1. Introduction

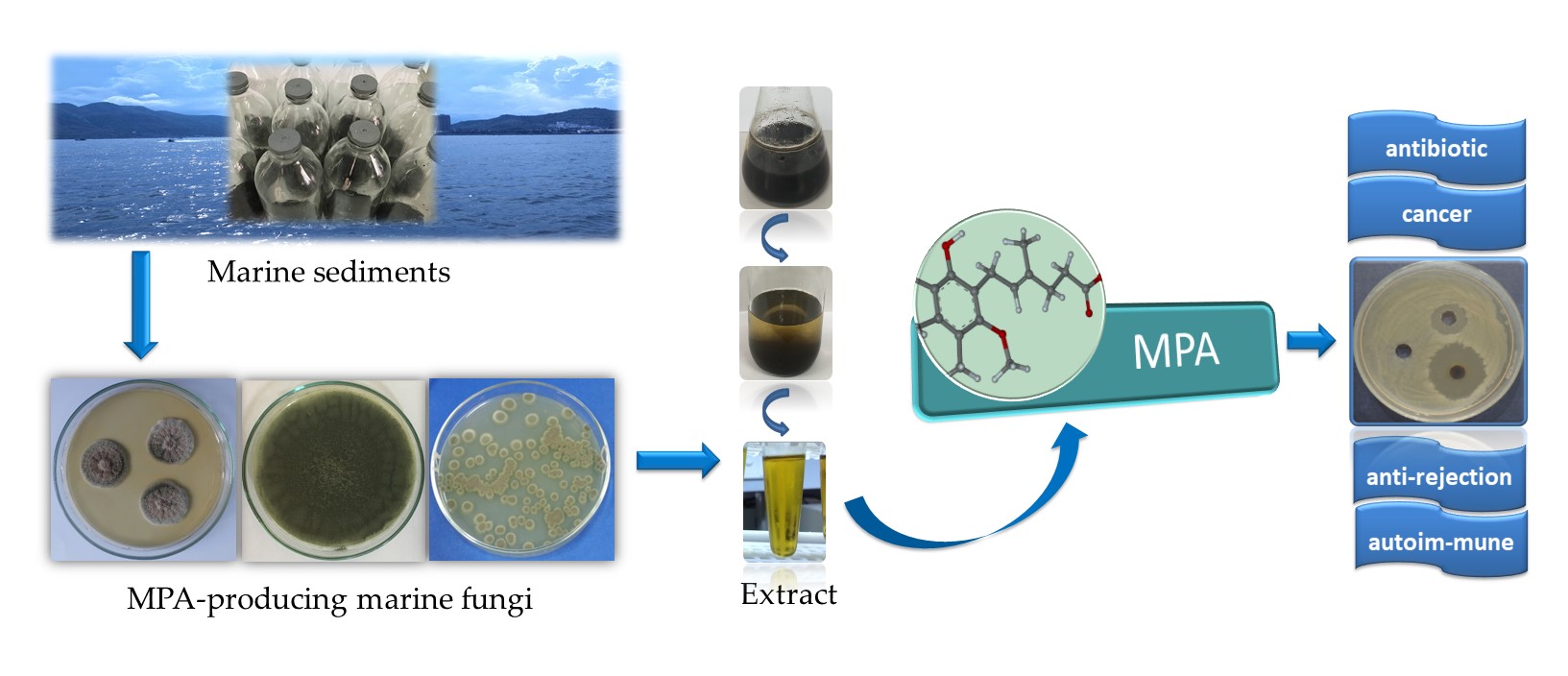

With over 3200 km of coastline and situated in a tropical and subtropical climate zone, Vietnam possesses a diverse and abundant marine microbial ecosystem. Adaptation to such harsh environmental conditions enables the microorganisms here to possess high metabolic capabilities. Marine-origin fungi, with their significant advantages in unique ecological environments, have secondary metabolites that need to be explored to discover new biologically active natural products (antimicrobial, antiviral, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory activities) [

1]. One bioactive compound, mycophenolic acid (MPA) and its derivatives extracted from marine fungi, has attracted considerable attention from chemists and pharmacologists due to its diverse biological activities.

MPA (6-(4-hydroxy-6-methoxy-7-methyl-3oxophthalanyl)-4-methyl-4-hexenic acid) is a drug currently attracting much attention for its potential applications in anti-rejection therapy (such as kidney, heart, and liver transplants), treatment of autoimmune diseases (such as Crohn, lupus and psoriasis), inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth, antiviral (such as hepatitis C virus), antifungal, antibacterial, and as a new generation antibiotic [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Mycophenolic acid is available in two formulations - mycophenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium. Mycophenolate mofetil is a prodrug developed to improve the bioavailability of mycophenolic acid. Mycophenolate sodium has the potential to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects, primarily diarrhea, by delaying the release of mycophenolic acid into the small intestine instead of the stomach. Both formulations are rapidly hydrolyzed to the active metabolite mycophenolic acid [

7,

8,

9].

Globally, MPA and its derivatives are mainly synthesized chemically. However, chemically synthesized products are often contaminated with undesirable impurities, requiring significant effort and chemicals for purification. Impurities in chemically synthesized MPA often cause unwanted side effects for users. Therefore, the production of pharmaceutical products from naturally occurring MPA obtained from microorganisms is currently receiving considerable research attention and has yielded promising results. Fungal strains capable of synthesizing MPA are a source of active ingredients that are easy to control and manipulate, and can be obtained in large quantities in the shortest time.

MPA is a secondary metabolite produced by a limited number of filamentous fungi. MPA was first discovered in the fermentation broth of

Penicillium glaucum in 1896 and was also found in cultures of

P. stoloniferum in 1913 by Alsberg and Black [

10]. So far, some MPA-producing fungi were identified and determined the ability to produce MPA, including the genera P

enicillum,

Aspergillus, and

Byssochlamys [

11,

12,

13]. These MPA-producing fungal strains were isolated from various substrate sources such as cereals, fruits, meat, vegetables, cheese, bread, sediments, soil, sand. The majority of them were identified in the genus

Penicillium, including

P. roqueforti, P. brevicompactum (

P. stoloniferum),

P. rugulosum, P. glabrum,

P. carneum,

P. bialowiezense,

P. arizonense,

P. canescens (

P. raciborskii) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Most strains of the genus

Penicillium had the ability to produce MPA with initial concentrations ranging from 10-700 mg/L/or kg. The marine-derived fungal strains that produce MPA and its derivatives reported to include several strains belonging to the genera

Penicillium (

P. parvum,

Penicillium sp.) and

Rhizopus oryzae [

22,

23,

24,

25]. MPA and its derivatives from fungal strains have been reported to possess antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties. Three MPA derivatives extracted from strain

Rhizopus oryzae, penicacid (H, I, J), revealed activity against Gram-positive bacteria (

Staphylococcus aureus) and two Gram-negative bacteria (

Escherichia coli and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [

25]. Mycophenolene A isolated form

Penicillium sp. MNP-HS-2 exhibited antibacterial activity against

S. aureus [

26].

In Vietnam, there are not many published studies related to MPA-producing microorganisms. Some of our previous studies reported on the isolation and screening of marine fungal strains (Quang Ninh province, northern Vietnam) capable of synthesizing MPA, which were identified as belonging to the genus

Penecillium (

P. roqueforti,

P. brevicompactum,

P. oxalicum, P. citrinum, and

P. lanoso) [

27,

28]. The present study was a follow-up to our previous studies and for the first time, we report the isolation of a novel MPA-producing marine fungal strain,

Cladosporium, together with the results of antimicrobial activity assessment of this isolated compound against two Gram-positive (

S. aureus ATCC 33591 and

Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778) and Gram-negative (

E. coli ATCC 25922) bacteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Marine Fungi

A total of 57 marine sediment samples were collected from coastal areas in provinces of different ecological regions of Vietnam, including provinces of central Vietnam (Hue – 21 samples, Da Nang – 14 samples) and southern Vietnam (Phu Quoc – 22 samples). Samples were collected at depths ranging from 20 to 50 meters above sea level. For the isolation of fungal strains, 10 g of sample was mixed with 90 mL of sterile dH

2O and vortexed thoroughly at room temperature for 10 min. One milliliter of the resulting suspension was 10-fold serially diluted and spread onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) agar plates supplemented with 35 g/L of NaCl and two antibiotics, streptomycin (50 µg/mL) and penicillin (100 µg/mL) to prevent any bacterial growth (PDAS). The plates were then aerobically incubated at 28

0C for 72 h. After incubation, individual colonies were purified by restreaking them twice onto PDAS agar plates using the hyphal tip method [

29]. The final pure cultures were numbered and transferred to PDAS slant tubes for storing at 4 °C and as mycelia with spores in 15% glycerol at −80 °C. Isolated fungi were preserved at the VAST-Culture Collection of Microorganisms (VCCM), Institute of Biology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology.

2.2. Preparation of Marine Fungal Extracts

Each of the fungal strains was inoculated into 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 mL Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) medium supplemented with NaCl and antibiotics such as PDAS and cultured at 150 rpm on a rotary shaker at 28 °C for 5 days.

The MPA extraction process was conducted according to the method of Ismaiel et al. (2014) [

30] with some modifications. The cultured fungal strain was filtered to collect the supernatant, removing the fungal biomass. The extracellular fluid was acidified to pH 2.0 with 2M H2SO4 and defatted with n-hexane at ambient temperature. After the adjustment of the pH the solution was cooled to 25°C and stirred for two hours. Then MPA was extracted with the organic solvent ethyl acetate at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) for one hour. The solvent was then filtered through anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated to dryness in a rotary evaporator at 56

0C (IKA, RV10, Germany). The extracted residue was collected and dissolved in 1000 μL of pure methanol. The methanolic extract was subjected to chromatographic separation.

2.4. Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC)

The methanolic extracts containing MPA were detected by TLC, following the method described by Ismaiel et al. (2014) [

30]. Both TLC analysis of the methanolic extracts and the methanolic solution of MPA standard (≥ 98% purity, Sigma-Aldrich) were carried out on Merck 0.25-mm silica gel plates and developed in a solvent system of toluene: ethyl acetate: formic acid (6: 3: 1) by spotting on the start line of a silica gel plate (10 × 20 cm). MPA spots (Rf = 0.65) showed blue coloration under long wavelength ultraviolet light using UVIS. These fluorescent bands were visualized more clearly by exposing the chromatogram to ammonia vapor before observing under UV lamp light.

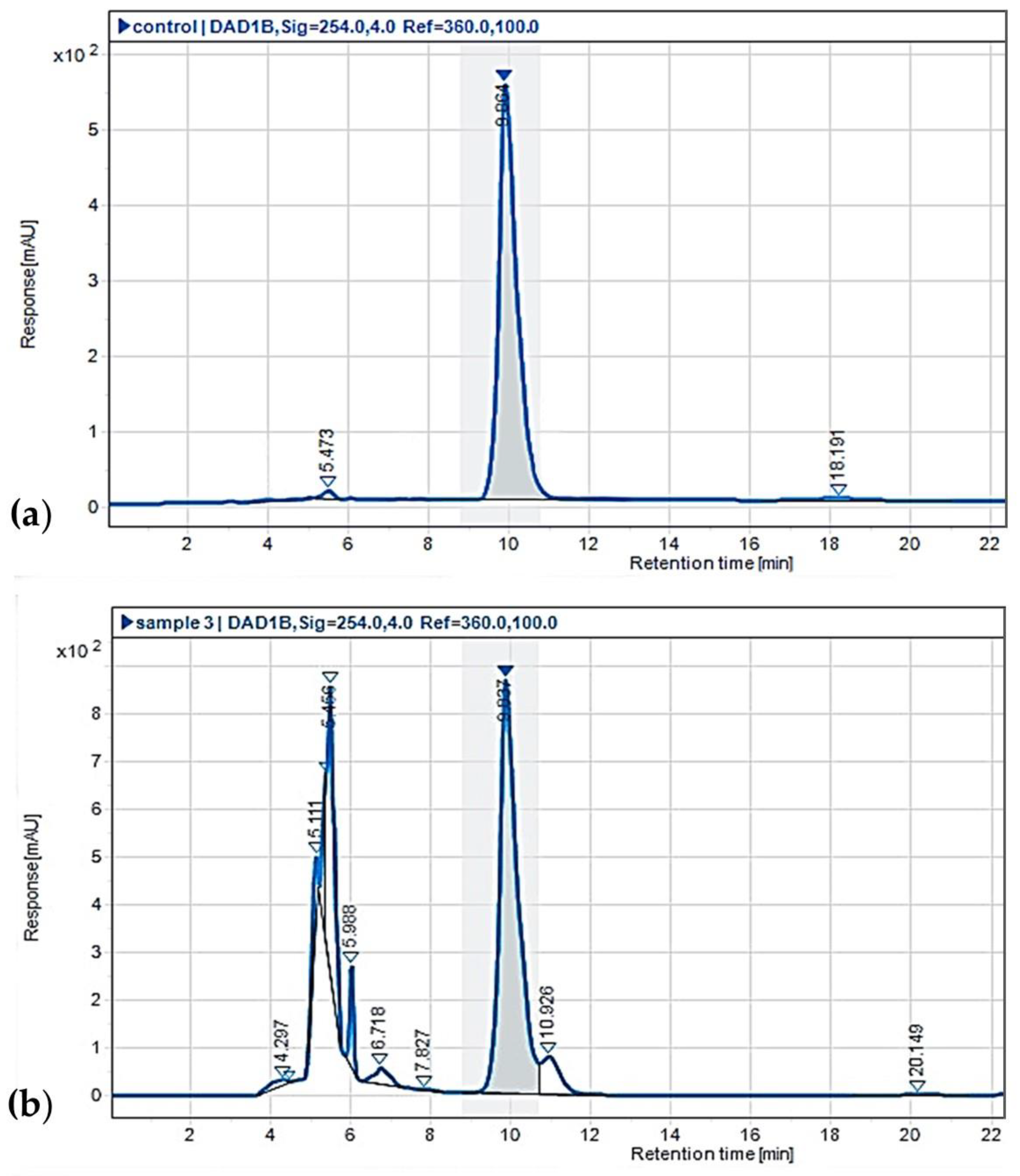

2.3. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The crude and purified extracts containing MPA were detected using HPLC-DAD-MS. The HPLC analysis was performed on an Agilent 1260 infinity II Bio HPLC system (Agilent Technologies Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada) using a Symmetry C18 reverse phase-column (4.6 mm × 25 cm, 5 μm) (Waters Corporation, Massachusetts, USA) with a diode-array detector (DAD) monitored from 200 to 500 nm. The indicator solution and the analyzed samples were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter before injection. The mobile phase was water and acetonitrile at a ratio of 50:50 (v/v). The elution was isocratic for 30 min at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and a column temperature of 350C. Ten microliters of the methanolic extracts were injected. The UV detector was set to 254 nm. Quantification was achieved using the standard curve generated from the MPA standard over a 2.5–125 μg/mL concentration range at which the peak area and height exhibited linear relationships with the absorbance (r2 = 0.9991).

Electrospray ionization mass spectra (ESI-MS) were used to confirm the ion [M+H]+ of MPA in the chromatograms. Mass spectroscopy was performed on purified MPA sample. The electrospray ionization combined with mass spectrometry spectrum was ob-tained using an Agilent 6120 Single Quadrupole LC–MS Agilent 1260 system (Agilent, Santa Claraa, Calif., USA).

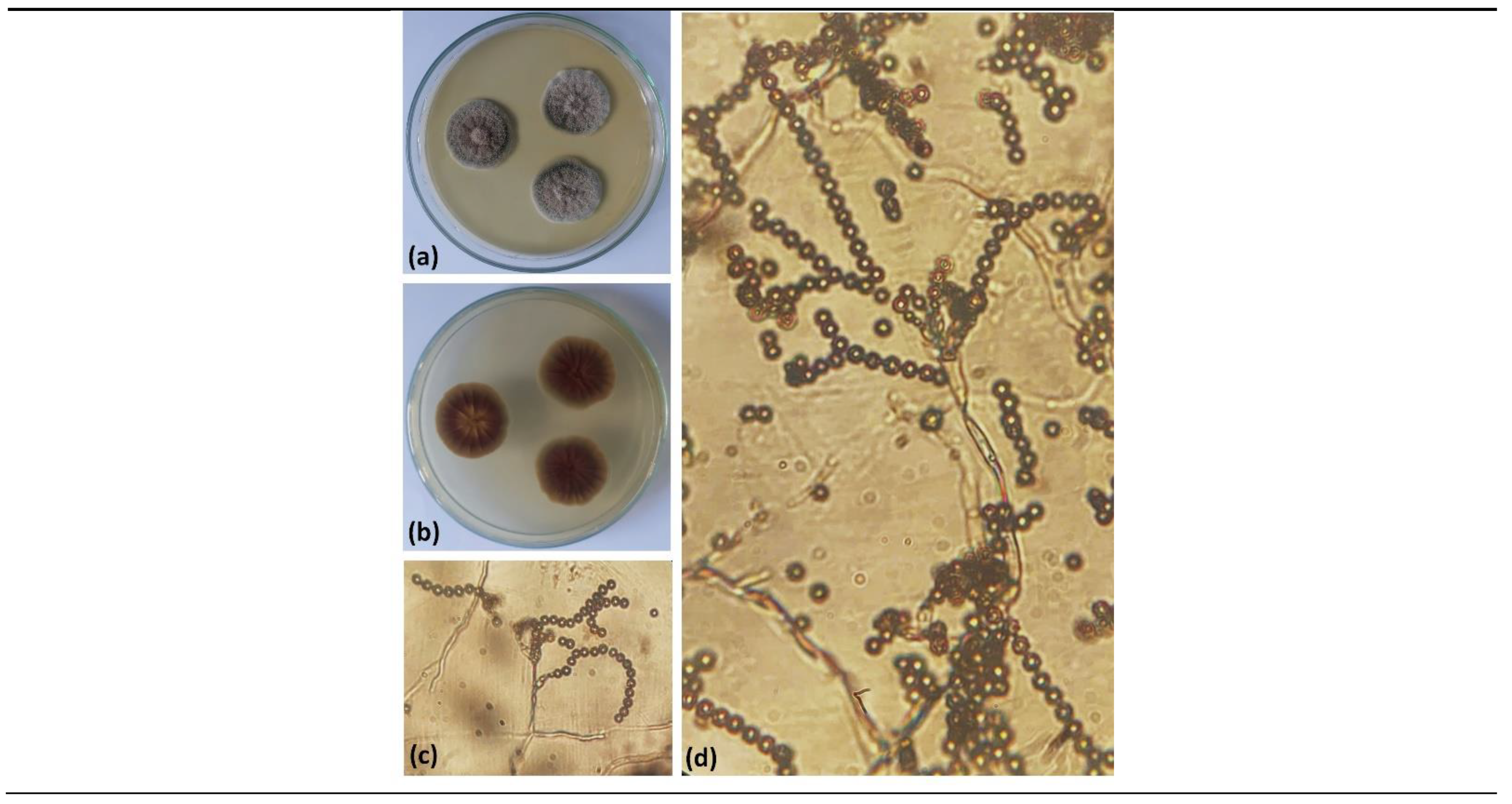

2.4. Identification of Marine Fungi

Identification of marine fungi was determined following the previous procedure [

31]. The fungal strains were cultured on plates on PDAS medium at 28 °C for morphologically identification. The hyphae or spores of the marine fungi were spread on slides. Hyphae, sporulation, and conidia were observed by light microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Their taxonomic positions were determined using taxonomic data previously reported by Ainsworth et al. (1973) and Dong (1984) [

32,

33].

The molecular biological method of fungal classification was based on the analysis of the sequence of the Internal Transcribed Region (ITS) by PCR amplification to confirm the reliability of morphological identification. The isolated fungi were inoculated into 50 mL PDBS medium and shaken at 150 rpm at 28 °C for three days. The fungal mycelium was obtained by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes and then finely ground in liquid nitrogen. The fungal genomic DNA was extracted using the GeneJET Plasmid Midiprep kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. An ~500 bp rDNA region comprising ITS1-5,8S-ITS2 was amplified by PCR using the universal primers ITS1 (5’–CCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG–3’) and ITS4 (5’–CCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC–3’) as described by White et al. (1990). The PCR products were examined by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gel in 1X TAE buffer (Tris-acetate-EDTA) and then purified using a GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). The PCR products were sequenced using an AEI PRISM@ 3700 Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Mass., USA). The ITS sequences were trimmed and compared with ITS sequences available in GenBank databases using the BLASTn program (NCBI- National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md., USA).

2.5. Study of the Growth Dynamics and MPA Biosynthesis of Marine Fungi

MPA-producing marine strain was cultured in 200 mL PDBS medium and shaken at 150 rpm at 28 °C for 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, 108, 120, 132, 144, 156, 168, 180, 192, 204, 216, 228 and 240 hours with three replicates at each time period. The supernatant and fungal biomass from three replicates at different times were harvested using a filter. The fungal biomass was dried at 55 °C. The extractions and yields of extracellula MPA of strain were determined by the methods mentioned above. The collected data were statistically analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel 2019 software.

2.6. Antibacterial Assay of MPA Extract

The biological activity of purified MPA extract was tested on five reference bacterial strains including

S. aureus ATCC 33591,

B. cereus ATCC 11778,

E. coli ATCC 25922,

P. aeruginosa ATCC 12228, and

Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13048. The antibacterial assay was determined by agar disk diffusion method according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute described in M100-Ed31 [

34] with some modifications. The Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates were inoculated uniformly on the entire surface with the trial bacteria previously adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard solution. The purified fungal MPA extract was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 2 mg/mL concentration. The 100 µl of this extract was added to each well created on the previously inoculated LB agar. DMSO was used as a negative control, and ampicillin at a concentration of 1 mg/ml (dissolved in phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 0.1 mol/L) as a positive control. The plates were kept at 4°C for 2–4 hours to allow the extract to diffuse into the medium, then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The measurement of the inhibition halos (mm) was made with a vernier, and percent inhibition was determined using Equation:

I (%) = {(DE – DW) / (DC – DW)} × 100

where I is the inhibition (%), DE is the MPA extract halo diameter, DW is the white halo diameter (using DMSO), and DC is the positive control halo diameter (using antibiotic).

2.7. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of MPA Extract

MIC were determined by the microdilution method in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) on 96-well polystyrene microtiterplates according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [

35] recommendations with some modifications. A stock solution of 5.12 mg/mL MPA extract was prepared. On 96-well titration plates 100 μl of MHB medium was applied. Then, 100 μl of the MPA solution was added to each of the first wells in each column and serial double dilutions were made, concentration range from 512.0 to 0.5 μg/ml. The ampicillin was used as a positive control with concentration range from 256.0 to 0.25 μg/ml. DMSO was used as a negative control. Finally, 100 μl of suitable bacterial suspension (previously adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard solution) was inoculated to each well. Inoculated plates were incubated at 35 ± 1 °C for 18–24 h. Resinazurin (10 μl of 0.015% aqueous solution) was added to each well and incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 2 h. The measurements of absorbance and visual evaluation of color according to control were made, where pink or colorless indicated growth and blue indicated growth inhibition. The lowest concentration at which color change occurred is taken as the MIC value. MIC values were determined in 3 replicates in 3 independent experiments. Statistical work has been done using the Microsoft Excel 2019 in all calculations, assuming p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Screening of MPA-Producing Marine Fungi

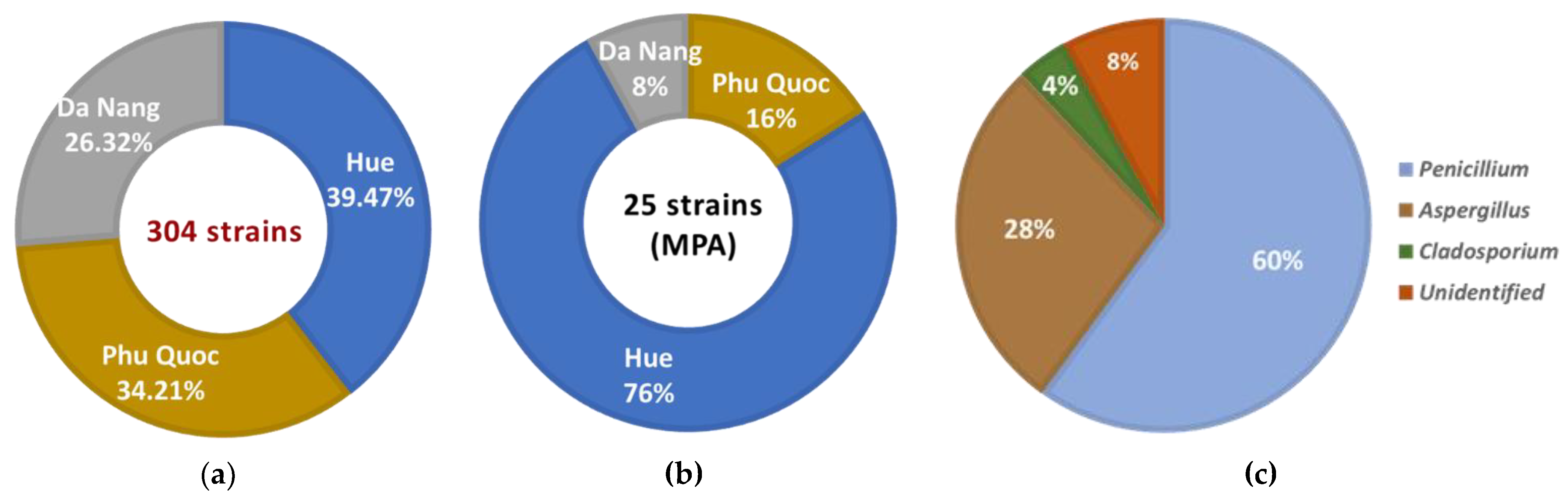

A total of 304 marine fungal strains were collected from marine sediments of provinces in the central and south of Vietnam (including Hue, Da Nang, and Phu Quoc). The highest number of fungal strains collected from marine sediment samples was in Lang Co - Hue (120 strains ~ 39.47%), followed by Phu Quoc (104 strains ~ 34.21%) and My Khe - Da Nang (80 strains ~ 26.32%) (

Figure 1a).

The crude extracts of the 304 fungal strains were assessed for the presence of MPA using TLC analysis. The results of TLC analysis confirmed the presence of MPA at twenty-five strains (8.22% of 304 strains), of which the majority of strains were isolated in Lang Co - Hue sea with 19 strains (76%), the remaining 4 strains in Phu Quoc sea (16%) and 2 strains in Da Nang sea (8%) (

Figure 1b;

Table 1). The fungal compounds extracted from the marine fungal strains exhibited a retention factor (Rf) value of 0.65, which was similar to Rf value of standard MPA.

The morphology of conidia, colonies, and unique phenotypic characteristics of these MPA-synthesizing strains were identified. The 25 strains were confirmed to belong to 3 genera, with 23 strains and 2 unidentified strains (8%). The

Penicillium genus was the majority with 15 strains (60%), followed by the

Aspergillus genus with 7 strains (28%), and only one strain belonged to the

Cladosporium genus (4%) - strain MBLC9-138 (

Figure 1c;

Table 1;

Figure 2). Strain MBLC9-138 was selected for further studies.

3.2. Quantification and Confirmation of MPA in Fungi

HPLC analysis was performed to confirm the presence of MPA in the MBLC9-138 strain. The results confirmed the presence of MPA based on its retention time, which was consistent with that of the MPA standard. Both the MBLC9-138 extract and the MPA standard exhibited maximum UV absorption at 254 nm, with closely matching retention times of 9.837 and 9.864 min, respectively (

Figure 3). The MPA yield from the MBLC9-138 strain reached 463.25 mg/L when cultured in PDBS medium at 28°C with shaking at 150 rpm for five days. Furthermore, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in positive mode showed that the MS spectrum of the MBLC9-138 extract was identical to the MPA standard, featuring the [M+H]

+ ion at m/z 321.12.

3.3. Identification of MPA-producing Marine Fungi (MBLC9-138) Based on ITS Sequences Analysis

The MPA-producing marine strain, MBLC9-138, was identified through ITS sequence analysis. The ITS region of the ribosomal DNA (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) from strain MBLC9-138 was amplified by PCR, sequenced, and analyzed using BLAST searches against the GenBank database (

Table 2). The analysis yielded a 496 bp sequence, which showed 99.6% similarity and 100% query coverage with strains belonging to both the genus

Cladosporium (specifically

C. cladosporioides - OM236880,

C. tenuissimum - ON795078, and

C. oxysporum - KU577140) and the genus

Ectophoma (

E. multirostrata - KR709058 and ON705553).

Because of this high similarity across two different genera, initial BLAST results were insufficient to definitively classify the strain. Consequently, a comparative analysis was performed using type strains (standard strains) from both genera. The results revealed that the ITS sequence of MBLC9-138 had 95% query coverage and 99.37–99.79% similarity with

Cladosporium type strains (including

C. cladosporioides CBS 112388,

C. tenuissimum CPC 14253, and

C. oxysporum CBR23). In contrast, it showed only 92.42% similarity and 39% query coverage with the type strain

E. multirostrata CBS 274.60. Combined with its morphological characteristics, these molecular data confirm that strain MBLC9-138 belongs to the genus

Cladosporium. As it could not be assigned to a specific species, it was designated as

Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 (

Table 2). The fungal strain

Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 was deposited at the VAST-Culture Collection of Microorganisms, Institute of Biology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology with accession number VCCM-44320.

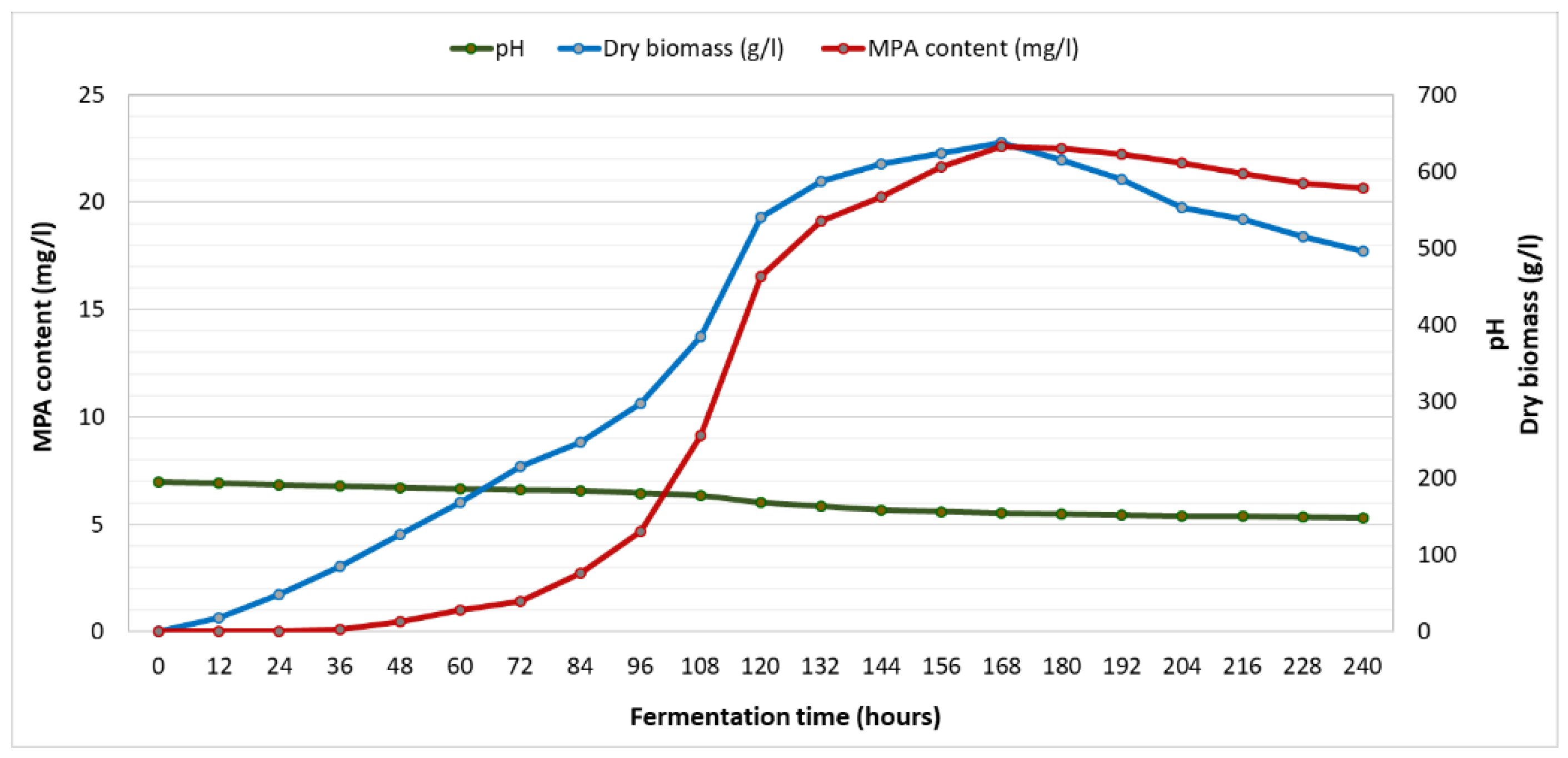

3.3. Growth Dynamics and MPA Biosynthesis of the Marine Fungal Strain

To evaluate the MPA - producing process of

Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 strain for further research, the growth dynamics of this strain were studied during cultivation on PDBS medium for 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, 108, 120, 132, 144, 156, 168, 180, 192, 204, 216, 228 and 240 hours. At each growth stage, fermentation broth of the strain was collected to determine MPA yield (

Figure 4).

During the cultivation process, both the biomass and MPA-producing capacity of strain MBLC9-138 increased progressively during the exponential phase (60–120h). The culture then entered the stationary phase (132–168h), where nutrient availability supported optimal mycelial growth and peak MPA production. The maximum dried biomass and MPA yield were both achieved at 168 h, reaching 22.76 ± 0.86 g/L and 632.03 ± 2.39 mg/L, respectively. Subsequently, a decline phase was observed from 180 to 240 h, characterized by a gradual decrease in both biomass and MPA concentration. To obtain the highest MPA content, strain MBLC9-138 needed to be fermented for approximately 168±12 hours and the product recovered. Throughout the fermentation, the medium pH dropped from an initial 7.0 to 5.29 at the end of the fermentation process, likely due to the accumulation of organic acids, including MPA, produced during fungal growth (

Figure 4).

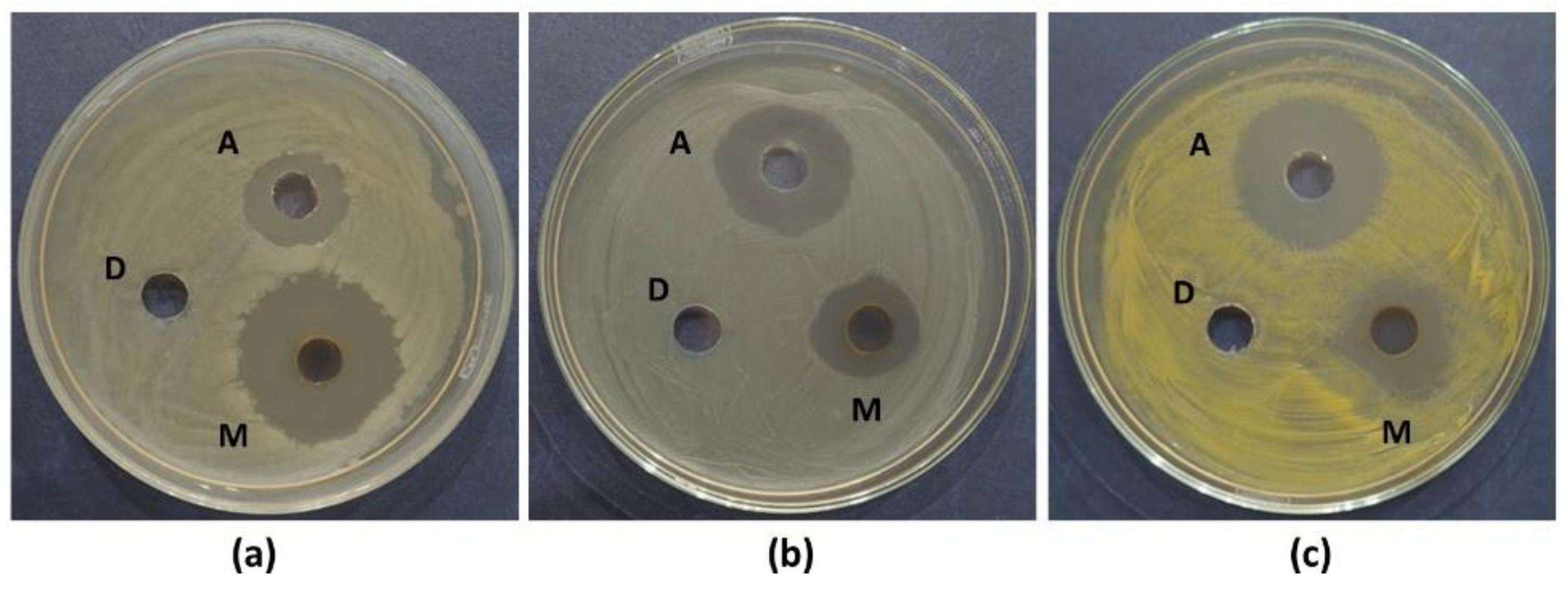

3.4. Antibacterial Assay and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of MPA Extract

The antimicrobial activity of the purified MPA extract was evaluated against five indicator bacterial strains. Significant growth inhibition was observed in three of the tested microorganisms: two Gram-positive bacteria (

S. aureus ATCC 33591 and

B. cereus ATCC 11778) and one Gram-negative bacterium (

E. coli ATCC 25922). Specifically, the MPA extract was found to be most effective against

B. cereus (175.00 ± 3.76%), followed by

S. aureus (76.60 ± 1.97%) and

E. coli (74.16 ± 0.83%). No antibacterial activity was exhibited by

P. aeruginosa,

K. aerogenes, and the negative control (DMSO), whereas a distinct zone of inhibition was produced by the positive control (ampicillin at 1 mg/mL) (

Figure 5).

The MIC of the MPA extract was determined against the three susceptible strains (S. aureus, B. cereus, and E. coli) using concentrations ranging from 512.0 to 0.5 μg/mL. The highest inhibitory effect was achieved against B. cereus at an MIC of 16 μg/mL. For E. coli and S. aureus, MIC values were recorded at 32 and 64 μg/mL, respectively. Additionally, the MIC values of ampicillin against these strains were measured at 2.0, 8.0, and 4.0 μg/mL.

4. Discussion

The surge in multidrug-resistant bacteria over the past few decades has been closely linked to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics, resulting in infections that are difficult or impossible to treat. These include life-threatening nosocomial infections caused by

S. aureus,

E. coli, and

P. aeruginosa [

36]. Therefore, it is essential to discover more novel antimicrobial compounds to maintain as large a stockpile of potential antimicrobial agents as possible for use when needed. Marine-derived fungi are a prolific source of new natural products featuring novel chemical scaffolds with intriguing pharmacological activities including antimicrobial, antiviral, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory activities [

1,

25,

37].

MPA is a phenyl-terpenoid fungal secondary metabolite that is an effective inhibitor of inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) widely applied in clinics in the prophylaxis of allograft rejection and autoimmune disorders treatment, in the forms of its prodrugs: sodium mycophenolate (MPS) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) [

7,

8,

9,

38]. The novel MPA derivatives are also investigated to improve therapeutic effectiveness and mitigate undesired side [

26,

38]. MPA and its derivatives have been shown to have anti-cancer activity [

39,

40,

41] as well as antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and antiparasitic properties [

25,

26,

42,

43].

Thus far, MPA-producing fungal strains have been isolated from various substrates, including cereals, fruits, meat, vegetables, cheese, bread, sediments, soil, and sand. The majority of these strains were identified within the genus

Penicillium, such as

P. roqueforti, P. brevicompactum (

P. stoloniferum),

P. rugulosum, P. glabrum,

P. carneum,

P. bialowiezense,

P. arizonense,

P. canescens (

P. raciborskii [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Additionally, a few strains were reported to belong to the genera

Aspergillus and

Byssochlamys. Among them,

A. pseudoglaucus and

A. nidulans [

11,

12,

13,

44], were isolated from diverse sources like wood, insects, and sand, with MPA concentrations ranging from 1 to 17 mg/kg. The synthesis of approximately 20 mg MPA/L was recorded for the

B. nivea NRRL2615 strain [

12]. Most strains of the genus

Penicillium were found to produce MPA at initial concentrations of 10–700 mg/L or mg/kg. However, some strains showed high MPA production, for instance,

P. roqueforti strains isolated from blue mold cheese reached 800–4000 mg MPA/kg [

16] or

P. brevicompactum ATCC 16024 strain produced 1720 g MPA/L [

45]. Marine-derived MPA-producing fungi have also been reported, including several species within the genera

Penicillium (

P. parvum,

Penicillium sp.) and

Rhizopus oryzae [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties of MPA and its derivatives have been extensively documented. Three MPA derivatives (penic acids H, I, J) extracted from

R. oryzae were found to inhibit Gram-positive (

S. aureus) and two Gram-negative bacteria (

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa) with MIC ranging from 62.5 to 250 µg/mL [

25]. Mycophenolene A isolated form

Penicillium sp. MNP-HS-2 was shown to exhibit potent activity against

S. aureus (MIC = 2.1 μg/mL) [

26].

In Vietnam, only a limited number of studies have addressed MPA-producing microorganisms. Our previous research reported the isolation and screening of marine fungal strains from Quang Ninh province (Northern Vietnam) capable of synthesizing MPA. Among them, strain

P. roqueforti G1.1 produced 0.431 mg MPA/L in PDBS medium, while

P. brevicompactum BB263 high yielded 969.79 µg/mL when cultured in YES-F1 medium (modified PDBS medium) [

27,

28]. The present study was a follow-up to our previous studies. In this study, 304 fungal strains were isolated from marine sediments across Central and Southern Vietnam. Twenty-five strains capable of synthesizing MPA were identified by TLC analysis, with the majority (19 strains) originating from Lang Co, Hue province (Central Vietnam). These producers were preliminarily classified into three fungal genera and two unidentified strains, including

Penicillium (15 strains),

Aspergillus (7 strains), and

Cladosporium (1 strain). These findings underscore the potential of Vietnamese marine sediments as a rich reservoir for bioactive microorganisms, particularly MPA producers. Notably, HPLC analysis revealed that the

Cladosporium strain exhibited superior MPA production, yielding between 463.25 and 632.03 mg/L after 5–7 days of cultivation. ITS region sequencing confirmed this strain as

Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138, marking the first report of MPA biosynthesis within this genus. Furthermore, the MPA extracted from

Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 demonstrated significant antibacterial activity against

E. coli (Gram-negative),

S. aureus, and

B. cereus (Gram-positive), with MIC values of 32, 64, and 16 µg/mL, respectively. These results highlight a promising candidate for enhancing therapeutic bioavailability in clinical applications—such as immunosuppression and oncology—while potentially mitigating gastrointestinal side effects and antibiotic resistance.

The Vietnamese healthcare sector faces significant challenges in managing high-mortality conditions, such as cancer, autoimmune diseases, acute infections, and post-transplantation organ rejection. These conditions are increasing in both prevalence and severity. Notably, the demand for organ transplantation in Vietnam is substantial, with over 1,000 procedures performed annually; however, post-surgical rejection remains a major obstacle. Furthermore, the rising incidence of autoimmune diseases and cancer continues to be a leading cause of mortality. Currently, Vietnam must import most medications and raw pharmaceutical materials, including those containing mycophenolate sodium and mycophenolate mofetil. This heavy reliance on foreign sources leads to high costs, which limits patient access to essential treatments. Therefore, the Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 strain offers a promising alternative for industrial-scale MPA production due to its potential to produce MPA with dual therapeutic benefits. To meet the stringent requirements of commercial production, our future research will focus on strain improvement and the optimization of fermentation parameters. Due to the novelty and potency of the findings, the patent describing MPA production by Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 is under consideration by the Intellectual Property Office of Viet Nam under Application 2-2024-00752 (December 31, 2024).

5. Conclusions

This study constitutes the first report of Cladosporium sp. MBLC9-138 with MPA biosynthetic potential, through which a yield of 463.25–632.03 mg/L was achieved after a 5–7 days cultivation. The isolated MPA exhibited significant antibacterial activity against E. coli (Gram-negative), S. aureus, and B. cereus (Gram-positive), with MIC values of 32, 64, and 16 µg/mL, respectively. Promising evidence is provided by these findings for the development of bio-derived MPA to enhance dual bioavailability in clinical treatments—including immunosuppression for organ transplantation, autoimmune diseases, and oncology—while gastrointestinal side effects and bacterial drug resistance could potentially be reduced. Future research will focus on genetic strain improvement and the optimization of fermentation parameters to facilitate industrial-scale MPA production in Vietnam. Additionally, of 304 fungal strains isolated from diverse climatic marine sediments in Central and Southern Vietnam, 25 isolates belonging to Penicillium, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, and unidentified strains were confirmed as MPA producers. This underscores Vietnamese marine sediments as a rich reservoir for bioprospecting bioactive compounds and MPA-producing microorganisms.

Author Contributions

Field sampling, design of the scientific experiments and methodology, laboratory tasks, and data analyses, H.T.P., H.T.T.T., T.T.P., D.T.N., N.P.N., and T.T.M.L.; conception of the idea of the research, writing—original draft preparation and editing, writ-ing—review, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration, T.T.M.L. and N.P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology (Vietnam), grant number DTĐL.CN.06/21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.[i]

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corre-sponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the VAST-Culture Collection of Microorganisms, Institute of Biology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (htpp://vccm.vast.vn).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blunt, J.W.; Carroll, A.R., Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A. Prinsep MR: Marine natural products. Natural Product Reports 2018, 35(1), 8-53. [CrossRef]

- Bentley, R. Mycophenolic Acid: a one hundred year odyssey from antibiotic to immunosuppressant. Chem Rev 2000, 100(10), 3801-3826. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Emmanuel, J.; Abraham, J. Production, characterization and molecular docking of mycophenolic acid by Byssochlamys nivea strain JSR2. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 6, 227-230.

- Chen, L.; Wilson, D.J.; Labello, N.P.; Jayaram, H.N.; Pankiewicz, K.W. Mycophenolic acid analogs with a modified metabolic profile. Bioorg Med Chem 2008, 16(20), 9340-9345. [CrossRef]

- Patro, J. P.; Priyadarsini, P. Mycophenolic acid: A drug with a potential beyond renal transplantation. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2016, 4, 3666-3669. [CrossRef]

- Regueira, T.B.; Kildegaard, K.R.; Hansen, B.G.; Mortensen, U.H.; Hertweck, C.; Nielsen, J. Molecular basis for mycophenolic acid biosynthesis in Penicillium brevicompactum. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77(9), 3035-3043. [CrossRef]

- Ghio, L.; Ferraresso, M.; Zacchello, G.; Murer, L.; Ginevri, F.; Belingheri, M.; Edefonti, A. The role of post-transplant clinical and therapeutic variables. Clinical Transplantation 2009, 23(2), 264-270. [CrossRef]

- Jablecki, J.; Kaczmarzyk, L.; Patrzałek, D.; Domanasiewicz, A.; Boratyńska, Z. First Polish forearm transplantation: report after 17 months. In: Transplantation Proceedings 2009, Elsevier, 549-553. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B. Mycophenolic acid trough level monitoring in solid organ transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil: association with clinical outcome. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2006, 22(12), 2355-2364. [CrossRef]

- Alsberg, C.; Black, O.F. Contributions to the study of maize deterioration: biochemical and toxicological investigations of Penicillium puberulum and Penicillium stoloniferum (No. 270). US Government Printing Office, 1913.

- Mouhamadou, B.; Sage, L.; Perigon, S.; Seguin, V.; Bouchart, V.; Legendre, P.; Caillat, M.; Yamouni, H.; Garon, D. Molecular screening of xerophilic Aspergillus strains producing mycophenolic acid. Fungal Biol 2017, 121(2), 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Puel, O.; Tadrist, S.; Galtier, P.; Oswald, I.P.; Delaforge, M. Byssochlamys nivea as a source of mycophenolic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71(1),550-553. [CrossRef]

- Vinokurova, N.G.; Ivanushkina, N.E.; Kochkina, G.A.; Arinbasarov, M.U.; Ozerskaia, S.M. Production of mycophenolic acid by fungi of the genus Penicillium link. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol 2005, 41(1), 95-98.

- Ammar, H.A.; Ezzat, S.M.; Elshourbagi, E.; Elshahat, H. Titer improvement of mycophenolic acid in the novel producer strain Penicillium arizonense and expression analysis of its biosynthetic genes. BMC Microbiol 2023, 23(1), 135. [CrossRef]

- Cakmakci, S.; Gurses, M.; Hayaloglu, A.A.; Cetin, B.; Sekerci, P.; Dagdemir, E. Mycotoxin production capability of Penicillium roqueforti in strains isolated from mould-ripened traditional Turkish civil cheese. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 2015, 32(2), 245-249. [CrossRef]

- Lafont, P.; Debeaupuis, J.P.; Gaillardin, M.; Payen, J. Production of mycophenolic acid by Penicillium roqueforti strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 1979, 37(3):365-368. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudian, F.; Sharifirad, A.; Yakhchali, B.; Ansari, S.; Fatemi, S.S. Production of Mycophenolic Acid by a Newly Isolated Indigenous Penicillium glabrum. Curr Microbiol 2021, 78(6), 2420-2428. [CrossRef]

- Overy, D.P.; Frisvad, J.C. Mycotoxin production and postharvest storage rot of ginger (Zingiber officinale) by Penicillium brevicompactum. Journal of Food Protection 2005, 68(3), 607-609. [CrossRef]

- Rundberget, T.; Skaar, I.; Flaoyen, A. The presence of Penicillium and Penicillium mycotoxins in food wastes. Int J Food Microbiol 2004, 90(2), 181-188. [CrossRef]

- Schneweis, I.; Meyer, K.; Hormansdorfer, S.; Bauer, J. Mycophenolic acid in silage. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66(8), 3639-3641. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhu, H.; Sun, W.; Hu, Z et al. Mycophenolic Acid Derivatives with Immunosuppressive Activity from the Coral-Derived Fungus Penicillium bialowiezense. Mar Drugs 2018, 16(7). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Zhou, G.L.; Sun, C.X.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, G.J.; Zhu, T.J.; Li, J.; Che, Q.; Li, D.H. Penicacids E-G, three new mycophenolic acid derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium parvum HDN17-478. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 2020, 18(11), 850-854. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Ju, J. Penicacids A-C, three new mycophenolic acid derivatives and immunosuppressive activities from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. SOF07. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2012, 22(9), 3332-3335. [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Chen, G. Three New Antibacterial Mycophenolic Acid Derivatives from the Marine-Derived Fungus Penicillium sp. HN-66. Chem Biodivers 2025, 22(1), e202401657. [CrossRef]

- Pilevneli, A.D.; Ebada, S.S.; Kaskatepe, B.; Konuklugil, B. Penicacids H-J, three new mycophenolic acid derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Rhizopus oryzae. RSC Adv 2021, 11(55), 34938-34944. [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, M.S.; Ibrahim, N.; Elissawy, A.M.; Anwar, A.; Ibrahim, M.A. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial mycophenolic acid derivatives from an endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. MNP–HS–2 associated with Macrozamia communis. Phytochemistry 2024, 217, 113901. [CrossRef]

- Nhue, N.P.; Tu, H.T.M.; Binh, C.T. Study on the antibacterial activity and mycophenolic acid synthesis ability of a marine fungus strain. Military Medical Journal (Vietnam) 2021, 353, :9-14.

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, H.H.; Bach, T.M.H.; Dang, T.T.D.; Le, T.M.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, P.N. Isolation of Penicillium strains from the mangrove forests of the Northern coastal region with high potential for mycophenolic acid production for pharmaceutical applications. Vietnam Journal of Biotechnology 2025, 23(4), 507-516. [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.; Daisy, B.; Castillo, U.; Harper, J. Natural products from endophytic microorganisms. J Nat Prod 2004, 67(2), 257-268. [CrossRef]

- Ismaiel, A.A.; Ahmed, A.S.; El-Sayedel, S.R. Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions for immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid production by Penicillium roqueforti isolated from blue-molded cheeses: enhanced production by ultraviolet and gamma irradiation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 30(10), 2625-2638. [CrossRef]

- Thi Minh Le, T.; Thi Hong Hoang, A.; Thi Bich Le, T.; Thi Bich Vo, T.; Van Quyen, D.; Hoang Chu, H. Isolation of endophytic fungi and screening of Huperzine A-producing fungus from Huperzia serrata in Vietnam. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1), 16152. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, G.C.; Sparrow, F.K.; Sussman, A.S. Introduction and keys to higher taxa. In. The Fungi, An Advanced Treatise. Academic Press NewYork and London, 1973.

- Dong, B.X. The Hyphomycetes fungi group in Vietnam. Science and Technics Publishing House, 1984.

- Humphries, R.; Bobenchik, A.M.; Hindler, J.A.; Schuetz, A.N. Overview of Changes to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, M100, 31st Edition. J Clin Microbiol. 2021, 59(12), e0021321. [CrossRef]

- Kahlmeter, G.; Brown, D.; Goldstein, F.; MacGowan, A.; Mouton, J.; Odenholt, I.; Rodloff, A.; Soussy, C.J.; Steinbakk, M.; Soriano F. et al. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) technical notes on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006, 12, 501-503. [CrossRef]

- Laws, M.; Shaaban, A.; Rahman, K.M. Antibiotic resistance breakers: current approaches and future directions. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2019, 43(5), 490-516. [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, J.F. Natural Products from Marine Fungi--Still an Underrepresented Resource. Mar Drugs 2016, 14(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Iwaszkiewicz-Grzes, D.; Cholewinski, G.; Kot-Wasik, A.; Trzonkowski, P.; Dzierzbicka, K. Synthesis and biological activity of mycophenolic acid-amino acid derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 69, 863-871. [CrossRef]

- Cholewiński, G.; Iwaszkiewicz-Grześ, D.; Prejs, M.; Głowacka, A.; Dzierzbicka, K. Synthesis of the inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) inhibitors. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 30(4), 550-563. [CrossRef]

- Domhan, S.; Muschal, S.; Schwager, C.; Morath, C.; Wirkner, U.; Ansorge, W.; Maercker, C.; Zeier, M.; Huber, P.E; Abdollahi, A. Molecular mechanisms of the antiangiogenic and antitumor effects of mycophenolic acid. Mol Cancer Ther 2008, 7(6), 1656-1668. [CrossRef]

- Sintchak, M.D.; Nimmesgern, E. The structure of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase and the design of novel inhibitors. Immunopharmacology 2000, 47(2-3), 163-184. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, M.S.; Zachariah, M.; Harris, E. Mycophenolic acid inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing replication of viral RNA. Virology 2002, 304(2), 211-21. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, R.; De Stefano, M.; De Stefano, S.; Trincone, A.; Marziano, F. Antagonism against Rhizoctonia solani and fungitoxic metabolite production by some Penicillium isolates. Mycopathologia 2004, 158(4), 465-74. [CrossRef]

- Jarczynska, Z.D.; Hoof, J.B.; Aasted, F.; Holm, D.K.; Patil, K.R.; Nielsen, K.F.; Mortensen, U.H. Heterologous production of immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid in Aspergillus nidulans. In: 13th European Conference on Fungal Genetics: bridging fungal genetics, evolution and ecology, 2016, 457-457.

- Peng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Mahato, R.I. Synthesis and Characterization of a Novel Mycophenolic Acid-Quinic Acid Conjugate Serving as Immunosuppressant with Decreased Toxicity. Mol Pharm 2015, 12(12), 4445-4453. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).