1. Introduction

Outcomes of older patients living with cancer are often worse compared to younger cancer patients. While there are multiple overlapping factors influencing these results, comorbidities and frailty have been shown to complicate treatment tolerability [

1].

To address these multifaceted challenges, comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) has been developed. Recently, multiple international studies, such as GAIN [

2] and GAP70+ [

3] conducted in the USA, INTEGERATE [

4] in Australia and GERICO [

5] in Denmark, have shown the benefits of CGA implementation into cancer care. A systematic review including these trials has highlighted that CGA reduces treatment-related toxicities Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade 3-5, improve Quality of Life (QoL) and increase the rate of treatment completion [

6]. Considering the evidence supporting CGA in oncology, several international guidelines, including those from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [

7] and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)-International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force of Cancer in the Elderly [

8], recommend the integration of CGA into cancer care of older adults receiving systemic cancer treatments.

The German evidence-based guideline (“S3-Leitlinie”) on CGA has recently been published and recommends that patients ≥ 65 years with a positive geriatric screening and all patients ≥ 70 years should receive CGA before the start of a new systemic cancer treatment to reduce treatment-related toxicities CTCAE grade 3 or higher [

9].

Despite these recommendations and the strong evidence underlining the benefits of CGA in cancer care, the implementation into routine care is yet to be established in Germany like in most other countries worldwide. Availability of CGA for cancer patients is restricted to few local initiatives [

10,

11].

To overcome these barriers and assess the feasibility to integrate CGA into routine care of older cancer patients in Germany, we conducted the Integration of Geriatric assessment – guided care plan modifications and interventions into clinical paths of older adults with cancer (GORILLA) trial.

2. Methods

The study was registered at German Clinical Trials Register (Deutsches Register für klinische Studien, DRKS), DRKS00035569. Details on study design, its rationale, and the respective questionnaires are published as study protocol elsewhere [

12].

Study Design and Setting

This study was a prospective bicentric feasibility trial performed at the University Hospital Marien Hospital Herne (study center 1) and its respective departments with involvement in cancer care (Urology, Gynecology, Oncology, Geriatrics, Radiation Oncology, and Surgery) and at the University Hospital Ulm (study center 2), Department of Gynecology in cooperation with the Agaplesion Bethesda Clinic, Ulm and the Institute for Geriatric Research of Ulm University.

Participants

Eligibility criteria: Patients ≥ 65 years with a G8 score ≤14 points or ≥ 70 years regardless of their G8 score with newly diagnosed or relapsed cancer prior to MDT discussion were eligible, if they could give informed consent as evaluated by the study personnel. Intended treatment modalities included radiotherapy, surgery, and systemic treatment approaches (e.g. chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, cellular therapy, endocrine therapy, or combined modalities). Patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma, glioblastoma, or acute leukemias were excluded. Patients with basal cell carcinoma or melanoma without intended systemic treatment, or patients who were unable to provide informed consent due to clinically overt dementia and/or language barriers, were also excluded.

Trial Procedures

All patients, regardless of study participation, received a full CGA as part of their routine work-up before their case was discussed during MDT. CGA included the following assessments: ADL (Barthel)[

13], IADL [

14], SARC-F [

15,

16], SPPB [

17], hand grip strength, assessment of comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index [

18]), semi-quantitative hearing and/or visual impairment, social functioning and support (eight questions adapted from ASCO guideline [

19]), psychological health (DIA-S [

20], Psychological Distress Thermometer [

21]), Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [

22], nutrition (MNA-SF) [

23], cognition (Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA, [

24], or Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE, [

25]), and polypharmacy. MMSE was converted into MoCA for better comparability, as recently described. Geriatric interventions were recommended based on the deficits identified in CGA. Following CGA, patients were asked to consent to trial participation, which included data collection and telephone follow-up after three months ± two weeks to assess quality of life (QoL) and functional status. Patients who refused to participate were documented as not willing to participate, without personal identifiers.

A member of the geriatric team presented CGA results during the MDT in the form of a “traffic light” system. This translated into the following: “green”(‘normal functional status/no specific concerns regarding standard treatment’), “yellow”(‘potentially relevant deficit detected, recommended intervention should be considered and standard treatment re-evaluated’), and “red”(‘clinically relevant deficit detected that precludes considered treatment intensity’). Notably, the grading of the traffic light did not reflect a deficit sum score. Instead, it integrated treatment specific risks for subsequent deterioration based on the identified deficits and the anticipated treatment-related toxicities and was rated individually in relation to the intended treatment regimens.

After patient discussion, primary care providers (including medical and radiation oncologists, surgeons, urologists, gynecologists, or palliative care specialists) were asked whether the integration of CGA was beneficial to their clinical decision making and which additional geriatric aspects should be included. After trial completion, selected primary care providers were invited for a qualitative interview. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by RSM and NRN. All participants were interviewed individually in German. We used a preliminary semi-structured interview topic guide which was originally in German. The English translation is published elsewhere [

12].

Study Objectives

This feasibility trial aimed to inform the design of a future study assessing the efficacy and cost effectiveness of implementing CGA into German health services by estimating realistic participation rates in the designated study population.

Primary endpoint: The primary endpoint of this study is to estimate the willingness of participation with an accuracy of ± 7.5%.

Secondary outcomes: The secondary endpoints of this study include the evaluation of feasibility and quality measures, the descriptive analysis of qualitative measures of CGA components, QoL, and the recommended geriatric interventions and their implementation after the three months follow-up. More precisely, feasibility and quality measures include:

the completion rate of CGA prior to MDT;

the attendance rate of a geriatrician during MDT; and

qualitative measures for non-performance of CGA (e.g., absence of geriatricians).

Further endpoints comprise the evaluation of the impact of CGA integration into MDT discussions on primary surgical / oncological care providers, as well as their satisfaction.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software (SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp, Version 31.0, Armonk, NY, USA); calculation of Clopper Pearson Interval was performed with Epitools (

https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/), generation of before-after plots with R (version 4.5.2), using the packages "readxl", "dplyr", "tidyr", "ggplot2", "rlang" and "ggtext".

Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and relative frequencies (%). Continuous and ordinal variables were summarized as median values and ranges (minimum-maximum) for non-normally distributed data and small sample size. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution, and the Pearson chi-squared test for categorical variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Qualitative interviews were transcribed verbally and analyzed with MAXQDA (VERBI Software; Consult Sozialforschung GmbH, Version MAXQDA 24 (Release 24.11.0), Berlin, Germany). All interview transcripts were coded by RSM according to Kuckartz’s steps of content analysis [

26]. Initially, the transcripts were coded separately, progressing from defined passages to more abstract coding levels, including emerging topics. The codes were subsequently discussed with NRN, and finally with FMV, NRN, and RSM. No discrepancies remained. Quotations were translated and backtranslated using DeepL to ensure linguistic accuracy.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment and Feasibility Measures

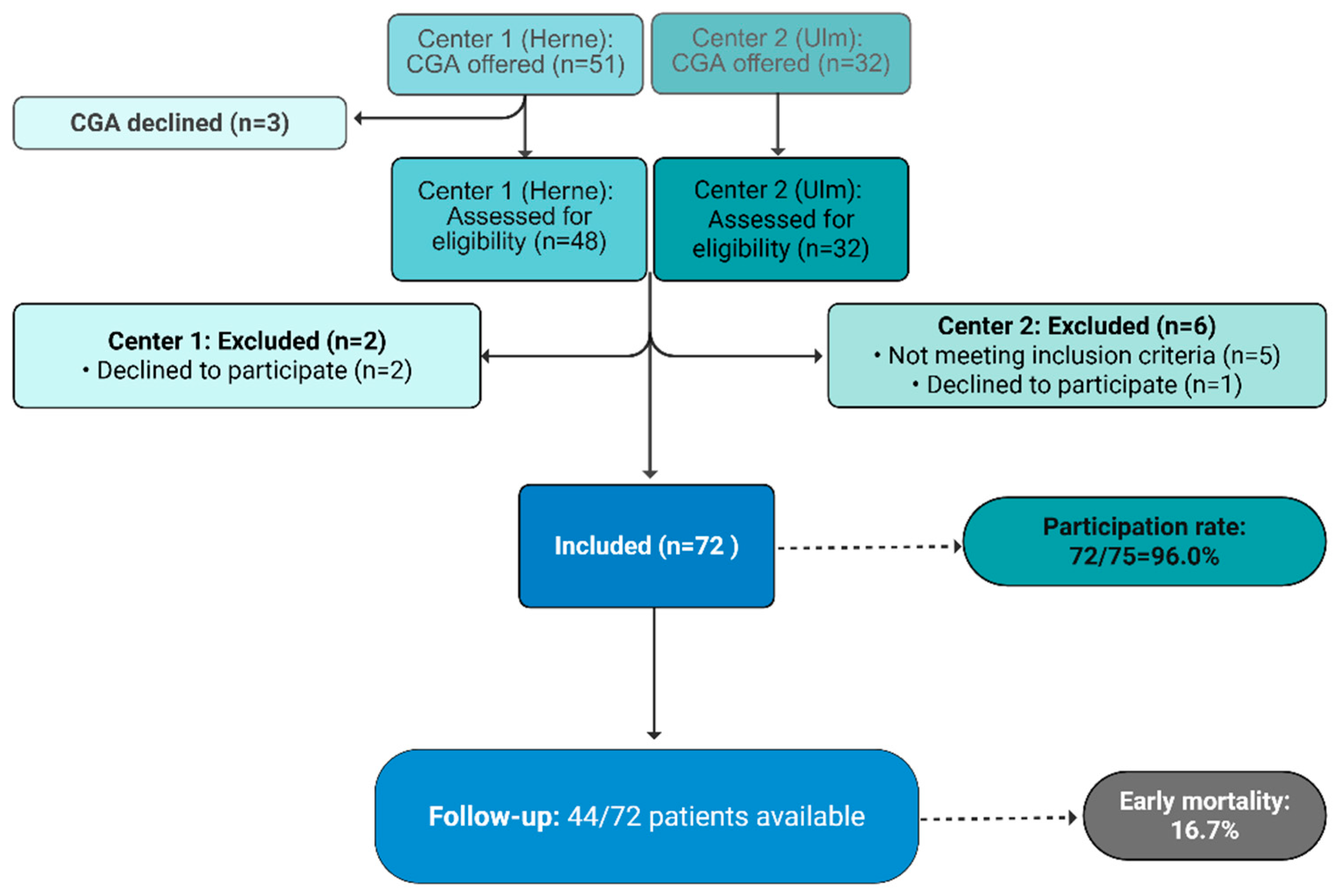

Recruitment time was between February 12, and September 09, 2025 (study center 1, Herne) and between January 24, and June 23, 2025 (study center 2, Ulm). Within this time, CGA was offered to 83 patients as routine measure which was declined by three patients. Of 80 patients receiving CGA, three declined trial participation. In further five patients, cancer diagnosis or progression was not confirmed. Overall, 72 patients were included, corresponding to a real participation rate of 96 % (72/75; 95% CI [0.8875; 0.9917]). As compared with the point estimator, the upper and lower border of the CI are both < ±7.5%. Thus, the primary endpoint, to estimate the willingness to participate with an accuracy of ±7.5%, was reached.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram.

3.2. Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. In brief, the median age of the total study population was 76.7 years (range: 69.1 to 92.1 years). The total percentage of patients ≥ 80 years was 38.9% (28/72). 62.5% of patients were female with 100% females at center 2 as the recruitment was restricted to the gynecology department. In line, cancer entities differed significantly (see

Table 1). The most frequent malignancies at center 1 were bladder, lung, and colorectal cancers, whereas at center 2 patients with cancer of the breast, vagina/vulva, and ovaries were included.

Curative treatment was intended in 45.8% (n=33), whereas a palliative approach was more common (54.2%, n=39). There was a significant difference regarding treatment intention between both centers. At study center 1, 67.4% of patients (n=31) were intended to receive palliative treatment, whereas at study center 2, only 30.8% (n=8) were considered to undergo palliative treatment.

3.3. Results of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

CGA results are depicted in

Table 2. In summary, 45.8% of the cohort scored between one and three points on the CFS, indicating that they functioned well prior to their cancer diagnosis. Further 48.6% scored 4-6 points, corresponding from vulnerable to moderately frail, while 5.6% scored higher, displaying severe frailty. Regarding nutrition, 29.2% were positively screened for malnutrition with the MNA-SF, and 37.5% were at least at risk for malnutrition. 58.3% scored below 9 points in the SPPB, indicating sarcopenia with severe sarcopenia-associated functional deficits. 37.5% had a positive screening for depression, and 70.8% had an impaired test result for cognition.

Patients from center 1 were primarily recruited as inpatients, whereas study center 2 enrolled outpatients. Significant differences regarding patients’ deficits between both study centers were observed. This distinction is mostly evident in the CFS: Most patients at center 2 (84.6%) scored between 1-3 points which indicated relative independence prior to their diagnosis. In contrast, 67.4% of patients at center 1 showed mild to moderate frailty, and 8.7% were severely frail. In line, 50% of patients at center 1 were unable to rise from a chair or required more than one minute to complete five chair stands as compared to only 15.4% at center 2. A similar divergence is shown in cognition; 91.3% of patients (n=42) at center 1 and 34.6% of patients (n=9) at center 2 scored 26 points or less in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and 28.3% of patients at center 1 scored even below 20 points as compared to only 7.7% at center 2.

Assessment of medication besides cancer drugs and/or supportive care medication revealed 76.4% of patients (n=55) with more than 3 and 58.3% (n=42) with more than 5 drugs. 21/66 patients (for whom the complete medication record was available) received direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), 17/66 patients were being treated with aspirin, and 2/66 patients were prescribed phenprocoumon (the most frequently used vitamin K antagonist in Germany, similar to warfarin). Three of these patients were identified as taking a combination therapy of DOAC and aspirin concurrently. For 18.1% of these patients, a chemotherapy with the potential risk for treatment-related thrombocytopenia was recommended while their active treatment with DOAC, aspirin, or phenprocoumon could potentially increase the risk for bleeding to a greater degree.

Geriatric interventions that were recommended based on the identified deficits and included physiotherapy and occupational therapy, modification of the medication, modified management of comorbidities, rehabilitation after certain treatment procedures, evaluation of dysphagia, social support, and cognitive training.

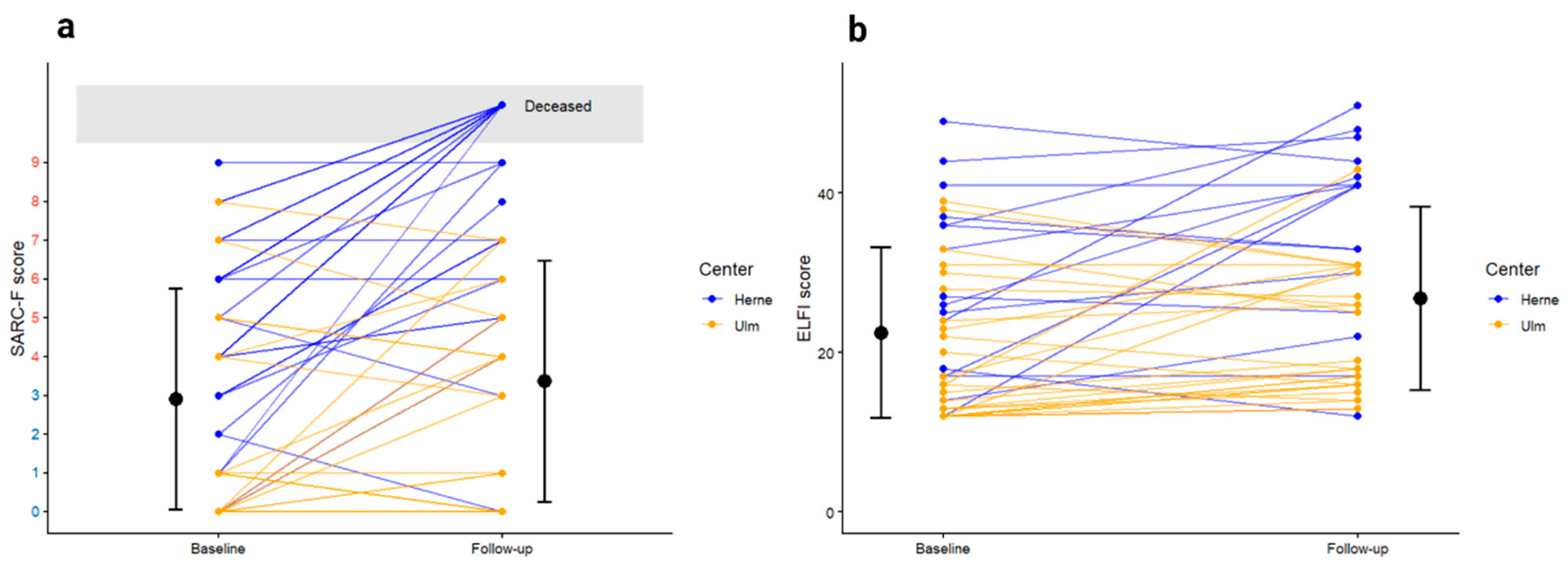

3.4. Functional Trajectories

Follow-up data after three months was available for 44 patients (61.1%). Twelve patients died within the first three months (16.7%), eight patients were documented as being alive in the electronic medical records but could not be reached for telephone follow up, and for another eight patients, the final status remained unknown. Of those, two patients were discharged from hospital to hospice care due to their high symptom burden and their limited life expectancy. Even though we lack their follow-up, we expect that they also died within the three month follow-up.

With regard to early mortality, it has to be noted that none of the patients from center 2 died. In contrast, early mortality for patients at center 1 was 26.1% (n=12). One of these patients received treatment in curative intention and one patient received best supportive care. All patients who deceased had a baseline CFS of 4-6 points. In addition to CGA, 10/46 patients at center 1 received a palliative care consultation. Patients who deceased early received such a consultation in 50% (6/12 cases).

Functional trajectories including SARC-F and The Elderly Functional Index (ELFI) scores over time are depicted in

Figure 2.

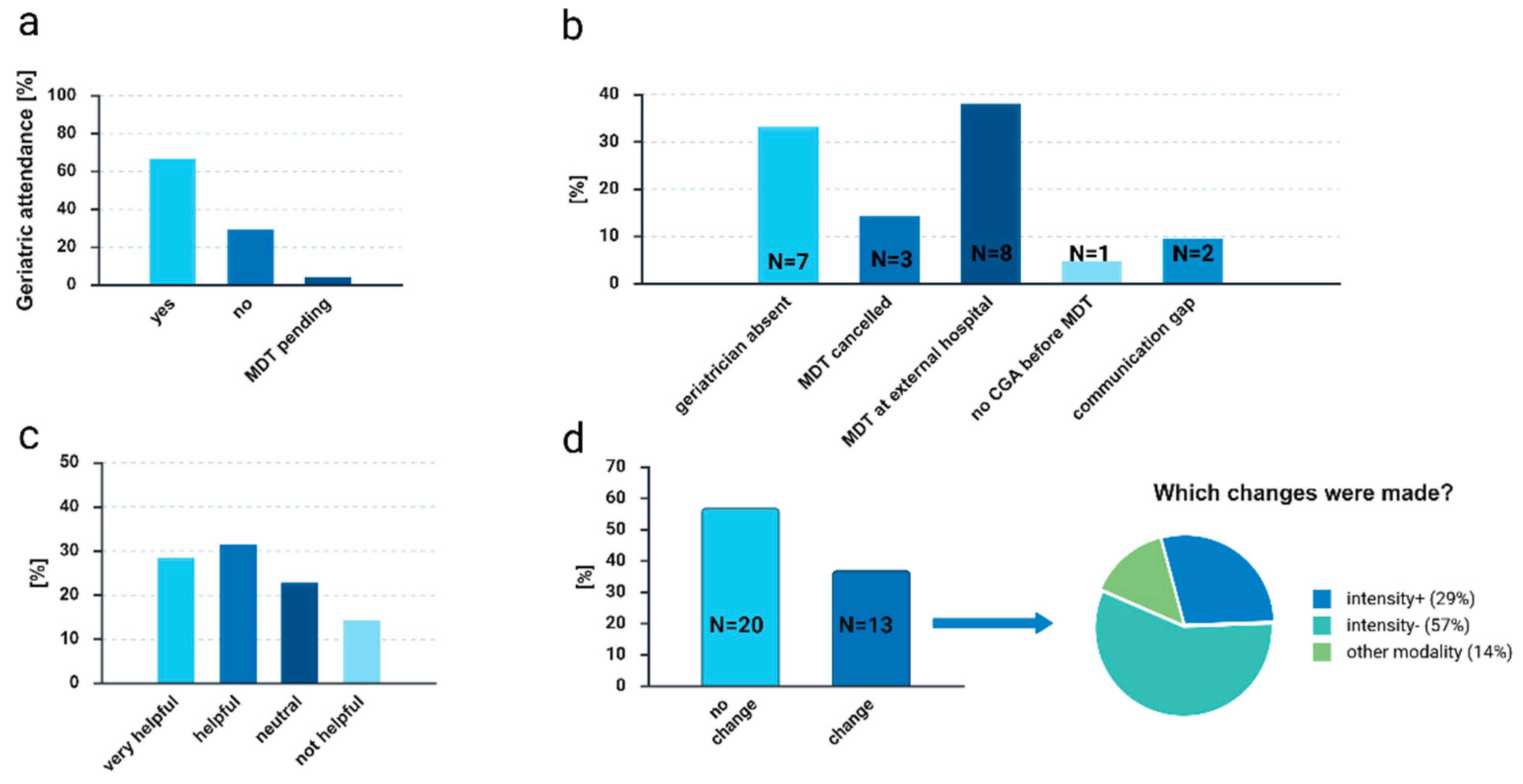

3.5. Implementation of CGA Results into MDT Presentations

3.5.1. Feasibility of Geriatric MDT Presence

In total, two-thirds of MDTs were attended by geriatric team members (

Figure 3(a)). At center 1, 52.2% of MDTs and at center 2, 92.3% were attended. Of note, at study center 1, only one geriatric team member was available to participate in the MDTs due to structural reasons, at study center 2, four members were available. Reasons for a patient not being discussed at the MDT or for non-attendance of a geriatric team member are depicted in

Figure 3 (b). In 38.1%, the reason not to present the patient case and CGA results at the MDT was that the patient case had already been discussed at an MDT of another hospital before but without a detailed treatment recommendation. As this was usually not known at the time at study inclusion, it did not influence trial participation. For detailed treatment recommendations, these cases were usually discussed between two primary care providers (radiation oncologist, surgeon, medical oncologist) together with the geriatric team member under consideration of CGA results (informal “mini MDT”).

3.5.2. Quantitative Evaluation of CGA Implementation

After each patient discussion for whom CGA was presented at MDTs, the primary care providers in charge received an evaluation form. 35 evaluations were available for analysis. Questionnaires were completed by gynecologists (51.4%), radiation oncologists (14.3%), medical oncologists (20%), pulmonologists (11.4%), and palliative care specialists (2.9%). 11.4% of those had professional experience of less than 6 years (residents in training), 34.3% between five and ten years, 40% eleven to 20 years, and 14.3% more than 20 years of experience. 60% of primary care providers rated CGA implementation as helpful or very helpful (

Figure 3(c)). In addition, they stated that CGA led to a modification of treatment recommendations in 37.1% of cases. Of those, 28.6% were adjusted to a more intensive treatment recommendation, 57.1% to a de-escalation, and in 14.3% to a different treatment modality (

Figure 3 (d)). Whether patients received these recommended treatment approaches was not assessed.

When asked about additional information the primary care providers would have liked to receive, they stated in two cases that they would have been interested in detailed recommendations regarding deprescribing/polypharmacy management. In five cases, recommendations for the cancer treatment itself were inquired. In two cases, additional information to estimate life expectancy besides cancer-related mortality, and a detailed recommendation for the management of comorbidities were requested.

3.5.3. Qualitative Evaluation of CGA Implementation

Four interviews with primary care providers from both study centers working on consultant level were performed after termination of trial recruitment. One gynecologist, one radiation oncologist, one palliative care specialist, and one medical oncologist were interviewed. Two had participated in at least 2-4 MDTs with presented CGAs, two in more than ten MDTs.

All participants found the implementation of CGA useful, though one participant noted that CGA results did not further influence treatment recommendations in very fit or very frail patients as those were already adjusted based on the clinical presentation. Local challenges of CGA implementation as partially discussed in the interviews are not reported here as it might be of interest only for site-specific management. All but one participant identified mobility, cognition, and social circumstances as the most informative domains of the geriatric assessment. One participant underlined the importance of integrating patient priorities into the recommendations and pinpointed that this aspect is not routinely listed among the CGA results:

“This is a tumor biology conference, not an actual tumor conference where the focus is on the patient's needs. […] – What are the goals? What are the wishes [the patient] wants to achieve? And with this in mind, it is essential to carry out an assessment in addition to what they collect in terms of the patient's physical and psychological functionality or mental capacity.”

[Interview participant 1]

One participant reported that CGA results led to both escalation and de-escalation of treatment recommendations:

“So this [the CGA; remark] has been groundbreaking in that it has led to more intensive therapy—even with good tolerability—in fit patients who would otherwise have received de-escalation treatments that would have been more palliative in nature. On the other hand, it has also enabled a critical look at alternative treatment concepts, alternative systemic therapy options, and, in selected cases, certainly also relevant therapy de-escalation.”

[Interview participant 3]

Another participant commented on the effect of CGA implementations as follows:

“Much of what is otherwise discussed [without implementation of CGA; remark] remains in the realm of opinion, or of postponing or delaying treatment decisions.”

[Interview participant 2]

4. Discussion

In this prospective bicentric feasibility trial we evaluated the feasibility to integrate CGA into the routine care of older adults with cancer according to the German Guideline on CGA. The guideline recommends CGA prior to systemic cancer treatment for all patients ≥70 years and for those aged 65-69 years with a G8 score ≤14 points. Most of the patients had an indication for CGA based on age ≥70 years, only two patients entered CGA algorithm due to age <70 years and a G8 score ≤14 points. CGA was timely delivered in most cases. In only one case, CGA could not be performed prior to the scheduled MDT meeting. A geriatric team member was present in two-thirds of the MDT meetings which was mostly appreciated by the primary care providers. Of note, MDT presence differed significantly between both centers. At center 1, due to structural reasons, only one geriatric team member was available to attend these meetings compared to a team of four at center 2. We conclude that such an approach requires more than one geriatric team member to compensate for absences.

Older adults are underrepresented in many clinical trials [

27]. Reasons for underrepresentation of older adults are multifaceted. A recent systematic review identified barriers including strict eligibility criteria (e.g., age limitation, and comorbidities), provider barriers (concern for age or toxicity), patient barriers (patient’s own belief that they are too old to participate), and caregiver factors [

28]. These challenges are not limited to trials on cancer-targeting agents but also extend to other interventional trials. A recent report compared the degree of frailty in patients referred to an oncogeriatric outpatient service to patients from the Canadian 5C Randomized Controlled Trial that investigated the effect of CGA on QoL in older cancer patients. Trial participants were significantly younger and had less comorbidities, better physical function, nutritional status, and cognition [

29]. This demonstrates that even trials dedicated to frail older adults are often not representative of this vulnerable group of patients which limits the extent to which the results can be generalized. We observed significant differences in terms of frailty and other patient characteristics between both centers which were likely related to the different settings. Study center 1 recruited mainly inpatients and study center 2 outpatients. Of note, patient characteristics were not adjusted to multiple testing as most of the parameters interact with and depend on frailty. Therefore, statistical significance besides frailty needs to be taken with great caution. In addition, we excluded patients unable to give consent due to overt dementia. Thus, a potential selection bias cannot be excluded but seems to be unlikely given the high percentage of cognitive deficits, especially at center 1.

As a cost-effectiveness trial that aims to legitimize the costs for CGA on a population-wide level must be representative of the general population, we prioritized the estimation of willingness to participate by exactly this difficult-to-recruit population to design such a trial. The participation rate was remarkably high with 96% of patients willing to participate. A hypothesis for this high participation rate is that the time spent with and the interest in the patient from the study personnel while conducting CGA as routine measure prior to informed consent has built trust with the patients and alleviated concerns regarding the formalities of the informed consent process. If this is confirmed in other trials, performance of CGA before consenting and randomization could be a valid option in trials using CGA to tailor treatment intensities and other procedures.

Integrating CGA results into the MDT meetings changed treatment recommendations in 37.1% of the cases. Of note, although the recommendation was changed towards a less intensive treatment approach in the majority (57%) of cases, a more intensive approach was chosen in 29%. This is in line with a comment by one of the interviewed primary care providers who stated that the integration of CGA influenced treatment decisions bidirectionally: it supported escalation to more intensive therapy in fit patients who might otherwise have received less intensive approaches, while also prompting critical reassessment and de-escalation in cases where vulnerabilities were identified. Under- and overtreatment are equally problematic in geriatric oncology as both extremes can negatively impact survival [

30]. Thus, a thorough assessment of the patient’s intrinsic capacity by CGA can help guiding the primary care providers to critically reassess their treatment recommendations. The magnitude of changes observed are in line with a recent systematic review describing a change in treatment recommendations based on CGA results in 31% (range 6–56%), mainly towards a less intensive approach (median 73% of changes) [

31]. Another analysis demonstrated that patients who were discussed at an MDT dedicated to geriatric oncology with the respective integration of CGA resulted in 74% of treatment recommendations that matched with the finally perceived treatment [

32]. Importantly, in our trial, the observed changes refer to MDT recommendations rather than confirmed changes in the actually delivered treatment, which represents an important limitation of this feasibility study. Since many patients received treatments outside the respective centers, we are not aware of the treatments received and cannot compare those. Nevertheless, modification of MDT recommendations represents a proximal and clinically meaningful implementation outcome, reflecting integration of CGA into decision-making processes.

The role of a geriatric team member in the MDT is not yet defined. Primary care providers expressed an explicit desire for specific recommendations regarding the cancer treatment regimen and intensity in five cases. Given that most geriatricians are not trained in oncological sub-specialties, this statement is surprising at first glance. One possible interpretation could be a need for better evidence of dosing and therapy modifications tailored by CGA results. Very few clinical trials have evaluated different treatment regimens or dosages adapted to frailty and CGA in a randomized way. One of the few examples is the Frailty-adjusted therapy in Transplant Non-Eligible patients with newly diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (FiTNEss) trial [

33]. Similar trial concepts should be evaluated for other malignancies, which represents one of our main challenges in the upcoming years. A real integration with a short discussion of both, the cancer and the geriatric specialist would probably be a preferred, yet personally demanding approach.

Regarding the comparatively high mortality rate at Center 1 and the corresponding CGA-identified deficits, early CGA may help stratify patients at risk or with substantial tumor burden and individualize treatment intensity and provide a structured trigger for early integrated supportive and specialist palliative care referral. A recent call for oncogeriatric palliative care emphasize that screening/assessment at diagnosis can stratify and objectivize functional reserve, distinguish tumor-driven from pre-existing frailty, and identify candidates for best supportive care strategies to avoid overtreatment and avoidable treatment-related toxicity, as well as financial and time burden; early palliative review and targeted symptom management may further optimize patients prior to treatment and reduce treatment-related harm [

34]. In line with this, our interviews suggested that CGA supports more timely MDT decisions. Despite that, integration of patient priorities besides objective results of the geriatric assessment were requested during one interview and may help earlier transitions to best supportive care pathways when appropriate or highlight treatment alternatives aiming solely at control of cancer-related symptoms to improve quality of life.

Nonetheless, this trial has some limitations. Firstly, we did not assess toxicities as the main outcome measure, which were improved in previous randomized trials. As the focus was on feasibility, the study cohort was very heterogenous, limiting comparability regarding efficacy. Secondly, trial inclusion relied on referral by the physician in charge rather than a standardized screening of all older cancer patients treated at the respective departments, potentially causing a selection bias towards patients with higher degrees of frailty, at least at center 1. This was also noted by one of the interviewed primary care providers: „From my point of view, it's less about specific factors and more about [CGA; remark] being implemented in principle. In other words, the systematic nature of the implementation and the avoidance of bias by giving preference to certain patients for screening.“ For further implementation in routine care, standardized screening should be implemented to minimize possible bias and to enable all patients to receive specialized oncogeriatric care.

5. Conclusions

The integration of CGA into the routine care of older adults with cancer is feasible if appropriate personnel is available. A subsequent trial on cost-effectiveness is required to foster further implementation of CGA in the German healthcare system. In addition, future implementation studies should not only assess functional domains but also systematically integrate patient priorities and goals of care into CGA-guided MDT discussions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.M., F.M.V., M.D., R.W., N.R.N.; data acquisition, R.S.M., Me.D., N.R.N.; methodology, R.S.M., S.F., M.D., F.M.V., N.R.N.; formal analysis, N.R.N.; R.S.M., F.M.V; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.M., N.R.N.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, S.H., R.W., M.D.; project administration, R.S.M., Me.D., F.M.V., N.R.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Ulm on October 30, 2024 (351/24 – FSt/Sta), and by the IRB of Westphalia-Lippe on January 23, 2025 (2024-700-f-S). The study is registered at German Clinical Trials Register (Deutsches Register für klinische Studien, DRKS), DRKS00035569.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided at reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all our patients for participation and Gabi Müller for her support with data aquisition. The figures were created with BioRender.com The study concept was in part presented at the 2025 DGG Congress “Geriatrie – Gefragt, Gereift, Gestärkt”, held from September 18-20 in Weimar, Germany, as well as at the SIOG 2025 annual conference “Bridging Research and Clinical Practice in Geriatric Oncology”, held from November 20-22 in Ghent, Belgium.

Conflicts of Interest

NRN has received honoraria and travel support by Janssen-Cilag, Medac, Novartis, Pfizer, Abbvie, and Jazz Pharmaceutical. RW has received honoraria and travel support from Novartis, Nutricia, Heel, and InfectoPharm. ATT has received research funding by Neovii Biotech. Consultancy for CSL Behring, Maat Pharma, Biomarin, Pfizer, and Onkowissen. Travel reimbursements by Neovii and Novartis. MD has received honoraria from Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca which was not related to oncology. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest (RSM, MD, FMV, SH, AA, CG, FR, PH, CB, SF, NW, DS, G, JA, DAB).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADL |

Activities of Daily Living |

| iADL |

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| ASCO |

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CGA |

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment |

| CTCAE |

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (formerly Common Toxicity Criteria) |

| DIA-S |

Depression im Alter – Skala (German for: Depression in old age – Scale) |

| DOAC |

Direct Oral Anticoagulants |

| DRKS |

Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien |

| ELFI |

Elderly Functional Index |

| ESMO |

European Society of Oncology |

| G8 |

Geriatric Screening 8 |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| MDT |

Multidisciplinary Team Meeting / Multidisciplinary Tumor Board |

| MMSE |

Mini Mental State Examination |

| MNA-SF |

Mini Nutritional Assessment – short form |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| SARC-F |

Strength, Assistance with walking, Rise from a chair, Climb stairs and Falls |

| SIOG |

Société Internationale d’Oncologie Gériatrique, International Society of Geriatric Oncology |

| SPPB |

Short Physical Performance Battery |

References

- Neuendorff, N.R.; Reinhardt, H.C.; Christofyllakis, K. Is Less Always More? Emerging Treatment Concepts in Geriatric Hemato-Oncology. Ageing and Cancer Research & Treatment 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, C.-L.; Kim, H.; Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Chung, V.; Koczywas, M.; Fakih, M.; Chao, J.; Cabrera Chien, L.; Charles, K.; et al. Geriatric Assessment–Driven Intervention (GAIN) on Chemotherapy-Related Toxic Effects in Older Adults With Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2021, 7, e214158. [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Mohamed, M.R.; Xu, H.; Culakova, E.; Loh, K.P.; Magnuson, A.; Flannery, M.A.; Obrecht, S.; Gilmore, N.; Ramsdale, E.; et al. Evaluation of Geriatric Assessment and Management on the Toxic Effects of Cancer Treatment (GAP70+): A Cluster-Randomised Study. The Lancet 2021, 398, 1894–1904. [CrossRef]

- Soo, W.K.; King, M.T.; Pope, A.; Parente, P.; Dārziņš, P.; Davis, I.D. Integrated Geriatric Assessment and Treatment Effectiveness (INTEGERATE) in Older People with Cancer Starting Systemic Anticancer Treatment in Australia: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised Controlled Trial. The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2022, 3, e617–e627. [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.M.; Vistisen, K.K.; Olsen, A.P.; Bardal, P.; Schultz, M.; Dolin, T.G.; Rønholt, F.; Johansen, J.S.; Nielsen, D.L. The Effect of Geriatric Intervention in Frail Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy for Colorectal Cancer: A Randomised Trial (GERICO). Br J Cancer 2021, 124, 1949–1958. [CrossRef]

- Disalvo, D.; Moth, E.; Soo, W.K.; Garcia, M.V.; Blinman, P.; Steer, C.; Amgarth-Duff, I.; Power, J.; Phillips, J.; Agar, M. The Effect of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment on Care Received, Treatment Completion, Toxicity, Cancer-Related and Geriatric Assessment Outcomes, and Quality of Life for Older Adults Receiving Systemic Anti-Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2023, 14, 101585. [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. JCO 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [CrossRef]

- Loh, K.P.; Liposits, G.; Arora, S.P.; Neuendorff, N.R.; Gomes, F.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Amaral, T.; Mariamidze, E.; Biganzoli, L.; Brain, E.; et al. Adequate Assessment Yields Appropriate Care—the Role of Geriatric Assessment and Management in Older Adults with Cancer: A Position Paper from the ESMO/SIOG Cancer in the Elderly Working Group. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103657. [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geriatrie e.V. (DGG) S3-Leitlinie „Umfassendes Geriatrisches Assessment (Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, CGA) Bei Hospitalisierten Patientinnen Und Patienten“. AWMF-Register 2024, Langversion 1.1, 2024.

- Hüttmeyer, M.; Tatschner, K.; Jentschke, E.; Roch, C.; Deschler-Baier, B. Increasing the Evidence for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment – Outlook on Another Work in Progress. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2025, 16, 102078. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, M.K.; Ertl, S.W.; Engelmeyer, P.; Heuer, H.-C.; Christoph, D.C. Impact of Geriatric Assessment on the Tolerability of Combination Chemotherapy in Older Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Matched-Pair Analysis. Oncol Res Treat 2023, 46, 100–105. [CrossRef]

- Mayland, R.S.; Verri, F.M.; Deterding, M.; Heublein, S.; Aslan, A.; Turki, A.T.; Roghmann, F.; Strumberg, D.; Wirth, R.; Denkinger, M.; et al. Integration of Geriatric Assessment – Guided Care Plan Modifications and Interventions into Clinical Paths of Older Adults with Cancer (GORILLA): Study Protocol of a Prospective Cohort Trial.

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J 1965, 14, 61–65.

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. The Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: A Simple Questionnaire to Rapidly Diagnose Sarcopenia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013, 14, 531–532. [CrossRef]

- Drey, M.; Ferrari, U.; Schraml, M.; Kemmler, W.; Schoene, D.; Franke, A.; Freiberger, E.; Kob, R.; Sieber, C. German Version of SARC-F: Translation, Adaption, and Validation. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2020, 21, 747-751.e1. [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association With Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission. Journal of Gerontology 1994, 49, M85–M94. [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases 1987, 40, 373–383. [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R.; Hopkins, J.O.; Klepin, H.D.; Lowenstein, L.M.; Mackenzie, A.; Mohile, S.G.; Somerfield, M.R.; Dale, W. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic Cancer Therapy: ASCO Guideline Questions and Answers. JCO Oncology Practice 2023, 19, 718–723. [CrossRef]

- Heidenblut, S.; Zank, S. Entwicklung eines neuen Depressionsscreenings für den Einsatz in der Geriatrie: Die „Depression-im-Alter-Skala“ (DIA-S). Z Gerontol Geriat 2010, 43, 170–176. [CrossRef]

- Hurria, A.; Li, D.; Hansen, K.; Patil, S.; Gupta, R.; Nelson, C.; Lichtman, S.M.; Tew, W.P.; Hamlin, P.; Zuckerman, E.; et al. Distress in Older Patients With Cancer. JCO 2009, 27, 4346–4351. [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K. A Global Clinical Measure of Fitness and Frailty in Elderly People. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2005, 173, 489–495. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Ramsch, C.; Uter, W.; Guigoz, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Thomas, D.R.; Anthony, P.; Charlton, K.E.; Maggio, M.; et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA®-SF): A Practical Tool for Identification of Nutritional Status. The Journal of nutrition, health and aging 2009, 13, 782–788. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J American Geriatrics Society 2005, 53, 695–699. [CrossRef]

- William Molloy, D.; Standish, T.I.M. A Guide to the Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination. International Psychogeriatrics 1997, 9, 87–94. [CrossRef]

-

Qualitative Datenanalyse: computergestützt: Methodische Hintergründe und Beispiele aus der Forschungspraxis; Kuckartz, U., Dresing, T., Grunenberg, H., Eds.; SpringerLink Bücher; 2., überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, 2007; ISBN 978-3-531-34248-1.

- Habr, D.; McRoy, L.; Papadimitrakopoulou, V.A. Age Is Just a Number: Considerations for Older Adults in Cancer Clinical Trials. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2021, 113, 1460–1464. [CrossRef]

- Sedrak, M.S.; Freedman, R.A.; Cohen, H.J.; Muss, H.B.; Jatoi, A.; Klepin, H.D.; Wildes, T.M.; Le-Rademacher, J.G.; Kimmick, G.G.; Tew, W.P.; et al. Older Adult Participation in Cancer Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Interventions. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2021, 71, 78–92. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.H.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Puts, M. How Representative Are Participants in Geriatric Oncology Clinical Trials? The Case of the 5C RCT in Geriatric Oncology: A Cross-Sectional Comparison to a Geriatric Oncology Clinic. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2024, 15, 101703. [CrossRef]

- DuMontier, C.; Dale, W.; Revette, A.C.; Roberts, J.; Sanyal, A.; Perumal, N.; Blackstone, E.C.; Uno, H.; Whitehead, M.I.; Mustian, L.; et al. Ethics of Overtreatment and Undertreatment in Older Adults with Cancer. BMC Med Ethics 2025, 26, 105. [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, M.; Lund, C.; Te Molder, M.; Soubeyran, P.; Wildiers, H.; Van Huis, L.; Rostoft, S. Geriatric Assessment in the Management of Older Patients with Cancer – A Systematic Review (Update). Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2022, 13, 761–777. [CrossRef]

- Lamy, T.; Pages, A.; Thomas, Z.A.; Chaulet, G.B.; Iacob, M.; Bintein, F.; Lazarovici, C.N.; Baldini, C.; Frelaut, M. Impact of a Dedicated Geriatric Oncology Tumor-Board on Therapeutic Decision-Making in Patients Aged 70 and over with Cancer: The OncoBoardAge Study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2025, 16, 102433. [CrossRef]

- Coulson, A.B.; Royle, K.-L.; Pawlyn, C.; Cairns, D.A.; Hockaday, A.; Bird, J.; Bowcock, S.; Kaiser, M.; De Tute, R.; Rabin, N.; et al. F Railty-Adjusted Therapy i n T Ransplant N on- E Ligible Patient s with Newly Diagno s Ed Multiple Myeloma (FiTNEss (UK-MRA Myeloma XIV Trial)): A Study Protocol for a Randomised Phase III Trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056147. [CrossRef]

- Liposits, G.; Baxter, M.A.; Brown-Kerr, A.; O’Hanlon, S. Personalized Palliative Care for Older Adults with Cancer: A Call for Action on Oncogeriatric Palliative Care. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2025, 16, 102339. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).