Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

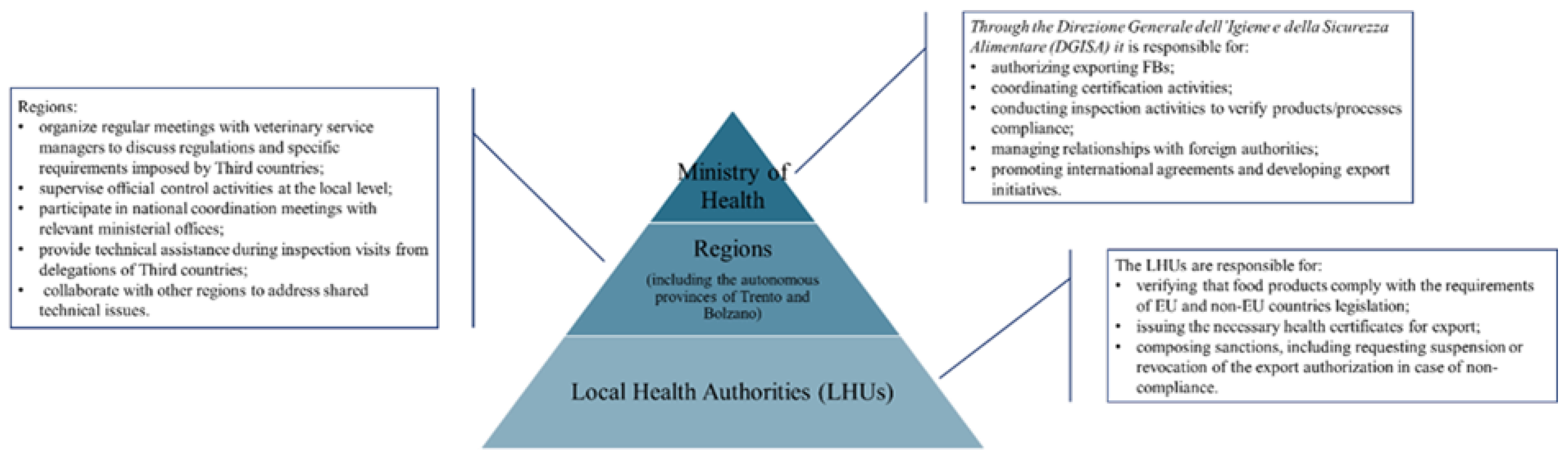

1. Introduction

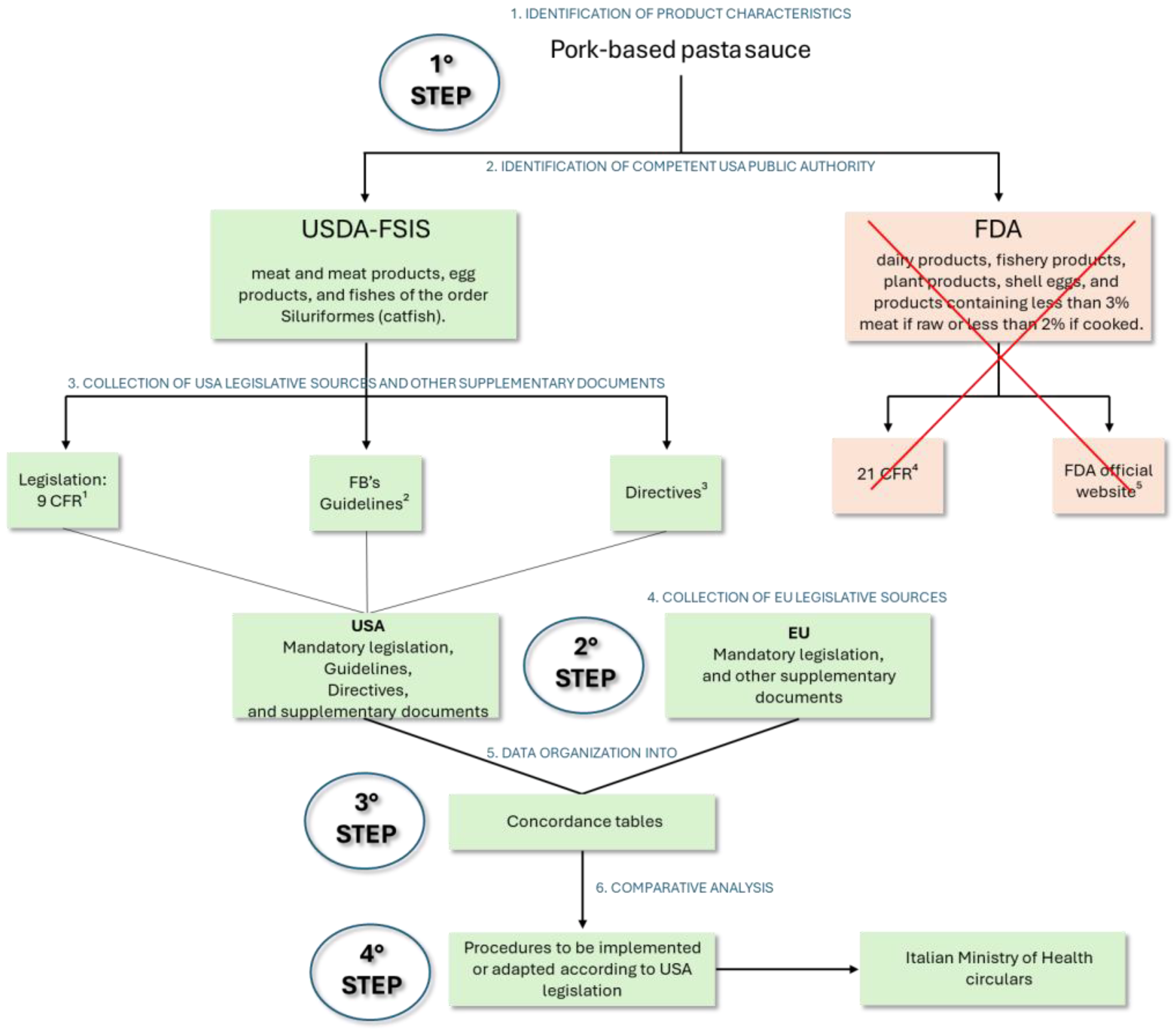

2. Materials and Methods

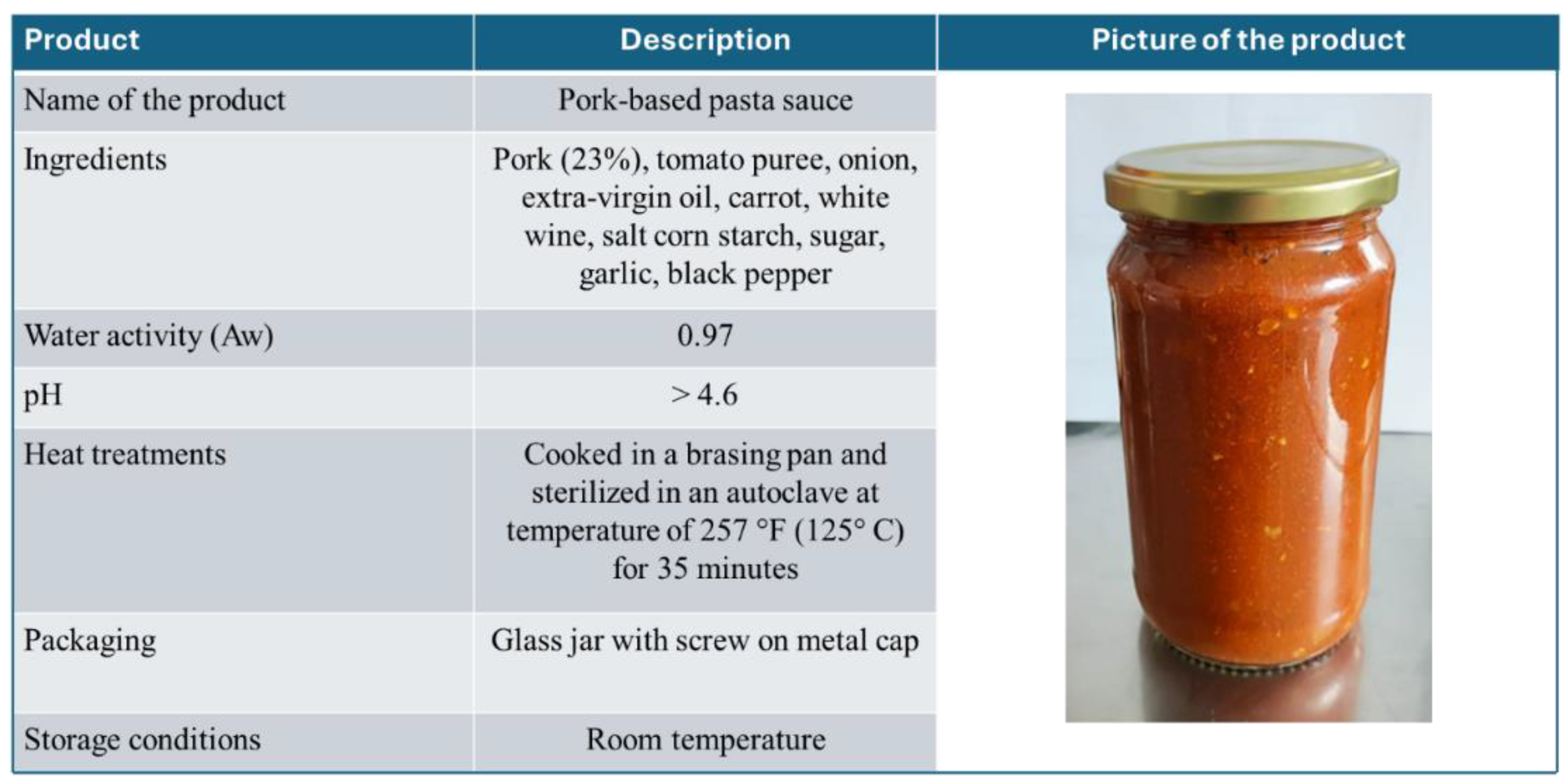

2.1. Analysis of the Production Plant and the Product to Be Exported

2.2. Regulatory Source Collection

2.3. Comparative Analysis and FSMS Alignment

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. USA and EU Legislation Collection and Analysis

3.1.1. USA Mandatory Legislation, Guidelines and Other Supplementary Documents

3.1.2. EU Mandatory Legislation, Guidelines and Other Supplementary Documents

3.2. Ministerial Circulars Collection and Analysis

3.3. Procedures to Be Implemented or Adapted for the Inclusion in the USA List of Authorized Establishments

3.4. SSOPs

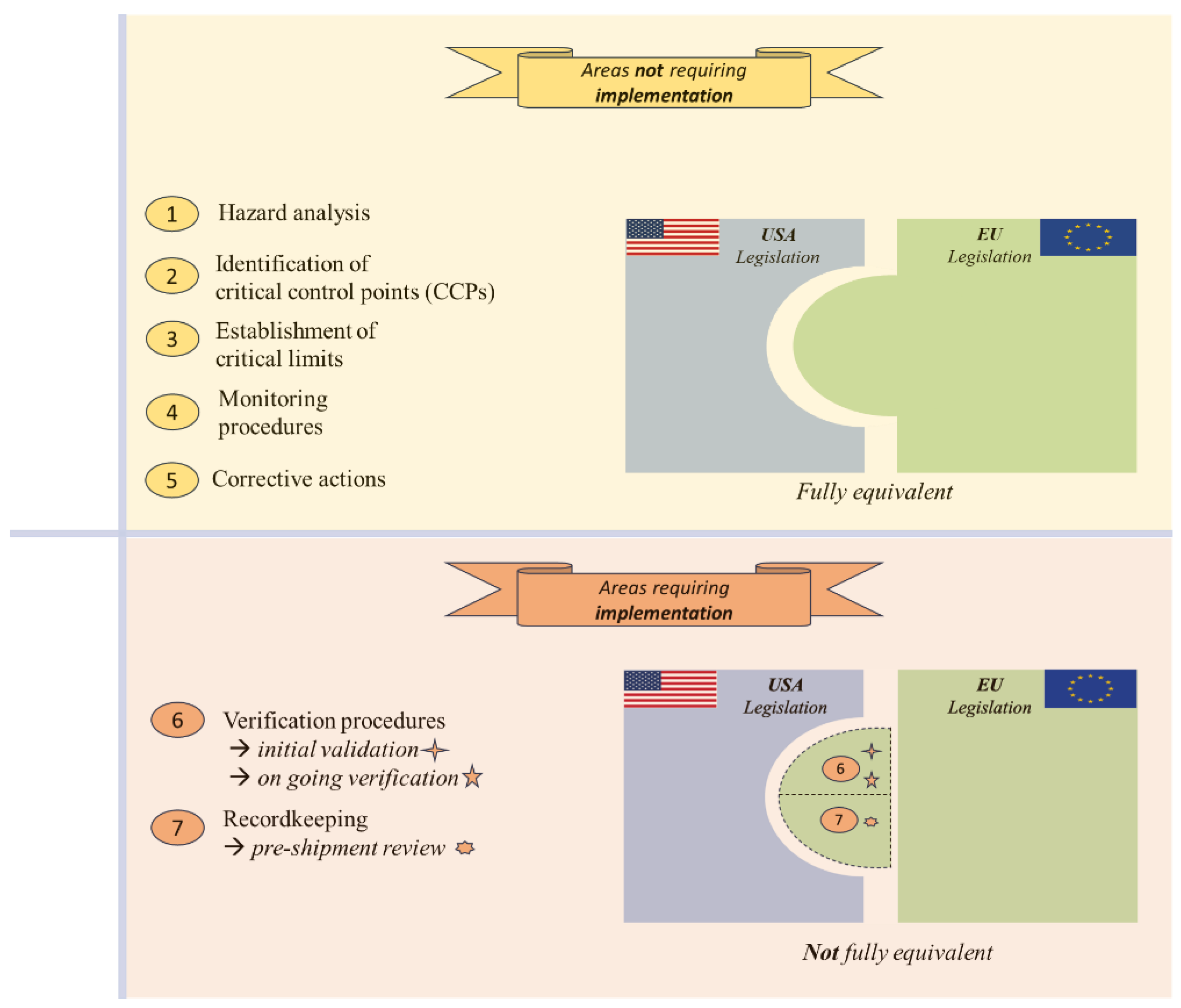

3.5. HACCP System

3.5.1. Areas Not Requiring Implementation

3.5.2. Areas Requiring Implementation: Verification Procedures (Principle 6) and Recordkeeping (Principle 7)

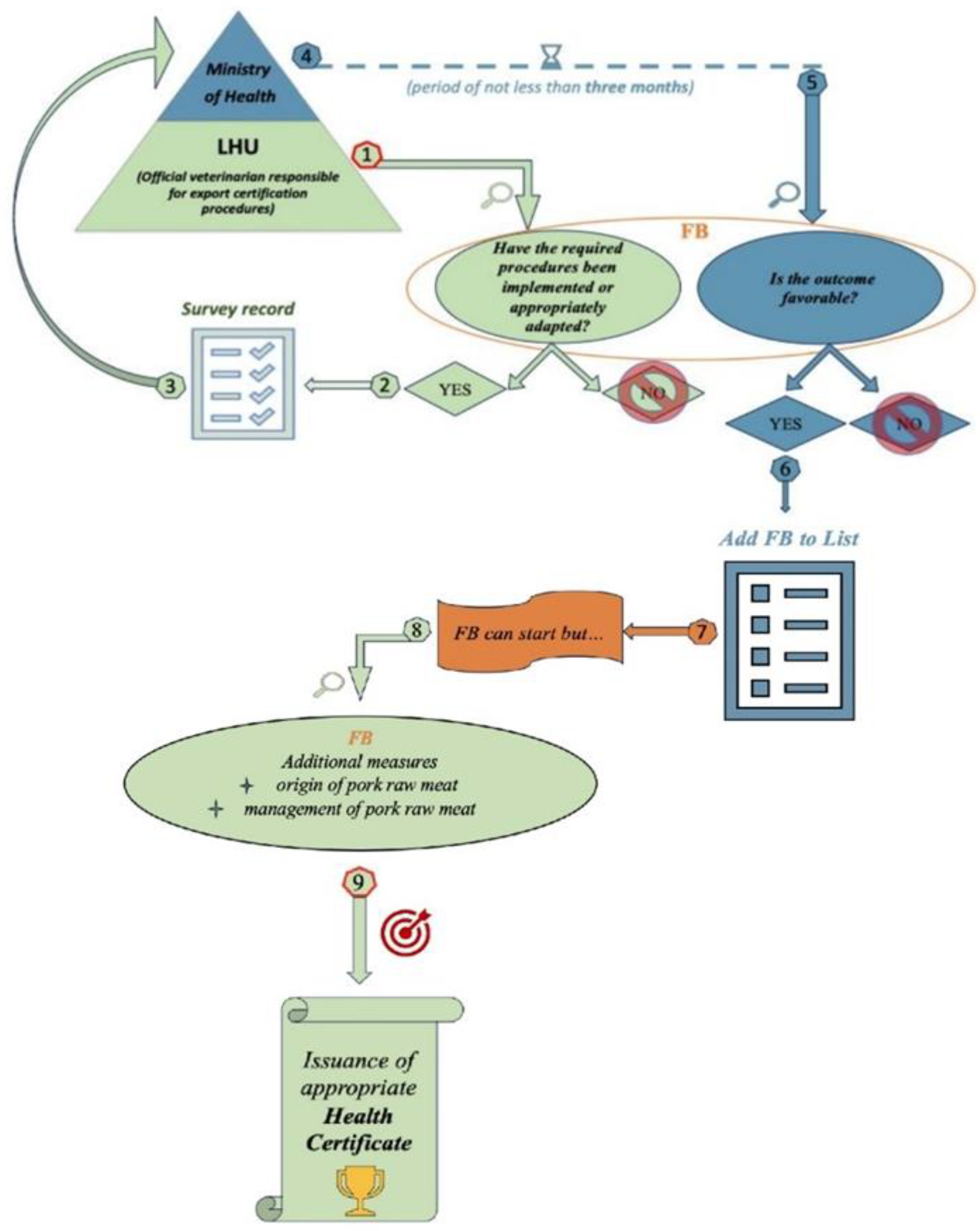

3.6. Export Authorization Process: Procedural and Operational Barriers and Support Strategies for Small and Medium-Sized Italian Fbs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APHIS | Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service |

| CA | Competent Authority |

| CFR | Code of Federal Regulations |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| EC | European Commission |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FBs | Food businesses |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FSIS | Food Safety and Inspection Service |

| FSMS | Food Safety Management System |

| HACCP | Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points |

| IPP | Inspection Program Personnel |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LHU | Local Health Unit |

| PRPs | Prerequisite Programs |

| SMEs | Small and medium-sized enterprises |

| SPS | Sanitary and Phytosanitary |

| SSOPs | Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures |

| TPCS | Thermally processed and commercially sterile |

| USA | United States of America |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WOAH | World Organization for Animal Health |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

References

- Carbone, A., & Henke, R. Recent trends in agri-food Made in Italy exports. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 32. [CrossRef]

- Malorgio, G., Grazia, C., & Camanzi, L. International trade regulation and food safety: the case of Italian imports of fruit and vegetables from Southern Mediterranean countries. Riv. Econ. Agrar. 2016, 71, 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Othmani, A., el Weriemmi, M., & Bakari, S. Effect of food exports on economic growth: fresh insights from Italy. J. Dev. Econ. 2024, 9, 185–216. [CrossRef]

- Remondino, M., & Zanin, A. Logistics and agri-food: digitization to increase competitive advantage and sustainability. Literature review and the case of Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 787. [CrossRef]

- Consiglio per la ricerca in agricoltura e l’analisi dell’economia agraria, Commercio con l’estero dei prodotti agroalimentari 2022. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/web/politiche-e-bioeconomia/-/rapporto-commercio-estero-prodotti-agroalimentari (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Consiglio per la ricerca in agricoltura e l’analisi dell’economia agraria, Comunicato Crea-agritrend, Agroalimentare, II trimestre 2024. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/-/agroalimentare-ii-trimestre-2024-buon-andamento-dell-export-8-2%25- (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Istituto di servizi per il mercato agricolo alimentare. Report - Scambi con l’estero. La bilancia agroalimentare italiana nel I semestre 2024. Available online: https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/13265 (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Antoci, S., Iannetti, L., Centorotola, G., Acciari, V. A., Pomilio, F., Daminelli, P., Romanelli, C., Ciorba, A. B., Santini, N., Torresi, M., Ruolo, A., Castoldi, F., Pierantoni, M., Noè, P., & Migliorati, G. Monitoring Italian establishments exporting food of animal origin to third countries: SSOP compliance and Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. contamination. Food Control 2021, 121, 107584. [CrossRef]

- Herzfeld, T., Drescher, L. S., & Grebitus, C. Cross-national adoption of private food quality standards. Food Policy 2011, 36, 401–411. [CrossRef]

- Neeliah, S. A., Neeliah, H., & Goburdhun, D. Assessing the relevance of EU SPS measures to the food export sector: evidence from a developing agro-food exporting country. Food Policy 2013, 41, 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Neri, D., Antoci, S., Iannetti, L., Ciorba, A. B., D’Aurelio, R., del Matto, I., di Leonardo, M., Giovannini, A., Prencipe, V. A., Pomilio, F., Santarelli, G. A., & Migliorati, G. EU and US control measures on Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. in certain ready-to-eat meat products: An equivalence study. Food Control 2019, 96, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for on the hygiene of foodstuffs, 853/2004/CE. In: Official Journal, L 139/55, 30/04/2004.

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs, 852/2004/CE. In: Official Journal, L 139/1, 30/04/2004.

- General principles of food hygiene. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXC%2B1-1969%252FCXC_001e.pdf (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety, 178/2002/CE. In: Official Journal, L 31/1, 01/02/2002.

- 2022/C 355/01 Commission Notice on the implementation of food safety management systems covering Good Hygiene Practices and procedures based on the HACCP principles, including the facilitation/flexibility of the implementation in certain food businesses. In Official Journal, C 355, 16/09/2022.

- Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products, 2017/625/EU. In: Official Journal, L 95/1, 07/04/2017.

- Linee guida operative per l’attività di certificazione per l’esportazione di animali e prodotti da parte delle autorità competenti. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_6.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=1156&area=sicurezzaAlimentare&menu=esportazione (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Trade agreements. Available online: https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/it/content/accordi-commerciali (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Engler, A., Nahuelhual, L., Cofré, G., & Barrena, J. How far from harmonization are sanitary, phytosanitary and quality-related standards? An exporter’s perception approach. Food Policy 2012, 37, 162–170. [CrossRef]

- Principles for food import and export inspection and certification. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/pt/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXG%2B20-1995%252FCXG_020e.pdf (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- World Organization for Animal Health. Terrestrial Animal Health Code. Available online: https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-code-online-access/ (Accessed on 25 February 2025).

- World Trade Organization. Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/sps_e.htm (Accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Decreto legislativo 2 Febbraio 2021, n. 27. Disposizioni per l’adeguamento della normativa nazionale alle disposizioni del regolamento (UE) 2017/625 ai sensi dell’articolo 12, lettere a), b), c), d) ed e) della legge 4 ottobre 2019, n. 117. (21G00034).

- Amorena, A. L. Le regole per l’esportazione dei prodotti alimentari. Rassegna di Diritto, Legislazione e Medicina Legale Veterinaria 2011, 10.

- Esportazione verso Stati Uniti. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_6.jsp?id=1157&area=sicurezzaAlimentare&menu=esportazione (Accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Osservatorio sulla giurisprudenza amministrativa. Available online: https://www.ildirittoamministrativo.it/archivio/allegati/OSSERVATORIO%20AMMINISTRATIVO%20AL%2031%20OTTOBRE%202010%20A%20CURA%20DI%20MARIANNA%20CAPIZZI.pdf (Accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Principles and guidelines for national food control systems. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/pt/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXG%2B82-2013%252FCXG_082e.pdf (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Teixeira, S., & Sampaio, P. Food safety management system implementation and certification: survey results. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. 2013, 24, 275-293. [CrossRef]

- Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. In: Official Journal, L 124, 20/05/2003.

- Allender, H. D., Buchanan, S., Abdelmajid, N., Arnold, I., Tankson, J., & Carter, J. M. Procedure for microbiological baseline surveys conducted by US Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service. Food Control 2020, 111, 107083. [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, R. G., Kalinowski, R. M., Bodnaruk, P. W., Eifert, J. D., Boyer, R. R., Duncan, S. E., & Bailey, R. H. Incidence of Listeria spp. in ready-to-eat food processing plant environments regulated by the U.S. Food Safety and Inspection Service and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. J. Food Prot.2018, 81, 1063–1067. [CrossRef]

- Hooker, N. H., Teratanavat, R. P., & Salin, V. Crisis management effectiveness indicators for US meat and poultry recalls. Food Policy 2005, 30, 63–80. [CrossRef]

- Food & Drug Administration. Investigations operations manual 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/inspection-references/investigations-operations-manual (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Bruno, F. Il diritto alimentare nel contesto globale: USA e UE a confronto; Cedam: Padova, Italy, 2017; pp. 1-464.

- Keener, K. M. (2019). Food Regulations. In Handbook of Farm, Dairy and Food Machinery Engineering, Kutz, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States; pp. 15-44.

- Food Safety and Inspection Service. Directive & Notices - Regulations, Directives, Notices, and policy decisions enable FSIS to carry out its mission of protecting public health. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/policy/directives-notices (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Consiglio di Stato, Sezione III, Sentenza 26 ottobre 2016, n. 4478. Available online: https://www.eius.it/giurisprudenza/2016/415 (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Altalex - circolari interpretative: sussiste giurisdizione del giudice amministrativo. Available online: https://www.altalex.com/documents/news/2012/10/09/circolari-interpretative-sussiste-giurisdizione-del-giudice-amministrativo (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Catelani, A. Le circolari amministrative, Key Editore: Milan, Italy, 2021; pp. 1-202.

- Ministerial circular DGISAN 0015006-P-14/04/2016. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=0&codLeg=54662&parte=1%20&serie= (Accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Ministerial circular DGISAN 0010140-P-17/03/2017. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2017&codLeg=61644&parte=1%20&serie=null (Accessed on 24 February 2025).

- 9 CFR part 416. Sanitation. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/part-416 (Accessed on 19 February 2025).

- 9 CFR part 417. Hazard Analysis And Critical Control Point (HACCP) systems. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/part-417 (Accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Ministerial circular DGISAN 0040602-24/10/2018. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2019&codLeg=71974&parte=1%20&serie=null (Accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Ministerial circular DGISAN 0015012-P-14/04/2016. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2016&codLeg=54661&parte=1%20&serie= (Accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 laying down health rules as regards animal by-products and derived products not intended for human consumption and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1774/2002 (Animal by-products Regulation). In: Official Journal, L 300/1, 14/11/2009.

- 9 CFR part 301. Terminology; adulteration and misbranding standards. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/part-301 (Accessed on 19 February 2025).

- 9 CFR part 314. Handling and disposal of condemned or other inedible products at official establishments. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/part-314 (Accessed on 19 February 2025).

- dos Santos, D. A., Nunes, F. L., da Silva, K. O., Lobo, C. M. O., Alfieri, A. A., & Ribeiro-Júnior, J. C. Effects of industrial slicing on the microbiological quality and safety of mozzarella cheese and ham. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101144. [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.-L. G., & Sandoval, A. Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures (SSOPs). In Food Safety Engineering; Demirci, A., Feng, H., Krishnamurthy, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 175-190.

- Ribeiro Júnior, J. C., Dias, B. P., Nascimento, A. L. do, Silva, J. P. C., Rosa, F. C., & Lobo, C. M. de O. Effects of washing sanitation standard operating procedures on the microbiological quality and safety of cattle carcasses. Food Control 2024, 166, 110745. [CrossRef]

- Agüeria, D. A., Libonatti, C., & Civit, D. Cleaning and disinfection programmes in food establishments: a literature review on verification procedures. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A., & Al-Mahmood, O. Food safety programs that should be implemented in slaughterhouses: Review. J. Appl. Vet. Sci. 2023, 8, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. H., & Pierce, P. D. The Use of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). In Handbook of Hygiene Control in the Food Industry, 2nd ed; Lelieveld, H., Holah, J., Gabrić, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, Cambridge, England, 2016; pp. 221-233.

- Food Safety and Inspection Service. Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/2021-02/13_SSOP_student.pdf (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Linee guida sui criteri per la predisposizione dei piani di autocontrollo per l’identificazione e la gestione dei pericoli negli stabilimenti che trattano alimenti di origine animale, di cui al Regolamento (CE) n. 853/2004. Available online: http://archivio.statoregioni.it/DettaglioDocf641.html?IdProv=10987&tipodoc=2 (Accessed on 14 July 2025).

- FSIS-GD-2020-0009. A Sanitation Standard Operating Procedure model. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/guidelines/2020-0009 (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Wallace, C. A., & Mortimore, S. E. HACCP. In Handbook of Hygiene Control in the Food Industry; Lelieveld, H., Holah, J., Gabrić, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, Cambridge, England, 2016; pp.25-42.

- Ngure, F. M., Makule, E., Mgongo, W., Phillips, E., Kassim, N., Stoltzfus, R., & Nelson, R. Processing complementary foods to reduce mycotoxins in a medium scale Tanzanian mill: a hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) approach. Food Control 2024, 162, 110463. [CrossRef]

- Radu, E., Dima, A., Dobrota, E. M., Badea, A.-M., Madsen, D. Ø., Dobrin, C., & Stanciu, S. Global trends and research hotspots on HACCP and modern quality management systems in the food industry. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18232. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. Food safety management systems: requirements for any organization in the food chain. Geneva.

- Jongwanich, J. The impact of food safety standards on processed food exports from developing countries. Food Policy 2009, 34, 447-457. [CrossRef]

- FSIS-GD-2020-0008. Guidebook for the preparation of HACCP plans. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/guidelines/2020-0008 (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- 9 CFR part 431. Thermally processed, commercially sterile products. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/part-431 (Accessed on 19 February 2025).

- FSIS-GD-2021-0010. Food Safety and Inspection Service. HACCP model for Thermally processed, commercially sterile product. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/2021-08/FSIS-GD-2021-0010_0.pdf (Accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Food Safety and Inspection Service. Microbiology of thermally processed commercially sterile and shelf-stable meat and poultry products. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/2021-03/VTP_Reference_Material.pdf (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Anderson, N. M., Larkin, J. W., Cole, M. B., Skinner, G. E., Whiting, R. C., Gorris, L. G. M., Rodriguez, A., Buchanan, R., Stewart, C. M., Hanlin, J. H., Keener, L., & Hall, P. A. Food safety objective approach for controlling Clostridium botulinum growth and toxin production in commercially sterile foods. J. Food Prot. 2011, 74, 1956–1989. [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs. In: Official Journal, L 338/1, 22/12/2005.

- Code of hygienic practice for low and acidified low acid canned foods. CAC/RCP 23–1979. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXC%2B23-1979%252FCXC_023e.pdf (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Food and Agricolture Organization of the United Nations. Canning principles. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/R6918E/R6918E02.htm (Accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Opinion of the Scientific Panel on biological hazards (BIOHAZ) related to Clostridium spp in foodstuffs. EFSA Journal 2005, 3. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Martinez, M., Fearne, A., Caswell, J. A., & Henson, S. Co-regulation as a possible model for food safety governance: opportunities for public–private partnerships. Food Policy 2007, 32, 299–314. [CrossRef]

- Glowicz, J., Benowitz, I., Arduino, M. J., Li, R., Wu, K., Jordan, A., Toda, M., Garner, K., & Gold, J. A. W. Keeping health care linens clean: underrecognized hazards and critical control points to avoid contamination of laundered health care textiles. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 1178–1181. [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for the validation of food safety control measures. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXG%2B69-2008%252FCXG_069e.pdf (Accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Food Safety and Inspection Service. Thermally processed products FSA tool VS3. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/2020-08/Thermally-Processed.pdf (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Thermal processing commercially sterile self-paced training course. Available online: https://fsistraining.fsis.usda.gov/pluginfile.php/18440/mod_resource/content/1/TPSP%20Student%20Guide%20Edits12092021.pdf (Accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Manning, L. Development of a food safety verification risk model. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 575–589. [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, L., Carr, C., & Schmidt, R. H. Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) Principle 7: establish record keeping and documentation procedures. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 80, 3449-3452.

- Stabilimenti autorizzati all’export di prodotti di origine animale verso gli Stati Uniti d`America. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/consultazioneStabilimenti/ConsultazioneStabilimentiServlet?ACTION=gestioneSingoloPaese&naz=US (Accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Ministerial circular DGISAN 0010382-24/03/2020. Available online: https://www.aulss7.veneto.it/index.cfm?method=mys.apridoc&iddoc=7523 (Accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Ministerial circular DGISAN 0015423-12/04/2022. Available online: https://www.aulss7.veneto.it/index.cfm?method=mys.apridoc&iddoc=7751 (Accessed on 25 February 2025).

- 9 CFR part 94. Foot-and-Mouth Disease, Newcastle Disease, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, African Swine Fever, Classical Swine Fever, Swine Vesicular Disease, and Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy: prohibited and restricted importations. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-9/part-94 (Accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Lee, J. C., Neonaki, M., Alexopoulos, A., & Varzakas, T. Case studies of small-medium food enterprises around the world: Major constraints and benefits from the implementation of food safety management systems. Foods 2023, 12(17), 3218. [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Parthasarathy, S., & Gupta, P. Exporting challenges of SMEs: A review and future research agenda. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 327-342. [CrossRef]

| United States of America | ||

| Mandatory legislation | 9 CFR part 301 “Terminology; adulteration and misbranding standards”. 9 CFR part 314 “Handling and disposal of condemned or other inedible products at official establishments”. 9 CFR part 416 “Sanitation”. 9 CFR part 417 “Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point systems”. 9 CFR part 431 “Thermally processed, commercially sterile products”. |

|

| Guidelines | FSIS-GD-1999-0003 “Update - 416.2(g): water supply and water, ice, and solution reuse”. FSIS-GD-2016-0003 “Sanitation performance standards compliance guide”. FSIS-GD-2018-0005 “Meat and poultry hazard and control guide”. FSIS-GD-2020-0008 “Guidebook for the preparation of HACCP plans”. FSIS-GD-2020-0009 “A Sanitation Standard Operating Procedure model”. FSIS-GD-2021-0010 “HACCP model for Thermally processed, commercially sterile product”. |

|

| Directives | FSIS Directive 5000.1 (REV8) “Verifying an establishment’s food safety system”. FSIS Directive 5000.4 (REV 3) “Performing the pre-operational Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures verification task”. FSIS Directive 7530.1 (Rev 4) “Handling a process deviation or abnormal container of thermally processed, commercially sterile canned product”. FSIS Directive 7530.2 (REV 1) “Verification activities in canning operations that choose to follow the canning regulations”. |

|

| Supplementary documents | Microbiology of thermally processed commercially sterile and shelf-stable meat and poultry product (2005). Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures (2019). Thermally processed products FSA tool VS3 (2020). Thermal processing commercially sterile self-paced training course (2021). |

|

| European Union | ||

| Mandatory legislation | Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs. Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 laying down health rules as regards animal by-products and derived products not intended for human consumption and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1774/2002 (Animal by-products Regulation). Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products. |

|

| Supplementary documents | 2022/C 355/01 Commission Notice on the implementation of food safety management systems covering Good Hygiene Practices and procedures based on the HACCP principles, including the facilitation/flexibility of the implementation in certain food businesses. EFSA Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Biological Hazards on the request from the Commission related to Clostridium spp. in foodstuffs (2005). |

|

| Ministerial circulars | |

| Documents | Description |

| DGISAN 0015006-P-14/04/2016 Export to the United States of America of food of animal origin and food containing products of animal and plant origin (composite products). |

The ministerial circular clarifies the responsibilities of the US public authorities (USDA and FDA) for ensuring food safety and hygiene. |

| DGISAN 0015012-P-14/04/2016 Procedure for registration in the USDA-FSIS list of establishments authorized to export to the United States of America. |

It offers detailed instructions on the procedures to follow for inclusion in the list of establishments authorized to export food products to the United States. |

| DGISAN 0010140-P-17/03/2017 Official control at establishments on the list of Italian facilities authorized for the export of food products under USDA-FSIS jurisdiction in the USA - REV 1. |

It is specific guidance on the methods and responsibilities of official controls at establishments authorized to export to the United States. The objective is to verify the compliance of facilities and products with the requirements established by bilateral agreements between Italy and the USA, ensuring the maintenance of equivalence between US and EU systems. |

| DGISAN 0040602-24/10/2018 Export to the USA of “thermally processed-commercially sterile” products. |

It provides guidance on the official control of products classified as “thermally processed commercially sterile” that are exported to the USA. In addition, it offers useful guidance to Food Business Operators (FBOs) on managing HACCP plans and implementing corrective actions required in case of nonconformities affecting the product, the heat treatment process, or the container. |

| DGISAN 0010382-24/03/2020 Start of exports to the United States of America of composite products falling within the scope of the USDA and classified as Not Ready to Eat (NRTE) (composite products containing pork-based ingredients). |

The circular establishes that the FB must ensure that the raw materials used for products intended for export to the United States come from authorized sources and are accompanied by the necessary health documentation certifying their suitability for export. |

| DGISAN 0015423-12/04/2022 Clarification on the use of USDA-health certificates for exports to the US of pork and pork products. |

The circular provides clarification on the use of USDA health certificates required for exporting pork and pork products to the United States (US C01 + annex E, US-C02, or US-C03). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.