1. Introduction

Pulmonary aspergillosis is the most common fungal lung disease. Clinical presentation depends on host factors and the immune response. They range from milder forms, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), to more severe and lethal forms, such as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA). An intermediate spectrum is chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA). It is characterized by slowly progressive destruction of the lung parenchyma in patients with a history of structural lung disease, often with residual cavities, bullae, or scarring. The primary driver of disease in patients with CPA is the local immune response to Aspergillus colonization of previously damaged lung tissue. However, the immune response determines the clinical presentation. There are different subtypes: chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA), chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA), subacute invasive aspergillosis (SAIA), formally called chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis (CNPA), simple aspergilloma (SA) and aspergillotic nodules. In practice, CPA clinical syndromes and their radiology often overlap, and patients can transition from one form of CPA to another as their disease evolves over time(Garg et al., 2023; Kanj et al., 2018). Diagnostic methods are usually based on clinical presentation, radiological changes and microbiological evidence(Denning et al., 2016). The number of CPA cases worldwide has been estimated at 3 million(Zarif et al., 2021), although the prevalence varies substantially by geography, with estimates of <1 case per 100,000 persons in Western Europe and the United States to 43 cases per 100,000 persons in Sub-Saharan Africa(Denning et al., 2011). On the other hand, if we look at the series published in the literature with few cases, these data could be highly overestimated. The impact of this fungal infection on mortality is also not well established, with a wide range in the series, from 4% to more than 50%(Despois et al., 2022; Lowes et al., 2017). Worse prognostic factors have also been described. However, it is not well known whether SAIA subtypes constitute a group with a relatively poor prognosis. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence of CAP, its risk factors and its mortality.

2. Methods

2.1. Design, Patients and Setting

The design was a descriptive longitudinal retrospective study developed in three tertiary hospitals of the Spanish System of Health: Hospital Marques de Valdecilla (HUMV) in Cantabria, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia (CAUPA) in Palencia and Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (CAUSA) in Salamanca placed in northern and western Spain. These three hospitals cover a total risk population above 800,000 inhabitants. We selected all patients admitted between 2009 and 2022 in the three hospitals with a diagnosis of aspergillosis according to the ICD-9-CM, code 117.3 cases 2009–2015, and the ICD-10, code B44, cases 2016–2022. We included patients in the study if they fulfilled the criteria for chronic aspergillosis according to the criteria of Denning et al.(Denning et al., 2016). Thus, we considered a simple aspergilloma (SA) if there was a single pulmonary cavity with a ball of fungal and serological or microbiological evidence of Aspergillus infection. Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA) was considered if there was one or more pulmonary cavities with or without aspergilloma over a minimum of 3 months of observation and if there was serological or microbiological evidence of Aspergillus infection. Chronic fibrosing aspergillosis pulmonary (CFAP) was defined if severe fibrotic destruction of two or more lobes of the lung was associated with CCPA. Subacute invasive aspergillosis (SAIA) was defined as the presence of cavitation or nodules and progressive consolidation occurring within 1–3 months of biopsy, with tissue invasion or positive Aspergillus galactomannan antigen in the blood or respiratory fluid. We excluded patients with haematological disorders if they had a definitive diagnosis of aplasia medullary or haematologic malignancy or if they had undergone a bone marrow transplant.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as percentages for categorical variables and as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. The incidence rate of CPA was calculated in the defined time period from 20092022 by dividing the number of new cases of CPA by the total number of disease-free periods per 100,000 person-years. The denominators were obtained from the National Statistical Institute (INE in Spanish) (

http://www.ine.es/). The chi-square test was used to assess associations among categorical variables, such as mortality and other demographic variables, and the intensity of these associations was expressed as the odds ratio (OR) and CI 95% for the OR. Additionally, we applied the corresponding regression models for multivariate analysis. Patient survival was estimated via a Kapplan Meier. Moreover, the log-rank test and the Cox proportional hazards model were used to assess differences between groups. We considered a statistically significant difference if the p value was <0.05. All of the data were analysed with SPSS 25 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences).

3. Results

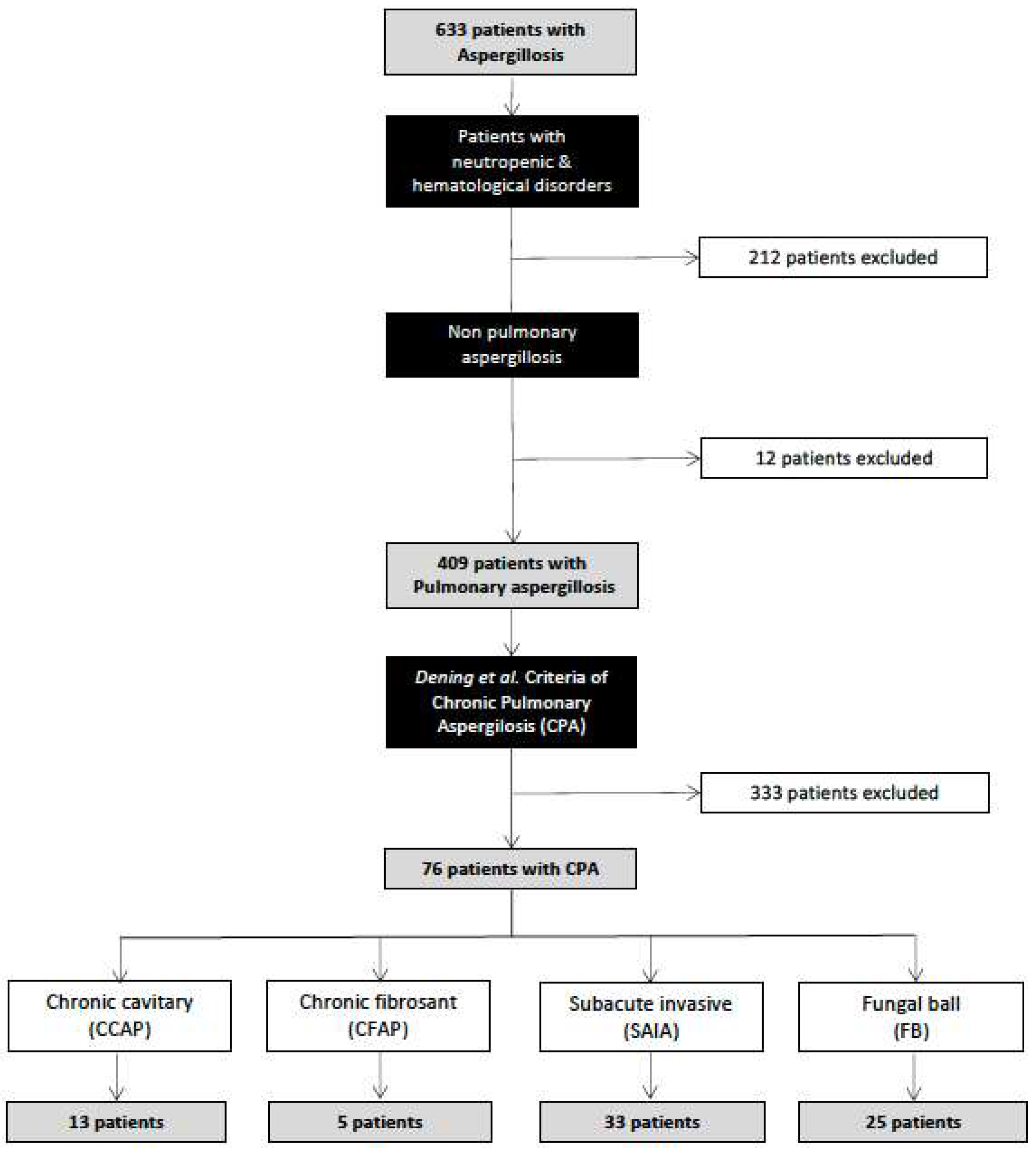

During the study period, 633 inpatients were recorded as having aspergillosis infection at the three study hospitals (HUMV, CAUPA and CAUSA). A total of 212 (33.5%) patients were excluded because of haematologic disorders, and 12 (1.8%) patients had aspergillosis in locations other than the lung. Among 409 patients recorded as having pulmonary aspergillosis, only 76 (18.6%) fulfilled the criteria for a diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA).

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of patients included in the study. Thus, the overall estimated incidence of CPA in our study area was 0.67 cases/100.000 inhabitants year.

The patients with CPA included in the study are shown in

Table 1.

The median age of the patients studied was 62 (IQR 60-66) years, and there were more men than women (male/female ratio 2.6). The subtypes most frequently detected were subacute invasive aspergillosis (SAIA) in 33 (43.4%) patients, simple aspergilloma (SA) in 25 (32.9%) patients, cavitary chronic aspergillosis (CCPA) in 13 (17.1%) patients and fibrosing chronic aspergillosis pulmonary (CFAP) in 5 (6.6%) patients. We assessed the comorbidities among the patients with CPA (

Table 1): chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 24 (31.6%) patients, diabetes mellitus in 17 (24%) patients, and remitted or active disease in 17 (24%) patients. A total of 54 (71%) patients used corticosteroids: 29 (38.2%) were systemic and 29 (38.2%) patients inhaled. Other immune suppressors were present in 24 (31.6%) patients, 14 with mycophenolate, 3 with hydroxychloroquine, and 2 with methotrexate and anti-TNF alfa, among others. The symptoms and signs most frequently presented were dyspnoea (42, 55.3%), fever (22, 28.9%) and haemoptysis (18, 23.7%). The clinical and comorbidity differences between SAIA and other subtypes of CPA are shown in

Table 2.

Previous tuberculosis was most common in the CCPA, CFPA and SA groups, whereas the use of glucocorticoids, immunosuppressors or solid organ transplant were most common among patients with SAIA (p<0.05).

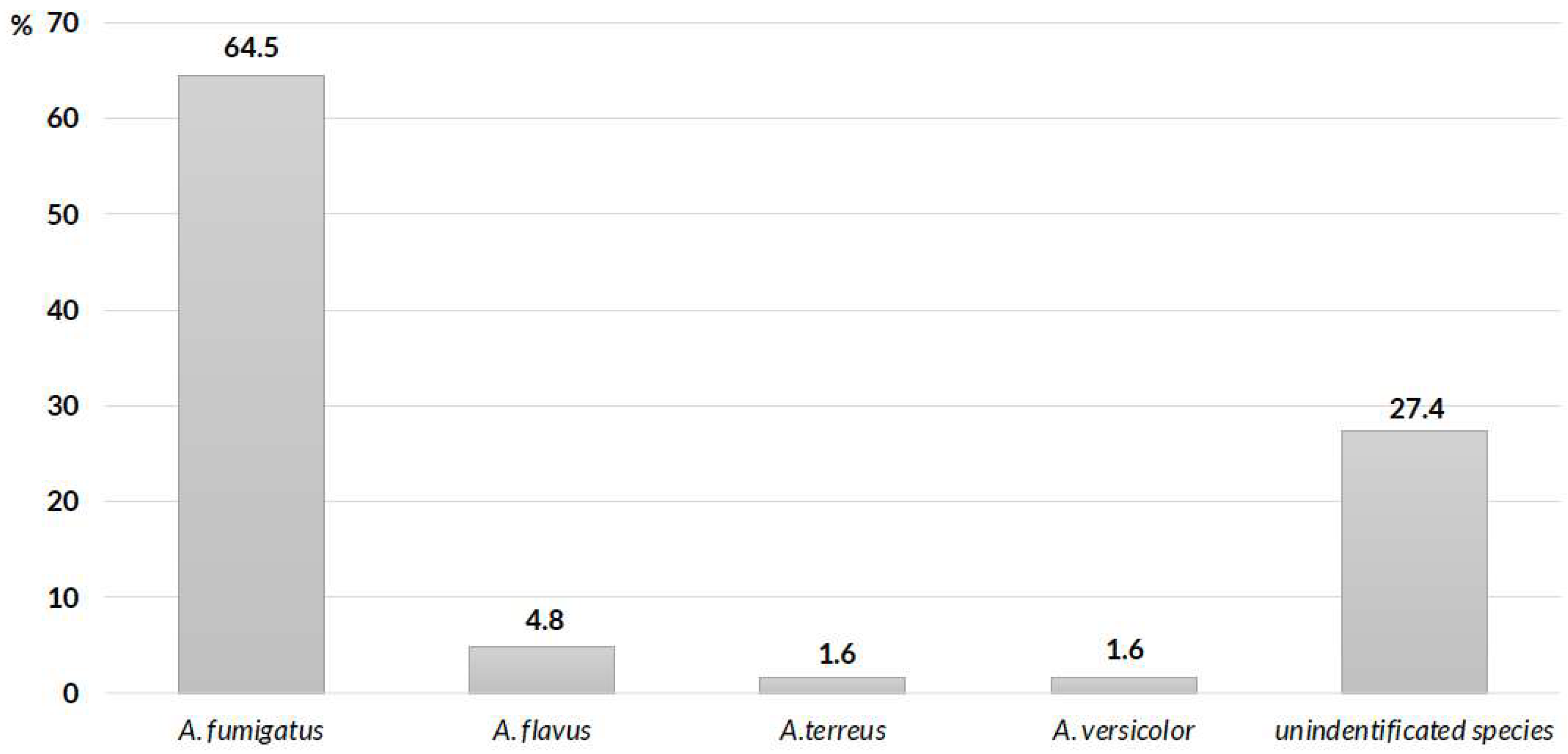

The main microbiological species involved were

A. fumigatus in 40 (64.5%) patients,

A. flavus in 3 (4.8%) patients and

A. terreus and

A. versicolor in 1 (1.6%) patient, whereas unidentified species were detected in 17 (27.4%) patients (

Figure 2). Microbiological diagnoses in these cases were made via histopathological methods in 38 patients (50%), whereas cultures of respiratory samples were available in 62 patients.

Anti-fungal therapy was used in 62 (81.6%) patients: voriconazole in 46 (60,5%) patients, itraconazole in 10 (15.3%) patients, and isavuconazole in 8 (10.5%) patients. Thirteen (17.1%) patients were treated with two or more anti-fungal agents.

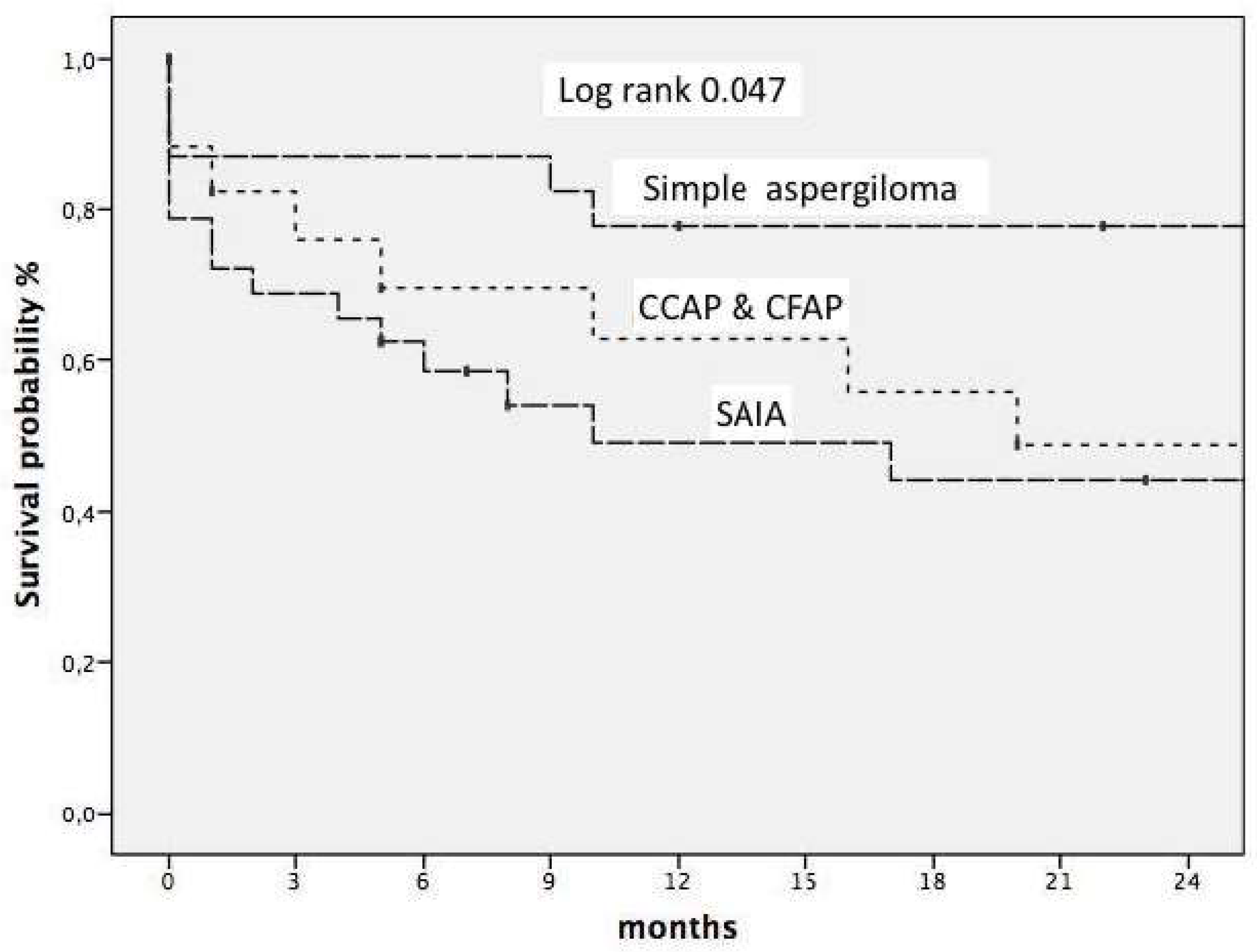

We studied early mortality. Thus, the overall three-month mortality rate among patients with CPA was 23%, which differed among the three main subtypes, namely, SA, CCPA & CFPA and SAIA, with mortality rates of 12%, 16, 6% and 31.2%, respectively. The predictors of early mortality were age >65 years (OR 3.0 CI 95 1.0–9.5 0.043) and SAIA subtype vs. other subtypes (OR 3.1 CI 95 1.0–9.5 p 0.042). We also studied survival in this cohort as shown

figure 3, with a mean follow-up of 73 (RIQ 41-122) months. We found that age >65 years [HR 4.1 (CI95 1.9–8.6), p<0.001)], diabetes mellitus [HR 3.3 (CI95 1.5–7.3 p 0.003)], subtype of CPA SAIA vs. simple SA [HR 7,4 (CI95 2,5–21,6, p<0,05)] and subtype CCPA/CFPC vs. SA [HR 4,9 (CI95 1,9–12,5, p<0,05)] were independent predictors of worse prognosis.

4. Discussion

In the last two decades, an increase in the incidence of aspergillosis has been reported, which is based on the prevalence of classical risk factors for invasive aspergillosis, as in the studies of admitted patients(González-Garcia et al., 2021; Rayens and Norris, 2022). Different factors are involved. On the one hand, the use of new immune-suppressive therapies, such as biological drugs, small-molecule kinase inhibitors or CAR-T-cell therapy, and epidemies caused by influenza A-09 and SARS-CoV-2 viruses could be involved in increasing the incidence of invasive aspergilosis(Latgé and Chamilos, 2019). On the other hand, demographic factors, such as population ageing, could also contribute to the increase in the number of elderly people with different comorbidities, such as diabetes, COPD or chronic kidney disease(Rayens and Norris, 2022). Unlike invasive aspergillosis, the classic factors associated with CPA, such as tuberculosis or pneumoconiosis, could be decreasing in Spain and other European countries(Global tuberculosis report 2023., n.d.;

www.isciii.es, n.d.). Therefore, we currently do not know the epidemiological situation of CPA. In our work, we evaluate, in a retrospective study from 2009 to 2022 in three public hospitals. We selected all records of inpatients with a recorded diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis, excluding those with neutropenia or other haematological disorders. These patients usually have effective protocols for prophylaxis, early diagnosis and preemptive treatment(Maertens et al., 2018). Thus, in our cohort, fewer than one-fifth of the patients with pulmonary aspergillosis met the CPA criteria, with an estimated incidence rate of less than 1 case/100,000 inhabitants/year. This incidence is lower than that reported by Maitre et al.(Maitre et al., 2021), who used data from the database of French hospital discharge summaries and reported an incidence three times higher than that reported in our cohort. These differences could be explained by the methods used by these authors because they accept pulmonary patients with chronic aspergillosis recorded as code ICD-BB4. However, in this work, the authors did not evaluate the medical records of patients, evaluating whether the patients met the European CPA criteria, and assumed that all patients recorded met them. According to data presented in our study and other papers(Camara et al., 2015), fewer than five inpatients classified as having aspergillosis fulfilled the criteria for PA. Thus, we believe that the data presented by Maitre and colleagues could overestimate the current incidence, possibly due to classification bias. In our study, the median age of the patients included was 62 years, and the proportion was also higher in males than in females, which coincides with the majority of published articles(Camara et al., 2015; Laursen et al., 2020; Rayens and Norris, 2022). A higher frequency of CCPA and simple aspergilloma than SAIA has been detected in a majority of studies in developing countries(Akram et al., 2021). However, in high-rent countries, discordant results have been reported in the literature. Thus, some studies in Spain and other countries reported a greater frequency of CCPA than SAIA(Aguilar-Company et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2022). In contrast, in two French studies with 44 and 24 patients, respectively, SAIA was the most frequent subtype, accounting for 50–62% of the total cases of CPA(Camuset et al., 2007; Maitre et al., 2021). In our study, we classified the different subtypes according to the Denning criteria, and we also found a higher percentage of SAIA cases. The greater ratio of SAIA to other subtypes in our study area could be related to a shift in the epidemiological profile of patients with CPA, with a decrease in the incidence of tuberculosis and an increase in the number of patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. This hypothesis is supported by our study and others(Chan et al., 2016), in which a strong association was found between the use of glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressants and SAIA, but there was no association with pulmonary tuberculosis. In contrast, other authors have not reported high exposure to glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressants in patients with SAIA. Hae-Seong Nam et al. reported in a cohort of patients with SAIA that only 19% received these treatments, and the main comorbidity detected was pulmonary tuberculosis, which was present in more than 90% of the patients(Nam et al., 2010). Tuberculosis is considered the main comorbidity associated with CPA and affects 32% to being involved from 32 to 90% of patients(Chan et al., 2016; Smith and Denning, 2010). In our work, we found that more than 20% of patients underwent lung solid organ transplantation. Invasive aspergillosis and SAIA are considered complications of the first year after the procedure(Herrera and Husain, 2019). Differentiating between aspergillosis pulmonary invasion and SAIA is frequently difficult since both states of immunosuppression could be involved. However, a cavitary lung with subacute progression, which is usually associated with a halo, could be associated more frequently with this last type(Zhong et al., 2022). An interesting finding of our study was the detection of CPA only in patients with pulmonary transplants, whereas we did not find cases in patients with other solid organ transplants, although lung transplants accounted for only 8% of the total solid organ transplants in Spain (

www.ont.es).

In terms of treatment, antifungals were administered to 62 patients (81.6%). The vast majority received voriconazole (74.2%), followed by itraconazole. Notably, the use of isavuconazole, a relatively recent broad-spectrum triazole antifungal, occurred in 8 patients (12.9%), which is not an insignificant number compared with other studies where it is not even reflected. There are no published data, although it has been proposed as a third line of treatment(Alastruey-Izquierdo et al., 2018). These data open the possibility of further studies in this direction. Another aim of our study was to assess overall mortality and its risk factors. Thus, we evaluated early mortality at 3 months and survival at 24 months. In a recent review, Lowes D. and colleagues reported severe differences in the mortality of CPA among different papers, ranging from 7% to 42% (Lowes et al., 2017). This fact could be due to methodological differences between the studies, according to the different types of patients included in each study and the follow-up time. In a large cohort of 387 patients in the UK, survival rates were 86%, 62% and 47% in 1, 5 and 10 years, respectively, with lower survival rates in patients with emphysema, severity of breathlessness determined by the Medical Research Council (MRC), resistance to azoles and bilateral pulmonary effects(Herrera and Husain, 2019). In our study, we found higher early mortality rates than other studies did, with the mean age and subtype of CPA being the only variables associated with mortality. Other works have also shown that older patients have a worse prognosis than younger patients do(Herrera and Husain, 2019). Data in the literature concerning the prognosis according to the different subtypes of CPA are scarce. Mortality in patients with CCPA has generally been higher than that in patients with simple aspergilloma(Herrera and Husain, 2019). However, data concerning SAIA are lacking. In our work, patients with SAIA had higher 3-month mortality than did those in the other groups. Paradoxically, some papers have indicated that the SAIA subtype could have a better response to voriconazole than the CCPA subtype to other antifungals(Cadranel et al., 2012). It is possible that a better radiological response is due to a greater fungal load and the absence of previous chronic lung lesions, such as fibrosis, cavities or chronic pulmonary parenchymal destruction. However, given the invasive and necrotizing nature of the SAIA subtype and the greater degree of immunosuppression in these patients(Hou et al., 2017), it is possible that SAIA patients have a better prognosis according to the clinical picture of invasive aspergillosis because a worse final prognosis is not surprising.

In conclusion, despite efforts of the European and American societies, there is currently still uncertainty in the diagnosis and classification of patients with CPA infection. Among the inpatients whose CPA was above one-fifth of all patients, only one-fifth met the criteria for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. The incidence rate estimated in our media is inferior to that previously reported. Three-month mortality in patients with CPA was high, with older age and subacute invasive aspergillosis subtype being the variable independent predictors of a worse prognosis..

Contribution Statement

JPLL, MBG: has conceived and written the main manuscript. PGG, JPLL, MBG, MBA, JFN, EAA, PS, MPRM, JLMB, MAGC: has acquired data of the work. She has prepared tables and figures. PGG, JPLL, MBG, MBA, JFN, EAA, PS, MPRM, JLMB, MAGC: has acquired, analyzed and interpreted data of the work. JPLL, MBG: has conceived and designed the main manuscript. II: has conceived the main manuscript. JPLL, PGG, MBG: has conceived, designed and written the main manuscript. All authors have reviewed the work critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding Declaration

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Human Ethics And Consent To Participate Declaration

Following privacy laws, patient data were anonymized by assigning a numerical code. All procedures described were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2013. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla CEIC with a number CEIMC 2020.353. The written consent was not obtained and it was specifically waived by the approving IRB. All data were analyzed anonymous. Consent to participate was not retrieved due to study design.

Data Availability

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Conflict Of Interest

All authors declare no potential conflicts of interest and no sources of support.

References

- Aguilar-Company J, Martín MT, Goterris-Bonet L, Martinez-Marti A, Sampol J, Roldán E, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in a tertiary care centre in Spain: A retrospective, observational study. Mycoses 2019;62:765–72. [CrossRef]

- Akram W, Ejaz MB, Mallhi TH, Sulaiman SA bin S, Khan AH. Clinical manifestations, associated risk factors and treatment outcomes of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA): Experiences from a tertiary care hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0259766. [CrossRef]

- Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cadranel J, Flick H, Godet C, Hennequin C, Hoenigl M, et al. Treatment of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Current Standards and Future Perspectives. Respiration 2018;96:159–70. [CrossRef]

- Cadranel J, Philippe B, Hennequin C, Bergeron A, Bergot E, Bourdin A, et al. Voriconazole for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: a prospective multicenter trial. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31:3231–9. [CrossRef]

- Camara B, Reymond E, Saint-Raymond C, Roth H, Brenier-Pinchart M, Pinel C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: a retrospective analysis of a tertiary hospital registry. Clin Respir J 2015;9:65–73. [CrossRef]

- Camuset J, Nunes H, Dombret M-C, Bergeron A, Henno P, Philippe B, et al. Treatment of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis by Voriconazole in Nonimmunocompromised Patients. Chest 2007;131:1435–41. [CrossRef]

- Chan JF-W, Lau SK-P, Wong SC-Y, To KK-W, So SY-C, Leung SS-M, et al. A 10-year study reveals clinical and laboratory evidence for the ‘semi-invasive’ properties of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Emerg Microbes Infect 2016;5:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Denning D, Pleuvry A, Cole D. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull World Heal Organ 2011;89:864–72. [CrossRef]

- Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J 2016;47:45–68. [CrossRef]

- Despois O, Chen SC-A, Gilroy N, Jones M, Wu P, Beardsley J. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Burden, Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes at a Large Australian Tertiary Hospital. J Fungi 2022;8:110. [CrossRef]

- Garg M, Bhatia H, Chandra T, Debi U, Sehgal IS, Prabhakar N, et al. Imaging Spectrum in Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2023;108:15–21. [CrossRef]

- Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization 2023 Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 30 IGO n.d.

- González-Garcia P, Alonso-Sardón M, López-Bernus A, Carbonell C, Romero-Alegría Á, Muro A, et al. Epidemiology of aspergillosis in hospitalised Spanish patients—A 21-year retrospective study. Mycoses 2021;64:520–7. [CrossRef]

- Herrera S, Husain S. Current State of the Diagnosis of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Lung Transplantation. Front Microbiol 2019;09:3273. [CrossRef]

- Hou X, Zhang H, Kou L, Lv W, Lu J, Li J. Clinical features and diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in Chinese patients. Medicine 2017;96:e8315. [CrossRef]

- Kanj A, Abdallah N, Soubani AO. The spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med 2018;141:121–31. [CrossRef]

- Latgé J-P, Chamilos G. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019;33. [CrossRef]

- Laursen CB, Davidsen JR, Acker LV, Salzer HJF, Seidel D, Cornely OA, et al. CPAnet Registry—An International Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Registry. J Fungi 2020;6:96. [CrossRef]

- Lowes D, Al-Shair K, Newton PJ, Morris J, Harris C, Rautemaa-Richardson R, et al. Predictors of mortality in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1601062. [CrossRef]

- Maertens JA, Girmenia C, Brüggemann RJ, Duarte RF, Kibbler CC, Ljungman P, et al. European guidelines for primary antifungal prophylaxis in adult haematology patients: summary of the updated recommendations from the European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73:3221–30. [CrossRef]

- Maitre T, Cottenet J, Godet C, Roussot A, Carime NA, Ok V, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: prevalence, favouring pulmonary diseases and prognosis. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2003345. [CrossRef]

- Nam H-S, Jeon K, Um S-W, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis: a review of 43 cases. Int J Infect Dis 2010;14:e479–82. [CrossRef]

- Rayens E, Norris KA. Prevalence and Healthcare Burden of Fungal Infections in the United States, 2018. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022;9:ofab593. [CrossRef]

- Smith NL, Denning DW. Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma. Eur Respir J 2010;37:865–72. [CrossRef]

- www.isciii.es. n.d. www.isciii.es.

- Zarif A, Thomas A, Vayro A. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: A Brief Review. Yale J Biol Med 2021;94:673–9.

- Zhong H, Wang Yaru, Gu Y, Ni Y, Wang Yu, Shen K, et al. Clinical Features, Diagnostic Test Performance, and Prognosis in Different Subtypes of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Front Med 2022;9:811807. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).