Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Wastewater Management Challenges

1.2. WWM: A Multifactorial and Multidisciplinary Perspective

1.3. Semantic Networks

- Definitional Networks. They represent hierarchical relationships ranging from general to specific knowledge. In this work, we define different levels of abstraction to represent the effects of drivers on an objective through cause-effect relationships. For example, the most general relationships between indirect and direct factors and the objective or recipient of the effects are represented by single level of abstraction, where a set of indirect drivers cause effects on the environmental. However, we recognize that complex systems, such as the one addressed in this work, require more specific knowledge to improve the understanding and analysis of the problem under study. Therefore, this more specific knowledge must be represented by its corresponding specific levels.

- Learning Networks, where the system learns new information by updating relationships and nodes based on new data and experiences, thus improving the understanding of the complex system under study.

- Hybrid Networks, where the combination of two or more models allows for more complex and dynamic knowledge representations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Tourism Data: The Most Important Economic Activity in Acapulco

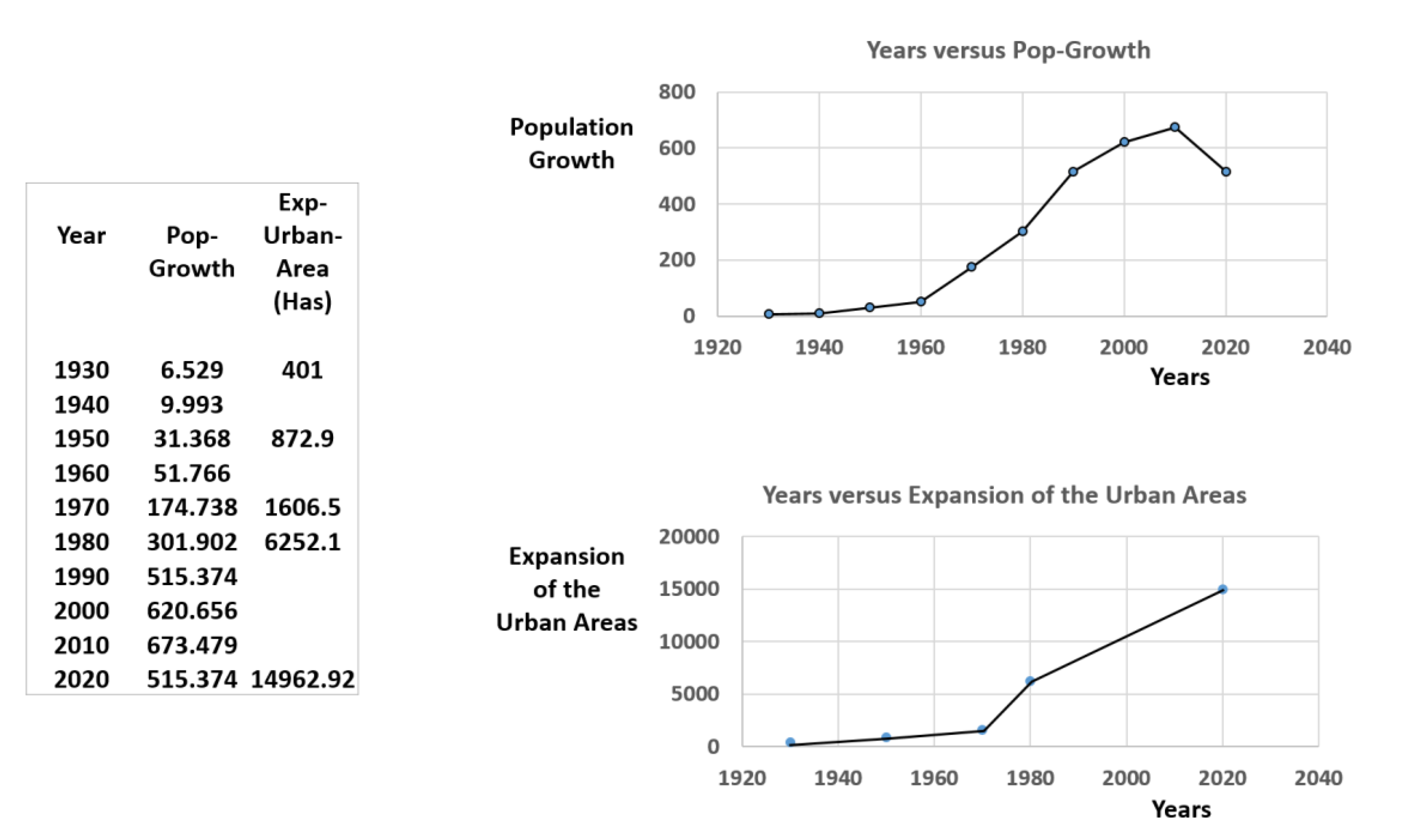

2.1.2. Key Data: Years vs Population Growth & Years vs Expansion of the Urban Areas

2.2. Methods

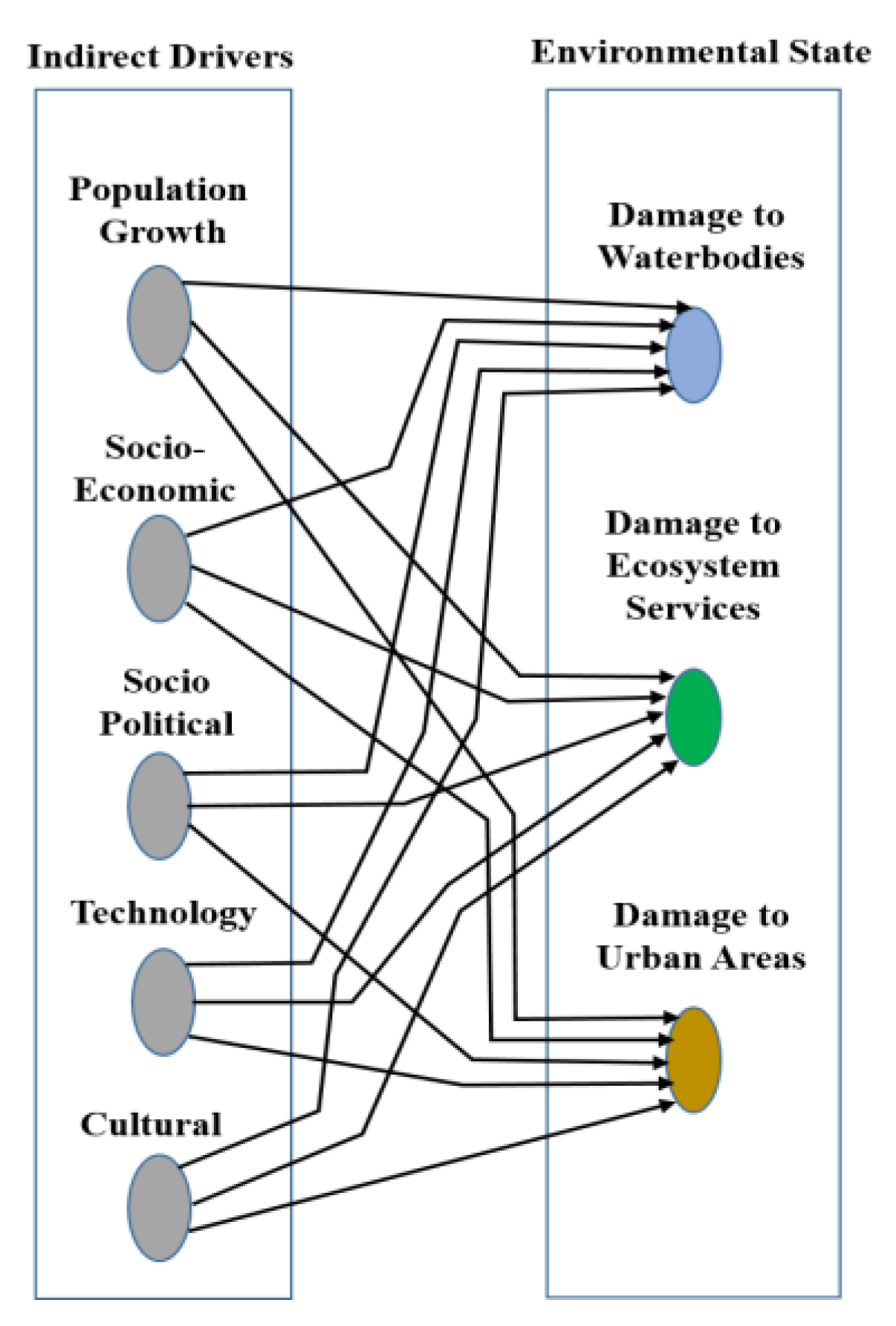

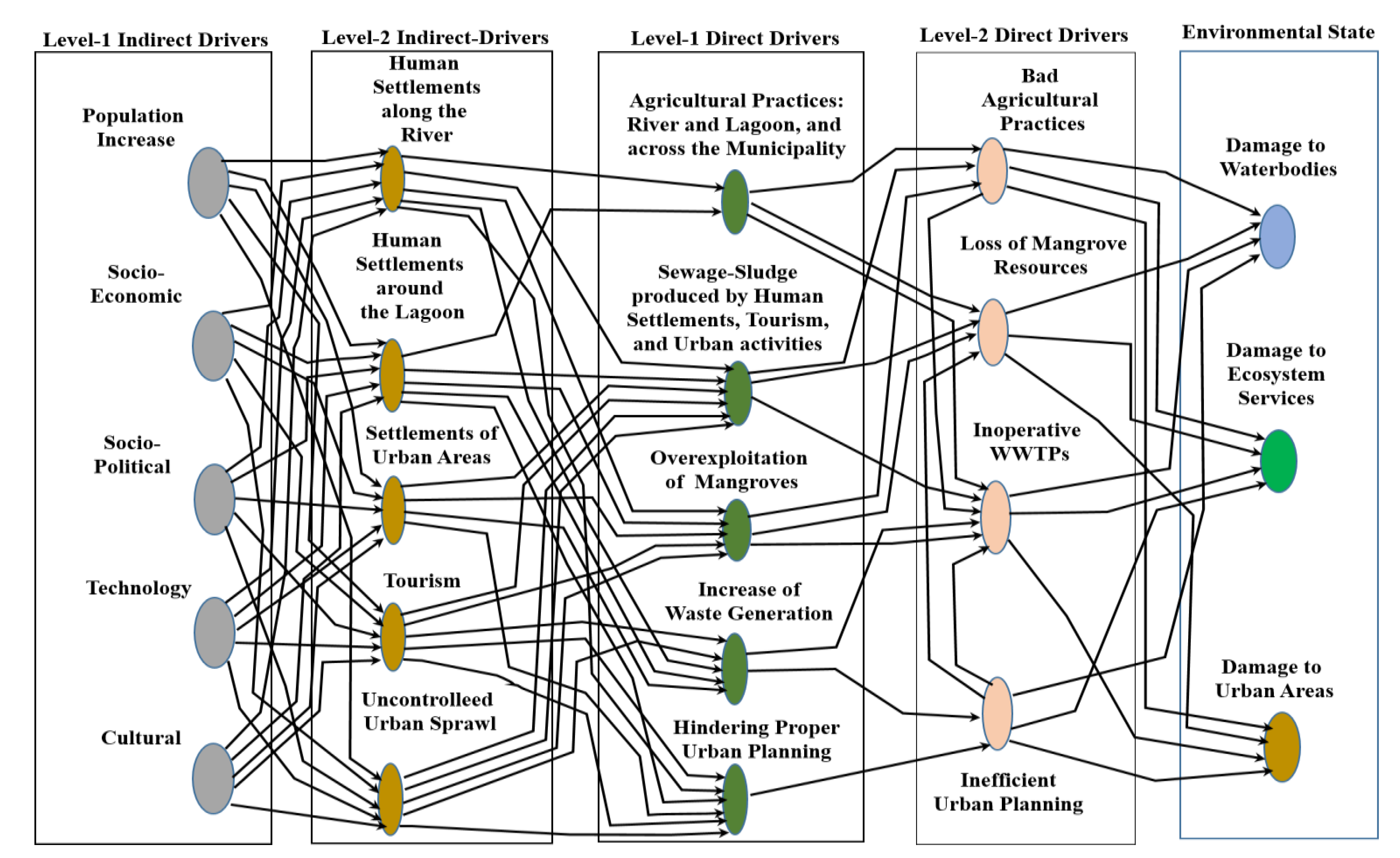

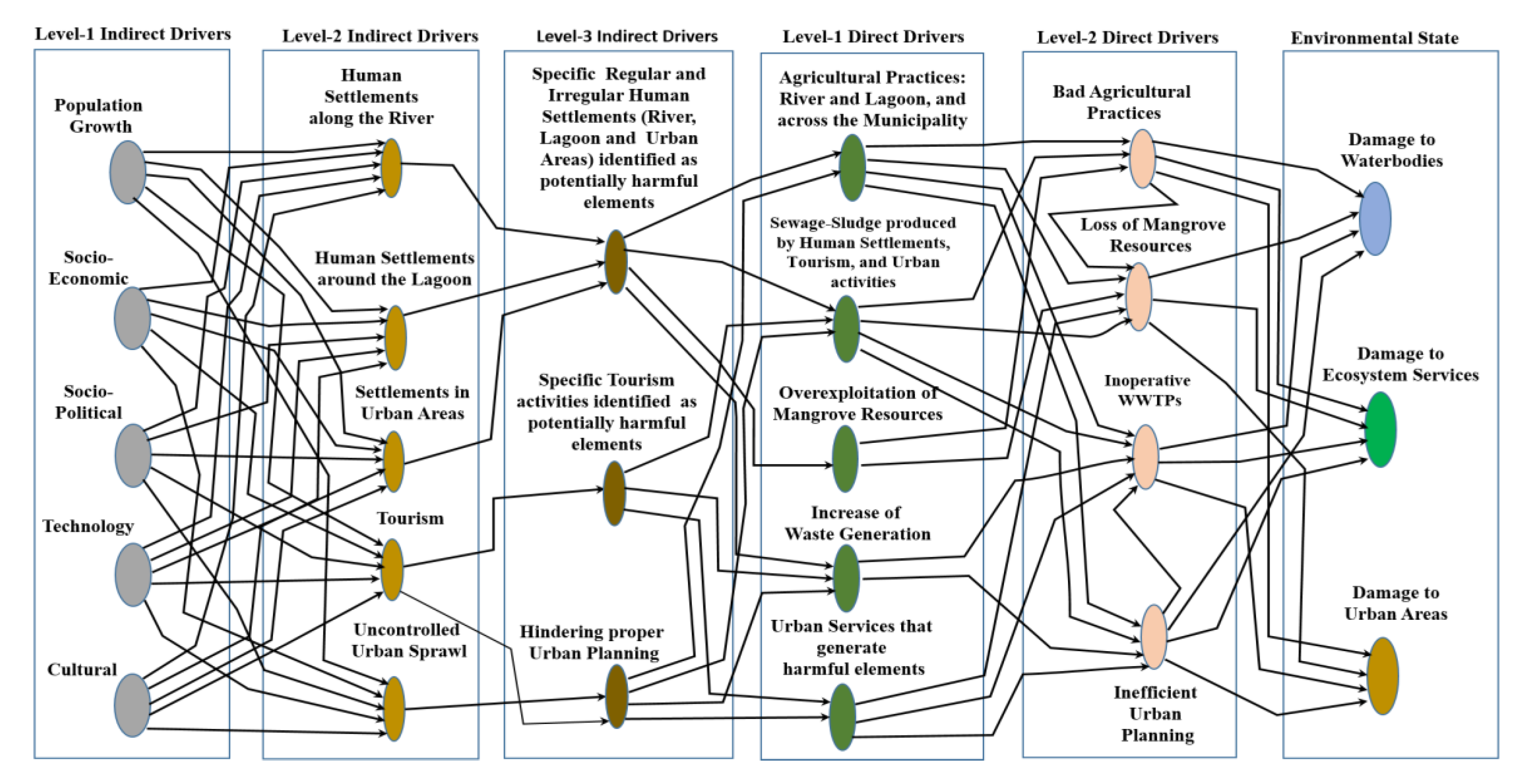

2.2.1. Semantic Networks of Multifactorial Interactions That Impact the Environment

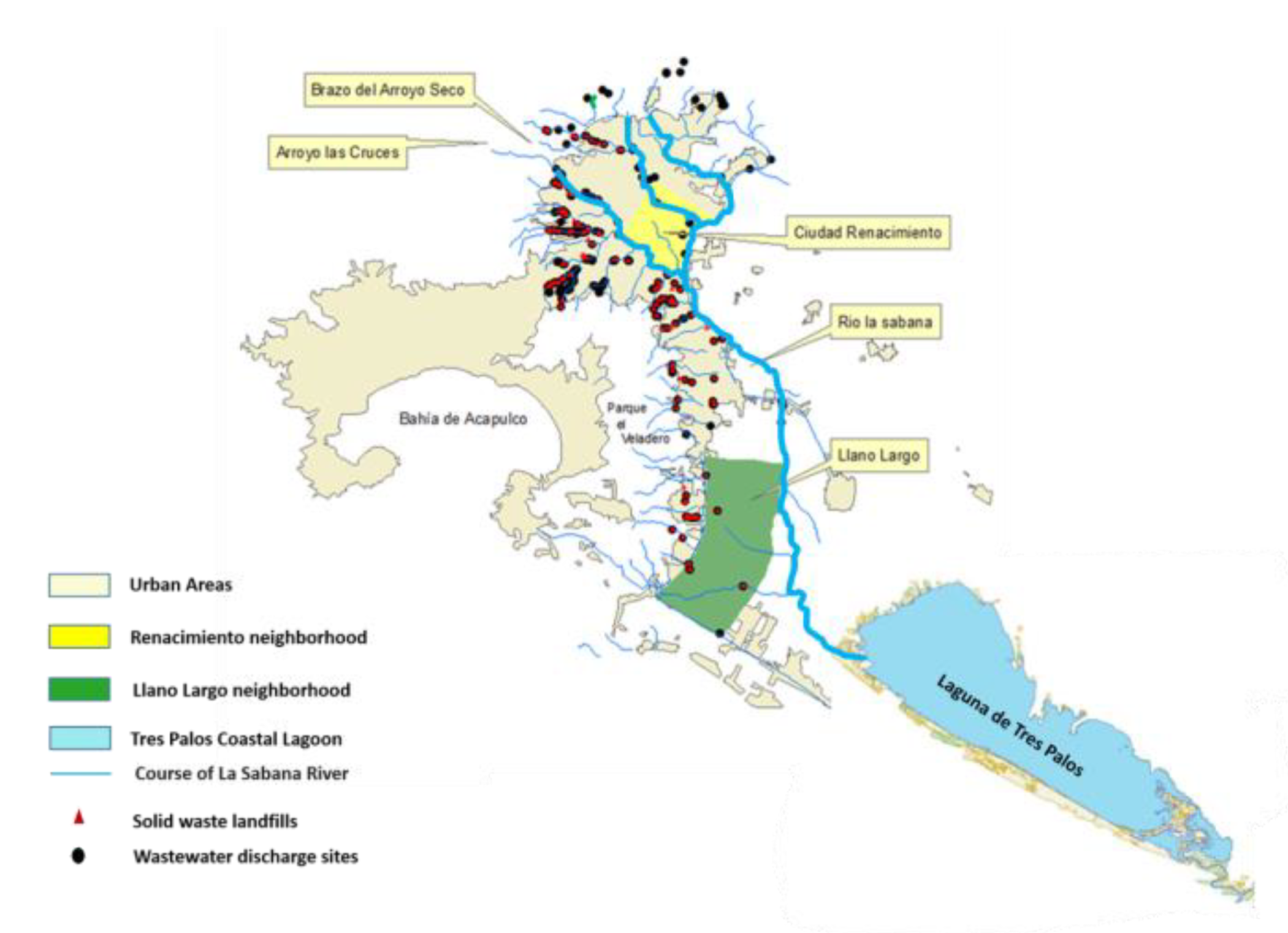

- Specific formal and informal settlements (along the river, around the lagoon and in urban areas), where sources of harmful elements have been identified;

- Extensions of urban areas through which the Sabana River flows, dragging and carrying solid waste and wastewater;

- Specific tourist activities that may generate harmful elements;

- Specific deficient urban services that contribute to the generation of harmful elements.

2.3. Building Harmful Semantic Pathways

3. Analysis and Discussion

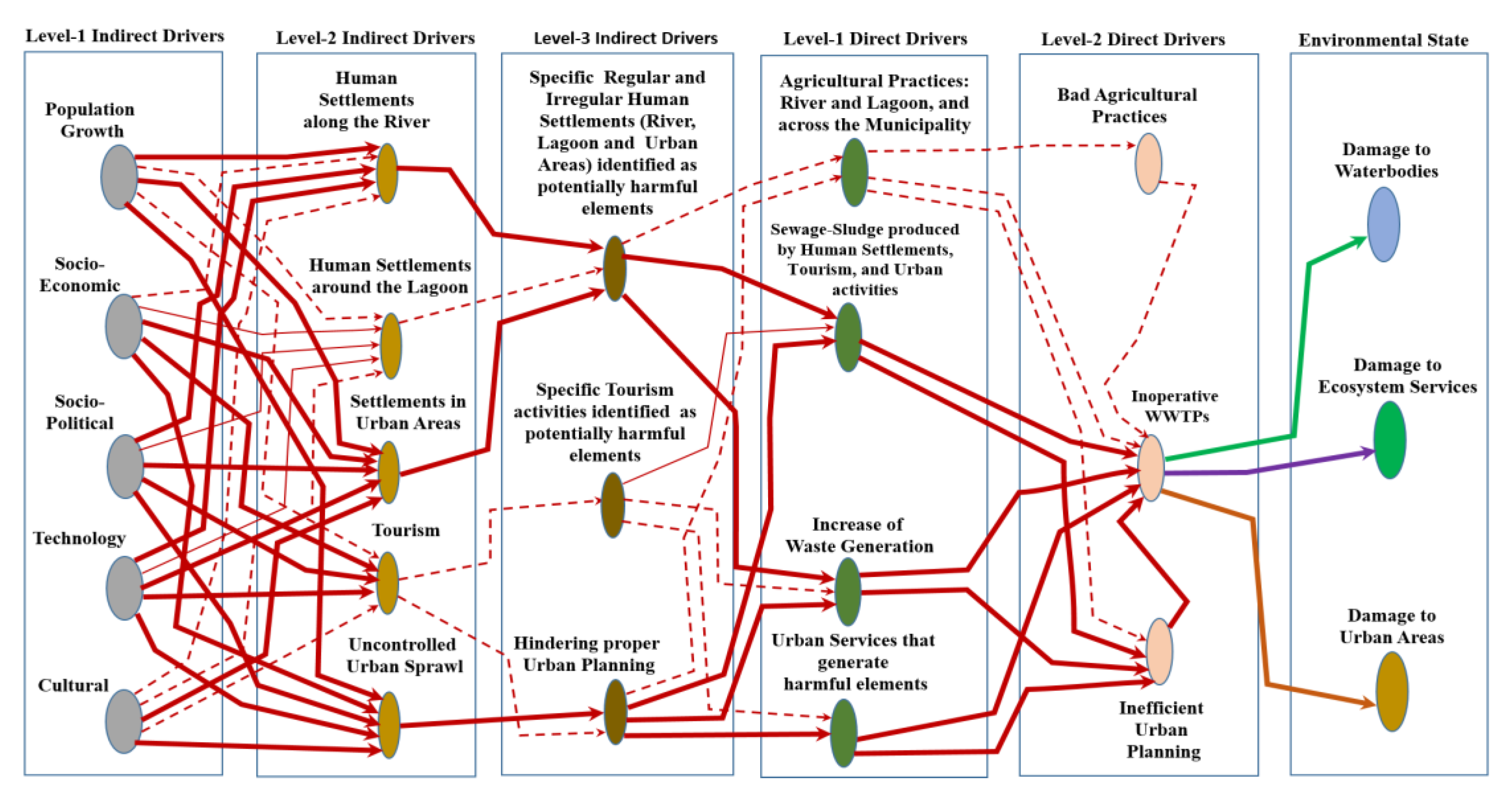

3.1. The Pathway of the Inoperative Wastewater Treatment Plants

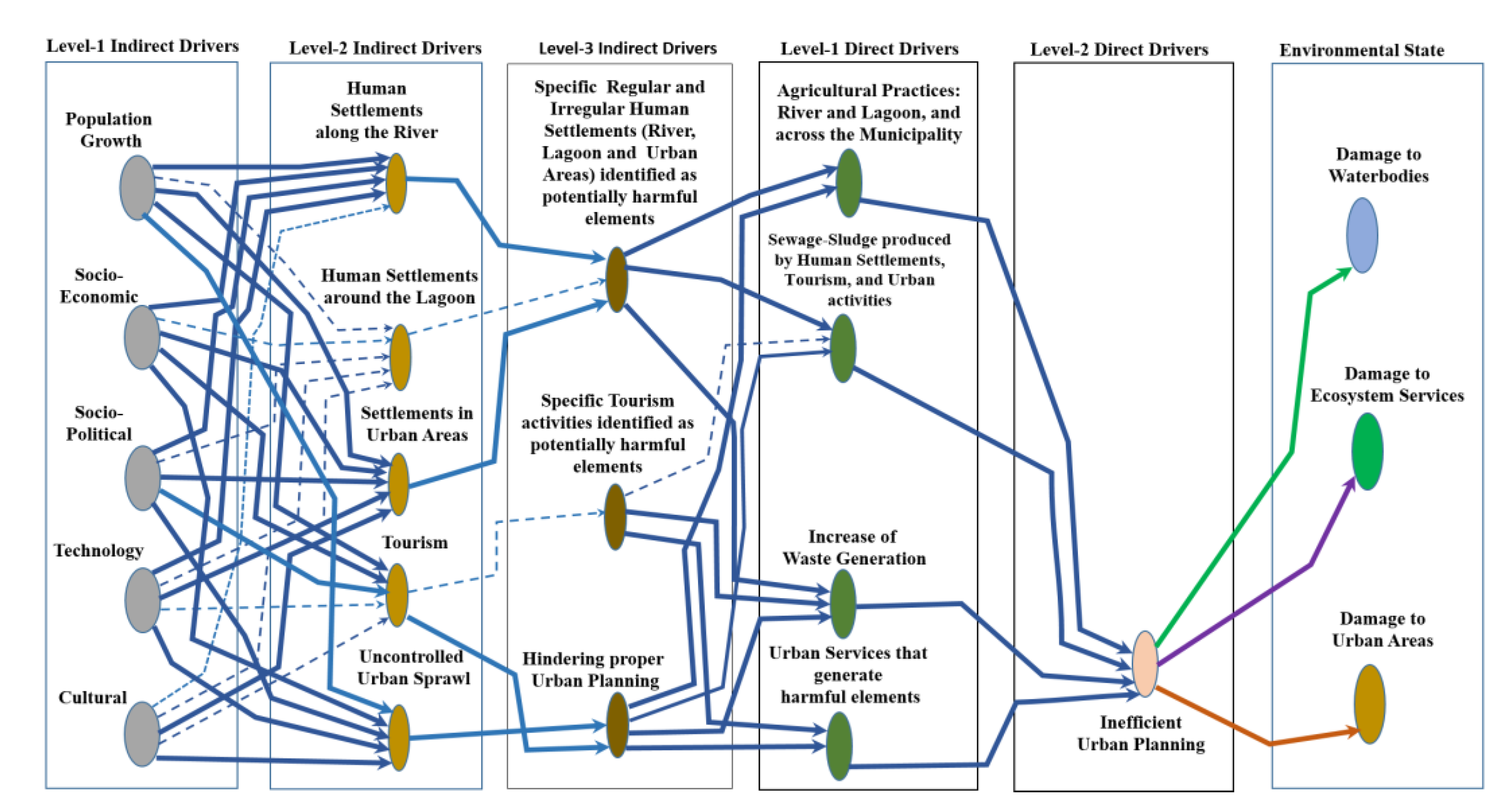

3.2. The Pathway of Inefficient Urban Planning

3.2.1. The Inefficient Development of Urban Planning

3.3. Interactions Between Drivers and Pressure Factors Using the DPSIR Framework

- The European study focused on lagoons and primarily on tourism. In contrast, our study considered waterbodies, ecosystem services, and urban areas with limited basic services;

- The coastal lagoons selected in the four European countries are seasonal tourist areas. However, our study considers all weekends of the year, in addition to traditional holyday periods, which exacerbates the problem, as damage to waterbodies, ecosystem services, and vulnerable urban areas increases considerably.

- The interactions between the driving and pressures factors represented at different levels of abstraction are not explicitly considered in the European Study. This is necessary to improve our understanding of these dynamics, which remains a significant challenge.

- We emphasize that a poor understanding of these dynamics leads to unreliable assessments of the environmental state. Therefore, a lack of understanding and assessment results in inadequate foundation decision-making processes.

3.4. Semantic Harmful Pathways

- i)

- Facilitate the understanding, analysis, and interpretation of the complex dynamics derived from multifactorial interactions, without providing complicated formulas.

- ii)

- They represent significant knowledge that supports the decision-making process to improve the management of wastewater by identifying more specific causes that lead to harmful factors.

- iii)

- Flexibility, where we can remove or add relationships to improve knowledge, which in turn strengthens the decision-making process. We can aggregate and integrate data from multiple heterogeneous sources into a unified and coherent knowledge base, providing a holistic view of the multifactorial process.

- iv)

- They are a useful option when a lack or absence of data hinders the construction of relationships. In such cases, experts can contribute to building understandable and interpretable relationships based on their experience with the real world.

- v)

- Improving communication in multidisciplinary contexts where decision-makers and stakeholders have diverse experience that contribute to the collaborative analysis of complex processes.

- vi)

- The explicit definition and representation of diverse relationships is a key advantage in building meaningful pathways to improve the understanding of the dynamics inherent in the complex process under study.

- vii)

- Reasoning and inference using semantic networks. For example, IF population growth “leads to” the expansion of urban areas and IF the expansion of urban areas “generates” more solid and liquid waste, Then pop-growth is an indirect harmful factor according to the law of transitivity.

- viii)

- Through the semantic networks, we can identify how various factors influence each other across multiple levels.

4. Conclusions

- This approach aims to represent a process where indirect drivers (anthropogenic factors) are considered intangible harmful factors that give rise to tangible harmful factors (direct drivers) affecting the efficiency of wastewater management, which in turn causes environmental damage. The environment state in this work encompasses waterbodies, ecosystem services and vulnerable urban areas.

- This approach also aims to facilitate understanding, analysis, and interpretation to identify the main harmful factors present in sematic pathways, constructed from a global semantic network. Four harmful semantic pathways have been defined to support decision-making in the selection of pro-environmental alternatives that improve the efficiency of wastewater management. The pathways labeled “Inoperative WWTP’s” and “Inefficient Urban Planning” were identified as the most harmful.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vélez, S.L.P.; Vélez, A.R. Recycling alternatives to treating plastic waste, environmental, social and economic effects: a literature review. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2017, 43, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, J.R.; Ilemobade, A.A.; Van Zyl, J. E. Treated wastewater reuse in South Africa: Overview, potential and challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 55, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, M.; Pasqualino, J.C.; Castells, F. Environmental assessment of urban wastewater reuse: Treatment alternatives and applications. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabirifar, K.; Mojtahedi, M.; Wang, C.; Tam, V.W.Y. Construction and demolition waste management contributing factors coupled with reduce, reuse, and recycle strategies for effective waste management: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.D.; Tseng, J.W.; Tseng, M.L.; Lim, M. K. Opportunities and challenges for solid waste reuse and recycling in emerging economies: a hybrid analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Waste management, waste resource facilities and waste conversion processes. Energy Convers. Manage 2011, 52, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Lee, C.; Yoon, O.S.; Kim, H. Medical waste management in Korea. J. Environ. Manage. 2006, 80, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, C.; Dal Pozzo, A.; Bonoli, A. Assessing the externalities of a waste management system via life cycle costing: The case study of the Emilia-Romagna Region (Italy). Waste Manage. 2022, 138, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWAP (UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2017. Wastewater: The Untapped Resource; UNESCO: Paris, 2017; Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247153.

- Heino, O.A.; Takala, A.J.; Katko, T.S. Challenges to Finnish water and wastewater services in the next 20–30 years. E-Water 2011, 1, 1–20. Available online: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/Heino-2011-Challenges.pdf.

- Spellman, F.R. Water & wastewater infrastructure: Energy efficiency and sustainability; CRC Press: New York, 2013; ISBN 13:978-1-4665-1786-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mema, V. Impact of poorly maintained wastewater sewage treatment plants-lessons from South Africa: Wastewater management. ReSource 2010, 12, 60–65. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC90239.

- Hernández-Chover, V.; Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Sancho, F. Cost analysis of the facilities deterioration in wastewater treatment plants: a dynamic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.K.; Englehardt, J.D.; Dvorak, A.C. Technologies for recovering nutrients from wastewater: a critical review. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2019, 36, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisner, M.; Neverova-Dziopak, E.; Kowalewski, Z. An analytical review of different approaches to wastewater discharge standards with particular emphasis on nutrients. Environ. Manage. 2020, 66, 694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, A.; Limonti, C.; Curcio, G.M.; Molinari, R. Advances in struvite precipitation technologies for nutrients removal and recovery from aqueous waste and wastewater. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajuria, A. Application on Reuse of Wastewater to Enhance Irrigation Purposes. Univer. J. Environ. Res. Technol. 2015, 5, 72–78. Available online: http://www.environmentaljournal.org/5-2/ujert-5-2-1.pdf.

- Castellanos-Estupiñan, Miguel A.; Carrillo-Botello, Astrid M.; Rozo-Granados, Linell S.; Becerra-Moreno, Dorance; García-Martínez, Janet B.; Urbina-Suarez, Néstor A.; López-Barrera, Germán L.; Barajas-Solano, Andrés F.; Bryan, Samantha J.; Zuorro, Antonio. Removal of nutrients and pesticides from agricultural runoff using microalgae and cyanobacteria. Water 2022, 14(no. 4), 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Yinfeng; Zhang, Ming; Tsang, Daniel CW; Geng, Nan; Lu, Debao; Zhu, Lifang; Igalavithana, Avanthi Deshani; et al. Recent advances in control technologies for non-point source pollution with nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural runoff: current practices and future prospects. Applied Biological Chemistry 2020, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U.A.; Havlík, P.; Schmid, E.; et al. Impacts of population growth, economic development, and technical change on global food production and consumption. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganivet, E. Growth in human population and consumption both need to be addressed to reach an ecologically sustainable future. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 4979–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacek, K.; Guan, D.; Barua, A. Changing lifestyles and consumption patterns in developing countries: A scenario analysis for China and India. Futures 2007, 39, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, V.; Cai, J.; Taka, M.; Kummu, M.; Varis, O. China’s sustainable water-energy-food nexus by 2030: Impacts of urbanization on sectoral water demand. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Hoogeveen, J.; Steduto, P. Some insights in the effect of growing bio-energy demand on global food security and natural resources. Water Policy 2008, 10, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Odorico, P.; Davis, K.F.; Rosa, L.; et al. The global food-energy-water nexus. Rev. Geophys. 2018, 56, 456–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.A.; Sohag, K.; Abdullah, S.M.S.; Jaafar, M. CO2 emissions, energy consumption, economic and population growth in Malaysia. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2015, 41, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Suresh, C.P.; Dey, A.N.; Shukla, G. Deforestation: causes, effects and control strategies. Global Perspect. Sustain. For. Manag. 2012, 1, 1–26. Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/books/globalperspectives-on-sustainable-forest-management/deforestation-causes-effects-and-control-strategies.

- Maja, M.M.; Ayano, S.F. The impact of population growth on natural resources and farmers’ capacity to adapt to climate change in low-income countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, L. M.; Newig, J. Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Palmer, M.; Richards, K. Enhancing water security for the benefits of humans and nature—the role of governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, S.R. Toward good governance and sustainable development: The African peer review mechanism. Governance 2055, 18, 283–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortajada, C. Water governance: some critical issues. Int. J. Water Resource. Dev. 2010, 26, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzawska, A.; Brey, P. Principles and approaches in ethics assessment. Institutional Integrity, University of Twente. Project stakeholders acting together on the ethical impact assessment of research and innovation (SATORI). 2015. Available online: https://www.4tu.nl/ethics/downloads/default/files/annex1.a-ethical-impact-assessmt-cia.pdf.

- James, M. Institutional Integrity. an essential building block of sustainable reform. 2018. Available online: https://effectivecooperation.org/system/files/2019-04/41.pdf.

- OECD. OECD/LEGAL/0381; Recommendation of the council on policy coherence for sustainable development.

- Hellström, D.; Jeppsson, U.; Kärrman, E. A framework for systems analysis of sustainable urban water management. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbakidze, M.; Hahn, T.; Zimmermann, N.E.; et al. Direct and indirect drivers of change in biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people. In IPBES (2018): The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Europe and Central Asia;Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services;Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES); Rounsevell, M., Fischer, M., Rando, Torre-Marin, Mader, A.A., Eds.; Bonn, Germany, 2018; pp. 385–568. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11568/1055836.

- Gideon, I.K.; Onyema, M.; Daniel, K.S. Assessment of indirect drivers of mangrove destruction in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Sustain. Prod. Consump. For. Prod. 2023, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Balvanera, P.; Pfaff, A.; Viña, A.; et al. Status and trends – drivers of change. In Global assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services; Brondízio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; IPBES secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; p. 152 p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Mohammad, F. Eutrophication: challenges and solutions. In Eutrophication: causes, consequences and control; Ansari, A., Gill, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Quintana, et al. Feasibility Analysis of the Sustainability of the Tres Palos Coastal Lagoon: A Multifactorial Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13(no. 2), 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheireldin, K.; Fahmy, H. Multi-criteria approach for evaluating long term water strategies. Water Int. 2001, 26:4, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRUZ VICENTE, Miguel Ángel; MONTESILLO CEDILLO, José Luis; ORTEGA RAMÍREZ, Guadalupe Olivia. Disminución y Recuperación de la Actividad Turística en Acapulco. De la pandemia por Covid-19 al huracán Otis. 2024. Available online: https://ru.iiec.unam.mx/6544/1/16-%20045-Cruz-Montesillo-Ortega.pdf.

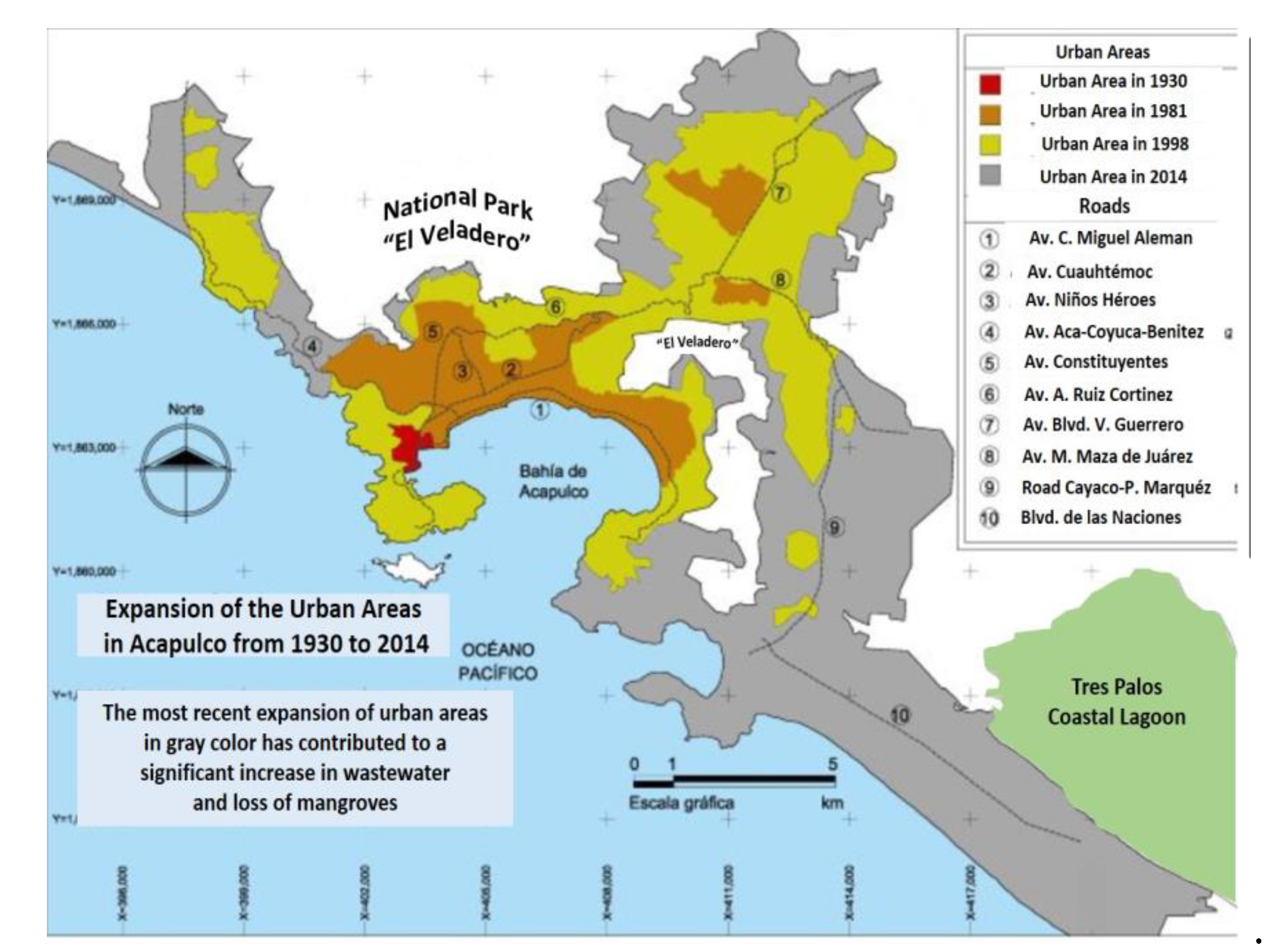

- CASTILLO, Edder Agustín Barrera; ALARCÓN, Iliana Villerías. Análisis espacio–temporal de la transformación urbana de Acapulco 1930-2020. Ciencias Espaciales 2025, vol. 16(no 1), 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DORANTES, Elizabeth Espinosa; HERNÁNDEZ, Jesús Flores. Cartografía en áreas urbanas costeras. Acapulco y el huracán Otis. DECUMANUS. REVISTA INTERDISCIPLINARIA SOBRE ESTUDIOS URBANOS. 2023, vol. 12, no 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas Gómez, E.P. Crecimiento y planeación urbana en Acapulco, Cancún y Puerto Vallarta (México). 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, L.; Rodríguez, C.; Castro, M.; Aparicio, J. L.; Marmolejo, C.V. Prospectiva Ambiental para la Laguna de Tres Palos, Municipio de Acapulco, Guerrero, México. XIII CTV 2019 Proceedings: XIII International Conference on Virtual City and Territory: “Challenges and paradigms of the contemporary city”: UPC, Barcelona, October 2-4, 2019; CPSV: Barcelona, 2019; p. 8610, ISSN 2604-6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovilla, C.; Pérez, J.C.; Arce, A.M. Gestión litoral y política pública en México: un diagnóstico. In manejo costero integrado y política pública en Iberoamérica: un diagnóstico. Necesidad de Cambio. In Red IBERMAR (CYTED); Muñoz, Barragán, J.M., Eds.; Cádiz, 2010; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Niva, V.; Taka, M.; Varis, O. Rural-urban migration and the growth of informal settlements: A socio-ecological system conceptualization with insights through a “water lens. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, V.; Taka, M.; Varis, O. Rural-urban migration and the growth of informal settlements: A socio-ecological system conceptualization with insights through a “water lens”. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, D.M.; Elsayed, H.G. From informal settlements to sustainable communities. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, V.; Sarmiento, J.P. A neglected issue: Informal settlements, urban development, and disaster risk reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2020, 29, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Senante, M.; Hernández-Sancho, F.; Sala-Garrido, R. Economic feasibility study for wastewater treatment: A cost–benefit analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 4396–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Anda, J.; Shear, H. Sustainable wastewater management to reduce freshwater contamination and water depletion in Mexico. Water 2021, 13, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáñez-Cota, A. Plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales municipales en México: diagnóstico y desafíos de política pública. Tecnol. y Cienc. del Agua 2022, 13, 184–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

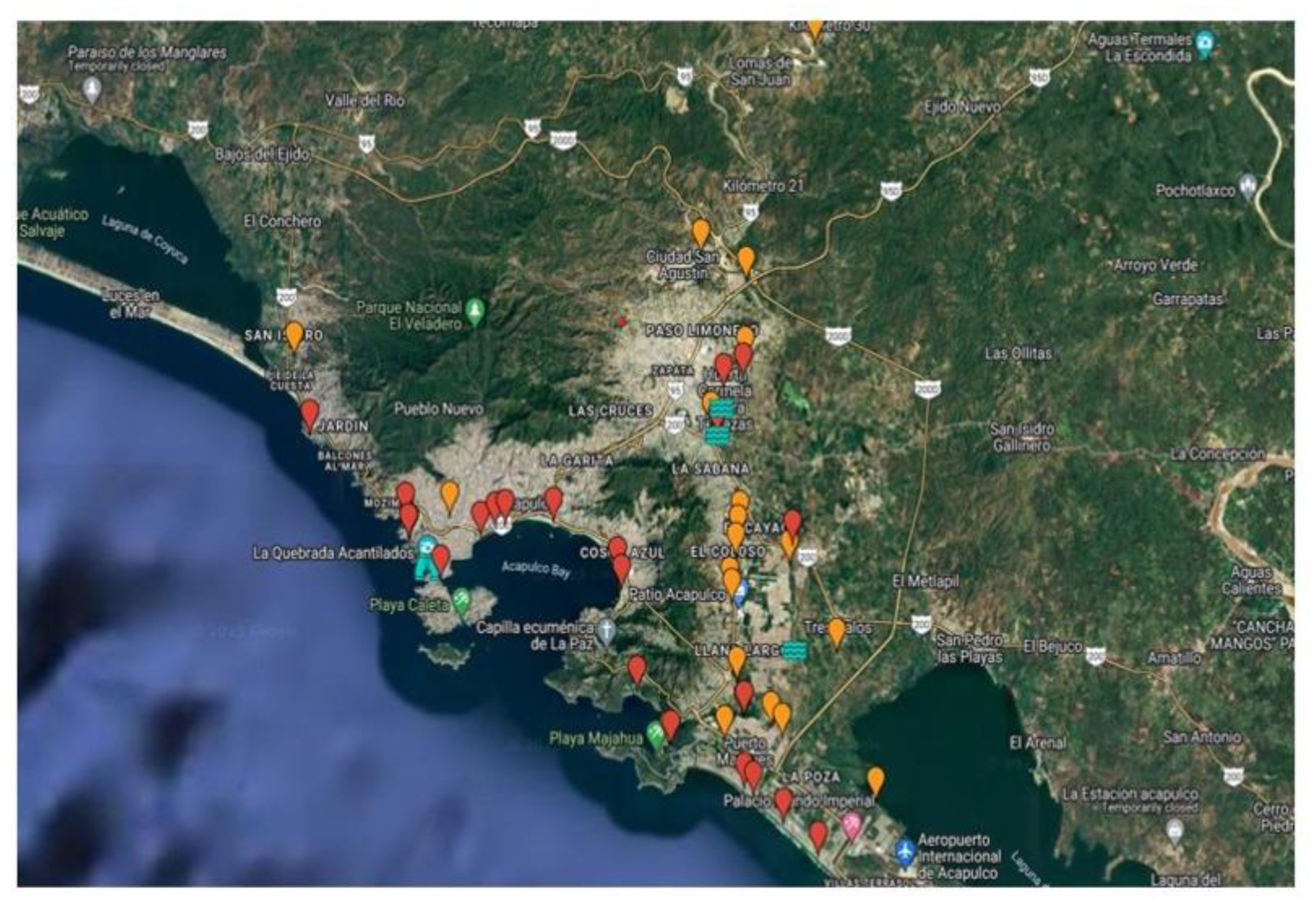

- WWTPs and wastewater discharged sites. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1ngTpVhASoxx_ObXMQQ9qNVhZU-g&ll=16.87793907500828%2C-99.86284195000002&z=12.

- Rodríguez, Fernández; Gustavo, Anastacio; de la Fuente, Mariana Figueroa; Alonso, Ariel Ramón Medina; Cocom, Mirna Yasmin Pacheco. Migración interna y dinámicas laborales en la industria turística de la Riviera Maya, Quintana Roo, México. Revista ABRA 2020, 40(no. 60), 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carte, Lindsey; McWatters, Mason; Daley, Erin; Torres, Rebecca. Experiencing agricultural failure: Internal migration, tourism and local perceptions of regional change in the Yucatan. Geoforum 2010, 41(no. 5), 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, V.; Taka, M.; Varis, O. Rural-urban migration and the growth of informal settlements: A socio-ecological system conceptualization with insights through a “water lens”. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, D.M.; Elsayed, H.G. From informal settlements to sustainable communities. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, V.; Sarmiento, J.P. A neglected issue: Informal settlements, urban development, and disaster risk reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2020, 29, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Anda, J.; Shear, H. Sustainable wastewater management to reduce freshwater contamination and water depletion in Mexico. Water 2021, 13, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáñez-Cota, A. Plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales municipales en México: diagnóstico y desafíos de política pública. Tecnol. y Cienc. del Agua 2022, 13, 184–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar; Covarrubias, Felipe; Herrera, América Libertad Rodríguez; Castro, Erick Alfonso Galán; Vargas, Manuel I. Ruz; Umaña, Maximino Reyes. La participación y gobernanza en la planeación urbana de Acapulco. Regions and Cohesion 2022, 12(no. 3), 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Production and Consumption. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/production-and-consumption?activeTab=07e50b68-8bf2-4641-ba6b-eda1afd544be&activeAccordion=4268d9b2-6e3b-409b-8b2a-b624c120090d.

- Herrera, Rodriguez; Libertad, America; Salomé, Branly Olivier; Velasco, Rocío López; Mendoza, María del Carmen Barragán; Villareal, Roberto Cañedo; Pérez, Miguel Ángel Valera. La contaminación y riesgo sanitario en zonas urbanas de la subcuenca del río de la Sabana, ciudad de Acapulco. In Gestión y Ambiente; 2013; ISSN 0124-177X. [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli, Asunción; Lima, María Lourdes; Ondarza, Paola Mariana; Esquius, Karina Soledad; Massone, Héctor Enrique. A decision support tool for water pollution and eutrophication prevention in groundwater-dependent Shallow lakes from Periurban areas based on the DPSIR framework. Environmental Management 2021, 68(no. 3), 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovko, M.; Melkić, S.; Marković Vukadin, I. Application of the DPSIR framework to assess environmental issues with an emphasis on waste management driven by stationary tourism in Adriatic Croatia. Geoadria 2021, 26, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, Do Thi Thu; Ha, Nguyen Thi Thu; Do Khanh, Gia; Van Thanh, Nguyen; Hens, Luc. Sustainability assessment of coastal ecosystems: DPSIR analysis for beaches at the Northeast Coast of Vietnam. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2022, 24(no. 4), 5032–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolbeth, M.; Lillebø, A. I.; Stålnacke, P.; Gooch, G. D.; Sousa, L. P.; Alves, F. L.; Soares, J.; et al. The DPSIR framework applied to the society vision for tourism in 2030 in European coastal lagoons. coastal lagoons in Europe 2015, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Year |

Number of Tourists |

Hotel Occupancy |

Economic Impact (millions of Mexican pesos) Current exchange: 1 usd = 18.23 mp) |

| 2018 | 9,891,776 | 49.3% | 34,275.0 mp |

| 2019 | 10,228,539 | 51.7% | 35,441.9 mp |

| 2020 | 6,192,520 | 31.3% | 21,456.5 mp |

| 2021 | 6,405,048 | 34.4% | 28,822.7 mp |

| 2022 | 8,172,730 | 47.6% | 62,656.2 mp |

| 2023 | 6,198,391 | 53.5% | 47,520.0 mp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).