Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Generation of Floor Plate Cells (FPCs) from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

2.3. Cell Culture & Transfection and LRRK2 Inhibitor Treatments

2.4. Semiquantitative RT-PCR

2.5. Immunophenotyping

2.6. Immunocytochemistry

2.7. Immunoblotting

2.8. Measurement of Membrane Fluidity

2.9. Quantification of Membrane Cholesterol

2.10. Quantification of Cellular Dopamine Uptake

2.11. Atomic Force Microscopy

2.12. Membrane Lipid Extraction

2.13. LC-MS/MS Protocol

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

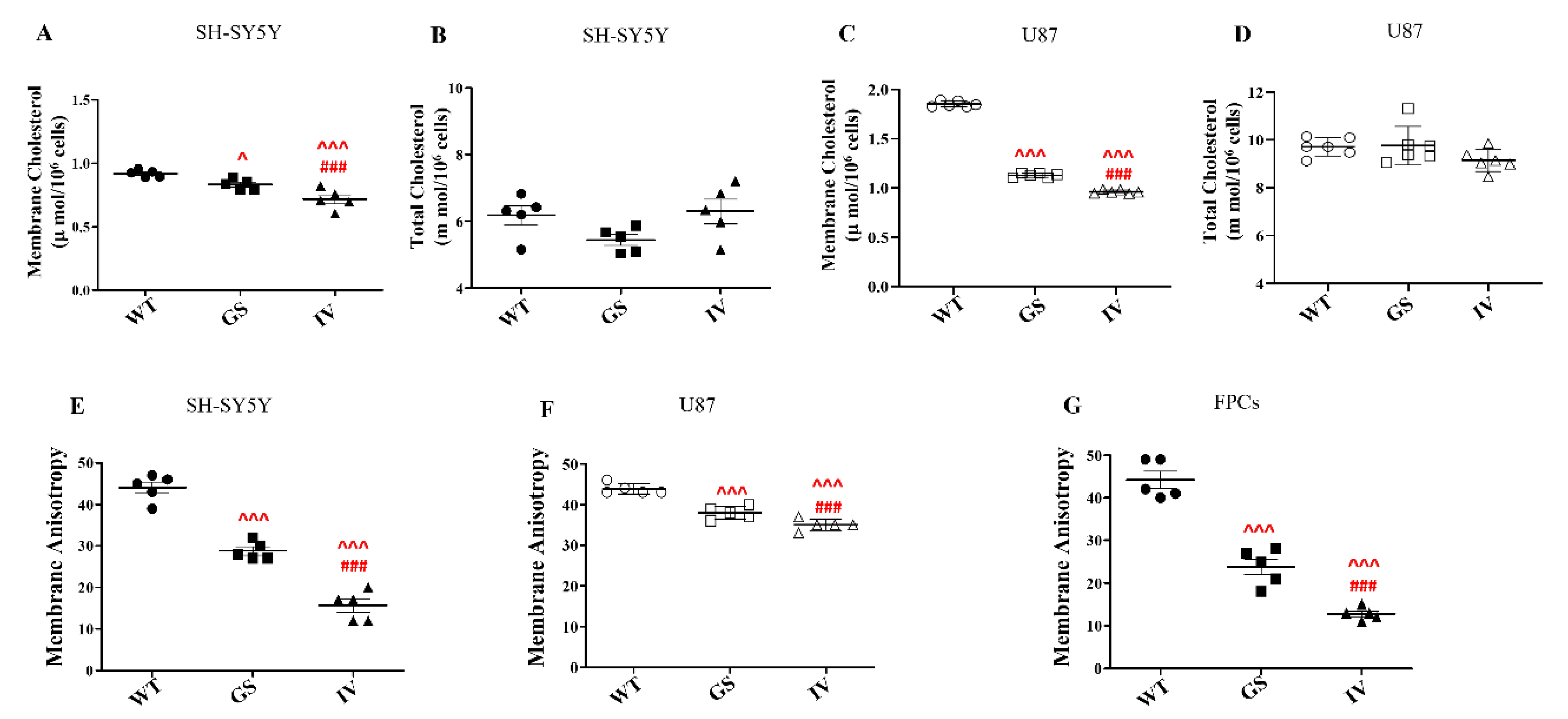

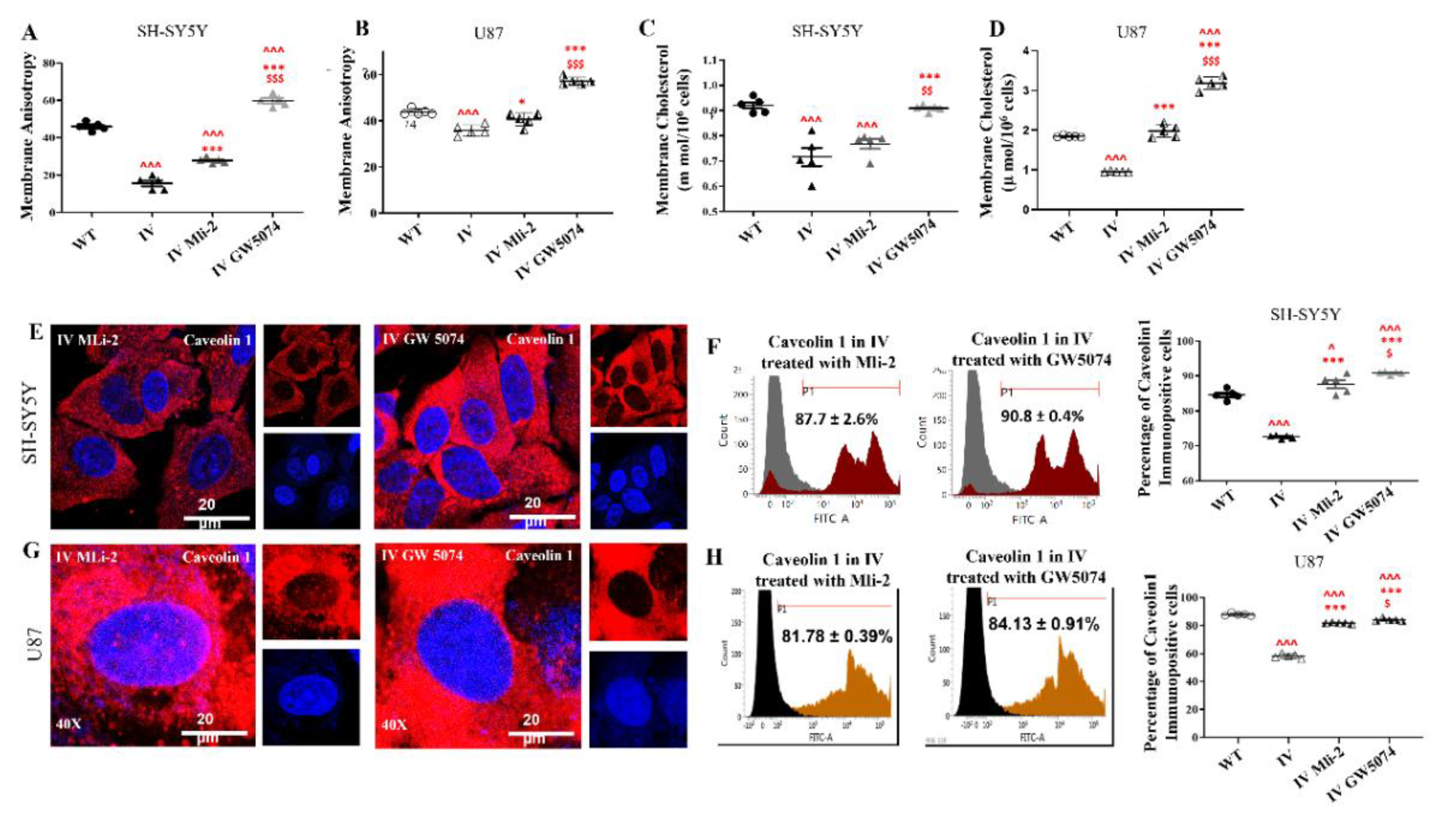

3.1. Differential Effect of LRRK2 Genetic Variants, G2019S and I1371V, on Membrane Cholesterol and Membrane Fluidity

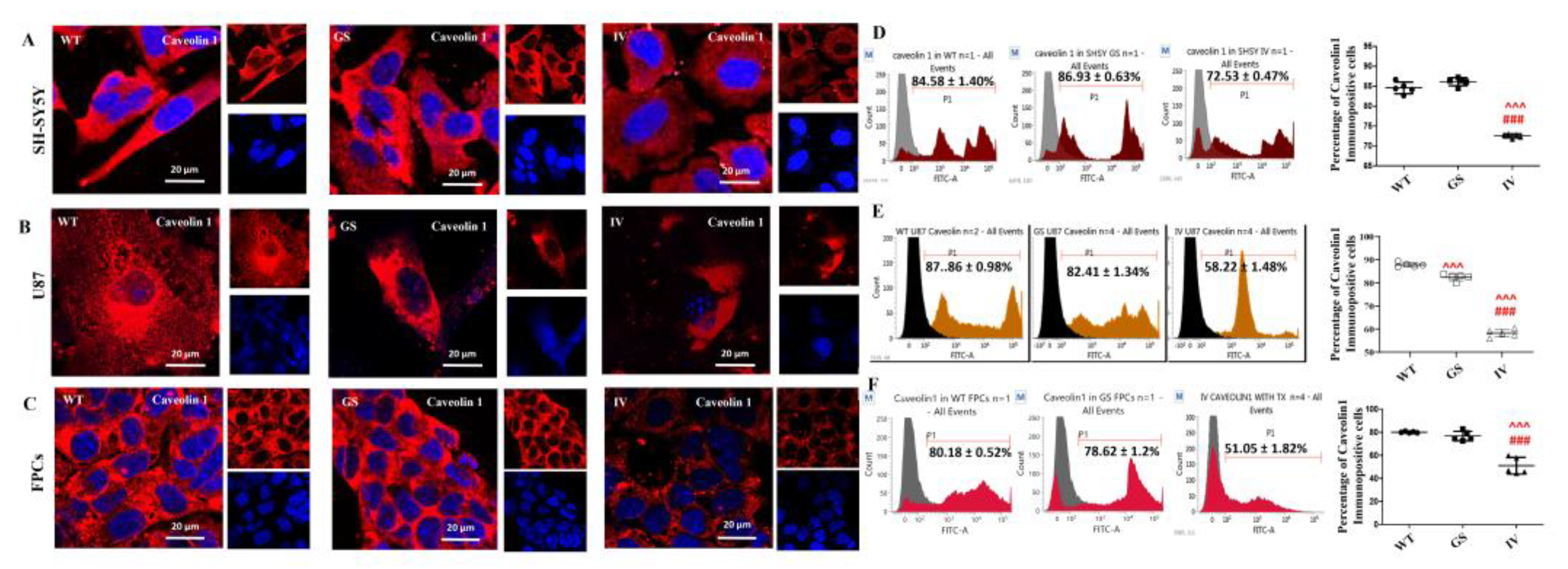

3.2. Differential Effect of LRRK2 Genetic Variants, G2019S and I1371V, on Cell-Surface Expression of Caveolin 1

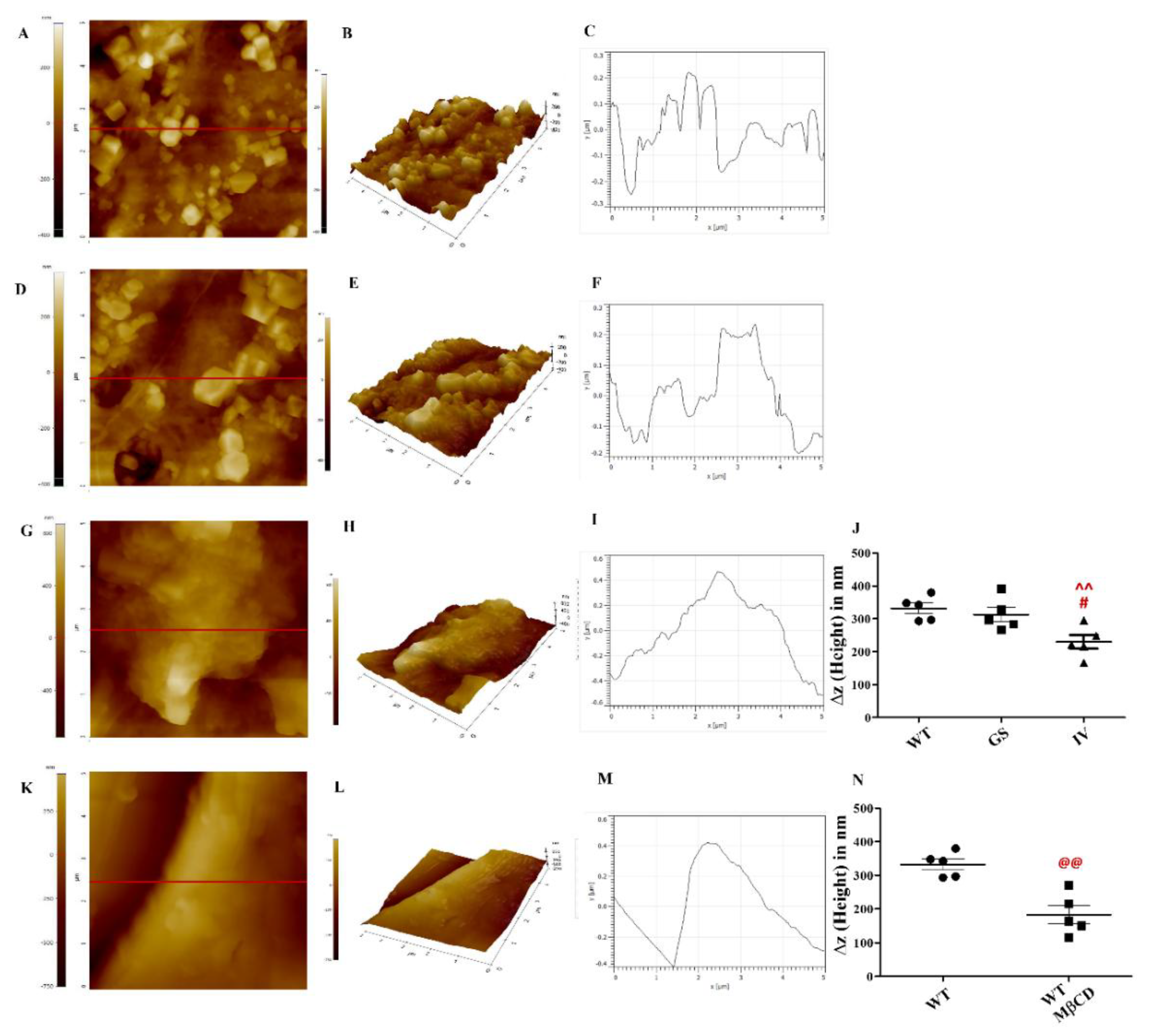

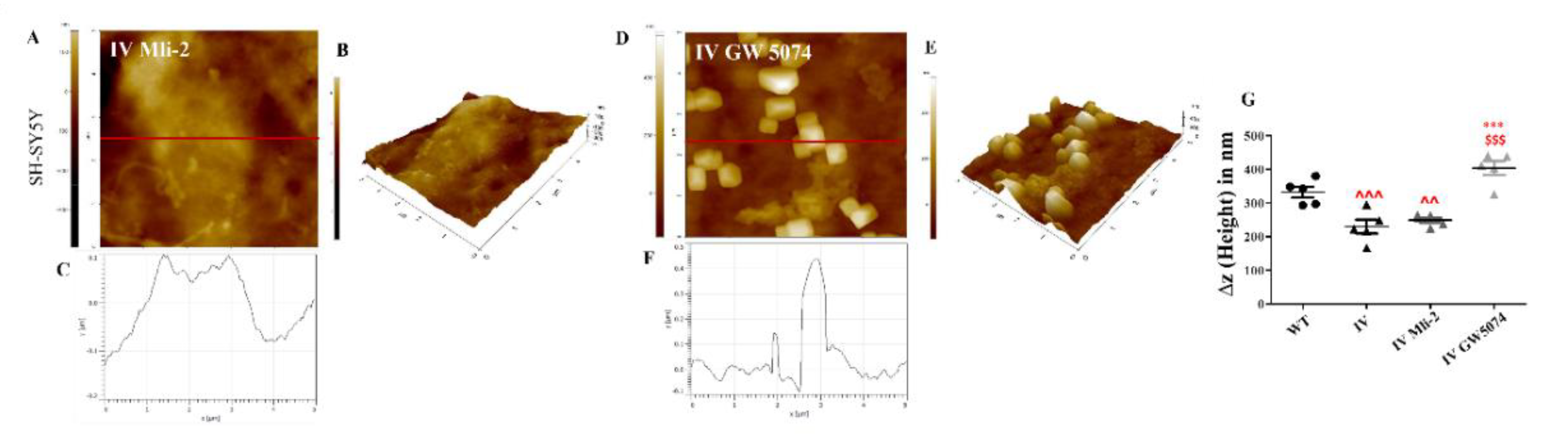

3.3. Differential Effect of LRRK2 Genetic Variants, G2019S and I1371V, on Plasma Membrane Topology

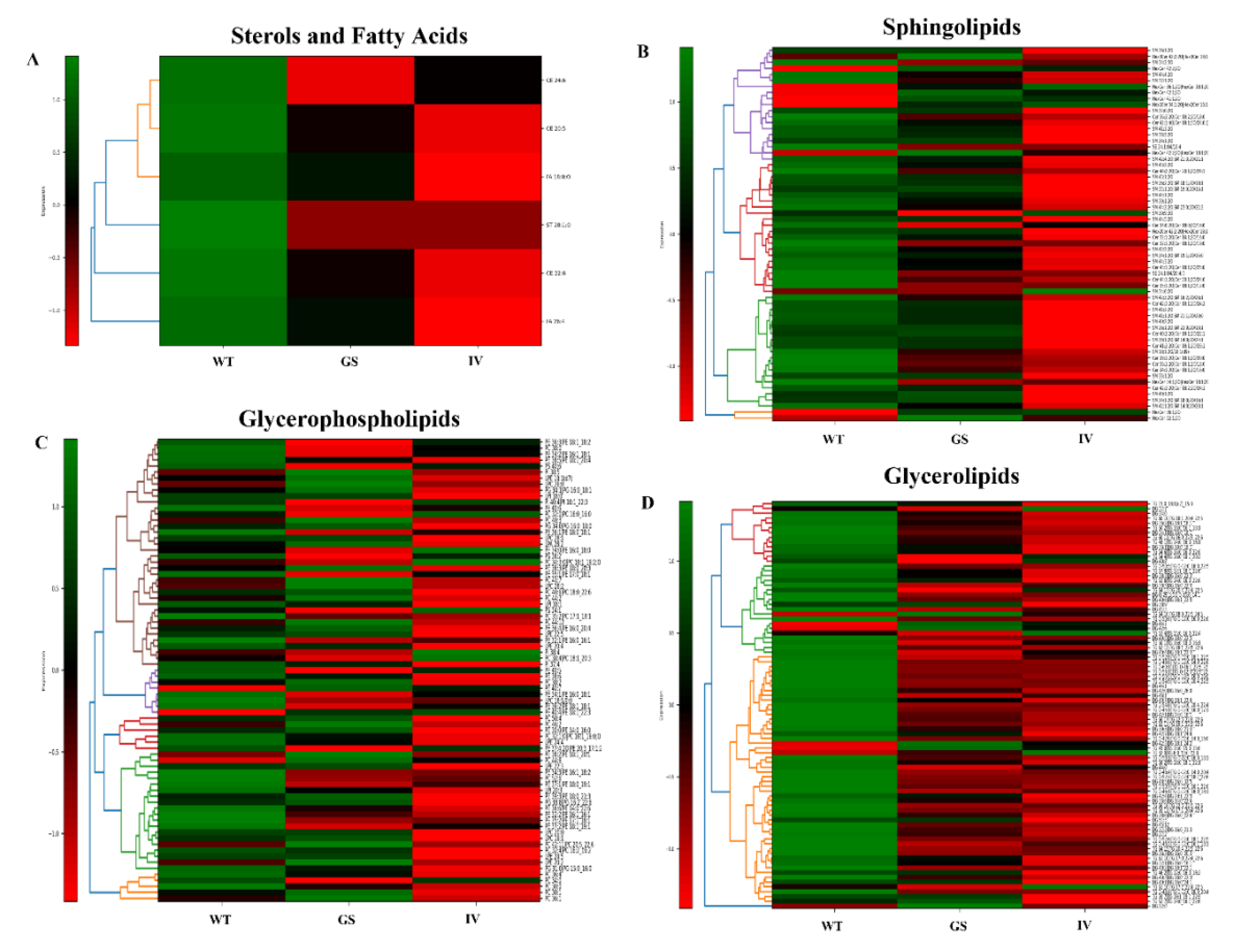

3.4. Altered Membrane Lipid Composition in LRRK2 Mutant Transfected SH-SY5Y Cells

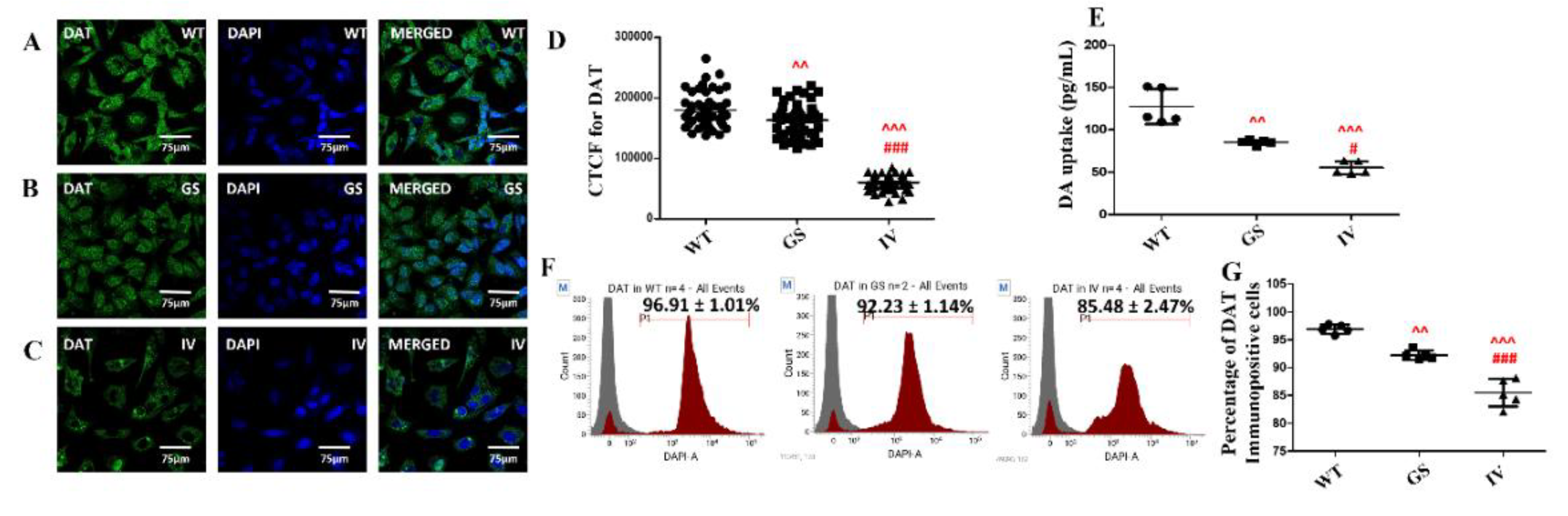

3.5. Differential Effect of LRRK2 Genetic Variants, G2019S and I1371V, on cell-Surface Expression of DAT and Dopamine Uptake

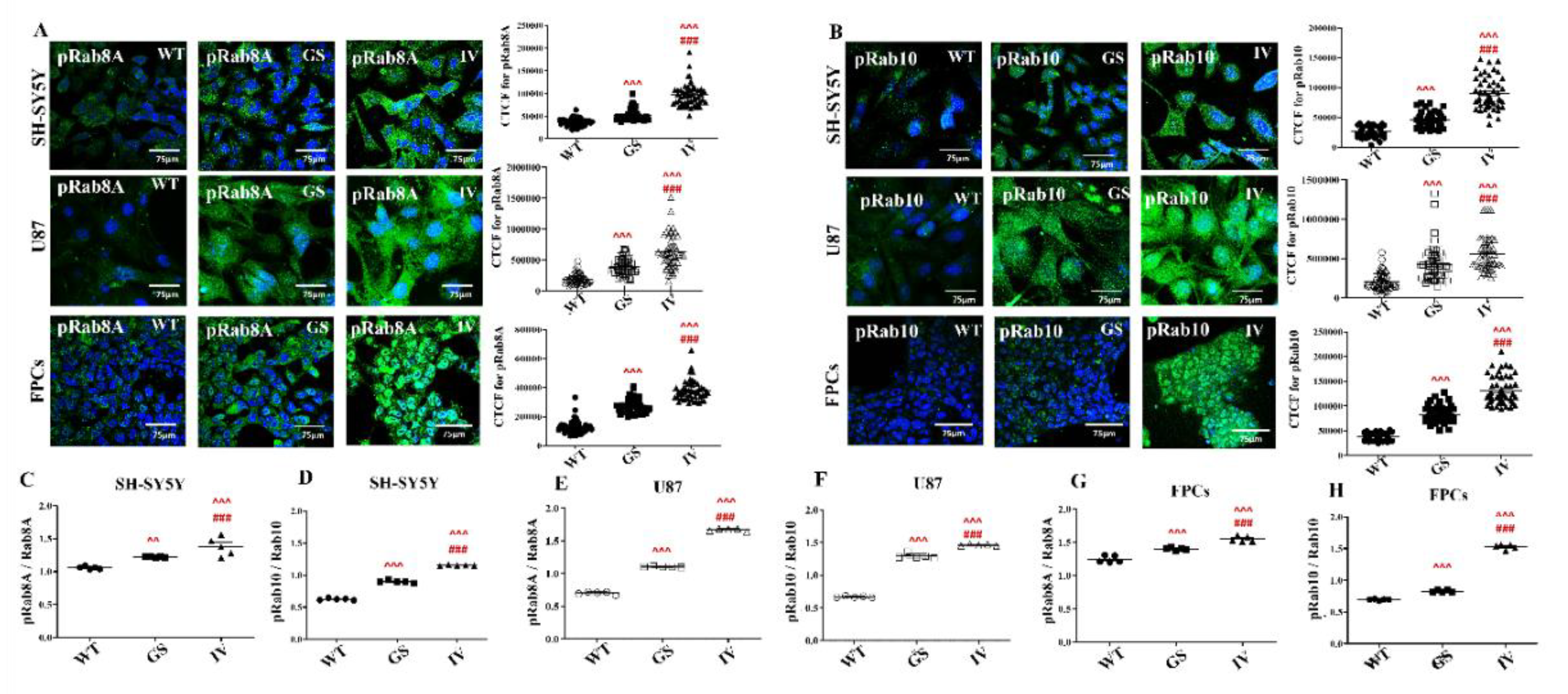

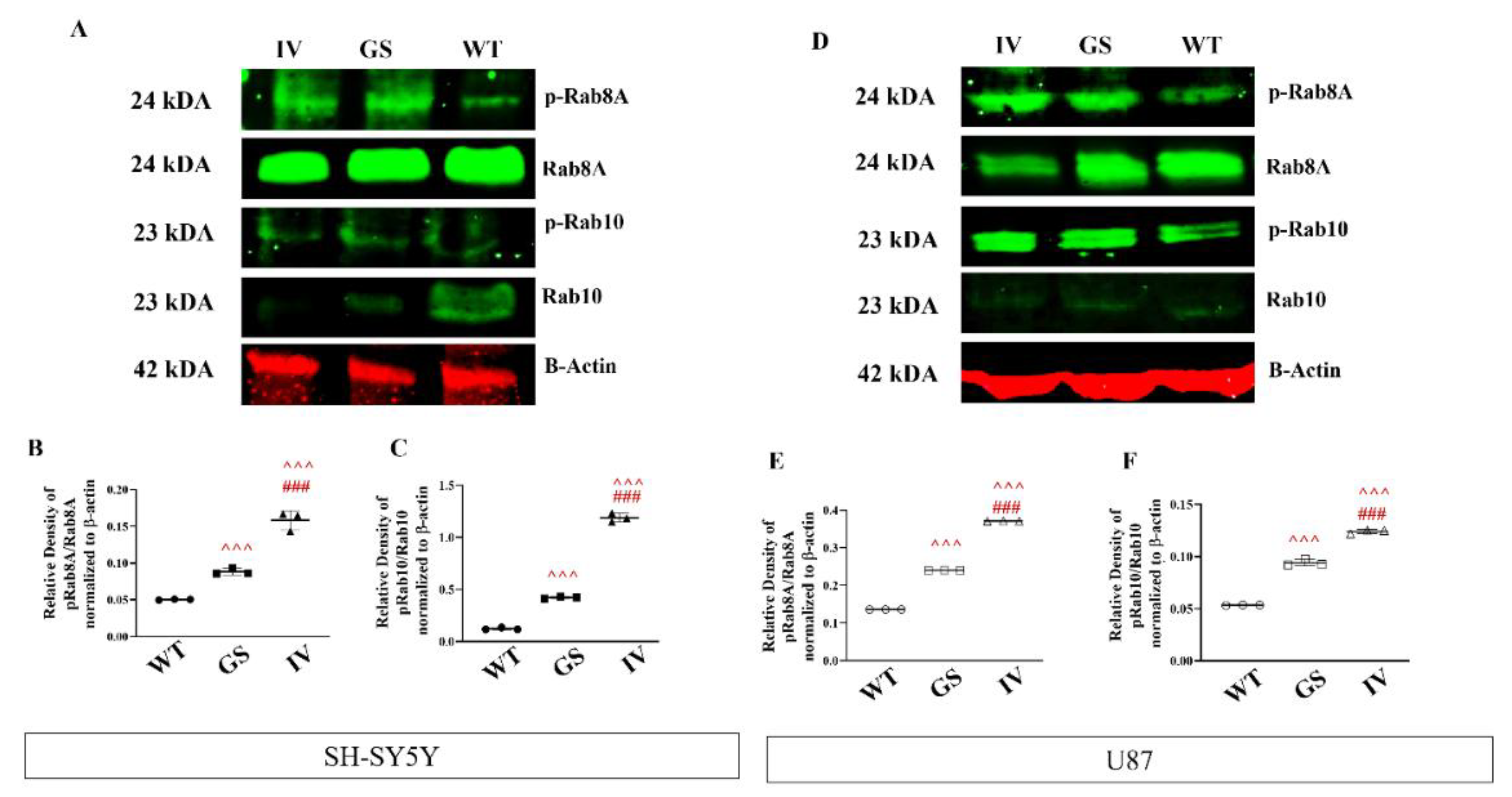

3.6. Differential Effects of G2019S and I1371V Variants on LRRK2 Substrate Phosphorylation

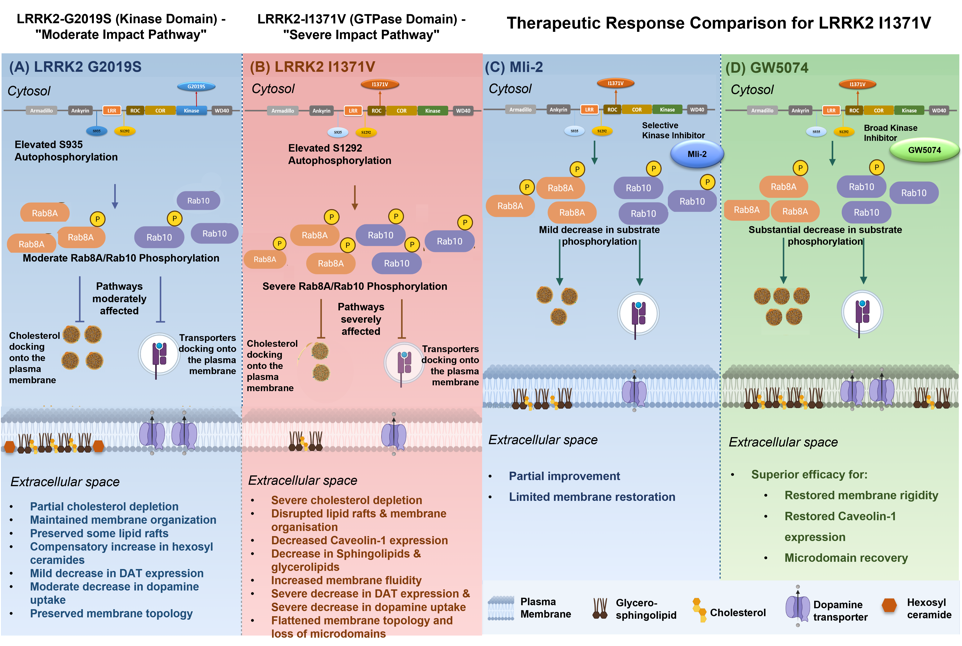

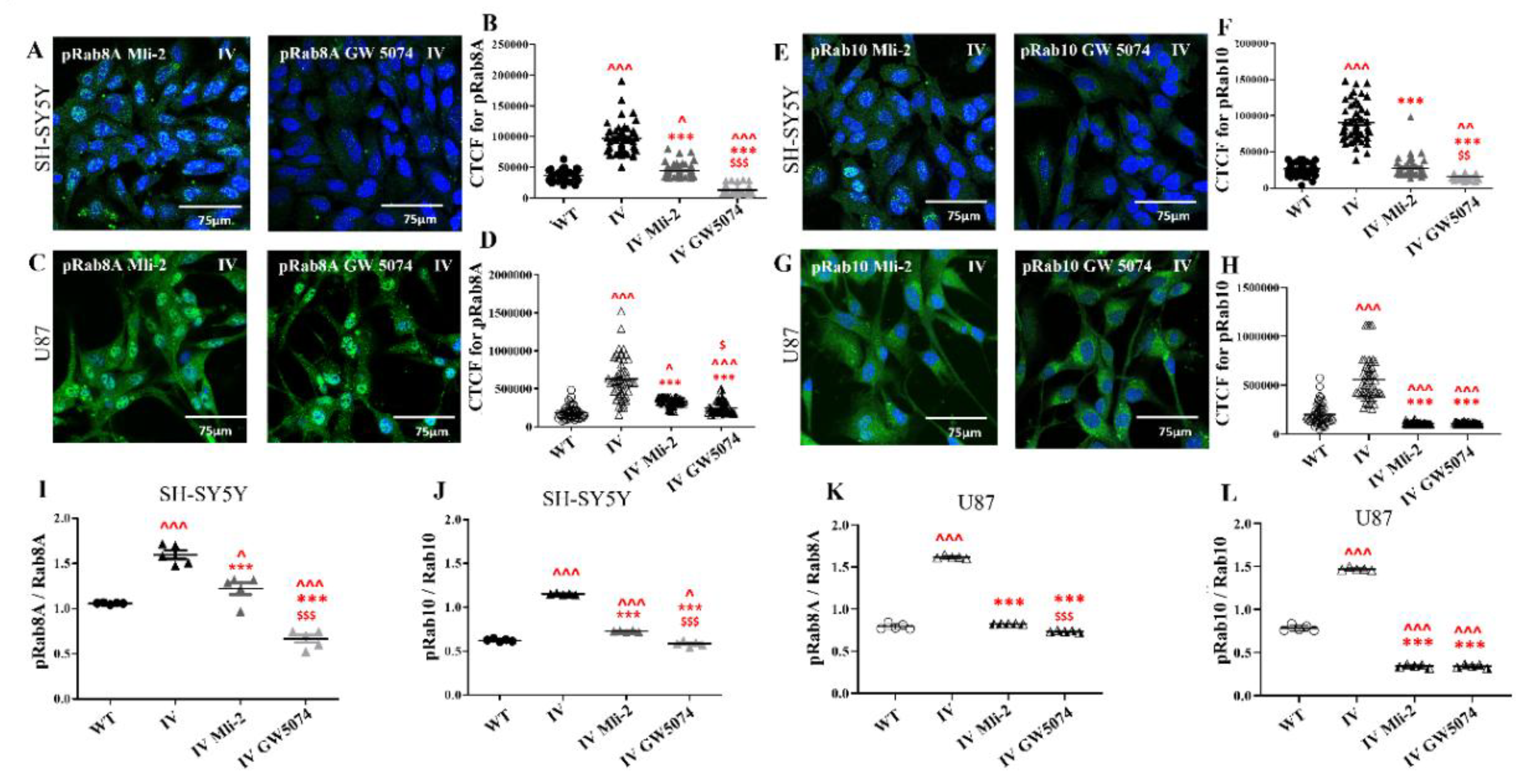

3.7. Differential Response of LRRK2 I1371V Transfected Cells to LRRK2 Inhibitors on Rab8A and Rab10 Phosphorylation

3.8. Differential Response of LRRK2 I1371V Transfected Cells to LRRK2 Inhibitors on Membrane Fluidity, Expression of Caveolin1 and Membrane Topology

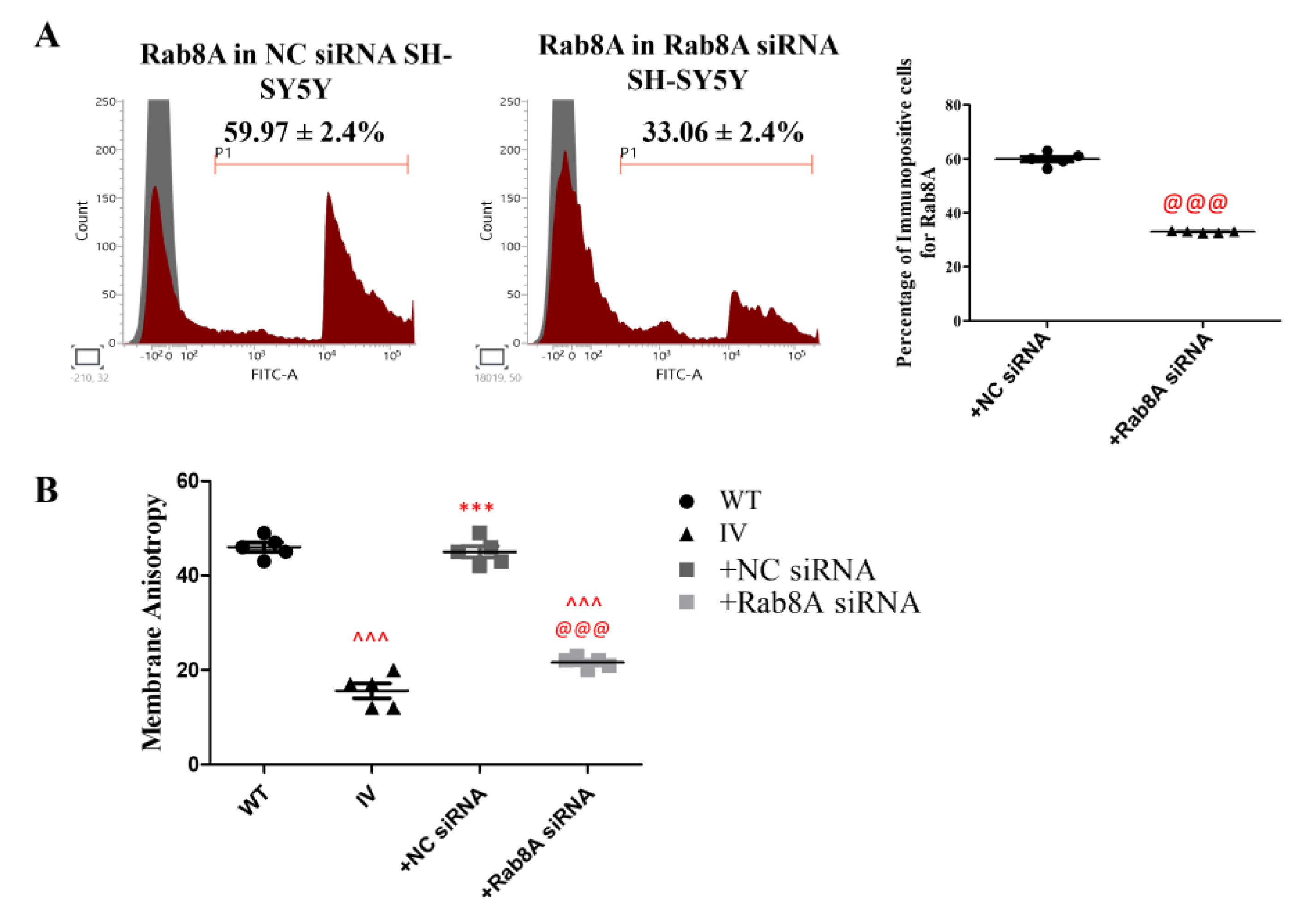

3.9. Rab8A Silencing Alters Membrane Fluidity in SH-SY5Y Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paisán-Ruíz, C., Lang, A.E., Kawarai, T., Sato, C., Salehi-Rad, S., Fisman, G.K., Al-Khairallah, T., St George-Hyslop, P., Singleton, A., Rogaeva, E. (2005). LRRK2 gene in Parkinson disease: Mutation analysis and case-control association study. Neurology 65, 696–700. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, J., Zeldenrust, F.M.J., Huang, J., Kasten, M., Schaake, S., Petkovic, S., Madoev, H., Grünewald, A., Almuammar, S., König, I.R., et al. (2018). Genotype-phenotype relations for the Parkinson’s disease genes SNCA, LRRK2, VPS35: MDSGene systematic review. Movement Disorders 33, 1857–1870. [CrossRef]

- Shu, L., Zhang, Y., Sun, Q., Pan, H., and Tang, B. (2019). A comprehensive analysis of population differences in LRRK2 variant distribution in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 11, 13. [CrossRef]

- Oosterveld, L.P., Allen, J.C. Jr, Ng, E.Y.L., Seah, S.-H., Tay, K.-Y., Au, W.-L., Tan, E.-K., and Tan, L.C.S. (2015). Greater motor progression in patients with Parkinson disease who carry LRRK2 risk variants. Neurology 85, 1039–1042. [CrossRef]

- Marras, C., Alcalay, R.N., Caspell-Garcia, C., Coffey, C., Chan, P., Duda, J.E., Facheris, M.F., Fernández-Santiago, R., Ruíz-Martínez, J., and Mestre, T., et al. (2016). Motor and nonmotor heterogeneity of LRRK2-related and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 31, 1192–1202. [CrossRef]

- Saunders-Pullman, R., Mirelman, A., Alcalay, R.N., Wang, C., Ortega, R.A., Raymond, D., Mejia-Santana, H., Orbe-Reilly, M., Johannes, B.A., and Thaler, A., et al. (2018). Progression in the LRRK2-associated Parkinson disease population. JAMA Neurology 75, 312–319. [CrossRef]

- An, X.K., Peng, R., Li, T., Burgunder, J.M., Wu, Y., Chen, W.J., Zhang, J.H., Wang, Y.C., Xu, Y.M., and Gou, Y.R., et al. (2008). LRRK2 Gly2385Arg variant is a risk factor of Parkinson’s disease among Han Chinese from mainland China. European Journal of Neurology 15, 301–305. [CrossRef]

- Zimprich, A., Biskup, S., Leitner, P., Lichtner, P., Farrer, M., Lincoln, S., Kachergus, J., Hulihan, M., Uitti, R.J., and Calne, D.B., et al. (2004). Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron 44, 601–607. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.A., and Alcalay, R.N. (2017). Neuropathology of genetic synucleinopathies with parkinsonism: Review of the literature. Movement Disorders 32, 1504–1523. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.X., Sengupta, M., Trojanowski, J.Q., and Lee, V.M.Y. (2019). Alzheimer’s disease tau is a prominent pathology in LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 7, 183. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pajarín, G., Sesar, Á., Jiménez-Martín, I., Ares, B., and Castro, A. (2023). Progression and treatment of a series of patients with advanced LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease. Neurología (English Edition) 38, 350–356. [CrossRef]

- Ito, G., and Utsunomiya-Tate, N. (2023). Overview of the impact of pathogenic LRRK2 mutations in Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules 13, 845. [CrossRef]

- Iannotta, L., Biosa, A., Kluss, J.H., Tombesi, G., Kaganovich, A., Cogo, S., Plotegher, N., Civiero, L., Lobbestael, E., Baekelandt, V., et al. (2020). Divergent effects of G2019S and R1441C LRRK2 mutations on LRRK2 and Rab10 phosphorylations in mouse tissues. Cells 9, 2344. [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropulou, A.F., Purlyte, E., Tonelli, F., Lange, S.M., Wightman, M., Prescott, A.R., Padmanabhan, S., Sammler, E., and Alessi, D.R. (2022). Impact of 100 LRRK2 variants linked to Parkinson’s disease on kinase activity and microtubule binding. Biochem. J. 479, 1759–1783. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.M., Chan, L., Chan, D.K., and Kim, J.W. (2012). Genetics of Parkinson’s disease: a clinical perspective. J. Mov. Disord. 5, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Cheng, Y., Li, C., and Shang, H. (2022). Genetic heterogeneity on sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Neurodegener. 11, 21. [CrossRef]

- Di Fonzo, A., Rohé, C.F., Ferreira, J., Chien, H.F., Vacca, L., Stocchi, F., Guedes, L., Fabrizio, E., Manfredi, M., Vanacore, N., et al. (2005). A frequent LRRK2 gene mutation associated with autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 365, 412–415. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, B., Gopala, S., and Kishore, A. (2011). LRRK2 G2019S mutation does not contribute to Parkinson’s disease in South India. Neurol. India 59, 157–160. [CrossRef]

- Wszolek, Z.K., Pfeiffer, B., Fulgham, J.R., Parisi, J.E., Thompson, B.M., Uitti, R.J., Calne, D.B., and Pfeiffer, R.F. (1995). Western Nebraska family (family D) with autosomal dominant parkinsonism. Neurology 45, 502–505. [CrossRef]

- Wszolek, Z.K., Pfeiffer, R.F., Tsuboi, Y., Uitti, R.J., McComb, R.D., Stoessl, A.J., Strongosky, A.J., Zimprich, A., Müller-Myhsok, B., Farrer, M.J., et al. (2004). Autosomal dominant parkinsonism associated with variable synuclein and tau pathology. Neurology 62, 1619–1622. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., Wu, C.X., Burlak, C., Zhang, S., Sahm, H., Wang, M., Zhang, Z.Y., Vogel, K.W., Federici, M., Riddle, S.M., et al. (2014). Parkinson disease–associated mutation R1441H in LRRK2 prolongs the active state of its GTPase domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 4055–4060. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., Raj, A., Potdar, C., Pal, P.K., Yadav, R., Kamble, N., Holla, V., and Datta, I. (2023). Astrocytes differentiated from LRRK2-I1371V Parkinson’s disease–induced pluripotent stem cells exhibit cell-intrinsic dysfunction in glutamate uptake and metabolism, ATP generation, and Nrf2-mediated glutathione machinery. Cells 12, 1592. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, O., Seo, H., Andrabi, S., Guardia-Laguarta, C., Graziotto, J., Sundberg, M., McLean, J.R., Carrillo-Reid, L., Xie, Z., Osborn, T., et al. (2012). Pharmacological rescue of mitochondrial deficits in iPSC-derived neural cells from patients with familial Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 141ra90. [CrossRef]

- Vissers, M.F.J.M., Troyer, M.D., Thijssen, E., Pereira, D.R., Heuberger, J.A.A.C., Groeneveld, G.J., and Huntwork-Rodriguez, S. (2023). A leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) pathway biomarker characterization study in Parkinson’s disease with and without LRRK2 mutations and healthy controls. Clin. Transl. Sci. 16, 1408–1420. [CrossRef]

- Liou, A.K., Leak, R.K., Li, L., and Zigmond, M.J. (2008). Wild-type LRRK2 but not its mutant attenuates stress-induced cell death via ERK pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 32, 116–124. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M., Saito, K., Urata, M., Kumagai, Y., Maekawa, K., and Saito, Y. (2015). Comparison of circulating lipid profiles between fasting humans and three animal species used in preclinical studies: mice, rats and rabbits. Lipids Health Dis. 14, 104. [CrossRef]

- Langston, R.G., Beilina, A., Reed, X., Kaganovich, A., Singleton, A.B., Blauwendraat, C., Gibbs, J.R., and Cookson, M.R. (2022). Association of a common genetic variant with Parkinson’s disease is mediated by microglia. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabp8869. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S., Potdar, C., Yadav, R., Pal, P.K., and Datta, I. (2022). Dopaminergic neurons differentiated from LRRK2 I1371V-induced pluripotent stem cells display a lower yield, α-synuclein pathology, and functional impairment. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 13, 2632–2645. [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, T., Vishal, M., Das, G., Sharma, A., Mukhopadhyay, A., Das, S.K., Ray, K., and Ray, J. (2012). Evaluation of the role of LRRK2 gene in Parkinson’s disease in an East Indian cohort. Dis. Markers 32, 355–362. [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, K., Uronen, R.L., Blom, T., Li, S., Bittman, R., Lappalainen, P., Peränen, J., Raposo, G., and Ikonen, E. (2013). LDL cholesterol recycles to the plasma membrane via a Rab8a-Myosin5b-actin-dependent membrane transport route. Dev. Cell 27, 249–262. [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, S.G., Peränen, J., and Ikonen, E. (2016). LDL-cholesterol transport to the endoplasmic reticulum: current concepts. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 27, 282–287. [CrossRef]

- Galper, J., Kim, W.S., and Dzamko, N. (2022). LRRK2 and lipid pathways: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules 12, 1597. [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, T., Kuwahara, T., Sakurai, M., Komori, T., Fujimoto, T., Ito, G., Yoshimura, S.I., Harada, A., Fukuda, M., Koike, M., et al. (2018). LRRK2 and its substrate Rab GTPases are sequentially targeted onto stressed lysosomes and maintain their homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E9115–E9124. [CrossRef]

- Bonet-Ponce, L., Beilina, A., Williamson, C.D., Lindberg, E., Kluss, J.H., Saez-Atienzar, S., Landeck, N., Kumaran, R., Mamais, A., Bleck, C.K.E., et al. (2020). LRRK2 mediates tubulation and vesicle sorting from lysosomes. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb2454. [CrossRef]

- Kluss, J.H., Bonet-Ponce, L., Lewis, P.A., and Cookson, M.R. (2022). Directing LRRK2 to membranes of the endolysosomal pathway triggers RAB phosphorylation and JIP4 recruitment. Neurobiol. Dis. 170, 105769. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Espadas, J., Wu, Y., Cai, S., Ge, J., Shao, L., Roux, A., and De Camilli, P. (2023). Membrane remodeling properties of the Parkinson’s disease protein LRRK2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2309698120. [CrossRef]

- Reyes, S., Cottam, V., Kirik, D., Double, K.L., and Halliday, G.M. (2013). Variability in neuronal expression of dopamine receptors and transporters in the substantia nigra. Mov. Disord. 28, 1351–1359. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S., Sowmithra, —., Yadav, R., Pal, P.K., and Datta, I. (2022). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (NIMHi004-A, NIMHi005-A and NIMHi006-A) from healthy individuals of Indian ethnicity with no mutation for Parkinson’s disease related genes. Stem Cell Res. 60, 102716. [CrossRef]

- Potdar, C., Jagtap, S., Singh, K., Yadav, R., Pal, P.K., and Datta, I. (2024). Impaired Sonic Hedgehog responsiveness of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived floor plate cells carrying the LRRK2-I1371V mutation contributes to the ontogenic origin of lower dopaminergic neuron yield. Stem Cells Dev. 33, 306–320. [CrossRef]

- Moujalled, D., James, J.L., Parker, S.J., Lidgerwood, G.E., Duncan, C., Meyerowitz, J., Nonaka, T., Hasegawa, M., Kanninen, K.M., Grubman, A., et al. (2013). Kinase inhibitor screening identifies cyclin-dependent kinases and glycogen synthase kinase 3 as potential modulators of TDP-43 cytosolic accumulation during cell stress. PLoS One 8, e67433. [CrossRef]

- Keksel, N., Bussmann, H., Unger, M., Drewe, J., Boonen, G., Häberlein, H., and Franken, S. (2019). St John’s wort extract influences membrane fluidity and composition of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine in rat C6 glioblastoma cells. Phytomedicine 54, 66–76. [CrossRef]

- Folch, J., Lees, M., and Sloane Stanley, G.H. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Doktorova, M., Molugu, T.R., Heberle, F.A., Scott, H.L., Dzikovski, B., Nagao, M., Stingaciu, L.R., Standaert, R.F., Barrera, F.N., et al. (2020). How cholesterol stiffens unsaturated lipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 21896–21905. [CrossRef]

- Doole, F.T., Kumarage, T., Ashkar, R., and Brown, M.F. (2022). Cholesterol stiffening of lipid membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 255, 385–405. [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.M., and Tamm, L.K. (2004). Role of cholesterol in the formation and nature of lipid rafts in planar and spherical model membranes. Biophys. J. 86, 2965–2979. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C., Furlong, J., Burgos, P., and Johnston, L.J. (2002). The size of lipid rafts: an atomic force microscopy study of ganglioside GM1 domains in sphingomyelin/DOPC/cholesterol membranes. Biophys. J. 82, 2526–2535. [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F., Cremona, A., Arosio, P., Corsetto, P.A., Montorfano, G., Lascialfari, A., and Rizzo, A.M. (2012). Atomic force microscopy imaging of lipid rafts of human breast cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 2943–2949. [CrossRef]

- Sbarigia, C., Tacconi, S., Mura, F., Rossi, M., Dinarelli, S., and Dini, L. (2022). High-resolution atomic force microscopy as a tool for topographical mapping of surface budding. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 975919. [CrossRef]

- Iwagaki, H., Marutaka, M., Nezu, M., Suguri, T., Tanaka, N., and Orita, K. (1994). Cell membrane fluidity in K562 cells and its relation to receptor expression. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 85, 141–149.

- Kozubski, W., Swiderek, M., Kloszewska, I., Gwozdzinski, K., and Watala, C. (2002). Blood platelet membrane fluidity and the exposition of membrane protein receptors in Alzheimer disease patients—preliminary study. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 16, 52–54. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Stuehr DJ, Rousseau DL. A conserved Val to Ile switch near the heme pocket of animal and bacterial nitric-oxide synthases helps determine their distinct catalytic profiles. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279:19018–19025. [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, E., Lambry, J.C., Wang, Z.Q., Stuehr, D.J., Martin, J.L., and Slama-Schwok, A. (2007). Distal Val346Ile mutation in inducible NO synthase promotes substrate-dependent NO confinement. Biochemistry 46, 13533–13540. [CrossRef]

- Weisslocker-Schaetzel, M., Lembrouk, M., Santolini, J., and Dorlet, P. (2017). Revisiting the Val/Ile mutation in mammalian and bacterial nitric oxide synthases: A spectroscopic and kinetic study. Biochemistry 56, 748–756. [CrossRef]

- Wong, E., Bayly, C., Waterman, H.L., Riendeau, D., and Mancini, J.A. (1997). Conversion of prostaglandin G/H synthase-1 into an enzyme sensitive to PGHS-2-selective inhibitors by a double His513→Arg and Ile523→Val mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9280–9286. [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.K., Chang, C.M., Ravi, L., Ling, L., Castellano, C.M., Walter, E., Pelley, R.J., and Kung, H.J. (1994). Modulation of erbB kinase activity and oncogenic potential by single point mutations in the glycine loop of the catalytic domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 6868–6878. [CrossRef]

- Guy PM, Platko JV, Cantley LC, Cerione RA, Carraway KL. Insect cell-expressed p185c-erbB with a valine-to-isoleucine substitution shows relaxed ligand dependence and enhanced transforming potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994; 91:8132–8136. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda M, Iwata N, Kitajima T, et al. Association of a HCRTR1 isoleucine-to-valine mutation with polydipsic-hyponatremic schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010; 35:1275–1284. [CrossRef]

- Karhu, L., Magarkar, A., Bunker, A., and Xhaard, H. (2019). Determinants of orexin receptor binding and activation: A molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 2609–2622. [CrossRef]

- Zimniak, P., Nanduri, B., Pikuła, S., Bandorowicz-Pikuła, J., Singhal, S.S., Srivastava, S.K., Awasthi, S., and Awasthi, Y.C. (1994). Naturally occurring human glutathione S-transferase GSTP1-1 isoforms with isoleucine and valine in position 104 differ in enzymic properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 224, 893–899. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X., Yin, P., Hao, Q., Yan, C., Wang, J., and Yan, N. (2010). Single amino acid alteration between valine and isoleucine determines the distinct pyrabactin selectivity by PYL1 and PYL2. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28953–28958. [CrossRef]

- Miyazono K, Miyakawa T, Sawano Y, Kubota K, Miyauchi Y, Tanokura M. Structural basis of abscisic acid signalling. Nature. 2009; 462:609–614. [CrossRef]

- Simhadri, V.L., Hamasaki-Katagiri, N., Lin, B.C., Hunt, R., Jha, S., Tseng, S.C., Wu, A., Bentley, A.A., Zichel, R., and Lu, Q., et al. (2017). Single synonymous mutation in factor IX alters protein properties and underlies haemophilia B. J. Med. Genet. 54, 338–345. [CrossRef]

- Mouillet-Richard, S., Teil, C., Lenne, M., Hugon, S., Taleb, O., and Laplanche, J.L. (1999). Mutation at codon 210 (V210I) of the prion protein gene in a North African patient with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 168, 141–144. [CrossRef]

- Capellari, S., Parchi, P., Russo, C.M., Sanford, J., Sy, M.S., Gambetti, P., and Petersen, R.B. (2000). Effect of the E200K mutation on prion protein metabolism: Comparative study of a cell model and human brain. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 613–622. [CrossRef]

- Mastrianni, J.A., Capellari, S., Telling, G.C., Han, D., Bosque, P., Prusiner, S.B., and DeArmond, S.J. (2001). Inherited prion disease caused by the V210I mutation: transmission to transgenic mice. Neurology 57, 2198–2205. [CrossRef]

- Samal, S., Kumar, S., Khattar, S.K., and Samal, S.K. (2011). A single amino acid change, Q114R, in the cleavage-site sequence of Newcastle disease virus fusion protein attenuates viral replication and pathogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 2333–2338. [CrossRef]

- Keating, D.H., and Cronan, J.E. Jr. (1996). An isoleucine to valine substitution in Escherichia coli acyl carrier protein results in a functional protein of decreased molecular radius at elevated pH. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15905–15910. [CrossRef]

- Holak TA, Kearsley SK, Kim Y, Prestegard JH. An isoleucine-to-valine substitution in E. coli acyl carrier protein alters conformation and functional radius. Biochemistry. 1988; 27:6135–6142. [CrossRef]

- Kluss, J.H., Conti, M.M., Kaganovich, A., Beilina, A., Melrose, H.L., Cookson, M.R., and Mamais, A. (2018). Detection of endogenous S1292 LRRK2 autophosphorylation in mouse tissue as a readout for kinase activity. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 4, 13. [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A., Drouyer, M., Sarchione, A., Chartier-Harlin, M.C., and Taymans, J.M. (2020). LRRK2 phosphorylation, more than an epiphenomenon. Front. Neurosci. 14, 527. [CrossRef]

- Trilling, C.R., Weng, J.H., Sharma, P.K., Nolte, V., Wu, J., Ma, W., Boassa, D., Taylor, S.S., and Herberg, F.W. (2024). RedOx regulation of LRRK2 kinase activity by active site cysteines. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 75. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Arshad, M., Wang, W., Zhao, D., Xu, L., and Zhou, L. (2018). LRRK2-mediated Rab8a phosphorylation promotes lipid storage. Lipids Health Dis. 17, 34. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Sydor, A.M., Yan, B.R., Li, R., Boniecki, M.T., Lyons, C., Cygler, M., Muise, A.M., Maxson, M.E., Grinstein, S., et al. (2025). Salmonella exploits LRRK2-dependent plasma membrane dynamics to invade host cells. Nat. Commun. 16, 2329. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, S.R. (2018). LRRK2 and Rab GTPases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 46, 1707–1712. [CrossRef]

- Vona, R., Iessi, E., and Matarrese, P. (2021). Role of cholesterol and lipid rafts in cancer signaling: A promising therapeutic opportunity? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 622908. [CrossRef]

- Kabouridis, P.S., Janzen, J., Magee, A.L., and Ley, S.C. (2000). Cholesterol depletion disrupts lipid rafts and modulates the activity of multiple signaling pathways in T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 954–963. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.M., and Schmeidler, J. (2018). Outcome age-based prediction of successful cognitive aging by total cholesterol. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 952–960. [CrossRef]

- de Laurentiis, A., Donovan, L., and Arcaro, A. (2007). Lipid rafts and caveolae in signaling by growth factor receptors. Open Biochem. J. 1, 12–32. [CrossRef]

- Vereb, G., Matkó, J., Vámosi, G., Ibrahim, S.M., Magyar, E., Varga, S., Szöllosi, J., Jenei, A., Gáspár, R. Jr., Waldmann, T.A., et al. (2000). Cholesterol-dependent clustering of IL-2Rα and its colocalization with HLA and CD48 on T lymphoma cells suggest their functional association with lipid rafts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6013–6018. [CrossRef]

- Stetzkowski-Marden, F., Recouvreur, M., Camus, G., Cartaud, A., Marchand, S., and Cartaud, J. (2006). Rafts are required for acetylcholine receptor clustering. J. Mol. Neurosci. 30, 37–38. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D., Xiong, W.-C., and Mei, L. (2006). Lipid rafts serve as a signaling platform for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor clustering. J. Neurosci. 26, 4841–4851. [CrossRef]

- Slimane, T.A., Trugnan, G., Van IJzendoorn, S.C., and Hoekstra, D. (2003). Raft-mediated trafficking of apical resident proteins occurs in both direct and transcytotic pathways in polarized hepatic cells: role of distinct lipid microdomains. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 611–624. [CrossRef]

- Zou, W., Yadav, S., DeVault, L., Nung Jan, Y., and Sherwood, D.R. (2015). RAB-10-dependent membrane transport is required for dendrite arborization. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005484. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J., Yoo, H.S., Oh, J.S., Kim, J.S., Ye, B.S., Sohn, Y.H., and Lee, P.H. (2018). Effect of striatal dopamine depletion on cognition in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 51, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Morrow, C.B., Hinkle, J.T., Seemiller, J., Mills, K.A., and Pontone, G.M. (2024). The association of antidepressant use and impulse control disorder in Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 32, 710–720. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, R.A., and Foster, J.D. (2013). Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34, 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Fell, M.J., Mirescu, C., Basu, K., Cheewatrakoolpong, B., DeMong, D.E., Ellis, J.M., Hyde, L.A., Lin, Y., Markgraf, C.G., Mei, H., et al. (2015). MLi-2, a potent, selective, and centrally active compound for exploring the therapeutic potential and safety of LRRK2 kinase inhibition. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 355, 397–409. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Hamamichi, S., Lee, B.D., Yang, D., Ray, A., Caldwell, G.A., Caldwell, K.A., Dawson, T.M., Smith, W.W., and Dawson, V.L. (2011). Inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase attenuate neurodegeneration and Parkinson-like phenotypes in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila Parkinson’s disease models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3933–3942. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).