Introduction

Immunotherapy has become a cornerstone in the management of early TNBC [

1]. The pivotal KEYNOTE-522 trial demonstrated that combining pembrolizumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves pathological complete response (pCR) (64.8% vs 51.2%), event-free survival, and overall survival [

2]. Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 12.9% vs 1.8% of patients, with most occurring primarily during the neoadjuvant phase [

2]. Uncertainty remains regarding the benefit of continuing adjuvant pembrolizumab in this patient cohort [

3,

4,

5]. In real-world practice, such patients complete one year of treatment regardless of tumour response, exposing them to potential overtreatment and immune-related toxicity.

IrAEs are a recognised consequence of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy. In clinical trials such as KEYNOTE-522, which led to the addition of pembrolizumab to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in early TNBC, grade ≥3 irAEs occurred in approximately 13% of participants receiving pembrolizumab, with endocrine, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary events among the most common severe toxicities [

2,

3].

Real-world experience from the Neo-Real/GBECAM0123 cohort further expands this. In that study of 368 early-stage TNBC patients treated with neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, 31% of patients experienced any-grade irAEs, and 13.6% experienced grade ≥3 events overall [

3]. Most irAEs (≈73%) occurred during the neoadjuvant phase, 28.1% during the adjuvant phase, and 16% of all treated patients required permanent discontinuation of pembrolizumab due to toxicity [

3]. Endocrine toxicities were the most frequent (12.8%), followed by cutaneous (7.6%) and gastrointestinal (7.1%) events [

3].

Most irAEs affect the gastrointestinal, endocrine, skin, or lung systems; n-irAEs are uncommon, with an incidence of about 1–3% in both clinical trials and real-world settings [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. N-iraes can affect the central or peripheral nervous systems and mimic other neuromuscular disorders, leading to diagnostic delays and under-recognition. Unlike the niche populations in clinical trials, the broader real-world patient population may show toxicity patterns not seen in pivotal trials. Additionally, patients with pre-existing AI conditions, such as psoriasis, may face a higher risk of developing these irAEs [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Among n-irAEs, brachial plexopathy is exceptionally rare [

14]. Survivors of breast cancer with symptoms of new-onset ipsilateral neuropathy are initially ascribed to tumour recurrence, radiation-induced fibrosis, or surgical trauma. The management, prognosis, and survival of these differ, necessitating differentiation from immune-mediated inflammation.

Presented is a case of pembrolizumab-associated brachial plexopathy in a patient with TNBC, first suspected to be local recurrence. After thorough imaging and neurophysiological findings, the diagnosis pointed to an immune-mediated process. The patient’s poor response to corticosteroids and IVIG, followed by improvement after therapeutic plasmapheresis, highlights both the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of n-irAEs with immunotherapy.

Case Presentation

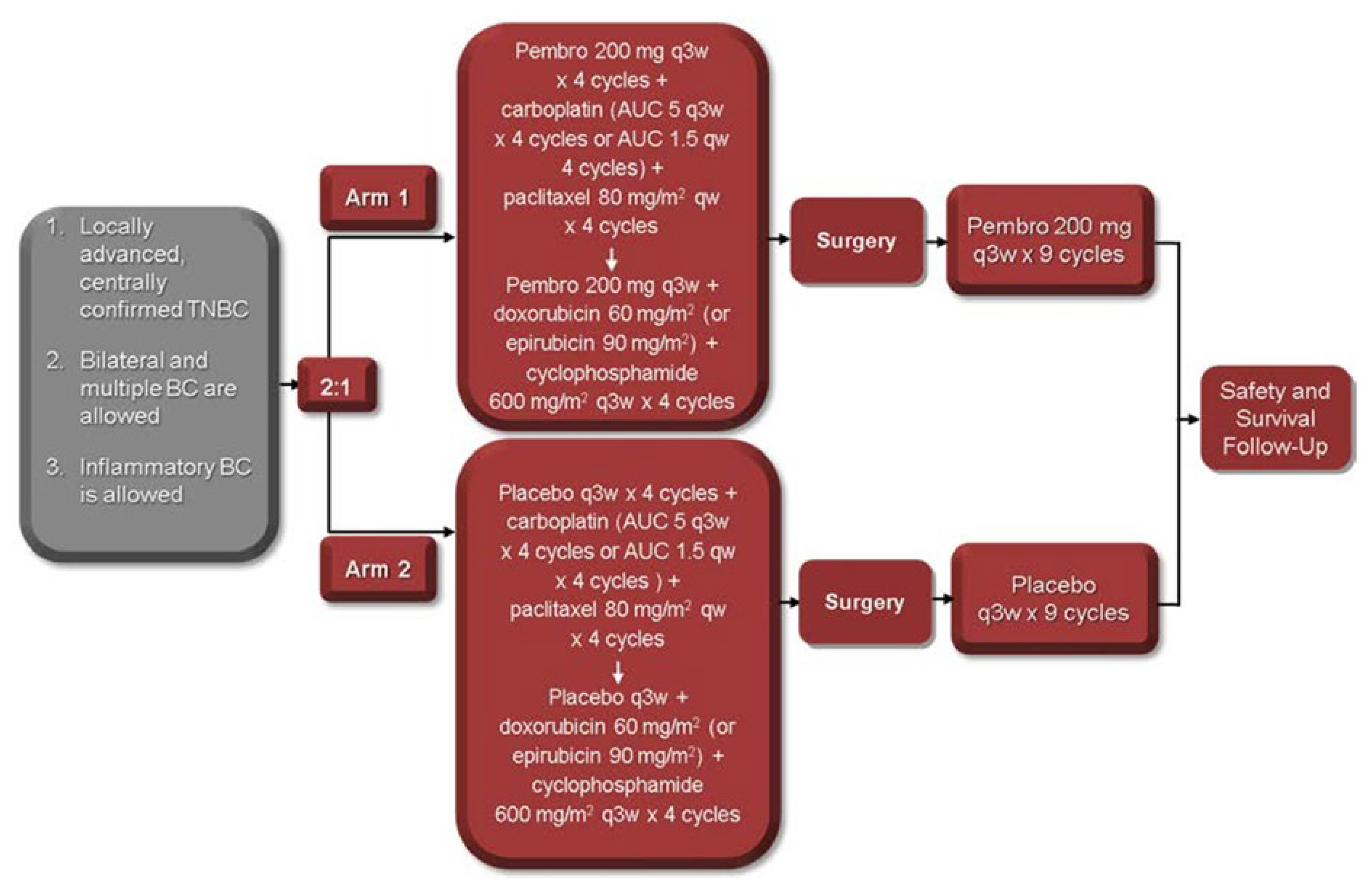

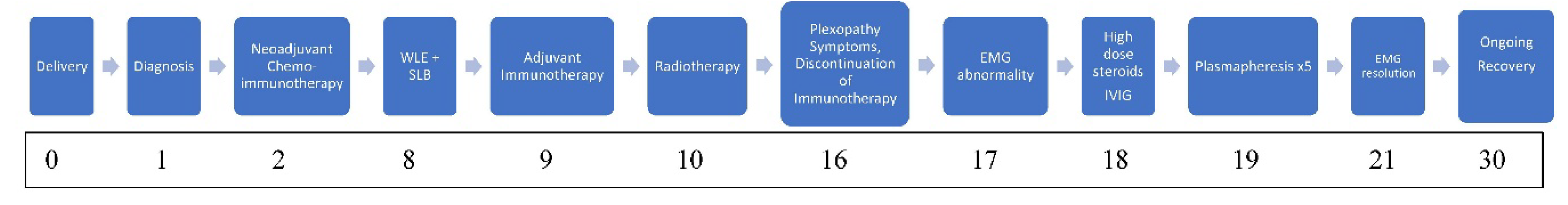

A 38-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 2, presented during the third trimester of pregnancy (39 weeks) with a palpable mass in the lower outer quadrant at the 6 o’clock position in her left breast measuring 3-4 cm. Her medical background consisted of bilateral idiopathic anterior uveitis and psoriasis (pityriasis amiantacea). Initial ultrasound suggested a benign papillary or lactational lesion. However, repeat biopsy confirmed grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma, triple-negative subtype (ER−, PR−, HER2−). Staging CT of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, including bone scan, revealed a 6.3 cm primary mass without distant metastases. Following induction of labour and delivery at 39 weeks, she commenced neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisting of weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin, followed by doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, combined with pembrolizumab in line with the KEYNOTE-522 protocol [

2]

Figure 1.

Serial clinical assessments after completion of neoadjuvant treatment demonstrated tumour softening and partial radiological response. She underwent wide local excision (WLE) and sentinel lymph node biopsy, which confirmed residual grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma (5.9 cm, ypT3 ypN0) with tumour extension into the dermis and residual cancer burden score of 3. Lymphovascular invasion was absent. Adjuvant pembrolizumab every three weeks was continued for one year, and adjuvant radiotherapy 40Gy/15fr /3 weeks to the breast and regional lymph nodes, followed by a boost to the tumour bed (breast) 13.35 Gy/5fr/1 week was delivered to the left breast and associated nodal fields.

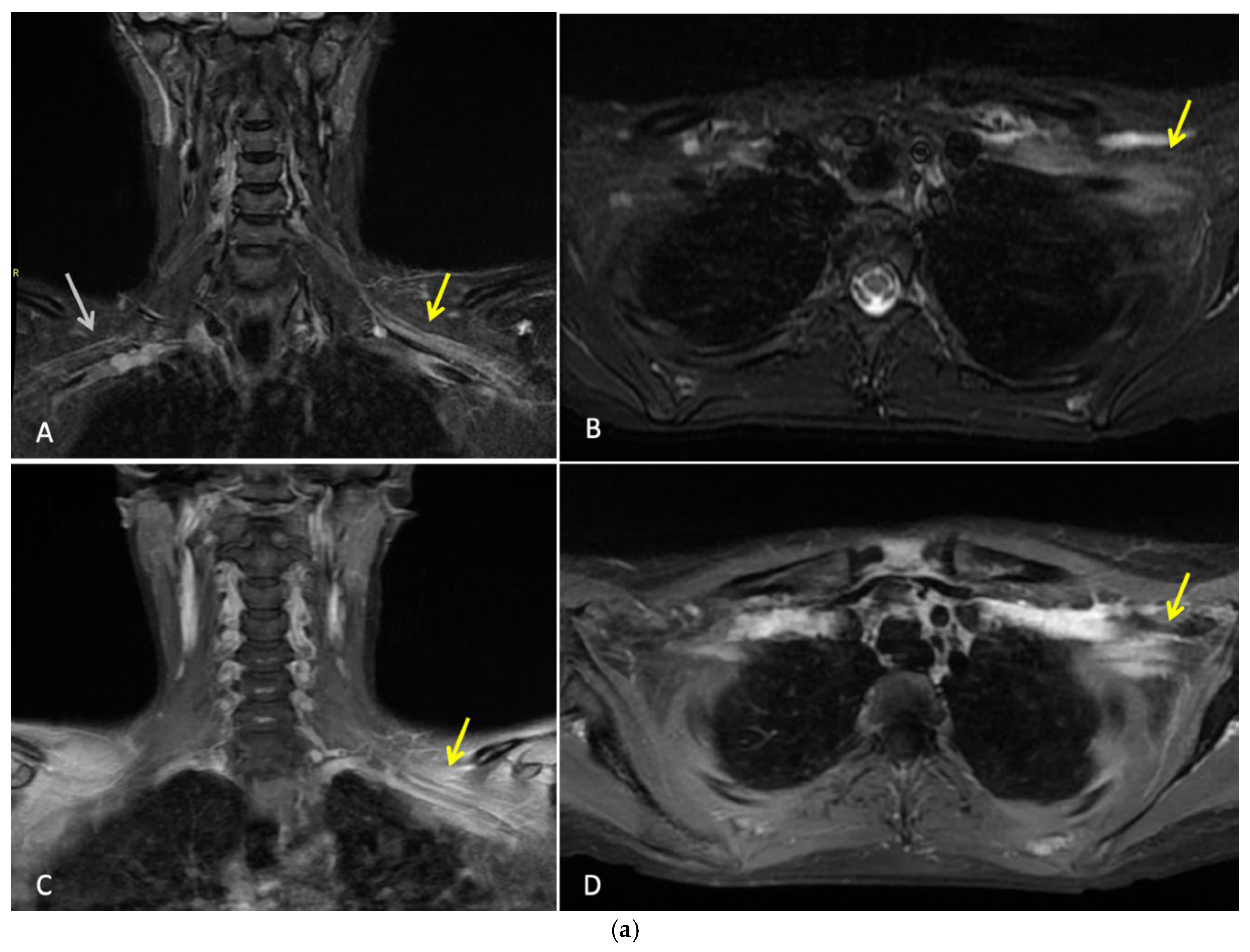

Three months after completing radiotherapy, she developed progressive numbness, paraesthesia, and weakness of the left hand. Examination revealed wasting of the thenar and hypothenar eminences, reduced grip strength, and patchy sensory loss in a C8/T1 distribution. Due to residual cancer burden after surgery, a local recurrence was initially suspected. MRI of the cervical spine and brachial plexus [

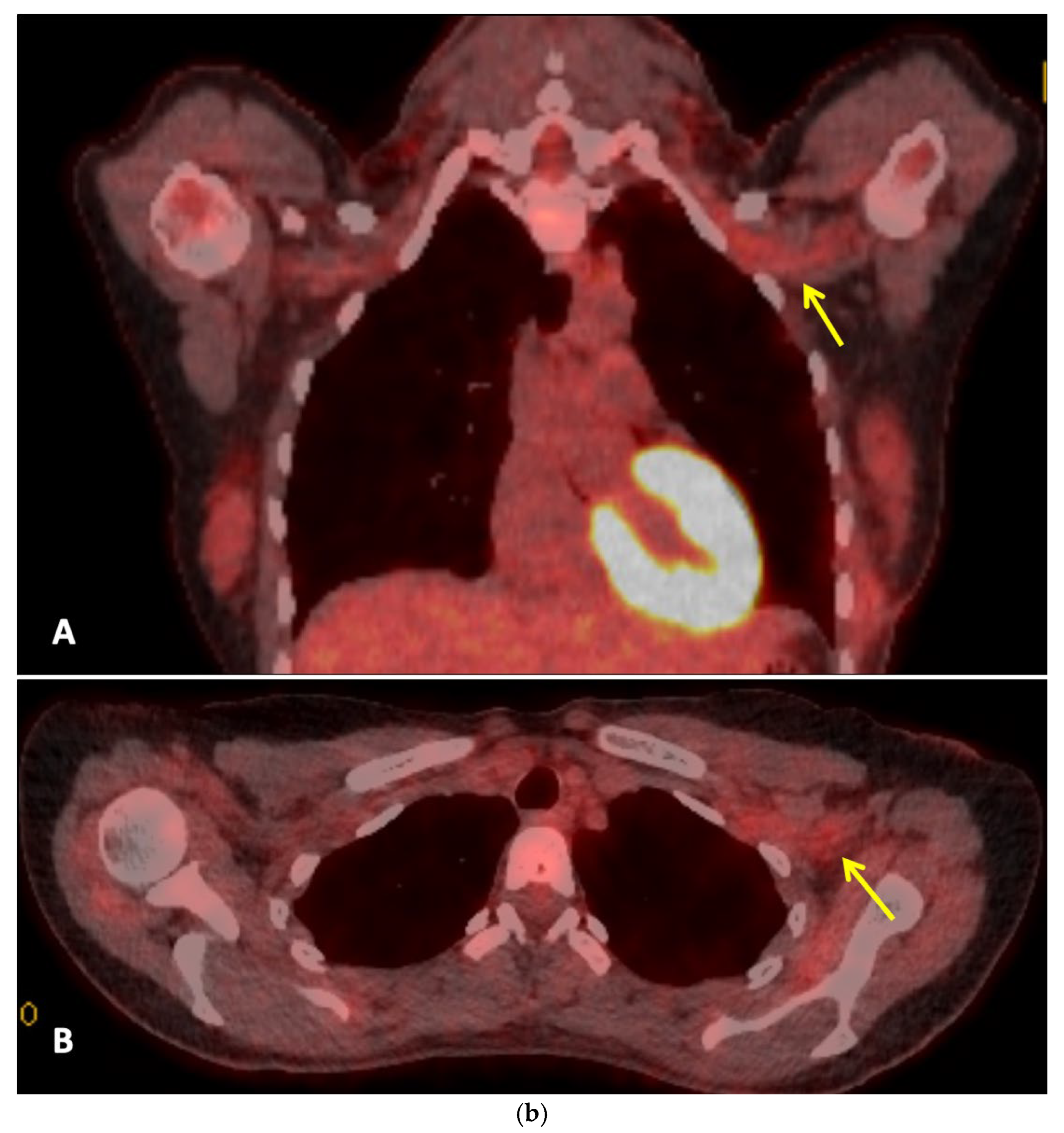

Figure 2a] did not demonstrate metastatic disease, but findings were consistent with brachial plexitis. No recurrent disease was identified on PET-CT but asymmetric low grade uptake in the left brachial plexus was also consistent with brachial plexitis [

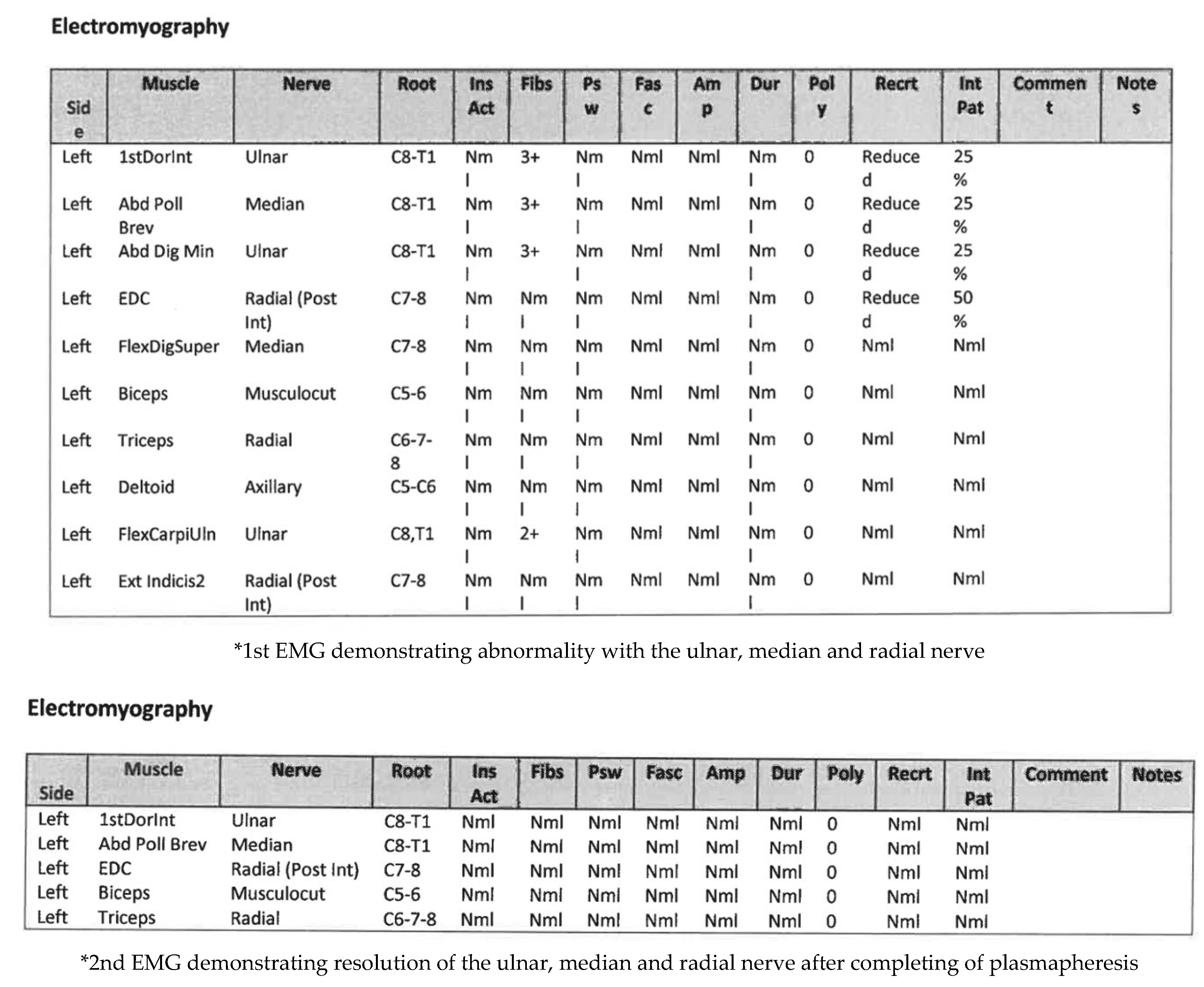

Figure 2b] confirmed absence of malignancy. Electromyography (EMG) [

Figure 3] and nerve conduction studies demonstrated denervation consistent with a lower-trunk brachial plexopathy; onconeuronal antibody serologies were negative.

Initial EMG showed abnormalities in the radial, ulnar, and median nerves, supporting the diagnosis of immune-related brachial plexopathy secondary to pembrolizumab—her first treatment involved high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone, followed by an oral taper with minimal improvement. IVIG therapy yielded partial recovery in grip strength and neuropathic pain, and fine-motor weakness. Although two lines of treatment were tried, symptoms remained functionally limiting. Therapeutic plasmapheresis (5 procedures over 5 days) was performed, resulting in further functional improvement and objective EMG recovery. A follow-up EMG demonstrated normalisation and resolution of motor and sensory conduction, confirming electrophysiological resolution of the plexopathy

Figure 3.

After three lines of treatment, she reported marked improvement in grip and dexterity with mild paraesthesia and minimal motor fatigability. Near-complete strength and sensory recovery, consistent with nerve regeneration, were evident on reassessment. She developed worsening psoriasis requiring Apremilast, a PD-4 inhibitor. The patient remains in remission 30 months post-surgery

Figure 4.

Discussion

Four major clinical challenges are presented from this case. Firstly, the newly developed ipsilateral neurological deficits closely mimicked locoregional recurrence, necessitating urgent and extensive investigation. Secondly, challenges from potentially overlapping differential diagnoses, including tumour recurrence, radiation-induced injury, paraneoplastic syndromes, and immune-mediated neuropathy. Thirdly, the patient’s neurological toxicity was unresponsive to corticosteroids, requiring escalation to IVIG and ultimately plasmapheresis. Finally, this case raises important questions regarding the real-world burden of toxicity associated with adjuvant pembrolizumab. This is particularly seen in patients with incomplete pathological response, and those with comorbidities, where therapeutic benefit is not certain and treatment-related morbidity may significantly affect long-term quality of life [

2,

3,

15,

16].

Toxicity Burden of Immunotherapy in Early TNBC

Integration of ICIs into neoadjuvant treatment algorithms for TNBC, has improved pathological complete response (pCR) rates, as demonstrated in the KEYNOTE-522 trial [

2]. However, new data emerging from real-world show a greater prevalence, severity, and persistence of irAEs than controlled clinical trials.In the Neo-Real/GBECAM0123 cohort, Andrade et al. reported that 31% of patients experienced irAEs, with 13.6% developing grade ≥3 events; notably, 28% of irAEs occurred during the adjuvant phase, and 16% of patients permanently discontinued pembrolizumab due to toxicity [

3]. Similarly, Jayan et al. reported irAEs in 34% of patients treated with the KEYNOTE-522 regimen in routine practice, with a substantial proportion requiring hospitalisation or permanent treatment cessation [

5]. These findings highlight a widening gap between trial-reported toxicity and real-world tolerability.

Several studies have shown that the development of irAEs, driven by heightened immune activation, may be parallel to improved pathological response [

16]. However, this association does not negate the risk of irreversible toxicity. This correlation in real-world practice does not justify continued treatment in patients experiencing severe or disabling toxicity. In the subset of patients who fail to achieve pCR or who develop early toxicity, the balance between treatment benefit and irreversible harm remains uncertain [

15,

17]. This highlights the urgent need for personalized, response-adapted treatment strategies and predictive biomarkers to guide continuation of immunotherapy in early TNBC [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Treatment Escalation and the Role of Plasmapheresis

N-irAE from ICI toxicity shows up in about 1–3% of patients often mimicking other neuromuscular disorders, contributing to diagnostic delay and under-recognition. Although corticosteroids remain first-line therapy, a subset of patients develop steroid-refractory disease requiring additional immunomodulatory intervention [

25,

26].

Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) is an established immunomodulatory therapy used in a range of antibody-mediated and immune-complex–driven neurological disorders [

27,

28,

29]. In the context of ICI toxicity, TPE is a valuable option in severe or refractory cases [

27,

30]. Plasmapheresis is a procedure facilitating the removal of circulating autoantibodies, immune complexes, cytokines, and potentially immune checkpoint inhibitor–drug complexes [

26,

27,

28,

31].

There is growing evidence that supports early intervention with plasmapheresis in severe n-irAEs. Katsumoto et al. reported improved neurological outcomes when TPE was implemented early in patients with steroid-refractory immune-related toxicity, suggesting a critical therapeutic window [

30]. Although largely observational, case reports and small series have demonstrated significant neurological recovery following plasmapheresis in immune-mediated neuropathies, including brachial plexopathy associated with PD-1 inhibitors [

27,

29,

30,

32]. We observed meaningful functional improvement after escalation to plasmapheresis, reinforcing its role as a rescue therapy when standard immunosuppression fails [

26,

27].

Randomized controlled data are lacking, and practical considerations—including vascular access, anticoagulation, and resource availability—must be weighed on an individual basis [

27,

28]. Alternative plasma purification techniques, such as immunoadsorption, double-filtration plasmapheresis, and cascade adsorption, offer theoretical advantages but require further evaluation for use in the IrAE setting [

26,

29,

30,

31]. Nevertheless, this case adds to the widening consensus supporting plasmapheresis as an effective rescue therapy for severe ICI-related neurological toxicity.

Right-Sizing Therapy in Early TNBC: Integrating Toxicity, Autoimmune Risk, and Benefit

KEYNOTE-522 demonstrated improved event-free survival with both neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab, the benefit from continued adjuvant therapy is not uniform across all patients, particularly in those with incomplete pathological response or early treatment-limiting toxicity [

2,

15]. Toxicity-related interruption or discontinuation can dampen therapeutic effectiveness, especially in patients with residual disease who have already demonstrated poor neoadjuvant benefit [

5,

15,

17]. Prolonging immunotherapy exposure in patients unlikely to derive incremental benefit risks irreversible morbidity, raising important survivorship concerns.

This risk may be amplified in patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease, in whom immune checkpoint inhibitors exacerbates latent immune dysregulation through heightened T-cell activation and cytokine signalling [

8,

11,

12]. Cutaneous autoimmune conditions such as psoriasis are particularly prone to flare during immunotherapy, often reflecting broader immune activation that may predispose to multi-organ toxicity [

7,

8]. In the present case, pembrolizumab exacerbated pre-existing psoriasis requiring systemic therapy. A condition which preceded the development of immune-mediated brachial plexopathy, suggesting early autoimmune destabilization may have served as a clinical harbinger of severe downstream neurotoxicity.

Patients with autoimmune disease may experience higher rates, greater severity, and increased chronicity of immune-related adverse events, frequently necessitating immunosuppression or permanent treatment discontinuation [

9,

10,

12]. In the adjuvant setting where survival benefits may be modest, the continuation of ICI exposes patients to long-term morbidity without a clear survival advantage. This points to the need for predictive tools, response-adapted strategies, and de-escalation frameworks to provide a more personalized approach. Aiming to integrate pathological response, toxicity burden, autoimmune risk, and patient preference to optimize the risk–benefit ratio of immunotherapy in early TNBC [

15,

17,

33].

Survivorship and Long-Term Supportive Care

As survival in early TNBC improves, long-term treatment-related morbidity has emerged as a key factor in an individual’s quality of life [

17]. Neurological irAEs, although rare, may result in persistent functional impairment, neuropathic pain, and reduced independence, requiring multidisciplinary care [

14,

25]. In younger patients, this can impact their employment, caregiving responsibilities, and mental health.

Survivorship care blends toxicity surveillance, rehabilitation, and supportive care into routine oncology practice, particularly for patients with immune-mediated complications [

17]. This case highlights prioritisation of quality of survival and disease control. Also, reinforcing the importance of early recognition and aggressive management of rare toxicities.

Conclusions

In summary, this case demonstrates how immune-mediated plexopathy can mimic recurrence and the therapeutic efficacy of plasmapheresis in refractory neuro-irAEs. As immunotherapy becomes interwoven into early TNBC care, identifying predictive biomarkers and tailoring response-adapted regimens will be key to optimising survival and quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: Toluwalogo Baiyewun, Seamus O’Reilly. Data Curation: Alex Bryan, Julie Twomey, Toluwalogo Baiyewun, and Seamus O’Reilly. Writing- original draft: Toluwalogo Baiyewun, Seamus O’Reilly. Writing Review and Editing: Toluwalogo Baiyewun, Brian McNamara, Emily Aherne, Alex Bryan, Julie Twomey, Sorcha NiLoingsigh, Aisling O’Connell, Bola Ofi, Derek Power, Seamus O’Reilly. Supervision: Toluwalogo Baiyewun, Seamus O’Reilly. Project administration: All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financial support of Cancer Trials Cork at Cancer Research@UCC, Cork University Hospital/University College Cork, Cancer Centre is gratefully acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this work because case reports are not subject to the “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects case report”.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient provided written informed consent for publication including the use of de-identified clinical information and images.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient for allowing us to publish this case.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| TNBC |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

| N-IrAEs |

Neurological immune related adverse events |

| IrAEs |

Immune-related adverse events |

| AI |

Autoimmune |

| IVIG |

Intravenous immunoglobulin |

| ICI |

Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| RIBP |

Radiation-induced brachial plexopathy |

| TPE |

Therapeutic plasma exchange |

References

- Loibl, S.; André, F.; Bachelot, T.; Barrios, C. H.; Bergh, J.; Burstein, H. J.; Cardoso, M. J.; Carey, L. A.; Dawood, S.; Del Mastro, L.; Denkert, C.; Fallenberg, E. M.; Francis, P. A.; Gamal-Eldin, H.; Gelmon, K.; Geyer, C. E.; Gnant, M.; Guarneri, V.; Gupta, S.; Harbeck, N. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35(2), 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P; Cortes, J; Pusztai, L; McArthur, H; Kümmel, S; Bergh, J; Denkert, C; Park, YH; Hui, R; Harbeck, N; Takahashi, M; Foukakis, T; Fasching, PA; Cardoso, F; Untch, M; Jia, L; Karantza, V; Zhao, J; Aktan, G; Dent, R; O’Shaughnessy, J. KEYNOTE-522 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020, 382(9), 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, MO; Gutierres, IG; Tavares, MC; de Sousa, IM; Balint, FC; Marin Comini, AC; Gouveia, MC; Bines, J; Madasi, F; Ferreira, RDP; Rosa, DD; Santos, CL; Assad-Suzuki, D; de Souza, ZS; de Araújo, JAP; de Melo Gagliato, D; Dos Anjos, CH; Zucchetti, BM; Ferrari, A; de Brito, ML; Cangussu, R; Fernandes Monteiro, MM; Hoff, PM; Del Pilar Estevez-Diz, M; Testa, L; Barroso-Sousa, R; Bonadio, RC. Immune-related adverse events among patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer treated with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy: real-world data from the Neo-Real/GBECAM 0123 study. Breast 2025, 83, 104473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jayan, A; Sukumar, JS; Fangman, B; Patel, T; Raghavendra, AS; Liu, D; Pasyar, S; Rauch, R; Basen-Engquist, K; Tripathy, D; Wang, Y; Khan, SS; Barcenas, CH. Real-World Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients With Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Who Received Pembrolizumab. JCO Oncol Pract. 2025, 21, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jayan, A; Sukumar, JS; Fangman, B; Patel, T; Raghavendra, AS; Liu, D; Pasyar, S; Rauch, R; Basen-Engquist, K; Tripathy, D; Wang, Y; Khan, SS; Barcenas, CH. Real-World Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients With Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Who Received Pembrolizumab. JCO Oncol Pract. 2025, 21, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katsumoto, TR; Wilson, KL; Giri, VK; Zhu, H; Anand, S; Ramchandran, KJ; Martin, BA; Yunce, M; Muppidi, S. Plasma exchange for severe immune-related adverse events from checkpoint inhibitors: an early window of opportunity? Immunother Adv 2022, 2, ltac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Le, J; Sun, Y; Deng, G; Dian, Y; Xie, Y; Zeng, F. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients with autoimmune disease: Safety and efficacy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2025, 21, 2458948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tison, A.; Garaud, S.; Chiche, L.; et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor use in patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022, 18, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Li, S; Ke, L; Cui, H. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in Cancer patients with rheumatologic preexisting autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24(1), 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tison, A; Quéré, G; Misery, L; Funck-Brentano, E; Danlos, FX; Routier, E; Robert, C; Loriot, Y; Lambotte, O; Bonniaud, B; Scalbert, C; Maanaoui, S; Lesimple, T; Martinez, S; Marcq, M; Chouaid, C; Dubos, C; Brunet-Possenti, F; Stavris, C; Chiche, L; Beneton, N; Mansard, S; Guisier, F; Doubre, H; Skowron, F; Aubin, F; Zehou, O; Roge, C; Lambert, M; Pham-Ledard, A; Beylot-Barry, M; Veillon, R; Kramkimel, N; Giacchero, D; De Quatrebarbes, J; Michel, C; Auliac, JB; Gonzales, G; Decroisette, C; Le Garff, G; Carpiuc, I; Vallerand, H; Nowak, E; Cornec, D; Kostine, M. Groupe de Cancérologie Cutanée, Groupe Français de Pneumo-Cancérologie, and Club Rhumatismes et Inflammations. Safety and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Patients With Cancer and Preexisting Autoimmune Disease: A Nationwide, Multicenter Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019, 71(12), 2100–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y; Zhou, Y; Zhang, X; Tan, K; Zheng, J; Li, J; Cui, H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Treatment of Patients With Cancer and Preexisting Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 934093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Halle, BR; Betof Warner, A; Zaman, FY; Haydon, A; Bhave, P; Dewan, AK; Ye, F; Irlmeier, R; Mehta, P; Kurtansky, NR; Lacouture, ME; Hassel, JC; Choi, JS; Sosman, JA; Chandra, S; Otto, TS; Sullivan, R; Mooradian, MJ; Chen, ST; Dimitriou, F; Long, G; Carlino, M; Menzies, A; Johnson, DB; Rotemberg, VM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with pre-existing psoriasis: safety and efficacy. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9, e003066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wan, Z; Huang, J; Ou, X; Lou, S; Wan, J; Shen, Z. Psoriasis de novo or exacerbation by PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. An Bras Dermatol 2024, 99(3), 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rossi, S; Gelsomino, F; Rinaldi, R; Muccioli, L; Comito, F; Di Federico, A; De Giglio, A; Lamberti, G; Andrini, E; Mollica, V; D’Angelo, R; Baccari, F; Zenesini, C; Madia, P; Raschi, E; Cortelli, P; Ardizzoni, A; Guarino, M. Peripheral nervous system adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Neurol. 2023, 270, 2975–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krishnan, J; Patel, A; Roy, AM; Alharbi, M; Kapoor, A; Yao, S; Khoury, T; Hong, CC; Held, N; Chakraborty, A; Kaliniski, P; Salman, A; Catalfamo, K; Attwood, K; Kirtani, V; Shaikh, SS; Chaudhary, LN; Gandhi, S. Detrimental Impact of Chemotherapy Dose Reduction or Discontinuation in Early Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treated With Pembrolizumab and Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Multicenter Experience. Clin Breast Cancer 2024, 24, e701–e711.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marhold, M; Udovica, S; Halstead, A; Hirdler, M; Ferner, M; Wimmer, K; Bago-Horvath, Z; Exner, R; Fitzal, F; Strasser-Weippl, K; Robinson, T; Bartsch, R. Emergence of immune-related adverse events correlates with pathological complete response in patients receiving pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2275846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Reilly, S; Gaynor, S; Mayer, EL. Oncology’s ongoing struggle with evaluating quality of life limiting, treatment-related toxicity. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildiers H, Adam V, O’Reilly S, et al. Enhancing Clinical Cancer Research Through Sharing of Data and Biospecimens. JAMA Oncol. Published online December 18, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, ND; Dhande, R; Parihar, P; Bora, N. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Radiation-Induced Brachial Plexopathy. Cureus 2024, 16, e60067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Im, YJ; Yoon, YC; Sung, DH. Brachial plexopathy due to perineural tumor spread: a retrospective single-center experience of clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatments, and outcomes. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2024, 166(1), 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosa, A; Brogan, DM; Dy, CJ. Radiation Plexopathy. J Hand Surg Am 2025, 50, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratosa, I; Montero, A; Ciervide, R; Alvarez, B; García-Aranda, M; Valero, J; Chen-Zhao, X; Lopez, M; Zucca, D; Hernando, O; Sánchez, E; de la Casa, MA; Alonso, R; Fernandez-Leton, P; Rubio, C. Ultra-hypofractionated one-week locoregional radiotherapy for patients with early breast cancer: Acute toxicity results. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2024, 46, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chomchai, T; Klunklin, P; Tongprasert, S; Kanthawang, T; Toapichattrakul, P; Chitapanarux, I. Is there any radiation-induced brachial plexopathy after hypofractionated postmastectomy radiotherapy with helical tomotherapy? Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1392313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Waeldner, K; Chin, C; Gilbo, P. Severe Radiation-Induced Brachial Plexopathy: A Case Report on Radiation Toxicity in a Patient With Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. Cureus 2024, 16, e73043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramos-Casals, M; Brahmer, JR; Callahan, MK; Flores-Chávez, A; Keegan, N; Khamashta, MA; Lambotte, O; Mariette, X; Prat, A; Suárez-Almazor, ME. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haugh, AM; Probasco, JC; Johnson, DB. Neurologic complications of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2020, 19, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Onwuemene, OA; Nnoruka, CI; Patriquin, CJ; Connelly-Smith, LS. Therapeutic plasma exchange in the management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated immune-related adverse effects: A review. Transfusion 2022, 62, 2370–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altobelli, C; Anastasio, P; Cerrone, A; Signoriello, E; Lus, G; Pluvio, C; Perna, AF; Capasso, G; Simeoni, M; Capolongo, G. Therapeutic Plasmapheresis: A Revision of Literature. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2023, 48(1), 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacob, S; Mazibrada, G; Irani, SR; Jacob, A; Yudina, A. The Role of Plasma Exchange in the Treatment of Refractory Autoimmune Neurological Diseases: a Narrative Review. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2021, 16, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katsumoto, TR; Wilson, KL; Giri, VK; Zhu, H; Anand, S; Ramchandran, KJ; Martin, BA; Yunce, M; Muppidi, S. Plasma exchange for severe immune-related adverse events from checkpoint inhibitors: an early window of opportunity? Immunother Adv 2022, 2, ltac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rajabally, YA. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy: Current Therapeutic Approaches and Future Outlooks. Immunotargets Ther 2024, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alhammad, RM; Dronca, RS; Kottschade, LA; Turner, HJ; Staff, NP; Mauermann, ML; Tracy, JA; Klein, CJ. Brachial Plexus Neuritis Associated With Anti-Programmed Cell Death-1 Antibodies: Report of 2 Cases. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2017, 1, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wildiers H, Adam V, O’Reilly S, et al. Enhancing Clinical Cancer Research Through Sharing of Data and Biospecimens. JAMA Oncol. Published online December 18, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Marhold, M; Udovica, S; Halstead, A; Hirdler, M; Ferner, M; Wimmer, K; Bago-Horvath, Z; Exner, R; Fitzal, F; Strasser-Weippl, K; Robinson, T; Bartsch, R. Emergence of immune-related adverse events correlates with pathological complete response in patients receiving pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2275846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shen, X; Yang, J; Qian, G; Sheng, M; Wang, Y; Li, G; Yan, J. Treatment-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1391724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jayan, A; Sukumar, JS; Fangman, B; Patel, T; Raghavendra, AS; Liu, D; Pasyar, S; Rauch, R; Basen-Engquist, K; Tripathy, D; Wang, Y; Khan, SS; Barcenas, CH. Real-World Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients With Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Who Received Pembrolizumab. JCO Oncol Pract. 2025, 21(9), 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rached, L. Real-world safety and effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy combination with pembrolizumab in triple-negative breast cancer. ESMO Real World Data and Digital Oncology Volume 5, 100061. [CrossRef]

- Katsumoto, Tamiko R; Wilson, Kalin L; Giri, Vinay K; Zhu, Han; Anand, Shuchi; Ramchandran, Kavitha J; Martin, Beth A; Yunce, Muharrem; Muppidi, Srikanth. Plasma exchange for severe immune-related adverse events from checkpoint inhibitors: an early window of opportunity? Immunotherapy Advances 2022, Volume 2(Issue 1), ltac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Marleen. Academic Uphill Battle to Personalize Treatment for Patients With Stage II/III Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 3523–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavropoulou, MP; Anastasilakis, DA; Kasdagli, M; Gialouri, CG; Palaiopanos, K; Fountas, A; et al. Incidence of fractures in patients with solid cancers treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Oncology 2025, 4, e000868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, G.; Cascone, T.; van der Heijden, M.S.; et al. The rapidly evolving paradigm of neoadjuvant immunotherapy across cancer types. Nat Cancer 2025, 6, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, S.; Gaynor, S.; Mayer, E.L. Oncology’s ongoing struggle with evaluating quality of life limiting, treatment-related toxicity. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Bryan J.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2021, 39, 4073–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).