1. Introduction

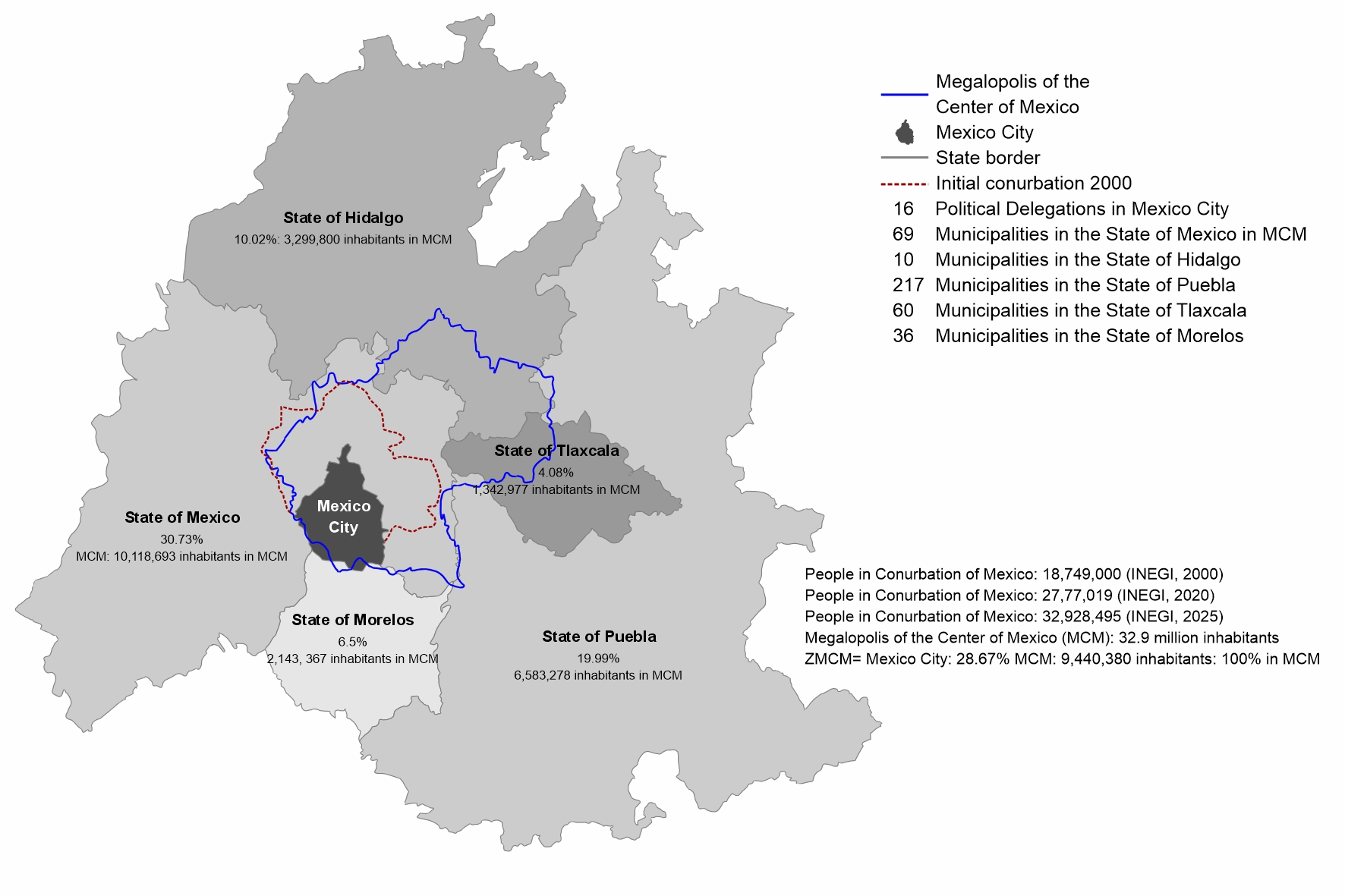

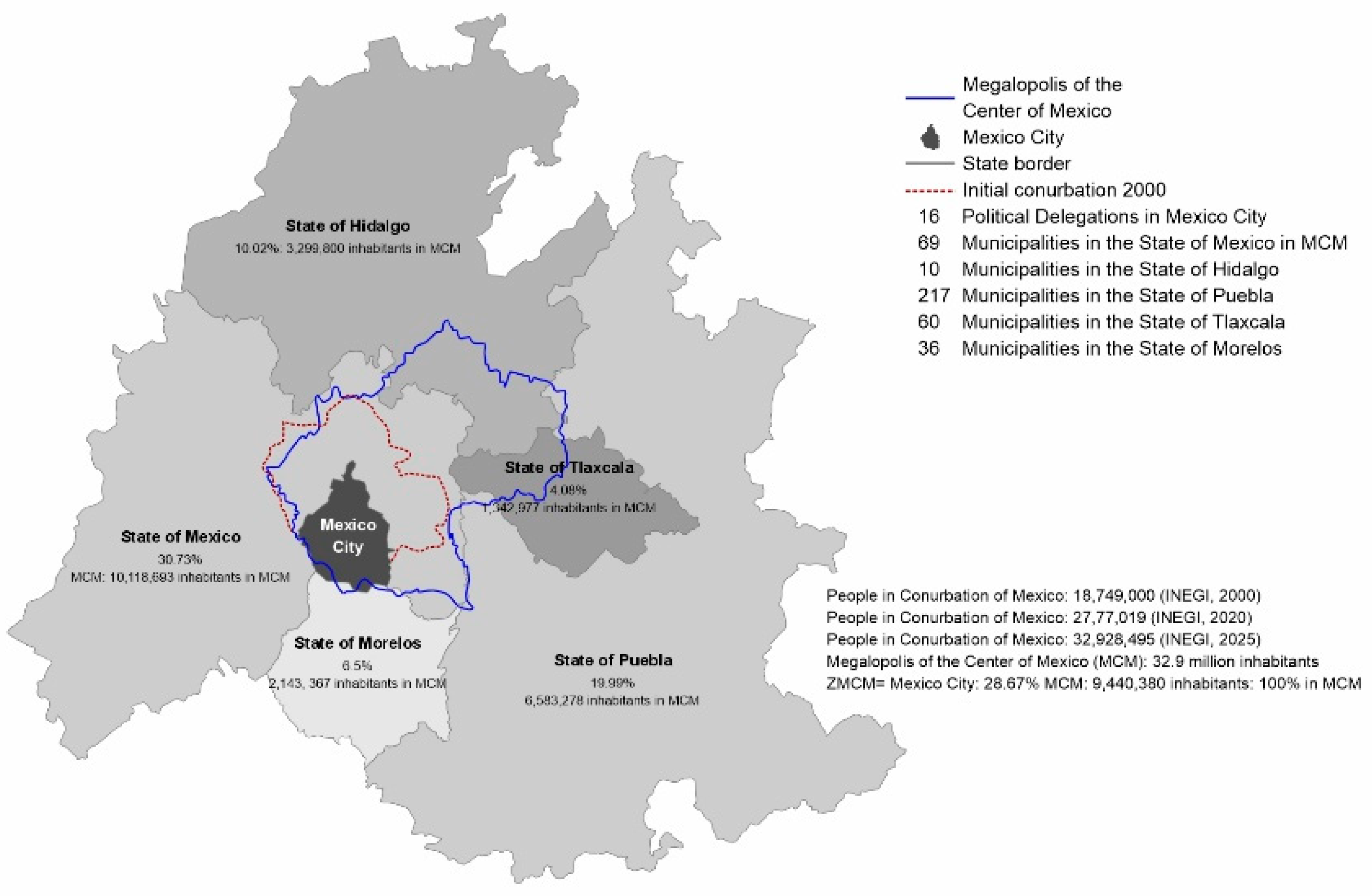

The World Resource Institute [

1] indicated that the Megalopolis of Central Mexico (MCM) with more than 32 million inhabitants could be out of clean water in 2028, so the study proposes an open, self-regulating and dissipative systemic model in which an interdisciplinary study group got involved [

2]. It integrates a participative research process with citizens and governmental participation including women and indigenous communities to strengthen their organizational capacities [

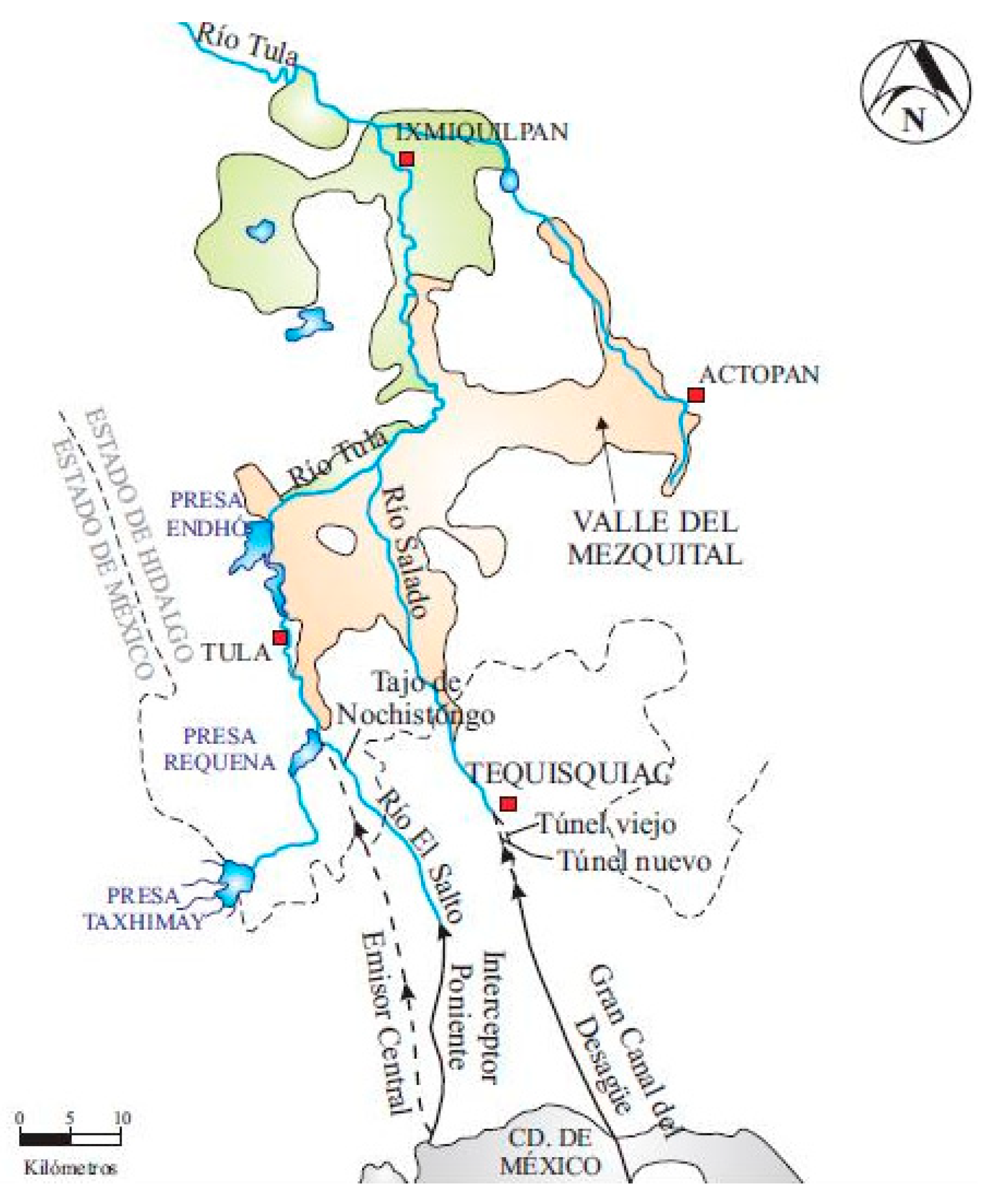

3]. This procedure may allow a collective development of sustainable socio-environmental alternatives for a long-term hydrological supply capturing rainfall from the Water Forest surrounding the volcanos around the MCM. The article criticizes the past hydraulic policies based on water extraction from neighbor states and overexploitation of aquifers, including mixing sewage from industries, domestic use, and rainfall, which is expelled to a deserted region in the Hidalgo State. During the monsoon 2024, this toxic wastewater inundated marginal colonies, such as the 32-day flood to almost half a million inhabitants in Chalco, located in the eastern part of México State [

4].

The research project also explores alternative hydrological approaches guaranteeing in the long-term water supply to the MCM with an integrated water resources management (IWRM), the recovery of protected natural areas (PNA), and the rescue of the Water Forest [

5], called also SANBA. It includes urban planning, the protection of areas with high rainfall infiltration and a culture of saving, the reuse of gray water, the infiltration of sanitized wastewater in situ to the endorheic basin of the megalopolis, where multiple eco-technologies exist to rescue the overexploited aquifers and reduce the growing subsidence in the city [

6]. Climatic risks and increasing droughts oblige authorities and committed citizens to restore lost wetlands and rivers through sustainable management of the water forest [

7]. Women are suffering seriously from periodic water shortages and supply interruptions. They have developed a culture of saving, reusing, and recycling water in their homes with rainwater collection and sanitation of domestic wastewater. Indigenous communities have for thousands of years protected the water forest in the mountains surrounding the MCM [

8].

The article includes a participative research methodology [

9] and the elaboration of a digital platform among water users and indigenous communities with a flow chart indicating potential tipping points [

10]. It explores natural-based mechanisms [

11] to mitigate water shortages and sewage in the megalopolis. It combines “high-tech with no-tech for achieving climate and sustainability objectives and improving the livability of cities in hot and arid regions” [

12]. The digital platform is elaborated with the participating communities and based on surveys and collective working groups, integrating a dynamic self-organizing and open system [

13]. This platform is reinforced by free available satellite data and indicates the upcoming risks to climate change [

1], where higher temperatures affects the development of forests [

14]. Threats are also related to the clandestine logging of trees and other illegal activities by the organized crime [

15].

The objective of the research is to collaborate with communities caring about the Water Forest using participative methodologies. The research group develops a digital platform, where Indigenous communities and organized women are involved and managing their own data. The collective research consolidates the MCM water security with sustainable management and a culture that provides a clean water supply and integrated sewage in the long term for the entire population in the megalopolis [

2]. The policies developed are discussed with authorities from the three states, business communities, organized citizens, the legislative, where independent citizens’ auditing group analyses the access in equal conditions to safe water and improved sewage. The project focus on the endorheic basin of the megalopolis in the center of Mexico (MCM), where increasing droughts [

16] and floods must be mitigated as a result of climate change impacts [

17].

3. Results and Alternative Proposals

Wang et al. [

68] documented that the crucial resource for people's lives, plants, animals, and humidity in the air is water. They insisted on an increasing loss of safe water in 2050, both in quantity and quality of water, charged with multiple pollution, especially nitrogen from agricultural activities. As explained in the methodological subchapter, the complex, open, dissipative, and self-regulating system implies sustainable water management, where the present engineering technologies of water supply and sewage in the MCM are unsustainable and costly for nature and people. This policy was taken for granted for decades among citizens and the three levels of government. It included corruption among water authorities, disadvantageous privatization processes [

69] in illegal concessions, and missing transparency for alternative sustainable water management. Continuing with this historical water supply and sewage may create threats for the 32 million inhabitants in the MCM by a growing lack of drinking water, sewage pollution, excessive cost, and air contamination by pumping water from depths aquifers and neighboring states. The end-result is lack of safe water and sustainable sewage.

A dissipative, self-regulating, and open system approach revises the negative and unsustainable hydraulic system processes by exploring feasible, nature-based alternatives by reducing progressively the costs. In a sustainable water security, the whole society of the MCM with the government must be involved. It includes at least 16 interrelated processes, which should be developed simultaneously.

3.1. Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM)

Provides a safe water supply with a sustainable reuse of treating wastewater. The rapid urbanization produced the transformation of rivers and canals into avenues such as Río Churubusco or Canal de Miramontes, impossible to be restored. However, the remaining rivers, ravines, multiple small lakes, dams, and wetlands can be recuperated, urban areas reforested and Water Forests restored. The government alone can´t control the complexity of the urban expansion and only with citizen participation, especially women and Indigenous, and a strict application of existing laws the remaining natural resources can be conserved.

3.2. Rainfal Infiltration

Inside the MCM basin is crucial to grant clean water to all citizens, avoiding its expulsion to the Hidalgo State. The first step is to eliminate the mixture of domestic and industrial toxic sewage with rainwater. The Water Forest provides most of the rain in the MCM basin. Using this rainwater directly in the infiltration to the groundwater with drainage systems such as ditches, infiltration wells, and infiltration areas, as well as the implementation of urban management measures such as green roofs and bio-filters. To limit extreme floods, the forest and the soils covering the volcanoes must be restored and protected (see numbers 11 & 12). Healthy forestry and soils facilitate a slower infiltration from the mountains surrounding the MCM, where the highest rainfall occurs. Both also limit catastrophic flooding in the plains, mostly former dried-out lakes and today densely populated. Rainwater recharge into the aquifers, instead of expulsing this resource outside the endorheic basin, is an urgent priority, defined by the newly elected government in December 2024. This sustainable policy still faces opposition from beneficiaries of the unsustainable engineering system, including inside the National Water Commission. Especially private illegal concessions granted in the past on overexploited aquifers [

48] and the presence of organized crime logging the most crucial trees for infiltration, not only limits recharge but also threatens the Indigenous communities and organized women's groups who have opposed this depredation at the local level. Improving rainwater capture in the entire MCM during the wet season is crucial to restoring the overexploited aquifers and reducing the growing subsidence.

3.3. Granting Clean Water to Ewverybody

Prigogine [

13] proposed an integrated system approach, where the solutions are far away from the existing equilibrium of the present engineering solutions. They include the dissipative complexity of urban factors, socioeconomic variables, productive activities, and sustainable water culture, obliging to overcome the destructions produced by the longtime and recent neoliberal Patriacene [

70] instead of the undefined Anthropos in the conceptualization of the Anthropocene [

71]. Reducing the expulsion of sewage from an endorheic basin improves the management of increasing extreme climate change events. The greater infiltration of rainfall reduces also the growing subsidence. The L-C system originally managed a supply of 25.5%, which represents for the long-term an unstable alternative and greater water supply insecurity to the MCM. The government was obliged during the last decade to reduce for months this additional supply from the L-C, because the storage capacity of dams and lakes was only 37.9% in February 2024 [

51], before the hotter months started. The eradication of excessive pumping of 66.3% of water from 53% of overexploited aquifers produces subsidence and microseisms. Besides high electricity costs due to the elevation of 1,100m over the mountains [50: 16] by the L-C system and from the 970 deep wells, the pumping pollutes the air, while water extraction from neighboring states is also destroying their ecosystems.

3.4. Domestic Sewage

Should never be mixed with industrial toxic wastewater. Both sewages must be progressively treated. The industrial wastewater should be recycled inside the enterprise or cleaned up by the business. Expulsing a mixed toxic drainage from an endorheic basin to a desert region in the Mezquital, Hidalgo, deprives the megalopolis of a crucial resource for recharging its aquifers. The NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021 establishes the maximum permissible limits for pollutants. By separating, recycling, and sanitizing industrial water inside the enterprises and treating domestic wastewater independently, precipitation can be infiltrated directly into the aquifers, and special tools for infiltration may limit periodic dangerous floods. Domestic sewage could be treated directly in housing complexes and colonies with aquatic plants in bio-digesters, enhancing the urban image, improving air humidity, and reused in gardens or parks, and recharged slowly into the aquifers. Official data indicate that only 4,164m3/s of domestic wastewater are recycled inside the basin [50: 32]. This domestic infiltration could gradually increase up to 64,184 m3/s, today pumped outside from the endorheic basin. When safely sewage, it can be slowly recharged into the MCM aquifers. This requires an alternative governmental-citizen policy, clear legal applications with new laws in building complexes, houses, and colonies, some subsidies, and new investments in marginal suburbs for increasing missing water and sewage services.

However, domestic sewage could also contain some toxins from medicines and personal cleaning products, called emergent pollutants, which could not be treated by the proposed biological means [

72]. Industrial voracity often uses toxic substances not officially permitted in Mexico. They are very dangerous for natural and human health, forbidden for years in all developed countries and still used in our country. This toxic contamination is not regulated in Mexico by the existing norms and there does not exist any restoration for these dangerous products, with high health care costs for chronic diseases.

3.5. Industrial Sewage

Is highly complex and the lack of governmental norms and a lax application of environmental laws facilitated irresponsible businessmen to use toxic components forbidden in developed countries. There are missing lists of allowed and not hazardous industrial components. The present situation requires deep changes in the toxicological management. Today, the industrial and domestic sewage is mixed up with rain and expelled out of the endorheic basis of the MCM. Separating first rainfall, sewing domestic wastewater locally, and infiltrating both into the ground reduces the management of toxic sewage. Industries recycle only 1,000 m2/s of their officially monitored 4000 m2/s, while Conagua did not register all the industrial discharges [

73] and does not know the complex toxic components. The Australian Government proposed in the year 2000 the application of multiple barriers for reusing sewed industrial water, a similar principle is also applied for drinking water. Their principle is prevention and more efficient barriers minimize the risks of unknown toxic components, improving the quality of safe water. Milquez & Montagut [

72] recommend recycling industrial wastewater inside the enterprises by limiting the pollution of unknown emergent pollutants in the water, avoiding harm to health of people and nature.

The MCM signed with a private enterprise a concession for the next two decades, limiting the reuse of rain and sewed water into the aquifer of the endorheic basin. The firm built the greatest treatment plants in Latin America in Atotonilco, Hidalgo, with one drain for physical-chemical industrial pollution and two drains for biological domestic wastewater and rainfall. All treated waters irrigate crops in the deserted region of the Mezquital in the same state. By developing new drainage systems in the growing neighborhoods in Mexico State and outside the basin, this sewage water may compensate for the signed water sewage amount by contract. Conflicts with farmers could also be resolved by irrigation efficiency, where enough water is given for producing vegetables and other products, whenever the emergent pollutants in industrial waters could produce harm in the crops. In the past, the raw sewage was directly used in the irrigation in the Mezquital before the treatment plant was constructed and has polluted the aquifers of people depending on this water with catastrophic effects [

74].

3.6. Overexploitation of Aquifers

The overexploitation of aquifer is creating up to 40 cm per year of subsidence in the lacustrine subsoils, while climate change is increasing drought, obliging to provide more water and overexploiting the aquifers. More extraction of the subsoils also worsens the water quality due to dissolved minerals [

66]. The progressive collapse in the subsoil is affecting public services, avenues, and urban infrastructure, such as Terminal 2 of the international airport or the frequent interruptions of the metro [

52]. Especially damaged are the distributing pipes for drinking water and the drainage systems, which can pollute water supply with sewage [

51]. Earthquakes are frequent in the region and the subsidence is also producing microseism in the densely populated part of the valley, especially the colonies built on former lakes. Recharging aquifers with the capture of rainfall prevents the deterioration of the entire infrastructure in the endorheic basin.

3.7. Flood-Prone Plain of MCM

Before the Spaniard conquest, Tenochtitlán was covered by multiple lakes and managed by Indigenous engineers. Today, these lakes are dried-out and densely populated colonies are frequently flooded during extreme weather events related to climate change. The existing Eastern Gran Canal, initially built by the Spaniards, emits noxious odors and is broken in different parts. Lack of maintenance, subsidence, frequent earthquakes, and unplanned growth of neighborhoods built on dried-out lakes and the increase of climate events, threatens these colonies. During the rainy season, great risks are coming especially from this drainage system, which expels the toxic sewage out of the endorheic basin. Recycling separated rainwater and treated domestic wastewater infiltrated could simultaneously resolve several problems. It reduces the overexploitation of groundwater, the electric pumping costs from deep aquifers, air pollution from GHG, and the increasing subsidence that is destroying the entire urban infrastructure, buildings, and the metro, built-up in the former unstable lacustrine subsoil [

52]. It would avoid also the periodic floods by the existing collapsed drainage systems with unhealthy wastewater, where unconscious people also dump their solid waste inside this open sewage. This generates garbage blockages by solid waste, toxic sewage, and sludge, where inundations are affecting the health of dozens of thousands of inhabitants in the poor suburbs [

6].

Especially sewage-flood prone is the eastern region on dried-out lakes, such as Chalco, which was flooded for 34 days in 2024 with toxic wastewater, impeding any economic, social, and public activities. The sewage flood came from the destroyed eastern drainage system and the local blockages of solid waste trashed by citizens. These marginal colonies also miss safe water supply and mostly an efficient sewage treatment. Several committed groups are cleaning with citizens during the dry season the potential accumulation of solid waste, protecting marginal neighborhoods from toxic wastewater floods. These activities create also among affected people an alternative environmental culture [

75], where solid waste can be recycled and drainage cleaned inside the home by cheap eco-techniques.

3.8. Urban Greening

[

11] includes the recovery of aquifers, the elimination of subsidence, the reuse of rainfall, and the mixture of toxic sewage. Women and concerned citizens have been actively involved in reducing water scarcity during the dry months by storing rainfall in their houses. Greening urban areas, including the recovery of small lakes, dams, and wetlands, and the collective restoration of rivers and ravines, today mostly converted into garbage dumps, implies alternative customs. Changing cultural habits of throwing away garbage requires social involvement with a reeducation of past unsustainable behaviors together and the application against infractions based on existing laws. The revegetation in urban areas also reduces heat spots, where new trees could stabilize the temperature during the hot months inside the houses. Green gardens on roofs or walls, bio-digesters with aquatic plants, and treated domestic sewage reused in parks, gardens, and medians between avenues create more atmospheric humidity. Planting green areas or parks in new colonies and massive reforestation of trees limits heat inside buildings or offices and improves air quality during the whole year. The collective restoration of forests, rivers, and ravines, often converted into garbage dumps or sewage, improves clean rainfall infiltration.

Local bio-digesters for domestic drainage, urban greening, rainwater collection, and water-saving practices are mostly promoted by women. They improve life quality in the poorest neighborhoods. Among citizens, rainwater storage, green roofs, and recycling facilities inside the households also reduce the demand for drinking water. Committed women and environmentalists have also explored additional natural solutions for saving water and improving life quality. In most of these participative processes, unpaid female domestic labor is given for free, mitigating the present water scarcity and providing hygienic conditions to their families by granting water to everybody.

3.9. Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Climate conditions are deteriorating in the MCM and historical droughts in the megalopolis have occurred during the past millennia, producing important socioeconomic and political changes and conflicts among affected people. Graeber & Wengrow [

76] explain the disintegration and abandonment of a thriving cultural consolidation in Teotihuacán. Hunger and epidemics related to extreme weather events, unsustainable food production with hunger, and growing social nonconformity occurred before the Spaniard's conquest. Escobar [

30] insisted that the lack of food and epidemics pressured social unrest after 1900. Florescano [

31] documented that a long drought with increasing poverty and hunger was crucial to ally the urban bourgeoisie with the peasantry for achieving the Independence of Mexico from Spain.

3.10. Increasing Droughts

Climate change impacts have produced increasing droughts in the center of Mexico, related to higher temperatures, irregular precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events. Dams and lakes providing water to the MCM were drying out during the last years and extreme weather events have flooded entire suburbs in the densely populated plains. National Water Commission reported on September 30, 2024, that drought prevails with 51.3% extreme, 33.9% moderate, and 14.7% exceptional drought in the MCM. The year 2024 became also the warmest year on record, with an average temperature anomaly in Mexico of 2.14 ºC, concerning 1900-1930, surpassing 2017 by almost 0.4 ºC. Climate change mitigation [

47] implied a reduction of water supply by the government and drought adaptation was assumed by unpaid female domestic labor with savings, reuse, recycling, and water storage to provide well-being for their families.

3.11. Policy Activities and Citizen Participation

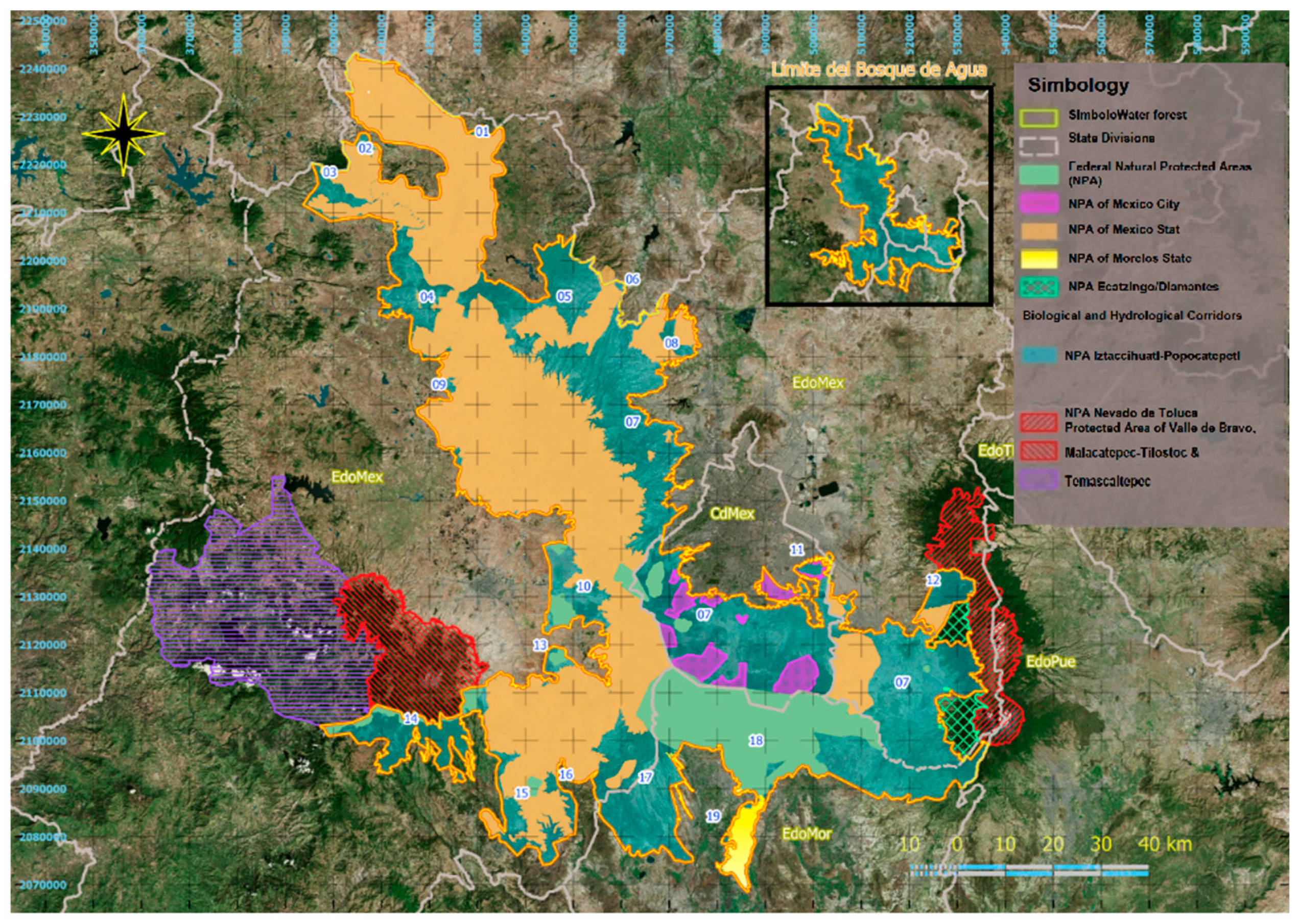

Policy activities and citizen participation are crucial to achieve sustainable water security, especially with the participation of organized women. In January 2025, the three key authorities from Mexico City, State of Mexico, and Morelos signed collectively a commitment to protect the Water Forest surrounding the mountains of the megalopolis. Indigenous communities are caring for these mostly oak and pine forests, grassland, and rain-fed agricultural plots, which are used for subsistence crops. The National Protected Areas (NPA), established on the surrounding volcanoes, represent the crucial natural resources and grant especially the water supply to the MCM. Jaramillo [

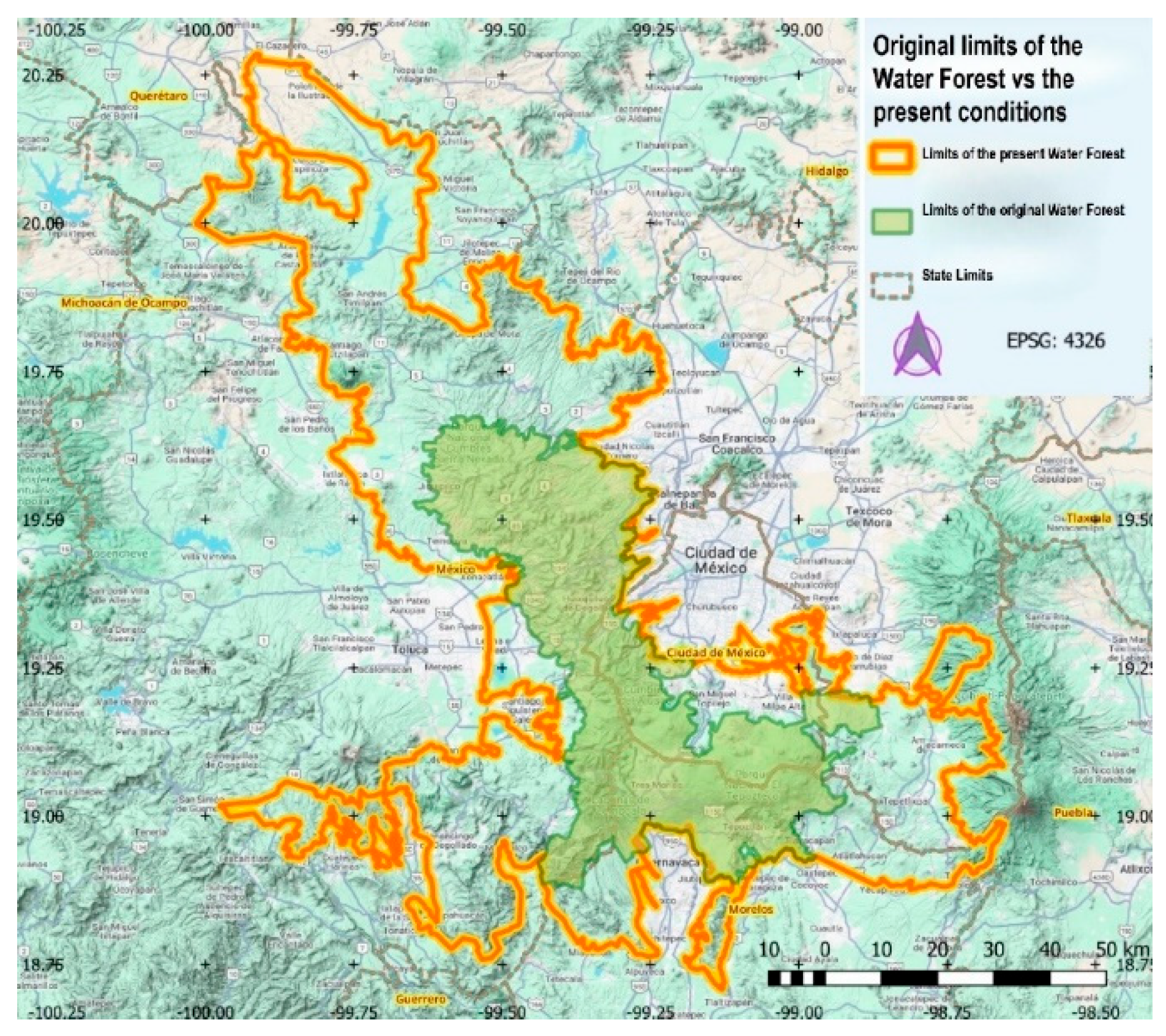

5] called these 807,060 hectares SANBA (System of Natural Protected Areas, Biological and Hydrological Corridors), while people name it Water Forest. Logging trees between 2009 (white area) and the remaining SANBA in 2024 (

Figure 4), designed in red, indicate the fragility of this forest, where human activities, bushfires, plagues, urban expansion, and illegal logging have reduced the primary forest area by 14.3% during the last 26 years.

This SANBA still contains 19 biological and hydrological corridors, establishing functional connectivity between the declared 65 National Protected Areas. The main corridor accounts for more than 300 hectares and smaller corridors are integrated in several polygons. Several smaller and fragmented polygons are also composed by ecosystems of grassland, agriculture, and indigenous villages in the mountain region. These areas are crucial for rainfall infiltration into the aquifers and the protection of the urban areas against floods during more extreme climate events.

The largest corridor of the SANBA, called PNA Ajusco-Chichinautzin, is one of the most important zones for infiltration with high permeability in the subsoil. It is crucial for the supply of aquifers in Mexico City and the eastern part of the state of Morelos. The two important indigenous areas in this SANBA (Cuentepec and San Juan Atzingo) are integrated by a system of ravines in the northwest of Morelos [

36], which links its western border with Mexico State. Several additional forest areas in the north are connected with the NPA of the SANBA [

5]. Therefore, the sustainable management of the SANBA, together with the protection of the National Park Sierra Nevada (Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes) in the eastern part is crucial for long-term water infiltration into groundwater [

25] and flood protection in the MCM.

3.12. Indigenous People

Indigenous people in the world represent only 5% of the global population, and they care about 80% of the remaining biodiversity [

77]. For millennia, these Indigenous people have also cared for the Water Forest surrounding the MCM, offering free water supply and flood protection to all urban citizens in the basin. Alternative water management (1, 2, 3, 4) and greater protection of the Water Forest may avoid the threatening prognostic water shortage in the MCM in 2028 [

1]. Training farmers who are living with small subsistence plots of land in the highlands, also requires organic fertilizers, training for sustainable management of agrochemicals, eliminating any toxic compounds, and restoring affected forest areas, which provides an integral management of the SANBA area. Water security is limited for these Indigenous people who protect the Water Forest, because it is costly to deliver safe water to these communities. These regions obtain the highest regional rainfall and rainwater capture with filters for water purification grant them a safe vital liquid. Domestic sewage could be treated with small bio-digesters and aquatic plants adapted to the different altitudes. These communities are also exposed to organized crime, where the government is obliged to improve their security, control the logging of the Water Forest, the kidnapping of family members, and the forced recruitment of youth for illegal activities [

15].

3.13. Participative Research

The participative research includes different social groups caring about the Water Forest. FUNBA (Biological Foundation of the Anahuac) organized during the last 12 years Indigenous communities, women, and farmers who are protecting the natural resources for all citizens in the plain of the MCM and alternative project of management are developed together with collaborative participants. To improve the protection of threatened people a small research group [

2] with CENTROGEO [

35] established a dynamic digital platform, where trained people from the forest integrate their locally recollected data into the platform. Free available satellites give additional support to understand the dynamic of the natural and social processes going on in the Water Forest. They detect initial bushfires, illegal logging, and invasion of protected areas. Within this participative research process, the last year several participants were assassinated, obliging to substitute the face-to-face meetings with collective and sometimes individual Zoom meetings. The participants also detected the involvement of some municipal or communal authorities with groups of the organized crime. These problems obliged the research project to reduce the access of sensible data on the platform only for committed participants, who got a special code for reviewing confidential data.

3.14. Corruption

Corruption inside the National Commission of Water (Conagua) was denounced by multiple organized groups, especially by independent citizen audit, who have worked for years in a democratic water management and have pressured the Congress to public the General Water Law. This Law should grant human rights to everybody and is an obligation after the constitutional change in Art. 4 in 2012, which granted equal access to all Mexicans to water and sewage. However, the elaboration of this Law was blocked for 13 years by the so-called hydrocracy, who got in the meantime unsustainable water concessions for bottled water or real estate on overexploited aquifers [

48]. García [

78] informed about the hacking of the central computer of Conagua in Mexico City together with all the network of the 13 administrative-hydrological regions, which limited access to crucial data for nearly a month, affecting 13,000 workers. He also denounced a fire outbreak on the floor, where multiple illegal water concessions were set on protected areas and overexploited groundwater. During the government of Lopez Obrador (2018-2024), Conagua could not prove their excessive amounts in public works executed during the former presidential administrations. Confronted with this lack of transparency, the government dismissed some employees and is trying to improve transparency. The independent citizen water audit board continue to detect concessions facilitated to purification and real estate firms on overexploited aquifers. There is also a predominance of hydraulic engineers in executive jobs in Conagua, without a sustainability understanding. They continue promoting river transfers, dams, and costly public works that affect the population in rural communities by destroying their ecosystem services capable of providing for them the necessary water [

49].

3.15. Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (SEDUVI)

The Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (SEDUVI) integrated the three directly involved states into the MCM, gave a collective administration with a budget, and promoted a rigorous urban planning [

79]. The key concern is avoiding immigration in national protected areas [80 into water infiltration areas and the destruction of biodiversity. This implies interrelated activities by limiting the expansion of the MCM on natural areas and forests able to recharge the groundwater. SEDUVI orients new immigrants to suburbs with infrastructure and public services by controlling new settlements in risky areas or NPA. The size of the MCM has promoted social inequity in economic development, especially in the suburbs. Agreements among the involved states have promoted legal and regulatory instruments for metropolitan governance and decentralized instruments, where cost-benefit evaluations are developed for high-impact projects. However, there is always a lack of funding and the mechanisms for innovative financing for metropolitan development are still incipient, especially in industrial, service, tourism, housing, and urban recycling projects. Universities and international foundations have supported specific projects, whenever in all these activities a tension exists between the capital and Mexico State, both with important industrial centers and new service demands. Mexico State is not only the most populated entity but also the fastest-growing region in the MCM with high rural-urban immigration.

The rigorous urban planning in water and sewage (ODS 6) [

57] is underfinanced in all involved states. The expansion of the MCM to natural areas is avoiding the natural recharge of groundwater (

Figure 4). SEDUVI is confronted with a costly water supply and a broken sewage system (

Figure 2) limiting safe water infiltration from rainfall to the endorheic basin. The cultural aspect promotes policies of urban greening [

11], where bio-digesters in housing complexes and neighborhoods are able to clean up grey and domestic sewage for reuse in gardens, parks, and infiltration to the subsoil [81. This aspect is still underestimated by the mentality of engineering planning, promoting expensive and unsustainable public works. This mentality exists also in multiple ministries at federal and state levels, limiting efficient mitigation and adaptation to climate change threats.

3.16. Systemic, Complex and Interrelated Activities

These systemic, complex, and interrelated activities of climate risks, care of forests, safe water supply, and infiltration of rainwater and treated domestic sewage into overexploited aquifers of the MCM could improve the livelihood and well-being of the 32 million inhabitants. They are also creating greater equity among marginal neighborhoods and poor colonies. All governments are still hesitant to involve social participation in the planning and integrated urban development, especially in the fast-growing marginal colonies. Mexico City started in 2023 with a 3% participative budget for every municipality and an equal amount for all colonies, with the proposal to increase it to 4% [

82]. This participative budget is too limited, does not distinguish among the number in each municipality and colony, and limits therefore local unleashing of innovative planning processes.

The process of democratization is advancing slowly and often the municipal government is limiting the involvement of their citizens due to interests of involved political parties, the existing insecurity, and how to proceed with rising demands with a limited budget. Precisely, in the water and forest sectors, the active participative involvement of citizens is the sole way to promote housing complexes and colonies to capture rainfall or building a safe personal drainage system with aquatic plants. These activities not only clean the domestic sewage locally but promote a greener environment. In the forest areas, the integrated management of the SANBA together with the payment of ecosystem services for the involved Indigenous groups may save the highly exposed Water Forest. Responsible security ministries must combat organized crime and impede the involvement of communities, interested people, and local authorities in illegal activities.

4. Discussion

Water security is at stake [

40] with intertwined problems where only complex solutions can overcome the historical destruction of natural resources and the failed engineering technologies, producing polluted water, and air, with uncertainty for safe water supply the next decade [

1] and improved sewage (ODS 6.2). All these processes are interrelated with other SDG [

53]. The megalopolis is the second most populated urban area behind Tokyo [

22]. An open, dissipative, and self-organizing system [

61], integrating the four interrelated subsystems (socio-cultural, urban-productive, environmental, and climate change), explores sixteen integrated solutions with the participation of different stakeholders and the government at the three levels [

66]. The proposal includes natural-based solutions [

38] with the protection of the remaining 807,000 ha of the Water Forest [

5] surrounding the megacity, recycling solid waste, separating rainfall from sewage, and recovering aquifers. By recycling toxic industrial sewage inside their enterprises, infiltrating rainwater and treated domestic sewage into groundwater, the subsidence can get reduced inside the endorheic basin. At the individual level, rainfall is recollected in buildings and offices, greywater is reused in gardens and parks, greening urban areas reduces the temperature increase, promoting an integrated management of all water resources inside the endorheic basin of the MCM [

48]. Only this sustainable use and water treatment can improve the human rights with equity in the water distribution, guaranteed in Art. 4 of the Constitution in February 2012, where Congress never elaborated the General Law on Water Rights.

Continuing with the unsustainable, excessively costly, and polluting water and sewage model [

83], the lack of clean water and floods with toxic sewage among marginal colonies may produce growing threats with the increase of temperature, greater droughts, and hydrometeorological disasters [

84]. Conflicts have emerged in the whole MCM, and women were sexually harassed in 2024 by water pipe distributors of free drinking water, when the supply in poor colonies was missing [

85] , while women only were caring about the wellbeing of their families.

The proposal implies a radical change away from the present costly, corrupt, and polluting engineered system, serving limited economic interests [

86]. On the contrary, the exposed model starts by understanding the entire water cycle. Water security includes the existing pressures related to the use of safe water, the overexploitation of aquifers, the chaotic urbanization, and missing financial resources for reparation and combatting extreme hydrometeorological events. This approach understands the limits of the existing resources coming from precipitation, aquifers, lakes, dams, wetlands, rivers, forests, soils, and treated sewage. It forces the coordination among the threatened states in the MCM, where the three female governors of Mexico City, the State of Mexico, and Morelos signed a political agreement on water forest protection in January 2025. These leaders promote a peaceful and equal water distribution for ecosystem conservation, domestic, service, agricultural, industrial, energy, transportation, and recreational uses [

87].

This complexity is permanently challenged by climate threats and new demands for life quality improvement., It includes social aspirations, reduction of poverty, health reasons, well-being, security, income, work, and leisure. Society, government, and business communities are obliged to establish a negotiated fragile and dynamic equilibrium among the interrelated requirements for safe water and improved sewage, including the environment, people, urbanization, food, health, hygiene, economy, investments, tariffs, technology, and climate risks [

43]. The past expensive and unsustainable technological solutions have produced greater inequity in water access, destroyed urban infrastructure, increased disasters in dried-out lakes, severe health problems, and human-induced disasters by expulsing untreated sewage out of an endorheic basin in the MCM. An integrated system approach indicates that the megalopolis is approaching dangerous tipping points [

10], where only drastic changes and integrated solutions include the protection of the SANBA. The separation and recollection of rain, when infiltrated into groundwater, may provide long-term safe water to the populated megacity also threatened by climate change impacts. The treatment and recycling of domestic sewage inside the MCM with slow recharge may help to recover the overexploited aquifers. Past engineering understanding of water supply and expulsion of sewage are related to powerful economic interests in the water sector and further delays may collapse the damaged system. Therefore, organized women, Indigenous communities, and concerned citizens with academic support [

34] are offering natural [

38], technological [

4], and financially sustainable solutions [

88] to the government to provide long-term safe water supply by infiltrating rainfall and recycling treated domestic sewage inside the MCM by recovering the overexploited aquifers [

89].

Multiple obstacles exist for this drastic change in the sewage policy and the Water Forest option. The entire water system in Mexico and not only in the MCM, suffered for decades by inefficient management, lack of transparency in public work, and missing tariffs that stimulate water-saving practices and recycling practices. Multiple social stakeholders, economic interests, organized women, and also Indigenous communities in the forest have lost confidence in the former authorities, due to deceptions produced by the past five decades of corrupt governments, without legal control of the irrational expansion of the megacity often on the destruction of the Water Forest. They understood the catastrophic water management, promoted as the sole feasible solution. New authorities have to recover this lost confidence [

90].

Growing pressure among more than 32 million water users obliges government and consolidated interests to forget the history of the failed 4 centuries of colonial and neoliberal hydraulic water policy [

91], creating an expensive-destructive water policy [

49], corruption in Conagua [

92], and interested financial sectors to maintain the broken unsustainable system in the Patriacene [

70] by eliminating women from the decision-making processes [

93]. However, climate change threats with growing droughts and empty reservoirs pressure to develop a radical change in the long-delayed alternatives and promoting an integrated water cycle management [

94]. They include multiple interrelated processes proposed in the sixteen integrated-sustainable water proposals, whenever the lack of trust, low citizen participation, limited public budgets, and complex dilemmas inside the MCM [

90] have delayed a policy for a long-term safe water supply. This water management includes locally treated sewage, recovery of aquifers, harvesting rainwater, and Water Forest management. The SANBA approach promotes a sustainable use of the forests surrounding the MCM [

38] and an integrated water cycle management with forest protection in the megacity [

95].

Priorities are linked to water security [

40] for everybody, safe drinking water [

96], supply standards of drinking water and sewage [

4], maintenance of natural flows [

97], greening urban areas [

11], sustainable wastewater management with safe reuse [

98], conservation and recovery of aquifers [

81], legal changes towards water supply and sewage. It promotes equal human rights for everybody, women as key actors for saving, reusing and recycling water [

9], Indigenous community protecting the Water Forest [

77], right to safe water, especially for women [

99], citizen participation in water management [

83], creation of suitable infrastructure [

56], cost optimization [

88], limitation of subsidence [

6], elimination of illegal water concession [

91], safe food production [

59], climate change mitigation and adaptation [

100], sustainable water management of the megacity [

22], and transparency with citizen audit to control water authorities [

92].

Time is pressuring and policy must orient towards sustainable water management with human rights, granting long-term stable and healthy water and integrated sewage management (ODS 16) for a numerous and growing population [

79].