1. Introduction

The service life and performance of asphalt pavements are fundamentally determined by the mechanical behaviour of asphalt mixtures, which is closely related to the rheological properties of the binder (bitumen). Due to the time-varying nature of traffic loads and the combined (synergetic) effect of temperature and aging, bitumen types behave as viscoelastic materials, so a single test parameter is not sufficient to characterize them. Laboratory methods that can describe the time- and frequency-dependent behaviour of the binder and the mixture are gaining increasing emphasis. Tests performed with a dynamic shear rheometer (DSR) are able to determine the complex viscosity and phase angle. At the same time, traditional tests, such as penetration and softening point measurements, forming the basis of the European bitumen standardization, are still widely used in practice. However, international practice, including Australian bitumen classification, places greater emphasis on dynamic viscosity measured by the vacuum capillary method at 60 °C, which characterizes the material’s internal resistance to shear, allowing for a more detailed characterization of the pavement’s behaviour.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. History and Limitations of the Vacuum Capillary Viscometer for Testing Road Bitumen

The vacuum capillary viscometer is the classic laboratory method for the dynamic viscosity of bitumen types. Its test is performed at 60 °C and a vacuum of ~300mmHg (≈40kPa), with an “apparent” viscosity calculated from time–volume measurements based on the Hagen–Poiseuille law. The method was made an industry standard by the Cannon–Manning, Asphalt Institute and Modified Koppers capillaries, which became widespread in the 1930s; today the ASTM D2171/D2171M-22 [

1,

2] and EN12596:2023 [

3] standards specify the details, including that for non-Newtonian binders the result is an “apparent” value dependent on the shear rate [

3]. Traditionally, viscosity at 60 °C has been used to indicate the temperature-dependent deformation resistance. This method is still widely used today, especially in the research and formulation optimization of elevated viscosity and high elasticity (HVMA/HVE) binders; several recent studies characterize modified binders by the viscosity at 60 °C measured by the vacuum capillary method [

4,

5,

6]. For high viscosity binders prepared for two-layer, porous asphalts, the viscosity at 60 °C is a decisive indicator of the adhesion and cohesion properties [

7].

In the measurement with a vacuum capillary viscometer, the bitumen is “sucked up” by the vacuum in a capillary tempered in a thermostable (60±0.1 °C) bath; the dynamic viscosity can be calculated from the transit time of the marked section and the capillary constant. The advantage of the method is the good repeatability for Newtonian (unmodified) binders and the simple equipment required. However, in the case of modified (SBS/CR, TPS, etc.) bitumen types, the measurement often only gives an “apparent” viscosity because the shear rate was not directly recorded and the sample may behave in a non-Newtonian manner [

2,

6]. Furthermore, the calibration, the impurities appearing on the capillary and the vacuum stability significantly influence the measurement uncertainty [

2,

3]. As a result, other approximate methods are also used.

2.2. Viscosity Measurement Methods

Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR)

The determination of complex viscosity using a DSR (dynamic shear rheometer) is described in the EN 14770:2023 standard [

8]. The sample preparation required for the test is detailed in the EN 12594:2025 standard [

9]. The samples are poured into molds and then placed between two preheated, parallel plates of the rheometer. The load is transferred to the sample by the upper plate, while the displacement occurring on the lower plate is recorded. The applied oscillating shear stress creates the deformation in the sample to occur with a phase angle δ from the load [

10]. The ratio of the applied stress (τ) to the amplitude of the deformation (γ) provides the complex shear modulus (G*). The ratio of the shear modulus (G*) to the angular frequency (ω) gives the complex viscosity (η*) [

10]. The phase angle is suitable for characterizing the viscoelastic behaviour of the mixture. If the phase angle (δ) is 0°, the material is elastic, if δ= 90°, it is viscous, and between 0° and 90° we speak of viscoelastic behaviour [

11].

In 2010, Guericke, based on oscillation measurements and DSR studies, showed that at low frequencies (f = 0.159 Hz) the state of the material at the softening point temperature can be well characterized by the complex viscosity, whose value is η* = 1,300 Pa·s [

12]. (Later, this latter value is used to determine the viscosity at 60 °C calculated from the softening point using the Heukelom equation).

Brookfield (Rotational) Viscometer

The EN 13302:2018 standard specifies the determination of the dynamic viscosity of various bitumen types using a rotational device (Brookfield-type viscometer) [

13]. The essence of the method is that the dynamic viscosity can be calculated from the torque required to rotate a spindle immersed in the sample, which can only be compared under identical shear conditions in the case of non-Newtonian materials. The rotational visco- meter was previously criticized for its inaccuracy, but the measurement quality of modern devices is now equivalent to those of traditional methods [

10]. The relationship between dynamic and complex viscosity is important for the interpretation of the measurement. If the shear rate of the rotational measurement can be matched to the circular frequency of the oscillation measurement, then the complex viscosity and dynamic viscosity are nearly the same within the linear viscoelastic range [

14,

15].

The measuring range of the Brookfield device is determined by the spring torque, the spindle geometry and the measuring speed. Thus, the measuring range can be determined as a function of the technical parameters of the rheometer and the type of spindle used [

16]. The spring torque only gives reliable results between 10–100% of the maximum range, so the frequency sweep is very limited with a given spindle. In contrast, the dynamic shear rheometer (DSR), due to its stronger torque spring, provides a much wider measuring range [

17], although it is significantly more expensive. To measure a certain viscosity range, the appropriate spindle of the Brookfield DV2T device must be selected.

2.3. Calculation of Viscosity from Other Parameters

To predict the service life and deformation behaviour of pavement structures, it is ne- cessary to determine the viscosity and stiffness of bitumen types and asphalt mixtures. However, laboratory viscometer measurements are time-consuming and expensive, so many approximate equations are known from the literature. These empirical and semi-empirical models attempt to estimate viscosity and stiffness based on the penetration value, temperature or dynamic modulus. Although these formulas are useful for practical estimations, they can be off by one or two orders of magnitude compared to real data [

18,

19]. In the following, the most commonly used approximate equations, as well as their limitations and sources of error will be presented.

Heukelom’s Conversion (1973)

The relationship between viscosities measured at different temperatures is given by Heukelom’s empirical equation [

20]:

where C₁ and C₂ are constants specific to the bitumen type, T and T_ref are the temperature (°C) and the reference temperature (°C), respectively. This formula allows the conversion of viscosity between different temperatures [

20].

Mirza et al. (1995) Model and Witczak Equation for Viscosity

The relationship between viscosity (η, Poise) and penetration (Pen, dmm) measured at 25 °C is based on the model developed at the University of Maryland [

21]:

This equation is applicable to penetration values between 3 and 300 tenths of a millimeter and gives the dynamic viscosity at 25 °C [

21]. A revised version of this is the Witczak equation, which can estimate viscosity over a wider temperature range [

19]:

where η is the viscosity value [mPas], VTS_i is the viscosity-temperature sensitivity, T_V is the measurement temperature [°R – degree Rankine], A_i is a constant [

22]. However, for different asphalt mixture types and for different aging periods, the values of the constants A_i and VTS_i change, as does the unit of viscosity. This was noted by Witczak and Fonseca [

22] and they developed a nonlinear sigmoidal function, which, according to their research, can be applied to any unmodified asphalt type. Witczak models calculate the dynamic modulus (E*) based on the viscosity of the binder and the characteristics of the mixture. His equations have been modified several times over time, and Mirza also published calculations to approximate the dynamic modulus [

21].

Van der Poel (1954) Model for Stiffness Modulus

The Van der Poel nomogram is suitable for determining the stiffness modulus (S) [

24], which is a graphical solution of the following Maxwell-type viscoelastic model:

In the calculation, S is the desired stiffness modulus [Pa], ω is the circular frequency, E is the elastic modulus [Pa], η is the viscosity of the binder [Pa*s]. If ηω is much smaller than E, then the product of viscosity and frequency is negligible compared to the elastic modulus, i.e. the material behaves predominantly elastic, and the stiffness modulus is approximately S ≈ ηω. On the other hand, if ηω is significantly larger than E, then viscous effects dominate, the material behaves more viscously, and the stiffness approaches the elastic modulus, i.e. S ≈ E. The Van der Poel nomogram depicts these two extreme states — the purely elastic and purely viscous ranges — and the transitional range between the two, with viscoelastic behaviour, and connects them in a single graphical method [

24].

Although the above formulas are widely used, they can only provide accurate results under certain conditions. The Mirza equation [

21] is valid only at 25 °C and cannot be applied to modified bitumen types, since their non-Newtonian behaviour means that penetration is not proportional to viscosity [

19]. The Tex-535-C formula is sensitive to measurement inaccuracies: a small error in the penetration value can cause a tenfold difference in the estimated viscosity [

23]. The Heukelom equation is also limited because the parameters C₁ and C₂ are calibrated only for specific bitumen types; in other cases, it can underestimate the viscosity by up to an order of magnitude [

18].

The Witczak–Fonseca model provides a particularly favourable correlation value (R² ≈ 0.95) with the measurement results, but only in the case of conventional bitumen types; however, significant differences appear in the case of polymer-modified, rubber-modified or additive-enriched bitumen types. According to laboratory tests in Hungary by Tóth (2010), the Witczak–Hirsch models underestimated the stiffness of the asphalt mixtures by 20–30% in the temperature range above 40 °C, while they overestimated them at low temperatures [

18].

In the Van der Poel model, errors are particularly evident at very low (below –10 °C) and high (above 70 °C) temperatures, as the linear viscoelastic assumption is no longer fulfilled. According to Gutarra’s 2018 research in Peru, nomogram-based estimates of viscosity at 60 °C showed a deviation of up to two times compared to experimental data [

25]. Overall, it can be said that classical penetration and temperature-dependent models are suitable for quick, engineering-level estimates, but they often give orders of magnitude differences in the values of viscosity and stiffness modulus. Modern neural network and micromechanical approaches can reduce these errors to below 10–15% [

26], but their data and computational requirements are significantly higher, and overly complex, data-specific approximations often appear in the background.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of European and Australian Penetration and Viscosity Results with International Classification Systems

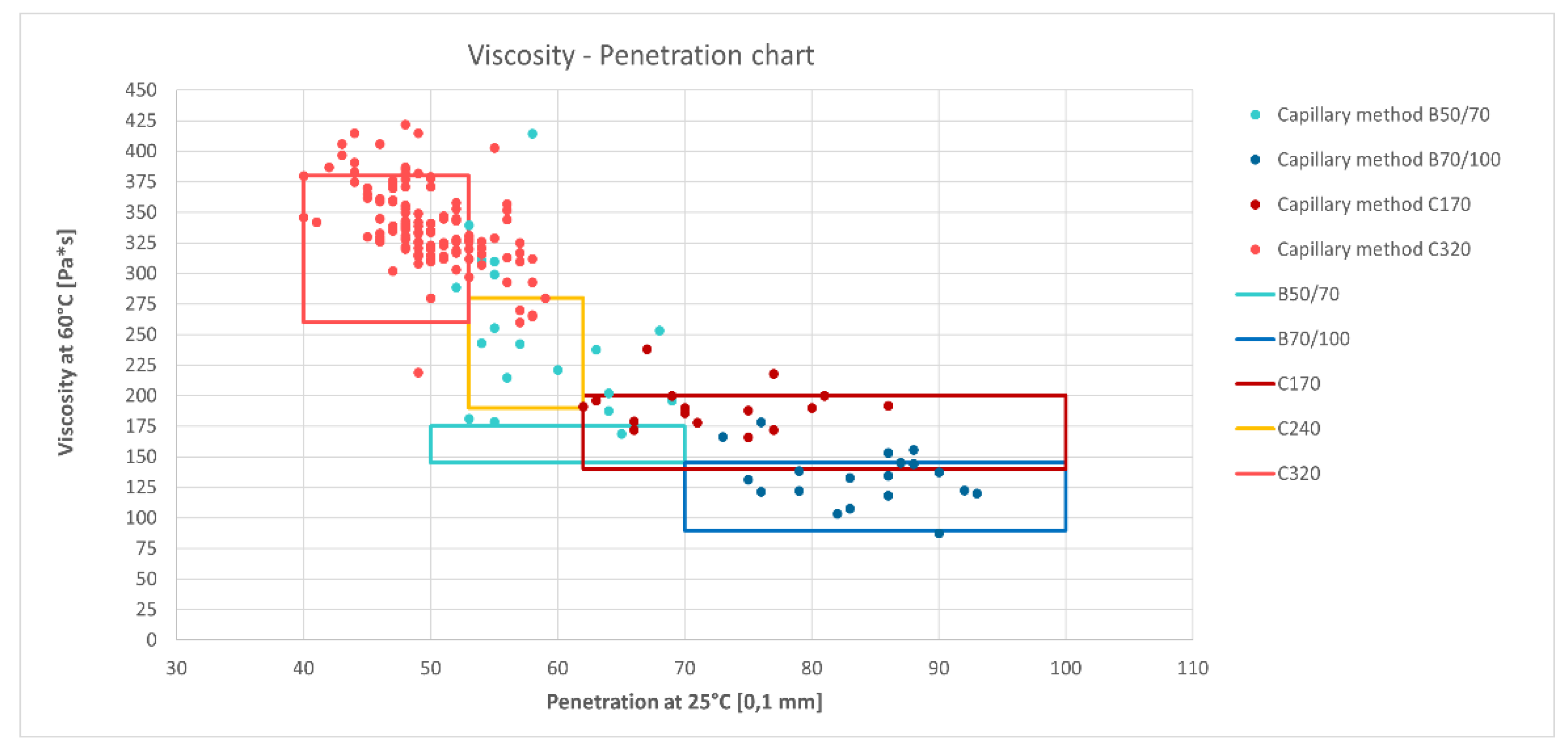

The aim of the study was to compare the penetration and capillary viscosity measured at 60 °C of different bitumen types (B50/70, B70/100, C170, C320) (

Figure 1). Based on the results obtained, with the increase in penetration – i.e. moving towards softer binders – a clear decrease in viscosity can be observed, which is in line with classical rheological expectations. The data dispersions belonging to each bitumen type are clearly visible on the graph, which allows the comparison of the different quality classes with the standard specifications.

Figure 1 shows the viscosity [Pa*s] and penetration [0.1 mm] values for different coloured bitumen types, with a frame indicating their corresponding standard limit values. The y-axis shows the dynamic viscosity [Pa*s], and the x-axis illustrates the penetration [0.1 mm] measured at 25 °C. The results of 4 different bitumen types are presented, and the corresponding Australian and European bitumen class limits are also indicated (frames). The penetration maximum of the Australian bitumen class C170 was taken as 100 based on Australian practice.

The European system (EN 12591:2009) [

27] is based on simple and rapid empirical tests such as penetration (EN 1426:2025) [

28], ring & ball softening point, Fraass breaking point. Based on these, bitumen types are assigned penetration grades (e.g. B 50/70), which are also included in the product name.

The Australian standard AS 2008-2013 [

29] defines the classification of road construction bitumen types primarily based on dynamic viscosity measured at 60 °C, supplemented by tests of viscosity measured at 135 °C and needle penetration grade measured at 25 °C. The aim of the standard is to ensure the proper processability and long-term performance of bitumen types in road construction. In the case of “C170”, “C” denotes conventional road construction bitumen, while “170” means the dynamic viscosity value (Pa s) measured at 60 °C.

The test points reflect appropriately the categorization: the B50/70 samples are located in the penetration band between 50 and 60, while the B70/100 data are located around the 75–95 range; their viscosity follows the hardness trend (lower penetration is associated with higher viscosity).

The obtained measurement points - especially for C170 and C320 - closely follow these ranges. In the graph, the data for the C-class bitumen types are concentrated in the standard viscosity bands with a small standard deviation, almost rectangularly, indicating that these products are more homogeneous rheologically and have a better controlled manufacturing quality (confirmed also in

Table 1).

The viscosity of B-type European bitumen types has a larger standard deviation, but it does not provide a much better approximation to penetration. This can be explained by the different refining technology, the greater sensitivity to temperature and chemical va-riations, and the less strict penetration classification in terms of viscosity.

The results of C-type (Australian) bitumen types are much more concentrated, and the measured points almost entirely remain within the specified viscosity class. This is because the Australian system is specifically viscosity-based, so production control also strives for greater viscosity stability. The smallest standard deviation observed for C320 type shows that this product range is the most homogeneous and stable, which can also provide a kind of feedback to European bitumen manufacturers. It is also important to note here that penetration-based European bitumen types show a much greater percentage variation in viscosity than viscosity-based Australian grades, with respect to penetration. The highest percentage standard deviation (25.55%) is given by the B50/70 bitumen class, which also has the largest percentage deviation from the standard mean (58.51%).

The data examined confirm that the viscosity-based classification system better reflects rheological stability, while the variability of European binders with penetration systems is greater. The narrow range of results for C-type bitumen types suggests that these products show a more predictable viscosity-temperature behaviour, which is particularly beneficial for performance in warm climates, such as Australia.

3.2. Statistical Analysis and Comparison of Test Results Obtained with Different Measurement Methods

The comparison includes the results of the capillary viscometer, Brookfield, and DSR measurement methods, as well as the viscosity calculated from the softening point using the Heukelom equation. Using the Mirza equation [

21] to convert the penetration values to the viscosity measured at 25 °C and then converting this to 60 °C using the Heukelom equation [

20], our results differed by orders of magnitude from the results of the other methods, so it was not part of the comparison. Similarly, the Tex-535-C approximation formula [

23] produced large deviations, so these results were not used either.

In the Heukelom equation, the viscosities measured at the softening point, taken as 1,300 Pa*s, were converted as a reference value to 60 ° viscosity values, knowing the softening point data sets (reference temperatures). The constants in the equation, based on the Heukelom approximation (1973), are as follows: C1 = 8.5; C2 = 110 [

20].

Using the DSR method, the most significant 3 different frequency measurement results were selected from the frequency sweeps, based on the literature (

Table 2).

In the case of the Brookfield type rotational viscometer RV DV2T, the shear rate was set to a value close to the range specified in the Australian guideline. In the RV (medium) spring torque range, using the SC4-27 spindle and at a speed of 0.5 RPM, a viscosity range of 50–500 Pa*s was measurable. With these settings, the shear frequency was 0.17 Hz, which is almost the same as the 0.16 Hz frequency used in the DSR tests.

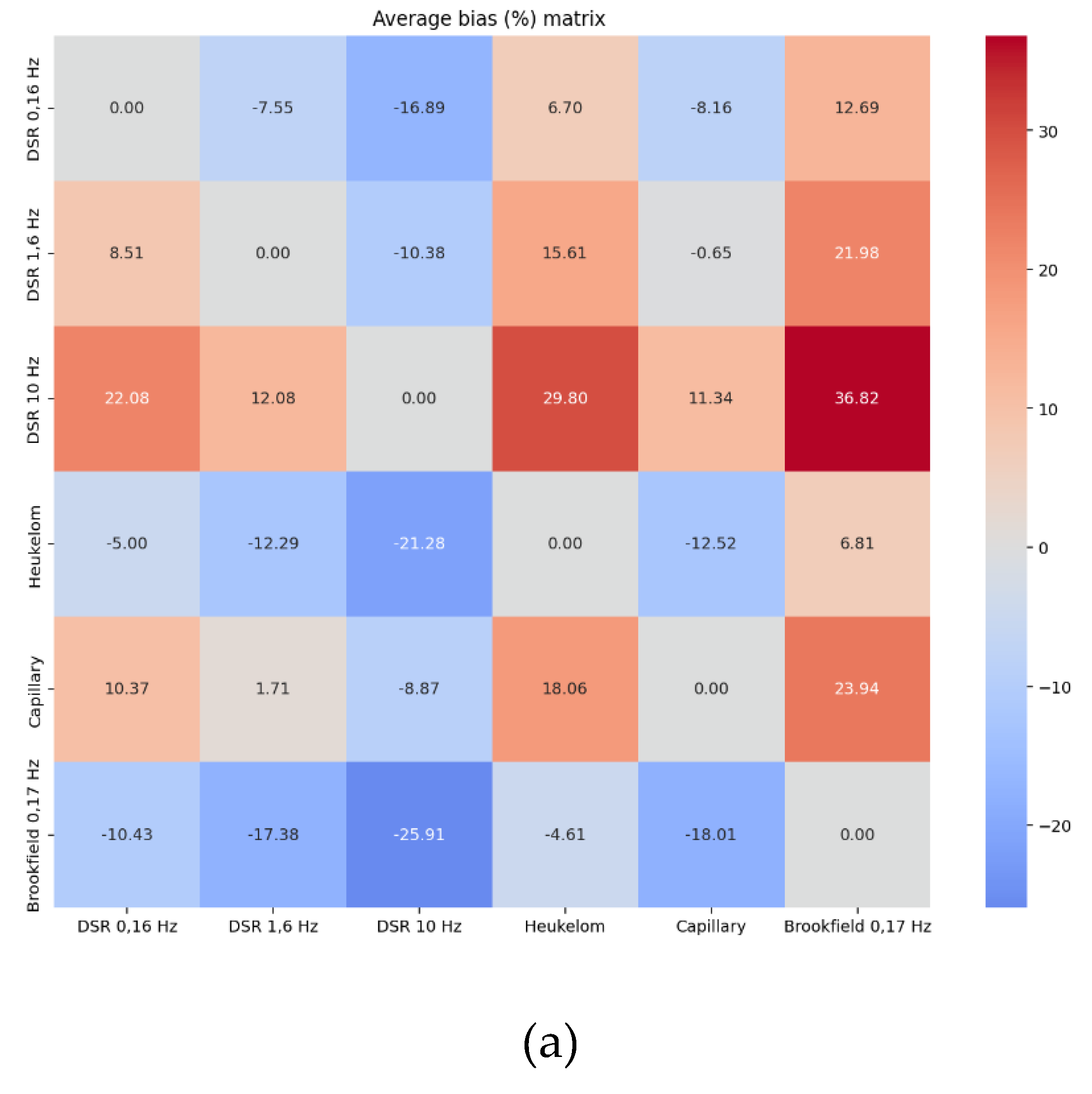

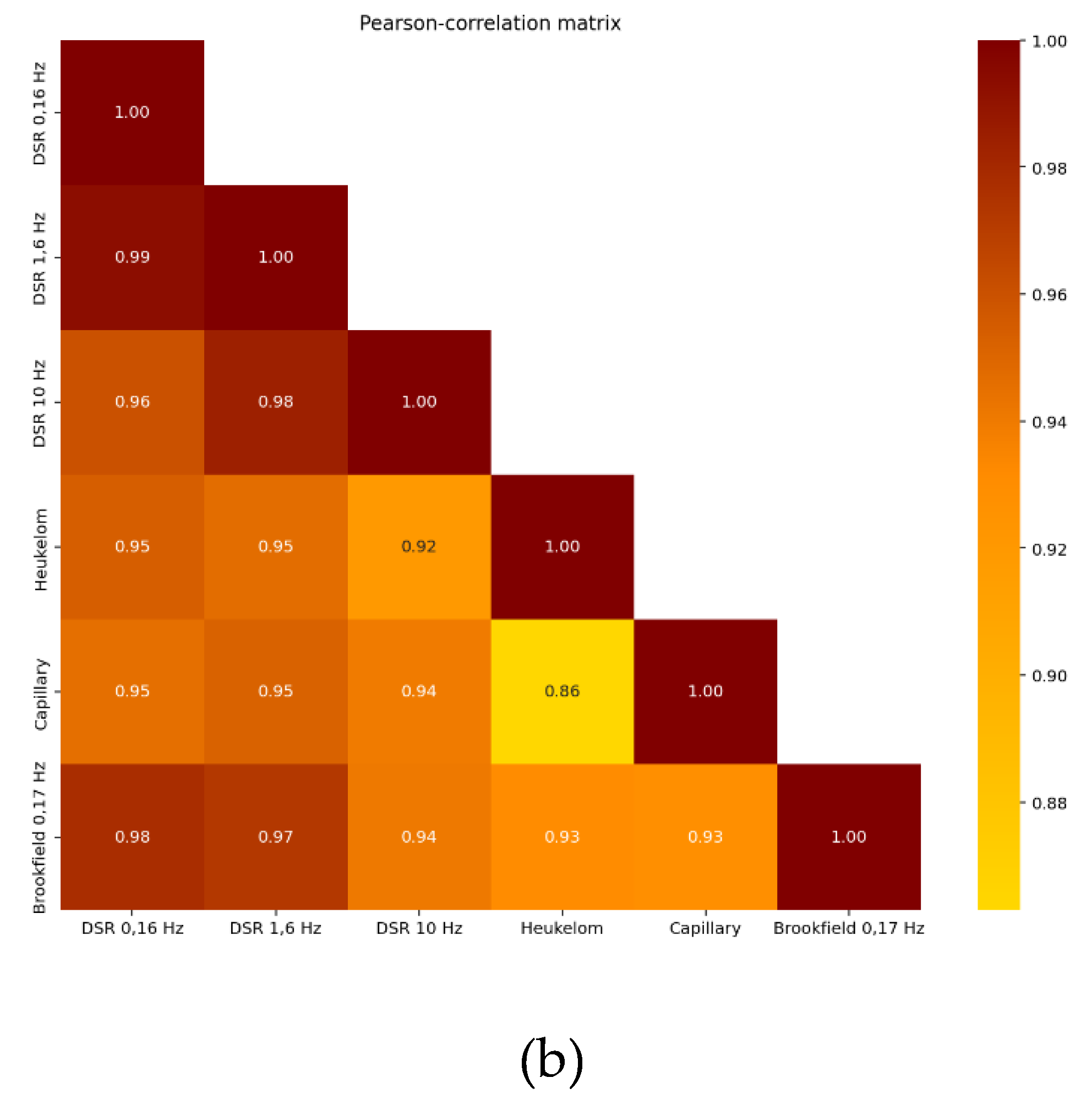

The data on

Figure 2 are: DSR dynamic shear rheometer 0.16 Hz; DSR 1.6 Hz; DSR 10 Hz; Heukelom equation (value converted from softening point); capillary method; Brookfield rotational rheometer.

Figure 2 compares the relationships between the results of different viscosity measurement methods (DSR at different frequencies, capillary viscometer, Brookfield rotational viscometer, and viscosity values derived from the softening point using the Heukelom equation). Based on the Pearson correlation matrix, there is an extremely strong linear relationship between most methods (r = 0.86–0.99), which suggests that the relative behaviour of bitumen types is ranked similarly by the system, regardless of the testing method. The DSR test at 1.6 Hz gives the highest correlation values, showing a correlation of over 0.95 with all other methods. This suggests that the 1.6 Hz oscillatory shear test best reproduces the viscosity behaviour of bitumen types, even in the measurement range of other devices.

The capillary viscometer results also show high correlations (r = 0.86–0.95), but these are lower than the correlations between the DSR measurements. This indicates that al-though the capillary method reliably reproduces the magnitude of the bitumen viscosity, systematic deviations may appear compared to other techniques due to differences in shear rate and temperature dependence. The average signed deviation matrix confirms this. Compared to the capillary method, the DSR 1.6 Hz shows an average deviation of only +1.71%, which is the smallest average deviation among the methods examined. Thus, the results obtained with the capillary viscometer are reproduced most accurately by the DSR 1.6 Hz.

Viscosities calculated from the Heukelom equation usually overestimate capillary measurement results (the average deviation is around +18.06%), which is consistent with the empirical nature of the equation. In the case of the Brookfield viscometer, this tendency is even more typical, with significant overestimations compared to other methods (e.g. +36.82% compared to DSR at 10 Hz). The results of the Brookfield viscometer correlate best with the results of the DSR method taken at 0.16 Hz, which is also justified by the instrument settings detailed earlier.

4. Conclusions

The results of Australian and European vacuum capillary viscosity measurements were compared for the first time, considering the categories of the European penetration and Australian viscosity classification. Australian C-type bitumen types show higher rheological stability, which is due to the viscosity-based classification according to the Australian standard AS2008-2013 [

29] and the quality requirements of bitumen manufactur ers.

In addition to the traditional capillary measurement method, among the formulas approximating viscosity, the Heukelom equation was used to determine the viscosity value at 60 °C from the softening point, and, as additional methods, the Brookfield rotational instrument and the DSR shear rheometer were used; the results of the latter were analysed at 3 different (0.16; 1.6; 10 Hz) frequencies. The results show that the differences between the test methods can also arise from differences in shear rate and loading frequency. The use of empirical conversion equations can only be considered reliable if their validity range and the associated test conditions are clearly defined. As a result, the approximate formulas can be wrong by orders of magnitude. The 60° dynamic viscosity measured by the vacuum capillary method, which serves as the basis for the Australian bitumen classification and is mentioned as a rheological property recommended in the European standard, can be well approximated by the Heukelom formula calculated from the softening point.

During the tests, it was observed that the values determined with the Brookfield rotational viscometer typically result in higher viscosity. Among the DSR tests, the complex viscosity measurements performed in the medium frequency range (1.6 Hz) showed the best agreement with the traditional capillary method, and this measurement showed the highest correlation on average compared to the other methods.

As a summary, it can be stated that traditional tests still play an important role in the routine qualification of bitumen types, however, to meet the requirements of modern design procedures, it is essential to take into account dynamic rheological parameters, such as the complex viscosity determined by the DSR instrument. The presented results contribute to a more accurate interpretation of the relationships between the different test methods and to the development of a more uniform, rheology-based approach. In the future, it is recommended to consider a viscosity-based classification of European bitumen types, and to use the dynamic shear rheometer (DSR) more widely instead of the vacuum capillary viscosity measurement method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sz.R and LG; methodology, SZ.R. and L.G..; validation, Z.Sz.; formal analysis, Z.SZ..; investigation, SZ.R. resources, SZ.R.; data curation, SZ.R..; writing—original draft preparation SZ.R. and Z.Sz..; writing—review and editing, L.G.; visualization, Z.Sz.; supervision, L.G., and Sz.R.; project administration, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSR |

Dynamic Shear Rheometer |

| SBS |

Styrene-Butadiene-Styrene |

| CR |

Crumb Rubber |

| TPS |

Thermoplastic Starch |

| AS |

Standards Australia |

| EN |

European Norm |

| ASTM |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

References

-

ASTM D2171; Standard Test Method for Viscosity of Asphalts by Vacuum Capillary Viscometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

-

ASTM D2171M-22; Standard Test Method for Viscosity of Asphalts by Vacuum Capillary Viscometer (SI Units). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

-

EN 12596:2023; Bitumen and bituminous binders. Determination of dynamic viscosity by vacuum capillary. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Wang, D.; Feng, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lei, J.; Yao, D.; Yi, J.; Pei, Z. Research on TPS–SBS composite-modified asphalt with high viscosity and high elasticity in cold regions. Coatings 2025, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Abdukadir, A.; Lei, J.; Yi, J.; Pei, Z. C9 petroleum resin and polyethylene-based high-viscosity modified asphalt binder: Proportioning optimization and performance study. Coatings 2025, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Feng, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lei, J.; Yao, D.; Yi, J.; Pei, Z. Research on TPS–SBS composite-modified asphalt with high viscosity and high elasticity in cold regions. Coatings 2025, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, T.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, L. High-viscosity modified asphalt mixtures for double-layer porous asphalt pavement: Design optimization and evaluation metrics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

EN 14770:2023; Bitumen and bituminous binders. Determination of complex shear modulus and phase angle. Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

-

EN 12594:2025; Bitumens and bituminous binders. Preparation of test samples. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Rosta, Sz.; Gáspár, L. Útépítési bitumen és visszanyert bitumen elegyének dinamikai viszkozitás számítása és előrebecslési lehetősége. Közlekedéstud. Szemle 2023, 73, 21–37. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheidaei, M. Dynamic Shear Rheometer for Rheological Investigation of Bitumen in Road Applications: The Impact of Measurement Technique. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Guericke, R. 100 Jahre Erweichungspunkt Ring und Kugel: Was kommt danach? Strasse Autobahn 2010, 61, 481–491. (In German) [Google Scholar]

-

EN 13302:2018; Bitumen and bituminous binders. Determination of dynamic viscosity of bituminous binder using a rotating spindle apparatus. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Remisová, E.; Zatkaliková, V.; Schlosser, F. Study of rheological properties of bituminous binders in middle and high temperatures. Civil Environ. Eng. 2016, 12, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, W.P.; Merz, E.H. Correlation of dynamic and steady flow viscosities. J. Polym. Sci. 1958, 28, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield Engineering Laboratories. More Solutions for Sticky Problems: A Guide to Getting More from Your Brookfield Viscometer and Rheometer; Brookfield Engineering Laboratories: Middleboro, MA, USA, 2014; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Parhamifar, E.; Tyllgren, P. Assessment of asphalt binder viscosities with a new approach. In Proceedings of the 6th Eurasphalt & Eurobitume Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 1–3 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, Cs. Aszfaltkeverékek merevsége a terhelési idő, hőmérséklet és szemeloszlás függvényében. Ph.D. Thesis, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Budapest, Hungary, 2010. (In Hungarian). [Google Scholar]

- Bíró, Sz. Kémiailag stabilizált gumibitumenek előállítása és vizsgálata. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Veszprém, Veszprém, Hungary, 2005. (In Hungarian). [Google Scholar]

- Heukelom, W. Bitumen and Bituminous Mixtures; Koninklijke/Shell-Laboratorium: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.W.; Witczak, M.W. Predicting asphalt viscosity from penetration. In Proceedings of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists (AAPT), Reno, NV, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Witczak, M.W.; Fonseca, O.A. Revised predictive model for dynamic (complex) modulus of asphalt mixtures. Transp. Res. Rec. 1996, 1540, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Department of Transportation. Tex-535-C: Calculating Viscosity from Penetration; TxDOT: Austin, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Poel, C. A general system describing the visco-elastic properties of bitumens and its relation to routine test data. J. Appl. Chem. 1954, 4, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutarra Lara, L. Influencia de las fibras acrílicas en mezclas asfálticas en caliente. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Continental, Huancayo, Peru, 2018. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Karki, P.; Kim, Y.R.; Little, D.N. Dynamic modulus prediction of asphalt concrete mixtures through computational micromechanics. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2507, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

EN 12591:2009; Bitumen and bituminous binders. Specifications for paving grade bitumens. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

-

EN 1426:2025; Bitumens and bituminous binders. Determination of needle penetration. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

-

AS 2008-2013; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |