Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

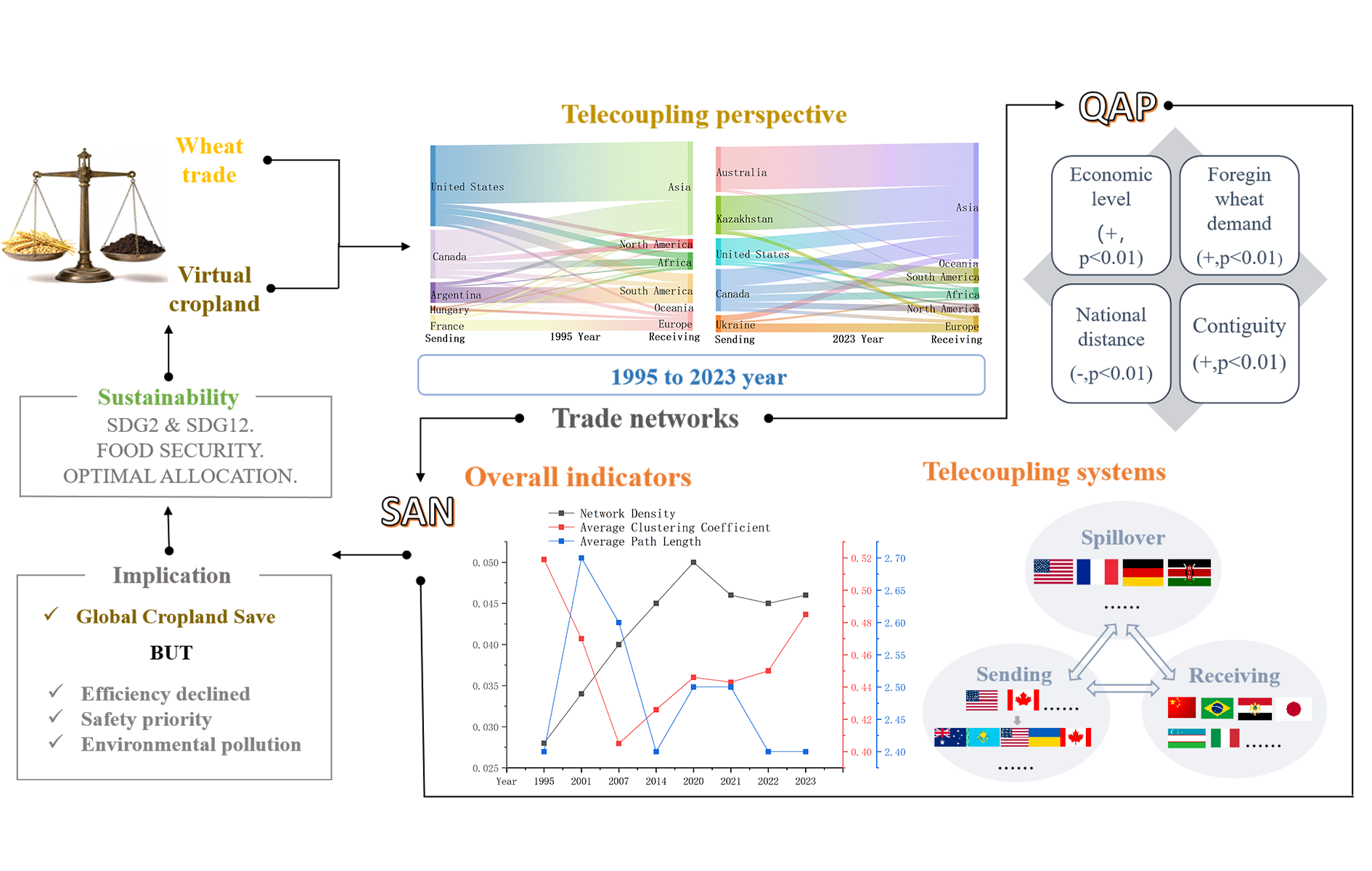

1. Introduction

2. Data Sources and Methods

2.1. Data on Wheat Trade and the Calculation of Virtual Cropland

2.2. Social Network Analysis

2.3. QAP Regression Analysis

2.3.1. Selection of Variables

2.3.2. Model Specification

3. Results

3.1. Overall Network Evolution Characteristics

3.2. Evolutionary Characteristics of Individual Structure

3.3. Drivers of Evolution in the Virtual Cropland Trade Network

3.4. Telecoupling Implications of Virtual Cropland Trade Embodied in Global Wheat Trade

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- The global virtual cropland network embodied in wheat trade shows vulnerability amid increasing connectivity. Although network density generally trends upward, the average clustering coefficient and average path length fluctuate over time. Subject to external shocks, the network structure reveals complex evolutionary characteristics, marked by the coexistence of regional clustering tendencies and improvements in trade efficiency.

- (2)

- The telecoupling structure of the global virtual cropland trade network is distinct. The sending system has transitioned from a duopoly dominated by the United States and Canada to a multipolar export structure involving Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan, and the United States. The receiving system primarily comprises developing countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, with China as the core inflow country. The intermediary power of spillover systems is closely linked to their transnational agribusiness corporations. The intermediary model represented by France—embedded within regional institutional networks—demonstrates stronger coupling and coordination capabilities than the U.S.-led global direct-connection model. Furthermore, under external shocks, specific critical nodes, such as Kenya, can rapidly emerge as new secondary hubs.

- (3)

- Demand and distance factors are fundamental drivers of network evolution, while supply factors exhibit non-stationary characteristics. Facilitating factors align with theoretical expectations but have a limited overall impact. The level of economic development and foreign demand significantly promote both the establishment and intensification of trade relationships. Distance has a dual nature: it serves as a fundamental friction hindering trade connections, yet can be overcome by high complementarity between countries under specific conditions. Geographical distance remains a primary constraint on trade linkages, particularly in the initial establishment of trade relations. Although contiguity has a significant positive effect, its role is primarily manifested in lowering the threshold for forming trade relationships.

- (4)

- While international wheat trade enhances the efficient use of global arable land resources, it is currently grappling with multiple disruptions and striving to find a new equilibrium between efficiency and security. External factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, along with policy and production changes in various countries, have shifted the global virtual arable land trade network from being efficiency-driven to security-focused. For example, Egypt quickly redirected its wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine to the United States and Canada, replacing previously efficient trade routes based on geographic proximity with new, more secure but less efficient supply chains. This transition essentially sacrifices efficiency for supply chain stability, resulting in an overall decline in resource allocation efficiency. Consequently, it is crucial to promote the development of a new framework for grain trade that balances efficiency and security, transcending the management perspectives of individual nations or sectors, to achieve the sustainable and optimized use of global arable land resources.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNA | Social Network Analysis |

| QAP | Quadratic Assignment Procedure |

References

- Ellis, E.C.; Ramankutty, N. Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.2008,6,439-447.

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of mankind. Nature.2002,415,23.

- Lewis, S.L.; Maslin, M.A. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature.2015,519,171-180.

- Tan, M.H.; Li, X.B. Paradigm transformation in the study of man-land relations: From local thinking to global network thinking modes. Acta Geographica Sinica.2021,76,2333-2342.

- Liu, J.G.; Hull, V.; Batistella, M.; DeFries, R.; Dietz, T.;Fu, F.; Hertel, T.W.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Lambin, E.F.; Li, S.X.; Martinelli, L.A.; McConnell, W.J.; Moran, E.F.; Naylor, R.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Polenske, K.R.; Reenberg, A.; Rocha, G.D.; Simmons, C.S.; Verburg, P.H.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S.; Zhu, C.Q. Framing Sustainability in a Telecoupled World. Ecology and Society.2013,18.

- Liu, J.G.; Hull, V.; Batistella, M.; DeFries, R.; Dietz, T.; Fu, F.; W. Hertel, T.; Izaurralde, R.C.; F. Lambin, E.; Li, S.X.; A. Martinelli, L.; J. McConnell, W.; F. Moran, E.; Naylor, R.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; R. Polenske, K.; Reenberg, A.; Rocha, G.d.M.;S. Simmons, C.; H. Verburg, P.; M. Vitousek, P.; Zhang, F.S.; Zhu, C.Q. A Framework for Sustainability in a Telecoupled World. Acta Ecologica Sinica.2016,36,7870-7885.

- Ma, E.P.; Cai, J.M.; Han, Y.; Liao, L.W.; Lin, J. Research progress and prospect of telecoupling of Human-Earth system. Progress in Geography.2020,39,310-326.

- Sun, J.; Liu, J.G.; Yang, X.J.; Zhao, F.Q.; Qin, Y.C.; Yao, Y.Y.; Wang, F.; Lun, F.; Wang, J.J.; Qin, B.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C.L.; Huang, B.R.; Cheng, Y.Q.; Shi, J., L.; Zhang, J.S.; Tang, H.J.; Yang, P.; Wu, W.B. Sustainability in the Anthropocene: Telecoupling framework and its applications. Acta Geographica Sinica.2020,75,2408-2416.

- Ma, E.P.; Cai, J.M.; Guo, H.; Lin, J.; Liao, L.W.; Han, Y. A Theoretical Framework and Research Priorities for Food System Coupling under Urbanization. Acta Geographica Sinica.2021,76,2343-2359.

- Herzberger, A.; Chung, M.G.; Kapsar, K.; Frank, K.A.; Liu, J. Telecoupled Food Trade Affects Pericoupled Trade and Intracoupled Production. Sustainability.2019,11.

- Ye, W.Y.; MA, E.P.; Liao, L.W.; Yu, Z.S. Spatio-temporal evolution and influencing factors of international soybean trade network from a telecoupling perspective. Journal of Natural Resources.2023,38,1632-1650.

- Sondergaard, N.; Thives, V.; de Jesus, C.L.G.; de Campos, I.P.V. Fragmented sustainability governance of telecoupled flows: Brazilian beef exports to China. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management.2024,67,454-476.

- Liu, D.H.; Tian, B.X.; Zhang, M.Q.; Jiang, L.N.; Li, C.X.; Qin, X.L.; Ma, J.H. Meta-analysis of the effects of different tillage methods on wheat yields under various conditions in China. Soil & Tillage Research.2025,248.

- Wang, J.Y.; Dai, C.; Zhou, M.Z.; LIU, Z.J. Research on global grain trade network pattern and its influencing factors. Journal of Natural Resources.2021,36,1545-1556.

- Qiang, W.L.; Zhang, C.L.; Liu, A.M.; Cheng, S.K.; Wang, X. Li, F. Evolution of global virtual land flow related to agricultural trade and driving factors. Resources Science.2020,42,1704-1714.

- Fair, K.R.; Bauch, C.T. Anand, M. Dynamics of the Global Wheat Trade Network and Resilience to Shocks. Scientific Reports.2017,7.

- Gutiérrez-Moya, E.; Adenso-Díaz, B. Lozano, S. Analysis and vulnerability of the international wheat trade network. Food Security.2021,13,113-128.

- Vishwakarma, S.; Zhang, X.; Lyubchich, V. Wheat trade tends to happen between countries with contrasting extreme weather stress and synchronous yield variation. Communications Earth & Environment.2022,3.

- Li, S.J. Review of the Global Wheat Market in 2022/2023 and Outlook for the 2023/2024 Crop Year. China Grain Economy.2023,65-69.

- Guo, H.; Dilinaer, A. A Study on the Influencing Factors and Countermeasures of Wheat Trade between China and Russia. Eurasian Economic Review.2023,96-124+126.

- Wang, R.H. The Structure and Evolution of International Wheat Trade: A Complex Network Analysis. Agricultural Economy.2024,136-138.

- Li, H.R.; Mu, Y.Y. Wheat Import Trade Pattern and Its Influencing Factors in China: Based on the Trade Gravity Model. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin.2020,36,132-139.

- Cheng, Y.J.; Gong, G.Y. Evolution and Influencing Factors of Wheat Trade Network Between China and Countries Along the Belt and Road. Journal of Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences (Social Sciences Edition).2024,43,73-86.

- MA, E.P.; Cai, J.M.; Lin, J.; Han, Y.; Liao, L.W.; Han, W. Explanation of land use/cover change from the perspective of tele-coupling. Acta Geographica Sinica.2019,74,421-431.

- Wu, H.F.; Liu, A.; Jin, R.C.; Chai, L. Interregional flows of virtual cropland within China. Environmental Research Communications.2022,4.

- Meng, H.; Xing, L.W.; Hu, J.X.; Shen, C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wu, J.Z. Exploring the characteristics and drivers of virtual cropland trade of major agricultural products in China. Journal of Cleaner Production.2024,448.

- Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Ji, H. Virtual Land and Water Flows and Driving Factors Related to Livestock Products Trade in China. Land.2023,12.

- Luo, L.; Xing, Z.; Chu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Virtual land trade and associated risks to food security in China. Environmental Impact Assessment Review.2024,106.

- Liu, X.; Yu, L.; Cai, W.; Ding, Q.; Hu, W.; Peng, D.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, X.; Yu, C. Gong, P. The land footprint of the global food trade: Perspectives from a case study of soybeans. Land Use Policy.2021,111.

- Park, S.; Munroe, D.K.; Xiao, N. Visualizing economic drivers of virtual land trade: A case study of global cereals trade. Environment and Planning B-Urban Analytics and City Science.2023,50,1695-1698.

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, N.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. Global virtual-land flow and saving through international cereal trade. Journal of Geographical Sciences.2016,26,619-639.

- Qiang, W.; Niu, S.; Liu, A.; Kastner, T.; Bie, Q.; Wang, X.; Cheng, S. Trends in global virtual land trade in relation to agricultural products. Land Use Policy.2020,92.

- Gao, P.; Gao, Y.; Ou, Y.; McJeon, H.; Iyer, G.; Ye, S.; Yang, X.; Song, C. Heterogeneous pressure on croplands from land-based strategies to meet the 1.5 °C target. Nature Climate Change.2025,15.

- Qiang, W.; Liu, A.; Cheng, S.; Kastner, T.; Xie, G. Agricultural trade and virtual land use: The case of China's crop trade. Land Use Policy.2013,33,141-150.

- Qiang, W.L.; Liu, A.M.; Cheng, S.K.; Xie, G.D.; Zhao, M.Y. Quantification of Virtual Land Resources in China's Crop Trade. Journal of Natural Resources.2013,28,1289-1297.

- Xavier, D.L.D.; dos Reis, J.G.M.; Ivale, A.H.; Duarte, A.C.; Rodrigues, G.S.; de Souza, J.S.; Correia, P.F.D. Agricultural International Trade by Brazilian Ports: A Study Using Social Network Analysis. Agriculture-Basel.2023,13.

- Pan, Z.; Ma, L.; Tian, P.; Zhu, Y. Structural characteristics and influencing factors of agricultural trade spatial network: evidence from RCEP 15 countries. Ciencia Rural.2024,54.

- Alhussam, M.I.; Ren, J.; Yao, H.; Abu Risha, O. Food Trade Network and Food Security: From the Perspective of Belt and Road Initiative. Agriculture-Basel.2023,13.

- Karg, H.; Bellwood-Howard, I.; Ramankutty, N. How cities source their food: spatial interactions in West African urban food supply. Food Security.2025,17,439-460.

- Ma, S.Z.; Ren, W.W.; Wu, G.J. The characteristics of a country's agricultural trade network and its impact on the global value chain division: A perspective from social network analysis. Management World.2016,60-72.

- Bai, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Evolution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Global Dairy Trade. Sustainability.2023,15,.

- Long, F.J.; Zheng, L.F.; Song, Z.D. High-speed rail and urban expansion: An empirical study using a time series of nighttime light satellite data in China. Journal of Transport Geography.2018,72,106-118.

- Duan, J.; Nie, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, D.; Xiong, W. Research on Global Grain Trade Network Pattern and Its Driving Factors. Sustainability.2022,14.

- Deng, G.; Di, K. A Study on the Characteristics and Influencing Factors of the Global Grain Virtual Water Trade Network. Water.2025,17.

- Jia, N.; Xia, Z.L.; Li, Y.S.; Yu, X.; Wu, X.T.; Li, Y.J.; Su, R.F.; Wang, M.T.; Chen, R.S.; Liu, J.G. The Russia-Ukraine war reduced food production and exports with a disparate geographical impact worldwide. Communications Earth & Environment.2024,5.

- Yin, Z.Q.; Wu, J.Z.; Sun, J.; Ding, J.J.; Zhou, X.Y.; Cao, S.S.; Shen, C. Pattern and Evolution Analysis of World Wheat Trade. Food and Nutrition in China.2021,27,48-51.

| Indicator name | Indicator description | Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Network density (D) | The ratio of the actual number of trade connections in the network to the maximum possible number of connections. It measures the overall connectivity of a network. A higher density indicates more connections between nodes, reflecting more frequent trade interactions between countries. |

: number of actual trade links. : total number of nodes. |

| Average clustering coefficient (C) | The average clustering coefficient of all nodes in the network. The clustering coefficient of a node is defined as the ratio of the actual number of links between its neighbors to the maximum possible number of links. This reflects the extent to which neighboring nodes are clustered together. |

: number of neighbors of node . : number of actual links between the neighbors of node . |

| Average path length (L) | The average number of edges along the shortest paths for all possible pairs of nodes in the network. It indicates the efficiency of the connectivity between the nodes. |

: distance (shortest path length) between node and node . |

| Indicator name | Indicator description | Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Relative degree centrality () | The number of nodes directly connected to a given node in the network. A higher value indicates a stronger ability of the node to form connections and a more central position in the network. |

: absolute degree centrality of node . |

| Relative closeness centrality () | Reflects how close a node is to all other nodes in the network and its ability to avoid being controlled by others. A higher value indicates greater independence and efficiency in reaching the other nodes. |

:distance (shortest path length) between node and node . |

| Betweenness centrality () | The proportion of all shortest paths between pairs of nodes in the network that pass through a given node. It reflects the role of the node as a bridge or intermediary in the network. |

: total number of shortest paths between node and node . :number of the shortest paths that pass through node . |

| Criterion layer | Element layer | Variables name | Variables description | Matrix processing | Expected effect | Data source |

| Complementarity | Demand factors | Economic level (G) | Gross domestic product | Difference matrix | + | World Bank database |

| Foreign wheat demand (N) | Wheat self-sufficiency rate | Difference matrix | + | FAO database | ||

| Consumption structure (S) | Total domestic wheat demand/ Total domestic population | Difference matrix | + | World Bank database | ||

| Supply factors | Wheat planting area (A) | Percentage of wheat harvested area to total arable land | Difference matrix | + | FAO database | |

| Wheat yield (O) | Difference in yield per unit area | Difference matrix | + | FAO database | ||

| Renewable freshwater (F) | Per capita available productive inland freshwater resources | Difference matrix | + | World Bank database | ||

| Accessibility | Distance factors | National distance (D) | Spherical distance between national capitals | Multi-value matrix | - | CEPII database |

| Contiguity (C) | Whether territories are adjacent | Binary matrix | + | CEPII database | ||

| Convenience factors | Governance level (P) | Worldwide governance indicators | Difference matrix | - | World Bank database | |

| WTO membership (W) | Whether both are WTO members | Binary matrix | + | WTO official website |

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1995 | Out | U.S. | Canada | Argentina | France | Hungary | Czech Republic | Germany | U.K. | India | Romania |

| Input | China | Brazil | Egypt | Japan | Italy | Algeria | Pakistan | Belgium | South Korea | U.S. | |

| 2001 | Out | U.S. | Canada | Australia | Kazakhstan | France | Germany | Russia | India | Spain | U.K. |

| Input | Iran | Japan | Brazil | Egypt | Italy | Indonesia | Mexico | Philippines | China | Russia | |

| 2007 | Out | U.S. | Canada | Australia | Russia | Kazakhstan | France | India | Germany | Romania | Argentina |

| Input | Egypt | Japan | Indonesia | Brazil | Italy | South Korea | India | Mexico | Yemen | Turkey | |

| 2014 | Out | Australia | Russia | U.S. | Canada | Kazakhstan | France | India | Germany | Romania | Argentina |

| Input | Indonesia | Egypt | Iran | Turkey | Japan | Brazil | Italy | Nigeria | China | Mexico | |

| 2020 | Out | Russia | Australia | U.S. | Canada | Ukraine | Kazakhstan | Egypt | Argentina | France | Romania |

| Input | China | Egypt | Indonesia | Turkey | Philippines | Uzbekistan | Italy | Japan | Brazil | Bangladesh | |

| 2023 | Out | Australia | Canada | Kazakhstan | U.S. | Ukraine | Romania | France | Argentina | Brazil | Bulgaria |

| Input | China | Uzbekistan | Indonesia | Italy | Philippines | Spain | Mexico | Brazil | Morocco | Thailand |

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1995 | U.S. 7.930 |

France 4.559 |

Germany 4.271 |

Netherlands 2.409 |

U.K. 2.025 |

Italy 1.688 |

Spain 1.657 |

Belgium 1.083 |

Denmark 0.877 |

Canada 0.874 |

| 2001 | U.S. 8.392 |

France 6.162 |

Germany 4.740 |

Canada 4.185 |

Argentina 3.940 |

Australia 3.565 |

U.K. 3.063 |

Russia 2.711 |

Japan 2.612 |

Turkey 2.604 |

| 2007 | U.S. 11.072 |

France 7.573 |

Germany 4.396 |

Italy 4.235 |

Russia 4.119 |

Ukraine 3.120 |

U.K. 2.863 |

Canada 2.822 |

China 1.902 |

Australia 1.876 |

| 2014 | U.S. 8.117 |

France 4.484 |

Germany 4.400 |

Canada 4.369 |

U.K. 3.244 |

Italy 2.925 |

India 2.301 |

Russia 2.087 |

South Africa 1.495 |

China 1.256 |

| 2020 | U.S. 8.376 |

France 6.552 |

Germany 4.768 |

U.K. 3.896 |

Kenya 3.416 |

South Africa 3.201 |

Canada 3.016 |

Russia 2.950 |

Uganda 2.456 |

Italy 2.139 |

| 2023 | France 5.511 |

Kenya 3.869 |

U.S. 3.811 |

France 3.484 |

U.K. 3.191 |

Canada 2.026 |

South Africa 1.914 |

Brazil 1.891 |

Australia 1.719 |

Tanzania 1.567 |

| Variable | 1995 Year | 2001 Year | 2007 Year | 2014 Year | 2020 Year | 2023 Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demand factors | G | 0.2664*** (0.001) |

0.2324*** (0.001) |

0.2132*** (0.001) |

0.1936*** (0.001) |

0.1726*** (0.001) |

0.1749*** (0.001) |

| N | 0.1582*** (0.001) |

0.2663*** (0.001) |

0.2054*** (0.001) |

0.2471*** (0.001) |

0.2234*** (0.001) |

0.1760*** (0.001) |

|

| S | 0.0901*** (0.009) |

0.0251 (0.199) |

0.0947*** (0.007) |

0.0246 (0.208) |

0.0591** (0.048) |

0.0909*** (0.007) |

|

| Supply factors | A | -0.0905*** (0.001) |

-0.0580*** (0.005) |

-0.0332* (0.074) |

-0.0845*** (0.001) |

-0.0873*** (0.001) |

-0.0644** (0.011) |

| O | 0.0724** (0.012) |

0.0764*** (0.002) |

0.0491** (0.027) |

0.0664** (0.022) |

0.0164 (0.266) |

0.0150 (0.3133) |

|

| F | 0.0746** (0.033) |

0.0358 (0.147) |

0.0224 (0.214) |

0.0653* (0.051) |

0.0971** (0.012) |

0.0777** (0.035) |

|

| Distance factors | D | -0.2105*** (0.001) |

-0.2096*** (0.001) |

-0.2876*** (0.001) |

-0.266*** (0.001) |

-0.2533*** (0.001) |

-0.2422*** (0.001) |

| C | 0.1685*** (0.001) |

0.1891*** (0.001) |

0.1306*** (0.001) |

0.1560*** (0.001) |

0.1626*** (0.001) |

0.1408*** (0.001) |

|

| Convenience factors | P | -0.0606*** (0.005) |

-0.0833*** (0.001) |

-0.0844*** (0.001) |

-0.0905*** (0.001) |

-0.0912*** (0.001) |

-0.0706*** (0.002) |

| W | 0.1076*** (0.002) |

0.0425* (0.077) |

0.0109 (0.393) |

0.0799** (0.013) |

0.0914*** (0.006) |

0.1138*** (0.001) |

|

| R2 | 0.1859 | 0.2105 | 0.2158 | 0.2040 | 0.1948 | 0.1631 | |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1853 | 0.2099 | 0.2152 | 0.2034 | 0.1942 | 0.1625 |

| Variable | 1995 Year | 2001 Year | 2007 Year | 2014 Year | 2020 Year | 2023 Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demand factors | G | 0.1579*** (0.002) |

0.1294*** (0.003) |

0.1796*** (0.001) |

0.1354*** (0.001) |

0.0855** (0.012) |

0.0849** (0.012) |

| N | 0.0644** (0.017) |

0.1992*** (0.001) |

0.1406*** (0.001) |

0.1390*** (0.001) |

0.0762*** (0.008) |

0.0600** (0.018) |

|

| S | 0.0131 (0.205) |

-0.0010 (0.520) |

0.0158 (0.160) |

-0.0013 (0.513) |

0.0323* (0.053) |

0.0300* (0.065) |

|

| Supply factors | A | -0.0219 (0.103) |

-0.0052 (0.360) |

0.0239* (0.071) |

0.0036 (0.396) |

-0.0187 (0.144) |

-0.0040 (0.413) |

| O | -0.0290** (0.039) |

-0.0185 (0.104) |

0.0062 (0.353) |

-0.0257* (0.098) |

-0.0164 (0.169) |

-0.0013 (0.474) |

|

| F | 0.0528** (0.025) |

0.0234* (0.083) |

0.0362** (0.042) |

0.0539** (0.022) |

0.0575** (0.025) |

0.0366* (0.057) |

|

| Distance factors | D | -0.0317** (0.029) |

-0.0331** (0.012) |

-0.0753*** (0.001) |

-0.0688*** (0.001) |

-0.0459*** (0.007) |

-0.0256* (0.073) |

| C | 0.0643*** (0.001) |

0.1084*** (0.001) |

0.0829*** (0.001) |

0.1067*** (0.001) |

0.0906*** (0.001) |

0.1211*** (0.001) |

|

| Convenience factors | P | 0.0047 (0.380) |

-0.0044 (0.401) |

-0.0405*** (0.004) |

-0.0116 (0.255) |

-0.0316** (0.024) |

-0.0010 (0.278) |

| W | 0.0193 (0.141) |

-0.0000 (0.499) |

-0.0326** (0.034) |

0.0032 (0.460) |

0.0200 (0.177) |

0.0082 (0.367) |

|

| R2 | 0.0373 | 0.0747 | 0.0751 | 0.0573 | 0.0282 | 0.0278 | |

| Adj-R2 | 0.0366 | 0.0739 | 0.0744 | 0.0566 | 0.0274 | 0.0271 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).