | |

| Adaptive Capacity | C3-3: Area of Soil Erosion Control | (10⁴ hm²) | + | 0.025 |

| Coupling Coordination Degree (D) | Coordination Level | Coupling Degree Stage |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00 ≤ D < 0.20 | Extreme Dysfunction (I) | Low-Level Coupling |

| 0.20 ≤ D < 0.40 | Severe Dysfunction (II) | Low-Level Coupling |

| 0.40 ≤ D < 0.50 | Near Dysfunction (III) | Antagonistic Stage |

| 0.50 ≤ D < 0.60 | Primary Coordination (IV) | Running-in Stage |

| 0.60 ≤ D < 0.70 | Intermediate Coordination (V) | Running-in Stage |

| 0.70 ≤ D < 0.80 | Good Coordination (VI) | Running-in Stage |

| 0.80 ≤ D < 0.90 | High-Quality Coordination (VII) | High-Level Coupling |

| 0.90 ≤ D ≤ 1.00 | Superior Coordination (VIII) | High-Level Coupling |

| Province | Heilongjiang | Liaoning | Jilin | Regional Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 0.518 | 0.527 | 0.345 | 0.463 |

| 2006 | 0.567 | 0.399 | 0.293 | 0.420 |

| 2007 | 0.526 | 0.363 | 0.386 | 0.425 |

| 2008 | 0.531 | 0.378 | 0.396 | 0.435 |

| 2009 | 0.626 | 0.303 | 0.419 | 0.450 |

| 2010 | 0.655 | 0.494 | 0.503 | 0.550 |

| 2011 | 0.647 | 0.476 | 0.410 | 0.511 |

| 2012 | 0.496 | 0.363 | 0.445 | 0.435 |

| 2013 | 0.466 | 0.378 | 0.414 | 0.419 |

| 2014 | 0.495 | 0.230 | 0.368 | 0.365 |

| 2015 | 0.506 | 0.323 | 0.401 | 0.410 |

| 2016 | 0.510 | 0.409 | 0.427 | 0.448 |

| 2017 | 0.499 | 0.353 | 0.416 | 0.423 |

| 2018 | 0.566 | 0.386 | 0.421 | 0.458 |

| 2019 | 0.622 | 0.392 | 0.445 | 0.486 |

| 2020 | 0.641 | 0.396 | 0.485 | 0.507 |

| 2021 | 0.585 | 0.425 | 0.431 | 0.480 |

| 2022 | 0.567 | 0.443 | 0.466 | 0.492 |

| 2023 | 0.588 | 0.432 | 0.484 | 0.501 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).