1. Introduction

Electrical burn injuries, particularly those caused by high-voltage current, are characterised by extensive deep tissue destruction despite relatively limited cutaneous involvement. Electrocution, although a fairly common mechanism of burn injury in the developing countries, occurring in domestic environments, high voltage electrical injuries at occupational settings are uncommon. [

1] Tissue injury results from thermal energy generated by tissue resistance (Ohm’s law), electroporation-induced cellular membrane disruption, and protein denaturation. [

2,

3] Distal lower limb involvement presents a distinct reconstructive challenge due to limited soft tissue reserves and the frequent exposure of tendons and joints. Lower limb injuries are also at risk of complications related to prolonged immobilisation, including deep vein thrombosis, joint stiffness, muscle atrophy, and difficulties with ambulation and self-care, all of which adversely affect functional recovery.

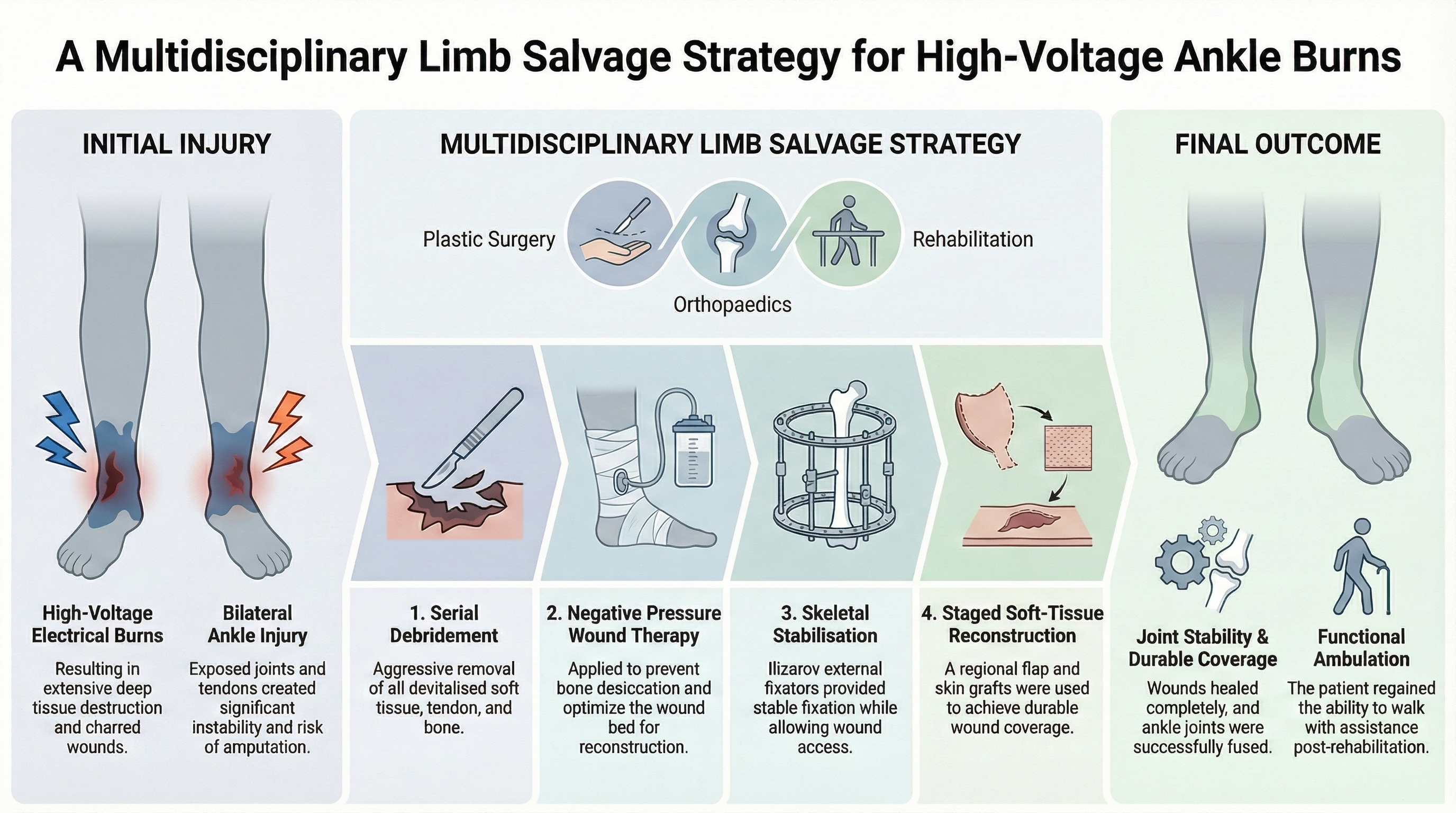

Bilateral ankle electrical burns with articular exposure are rare. We report here a case highlighting the importance of coordinated orthopaedic stabilisation and staged soft-tissue reconstruction in achieving early and adequate limb salvage.

2. Case Description

A 60-year-old male individual with no known comorbidities sustained bilateral ankle injuries after tripping over an energised high-voltage overhead transmission line while working on agricultural land. He experienced a mechanical fall with transient retrograde amnesia related to the incident. After receiving initial treatment at a peripheral facility, he was referred to our tertiary-care burn centre.

2.1. Initial Evaluation

On presentation, the patient was haemodynamically stable. Electrocardiography revealed no acute cardiac abnormalities. Local examination of the ankle injuries showed deep lacerations with charred, desiccated margins on both sides.

2.1.1. Left Ankle

Posterior wound involving approximately 50% of the ankle circumference, with complete discontinuity of the Achilles tendon, exposed talocalcaneal joint devoid of viable cartilage, and complete loss of structures within the tarsal tunnel, including the posterior tibial artery. Anterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses were palpable, with preserved distal perfusion. (

Figure 1).

2.1.2. Right Ankle

Anterior wound involving more than one-third of the ankle circumference, extending to bone, with exposed tibiotalar joint and disruption of the anterior tibial artery. Posterior tibial artery pulsation and distal toe perfusion were preserved (

Figure 2).

Plain radiographs confirmed the absence of fractures.

2.2. In-Hospital Course

Continuous cardiac monitoring and strict urine output monitoring were instituted according to standard guidelines.[

4] Initial creatine kinase-MB levels were elevated; serum electrolytes were within normal limits and urine myoglobin testing was negative. Fluid resuscitation was administered according to Parkland’s formula and titrated to maintain urine output at 1 mL/kg/hr.[

5] Biochemical parameters normalised with supportive care.

Serial surgical debridement was performed, removing all devitalised soft tissue, tendon, and necrotic bone, resulting in unstable ankles with exposed tibiotalar and talocalcaneal joints (

Figure 2). Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) was initiated to prevent bone desiccation and optimise wound beds for reconstruction.

Orthopedic consultation were taken for stabilization of the ankle. The patient was posted under general anesthesia and hybrid ankle-spanning Ilizarov external fixators were applied following thorough debridement (

Figure 3).

Meanwhile NPWT was continued postoperatively and foam dressing was changed at weekly intervals to further optimize the wound for reconstruction.

The right anterior ankle wound developed healthy granulation tissue and was covered with split-thickness skin graft obtained from the patient’s thigh. The left posterior ankle defect (13x7 cm) was however deep and was found to have exposed joint structures. It was resurfaced using a reverse sural artery flap over the Achilles region, with split-thickness skin grafts used to cover the surrounding as well as secondary donor area (

Figure 4).

The postoperative course was complicated by a superficial graft-site infection (Clavien–Dindo grade II) on the left side, managed successfully with local wound care and systemic antibiotics. The flap over left ankle healed completely, and pedicle division was performed after a session of delay on postoperative days 19 and 21 (

Figure 5).

2.3. Rehabilitation and Follow-Up

Early in-bed mobilization under guidance of rehabilitation therapy team focused on maintaining hip and knee range of motion. Active toe movements were encouraged through-out the post operative period. Limb elevation and pressure injury prevention protocols were strictly followed. Nutritional optimisation was done to allow faster recovery

The external fixators were removed at three months postoperatively, followed by immobilisation in a below-knee cast for four weeks until radiological evidence of ankle fusion was confirmed (

Figure 6).

Social counsellors frequently counselled the patient in the rehabilitation period to encourage early movement and return to work. Gradual protected weight bearing was initiated thereafter. At the latest follow-up, the patient remains ambulatory with the assistance of a walker.

3. Discussion

High-voltage electrical injuries are associated with progressive deep tissue necroses that frequently extend beyond the clinically visible zone of injury. Bilateral deep ankle electrical injuries with articular exposure are uncommon and can pose distinct reconstructive challenges due to the region’s limited soft-tissue envelope and precarious vascularity. The ankle region is structurally vulnerable because of its limited soft-tissue envelope, relatively poor regional vascularity, and the superficial course of critical tendinous and neurovascular structures. These anatomical constraints reduce the margin for conservative management and make functional reconstruction substantially more challenging than in more proximal lower limb injuries. Existing literature predominantly describes unilateral injuries or involvement of the upper limb, limiting the availability of evidence-based guidance for bilateral ankle injuries.[

6]

Early aggressive debridement, NPWT, stable skeletal fixation with Ilizarov frames, and timely soft-tissue reconstruction were critical in achieving durable limb salvage in this patient. The decision for wound management was based on the reconstructive grid, which highlights the use of appropriate care methods based on the wound complexity.[

7] The mechanism of injury likely involved sequential contact of both feet with a fallen high-voltage conductor, producing a localised electrocautery-like vascular and soft-tissue injury without extensive distant systemic damage.

Skeletal instability in the presence of exposed joints represents both a mechanical and biological barrier to wound healing. The application of hybrid Ilizarov external fixators addressed this limitation by providing stable multiplanar fixation while avoiding the placement of internal hardware within a contaminated and poorly vascularised zone. Circular and hybrid constructs as in this case facilitates repeated wound access, staged reconstruction, offloading while allowing definitive arthrodesis.[

8] These characteristics make external fixation particularly suited to the management of complex limb electrical injuries, where infection risk, soft-tissue compromise and length of healing time are predictably high.

Soft-tissue reconstruction following electrical burns is complicated by progressive vascular injury, intimal damage, and the risk of delayed thrombosis, which undermine flap reliability. In this context, the reverse sural artery flap remains a dependable regional reconstructive option for posterior ankle and heel defects. Its vascular supply is relatively consistent and in this scenario was located outside the primary zone of electrical injury. In this patient, the flap achieved durable coverage of the exposed Achilles region and joint structures, while split-thickness skin grafting provided satisfactory resurfacing of the adjacent defects. The outcome supports the role of regional flaps as a practical and reliable alternative when free tissue transfer may be limited by vascular uncertainty.

From a systems perspective, this case demonstrates the value of integrated multidisciplinary management. Early coordination between burn surgery, orthopaedics, and reconstructive surgery enabled synchronised decision-making, minimised time between debridement, stabilisation, and coverage, and reduced the likelihood of secondary complications. Existing evidence supports that such coordinated care pathways are associated with reduced amputation rates and improved functional outcomes in complex limb injuries.

In addition to its clinical implications, this case highlights broader public health considerations. High-voltage electrical injuries in rural environments reflect systemic vulnerabilities in infrastructure maintenance and occupational safety. Strengthening transmission line inspection protocols, enforcing electrical safety regulations, and improving community-level awareness represent evidence-based preventive strategies that are likely to have a meaningful impact on injury incidence.

4. Conclusions

Bilateral ankle electrical burns with exposed joints represent a rare and complex reconstructive challenge. Early orthopaedic stabilisation combined with staged soft-tissue reconstruction can achieve functional limb salvage in selected patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.M. and S.V.S.; methodology, B.P.R. and D.P.M.; investigation, S.V.S., B.P.R. and S.R.; data curation, S.R., S.V.S. and B.P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P.M., S.V.S. and K.P.; writing—review and editing, D.P.M., S.V.S. and K.P.; supervision, D.P.M.; project administration, D.P.M.; resources, D.P.M.; validation, D.P.M., S.V.S. and K.P. All authors were directly involved in patient care. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript the author(s) used ChatGPT, version 5.2 for the purpose of refining the manuscript language. The help of Generative AI (Notebook LM) was taken to develop the prompt and image for the graphical abstract from the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kalra GS, Sharma A, Rolekar NG. Changing trends in electrical burn injury due to technology. Indian J Burns. 2019;27(1):70–72.

- Bhatt DL, Gaylor DC, Lee RC. Rhabdomyolysis due to pulsed electric fields. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86(1):1–7.

- Arnoldo BD, Hunt JL, Sterling JP, et al. Electrical injuries. In: Herndon DN, ed. Total Burn Care. Edinburgh: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:433–439.

- Arnoldo BD, Klein M, Gibran NS. Practice guidelines for the management of electrical injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:439–447.

- Baxter CR, Shires T. Physiological response to crystalloid resuscitation of severe burns. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150:874–894.

- Karmakar S, Rai RK, Yadav GD, Singh PK, Kumar V. High-voltage electric burns: experience from a single centre in North India. Clin J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;1(2):37–44.

- Mohapatra, D. P., & Thiruvoth, F. M. (2021). Reconstruction 2.0: Restructuring the Reconstructive Ladder. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 147(3), 572e–573e.

- Othman MS, Leong JF, Ong KC, Wan KL, Ahmad Shah SA. Technique and outcome of ankle fractures treated with Ilizarov external fixator: a case series. J Med Case Rep Case Series. 2021;2(16).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).