III. Methodologies for Water Pricing Analyses

Water pricing constitutes a fundamental element of integrated resource management, as it directly affects consumption behavior, allocation efficiency, and long-term sustainability. This study employs a multi-dimensional analytical framework, incorporating a dynamic pricing model, to evaluate water pricing strategies in Taiwan. The methodological design integrates economic theory, hydrological modeling, and institutional analysis, thereby capturing both quantitative and qualitative dimensions of water use. Three principal approaches are applied:

Cost-Based Analysis: Estimation of water tariffs based on infrastructure operation, maintenance, and environmental externalities.

Demand-Side Assessment: Evaluation of demand elasticity across domestic, agricultural, and industrial sectors, with particular attention to seasonal variability.

Integrated Policy Review: Examination of regulatory frameworks and institutional arrangements to identify gaps and opportunities for adaptive pricing mechanisms.

This framework enables a comprehensive assessment of water pricing that accounts for hydrological variability, socio-economic demands, and governance structures. By integrating technical and policy perspectives, the analysis provides a foundation for designing equitable and sustainable pricing strategies.

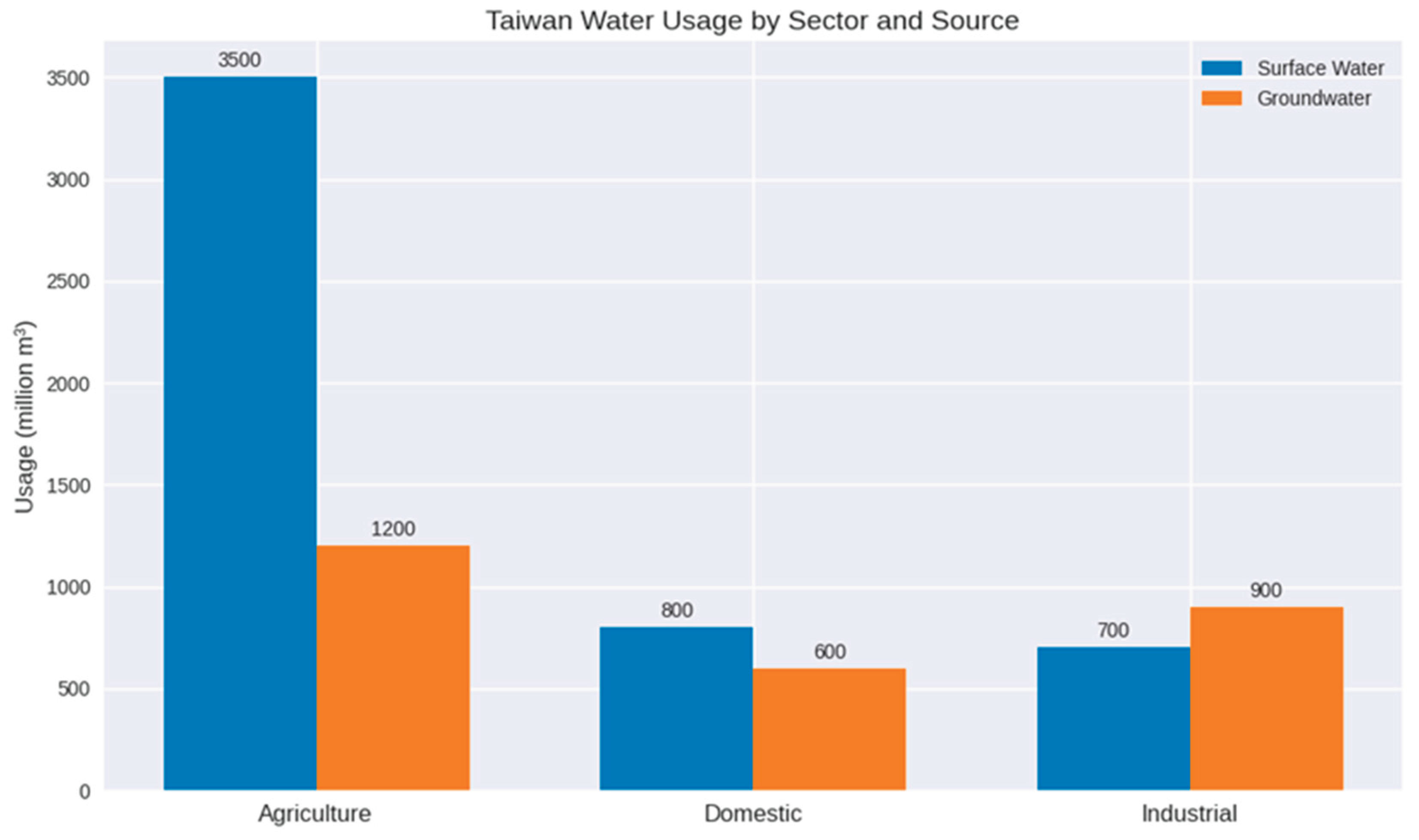

In Taiwan, agricultural water use represents approximately 70% of total consumption, primarily for irrigation and aquaculture. This sector is highly seasonal and vulnerable to droughts, making it a focal point for water-saving technologies and policy reforms. Domestic water use accounts for about 20%, encompassing household consumption, municipal services, and sanitation. Rapid urbanization has intensified demand in metropolitan areas such as Taipei and Taichung, where water quality and supply reliability are major concerns, prompting investments in purification and distribution systems. Industrial water use comprises roughly 10%, supporting manufacturing, cooling, and cleaning processes. Taiwan’s high-tech industries, particularly semiconductor fabrication, are significant consumers, and government initiatives have promoted recycling and reuse within industrial parks to mitigate environmental impacts.

As climate change intensifies extreme weather events, effective water resource management has become increasingly critical. Key policy instruments include:

Water Rights Exchange Mechanism: Encouraging efficient allocation through market-based transfers.

Infrastructure Development Programs: Investing in water storage, distribution, and conservation systems.

Industrial Water Reuse Initiatives: Promoting recycling and efficiency in manufacturing sectors.

This integrated approach underscores the need for adaptive strategies that balance sectoral demands while enhancing resilience to climate variability.

Water resource management in Taiwan has been extensively examined in relation to climate variability, urbanization, and economic development. Previous studies emphasize the critical role of integrated planning in mitigating seasonal shortages and highlight the importance of inter-agency coordination. Analyses of Taiwan’s water rights exchange mechanism demonstrate its potential to optimize allocation during drought conditions, thereby improving efficiency and equity in resource distribution. Comparative research has assessed Taiwan’s water usage relative to other East Asian nations, revealing that agricultural consumption in Taiwan is proportionally higher than in Japan and South Korea, where industrial and domestic sectors dominate. These findings underscore the necessity for Taiwan to diversify its water usage portfolio and strengthen resilience through policy innovation. Recent government reports provide detailed sectoral data and infrastructure development records, offering valuable references for both academic inquiry and policy formulation.

Given the variability of hydrological events in Taiwan, systematic data collection on both surface water and groundwater is essential for accurate calculation and analysis. Sectoral water usage statistics were obtained from the Water Resources Agency’s reservoir and hydrology annual reports, as well as government publications. These datasets were applied to statistical methods and dynamic pricing models to evaluate seasonal and regional variations in water prices.

The diffusion of smart water metering infrastructure has enabled utilities to monitor household consumption in near real-time. This technology not only informs users about their consumption and associated costs but also facilitates dynamic pricing schemes that adjust volumetric rates according to scarcity. Such mechanisms can improve economic efficiency, influence consumer behavior, and manage demand more effectively. Dynamic pricing, in this context, refers to flexible tariff structures that incorporate risk-adjusted user costs (RAUC) and rely on smart metering to provide timely feedback to both utilities and consumers[

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

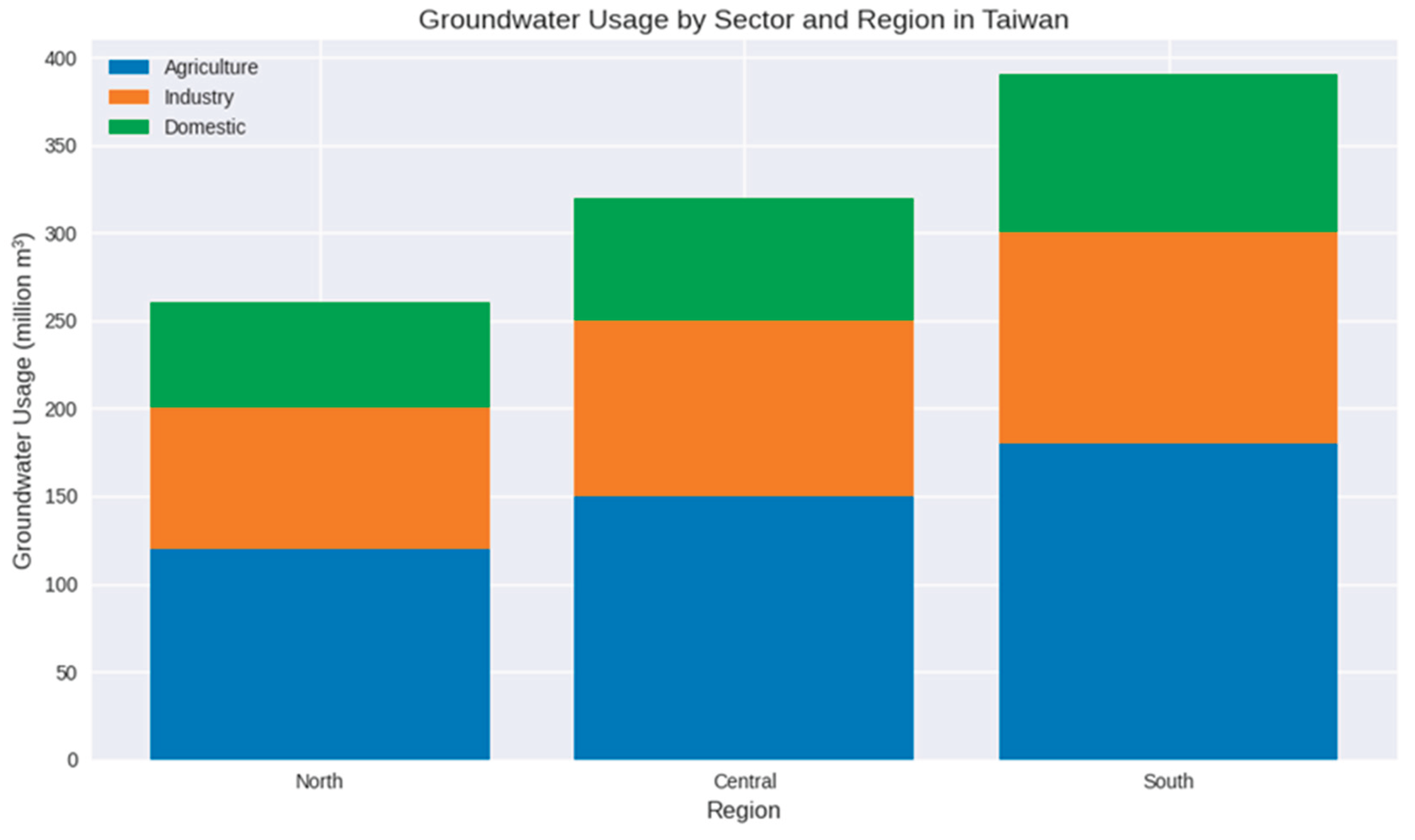

Current sectoral water consumption in Taiwan is distributed as follows: agriculture 60%, industry 15%, and domestic use 25%. These figures indicate that existing dynamic pricing models have not fully accounted for sector-specific factors, particularly given government policies aimed at stabilizing domestic water prices (

Figure 9,

Figure 10). Global studies demonstrate that dynamic pricing can effectively manage demand and promote conservation. Many emphasize tiered pricing and real-time monitoring to reflect actual water stress. However, few frameworks have integrated both seasonal and regional dimensions into a unified pricing system. Addressing this gap requires comprehensive data collection and analysis to capture the characteristics of seasonal and regional water pricing. Key influencing factors are summarized below, providing a foundation for adaptive and context-specific pricing strategies.

A. The following factors are critical in shaping seasonal and regional variations in water pricing in Taiwan (Table 3):

B. Regional Differences in Surface Water Pricing:

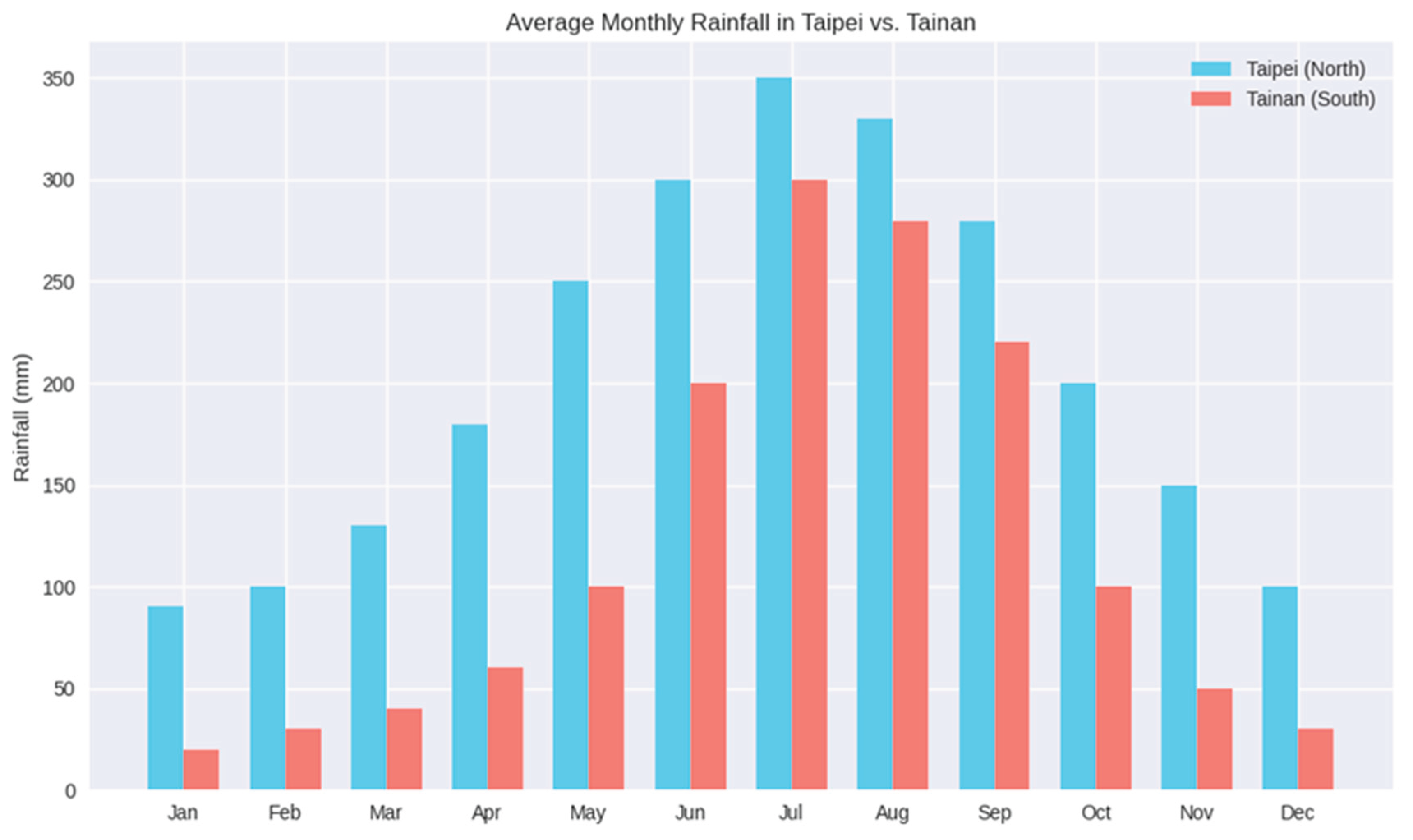

(A) Geographic Disparities: Northern Taiwan generally receives more rainfall than southern regions where often face higher water stress and may incur higher water costs. (B) Infrastructure and Accessibility: Regions with well-developed water infrastructure (e.g., pipelines, treatment plants) have lower distribution costs than the one of remote or mountainous areas due to transportation and pumping works increasing the cost of water extraction and treatment with higher pricing or stricter allocation policies. (C) Urban vs Rural Needs: Urban centers like Taipei and Taichung have different pricing structures compared to rural areas, reflecting differences in water usage patterns, economic capacity, and infrastructure investment.

C. Key Factors Influencing Pricing: In addition to water source availability, treatment and delivery costs, and usage type, several broader considerations influence water pricing. These include policy and regulatory frameworks, environmental impacts, and economic conditions, all of which shape the feasibility and equity of pricing strategies. Dynamic pricing models provide flexible frameworks that adjust water tariffs in response to changing hydrological and socio-economic conditions. In Taiwan, such models aim to: Enhance Allocation Efficiency – Ensure that water is distributed across domestic, agricultural, and industrial sectors in proportion to actual demand and scarcity. Promote Conservation – Encourage reduced consumption during periods of stress by reflecting real-time water availability in pricing. Support Equity and Affordability – Balance economic efficiency with social considerations, ensuring that essential domestic needs remain accessible. Incorporate Environmental Externalities – Integrate ecological costs, such as groundwater depletion and reservoir sedimentation, into pricing structures. Strengthen Policy Integration – Align pricing mechanisms with national water management strategies and regulatory frameworks to improve governance. 1. Reflect seasonal water availability (wet vs dry seasons). 2. Account for regional cost differences in water extraction and delivery. 3. Promote sustainable consumption by discouraging waste during scarcity. Dynamic pricing models for surface water in Taiwan adjust rates according to seasonal availability and regional supply costs, thereby promoting efficient and sustainable water use. The key impact factors associated with dynamic pricing include: Behavioral Change – Regions implementing dynamic pricing observed a 10–20% reduction in non-essential water use during peak pricing periods, indicating that tariff adjustments can effectively influence consumer behavior. Revenue Stability – Water utilities reported more predictable revenue streams under dynamic pricing schemes, which facilitated long-term infrastructure planning and maintenance. Environmental Benefits – Reduced over-extraction during dry seasons helped maintain ecological flows in rivers and reservoirs, contributing to improved ecosystem resilience. These findings highlight the potential of dynamic pricing to balance economic efficiency, social equity, and environmental sustainability. Recent studies underscore the complexity of groundwater management in Taiwan. Huang and Shih[

17]developed seasonal hydrological models to forecast groundwater levels, providing a foundation for adaptive pricing strategies. Patra et al.[

18]applied long short-term memory (LSTM)–based forecasting to predict regional groundwater fluctuations, demonstrating the potential of artificial intelligence in water resource planning. Research published in Frontiers in Earth Science[

19]further linked groundwater over-extraction to land subsidence in the Choushui River Alluvial Fan, emphasizing the environmental costs of unsustainable groundwater use. Together, these findings highlight the need for integrated approaches that combine hydrological modeling, advanced forecasting techniques, and policy interventions. Incorporating AI-driven predictions into groundwater management frameworks can improve resilience, while addressing the ecological risks associated with over-extraction. These studies employ comparative analyses of groundwater pricing across Taiwan’s regions and seasons, supported by synthesized data from government reports and academic studies, as well as visual modeling of pricing differences (

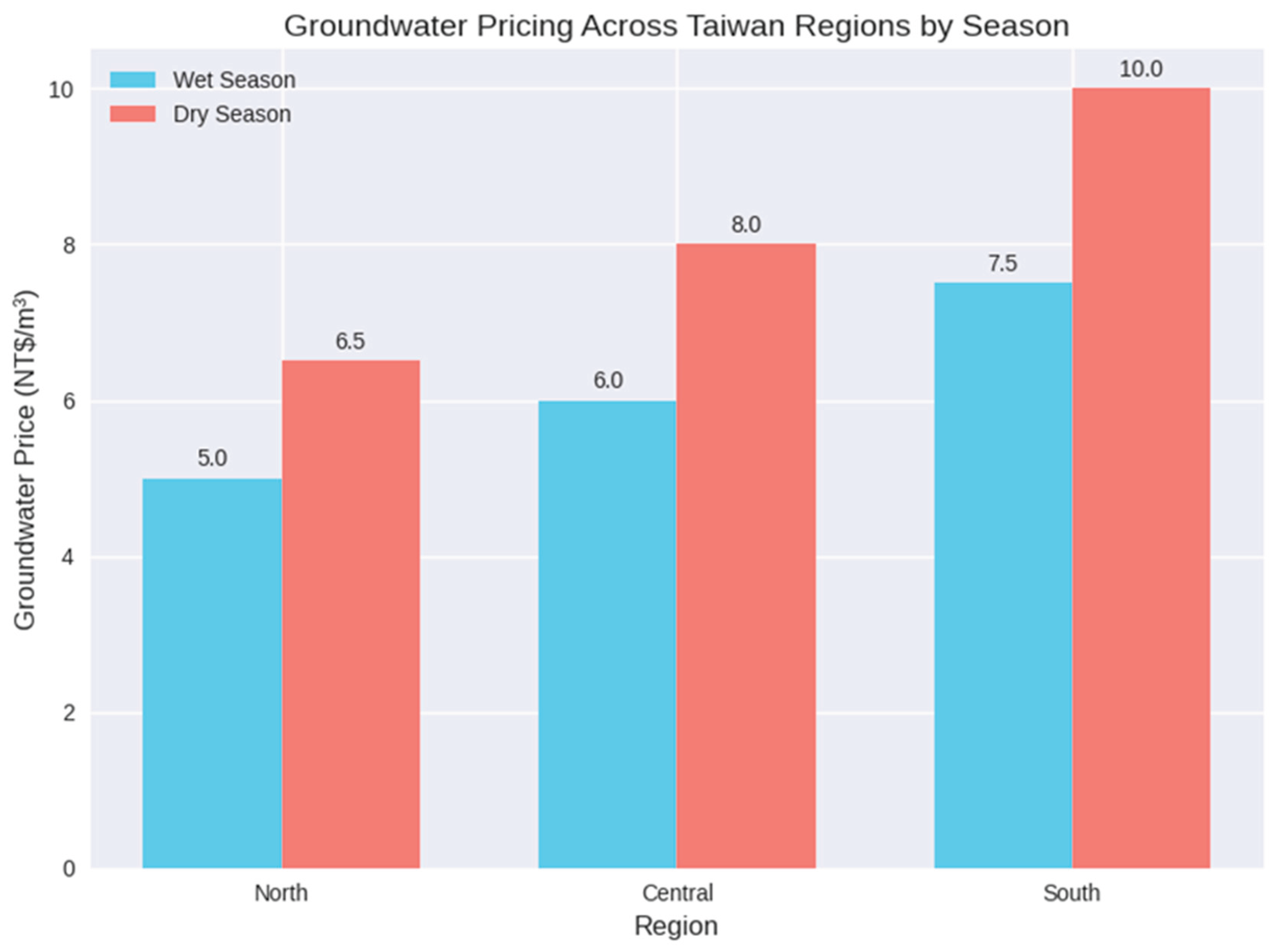

Figure 11,

Figure 12). The results indicate that seasonal and regional variations in groundwater pricing are relatively minor. However, geological characteristics and the environmental impacts of extraction must be incorporated into pricing analyses. Physical and mechanical factors—such as aquifer properties, subsidence risks, and recharge capacity—are critical for policy review of dynamic pricing mechanisms and regulatory frameworks.

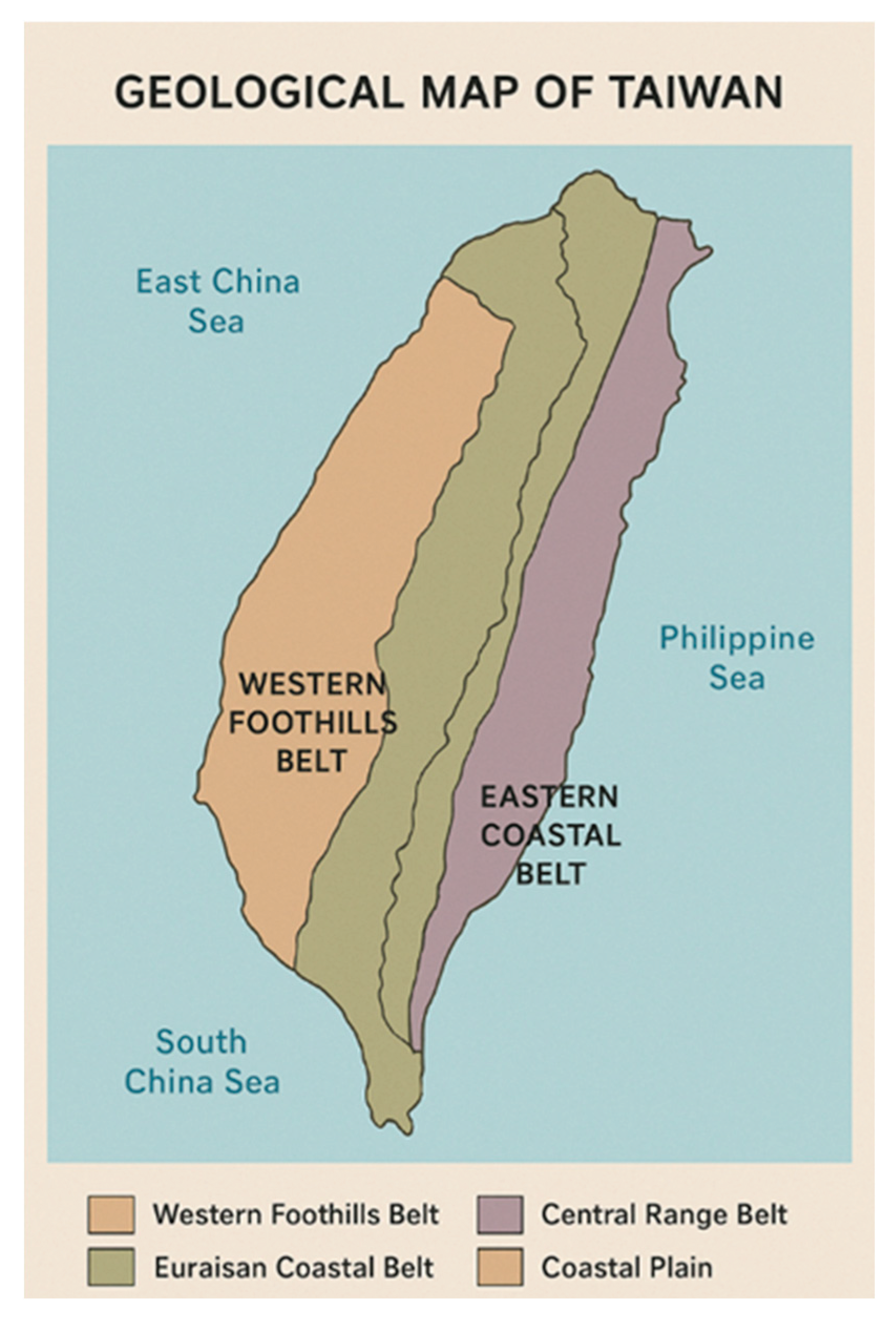

A. Regional Differences in Groundwater Pricing

Although regional pricing differences are relatively limited, geological conditions exert significant influence on groundwater sustainability. Areas characterized by fragile alluvial fans or high subsidence risks require stricter regulatory oversight and potentially higher tariffs to internalize environmental costs. Conversely, regions with more stable aquifers may sustain lower pricing levels, provided that extraction remains within ecological limits.

Southern Taiwan: Groundwater costs are significantly higher than in northern and central regions due to (1) lower rainfall and higher drought frequency, (2) greater reliance on groundwater for agriculture and industry, resulting in increasing extraction pressure, and (3) higher infrastructure and pumping costs associated with deeper aquifers and salinity issues.

Northern Taiwan: More abundant surface water resources and better-developed infrastructure reduce reliance on groundwater, leading to lower extraction costs.

B. Seasonal Variations in Groundwater Pricing

Seasonal hydrological fluctuations strongly affect groundwater demand and pricing:

Dry seasons (winter and early spring): Increased demand for irrigation and industrial use elevates pumping costs, often resulting in higher tariffs. Water rationing policies may indirectly influence pricing.

Wet seasons (summer and typhoon periods): Greater surface water availability reduces groundwater demand, stabilizing prices and alleviating extraction pressure.

C. Key Factors Influencing Groundwater Pricing

Groundwater pricing in Taiwan is shaped by multiple interrelated factors:

Hydrological Conditions: Rainfall patterns, aquifer recharge rates, drought frequency, and seasonal water table fluctuations directly affect pumping depth and energy costs.

Usage Type: Agricultural use often benefits from subsidies or lower rates, whereas industrial and commercial users typically face higher tariffs due to larger volumes and pollution risks.

Water Rights and Regulations: Taiwan’s water rights system controls extraction volumes and prioritizes domestic use. Illegal wells and unregulated extraction complicate enforcement.

Infrastructure and Technology: Advanced monitoring and metering systems enable dynamic pricing, while regions lacking infrastructure rely on flat or estimated rates.

Environmental Impact: Over-extraction contributes to land subsidence and saltwater intrusion, prompting stricter controls and higher costs in affected zones.

Policy and Governance: Local governments may adjust rates to meet conservation goals or budgetary needs, while national policies aim to balance equity, sustainability, and economic development.

Dynamic Pricing Models for Groundwater in Taiwan

Dynamic pricing models are designed to reflect real-time water availability and extraction costs, thereby promoting conservation and equitable access. Several approaches are emerging in Taiwan:

Seasonal Tariff Adjustments: Higher rates during dry seasons discourage overuse and reflect increased pumping costs, while lower rates in wet seasons align with greater surface water availability.

Regional Cost Differentiation: Tariffs incorporate local aquifer stress, subsidence risk, and infrastructure costs. Southern regions such as Tainan and Kaohsiung face higher rates due to deeper wells and salinity issues.

Usage-Based Tiered Pricing: Progressive rates charge lower tariffs for basic needs and higher rates for excessive consumption, encouraging efficiency and discouraging waste.

Forecast-Integrated Pricing: Advanced models, including LSTM-based groundwater forecasting, predict aquifer levels and adjust tariffs proactively during droughts or recharge periods.

Environmental Impact Surcharges: Additional fees are imposed for extraction in subsidence-prone zones, with revenues allocated to aquifer restoration and monitoring programs.

IV. Technologies and Innovation of Results

Taiwan has set an ambitious target of achieving a reclaimed water capacity of 1.32 million m³/day by 2031. Despite this goal, the island continues to experience an average annual water shortage of 530.6 million m³, primarily driven by uneven rainfall distribution and the impacts of climate change. This trajectory reflects Taiwan’s transition from short-term emergency responses toward long-term sustainability planning.

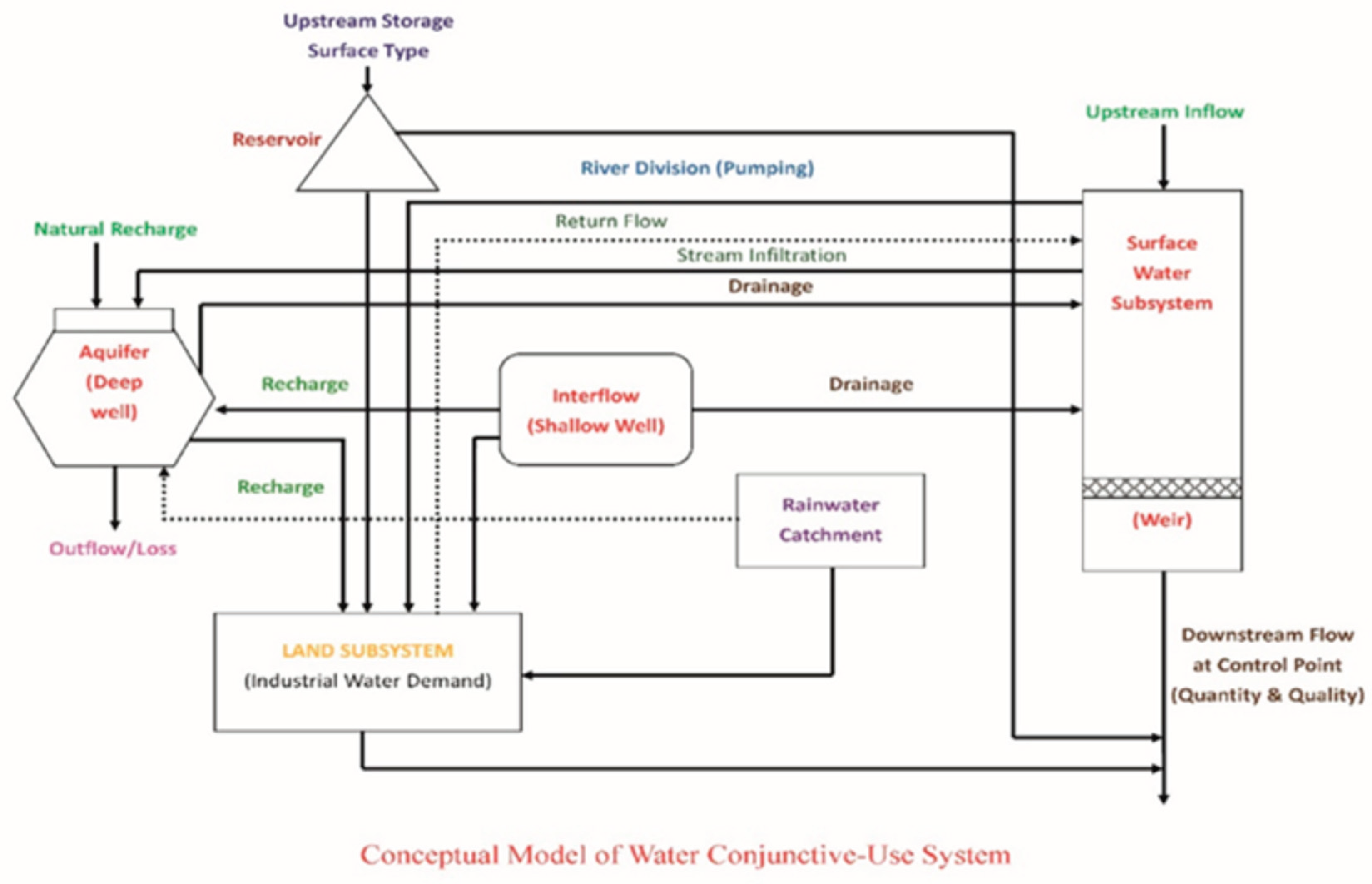

The national water resource allocation strategy integrates both surface and groundwater management (

Figure 13) through diversification, conservation, and adaptive planning. Key measures include infrastructure development, watershed governance, and cross-regional coordination, all designed to enhance resilience against climate variability and regional disparities.

By analyzing Taiwan’s multi-source strategy, technological innovations, and policy frameworks, this study underscores the importance of adaptive mechanisms and sustainability objectives. Water resource management has become a sensitive yet critical issue, requiring balanced approaches that combine hydrological science, technological advancement, and institutional reform. Ultimately, Taiwan’s path forward lies in building a robust, flexible, and equitable water governance system capable of ensuring long-term water security under changing environmental conditions.

The Water Resources Department emphasizes that groundwater, surface water, and reservoir water are all critical sources. During droughts, groundwater serves as a more stable source of emergency relief. Mitigation strategies promoted by the department include encouraging greater reliance on surface water and constructing reservoirs and artificial lakes, such as the Hushan Reservoir, to reduce dependence on groundwater. Nevertheless, Taiwan continues to face severe groundwater management challenges, rising consumption, and climate change pressures, all within constrained financial resources.

Key Strategic Pillars for Taiwan’s Water Sustainability and Resilience

Incorporation of External Costs – Integrating industrial wastewater treatment and environmental remediation costs into water pricing frameworks.

Diversification of Water Sources – Expanding surface water infrastructure and artificial lakes to reduce reliance on groundwater.

Adaptive Groundwater Management – Strengthening monitoring and regulation to address subsidence risks and over-extraction.

Climate-Responsive Planning – Embedding resilience measures into water allocation strategies to mitigate drought and extreme weather impacts.

Economic and Policy Innovation – Developing financing mechanisms and legal reforms to support sustainable infrastructure and equitable pricing.

Main Strategic Actions

(A) Reservoir expansion and diversification for municipal, agricultural, and ecological supply. (B) Smart water management: digital tools and IoT sensors to monitor usage, detect leaks, and forecast demand. (C) Subsidence control: regulations limiting extraction in vulnerable coastal zones. (D) Reclaimed water initiatives: wastewater treatment and reuse, particularly in industrial zones such as Taoyuan and Tainan, to reduce freshwater demand. (E) Water rights and pricing mechanisms: industrial users subject to quantity controls, tiered pricing, and water rights trading to optimize allocation. (F) Ecosystem protection: allocation plans incorporating environmental flows to sustain riverine and wetland habitats.

The detailed planning and implementation of these strategies are presented in the following sections.

A. Reservoir Dredging and Expansion Using Ecological Engineering Methods for Enhanced Water Storage and Ecological Supply

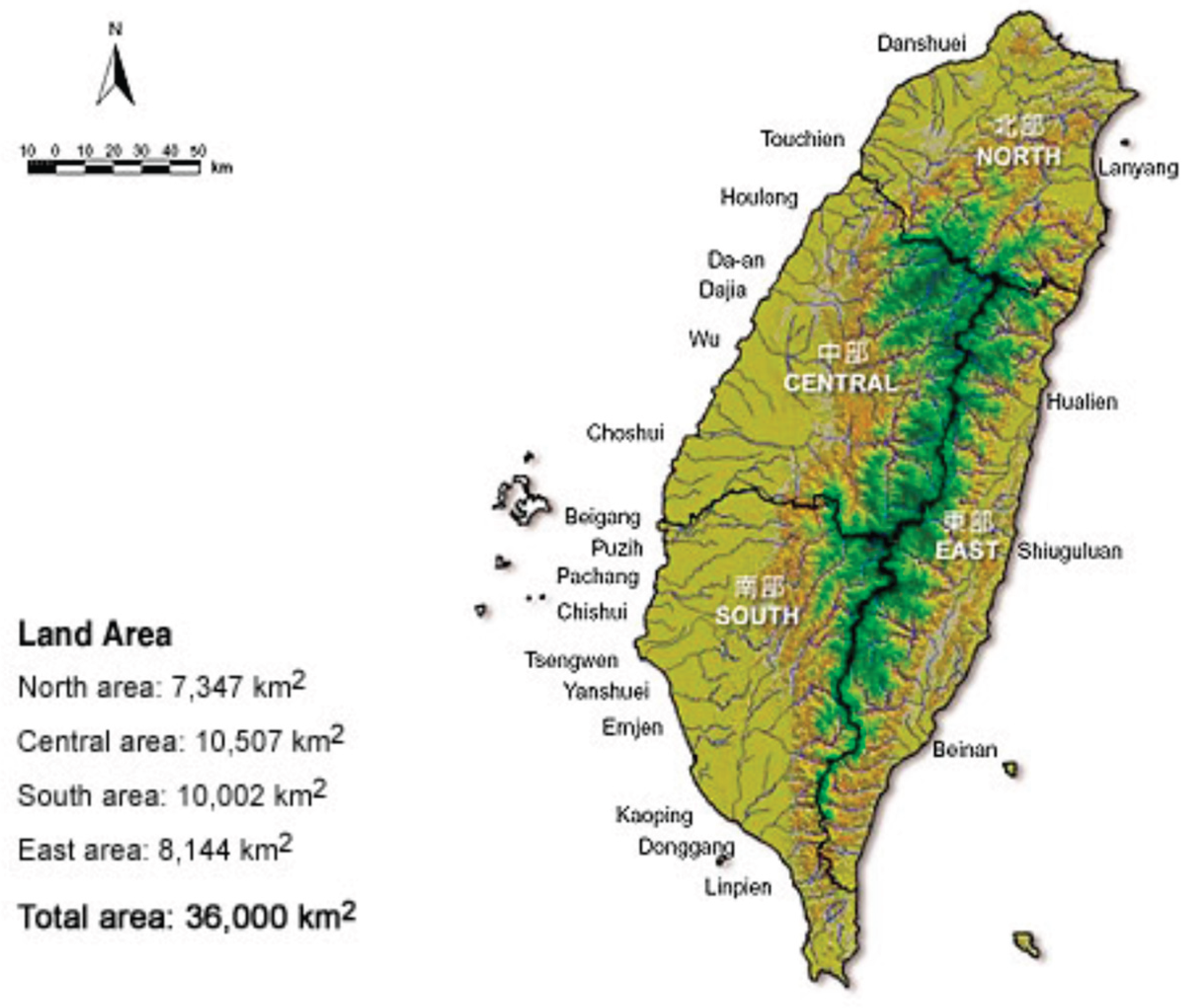

Based on stream discharge data from 19 major rivers (

Figure 5) reported in the

Hydrological Year Book of Taiwan R.O.C. between 1994 and 2022, the hydrological characteristic of the flood-season discharge ratio (flood-season discharge divided by annual discharge) was calculated as follows:

Whole Taiwan Island: 0.548–0.891 (mean = 0.742)

Northern Taiwan: 0.489–0.837 (mean = 0.650)

Central Taiwan: 0.669–0.957 (mean = 0.802)

Southern Taiwan: 0.606–0.948 (mean = 0.820)

Gao-Ping Region: 0.734–0.955 (mean = 0.869)

Taitung Region: 0.429–0.955 (mean = 0.754)

Hualien Region: 0.532–0.797 (mean = 0.679)

Yilan Region: 0.498–0.853 (mean = 0.618)

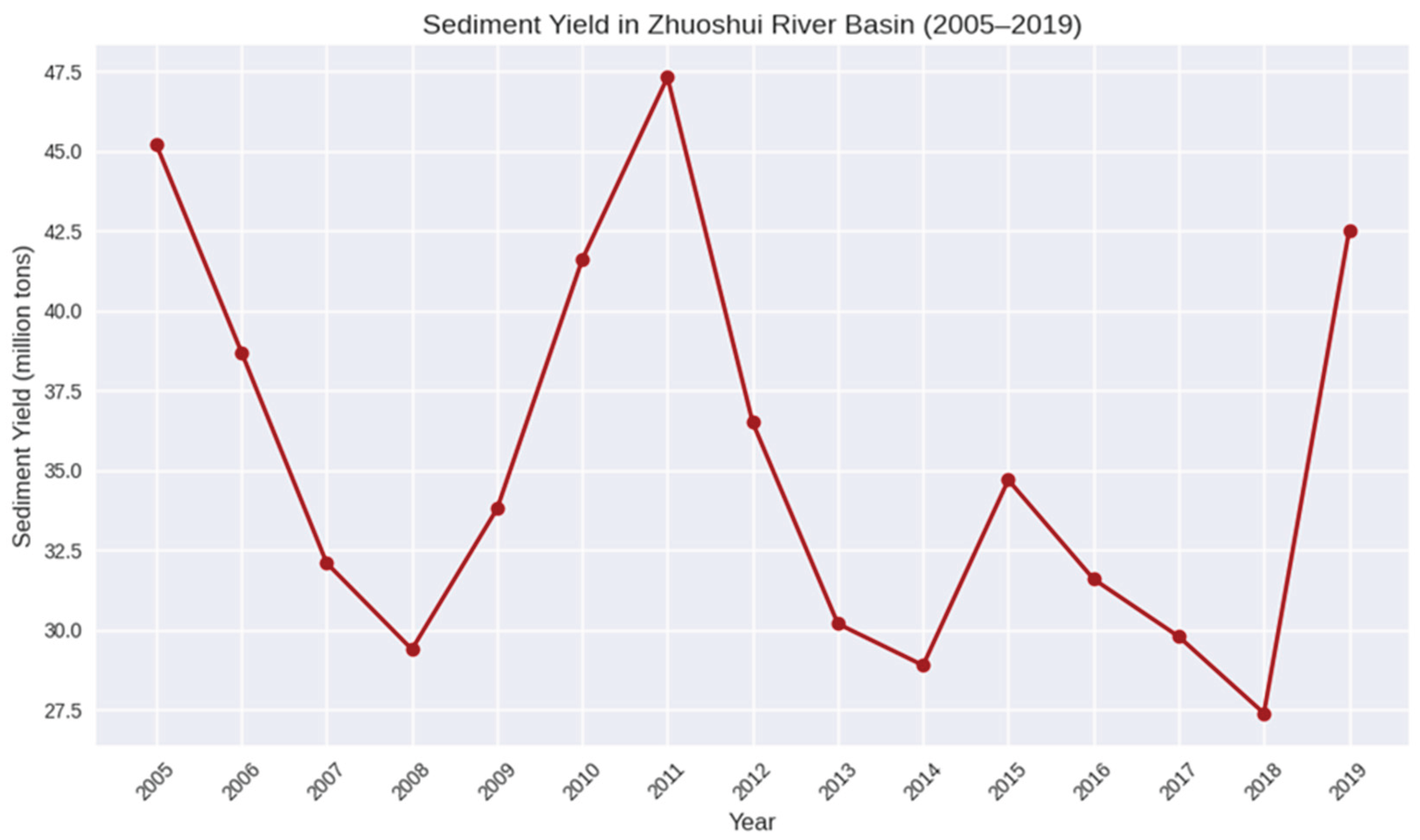

A higher ratio of rainfall and discharge indicates an increased risk of water shortage. Taiwan’s river basins are shaped by steep terrain, intense rainfall, and fragile geology, resulting in extreme sediment transport and dynamic hydrology. The Zhuoshui River Basin (

Table 4) alone produces the highest sediment load in the country[

22,

23].

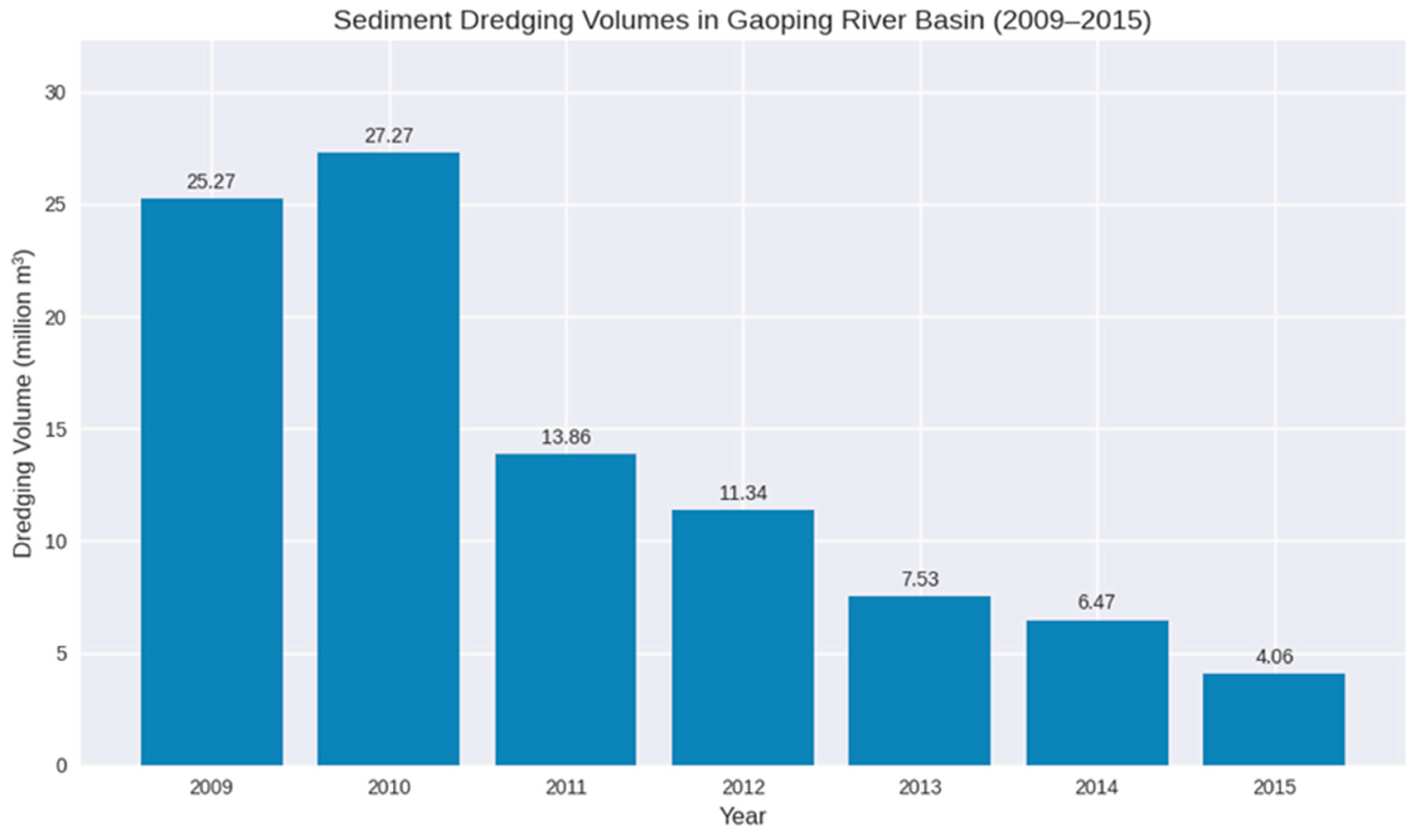

Reservoir Management in the Zhuoshui and Gaoping River Basins

The Zhuoshui and Gaoping River Basins are among the most dynamic hydrological systems in East Asia, shaped by Taiwan’s steep terrain and intense rainfall (

Figure 14,

Figure 15). Reservoirs in these basins lose storage capacity annually, particularly in mountainous regions, due to heavy sedimentation. Concurrently, Taiwan faces increasing challenges in water resource management driven by climate variability and rising demand[

26,

27]. Seasonal water shortages highlight the urgent need for reliable storage recovery and sustainable allocation strategies.

Traditional dredging methods, although effective in restoring reservoir capacity, are costly and ecologically disruptive. A sustainable approach must therefore integrate ecological engineering methodologies into long-term water resource allocation strategies. Such an approach emphasizes cost-effectiveness, environmental stewardship, and adaptive planning.

Key Elements of Sustainable Reservoir Dredging

Environmentally sound dredging practices to restore reservoir capacity while minimizing ecological disturbance.

Nature-based solutions such as sediment bypassing, guiding channels, and watershed management to reduce sediment inflow.

Adaptive scheduling that aligns dredging operations with water demand cycles and climate resilience objectives.

Integrated monitoring and planning to ensure long-term sustainability and cost-efficiency.

By embedding ecological engineering into reservoir management, Taiwan can balance the dual objectives of maintaining storage capacity and protecting riverine ecosystems. This integrated strategy enhances resilience against climate variability while ensuring sustainable water allocation for agriculture, industry, and domestic use.

(A) Cost Analysis and Economic Considerations

Integrating dredging with sustainability requires balancing ecological benefits with financial feasibility.

1. Capital and Operational Costs – A detailed comparison of expenditures is presented in

Table 5 (exchange rate: 1 USD = 30 NTD).

2. Cost–Benefit of Storage Recovery

Dredging can restore millions of cubic meters of reservoir storage, thereby reducing the need for new reservoir construction. This approach provides a cost-effective alternative to large-scale infrastructure projects while enhancing water security.

3. Environmental Externalities

Integrating ecological engineering into dredging practices reduces long-term costs by minimizing habitat disruption and lowering water treatment requirements. Moreover, sustainable sediment management helps avoid fines or remediation expenses associated with poor environmental practices.

4. Funding and Policy Support

Sustainable dredging has been prioritized under the Water Resources Agency’s climate adaptation framework. In addition, partnerships with water utilities provide financial and institutional support for dredging projects, ensuring alignment with national resilience objectives.

(B) Integration Strategy

To reliably integrate dredging with sustainable water allocation, the following measures are recommended:

1. Employ ecological engineering techniques to reduce sediment inflow.

2. Apply cost-effective dredging methods tailored to specific reservoir conditions.

3. Coordinate dredging operations with water demand forecasts and ecological monitoring.

4. Leverage public–private partnerships to secure funding and foster innovation.

(C) Expected Outcomes

1. Reservoir capacity increased by 10–20% within five years.

2. Reduced dredging frequency and minimized ecological disturbance.

3. Improved water allocation efficiency during drought conditions.

4. Enhanced Resilience to Climate Variability

Effective reservoir dredging in Taiwan requires careful planning and the integration of ecological engineering principles. The following considerations are essential to ensure sustainability, safety, and regulatory compliance:

(A) Work Plan and Review Comprehensive planning and periodic review of dredging projects are necessary to align operations with long-term water resource strategies.

(B) Dredging Timing

Emergency dredging: Immediate intervention is required when typhoons, torrential rains, debris flows, earthquakes, or other disasters cause river blockages or impair the function of water conservancy facilities.

General dredging: Conducted when siltation does not pose immediate safety risks, often coordinated with sand and gravel supply policies or to maintain reservoir sand-trapping functions.

(C) Construction Methods and Equipment Appropriate machinery (e.g., dredgers, sand pumps) must be selected according to technical specifications. Inspection, measurement, and pricing systems should be established to ensure project quality and accountability.

(D) Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) For disaster recovery and reconstruction projects, EIA requirements may be waived upon review but must still be submitted to the competent authority for record-keeping. General dredging projects require full EIA compliance to prevent damage to aquatic ecosystems.

(E) Soil and Rock Removal and Management Materials generated from dredging must be managed under either “separation of procurement and sale” or “integrated procurement and sale” systems to prevent illegal sand mining. All practices must comply with the Government Procurement Act and River Management Regulations.

(F) Safety and Monitoring Construction activities must account for water level fluctuations and prioritize worker and equipment safety. Monitoring systems should be established to track siltation status and water quality changes in reservoirs.

Integrative Perspective

By combining ecological engineering with strategic planning, Taiwan can restore reservoir capacity while safeguarding ecosystems and optimizing water resource allocation. This integrated approach provides a replicable model for sustainable water infrastructure in sediment-prone regions, balancing cost-efficiency, environmental stewardship, and climate resilience.

B. Treatment Cost for Industrial Wastewater

The treatment cost of industrial wastewater represents a critical component of Taiwan’s broader water sustainability framework. Incorporating cost analyses into policy design ensures that industrial users internalize environmental externalities. By integrating wastewater treatment expenses into water pricing mechanisms, Taiwan can promote equitable resource allocation while reducing long-term remediation costs.

The treatment cost for industrial wastewater in Taiwan is determined by effluent standards, treatment technology, wastewater characteristics, and operational factors. A structured cost analysis methodology typically includes capital costs, operating costs, and compliance costs.

Taiwan’s effluent standards are regulated under the Water Pollution Control Act and industry-specific guidelines issued by the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA). These standards define permissible limits for pollutants such as biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), suspended solids (SS), heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Pb), pH, temperature, and other parameters.

For cost calculations, it is necessary to first define the industry type and plant size. In this study, the following assumptions are applied:

Industry: Electronics manufacturing (a major sector in Taiwan)

Plant size: 1,000 m³/day of wastewater discharge

Based on these assumptions, five main cost categories are established (

Table 6), and a sample cost calculation is provided (

Table 7).

Total Annual Cost of Industrial Wastewater Treatment

Based on the unit cost calculation, the total annual treatment cost is approximately NT$ 3,740,000.

Cost per m³ = NT$ 3,740,000 ÷ (365 × 1,000) ≈ NT$ 10.25/m³.

A sensitivity analysis further highlights the influence of chemical price fluctuations, energy cost increases, and stricter effluent standards requiring advanced treatment technologies.

Case Study: Semiconductor Manufacturing

Industries such as semiconductor manufacturing are subject to tailored effluent standards listed in Taiwan’s official regulatory tables. For a semiconductor plant discharging 1,000 m³/day, the estimated costs are as follows:

Capital cost: NT$ 50–80 million for advanced treatment → Equivalent to NT$ 137–219/m³

Operating cost: NT$ 10–20/m³ depending on pollutant load

Monitoring cost: NT$ 100,000–300,000/year → Equivalent to NT$ 0.27–0.82/m³

Total cost: NT$ 147.27–239.82/m³

These figures vary depending on location, technology selection, and discharge quality, underscoring the importance of site-specific cost assessments.

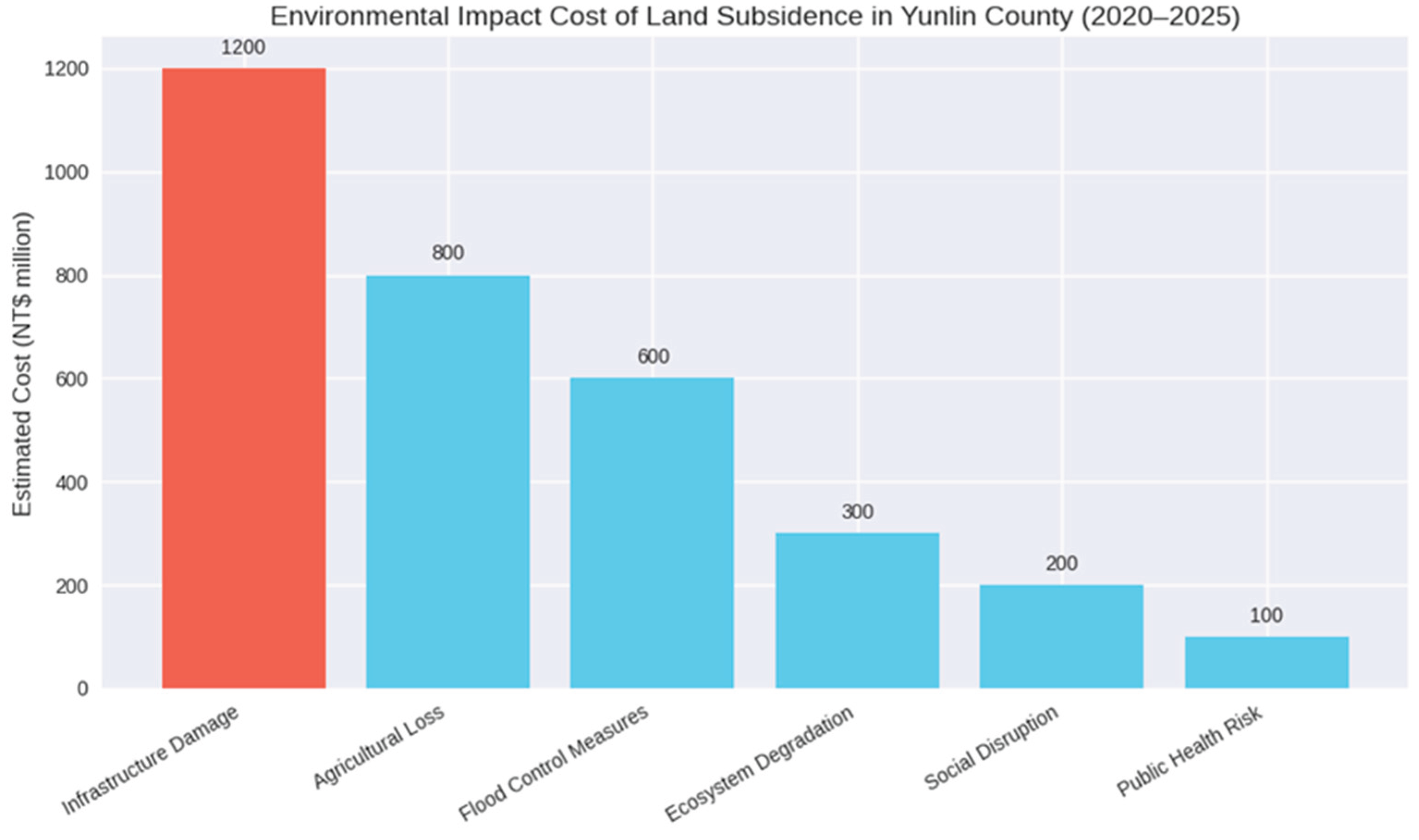

C. Environmental Impact Cost of Land Subsidence

In Taiwan, the environmental impact cost of land subsidence resulting from groundwater extraction is assessed using integrated geospatial, hydrogeological, and economic modeling techniques. These methods quantify physical damage, economic loss, and ecological degradation.

Hydrogeological surveys track groundwater levels, aquifer properties, and pumping volumes.

Geological mapping identifies vulnerable zones, particularly in alluvial plains such as the Choushui River Fan and Yunlin–Changhua areas.

GNSS data, combined with hydrogeological integration, supports subsidence modeling.

Spatio-temporal models integrating Kriging interpolation with heterogeneous measurement error filtering estimate subsidence across regions with varying data quality.

Coupled hydro-mechanical models simulate how groundwater extraction affects soil compaction and surface deformation, providing a robust methodology for subsidence dynamics.

Environmental Impact Cost Components:

To estimate the environmental impact cost of land subsidence, the following categories must be considered (summarized in

Table 8 and

Table 9):

Physical Damage Costs

Structural damage to buildings, roads, bridges, and public infrastructure.

Repair and maintenance expenditures associated with subsidence-induced deformation.

Economic Losses

Reduced agricultural productivity due to soil compaction and altered irrigation capacity.

Losses in industrial and commercial activities caused by infrastructure instability.

Ecological Degradation Costs

Impacts on riverine and wetland ecosystems due to altered hydrological regimes.

Decline in biodiversity and ecosystem services linked to subsidence.

Social and Public Safety Costs

Increased risk to communities in subsidence-prone areas.

Costs associated with relocation, insurance, and disaster relief.

Monitoring and Mitigation Costs

Investment in GNSS, hydrogeological surveys, and spatio-temporal modeling systems.

Implementation of groundwater management policies and subsidence prevention measures.

Valuation Techniques

To assess the environmental and economic impacts of groundwater extraction and land subsidence, the following valuation techniques are applied:

(A) Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) Surveys of local residents are conducted to determine their willingness to pay for mitigation measures.

Replacement Cost Method Estimates the cost required to restore damaged assets and infrastructure.

(B) Cost–Benefit Analysis (CBA) Compares the costs of mitigation strategies against avoided damages to evaluate overall efficiency.

Policy Integration and Regulation

Taiwan’s Water Resources Agency incorporates these valuation techniques into mitigation planning through the following mechanisms:

(A) Groundwater Control Zones

Designation of high-risk areas as priority zones with strict pumping restrictions.

Promotion of surface water substitution and expanded use of recycled water.

(B) Monitoring and Feedback

Establishment of real-time monitoring stations to track groundwater levels and subsidence.

Application of adaptive management frameworks to update policies based on new data.

(C) Implementation and Evaluation

Enforcement of pumping restrictions and promotion of alternative water sources.

Evaluation of mitigation effectiveness using feedback loops derived from updated subsidence and cost data.

By combining valuation techniques with regulatory frameworks, Taiwan advances a comprehensive approach to groundwater management. This integration ensures that economic efficiency, environmental sustainability, and social equity are simultaneously addressed, thereby strengthening resilience against subsidence and long-term water scarcity.

Yunlin County Case Study

Yunlin County provides a representative example of subsidence management. In some zones, annual subsidence reaches up to 5 cm/year, with estimated costs for 2020–2025 (

Figure 16) as follows:

Infrastructure: NT$ 1.2 billion

Agriculture: NT$ 800 million

Flood control: NT$ 600 million

Ecosystem degradation: NT$ 300 million

Social disruption: NT$ 200 million

Public health risk: NT$ 100 million

Total impact: ~NT$ 3.2 billion over five years (~NT$ 0.64 billion per year).

According to the Water Resources Agency:

In 2022, land subsidence covered 239.5 km² at 10 cm, corresponding to 23,950,000 m³.

In 2023 (a severe drought year), subsidence covered 247.7 km² at 8 cm, corresponding to 19,816,000 m³.

In 2024, subsidence covered 226.4 km² at 6 cm, corresponding to 13,584,000 m³.

The mean three-year subsidence volume is 19,117,000 m³. With annual spending of NT$ 640 million on subsidence control, the cost per m³ is calculated as:

640,000,000 NT$/19,117,000=NT$ 33.50/

Infrastructure damage is the largest contributor, accounting for nearly 38% of total costs. Agricultural losses and flood control expenditures are also significant, reflecting the region’s vulnerability to soil degradation and flooding.

D. Seawater Desalination and Rainwater Harvesting Costs

Taiwan faces significant water resource challenges due to its geography, climate variability, and industrial demands. To address these challenges, the Water Resources Agency promotes alternative water sources, including seawater desalination and rainwater harvesting. These approaches[

33,

34] can be integrated into Taiwan’s water resource strategy by diversifying supply sources, thereby enhancing resilience and reducing reliance on conventional freshwater systems, especially in drought-prone and industrial zones.

(A) Seawater Desalination: Strategic Integration

Seawater desalination provides a stable, drought-proof water source, particularly for coastal and industrial regions.

1. Key Developments

CTCI’s Desalination Plant in Hsinchu: Taiwan’s largest seawater desalination project, supporting semiconductor industries.

Partnerships with SUEZ and Hung Hua Construction: Introduction of advanced reverse osmosis (RO) and energy-efficient technologies.

2. Integration Strategies

Industrial zoning: Desalinated water is prioritized for high-tech parks (e.g., Hsinchu Science Park), reducing pressure on municipal supplies.

Grid connectivity: Desalination plants are linked to regional water grids for flexible allocation during droughts.

Energy optimization: Co-location with renewable energy sources (solar/wind) reduces the carbon footprint.

3. Seawater Desalination Costs

Capital costs:

Large-scale RO plants: NT$ 1.5–2.5 billion for 100,000 m³/day capacity.

Small-scale modular units (5–20 tons/hour): NT$ 10–50 million.

Operating costs:

Energy accounts for ~50–60% of total cost; RO systems consume 3–5 kWh/m³.

Maintenance includes membrane replacement, chemical dosing, and staff salaries.

Water production cost: NT$ 25–40/m³ (US$ 0.8–1.3/m³).

Use cases: High-tech parks (e.g., Hsinchu), coastal cities, and drought-prone zones.

(B) Rainwater Harvesting: Localized Resilience

Rainwater harvesting[

35,

36,

37] complements centralized systems by capturing runoff for non-potable uses.

1. Applications

Urban buildings: Rooftop systems collect rainwater for flushing, irrigation, and cooling.

Agricultural zones: On-farm reservoirs store rainwater for crop irrigation during dry spells.

Schools and public facilities: Promote awareness and reduce municipal demand.

2. Integration Strategies

Regulatory incentives: Building codes encourage rainwater systems in new developments.

Smart monitoring: IoT sensors track rainfall and tank levels to optimize usage.

Community-scale systems: Shared tanks in rural areas support multiple households.

3. Rainwater Harvesting Costs

Capital costs:

Household rooftop systems: NT$ 30,000–80,000.

Institutional/commercial systems: NT$ 200,000–1 million.

Agricultural reservoirs: NT$ 500,000–2 million, depending on size.

Operating costs:

Minimal energy use (gravity-fed or passive systems).

Occasional cleaning and pump maintenance.

Water production cost: NT$ 5–15/m³, depending on reuse (non-potable vs. potable).

Use cases: Urban buildings, schools, farms, and community tanks.

(C) Integrated Water Resource Allocation

To reliably integrate seawater desalination and rainwater harvesting, Taiwan employs a multi-source, adaptive management approach

. The comparative framework is summarized in

Table 10, which highlights:

Diversification of supply sources.

Cost-effectiveness across scales (industrial vs. community).

Environmental sustainability through reduced groundwater dependence.

Enhanced resilience to drought and climate variability.

Now we need analyze the cost of seawater desalination and rainwater harvesting in detail and draft a policy proposal or visualizing this integration in a diagram.

Seawater desalination in Taiwan costs NT$25–40/m³, while rainwater harvesting ranges from NT$5–15/m³ depending on scale and reuse purpose. A balanced policy should prioritize desalination for industrial zones and rainwater harvesting for urban and agricultural resilience.

For meeting the purposes to diversify water sources to reduce drought vulnerability, prioritize cost-effective and region-specific solutions, and promote sustainable water reuse and conservation, we suggest the strategy policy on integrating the Water Strategy of sea water desalination and rainwater harvesting for Taiwan as following

Table 11.

By integrating seawater desalination and rainwater harvesting into its water resource allocation, Taiwan enhances resilience, sustainability, and supply security. These technologies are not replacements but complements to traditional sources, forming a robust water strategy for the future.

E. Taiwan’s Smart Water Technologies: Leading the Digital Wave

Taiwan is emerging as a global leader in smart water management, driven by climate stress, limited freshwater resources, and rapid urbanization. One of the key resilience strategies is the deployment of smart water technologies, which integrate infrastructure, digital systems, and innovation platforms to enhance sustainability and efficiency.

(A) Smart Water Infrastructure

Development of real-time monitoring systems for water flow and quality.

Automated leak detection to reduce losses and improve reliability.

AI-powered demand forecasting to optimize allocation and anticipate stress conditions.

(B) Digital Water Systems

Transition to “Digital Water” platforms that integrate IoT sensors for flow, pressure, and quality monitoring.

Application of big data analytics to optimize operations and improve decision-making.

Use of digital twins to simulate and manage water networks under varying climate and demand scenarios.

(C) Innovation Hubs and Exhibitions

Establishment of resilience planning events focused on droughts and typhoons.

Public–private collaboration with the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) to pilot smart solutions.

Emphasis on scalability and the development of exportable models for other water-stressed regions.

By combining smart infrastructure, digital platforms, and collaborative innovation, Taiwan is positioning itself as a pioneer in adaptive water governance. These technologies not only strengthen domestic resilience but also provide transferable models for global regions facing similar climate and resource challenges.

F. AI Assisting and Insuring the Sustainability and Resilience on Allocation of Water of Taiwan.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can significantly enhance Taiwan’s water sustainability and resilience by enabling smarter forecasting, real-time monitoring, and adaptive resource management. Its applications in water allocation strategies include:

(A) Long-Term Water Resource Assessment

AI models simulate and predict water availability in major reservoirs such as Shihmen, which is critical for managing seasonal variability and droughts.

Techniques including Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) forecast inflow patterns and optimize reservoir operations, improving allocation across agriculture, industry, and domestic sectors.

(B) Smart Water Management Platforms

In Tainan, the 5G Smart Water Information Cloud Platform integrates IoT sensors, 5G networks, and blockchain to monitor water quality and quantity in real time.

The system includes smart water level gauges, oil and grease detectors, and debris recognition tools, enabling early warnings up to 30 minutes before anomalies occur.

This platform supports high-tech industries, particularly semiconductors, by ensuring a stable supply of high-quality recycled water.

(C) AI-Driven Water Recycling and Reuse

AI optimizes wastewater treatment and reuse, converting municipal wastewater into industrial-grade water.

By analyzing sensor data, AI dynamically adjusts treatment processes, improving efficiency and reducing energy consumption.

(D) Decision Support for Policymakers

AI tools provide data-driven insights for government agencies to plan allocation policies under climate change scenarios.

These systems simulate “what-if” scenarios to assess the impacts of droughts, typhoons, or population growth on demand and supply.

Publications on AI empowerment for water resources offer practical frameworks and case studies for engineers, planners, and decision-makers.

(E) Promotion of Resilient Water Governance

Taiwan’s integrated approach—combining AI, 5G, and IoT—serves as a model for smart, resilient water governance.

As climate variability intensifies, these systems will be essential for ensuring equitable, efficient, and sustainable water distribution across regions and sectors.

By embedding AI into water resource management, Taiwan strengthens its adaptive capacity to climate variability while advancing technological innovation. This approach not only enhances domestic resilience but also provides a transferable governance model for other water-stressed regions worldwide.

V. Discussion and Conclusions

The models presented in this study are supported by hydrological simulations and monitoring systems that incorporate land subsidence tracking and seasonal recharge projections. Findings indicate that Taiwan’s groundwater pricing system lacks sufficient flexibility to respond to seasonal and regional pressures. Dynamic pricing models provide a viable solution but face implementation challenges, including infrastructure gaps, legal constraints, and public resistance. To be effective, such models require:

Investment in monitoring infrastructure to ensure reliable data collection and system performance.

Legal reforms that enable flexible tariff structures and adaptive governance.

Public engagement to promote equity, transparency, and social acceptance.

Taiwan’s groundwater pricing must evolve to reflect the realities of seasonal scarcity and regional stress. Dynamic pricing models—grounded in hydrological forecasting and environmental accountability—can promote sustainable water use and protect vulnerable aquifers. Future research should prioritize the integration of real-time data and the expansion of pilot programs to test adaptive pricing strategies.

The research[

20]highlighted significant regional and seasonal cost differences in raw water supply, suggesting that uniform pricing models may be inefficient. Building on this insight, the present study proposes a dynamic pricing framework tailored to Taiwan’s unique hydrological and geographic conditions. Key conclusions are:

Uniform pricing models are inadequate for addressing Taiwan’s diverse hydrological and regional contexts.

Dynamic pricing frameworks can enhance efficiency, sustainability, and resilience in water resource management.

Integration of hydrological forecasting and AI-based monitoring offers promising pathways for adaptive pricing strategies.

Policy innovation and stakeholder participation are essential to ensure equitable and transparent implementation.

These models, supported by hydrological simulations and monitoring systems, reveal that Taiwan’s groundwater pricing system lacks the flexibility to respond to seasonal and regional pressures. Dynamic pricing offers a promising path forward but requires coordinated investment, legal adaptation, and public acceptance.

In particular,[

20]provided important insights into seasonal and regional water price differences across domestic, agricultural, and industrial sectors. However, these analyses did not fully account for the costs of complete treatment, which poses risks of externalizing environmental and ecological restoration costs to society. Addressing this gap is critical to achieving the overarching goal of equitable and sustainable water resource allocation.

Integrated Strategies for Water Sustainability in Taiwan

Taiwan has set a target of achieving 1.32 million m³/day reclaimed water capacity by 2031, yet continues to face an average annual shortage of 530.6 million m³ due to uneven rainfall and climate change. This trajectory reflects a transition from short-term resilience measures toward long-term sustainability planning.

A. Reservoir Dredging

Reservoir dredging is not merely a silt removal project but a comprehensive operation involving water conservancy safety, environmental protection, and resource management. Key risks include:

Environmental impact – potential deterioration of water quality and ecological damage.

Construction safety – hazards from fluctuating water levels and unstable weather.

Soil and rock management – risks of illegal sand trading and river damage.

Dredging must adhere to the Water Resources Agency’s Standard Operating Procedures and Construction Specifications to maintain reservoir capacity and ensure downstream safety.

B. Seawater Desalination

Seawater desalination offers a potential solution to water scarcity but presents challenges:

High cost compared to surface, groundwater, or reclaimed water.

Technological dependence on membranes and equipment vulnerable to fouling and failure.

Regional limitations in inland areas requiring water transport and energy supply.

Effective desalination requires careful pretreatment, water quality monitoring, membrane maintenance, and environmentally sound brine discharge management.

C. Groundwater Extraction

Groundwater remains a critical source, particularly during droughts, but requires strict safeguards:

Health risks from pollutants and heavy metals.

Environmental impacts including land subsidence and seawater intrusion.

Sustainability challenges due to finite aquifer capacity.

Scientific planning, rigorous monitoring, and recharge mechanisms are essential to ensure groundwater remains a reliable resource.

D. Integrated Strategy

Taiwan’s sustainability and resilience strategy integrates surface and groundwater management through diversification, conservation, and adaptive planning. Infrastructure development, watershed governance, and cross-regional coordination are central to ensuring long-term water security.

E. Dynamic Pricing Models

Dynamic pricing models that adjust based on seasonal availability and regional supply costs can promote sustainable water use. However, ecological and environmental price considerations remain insufficient. This study addresses that gap by proposing a framework that integrates technological innovation, environmental protection, and adaptive allocation.

F. Policy Implications

Further price analyses incorporating operational technology, environmental impact, and ecological protection have been conducted, leading to effective strategies for technological sustainability and resilience. The key policy implications are:

Incorporation of ecological costs into pricing frameworks.

Integration of multi-source strategies (reservoirs, desalination, groundwater, reclaimed water).

Investment in monitoring and innovation to support adaptive management.

Cross-sectoral governance to balance agricultural, industrial, and domestic demands.

Resilient pricing mechanisms that reflect scarcity, environmental risks, and regional disparities.

Taiwan’s water governance must evolve from reactive measures to proactive, integrated strategies. By embedding ecological engineering, dynamic pricing, and AI-driven monitoring into policy frameworks, Taiwan can strengthen resilience against climate variability while ensuring equitable and sustainable water allocation.

G. Cultural–Ecological Dimensions of Water Governance

Water resource management in Taiwan deeply influences both ecological integrity and cultural heritage, shaping landscapes, livelihoods, and traditional practices. The sustainability and resilience of Taiwan’s water systems must therefore be understood not only in technical and environmental terms but also within the broader cultural fabric of the island.

Key dimensions include:

Surface Water – Pollution from industrial and agricultural sources degrades ecosystems and erodes rivers’ cultural significance.

Groundwater – Over-extraction causes subsidence and saltwater intrusion, undermining rural farming traditions and food security.

Agricultural Water Diversion – Industrial use reduces crop viability and threatens iconic landscapes such as rice paddies and tea plantations.

Industrial Wastewater Treatment – Inadequate treatment harms marine ecosystems and disrupts cultural practices of fishing villages and indigenous communities.

Subsidence – Alters drainage and damages heritage sites, threatening both ecosystems and cultural stability.

Seawater Desalination – Provides modern adaptation but raises ecological concerns and reshapes perceptions of sustainability.

Rainwater Harvesting – Revives traditional water-saving practices, reconnecting communities with ancestral knowledge.

Reservoir Dredging – Maintains storage capacity but must balance ecological impacts with reservoirs’ cultural and recreational roles.

Future strategies should emphasize on the following areas for improvement:

1. Diversified water source development.

2. Smart dispatching and adaptive allocation.

3. Expanded reclaimed water utilization.

4. Comprehensive environmental monitoring.

5. Role of Artificial Intelligence

6. AI technologies can enhance sustainability and resilience by:

7. Real-time monitoring and data analysis.

8. Predictive maintenance of infrastructure.

9. Intelligent dispatching and optimization of water allocation.

10. Anomaly identification and early warning for water quality and supply risks.

H. Challenges of AI integration include:

1. Data integration difficulties requiring unified platforms.

2. High investment costs necessitating joint promotion by policy and industry.

3. Technological dependence, which requires complementary manual monitoring mechanisms.

It is particularly worth mentioning that COVID-19[

38] has had a tremendous impact on the global economy, especially on Taiwan's living costs, employment costs, and public infrastructure costs. These costs were not included in this study; however, they represent an irreparable burden on national society.

Taiwan’s water issues are inseparable from its cultural heritage and ecological sustainability. Addressing them requires balancing modern technological innovation with respect for traditional practices and natural systems. The path forward lies in diversified sources, intelligent dispatching, reuse, and monitoring, supported by AI as a transformative force in water governance. By embedding cultural awareness into technological strategies, Taiwan can build resilient cities and industries capable of withstanding climate change and water scarcity challenges.

By employing "carbon budget management," "carbon reduction strategies for water conservancy projects," and "reasonable water pricing mechanisms" to align with global energy conservation, carbon reduction, and zero-carbon emission goals, and with a core focus on improving Taiwan's water resource efficiency, promoting recycling, and establishing a carbon pricing system, this research proposes reasonable cost reflection, differentiated water pricing, recycling goals, and a social equity perspective. These measures all have positive indicator benefits for the implementation of carbon budget management and the achievement of carbon reduction targets of 40% reduction by 2030 and 50% reduction by 2050 for Taiwan.