Introduction

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly Generative AI (GenAI), is profoundly reshaping K–12 education. With the accelerated advancement and adoption of GenAI technologies, educational institutions are experiencing significant shifts in pedagogical approaches, resource curation, AI-powered platforms, and the competencies expected of students (Limna et al., 2022; UNESCO, 2023a). International bodies such as UNESCO and the World Economic Forum have called for integrating AI competencies into national curricula to ensure that future citizens can not only use AI tools but also engage with them critically, ethically, and creatively (Milberg, 2024; UNESCO, 2023b). These developments indicate that AI literacy—the ability to identify, understand, evaluate, and responsibly apply AI technologies—is becoming a core educational priority and a vital 21st-century skill (Hossain, 2025a; Voulgari et al., 2022).

Beyond technical proficiency, AI literacy encompasses cognitive and ethical dimensions such as contextual awareness, data integrity, transparency, and responsible use (UNESCO, 2023a; Voulgari et al., 2022). AI literacy can be viewed as an evolution of established information literacy paradigms within librarianship, extending traditional skills of locating, evaluating, and using information ethically into the context of algorithmic systems and machine-generated content. Scholars increasingly argue that cultivating such literacy promotes not only technological fluency but also critical agency and optimism toward AI’s societal role (Hollands & Breazeal, 2024).

Within this evolving educational landscape, school librarians, also known as teacher-librarians and school library media specialists—historically stewards of information literacy—are uniquely positioned to lead AI literacy efforts. Their expertise in fostering digital literacy, media literacy, academic integrity, and copyright literacy (Hossain, 2020; Merga, 2022; Wright et al., 2024) aligns with the demands of teaching AI citizenship and promoting ethical engagement with GenAI-generated content (Hossain, 2025a; Oddone et al., 2024). Yet, as AI reshapes library operations—from cataloging to personalized learning—librarians face a dual mandate: to adopt AI tools themselves and to guide students and teachers in navigating the ethical complexities of AI (IFLA, 2020; Softlink Education, 2024).

With libraries becoming increasingly reliant on AI and GenAI to deliver services and manage information, the role of AI-literate librarians will only become more paramount (Cox, 2023), with school librarians as no exception. However, emerging research indicates that while librarians acknowledge AI’s educational potential, many remain uncertain about their readiness to integrate or teach it (Chepchirchir, 2024; Gültekin & Kavak, 2025; Huang, 2024). In school library contexts, barriers such as limited professional development, inconsistent institutional policy, and ethical ambiguity continue to constrain effective AI adoption (Softlink Education, 2024; Wong & Chiu, 2025). These challenges highlight a pressing need to explore how school librarians perceive their AI literacy, confidence and readiness, and how such perceptions shape their engagement with emerging AI tools—a conceptual lens through which to interpret the gaps identified in our findings.

Research Rationale

As GenAI becomes increasingly embedded in K–12 educational environments, the role of school librarians is undergoing a profound transformation (Oddone et al., 2024; Wong & Chiu, 2025). Scholars such as Hossain (2025a), Hutchinson (2024), and Yi et al. (2024) have highlighted the expanding responsibility of school librarians in fostering inquiry-based learning and cultivating essential competencies such as information literacy, digital citizenship, AI literacy, and AI citizenship. Globally, professional bodies, including the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA, 2020), the American Library Association (ALA, 2019), and the International Association of School Librarianship (IASL, 2025), advocate for libraries to lead in promoting AI literacy, emphasizing their role in democratizing access to emerging technologies. Yet, despite growing policy momentum, the lived experiences and contextual challenges of librarians in translating these visions into classroom or library practice remain largely underexplored, particularly across non-Western contexts.

As school librarians shift from a traditional focus on information literacy toward broader domains such as digital and media literacy (Bauld, 2023), AI literacy emerges as the next critical frontier. Milberg (2024) and Williams (2024) similarly argue that education systems must move beyond digital literacy and embrace AI literacy as a core educational priority. Building on this evolving mandate, Wright et al. (2023) observed that school librarians demonstrated adaptability and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, redefining their roles to meet shifting instructional demands and positioning themselves to thrive as K–12 learning environments continue to diversify. This adaptability provides a strong foundation for navigating the next wave of change driven by AI integration. However, as Hutchinson (2024) cautions, school librarians are required to overcome lingering reluctance and uncertainty surrounding AI adoption and position themselves as key facilitators in helping students and teachers navigate AI’s ethical, pedagogical, and technical complexities.

Despite the growing discourse on AI in education, few empirical studies have systematically examined how school librarians perceive and enact AI literacy across diverse international contexts. Most existing research remains localized or conceptual and focuses on higher education or policy-level frameworks rather than practitioner experiences in K–12 settings. This study, therefore, addresses a double gap: first, by providing empirical evidence on the current state of AI literacy, confidence, and readiness among school librarians; and second, by adopting a cross-continental comparative perspective that captures regional variations and global trends. Together, these dimensions position the study as one of the first to map the international landscape of AI literacy in school librarianship.

Understanding these dimensions is essential for informing future professional development, policy, and curriculum design in K–12 education aimed at empowering school library professionals in the age of GenAI. Accordingly, this study seeks to address this gap by:

Exploring the current level of AI literacy among school librarians internationally, including their familiarity, confidence, and overall readiness to integrate AI and GenAI tools used in K–12 education;

Understanding the extent and nature of school librarians’ engagement with AI technologies in professional practice, including instructional, administrative, and library management contexts;

Investigating differences in AI literacy and engagement across demographic and contextual factors such as region, gender, educational background, school type, and professional experience; and

Learning the key challenges and barriers that limit AI readiness and integration in K-12 schools.

These purposes collectively guided the study’s mixed-methods design and subsequent interpretation of results, bridging quantitative measures of literacy and readiness with qualitative insights into the librarians’ professional experiences, challenges, and aspirations.

Literature Review

The Emergence of AI in Education

The rapid advancement of GenAI tools such as ChatGPT has reshaped pedagogical practices, resource accessibility, and learning paradigms in K–12 education (Limna et al., 2022). A growing number of international organizations, including UNESCO (2023b), have called for the integration of AI literacy skills into national curricula. This aligns with the World Economic Forum’s advocacy for embedding AI in education to develop a workforce capable of critically engaging with emerging technologies (Milberg, 2024). Similarly, the OECD (2025) plans to include Media and Artificial Intelligence Literacy (MAIL) in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) starting in 2029, signaling a growing recognition of AI proficiency as an essential global competency.

Emerging research highlights the urgency of embedding AI literacy within educational ecosystems. Hornberger et al. (2023) and Milberg (2024) note that students, many of whom already interact with AI tools on a daily basis, anticipate that AI will play a central role in their future careers. Williams (2024) describes AI literacy as a foundational skill across all levels of education. Echoing this, Hossain (2025a) advocates for cultivating critical AI literacy and AI citizenship, encouraging students to engage critically, ethically, and responsibly with AI technologies.

Studies have also reported that the effectiveness of AI integration in schools depends heavily on teachers’ readiness and competencies. Khazanchi and Khazanchi (2025) and Hossain et al. (2024) emphasize that teachers must develop AI competencies to foster 21st-century skills and model responsible AI engagement. Yet persistent barriers remain. Su et al. (2023) report significant gaps in teachers’ AI knowledge, limitations in curriculum design, and the absence of pedagogical guidelines. Northeastern University and Gallup (2019) found that many educators lack the conceptual understanding needed to teach with or about AI. These findings underscore the necessity of professional development and institutional support to empower educators as facilitators of AI literacy.

Global Policy Frameworks and AI Literacy Integration

In response to the growing influence of GenAI, governments and international organizations have introduced policies and frameworks to enhance citizens’ AI literacy and ensure its ethical use. As of September 2025, 701 countries had released national AI policies or strategies (OECD.AI, 2021; 2025). These initiatives acknowledge AI’s benefits while establishing regulations to safeguard ethical use, privacy, and equity. Notably, UNESCO (2023b) developed AI competency frameworks for teachers and students, and the European Commission (2024) introduced the first comprehensive legal framework for AI.

Several countries, including China, Finland, Portugal, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have formally embedded AI literacy into their K–12 curricula (UNESCO, 2022). Australia launched the Australian Framework for Generative AI in Schools to guide responsible use (Department of Education, 2023). Beginning in the 2025–2026 academic year, the UAE will make AI literacy compulsory across K–12 (McFarland, 2025). These developments illustrate that AI literacy extends beyond technical competence to include civic, ethical, and cultural dimensions central to educational equity and innovation. When guided by ethical frameworks, AI integration can promote learner-centered pedagogy, critical thinking, and inclusivity (Hossain, 2025a; Luckin et al., 2022; UNESCO, 2023b).

AI Adoption and Literacy Among School Library Professionals

Within K–12 education, school librarians are uniquely positioned to translate AI policy aspirations into practice. Their expertise in fostering digital, media, and information literacy naturally aligns with the broader aims of AI literacy and ethical technology use (Merga, 2022; Oddone et al., 2024). Recent practitioner reports and case studies show that school librarians are actively exploring AI integration in their daily work. The 2023 Softlink Australia School Library Survey revealed that many teacher-librarians are experimenting with generative AI for administrative and instructional purposes, using tools like ChatGPT to automate communications, design lessons, and introduce AI-related content into digital-literacy instruction (Softlink Education, 2024). In the United States, Bauld (2023) described a school librarian who utilized ChatGPT to generate book recommendations and teaching prompts while navigating the challenges of factual accuracy and bias.

Practical guidance for AI integration in school libraries is gradually emerging. Beyond conceptual discussions, several practitioners and researchers have begun documenting concrete models of implementation. Seales (2025) offers strategies for embedding AI tools responsibly into library services and classroom collaboration, emphasizing policy alignment, ethical safeguards, and equitable access. Building on this, Wong and Chiu (2025) present an empirical case study of an international school library that incorporated a structured AI-literacy program into its information-skills curriculum. Through inquiry-based learning, students explored both the capabilities and ethical implications of generative AI, illustrating how librarians can scaffold critical understanding rather than merely introducing new technologies. In another illustration, a Qatar-based international school librarian describes developing a “Centaur Librarianship” model, using ChatGPT to streamline shelf-to-spreadsheet inventory tasks and demonstrating a productive human–AI partnership (“human in the loop”) in library management (McKim).

Taken together, these examples highlight a global shift from conceptual advocacy toward practical experimentation, showing how school librarians can serve as critical AI literacy facilitator, ethical mediators and innovators in AI integration. They recognize AI’s potential to transform information services, pedagogy, and resource management, while also highlighting enduring challenges—limited professional development, inconsistent institutional support, and ethical uncertainties. These challenges mirror broader educational trends, where enthusiasm for AI often outpaces structural readiness (Su et al., 2023). Strengthening AI literacy among school librarians is therefore critical for ensuring that K–12 schools can cultivate students who think critically, act responsibly, and engage confidently in an AI-augmented world.

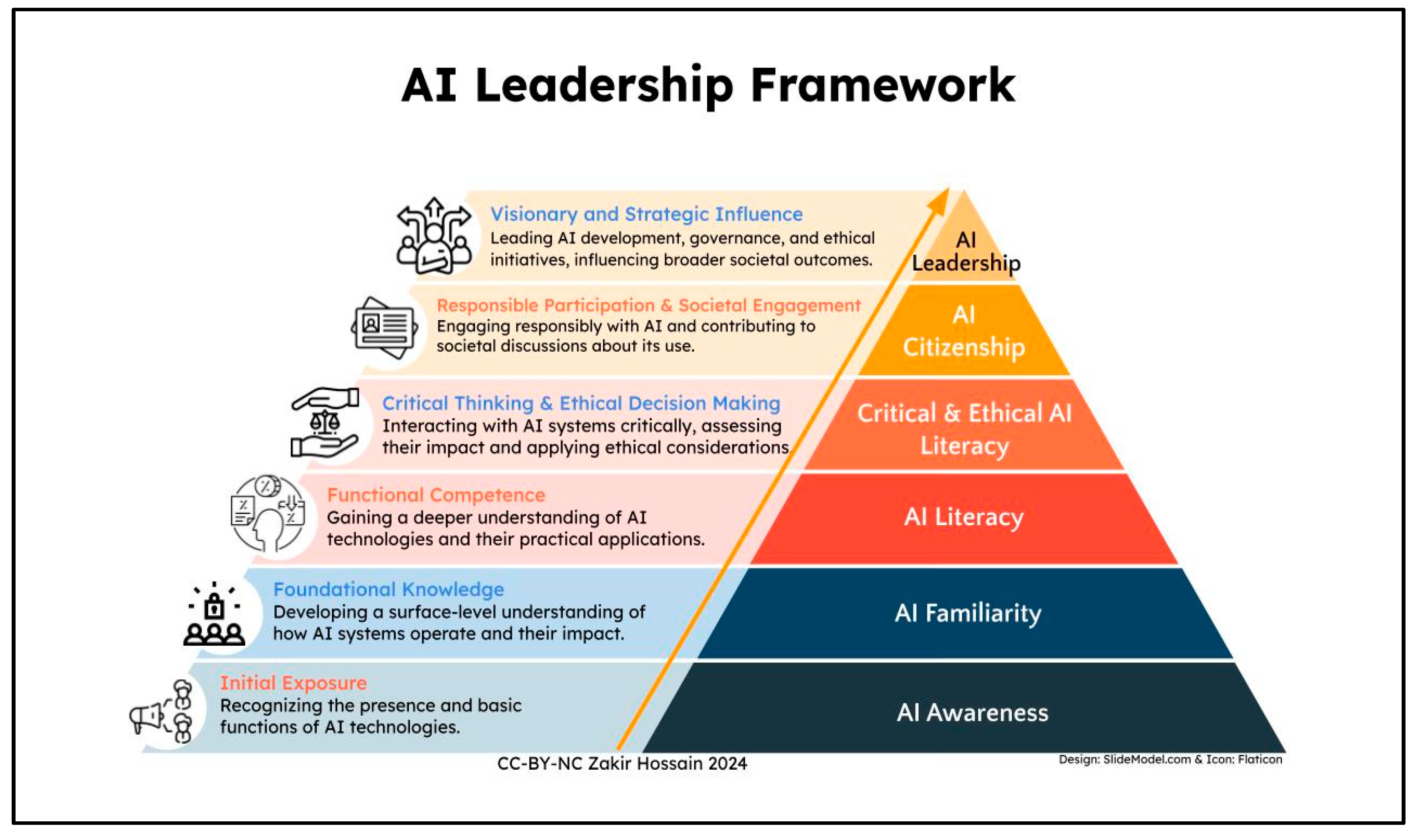

Against this backdrop, the present study explores school librarians’ AI literacy, engagement, and readiness across global contexts, focusing on their familiarity with AI tools, confidence in instructional integration, professional development needs, and ethical concerns related to academic integrity, privacy, and trust. Addressing this gap is essential for developing evidence-based professional learning models and institutional frameworks that position school librarians as leaders in AI literacy education. Guided by the AI Leadership Framework (Hossain, 2025b) (see Figure 3), the study interprets patterns of familiarity, confidence, and institutional support through a developmental lens of professional growth. The following section outlines the mixed-methods exploratory design adopted to investigate these relationships.

Research Methodology

Research Design

This study adopted a mixed-methods exploratory design to investigate school librarians’ AI literacy, readiness, and professional engagement with AI technologies across global contexts. Mixed-methods research integrates quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of complex educational phenomena (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). The exploratory design was deemed suitable due to the novelty of the topic and the lack of established frameworks addressing AI literacy among school librarians, allowing the researchers to examine emerging patterns and relationships in a flexible, data-driven manner. This approach enabled the identification of contextual nuances and developmental trends in an area that has not yet been extensively theorized (Stebbins, 2001; Stewart, 2025).

Instrument Development and Pilot Testing

The questionnaire was informed by an extensive literature review, expert feedback, and the authors’ professional experience in school librarianship and LIS educational research. The first and second authors bring extensive backgrounds in K–12 education and school library practice across diverse global contexts, which contributed to the development of contextually relevant and globally applicable survey items. The questionnaire employed both closed-ended—Likert scales, checkboxes, multiple-choice—and open-ended questions to capture nuanced responses from school librarians.

A pilot study was conducted with 12 school librarians (nine from international schools, two from private schools, and one from a public school), as well as one LIS faculty member. Pilot feedback led to several refinements, including the clarification of key terms such as AI familiarity—defined as general awareness or recognition of AI technologies—and AI literacy, defined as a deeper understanding of AI principles, implications, and the ethical application of AI tools. All relevant terms, study objectives, and data privacy protocols were clearly defined for participants within the survey.

Besides demographics and background information, the survey questions were divided into five domains to explore the multidimensional nature of AI literacy among school librarians. In addition, the survey items were mapped onto relevant learning domains, reflecting cognitive, behavioral, affective, and psychomotor dimensions:

AI Familiarity and Literacy (Cognitive Domain): Participants self-rated their AI literacy and familiarity using 5-point Likert scales. Multiple-choice items were included to assess understanding of core AI concepts and functions.

Application and Usage of AI Tools (Behavioral Domain): This section examined the personal and professional use of AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Bard, Bing), highlighting observable behaviors associated with technology adoption.

Instructional Confidence and Readiness (Affective Domain): Scaled items measured participants’ perceived confidence and readiness to explain AI concepts to students or colleagues, reflecting internal states such as values, motivation, and self-efficacy.

Instructional Practice (Psychomotor and Behavioral Domains): This section explored how participants incorporate AI into information literacy instruction and other standard library practices, capturing both action-oriented implementation and pedagogical engagement.

Perceived Challenges (Cognitive and Affective Domains): An open-ended question elicited reflections on institutional, pedagogical, and ethical barriers to enhancing AI literacy. Responses were analyzed thematically to identify common cognitive insights and affective responses.

Participants and Data Collection

The survey was conducted over an extended period, initially from May to November 2024 (n = 310), to accommodate participant availability across global regions and enhance response diversity. A further nine responses were collected between January and April 2025 from school librarians in the Netherlands, following the first author's keynote presentation. This flexible, staggered approach enabled the researchers to reach a broader and more geographically diverse group of participants, including those in underrepresented educational contexts. The questionnaire was disseminated globally through multiple channels, including:

Listservs of the International Association of School Librarianship (IASL) and the IFLA School Libraries Section.

National and regional school library associations and organizations.

Social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, and LinkedIn.

Professional networks of the research team.

Participation was voluntary and open to practicing school librarians, teacher-librarians, and library media specialists. No formal sampling frame was employed; instead, a purposive convenience approach was used to reach diverse global respondents. In addition to a detailed data privacy and ethics statement embedded in the Google Form, the study’s purpose was briefly outlined in the email invitations and social media posts used for distribution.

A total of 319 valid responses were received from over 50 countries. Notable response rates included the United States (71), India (42), Portugal (35) and Australia (34), with additional significant contributions from Canada, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (14 each), New Zealand (10), the Netherlands (9), Germany (8), and both Hong Kong and Hungary (6 each). Fewer than five responses were recorded from all other countries. In this study, we grouped countries by continent as shown in

Table 1. Respondents represented diverse genders, grade-level responsibilities (e.g., primary, middle, and high schools), and institutional contexts, including public, private, and international school systems.

Data Analysis

In this study, quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed to provide a comprehensive insight into school librarians' AI literacy, readiness, engagement, and their challenges of integrating and promoting AI literacy in their contexts.

The quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS and Google Sheets, with visualizations produced in Flourish Studio. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were used to summarize the distribution of responses across demographic variables and to identify emerging trends. To explore relationships and differences between variables, inferential statistical tests—including an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)—were conducted. The ANOVA examined whether respondents’ self-reported AI literacy levels significantly differed based on demographic factors such as continent, gender, grade-level responsibility, school type, education, and years of experience.

Open-ended responses were analyzed using thematic analysis to capture participants’ perceptions, challenges, and contextual insights. To assist with the coding process, we used ChatGPT (OpenAI) as an AI-supported analysis tool. Following emerging scholarship on the use of GenAI in qualitative research (Lee et al., 2024; Naeem et al., 2025), ChatGPT was prompted with anonymized response sets to suggest preliminary clusters of ideas. These AI-generated clusters were then critically reviewed, refined, and validated by the authors following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase approach to thematic analysis. In this process, ChatGPT functioned as an assistant coder—supporting the identification of initial patterns—while the researchers ensured interpretive accuracy and thematic coherence.

This mixed-methods approach enabled the integration of statistical and emergent thematic findings, offering a more holistic view of global school librarians’ engagement with AI technologies. The emergent themes were organized under four broad categories aligned with the study’s objectives. The AI Leadership Framework was not used to pre-determine codes but was later employed to interpret the emergent themes and contextualize developmental patterns of AI engagement among school librarians.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in full alignment with the principles outlined in the ‘European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity’ (All European Academies, 2023). We adhered to core ethical standards, including voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, and the confidentiality of respondents' data. Participants were informed about the purpose of the research, data usage policies, confidentiality measures, and their right to withdraw at any stage. These measures ensure transparency, respect for participants' autonomy, and the responsible handling of all collected data.

Findings and Analysis

Demographic Overview of the Respondents

The demographic profile of the 319 school librarians presented in

Table 1 reflects a diverse and globally distributed sample, with the majority based in Europe (33.2%) and North America (27.6%), followed by Asia (21.9%) and Oceania (14.1%). Gender distribution is heavily skewed, with females comprising 85.6% of respondents, aligning with known trends in school librarianship, while male representation remains low (11.9%). Grade-level responsibilities are well-balanced across educational stages, with the highest proportions of school librarians working in K–8 (24.8%) and high school (24.8%) settings, and a notable 21.9% covering both middle and high school (Grades 6–12), followed by 19.7% responsible for whole school settings (K-12). Over half of the respondents (53%) are employed in public schools, with 21.9% in international and 18.2% in private schools, ensuring varied institutional contexts.

In terms of qualifications, nearly half of the participants (46.1%) hold a master’s degree in LIS, 21.0% possess a postgraduate certificate or diploma in LIS, and an almost equal and notable minority (19.5%) lack formal credentials, reflecting a broad spectrum of academic preparation. The participants' professional experience is quite evenly distributed, with nearly equal representation across the different ranges of years of experience, particularly among those with 1–5 (20.7%), 6–10 (21.3%), and 11–15 (20.7%) years of service. This demographic spread enhances the study’s generalizability and provides rich insight into the AI literacy, readiness, and engagement of a broad cross-section of school librarians globally.

AI Literacy of School Librarians

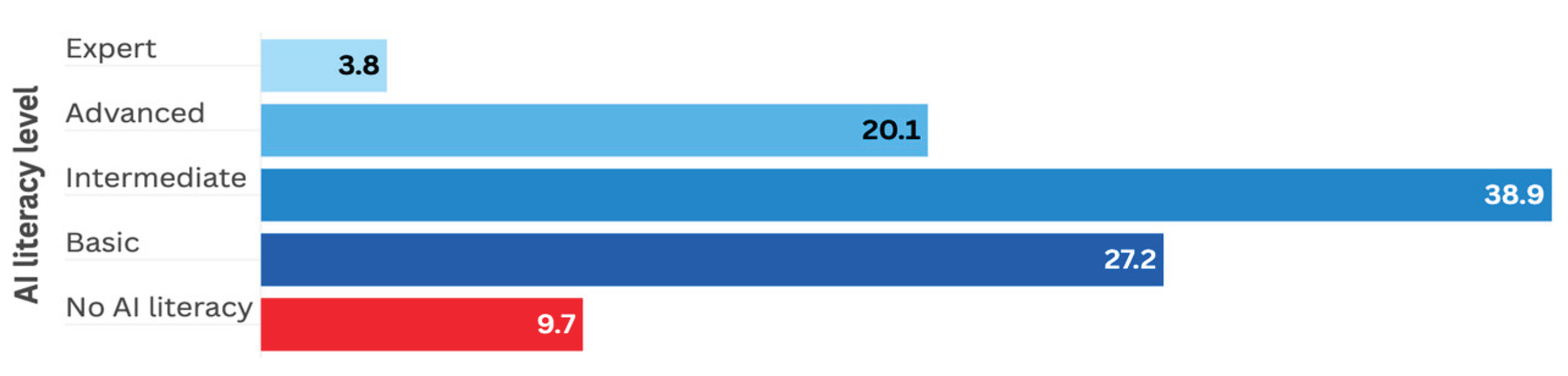

Figure 1 illustrates the self-reported AI literacy levels of school librarians, highlighting a spectrum of competency across the profession. The largest proportion of respondents (38.9%) identified as having an intermediate level of AI literacy, indicating a moderate understanding of navigating AI tools and capacity for AI literacy instruction. Over one-quarter (27.6%) reported a basic level of literacy, suggesting foundational awareness but limited application capabilities. Notably, 20.1% of school librarians considered themselves to have advanced AI literacy, reflecting strong engagement and comprehension, while only 3.8% identified as experts, indicating a scarcity of high-level proficiency in the field. Surprisingly, 9.7% of respondents reported having no AI literacy at all. These figures suggest that while a significant portion of school librarians are beginning to engage meaningfully with AI, there remains a critical need for targeted professional development to raise overall competency and support ethical, informed integration of AI in K-12 schools' information and/or digital literacy curricula.

School Librarians' AI Literacy Based on Demographic Variables

The ANOVA test results in

Table 2 assess whether the school librarians’ AI literacy levels differ significantly across various demographic variables. Of the six variables examined—location (by continent), gender, grade-level responsibility, school type, education, and experience—only educational qualification demonstrated a statistically significant effect on AI literacy levels (F = 2.715, p = 0.007). This finding indicates that the level of formal education, particularly in LIS or related fields, is a critical determinant of AI literacy among school librarians. Considering this outcome, it is noted with some trepidation that

Table 1 shows almost one-fifth of respondents do not have a formal qualification in librarianship or education.

Although the grade-level responsibility approached significance (p = 0.056), suggesting potential differences based on the grade levels served (e.g., K–8 vs. high school), it did not reach the conventional threshold for statistical significance. Other variables, such as continent, gender, school type, and years of experience, showed no statistically significant differences, indicating that these factors may not substantially influence AI literacy levels in this sample. These findings highlight the importance of formal educational qualifications in shaping school librarians’ AI readiness and highlight the need to incorporate AI literacy into pre-service and continuing LIS education to build consistent competencies across all school and library settings.

School Librarians' Conceptual and Pedagogical AI Competency

Table 3 offers insights into school librarians' conceptual and pedagogical competency in AI. A majority of respondents (69.9%) reported the ability to explain real-world AI applications, and 70.2% discussed ethical considerations, highlighting a strong awareness of AI's societal role and moral implications. However, when it comes to instructional competencies, the percentages decline notably. Only 47.3% felt capable of teaching students how to use AI tools. In comparison, 45.5% indicated they could identify and discuss AI-related biases—both essential for fostering critical and ethical AI literacy and digital citizenship. Far fewer respondents (28.8%) could evaluate AI-powered educational tools or identify whether digital tools incorporate AI (31.3%), signaling a gap in technical literacy.

Similarly, only 44.8% reported confidence in guiding students through ethical AI-supported research projects. The 3.7% who selected ‘none of the above’ point to a small but notable cohort lacking any meaningful understanding of AI. Overall, the findings suggest that while general awareness is fairly widespread, significant gaps remain in applied and instructional AI competencies—indicating the need for structured professional development focused on the ethical, technical, and pedagogical dimensions of AI competencies in school libraries.

School Librarians' Consolidated AI Competency

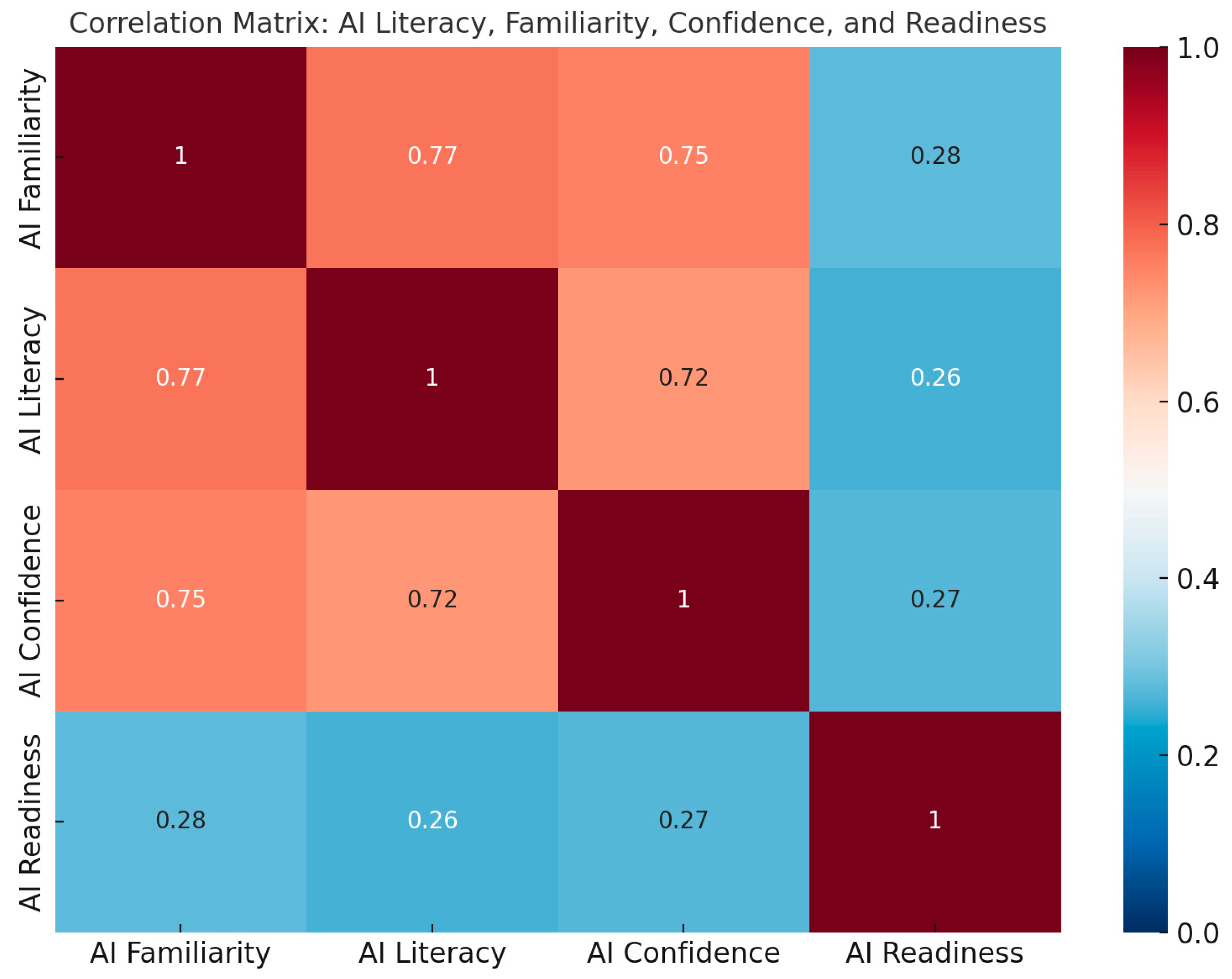

The correlation analysis illustrated in

Figure 2 revealed strong, statistically significant relationships of AI familiarity, AI literacy, AI confidence and AI readiness among school librarians, indicating that increased exposure to AI tools is closely associated with higher conceptual understanding and confidence in using AI (r = .75 to .77, p < .01). Accordingly, school librarians who are more familiar with AI tools are also more literate in AI concepts and more confident in applying AI in their roles. This aligns with Bandura’s (1977) theory of self-efficacy, which posits that repeated exposure fosters competence and confidence. These findings also support the idea that familiarity may act as a foundation for both cognitive (literacy) and affective (confidence) dimensions of AI competence. AI readiness demonstrated moderate but significant correlations with each of the other variables (r = .26 to .27, p < .01), suggesting that readiness is a multifaceted construct influenced by familiarity, knowledge, and affective disposition.

The strong triad of AI familiarity-literacy-confidence indicates that school librarians with hands-on AI experience are better positioned to teach AI literacy. However, weak readiness correlations suggest many lack the skills to scale these efforts. For example, librarians may understand AI ethics but lack effective strategies for integrating it into their curriculum. These findings underscore the importance of continuous, integrated professional development that simultaneously enhances school librarians’ practical exposure, conceptual literacy, and confidence to foster comprehensive AI readiness in educational contexts.

School Librarians AI Engagement

The data in

Table 4 reveal that school librarians exhibit varied levels of engagement with AI tools in their professional practice. ChatGPT emerges as the most frequently used tool, with 38.4% of respondents reporting regular use, indicating strong familiarity and confidence in conversational AI for information retrieval, content creation, or instruction. Other tools, such as Bing (11.2%), Perplexity AI (9.2%), and Gemini (7.4%), show moderate use, reflecting a growing interest in generative search and assistant platforms. However, low usage of research-focused tools like Connected Papers, Elicit, and ResearchRabbit implies limited integration of AI in academic exploration and knowledge mapping. Notably, 10.6% of librarians do not use any AI tools, which may point to gaps in digital literacy or access.

The data in

Table 5 suggest a cautious yet emerging adoption of AI tools among school librarians, accompanied by notable disparities in application. While 10.8% integrated AI into information literacy lessons and 10.6% explored AI to stay technologically updated, core library functions, such as cataloging (3.4%) and usage analytics (3.1%), remain underutilized, suggesting a gap between AI’s potential and its practical implementation.

The emphasis on student-facing tasks—research assistance (9.4%) and digital content creation (10.4%)—highlights librarians’ prioritization of pedagogical support over operational efficiency. However, low engagement in personalized recommendations (6.8%) and accessibility enhancements (5.3%) signals missed opportunities for inclusive, tailored services. Notably, 6.2% of respondents reported not using AI tools at all, indicating ongoing barriers, perhaps due to a lack of training, institutional support, or awareness.

Table 6 shows that 45.2% of school librarians integrated AI literacy into their information literacy/library curriculum to some degree, though only 10.7% did so ‘extensively’ or ‘to a great deal’. A significant proportion (34.5%) engaged minimally or ‘to some extent’, while 26% plan to adopt AI literacy but have not yet done so. Nearly a quarter (24.8%) did not incorporate AI literacy at all, and 4.1% lack familiarity with AI tools, rejecting their use entirely. The data highlight a disparity between intent and action, with most school librarians remaining in early or inactive stages of integrating AI literacy into their existing information literacy, digital literacy, or library curriculum/lessons, depending on which model each school follows. This disparity between intention and implementation reflects the systemic challenges reported in the qualitative findings, where institutional constraints, insufficient training, and competing responsibilities limited school librarians’ capacity to embed AI literacy meaningfully within existing curricula.

Discussion and Implications

This study presents one of the first large-scale, cross-continental examinations of school librarians' AI literacy, readiness, and engagement with AI tools, shedding light on the evolving role of school librarians in an increasingly AI-integrated K–12 educational landscape. The findings reveal that while many school librarians demonstrate moderate familiarity and confidence in using AI tools—especially widely accessible platforms such as ChatGPT—their readiness to implement AI in teaching remains limited. This readiness gap echoes concerns in prior literature (Huang, 2024; Chepchirchir, 2024; Wong & Chiu, 2025) and reinforces the claim that technical awareness does not necessarily translate into pedagogical integration or leadership in AI literacy. As Hossain (2025b) and Oddone et al. (2024) assert, the shift from digital to AI literacy requires not only awareness but also structured professional support and leadership cultivation.

The statistically significant correlations among AI familiarity, literacy, confidence, and readiness suggest a mutually reinforcing relationship, highlighting that investment in one dimension could catalyze improvements in others. However, the relatively low percentages of school librarians using AI tools for instructional planning, collaboration, or student engagement suggest structural limitations such as unclear policy, insufficient training, and uncertainty around ethical AI use. This finding aligns with challenges identified by Su et al. (2023) and Chepchirchir (2024), including gaps in curriculum design, the absence of guiding frameworks (Hossain, 2025a), and teacher reluctance (Hutchinson, 2024). These patterns are further substantiated by qualitative data, which reveal widespread concerns about institutional resistance, time constraints, lack of professional development opportunities, and the complexities of guiding students in the ethical use of AI.

Importantly, the ANOVA results indicate that formal education—particularly qualifications in LIS—is the only demographic factor that significantly influences AI literacy. This highlights the importance of AI competencies, both technical and ethical, in LIS education and continuing professional development. When viewed through the lens of the AI Leadership Framework, this finding suggests that formal LIS education primarily supports the foundational awareness stage of AI literacy, where professionals gain conceptual and cognitive understanding of AI technologies. However, progression toward the applied and leadership stages requires additional experiential and institutional support, including professional learning, policy alignment, and opportunities for collaborative practice. In other words, while academic preparation may cultivate awareness, it does not necessarily foster the higher-order competencies—such as ethical judgment, pedagogical innovation, and strategic leadership—that define mature AI literacy. This interpretation aligns with the framework’s developmental continuum, which emphasizes that AI leadership evolves incrementally from awareness to ethical and instructional transformation.

Rather than employing the AI Leadership Framework as a predetermined analytical model, the emergent themes in this study organically aligned with its developmental continuum. This alignment provides preliminary empirical support for the framework’s relevance to school librarianship, suggesting that AI leadership evolves from foundational awareness toward ethical and instructional transformation. The observed correlations among familiarity, literacy, and confidence mirror the framework’s foundational tiers. At the same time, the identified barriers—such as limited institutional support and ethical uncertainty—highlight the challenges of advancing toward the leadership and innovation stages. Collectively, these findings offer an evidence-based elaboration of the framework’s stages, grounding its conceptual progression in global practitioner data.

Thematic analysis also revealed that librarians are often expected to lead AI-related conversations and initiatives without institutional backing, resulting in professional frustration and uneven adoption. As one respondent reflected, “I offer lessons, but not everyone takes me up on that offer … admin does not allow time for me to teach the teachers.” Ultimately, the findings affirm the role of school librarians not just as resource facilitators, but as ethical AI stewards in K–12 education. However, this vision will remain aspirational unless supported by robust institutional mandates, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and targeted professional learning ecosystems.

The incorporation of learning domains into the research design offers a valuable lens for interpreting the findings. AI Familiarity and Literacy (cognitive domain), AI Tool Usage (behavioral domain), Instructional Readiness (affective domain), and Instructional Practice (psychomotor and behavioral domains) reflect interdependent yet unevenly developed areas of AI preparedness among school librarians. The statistically significant correlations between AI familiarity, literacy, and confidence suggest a strong interrelationship between cognitive and affective domains, supporting Bandura’s (1977) self-efficacy theory. However, the weaker link between these domains and actual instructional practice indicates a bottleneck in the psychomotor domain, where knowledge and motivation are not yet being effectively translated into regular pedagogical integration.

Moreover, ethical concerns (“Will I/students use AI responsibly?”) surfaced as a distinct barrier, decoupling technical confidence from implementation intent. We therefore recommend extending self-efficacy models to include an “ethical efficacy” dimension—capturing confidence in applying AI responsibly—to predict better which educators will move from experimentation to sustained, value-aligned adoption. This nuance is especially critical in the context of AI’s ethical risks, including misinformation, privacy, and bias.

The qualitative findings reinforce these conclusions. Institutional barriers, lack of policies, and time constraints hinder the application of behavioral and psychomotor skills; educator mistrust and fear inhibit affective engagement; and inconsistent training affects cognitive growth. These intersecting barriers point to the need for systemic solutions. First, system-level policy reform—by governments, institutions with LIS programs, education departments, and library organizations—is required to mainstream AI literacy into professional standards for school librarians. Global and national library associations, as well as education departments, must advocate for integrating AI competencies into job descriptions, professional evaluation metrics, and school-level expectations. Second, institutional investment in targeted professional development is essential. This includes not just access to tools, but opportunities for critical reflection, scenario-based training, and ethical case studies tailored to the school library context.

Our findings indicate that while many school librarians report moderate familiarity and confidence with AI, their readiness to integrate AI into teaching practice remains limited. This mismatch highlights the need for a developmental framework that bridges awareness with practice. The AI Leadership Framework provides such a pathway. The framework offers a developmental continuum—spanning foundational awareness, applied practice, and transformational leadership—that mirrors the patterns observed in this study. By aligning the survey results and qualitative themes with this framework, the study demonstrates how professional growth in AI literacy unfolds across cognitive, behavioral, and ethical dimensions, ultimately equipping school librarians to become leaders in AI integration and responsible innovation.

By aligning our survey results with the AI Leadership Framework, we propose a way forward for supporting school librarians not just as competent users of AI, but as leaders who can guide colleagues and students in responsible AI use. Similar to LaFlamme’s (2025) staged model for librarian AI literacy and Mills et al.’s (2024) K–12 AI literacy leadership framework, our adaptation emphasizes progression from basic familiarity to ethical, instructional, and institutional leadership. The four qualitative themes can be understood as developmental constraints within the AI Leadership Framework. Institutional barriers slow advancement to the leadership stage; educator attitudes impede early awareness and adoption of best practice; limited professional development resources restrict capacity building; and ethical dilemmas challenge the transformational tier. Framing these barriers through the framework clarifies that professional learning in AI literacy is a staged process dependent on both individual competence and systemic enablement.

Figure 3.

AI Leadership Framework. (Hossain, 2025b; adapted with permission).

Figure 3.

AI Leadership Framework. (Hossain, 2025b; adapted with permission).

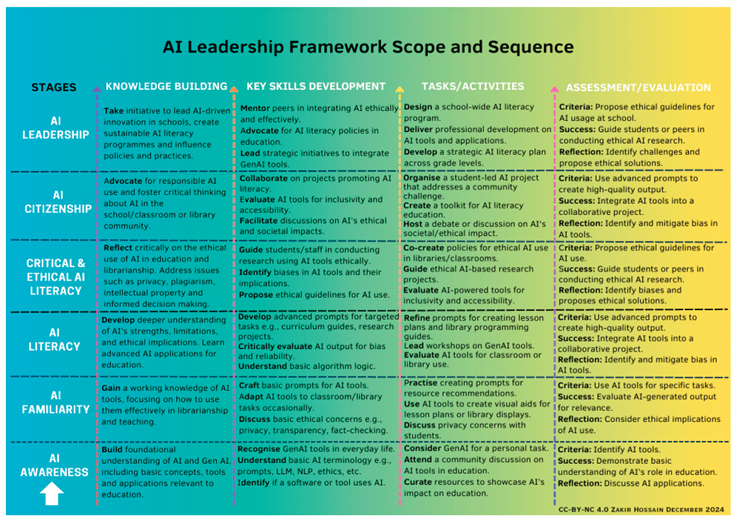

The framework also emphasizes using a scope-and-sequence map (see

Table 6) for professional learning that addresses foundational familiarity, ethical literacy, instructional integration, and AI-driven innovation. It is designed to equip school librarians and teacher librarians not only as competent users but also as critical AI leaders who can support student learning, guide teachers, and contribute to school-wide AI integration.

Limitations 2025. This means that caution had to be exercised against overgeneralization when interpreting the findings. Future studies should triangulate survey data with qualitative research methods, including in-depth interviews, focus groups, and case studies.

Additionally, regional disparities in response rates may under-represent the experiences of school librarians in lower-resourced or non-English-speaking contexts. Future studies could adopt longitudinal designs and more balanced geographical representation to measure changes in AI literacy over time, incorporate direct assessments of AI competencies, and explore institutional and policy-level factors influencing AI adoption in school libraries.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable foundation for research, policy, and practice—highlighting the urgent need to equip school librarians with the tools, knowledge, and confidence required to lead AI literacy efforts in their communities. Beyond the field of librarianship, this study also contributes to AI literacy scholarship in education more broadly by offering a transferable analytical and developmental model applicable to other professional groups. The multi-domain approach—linking cognitive, behavioral, affective, and ethical dimensions of AI competence—can inform research for teachers, instructional technologists, and curriculum leaders seeking to build AI-ready learning environments. In this sense, the study extends the conversation from “AI literacy for librarians” to a scalable framework for cultivating AI leadership across educational professions, reinforcing the interdisciplinary and global relevance of its findings.

Table 6.

AI Leadership Framework Scope and Sequence. (Hossain, 2025b; adapted with permission).

Table 6.

AI Leadership Framework Scope and Sequence. (Hossain, 2025b; adapted with permission).

Conclusion

This study provides timely and critical insights into the global landscape of school librarians’ AI literacy and professional engagement with AI technologies. Drawing on the perspectives of 319 school librarians from over 50 countries, the findings highlight both the strengths and areas for growth in the profession and preparedness to navigate the evolving demands of AI in K–12 education. Although many respondents demonstrated moderate familiarity and literacy, their pedagogical integration of AI and instructional confidence remain inconsistent—highlighting the need for more structured, accessible, and context-specific professional support.

Without coordinated action among LIS schools, professional associations, and K-12 systems, AI literacy will remain uneven, further entrenching digital divides. A unified advocacy effort—calling for mandatory AI competency standards, securing dedicated professional learning funds, and forging policy partnerships—can underpin the mandates and resources school librarians need to guide students crtically, ethically, and innovatively into an AI-augmented learning ecosystem. Ultimately, the AI Leadership Framework provides a developmental pathway for realizing this vision—supporting school librarians in evolving from users to ethical leaders of AI literacy. The framework further supports the need to foster ethical efficacy—a critical dimension extending Bandura’s self-efficacy theory—capturing the confidence required to apply AI responsibly, which is essential given widespread concern over student misuse. By adopting this staged approach, professional learning can move beyond tool introduction towards cultivating the higher-order competencies required for transformational AI leadership.

References

- Adewojo, A.A. , Amzat, O. B. and Abiola, H.S. "AI-powered libraries: enhancing user experience and efficiency in Nigerian knowledge repositories", Library Hi Tech News 2025, 42, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All European Academies (ALLEA). (2023). The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. https://allea.org/code-of-conduct/.

- American Library Association. (2019). Artificial Intelligence. ala.org. https://www.ala.org/future/trends/artificialintelligence.

- Bauld, A. (2023, August 21). Librarians Can Play a Key Role Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Schools. School Library Journal. https://www.slj.com/story/Librarians-Can-Play-a-Key-Role-Implementing-Artificial-Intelligence-in-Schools.

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepchirchir, S. (2024). Integrating Artificial Intelligence Literacy in Library and Information Science Training in Kenyan Academic Institutions. Karatina University Institutional Repository. https://karuspace.karu.ac.ke/handle/20.500.12092/3201.

- Cox, A. (2023). Developing a library strategic response to Artificial Intelligence. IFLA. https://www.ifla.org/g/ai/developing-a-library-strategic-response-to-artificial-intelligenc.

- Creswell, J. W. , & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications. https://www.ucg.ac.me/skladiste/blog_609332/objava_105202/fajlovi/Creswell.pdf.

- Department of Education. (2024). Australian Framework for Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Schools. Department of Education, Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/schooling/resources/australian-framework-generative-artificial-intelligence-ai-schools.

- European Commission. (2024, April 23). AI Act. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai.

- LaFlamme, K. A. Scaffolding AI literacy: An instructional model for academic librarianship. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 2025, 51, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, L. , Mulligan, A., & Mensell, N. (2024). Insights: librarian attitudes toward AI. Elsevier. https://elsevier.widen.net/s/2jcbgwxsnn/librarian_key_findings_attiutudes_to_ai_report_2024.

- Gültekin, V. , & Kavak, A. An assessment of artificial intelligence anxieties of academic librarians in Türkiye. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 2025, 51, 103058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, F. , & Breazeal, C. Establishing AI Literacy before Adopting AI. The Science Teacher 2024, 91, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, M. , Bewersdorff, A., & Nerdel, C. What do university students know about Artificial Intelligence? Development and validation of an AI literacy test. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023, 5, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z. Connecting policy to practice: How do literature, standards and guidelines inform our understanding of the role of school library professionals in cultivating an academic integrity culture? Synergy 200, 18. Available online: http://slav.vic.edu.au/index.php/Synergy/article/view/373.

- Hossain, Z. , Çelik, Ö., & Hertel, C. Academic integrity and copyright literacy policy and instruction in K-12 schools: a global study from the perspective of school library professionals. International Journal for Educational Integrity 2024, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z. School librarians developing AI literacy for an AI-driven future: leveraging the AI Citizenship Framework with scope and sequence. Library Hi Tech News 2025, 42, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z. AI Leadership Framework: Advancing Australian school library professionals’ AI literacy and leadership competence. Connection 2025, 132, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.H. Exploring the implementation of artificial intelligence applications among academic libraries in Taiwan. Library Hi Tech 2024, 42, 885–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, E. Navigating tomorrow’s classroom. Journal of Information Literacy 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of School Librarianship. (2025). Media & Information Literacy SIG. Iasl-Online.org. https://iasl-online.org/about/leadership/info_lit_sig.html.

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). (2020). IFLA statement on libraries and artificial intelligence. IFLA.org (IFLA FAIFE Committee on Freedom of Access to Information and Freedom of Expression). https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/1646.

- Kalbande, D. , Suradkar, P., Chavan, S., Verma, M.K. & Yuvaraj, M. Artificial Intelligence integration in academic libraries: perspectives of LIS professionals in India. The Serials Librarian 2024, 85, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z. I. , Hossain, Z., Biswas, Md. S., & Islam, Md. E. Mapping AI Literacy Among Library Professionals: A Cross-Regional Study of South Asia and the Middle East. Journal of Web Librarianship. [CrossRef]

- Khazanchi, P. , & Khazanchi, R. (2025). Role of Stakeholders in Improving AI Competencies in K-12 Classrooms. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 736–742). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/225589/.

- Lee, V. V. , van der Lubbe, S. C., Goh, L. H., & Valderas, J. M. Harnessing ChatGPT for thematic analysis: Are we ready? Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e54974. [Google Scholar]

- Limna, P. , Jakwatanatham, S., Siripipattanakul, S., Kaewpuang, P., & Sriboonruang, P. A review of artificial intelligence (AI) in education during the digital era. Advance Knowledge for Executives 2022, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R. , Cukurova, M., Kent, C., & du Boulay, B. Empowering educators to be AI-ready. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2022, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máté, D. , Kiss, J. T., & Csernoch, M. Cognitive biases in user experience and spreadsheet programming. Education and Information Technologies 2025, 30, 14821–14851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, A. (2025, May 5). UAE Makes AI Classes Mandatory from Kindergarten—The World Needs to Follow. Unite.AI. Available online: Unite.AI. https://www.unite.ai/uae-makes-ai-classes-mandatory-from-kindergarten-the-world-needs-to-follow/.

- McKim, K. (2025). From shelf to spreadsheet: How I built a book room inventory with ChatGPT - and what it taught me about Centaur Librarianship, Linkedin.com. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/from-shelf-spreadsheet-how-i-built-book-room-inventory-kathleen-mckim-e1ifc/?trackingId=Cal%2BkgNVSHmKaaKJfMueog%3D%3D.

- Merga, M. K. (2022). School libraries supporting literacy and wellbeing. Available online: https://www.facetpublishing.co.uk/resources/pdfs/chapters/9781783305841.pdf.

- Milberg, T. (2024, April 28). The future of learning: AI is revolutionizing education 4.0, World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/04/future-learning-ai-revolutionizing-education-4-0/.

- Mills, K. , Ruiz, P., Lee, K. W., Coenraad, M., Fusco, J., Roschelle, J., & Weisgrau, J. (2024). AI Literacy: A Framework to Understand, Evaluate, and Use Emerging Technology. Digital Promise. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. , Smith, T., & Thomas, L. Thematic Analysis and Artificial Intelligence: A Step-by-Step Process for Using ChatGPT in Thematic Analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northeastern University & GALLUP. (2019). <i>Facing the future: U.S., U.K. Northeastern University & GALLUP. (2019). Facing the future: U.S., U.K. and Canadian citizens call for a unified skills strategy for the AI age. 2020. Available online: https://uwm.edu/csi/wp-content/uploads/sites/450/2020/10/Facing_the_Future_US_UK_and_Canadian_citizens_call_for_a_unified_skills_strategy_for_the_AI_age.pdf.

- OECD.AI. (2021). National AI policies & strategies. OECD.AI. https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/overview.

- OECD. (2025). PISA 2029 Media and Artificial Intelligence Literacy, OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/about/projects/pisa-2029-media-and-artificial-intelligence-literacy.html.

- Oddone, K. , Garrison, K., & Gagen-Spriggs, K. Navigating generative AI: The teacher librarian's role in cultivating ethical and critical practices. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association 2024, 73, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seales, L. leashea. (2025). Leveraging AI in School Libraries: From Basics to Best Practices, ala.org. https://alastore.ala.org/AIschlib.

- Softlink Education. (2024, April 24). Australian libraries share: the impact of AI on school libraries, Softlinkint.com. https://www.softlinkint.com/blog/australian-school-libraries-share-the-impact-of-ai-on-school-libraries/.

- Stebbins, R.A. (2001). Exploratory research in the social sciences. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L. (2025). Exploratory Research: Definition, How To Conduct & Examples, ATLAS.ti. https://atlasti.com/research-hub/exploratory-research.

- Su, J. , Ng, D. T. K., & Chu, S. K. W. Artificial intelligence (AI) literacy in early childhood education: The challenges and opportunities. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2022). K-12 AI curricula: a mapping of government-endorsed AI curricula, UNESDOC Digital Library. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380602.

- UNESCO. (2023a). Education in the age of artificial intelligence. Available online: https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/education-age-artificial-intelligence.

- UNESCO. (2023b). International forum on AI and education: steering AI to empower teachers and transform teaching. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386162/PDF/386162eng.pdf.multi.

- Voulgari, I. , Stouraitis, E., Camilleri, V. and Karpouzis, K. (2022). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Education and Literacy: Teacher Training for Primary and Secondary Education Teachers. In: Handbook of Research on Integrating ICTs in STEAM Education, IGI Global, 1-21. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-education-and-literacy/304839.

- Williams, R. (2024). Impact. AI: Democratizing AI through K-12 Artificial Intelligence Education, (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)). https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/153676.

- Wong, E. K. C. , & Chiu, D. K. W. AI literacy instruction program in international school libraries: A qualitative study under the lens of the Big Six Information Literacy model. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 2025, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. E. , Koz, O., & Moore, J. A. The Evolving Roles of School Librarians during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Phenomenological Study. School Library Research 2024, 27. Available online: https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/wright-et-al.pdf.

- Yi, K. , Turner, R. H., Syn, S. Y., Williams, M., Hardin, A., & Long, T. M. (2024). A Feasibility Study of AI-Generated Resources for K-12 Information Literacy. In Proceedings of the Association for Library and Information Science Education Annual Conference. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.alise.2024.1757. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).