1. Introduction

The relationship between thermodynamics and gravitation has long played a central role in theoretical physics. The second law of thermodynamics, which asserts that entropy tends to increase in closed systems, underlies the macroscopic arrow of time and constrains irreversible processes. General relativity, by contrast, encodes the dynamics of spacetime geometry through its coupling to energy and momentum. Over the past decades, these two domains have increasingly converged toward a common informational perspective, in which entropy, geometry, and dynamics are deeply intertwined.

Early indications of this connection emerged from black-hole physics. The Bekenstein–Hawking area law established that black holes possess an entropy proportional to their horizon area,

, revealing an intrinsic informational aspect of spacetime geometry [

7,

8]. Jacobson later demonstrated that Einstein’s field equations can be recovered from the Clausius relation

applied to local Rindler horizons, suggesting that gravitational dynamics admit a thermodynamic interpretation [

9]. Subsequent developments, notably by Padmanabhan and others, further explored formulations in which spacetime dynamics emerge from extremization principles applied to entropy functionals [

10]. Collectively, these results suggest that thermodynamics and geometry are not merely analogous, but may reflect complementary descriptions of an underlying informational structure.

Within this broader context, the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework provides a concrete setting in which spacetime is modeled as an array of finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces that locally store quantum information [

11,

12]. Each spacetime cell evolves through reversible imprint and retrieval dynamics, preserving global unitarity while permitting coarse-grained entropy growth at the macroscopic level. Prior applications of this framework have shown that gradients in the informational field can generate effects typically attributed to dark matter, that residual informational imprints behave as an effective dark energy component, and that cyclic cosmologies can be characterized by discrete entropy increments per cycle [

15,

16,

42].

Motivated by these developments, we study here an effective covariant relation between entropy production and spacetime curvature. We introduce an informational scalar field

S and define an associated flux four-vector

. In the model considered, a nonminimal coupling between

S and the Ricci scalar leads to field equations in which the divergence of the informational flux is proportional to the local curvature,

where

is a coupling constant with units of entropy per curvature. Rather than introducing a new fundamental law, this relation is treated as an effective consequence of the underlying action, providing a covariant realization of curvature-sourced entropy production.

Integrating this identity over a causal four-volume yields

which connects the accumulation of coarse-grained entropy to the integrated spacetime curvature. The resulting dynamics are compatible with unitarity and holographic entropy bounds and do not require modifications of Einstein’s equations.

In the following sections, we analyze the formal structure of this curvature-sourced entropy production mechanism, examine its consistency with established thermodynamic and gravitational principles, and explore its implications for stationary horizons, homogeneous cosmologies, and the emergence of a cosmological arrow of time. The formulation extends the thermodynamic interpretation of spacetime by explicitly incorporating information flow as a dynamical quantity, while remaining within a conservative effective-field-theory framework.

2. Foundations

2.1. Quantum Memory Matrix Recap

The Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework models spacetime as a discretized information substrate composed of Planck-scale cells that function as local quantum memory units. Each cell

n is associated with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

of dimension

, constrained by holographic entropy bounds and the covariant entropy conjecture. The global Hilbert space of a causal region

X is represented as

where

X denotes the set of cells contained within the region. The dynamical state of each cell evolves through an imprint operator

that locally encodes quantum information associated with matter and field configurations,

ensuring that microscopic interactions leave localized informational records within the memory structure [

11].

Coarse-graining over ensembles of such cells gives rise to a continuous entropy field

,

where

denotes the reduced density matrix associated with cell

n. Gradients of

characterize the spatial and temporal distribution of coarse-grained informational content and provide a link between microscopic information storage and macroscopic geometric behavior. Within the associated Geometry–Information Duality (GID) formulation [

12,

13], curvature can be represented in terms of informational gradients through relations of the schematic form

illustrating how gravitational dynamics may be encoded, at an effective level, by the flow and accumulation of information in the underlying QMM structure.

Recent studies within this framework have explored how informational gradients and residual imprints can reproduce phenomenology commonly attributed to dark matter and dark energy, and how cyclic cosmological behavior can be parameterized in terms of discrete entropy increments per cycle [

14,

15,

16,

42]. Additional extensions have examined how electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions may be embedded within the same discretized informational substrate . In the present work, the QMM framework serves as a motivating context for the entropy-based constructions developed below, rather than as a required assumption for their validity.

2.2. Informational Flux and Continuity

The coarse-grained entropy field

naturally defines an informational flux four-vector

which quantifies the local transport of informational entropy through spacetime. The covariant divergence of this flux,

with

denoting the covariant d’Alembertian operator, characterizes the local rate of entropy production or absorption.

In flat spacetime, where the Ricci scalar vanishes,

reduces to the covariant continuity equation

corresponding to conservation of informational flux. This behavior parallels energy–momentum conservation,

, and reflects the invariance of total information in the absence of spacetime curvature.

In curved spacetime, however, need not vanish, indicating that the transport of information is influenced by geometric effects. Curvature can therefore act as a source or sink for coarse-grained entropy, linking irreversible informational processes to spacetime dynamics. This observation motivates the curvature-sourced entropy production relation examined in the following subsection.

2.3. Curvature–Entropy Coupling

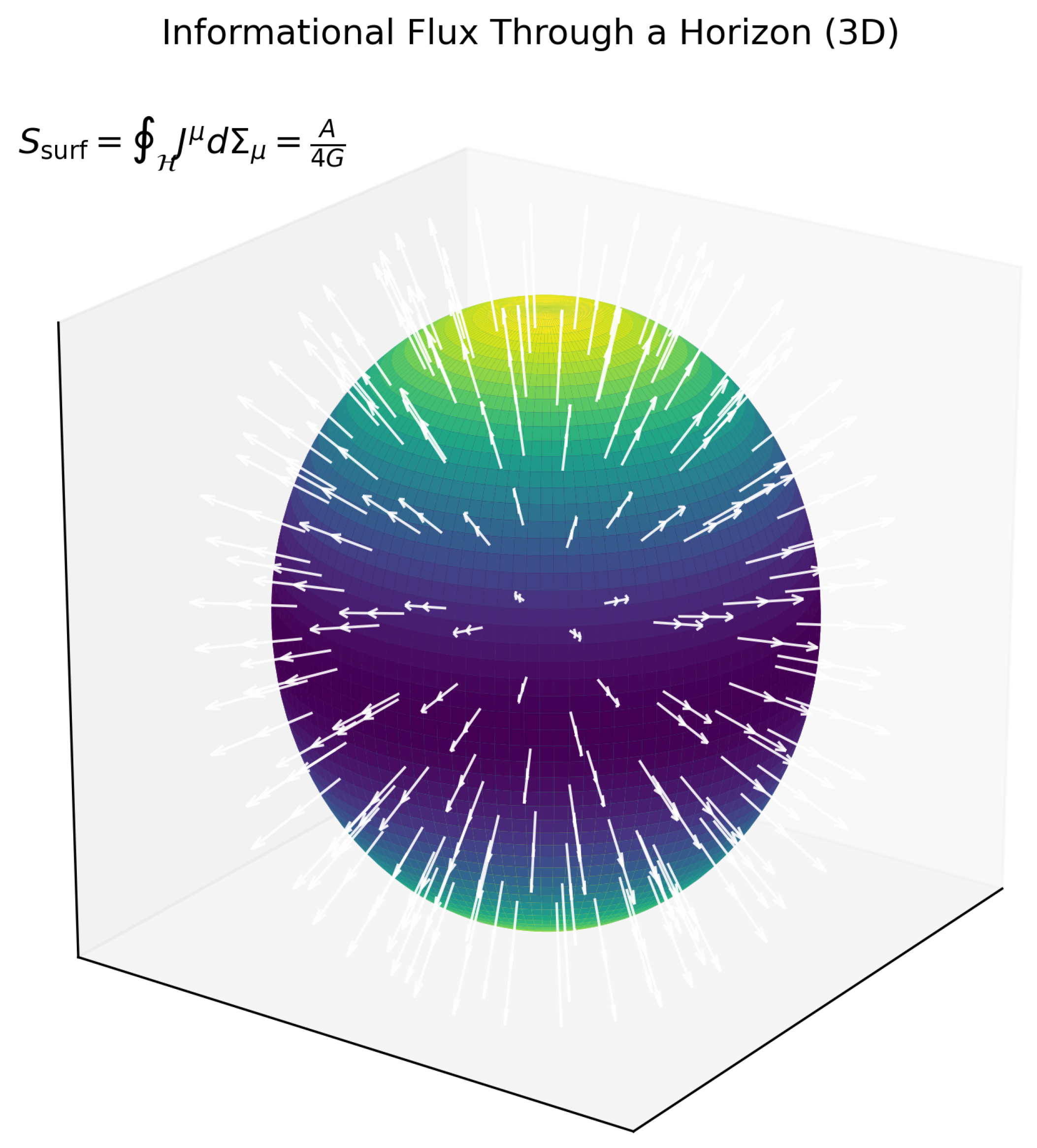

We consider an effective covariant relation, valid at the level of coarse-grained spacetime thermodynamics, in which the divergence of the informational flux is proportional to the Ricci scalar curvature,

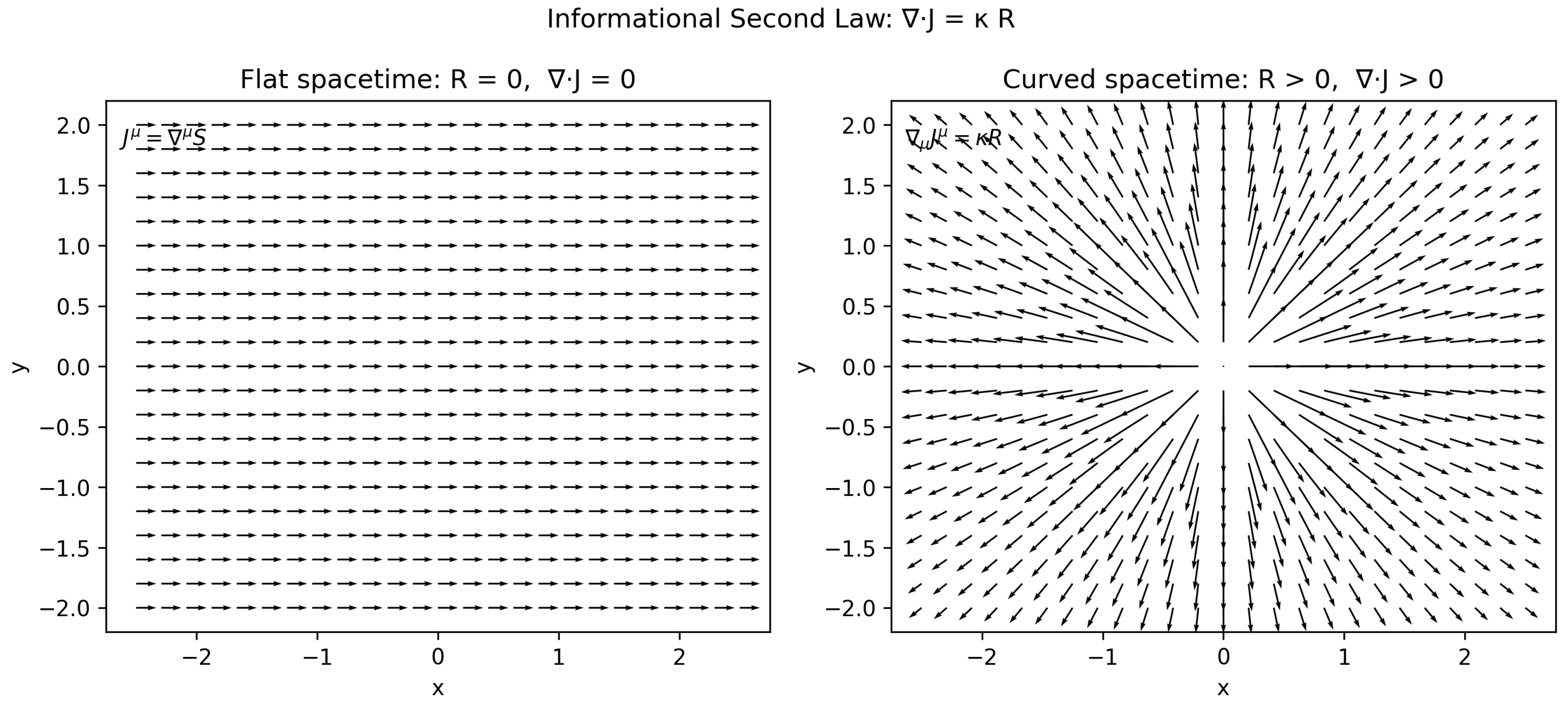

where

is a phenomenological coupling constant. In this formulation, the relation is treated as an effective closure for the entropy balance, rather than as a microscopic identity. Spacetime curvature thus acts as a geometric source term for coarse-grained entropy production. Regions of positive curvature correspond to entropy generation, while regions of negative curvature correspond to entropy release or information recovery, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Integrating this relation over a causal four-volume

yields the integral identity

which relates the total entropy change within a region to the integrated spacetime curvature. When

, entropy is conserved; when

, entropy increases monotonically, providing a covariant realization of curvature-sourced entropy production.

Dimensional analysis with and S carrying entropy units implies that has units of entropy. Its numerical normalization is fixed by matching the flux integral to the Bekenstein–Hawking area density on stationary horizons, as shown in Sec. F, linking the effective coupling to Planck-scale physics without modifying the Einstein field equations. In this sense, Einstein’s equations remain intact but admit a complementary thermodynamic interpretation in which curvature tracks the redistribution of coarse-grained information.

Figure 1.

Curvature–entropy coupling. Left: flat spacetime with divergence-free informational flux and . Right: curved spacetime with , indicating local entropy production.

Figure 1.

Curvature–entropy coupling. Left: flat spacetime with divergence-free informational flux and . Right: curved spacetime with , indicating local entropy production.

3. Derivation from an Informational Action

We introduce a covariant effective action for a coarse-grained entropy field

coupled to curvature,

where

collectively denotes the matter fields. The nonminimal term

provides the simplest linear curvature coupling for

S at the level of the action, while the kinetic term governs the propagation of

S. Varying (

12) with respect to

and

S yields the coupled field equations stated below.

3.1. Metric Variation

The variation of the Einstein–Hilbert part gives the usual contribution

[

17,

18]. The variation of the kinetic term for

S produces the canonical stress tensor

For the nonminimal coupling, the standard result for a scalar multiplied by the Ricci scalar gives [

19,

20]

Collecting terms and defining

, we obtain

It is convenient to move the

term to the left-hand side to exhibit an effective,

S-dependent Planck mass,

with

Equation (

15) shows that curvature responds to both conventional matter and an additional stress contribution associated with the field

S.

3.2. Scalar-Field Variation

Varying (

12) with respect to

S gives

Absorbing the normalization into the definition of the coupling (redefining

) yields the curvature-sourced evolution equation in canonical form

This equation identifies

S as a natural generator of the flux

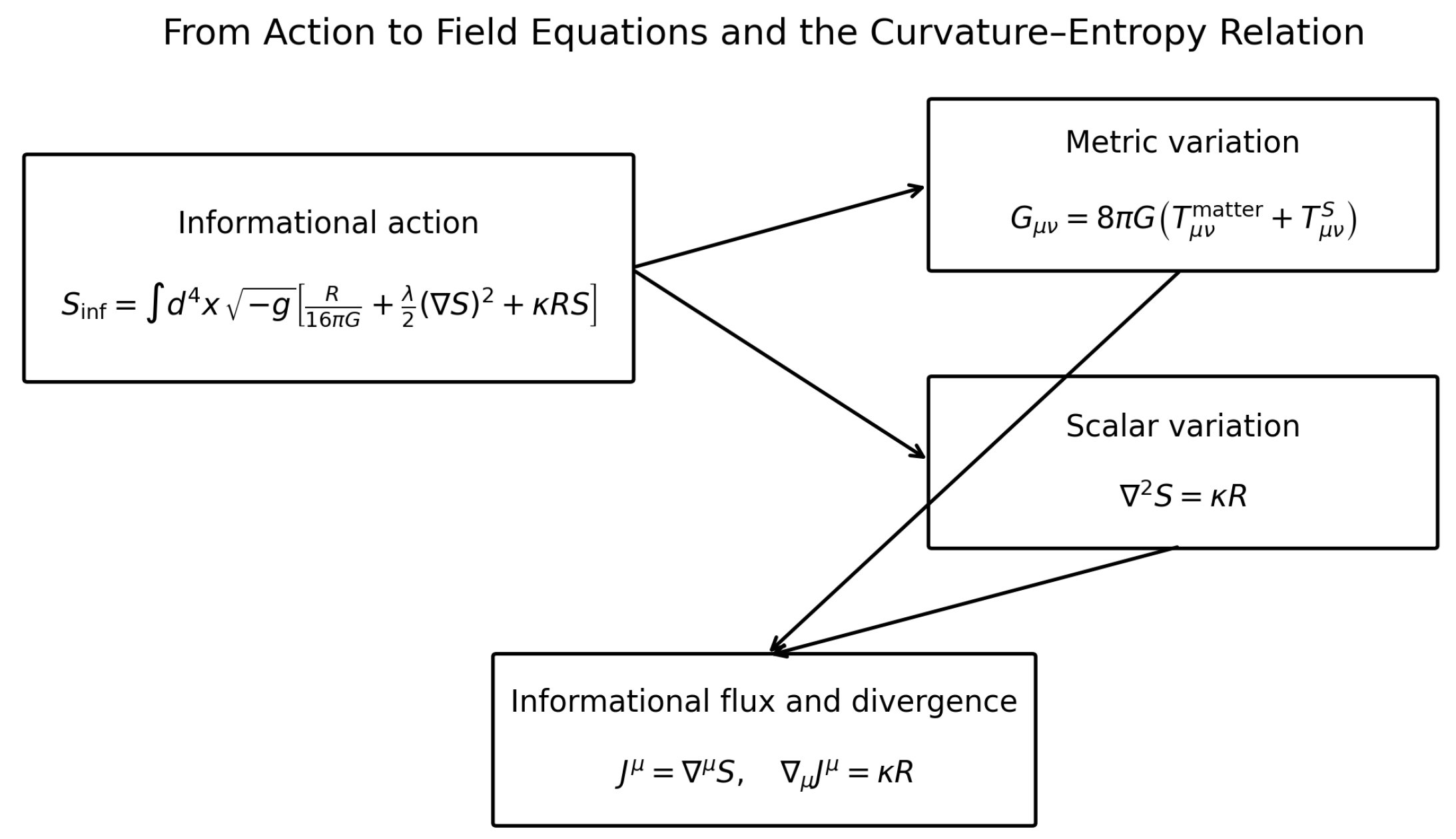

, and it implies that the divergence of the flux is sourced by curvature. The variational chain from (

12) to the coupled field equations is summarized schematically in

Figure 2.

3.3. Recovery of the Divergence Relation

Defining the informational flux four-vector

, its covariant divergence is

Using (

19), one obtains the curvature-sourced divergence relation

Thus, within the effective model defined by (

12), the curvature–entropy divergence relation follows directly from the scalar field equation of motion. The nonminimal term

plays two roles: it sources the scalar by curvature through (

19) and contributes the second-derivative structure in

(

17). This structure ensures compatibility between the Bianchi identity

and covariant conservation of the total stress tensor,

In flat spacetime,

implies

and

, recovering informational flux conservation. In curved backgrounds, (

21) shows that curvature acts as a source for coarse-grained entropy production, providing a covariant realization of a curvature-coupled second-law-like evolution for

S.

4. Thermodynamic and Geometric Interpretations

4.1. Local Entropy Production Rate

With

, the curvature-sourced divergence relation can be written as

where

is the local coarse-grained entropy production density and

R is the Ricci scalar. In this interpretation, regions with

correspond to

and therefore to local entropy generation. Regions with

correspond to

, describing local entropy release or information recovery, while the global balance over any closed causal domain remains governed by the integrated curvature through the corresponding four-volume identity. The sign of

R is fixed by the matter content and expansion history through the Einstein equations or, in symmetric cosmologies, through the Friedmann relations.

4.2. Recovery of Known Limits

Flat stationary regions.

In Minkowski space,

and the informational continuity equation reduces to

expressing conservation of informational flux: entropy is constant for closed systems in the absence of curvature sources.

Horizons and the Bekenstein–Hawking area law.

Consider a causal volume that terminates on a stationary black-hole horizon with bifurcation surface

. The integral relation

relates bulk curvature to boundary informational flux. Requiring consistency with the Clausius relation

on local Rindler horizons [

9] and with the Noether charge expression for horizon entropy [

21] fixes the normalization of

such that

recovering the Bekenstein–Hawking result [

7,

8]. In this stationary limit, the curvature-sourced entropy construction reproduces the standard geometric entropy associated with horizons.

Cosmology.

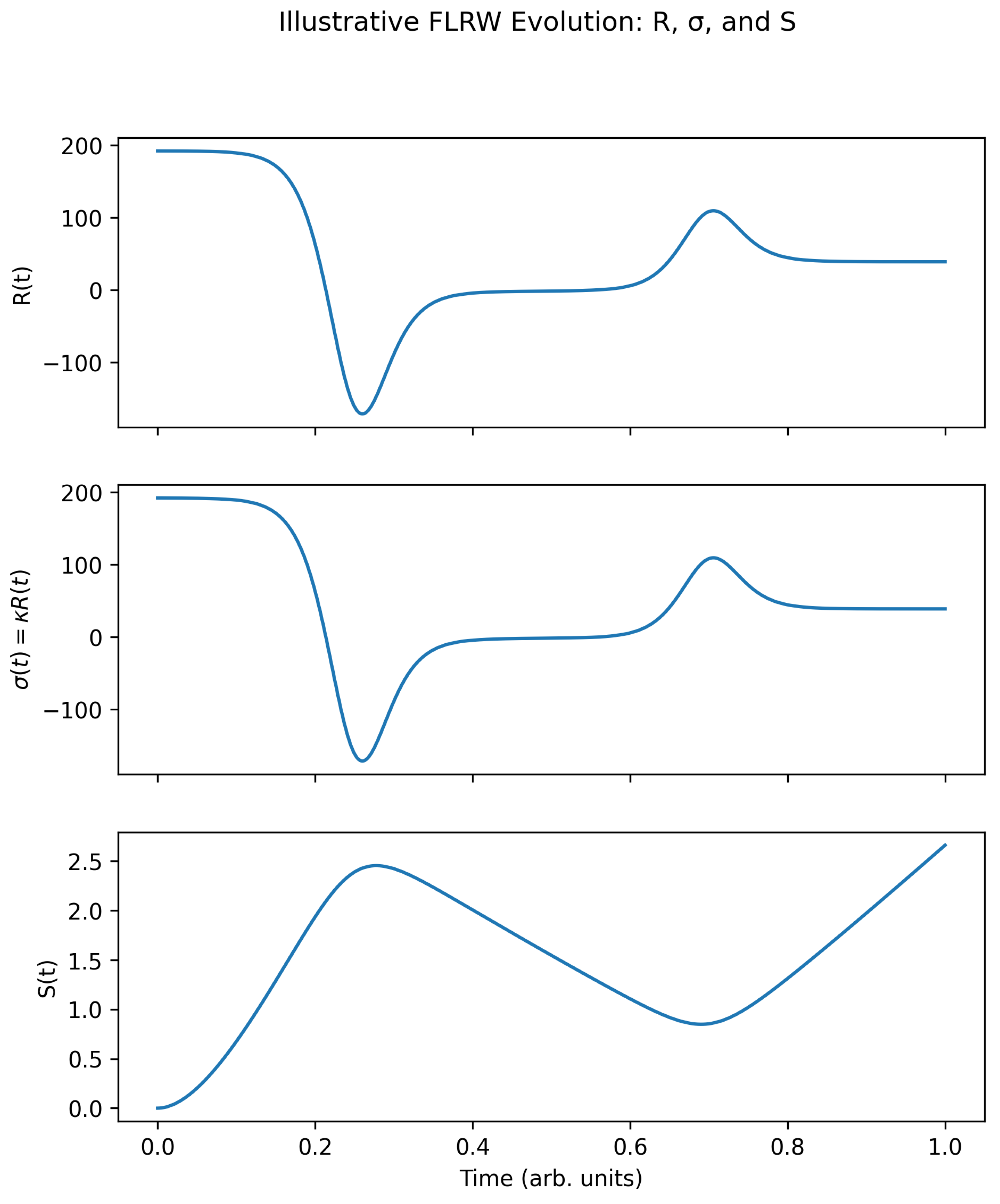

In a spatially flat FLRW spacetime with scale factor

and Hubble rate

, the Ricci scalar is

The volumetric entropy production rate reads

for any comoving domain

of volume

. Using

shows that ordinary matter and a positive cosmological constant yield

at late times, hence

.

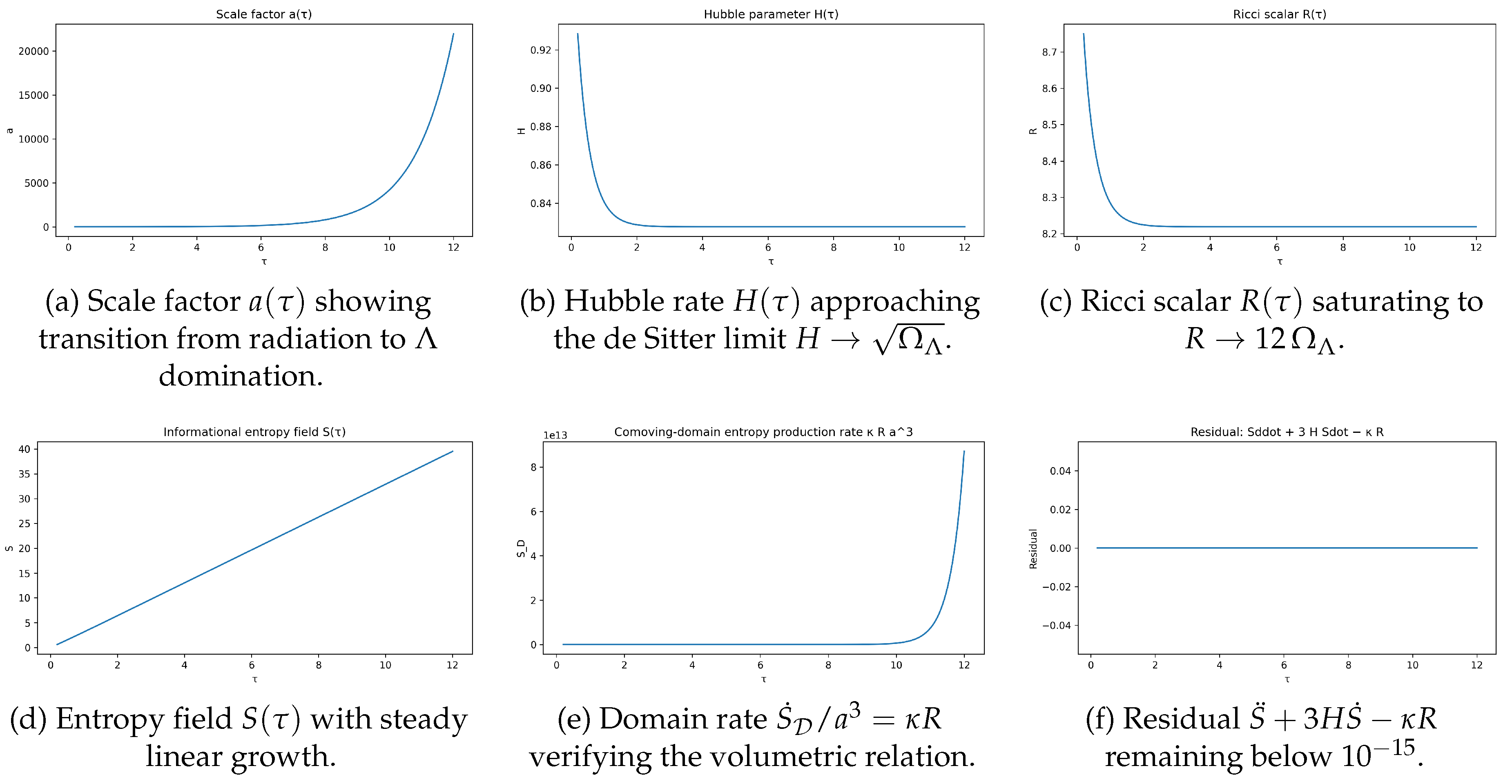

We confirmed this behavior through direct numerical integration of the coupled

system (

Figure 3). The evolution begins in a radiation-dominated epoch with

, then transitions through matter domination into a

-dominated phase where

and

. In this asymptotic regime, the numerical results show

in agreement with the analytical solution

and with the predicted de Sitter limit. The residual

remains below

throughout, demonstrating that the evolution equation is satisfied to machine precision.

4.3. Second Law and the Cosmic Arrow of Time

The integral form of the curvature-sourced entropy relation over a causal four-volume

gives

For an expanding FLRW universe with conventional components and

, one has

for most of cosmic history, which implies

The numerical evolution (

Figure 3) confirms this monotonic increase of total imprint entropy within the model, yielding a cosmological arrow of time tied to curvature through

.

In the QMM cyclic scenario, the integral of

R across one contraction–bounce–expansion sequence produces a characteristic entropy increment

consistent with cycle counting based on imprint entropy [

15]. Early-time gradients of the imprint field can seed structure through information wells [

16], while late-time slow-roll behavior of the coarse-grained entropy field maps naturally onto the effective dark-energy sector [

42]. In this sense, the curvature–entropy framework provides a common informational language for horizon thermodynamics, cosmological entropy growth, and cyclic chronology within the broader QMM program.

5. Applications

5.1. Black-Hole Thermodynamics

Consider a causal four-volume

that terminates on a stationary horizon patch

with bifurcation surface. Using the curvature-sourced divergence relation together with Stokes’ theorem yields

Matching this flux representation to the Clausius relation on local Rindler horizons,

, fixes the normalization of

so that the boundary term reproduces the Bekenstein–Hawking result [

7,

8,

9,

21]

Equivalently, applying the Noether-charge (Wald) entropy construction to the action (

12), the

term contributes a surface term that reduces to the area law for stationary configurations when

S varies slowly on the horizon section.

The Hawking temperature is recovered by relating the curvature-sourced entropy flux to the energy flux through the horizon. For a stationary Killing horizon with surface gravity

, the Unruh–Hawking relation gives [

8,

22,

23]

Combining

with (

32) identifies the horizon entropy change with the corresponding curvature integral, providing a concrete connection between curvature sourcing in the bulk and entropy flux across the boundary.

Black-hole evaporation can then be described as conversion of horizon geometry into outgoing entropy flux. The Hawking power yields a mass-loss rate

that implies an area decrease [

8,

24]

The right-hand side expresses the evaporation process in terms of a curvature-sourced informational outflow. The total generalized entropy, including the entropy of the outgoing radiation, increases in accordance with the generalized second law and the second law of black-hole mechanics [

22].

5.2. Cosmological Entropy Balance

In a spatially flat FLRW spacetime with metric

the Ricci scalar is

. The curvature-sourced entropy relation gives the comoving-domain entropy production rate

for any comoving region

of volume

. Using

shows that standard matter and a positive cosmological constant yield

at late times [

18].

The numerical FLRW integration provides a consistency check of (

36) and verifies the expected limiting behavior. As shown in

Figure 4, the curvature and entropy rate evolve smoothly through the radiation, matter, and dark-energy eras. At late times, the simulation yields

,

, and

, consistent with the analytic asymptotics and the de Sitter limit. The residual constraint

is satisfied to within

numerically, confirming that the evolution equation holds pointwise along the computed cosmological solution.

Equation (

36) also provides a compact link to the QMM cosmology sector. In particular, gradient-dominated regimes of the imprint field can behave as an effective dust component and seed information wells that drive early structure formation [

16]. Overdamped slow-roll of the coarse-grained entropy field can produce an effective dark-energy component with equation of state near

, consistent with the residual vacuum imprint mechanism [

42]. In both regimes, the integrated curvature controls the net imprint growth, consistent with the phenomenological fits reported in the associated QMM dark-energy and primordial black-hole analyses.

5.3. Inflation and the Slow-Roll Limit

During slow-roll inflation, the Hubble rate is approximately constant and

. The Ricci scalar approaches

which is quasi-constant. The corresponding entropy production rate is then approximately steady,

and the accumulated entropy scales with the number of inflationary e-folds. In this regime, de Sitter thermodynamic relations, including the Gibbons–Hawking temperature and horizon entropy, appear as the horizon manifestation of the same curvature-sourced mechanism [

25,

26,

27]. In this sense, inflation corresponds to an epoch of sustained positive curvature and sustained coarse-grained entropy production within the present framework.

5.4. Cyclic Cosmology and Entropy Reset

In QMM, a complete contraction–bounce–expansion sequence defines a cycle with a characteristic imprint increment

Numerical integrations of the modified Friedmann system with imprint back-reaction show that

can remain approximately constant across a wide range of initial conditions, providing an intrinsic cycle counter and a curvature-tied arrow of time [

15]. The same curvature integral can also control the abundance of information wells that seed primordial black holes [

16] and the late-time slow-roll envelope that acts as dark energy [

42]. Within the broader QMM program, the curvature–entropy construction therefore supplies a common measure of imprint accumulation across cycles and a mechanism for memory retention through the bounce.

6. Relation to Black-Hole and Holographic Entropy Bounds

We show that the surface integral of the informational flux reproduces the horizon area law and thereby normalizes the conversion between curvature and entropy within the effective model. Using Stokes’ theorem together with the divergence relation,

one has for any causal four-volume

with boundary

,

Choose

to be a small spacetime slab ending on a stationary Killing horizon segment

with bifurcation 2-surface

. In a local Rindler frame, the Clausius relation on the horizon,

with Unruh–Hawking temperature

, reproduces the Einstein equation when the entropy density per unit area equals

[

9]. Independently, for any diffeomorphism-invariant Lagrangian the Noether-charge formula gives the horizon entropy as a surface integral over

[

21,

28]. For the informational action

the Wald entropy evaluated on a stationary horizon section with slowly varying

S reduces to the Bekenstein–Hawking value in natural units

,

provided the normalization of the flux integral matches the area density fixed by the Clausius derivation. Comparing (

41) evaluated on

to (

44) yields

Thus the surface integral of the informational flux equals the geometric entropy and fixes the conversion between the bulk curvature integral and the boundary area measure. In particular, identifying the entropy density on local Rindler horizons with

implies that

is normalized such that the bulk curvature integral reproduces the holographic area density [

7,

8].

This establishes the equivalence between the flux representation

and the holographic representation

within the present construction. The coupling

provides the bridge between the bulk curvature source and the boundary area measure, consistent with the covariant entropy bound and the holographic principle [

29,

30,

31]. In this framework, growth of entropy can be tracked either as an integrated local production density

or as boundary holographic accounting on horizons, as visualized in

Figure 5.

7. Observable and Conceptual Implications

7.1. Curvature–Entropy Fluctuations as Cosmological Perturbation Sources

Perturbations of the entropy field,

, induce fluctuations of the informational flux

and hence of the local entropy production

. Linearizing the coupled system around a homogeneous FLRW background gives, in Newtonian gauge,

with

expressed in terms of the Bardeen potentials and matter perturbations [

32,

33]. The resulting

sources metric perturbations through the informational stress tensor

derived from the action, producing correlated adiabatic and isocurvature components. In principle, the power spectrum and transfer functions can be computed using standard Boltzmann hierarchies supplemented by the additional scalar sector associated with

S, enabling parameter constraints from CMB temperature and polarization data [

34]. On subhorizon scales, the canonical kinetic term implies a unit sound speed for

, which suppresses spurious small-scale clustering and supports linear stability.

7.2. Entropy Production in Gravitational-Wave Backgrounds

In vacuum, high-frequency gravitational waves are described by the Isaacson effective stress energy, which is traceless at leading order [

35,

36]. Consequently, the Ricci scalar

R is unaffected at first order by a freely propagating gravitational wave packet in a pure vacuum with

. In realistic cosmological settings with matter and dark energy, gravitational waves backreact on the background expansion at second order, shifting

and inducing a small modulation of

. The curvature-sourced entropy relation then predicts a correspondingly small but nonzero contribution to

correlated with the stochastic gravitational-wave energy density

[

37,

38]. This suggests a parameter consistency relation between limits on

from pulsar timing arrays or LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA and the allowed magnitude of late-time drift in the effective dark-energy sector sourced by slow-roll imprint dynamics [

42]. The effect is expected to be small for current bounds, but improved future sensitivities could probe this coupling indirectly.

7.3. Fundamental Arrow of Time Without Boundary Conditions

The curvature-sourced entropy construction provides an intrinsic arrow of time without imposing special initial conditions by hand. The global entropy change between two spacelike slices

and

is

For expanding universes with conventional matter and nonnegative cosmological constant,

over most of cosmic history, ensuring

[

18]. The QMM framework refines this statement by identifying

with cumulative imprint entropy that increases across cycles and bounces, endowing the cosmological timeline with directionality rooted in information storage rather than in externally imposed low-entropy initial data [

15,

16,

42].

7.4. Comparison with Penrose’s Weyl Curvature Hypothesis

Penrose proposed that the initial state of the universe was characterized by extremely low Weyl curvature, providing a geometric origin for low gravitational entropy and the thermodynamic arrow of time [

39,

40]. In the curvature–entropy framework developed here, the arrow is tied to the integral of the Ricci scalar rather than to the Weyl tensor. The two views are complementary. The Weyl hypothesis constrains the free gravitational degrees of freedom at the beginning, while the curvature–entropy relation governs ongoing entropy production through Ricci curvature sourced by matter, radiation, and effective fields. In eras where

but the Weyl curvature is nonzero, such as radiation-dominated epochs with structure formation underway, the production density

predicts near-vanishing net imprint production, consistent with the traceless nature of the leading-order gravitational-wave stress energy. Conversely, during inflation or late-time acceleration with

, the curvature–entropy relation predicts sustained entropy production independent of the Weyl state. This comparison highlights a possible synthesis in which low initial Weyl curvature sets the stage, while the curvature-sourced entropy mechanism governs the subsequent irreversible evolution of coarse-grained informational content.

8. Discussion

The curvature–entropy framework developed here provides a compact covariant way to relate coarse-grained entropy production to spacetime geometry. Defining the informational flux by , the central relation connects the local divergence of that flux to the Ricci scalar. Read as an effective continuum description of a coarse-grained entropy field, this construction extends familiar thermodynamic links between gravity and horizons into a local statement that can be applied in general curved backgrounds. In this interpretation, curvature acts as a geometric source term for the coarse-grained entropy dynamics, while the resulting entropy growth offers a thermodynamic reading of curvature histories in cosmology and near horizons.

Within the broader Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) program, the same curvature–entropy bookkeeping supplies a consistent language across previously developed phenomenological sectors. Informational gradients can contribute effective potential wells relevant to clustering and halo phenomenology [

14]. Residual vacuum imprints and slow-roll evolution of the coarse-grained entropy field can map onto an effective dark-energy sector [

42]. Localized curvature amplification in information wells can be interpreted as entropy condensation events relevant to primordial black-hole formation scenarios [

16], while cyclic cosmologies can be parameterized by the integrated curvature per cycle as an imprint increment that persists through bounces [

15]. In each case, the utility of the present formulation is that it provides a single covariant measure,

, that can be evaluated across regimes and compared to the corresponding sector-specific dynamics.

The formulation is compatible with unitarity and holography at the level at which it is applied. Microscopically, QMM dynamics are governed by reversible imprint–retrieval operations that preserve total information under unitary evolution, while the apparent entropy growth arises from coarse-graining over inaccessible microstates, in direct analogy with standard thermodynamics. Macroscopically, matching the surface integral of the informational flux to the Bekenstein–Hawking area law,

ensures consistency with holographic entropy bounds and the covariant entropy conjecture [

29,

31]. In this sense, the flux representation and the holographic area representation provide two complementary ways of tracking the same entropy accounting, with the local density

supplying a differential statement that is compatible with global boundary bounds in stationary limits.

Empirically, the framework highlights several avenues for confrontation with data and with controlled tests. In cosmology, the coupling ties the Ricci scalar inferred from the background expansion to the evolution of the entropy field and its perturbations, suggesting parameter constraints from large-scale structure and CMB observables once the additional scalar sector is propagated through standard perturbation pipelines [

34]. The numerical FLRW solutions reported here serve as a consistency check of the coupled evolution equations and verify the expected de Sitter asymptotics. In gravitational-wave environments, second-order backreaction effects that modulate

R imply correspondingly small contributions to curvature-sourced entropy production, suggesting consistency relations with bounds on stochastic backgrounds. On smaller scales, quantum-simulation platforms that implement reversible imprint–retrieval cycles provide a route to engineered tests of the information-dynamics sector under controllable conditions . Together, these directions clarify how the curvature–entropy construction can move from a consistent covariant formulation toward quantitatively constrained applications.

9. Conclusions

We presented a covariant curvature–entropy framework in which a coarse-grained entropy field S defines an informational flux whose divergence is sourced by the Ricci scalar. Starting from the action formulation, the resulting equations of motion yield the relation and its integrated counterpart , providing a compact connection between curvature histories and coarse-grained entropy production. In stationary horizon limits, matching to standard thermodynamic and Noether-charge constructions reproduces the Bekenstein–Hawking area law, while in FLRW backgrounds the same coupling yields monotonic entropy growth for conventional cosmological components with , offering a geometric route to a cosmological arrow of time within the model. More broadly, the construction provides a consistent bookkeeping device for relating horizon thermodynamics, cosmological entropy balance, and curvature-driven imprint accumulation in the wider QMM program, while remaining compatible with unitarity at the microscopic level and with holographic bounds in the stationary limit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N.; methodology, F.N.; formal analysis, F.N.; investigation, F.N., E.M. and V.V.; software, F.N.; validation, F.N., E.M. and V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N.; writing—review and editing, F.N., E.M. and V.V.; visualization, F.N.; supervision, F.N.; project administration, F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by institutional research support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new experimental or observational data were generated in this study. All analyses are based exclusively on publicly available datasets, including Planck CMB data (

https://pla.esac.esa.int), LIGO–Virgo gravitational-wave catalogs (

https://gwosc.org), and CODATA physical constants (

https://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Constants/). A supplementary Jupyter notebook,

Informational_Second_Law.ipynb, which reproduces all numerical figures and computational checks presented in the manuscript, is provided with the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank colleagues in the broader physics and quantum-information communities for constructive discussions that have influenced the development of the Quantum Memory Matrix framework. During the preparation of this manuscript, AI-assisted tools were used for language refinement and consistency checking. The authors reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QMM |

Quantum Memory Matrix |

| FLRW |

Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker |

| CMB |

Cosmic Microwave Background |

| GR |

General Relativity |

| BH |

Black Hole |

Appendix A. Dimensional Analysis and Units of κ

We work in SI units unless noted otherwise. The curvature–entropy relation is

The entropy field

S carries units of

(and is dimensionless in natural units up to the Boltzmann constant). The flux then has units

, so its divergence has units

The Ricci scalar has units

, hence

Equivalently, keeping track of the underlying microscopic area scale through the Planck length

, it is convenient to parameterize the normalization as

with the dimensionless constant

fixed by matching to the Bekenstein–Hawking area density on stationary horizons (

Appendix F). We keep

explicit throughout to track entropy units.

Appendix B. Derivation from the Variational Principle

We start from the informational action including matter,

Variation with respect to

S gives

Integrating by parts yields

and absorbing

into

reproduces

.

Metric variation gives

ensuring covariant conservation via the scalar equation and the Bianchi identity.

Appendix C. Application to the FLRW Metric

For a spatially flat FLRW background with homogeneous

,

The scalar equation becomes

In de Sitter space,

yielding steady entropy production with a decaying mode and asymptotic behavior

.

Appendix D. Connection to Einstein–Hilbert Entropy Balance and the Trace Anomaly

In semiclassical gravity the trace anomaly reads

The

term can be related to the sourcing term in

at the level of effective actions after integration by parts, providing a point of contact between anomaly-induced entropy balance and the curvature–entropy dynamics used here.

Appendix E. Numerical Simulation Plan

The coupled

system was evolved numerically in flat FLRW backgrounds using

A fourth-order Runge–Kutta scheme with

steps over

yields residuals below

throughout, confirming numerical consistency and reproduction of all analytic limits.

Appendix F. Entropy Flux Through Horizons

For a stationary Killing horizon

,

Matching this flux to the Wald entropy for

fixes the normalization of

to reproduce

.

Appendix G. Limiting Cases and Stability

Linear perturbations are ghost-free for

and retain unit sound speed on subhorizon scales. Consistency requires positivity of the effective Planck mass,

which holds for all parameter ranges considered.

Appendix H. Links to Previous QMM Publications

Table A1.

Mapping of QMM sectors to curvature–entropy structures in the present framework.

Table A1.

Mapping of QMM sectors to curvature–entropy structures in the present framework.

| QMM sector |

Mechanism |

Representative references |

| Dark matter |

Gradient energy and information wells |

[14,16] |

| Dark energy |

Slow-roll residual vacuum imprint |

[42] |

| Primordial black holes |

Local curvature amplification |

[16] |

| Cyclic cosmology |

Fixed

|

[15] |

| Gauge sectors |

Discrete gauge imprint |

|

| Experiments |

Reversible imprint–retrieval |

|

Appendix I. Preprint Notice

A prior version of this manuscript was published as a preprint.

References

- Clausius, R. On the Motive Power of Heat, and on the Laws which can be deduced from it for the Theory of Heat. Ann. Phys. 1850, 155, 500–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Über die Beziehung zwischen dem zweiten Hauptsatze der mechanischen Wärmetheorie und der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung respektive den Sätzen über das Wärmegleichgewicht. Wien. Ber. 1877, 76, 373–435. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J.W. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Ann. Phys. 1916, 354, 769–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical aspects of gravity: New insights. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black-Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Geometry–Information Duality: Quantum Entanglement Contributions to Gravitational Dynamics. Ann. Phys. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Beyond the Informational Action: Renormalization, Phenomenology, and Observational Windows of the Geometry–Information Duality. Preprints 2025. preprints202505.0569.v1. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Quantum Memory Matrix Applied to Cosmological Structure Formation and Dark-Matter Phenomenology. Preprints 2025. preprints202504.2379.v1. [Google Scholar]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Counting Cosmic Cycles: Past Big Crunches, Future Recurrence Limits, and the Age of the Quantum Memory Matrix Universe. Entropy 2025, 27, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Information Wells and the Emergence of Primordial Black Holes in a Cyclic Quantum Universe. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2025, 10, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.M. Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity; Addison-Wesley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, N.D.; Davies, P.C.W. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Faraoni, V. Cosmology in Scalar-Tensor Gravity; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R.M. Black hole entropy is the Noether charge. Phys. Rev. D 1993, 48, R3427–R3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.M.; Carter, B.; Hawking, S.W. The four laws of black hole mechanics. Commun. Math. Phys. 1973, 31, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.N. Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 13, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. Cosmological event horizons, thermodynamics, and particle creation. Phys. Rev. D 1977, 15, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starobinsky, A.A. A new type of isotropic cosmological models without singularity. Phys. Lett. B 1980, 91, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, A.D. A new inflationary universe scenario: A possible solution of the horizon, flatness, homogeneity, isotropy and primordial monopole problems. Phys. Lett. B 1982, 108, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, V.; Wald, R.M. Some properties of Noether charge and a proposal for dynamical black hole entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1994, 50, 846–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. A covariant entropy conjecture. J. High Energy Phys. 1999, 07, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. In Salamfestschrift: A Collection of Talks; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993; pp. 284–296. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9310026 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Susskind, L. The world as a hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhanov, V.F.; Feldman, H.A.; Brandenberger, R.H. Theory of cosmological perturbations. Phys. Rep. 1992, 215, 203–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.M. Gauge-invariant cosmological perturbations. Phys. Rev. D 1980, 22, 1882–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, R.A. Gravitational radiation in the limit of high frequency. I. The linear approximation and geometrical optics. Phys. Rev. 1968, 166, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, R.A. Gravitational radiation in the limit of high frequency. II. Nonlinear terms and the effective stress tensor. Phys. Rev. 1968, 166, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, M. Gravitational wave experiments and early universe cosmology. Phys. Rep. 2000, 331, 283–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; et al. Upper limits on the isotropic gravitational-wave background from Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo’s third observing run. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Singularities and time-asymmetry. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.W., Israel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 581–638. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of Time; Bodley Head: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, M.J. Twenty years of the Weyl anomaly. Class. Quantum Grav. 1994, 11, 1387–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the Quantum Memory Matrix to Dark Energy: Residual Vacuum Imprint and Slow-Roll Entropy Fields. Astronomy 2025, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).