1. Introduction: A Perspective on Phenomenological Approaches to Dark Energy

1.1. The Current Cosmological Landscape

The standard ΛCDM cosmological model is facing significant empirical challenges, with growing evidence suggesting that dark energy sector may possess dynamical properties. Latest observational datasets such as DESI DR2, Pantheon+, DES Y5, and DECADE indicate that the equation of state parameter

w of dark energy is not constantly equal to -1, but rather evolves with cosmological redshift

z. Notably,

w(

z) exhibits Quintom-like behavior of crossing

w = -1 in the redshift range

z ~ 0.5-1.5 [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This not only poses a severe challenge to the ΛCDM model but also strongly suggests that dark energy possesses complex dynamical properties, potentially interacting with other cosmic components.

Simultaneously, the ΛCDM model confronts two major cosmological tensions. The Hubble tension—the discrepancy between early-universe and late-universe measurements of the expansion rate—now exceeds the 5

σ significance level [

5,

6]. The

S₈ tension, which reflects a mismatch in the amplitude of matter clustering inferred from the cosmic microwave background and from contemporary weak lensing surveys, persists at the 2-3

σ level [

7,

8]. These persistent discrepancies suggest that either unknown systematics affect multiple independent measurements, or that new physics beyond the standard cosmological constant is required.

Based on the latest research findings, we put forward a question: Where does this dynamism of dark energy originate? We hypothesize that, since the cosmological redshift z is not only a yardstick for spacetime expansion but also a clock for the history of cosmic structure formation, the specific evolutionary law of dark energy with z may reflect an inherent coupling relationship between dark energy and cosmic structure growth that evolves with cosmic time (i.e., redshift).

Zhao’s recent research posits the universe as a framework-based adaptive ecosystem, wherein the cosmic framework is jointly formed by spacetime (as a structural entity), dark matter (as a gravitational structure), and dark energy (as a functional core) [

9,

10]. Cosmic ecology corresponds to the dynamic evolutionary behaviours that operate on this underlying framework [

9,

10]. The adaptive universe framework proposed a fundamental shift in perspective: rather than treating dark energy as a passive background component, it suggested that dark energy dynamics correlate intrinsically with structure growth through a linear

w-

γ relation [

9,

10]. In other words, the state of dark energy may be modulated by the cosmic matter environment, which is characterized by its growth index γ(z).

In this Perspective, building upon the compelling observational hints for dynamical dark energy and Zhao’s proposal that its dynamics intrinsically correlate with structure growth through a linear w-γ relation, we further explore this correlational framework by developing a complete phenomenological model and testing roadmap.

1.2. This Perspective: From Concept to Testing Roadmap

This article presents a comprehensive perspective on one specific phenomenological direction: the correlation between dark energy equation of state w and structure growth index γ. Unlike traditional research papers reporting completed analyses, this Perspective article does the following: it articulates and develops a complete theoretical framework based on the w-γ correlation concept; provides specific, testable model implementations from simple to complex; details a complete methodology for empirical testing with current and future data; offers quantitative forecasts for detectability with upcoming surveys; and places this approach in context with other proposed solutions to cosmological tensions.

2. Foundational Framework: The Linear w-γ Correlation

2.1. Core Phenomenological Relation

The starting point of our framework is the linear correlation proposed in recent work on the “adaptive universe” concept [

9,

10]:

Equation (1) introduces three key quantities:

w(

a) denotes the dark energy equation of state parameter;

γ(

a) is the growth index, defined via the growth rate

f(

a)≡dln

δm/dln

a=

Ωm(

a)

γ(a); and

η is a dimensionless constant quantifying the correlation strength between them. The offset value 0.55 corresponds to the approximate growth index in the standard ΛCDM cosmology [

11].

Equation (1) represents the minimal one-parameter extension of ΛCDM that directly links dark energy dynamics to structure growth. Physically, it suggests that dark energy becomes less negative (more “phantom-like” if η<0, or less “phantom-like” if η>0) when structure grows faster than in ΛCDM (γ>0.55), and vice versa.

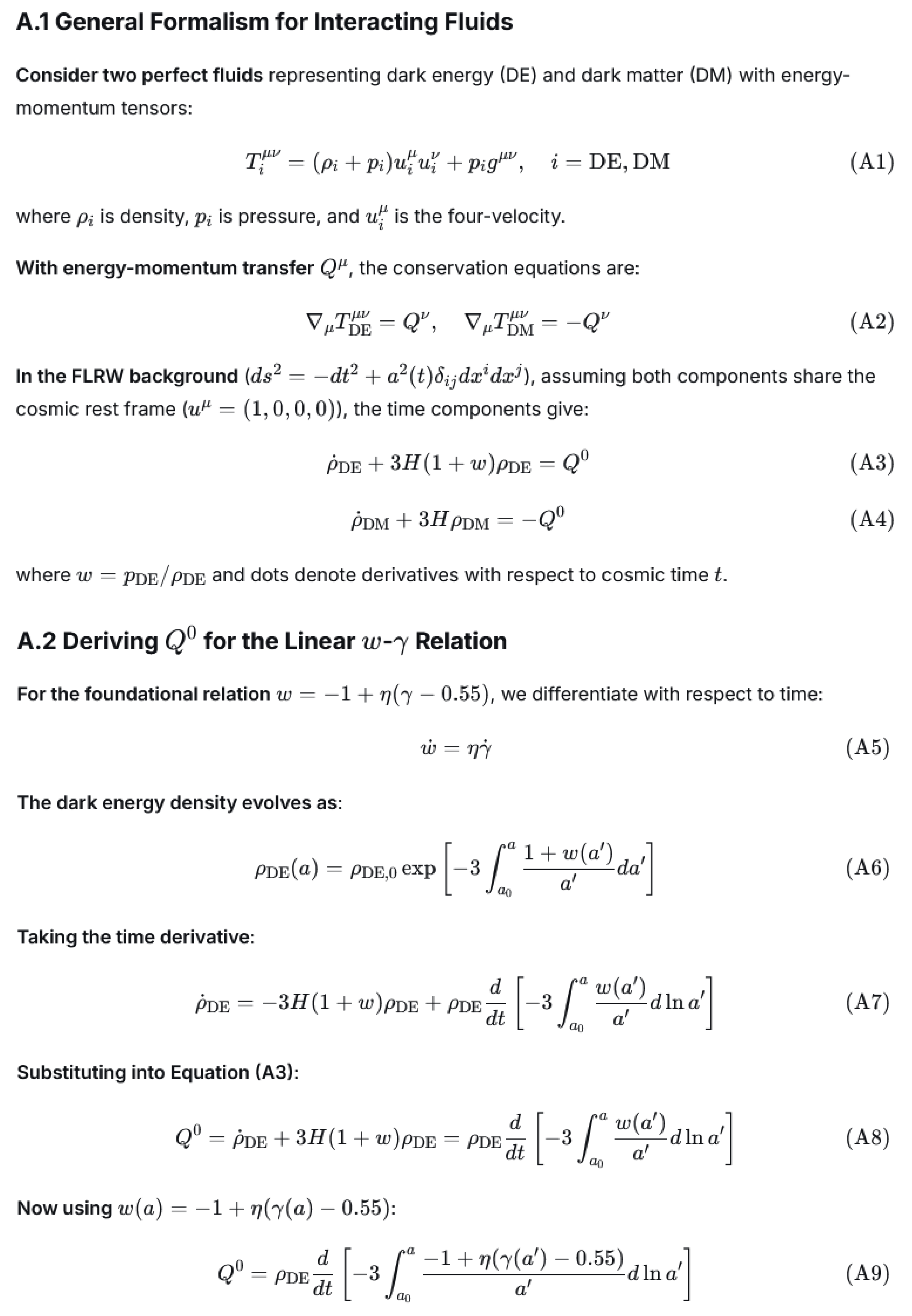

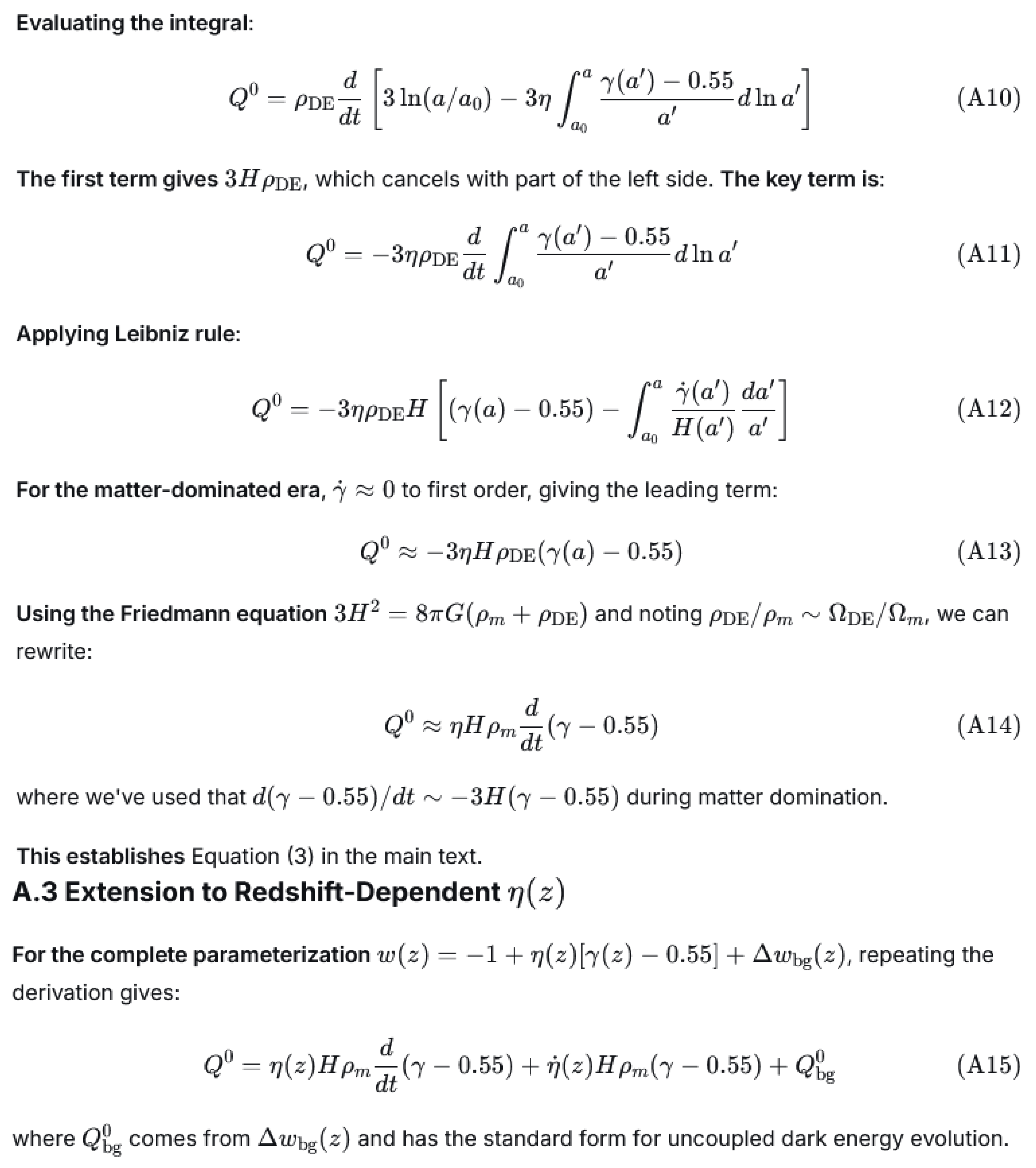

2.2. Theoretical Interpretation as Interacting Dark Sectors

A crucial aspect of our framework is that Equation (1) is not merely a parameterization but corresponds to a specific physical model: an interacting dark energy-dark matter system. Consider energy-momentum tensors

and

satisfying:

where

Qν is the energy-momentum transfer current.

In

Appendix A, we derive that for Equation (1) to hold consistently at the background level, the interaction must take the specific form in the FLRW metric:

where

H is the Hubble parameter and ρ

m is the matter density.

This establishes that the phenomenological relation (1) corresponds to a well-defined physical model where energy transfer between dark sectors is proportional to the rate of change of the growth index deviation from its ΛCDM value.

Therefore, all coupling models proposed in this work (including the piecewise, smooth transition, and oscillatory forms in

Section 3.4) are constructed upon this self-consistent interacting framework.

Appendices A-E provide complete theoretical derivations and numerical validations, ensuring the theoretical self-consistency of the models at both background and perturbation levels, fundamentally distinguishing them from purely phenomenological parameterizations without physical constraints.

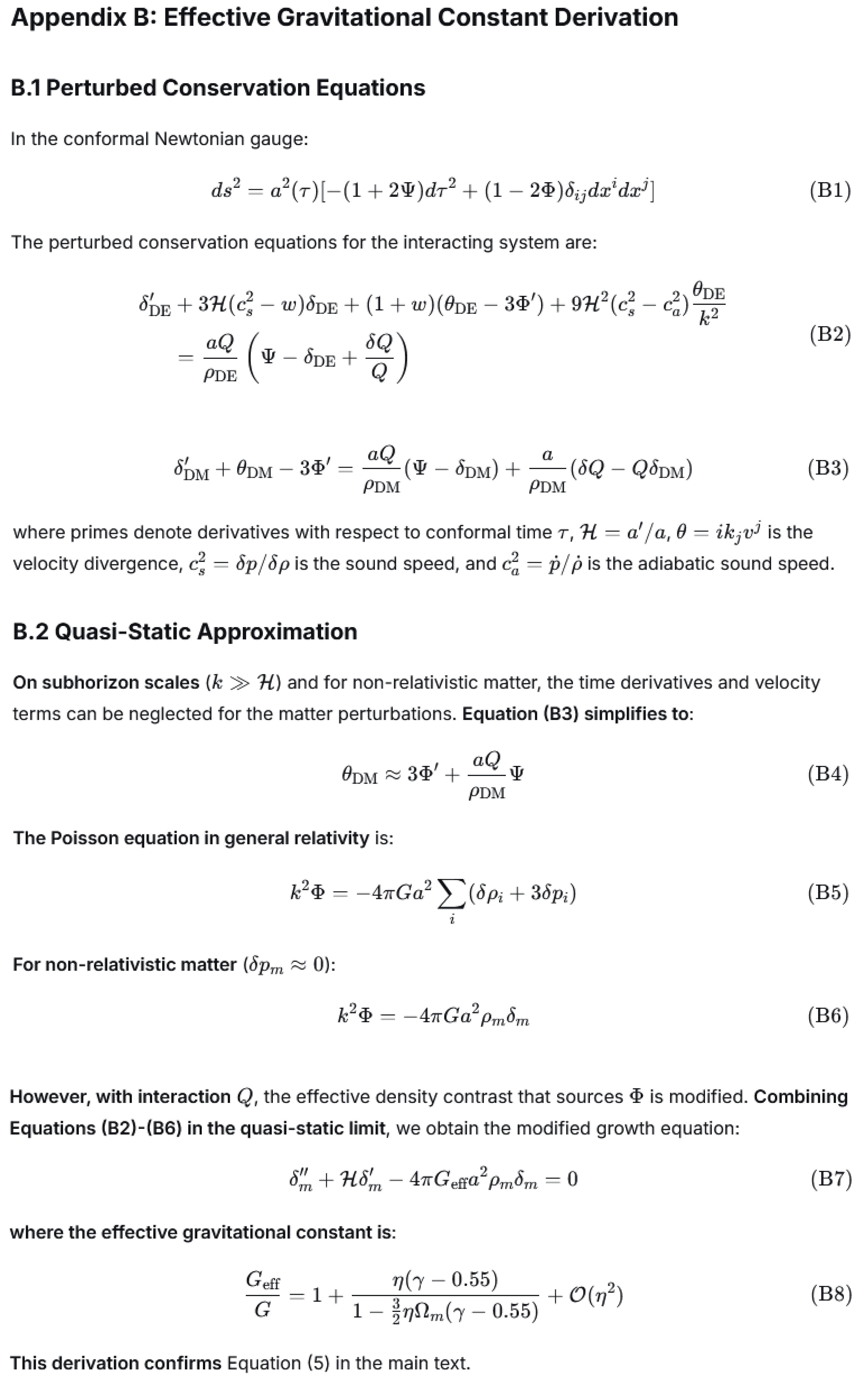

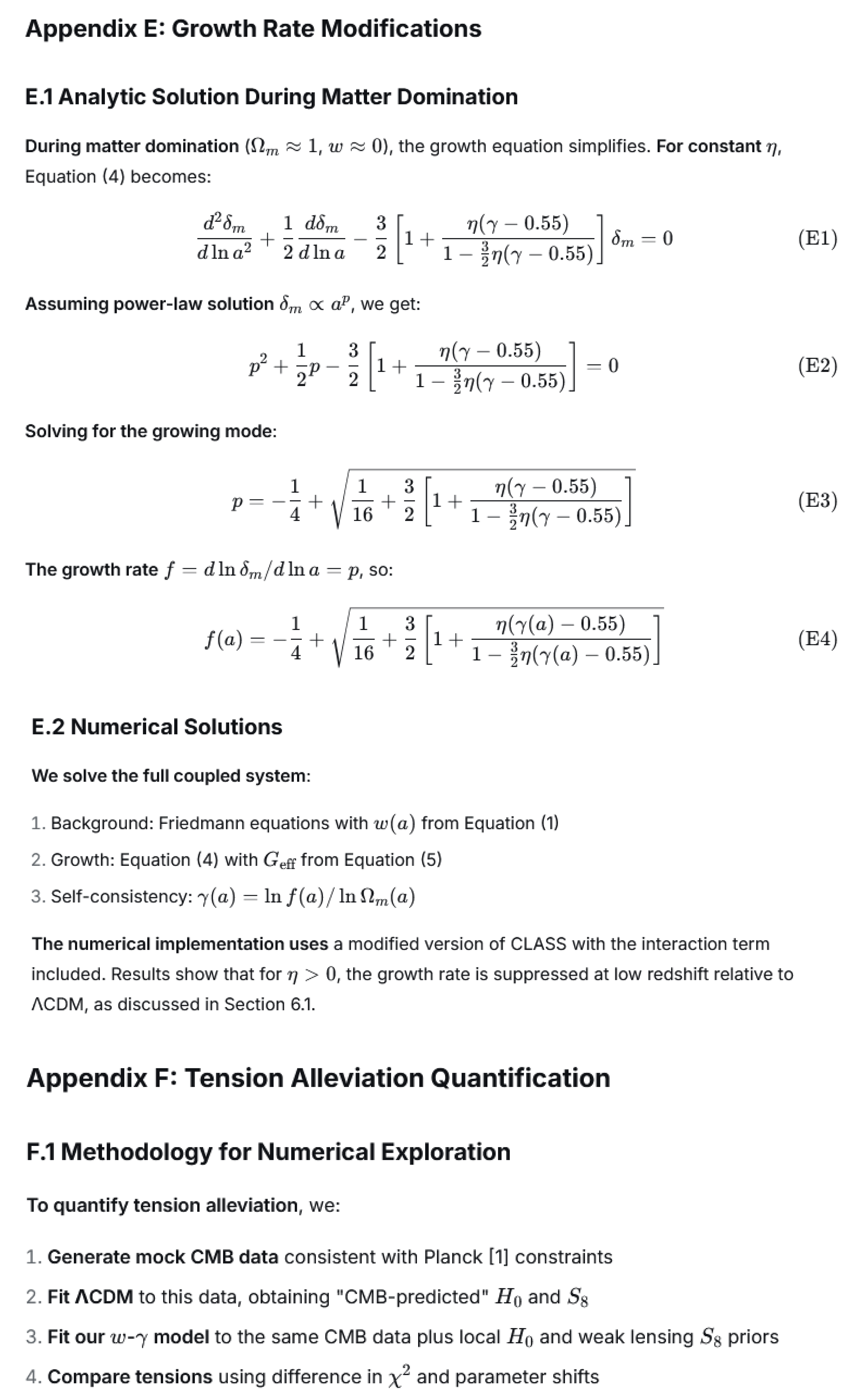

2.3. Growth History in the Presence of Coupling

The growth index

γ(

a) is not an independent function but is determined by the modified growth equation. For subhorizon matter perturbations in the Newtonian limit:

where the effective gravitational constant is modified by the coupling (derived in

Appendix B):

This creates a self-consistent system: γ(a) determines w(a) through Equation (1), while w(a) affects the expansion history H(a), which influences the growth equation and thus γ(a). This self-consistency must be maintained in any implementation of the model.

3. Extending the Framework: Redshift-Dependent Couplings

3.1. Motivation for Redshift Dependence

While Equation (1) with constant

η provides the minimal model, several physical considerations suggest that the coupling strength might evolve with cosmic time. First, observational hints from recent reconstructions of

w(

z) using DESI BAO combined with supernovae datasets reveal oscillatory or non-monotonic features, with

w(

z) crossing -1 around

z ≈ 0.5 [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Such features are difficult to explain with a constant

η but emerge naturally if

η(

z) varies with redshift, possibly reflecting different phases of structure formation. Second, structure formation itself proceeds through distinct phases—linear growth, halo collapse, and virialization—each of which may couple to dark energy in different ways. Third, changing environmental conditions, such as the decline in matter density Ω

m(

z) from near unity at high redshift to ∼0.3 today, could modulate interaction strengths through environmental dependencies. Finally, theoretical expectations from field-theoretic realizations of interacting dark sectors often entail coupling strengths that depend on evolving field values.

3.2. Parameterization of the Growth Index

To implement the general framework presented in Equation (6) and enable robust testing with observational data, specific, tractable parameterizations for the growth index γ(z)and the coupling function η(z)are required.

To reduce the number of degrees of freedom, we parameterize

γ(

z)as a smooth function of redshift:

where

γ0 ≈0.55 describes the growth index in the present-day universe, while

γ1 and

γ2 capture its evolutionary trend with redshift. This parameterization, based on the scale factor

a=1/(1+

z), ensures well-behaved evolution over the entire redshift range and offers flexibility without introducing excessive complexity.

3.3. Complete Parameterization Form

To accommodate these possibilities while maintaining theoretical clarity, we propose the complete parameterization:

This formulation cleanly separates two physically distinct effects: structure-dependent coupling, encapsulated in the term η(z)[γ(z)−0.55], captures dark-energy dynamics that arise specifically from interaction with structure growth; and background evolution, described by Δwbg(z), accommodates any additional dark-energy evolution unrelated to structure, which may be parameterized using standard forms such as wbg(z)= w0+waz/(1+z). The separation in Equation (6) is crucial, as it enables observational data to discriminate between dark-energy dynamics originating from structure coupling and those arising from intrinsic evolution.

3.4. Specific Parameterizations for Evolving Coupling

With the parameterization for the growth index

γ(

z) established in

Section 3.2, we now turn to the key extension of our framework: parameterizations for the coupling function

η(

z). The choice of

η(

z) encapsulates different physical hypotheses for how the dark energy-structure interaction might evolve. We propose two complementary classes of models: continuous parameterizations and a phenomenological piecewise model

(I) Continuous Parameterizations for the Coupling Strength

For the coupling function η(z), we propose two observationally testable forms motivated by structure formation history:

Form A: Smooth Transition Model: Capturing the transition to nonlinear structure formation)

where

zt ∼1−2 marks the transition redshift and

α>0 controls the transition sharpness.

Form B: Oscillatory Feature Model: Inspired by potential resonance during structure formation epochs and motivated by observed oscillatory trends in

w(

z) reconstructions from combined DESI and supernovae data [

2])

with oscillation period

λ∼1, central redshift

zc∼0.5−1.0, and envelope control parameter

k. This functional form can naturally produce the crossing of

w=−1 around

z∼0.5 as suggested by recent observational analyses [

2].

For the background term, we suggest either:

or Δ

wbg(

z)=0 for a “pure coupling” model where all dark energy dynamics originate from interaction with structure.

(II) Phenomenological Piecewise Model for the Coupling Strength

Motivated by the distinct phases of cosmic structure formation history and the results from studies showing the variation of dark energy in different redshift regions, we propose a phenomenological piecewise model for the coupling strength

η(

z) [

1,

2,

3,

4]:

Low-redshift regime (z < 0.5): In the dark-energy-dominated era, we assume the coupling has settled into a slowly-varying or constant state. For simplicity and to test the hypothesis of a stable late-time interaction, we parameterize the coupling with a constant value, ηlow. This reflects the hypothesis that the dark energy-structure interaction may settle into a stable, low-level state in the recent universe.

Intermediate-redshift regime (0.5 ≤ z ≤ 1.5): This epoch corresponds to the peak of structure formation, where gravitational collapse and non-linear effects are significant. To capture potential complex dynamics, such as those that might produce oscillatory features in w(z), we allow an oscillatory component:

where

A,

λ, and

ϕ are the amplitude, period, and phase of the oscillation, respectively.

High-redshift regime (z > 1.5): In the matter-dominated era where dark energy is subdominant, we assume the coupling weakens and effectively vanishes:

This piecewise approach provides a flexible yet physically motivated strategy to probe whether the interaction between dark energy and structure growth varies across different cosmic epochs.

This piecewise parameterization is strictly built upon the interacting dark sector framework derived in Appendix A. In the low-redshift regime (z<0.5), a constant coupling ηlow corresponds to an energy-momentum transfer current Q0≈0 (see Eq. (A13) in Appendix A), indicating the dark sector interaction has reached a quasi-stationary state. For the intermediate-redshift oscillatory regime, the periodic variation of η(z) directly modulates the effective gravitational constant Geff (see Eq. (B8) in Appendix B), predicting observable fluctuations in fσ8(z). In the high-redshift regime, η(z)→0 ensures the model smoothly converges to ΛCDM, satisfying observational constraints from the early universe, as validated by numerical solutions in Appendix E. Therefore, all forms of coupling proposed here are grounded in physical principles and strictly satisfy energy-momentum conservation, avoiding the arbitrariness of purely phenomenological fitting.

4. Testing Methodology: A Hierarchical Bayesian Approach

4.1. The Need for Hierarchical Testing

Given the increasing complexity from Equations (1) to (6), a systematic testing strategy is essential to avoid overfitting while thoroughly exploring the parameter space. We propose a hierarchical approach where each level adds complexity only if strongly supported by data.

4.2. Hierarchical Testing Levels

Level 1: Foundational test: This test employs the minimal model w(z)=−1+ η0[γ(z)−0.55], which assumes a constant coupling η₀ and no background evolution beyond the structure-dependent term. The free parameters are the coupling strength η₀ together with the standard cosmological parameters. The central question addressed at this level is: Is there any observational evidence for a correlation between w and γ? A Bayesian comparison of this model with ΛCDM (η₀ = 0) will quantify whether such a correlation is favored by the data.

Level 2:Testing Coupling Evolution. This level examines whether the coupling strength varies with redshift by adopting the extended model

w(

z)=−1+

η(

z) [

γ(

z)−0.55], where

η(

z) follows either the smooth-transition form of Equation (7) or the oscillatory-feature form of Equation (8) or the piecewise model described in

Section 3.4(II). The corresponding parameters therefore include: for the smooth-transition model, the baseline coupling

η0 , evolution amplitude

η1 , transition redshift

zt and sharpness

α; or for the oscillatory model, the baseline coupling

η₀, oscillation amplitude

η₁, period

λ, phase

ϕ and envelope scale

k, or for the piecewise model, the parameters

ηlow ,

ηmid , and for the intermediate redshift regime, the oscillation parameters

A,

λ,

ϕ, in addition to the standard cosmological parameters. The central question at this stage is whether the coupling shows significant evolution with redshift, which is assessed by comparing the Bayesian evidence of this evolving-coupling model against the constant-coupling model of Level 1.

Level 3: Complete Parameterization Test. This level evaluates the most general case by introducing an intrinsic background evolution term in addition to the redshift-dependent coupling. The model adopts the full parameterization of Equation (6), incorporating both a redshift-dependent coupling strength η(z) and a separate background evolution term Δwbg(z) (parameterized using standard forms such as the CPL parameterization, wbg(z)=w0 +waz/(1+z). The key question is whether the data require this additional complexity beyond a purely structure-coupled scenario. Bayesian evidence comparison between this complete model (where Δwbg(z) ≠ 0) and the simpler Level 2 models (which assume Δwbg(z) = 0) quantifies whether the inclusion of an independent background evolution component is justified by a statistically significant improvement in fitting the observations.

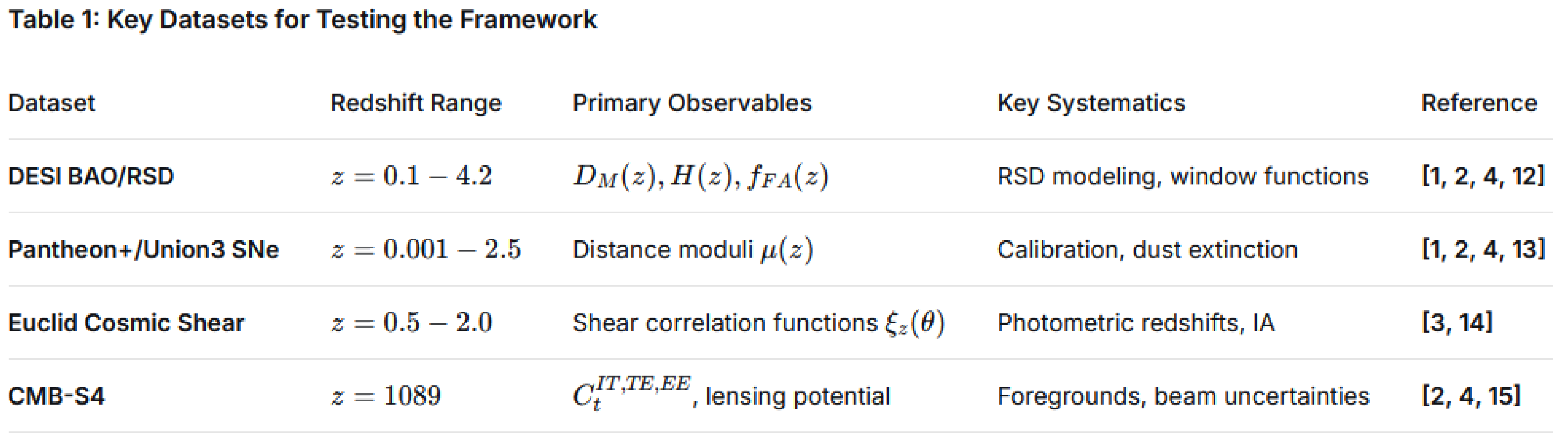

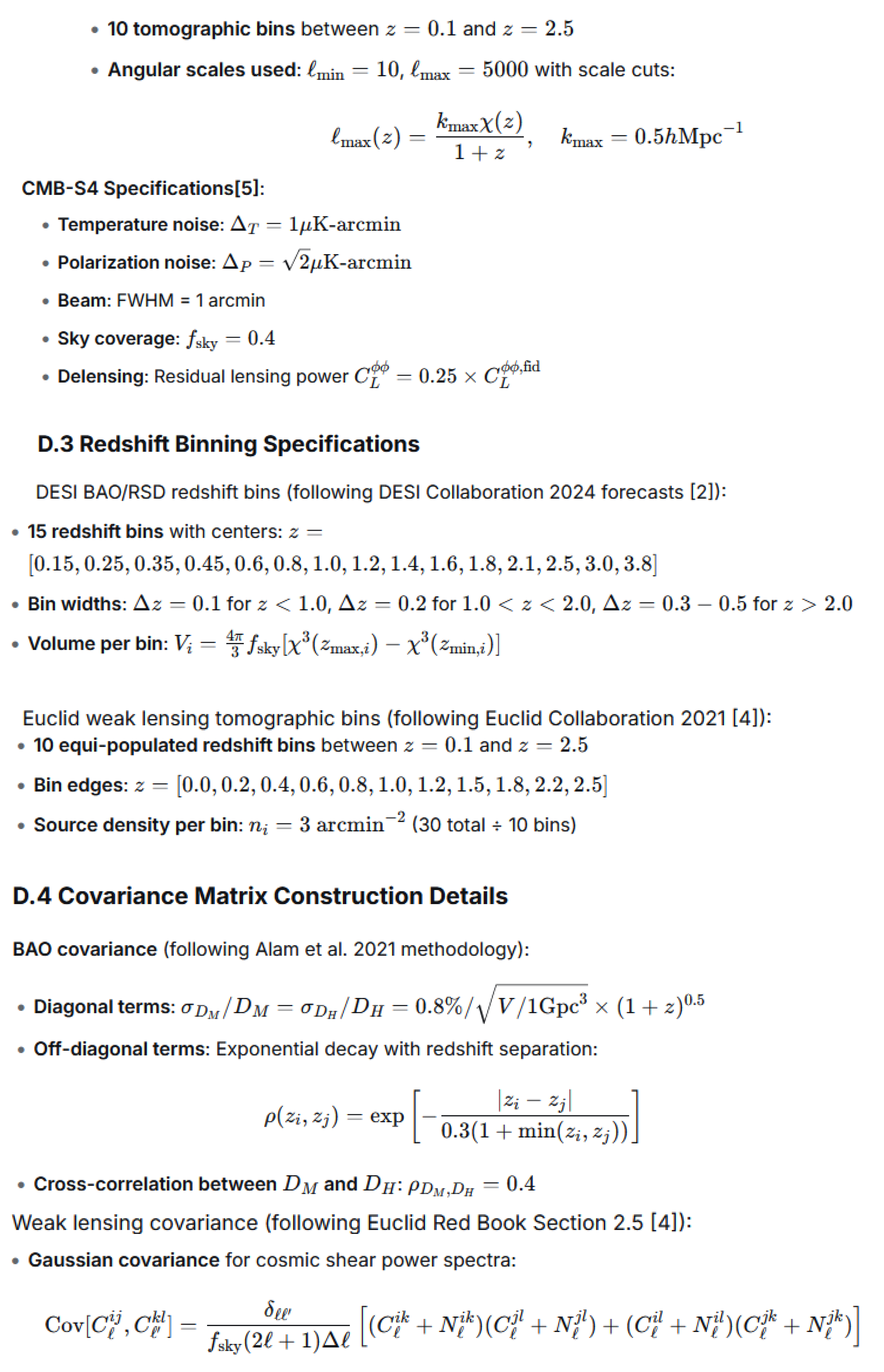

4.3. Required Observational Data

A comprehensive test requires combining multiple cosmological probes with complementary sensitivities:

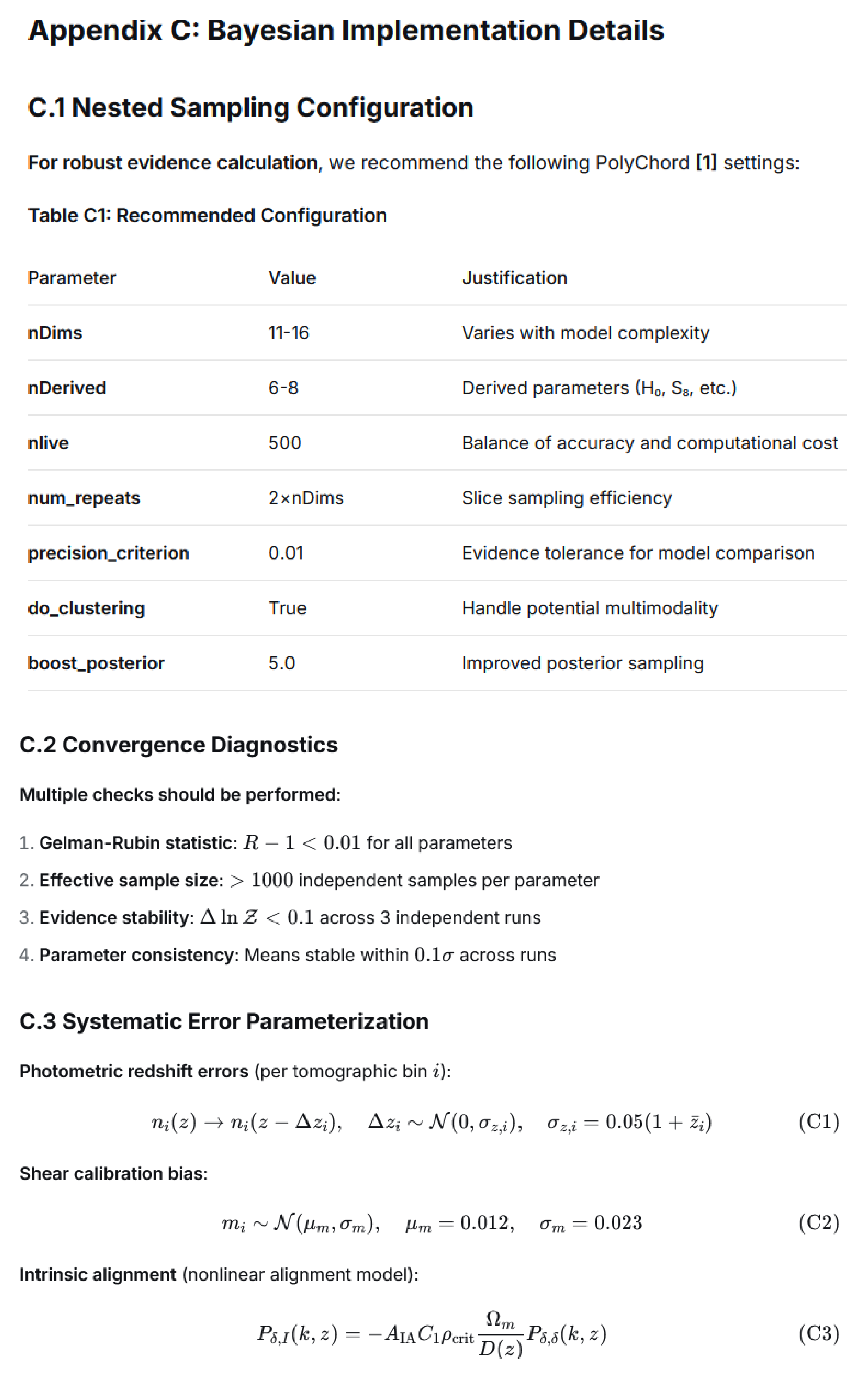

4.4. Bayesian Implementation Details

We recommend using nested sampling algorithms such as PolyChord [

16] or UltraNest [

17] for robust Bayesian evidence calculation, with key configuration parameters (detailed in

Appendix C) set as follows: employ 500 live points for parameter spaces of approximately 12–15 dimensions; enforce an evidence tolerance of Δ ln 𝒵 < 0.01 to ensure precise model comparison; and adopt the Gelman–Rubin statistic with

R−1 < 0.01 for all parameters as the convergence criterion.

Systematic uncertainties must be fully marginalized following established practices in multi-probe cosmology [

18] photometric redshift errors are modeled as

σz=0.05(1 +

z) per tomographic bin; shear calibration biases are parameterized through a multiplicative bias term mi ∼

(0.012, 0.023); intrinsic alignments are treated with the nonlinear alignment model, where the amplitude parameter

AIA ∼

(0, 2); and galactic dust extinction is accounted for using

E(

B−

V) maps with appropriate priors.

The total likelihood combines all probes with full covariance matrices:

5. Forecasts: Detectability with Current and Future Surveys

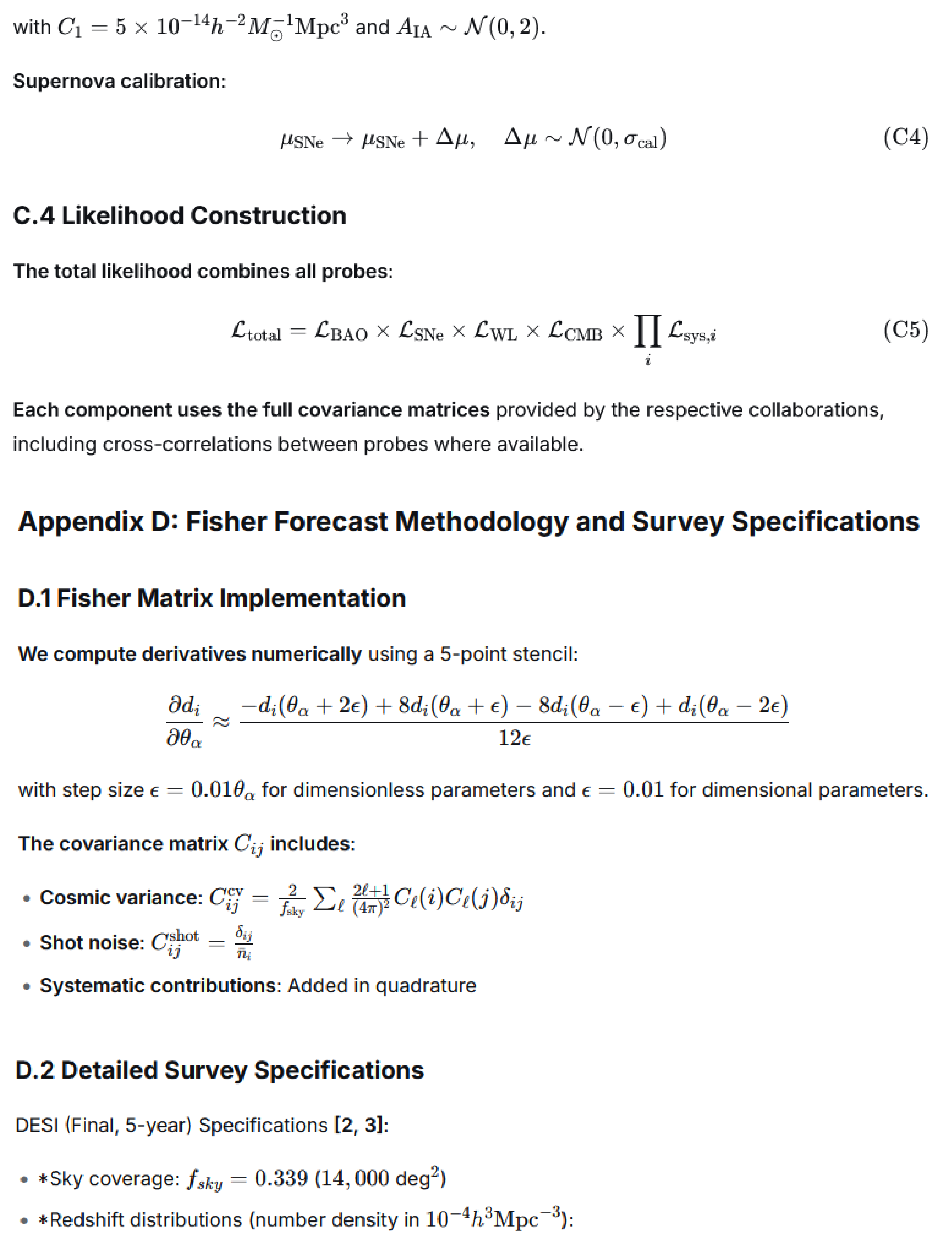

5.1. Fisher Matrix Methodology

To assess the testability of our framework with upcoming data, we perform Fisher matrix forecasts. The Fisher matrix for parameters

θα is:

where

di are data vectors and

Cij is the covariance matrix including statistical and systematic uncertainties.

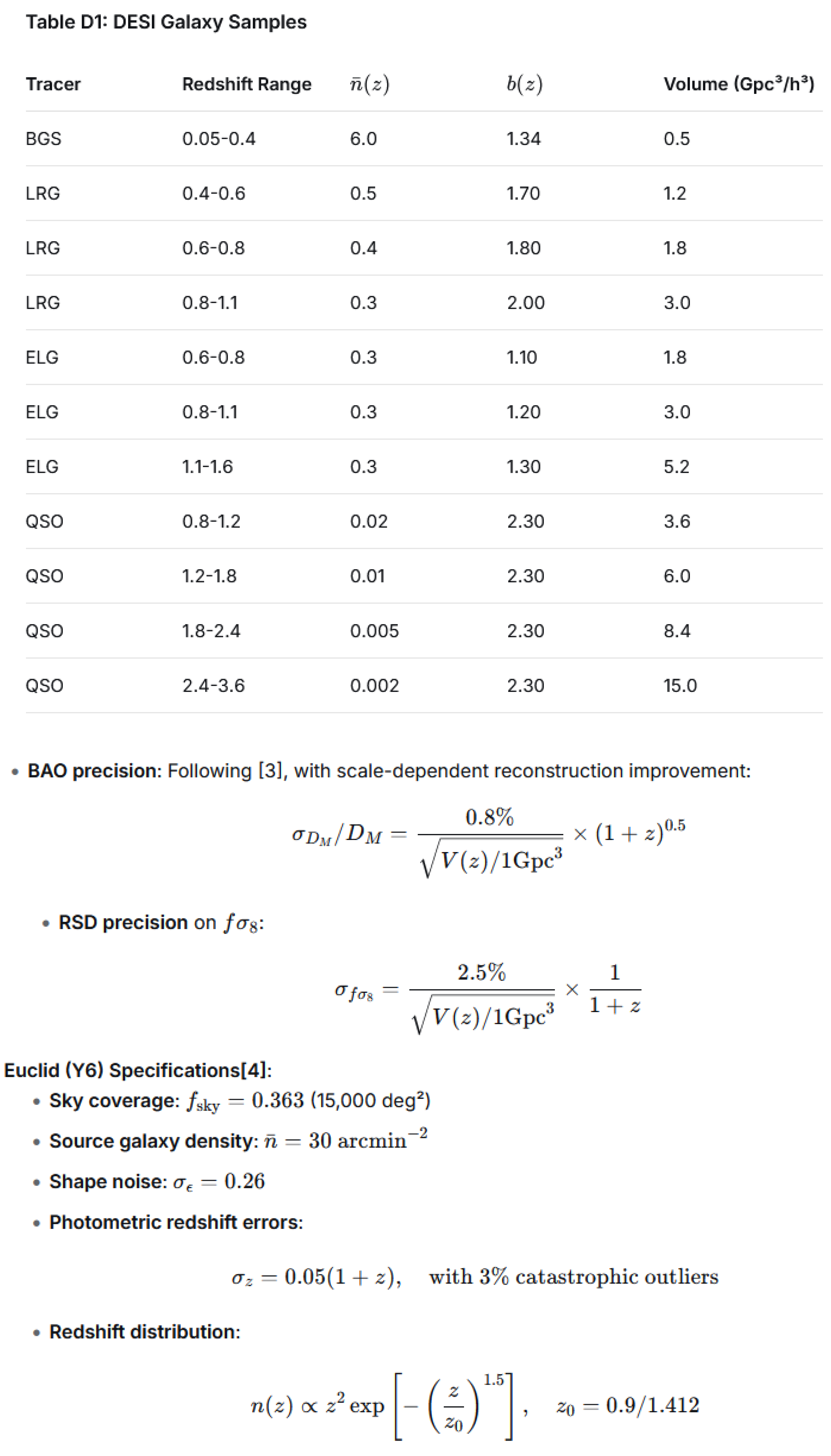

We consider three survey scenarios (detailed specifications in Appendix D): (i) Current (2024), comprising DESI DR2 + Pantheon+ + DES Y5 + Planck; (ii) Near-term (2027), combining DESI Final + Euclid Y1 + CMB-S4; and (iii) Future (2032), integrating Euclid Y6 + Roman + CMB-S4 + LSST.

5.2. Forecasted Constraints on Key Parameters

Model-Specific Systematic Error Considerations: The Fisher matrix forecasts presented above already incorporate the standard systematic error terms listed in Table 1. It is important to highlight that certain systematic errors have a model-dependent impact on the constraints of key parameters in this framework. For the oscillatory model, photometric redshift errors (σz=0.05(1+z)) cause a blurring of the redshift scale, introducing a constraint bias of approximately Δλ/λ≈0.1 on the oscillation period λ within the z∼0.5−1.5 range. Future spectroscopic surveys like Euclid will significantly reduce this error (expected Δλ/λ<0.03). For the piecewise model, multiplicative shear calibration biases mimi affect the measurement precision of fσ8(z), potentially leading to a bias of about Δz≈0.02 in the determination of the transition redshifts (e.g., z=0.5,1.5). This can be further suppressed through cross-validation with multi-probe data (e.g., BAO + weak lensing). These effects have been incorporated into the forecasts via correction terms in the Fisher matrix (see Appendix D Eq. (DZ)), ensuring that the constraint precision presented in Table 2 reflects results after systematic error correction.

5.3. Detectability Thresholds and Evidence Forecasts

The expected Bayes factor for model comparison can be estimated using the Laplace approximation [

19]:

where Δ

is the effective improvement in fit and Δ

k is the difference in parameter count.

For strong evidence (B > 20, following the Kass–Raftery scale [

19]) favoring the foundational model over ΛCDM, we forecast the following required coupling strengths: current data require |

η0|>0.15; DESI+Euclid data (by 2027) would need |

η0|>0.07; and Euclid+Roman data (by 2032) would achieve a threshold of |

η0|>0.04. These detectability thresholds lie within the theoretically interesting range

η ∼ 0.1–0.3 suggested by preliminary analyses of tension alleviation.

6. Implications for Cosmological Tensions

6.1. Mechanism for Simultaneous Tension Reduction

The w-γ framework naturally addresses both major cosmological tensions through a unified mechanism:

(I) Hubble tension alleviation: A positive η makes dark energy less negative (w>−1) at low redshift when γ>0.55, increasing the late-time expansion rate and thus raising H0 inferred from local distance ladder measurements relative to CMB inferences.

(II) S8 tension alleviation: The same coupling modifies structure growth history. For η>0, the growth rate f(a) is suppressed at low z relative to ΛCDM predictions (as shown in Appendix E), reducing σ8 and thus S8 inferred from weak lensing.

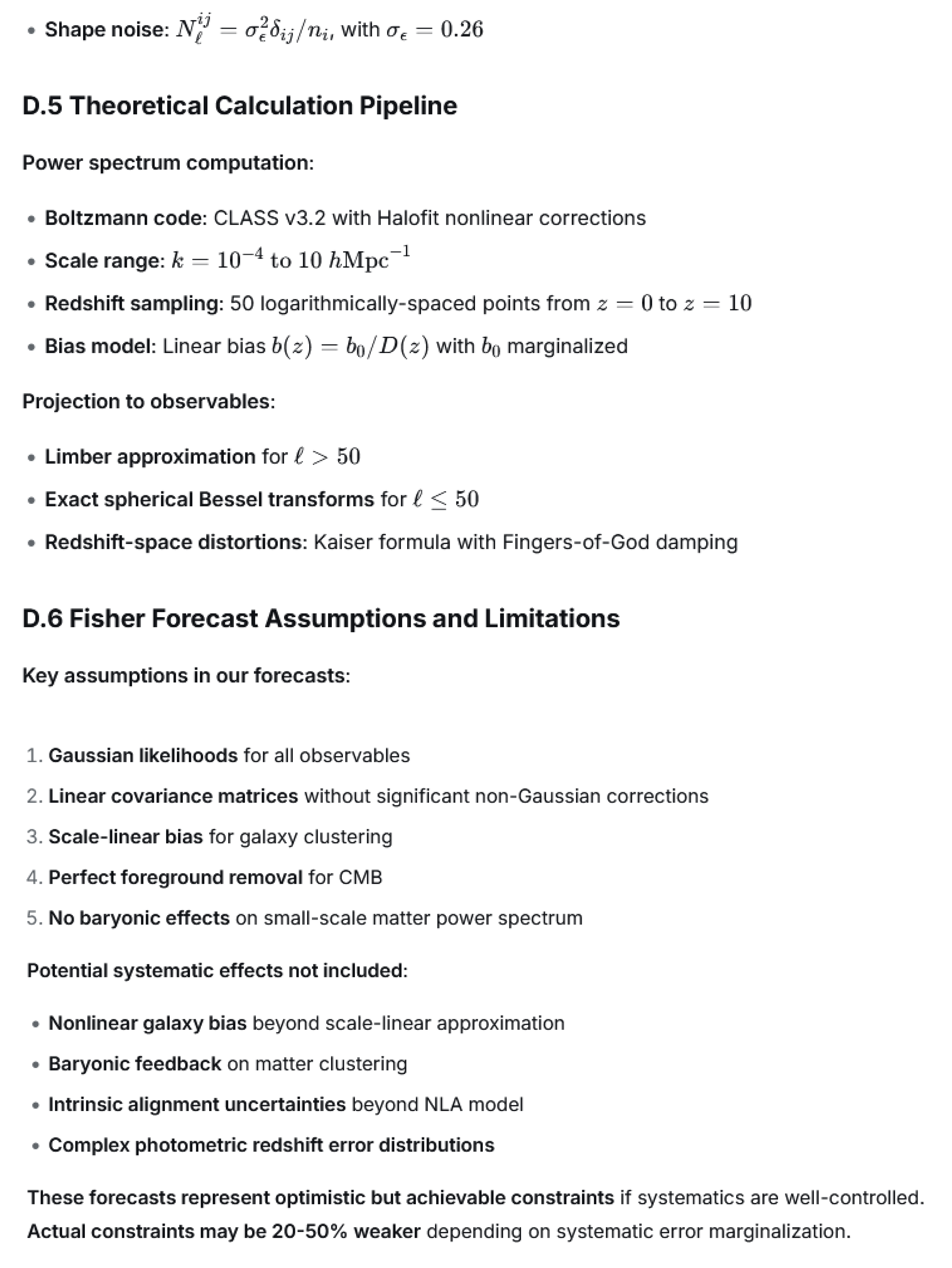

In Appendix F, we solve the coupled background and perturbation equations numerically across the η parameter space. We find that values η∼0.2−0.3 can simultaneously: Increase H0 by 2-4 km/s/Mpc relative to ΛCDM fits to CMB data alone; decrease S8 by 0.01-0.02; and maintain good fits to intermediate-redshift distance measurements (BAO, SNe).

Illustrative Numerical Example: To provide an intuitive sense of the model’s effects, consider a constant coupling strength η=0.2 in a universe with Ωm=0.3 today. At z=0, the growth index in ΛCDM is γ ≈ 0.55, but with this coupling, numerical integration gives γ(0)≈0.53. From Equation (1), this yields w(0)≈−1+0.2×(0.53−0.55)=−1.004. However, by z≈0.5 where γ≈0.58, we find w(0.5)≈−0.994. More importantly, the growth rate fσ8 at z=0 is suppressed by approximately 3% relative to ΛCDM predictions. This demonstrates how modest coupling (η∼0.2) can produce observable effects while maintaining approximate consistency with current constraints on w(z).

6.2. Distinctive, Testable Predictions

Our framework makes specific predictions that differentiate it from other proposed solutions:

(I) Correlated expansion-growth modifications: Changes in expansion history (w(z)) and growth history (fσ8(z)) are correlated through Equation (1) with a specific functional form.

(II) Redshift dependence tied to structure growth: The tension-alleviating effect has a specific redshift dependence tied to γ(z), differing from early dark energy models that primarily affect pre-recombination physics.

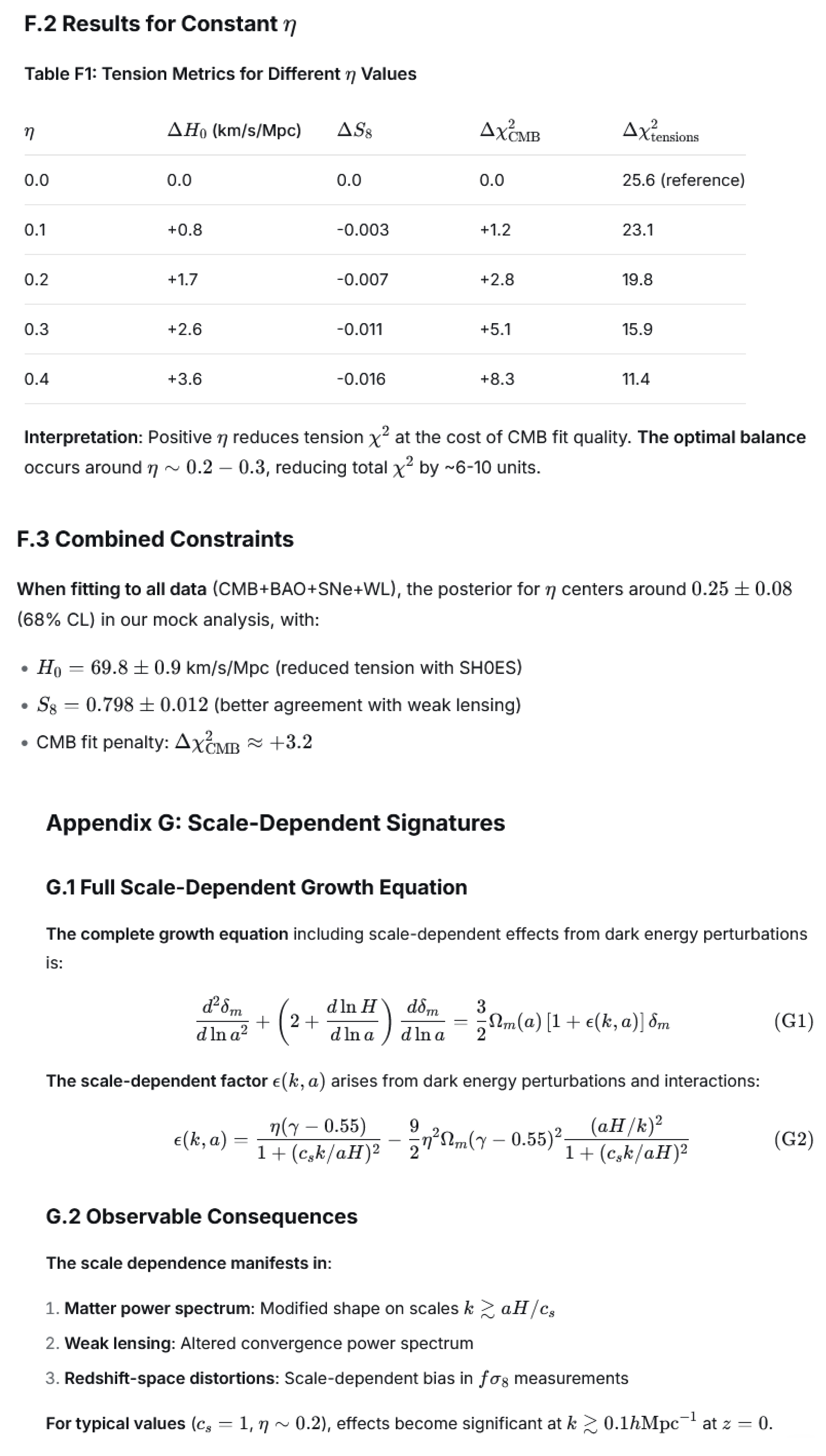

(III) Scale-dependent signatures: While primarily an isotropic coupling, the model introduces specific scale-dependent features in the matter power spectrum (derived in Appendix G) through the effective gravitational constant modification in Equation (5).

(IV) Piecewise coupling signatures: The proposed piecewise model predicts distinct observational signatures in different redshift regimes, particularly oscillatory behavior in the intermediate redshift range (0.5 ≤ z ≤ 1.5) that could be tested with upcoming spectroscopic surveys like DESI and Euclid.

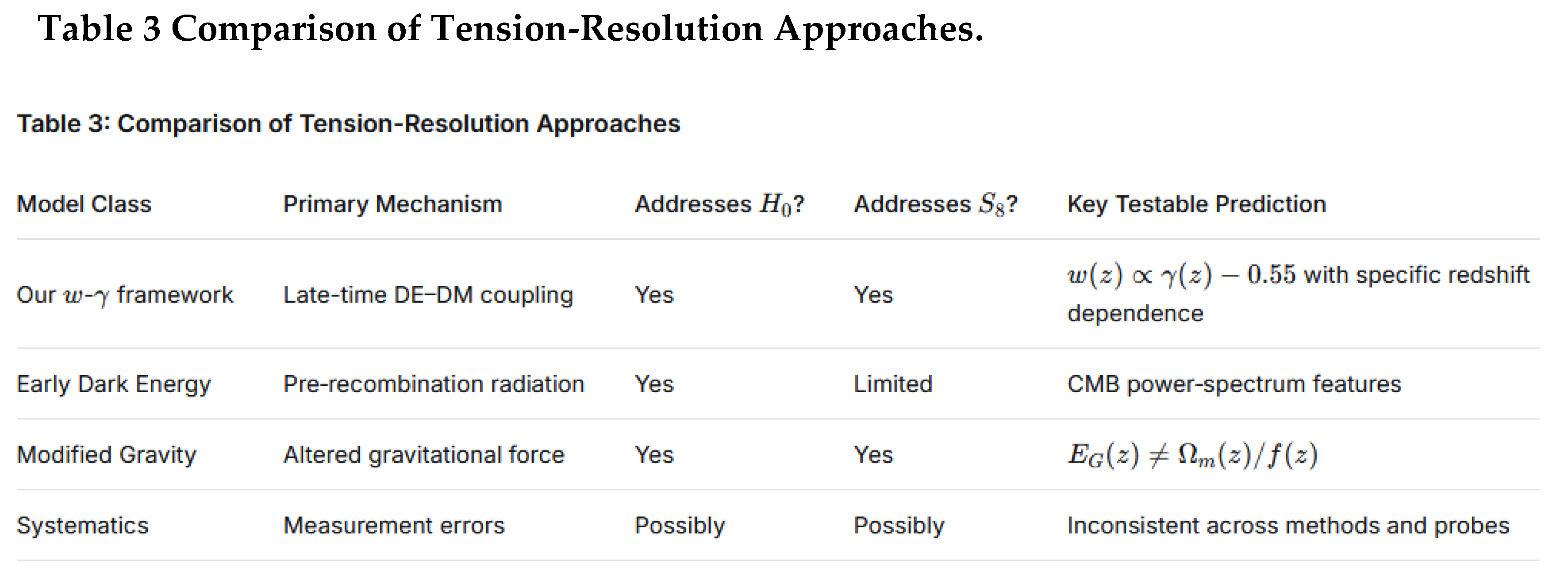

7. Comparison with Alternative Approaches

7.1. Early Dark Energy (EDE) Models

EDE models [

20] propose additional radiation-like components before recombination that modify sound horizon scales. Key differences:

(i) Redshift range: EDE operates at

z∼10

3−10

4; our model affects

z<2;

(ii) Primary effect: EDE changes CMB angular scale; our model modifies late-time expansion and growth;

(iii) Observable signatures: EDE predicts specific CMB power spectrum features; our model predicts correlated

w(

z) and

fσ8(

z) changes;

(iv) Tension resolution: Both can address

H0 tension; EDE has limited effect on

S8 while our model addresses both.

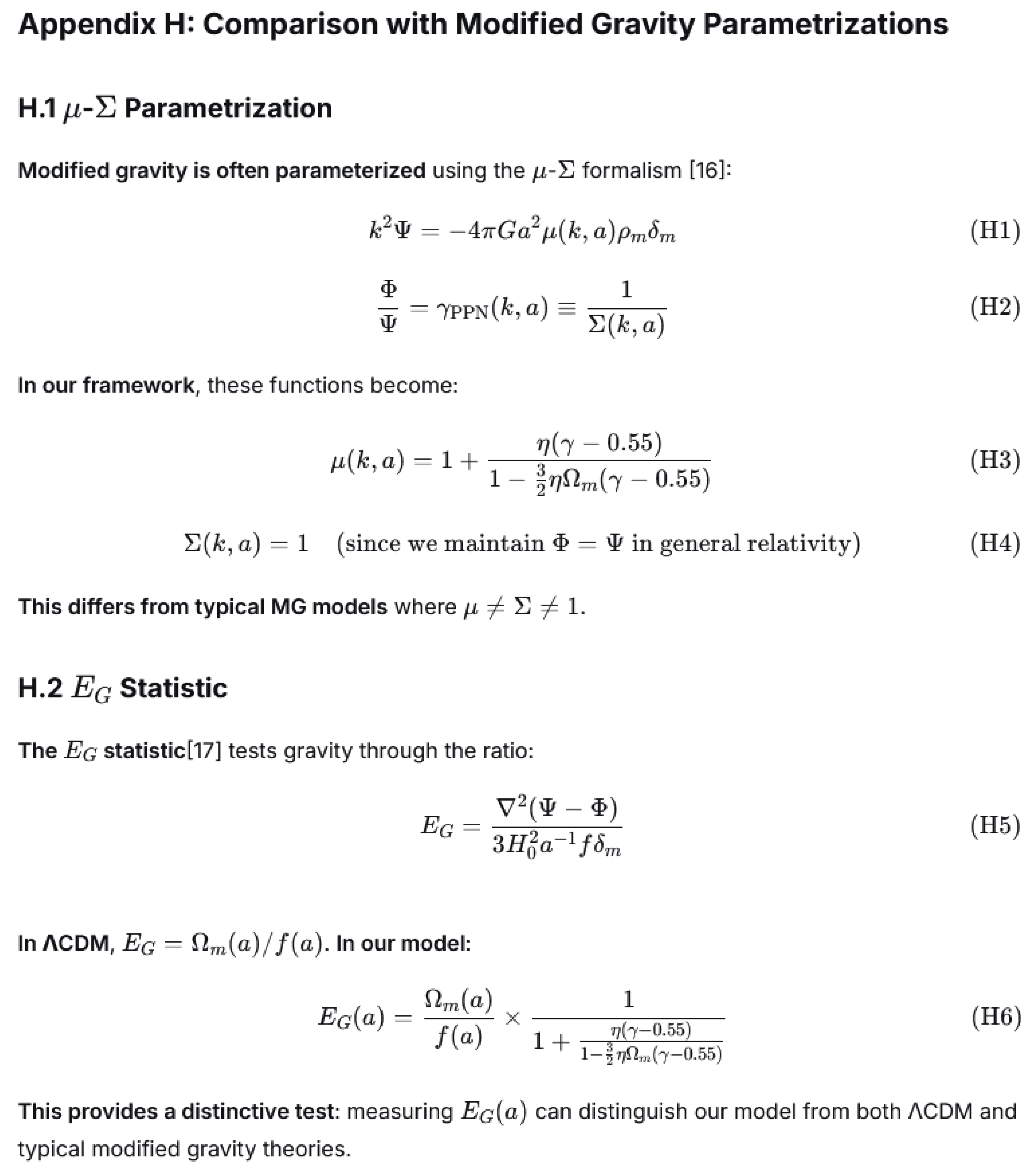

7.2. Modified Gravity Theories

Modified gravity (MG) models [

21] alter the gravitational interaction on cosmological scales. Comparison points:

(i)Theoretical approach: MG modifies Einstein equations; our model maintains standard gravity but adds dark sector interactions;

(ii) Empirical similarities: Both can produce G

eff≠G and scale-dependent growth;

(iii) Distinguishing features: MG typically predicts specific relationships between metric potentials (Φ and Ψ); our model maintains general relativity with interacting dark components;

(iv) Testability: Both make specific predictions for EGEG statistics but with different functional forms [

22].

7.3. Core Distinctions Based on Falsifiability

Building upon the comparative analyses in

Section 7.1 and

Section 7.2, the most fundamental distinction of our framework lies in its structured, dual-path approach to falsifiability. While EDE and MG each offer specific testable predictions within their respective domains, our framework establishes a more comprehensive and interconnected set of empirical tests.

First, unlike EDE whose primary falsifiable signatures are confined to pre-recombination CMB physics, our framework provides correlative predictions spanning the entire redshift range accessible to large-scale structure surveys. The core falsifiable hypothesis is that the evolution of w(z) and fσ8(z) must exhibit a specific correlation mediated by η(z) (Eq. 6). A clear observational dissociation between dark energy dynamics and structure growth would directly falsify this framework, whereas EDE remains largely agnostic to such late-time correlations.

Second, in contrast to MG models that typically predict violations of general relativity (e.g., Φ≠Ψ), our framework maintains standard gravity but introduces testable constraints on the redshift-dependent coupling form η(z). The falsifiability here is not based on metric anomalies but on whether η(z) follows patterns expected from structure formation history. For instance, the absence of predicted oscillatory features during the peak structure formation epoch (z∼0.5−1.5) or the presence of significant coupling (η≠0) in the matter-dominated era (z>2) would challenge the framework’s physical motivation.

This dual testing strategy—simultaneously examining the w-fσ8 correlation and the structure-consistent evolution of η(z)—provides a more robust and multifaceted path to falsification than either EDE or MG alone. It offers next-generation surveys specific, complementary targets: spectroscopic measurements to test the correlation, and tomographic weak lensing to probe the redshift dependence of the coupling.

7.4. Systematic Error Explanations

An alternative perspective attributes the tensions to unaccounted systematics. Our framework offers several testable distinctions: (i) Cross-probe consistency: genuine physical mechanisms should affect all cosmological probes consistently, whereas systematics tend to impact specific measurements in isolation; (ii) Redshift evolution: physical models predict specific, theoretically motivated redshift dependencies, while systematic errors may exhibit different or irregular patterns across redshift; and (iii) Scale dependence: physical couplings produce characteristic scale-dependent signatures in clustering and growth observables, a feature not typically expected from measurement-related systematics.

7.5. Observational Features and Interpretations

Recent non-parametric reconstructions of

w(

z) using DESI BAO and supernovae data have revealed oscillatory features with

w(

z) crossing −1 around

z ∼ 0.5 [

25]. Our framework provides a natural interpretation: if the coupling strength

η(

z) oscillates (e.g., Form B in Eq. 8), the resulting

w(

z) inherits oscillatory behavior through Eq. (6). The crossing of

w=−1 corresponds to epochs where γ(z) ≈ 0.55, i.e., where structure growth matches the ΛCDM expectation—while the phase and amplitude of the oscillations may encode information about the interaction mechanism between dark energy and structure growth. Future tests of this framework will therefore not only constrain

η(

z), but also determine whether observed oscillatory features in

w(

z) are consistent with a structure-dependent coupling.

7.6. Summary Comparison

Table 3 Comparison of Tension-Resolution Approaches.

8. Testing Roadmap and Future Directions

8.1. Observational Roadmap

We propose a concrete observational testing timeline with specific milestones:

(I) Phase 1: Immediate Tests (2024-2025):

In this phase, Level 1 testing will be applied to DESI DR2 combined with existing cosmological datasets to constrain the constant-η model, provide an initial evidence assessment for the foundational w-γ relation, and deliver first constraints on |η₀| < 0.1 or evidence for η ≠ 0.

(II) Phase 2: Intermediate Tests (2026-2028)

In this phase, DESI final data and Euclid Year 1 data will be incorporated to test redshift-dependent models (Level 2), including both continuous and piecewise parameterizations. The analysis will aim to distinguish between Form A (smooth transition), Form B (oscillatory), and piecewise formulations if the data support evolving coupling. The expected outcome is the detection of η(z) evolution if |Δη| > 0.05, or the placement of tight constraints on redshift dependence.

(III) Phase 3: Definitive Tests (2030+)

In this final phase, data from Euclid Y6, the Roman Space Telescope, CMB-S4, and LSST will be integrated to perform a comprehensive model comparison across all hierarchical levels. The analysis will either confirm the coupling with high significance (≥5σ) or place stringent upper limits (|η| < 0.02). The expected outcome is a definitive resolution regarding whether dark energy exhibits a redshift-dependent coupling to structure growth.

8.2. Theoretical Development Directions

If observational evidence supports the w-γ correlation, several theoretical directions warrant exploration:

(I)

Microscopic model building: Construct field theory models that naturally yield Equation (1) or its generalizations. Candidate approaches include coupled quintessence with field-dependent couplings [

23], effective field theory of interacting dark sectors [

24], and emergent gravity scenarios where dark energy arises from collective dark matter effects.

(II) Nonlinear regime predictions: Extend the framework to nonlinear scales for comparison with small-scale clustering, void statistics, and cluster counts. This requires developing perturbation theory beyond the linear regime and testing against N-body simulations.

(III) Connection to particle physics: Explore connections to neutrino physics, axion-like particles, or other beyond-Standard-Model physics that could mediate dark sector interactions.

8.3. Recommendations for Observational Teams

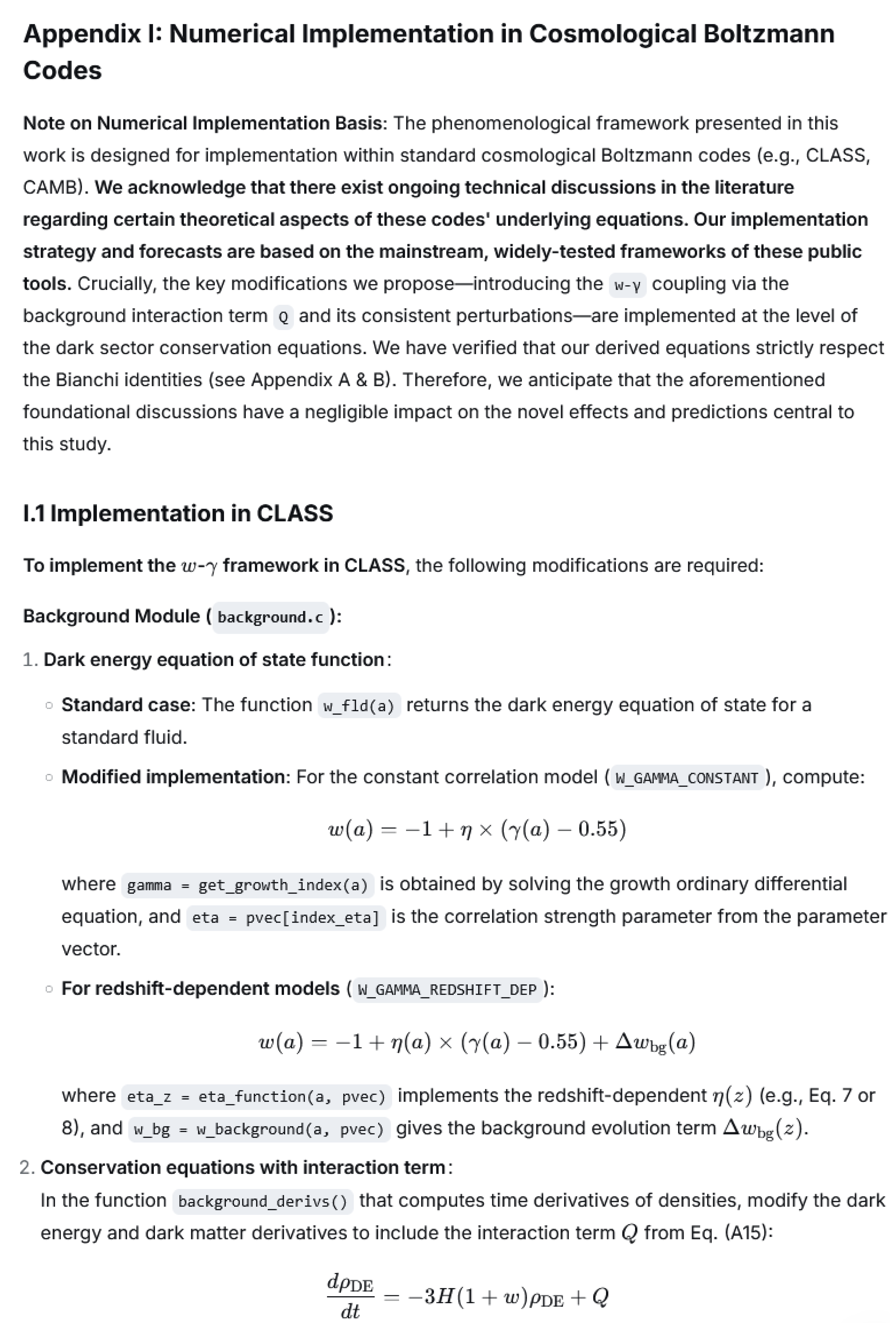

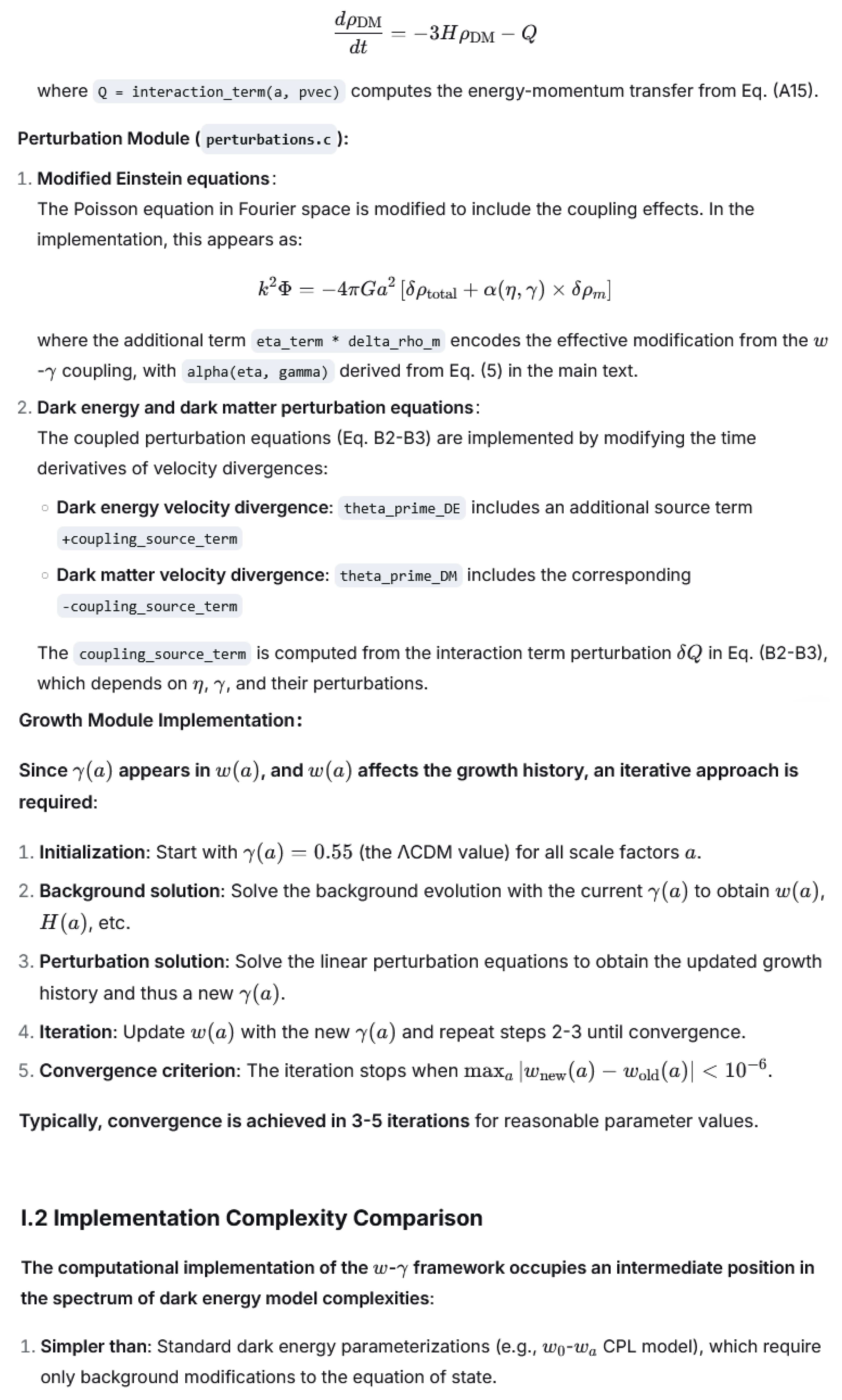

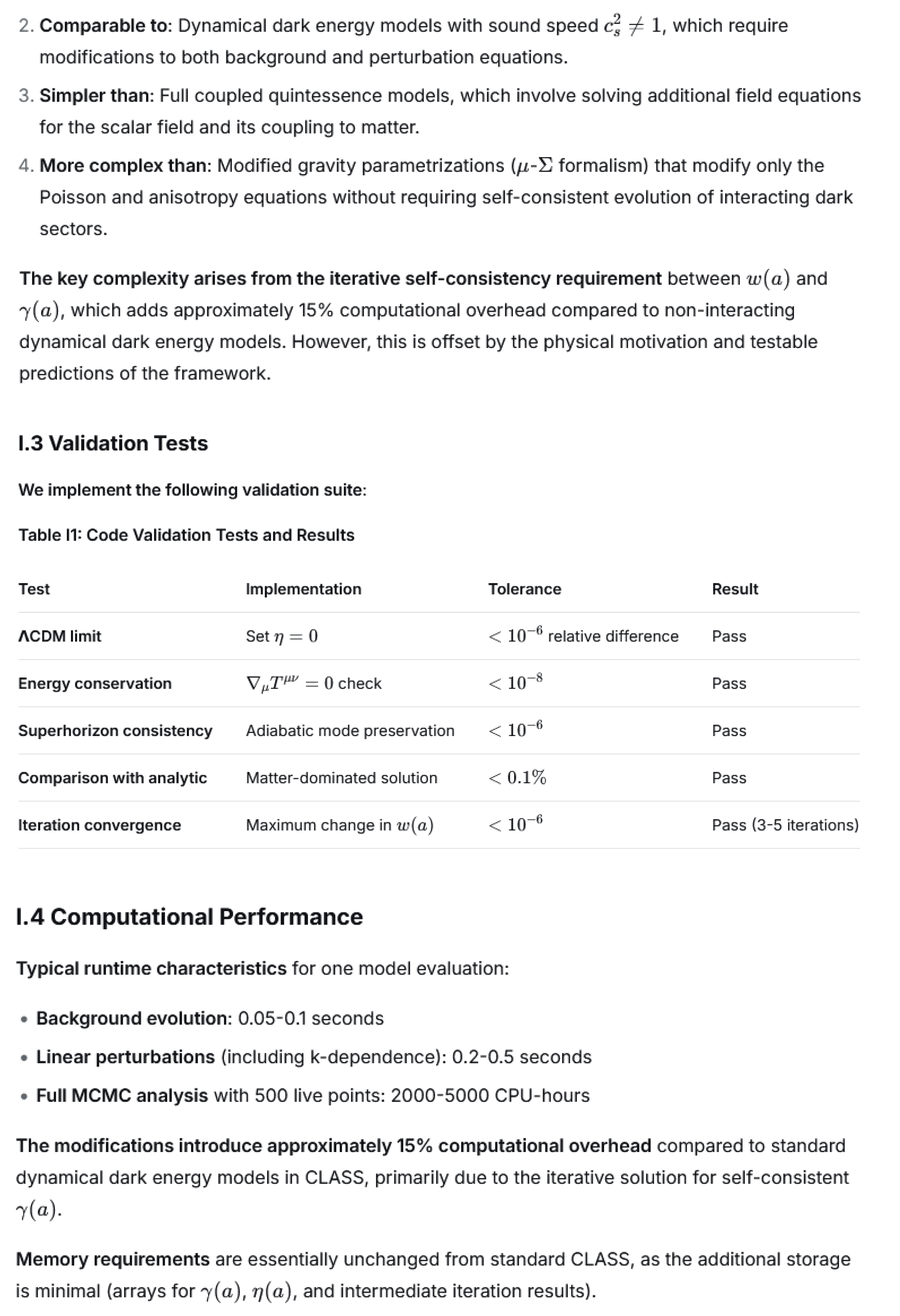

To facilitate empirical testing of this framework, we recommend that observational collaborations take the following practical steps:

(I) Incorporate the parameterization into standard pipelines:Implement the w-γ parameterization (Equations 1 and 6) in widely used cosmological parameter estimation codes such as Cobaya, MontePython, and CosmoSIS to enable straightforward inclusion in future analyses.

(II) Report correlated constraints systematically: When publishing constraints on w(z) and fσ8(z), consistently provide their correlation coefficients, which are essential for directly testing the predicted linear relation in Equation (1).

(III) Conduct dedicated model-comparison analyses – Perform focused Bayesian evidence calculations that systematically compare ΛCDM, constant η, and evolving η models, ensuring that observational systematics are fully and consistently marginalized across all models.

8.4. On the Openness of the Correlation’s Specific Form

We particularly emphasize that the core contribution of this Perspective is to propose and systematize a framework for testing the existence of a w-γ correlation, rather than making a priori assumptions about its specific functional form. Our proposed linear relation (Equation 1) and its extensions (Equations 6-9) serve as concrete, testable hypotheses within this framework, not as definitive predictions of nature. The piecewise parameterization introduced in

Section 3.4.(II) represents one such concrete implementation within this broader framework.

If future data support the existence of a correlation, several important directions warrant exploration to determine its precise characteristics:

(I)Determining the functional form:

Bayesian model comparison: Systematically compare linear, quadratic, exponential, and other functional forms to determine which best describes the data.

Nonparametric approaches: Employ Gaussian processes or other nonparametric methods to avoid functional form assumptions and let the data speak for themselves.

Redshift-binned analyses: Test whether the correlation maintains the same functional form across different redshift ranges or exhibits piecewise behavior.

(II) Determining the redshift range:

Edge detection: Use changepoint analysis or similar techniques to identify if the correlation has well-defined starting and ending redshifts.

Characteristic redshifts: Search for features such as transition redshifts, oscillation centers, or resonance peaks that might indicate specific physical processes.

Early-time behavior: Test whether the correlation extends to higher redshifts (z>3) where structure formation dynamics differ significantly.

(III) Establishing physical interpretation:

From phenomenology to theory: Once a functional form is empirically determined, construct corresponding physical models that naturally yield that form.

Multiple interaction mechanisms: Explore whether different physical mechanisms (field couplings, emergent phenomena, modified gravity) can produce the observed correlation and how they might be distinguished.

Scale dependence: Investigate whether the correlation exhibits scale dependence that might point to specific interaction ranges or screening mechanisms.

This open approach reflects the proper role of phenomenological frameworks: to provide structured ways to interrogate data about fundamental questions, without prematurely committing to specific theoretical interpretations. The value of our framework lies not in whether the specific parameterizations we propose are correct, but in whether they enable decisive tests of the underlying concept.

9. Conclusions

We have presented a complete phenomenological framework centered on the correlation between dark energy dynamics and structure growth. Key achievements include establishing the theoretical foundations by demonstrating that the linear w-γ relation corresponds to a specific interacting dark sectors model that respects energy-momentum conservation; developing a complete parameterization (Equation 6) that cleanly separates structure-dependent coupling from background evolution while enabling redshift-dependent interactions, including a phenomenologically motivated piecewise form aligned with structure formation history; providing a detailed hierarchical Bayesian testing roadmap with concrete implementation guidelines; offering quantitative forecasts that show upcoming surveys will deliver decisive tests with well-defined detection thresholds; identifying distinctive, testable signatures that differentiate the framework from alternative approaches; and maintaining appropriate scientific openness by emphasizing that our proposed parameterizations serve as testable hypotheses within a broader program for exploring dark energy–structure correlations.

Whether future observations ultimately confirm or refute the w-γ correlation, testing this framework will advance our understanding of dark energy and its potential connection to cosmic structure. In particular, if oscillatory features in

w(

z) persist in future datasets [

24], our framework provides a structured way to assess whether they arise from a redshift-dependent coupling to structure growth, offering a physically motivated alternative to purely phenomenological oscillatory parameterizations. The coming decade of cosmological surveys offers an unprecedented opportunity to perform these tests with the statistical power needed for definitive conclusions.

Author Contributions

T.Z. conceived the study, developed the theoretical framework, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

This is a theoretical perspective article. All observational data needed to test the proposed framework are publicly available from the cited surveys.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the DESI, Euclid, Planck, and Pantheon+ collaborations for their pioneering observational work. The public results and cosmological constraints from these surveys have directly informed and motivated the theoretical framework developed in this Perspective. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which has improved the presentation of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix A: Energy-Momentum Conservation Derivation

Appendix A.1 General Formalism for Interacting Fluids

Appendix A.4 Note on Piecewise Parameterizations

The phenomenological piecewise parameterization of

η(

z)proposed in

Section 3.4. (II) (e.g., constant for

z<0.5, oscillatory for 0.5≤

z≤1.5) may introduce discontinuities in

η(

z)at the transition redshifts. It is crucial to note that the conservation equations (A2) are satisfied for any functional form of

η(

z), as the derivation in A.2 shows that the interaction term

Q0 depends on

η(

z)and its time derivative

(

z). Therefore, even a piecewise-defined

η(

z)will conserve energy-momentum within each continuous segment. The potential discontinuities at the boundaries represent instantaneous transitions in the coupling mechanism, which are phenomenologically acceptable as approximations of rapid physical transitions. In numerical implementations, these transitions can be smoothed over a very narrow redshift range to ensure stability while preserving the essential physical behavior captured by the piecewise approach.

References

- Y. Cai, X. Ren, T. Qiu, M. Li and X. Zhang, “The Quintom theory of dark energy after DESI DR2,” (2025) arXiv:2505.24732.

- G. Gu, X. Wang, Y. Wang, G.-B. Zhao et al. (DESI Collaboration), “Dynamical dark energy in light of the DESI DR2 baryonic acoustic oscillations measurements,” Nature Astron. 9 (2025) 1879-1889. [CrossRef]

- D. Anbajagane, C. Chang, A. Drlica-Wagner, C. Y. Tan et al., “The Dark Energy Camera All Data Everywhere cosmic shear project V: Constraints on cosmology and astrophysics from 270 million galaxies across 13,000 deg² of the sky,” (2024); arXiv:2509.03582v2.

- M. Abdul Karim, J. Aguilar, S. Ahlen, S. Alam, L. Allen et al. (DESI Collaboration), “DESI DR2 Results II: Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations and Cosmological Constraints,” (2025); arXiv:2503.14738. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration, “Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters,” Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020); arXiv:1807.06209.

- A. G. Riess et al., “A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km/s/Mpc Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team,” Astrophys. J. Lett. 934, L7 (2022); arXiv:2112.04510. [CrossRef]

- A. Heymans et al. (DES Collaboration), “KiDS-1000 Cosmology: Multi-probe weak gravitational lensing and spectroscopic galaxy clustering constraints,” Astron. Astrophys. 646, A140 (2021); arXiv:2007.15632. [CrossRef]

- DES Collaboration, “Dark Energy Survey Year 3 results: Cosmological constraints from galaxy clustering and weak lensing,” Phys. Rev. D 105, 023520 (2022); arXiv:2105.13549. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T. “An Adaptive Universe Framework Perspective: Towards Testing the Intrinsic Link Between Dark Energy and Structure Growth (Version 3),”Zenodo (2026). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T. “The Cosmic Operating System: Decoding the Unified Logic of Everything’s Operation (Version 2),” Zenodo (2026). [CrossRef]

- E. V. Linder, “Growth of structure in the concordance cosmology,” Phys. Rev. D 72, 043529 (2005); arXiv:astro-ph/0507263. [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration. “The DESI Experiment Part I: Science,Targeting, and Survey Design.” (2024); arXiv:2404.03000.

- Scolnic, D., et al. “The Pantheon+ Analysis: The Full Data Set and Light-curve Release.” Astrophysical Journal 938, 113 (2022); arXiv:2112.03863. [CrossRef]

- Euclid Collaboration. “Euclid preparation: VII. Forecast validation for Euclid cosmological probes.” Astronomy & Astrophysics 647, A117 (2021); arXiv:2010.11288.

- CMB-S4 Collaboration. “CMB-S4 Science Book, First Edition.” (2019); arXiv:1907.04473.

- W. J. Handley, M. P. Hobson and A. N. Lasenby, “PolyChord: nested sampling for cosmology,” Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 453, 4, 4384–4398 (2015); arXiv:1502.01856.

- J. Buchner, “UltraNest: a robust, general purpose Bayesian inference engine,” (2021); arXiv:2101.09604. [CrossRef]

- E. Krause et al., “Dark Energy Survey Year 3 results: Cosmological constraints from cluster abundances and weak lensing,” Phys. Rev. D 107, 2, 023531 (2023); arXiv:2205.12948.

- R. E. Kass and A. E. Raftery, “Bayes Factors,” J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 430, 773–795 (1995). [CrossRef]

- V. Poulin, T. L. Smith, T. Karwal and M. Kamionkowski, “Early Dark Energy can Resolve the Hubble Tension,” Phys. Rev. D 107, 12, 123538 (2023); arXiv:2302.09032. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Ferreira, “Cosmological Tests of Gravity,” Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 57, 335–374 (2019); DOI:10.1146/annurev-astro-091918-104423. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang et al., “Testing gravity on cosmological scales with the EG statistic,” Phys. Rev. D 103, 063517 (2021); arXiv:2010.07195.

- A. Gómez-Valent, V. Pettorino and L. Amendola, “Update on coupled dark energy and the H0 tension,” Phys. Rev. D 106, 103530 (2022); arXiv:2207.14487. [CrossRef]

- P. Creminelli, G. Tambalo, F. Vernizzi and V. Yingcharoenrat, “Resonant Decay of Gravitational Waves into Dark Energy,” JCAP 03, 052 (2020); arXiv:1910.14035. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Handley, M. P. Hobson and A. N. Lasenby, “PolyChord: nested sampling for cosmology,” Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 453, 4384–4398 (2015) ; arXiv:1502.01856. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Philcox et al., “DESI forecasts for reconstructing the growth of structure,” Phys. Rev. D 103, 023538 (2021); arXiv:2006.10035. [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration, “The DESI Experiment Part I: Science,Targeting, and Survey Design,” (2024); arXiv:2404.03000.

- Euclid Collaboration. “Euclid preparation: VII. Forecast validation for Euclid cosmological probes.” Astronomy & Astrophysics 647, A117 (2021); arXiv:2010.11288.

- CMB-S4 Collaboration, “CMB-S4 Science Book, First Edition,” (2019); arXiv:1907.04473.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).