Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

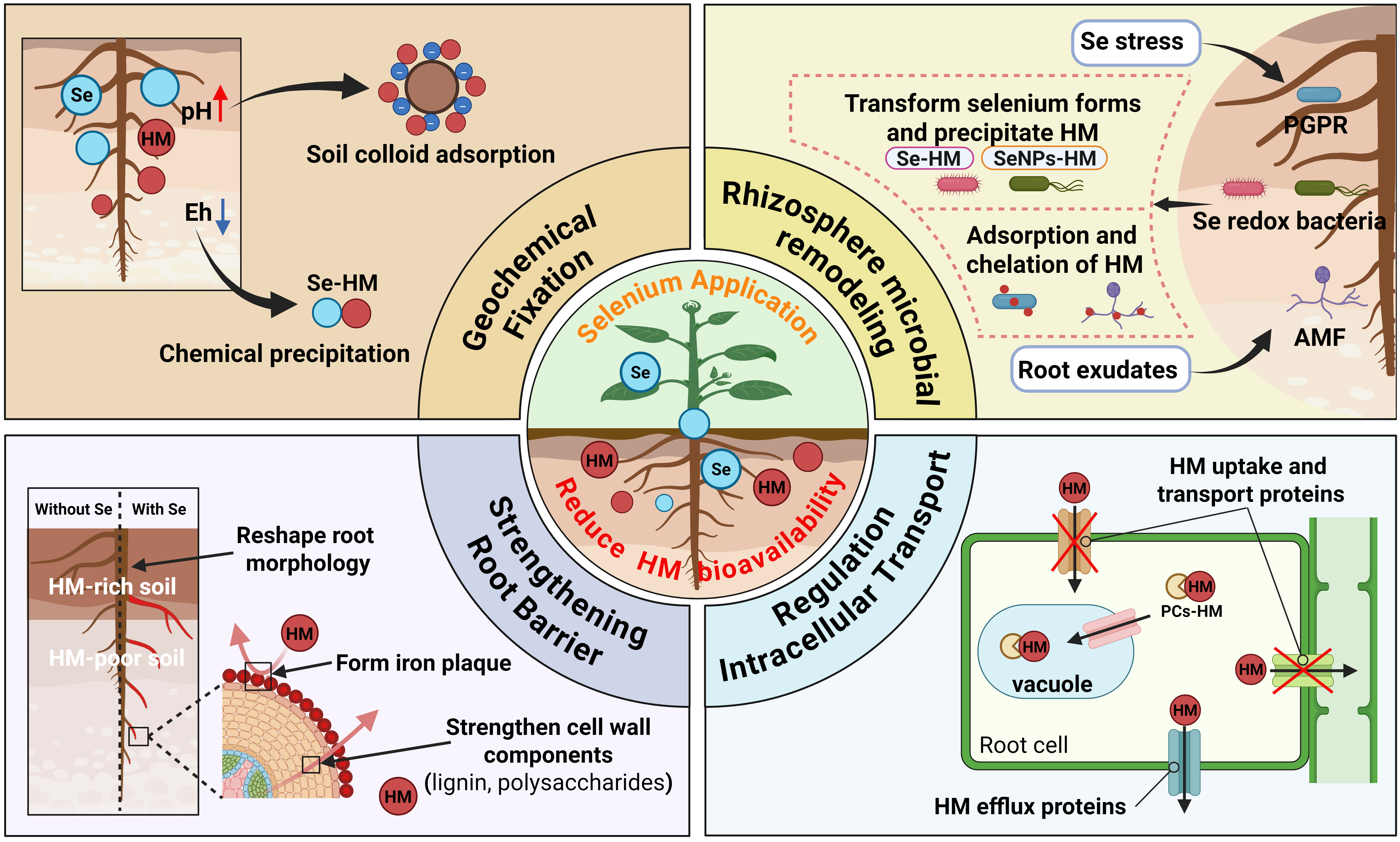

2. Geochemical Immobilization of HMs by Se

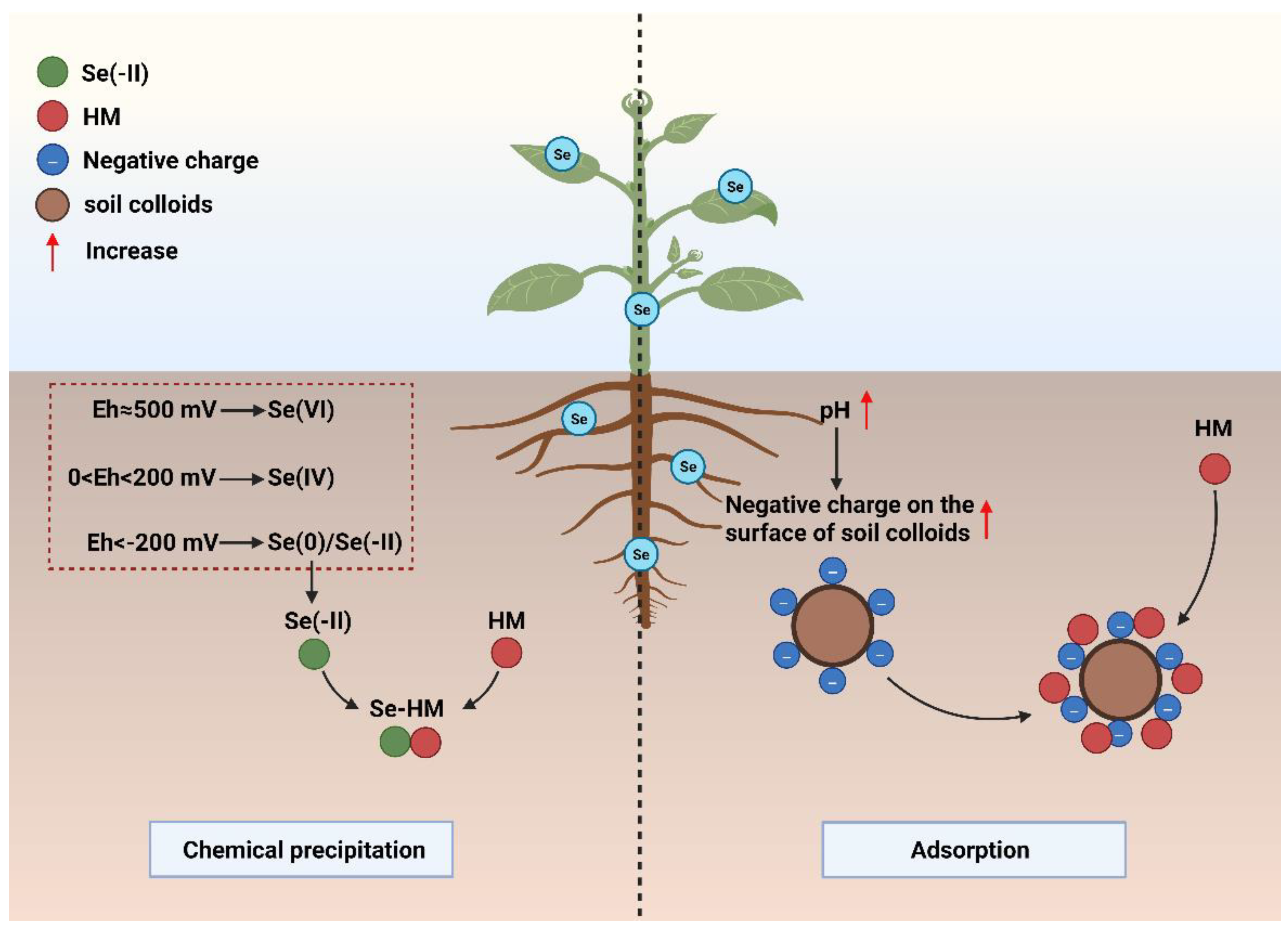

2.1. Effect of Eh on Chemical Precipitation of Se and HMs

2.2. Effect of Rhizosphere pH on HM Adsorption by Soil Colloids

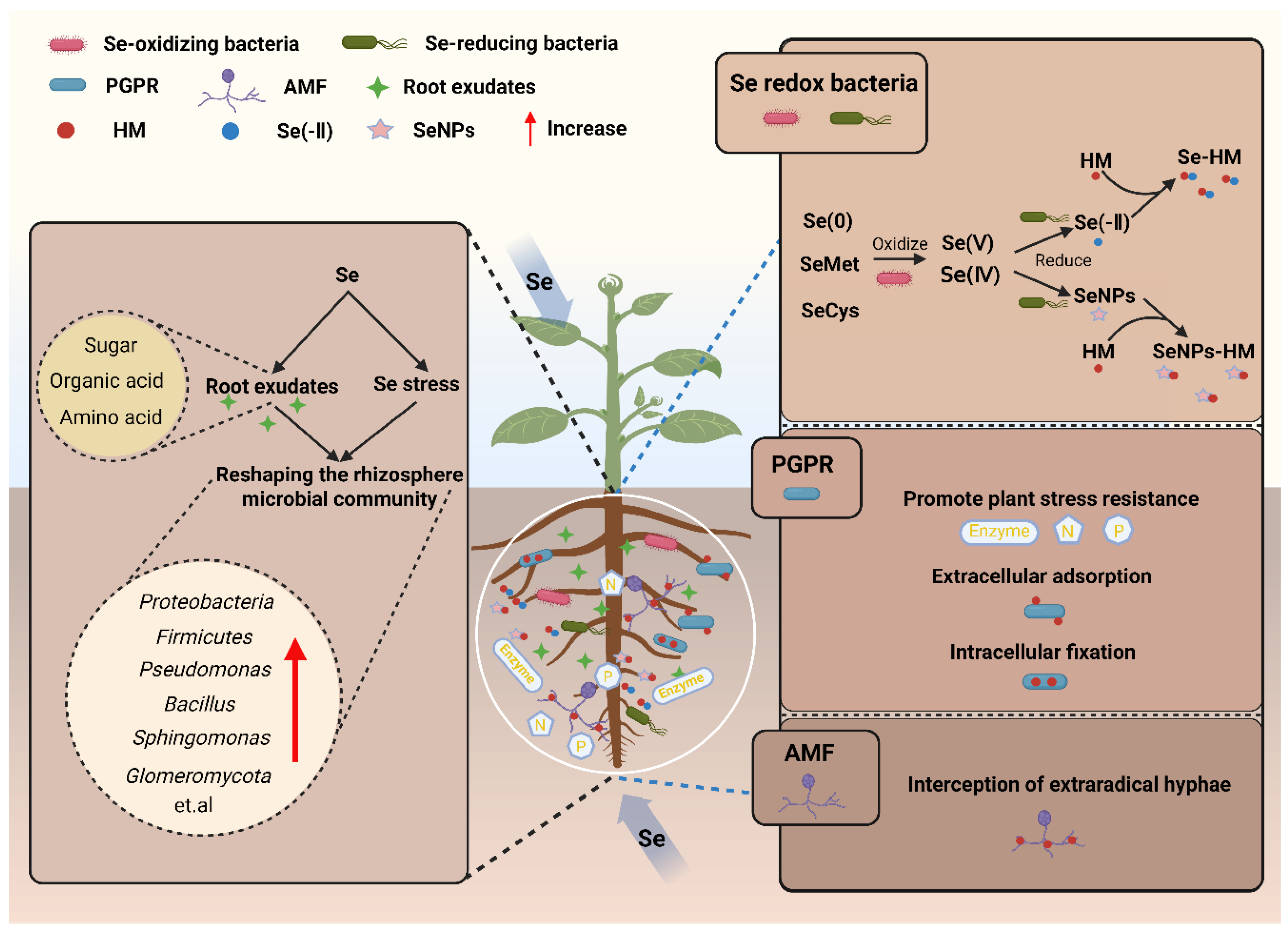

3. Rhizosphere Microbe-Mediated Immobilization of HMs by Se

3.1. Se-Driven Construction of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities

3.2. Rhizosphere Microbe-Mediated Immobilization of HMs

3.2.1. HM Immobilization via Microbial Regulation of Se Speciation

3.2.2. Other Microbe-Mediated HM Immobilization Mechanisms

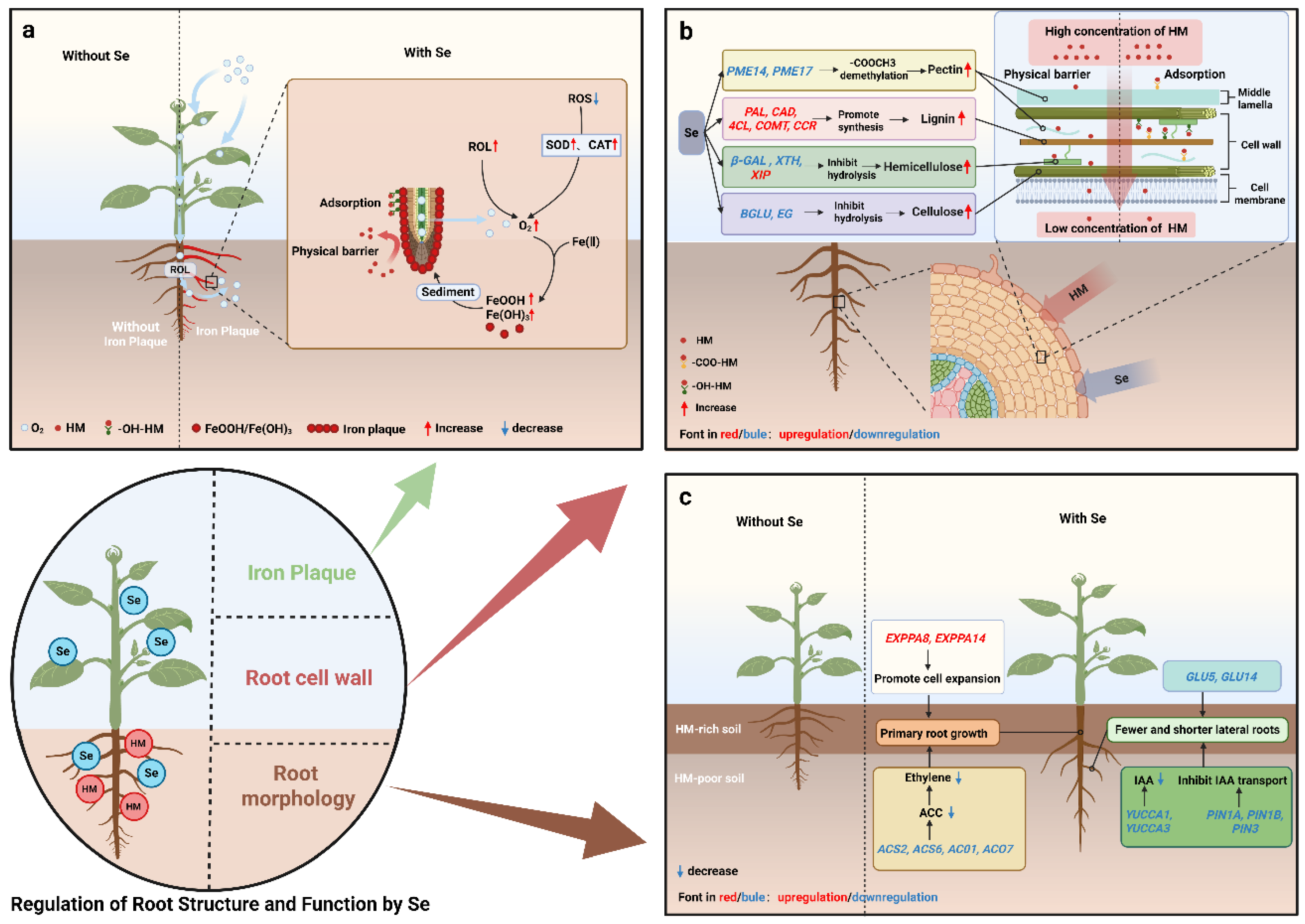

4. Regulation of Plant Root Structure and Function by Se

4.1. Se-Induced Formation of Root Iron Plaque

4.2. Se Reshapes Root Morphology to Avoid HM Pollution

4.3. Se Enhances the HM Barrier Capacity of Root Cell Walls

4.3.1. Se Promotes Lignin Synthesis in Root Cell Walls

4.3.2. Se Increases Cell Wall Polysaccharide Content

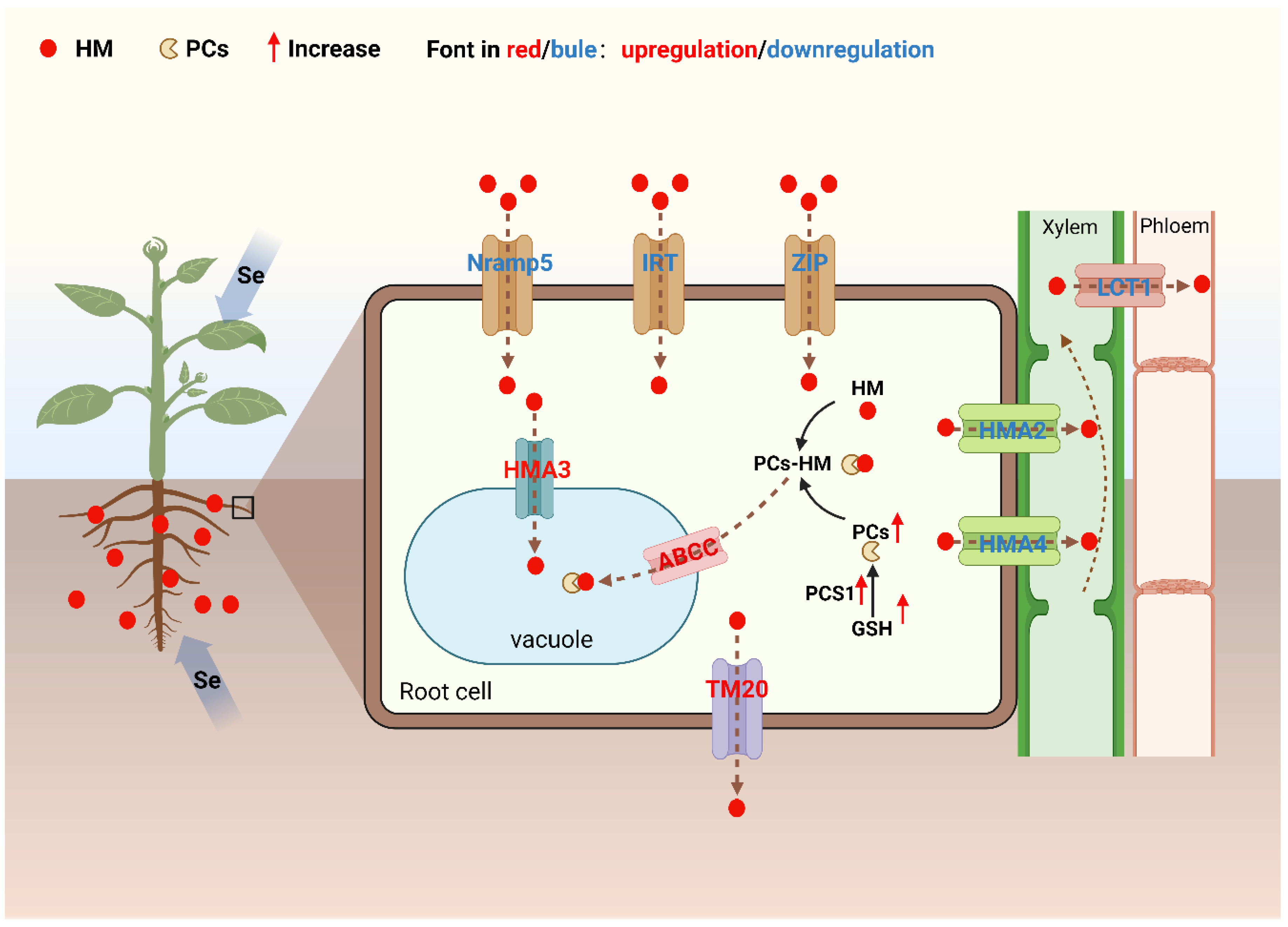

5. Se Regulates HM Transport in Root Cells

5.1. Se Inhibits HM Uptake and Transport in Root Cells

5.2. Se Promotes Chelation and Compartmentalization of HMs in Root Cells

5.2.1. Se Enhances HM Chelation Capacity of Root Cells

5.2.2. Se Activates Vacuolar Membrane Transporters to Enhance Compartmentalization Efficiency

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Omotayo, A. O.; Omotayo, O. P., Potentials of microbe-plant assisted bioremediation in reclaiming heavy metal polluted soil environments for sustainable agriculture. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2024, 22, 100396. [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Jia, X.; Wang, L.; McGrath, S. P.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.; Bank, M. S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J., Global soil pollution by toxic metals threatens agriculture and human health. Science 2025, 388(6744), 316-321. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xie, L.; Hao, S.; Zhou, X., Application of selenium to reduce heavy metal(loid)s in plants based on meta-analysis. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143150. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, M. C.; Capozzi, F.; Amitrano, C.; Giordano, S.; Arena, C.; Spagnuolo, V., Performance of three cardoon cultivars in an industrial heavy metal-contaminated soil: Effects on morphology, cytology and photosynthesis. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2018, 351, 131-137. [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, J.; Zhan, H.; Xiao, Y.; Cai, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Long, L.; Yang, G., Effects of complex pollution by microplastics and heavy metals on soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities under alternate wetting and drying conditions. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 458, 131989. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H. T. T.; Hang, N. T. T.; Nguyen, X. C.; Nguyen, N. T. M.; Truong, H. B.; Liu, C.; La, D. D.; Kim, S. S.; Nguyen, D. D., Toxic metals in rice among Asian countries: A review of occurrence and potential human health risks. Food Chemistry 2024, 460, 140479. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Gong, T.; Liang, P., Heavy metal exposure and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research 2024, 134(9), 1160-1178. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Li, R.; Liu, D.; Lu, H.; He, Z.; Gu, S., Comparative neurotoxic effects and mechanism of cadmium chloride and cadmium sulfate in neuronal cells. Environment International 2025, 203, 109749. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hong, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Su, J.; Han, L.; Zhang, J.; Niu, B., Unveiling the metal mutation nexus: Exploring the genomic impacts of heavy metal exposure in lung adenocarcinoma and colorectal cancer. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 461, 132590. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Lin, Y.; Lin, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, W.; Chen, B.; Chen, T., Traditional Chinese medicine active ingredients-based selenium nanoparticles regulate antioxidant selenoproteins for spinal cord injury treatment. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20(1), 278. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Elizari, E.; Raza, A.; Encío, I.; Sharma, A. K.; Sanmartín, C.; Plano, D., Seleno-warfare against cancer: Decoding antitumor activity of novel acylselenoureas and Se-acylisoselenoureas. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16(2), 272. [CrossRef]

- Rocca, C.; Pasqua, T.; Boukhzar, L.; Anouar, Y.; Angelone, T., Progress in the emerging role of selenoproteins in cardiovascular disease: focus on endoplasmic reticulum-resident selenoproteins. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2019, 76(20), 3969-3985. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. D.; Droz, B.; Greve, P.; Gottschalk, P.; Poffet, D.; McGrath, S. P.; Seneviratne, S. I.; Smith, P.; Winkel, L. H., Selenium deficiency risk predicted to increase under future climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114(11), 2848-2853. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Han, Y.; Zhan, T.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J., Selenium deficiency-induced redox imbalance leads to metabolic reprogramming and inflammation in the liver. Redox Biology 2020, 36, 101519. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, N.; Jin, H., Foliar application of biosynthetic nano-selenium alleviates the toxicity of Cd, Pb, and Hg in Brassica chinensis by inhibiting heavy metal adsorption and improving antioxidant system in plant. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 240, 113681. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, W.; Janda, T.; Molnár, Z., Unveiling the significance of rhizosphere: Implications for plant growth, stress response, and sustainable agriculture. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 206, 108290. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qin, X.; Huang, R.; Liang, X., Selenium application alters soil cadmium bioavailability and reduces its accumulation in rice grown in Cd-contaminated soil. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25(31), 31175-31182. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Cao, B.; Zhang, Y., Foliar application of selenium and gibberellins reduce cadmium accumulation in soybean by regulating interplay among rhizosphere soil metabolites, bacteria community and cadmium speciation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 476, 134868. [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Fan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Peng, M., Dynamic role of selenium in soil–plant-microbe systems: Mechanisms, biofortification, and environmental remediation. Plant and Soil 2025, 515, 1085–1105. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.; Goswami, L.; Lee, J.; Sonne, C.; Brown, R. J. C.; Kim, K.-H., Selenium in soil-microbe-plant systems: Sources, distribution, toxicity, tolerance, and detoxification. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52(13), 2383-2420. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Ye, J.; Zeng, J.; Chen, L.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C., Selenium species transforming along soil–plant continuum and their beneficial roles for horticultural crops. Horticulture Research 2023, 10(2), uhac270. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lombi, E.; Stroud, J. L.; McGrath, S. P.; Zhao, F., Selenium Speciation in Soil and Rice: Influence of Water Management and Se Fertilization. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2010, 58(22), 11837-11843. [CrossRef]

- Nakamaru, Y. M.; Altansuvd, J., Speciation and bioavailability of selenium and antimony in non-flooded and wetland soils: A review. Chemosphere 2014, 111, 366-371. [CrossRef]

- Mal, J.; Sinharoy, A.; Lens, P. N. L., Simultaneous removal of lead and selenium through biomineralization as lead selenide by anaerobic granular sludge. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 420, 126663. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Camara, A. Y.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, H., Arsenic uptake and accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) with selenite fertilization and water management. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 156, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, L.; Qi, S.; Yin, X., The threshold effect between the soil bioavailable molar Se:Cd ratio and the accumulation of Cd in corn (Zea mays L.) from natural Se-Cd rich soils. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 688, 1228-1235. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dang, F.; Evans, R. D.; Zhong, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, D., Mechanistic understanding of MeHg-Se antagonism in soil-rice systems: the key role of antagonism in soil. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 19477. [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Xie, P.; Ji, H., The optimum pH and Eh for simultaneously minimizing bioavailable cadmium and arsenic contents in soils under the organic fertilizer application. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 711, 135229. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Camara, A. Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, T.; Zhu, L.; Li, H., Cadmium dynamics in soil pore water and uptake by rice: Influences of soil-applied selenite with different water managements. Environmental Pollution 2018, 240, 523-533. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ding, C.; Guo, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X., Underlying mechanisms and effects of hydrated lime and selenium application on cadmium uptake by rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24(23), 18926-18935. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, C. E.; James, B. R.; Santelli, C. M., Persistent Bacterial and Fungal Community Shifts Exhibited in Selenium-Contaminated Reclaimed Mine Soils. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2018, 84(16), e01394-18. [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Wu, C.; Tang, Y.; Shi, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Cao, J.; Zhao, X., Selenium and Bacillus proteolyticus SES synergistically enhanced ryegrass to remediate Cu–Cd–Cr contaminated soil. Environmental Pollution 2023, 323, 121272. [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Shi, G.; Hu, C. X.; Wang, X.; Nie, M.; Cai, M.; Cheng, Q.; Zhao, X. H., Selenium improved the combined remediation efficiency of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and ryegrass on cadmium-nonylphenol co-contaminated soil. Environmental pollution 2021, 287, 117552. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, W.; Xu, J., Comparative physiological and soil microbial community structural analysis revealed that selenium alleviates cadmium stress in Perilla frutescens. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1022935. [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, A. L.; Johansen, J.; Stæger, F. F.; Nielsen, D. S.; Mulvad, G.; Hanghøj, K.; Rasmussen, S.; Hansen, T.; Albrechtsen, A., Gut heavy metal and antibiotic resistome of humans living in the high Arctic. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1493803. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, D.; Hu, C.; Du, X.; Liang, L.; Wang, X.; Shi, G.; Han, C.; Tang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Yi, C.; Zhao, X., Bacteria from the rhizosphere of a selenium hyperaccumulator plant can improve the selenium uptake of a non-hyperaccumulator plant. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2024, 60(7), 987-1008. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Sun, W.; Chen, Q., Bioavailable metal(loid)s and physicochemical features co-mediating microbial communities at combined metal(loid) pollution sites. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127619. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; An, Q.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, C., Nanoselenium integrates soil-pepper plant homeostasis by recruiting rhizosphere-beneficial microbiomes and allocating signaling molecule levels under Cd stress. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 432, 128763. [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G. M., Metals, minerals and microbes: geomicrobiology and bioremediation. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2010, 156(3), 609-643. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W. J.; Manter, D. K., Reduction of selenite to elemental red selenium by Pseudomonas sp. Strain CA5. Current microbiology 2009, 58(5), 493-8. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W. J.; Kuykendall, L. D.; Manter, D. K., Rhizobium selenireducens sp. nov.: a selenite-reducing alpha-Proteobacteria isolated from a bioreactor. Current microbiology 2007, 55(5), 455-60. [CrossRef]

- Khoei, N. S.; Lampis, S.; Zonaro, E.; Yrjälä, K.; Bernardi, P.; Vallini, G., Insights into selenite reduction and biogenesis of elemental selenium nanoparticles by two environmental isolates of Burkholderia fungorum. New Biotechnology 2017, 34, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, G., Draft genomic sequence of a selenite-reducing bacterium, Paenirhodobacter enshiensis DW2-9T. Standards in Genomic Sciences 2015, 10(1), 38. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Su, J.; Wang, L.; Yao, R.; Wang, D.; Deng, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, G.; Rensing, C., Selenite reduction by the obligate aerobic bacterium Comamonas testosteroni S44 isolated from a metal-contaminated soil. BMC Microbiology 2014, 14(1), 204. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R. R.; Prajapati, S.; Das, J.; Dangar, T. K.; Das, N.; Thatoi, H., Reduction of selenite to red elemental selenium by moderately halotolerant Bacillus megaterium strains isolated from Bhitarkanika mangrove soil and characterization of reduced product. Chemosphere 2011, 84(9), 1231-1237. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Yao, R.; Wang, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, G.; Zheng, S., Reduction of selenite to Se(0) nanoparticles by filamentous bacterium Streptomyces sp. ES2-5 isolated from a selenium mining soil. Microbial Cell Factories 2016, 15(1), 157. [CrossRef]

- Eswayah Abdurrahman, S.; Smith Thomas, J.; Gardiner Philip, H. E., Microbial transformations of selenium species of relevance to bioremediation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2016, 82(16), 4848-4859. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, S., Contributions of selenium-oxidizing bacteria to selenium biofortification and cadmium bioremediation in a native seleniferous Cd-polluted sandy loam soil. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 272, 116081. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Guo, C.; Lu, G.; Yi, X.; Zhu, L.; Dang, Z., Bioaccumulation characterization of cadmium by growing Bacillus cereus RC-1 and its mechanism. Chemosphere 2014, 109, 134-142. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Nie, Z.; Tao, Z.; Peng, H.; Shi, H.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H., Combined application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and selenium fertilizer increased wheat biomass under cadmium stress and shapes rhizosphere soil microbial communities. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24(1), 359. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, W.; Pang, F., Selenium in soil–plant-microbe: A review. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2022, 108(2), 167-181. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Tian, X., Nano-selenium modulates heavy metal transport and toxicity in soil-plant systems. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13(5), 118164. [CrossRef]

- Lampis, S.; Zonaro, E.; Bertolini, C.; Cecconi, D.; Monti, F.; Micaroni, M.; Turner, R. J.; Butler, C. S.; Vallini, G., Selenite biotransformation and detoxification by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SeITE02: Novel clues on the route to bacterial biogenesis of selenium nanoparticles. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2017, 324, 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Xu, J.; Dai, Z.; Elyamine, A. M.; Huang, W.; Han, D.; Dang, B.; Xu, Z.; Jia, W., Selenium in soil-plant system: Transport, detoxification and bioremediation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 452, 131272. [CrossRef]

- Tolu, J.; Bouchet, S.; Helfenstein, J.; Hausheer, O.; Chékifi, S.; Frossard, E.; Tamburini, F.; Chadwick, O. A.; Winkel, L. H. E., Understanding soil selenium accumulation and bioavailability through size resolved and elemental characterization of soil extracts. Nature Communications 2022, 13(1), 6974. [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, H., Harnessing the rhizosphere microbiome for selenium biofortification in plants: mechanisms, applications and future perspectives. Microorganisms 2025, 13(6), 1234. [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, L.; Wei, A.; Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Zheng, S., Selenium-oxidizing Agrobacterium sp. T3F4 decreases arsenic uptake by Brassica rapa L. under a native polluted soil. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2024, 138, 506-515. [CrossRef]

- Belimov, A. A.; Zinovkina, N. Y.; Safronova, V. I.; Litvinsky, V. A.; Nosikov, V. V.; Zavalin, A. A.; Tikhonovich, I. A., Rhizobial ACC deaminase contributes to efficient symbiosis with pea (Pisum sativum L.) under single and combined cadmium and water deficit stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 167, 103859. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C., Selenium availability in tea: Unraveling the role of microbiota assembly and functions. The Science of the total environment 2024, 952, 175995. [CrossRef]

- Szuba, A.; Karliński, L.; Krzesłowska, M.; Hazubska-Przybył, T., Inoculation with a Pb-tolerant strain of Paxillus involutus improves growth and Pb tolerance of Populus × canescens under in vitro conditions. Plant and Soil 2017, 412(1), 253-266. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Hu, Y.; Lv, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhen, X.; Chen, B., Chromium immobilization by extra- and intraradical fungal structures of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 316, 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ding, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X., Selenium enhances iron plaque formation by elevating the radial oxygen loss of roots to reduce cadmium accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 398, 122860. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, X.; Shen, H., Root iron plaque alleviates cadmium toxicity to rice (Oryza sativa) seedlings. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 161, 534-541. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, S.; Wan, N.; Feng, B.; Wang, Q.; Huang, K.; Fang, Y.; Bao, Z.; Xu, F., Iron plaque effects on selenium and cadmium stabilization in Cd-contaminated seleniferous rice seedlings. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30(9), 22772-22786. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y., Effect of iron plaque and selenium on mercury uptake and translocation in rice seedlings grown in solution culture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26(14), 13795-13803. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ding, C.; Guo, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X., The optimum Se application time for reducing Cd uptake by rice (Oryza sativa L.) and its mechanism. Plant and Soil 2018, 431(1), 231-243. [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Rensing, C.; Wu, Z.; Ni, R.; Zheng, S., Underlying mechanisms responsible for restriction of uptake and translocation of heavy metals (metalloids) by selenium via root application in plants. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123570. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L.; Kong, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Wan, Y., Selenite and selenate showed contrasting impacts on the fate of arsenic in rice (Oryza sativa L.) regardless of the formation of iron plaque. Environmental Pollution 2022, 312, 120039. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Rensing, C.; Dai, J.; Fekih, I. B.; Wang, L.; Mazhar, S. H.; Kehinde, S. B.; Xu, J.; Su, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, R.; Fan, Z.; Feng, R., Roles of root cell wall components and root plaques in regulating elemental uptake in rice subjected to selenite and different speciation of antimony. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 163, 36-44. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, W. C.; Tam, N. F. Y.; Ye, Z., Effects of root morphology and anatomy on cadmium uptake and translocation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Journal of Environmental Sciences 2019, 75, 296-306. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Xin, J.; Dai, H.; Liu, A.; Zhou, W.; Yi, Y.; Liao, K., Root morphological responses of three hot pepper cultivars to Cd exposure and their correlations with Cd accumulation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2015, 22(2), 1151-1159. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Feng, R.; Wang, R.; Guo, J.; Zheng, X., A dual effect of Se on Cd toxicity: evidence from plant growth, root morphology and responses of the antioxidative systems of paddy rice. Plant and Soil 2014, 375, 289-301. [CrossRef]

- Malheiros, R. S. P.; Costa, L. C.; Ávila, R. T.; Pimenta, T. M.; Teixeira, L. S.; Brito, F. A. L.; Zsögön, A.; Araújo, W. L.; Ribeiro, D. M., Selenium downregulates auxin and ethylene biosynthesis in rice seedlings to modify primary metabolism and root architecture. Planta 2019, 250(1), 333-345. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; You, L.; Yang, G.; Rensing, C.; Feng, R., Selenite reduced uptake/translocation of cadmium via regulation of assembles and interactions of pectins, hemicelluloses, lignins, callose and Casparian strips in rice roots. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 448(15), 130812. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, C.; Ma, J.; Wu, Y.; Kang, L.; An, Q.; Zhang, J.; Deng, K.; Li, J.; Pan, C., Nanoselenium transformation and inhibition of cadmium accumulation by regulating the lignin biosynthetic pathway and plant hormone signal transduction in pepper plants. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19(1), 316. [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Jing, R.; Qin, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Q., The role and transcriptomic mechanism of cell wall in the mutual antagonized effects between selenium nanoparticles and cadmium in wheat. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 472, 134549. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lipton, A. S.; Munson, C. R.; Ma, Y.; Johnson, K. L.; Murray, D. T.; Scheller, H. V.; Mortimer, J. C., Elongated galactan side chains mediate cellulose-pectin interactions in engineered Arabidopsis secondary cell walls. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 2023, 115(2), 529-545. [CrossRef]

- Loix, C.; Huybrechts, M.; Vangronsveld, J.; Gielen, M.; Keunen, E.; Cuypers, A., Reciprocal Interactions between Cadmium-Induced Cell Wall Responses and Oxidative Stress in Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 1867. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, Z., Mechanisms of cadmium phytoremediation and detoxification in plants. The Crop Journal 2021, 9(3), 521-529. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Tang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Ding, Y., The cell wall functions in plant heavy metal response. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025, 299, 118326. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, C.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Cai, M.; Jia, W.; Zhao, X., Selenium reduces cadmium accumulation in seed by increasing cadmium retention in root of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 158, 161-170. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Li, F., Selenium reduces cadmium uptake into rice suspension cells by regulating the expression of lignin synthesis and cadmium-related genes. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 644, 602-610. [CrossRef]

- Barman, F.; Guha, T.; Kundu, R., Exogenous selenium supplements reduce cadmium accumulation and restore micronutrient content in rice grains. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2025, 25(2), 2275-2293. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, M.; Rizwan, M.; Dai, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Hossain, M. M.; Cao, M.; Xiong, S.; Tu, S., Synergistic effect of silicon and selenium on the alleviation of cadmium toxicity in rice plants. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 401, 123393. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Rong, h.; Zhang, X.; Shi, W.; Hong, X.; Liu, W.; Cao, T.; Yu, X.; Yu, Q., Effects and mechanisms of foliar application of silicon and selenium composite sols on diminishing cadmium and lead translocation and affiliated physiological and biochemical responses in hybrid rice (Oryza sativa L.) exposed to cadmium and lead. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126347. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, F.; Hu, Q.; Chang, N.; Qiu, T.; Zeng, Y.; He, H.; White, J. C.; Yang, W.; Fang, L., Exogenous selenium promotes cadmium reduction and selenium enrichment in rice: Evidence, mechanisms, and perspectives. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 476, 135043. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Cui, H.; Fan, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, J., Soil and foliar applications of silicon and selenium effects on cadmium accumulation and plant growth by modulation of antioxidant system and Cd translocation: Comparison of soft vs. durum wheat varieties. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123546. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, S.; Wu, S.; Rao, S.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Cheng, H., Morphological and physiological indicators and transcriptome analyses reveal the mechanism of selenium multilevel mitigation of cadmium damage in Brassica juncea. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12(8), 1583. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhu, B.; Gu, L.; Zeng, T.; Wang, H.; Du, X., Mutation of TaNRAMP5 impacts cadmium transport in wheat. Plant physiology and biochemistry : PPB 2025, 223, 109879. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lv, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, C.; Tao, Q., Peroxidase in plant defense: Novel insights for cadmium accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 474, 134826. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Cao, L.; Zhang, C.; Pan, W.; Wang, W.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Fan, T.; Miao, M.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, S., MYB43 as a novel substrate for CRL4(PRL1) E3 ligases negatively regulates cadmium tolerance through transcriptional inhibition of HMAs in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist 2022, 234(3), 884-901. [CrossRef]

- Ismael, M. A.; Elyamine, A. M.; Zhao, Y. Y.; Moussa, M. G.; Rana, M. S.; Afzal, J.; Imran, M.; Zhao, X. H.; Hu, C. X., Can Selenium and Molybdenum Restrain Cadmium Toxicity to Pollen Grains in Brassica napus? International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19(8). [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Zhou, J.; Cui, H.; Liang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, J., Nodes play a major role in cadmium (Cd) storage and redistribution in low-Cd-accumulating rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 859, 160436. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, B. A.; Rather, M. A.; Bilal, T.; Nazir, R.; Qadir, R. U.; Mir, R. A., Plant hyperaccumulators: a state-of-the-art review on mechanism of heavy metal transport and sequestration. Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, 16 1631378. [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Jia, W.; Dai, Z.; Xu, Z.; Cai, M.; Huang, W.; Han, D.; Dang, B.; Ma, X.; Gao, Y.; Xu, J., Selenium and molybdenum synergistically alleviate chromium toxicity by modulating Cr uptake and subcellular distribution in Nicotiana tabacum L. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 248, 114312. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J. F., Overexpression of OsHMA3 enhances Cd tolerance and expression of Zn transporter genes in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 2014, 65(20), 6013-21. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Cai, X.; Huang, Y.; Feng, H.; Cai, L.; Luo, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Sirguey, C.; Morel, J. L.; Qi, H.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, R., Root Zn sequestration transporter heavy metal ATPase 3 from Odontarrhena chalcidica enhance Cd tolerance and accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 480, 135827. [CrossRef]

| Microbial Species | Microbial Name | Core Function(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Se-reducing Bacteria | Pseudomonas spp | Reduces Se (VI)/Se (IV) to Se (0) or Se (-II) | [40] |

| Rhizobium sp. | Reduces Se (IV) to SeNPs (selenium nanoparticles) | [41] | |

| Burkholderia fungorum | Reduces Se (IV) to SeNPs or Se (-II) | [42] | |

| Paenirhodobacter enshiensis | Reduces Se (IV) to SeNPs | [43] | |

| Comamonas testosteroni S44 | Reduces Se (IV) to Se (0) or Se (-II) | [44] | |

| Bacillus megaterium | Reduces Se (IV)/Se (0) to Se (-II) | [45] | |

| Streptomyces sp. ES2-5 | Reduces Se (IV) to Se (0) nanoparticles | [46] | |

| Thiobacillus ferrooxidans | Reduces Se (0) to Se (-II) | [47] | |

| Bacillus selenitireducens | Reduces Se (IV) to SeNPs | ||

| Se-oxidizing Bacteria | LX-1 | Oxidizes Se (0), SeMet (selenomethionine), and SeCys2 (selenocystine) to Se (IV) | [48] |

| LX-100 | Oxidizes Se (0), SeMet, and SeCys2 to Se (IV) | ||

| T3F4 | Oxidizes Se (0), SeMet, and SeCys2 to Se (IV) | ||

| PGPR (Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria) | Bacillus proteolyticus SES | Enhances HM immobilization by secreting metabolites | [32] |

| Bacillus cereus RC-1 | Adsorbs Cd through the cell wall and chelates Cd via intracellular metallothioneins (MTs) | [49] | |

| AMF (Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi) | Rhizophagus intraradices | Physically intercepts and adsorbs HMs through hyphae | [50] |

| Crop species | Gene | Gene function(s) | Gene expression after Se application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza sativa L. | EXPA8/14 | Promotes elongation of primary root cells | Upregulation | [73] |

| EXPB2/3 | Promotes elongation of primary root cells | |||

| ACS2/6 | Synthesizes ethylene and promotes lateral root development | Downregulation | ||

| ACO1/7 | Synthesizes ethylene and promotes lateral root development | |||

| YUCCA1/3 | Synthesizes auxin and promotes lateral root development | |||

| PIN1A/B | Transports auxin and promotes lateral root formation | |||

| PIN3 | Transports auxin and promotes lateral root formation | |||

| GLU5/14 | Promotes the formation and development of lateral root primordia, increasing the number and length of lateral roots | |||

| XIP | Inhibits xylanase from cleaving xylan chains in hemicellulose | Upregulation | [74] | |

| PME14/17 | Catalyzes pectin demethylation to expose carboxyl groups | Downregulation | ||

| Capsicum annuum L. | PAL | Catalyzes the conversion of phenylalanine to cinnamic acid, providing precursor substances for lignin synthesis | Upregulation | [75] |

| CAD | Involved in lignin monomer synthesis | |||

| 4CL | Catalyzes the conversion of coumaric acid to coumaryl-CoA, providing precursors for lignin synthesis | |||

| COMT | Catalyzes methylation reactions in lignin synthesis | |||

| Triticum aestivum L. | CCR | Catalyzes lignin monomer synthesis | Upregulation | [76] |

| β-GAL | Hydrolyzes galactose residues in hemicellulose and participates in cell wall polysaccharide remodeling | Downregulation | ||

| XTH | Hydrolyzes xyloglucan in hemicellulose | |||

| BGLU | Hydrolyzes cellobiose and decomposes cellulose | |||

| EG | Randomly cleaves cellulose polymer chains and degrades cellulose |

| Crop species | Gene name | Gene function (s) | Gene expression after Se application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza sativa L. | OsNramp5 | Mediates Cd uptake by root cells | Downregulation | [82] |

| OsIRT1 | Mediates Fe and Cd uptake by root cells | |||

| OsIRT2 | Mediates Fe and Cd uptake by root cells | |||

| OsZIP1 | Me diates Fe and Cd uptake by root cells | Downregulation | [83] | |

| OsPCS1 | Promotes the synthesis of phytochelatins (PCs) | Upregulation | ||

| OsHMA2 | Transports root Cd into the xylem | Downregulation | [84] | |

| OsHMA4 | Transports root Cd into the xylem | |||

| OsLCT1 | Transports Cd to leaves and grains | Downregulation | [85] | |

| OsHMA3 | Transports Cd to vacuoles | Upregulation | [86] | |

| Triticum aestivum L. | TaTM20 | Mediates Cd efflux from root cells | Downregulation | [87] |

| Brassica juncea L. | ABCC | Transports PCs-Cd complexes to vacuoles | Upregulation | [88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).