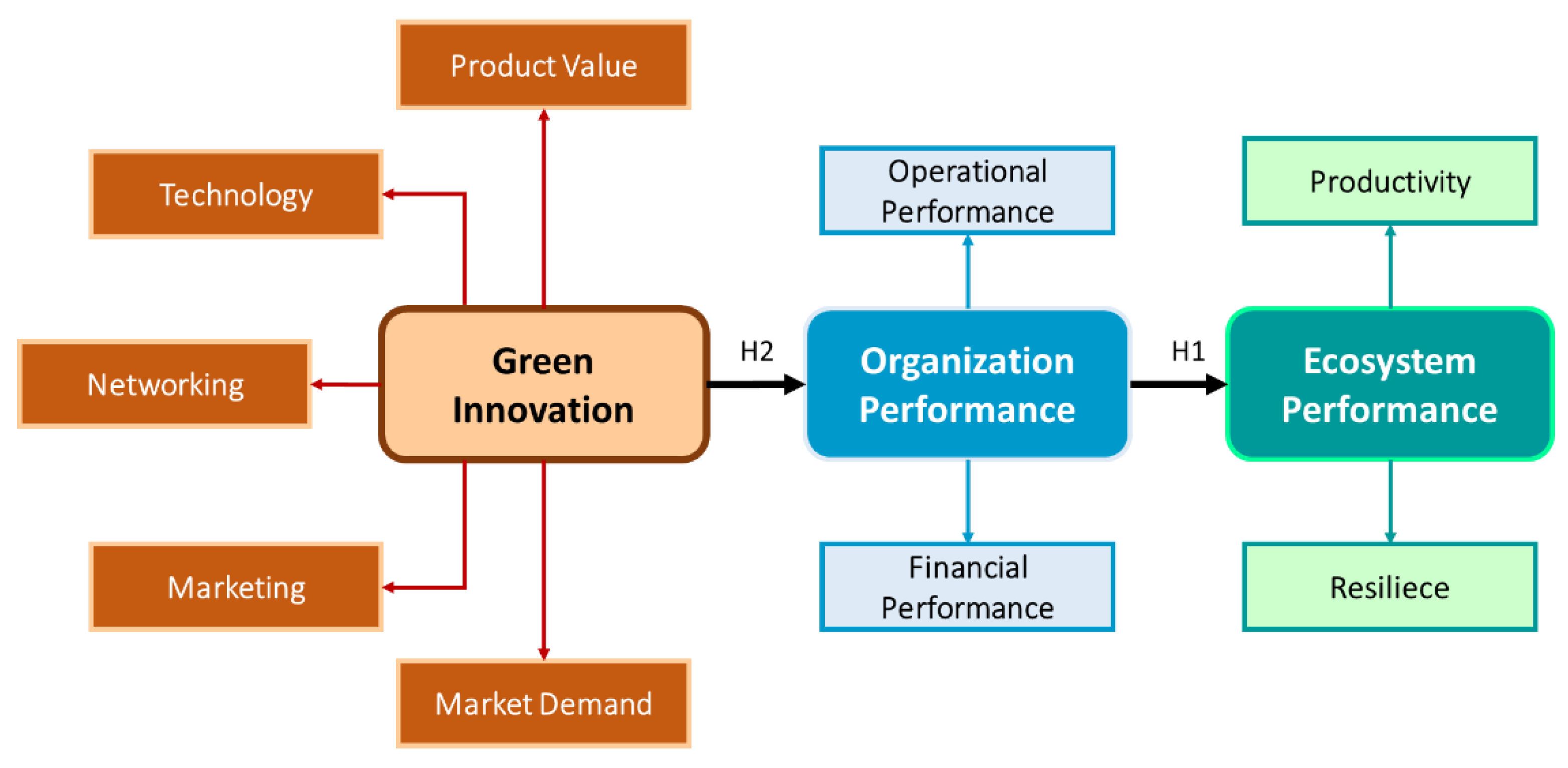

This study explicitly analyzes how Green Innovation (GI), measured through a series of dimensions representing product value, technology, networking, marketing, and market demand, contributes to increased Organizational Performance (OP), which is also measured through financial and operational performance. Furthermore, this study empirically examines how this increased OP impacts Ecosystem Performance (EP), as measured through the productivity and resilience dimensions of the MSME tourism ecosystem in East Sumba Regency. Therefore, the analysis of the results not only examines the relationships between latent variables but also evaluates how strongly each dimension reflects the constructs of GI, OP, and EP.

The Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) method was used because the research model contains latent constructs measured across multiple dimensions and aims to produce a predictive model appropriate to the empirical context of MSMEs in the 3T regions. This method was chosen because it can handle data characteristics commonly encountered in the field, including limited sample sizes, non-normal distributions, and the complexity of constructs with multiple measurement dimensions. Therefore, the research results are presented in two main stages. The first stage is the evaluation of the measurement model, which aims to ensure that all dimensions used are truly valid and reliable in reflecting the latent constructs. In this stage, the GI, OP, and EP dimensions are tested using factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). This evaluation ensures that the dimensions have adequate representation of their parent constructs and meet quality standards in SEM measurement.

The second stage is the evaluation of the structural model, which focuses on testing the causal relationships between GI → OP and OP → EP. This stage analyzes the path coefficient, its significance level, the amount of variance explained by the model (R²), the effect size (f²), and the model’s predictive relevance (Q²). This stage also includes examining VIF values to ensure there is no multicollinearity between dimensions that could compromise the accuracy of structural relationship estimates.

Overall, the evaluation results of the two stages provide a strong empirical picture of how the implementation of GI dimensions, ranging from the use of environmentally friendly technologies, increasing product value, strengthening networks, sustainable marketing strategies, and responding to market needs, contribute to improving the financial and operational performance of MSMEs. Detailed results from the measurement model testing are presented in the next subsection, followed by an analysis of the structural model and an interpretation of the relationships among latent variables based on empirical data.

4.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model evaluation stage is conducted to ensure that each dimension used in the study adequately reflects the latent construct it measures. In the PLS-SEM approach, measurement model testing is performed using several key criteria: dimensional reliability, internal reliability, and convergent validity. Internal reliability is generally evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR). At the same time, convergent validity is assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which indicates the proportion of variance in the indicators explained by the latent construct.

A good measurement model must meet three essential criteria: Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability values above 0.70, indicating strong internal consistency; an AVE value exceeding 0.50, indicating that more than half of the dimensional variance is explained by the latent construct; and the dimensions within each construct have adequate fit to reflect the construct accurately. To assess this,

Table 2 below presents the Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability, and AVE values for all research constructs.

The measurement model test results in

Table 2 indicate that all constructs in this study exhibit excellent reliability and convergent validity, providing a strong measurement basis for the structural model analysis. The EP construct demonstrated very adequate measurement performance, reflected in its high Composite Reliability and AVE values. In this study, the EP is represented by the dimensions of productivity and ecosystem resilience, two aspects highly relevant to the sustainability of tourism MSMEs in East Sumba Regency. The productivity dimension has a CR value of 0.961 and an AVE of 0.632, indicating that these dimensions explain the construct variance stably and consistently. Productivity in this context refers to MSMEs’ ability to maintain efficient production flows, ensure product supply continuity, and optimally increase output amid the dynamics of tourist demand. Meanwhile, the ecosystem resilience dimension has a Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.688, a CR of 0.806, and a very high AVE of 0.793. Although the alpha value is slightly lower, the high AVE indicates that the resilience dimensions still strongly reflect the construct’s variance. This reflects how MSMEs in the 3T regions exhibit varying degrees of adaptation to market changes and environmental pressures. Overall, the resilience dimensions still represent the construct well.

OP, as the second construct, demonstrated strong measurement performance, with a Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.870, a CR of 0.885, and an AVE of 0.852. OP is reflected through two main dimensions: financial performance and operational performance. Financial performance had a high alpha value of 0.951 and an AVE of 0.781, reflecting consistent financing and revenue stability as core components of the MSME finance function. This dimension reflects MSMEs’ ability to increase revenue, maintain profit margins, and efficiently manage cost structures in the tourism sector. Meanwhile, the operational performance dimension had an alpha value of 0.828, a CR of 0.896, and an AVE of 0.707. This dimension reflects the ability of MSMEs to maintain production process efficiency, improve service quality, reduce defect rates, and ensure rapid responsiveness to customer demand. The high reliability and validity values for both OP dimensions reinforce the conclusion that organizational performance in this model is measured very well and stably.

GI, the primary construct in the study, demonstrated strong results, with a Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.818, a CR of 0.856, and an AVE of 0.709. This construct is represented through dimensions that describe various aspects of green innovation, namely product value, technology, networking, marketing, and market demand. The product value dimension has a very high CR of 0.972 and an AVE of 0.865, indicating that respondents’ perceptions of innovation in this dimension are highly consistent. This includes how MSMEs can produce more environmentally friendly products, emphasize the use of natural materials, and enhance aesthetic and cultural values , such as Sumba ikat woven motifs. Technology, as the next dimension, has a CR of 0.860 and a very high AVE of 0.889, indicating that respondents provide stable evaluations of the use of environmentally friendly technology across both the production process and operational digitalization. Networking, or business networks, had a CR value of 0.817 and an AVE of 0.791, reflecting the strong role of collaboration between MSMEs, the government, cultural communities, and the tourism industry in encouraging the adoption of green innovations. The marketing dimension showed a CR value of 0.760 and an AVE of 0.794, illustrating that sustainability-based marketing strategies have become a crucial part of MSMEs’ efforts to adapt to the eco-friendly tourism trend. Finally, market demand performed very well, with a CR value of 0.984 and an AVE of 0.718. These values indicate that MSMEs are aware of the shift in tourist preferences toward more ethical, sustainable, and culturally valuable products and services, thus making the market demand dimension a significant contributor to the formation of the GI construct.

Overall, the pattern of measurement model results indicates that each dimension used to measure GI, OP, and EP has strong internal consistency and high convergent validity. These dimensions are not only statistically stable but also substantively reflect the fundamental dynamics of East Sumba tourism MSMEs. The combination of high AVE values and consistent CRs indicates that the measurement model in this study is in excellent condition and warrants proceeding to the structural analysis stage. Thus, the evaluation of the structural model can be conducted with confidence that the quality of the measurements is not a source of bias and that the causal relationships between the constructs tested in PLS-SEM can truly reflect the empirical phenomena occurring in the field.

4.2. Structural Model

After ensuring that all constructs in the measurement model meet the criteria for reliability and convergent validity, the next step is to assess the risk of multicollinearity among the latent constructs and their dimensions. This test is crucial in PLS-SEM because high multicollinearity can distort path coefficient estimates, increase error variance, and reduce parameter stability, leading to inaccurate structural model results. Therefore, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is used to assess whether there is excessive correlation among interrelated variables in the model. A VIF within the ideal range, which is below 3.0 within the methodological tolerance limit, indicates that each dimension contributes generously to its construct and does not contain measurement redundancy. In the context of this study, VIF testing was conducted not only on the relationship between GI and its dimensions, but also on the relationships between OP and EP and their constituent dimensions, to ensure that the overall model structure has strong measurement stability before conducting structural model analysis.

Table 3 presents the results of the VIF test and shows how each dimension contributes independently to the construct it measures.

The VIF test results in

Table 3 indicate that all relationships between the latent constructs and their dimensions have VIF values of 1.000. This value represents the ideal condition and suggests the absence of multicollinearity in the model. Thus, each dimension forming the GI, OP, and EP constructs provides truly distinctive information without duplicating one another or creating excessive correlation that could distort parameter estimates. The VIF value also reinforces the conclusion that the measurement structure in the model is optimal, allowing the path coefficient estimates at the structural model stage to be interpreted validly and without bias. The absence of multicollinearity is essential to ensuring that causal relationships between constructs, particularly GI → OP and OP → EP, can be analyzed within the theoretical framework without statistical distortion.

Once the measurement model has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity and is free of multicollinearity, the next stage of analysis is to evaluate the structural relationships among the latent constructs in accordance with the established hypotheses. At this stage, the bootstrapping method is used to obtain the path coefficient, T-statistic, and p-value, which collectively describe the strength and significance of the causal relationship in the model. Testing this structural relationship is the core of the PLS-SEM analysis because it determines whether the exogenous constructs truly have a significant influence on the endogenous constructs, as specified by the theoretical basis. In the context of this study, the GI → OP and OP → EP relationships are the two main pathways tested to assess the extent to which GI contributes to increasing OP and how this performance ultimately strengthens the performance of the MSME tourism ecosystem in East Sumba.

Table 4 presents the detailed results of the evaluation of the significance of these two structural relationships.

The results in

Table 4 indicate that both structural relationships in this research model are significant at the 0.01 confidence level. The first pathway, the effect of GI on OP, has a coefficient of 0.894, with a T-statistic of 20.86 and a significance level of 0.008. This high coefficient indicates that GI implementation makes a substantial contribution to improving organizational performance. This means that every improvement in GI dimensions, whether in terms of product value, environmentally friendly technology, business networks, sustainable marketing, or sensitivity to market demand, consistently results in improvements in OP and MSME finances. These results strengthen the theoretical argument that green innovation is a strategic capability that enhances MSME competitiveness in the tourism sector.

Meanwhile, the structural relationship between OP and EP shows an even higher coefficient of 0.985, with a T-statistic of 32.51 and a significance level of 0.005. These findings indicate that organizational performance is a dominant determinant of ecosystem performance. Improved operational efficiency (OP) is reflected not only in the organization’s internal efficiency but also directly impacts the tourism ecosystem’s capacity to become more productive, adaptive, and sustainable. This pathway confirms that the success of individual MSMEs has a systemic impact on the broader tourism ecosystem, in line with the principle that local economic ecosystems thrive through the collective contributions of high-performing business actors.

Overall, the significance of both structural pathways in

Table 4 indicates that the research model has extreme predictive power. GI is proven to play a key role in driving increased OP, and this improved organizational performance then directly contributes to increased EP. In other words, when MSMEs successfully enhance their operational and financial performance, the surrounding tourism ecosystem also becomes more productive and adaptable. This relationship pattern aligns with the Resource-Based View (RBV) framework used in the study. It provides strong empirical evidence of the importance of GI in strengthening MSMEs and building a sustainable tourism ecosystem in 3T regions such as East Sumba.

The following analytical step is to evaluate the model’s predictive power using the coefficient of determination (R²). R² evaluation is essential for assessing the extent to which endogenous variables are explained by exogenous variables in the model. In PLS-SEM, R² values are generally categorized as substantial (≥0.75), moderate (around 0.50), and weak (around 0.25), depending on the complexity of the model and the research context. The higher the R² value, the greater the proportion of the endogenous construct’s variance explained by the constructs that influence it, thereby strengthening the model’s predictive ability. In this research, the R² value is a key metric for understanding the impact of GI on OP and the contribution of OP to EP. Therefore,

Table 5 presents a series of R² and Adjusted R² values for all endogenous constructs in the model, including derived constructs such as the GI, OP, and EP dimensions, to provide a comprehensive picture of the research model’s explanatory power.

The results presented in

Table 5 indicate that this research model has extreme explanatory power for endogenous variables. The highest R² value is for the EP construct, at 0.803, indicating that OP explains 80.3% of the variation in ecosystem performance. This value falls into the substantial category, indicating that improving organizational performance significantly contributes to the productivity and resilience of the MSME tourism ecosystem in East Sumba. In other words, the success of MSMEs in improving operational efficiency and financial stability is directly reflected in the tourism ecosystem’s increased ability to adapt, survive, and maintain the quality of tourism services.

The OP construct has an R² of 0.795, indicating that GI explains 79.5% of the variation in organizational performance. This high value demonstrates that GI is a powerful determinant of OP. This means that MSMEs that consistently implement GI, whether by increasing product value, utilizing technology, strengthening networks, adopting environmentally friendly marketing practices, or responding to market demand, experience significant improvements in both financial and operational aspects. This aligns with the findings in the previous table, which show that GI → OP is a highly substantial structural pathway.

High R² values are also evident across the construct dimensions. For the EP construct, the Productivity (PD) dimension has an R² of 0.749, while the Resilience (RS) dimension has an R² of 0.861. These values indicate that EP has strong explanatory power across its two main dimensions, with RS demonstrating the highest explanatory power. This suggests that improving ecosystem performance is more sensitive to MSME resilience in the face of changes in the business environment.

For the OP construct, the Financial Performance (FP) dimension has an R² of 0.766, and the Operational Performance (OF) dimension has an R² of 0.729. These findings indicate that OP consistently influences both dimensions, reinforcing the understanding that organizational performance is a combination of financial achievement and operational efficiency. For the GI construct, the R² value is 0.630, meaning that the set of GI dimensions explains 63% of the overall variation in the Green Innovation construct. Among the GI dimensions, the highest R² value is found in Market Demand (MD) at 0.894, followed by Networking (NW) at 0.888 and Technology (TC) at 0.843. These values indicate that these three aspects are the strongest components in shaping perceptions of green innovation among MSMEs in East Sumba. Meanwhile, the other dimensions of Product Value (0.768) and Marketing (0.840) also contribute significantly to the formation of GI, indicating that product-based innovation and sustainable marketing strategies are integral parts of green innovation practices. Overall, the R² values in

Table 6 confirm that the constructed model has high predictive ability and is very adequate at explaining the causal relationships between constructs. This model is not only statistically robust but also substantively relevant in describing how green innovation improves organizational performance and ultimately strengthens the tourism ecosystem’s performance in 3T regions, such as East Sumba. Evaluation of the measurement model and structural model shows that the dimensions and constructs are valid and reliable. Visualization of the relationships between constructs in the PLS-SEM model provides a more comprehensive picture of the pattern of relationships among the main variables. This visualization not only illustrates the direction and strength of the relationship between constructs but also shows the magnitude of each dimension’s contribution to its parent construct in the GI, OP, and EP models. Thus, this structural diagram clarifies how green innovation translates into improved organizational performance, and how these improvements resonate at the ecosystem level.

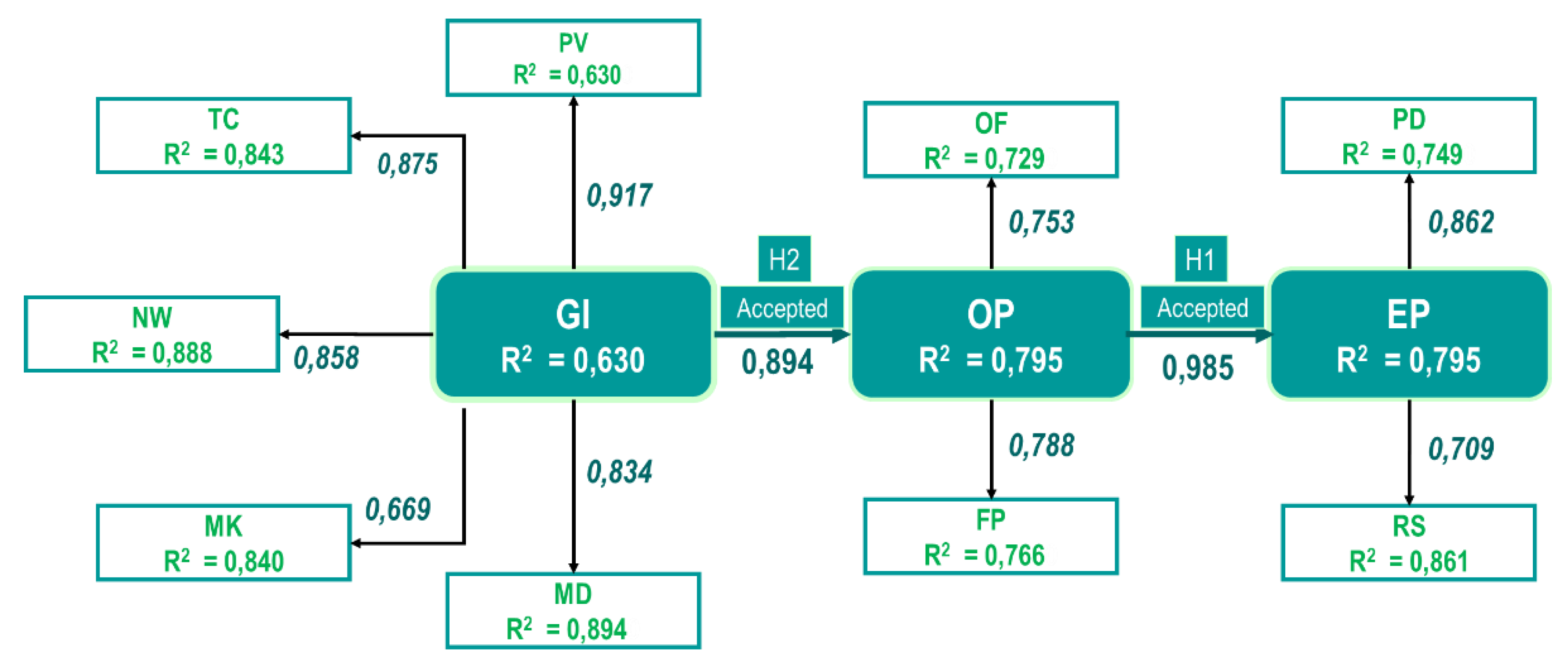

Figure 3 displays the overall structural relationships, including the path coefficients, the R² values for each construct, and the dimension-construct relationships that form the whole research model.

Figure 3 illustrates the structural model’s very high predictive power, as evidenced by substantial path coefficients and R² values. Within the GI construct, all dimensions—Product Value (PV), Technology (TC), Networking (NW), Marketing (MK), and Market Demand (MD)—have strong coefficients, each ranging from 0.66 to 0.91. These values indicate that each dimension consistently contributes to GI. The Market Demand (MD) and Product Value (PV) dimensions are the two most dominant components, suggesting that East Sumba MSMEs are driven not only by product-based innovation but also by responding to the current trend in tourism market demand, which is increasingly ecological and rooted in cultural values.

At the inter-construct level, the GI → OP path shows a coefficient of 0.894, indicating a powerful and significant influence. This confirms that the greater the implementation of green innovation in MSMEs, whether through product updates, the use of environmentally friendly technologies, network strengthening, or sustainable marketing strategies, the higher the organization’s performance, both operationally and financially. The impact of GI on OP is reflected in the R² value of 0.795, indicating that GI can explain 79.5% of the variation in OP. In other words, GI is the primary foundation driving improved performance of MSMEs in the East Sumba tourism sector.

In the next stage, the OP → EP relationship shows a coefficient of 0.985, the highest value in the model. This value indicates that changes in organizational performance resonate almost entirely at the ecosystem level, particularly in terms of productivity and resilience. EP has an R² of 0.803, indicating that OP explains 80.3% of the variation in ecosystem performance. This finding aligns with the argument that more operationally efficient and financially stable MSMEs will be able to consistently make positive contributions to the tourism ecosystem, such as stabilizing the supply of tourism services, community resilience in the face of fluctuating demand, and improving the quality of the tourist experience.

Figure 3 also shows that the EP dimensions, namely Productivity (PD) and Resilience (RS), have measurement coefficients of 0.862 and 0.709, respectively. Productivity emerges as the dominant dimension, underscoring that the success of the tourism ecosystem is primarily reflected in its efficiency in generating economic value and providing tourism services. On the other hand, a high RS value still indicates that the ecosystem’s ability to adapt and survive remains a crucial dimension in the tourism ecosystem of 3T regions, such as East Sumba.

Overall, the relationships between constructs and dimensions depicted in

Figure 3 strengthen empirical evidence that green innovation plays a strategic role in driving improved organizational performance, and that this improvement has a direct impact on the stability and sustainability of the tourism ecosystem. These findings not only support the Resource-Based View (RBV) theoretical framework but also provide essential insights for sustainable tourism development policies in 3T regions.

The influence of one construct on another can occur either directly or through mediation mechanisms. Analysis of direct and indirect effects provides a deeper understanding of the flow of influence patterns in the model, specifically whether the independent variable influences the dependent variable through a mediator or operates directly without an intermediary. In the context of this research, this analysis is essential to determine whether the structure of the relationships between variables follows the theoretical pattern assumed in the Resource-Based View (RBV) framework and green innovation theory.

Table 6 presents the direct and indirect effect estimates for each path tested in the model.

The results in

Table 6 show that the variable OI (which in the original study likely referred to an exogenous variable such as Organizational Innovation or a similar construct) has an indirect effect on ST through OP of 0.616, as well as a direct effect on ST of 0.634. This suggests that OP mediates some of OI’s influence on ST, while others act directly without intermediaries. Furthermore, the path OI → CP → ST shows an indirect effect of 0.614, indicating that the CP variable mediates the relationship. Overall, these results confirm that the influence between variables in the model occurs not only through the central pathway but also through intermediaries, amplifying the complexity of the causal relationship. These findings enhance our understanding of how performance improvement or sustainability processes can occur through multiple trajectories within an organization.

After analyzing the influences between the primary constructs, the next step is to ensure that each endogenous construct is truly represented by its dimension or dimensions. This test is crucial for determining whether the dimensions that form the construct make a significant and consistent contribution.

Table 7 displays the significance of the relationship between Ecosystem Performance (EP) and its two dimensions, namely Productivity (PD) and Resilience (RS).

The results in

Table 7 show that EP is significantly related to both dimensions. The correlation between EP and PD is 0.862, with a t-statistic of 34.357 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating that productivity is a powerful driver of ecosystem performance. Similarly, the correlation between EP and RS is 0.709, with a t-statistic of 32.106 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating that resilience is also an integral part of ecosystem performance. These findings suggest that a strong tourism ecosystem is characterized not only by its ability to produce output consistently but also by its adaptive capacity to withstand environmental dynamics.

The subsequent evaluation assessed how OP is reflected by its two components: Financial Performance (FP) and Operational Performance (OF). These two aspects are important because they indicate how organizational performance is distributed between internal efficiency and financial achievement.

Table 8 presents the significance of these relationships.

The results in

Table 8 show that OP has a highly significant relationship with both FP and OF. The OP → FP relationship shows a correlation of 0.788 with a T-statistic of 33.640, while OP → OF has a correlation of 0.753 with a T-statistic of 32.553. Both relationships have p-values below 0.01, confirming that organizational performance is consistently measured across these two main dimensions. Thus, OP is a stable construct with a strong internal structure that describes the organization’s overall condition.

To ensure that Green Innovation (GI) is fully represented by its constituent dimensions, the relationships between GI and each dimension were tested. This assessment is crucial because GI is a complex construct comprised of five strategic aspects of innovation.

Table 9 presents the results of the significance of these relationships.

The results in

Table 9 indicate that all GI dimensions are significant in explaining the construct. Product Value (PV) has the highest correlation (0.917), followed by Technology (TC = 0.875) and Networking (NW = 0.858). Marketing (MK = 0.669) and Market Demand (MD = 0.734) are also significant, although their contributions are slightly lower. Overall, these results indicate that GI is a robust construct and encompasses various complementary aspects of innovation, from product quality to market dynamics.

To ensure a good fit of the PLS-SEM model, a model fit test was conducted using three dimensions: SRMR, NFI, and RMS Theta. These three dimensions indicate whether the model structure fits the empirical data.

Table 10 displays the results of the model fit test.

Based on

Table 10, the SRMR value of 0.829 is within the acceptable range, while the NFI of 0.961 exceeds the ideal limit of 0.90, indicating a very good level of model fit. The RMS Theta value of 0.006 indicates that the model error is very low, thus the model is considered to have good measurement quality. Overall, all three dimensions indicate that the model structurally fits the data and is suitable for drawing theoretical conclusions.

Effect size (f²) is evaluated to determine the extent to which exogenous constructs contribute to the endogenous constructs in the structural model. This evaluation complements the R² value because it provides information on the strength of each path.

Table 11 presents the results of the f² calculation.

The results in

Table 11 show that GI has an effect size of 0.402 on OP, which is considered significant. Meanwhile, OP has an effect size of 0.369 on EP, also regarded as large. Thus, both main paths in the model are not only significant but also have a substantial impact on explaining the endogenous variables. To assess the model’s predictive ability, a Q² test was conducted using the blindfolding technique. A Q² value greater than zero indicates that the model is predictive.

Table 12 presents the Q² values for the endogenous constructs.

The results in

Table 12 show that Ecosystem Performance (EP) has a Q² value of 0.387, indicating strong predictive ability for this variable. Meanwhile, OP and GI do not have Q² values because they are non-predictor variables in the model. This Q² value confirms that the model not only has good structural fit but also adequately predicts variance in the ecosystem construct.