1. Introduction

Toothpaste is an essential component of daily oral hygiene and is widely used across all age groups. Although not intended for ingestion, many of its components can remain in the oral cavity after brushing. The oral mucosa, due to its high permeability and vascularization, enables rapid absorption of substances [

1]. Consequently, ingredients in toothpaste may exert effects beyond the oral cavity, potentially influencing sensitive organs such as the heart. Modern toothpaste formulations contain a range of active and inactive ingredients, such as abrasives, humectants, surfactants, flavoring agents, and preservatives, along with pharmacologically active components targeting specific oral health issues such as tooth sensitivity [

2,

3]. SrCl

2 is a commonly used desensitizing agent that acts by occluding dentinal tubules, thereby reducing fluid movement and neural excitation [

4,

5]. Belong dentistry, SrCl

2 has been shown to alleviate skin irritation [

6,

7], and to promote periodontal cell proliferation and mineralization at low concentrations [

8,

9]. Despite these beneficial effects, concerns have been raised about its safety, particularly with regard to cardiovascular health. Epidemiological studies have linked strontium-based medications to an increased risk of cardiovascular events [

10], although the exact underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Importantly, the direct effects of SrCl

2 on iPSCs and iPSC-CMs have not been investigated.

Potassium carbonate (K

2CO

3) is another ingredient occasionally included in natural or mild toothpaste formulations, though its specific role in these products remain poorly defined. K

2CO

3 is widely used in industrial and pharmaceutical contexts [

11,

12,

13]. However, due to the its alkaline nature, K

2CO

3 may act as a mucosal irritant at high concentrations, suggesting possible biological reactivity [

13]. Its effects on excitable cells, including CMs, are largely unknown, and data on its cardiac safety are currently lacking.

To address these knowledge gaps, the present study investigated the cytotoxic and cardiotoxic effects of SrCl2 and K2CO3 using a murine iPSC-based in vitro model. Cell proliferation and viability were assessed in undifferentiated iPSCs, while functional and molecular endpoints were evaluated in iPSC-CMs. A combination of advanced and innovative analytical tools and techniques, including real-time cell analysis (xCELLigence RTCA Cardio system), multi-electrode array (MEA) recordings, fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS), immunocytochemistry, and quantitative RT-PCR, was employed to characterize both acute and dose-dependent effects. By integrating multiple complementary assays within a physiologically relevant system, this study provides novel insights into the toxicological and functional profiles of SrCl2 and K2CO3. The findings may help refine safety assessments for dental care products and guide future research on potential side effects of topically applied compounds.

2. Results

2.1. Mouse iPSC Maintenance and Cardiac Differentiation

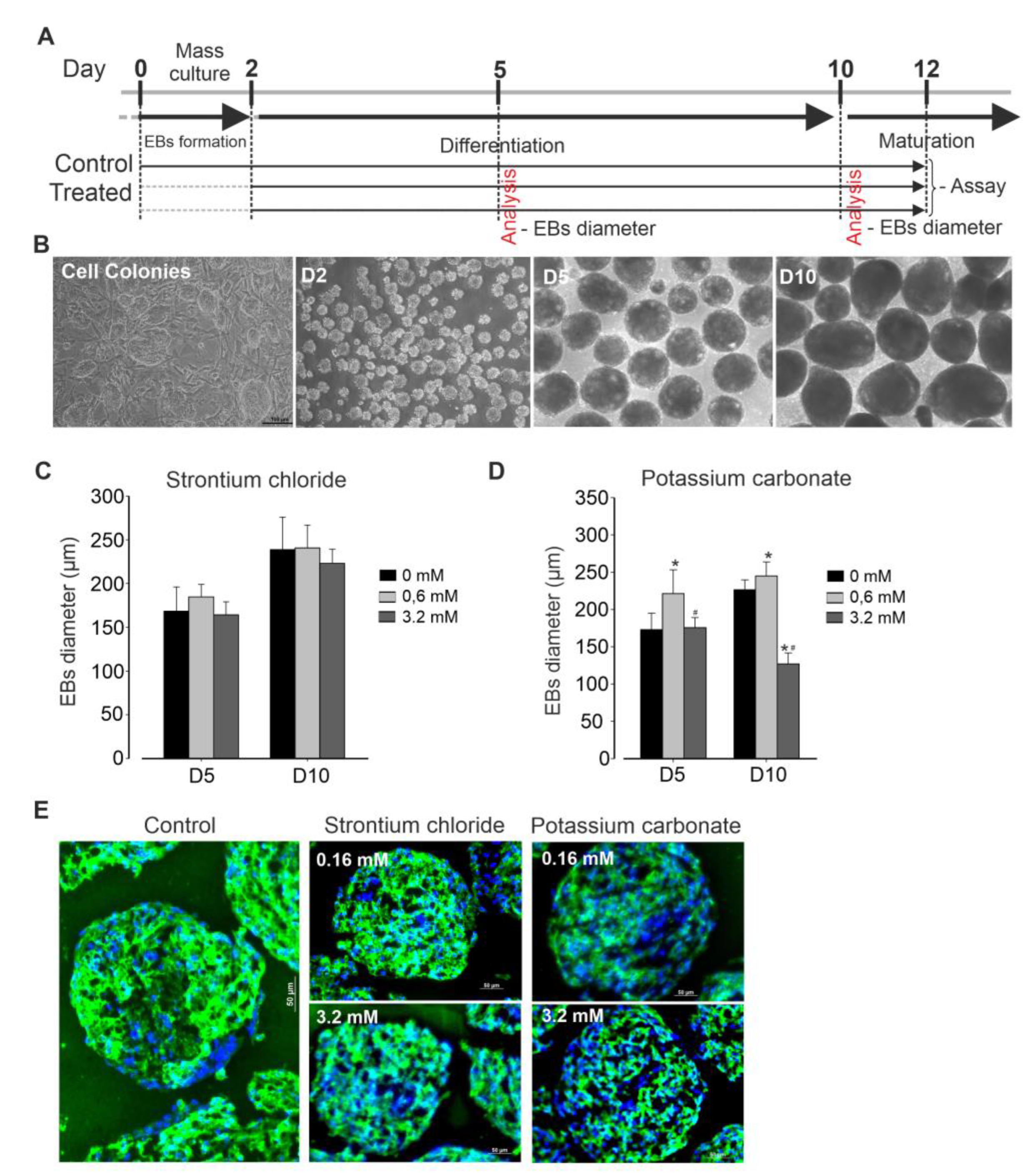

Cell culture protocol is depicted in

Figure 1A. Briefly, murine iPSCs (AT25) were stably maintained on a neomycin-resistant feeder layer, exhibiting typical colony morphology during expansion, with passaging occurring every 2 days. Differentiation was initiated through embryoid body (EB) formation (

Figure 1B) in the presence or absence of various concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. After two days of suspension culture, EBs were successfully formed. These EBs were then exposed to the respective compound treatments and monitored throughout the subsequent period until final analysis. At days 5 and 10 post differentiation, no significant changes in EBs size were observed across all concentrations of SrCl

2 tested, as compared to control conditions (

Figure 1C). In contrast, exposure to K

2CO

3 at low concentration (0.6 mM) resulted in significant increase in EB size. However, at high concentration (3.2 mM), K

2CO

3 induction in EB size, decreasing it to approximately half of the size observed from those in control condition (

Figure 1D. Spontaneous beating of the EBs was generally first observed between day 6 and 8 post-differentiation. Simultaneously, eGFP expression under the myosin heavy chain promoter was detected in beating areas, indicating cardiomyogenic lineage commitment. Immunofluorescence analysis of EB cluster, revealed positive staining for α-actinin, a cardiac-specific marker. As shown in

Figure 2E, expression of α-actinin was less intense in EBs treated with high concentrations of K

2CO

3 compared to controls, suggesting that these treatments may at least in part affect cardiomyogenesis.

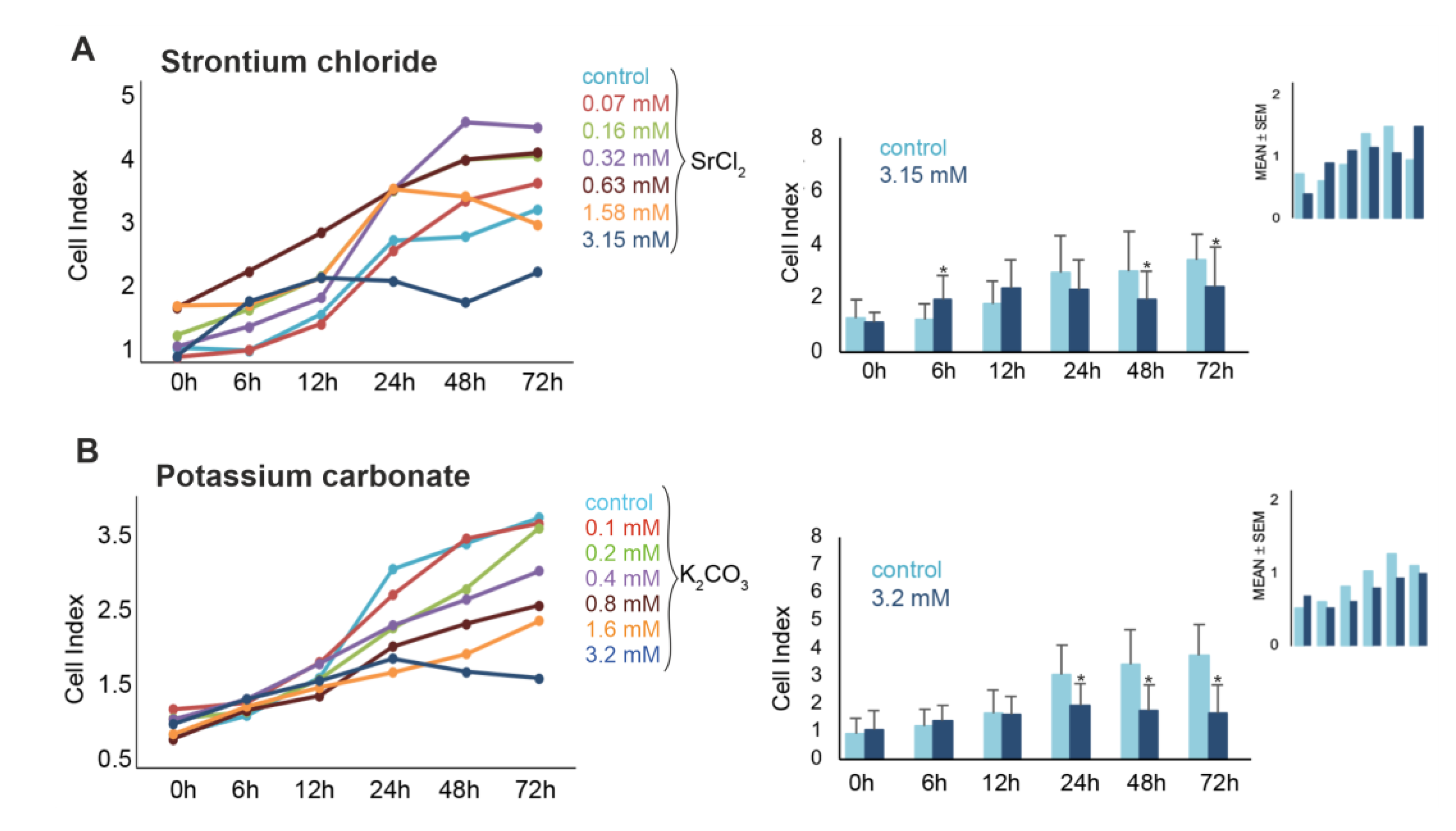

2.2. SrCl2 and K2CO3 Reduce iPSCs Proliferation

The effect of both compounds SrCl₂ and K₂CO

3 on the viability of murine pluripotent stem cells were further examined over a period of 72 h. Real-Time impedance monitoring revealed a biphasic response to SrCl

2 exposure (

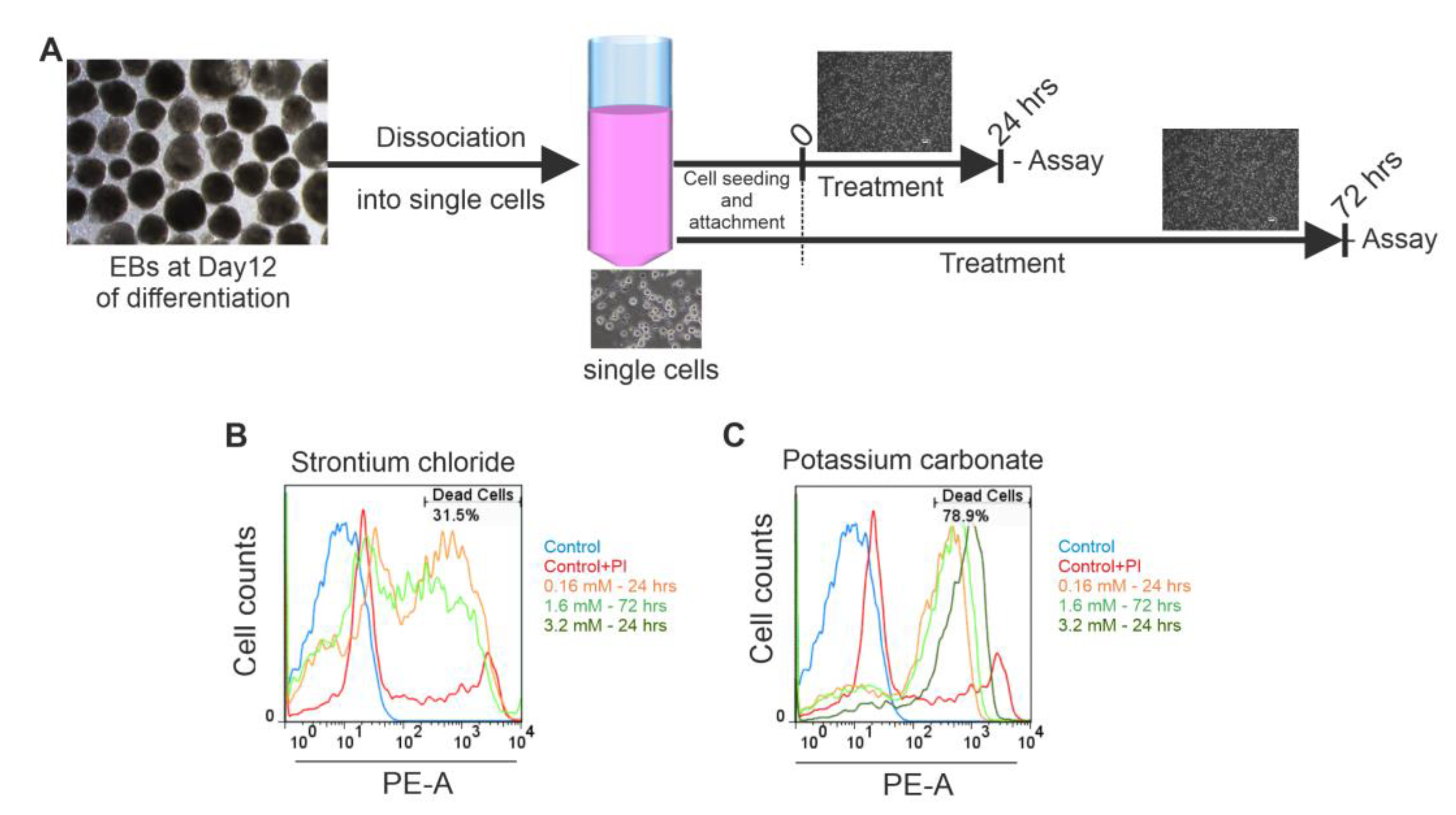

Figure 2A). At lower concentrations (0.07 - 0.63 mM), a transient increase in CI was observed during the first 6 - 12 h. However, higher concentrations (≥ 1.58 mM) induced a progressive decline in CI, with a significant reduction at 3.15 mM (down to ~46% of control at 72 h, p<0.05). Intermediate concentrations (0.16 - 0.63 mM) occasionally exhibited proliferative effects depending on the replicate, suggesting inter-experimental variability. Microscopic analysis confirmed reduced cell density and apoptotic morphology after 3.15 mM treatment. FACS further validated this effect, showing a dose-dependent increase in PI-positive cells from 2.4 % (control) to 12.0 % at 3.15 mM after 72 h (p<0.05).

Exposure to K

2CO

3 resulted in a reproducible, concentration- and time-dependent decrease in cell viability (

Figure 2B). Real-time impedance analysis showed significant CI reductions at 1.6 mM and 3.2 mM K

2CO

3, beginning as early as 24 h and persisting through 72 h. At 3.2 mM, CI values dropped below 50% of the control by 48-72 h (p<0.05), indicating pronounced cytotoxicity. In contrast to SrCl

2, no significant proliferative responses were observed at any concentration of K

2CO

3 before 24 h. Microscopy examination of cells treated with 3.2 mM for 72 h revealed reduced cell density, detachment, and morphological signs of cell damage (data not shown). These findings were further corroborated by FACS data (

Figure 3A-3C), which revealed significant increase in PI-positive cells to 12.7% at 24 h, and 16.2% at 72 h (both p<0.05 vs. control) (

Figure 3B and 3C, confirming the cytotoxic effect. Taken together, these results demonstrate that exposure to K

2CO

3 consistently induced dose-dependent iPSCs death, with high concentrations leading to substantial loss of viability.

2.3. SrCl2 and K2CO3 Modulate Beating Activity of iPSC-CMs Clusters Assessed by MEA

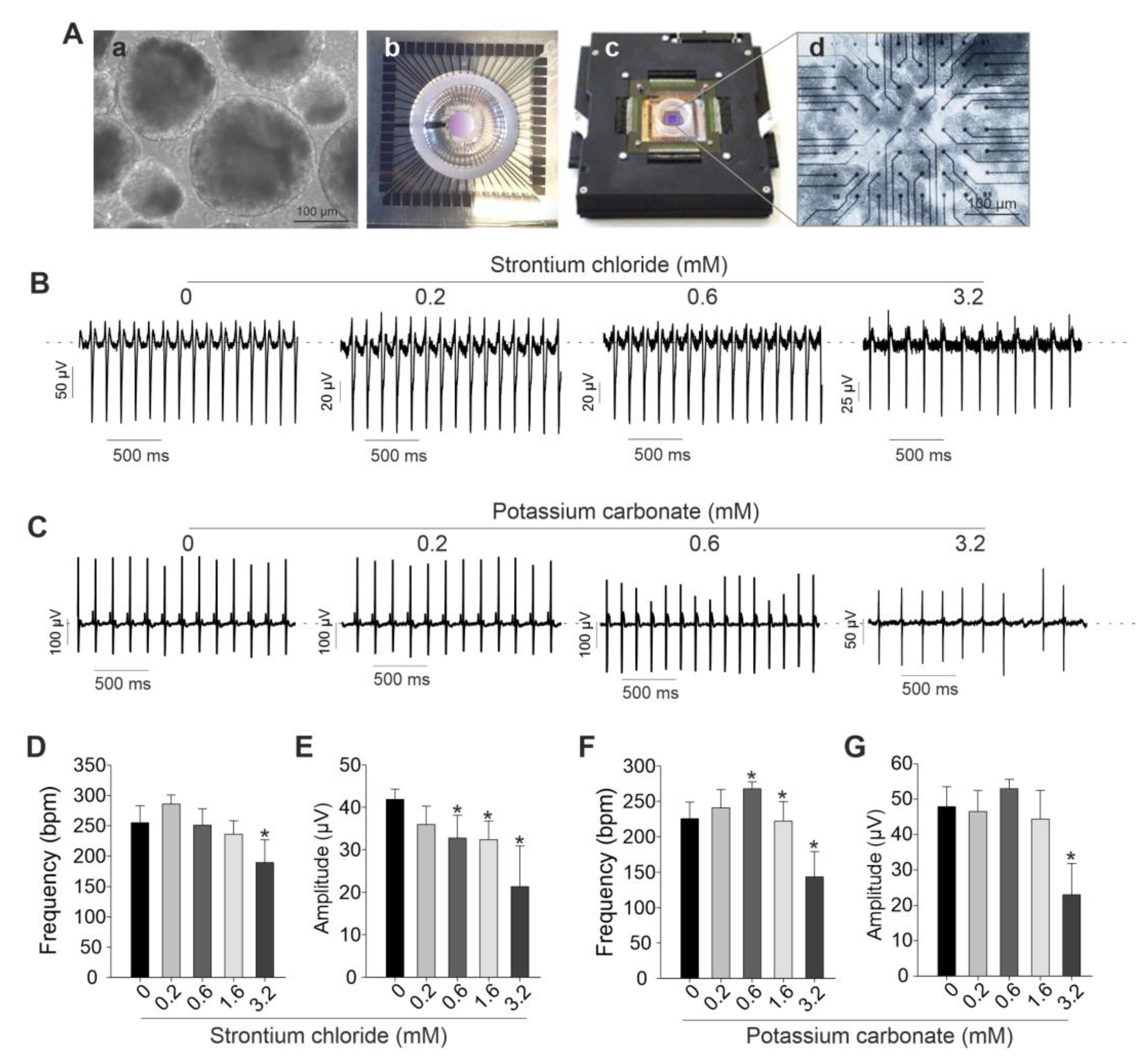

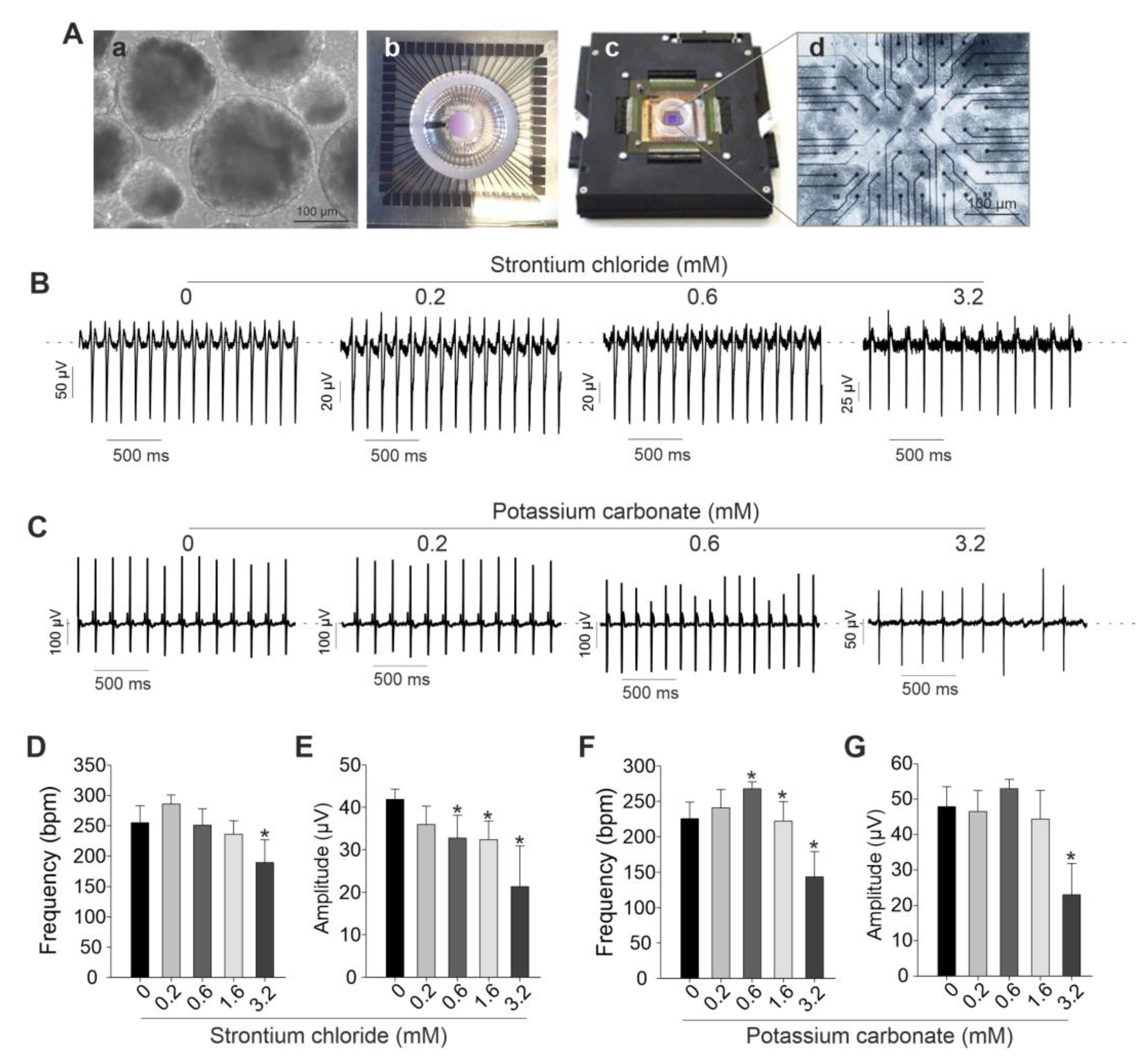

To further investigate the effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on spontaneously beating clusters of cardiomyocytes, electrophysiological recordings were conducted using the MEA system.

Figure 4A presents a representative image of day 12 embryoid bodies (EBs) plated onto an MEA chamber and recorded after attachment. As illustrated in

Figure 4B and 4C, low concentrations of both compounds had minimal impact on field potential amplitude and beating frequency (

Figure 4B-4G). Specifically, SrCl₂ at concentration range from 0.2 to 0.6 mM produced stable field potential traces without significant alterations in spike amplitude or frequency. However, at concentrations above 1.6 mM, SrCl₂ induced noticeable changes in both parameters. In contrast, K₂CO₃ caused more pronounced and dose-dependent disruptions. At 3.2 mM, spike morphology became less defined, and field potential amplitude was reduced compared to the control. These effects were supported by quantitative analysis, which showed a consistent trend toward decreased spike amplitude at 1.6 mM and 3.2 mM for both compounds, although variations in beating frequency were less consistent. Taken together, both SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ exhibited minimal functional effects on iPSC-CMs at low concentrations, while higher concentrations led to significant electrophysiological disturbances, detectable through MEA-based field potential analysis.

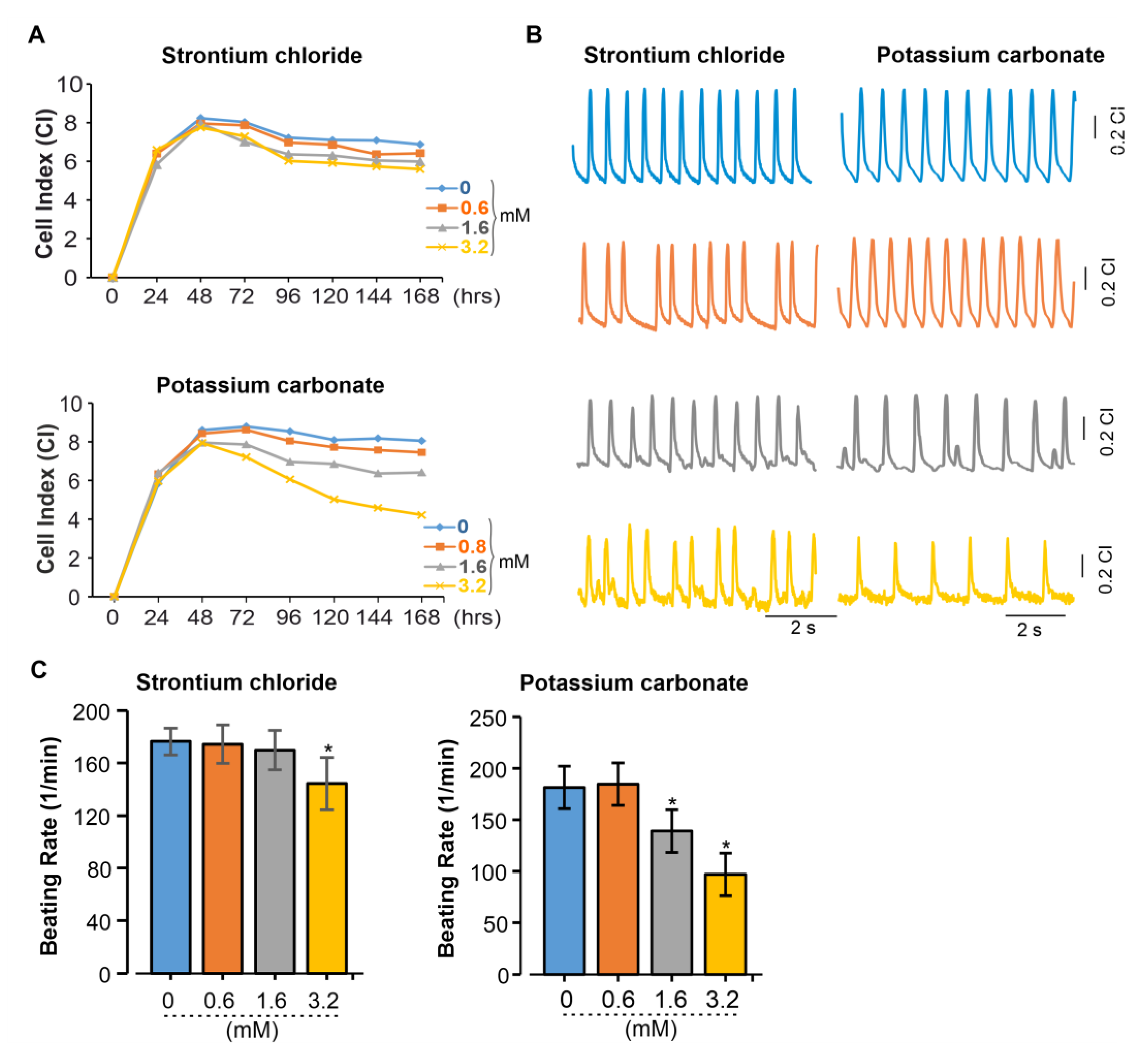

2.4. Impedance-Based Analysis Reveals SrCl2 and K2CO3 Disrupt Coordinated Beating in iPSC-CMs

To distinguish the effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on the beating patterns of 2D cardiac cell cultures, real-time impedance analysis was performed using the xCELLigence RTCA system. This platform enables continuous, label-free monitoring of cellular dynamics, capturing changes in cell adhesion, morphology, and contractile activity. By analyzing impedance signals, alterations in beating frequency and potential arrhythmic events induced by chemical exposure or genetic modifications can be effectively assessed. As revealed exposure of iPSC-CMs to SrCl

2 and K

2CO

3 induced changes in the CI and beating pattern in a concentration-dependent manner (

Figure 5A). Both compounds do not appear to impede cell attachment or monolayer formation, as indicated by the normal progression of the CI. At the high concentration of 3.2 mM, prolonged exposure led to a progressive decline in CI over 72 h for both compounds, with a more pronounced reduction observed for K

2CO

3. Lower concentrations (0.6 - 1.6 mM) had minimal effects on CI values compared to the controls. Beating profiles recorded via the RTCA system revealed that SrCl

2 preserved rhythmic contractions at 0.6 and 1.6 mM. At 3.2 mM, contractions remained regular but showed reduced amplitude and frequency (

Figure 5B, left). In contrast, K

2CO

3 at 3.2 mM induced irregular and low-amplitude beating (

Figure 5B, right), indicating impaired excitation-contraction coupling. Quantification of beating frequency confirmed these observations (

Figure 5C). SrCl2 caused a significant reduction only at 3.2 mM (p<0.05), while K

2CO

3 induced a dose-dependent decrease starting at 1.6 mM, with frequencies dropping below 100 bpm at 3.2 mM (p<0.05). These results demonstrate dose -dependent functional impairment in iPSC-CMs, with K

2CO

3 causing more severe and earlier effects than SrCl

2.

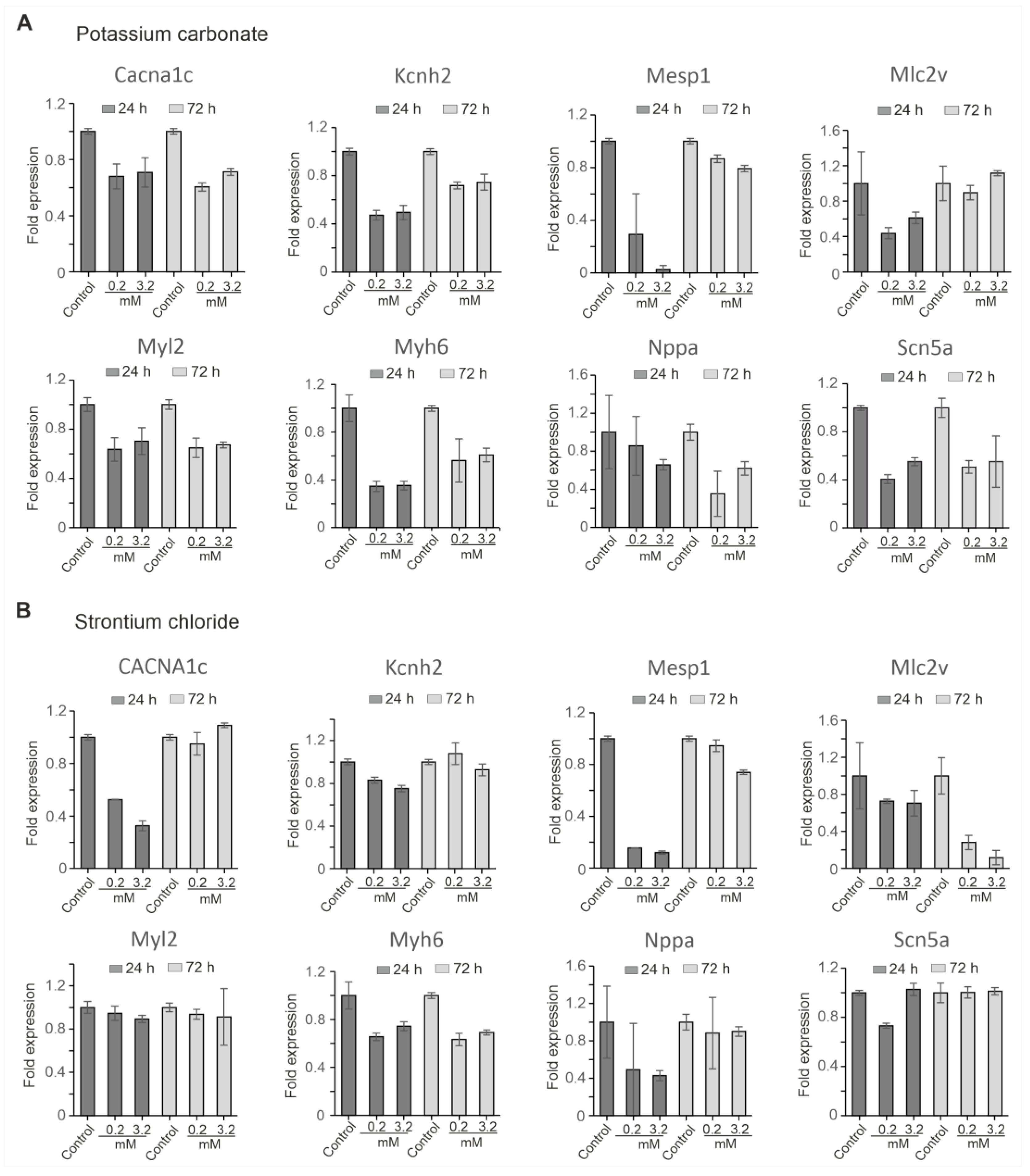

2.5. Transcriptional Impact of SrCl2 and K2CO3 on iPSC-CMs

To assess the molecular impact of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on cardiac gene expression, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed at 24 h and 72 h following exposure to each compound at concentrations of 0.2 mM and 3.2 mM. The analysis focused on a set of genes representing key aspects of cardiac development and function, including early mesodermal differentiation (Mesp1), structural sarcomeric proteins (Myl2, Myh6, Mlc2v), cardiac ion channels (Scn5a, Cacna1c, Kcnh2), and a stress marker (Nppa). Expression levels were normalized to Gapdh as an internal reference.

The result revealed that K₂CO₃ induced broad transcriptional suppression in a dose- and time-dependent manner (

Figure 6A).

Mesp1 and

Myh6 were markedly downregulated at both time points 24 h and 72 h, with the suppression being more pronounced at higher concentrations (3.2 mM) after 24 h.

Myl2 and

Kcnh2 showed persistent downregulation at all concentration tested. While

Mlc2v initially showed a decline, its expression recovered at 72 h, indicating some degree of compensation at the lower dose (0.2 mM).

Scn5a and Cacna1c were also significantly affected, with

Scn5a showing remarkable downregulation compared to

Cacna1. In addition,

Nppa, progressively declined over time, with more pronounced suppression observed at the higher concentration. In contrast, SrCl₂ elicited milder and more partially reversible changes in gene expression (

Figure 6B).

Mesp1 and

Cacna1c were transiently downregulated at 24 h in dose dependent-manner, but both recovered by 72 h, indicating a temporary effect. Similarly,

Myl2 was moderately affected at both time points.

Mlc2v and

Myh6 showed sustained downregulation at tested concentration.

Scn5a and were only slightly affected, and

Nppa expression showed partial recovery after 72 h.

Taken together, K₂CO₃ caused more robust widespread transcriptional repression of multiple categories of genes, including markers of early mesodermal differentiation, structural sarcomeric proteins, ion channels, and stress markers. This indicates that K₂CO₃ has a higher transcriptional toxicity potential than SrCl₂ in iPSC-CMs, which exhibited milder and more reversible changes in gene expression. These results suggest that K₂CO₃ may pose a greater risk to cardiac development and function than SrCl₂, emphasizing the compound-specific nature of their gene expression profiles and their potential impact on cardiac cells.

Table 1.

List of primer used for quantitative RT-PCR. Sequences are shown from 5' to 3' direction.

Table 1.

List of primer used for quantitative RT-PCR. Sequences are shown from 5' to 3' direction.

| Gene |

Forward Primer |

Reverse Primer |

| Myh6 |

AACAGGTGATGGCAAGATCC |

GCTCAAAGTCAGCACCTTC |

| Myl2 |

AAAGAGGCTCCAGGTCCAAT |

TCAGCCTTCAGTGACCCTTT |

| Nppa |

GGGGGTAGGATTGACAGGAT |

ACACACCACAAGGGCTTAGG |

| Mesp1 |

GTCTGCAGCGGGGTGTCGTG |

CGGCGGCGTCCAGGTTTCTA |

| Cacna1c |

AAGGCTACCTGGATTGGATCAC |

GCCACGTTTTCGGTGTTGAC |

| Kcnh2 |

CGTGCTGCCTGAGTACAAGCT |

TGTGAAGACAGCCGTGTAGATGA |

| Scn5a |

GAAGAAGCTGGGCTCCAAGA |

CATCGAAGGCCTGCTTGGTC |

| Mlc2v |

AAAGAGGCTCCAGGTCCAAT |

TCAGCCTTCAGTGACCCTTT |

| Gapdh |

GGTGCTGAGTATGTCGTGGA |

CGGAGATGATGACCCTTTTG |

3. Discussion

This study investigated the cytotoxic and cardiotoxic properties of two commonly used inorganic compounds SrCl2 and K2CO3 using a murine iPSC-derived in vitro model. By combining real-time impedance monitoring, electrophysiological recordings via MEA, FACS, and gene expression analysis, we assessed their impact on both undifferentiated iPSCs and differentiated iPSC-CMS. Our results demonstrate that both compounds interfere with CMs viability and function in a dose- and time-dependent manner, although through distinct and potentially complementary mechanisms.

SrCl

2 displayed a variable toxicity profile across assays. While some concentrations transiently stimulated iPSC proliferation, higher doses consistently reduced cell viability and altered contractility. These effects may be related to the chemical similarity between Sr

2+ and Ca

2+, which could allow Sr

2+ entry via Ca

2+ channels and interfere with Ca

2+-dependent signaling pathways [

14,

15]. Previous studies revealed that Sr

2+ can prolong action potentials (AP) and disrupt excitation-contraction coupling [

16,

17], consistent with the mild arrhythmogenic activity observed in our MEA and RTCA xCELLigence data. Gene expression analysis revealed transient suppression of differentiation and contractile markers, with partial recovered by 72 h, suggesting an adaptive cellular response or incomplete toxicity under the conditions tested. The variability in proliferation responses across replicates is consistent with reported cell type specific effects of SrCl

2, which can promote proliferation in some contexts while being cytotoxic in others [

18,

19].

In contrast, K

2CO

3 exhibited a robust and consistent cytotoxic profile. Exposure to increasing concentrations led in a rapid decrease in cell index, pronounced morphological disruption, and high density cell death. This is likely mediated by membrane depolarization due to excess extracellular K

+ concentration, which may inactivate Na

+ channels [

20], and consequent impairment of AP initiation [

21,

22]. This observation is consistent with our MEA findings demonstrating reduced spike amplitude and contractile silencing. Additionally, the sustained downregulation of some cardiac genes, particularly encoding ion channel and structural proteins, suggests a broader disruption of CMs identity and functional integrity.

Both compounds also affected transcriptional programs and stress signaling. Downregulation of

Mesp1,

Myh6, and

Kcnh2 observed after compound exposure suggests disruption of cardiac identity, with K

2CO

3 induced more consistent suppression. SrCl

2 may interfere with transcription via Ca

2+-mimetic signaling pathways, potential implicating NFAT or MEF2 activation [

23,

25]. Persistent suppression of

Mlc2v and transient

Nppa modulation in SrCl

2-treated cells may reflect early responses or alterations in ventricular cell and tissue specification. It should also be noted that SrCl

2 and K

2CO

3 might exert effects through mechanisms beyond electrophysiology. Since Sr

2+ has been shown to activate the Ca

2+-sensing receptor (CaSR), a G-protein coupled receptor involved in intracellular Ca

2+ release via IP

3 signaling in bone and thyroid cells [

26,

27], it remains plausible that a comparable mechanism may occur in CMs. In CMs, such dysregulation could trigger mitochondrial Ca

2+ overload and apoptosis [

28]. Similarly, excess extracellular K

+ may modulate cytokine signaling and pro-apoptotic pathways [

29], and carbonate ions of K

2CO

3 may locally alkalinize the medium, potentially introducing secondary stress [

28]. Although not directly measured here, ionic imbalances can influence inflammatory pathways [

30,

31], including TGF-β and TNF-α signaling, which are known to affect CMs survival and function [

32,

33].

In summary, SrCl2 and K2CO3 exhibit distinct, dose-dependent cardiotoxic profiles in iPSC-with Srl2 induced progressive arrhythmogenic disturbances and K2CO3 causing acute electrical silencing. These findings highlight how even simple ionic compounds can exert distinct and complex effects on excitable cells. Although further validation is needed, our observations underscore the importance of functional cardiotoxicity assessments for commonly used substances, including those considered relatively inert.

Limitations

This investigation offers initial insights into the acute effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on CMs; however, several caveats must be acknowledged. The absence of direct mechanistic investigations, such as assessments of ion channel activity, Ca2+ handling, or inflammatory signaling, restricts the mechanistic interpretation of the observed cellular responses. Moreover, the concentrations applied in vitro were not benchmarked against physiologically relevant exposure levels, and corresponding pharmacokinetic or absorption data are unavailable to support translational extrapolation. The focus on short-term exposure (≤72 h) in both MEA recording and gene expression analyses further restricts the translation of these findings to realistic consumer exposure scenarios. Consequently, the present results should be considered hypothesis generating and underscoring the need for follow up studies that incorporate long-term, physiologically based, and mechanistically oriented approaches, including in vivo experiment, to more accurately delineate the cardiotoxic potential of these compounds.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Compounds

All reagents were purchased from Carl Roth (Germany), unless otherwise stated. Dulbecco´s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany) was used to culture undifferentiated murine iPSCs, while Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) served as the base for cardiac differentiation protocols. Stock solutions of SrCl2 and K2CO3 were freshly prepared and diluted in the respective culture media to achieve final concentrations ranging from 0.07-3.2 mM for SrCl2 and 0.1- 3.2 mM for K2CO3, immediately prior to application.

4.2. Culture of Murine iPSCs

The murine αPig-AT25 iPSC line, expressing eGFP and puromycin resistance under control of the αMHC promoter, was maintained on mitotically inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), 1% non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Cells were passaged every 48 h using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA.

4.3. Cardiac Differentiation of iPSCs

Cardiomyocytes (CMs) differentiation was induced using the embryoid body (EB) method with slight modifications based on

Fatima et al. [

34]. Briefly, 1×10

6 iPSCs were cultured in suspension in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin under continuous agitation. On day 2, the resulting EBs were plated onto gelatin-coated dishes and maintained under adherent conditions for an additional 7 days. Spontaneous contraction of the EBs was observed between day 7 and 9. Puromycin (8 µg/mL) was added for 72 h to select αMHC-positive CMs, resulting in the enrichment of purified iPSC-CMs.

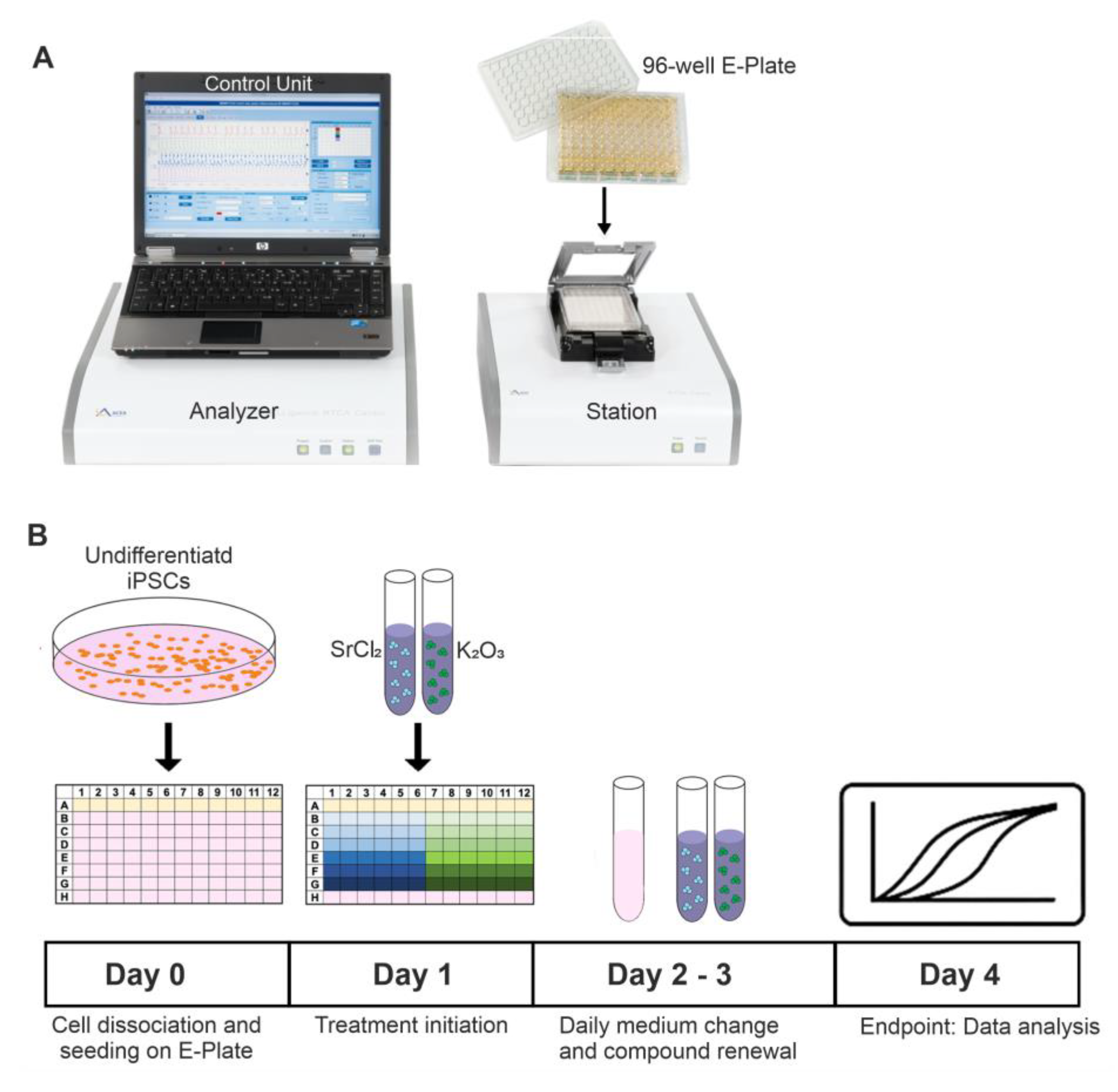

4.4. Drug Treatments

For cytotoxicity and functional evaluations, cells were seeded in appropriate densities on gelatin-coated 96-well E-Plates (xCELLigence RTCA Cardio Instrument, Agilent Technologies, formerly ACEA Biosciences,

Figure 7A) or MEA chips and allowed to adhere for 24 h. After adhesion, the cells were then treated with various concentrations of SrCl

2 or K

2CO

3. To maintain continuous exposure, the culture medium and compounds were refreshed every 24 h (

Figure 7B).

4.5. xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA)

The proliferations and cardiotoxicity of iPSCs and iPSC-CMs were assessed using the xCELLigence RTCA Cardio Instrument (

Figure 7A). Real-time changes in electrical impedance were recorded as Cell Index (CI), which reflecting cell viability, adherence, and beating behavior (in case of iPSC-CMs) [

35]. Data were collected and analyzed using RTCA Cardio Software.

4.6. Field Potential (FP) Recordings Using Microelectrode Arrays (MEA)

Extracellular FP recordings were conducted using a microelectrode array (MEA) recording system equipped with a Multichannel Systems 1060-Inv-BC amplifier and data acquisition system (Multichannel Systems, Reutlingen, Germany). Beating embryoid bodies (EBs) were cultured on MEA dishes that were pre-coated with 0.1%gelatin. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere for 1-2 days to allow proper attachment before recording. All recordings were carried out at 37°C to maintain physiological conditions. Various concentrations both SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ were applied to the MEA chambers containing the tissue cultures. After a 3 min baseline recording, different concentrations of both compounds (applied gradually) were introduced, with recordings taken for at least 3 min at each concentration. The data collected from the MEA were analyzed using cardio QT software that was developed in our laboratory with LabView. The analysis focused on the characterization of field potential (FP) frequencies and amplitude.

4.7. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

Cell viability and membrane integrity were assessed via propidium iodide (PI) staining. Following trypsinization, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). To stain death cell, PI (1 µg/mL) was added immediately prior to analysis. Fluorescence was measured using a flow cytometer, and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 7). Both iPSCs and iPSC-CMs were assessed for cell death.

4.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from iPSC-CMs using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer´s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed with High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), using 1 µg of total RNA as starting material. Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out with SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad, USA) on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The expression levels of cardiac-specific markers, including Myl2, Myh6, Mesp1, Nppa, Mlc2v, Scn5a, Cacna1c, and Kcnh2 were normalized to Gapdh. Data analysis was perform using the ΔΔCt method. All reactions were performed in technical triplicate with at least three biological replicates.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with at least three technical replicates (n ≥ 3). Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SD or as a percentage relative to the control group (set to 100%). Statistical significance was assessed using two-tailed unpaired t-tests, with p<0.05 considered significant. For clarity, data were rounded to one or two decimal places in the presentation, while original precision was maintained during statistical analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N. and S.K.; methodology, F.N.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, S.K., F.N., M.V.K.K., H.Z., A.K.W., J.T.Z. and S.P.S.; investigation, S.K., F.N., M.V.K.K., H.Z., A.K.W., J.T.Z. and S.P.S.; resources, F.N. and J.H.; data curation, F.N.; writing-original draft preparation, S.K., F.N., M.V.K.K.; writing-review and editing, S.K., M.V.K.K., J.H. and F.N.; visualization, F.N.; supervision, F.N. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. However, the raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elke Lieske and Vanessa Putz for their technical assistance. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT solely for language editing and correction. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| K₂CO₃ |

Potassium carbonate |

| SrCl₂ |

Strontium chloride |

| miPSCs |

Mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells |

| iPSC-CMs |

iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes |

| CMs |

Cardiomyocytes |

| MEA |

Multi-electrode array |

| EB |

Embryoid body |

| FACS |

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| CaSR |

Ca2+-sensing receptor |

References

- Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Hu, J.; Xue, H.; Lei, L.; Pan, X. Biomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Strategies for Oral Mucosa. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2025, 251, 114604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterbrink, P.; Zur Wiesche, E. Schulze; Meyer, F.; Fandrich, P.; Amaechi, B. T.; Enax, J. Prevention of Dental Caries: A Review on the Improvements of Toothpaste Formulations from 1900 to 2023. Dent J (Basel) 2024, 12(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacic, J.; Ruf, M.; Herzog, J.; Astasov-Frauenhoffer, M.; Sahrmann, P. Effect of Dentifrice Ingredients on Volume and Vitality of a Simulated Periodontal Multispecies Biofilm. Dent J (Basel) 2024, 12(no. 5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Y. Efficacy of a Toothpaste Containing Paeonol, Potassium Nitrate, and Strontium Chloride on Dentine Hypersensitivity: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial in Chinese Adults. Heliyon 2023, 9(no. 4), e14634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, M. M.; Sayed, O.; Lung, C. Y. K.; Rajasekar, V.; Yiu, C. K. Y. Applications of Bioactive Strontium Compounds in Dentistry. J Funct Biomater 2024, 15(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatemi, S.; Jafarian-Dehkordi, A.; Hajhashemi, V.; Asilian-Mahabadi, A.; Nasr-Esfahani, M. H. A Comparison of the Effect of Certain Inorganic Salts on Suppression Acute Skin Irritation by Human Biometric Assay: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. J Res Med Sci 2016, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, G. S. Strontium Is a Potent and Selective Inhibitor of Sensory Irritation. Dermatol Surg 1999, 25(no. 9), 689–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Ma, D.; Song, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Effects of 0.01 Mm Strontium on Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cell Osteogenic Differentiation Via the Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. J Int Med Res 2025, 53(no. 2), 3000605251315024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, C.; Zonefrati, R.; Galli, G.; Aldinucci, A.; Nuti, N.; Martelli, F. S.; Tonelli, P.; Tanini, A.; Brandi, M. L. The Effect of Strontium Chloride on Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017, 14(no. 3), 283–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginster, J. Y. Cardiac Concerns Associated with Strontium Ranelate. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014, 13(no. 9), 1209–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarts, J.; Mazur, N.; Fischer, H. R.; Adan, O. C. G.; Huinink, H. P. Elucidating the Dehydration Pathways of K(2)Co(3).1.5h(2)O. Cryst Growth Des 2024, 24(no. 6), 2493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D. H.; Jaladi, A. K.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, T. S.; Shin, W. K.; Hwang, H.; An, D. K. Catalytic Hydroboration of Aldehydes, Ketones, and Alkenes Using Potassium Carbonate: A Small Key to Big Transformation. ACS Omega 2019, 4(no. 14), 15893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiume, M. M.; Bergfeld, W. F.; Belsito, D. V.; Cohen, D. E.; Klaassen, C. D.; Rettie, A. E.; Ross, D.; Slaga, T. J.; Snyder, P. W.; Tilton, S. C.; Heldreth, B. Re-Review Summary of Sodium Sesquicarbonate, Sodium Carbonate, and Sodium Bicarbonate as Used in Cosmetics. Int J Toxicol 2025, 44(no. 3_suppl), 123S–28S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Zhao, C.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, L.; Kong, Y.; Zeng, F.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, J. A Network Pharmacology and Multi-Omics Combination Approach to Reveal the Effect of Strontium on Ca(2+) Metabolism in Bovine Rumen Epithelial Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(no. 11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, K.; Grauffel, C.; Dudev, T.; Lim, C. Protein Ca(2+)-Sites Prone to Sr(2+) Substitution: Implications for Strontium Therapy. J Phys Chem B 2023, 127(no. 25), 5588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M. D.; Vassalle, M. Electrical and Mechanical Effects of Strontium in Sheep Cardiac Purkinje Fibres. Cardiovasc Res 1989, 23(no. 10), 867–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronaldson, S. M.; Stephenson, D. G.; Head, S. I. Calcium and Strontium Contractile Activation Properties of Single Skinned Skeletal Muscle Fibres from Elderly Women 66-90 Years of Age. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 2022, 43(no. 4), 173–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizelli-Silveira, C.; Abildtrup, L. A.; Spin-Neto, R.; Foss, M.; Soballe, K.; Kraft, D. C. E. Strontium Enhances Proliferation and Osteogenic Behavior of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells of Mesenchymal and Ectomesenchymal Origins in Vitro. Clin Exp Dent Res 2019, 5(no. 5), 541–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Z.; Wu, C. G.; Xie, H. Q.; Li, Z. Y.; Silini, A.; Parolini, O.; Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Huang, Y. C. Strontium Promotes the Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Placental Decidual Basalis- and Bone Marrow-Derived Mscs in a Dose-Dependent Manner. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 4242178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boal, A. M.; McGrady, N. R.; Risner, M. L.; Calkins, D. J. Sensitivity to Extracellular Potassium Underlies Type-Intrinsic Differences in Retinal Ganglion Cell Excitability. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 16, 966425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangold, K. E.; Brumback, B. D.; Angsutararux, P.; Voelker, T. L.; Zhu, W.; Kang, P. W.; Moreno, J. D.; Silva, J. R. Mechanisms and Models of Cardiac Sodium Channel Inactivation. Channels (Austin) 2017, 11(no. 6), 517–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, S. M.; Yasin, S.; Jain, N.; LeLorier, P. Cardiac Manifestations in a Case of Severe Hyperkalemia. Cureus 2021, 13(no. 3), e13641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, L.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, J. The Mechanism of the Nfat Transcription Factor Family Involved in Oxidative Stress Response. J Cardiol 2024, 83(no. 1), 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devilee, L. A. C.; Salama, A. B. M.; Miller, J. M.; Reid, J. D.; Ou, Q.; Baraka, N. M.; Abou Farraj, K.; Jamal, M.; Nong, Y.; Rosengart, T. K.; Andres, D.; Satin, J.; Mohamed, T. M. A.; Hudson, J. E.; Abouleisa, R. R. E. Pharmacological or Genetic Inhibition of Ltcc Promotes Cardiomyocyte Proliferation through Inhibition of Calcineurin Activity. NPJ Regen Med 2025, 10(no. 1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewenter, M.; von der Lieth, A.; Katus, H. A.; Backs, J. Calcium Signaling and Transcriptional Regulation in Cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 2017, 121(no. 8), 1000–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, D.; Yazdi, A. Rahimnejad; Papini, M.; Towler, M. A Review of the Latest Insights into the Mechanism of Action of Strontium in Bone. Bone Rep 2020, 12, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmedzhieva, D.; Ilieva, S.; Permyakov, E. A.; Permyakov, S. E.; Dudev, T. Ca(2+)/Sr(2+) Selectivity in Calcium-Sensing Receptor (Casr): Implications for Strontium's Anti-Osteoporosis Effect. Biomolecules 2021, 11(no. 11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naima, J.; Ohta, Y. Potassium Ions Decrease Mitochondrial Matrix Ph: Implications for Atp Production and Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25(no. 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thylur Puttalingaiah, R.; Dean, M. J.; Zheng, L.; Philbrook, P.; Wyczechowska, D.; Kayes, T.; Del Valle, L.; Danos, D.; Sanchez-Pino, M. D. Excess Potassium Promotes Autophagy to Maintain the Immunosuppressive Capacity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Independent of Arginase 1. Cells 2024, 13(no. 20). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, S. M.; Naga Prasad, S. V. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha in Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Curr Cardiol Rep 2018, 20(no. 11), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, J.; Zhou, L.; Tian, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Wang, D. W.; Wei, J. Deep Insight into Cytokine Storm: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10(no. 1), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, A.; Frangogiannis, N. G. Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines as Therapeutic Targets in Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2020, 34(no. 6), 849–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, K.; Jiang, H.; Zou, Y.; Song, C.; Cao, K.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, D.; Zhang, N.; Liu, B.; Sun, G.; Tang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Programmed Death of Cardiomyocytes in Cardiovascular Disease and New Therapeutic Approaches. Pharmacol Res 2024, 206, 107281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, A.; Xu, G. X.; Nguemo, F.; Kuzmenkin, A.; Burkert, K.; Hescheler, J.; Saric, T. Murine Transgenic Ips Cell Line for Monitoring and Selection of Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Research 2016, 17(no. 2), 266–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguemo, F.; Saric, T.; Pfannkuche, K.; Watzele, M.; Reppel, M.; Hescheler, J. In Vitro Model for Assessing Arrhythmogenic Properties of Drugs Based on High-Resolution Impedance Measurements. Cell Physiol Biochem 2012, 29(no. 5-6), 819–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Differentiating murine induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into cardiomyocytes (CMs). (A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocol. (B) Representative microscopic images showing cell colonies and embryo bodies (EB) at different stages of differentiation. (C, D) Bar graphs illustrating the statistical analysis of EB diameters under Strontium Chloride (B) and Potassium Carbonate (C) treatments compared to control conditions, based on triplicate experiments. Each bar represents the mean EB diameter, with error bars indicating each condition's standard deviation (SD). The graphs compare EB size across various differentiation stages, highlighting the impact of SC treatment on EB growth and development. E) Staining of cardiac α-actinin (green) on non-dissociated clusters of beating day 14 EBs differentiated in the absence or presence of the indicated compound. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. *p<0.05 vs. control, #p<0.05 vs. previous concentration.

Figure 1.

Differentiating murine induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into cardiomyocytes (CMs). (A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocol. (B) Representative microscopic images showing cell colonies and embryo bodies (EB) at different stages of differentiation. (C, D) Bar graphs illustrating the statistical analysis of EB diameters under Strontium Chloride (B) and Potassium Carbonate (C) treatments compared to control conditions, based on triplicate experiments. Each bar represents the mean EB diameter, with error bars indicating each condition's standard deviation (SD). The graphs compare EB size across various differentiation stages, highlighting the impact of SC treatment on EB growth and development. E) Staining of cardiac α-actinin (green) on non-dissociated clusters of beating day 14 EBs differentiated in the absence or presence of the indicated compound. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. *p<0.05 vs. control, #p<0.05 vs. previous concentration.

Figure 2.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of SrCl2 and K2CO3 on iPSC proliferation measured via xCELLigence real-time cell analysis. (A) SrCl2 exposure induced a variable response in murine iSPCs. Lower concentrations (≤ 0.68 mM) showed a moderate increase in cell index (CI) over time, whereas higher concentrations (1.58 – 3.15 mM) caused a delayed suppression of CI, particularly after 48 – 72h (p<0.05). (B) K2CO3 exposure led to a more pronounced and concentration-dependent inhibition of proliferation. CI declined significantly at ≥ 1.6 mM starting at 24 h (p<0.05). Right bar graphs show mean CI values ± SD at 3.15 mM vs. control over time (n=3). Small insets (top right) illustrate inter-experimental variability for 3.15 mM vs. control, shown as CI range with error bars. These highlight that the observed effects, especially for SrCl2, were subject to biological variation across independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of SrCl2 and K2CO3 on iPSC proliferation measured via xCELLigence real-time cell analysis. (A) SrCl2 exposure induced a variable response in murine iSPCs. Lower concentrations (≤ 0.68 mM) showed a moderate increase in cell index (CI) over time, whereas higher concentrations (1.58 – 3.15 mM) caused a delayed suppression of CI, particularly after 48 – 72h (p<0.05). (B) K2CO3 exposure led to a more pronounced and concentration-dependent inhibition of proliferation. CI declined significantly at ≥ 1.6 mM starting at 24 h (p<0.05). Right bar graphs show mean CI values ± SD at 3.15 mM vs. control over time (n=3). Small insets (top right) illustrate inter-experimental variability for 3.15 mM vs. control, shown as CI range with error bars. These highlight that the observed effects, especially for SrCl2, were subject to biological variation across independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Assessment of Cell Viability and Structural Integrity in iPSC-CMs Following SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ Exposure. (A) Diagram of the experimental protocol for flow cytometry analysis illustrating the EBs dissociation, cell seeding, and treatment timeline. (B-C) Representative flow cytometry plots showing PI-positive cells within the population treated with varying concentration of SrCl2 (A) and K2CO3 (B). The plot demonstrates a significant rightward shift in the treated cells, both in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, compared to untreated cells, indicating cell damage. (PI, propidium iodide.

Figure 3.

Assessment of Cell Viability and Structural Integrity in iPSC-CMs Following SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ Exposure. (A) Diagram of the experimental protocol for flow cytometry analysis illustrating the EBs dissociation, cell seeding, and treatment timeline. (B-C) Representative flow cytometry plots showing PI-positive cells within the population treated with varying concentration of SrCl2 (A) and K2CO3 (B). The plot demonstrates a significant rightward shift in the treated cells, both in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, compared to untreated cells, indicating cell damage. (PI, propidium iodide.

Figure 4.

Functional effects of SrCl2 and K2CO3 on iPSC-CMs beating clusters were assessed by MEA. (A) The setup and cell model used for MEA analysis. (a) Brightfield image of EBs at day 12 post-differentiation; (b-d) MEA chip and amplifier system used for field potential recordings of iPSC-CMs seeded on MEA electrodes. (B, C) Representative FP traces of iPSC-CMs treated with increasing concentrations of SrCl2 (B) or K2CO3 (C). Traces demonstrate effects on frequency and FP amplitude across 0 – 3.2 mM concentrations. (D, E) Quantification of beating frequency (D) and FP amplitude (E) in SrCl2-treated iPSC-CMs. While beating frequency was not significantly altered at lower doses, a significant reduction was observed at 3.2 mM. Field potential (FP) amplitude decreased significantly at concentrations ≥ 0.2 mM. (F, G) Quantifying beating frequency (F) and FP amplitude (G) in K2CO3-treated iPSC-CMs. Low doses (0.2 - 0.6 mM) increased frequency significantly, while 3.2 mM caused a strong decrease. FP amplitude was significantly reduced at 3.2 mM. All values are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3-4), p<0.05 vs. control (0 mM)..

Figure 4.

Functional effects of SrCl2 and K2CO3 on iPSC-CMs beating clusters were assessed by MEA. (A) The setup and cell model used for MEA analysis. (a) Brightfield image of EBs at day 12 post-differentiation; (b-d) MEA chip and amplifier system used for field potential recordings of iPSC-CMs seeded on MEA electrodes. (B, C) Representative FP traces of iPSC-CMs treated with increasing concentrations of SrCl2 (B) or K2CO3 (C). Traces demonstrate effects on frequency and FP amplitude across 0 – 3.2 mM concentrations. (D, E) Quantification of beating frequency (D) and FP amplitude (E) in SrCl2-treated iPSC-CMs. While beating frequency was not significantly altered at lower doses, a significant reduction was observed at 3.2 mM. Field potential (FP) amplitude decreased significantly at concentrations ≥ 0.2 mM. (F, G) Quantifying beating frequency (F) and FP amplitude (G) in K2CO3-treated iPSC-CMs. Low doses (0.2 - 0.6 mM) increased frequency significantly, while 3.2 mM caused a strong decrease. FP amplitude was significantly reduced at 3.2 mM. All values are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3-4), p<0.05 vs. control (0 mM)..

Figure 5.

Functional effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on iPSC-CM were assessed using xCELLigence RTCA Cardio System. (A) Representative graph from one of three independent experiments showing the effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on miPSC-CMs. The CI was monitored in real time for about 196 h after the addition of 0 mM (control) or various concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. (B) Representative beating rate pattern from 20 ms recordings of iPSC-CMs exposed to different concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. (C) Average change in beating rate of iPSC-CMs under different concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). *p<0.05 vs. control (0 mM).

Figure 5.

Functional effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on iPSC-CM were assessed using xCELLigence RTCA Cardio System. (A) Representative graph from one of three independent experiments showing the effects of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃ on miPSC-CMs. The CI was monitored in real time for about 196 h after the addition of 0 mM (control) or various concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. (B) Representative beating rate pattern from 20 ms recordings of iPSC-CMs exposed to different concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. (C) Average change in beating rate of iPSC-CMs under different concentrations of SrCl₂ and K₂CO₃. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). *p<0.05 vs. control (0 mM).

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR analysis of cardiac gene expression in iPSC-CMs treated with SrCl2 and K2CO3. (A) Gene expression levels after treatment with 0.2 mM and 3.2 mM K2CO3 at 24 h and 72 h relative to the untreated control. Expression of cardiac progenitor marker (Mesp1), structural genes (Myl2, Myh6, Mlc2v), ion channel genes (Scn5a, Cacna1c, Kcnh2), and stress marker (Nppa) was assessed. K2CO3 exposure caused widespread and persistent downregulation across several markers, particularly Mesp1, Myl2, Myh6, and Kcnh2. (B) Gene expression levels following SrCl2 exposure under identical conditions. SrCl2 treatment induced more transient changes, with several markers (Mesp1, Cacna1c, Kcnh2) showing partial or full recovery by 72 h. Data represent mean ± SEM from independent experiments. Expression was normalized to Gapdh and calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR analysis of cardiac gene expression in iPSC-CMs treated with SrCl2 and K2CO3. (A) Gene expression levels after treatment with 0.2 mM and 3.2 mM K2CO3 at 24 h and 72 h relative to the untreated control. Expression of cardiac progenitor marker (Mesp1), structural genes (Myl2, Myh6, Mlc2v), ion channel genes (Scn5a, Cacna1c, Kcnh2), and stress marker (Nppa) was assessed. K2CO3 exposure caused widespread and persistent downregulation across several markers, particularly Mesp1, Myl2, Myh6, and Kcnh2. (B) Gene expression levels following SrCl2 exposure under identical conditions. SrCl2 treatment induced more transient changes, with several markers (Mesp1, Cacna1c, Kcnh2) showing partial or full recovery by 72 h. Data represent mean ± SEM from independent experiments. Expression was normalized to Gapdh and calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Figure 7.

Schematic overview of the experimental setup for xCELLigence-based proliferation monitoring of murine iPSCs. (A) The xCELLigence RTCA Cardio Instrument, used for continuous impedance-based analysis of cell proliferation and viability, is used for continuous impedance-based cell proliferation and viability analysis. The system includes an analyzer and control unit, connected to specialized 96-well E-Plates containing interdigitated gold electrodes. (B) Timeline summarizing the experimental procedure: after seeding (Day 0), treatment was initiated on Day 1, and cells were exposed to repeated compound application for up to 72 h. Treatments with SrCl2 and K2CO3 were applied at various concentrations. Final analysis was performed on Day4.

Figure 7.

Schematic overview of the experimental setup for xCELLigence-based proliferation monitoring of murine iPSCs. (A) The xCELLigence RTCA Cardio Instrument, used for continuous impedance-based analysis of cell proliferation and viability, is used for continuous impedance-based cell proliferation and viability analysis. The system includes an analyzer and control unit, connected to specialized 96-well E-Plates containing interdigitated gold electrodes. (B) Timeline summarizing the experimental procedure: after seeding (Day 0), treatment was initiated on Day 1, and cells were exposed to repeated compound application for up to 72 h. Treatments with SrCl2 and K2CO3 were applied at various concentrations. Final analysis was performed on Day4.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).