1. Introduction

The use of RAP in production of bituminous mixtures

varies between different European Union (EU) countries. In Poland, for example,

the use of RAP is considered unsatisfactory, limited generally to paving dirt

roads, hardening of road shoulders or as an ingredient of

mineral-cement-emulsion mixtures and mineral-cement mixtures with foamed

bitumen addition. When used for production of bituminous mixtures, RAP is added

directly to the mixing drum, typical of the cold-in-place process [1,2]. A serious drawback of this method is a higher

temperature to which aggregate must be heated during the mixture production, as

compared to the conventional production methods. The above-mentioned

requirement limits the amount of added RAP to 20-30%. Bearing in mind

environmental protection, we should try to maximise the use of RAP in both

resurfacing and new construction project. Besides, the hot-in-place recycling

method should be the option of choice then. It would allow increasing the

amount of RAP added to the mixture or use RAP as the only ingredient, as the

case may be. However, this method requires installation of an additional, so

called “black drum” as part of double barrel for RAP heating.

That said, we must not forget that bitumen

properties change over time due to ageing [3,4].

The properties affected by ageing include increased stiffness and viscosity and

a higher softening point. Penetration and ductility decrease in turn. The aged,

stiff, and brittle binder from the RAP increases the mixture stiffness and can

therefore cause fatigue and low-temperature damages [5].

Ageing of bitumens occurs already during mixing, due to high temperature to

which it must be heated, extending through delivery to the jobsite and

placement on the road, altogether referred to as short-term ageing. The changes

taking place during this ageing type are rapid in nature. The ageing processes

taking place during the pavement operation are, on the other hand, slow,

causing gradual deterioration of bitumen due to exposure to oxygen and UV

radiation, hence the name: long-term ageing. The amounts of aromatics and

resins decrease, with a simultaneous increase in the amount of asphaltenes and

their association. The bitumen changes its composition and chemical structure

as a result. Therefore, to restore the original structure in aged bitumens,

naphthene and aromatic components should be replenished in the first place.

The requirement to restore the bitumen properties

depends on the RAP application rate and the type and severity of ageing of the

bitumen it contains. This is especially true for higher RAP application rates.

The properties of old bitumen may be improved, for example, by adding to the

mixture a bitumen of a softer grade. However, this option is recommended only

for mixtures containing small amounts of RAP or where the bitumen ageing is not

that severe. Rejuvenating treatment is another option to consider, which

restores the desired properties to old bitumens.

There are a number of available rejuvenating agents

or rejuvenators of varying effectiveness [5–10].

They include conventional fats, such as plant or animal oils and mineral oils,

including spent ones. Imidazolines also belong to this group. This application

of imidazoline was confirmed in the studies reported in [11–13]. However, these tests were carried out on a

20/30 pen grade bitumen, which is, however, considered insufficient to judge

the effectiveness of imidazoline as a bitumen rejuvenating agent. Besides

rejuvenation imidazolines were found to have anti-ageing effect on bitumens, as

demonstrated by the study results reported in [14,15].

In this case, 50/70 pen grade bitumen was used in the relevant tests. This

determination was subsequently confirmed by the test results obtained on a

160/220 pen grade bitumen [16,17] an 95/35 pen

bitumen [18]. The least covered in the

available literature is the rejuvenating effect of imidazoline on lab aged pen

grade bitumens. Data is scarce also on the effect imidazoline addition has on

bituminous mixtures containing RAP. In the author’s opinion, supported by the

literature review and earlier own studies carried out by the author, this issue

definitely deserves more attention. Therefore, the author investigated the

effect of rapeseed imidazoline addition on the properties of lab aged 35/50 pen

grade bitumen. This study is presented in this article. The underlying reason

for testing this particular type of material was the desired increase in the

use of RAP in production of bituminous mixtures. This is a topical issue for

countries where reuse of old asphalt in hot-in-place recycling process is as

yet unsatisfactorily low and Poland belongs to this group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. The bituminous binder

The bituminous binder tested in this research was

35/50 bitumen manufactured by Nynas. This specific bitumen was chosen because

of its widespread use in road paving projects in Poland. It is recommended by

the Polish engineering guidelines WT-2 published in 2014 [19] for roadbase and binder course mixtures for

traffic load category 3-7 (KR3-7) pavements. It can also be used to produce

mastic asphalt suitable for KR1-4 traffic class wearing courses and for bridge

deck protection layers. The main properties of the bitumen are given in

Table 1.

2.1.2. The rejuvenators

The rejuvenating agents chosen for this study were

two natural imidazolines obtained from rapeseed oil, manufactured by

Blachownia, Kędzierzyn-Koźle, Poland, further called type 1 and type 2.

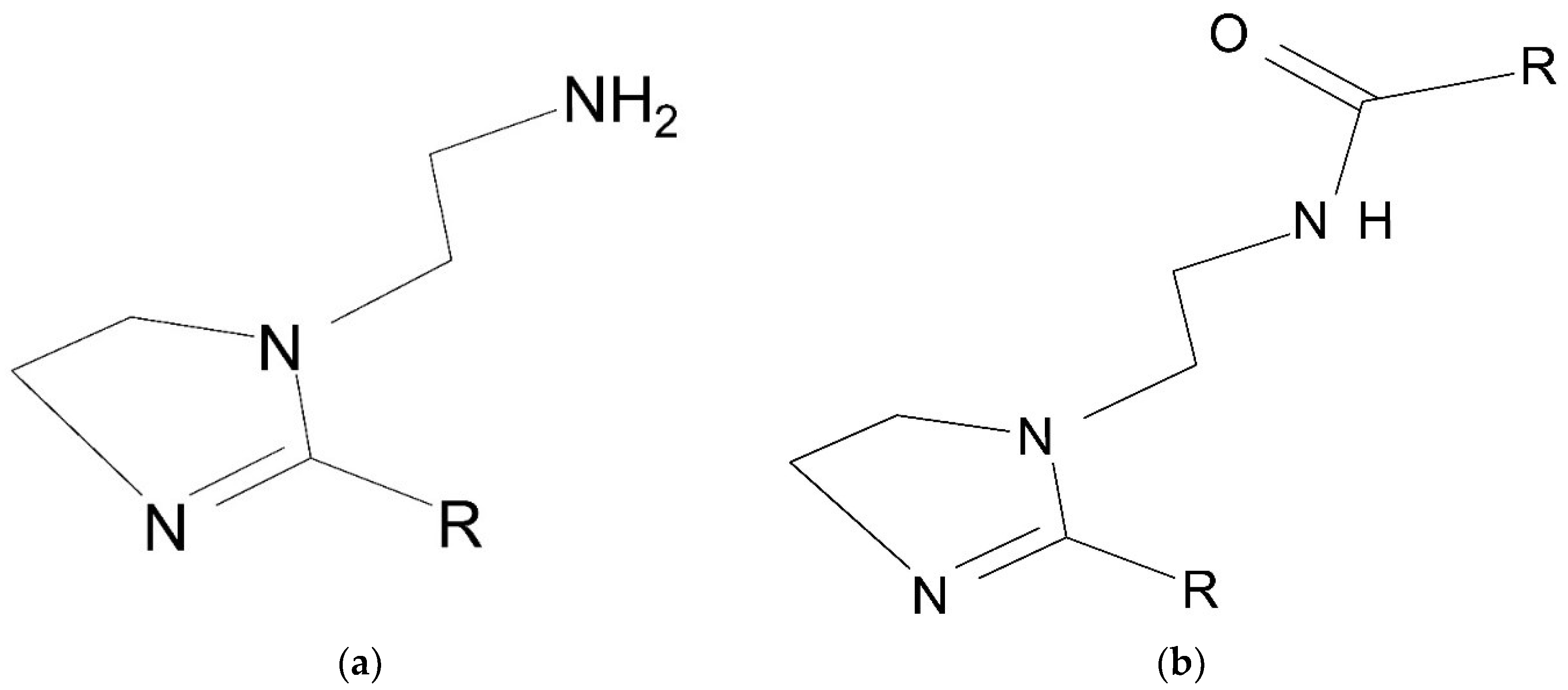

Chemical structure are given in

Figure 1.

These are surface-active, most often cationic, heterocyclic organic compounds [21]. Their chemical reactivity results not only

from the five-member ring containing two nitrogen atoms, but also from the

function groups: -NH2 (type 1) and NH-CO (type 2). Imidazolines are useful in

various industrial applications (e.g. as corrosion inhibitors, dispersants and

emulsifiers in metal working, textiles and paper industries or as rheology

modifiers and adhesion promoters in road making, paint and ink industries).

2.2. Methods

As the first step, the 35/50 pen

grade bitumen was subjected to short-term and long-term ageing simulated by

standard lab ageing methods: Rolling Thin Film Oven Test (RTFOT) and Pressure

Ageing Vessel (PAV). Short-term aging of the samples was conducted as per PN-EN

12607-1 [22], which measures the effect of heat and air on moving film of asphalt binder at 163oC

for 75 minutes with a flow rate of 4 l/min simulate the aging during hot-mix

production and construction. Long-term aging was assessed by PAV as per PN-EN

12

[23]

that uses the

heat of 100oC and pressure of 2.1 MPa for 20 hours. After that, in

Vacuum Degassing Oven, the sample was heated to 170oC for 10

minutes. Then a vacuum of 15 kPa absolute was applied for 30 minutes.

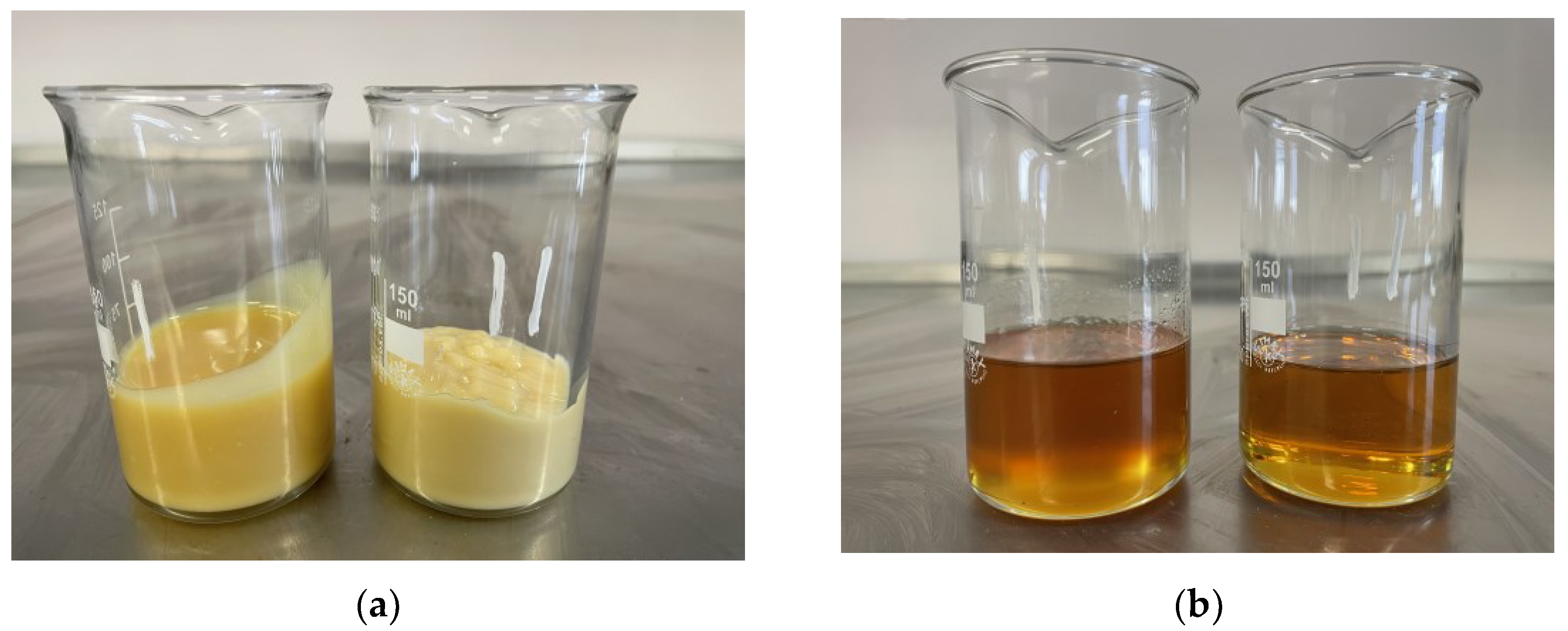

Next, the aged bitumen specimens

were heated up to 170

oC. Once they reached the required temperature,

the analysed rejuvenator (rapeseed imidazoline), pre-heated to 50

oC,

was added at a predetermined rate (

Figure 2).

The application rates were 0% to

8% by the bitumen weight, increased in 2% increments. Then the bitumen was

mixed every 15 minutes for a total period of 45 minutes, during which the

temperature was maintained at a constant level of 170oC. In this

way, homogeneous specimens were obtained, which were subsequently used in the

following tests:

penetration at 25oC (Pen25), as per EN 1426 [24];

softening point with the ring and ball (R&B) method (TR&B), as per EN 1427 [25];

Fraas breaking point (TFraass), as per EN 12593 [26].

In addition, penetration index

(PI) was determined on the basis of the obtained penetration and softening

point values. The above determinations were also done on long-term and

short-term aged and fresh 35/50 bitumen specimens.

As the next step of this research,

aged 35/50 bitumen containing rapeseed imidazoline (added at a pre-determined

rate) was tested for rheological properties. The dynamic shear rheometer (DSR)

test was used to evaluate the changes in the behaviour resulting from the

rapeseed imidazoline addition. The DSR test was carried out as per EN 14770

[27]. In this study, a 8 mm

diameter plate with a gap of 2 mm was used to measure the complex shear modulus

G* and phase angle d. The durability of asphalt pavements depends on a number

of factors, which include the properties of the bitumen used as the binder

[3,4]. In Poland, most pavement

structures consist of bituminous courses (wearing course, binder course and

roadbase) that are laid on an unbound sub-base course. In this arrangement, the

highest tensile strains occur at the bottom of the lowermost bituminous course

(i.e. the roadbase). Therefore, the properties of the bitumen contained in this

layer must be considered relevant. Considering also the origin of RAP and its

suitability for use in the binder course, basecourse and hot-mix asphalt (HMA)

mixtures, most attention was paid to the fatigue resistance assessment of the

bituminous binders in question.

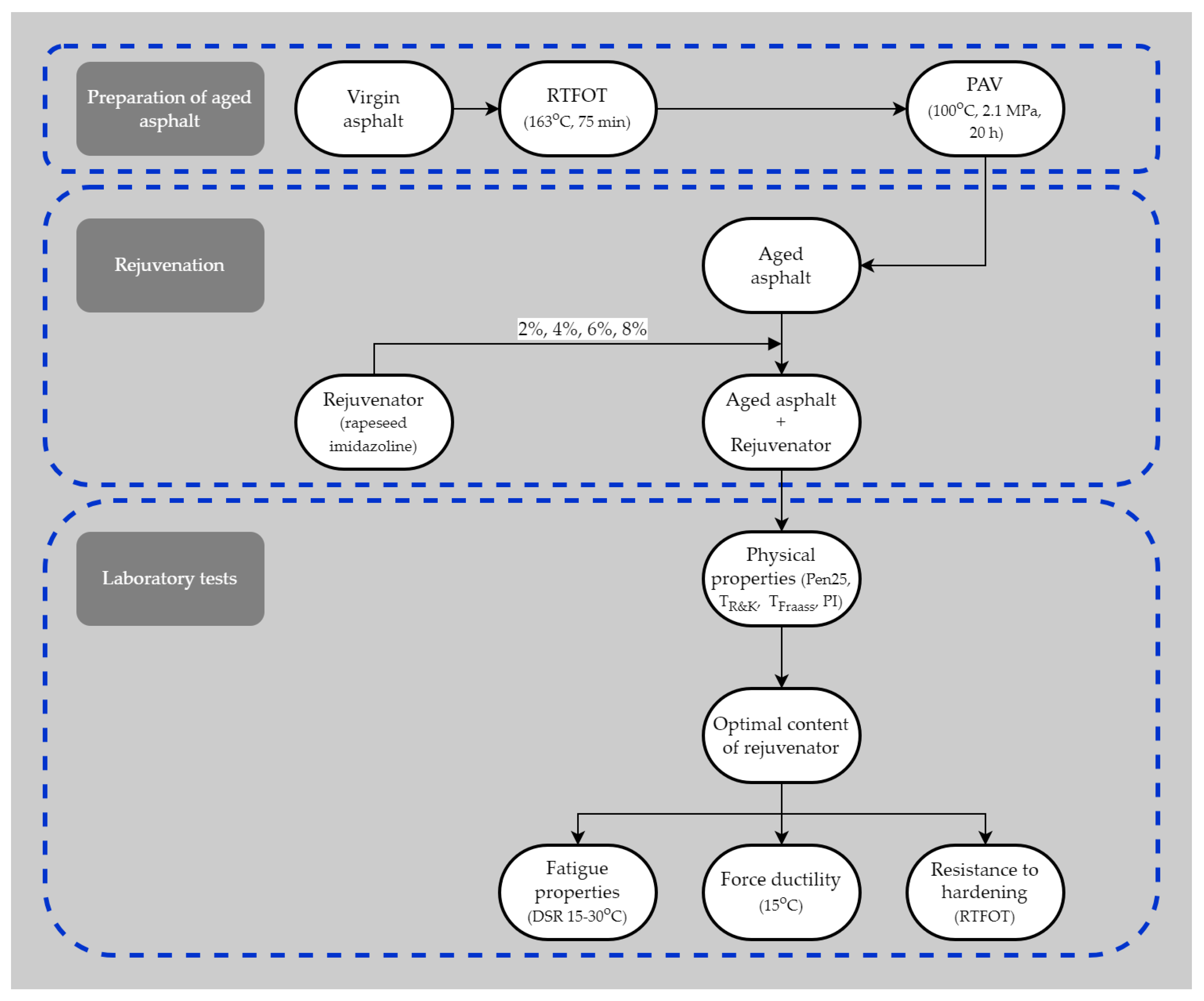

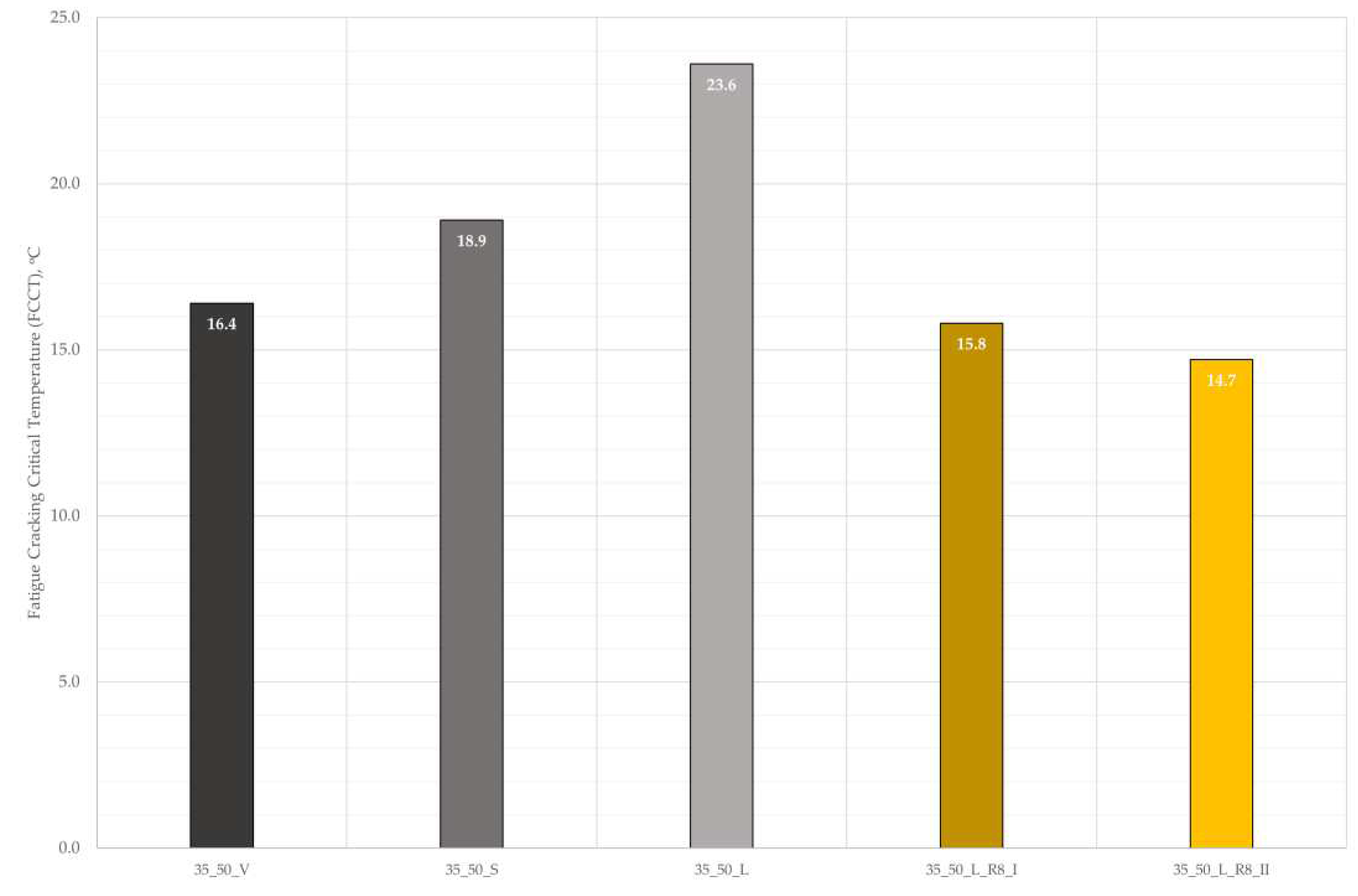

Fatigue Cracking Critical Temperature (FCCT) test was chosen from among a number of available experimental methods used for durability assessment of bituminous binders. The bitumen specimens used in the FCCT test are prepared for testing by RTFOT or RTFOT+PAV accelerated ageing at the intermediate pavement operating temperature. The strains are generally low (1%), induced by loading applied at a frequency of f =10 rad/s. As regards fatigue cracking resistance, the value of G” should be low (indicating lower stiffness of the pavement) and the phase angle should be small (indicating a greater elastic region). As guided by [4,28] the stiffness of the bitumen under analysis, calculated as a product of G* and sind, was limited to a maximum of 5,000 kPa (for standard traffic loading), and to 6,000 kPa (for heavy, very heavy and extremely heavy traffic duty). The reliability of this method, which is based solely on the tested bitumen properties, is questioned due to a lack of sufficient correlation with the fatigue resistance of the bituminous mixtures containing the tested bitumens [28,29]. Still, it may be useful for the purpose of selecting optimum rejuvenating agent and/or evaluating its their efficacy. Noteworthy, the Polish guidelines [19] are limited to evaluating the properties of the old and new bitumen blends solely on the basis of pen value and softening point. The test temperatures in this study ranged from 15oC to 30oC.

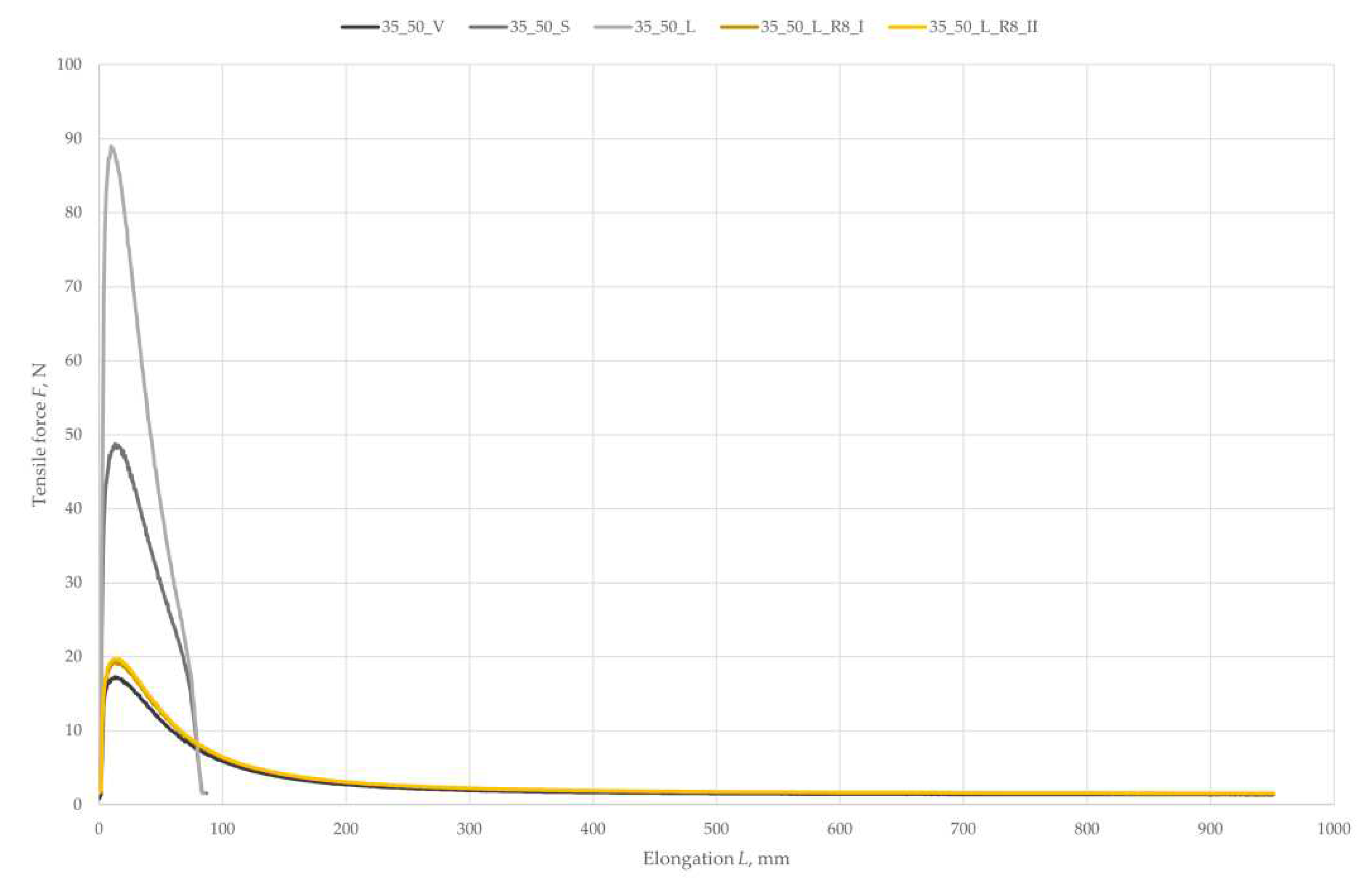

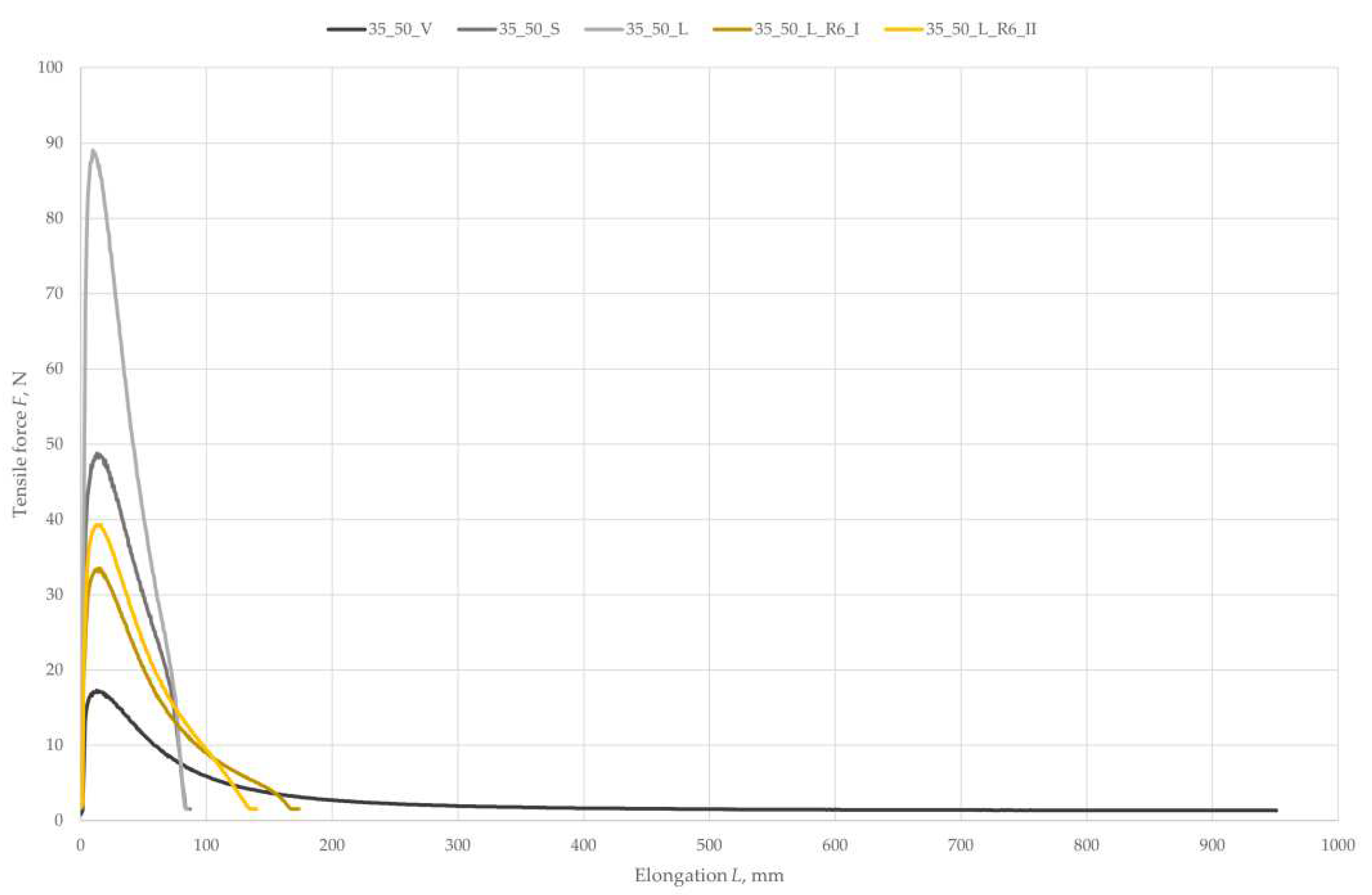

In addition, it was decided to use for assessing the rejuvenating treatment effectiveness the ductilometer test as per EN 13589 [30, from amongst the possible standard testing options. This tests was designed specifically for testing polymer modified bitumen, but the author believes it can have a much wider use in different areas of research. Furthermore, as the approach in which the binder properties are assessed solely on the penetration value and softening point results appeared not appropriate to reliably assess blends of old and new bitumens, the author set out to develop a new assessment method. This is in line with the point made in [31], that in some specific situations it may be necessary to expand the scope of tests for blended bitumens. Having said that, no specific methods are given therein. These above-mentioned situations include higher amoutns of the rejuvenator and RAP applied at a rate of 30% and more. The method proposed in this article appears simple and better suited for routine day-to-day check-ups than the efficient, yet costly dynamic shear rheometer test. Besides, since ductilometer is part of the standard laboratory equipment, the testing laboratories do not need to bear extra cost. In the test proposed in this study, the specimens of 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and aged 35/50 bitumen to which 8% of rapeseed imidazoline had been added, were stretched in the ductilometer at a constant rate of 50 mm per minute. The test was discontinued upon obtaining 950 mm elongation or upon specimen failure, whichever occurred first. The test temperature was 15

oC to ensure that the specimen would not break too early, thus allowing observation of the bitumen behaviour during stretching. The recorded values were then used to determine the ultimate tensile force, elongation and deformation energy. In the author’s opinion, the results are best illustrated by tension curves that graphically represent the relationship between the tensile force and elongation. The experimental program employed in this work is summarized in

Figure 3.

Examples of possible combinations of binder sample determinations are shown in the

Table 2.

3. Results and discussion

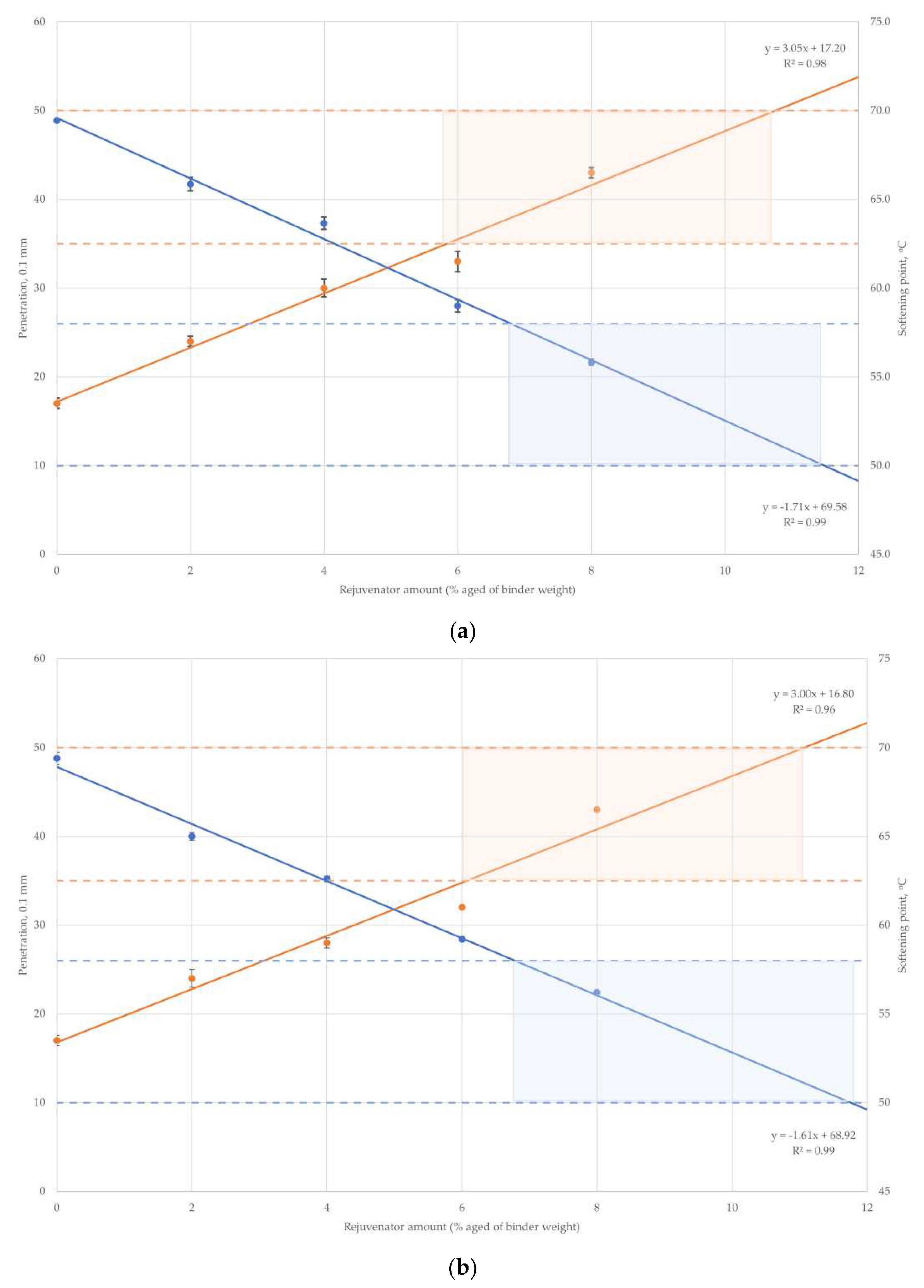

Penetration values indicate the consistency of the bitumen.

Figure 4 shows the effect of the amount of rapedseed imidazoline added to laboratory aged bitumen on its penetration at 25

oC and softening point. Each point on the graph is an arithmetic mean of six penetration values or and four softening point values, as appropriate. The error bars given at each test point were calculated as the standard deviation of the obtained values.

The addition of type 1 or type 2 rapeseed imidazolines to the analysed lab aged 35/50 pen grade bitumens increased penetration at 25oC and decreased the softening point, proportionally to their application rates. Both imidazolines had a similar effect. It is worth to note that the greatest changes among the analysed parameters were observed in penetration, which increased by 152.9% at the maximum imidazoline application rate of 8%. The observed softening point changes were smaller. At 8% application rate, the softening point decreased by ca. 19%, as compared to the softening point of the analysed 35/50 pen-grade bitumen after short-term and long-term lab ageing. The test data showed a linear relationships between the pen and softening point values and the amount of added imidazoline for 0-8% application rates. The relationships between penetration and softening point on the one hand and the imidazoline application rate on the other were described by linear functions. The analysed bitumen satisfied the pen value requirement of the relevant standard for rejuvenator application ranges of 5.8-10.8% of type 1 and 6.1-11.1% of type 2 rapeseed imidazolines resepectively. The softening point requirement given by the standard was, in turn, satisfied by the tested mixtures that contained 6.8-11.5% imidazoline.

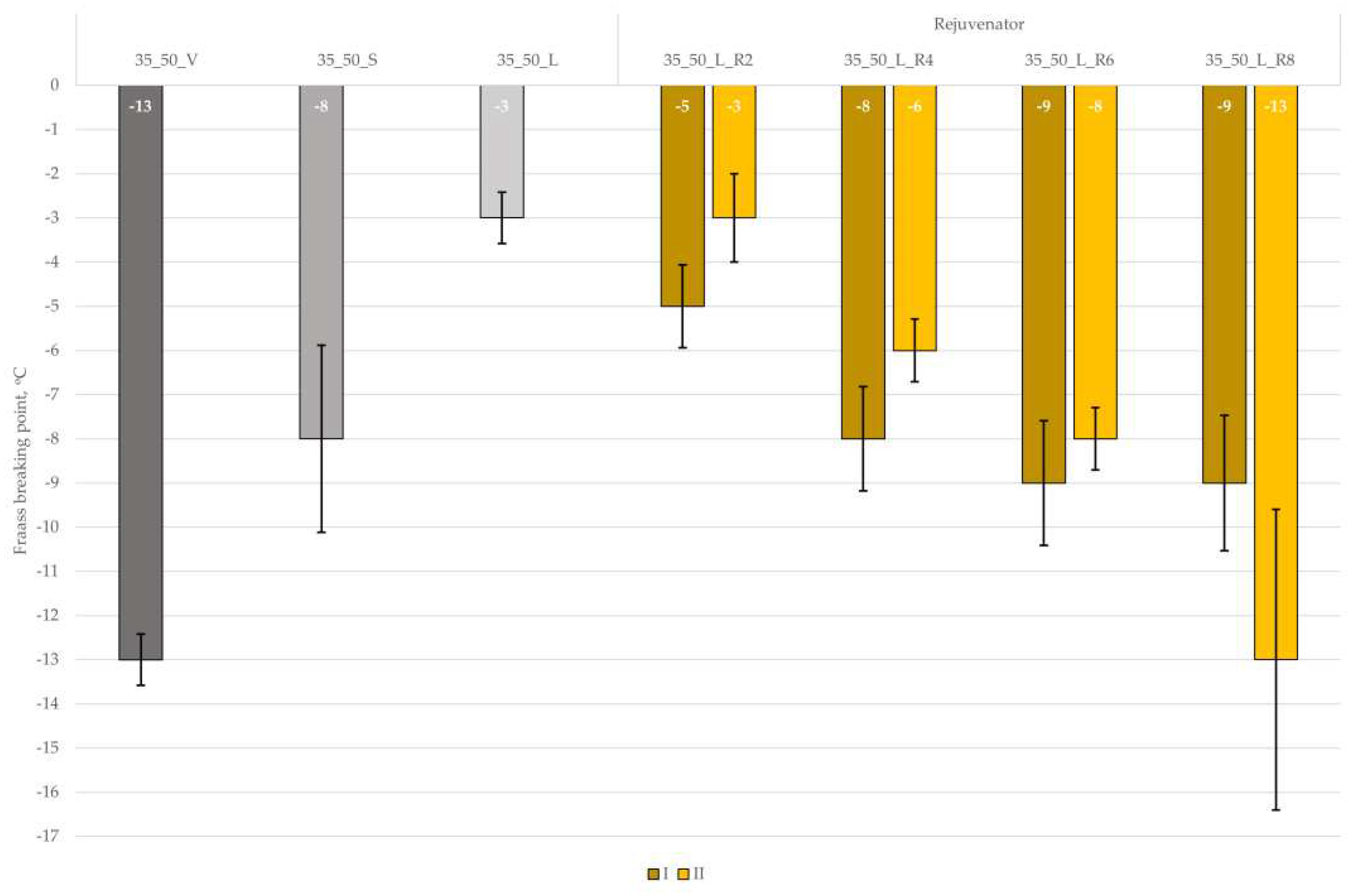

An important aspect of the study was to determine the effect of rapeseed imidazoline on the Fraass breaking point of the analysed 35/50 pen grade bitumen (

Figure 5). This quantity is used to roughly estimate the low-temperature performance of pen grade bitumens. Each point of the curves is an arithmetic mean of three measurements. The error bars given at each test point were calculated as the standard deviation of the obtained values.

Rapeseed imidazoline decreases the Fraas breaking point of aged 35/50 bitumen, proportionally to the application rate. For 8% application rate a decrease by 10oC of this parameter i.e. a change by over 300% was noted.

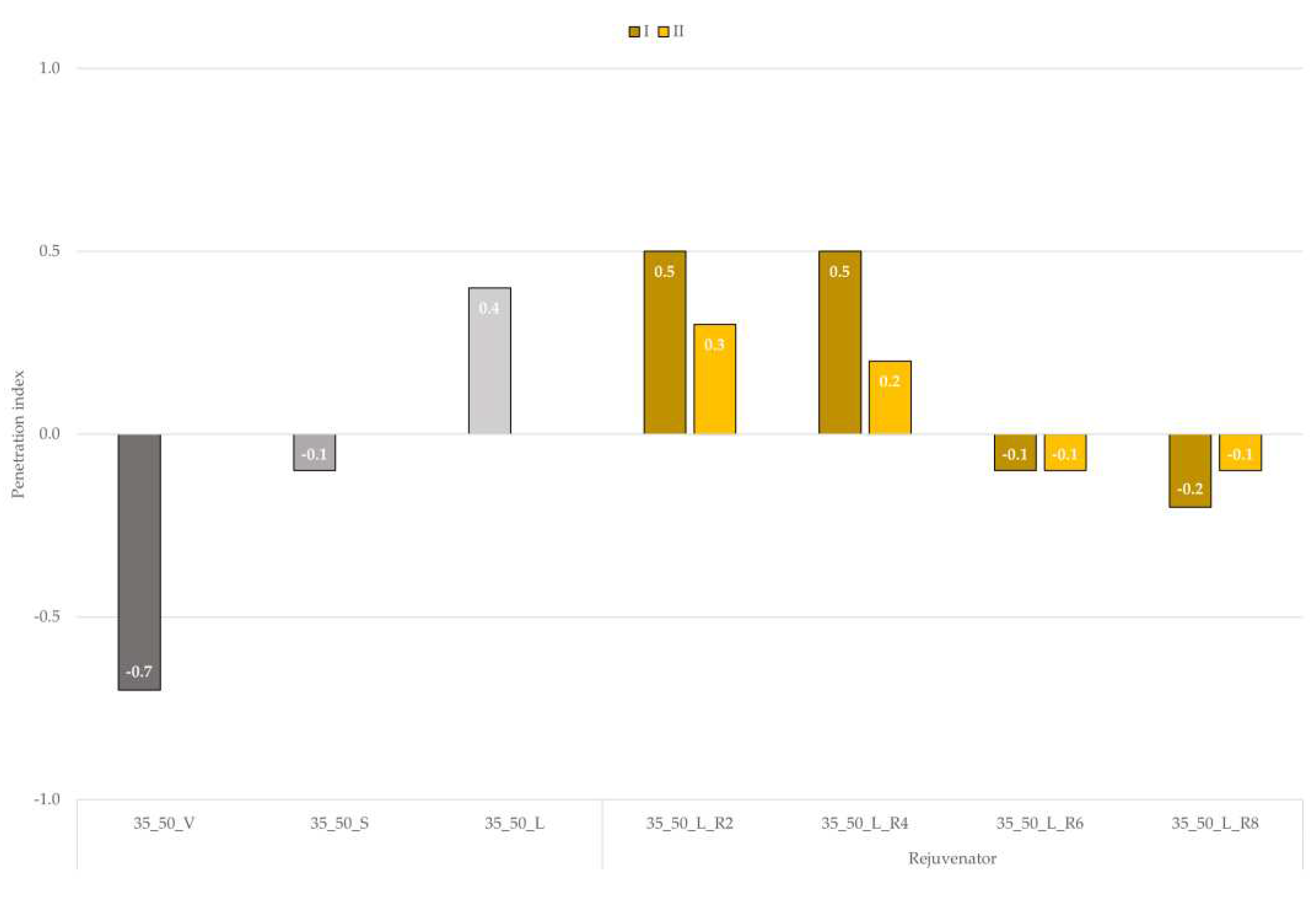

The effect of rapeseed imidazoline addition on the Penetration Index of 35/50 lab aged bitumen is shown in

Figure 6.

As it can be seen, smaller amounts of rejuvenator (2% and 4%) did not cause significant changes in the penetration index. As the amount increased over 4% penetration index started to decrease considerably. Worthwhile noting, the binder remained a sol-gel class material for all the tested application rates.

Now the optimum application rate could be determined, at which the analysed lab aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen would satisfy the penetration value, softening point and Fraas breaking point requirements of the relevant standard(s). Based on the results, 8% application rate was identified as the optimum amount of rapeseed imidazoline added to this bitumen.

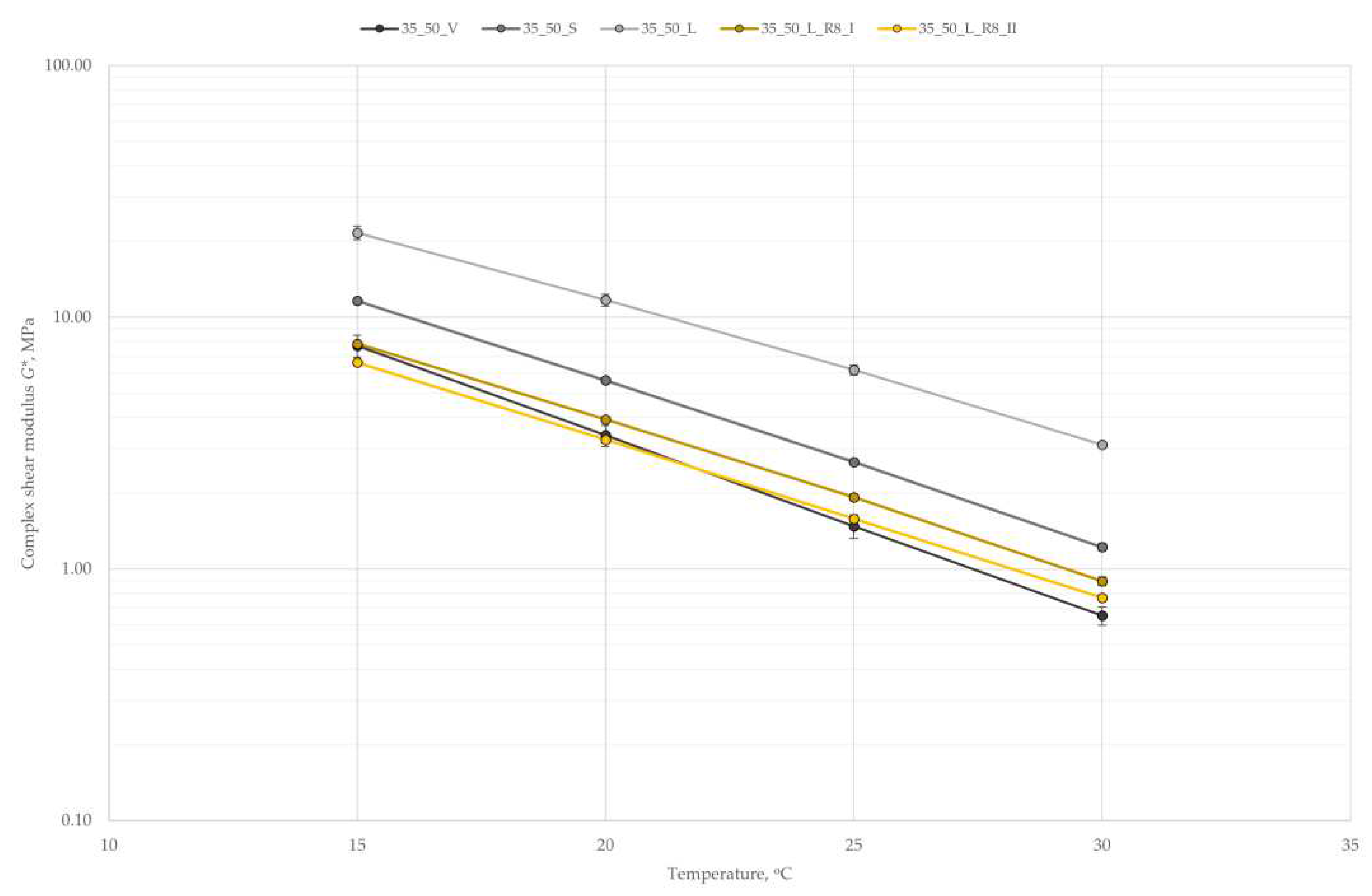

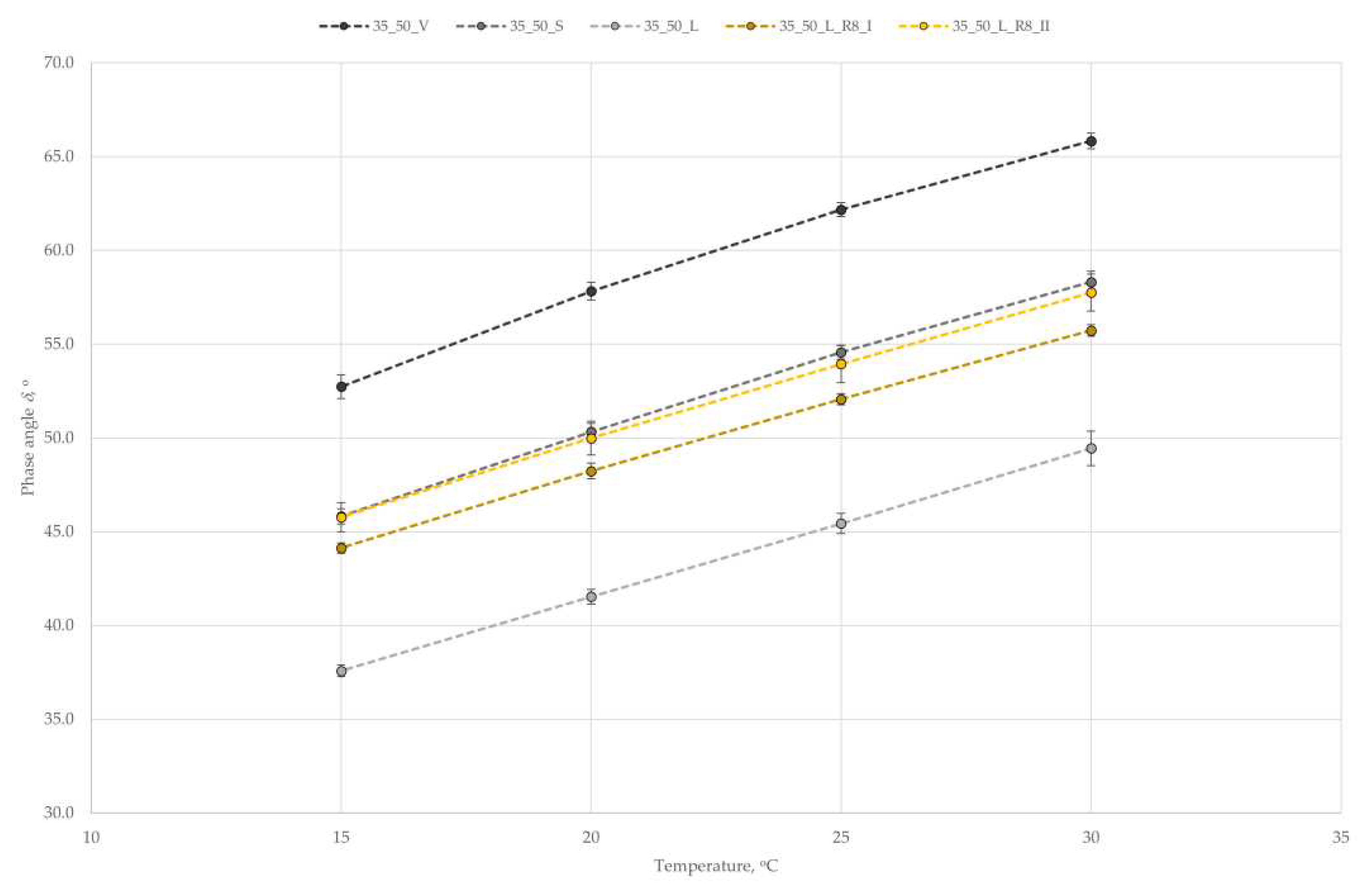

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the relationship between the complex shear modulus G* and phase angle

of the 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and of the lab aged 35/50 bitumen rejuvenated by adding 8% of rapeseed imidazoline. Each point of the curves is an arithmetic mean of two measurements. The error bars given at each test point were calculated as the standard deviation of the obtained values.

As it can be seen, with the increasing temperature the stiffness of bitumen decreases and As it could be expected, ageing increased the stiffness and decreased the phase angle . The rejuvenating treatment with rapeseed imidazoline influenced, of course, the G* and values. The stiffness of aged 35/50 bitumen containing rapeseed imidazoline equalled the stiffness of the same bitumen before ageing. The phase angle was equal to the phase angle of the pure bitumen after short-term lab ageing.

The results of the dynamic shear rheometer test were used to calculate the fatigue cracking critical temperatures (FCCT) for the analysed bitumens, determined at

kPa. The properties at the intermediate temperature are also compared in the

Figure 9. According to [28] the lower the FCCT value, the better the fatigue characteristics of the bitumen, owing to lower increase in stiffness.

The lab ageing (RTFOT+PAV) increased the FCCT value by 7.2oC. Imidazolines type 1 and type 2 were then added at 8% application rate, decreasing the FCCT value by 7.8oC and 8.9oC respectively. Thus, the bitumens containing 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition had the FCCT value, i.e. a quantity used to define the fatigue cracking resistance, even lower than the 35/50 pen grade bitumen before ageing, which may be indicative of a better fatigue performance of the former. This, however, must be verified by appropriate future studies, which may include 4PB-PR four point bending test, to determine the fatigue behaviour of a bituminous mixture containing RAP and rapeseed imidazoline.

The values of the basic parameters obtained in the ductilometer test are compiled in

Table 3. Each value represents the arithmetic average of four measurements. The standard deviation is also given.

The obtained results show that lab ageing had increased the ultimate tensile strength (more than five times), while decreasing, at the same time, the ultimate tensile elongation i.e. causing earlier failure in tension of the stretched specimens. The addition of rapeseed imidazoline improved the bitumen performance in this respect by reducing the ultimate tensile force and increasing the ultimate elongation. On the other hand, no significant differences were observed in the deformation energy values.

Figure 10 shows illustrative curves representing the tensile force values obtained in the ductilometer test at 15

oC.

Analysing the tensile strength vs. elongation curves in

Figure 10 we note large differences in the shapes of the curves depending on the state of bitumen (before/after ageing) and the imidazoline application rate. Nonetheless, all the curves have the same, characteristic shape. In the ductilometer test, the tensile force initially increased, to start decreasing upon reaching 10-20 mm elongation. Also, it is worth noting that ultimate elongation tends to increase with the increasing amount of rapeseed imidazoline added to the bitumen. The desired changes in the analysed parameters (i.e. a decrease of the ultimate tensile force and an increase of the ultimate elongation) due to 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition to the aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen are most pronounced in the tensile force vs. elongation graphs. Note the coincidence of the curves representing the 35/50 pen grade bitumen with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition and 35/50 pen grade bitumen before ageing. This is in line with the findings from the dynamic shear rheometer tests that rapeseed imidazoline addition restores the desired plastic properties of aged pen grade bitumens. An additional ductilometer test was carried out to determine the ultimate tensile force of the aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen containing 6% rapeseed imidazoline addition. The purpose of this last test was to verify the adequacy of the proposed bitumen rejuvenation assessment method. It was found that 6% rapeseed imidazoline addition brings some desired changes to the previously aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen under analysis, including a pronounced increased in the ultimate tensile force, accompanied by a moderate increase in the ultimate elongation. This application rate was not, however, sufficient to fully restore the original plastic behaviour of the tested bitumen (

Figure 11).

This demonstrates adequacy of the method proposed by the author in this article for assessment of the plastic properties of bitumens based on the shape of the relevant force vs. elongation curves. For example, an earlier breaking failure instead of plastic flow may indicate insufficient effectiveness of the applied bitumen rejuvenating treatment.

Table 3 presents the test results of aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen containing 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition, taking into account its resistance to RTFOT short-term ageing.

Based on these results, it can be concluded that the analysed lab aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen containing 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition satisfied all the relevant requirements of PN-EN 12591 [20]. Comparing resistance to ageing, it can be seen that 8% addition of rapeseed imidazoline had a desired effect on the tested 35/50 pen grade bitumen. This is demonstrated by a lower softening point and a lesser penetration drop after ageing, as compared to the same bitumen, yet without the rapeseed imidazoline addition. This confirms the anti-ageing effect of imidazolines, as previously mentioned in the literature [14,15,32,33,34].

Despite the finding of a positive effect of rapeseed imidazoline on the properties of aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen, additional tests should be carried out on HMA mixture containing RAP. In addition, the author also intends to recover the asphalt binder from the mix and evaluate its rheological properties as well as its group composition.

4. Conclusions

The test results and their analysis allow us to conclude that:

Rapeseed imidazoline was found to improve the performance properties of aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen. The more of it was added to the bitumen, the higher was the penetration values and the lower were the softening and breaking point values. At 8% application rate, the performance properties of the tested 35/50 bitumen after lab ageing improved to a level comparable with the same bitumen before ageing, satisfying the standard 35/50 pen grade bitumen specifications. This decrease in penetration and softening point values after short-term ageing (RTFOT method) is also confirmed by the reported improvement in ageing resistance of bitumens.

Rapeseed imidazoline addition was also found to improve the mechanical properties of the tested 35/50 pen grade bitumen after ageing, including complex modulus of elasticity and phase angle. The relevant tests were carried out in a dynamic shear rheometer at the intermediate pavement operating temperature. The tested 35/50 pen grade bitumen rejuvenated by 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition had the stiffness equalling that of the same bitumen not subjected to the lab ageing procedure. The shift angle was the same as obtained for the tested bitumen that was subjected to short-term ageing. The fatigue critical control temperature of the bitumen containing the rejuvenator addition was even lower than the FCCT value of the 35/50 bitumen before ageing, possibly indicating a better anti-ageing effect.

Besides the above-described tests, the effectiveness of bitumen rejuvenating agents may be assessed based on the tension curves representing the tension force values measured in a ductilometer. Comparing the shapes of these curves and the relevant tension curves of the same bitumens before ageing it is possible to find the required rejuvenator application rate and exclude bitumens with unsatisfactory plastic behaviour at low (yet above freezing) temperatures. The main advantage of this assessment method lies in its simplicity. Thus it can be used even in site laboratories, needing no extra testing equipment.

Author Contributions

The author have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jurczak, R. Reclaimed Asphalt – Application Example on the S3 Expressway. Drogownictwo 2021, 6, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bańkowski, W.; Sybilski, D.; Król, J.; Kowalski, K.; Radziszewski, P.; Skorek, P. Use of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement - Necessity and Innovation. Bud. Archit. 2016, 15/1, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefańczyk, B.; Mieczkowski, P. Mineral and Asphalt Mixtures. Performance and Testing, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, 2008; ISBN 978-83-206-1676-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gawel, I.; Kalabińska, M.; Piłat, J. Paving Grade Bitumens, 2nd ed.; Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Łączności: Warszawa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prosperi, E.; Bocci, E. A Review on Bitumen Aging and Rejuvenation Chemistry: Processes, Materials and Analyses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaković, A.; van Vliet, D.; Roetert-Steenbruggen, K.; Leegwater, G. Bio-Oils as Asphalt Bitumen Rejuvenators. Eng. Proc. 2023, 36, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Fan, Q.; Hou, M.; Mi, S.; Yan, X. Effects of Rejuvenator Dosage, Temperature, RAP Content and Rejuvenation Process on the Road Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, S.; Wróbel, M.; Bandura, L.; Woszuk, A.; Franus, W. Use of New Green Bitumen Modifier for Asphalt Mixtures Recycling. Materials 2022, 15, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, M.A.; Zorlu, E.; Çodur, M.Y.; Baş, F.İ.; Yalçın, Ö.; Kuşkapan, E. Investigation of Physical and Chemical Properties of Bitumen Modified with Waste Vegetable Oil and Waste Agricultural Ash for Use in Flexible Pavements. Coatings 2023, 13, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Zou, X.; Cui, C.; Shi, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, F. Performance and Simulation Study of Aged Asphalt Regenerated from Waste Engine Oil. Coatings 2022, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowski, P. Possible Applications of Imidazoline an Asphalt Binders Modifier. J. Civ. Eng. Environemnt Archit. 2016, XXXIII, 63 (1/II/2016), 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczak, R.; Mieczkowski, P.; Budziński, B. Potential of Using Imidazoline in Recycled Asphalt Pavement. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2019, 14, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, M.; Woszuk, A.; Ratajczak, M.; Franus, W. Properties of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement Mixture with Organic Rejuvenator. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweł, I.; Niczke, Ł.; Kosno, J.; Naraniecki, B. Anti-Ageing Additives to Bitumen. Przem. Chem. 2014, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, I.; Czechowski, F.; Kosno, J. An Environmental Friendly Anti-Ageing Additive to Bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 110, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, M.; Kosno, J.; Ratajczak, M.; Zieliński, K. Innovative Additive for Bitumen Based on Processed Fats. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 022060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, M.; Kosno, J. Imidazolines as Modifiers of Asphalts Used in Production of Hydroinsulating Materials. Przem. Chem. 2016, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, K.; Babiak, M. Studies of possible use of oleic imidazoline as modifying agent for hard bitumen. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2015, 61, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Requirements. Asphalt Pavements on National Roads. WT-2 2014 - Part I Asphalt Mixtures. National Roads and Motorways Administration. 2014.

-

PN-EN 12591:2010; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Specifications for Paving Grade Bitumens. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, 2010.

- Bajpai, D.; Tyagi, V.K. Fatty Imidazolines: Chemistry, Synthesis, Properties and Their Industrial Applications. J. Oleo Sci. 2006, 55, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

EN 12607-1:2014; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Determination of the Resistance to Hardening under the Influence of Heat and Air - Part 1: RTFOT Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2014.

-

EN 14769:2012; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Accelerated Long-Term Ageing Conditioning by a Pressure Ageing Vessel (PAV). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2012.

-

EN 1426:2015; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Determination of Needle Penetration. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2015.

-

EN 1427:2015; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Determination of the Softening Point - Ring and Ball Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2015.

-

EN 12593:2015; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Determination of the Fraass Breaking Point. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2015.

-

EN 14770:2012; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Determination of Complex Shear Modulus and Phase Angle - Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2012.

- Błażejowski, K.; Wójcik-Wiśniewska, M.; Baranowska, W.; Ostrowski, P. Bitumen Handbook 2021; ORLEN Asfalt: Płock, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wesołowska, M.; Ryś, D. Analysis of the Fatigue Life of Neat and Modified Bitumens Using Linear Amplitude Sweep Test. Roads Bridg. - Drogi Mosty 2018, 17, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

EN 13589:2018; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders - Determination of the Tensile Properties of Modified Bitumen by the Force Ductility Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, 2018.

-

The Use of Rejuvenators in Hot and Warm Asphalt Production; European Asphalt Pavement Association: Brussels, 2018.

- Zieliński, K.; Babiak, M.; Kosno, J. Effectiveness of Modification of Bitumens Used for Hydroinsulating Masses with Imidazoline. Przem. Chem. 2015, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.; Babiak, M.; Bilski, M.; Zieliński, K.; Kosno, J. Innovative Methods of Bitumen Modification Used in Waterproofing. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 10, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, K.; Babiak, M. Possible Slow-down of the Aging Processes in Bitumens Used in Waterproofing Materials. Mater. Bud. 2013, 6, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The structural formula of imidazoline type 1 (a) and type 2 (b) [14,17].

Figure 1.

The structural formula of imidazoline type 1 (a) and type 2 (b) [14,17].

Figure 2.

Rapeseed imidazolines at the room temperature (a) and at 50oC (b).

Figure 2.

Rapeseed imidazolines at the room temperature (a) and at 50oC (b).

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the study.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the study.

Figure 4.

Penetration and softening temperature of lab aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen, depending on the amount of added rapeseed imidazoline type 1 (a) and type 2 (b).

Figure 4.

Penetration and softening temperature of lab aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen, depending on the amount of added rapeseed imidazoline type 1 (a) and type 2 (b).

Figure 5.

Fraas breaking point of 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after lab ageing, depending on the rapeseed imidazoline application rate.

Figure 5.

Fraas breaking point of 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after lab ageing, depending on the rapeseed imidazoline application rate.

Figure 6.

Penetration index of 35/50 pen grade bitumen vs. rapeseed imidazoline application rate before and after lab ageing.

Figure 6.

Penetration index of 35/50 pen grade bitumen vs. rapeseed imidazoline application rate before and after lab ageing.

Figure 7.

Complex shear modulus G* of the analysed 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and of the lab aged 35/50 bitumen rejuvenated with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition.

Figure 7.

Complex shear modulus G* of the analysed 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and of the lab aged 35/50 bitumen rejuvenated with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition.

Figure 8.

Phase angle of the analysed 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and of the lab aged 35/50 bitumen rejuvenated with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition

Figure 8.

Phase angle of the analysed 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and of the lab aged 35/50 bitumen rejuvenated with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition

Figure 9.

FCCT of 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and 35/50 pen grade bitumen containing 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition, determined at kPa.

Figure 9.

FCCT of 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and 35/50 pen grade bitumen containing 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition, determined at kPa.

Figure 10.

Tensile force vs. elongation curves for 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and aged 35/50 bitumen containing 8% of rapeseed imidazoline.

Figure 10.

Tensile force vs. elongation curves for 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and aged 35/50 bitumen containing 8% of rapeseed imidazoline.

Figure 11.

Tensile force vs. elongation curves for 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and aged 35/50 bitumen containing 6% of rapeseed imidazoline.

Figure 11.

Tensile force vs. elongation curves for 35/50 pen grade bitumen before and after ageing and aged 35/50 bitumen containing 6% of rapeseed imidazoline.

Table 1.

Properties of 35/50 pen grade bitumen.

Table 1.

Properties of 35/50 pen grade bitumen.

| Properties |

Test Results |

Technical Requirements according [20] |

| Penetration at 25oC (0.1 mm) |

42 |

35 ÷ 50 |

| Softening point (oC) |

53.6 |

50 ÷ 58 |

| Mass change (%) |

0.09 |

≤ 0.5 |

| Retained penetration (%) |

67 |

≥ 53 |

| Increase of softening point (oC) |

7.4 |

≤ 8.0 |

| Fraass breaking point (oC) |

-13 |

≤ -5 |

| Penetration Index |

-0.7 |

-1.5 ÷ +0.7 |

Table 2.

Kinds of asphalt binders with their symbols.

Table 2.

Kinds of asphalt binders with their symbols.

| Symbols |

Compositions |

| 35_50_V |

35/50 pen grade bitumen before ageing (virgin) |

| 35_50_S |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT (short-term aging) |

| 35_50_L |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV (long-term aging) |

| 35_50_L_R2 |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV with 2% rejuvenator |

| 35_50_L_R4 |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV with 4% rejuvenator |

| 35_50_L_R6 |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV with 6% rejuvenator |

| 35_50_L_R8 |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV with 8% rejuvenator |

| 35_50_L_R8_I |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV with 8% rapeseed imidazoline type 1 addition |

| 35_50_L_R8_II |

35/50 pen grade bitumen after RTFOT and PAV with 8% rapeseed imidazoline type 2 addition |

Table 3.

Ultimate tensile strength values obtained in ductilometer test at 15oC.

Table 3.

Ultimate tensile strength values obtained in ductilometer test at 15oC.

| Samples |

Maximum tensile force Fmax [N] |

Maximum elongation Lmax [mm] |

Strain energy E [J] |

| 35_50_V |

17,28±2,21 |

9501

|

2,71±0,79 |

| 35_50_S |

48,80±2,02 |

84,2±15,2 |

2,62±0,63 |

| 35_50_L |

89,62±2,28 |

83,6±18,1 |

4,05±0,46 |

| 35_50_L_R8_I |

19,30±2,10 |

9501

|

3,01±0,41 |

| 35_50_L_R8_II |

19,68±1,92 |

9501

|

3,07±0,67 |

Table 4.

Parameters of aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition.

Table 4.

Parameters of aged 35/50 pen grade bitumen with 8% rapeseed imidazoline addition.

| Properties |

Test Results |

Technical Requirements according [20] |

| 35_50_L_R8_I |

35_50_L_R8_II |

| Penetration at 25oC (0.1 mm) |

43 |

43 |

35 ÷ 50 |

| Softening point (oC) |

55.8 |

56.2 |

50 ÷ 58 |

| Mass change (%) |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

≤ 0.5 |

| Retained penetration (%) |

72 |

81 |

≥ 53 |

| Increase of softening point (oC) |

5.1 |

3.1 |

≤ 8.0 |

| Fraass breaking point (oC) |

-9 |

-13 |

≤ -5 |

| Penetration Index |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

-1.5 ÷ +0.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).