Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

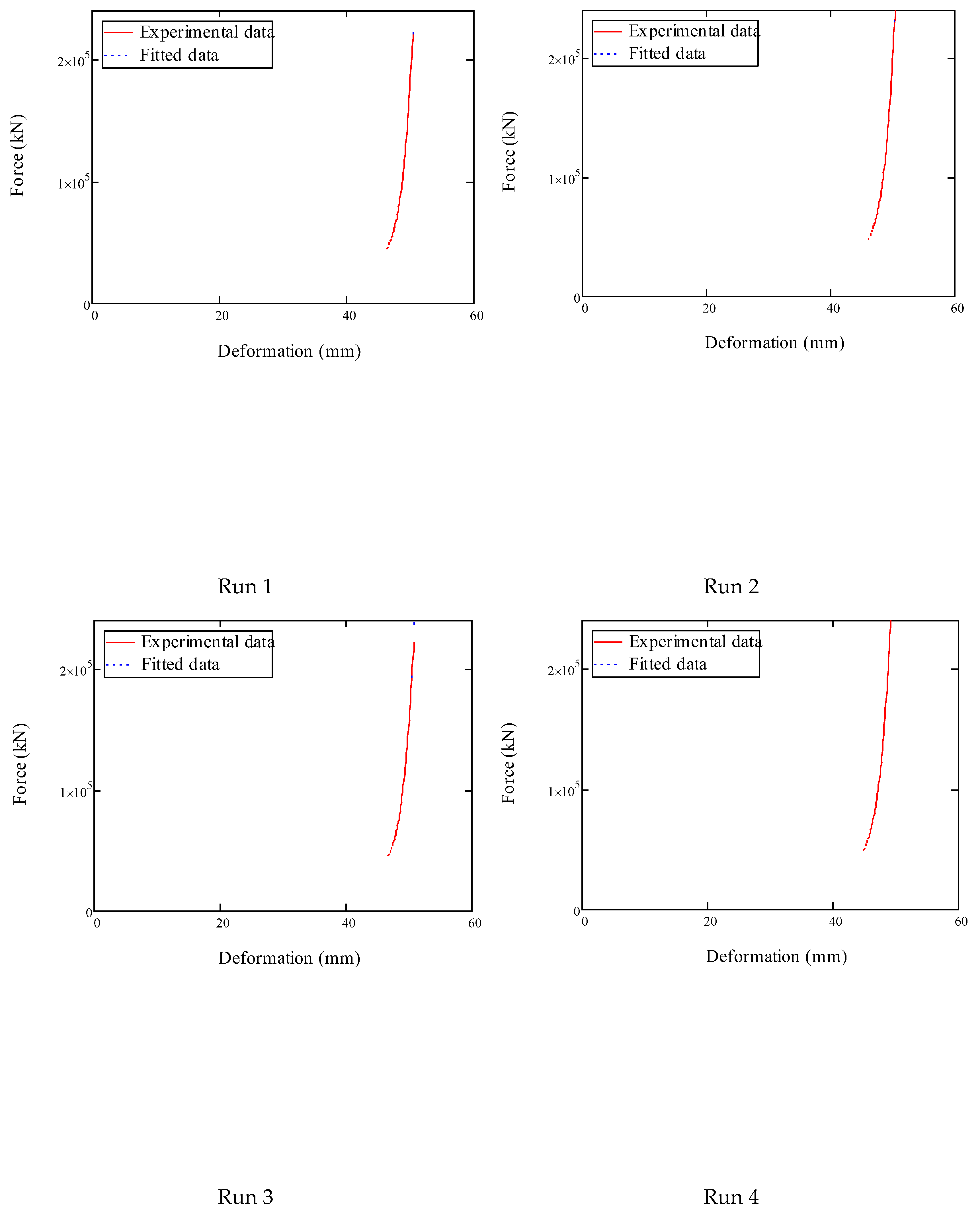

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Determination of Moisture Content

2.3. Determination of Oil Content

2.4. Box-Behnken Experimental Design

2.5. Pretreatment of Samples Using Standard Oven

2.6. Compression Tests of Samples After Pretreatment

2.6.1. Oil Yield

2.6.2. Oil Expression Efficiency

2.6.3. Deformation Energy

2.6.4. Force and Deformation

2.6.5. Hardness

2.6.6. Strain

2.6.7. Compressive Stress

2.6.8. Secant Modulus of Elasticity

2.7. Utilisation of Tangent Curve Model

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Calculated Moisture Content and Oil Content

3.2. Calculated Responses from the BBD Experimental Runs

| Run | Input processing factors | Calculated output parameters | ||||||

| (° C) | (min) | (mm) | (g) | (%) | (%) | (J) | ||

| 1 | 40 | 30 | 80 | 20.53 | 15.94 | 48.55 | 850.21 | |

| 2 | 60 | 30 | 80 | 26.46 | 20.55 | 62.57 | 934.74 | |

| 3 | 40 | 60 | 80 | 25.26 | 19.62 | 59.73 | 829.49 | |

| 4 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 27.72 | 21.53 | 65.55 | 972.28 | |

| 5 | 40 | 45 | 60 | 20.87 | 21.15 | 64.40 | 811.15 | |

| 6 | 60 | 45 | 60 | 21.8 | 22.09 | 67.27 | 818.03 | |

| 7 | 40 | 45 | 100 | 31.88 | 19.62 | 59.74 | 1143.53 | |

| 8 | 60 | 45 | 100 | 34.75 | 21.39 | 65.12 | 1179.6 | |

| 9 | 50 | 30 | 60 | 20.96 | 21.24 | 64.68 | 778.24 | |

| 10 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 21.37 | 21.66 | 65.94 | 722.55 | |

| 11 | 50 | 30 | 100 | 32.26 | 19.85 | 60.45 | 1051.14 | |

| 12 | 50 | 60 | 100 | 31.25 | 19.23 | 58.56 | 1092.21 | |

| 13* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 25.33 | 19.67 | 59.90 | 1009.82 | |

| 14* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 25.15 | 19.53 | 59.47 | 876.28 | |

| 15* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 26.89 | 20.88 | 63.59 | 909.25 | |

| 16* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 24.73 | 19.20 | 58.48 | 886.91 | |

| 17* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 28.92 | 22.46 | 68.39 | 886.46 | |

3.3. Calculated Mechanical Properties from the Force-Deformation Curves

3.4. ANOVA Analysis of Calculated Responses and Their Regression Coefficients

| Effect |

Model a coefficients |

Standard error |

t-value |

Sum of squares |

df | Mean square | F-value | p-value |

| Intercept | 26.20 | 0.77 | 33.89 | 292.5 | 9 | 32.50 | 10.87 | 0.00* |

| (L) | 1.52 | 0.61 | 2.49 | 18.57 | 1 | 18.57 | 6.25 | 0.04* |

| 2 (Q) | –0.17 | 0.84 | –0.21 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.84** |

| (L) | 0.67 | 0.61 | 1.10 | 3.63 | 1 | 3.63 | 1.22 | 0.31** |

| 2 (Q) | –1.04 | 0.84 | –1.23 | 4.54 | 1 | 4.54 | 1.53 | 0.26** |

| (L) | 5.64 | 0.61 | 9.23 | 254.70 | 1 | 254.70 | 85.65 | 0.00* |

| 2 (Q) | 1.29 | 0.84 | 1.54 | 7.05 | 1 | 7.05 | 2.37 | 0.17** |

| –0.87 | 0.86 | –1.00 | 3.01 | 1 | 3.01 | 1.01 | 0.35** | |

| 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.32 | 0.59** | |

| –0.36 | 0.86 | –0.41 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.69** | |

| Residual | 20.92 | 7 | 2.99 | |||||

| Lack of Fit | 9.03 | 3 | 3.01 | 1.01 | 0.47** | |||

| Pure Error | 11.89 | 4 | 2.97 | |||||

| Total | 313.42 | 16 |

| Effect |

Model a coefficients |

Standard error |

t-value |

Sum of squares |

df | Mean square | F-value | p-value |

| Intercept | 20.35 | 0.59 | 34.40 | 25.6 | 9 | 2.84 | 1.62 | 0.00* |

| (L) | 1.15 | 0.47 | 2.47 | 10.64 | 1 | 10.64 | 5.93 | 0.04* |

| 2 (Q) | –0.19 | 0.64 | –0.29 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.78** |

| (L) | 0.56 | 0.47 | 1.19 | 2.47 | 1 | 2.47 | 1.38 | 0.27** |

| 2 (Q) | –0.75 | 0.64 | –1.17 | 2.39 | 1 | 2.39 | 1.33 | 0.28** |

| (L) | –0.76 | 0.47 | –1.62 | 4.57 | 1 | 4.57 | 2.55 | 0.15** |

| 2 (Q) | 0.90 | 0.64 | 1.40 | 3.41 | 1 | 3.41 | 1.90 | 0.21** |

| –0.67 | 0.66 | –1.02 | 1.82 | 1 | 1.82 | 1.01 | 0.34** | |

| 0.21 | 0.66 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.76** | |

| –0.26 | 0.66 | –0.39 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.71** | |

| Residual | 12.24 | 7 | 1.75 | |||||

| Lack of Fit | 5.07 | 3 | 1.69 | 0.94 | 0.49** | |||

| Pure Error | 7.17 | 4 | 1.79 | |||||

| Total | 37.82 | 16 |

| Effect |

Model a coefficients |

Standard error |

t-value |

Sum of squares |

df | Mean square | F-value | p-value |

| Intercept | 61.96 | 1.80 | 34.40 | 237.2 | 9 | 26.35 | 1.62 | 0.00* |

| (L) | 3.51 | 1.42 | 2.47 | 98.62 | 1 | 98.62 | 5.93 | 0.04* |

| 2 (Q) | –0.57 | 1.96 | –0.29 | 1.37 | 1 | 1.37 | 0.08 | 0.78** |

| (L) | 1.69 | 1.42 | 1.19 | 22.91 | 1 | 22.91 | 1.38 | 0.27** |

| 2 (Q) | –2.29 | 1.96 | –1.17 | 22.17 | 1 | 22.17 | 1.33 | 0.28** |

| (L) | –2.30 | 1.42 | –1.62 | 42.37 | 1 | 42.37 | 2.55 | 0.15** |

| 2 (Q) | 2.74 | 1.96 | 1.40 | 31.59 | 1 | 31.59 | 1.90 | 0.21** |

| –2.05 | 2.01 | –1.02 | 16.83 | 1 | 16.83 | 1.01 | 0.34** | |

| 0.63 | 2.01 | 0.31 | 1.57 | 1 | 1.57 | 0.09 | 0.76** | |

| –0.79 | 2.01 | –0.39 | 2.49 | 1 | 2.49 | 0.15 | 0.71** | |

| Residual | 113.54 | 7 | 16.22 | |||||

| Lack of Fit | 47.02 | 3 | 15.67 | 0.94 | 0.49** | |||

| Pure Error | 66.51 | 4 | 16.63 | |||||

| Total | 350.69 | 16 |

| Effect |

Model a coefficients |

Standard error |

t-value |

Sum of squares |

df | Mean square | F-value | p-value |

| Intercept | 913.76 | 20.20 | 45.25 | 252777 | 9 | 28086.33 | 13.77 | 0.00* |

| (L) | 24.94 | 15.97 | 1.56 | 4977 | 1 | 4977 | 1.64 | 0.16** |

| 2 (Q) | 38.82 | 22.01 | 1.76 | 6345.4 | 1 | 6345.4 | 2.09 | 0.12** |

| (L) | –8.57 | 15.97 | –0.54 | 587 | 1 | 587 | 0.19 | 0.61** |

| 2 (Q) | –38.22 | 22.01 | –1.74 | 6151.2 | 1 | 6151.2 | 2.03 | 0.13** |

| (L) | 167.06 | 15.97 | 10.46 | 223282.4 | 1 | 223282.4 | 73.58 | 0.00* |

| 2 (Q) | 35.49 | 22.01 | 1.61 | 5304.2 | 1 | 5304.2 | 1.75 | 0.15** |

| 32.25 | 22.58 | 1.43 | 4159.6 | 1 | 4159.6 | 1.37 | 0.20** | |

| 7.30 | 22.58 | 0.32 | 213 | 1 | 213 | 0.07 | 0.76** | |

| 24.19 | 22.58 | 1.07 | 2340.6 | 1 | 2340.6 | 0.77 | 0.32** | |

| Residual | 14275.38 | 7 | 2039.34 | |||||

| Lack of Fit | 2137.3 | 3 | 712.4 | 0.23 | 0.87** | |||

| Pure Error | 12138 | 4 | 3034.5 | |||||

| Total | 267052.4 | 16 |

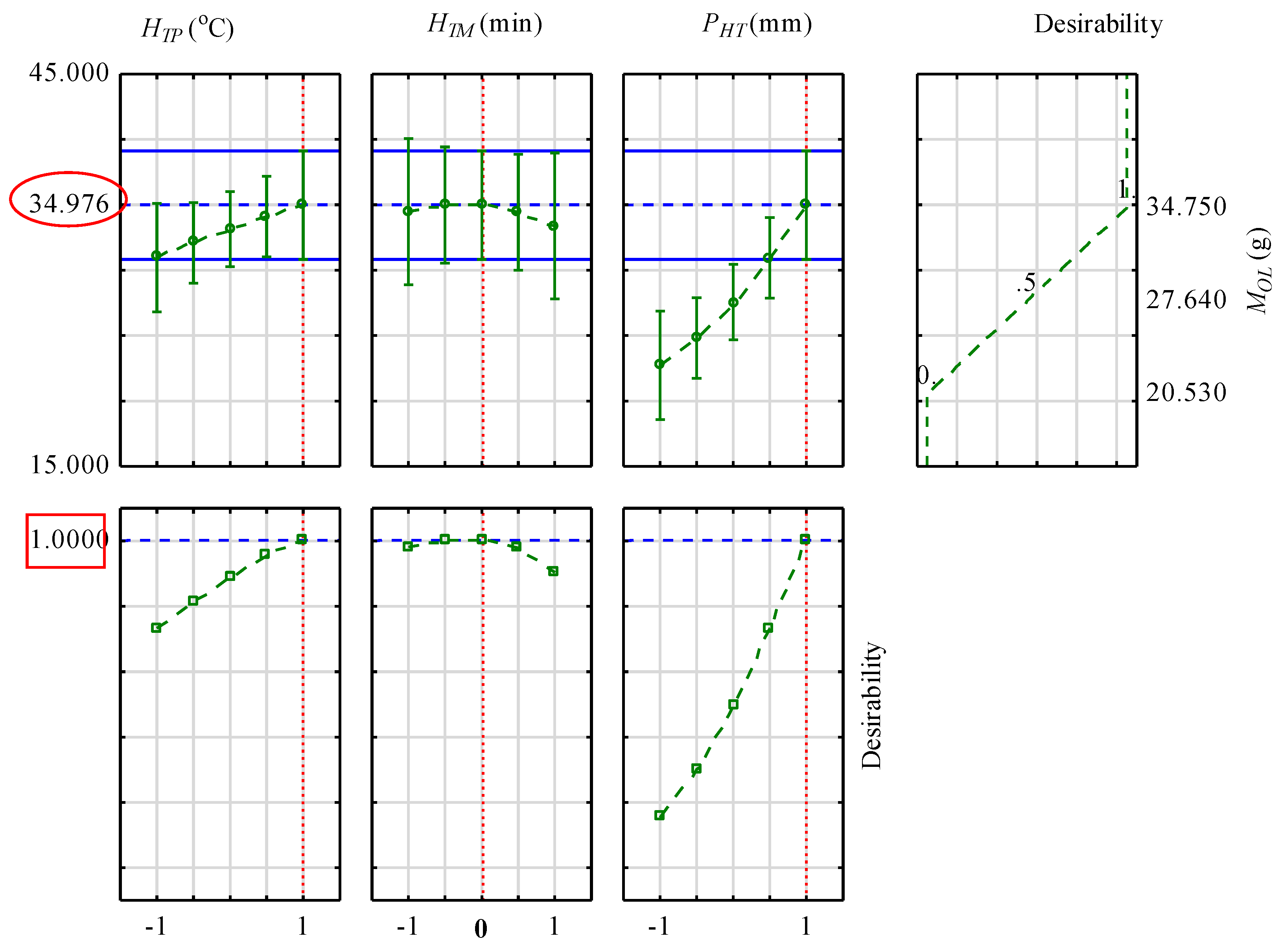

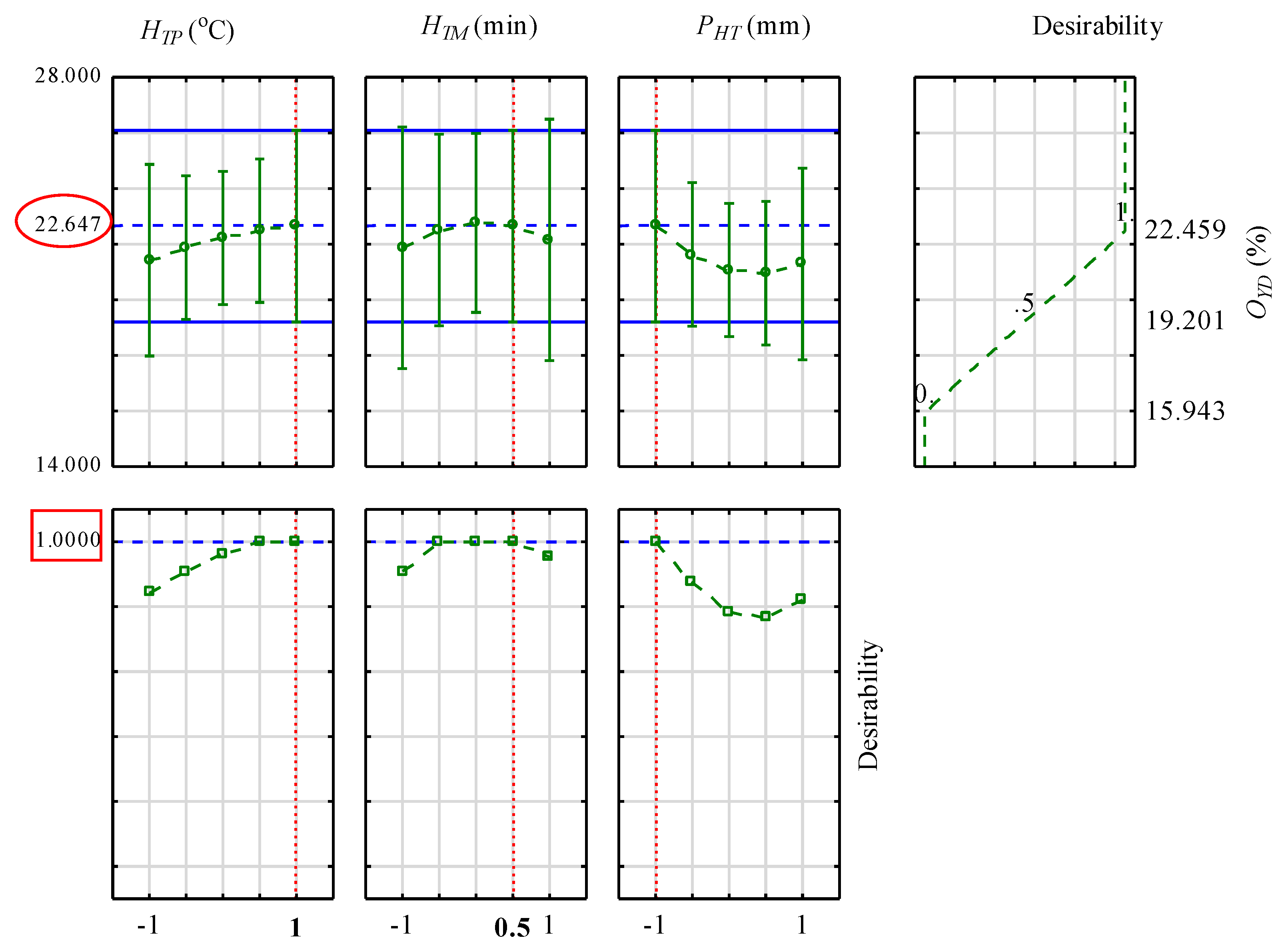

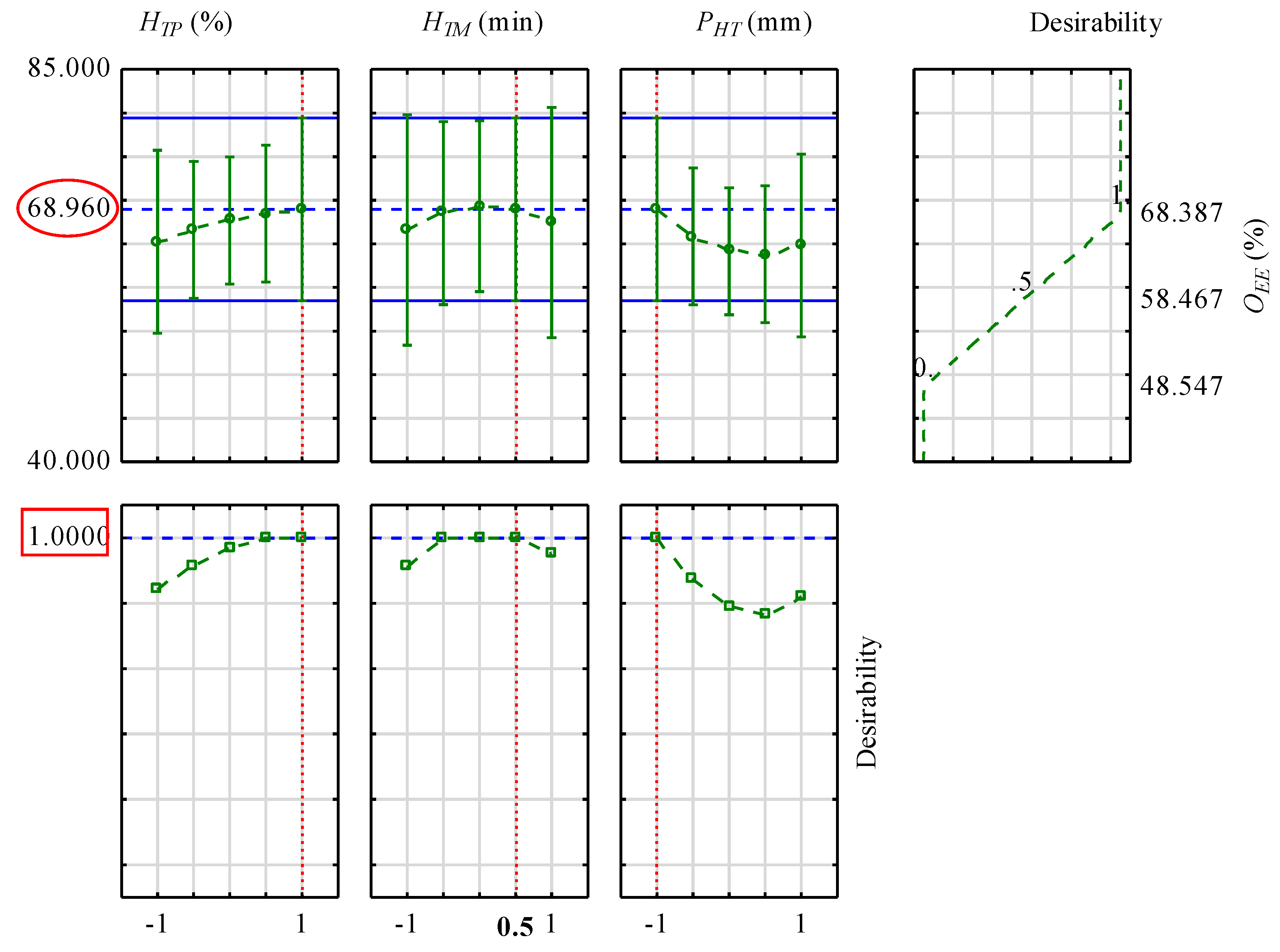

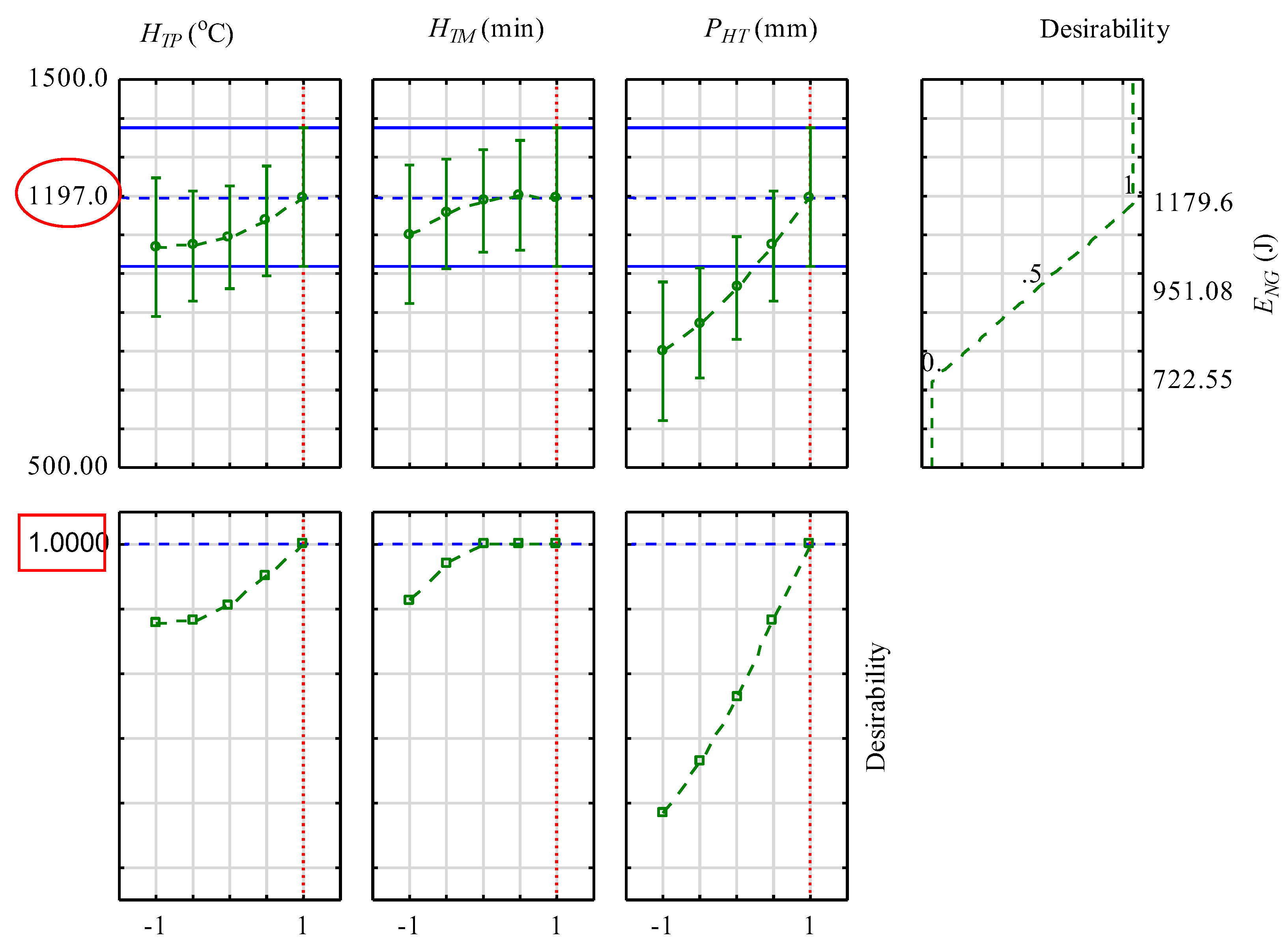

3.5. Profiles of Predicted Values Based on Optimal Input Factors and Desirability

| Model responses | Full quadratic model (Eqs.14, 16, 18 and 20) | Reduced model (Eqs.15, 17, 19 and 21) |

Absolute difference | Relative difference (%) |

| 34.98 | 33.36 | 1.62 | 4.62 | |

| 22.65 | 21.50 | 1.15 | 5.06 | |

| 68.96 | 65.47 | 3.49 | 5.06 | |

| 1197.00 | 1080.82 | 116.18 | 9.71 |

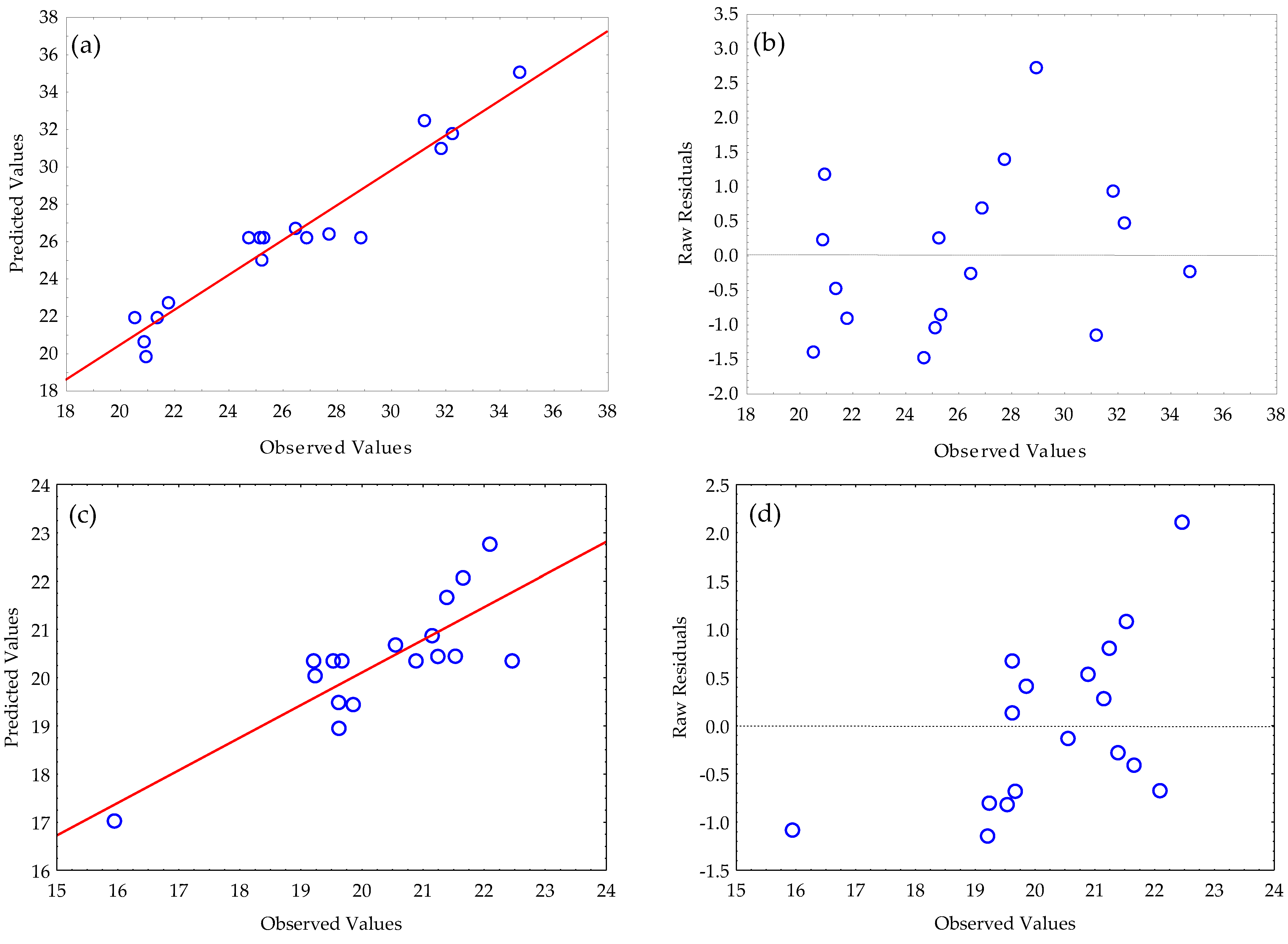

3.6. Observed, Predicted, Residuals and Percentage Error

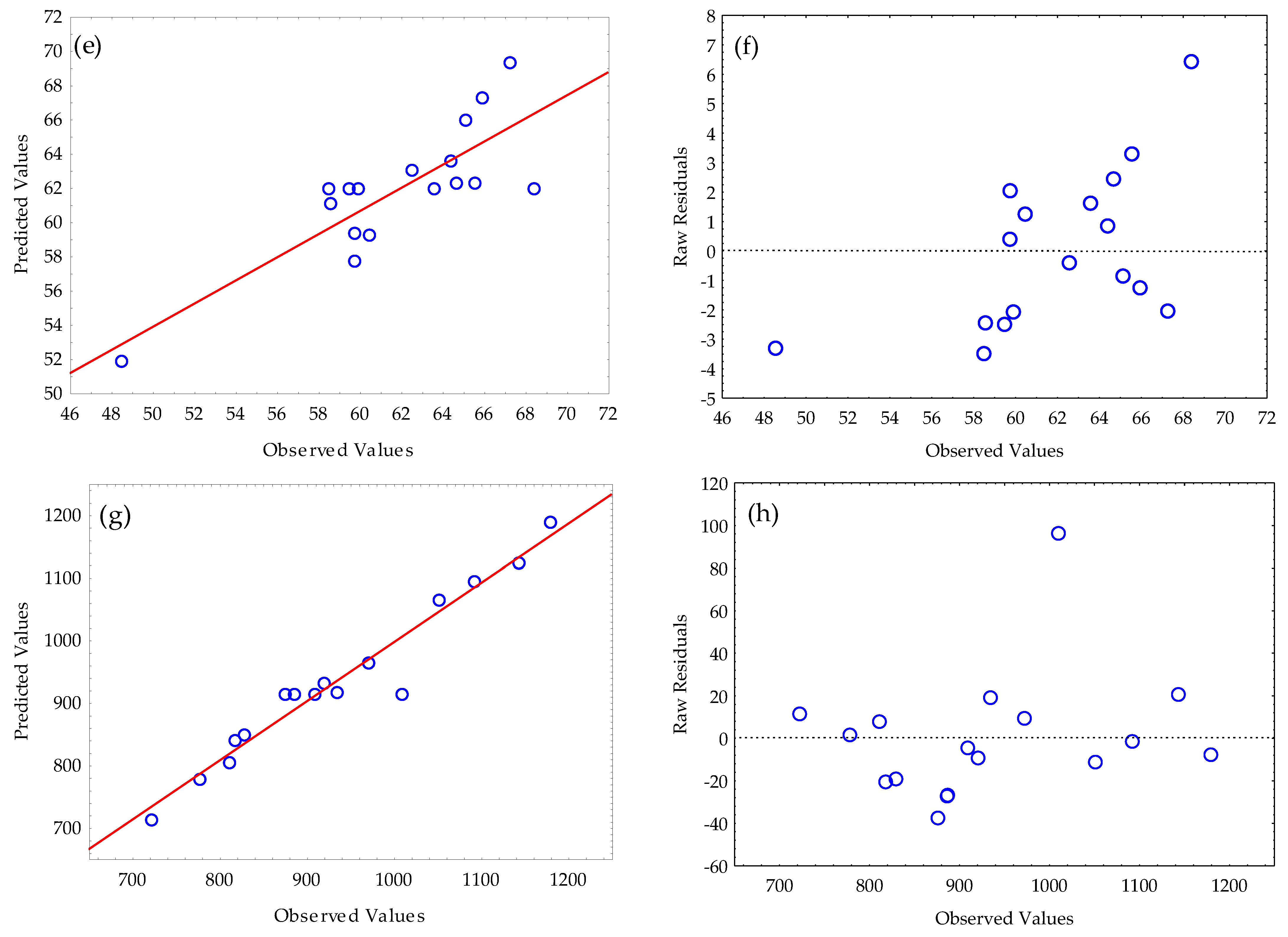

3.7. Theoretical Force-Deformation Curves and Deformation Energy

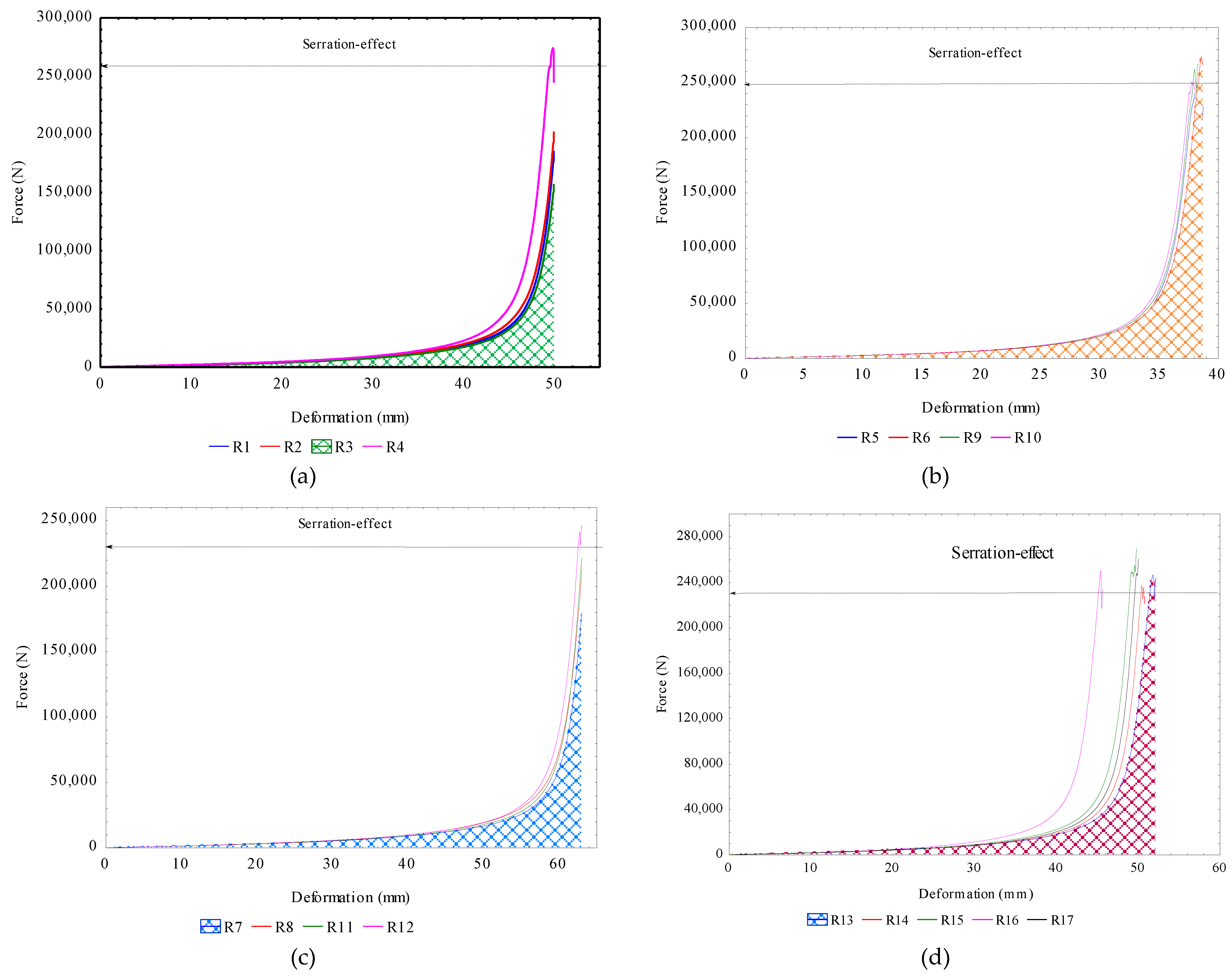

| Run | (mm) | (kN) | (mm –1) | n(-) | F-value | F-critical | P-value | R2 |

| 1 | 50.49 | 2.759 | 0.029 | 2 | 1.341 | 3.851 | 0.247 | 0.993 |

| 2 | 50.57 | 3.094 | 0.029 | 2 | 0.882 | 3.851 | 0.348 | 0.995 |

| 3 | 50.83 | 2.687 | 0.029 | 2 | 0.946 | 3.851 | 0.331 | 0.995 |

| 4 | 49.46 | 3.477 | 0.029 | 2 | 0.695 | 3.851 | 0.405 | 0.996 |

| 5 | 38.36 | 4.260 | 0.038 | 2 | 0.184 | 3.851 | 0.668 | 0.989 |

| 6 | 38.57 | 4.000 | 0.038 | 2 | 0.327 | 3.851 | 0.368 | 0.996 |

| 7 | 64.28 | 2.895 | 0.023 | 2 | 0.630 | 3.851 | 0.428 | 0.991 |

| 8 | 63.66 | 2.923 | 0.023 | 2 | 0.913 | 3.851 | 0.340 | 0.995 |

| 9 | 38.02 | 3.809 | 0.038 | 2 | 0.458 | 3.851 | 0.499 | 0.995 |

| 10 | 37.55 | 3.726 | 0.039 | 2 | 0.633 | 3.851 | 0.427 | 0.996 |

| 11 | 63.30 | 2.504 | 0.023 | 2 | 1.202 | 3.851 | 0.273 | 0.993 |

| 12 | 62.71 | 2.867 | 0.023 | 2 | 1.101 | 3.851 | 0.294 | 0.995 |

| 13 | 51.81 | 3.487 | 0.028 | 2 | 0.532 | 3.851 | 0.466 | 0.993 |

| 14 | 50.43 | 2.913 | 0.029 | 2 | 0.963 | 3.851 | 0.327 | 0.995 |

| 15 | 49.17 | 3.166 | 0.030 | 2 | 0.872 | 3.851 | 0.351 | 0.996 |

| 16 | 45.43 | 3.724 | 0.032 | 2 | 0.407 | 3.851 | 0.524 | 0.996 |

| 17 | 49.87 | 2.899 | 0.029 | 2 | 0.835 | 3.851 | 0.361 | 0.995 |

| Run | Input processing factors | Experimental and theoretical energy | ||||

| (° C) | (min) | (mm) | (J) | (J) | Error (%) | |

| 1 | 40 | 30 | 80 | 850.18 | 749.91 | 11.79 |

| 2 | 60 | 30 | 80 | 934.71 | 863.07 | 7.66 |

| 3 | 40 | 60 | 80 | 829.50 | 818.34 | 1.35 |

| 4 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 972.37 | 701.21 | 27.89 |

| 5 | 40 | 45 | 60 | 811.21 | 823.42 | 1.50 |

| 6 | 60 | 45 | 60 | 818.06 | 843.24 | 3.08 |

| 7 | 40 | 45 | 100 | 1141.28 | 1170 | 2.52 |

| 8 | 60 | 45 | 100 | 1179.66 | 1001 | 15.14 |

| 9 | 50 | 30 | 60 | 778.22 | 646.27 | 16.69 |

| 10 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 722.49 | 749.91 | 4.51 |

| 11 | 50 | 30 | 100 | 1051.16 | 784.87 | 25.33 |

| 12 | 50 | 60 | 100 | 1095.25 | 785.18 | 28.31 |

| 13 | 50 | 45 | 80 | 1009.84 | 851.14 | 15.72 |

| 14 | 50 | 45 | 80 | 876.21 | 776.742 | 11.35 |

| 15 | 50 | 45 | 80 | 909.29 | 943.75 | 3.79 |

| 16 | 50 | 45 | 80 | 886.90 | 820.62 | 7.47 |

| 17 | 50 | 45 | 80 | 886.16 | 653.78 | 26.22 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dudziec, P.; Warminski, K.; Stolarski, M.J. Industrial hemp as a multipurpose crop: Last achievements and research in 2018 –2023. Journal of Natural Fibres. 2024, 21(1), 1–46. [CrossRef]

- Kolodziej, J.; Pudelko, K.; Mankowski, J. Energy and biomass yield of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) as influenced by seeding rate and harvest time in Polish agro-climatic conditions. Journal of Natural Fibres. 2023, 20(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Hausman, J-F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis sativa: The plant of the thousand and one molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7(19), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hemp - Agriculture and rural development - European Commission, accessed on 05/12/2025.

- Pisanti, S.; Malfitano, A.M.; Ciaglia, E.; Lamberti, A.; Ranieri, R.; Cuomo, G.; Abate, M.; Faggina, G.; Proto, M.C.; Fiore, D.; Laezza, C.; Bifulco, M. Cannabidiol: State of the art and new challenges for therapeutic applications. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2017, 175, 133–150. [CrossRef]

- Michels, M.; Brinkmann, MuBhoff, O. Economic, ecological and social perspectives of industrial hemp cultivation in Germany: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Environmental Management. 2025, 389, 126117.

- Berardo, M.E.V.; Mendieta, J.R.; Villamonte, M.D.; Colman, S.L.; Nercessian, D. Antifungal and antibacterial activities of Cannabis sativa L. resins. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2024, 318, 116839. [CrossRef]

- Pieracci, Y.; Ascrizzi, R.; Terreni, V.; Pistelli, L.; Flamini, G.; Bassolino, L.; Fulvio, F.; Montanari, M.; Paris, R. Essential oil of Cannabis sativa L.: Composition of yield and chemical composition of 11 hemp genotypes. Molecules. 2021, 26, 4080. [CrossRef]

- Schultes, R.E.; Klein, W.M.; Plowman, T.; Lockwood, T.E. Cannabis: an example of taxonomic neglet. Cannabis Cult. 1975, 21–38.

- Cortes, J.G.; Ryu, B.R.; Pauli, C.; Barroso, L.R.; Park, S.H. Industrial applications of hemp fibre in Europe and evolving regulatory landscape. J. Nat. Fibers, 2024, 21(1), 2435047. [CrossRef]

- Industrial Hemp Market Size & Share | Industry Report, 2030, accessed 05/12/2025.

- The World's Top 5 Hemp-Producing Countries - CBD World News, accessed 05/12/2025.

- Oyarzun, M.; Saalbrink, J.; Bonilla, J.C.; Gouseti, O.; Jensen, P.E.; Risbo, J. Simultaneous extraction of hempseed oil bodies and protein concentrate through mild phytate-driven water-only fractionation. Future Foods, 2025. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.fufo.2025.100864.

- Yano, H.; Fu, W. Hemp: A sustainable plant with high industrial value in food processing. Foods, 2023, 12(3), 651. [CrossRef]

- Small, E. Cannabis: A Complete Guide. CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL (2017).

- Muangrat, R.; Kaikonjanat, A. Comparative evaluation of hemp seed oil yield and physicochemical properties using supercritical CO2, accelerated hexane, and screw press extraction techniques. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2025, 19, 101618. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Esteban, J.I.; González-Fernández, M.J.; Fabrikov, D.; de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M.; Torija-Isasa, E.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L. Fatty acids and minor functional compounds of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds and other Cannabaceae species. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 104962. [CrossRef]

- Farinon, B.; Molinari, R.; Costantini, L.; Merendino, N. The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Nutritional quality and potential functionality for human health and nutrition. Nutrients, 2020, 12(7), 1935. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Sefidkon, F.; Calagari, M.; Mousavi, A.; Mahomoodally, M.F. A comparative study of seed yield and oil composition of four cultivars of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) grown from three regions in northern Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112397. [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, Z.B.; Mitrovic, P.M.; Zlatkovic, V.; Grahovac, N.L.; Bankovic-Ilic, I.B.; Troter, D.Z.; Marjanovic-Jeromela, A.M.; Veljkovic, V.B. Optimization of oil recovery from oilseed rape by cold pressing using statistical modeling. J. Food Meas. Char. 2024, 18, 474–488. [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, R.K.; Mondal, I.H.; Dash, K.K.; Shaikh, A.M.; Béla, K. Effectiveness of sustainable oil extraction techniques: A comprehensive review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2025, 19, 101546. [CrossRef]

- Devi, M.P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Bhowmick, N.; Chakrabarty, S. Essential oil: its economic aspect, extraction, importance, uses, hazards and quality. Value Addition of Horticultural Crops: Recent Trends and Future Directions. 2015, 269–278.

- Kant, R.; Kumar, A. Review on essential oil extraction from aromatic and medicinal plants: techniques, performance and economic analysis. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 30, 100829. [CrossRef]

- Rakhee, Mishra, J.; Sharma, R.K.; Misra, K. Characterization techniques for herbal products. Management of High Altitude Pathophysiology. 2018, 171–202.

- Ali, M.K.; Jon, P.H.; Shourove, J.H.; Rahman, O.; Islam, G.M.R. Optimization of sonication-assisted hydrodistillation for essential oil extraction from Citrus macroptera peel: A comparative study of RSM and ANN. Applied Food Research. 2025, 5, 101446. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, J.J.; Jadeja, G.C.; Desai, M.A. Ultrasound-assisted hydrodistillation for extraction of essential oil from clove buds–A step towards process improvement and sustainable outcome. Chemical Engineering and Processing – Process Intensification. 2023, 189, 109404. [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari, N.; Yazdi, F.T.; Morazavi, S.A.; Mohammadi, M. Using pulsed electric field pre-treatment to optimize coriander seeds essential oil antimicrobial properties, antioxidant activity, and essential oil compositions. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2023, 182, 114852. [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Zahra, S.M.; Irfan, S.; Shafique, B.; Noreen, R.; Alahmad, U.F.; Liaqat, S.; Umar, S. Extraction and analysis of essential oils: extraction methods used at laboratory and industrial level and chemical analysis. Essential Oils: Extraction, Characterization and Applications. 2023, 37–52.

- Aytac, E. Comparison of extraction methods of virgin coconut oil: cold press, soxhlet and supercritical fluid extraction. Separation Science and Technology. 2022, 57(3), 426–432. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Abad, A.; Ramos, M.; Hamzaoui, M.; Kohnen, S.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigos, M.C. Optimization of sequential microwave-assisted extraction of essential oil and pigment from lemon peels waste. Foods. 2020, 9, 1493. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.; Ramli, N.; Abd-Aziz, S.; Ibrahim, M.F. Comparison of hydro-distillation, hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted and supercritical fluid for the extraction of essential oil from pineapple peels. 3 Biotech. 2019, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Apetroaei, V.T.; Pricop, E.M.; Istrati, D.I.; Vizireanu, C. Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa L.) as a valuable source of natural ingredients for functional foods – a review. Molecules. 2024, 29, 2097. [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, C.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Bartier, M.; Claux, M.; Tabasso, S. Green extraction of hemp seeds cake (Cannabis sativa L.) with 2-methyloxolane: a response surface optimization study. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 39, 101509. [CrossRef]

- Baldino, N.; Carnevale, I.; Mileti, O.; Aiello, D.; Lupi, F.R.; Napoli, A.; Gabriele, D. Hemp seed oil extraction and stable emulsion formulation with hemp protein isolates. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12(23), 11921. [CrossRef]

- Soroush, D.R.; Solaimanimehr, S.; Azizkhani, M.; Kenari, R.E.; Dehghan, B.; Mohammadi, G.; Sadeghi, E. Optimization of microwave-assisted solvent extractionof hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed oil using RSM: evaluation of oil quality. J. Food Meas. Char. 2021, 15, 5191–5202. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Jacobo, A.D.; Pacheco, A.D.; Bonales-Alatorre, E.; Castillo-Herrera, G.A.; Garcia-Fajardo, J.A. Cannabis extraction technologies: impact of research and value addition in Latin America. Molecules. 2023, 28(7), 2895. [CrossRef]

- Munson-Mcgee, S.H. D-optimal experimental designs for uniaxial expression. J. Food Process Eng. 2014, 37, 248–256. [CrossRef]

- Kabutey, A.; Kibret, S.H.; Kiros, A.W.; Afework, M.A.; Onwuka, M.; Raj, A. Comparative Analysis of Pretreatment Methods for Processing Bulk Flax and Hemp Oilseeds Under Uniaxial Compression. Foods 2025, 14, 629. [CrossRef]

- Demirel, C.; Kabutey, A.; Herák, D.; Sedlaček, A.; Mizera, Č.; Dajbych, O. Using Box–Behnken Design Coupled with Response Surface Methodology for Optimizing Rapeseed Oil Expression Parameters under Heating and Freezing Conditions. Processes 2022, 10, 490. [CrossRef]

- Kabutey, A.; Mizera, Č.; Dajbych, O.; Hrabě, P.; Herák, D.; Demirel, C. Modelling and Optimization of Processing Factors of Pumpkin Seeds Oil Extraction under Uniaxial Loading. Processes 2021, 9, 540. [CrossRef]

- Gürdil, G.A.K.; Kabutey, A.; Selvi, K.Ç.; Mizera, Č.; Herák, D.; Fraňková, A. Evaluation of Postharvest Processing of Hazelnut Kernel Oil Extraction Using Uniaxial Pressure and Organic Solvent. Processes 2020, 8, 957. [CrossRef]

- Divisova, M.; Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Sigalingging, R.; Svatonova, T. Deformation curve characteristics of rapeseeds and sunflower seeds under compression loading. Sci. Agric. Bohem. 2014, 45, 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Divisova, M.; Simanjuntak, S. Mathematical model of mechanical behaviour of Jatropha curcas L. Seeds under compression loading. Biosystems Engineering, 2013, 114(3), 279–288. [CrossRef]

- Saady, N.M.C.; Nazifa, T.H. Kiwi peel waste enhances manure protein degradation: Statistical optimization using Box-Behnken design and response surface methodology. Cleaner Waste Systems. 2025, 12, 100385. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, D.; Kumar, V.; Naik, B.; Gupta, A.K.; Richa, R. Process optimization and characterization of Shorea robusta (Sal) seed oil using response surface methodology: A sustainable approach to oil valorization. Food Chemistry: X. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Weremfo, A.; Abassah-Oppong, S.; Adulley, F.; Dabie, K.; Seidu-Larry, S. Response surface methodology as a tool to optimize the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant sources. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2023, 103, 26–36. [CrossRef]

- Avramovic, J.M.; Radosavljevic, D.B.; Velickovic, A.V.; Stojkovic, I.J.; Stamenkovic, O.S.; Veljkovic, V.B. Statistical modeling and optimization of ultrasound-assisted biodiesel production using various experimental designs. Zastita Materijala. 2019, 60(1), 70–80. [CrossRef]

- Polat, S.; Sayan, P. Application of response surface methodology with a Box-Behnken design for struvite precipitation. Advanced Powder Technology. 2019, 30, 2396–2407. [CrossRef]

- Veljkovic, V.B.; Velickovic, A.V.; Avramovic, J.M.; Stamenkovic, O.S. Modeling of biodiesel production: Performance comparison of Box-Behnken, face central composite and full factorial design. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering. 2019, 27, 1690–1698. [CrossRef]

- Stamenković, O. S.; Kostić, M. D.; Radosavljević, D. B.; Veljković, V. B. Comparison of box-behnken, face central composite and full factorial designs in optimization of hempseed oil extraction by n-hexane: a case study. Periodica Polytechnica Chemical Engineering. 2018, 62(3), 359–367. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mishra, S. Box-Behnken statistical design to optimize preparation of activated carbon from Limonia acidissima shell with desirability approach. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2017, 3, 588–600. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Q.; Ye, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, X. Box-Behnken design for extraction optimization, characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of Cicer arietinum L. hull polysaccharides. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2016, 147, 354–364. [CrossRef]

- Blahovec, J. Agromaterials Study Guide; Czech University of Life Sciences Prague: Prague, Czech Republic, 2008.

- IS:3579; Indian Standard Methods for Analysis of Oilseeds. Indian Standard Institute: New Delhi, India, 1996.

- Fornasari et al. Efficiency of the use of solvents in vegetable oil extraction at olaginous crops. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017, 80, 121–124.

- Niu, L.; Li, J.; Chen, M.-S.; Xu, Z.-F. Determination of oil contents in Sacha inchi (Plukenetia volubilis) seeds at different developmental stages by two methods: Soxhlet extraction and time-domain nuclear magnetic resonance. Ind Crop. Prod. 2014, 56, 187–190. [CrossRef]

- Danlami, J.M.; Arsad, A.; Zaini, M.A.A. Characterization and process optimization of castor oil (Ricinus communis L.) extracted by the Soxhlet method using polar and non-polar solvents. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem Eng. 2015, 47, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Chanioti, S.; Tzia, C. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of oil from olive pomace using response surface technology: Oil recovery, unsaponifiable matter, total phenol content and antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 178–189. [CrossRef]

- Ocholi, O.; Menkiti, M.; Auta, M.; Ezemagu, I. Optimization of the operating parameters for the extractive synthesis of biolubricant from sesame seed oil via response surface methodology. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 265–275. [CrossRef]

- Deli, S.; Farah Masturah, M.; Tajul Aris, Y.; Wan Nadiah, W.A. The effects of physical parameters of the screw press oil expeller on oil yield from Nigella sativa L. seeds. Int. Food Res. J. 2011, 18, 1367–1373.

- Hernandez-Santos, B.; Rodriguez-Miranda, J.; Herman-Lara, E.; Torruco-Uco, J.G.; Carmona-Garcia, R.; Juarez-Barrientos, J.M.; Chavez-Zamudio, R.; Martinez-Sanchez, C.E. Effect of oil extraction assisted by ultrasound on the physicochemical properties and fatty acid profile of pumpkin seed oil (Cucurbita pepo). Ultrason Sonochem. 2016, 31, 429–436. [CrossRef]

- Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Sedlacek, A.; Gurdil, G. Mechanical behaviour of several layers of selected plant seeds under compression loading. Res. Agr. Eng. 2012, 58(1), 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Lysiak, G. Fracture toughness of pea: Weibull analysis. Journal of Food Enginering, 2007, 83(3), 436–443. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Das, S.K. Fracture resistance of sunflower seed and kernel to compressive loading. Journal of Food Engineering, 2000, 46(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Choteborsky, R.; Petru, M.; Sigalingging, R. Mathematical models describing the relaxation behaviour of Jatropha curcas L. bulk seeds under axial compression. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 131, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Chakespari, A.G.; Rajabipour, A.; Mobli, H. Strength behaviour study of apples (cv. Shafi Abadi & Golab Kohanz) under compression loading. Modern Applied Science, 2010, 4(7), 173–182.

- StatSoft Inc. (1995). STATISTICA for Windows; StatSoft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2013.

- Pritchard, P.J. Mathcad: A Tool for Engineering Problem Solving; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998.

- Bambgoye, A.I.; Adejumo, O.I. Effects of processing parameters of Roselle seed on its oil yield. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2011, 4, 82–86.

- Moslavac, T.; Jokic, S.; Subaric, D.; Ostojcic, M.; Tomas, S.; Kovac, M.; Budzaki, S. Influence of drying, pressing, and antioxidants on yield and oxidative stability of cold pressing oils. Kem. Ind. 2023, 72, 433–442. [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, L.; Mathieu, T.; Mhemdi, H.; Vorobiev, E. Characterization of oilseeds mechanical expression in an instrumental pilot screw press. Ind. Crop Prod. 2018, 121, 106–113. [CrossRef]

- Baidhe, E.; Clementson, C.L. Modelling rupture and relaxation characteristics of soyabean under compressive loading. Biosystems Engineering, 2025, 254, 104137. [CrossRef]

- Sigalingging, R.; Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Dajbych, O.; Hrabe, P.; Mizera, C. Application of a tangent curve mathematical model for analysis of the mechancial behaviour of sunflower bulk seeds. International Agrophysics, 2015, 29, 517–524. [CrossRef]

- Musayev, M.; Kabutey, A.; Soe, S.S.; Kibret, S.H. Optimization of input factor levels for processing bulk hemp seeds under linear pressing. In: TAE 2025 – 9th International Conference on Trends in Agricultural Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 17-19, September 2025.

| Run | Input processing factors | Coded values using Eq. (2) | ||||

| (°C) | (min) | (mm) | (°C) | (min) | (mm) | |

| 1 | 40 | 30 | 80 | –1 | –1 | 0 |

| 2 | 60 | 30 | 80 | 1 | –1 | 0 |

| 3 | 40 | 60 | 80 | –1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 40 | 45 | 60 | –1 | 0 | -1 |

| 6 | 60 | 45 | 60 | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| 7 | 40 | 45 | 100 | –1 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 60 | 45 | 100 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | 50 | 30 | 60 | 0 | –1 | –1 |

| 10 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 0 | 1 | –1 |

| 11 | 50 | 30 | 100 | 0 | –1 | 1 |

| 12 | 50 | 60 | 100 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 13* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Run | Input processing factors | Calculated output parameters | ||||||||

| (° C) | (min) | (mm) | (kN) |

(mm) |

(kN/mm) |

(-) |

(MPa) |

(MPa) |

||

| 1 | 40 | 30 | 80 | 223.52 | 50.49 | 4.43 | 0.63 | 79.05 | 125.26 | |

| 2 | 60 | 30 | 80 | 250.17 | 50.57 | 4.95 | 0.63 | 88.48 | 139.97 | |

| 3 | 40 | 60 | 80 | 222.72 | 50.83 | 4.38 | 0.64 | 78.77 | 123.98 | |

| 4 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 257.77 | 49.46 | 5.21 | 0.62 | 91.17 | 147.46 | |

| 5 | 40 | 45 | 60 | 251.11 | 38.36 | 6.55 | 0.64 | 88.81 | 138.92 | |

| 6 | 60 | 45 | 60 | 273.34 | 38.57 | 7.09 | 0.64 | 96.68 | 150.39 | |

| 7 | 40 | 45 | 100 | 239.16 | 64.28 | 3.72 | 0.64 | 84.59 | 131.59 | |

| 8 | 60 | 45 | 100 | 266.93 | 63.66 | 4.19 | 0.64 | 94.41 | 148.30 | |

| 9 | 50 | 30 | 60 | 262.22 | 38.02 | 6.90 | 0.63 | 92.74 | 146.35 | |

| 10 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 241.16 | 37.55 | 6.42 | 0.63 | 85.29 | 136.29 | |

| 11 | 50 | 30 | 100 | 230.83 | 63.3 | 3.65 | 0.63 | 81.64 | 128.97 | |

| 12 | 50 | 60 | 100 | 241.23 | 62.71 | 3.85 | 0.63 | 85.32 | 136.05 | |

| 13* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 246.62 | 51.81 | 4.76 | 0.65 | 87.22 | 134.68 | |

| 14* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 237.37 | 50.43 | 4.71 | 0.63 | 83.95 | 133.18 | |

| 15* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 249.49 | 49.17 | 5.07 | 0.61 | 88.24 | 143.57 | |

| 16* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 250.18 | 45.43 | 5.51 | 0.57 | 88.48 | 155.81 | |

| 17* | 50 | 45 | 80 | 248.00 | 49.87 | 4.97 | 0.62 | 87.71 | 140.70 | |

| Runs | Mass of oil, | Oil yield, | ||||||

| Observed | Predicted | Residuals | % Error | Observed | Predicted | Residuals | % Error | |

| 1 | 20.53 | 21.93 | –1.40 | 6.37 | 15.94 | 17.03 | –1.08 | 6.36 |

| 2 | 26.46 | 26.71 | –0.25 | 0.94 | 20.55 | 20.68 | –0.13 | 0.64 |

| 3 | 25.26 | 25.01 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 19.62 | 19.48 | 0.13 | 0.67 |

| 4 | 27.72 | 26.32 | 1.40 | 5.31 | 21.53 | 20.44 | 1.08 | 5.30 |

| 5 | 20.87 | 20.64 | 0.23 | 1.10 | 21.15 | 20.87 | 0.28 | 1.34 |

| 6 | 21.80 | 22.72 | –0.92 | 4.05 | 22.09 | 22.76 | –0.67 | 2.96 |

| 7 | 31.88 | 30.96 | 0.92 | 2.98 | 19.62 | 18.95 | 0.67 | 3.55 |

| 8 | 34.75 | 34.98 | –0.23 | 0.65 | 21.39 | 21.66 | –0.28 | 1.29 |

| 9 | 20.96 | 19.79 | 1.17 | 5.92 | 21.24 | 20.44 | 0.80 | 3.94 |

| 10 | 21.37 | 21.85 | –0.48 | 2.18 | 21.66 | 22.07 | –0.41 | 1.86 |

| 11 | 32.26 | 31.78 | 0.48 | 1.50 | 19.85 | 19.44 | 0.41 | 2.11 |

| 12 | 31.25 | 32.42 | –1.17 | 3.61 | 19.23 | 20.04 | –0.80 | 4.01 |

| 13 | 25.33 | 26.20 | –0.87 | 3.34 | 19.67 | 20.35 | –0.68 | 3.34 |

| 14 | 25.15 | 26.20 | –1.05 | 4.02 | 19.53 | 20.35 | –0.82 | 4.02 |

| 15 | 26.89 | 26.20 | 0.69 | 2.62 | 20.88 | 20.35 | 0.53 | 2.62 |

| 16 | 24.73 | 26.20 | –1.47 | 5.63 | 19.20 | 20.35 | –1.14 | 5.63 |

| 17 | 28.92 | 26.20 | 2.72 | 10.36 | 22.46 | 20.35 | 2.11 | 10.36 |

| Runs | Oil expression efficiency, | Deformation energy, | ||||||

| Observed | Predicted | Residuals | % Error | Observed | Predicted | Residuals | % Error | |

| 1 | 48.55 | 51.85 | –3.30 | 6.36 | 920.94 | 930.23 | –9.29 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 62.57 | 62.97 | –0.40 | 0.64 | 934.74 | 915.62 | 19.12 | 2.09 |

| 3 | 59.73 | 59.33 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 829.49 | 848.61 | –19.12 | 2.25 |

| 4 | 65.55 | 62.25 | 3.30 | 5.30 | 972.28 | 962.99 | 9.29 | 0.97 |

| 5 | 64.40 | 63.55 | 0.85 | 1.34 | 811.15 | 803.37 | 7.78 | 0.97 |

| 6 | 67.27 | 69.32 | –2.05 | 2.96 | 818.03 | 838.66 | –20.63 | 2.46 |

| 7 | 59.74 | 57.69 | 2.05 | 3.55 | 1143.53 | 1122.90 | 20.63 | 1.84 |

| 8 | 65.12 | 65.97 | –0.85 | 1.29 | 1179.60 | 1187.38 | –7.78 | 0.66 |

| 9 | 64.68 | 62.23 | 2.45 | 3.94 | 778.24 | 776.73 | 1.51 | 0.19 |

| 10 | 65.94 | 67.19 | –1.25 | 1.86 | 722.55 | 711.22 | 11.33 | 1.59 |

| 11 | 60.45 | 59.21 | 1.25 | 2.11 | 1051.14 | 1062.48 | –11.34 | 1.07 |

| 12 | 58.56 | 61.01 | –2.45 | 4.01 | 1092.21 | 1093.72 | –1.51 | 0.14 |

| 13 | 59.90 | 61.96 | –2.07 | 3.34 | 1009.92 | 913.76 | 96.16 | 10.52 |

| 14 | 59.47 | 61.96 | –2.49 | 4.02 | 876.28 | 913.76 | –37.48 | 4.10 |

| 15 | 63.59 | 61.96 | 1.62 | 2.62 | 909.25 | 913.76 | –4.51 | 0.49 |

| 16 | 58.48 | 61.96 | –3.49 | 5.63 | 886.91 | 913.76 | –26.85 | 2.94 |

| 17 | 68.39 | 61.96 | 6.42 | 10.36 | 886.46 | 913.76 | –27.30 | 2.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).