Introduction

Climate and nature considerations need to be rapidly integrated into mainstream financial decision-making to transition the world to meet sustainability goals. Finance that considers environmental, social and governance factors (ESG) in financial decision-making (Schoenmaker & Gardner, 2017), supports the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (Ziolo et al., 2021) and broader stakeholder value (Ozili, 2023) has surged in recent years. The impact investing market exceeded $1 trillion in 2021 for the first time (Hand et al., 2022). In 2021, in the run up to COP26, the Glasgow Financial Alliance of Net Zero (GFANZ) bought together 450 firms representing more than $130 trillion of private capital to commit to transforming the economy to net zero by aligning portfolios with the global target of limiting warming to 1.5 °C. Alongside this commitment, there was a surge in net zero pledges by corporate and financial institutions, evidencing the heightened recognition of sustainable finance.

Despite the surge of interest in sustainable finance, there is no single or universal definition. Here we take the definition of Migliorelli (2021) as “finance for sustainability” and consider the sustainability dimensions of ESG factors to meet sustainability goals. Monitoring and reporting on environmental and social factors of investments is challenged by a lack of reliable, consistent and timely information (EY Global, 2021). Currently the sector relies on self-reported, non-financial disclosures alongside inconsistent external or unstructured data sources (Jonsdottir et al., 2022). These data sources can be inaccurate, inconsistent, or not timely enough for effective decision making. According to a survey by consultancy EY, 46% of asset managers and 35% of banks view the lack of real-time information as a limitation on the value of ESG data and 50% of asset managers see a lack of forward-looking disclosure as limiting the value of ESG reporting (EY Global, 2021). Currently, ESG specific data providers produce aggregated ESG metrics from a range of self-reported and proxy data that is often qualitative for environmental and social factors. ESG ratings have been shown to be inconsistent (Gangi et al., 2022) correlating on average only 54% of the time, differing in scope, measurement and weightings (Berg et al., 2019) making them an unreliable metric of a company’s ESG performance. In addition, companies that disclose more data are more likely to be rated higher due to a potential ‘quantity bias’ favouring companies that produce more ESG data regardless of the quality (Chen et al., 2021). Despite these data problems, demand for sustainable funds continues to grow (Christiaen, 2023), increasingly with bottom-up demand from investors and customers demonstrating the urgent need to transition finance into green funds.

Nature and climate are inherently complex to measure and monitor (Patterson et al., 2022). The focus on metrics to represent ESG fails to capture the complexity of a business’s decision-making (In et al., 2019) overly focusing on singular measures whilst obscuring important insights into outcomes and broader values (Howard-Grenville, 2021). Investors are increasingly undertaking stewardship and engagement activities with clients and investees as a way to holistically influence companies to more sustainable operations rather than divestment (Christiaen, 2023). This approach makes use of more granular, system-wide data rather than aggregated ESG metrics which widens the focus to capture information on processes and systems governing outcomes and impacts rather than just inputs (Howard-Grenville, 2021).

A consequence of the lack of quality ESG data is that trust and confidence in sustainable investing has become eroded and accompanied by criticism and greenwashing allegations. This has led to several measures to try to address the problem. In an effort to build trust in the sector, the Financial Conduct Authority proposed a package of new measures to avoid greenwashing in the ESG market (Financial Conduct Authority, 2022). Emerging regulation mandating disclosures by the Task Force on climate-related financial disclosures (TCFD) and Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) are driving a surge of interest in alternative ESG data sources. These emerging standards aim to bring consistency and transparency into companies climate and nature risks and impacts accompanied by the development of decision-useful disclosure metrics (TCFD, 2022; TNFD, 2023b).

For improved reporting and monitoring of ESG, independent and transparent data are required with timely and reliable insights into both the impact of climate risk on companies and the impact of companies on the environment (‘double materiality’). Earth observation (EO) data that draws on advances in technology, artificial intelligence and computing power, is a powerful opportunity to directly observe environmental impacts and risks across time and space (e.g., Boyd, 2009; Caldecott et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2016; Singh, 2020), for climate (e.g., Fava & Vrieling, 2021; Le Cozannet et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2016) and biodiversity (Anderson, 2018; Corbane et al., 2015; Pettorelli et al., 2014). It is particularly promising for the financial sector because it is a neutral and unbiased source of information, provides global coverage, is timely, enables monitoring of trends over time, is consistent and assurable, and able to provide asset level insights (Caldecott et al., 2022). This concept of integrating EO data and analysis for financial decision making was coined ‘spatial finance’ by Caldecott et al. (2022).

Spatial finance has the potential to enhance transparency within the financial system for both practitioners and data providers and transform how sustainability is incorporated into financial decision making. At its most basic level it involves the combination of asset level data (i.e., as a minimum the location and ownership of a commercial asset) with observational level data providing information about local conditions and environmental characteristics (Insight-Finance, 2020). Observational data can be directly observed or measured by satellites or can be modelled using a combination of satellite observations combined with other data sources (e.g., eDNA or in-situ sampled data) (Christiaen, 2023).

The financial sector has long used geospatial data to understand risks and opportunities in commodities trading (e.g., Clark & Murtaugh, 2017; Launay & Guerif, 2005), insurance assessments (e.g., Black et al., 2016; de Leeuw et al., 2014), catastrophe modelling (Jones et al., 2017) and economic data analysis (e.g., Elvidge et al., 2009; Henderson et al., 2012) although many EO applications are at an early stage (Christiaen, 2021). However, EO data brings specific challenges due to its size and scale. Capitalising on the opportunity by providing specialist capabilities, the last few years have seen a rapidly growing market of small, niche EO data providers focused on providing insights to the financial sector, for example, near real-time monitoring of water stress (Watermarq), greenhouse gas and methane emission detection (GHGSat, MethaneSAT) and exposure to deforestation in supply chains (Global Forest Watch Pro). Whilst some financial institutions are starting to mainstream and integrate more EO data into their practices and it is evolving rapidly, the uptake within the sector remains limited (Insight-Finance, 2020).

Increasingly, emerging science and technology researchers and developers are encouraged to include stakeholders and others into decisions about the technology’s development so that science better serves both people and planet (Nature Editorial, 2018). Responsible innovation provides a framework for this inclusive approach to the development of emerging science and technologies upstream in the innovation process, allowing researchers to draw on stakeholder knowledge about the context of the problem they are trying to solve, and taking small steps towards co-producing science and technology that is both technically sound and socially robust (Owen et al., 2012; Stilgoe et al., 2013; Voegtlin & Scherer, 2017). Responsible innovation emphasises that innovation would benefit from the collective input of all stakeholders including researchers, policymakers, technology developers, investors, regulators and civil society; essentially all the stakeholders involved with and impacted by the innovation (Stilgoe et al., 2013). Whilst there has been some consideration of responsible innovation within the finance sector (Armstrong et al., 2012; Muniesa and Lenglet, 2013; Asante et al., 2014), there has been no exploration in spatial finance. Furthermore, there is an urgent need for intradisciplinary financial research crossing the boundaries of finance, sustainability, nature and climate that connects insights and extends dialogue from finance practitioners with the wider community (Wójcik et al., 2024) and knowledge transfer of environmental science into financial decision making (Hillier & Van Meeteren, 2024).

To fill this gap, we take a reflexive approach to explore the intersection of EO technology development, sustainable finance and responsible innovation with the intention of identifying opportunities to share understanding and increase responsible uptake within the sector. We address the need for more inclusive approaches by exploring stakeholder needs for EO as an ESG data source and the perceived barriers to the uptake of EO data for sustainable investment decision-making. We conclude by identifying some actionable insights to support the responsible development of EO as a technology for sustainable finance. This paper will therefore be of particular interest to EO scientists, product developers and policy makers to understand the financial sector needs for responsible development in the field. The discussion is focused on the assessment of ESG risks and impacts, nature and biodiversity risks and supply chain monitoring within the investment chain. The more mature markets of insurance, commodity trading and physical climate risk are outside the scope of this discussion.

Satellite Applications Catapult

The Satellite Applications Catapult (the ‘Catapult’) is a UK based government-backed innovation agency with the objective to deliver growth in the UK space sector. Overseen by the UKs innovation agency, Innovate UK, nine Catapults were established between 2011 and 2016 to bridge the gap between research and industry, encourage long-term private investment and support new collaboration in UK innovation (Science and Technology Select Committee, 2021). The Satellite Applications Catapult was subsequently established in 2013 to capitalise on satellites as an emerging commercial opportunity with the aim to capture a 10% share of the global space market by 2030 (Satellite Applications Catapult., 2023). It leverages satellite technologies and fosters innovation by bringing together diverse stakeholders across industry, business and research to exploit the innovation potential of UK industry and academia (Satellite Applications Catapult., 2023). Catapults are considered independent, not-for-profit innovation centres with one-third of funding from government, and the other two-thirds from industry partners and collaborative R&D funding (Science and Technology Select Committee, 2021).

The author participated in an 8-week immersion in the Catapult between July and August 2022 to conduct research with financial sector stakeholders to inform the ‘Space Commercialisation Engine’, a commercial development support programme aimed at “accelerating innovative and commercially viable EO ideas into the market” (Satellite Applications Catapult, 2024). This research culminated in a report titled ‘Earth Observation for Sustainable Finance’ (Wilson, 2022) that was produced for the Catapult’s own use and from which this article draws. Through discussions with financial sector employees, attendance at a sector conference and review of industry reports, the experience enabled the author to make a “critical reflection from within” (Zwart & Nelis, 2009) and reflect more broadly on the potential role of earth observation technology as an innovation for the sustainable finance sector within the context of responsible innovation. Additionally, insights gained have wider value to the research and practitioner community, to “demystify the complexity of finance” (van Meeteren & Bassens, 2024) and thus support the responsible development of EO technology that is responsive to the needs of stakeholders. This form of reflexive qualitative research also has particular value to “help close the gap” and “enrich the interaction between researchers and practitioners” (Ospina et al., 2018). Responsible innovation literature describes reflexivity as “holding up a mirror to one’s own activities, commitments and assumptions” (Stilgoe et al., 2013). Therefore, within this space of rapidly emerging technological innovation, reflexivity is an important component of responsible innovation to contribute to the ethical and sustainable advancement of technological solutions and addressing unintended consequences (Stilgoe et al., 2013). Such an approach encourages early involvement of diverse stakeholders in deliberations (Voegtlin et al., 2022) and creates an environment of introspection and critical reflection during the innovation process opening the dialogue to consider ethical implications, potential risks and unintended consequences (Lubberink et al., 2017). This approach therefore does not aim to create a complete assessment of the landscape but through an immersive exploration, interpretatively identify insights to support the responsible development of the use of EO data in the financial sector.

ESG Stakeholders and Their Data Needs

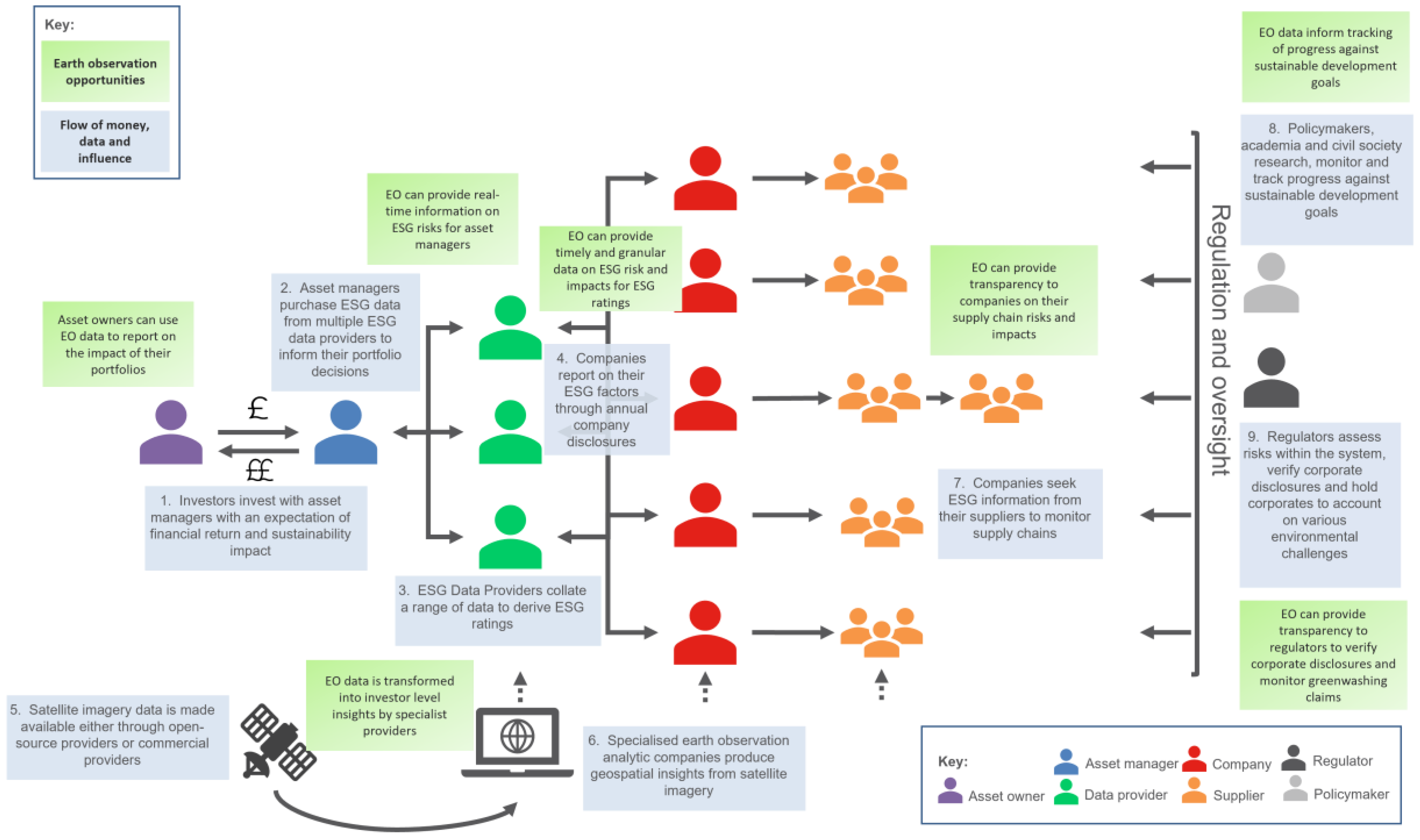

The following section describes the key financial stakeholders in the investment chain and their data needs. Each stakeholder uses ESG data in different ways and therefore has different EO data requirements (summarised in

Table 1). Many of these needs and opportunities are not exclusive to a single stakeholder but are intended as a representation of their priority needs. The investment chain is complex with many different actors, yet these actors have similar information needs around risks and data on ESG performance although they need it for different and often multiple purposes. As EO data can be used at various points in the investment chain for ESG monitoring and reporting,

Figure 1 provides a simplified visualisation of the opportunities for EO data in the investment chain (green boxes) alongside the flow of money and data (blue boxes) for context. The key stakeholders in the investment chain are also presented to illustrate the relationships between key stakeholders and their data use.

Companies

Companies are required to disclose non-financial information about their ESG performance, risks, impacts and sustainability strategies driven by investor demands and emerging regulations such as TCFD and TNFD (TCFD, 2017; TNFD, 2023b). Non-financial disclosure reports, typically released annually, enable companies to be transparent about the risks and opportunities they face. Emerging mandatory reporting requirements include the ‘double materiality’ concept, requiring assessment of not just the risks arising from the environment on the company, but also the impact of the company on society and the environment, which in turn creates financial risk. A company’s ESG performance can directly relate to its ability to attract investment with the majority of investment professionals believing that ESG programmes create shareholder value (McKinsey & Company, 2020). Prioritising the collection of accurate ESG data can be used by the company to communicate their sustainability efforts to investors and to ensure that the company uses the “right” sustainability data for assessments.

Companies will collect a range of non-financial data on material environmental, social, and governance factors to compile non-financial disclosure reports for investors and partners. Additionally, companies are increasingly asking their vendors, suppliers, and partners to disclose their ESG data to understand impacts within the supply chain and to incorporate supply chain ESG risks and impacts into their own disclosures. In addition to mandatory disclosures, companies can use ESG data to showcase business performance, demonstrate improvements, track goals and commitments, and build brand sustainability and trust with investors and consumers. ESG data can also help the company benchmark against the sector in terms of sustainability metrics, providing a source of information for actionable gap analysis to help internal advocates promote change and highlight areas of weakness to inform improved practices and policies.

The potential for EO data to companies is in the ability to provide real-time ESG data to support companies to take control and quantify their ESG impacts and risks for monitoring. It can also be a source of data to identify and monitor impacts within their supply chains and hold suppliers to account. Companies need data that they can easily track, that is current and accurate, cost-effective and delivers data in a clear, timely manner with actionable insights. For more accurate reporting and to provide assurances to investors that the company is positioned and well managed, data needs to enable them to quantify ESG impacts against metrics and be consistent and transparent.ESG Data Providers

ESG data providers play an important intermediary role by gathering and assessing information about companies’ ESG practices and offering equity screens, portfolio construction and analysis, competitive benchmarking, and risk analysis to financial institutions. This group includes the large market data providers such as Bloomberg and MSCI, the ESG exclusive data providers such as Sustainalytics and other specialised data providers. Increasingly, small niche EO specialist providers are emerging to provide EO derived insights to the financial market but as yet the market remains unconsolidated.

Data providers incorporate data from multiple publicly available sources to aggregate and generate ESG ratings. The larger data providers offer a range of ESG data products including climate change metrics, sustainability impact metrics and ESG controversies. They include a wide range of data to inform these products both quantitative and qualitative. This includes information from companies such as mandatory disclosures, sustainability reports or annual reports; external data sources from media, regulators, information on litigations and penalties e.g., to inform ESG controversies; and specialised datasets that could include geospatial data and climate or nature metrics.

EO data has the potential to play a significant role in providing ESG data providers with ESG performance and trends over time from an independent data source. ESG data providers have an interest in broad scale sector level data, from a sub-national to local-level resolution, in a format to enable aggregation and dis-aggregation of data for different purposes. This makes the global and consistent nature of EO data a valuable source. Data at a global level needs to be standardised and comparable across sectors and geographies and timely in that it is regularly updated and can be used to track the impact of events and see trends over time. The format of data should be either already processed or with ease of processing and interrogation. It needs to be in an easily accessible format which could include online mapping tools, direct downloads or APIs that can be integrated into existing workflows. EO is only one source of data informing ESG ratings and so EO insights need to be available in a format that can be integrated with other geospatial and non-geospatial data.

Certainty is needed to confidently attribute an environmental impact to a company if the data is to be included in ESG ratings. There is therefore a balance to be struck between cost and complexity of processing with resolution and granularity of data. Many ESG data providers already have experience working with and integrating geospatial data into their processes. However, due to the scale and specialism required for EO data, ESG data providers often lack in-house resources, both capacity and capability, and computational power to process and interrogate EO datasets themselves and draw insights. On the other hand, more specialist providers appear interested in developing capacity and competency in-house to provide a competitive edge.

Asset Managers

Asset Managers manage and monitor a company’s assets on behalf of asset owners or individual investors with the aim to maximise the return on investment. Non-financial factors are being increasingly recognised as having a material financial impact on a company’s performance (McKinsey & Company, 2020) therefore investors may use ESG criteria to assess a company’s performance to inform investment decisions and portfolio construction. ESG data can be used in benchmarking companies against industry ESG performance, relative to the sector, against its peers and test performance implications of excluding that company from a portfolio. Asset managers are a large and diverse stakeholder group. Their data needs will vary significantly depending on the investment strategy of a particular portfolio. For example, in alpha investing (a type of investment strategy that seeks to generate returns by outperforming the market), investors are interested in granular data that is not readily available in order to leverage a competitive advantage (Young In et al., 2019). In contrast, equity investors may be more interested in the temporal frequency of data as they rebalance their portfolios on a monthly or more regular basis (Young In et al., 2019). EO can be of particular relevance to institutional investors, who in contrast, may want access to detailed, granular data with temporal trends to provide insight and confidence to make long-term investment decisions.

Impact investing is a type of investment strategy that seeks to bring about positive social and environmental improvements whilst delivering financial returns through actively investing in positive environmental and sustainability projects (Global Impact Investing Network, 2023). In contrast, impact investors use ESG data to identify positive opportunities rather than for negative screening (i.e., who not to invest in). They therefore use granular ESG data to measure and monitor the social and/or environmental impact created through investments and for portfolio reporting to clients and progress against sustainability targets. As well as using ESG data to determine where to invest, bespoke company level data can be used for stewardship and engagement of portfolio companies to influence performance and progress against sustainability targets. Asset managers see that active stewardship with companies, particularly those that are in hard to abate sectors, can in some cases speed up the journey to sustainability rather than divesting. Where engagement does not succeed, data may be used for proxy voting.

Asset managers need an objective way to assess the ESG performance of a company as they are more dependent than banks and insurers on publicly available sources of non-financial data. They are interested in broad industry level data and the ability to monitor trends i.e., ‘roughly right’ at a larger scale rather than high accuracy at a local level. More granular bespoke data at the company level is more useful for active stewardship and engagement activities to influence companies in their transition plans. EO data needs to fit within existing processes currently requiring geospatial insights to be aggregated into values and metrics to be able to incorporate into financial decision- making processes. Often the format of granular ESG data is not compatible with current processes due to inherent complexity and spatiality requiring a change in the way that data is handled and interpreted. Many asset manager institutions are unlikely to develop the specialist in-house resource and capability to use alternative ESG data like EO data, so require investor ready data from external providers. Conversely, impact investors have slightly differing needs as they are interested in using EO data to identify and monitor environmentally and socially positive investment opportunities at the company level so are more likely to develop resource and capacity in-house. Asset managers are mainly interested in working with a few providers of ESG data requiring the market to consolidate. They want transparent and robust methodologies from ESG data providers and seamless integration into existing workflows. As a result, buying in data from niche specialist providers is unattractive to many asset managers as there is a lack of clarity on methodologies and in interpreting results.Asset Owners

Asset owners appear increasingly interested in aligning their portfolios with sustainability targets and assessing the long-term resilience of their funds. Within this group of stakeholders, banks monitor their lending and investment portfolios and insurance monitor their underwriting portfolios against ESG factors. Asset owners integrating ESG considerations into their investment processes are considering a wide range of climate or environmental related risks and impacts and are increasingly making sustainability commitments in response to consumer demand. Insurance institutions also quantify and predict climate risk for their physical assets to inform insurance premiums, however this should not be confused with ESG reporting and is outside the scope of this paper. Asset owners often hold long term investments which require understanding, identifying and managing ESG risks and opportunities to rigorously assess the long-term resilience of their asset allocation, portfolio construction and risk management decision-making processes. A number of asset owners were seen to be incorporating ESG into portfolio construction to identify unintended risk. Likewise, banks are seen to be using ESG data to monitor lending and investment portfolios risk and impacts. ESG data is used in stress testing of climate risk exposures against scenarios to be able to address and oversee these risks within the company’s overall business. It is used in internal reporting to investment/risk committees, boards as well as external reporting to stakeholders and customers against sustainability targets and commitments. It is also used to integrate sustainability criteria into their internal credit score and report on green/sustainable bonds. More asset owners are reporting on climate risk exposure and alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The need to engage with stakeholders and communicate ESG portfolio characteristics is driving a need for greater transparency. Banks appear to have an awareness of the potential of EO for ESG monitoring but are still early stage in developing techniques and approaches for deriving insights. Some larger banks are building capability and capacity in-house with the aim to build their own ESG frameworks and models that are specific and relevant to them. The challenges of using EO data

Here we identify and describe five dominant challenges (

Table 2). It is worth noting that stakeholders do not experience lack of data to be the main barrier or challenge. Instead, interpretation, accessibility, quality, format, relevance, scale, and transparency as their primary challenges of using EO data.

Challenge 1: Lack of Stakeholder Awareness, Capacity and Demand

There is no shortage of EO data, but rather a lack of understanding of how data can be used to derive information that is decision-relevant for stakeholders. Asset managers often need more use cases to enable them to see the way that EO data can be understood and benefit them. In general, the financial community has low awareness about the advancements and availability of novel EO data and the potential for it to enhance their decision-making, making it hard to articulate their data needs. Therefore, until asset managers, as the main customers of ESG data providers, expect and request EO enhanced data, the established vendors will not actively develop the means to provide it. Awareness is growing in the UK due in part to several initiatives driven by the Spatial Finance Initiative, Satellite Applications Catapult and European Space Agency alongside TCFD and TNFD discussions and developments and collaborative industry reports (Patterson et al., 2022) although may still need to filter across the sector. Due to the technical nature of EO data, financial institutions and ESG data providers were seen to currently lack the resources (both capability and capacity) and the computational power to draw insights from satellite imagery. For ESG data providers to incorporate satellite data into existing workflows would require a substantial increase in resource with specialist skills that is not currently available in-house. In comparison to existing geospatial capabilities, the computational power requirements for the analysis of EO data is a particularly limiting factor that requires investment by institutions. Additionally, understanding science-based metrics requires specific domain knowledge, without which it is a challenge for financial institutions to use the data and interpret the results appropriately.

Challenge 3: Lack of Consistency in Methods and Standards Risks Greenwashing

Consistency in metrics is key to be able to measure trends over time and compare between and within industries. The TNFD (TNFD, 2023b) and TCFD (TCFD, 2021) are creating consistency in company disclosures through the development of reporting metrics and indicators which go some way to help standardise ESG reporting. However, due to commerciality, there is often a lack of transparency in the methods and algorithms employed by specialist EO analytics providers to produce metrics. This leads to inconsistency risking greenwashing and reducing trust in EO products as has been seen already within the ESG ratings market to date. Commercial providers may overstate the ability of their products and financial institutions may not have the time or resources to scrutinise the details of methods used (Patterson et al., 2022). In recognition of these pitfalls, Rossi et al. (2024) proposed a geospatial ESG scoring framework to support consistent assessment of environmental impacts by corporates and investors using EO data.

Due to fragmentation in the market, the complexity of data, interpretation and computational power required to turn EO data into useful insights, many financial institutions are likely to use ESG data providers to translate EO information into useable scores. On the other hand, due to the importance of measuring progress against environmental and social goals, impact investors are more likely to develop in-house resources and capability, to enable them to have fuller understanding and insight into datasets and their application. Without consistent methods across the industry, there is a risk that data gaps get filled with sub-standard data, the most preferable scores are cherry-picked from commercial providers and data is inappropriately interpreted creating negative consequences in how EO data is used in financial decision making. In recognition of these limitations particularly in nature-related data, a high-level scoping study by the TNFD (TNFD, 2023a) proposed the creation of a global nature related public data facility. The aim would be to “connect existing but disparate nature data sets to a shared point of access to enhance accessibility” and improve consistency through creating common nature data methodologies and standards. The vision includes enabling public and private sector analytics to sit on top of the foundational data stack so that decision making would be more robust, transparent, and reproducible.

Challenge 4: Availability and Quality of Data Restricting Application

Lack of confidence in the quality of data for investor decision was observed to be currently affecting uptake. Quality of data is affected by bias, data limitations, data gaps and resolution. Insights risk being biased, or errors compounded when multiple indicators are derived from the same EO source datasets particularly with the move towards more complex assessments and modelled insights. Biodiversity impacts are particularly difficult to define with confidence to a local level and at a global scale. As stated by the TNFD “Nature-related [data] is still not current, consistent or comprehensive, nor accurate enough to provide the level of confidence and assurance required by data users” (TNFD, 2023a). Whilst existing datasets may provide useful insights, they cannot be treated as a definitive source of biodiversity impact due to the limitations and complexity of measuring biodiversity (Patterson et al., 2022). There is also a bias towards what is more easily measurable ignoring the more difficult to measure aspects of nature. For example, EO derived biodiversity data tends to be skewed towards the terrestrial zone as the marine zone is much more complex to quantify and less technically advanced. This creates a risk of bias towards certain ESG issues and ultimately biasing financial decision-making.

There is a trade-off between higher temporal and spatial resolution datasets with the cost and computational power required. Open-source EO data such as from the European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus programme and NASA Landsat are limited in spatial resolution compared to commercially available high-resolution imagery but may lack the temporal record of longer satellite programmes. The resolution required depends on the task, but many biodiversity impacts require high resolution imagery. As assets of interest to financial institutions are often small, to be able to observe impacts (e.g., deforestation, pollution events etc) at the asset level requires high resolution observational datasets (Patterson et al., 2022). Open-source observational biodiversity datasets can be unreliable and lack historical data to consider trends over time. Of 105 open-source biodiversity relevant datasets listed on the UN Biodiversity Lab only 38% had values for more than one year and 19% had consistent records for over 5 years (Patterson et al., 2022).

A significant challenge is in accurately attributing environmental impacts with certainty to individual companies particularly in urban areas. For example, often assets of interest are in urban areas complicating the ability to attribute impacts (e.g., emissions) with confidence to a specific company in close proximity to other assets.

Gaps in asset level data (specifically, the exact asset location with a minimum of ownership information) inhibit the ability to understand the impact of and risks to assets and along supply chains (Caldecott et al., 2022). This is key to be able to derive insights on risks, opportunities, and impacts. Unfortunately, comprehensive and global datasets in many sectors are rare and also challenging to create. Agricultural supply chains are particularly lacking and challenging due to the complexity of supply chains and ownership. Whilst ESG data providers hold their own asset location databases, they are often not complete. As described by Caldecott et al. (2022) it is possible to develop asset-level databases using geospatial techniques and artificial intelligence (e.g., computer vision) to map industrial facilities and NLP methods to extract asset information. A project of particular note that is creating advances in this area is the GeoAsset Project led by the Centre for Greening Finance Initiative which has developed global asset databases for high impact sectors including the cement and steel sectors (McCarten et al., 2021; Tkachenko et al., 2023).

Challenge 5: Perceived Readiness of Data Inappropriate for Investment and Regulatory Needs

Due to many of the challenges discussed already, EO applications are considered by some financial institutions to not be commercially ready and scalable yet. For some stakeholders there appears to be an internal perception that the emerging methods and data sources are not proven so reducing the extent that it is appropriate to incorporate EO into internal financial decision-making processes. Stakeholders need to see methods that are established and proven to have the confidence to consider investing and incorporating EO into their processes. Readiness, however, is a particular challenge for regulators. Technology needs to be proven to be completely reliable before it can be used in regulation as the legal process requires data to meet a certain standard and use established methodologies. Governments are challenged by the rate of change in technology and not always sufficiently agile to keep apace. Civil society and NGOs also have an important role within oversight. They have an interest to track progress against international agreements and implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals as well as scrutiny against regulatory requirements. One of the benefits regularly extolled for spatial finance is transparency for all stakeholders. However, due to the costs of commercial EO datasets, there is a risk that NGOs become priced out and unable to access the higher resolution commercial datasets limiting the opportunities for transparency and scrutiny.

Discussion and Conclusions

This article sets out a baseline of stakeholder needs to facilitate cross-sector and interdisciplinary understanding of the challenges and barriers facing the uptake of EO data in the financial sector in order to support inclusive approaches and broader responsible development of this technology. Advances in satellite data has enabled a massive growth in available, consistent, high-resolution data for monitoring assets and the impacts of financial investments. However, whilst the potential of EO data has been established elsewhere, consistent uptake of the technology to enable sustainable investment decision making remains limited. This research identified the key stakeholders in the investment chain, their data needs, the opportunities for EO data for each followed by five challenges within the financial UK sector. Specifically, this article makes three contributions.

First, there are multiple stakeholders of EO data within the financial sector with multiple and differing data needs requiring applications to be developed in user-specific ways. Stakeholders go beyond investment decision makers and include civil society, regulators and policy makers. It is important for technology developers to recognize the diversity of stakeholders and not view the financial sector as a single unitary user. Doing so will increase the likelihood that EO data usefully impacts the sector by addressing specific needs.

Second, rather than lack of data, five challenges to the uptake of EO data were identified: 1] lack of stakeholder awareness, capacity and demand; 2] availability and format of satellite imagery incompatible with investor needs; 3] lack of consistency in methods and standards; 4] availability and quality of data restricting application; 5] perceived readiness of data inappropriate for investment and regulatory needs. Currently, these challenges create barriers to the uptake of EO data in the sector by not providing the level of confidence and assurance required by stakeholders at a time when rapid transition is possible. These challenges are not unique and similarities have been seen in the uptake of technology and data within other related sectors including; lack of data continuity, data quality, spatial resolution (de Leeuw et al., 2014), real-time accessibility, inconsistent global solutions (Senol Cabi et al., 2021), data sharing barriers (Timms et al., 2022), translation of metrics to stakeholder needs (Hillier et al., 2023), lack of in-house capability (Bank of England, 2022), and lack of understanding of the technology potential for the sector (de Leeuw et al., 2014).

Third, if EO data is to be relevant to the breadth of stakeholders within the financial sector and enable them to make sustainable financial decisions, EO data providers need to engage with stakeholders to better understand their specific needs and the challenges facing data uptake. Such engagement will enable the responsible development of EO data so that it contributes to the development of a transparent system capable of delivering sustainability outcomes across the whole investment chain. All new science and technology emerge in sectors with multiple players with different vested interests and degrees of power (Von Schomberg, 2013). Technology trajectories are shaped by these actors and therefore without broader and inclusive foresight processes and assessment of impacts beyond market benefits and risks, there is a danger that EO data will evolve to serve the interests of the few at the expense of achieving its full potential and delivering the sustainability outcomes required for a just sustainable transition. Whilst regulatory oversight is necessary for evidence-based, consistent and just application, it needs to be preceded by regulatory insight with sufficient understanding of the challenges faced by the sector to create effective policies and legislation (Vinuesa et al., 2020).

The challenges identified here raise important ethical considerations for the application of EO data into financial decision-making where non-experts are the end-users of algorithmic models and may not have the data literacy to appreciate the limits or applicability. Transparency and explicability (Jobin et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2022) are key principles to provide accountability and fairness. This should involve an interpretable explanation of methods behind EO applications, including factors such as uncertainty, timeliness, completeness, sampling method, provenance, and volume of training data (Tsamados et al., 2021). Inconsistency and gaps in datasets required for EO applications requires scrutiny and interpretation for financial decision-making to avoid creating “unjustified actions from inconclusive evidence” (Tsamados et al., 2021). For algorithms to be designed and deployed in a fair and equitable manner, they need to take into account the potential impact on different groups of stakeholders (Tsamados et al., 2021).

Responsible innovation offers a framework and process for responding to these challenges. Bringing together actors from the EO community and financial sector for greater collective deliberation can create open and honest dialogue during the innovation process and ensure that EO product development meets investor needs (Lubberink et al., 2017). Integration, not just between stakeholders and developers but also collaboration across research, policy, industry and civil society can create the conditions to deliberate on the challenges of transparency, accessibility, availability and interpretability of data and methods. Furthermore, the co-ordination and transfer of knowledge and learning across sectors responding to similar challenges (Hillier & Van Meeteren, 2024) can expediate the responsible uptake of technology to support the sustainability transition.

There is a need to inclusively open up visions, purposes and questions for collective deliberation (Owen et al., 2013) so that all stakeholders become mutually responsive to each other (Von Schomberg, 2013). This opening up and knowledge co-production is increasingly being encouraged by funders e.g., UKRI and the EU Horizon programme as well as by key scientific organisations (Nature Editorial, 2018). The inclusion of stakeholders upstream in the innovation process can help steer EO data to achieve more sustainable and societally desirable outcomes (Lubberink et al., 2017) whilst being responsive to the environmental challenges facing society (Voegtlin et al., 2022; Von Schomberg, 2013). Stirling (2008) and Voegtlin et al. (2022) argue that this ‘opening up’ of decisions about the direction of technology results in ‘better’ technology capable of ‘doing good’. Satellite applications in the financial sector and the development of EO data is such an emerging technology with the potential to ‘do good’. However, such a trajectory should not be assumed or taken for granted. Sitting at the intersection between industry and research and tasked to drive innovation, the Satellite Applications Catapult has an important role to play in supporting satellite applications in the financial sector. It also has the potential to be a key actor in the responsible development of ‘better’ EO data to maximize value to both the sector and society.

References

- Anderson, C. B. Biodiversity monitoring, earth observations and the ecology of scale. Ecology Letters 2018, 21(10), 1572–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. SSRN Electronic Journal 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, E.; Tarnavsky, E.; Maidment, R.; Greatrex, H.; Mookerjee, A.; Quaife, T.; Brown, M. The Use of Remotely Sensed Rainfall for Managing Drought Risk: A Case Study of Weather Index Insurance in Zambia. Remote Sensing 2016, Vol. 8(Page 342, 8(4)), 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D. S. Remote sensing in physical geography: A twenty-first-century perspective. Progress in Physical Geography 2009, 33(4), 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldecott, B.; McCarten, M.; Christiaen, C.; Hickey, C. Spatial finance: practical and theoretical contributions to financial analysis. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; von Behren, R.; Mussalli, G. The unreasonable attractiveness of more ESG data. Journal of Portfolio Management 2021, 48(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaen, C. State and Trends of Spatial Finance 2023: Fundamental Building Blocks for Transparency and Accountability in Green Finance n.d.

- Christiaen, C. State and Trends of Spatial Finance 2021: Next Generation Climate and Environmental Analytics for Resilient Finance. In Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment - Spatial Finance Initiative; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.; Murtaugh, D. Satellites Are Reshaping How Traders Track Earthly Commodities - Bloomberg

. Bloomberg. 2017. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-12-16/satellites-are-reshaping-how-traders-track-earthly-commodities.

- Corbane, C.; Lang, S.; Pipkins, K.; Alleaume, S.; Deshayes, M.; García Millán, V. E.; Strasser, T.; Vanden Borre, J.; Toon, S.; Michael, F. Remote sensing for mapping natural habitats and their conservation status – New opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2015, 37, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, J.; Vrieling, A.; Shee, A.; Atzberger, C.; Hadgu, K. M.; Biradar, C. M.; Keah, H.; Turvey, C. The Potential and Uptake of Remote Sensing in Insurance: A Review. Remote Sensing 2014, Vol. 6 6(11), 10888-10912 10888–10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvidge, C. D.; Sutton, P. C.; Ghosh, T.; Tuttle, B. T.; Baugh, K. E.; Bhaduri, B.; Bright, E. A global poverty map derived from satellite data. Computers & Geosciences 2009, 35(8), 1652–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EY Global. Why data remains the biggest ESG investing challenge for asset managers 2021.

- Fava, F.; Vrieling, A. Earth observation for drought risk financing in pastoral systems of sub-Saharan Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2021, 48, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Conduct Authority. Press Release: FCA proposes new rules to tackle greenwashing

. 2022. Available online: https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/fca-proposes-new-rules-tackle-greenwashing.

- Gangi, F.; Varrone, N.; Daniele, L. M.; Coscia, M. Mainstreaming socially responsible investment: Do environmental, social and governance ratings of investment funds converge? Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Impact Investing Network.

Impact Investing: A guide to this dynamic market

. 2023. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/giin-web-assets/giin/assets/publication/post/giin-impact-investing-guide.pdf.

- Guo, H.; Wang, L.; Liang, D. Big Earth Data from space: a new engine for Earth science. Science Bulletin 2016, 61(7), 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, D.; Ringel, B.; Danel, A. Sizing the impact investing market 2022.

- Henderson, J. V.; Storeygard, A.; Weil, D. N. Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space. American Economic Review 2012, 102(2), 994–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, J. K.; Champion, A.; Perkins, T.; Garry, F. K.; Bloomfield, H. GC Insights: Open R-code to communicate the impact of co-occurring natural hazards 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hillier, J. K.; Van Meeteren, M. Co-RISK: a tool to co-create impactful university-industry projects for natural hazard risk mitigation. Geoscience Communication 2024, 7(1), 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J. ESG Impact Is Hard to Measure — But It’s Not Impossible

. In Harvard Business Review; 2021; Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/01/esg-impact-is-hard-to-measure-but-its-not-impossible.

- In, S. Y.; Rook, D.; Monk, A. Integrating Alternative Data (Also Known as ESG Data) in Investment Decision Making. 2019, 48(3), 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insight-Finance, E.

Spatial Finance: Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing World

. 2020. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/850821606884753194/spatial-finance-challenges-and-opportunities-in-a-changing-world.

- Jobin, A.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 2019 1:9(1(9)), 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Mitchell-Wallace, K.; Foote, M.; Hillier, J. Fundamentals. Natural Catastrophe Risk Management and Modelling 2017, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, B.; Sigurjonsson, T. O.; Johannsdottir, L.; Wendt, S. Barriers to Using ESG Data for Investment Decisions. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. A.; Badshah, S.; Liang, P.; Waseem, M.; Khan, B.; Ahmad, A.; Fahmideh, M.; Niazi, M.; Akbar, M. A. Ethics of AI: A Systematic Literature Review of Principles and Challenges. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 2022, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launay, M.; Guerif, M. Assimilating remote sensing data into a crop model to improve predictive performance for spatial applications. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2005, 111(1–4), 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cozannet, G.; Kervyn, M.; Russo, S.; Ifejika Speranza, C.; Ferrier, P.; Foumelis, M.; Lopez, T.; Modaressi, H. Space-Based Earth Observations for Disaster Risk Management. Surveys in Geophysics 2020, 41(6), 1209–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubberink, R.; Blok, V.; van Ophem, J.; Omta, O. Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Responsible, Social and Sustainable Innovation Practices. Sustainability 2017, Vol. 9(Page 721, 9(5)), 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarten, M.; Bayaraa, M.; Caldecott, B.; Christiaen, C.; Hickey, C.; Kampmann, D.; Layman, C.; Rossi, C.; Scott, K.; Tang, K.; Tkachenko, N.; Yoken, D. Global Database of Iron and Steel Production Assets; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey; Company. The ESG premium: New perspectives on value and performance; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorelli, M. What Do We Mean by Sustainable Finance? Assessing Existing Frameworks and Policy Risks 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nature Editorial. The best research is produced when researchers and communities work together. Nature 2018, 562(7725), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ospina, S. M.; Esteve, M.; Lee, S. Assessing Qualitative Studies in Public Administration Research. Public Administration Review 2018, 78(4), 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Science and Public Policy 2012, 39(6), 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Stilgoe, J.; Macnaghten, P.; Gorman, M.; Fisher, E.; Guston, D. A Framework for Responsible Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; 2013; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. Theories of Sustainable Finance. Managing Global Transitions 2023, 21(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.; Schmitt, S.; Izquierdo, P.; Tibaldeschi, P.; Bellfield, H.; Wang, D.; Gurhy, B.; d’Aspremont, A.; Tello, P.; Bonfils, C.; Brumby, S.; Barabino, J.; Volkmer, N.; Zheng, J.; Tayleur, C.; D’Agnese, F.; A. Armstrong D’Agnese, J. Geospatial ESG: The emerging application of geospatial data for gaining “environmental” insights on the asset, corporate and sovereign level

. 2022. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/pages/terms-of-use-en.

- Pettorelli, N.; Laurance, W. F.; O’Brien, T. G.; Wegmann, M.; Nagendra, H.; Turner, W. Satellite remote sensing for applied ecologists: opportunities and challenges. Journal of Applied Ecology 2014, 51(4), 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Byrne, J. G.; Christiaen, C. Breaking the ESG rating divergence: An open geospatial framework for environmental scores. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 349, 119477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Satellite Applications Catapult Satellite Applications Catapult; Https://Sa.Catapult.Org.Uk/, 21 November 2023.

- Satellite Applications Catapult Space Commercialisation Engine. 2024. Available online: https://sa.catapult.org.uk/space-commercialisation-engine/.

- Schoenmaker, D.; Gardner, S.

Investing for the common good: a sustainable finance framework

. 2017. Available online: www.bruegel.org.

- Science and Technology Select Committee. Catapults: bridging the gap between research and industry

. 2021. Available online: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords-.

- Senol Cabi, N.; Thomson, T.; Gascoigne, J.; Ali, H. How Earth Observation Informs the Activities of the Re/Insurance Industry on Managing Flood Risk. In Earth Observation for Flood Applications: Progress and Perspectives; 2021; pp. 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. P. Earth observation and sustainable development goals. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2020, 11(1), (i)–(vi). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Research Policy 2013, 42(9), 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCFD. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

. 2017. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report.pdf.

- TCFD. Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: Guidance on Metrics, Targets, and Transition Plans (Issue October). 2021. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/07/2021-Metrics_Targets_Guidance-1.pdf.

- TCFD. Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: Overview

. 2022. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2022/12/tcfd-2022-overview-booklet.pdf.

- Timms, P. D.; Hillier, J. K.; Holland, C. P. Increase data sharing or die? An initial view for natural catastrophe insurance. Geography 2022, 107(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, N.; Tang, K.; McCarten, M.; Reece, S.; Kampmann, D.; Hickey, C.; Bayaraa, M.; Foster, P.; Layman, C.; Rossi, C.; Scott, K.; Yoken, D.; Christiaen, C.; Caldecott, B. Global database of cement production assets and upstream suppliers. Scientific Data 2023, 10:1(10(1)), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TNFD. Global Data Facility Paper: Findings of a high-level scoping study exploring the case for a global nature-related public data facility

. 2023a. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/41335/state_.

- TNFD. Recommendations of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures

. 2023b. Available online: https://tnfd.global/tnfd-publications/.

- Tsamados, A.; Aggarwal, N.; Cowls, J.; Morley, J.; Roberts, H.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. The Ethics of Algorithms: Key Problems and Solutions. Philosophical Studies Series 2021, 144, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. J.; Jacob, D. J.; Benmergui, J.; Wofsy, S. C.; Maasakkers, J. D.; Butz, A.; Hasekamp, O.; Biraud, S. C. A large increase in U.S. methane emissions over the past decade inferred from satellite data and surface observations. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43(5), 2218–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meeteren, M.; Bassens, D. Financial geography has come of age: making space for intradisciplinary dialogue. Finance and Space 2024, 1(1), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, R.; Azizpour, H.; Leite, I.; Balaam, M.; Dignum, V.; Domisch, S.; Felländer, A.; Langhans, S. D.; Tegmark, M.; Fuso Nerini, F. The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. In Nature Communications; Nature Research, 2020; Vol. 11, Issue 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A. G. Responsible Innovation and the Innovation of Responsibility: Governing Sustainable Development in a Globalized World. Journal of Business Ethics 2017, 143(2), 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A. G.; Stahl, G. K.; Hawn, O. Grand Societal Challenges and Responsible Innovation. Journal of Management Studies 2022, 59(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schomberg, R. A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; 2013; pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N. Earth Observation for Sustainable Finance

. Satellite Applications Catapult, Internal Report Unpublished. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik, D.; Bassens, D.; Knox-Hayes, J.; Lai, K. P. Y. Revolution, evolution, progress: Finance & Space manifesto. Finance and Space 2024, 1(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young In, S.; Rook, D.; Monk, A. Integrating Alternative Data (Also Known as ESG Data) in Investment Decision Making 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Bak, I.; Cheba, K. The role of sustainable finance in achieving Sustainable Development Goals: does it work? Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2021, 27(1), 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, H.; Nelis, A. What is ELSA genomics? EMBO Reports 2009, 10(6), 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).