Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

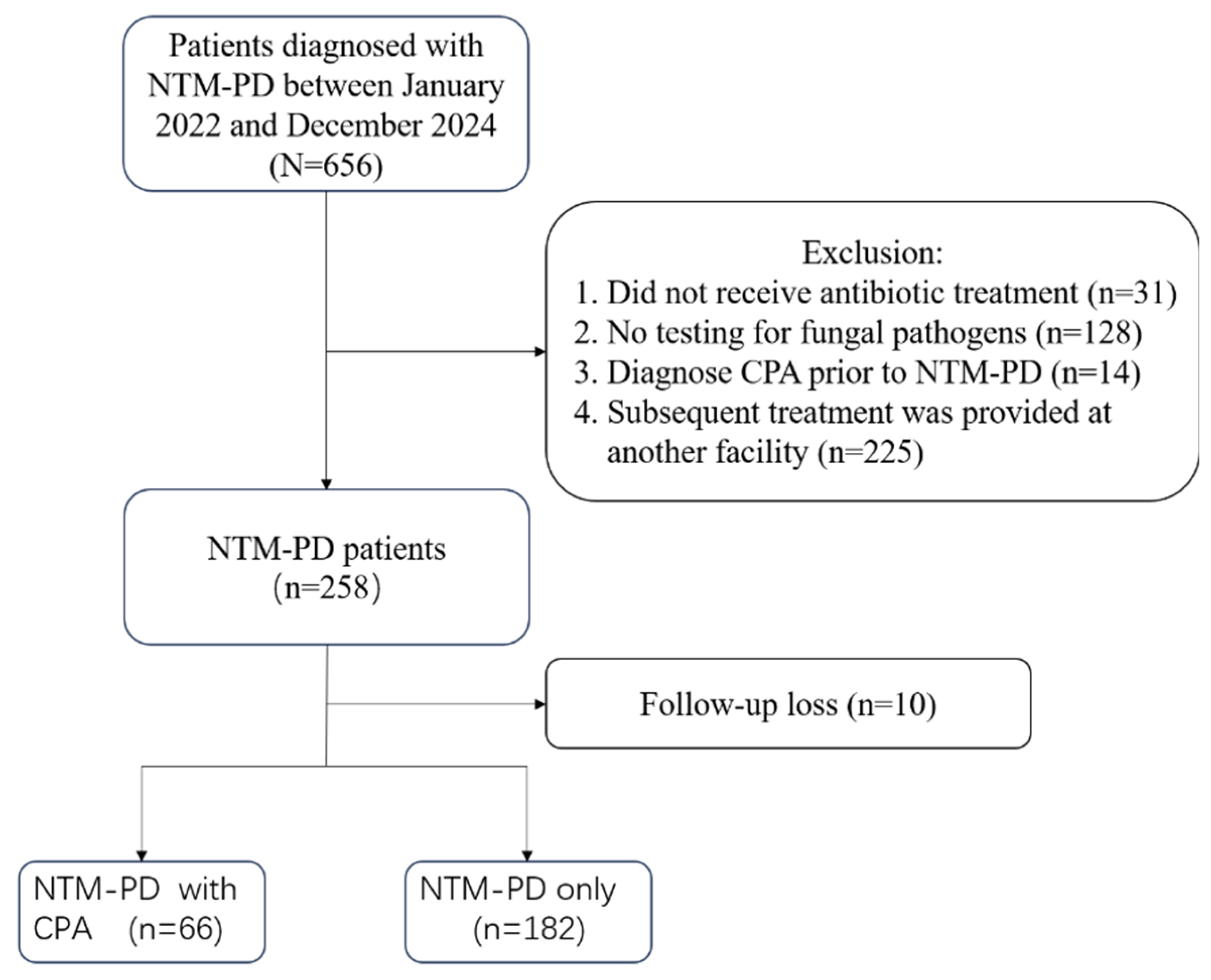

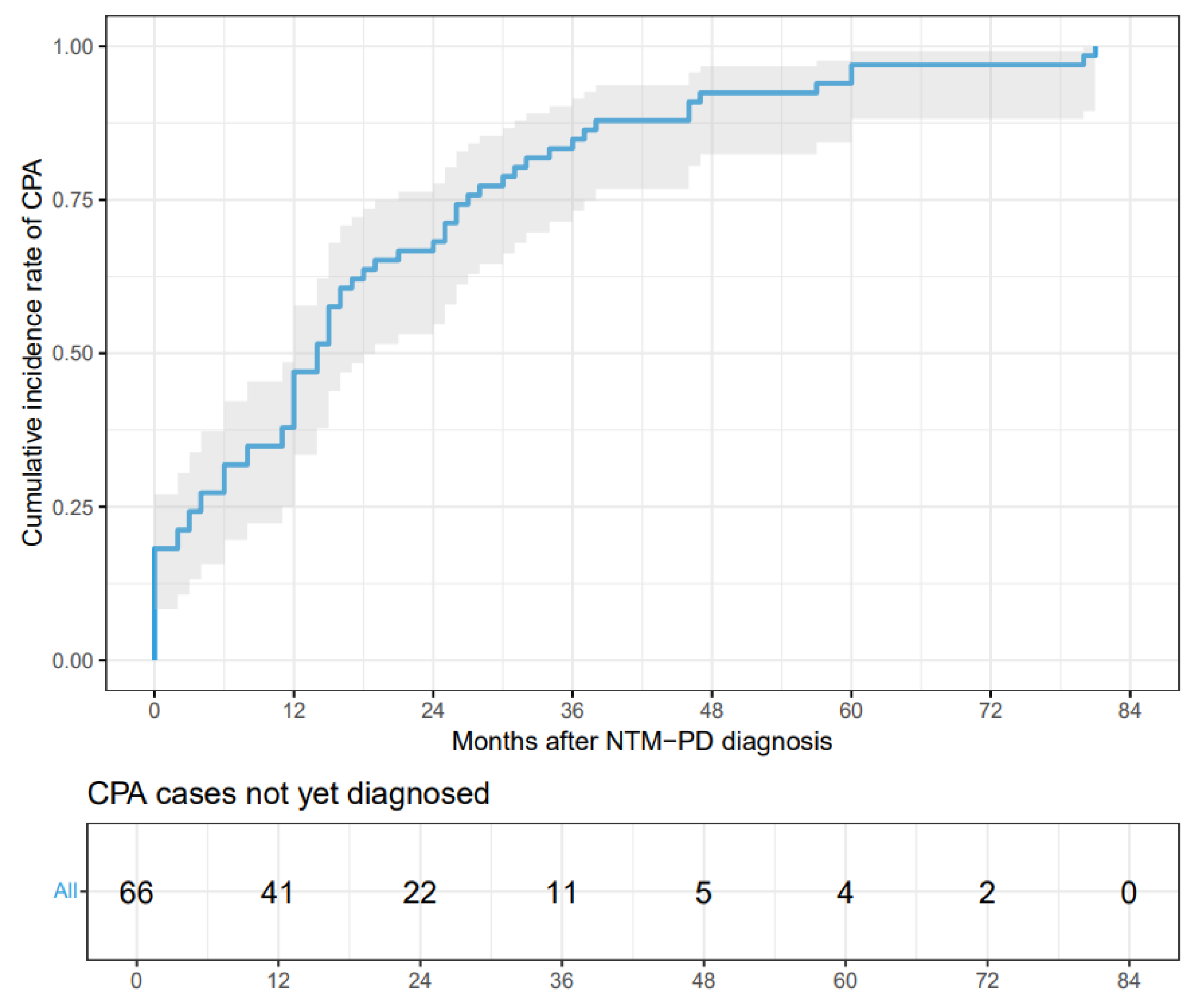

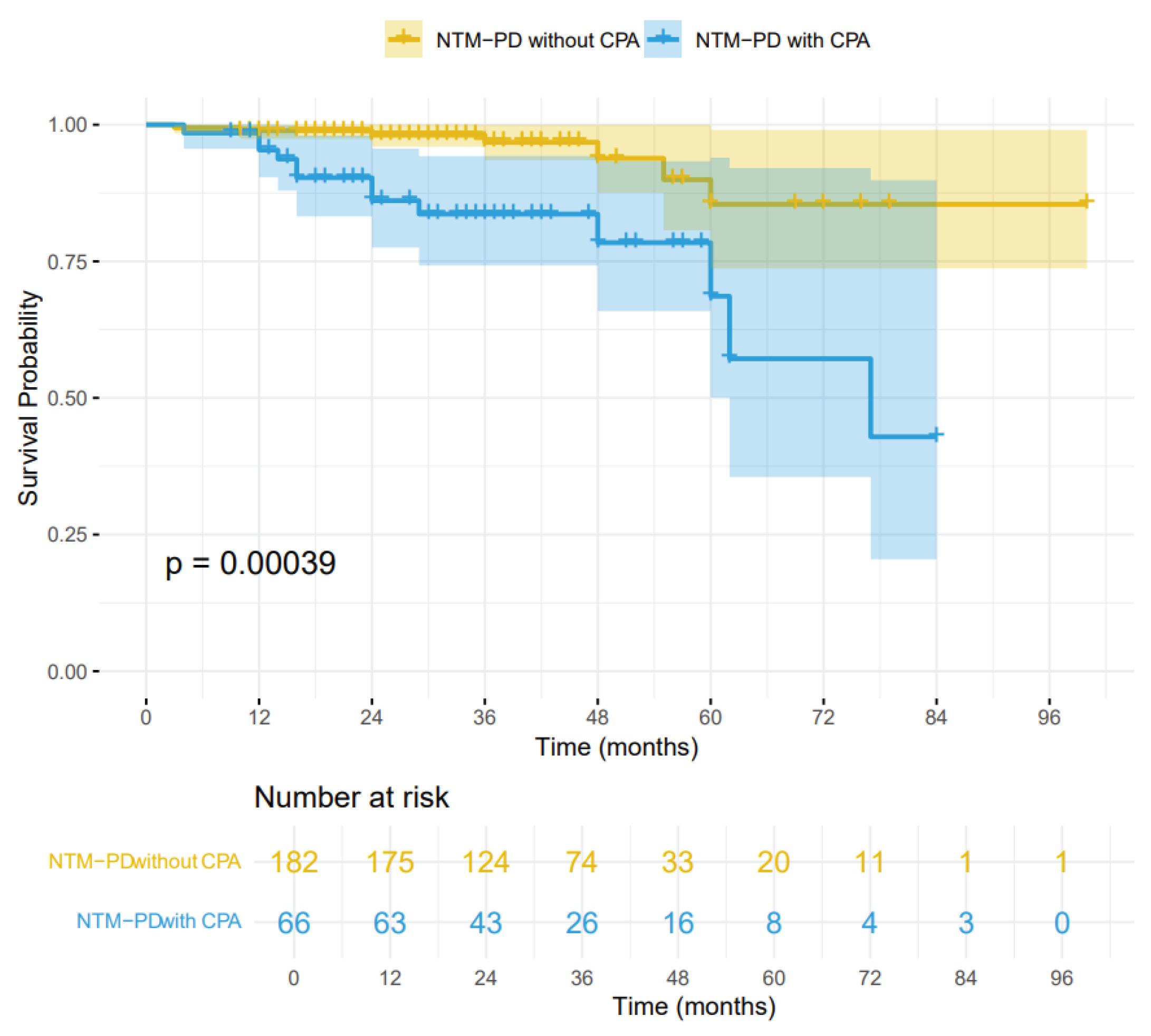

Background: The incidence of patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) complicated by chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) has been increasing. CPA is known to be associated with complex treatment regimens and a poor prognosis. However, data from mainland China remain scarce. Objective: This single-center retrospective study aimed to evaluate the clinical characteristics, risk factors, and prognoses of patients with NTM-PD who were coinfected with CPA. Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 248 patients diagnosed with NTM-PD. Risk factors for CPA were analyzed via multiple logistic regression, followed by survival analysis. Results: Among the 248 patients with NTM-PD, 66 (26.6%) were diagnosed with CPA. Independent risk factors for NTM-PD and CPA coinfection included male sex(OR 2.13, 95% CI:1.03-4.47), dyspnea(OR 27.9, 95% CI:4.24-570), cavity(OR 5.95, 95% CI:2.76-13.9), use of oral corticosteroids(OR 4.28, 95% CI:1.13-16.6), and interstitial lung disease(OR 15.5, 95% CI:1.89-361). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated a significant divergence between the NTM-PD group and the NTM-PD with CPA group (log-rank test, p = 0.00039; HR 2.01, 95% CI:0.66-6.12). Conclusion: In patients with NTM-PD, the presence of concurrent CPA is associated with a marked increase in mortality. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for CPA to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment, particularly in high-risk individuals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Patients

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Diagnosis of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Risk Factors for Aspergillus Coinfection

3.3. Survival Analysis for All-Cause Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, N.; Li, L.; Wu, S. Epidemiology and laboratory detection of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yan, X.; Liu, F.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Bao, X.; Pan, J.; Luo, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease and associated risk factors in China: A prospective surveillance study. J Infect 2021, 83, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, M.J.; Ebrahimi, G.; Arefzadeh, S.; Zamani, S.; Nikpor, Z.; Mirsaeidi, M. Antibiotic therapy success rate in pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2020, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.P.; Chen, S.H.; Lou, H.; Gui, X.W.; Shen, X.N.; Cao, J.; Sha, W.; Sun, Q. Factors Associated with Treatment Outcome in Patients with Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease: A Large Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Shanghai. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.P.; Zhang, Q.; Lou, H.; Shen, X.N.; Qu, Q.R.; Cao, J.; Wei, W.; Sha, W.; Sun, Q. Effectiveness and safety of regimens containing linezolid for treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary Disease. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2023, 22, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoompoung, P.; Chayakulkeeree, M. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Following Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections: An Emerging Disease. J Fungi (Basel) 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, F. Post-tuberculosis chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: An emerging public health concern. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhun, B.W.; Jung, W.J.; Hwang, N.Y.; Park, H.Y.; Jeon, K.; Kang, E.S.; Koh, W.J. Risk factors for the development of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0188716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Imamura, Y.; Takazono, T.; Yoshida, M.; Ide, S.; Hirano, K.; Tashiro, M.; Saijo, T.; Kosai, K.; Morinaga, Y.; et al. The risk factors for developing of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in nontuberculous mycobacteria patients and clinical characteristics and outcomes in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis patients coinfected with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Med Mycol 2016, 54, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuuchi, K.; Ito, A.; Hashimoto, T.; Kumagai, S.; Ishida, T. Risk stratification for the development of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. J Infect Chemother 2018, 24, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Ide, S.; Takazono, T.; Takeda, K.; Iwanaga, N.; Yoshida, M.; Hosogaya, N.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Irifune, S.; Suyama, T.; et al. Risk Factors and Long-Term Prognosis for Coinfection of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease and Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: A Multicentre Observational Study in Japan. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, I.S.; Soundappan, K.; Agarwal, R.; Muthu, V.; Dhooria, S.; Prasad, K.T.; Salzer, H.J.F.; Cornely, O.A.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Chakrabarti, A. Prevalence of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Patients With Mycobacterial and Non-Mycobacterial Tuberculosis Infection of the Lung: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, C.L.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lange, C.; Cambau, E.; Wallace, R.J., Jr.; Andrejak, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Brozek, J.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur Respir J 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuck, A.E.; Minder, C.E.; Frey, F.J. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis 1989, 11, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noni, M.; Katelari, A.; Dimopoulos, G.; Kourlaba, G.; Spoulou, V.; Alexandrou-Athanassoulis, H.; Doudounakis, S.E.; Tzoumaka-Bakoula, C. Inhaled corticosteroids and Aspergillus fumigatus isolation in cystic fibrosis. Med Mycol 2014, 52, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; Page, I.D.; Chakaya, J.; Jabeen, K.; Jude, C.M.; Cornet, M.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Bongomin, F.; Bowyer, P.; Chakrabarti, A.; et al. Case Definition of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Resource-Constrained Settings. Emerg Infect Dis 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; Cadranel, J.; Beigelman-Aubry, C.; Ader, F.; Chakrabarti, A.; Blot, S.; Ullmann, A.J.; Dimopoulos, G.; Lange, C. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J 2016, 47, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Kurahara, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Ikegami, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Minomo, S.; Tachibana, K.; Tsuyuguchi, K.; Hayashi, S.; Suzuki, K. Prognosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease. Respir Investig 2018, 56, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takazono, T.; Ide, S.; Adomi, M.; Ogata, Y.; Saito, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Takeda, K.; Iwanaga, N.; Hosogaya, N.; Sakamoto, N.; et al. Risk Factors and Prognostic Effects of Aspergillosis as a Complication of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease: A Nested Case-Control Study. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Furuuchi, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Nakamoto, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishii, H.; Yoshiyama, T.; Yoshimori, K.; Takizawa, H.; Sasaki, Y.; et al. Impact of Aspergillus precipitating antibody test results on clinical outcomes of patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Respir Med 2020, 166, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Hart, S.; Lande, L. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Lung Disease (NTM-LD): Current Recommendations on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Patient Management. Int J Gen Med 2022, 15, 7619–7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosaki, F.; Bando, M.; Nakayama, M.; Mato, N.; Nakaya, T.; Yamasawa, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Fukushima, N.; Sugiyama, Y. Clinical features of pulmonary aspergillosis associated with interstitial pneumonia. Intern Med 2014, 53, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzer, H.J.F.; Reimann, M.; Oertel, C.; Davidsen, J.R.; Laursen, C.B.; Van Braeckel, E.; Agarwal, R.; Avsar, K.; Munteanu, O.; Irfan, M.; et al. Aspergillus-specific IgG antibodies for diagnosing chronic pulmonary aspergillosis compared to the reference standard. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023, 29, 1605.e1601–1605.e1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Z.; Chen, S.F.; Mei, C.L.; Cao, T.Z.; Feng, W.; Liu, X.P.; Xu, W.J.; Du, R.H. Clinical characteristics of 220 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis complicated with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Chin J Antituberc. 2024, 46(7), 770–777. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Total (N=248) |

NTM-CPA group (n=66) |

NTM group (n=182) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) >60 |

60 (51.25,69) 118 (47.6%) |

63 (57,71) 39 (59.1%) |

58 (51,68) 79 (43.4%) |

0.0078 0.0317 |

| Sex(male) | 103 (41.5%) | 44 (66.7%) | 59 (32.4%) | <0.001 |

| BMI(kg/m^2) <18.5 n=243 |

19.83 (17.11,21.97) 89 (36.6%) |

18.87(16.22,22.03) 31 (49.2%) |

20.02(17.58,21.91) 58 (32.2%) |

0.0537 0.0439 |

| Smoking | 57 (23.0%) | 28 (42.4%) | 29 (15.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Drinking | 25 (10.1%) | 11 (16.7%) | 14 (7.7%) | 0.0541 |

| Pulmonary comorbidities | ||||

| Tuberculosis | 76 (30.6%) | 24 (36.4%) | 52 (28.6%) | 0.2758 |

| COPD | 45 (18.1%) | 18 (27.3%) | 27 (14.8%) | 0.0389 |

| Asthma | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.1737 |

| Lung tumor | 9 (3.6%) | 2 (3.0%) | 7 (3.8%) | 1 |

| Interstitial Lung Disease | 7 (2.8%) | 6 (9.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.0016 |

| Pneumoconiosis | 7 (2.8%) | 2 (3.0%) | 5 (2.7%) | 1 |

| Extrapulmonary comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (8.9%) | 10 (15.2%) | 12 (6.6%) | 0.0446 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 43 (17.3%) | 15 (22.7%) | 28 (15.4%) | 0.213 |

| Endocrine system disease | 11 (4.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | 10 (5.5%) | 0.191 |

| Digestive system disease | 20 (8.1%) | 9 (13.6%) | 11 (6.0%) | 0.076 |

| Rheumatic disease | 21 (8.5%) | 7 (10.6%) | 14 (7.7%) | 0.493 |

| Kidney disease | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | 3 (1.6%) | 1.000 |

| Nervous system disease | 7 (2.8%) | 1 (1.5%) | 6 (3.3%) | 0.681 |

| Other tumors | 16 (6.5%) | 6 (9.1%) | 10 (5.5%) | 0.239 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 6 (2.4%) | 4 (6.06%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.0447 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 13 (5.2%) | 7 (10.61%) | 6 (3.30%) | 0.046 |

| NTM species | 0.0042 | |||

| M.avium complex | 160 (64.5%) | 43 (65.1%) | 117 (64.3%) | |

| M.abscessus complex | 69 (27.8%) | 12 (18.2%) | 57 (31.3%) | |

| Mixed infection | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Others | 17 (6.9%) | 10 (15.2%) | 7 (3.8%) | |

| Radiological features | ||||

| Cavity | 124 (50%) | 55 (83.3%) | 69 (37.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Bronchiectasis | 177 (71.4%) | 44 (66.7%) | 133 (73.1%) | 0.3427 |

| Nodule | 224 (90.3%) | 57 (86.4%) | 167 (91.8%) | 0.2266 |

| Symptom | ||||

| Cough | 213 (85.9%) | 61 (92.4%) | 152 (83.5%) | 0.0979 |

| Dyspnea | 10 (4.0%) | 9 (13.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoptysis | 57 (23.0%) | 20 (30.3%) | 37 (20.3%) | 0.1238 |

| Fever | 50 (20.2%) | 23 (34.8%) | 27 (14.8%) | 0.0011 |

| Weight loss | 51 (20.6%) | 18 (27.3%) | 33 (18.1%) | 0.154 |

| Laboratory Test | ||||

| ALB (g/L) | 38.5(34.9,41.7) | 35.45(32.00,40.10) | 39.35(36.20,41.90) | <0.0001 |

| HB (g/L) (n=247) | 119(108,129) | 115 (100,125) | 121 (111,130) | 0.0059 |

| ESR(mm/h)(n=200) | 23(7.25,52.50) | 47 (27,70) | 15 (7,34) | <0.0001 |

| CRP(mg/L)(n=247) | 5.62(1.12,28.96) | 33.43 (8.71,62.64) | 3.41 (0.88,12.27) | <0.0001 |

| Follow-up Time(m) | 30(20.25,42.00) | 30(18,47) | 30(21,42) | 0.9289 |

| Death | 20 (8.1%) | 13 (19.7%) | 7 (3.8%) | 0.0002 |

| Univariate OR (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age>60 | 1.88 (1.07-3.36) | 0.03 | 1.07 (0.53-2.14) | 0.9 |

| Male | 4.17 (2.32-7.7) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.03-4.47) | 0.041 |

| BMI<18.5 kg/m^2 | 1.95 (1.08-3.53) | 0.038 | ||

| Smoking | 3.89 (2.08-7.33) | <0.001 | ||

| Drinking | 2.40 (1.01-5.59) | 0.047 | ||

| COPD | 2.15 (1.08-4.23) | 0.03 | 0.97 (0.39-2.27) | >0.9 |

| Tuberculosis | 1.43 (0.78-2.58) | 0.2 | ||

| Asthma | 5.66 (0.53-123) | 0.14 | ||

| ILD | 18.1 (3.01-345) | <0.001 | 15.5 (1.89-361) | 0.008 |

| Pneumoconiosis | 1.11 (0.16-5.27) | >0.9 | ||

| Lung cancer | 0.78 (0.11-3.33) | 0.8 | ||

| Cough | 2.41 (0.97-7.32) | 0.060 | ||

| Dyspnea | 28.6 (5.21-533) | <0.001 | 27.9 (4.24-570) | <0.001 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.70 (0.89-3.20) | 0.11 | ||

| Fever | 3.07 (1.60-5.90) | <0.001 | ||

| Weight loss | 1.69 (0.86-3.25) | 0.12 | ||

| Bronchiectasis | 0.74 (0.40-1.37) | 0.3 | ||

| Cavity | 8.19 (4.15-17.5) | <0.001 | 5.95 (2.76-13.9) | <0.001 |

| Nodule | 0.57 (0.24-1.42) | 0.2 | ||

| Diabetes | 2.53 (1.02-6.18) | 0.046 | ||

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 5.81 (1.11-42.6) | 0.038 | ||

| Oral corticosteroids | 3.48 (1.11-11.2) | 0.032 | 4.28 (1.13-16.6) | 0.032 |

| ALB | 0.88 (0.83-0.94) | <0.001 | ||

| HB | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | 0.004 | ||

| ESR | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | <0.001 | ||

| CRP | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | <0.001 | ||

| NTM species | 0.4 | |||

| M.avium complex | Reference | |||

| M.abscessus complex | 0.57 (0.27-1.14) | |||

| Mixed | 2.72 (0.11-69.8) | |||

| Others | 1.17 (0.24-4.40) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).