1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), and in particular generative AI systems, has rapidly become embedded within higher education, influencing learning, assessment, research, and academic support practices. Universities worldwide are grappling with the opportunities and risks associated with AI tools, including concerns related to academic integrity, transparency, bias, and the development of critical thinking skills (Kasneci et al., 2023; Zhai et al., 2024). Recent evidence syntheses indicate that the pace of AI adoption in higher education has outstripped the development of coherent institutional guidance and pedagogical frameworks, creating uncertainty for both students and educators (Dos, 2025; Zhai et al., 2024). As a result, AI is increasingly recognised not only as a technological innovation but also as a pedagogical and ethical challenge requiring careful consideration.

Students represent the primary users of generative AI tools in higher education, employing them for activities such as writing support, translation, idea generation, and research assistance. Empirical studies consistently report widespread but uneven student adoption of AI tools, with patterns of use varying by discipline, experience, and perceived usefulness (Strzelecki, 2023; Tlili et al., 2023). Importantly, frequent use of AI does not necessarily correspond to high levels of understanding or confidence. Prior research suggests that students may develop practical familiarity with AI tools while lacking deeper conceptual understanding of how these systems function or how to evaluate their outputs critically (Zhai et al., 2024). Understanding students’ self-reported literacy, confidence, and perceived readiness is therefore essential for interpreting how AI is actually experienced in higher education settings.

Despite growing interest in AI in higher education, existing research remains fragmented. Many studies focus on attitudes toward AI, technology acceptance, or isolated use cases, while fewer provide integrated empirical assessments of students’ AI literacy, self-efficacy, and perceptions of institutional readiness within a single analytical framework (Dos, 2025). Moreover, institutional readiness is often examined from policy or leadership perspectives, with limited attention to how such readiness is perceived—or not perceived—by students themselves. Addressing this gap, the present study provides a cross-sectional quantitative examination of students’ awareness, self-reported AI literacy, and perceived readiness related to AI use in higher education. By focusing on student perceptions, the study contributes empirical evidence to ongoing discussions about responsible AI adoption and the alignment between student experience and institutional approaches.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Student Use and Adoption of AI Tools in Higher Education

Empirical research consistently indicates rapid growth in student use of generative AI tools in higher education, particularly following the public release of large language models such as ChatGPT. Systematic reviews of studies conducted between 2023 and 2025 show that students commonly use AI tools for writing support, idea generation, summarisation, translation, and research assistance (Dos, 2025; Zhai et al., 2024). However, these reviews also emphasise substantial variation in adoption rates across institutions, disciplines, and national contexts, suggesting that AI use is widespread but far from uniform. Earlier research on artificial intelligence in higher education, conducted prior to the emergence of generative AI tools, similarly highlighted uneven adoption and limited pedagogical integration, with a notable gap between technological development and educational practice (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019).

Journal-based studies further illustrate this heterogeneity. For example, surveys of university students in Europe and elsewhere report high levels of experimentation with AI tools alongside persistent non-use among a significant minority of students (Strzelecki, 2023; Tlili et al., 2023). Acceptance-based models, such as the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), indicate that perceived usefulness, ease of use, and institutional norms strongly influence whether students adopt AI tools regularly. Importantly, frequent use does not necessarily indicate confidence or competence; several studies note that students may rely on AI tools pragmatically while remaining uncertain about appropriate use or long-term implications (Dos, 2025).

2.2. AI Literacy, Confidence, and Conceptual Understanding

Beyond usage patterns, recent scholarship has increasingly focused on AI literacy as a multidimensional construct encompassing technical understanding, operational skills, critical evaluation, and ethical awareness. Reviews of AI literacy research in higher education highlight that students often demonstrate functional familiarity with AI tools while lacking deeper understanding of how AI systems generate outputs, their limitations, or their potential biases (Zhai et al., 2024). This distinction between surface-level use and deeper literacy has been emphasised as a critical challenge for higher education institutions.

Empirical studies measuring AI literacy among university students report moderate levels of self-reported confidence overall, with considerable variation across different dimensions of literacy (e.g., operational competence versus critical or ethical understanding). Recent scale-development studies similarly argue that AI literacy cannot be reduced to tool proficiency alone and should be understood as a combination of knowledge, skills, and judgement (Long & Magerko, 2020; Ng et al., 2023). These findings suggest that moderate self-rated AI literacy, when observed, may reflect partial competence rather than comprehensive understanding, reinforcing the need for empirical assessment of multiple literacy dimensions within student populations.

2.3. Institutional Readiness, Policy Development, and Visibility

While student use and literacy have received increasing attention, research on institutional readiness for AI in higher education has largely focused on policy development, governance, and leadership perspectives. Studies examining institutional AI policies highlight rapid proliferation of guidelines related to academic integrity, assessment, and acceptable use, often developed in response to emerging concerns rather than through long-term strategic planning (Dodds et al., 2024; Perkins et al., 2025). However, several journal articles note that such policies are frequently fragmented, evolving, and inconsistently communicated to stakeholders.

Importantly, higher education research indicates that the existence of institutional AI policies does not guarantee student awareness or understanding of them. Mixed-methods studies report that students often perceive institutional guidance as unclear or invisible, even when formal policies are in place (Dodds et al., 2024). This lack of visibility may contribute to uncertainty regarding institutional preparedness and appropriate AI use. As a result, perceived institutional readiness may differ substantially from formal policy intentions, underscoring the importance of examining readiness from the student perspective rather than relying solely on institutional or leadership accounts.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study employed a cross-sectional quantitative survey design to examine students’ awareness, self-reported literacy, and perceived readiness related to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in higher education. Data were collected at a single point in time using an anonymous online questionnaire and analysed descriptively to characterise patterns of AI-related knowledge, confidence, and perceptions among students.

3.2. Participants

A total of 85 students participated in the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. No personally identifiable information was collected. Eligibility criteria required participants to be 18 years of age or older and currently enrolled in higher education.

Due to the inclusion of a “Cannot decide / No experience yet” response option for selected items, the effective sample size varies across analyses and is reported explicitly where relevant.

3.3. Instrument

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire administered via Microsoft Forms. The instrument included:

Seven Likert-type items assessing students’ AI awareness, confidence, and perceived support (AI literacy/self-efficacy).

One item measuring self-reported AI tool usage frequency.

One item assessing perceived readiness of students versus university managers to use AI in higher education.

Although question numbering differed between the Word questionnaire and the Microsoft Forms implementation, all analyses were conducted based on question content and construct identity, not numeric labels.

3.4. Ethical Approval and Considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Regent College London Research Ethics Committee prior to data collection. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Regent College London Code of Research Ethics and the UK Framework for Research Integrity. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained electronically before respondents accessed the questionnaire. The study involved no deception, no intervention, and no collection of personally identifiable information.

3.5. GDPR Compliance and Data Protection

Data were collected using Microsoft Forms configured for European Union (EU) data hosting to ensure compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). No personal data, including names, email addresses, IP addresses, or device identifiers, were collected. Survey settings were configured to disable response tracking and the collection of identifying metadata. All data were stored securely and accessed only by the research team for analysis and publication purposes.

3.6. Data Handling

Likert-type items used a five-point response scale ranging from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree, with an additional option: “Cannot decide / No experience yet.”

Responses in this category were treated as missing values for scale reliability estimation, composite score calculation, and descriptive statistics. However, their frequency was reported separately as a diagnostic indicator of uncertainty or limited exposure. No data imputation procedures were applied.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were descriptive and exploratory. Procedures included:

Item-level descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means)

Construction of a composite AI literacy/self-efficacy scale

Internal consistency assessment using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω)

Dimensionality assessment using eigenvalues and parallel analysis (conducted for exploratory validation purposes only).

Reliability analyses were conducted using complete cases only.

Given the study’s descriptive, perception-focused aims and the absence of a priori hypotheses, analyses were intentionally limited to descriptive statistics and internal consistency estimates, consistent with recommended practice for exploratory investigations of emerging phenomena.

4. Results

4.1. Dataset Overview

A total of 85 students completed the survey and were included in the analysis. All respondents provided usable data for the core survey items, enabling descriptive reporting. The AI literacy/self-efficacy scale consisted of seven Likert-type items, each offering a five-point agreement scale alongside an additional response option, “Cannot decide / No experience yet.”

Across the seven AI literacy/self-efficacy items, the proportion of respondents selecting “Cannot decide / No experience yet” varied between 5.9% and 12.9%, indicating differing levels of familiarity or confidence across specific aspects of AI use. As a result, the number of valid responses contributing to item-level descriptive statistics ranged from 74 to 80 per item. For analyses requiring complete data across all seven items, 63 respondents provided valid Likert-scale responses to every item and were therefore included in scale reliability estimation.

For the composite AI literacy/self-efficacy score, respondents who provided at least one valid Likert-scale response were retained, yielding a sample of 80 respondents for composite descriptive analyses. This approach allowed for maximal use of available data while preserving transparency regarding response completeness and uncertainty.

4.2. Internal Consistency and Scale Structure

The seven-item AI literacy/self-efficacy scale demonstrated strong internal consistency. Reliability analysis conducted on respondents with complete data for all seven items (N = 63) yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .84 and a McDonald’s omega of .88, indicating a high degree of consistency among the items comprising the scale.

Corrected item–total correlations ranged from .52 to .68, suggesting that each item contributed meaningfully to the overall scale. Examination of “alpha if item deleted” values indicated that removal of any individual item would not improve overall reliability, supporting retention of all seven items in the composite measure.

Assessment of scale dimensionality further supported the use of a single composite score. Eigenvalue analysis showed that the first factor accounted for a substantially larger proportion of variance than subsequent factors, and parallel analysis indicated that only the first factor exceeded eigenvalues expected by chance. Together, these results suggest that the scale is predominantly unidimensional and appropriate for summarisation using a single composite AI literacy/self-efficacy score. Internal consistency statistics for the AI literacy/self-efficacy scale are summarised in

Table 1.

4.3. Composite AI Literacy / Self-Efficacy Score

Composite AI literacy/self-efficacy scores were calculated for respondents who provided at least one valid Likert-scale response across the seven items, resulting in a sample of 80 respondents included in the composite descriptive analysis. Scores were computed as the mean of available item responses, excluding any selections of “Cannot decide / No experience yet.”

The composite AI literacy/self-efficacy score had a mean of 3.55 on a five-point scale, with a standard deviation of 0.77, indicating moderate overall self-reported literacy alongside substantial variability across respondents. The median score was 3.67, suggesting that half of respondents reported scores above this level. Observed scores spanned the full possible range of the scale, from 1.00 to 5.00, reflecting the presence of both low and high self-reported AI literacy within the sample.

The distribution of composite scores showed that most respondents clustered around the mid-to-upper range of the scale, while a smaller proportion reported lower levels of AI literacy/self-efficacy. This spread highlights heterogeneity in students’ self-reported confidence and perceived competence in relation to AI use.

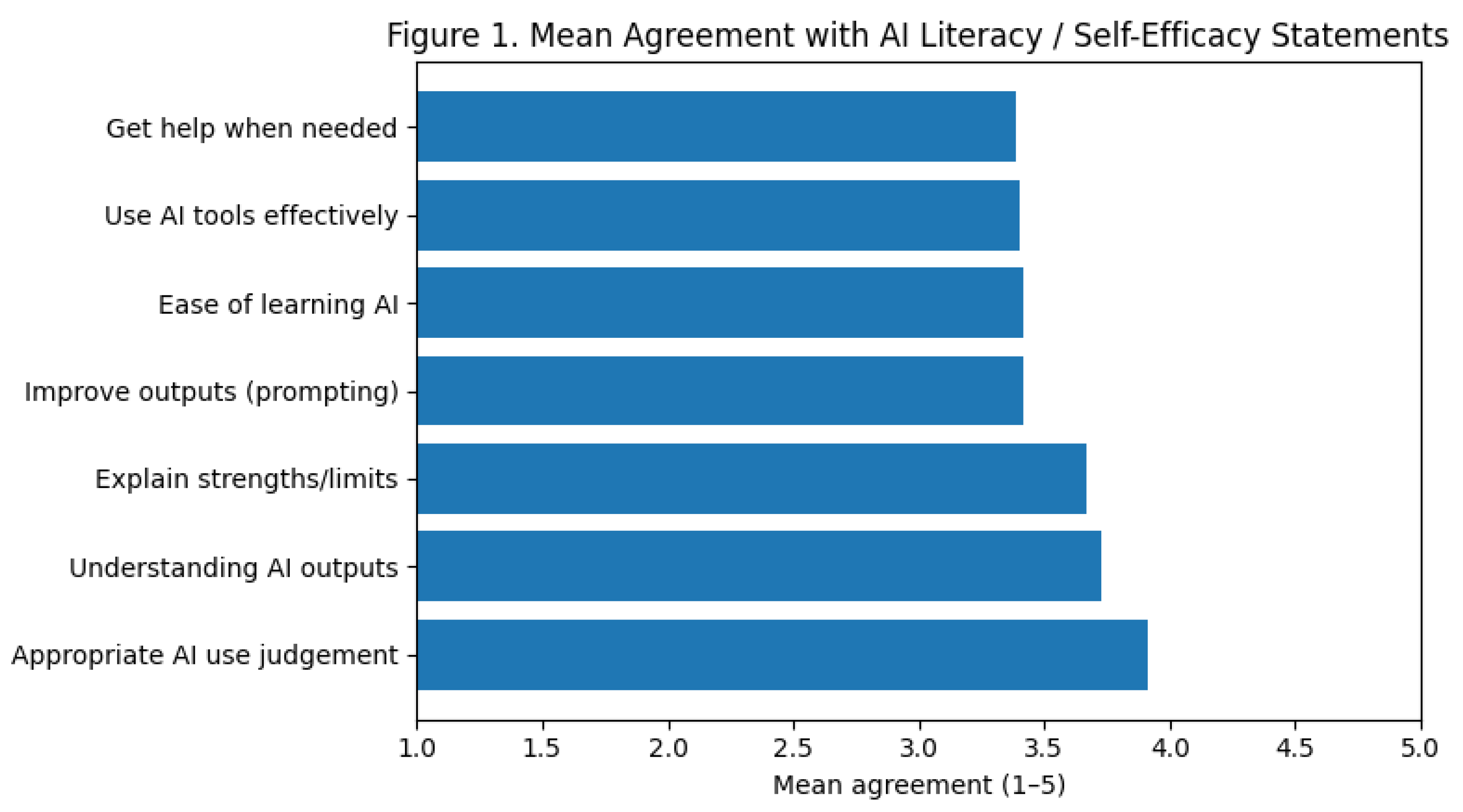

Figure 1.

Mean agreement with AI literacy and self-efficacy statements (item means, excluding ‘Cannot decide / No experience yet’).

Figure 1.

Mean agreement with AI literacy and self-efficacy statements (item means, excluding ‘Cannot decide / No experience yet’).

4.4. Item-Level Findings

Item-level descriptive statistics for the AI literacy/self-efficacy items are presented in

Table 2. Across the seven items, mean scores ranged from 3.39 to 3.91 on the five-point agreement scale, indicating variation in students’ self-reported confidence across different aspects of AI use.

The highest mean score was observed for the item assessing students’ ability to judge appropriate versus inappropriate use of AI (M = 3.91, valid N = 80). More than three-quarters of respondents selected agree or strongly agree for this item, while a small proportion selected disagree or strongly disagree. A further 5.9% of respondents selected “Cannot decide / No experience yet”, indicating limited uncertainty for this aspect of AI use.

Relatively high mean scores were also observed for students’ general understanding of how AI systems produce results (M = 3.73, valid N = 80) and for their ability to explain the strengths and limitations of AI tools to others (M = 3.67, valid N = 75). For these items, the majority of respondents reported agreement, although higher proportions of “Cannot decide / No experience yet” responses were observed for the latter (11.8%), suggesting greater variability in confidence related to explaining AI concepts.

Lower mean scores were reported for items assessing more practical or support-related aspects of AI use. Students’ ability to improve AI outputs through prompting had a mean score of 3.42 (valid N = 76), with just over half of respondents selecting agree or strongly agree and 10.6% indicating “Cannot decide / No experience yet.” A similar pattern was observed for perceived ease of learning AI tools (M = 3.42, valid N = 77), with nearly one in ten respondents reporting uncertainty.

The lowest mean score was observed for the item assessing students’ ability to obtain help when needed while using AI tools (M = 3.39, valid N = 74). This item also exhibited the highest proportion of “Cannot decide / No experience yet” responses (12.9%), indicating substantial uncertainty regarding access to support.

In sum, the item-level results demonstrate higher self-reported confidence in judgement and conceptual understanding compared with practical skills and access to support, alongside varying levels of uncertainty across specific aspects of AI use.

4.5. AI Tool Usage Frequency

Self-reported frequency of AI tool use among respondents is summarised in

Table 3. Across the sample, AI tool use was widespread but varied considerably across the sample. More than half of respondents (55.3%, n = 47) reported using AI tools daily or weekly, indicating regular engagement with AI in their academic activities.

A further 11.8% of respondents (n = 10) reported using AI tools on a monthly basis, suggesting occasional but recurring use. In contrast, 21.2% of respondents (n = 18) indicated that they used AI tools rarely, while 11.8% (n = 10) reported never using AI tools. Collectively, nearly one quarter of the sample (23.6%) reported rare or no use of AI tools.

These findings demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in students’ engagement with AI tools, with usage patterns ranging from frequent to non-existent within the same student population.

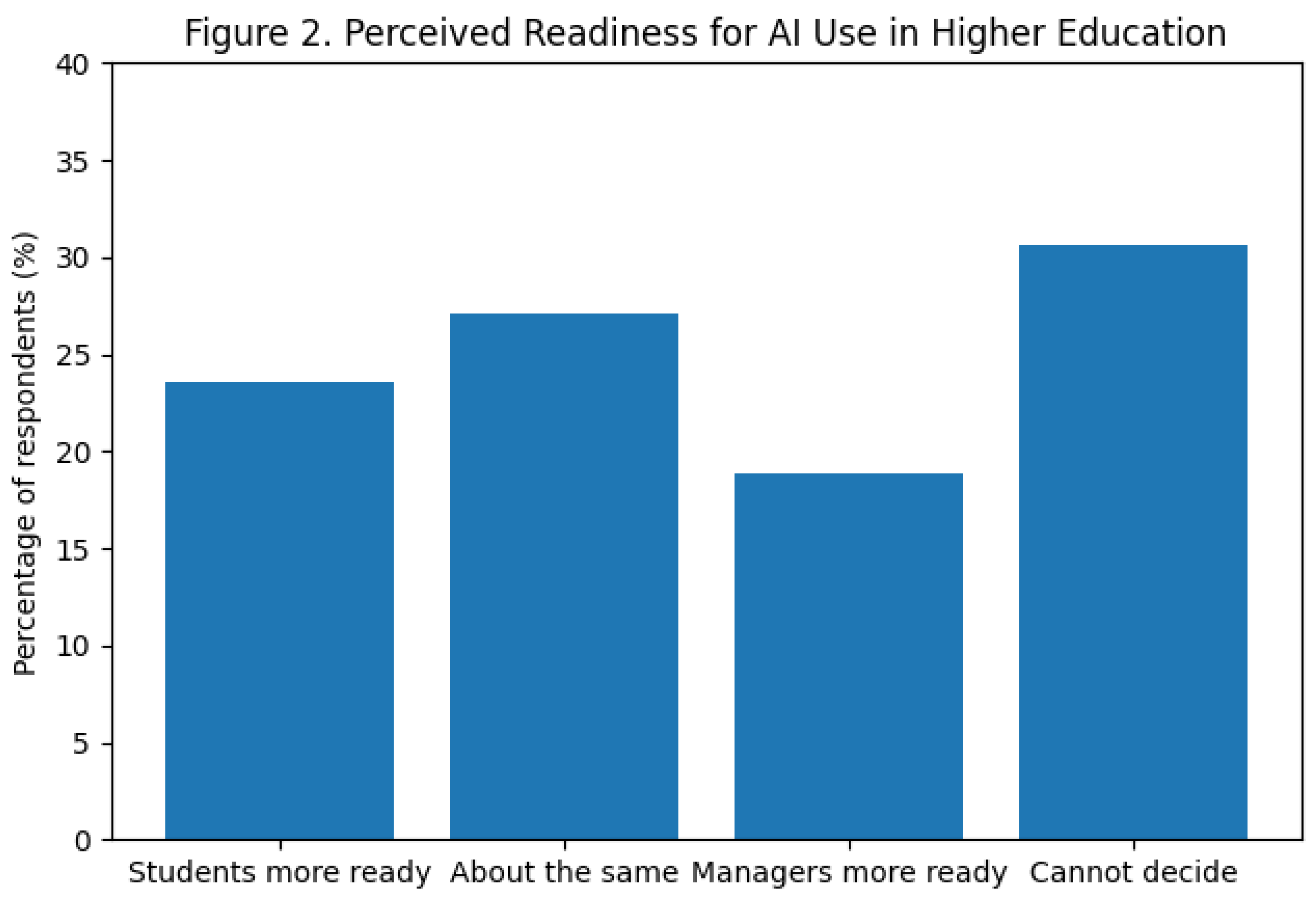

4.6. Perceived Readiness Comparison

Students were asked to compare the readiness of students and university managers to use artificial intelligence in higher education. Responses to this item are summarised in

Table 4. At the descriptive level, responses were distributed across all available categories, indicating diverse perceptions of relative readiness.

The most frequently selected response was “Cannot decide / No experience yet,” chosen by 30.6% of respondents (n = 26). This indicates that nearly one third of students reported insufficient information or experience to judge the relative readiness of students and university managers.

Among respondents who expressed a directional judgement, 27.1% (n = 23) indicated that students and university managers were about the same in terms of readiness to use AI. A further 23.6% of respondents (n = 20) perceived students as more ready to use AI, with 11.8% (n = 10) indicating that students were much more ready and 11.8% (n = 10) indicating that students were somewhat more ready.

In contrast, 18.9% of respondents (n = 16) perceived university managers as more ready to use AI. Of these, 16.5% (n = 14) selected managers much more ready, while 2.4% (n = 2) selected managers somewhat more ready. These distributions indicate that perceptions of greater readiness were more frequently attributed to students than to university managers, although a substantial proportion of respondents reported uncertainty.

Figure 2.

Distribution of student perceptions regarding readiness to use AI in higher education (students vs university managers).

Figure 2.

Distribution of student perceptions regarding readiness to use AI in higher education (students vs university managers).

4.7. Interpretive Boundaries

All results reported in this section reflect self-reported student perceptions and experiences. Findings should be interpreted as descriptive indicators of students’ awareness, confidence, and perceived readiness related to AI use, rather than as objective assessments of institutional practices, policies, or effectiveness.

The single-item measure of perceived institutional readiness and the explicit reporting of ‘Cannot decide / No experience yet’ responses reflect the study’s focus on students’ subjective evaluations rather than objective institutional capacity, with uncertainty treated as an analytically meaningful outcome rather than as missing data.

5. Discussion

5.1. Overview of Key Findings

This study provides a descriptive overview of students’ awareness, self-reported literacy, and perceived readiness related to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in higher education. Viewed together, the findings indicate that student engagement with AI is characterised by moderate confidence, uneven patterns of use, and substantial uncertainty regarding institutional readiness.

Across the sample, students reported generally positive but not uniformly high levels of AI literacy and self-efficacy. Confidence was strongest in relation to judgement-oriented aspects of AI use, such as distinguishing appropriate from inappropriate applications, while comparatively lower confidence and greater uncertainty were observed for practical and support-related dimensions, including access to help and the ability to refine AI outputs. This pattern suggests that students may be more comfortable forming evaluative judgements about AI use than navigating technical or institutional support structures.

Patterns of AI tool use further highlighted heterogeneity within the student population. While a majority of respondents reported regular engagement with AI tools, a substantial minority reported infrequent or no use. This coexistence of frequent users and non-users within the same educational context underscores that AI adoption among students is neither universal nor uniform, even amid widespread availability of generative AI tools.

Notably, perceptions of institutional readiness were marked by high levels of uncertainty. A sizeable proportion of students reported being unable to judge whether universities or their managers were prepared to use AI in higher education. This uncertainty emerged as a salient feature of the results and distinguishes perceived institutional readiness from individual-level confidence or usage patterns.

Taken together, these findings portray a student population that is actively engaging with AI but doing so within a landscape of partial confidence, uneven experience, and limited clarity regarding institutional preparedness. This combination of engagement and uncertainty provides an important foundation for interpreting the results in relation to existing literature and for examining how student perceptions align with broader discussions of AI adoption in higher education (Dos, 2025; Zhai et al., 2024).

5.2. Student AI Literacy and Confidence in Context

The moderate level of AI literacy and self-efficacy reported by students in this study aligns with patterns observed in recent research on student engagement with generative AI in higher education. Systematic reviews and empirical studies consistently report that students tend to express moderate to positive confidence in their ability to use AI tools, while also demonstrating variability across different dimensions of literacy (Dos, 2025; Zhai et al., 2024; Kasneci et al., 2023). The present findings therefore contribute to a growing body of evidence suggesting that student AI literacy is neither uniformly high nor uniformly low, but instead reflects partial and uneven competence.

Importantly, the item-level results in this study highlight a distinction between judgement-oriented confidence and practical or support-related confidence. Students reported higher confidence in evaluating appropriate versus inappropriate AI use and in understanding how AI systems generate outputs, compared with their confidence in accessing help or improving AI outputs through prompting. This pattern mirrors prior research indicating that students may internalise ethical norms and evaluative frameworks more readily than they acquire technical skills or navigate institutional support mechanisms (Zhai et al., 2024; Ng et al., 2023).

The prominence of uncertainty in relation to support and skill development further reflects concerns raised in the literature regarding the limited availability of structured AI literacy training in higher education. While students often develop familiarity with AI tools through informal experimentation, studies suggest that such exposure does not necessarily translate into deeper understanding or confidence in more advanced use (Dos, 2025). The present findings reinforce this distinction by demonstrating that confidence is highest for conceptual judgement and lowest for aspects of AI use that depend on guidance, feedback, or institutional resources.

Collectively, these results support the view that AI literacy among students should be understood as a multidimensional construct, rather than a single continuum of competence (Ng et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023). The moderate composite score observed in this study likely reflects the coexistence of strengths in evaluative judgement alongside limitations in practical skills and support awareness. This interpretation is consistent with recent calls in the literature to move beyond binary characterisations of students as either “AI literate” or “AI illiterate,” and instead to examine specific dimensions of literacy in relation to educational context and institutional support structures (Ng et al., 2023).

5.3. Patterns of AI Tool Use

The heterogeneous patterns of AI tool use observed in this study are consistent with existing empirical research on student engagement with generative AI in higher education. While a majority of respondents reported regular use of AI tools, a substantial minority reported infrequent or no use, indicating that adoption is uneven even within a single student population. This coexistence of frequent users and non-users has been widely documented in journal-based studies and systematic reviews, which report considerable variability in student uptake across institutions, disciplines, and individual learning contexts (Strzelecki, 2023; Tlili et al., 2023; Dos, 2025).

Previous research suggests that frequent use of AI tools is often driven by perceived usefulness for specific academic tasks, such as writing support, idea generation, or summarisation, rather than by comprehensive understanding or institutional endorsement (Zhai et al., 2024). At the same time, non-use or limited use among a subset of students has been attributed to factors such as lack of confidence, ethical concerns, uncertainty about acceptable use, or limited perceived relevance to particular fields of study (Strzelecki, 2023; Cotton et al., 2023). The present findings align with this literature by demonstrating that AI tool engagement among students is neither universal nor uniform.

Importantly, the observed variation in AI use underscores that availability alone does not ensure adoption. Even in contexts where generative AI tools are widely accessible, students differ in their willingness and ability to integrate these tools into their academic practices. This pattern reinforces conclusions from prior studies that emphasise the role of contextual, educational, and normative factors—rather than mere technological access—in shaping student engagement with AI (Dos, 2025).

Taken as a whole, the findings suggest that patterns of AI tool use among students should be interpreted as reflecting diverse experiences, motivations, and constraints. This heterogeneity provides important context for understanding why moderate levels of AI literacy and confidence may coexist with both frequent and minimal AI use within the same cohort.

5.4. Perceived Institutional Readiness and Uncertainty

Perceptions of institutional readiness to use artificial intelligence emerged as a distinctive feature of the findings, characterised primarily by high levels of uncertainty among students. A substantial proportion of respondents reported being unable to judge whether universities or their managers were prepared to use AI in higher education. This pattern distinguishes perceived institutional readiness from individual-level confidence or usage, suggesting that uncertainty itself is a meaningful empirical outcome rather than a simple absence of opinion.

This finding aligns with prior research indicating that institutional approaches to AI in higher education are often fragmented, rapidly evolving, and unevenly communicated. Journal-based studies examining institutional AI policies report that while many universities have introduced guidelines or statements related to generative AI, these are frequently developed in response to immediate concerns and may not be clearly visible or accessible to students (Cotton et al., 2023; Dodds et al., 2024; Perkins et al., 2025; Dwivedi et al., 2023). As a result, students may have limited awareness of institutional strategies even when formal policies exist.

Importantly, the prominence of “Cannot decide / No experience yet” responses suggests that uncertainty should not be interpreted as disengagement or indifference. Rather, existing literature points to a visibility gap between institutional decision-making and student experience, whereby AI-related policies and preparedness are discussed at governance or leadership levels but are not consistently translated into student-facing guidance (Dodds et al., 2024; Crawford et al., 2021). The present findings are consistent with this interpretation, as uncertainty was more prevalent than strong positive or negative assessments of institutional readiness.

The contrast between moderate student confidence in personal AI use and uncertainty regarding institutional preparedness further reflects patterns reported in earlier studies. Research on higher education responses to generative AI has noted that students often adapt quickly to emerging tools, while institutional processes for policy development, training, and communication progress more slowly (Dos, 2025). In this context, student uncertainty may reflect the pace and opacity of institutional change rather than a lack of institutional activity per se.

Taken together, the findings indicate that perceived institutional readiness is not simply a mirror of student AI literacy or usage. Instead, it represents a distinct dimension of the student experience, shaped by the extent to which institutional approaches to AI are visible, coherent, and communicated effectively to learners.

5.5. Triangulating Student and Leadership Perspectives on AI Readiness

While the present study focuses on students’ perceptions of AI literacy, use, and institutional readiness, these findings can be conceptually contrasted with qualitative evidence from higher education leaders reported in related research. Such triangulation does not constitute an empirical comparison between datasets, but rather provides complementary insight into how AI readiness is understood across different stakeholder groups.

Qualitative findings reported by Moradimanesh et al. (2025) highlight substantial variation in leaders’ understanding of artificial intelligence and its implications for higher education. Leaders described uneven levels of AI awareness, with some demonstrating strategic or pedagogical engagement and others framing AI primarily as a student-facing tool rather than an institutional concern. This heterogeneity in leadership perspectives mirrors the moderate and uneven confidence reported by students in the present study, suggesting that variability in AI readiness is evident across both student and leadership populations.

Notably, leaders in the qualitative study also reported challenges related to institutional preparedness and communication, including difficulties in operationalising AI strategies and conveying clear guidance to academic communities (Moradimanesh et al., 2025). When viewed alongside the present findings, particularly the high proportion of students reporting uncertainty about institutional readiness, this alignment suggests that student uncertainty may reflect genuine structural and communicative gaps rather than a lack of interest or engagement.

The convergence of student-reported uncertainty and leader-reported challenges points to a potential misalignment between institutional intention and student perception. While leaders may be actively grappling with AI-related decisions at strategic levels, these efforts may not yet be sufficiently visible to students. From this perspective, uncertainty emerges as a shared outcome of transitional institutional contexts rather than as a deficit located solely at the student level.

In turn, this triangulated view underscores that AI readiness in higher education is not confined to individual competence or adoption, but is shaped by broader organisational processes and communication practices. By juxtaposing student perceptions with leadership accounts, the present study contributes a more nuanced understanding of how AI readiness is experienced and enacted across institutional layers.

This triangulation is intended to inform interpretation rather than to imply equivalence or direct comparison between datasets.

5.6. Implications for Higher Education

The findings of this study carry several implications for higher education institutions seeking to respond to the growing presence of artificial intelligence in teaching and learning. First, the coexistence of moderate student AI literacy with uneven confidence across different dimensions of use suggests that AI literacy development should be treated as multidimensional, rather than as a single competency. Efforts to support students may therefore benefit from addressing not only evaluative judgement and ethical awareness, but also practical skills and access to guidance.

Second, the observed heterogeneity in AI tool usage indicates that students engage with AI in diverse ways and to varying extents. This diversity suggests that institutional approaches assuming uniform adoption or readiness may fail to reflect actual student experience. Recognising variation in engagement may help institutions better understand why some students integrate AI extensively into their academic work, while others remain hesitant or disengaged.

Third, the prominence of uncertainty regarding institutional readiness highlights the importance of visibility and communication in institutional responses to AI. Even where institutions are actively developing policies or strategies, the findings suggest that such efforts may not be readily apparent to students. Clear, accessible, and student-facing communication may therefore play a critical role in shaping how institutional readiness is perceived.

Collectively, the results underscore that student engagement with AI unfolds within a broader institutional context that shapes confidence, uncertainty, and perceptions of preparedness. Addressing AI in higher education may thus require not only technical or policy-level responses, but also attention to how institutional intentions and resources are communicated and experienced by students.

5.7. Future Research

Future research could extend these findings by examining how student perceptions of AI awareness, fairness, and institutional support compare with those of university leaders and decision-makers. Longitudinal studies may also help to assess how student attitudes and levels of confidence evolve as institutional AI policies, training initiatives, and governance structures develop over time. In addition, mixed-methods or qualitative approaches could provide deeper insight into areas where respondents reported limited experience or uncertainty, helping to clarify how institutions might better support informed and responsible engagement with AI technologies.

6. Conclusion

This study provides a student-centred quantitative examination of awareness, self-reported literacy, and perceived readiness related to artificial intelligence use in higher education. The findings indicate that students engage actively with AI tools, yet do so with moderate confidence, uneven experience, and substantial uncertainty regarding institutional preparedness.

Across the sample, students reported stronger confidence in judgement-based aspects of AI use, such as evaluating appropriate versus inappropriate applications, than in practical skills or access to institutional support. Patterns of AI tool use were heterogeneous, with frequent users and non-users coexisting within the same educational context. Importantly, perceptions of institutional readiness were characterised by high levels of uncertainty, suggesting that student awareness of institutional approaches to AI remains limited or unclear.

By situating these findings within the broader literature and triangulating them conceptually with leadership perspectives reported elsewhere, the study highlights that AI readiness in higher education is not solely an individual-level phenomenon. Instead, it reflects interactions between student experience, institutional visibility, and communication practices. Uncertainty, in this context, appears to be a meaningful indicator of transitional institutional conditions rather than a deficit in student engagement.

Overall, this study contributes empirical evidence to ongoing discussions of AI adoption in higher education by foregrounding the student perspective and demonstrating how confidence, usage, and perceptions of readiness intersect. The findings provide a foundation for further research examining how institutional strategies, communication, and support structures shape student experiences with artificial intelligence.

7. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the findings are based on self-reported data, which may be influenced by respondents’ subjective interpretations, confidence levels, or social desirability. While self-report measures are appropriate for capturing perceptions and experiences, they do not provide objective assessments of AI literacy, skill proficiency, or institutional preparedness.

Second, the study employed a cross-sectional design, capturing student perceptions at a single point in time. As institutional policies, AI tools, and student exposure continue to evolve rapidly, perceptions of AI readiness and confidence may change. Longitudinal research would be required to examine how student awareness and perceptions develop over time in response to institutional actions or broader technological shifts.

Third, although the sample size was sufficient for descriptive analysis and internal consistency assessment, the findings may not be fully generalisable to all higher education contexts. Student experiences with AI may vary across institutions, disciplines, and national settings. The results should therefore be interpreted as illustrative of patterns within the sampled population rather than as representative of all students in higher education.

Fourth, the inclusion of a “Cannot decide / No experience yet” response option, while analytically valuable, resulted in varying numbers of valid responses across items. Although this approach enhanced transparency by capturing uncertainty explicitly, it limited the comparability of item-level statistics and precluded certain forms of inferential analysis.

Finally, the study focuses exclusively on student perspectives and does not include direct measures of institutional policies or leadership practices within the same dataset. While conceptual triangulation with leadership research was used in the Discussion to contextualise findings, future studies could benefit from integrated designs that examine student and institutional perspectives concurrently.

Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

The authors also acknowledge the use of AI-assisted tools to support refinement of the manuscript, with full responsibility for the final content retained by the authors.

Author Contributions

Davood Mashhadizadeh and Iman Moradimanesh contributed equally to the conceptualization, research design and scope of the study. DM designed the research questions, the questionnaire, and data collection instruments, and conducted the data analysis. IM contributed to the refinement of the research questions and the questionnaire, and coordinated data collection, facilitated participant recruitment, and ensured adherence to ethics protocol. Both authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for the specific purpose of this research.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymised dataset and supporting documentation for this study have been archived on the Open Science Framework (OSF) and assigned a persistent identifier (DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DHKWY). The dataset is currently under restricted access and will be made publicly available upon acceptance or publication of the article. All data were collected anonymously and contain no personal or identifiable information, in accordance with the approved ethics protocol.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Regent College London for institutional support and the students who participated in the study for their valuable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Cotton, D.R.E.; Cotton, P.A.; Shipway, J.R. Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2023, 61, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K.; Whittaker, M.; Elish, M.C.; Barocas, S.; Plasek, A.; Ferryman, K. AI Now Report 2021. AI Now Institute. 2021. Available online: https://ainowinstitute.org/AI_Now_2021_Report.pdf.

- Dos, I. A Systematic Review of Research on ChatGPT in Higher Education. Eur. Educ. Res. 2025, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Jung, J. Master's programmes at Sino-foreign cooperative universities in China: An analysis of the neoliberal practices. High. Educ. Q. 78, 236–253. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Koohang, A.; Raghavan, V.; Ahuja, M.; et al. Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: Honolulu HI USA, Apr 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradimanesh, I.; Mashhadizadeh, D.; Ahmad, A. Beyond the classroom: Building leadership capacity for AI in higher education. In OSF Preprints; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Ng, D.T.K.; Chu, S.K.W. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Literacy in Early Childhood Education: The Challenges and Opportunities. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.; Roe, J.; Postma, M.; Bishop, C. Institutional guidelines for generative artificial intelligence in higher education: Policy development and implementation challenges. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2025, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.; Tan, S.; Tan, S. ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. Students’ acceptance of ChatGPT in higher education: An extended UTAUT model. Innovative Higher Education 2023, 48, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Shehata, B.; Adarkwah, M.A.; Bozkurt, A.; Hickey, D.T.; Huang, R.; Agyemang, B. What if the devil is my guardian angel: ChatGPT as a case study of using chatbots in education. Smart Learn. Environ. 2023, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Marín, V.I.; Bond, M.; Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education – where are the educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Chu, X.; Chai, C.S.; Jong, M.S.Y.; Istenic, A.; Spector, J.M.; Liu, J.-B.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y. ChatGPT for education: A systematic review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 5, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).