1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the most common and serious complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus, representing a leading cause of blindness worldwide. It is estimated that around 30% of people with diabetes show signs of DR, with a proportion below 10% developing sight-threatening lesions, such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy and/or diabetic macular oedema [

1,

2,

3].

By 2045, the global number of patients with diabetic retinopathy is projected to reach 160.5 million, with an estimated 44.82 million at risk of vision loss [

4].

The Diabetic Retinopathy Barometer Study revealed significant gaps in patient education, healthcare professional training, and access to affordable treatment. These challenges are particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries and among minority populations, where the burden of disease remains highest [

5].

A growing number of studies suggest that individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age may have a heightened susceptibility to developing diabetic retinopathy [

6].

Screening for diabetic retinopathy is essential for early detection and the prevention of disease progression to more advanced stages. Common screening methods include fundus examination through direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy, the use of retinal cameras, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging [

7].Diabetic retinopathy is classified into several stages, ranging from non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, based on the presence of microvascular abnormalities and neovascularization.

The treatment of diabetic retinopathy varies depending on the severity of the disease. In its early stages, strict control of blood glucose, blood pressure, and lipid levels can slow the progression of the condition. In advanced stages, treatment options include laser therapy for retinal photocoagulation, intraocular injections with anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) agents, and vitrectomy.

Sudoscan is a non-invasive device that measures sweat gland function by assessing the electrochemical conductance of the skin, providing valuable insights into peripheral autonomic health. Its use in the context of diabetes mellitus has been recently investigated to determine whether it may offer an advantage in the early identification of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of Sudoscan in detecting diabetic microvascular complications. One study evaluated the performance of Sudoscan in screening for microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes and found it to be a potentially effective tool for identifying asymptomatic diabetic neuropathy, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy [

8].

This study aims to examine the efficacy of Sudoscan in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes by analyzing the data obtained from the enrolled patient cohort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

This cross-sectional study was conducted between June 2019 and June 2020 at a single clinical center and included 271 patients. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Nicolae Malaxa Clinical Hospital in Bucharest, Romania (approval number 2145). Data were collected in accordance with the hospital’s standard of care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). All participants provided written informed consent for the collection and use of their medical data for research purposes. Patients were recruited from the Diabetes Department of the Nicolae Malaxa Clinical Hospital.

2.2. Study Population

Inclusion criteria were: patients attending outpatient consultations or hospitalized in the Diabetes Department during the study period, age >18 years, overweight or obese individuals, confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, and signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included: refusal to sign informed consent, presence of other diabetes types (type 1, latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood, MODY), patients aged 18 or younger, pregnancy, history of malignancy in the past five years, prior stroke, history of myocardial infarction, lower limb amputations, chronic kidney disease predating the diagnosis of diabetes, and neuropathy due to other causes (e.g., alcoholism, vitamin B12 deficiency). Patients with stroke sequelae were excluded to avoid potential false positives in sensitivity testing and Sudoscan results. Patients with recent malignancies were excluded due to the risk of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Amputees were excluded since Sudoscan testing cannot be performed in such cases.

2.3. Clinical Assessment

Anthropometric data collected included height, weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, blood pressure in supine and standing positions, and heart rate in supine and standing positions, as well as smoking status.

2.4. Biochemical Parameters

Venous plasma samples were collected after an 8-hour fast to assess: fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), serum creatinine, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, bilirubin, C-reactive protein, potassium, magnesium, chloride, sodium, calcium, urea, AST, ALT, and GGT. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the MDRD equation. The ACR was determined from spot urine samples.

2.5. Assessment of Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) was assessed by ophthalmological examination. Fundus examination was performed by a single ophthalmologist. The eye with more severe pathology was used for classification. DR was categorized as non-proliferative or proliferative. Patients with no such abnormalities were considered free of retinopathy.

2.6. Assessment of Peripheral Diabetic Neuropathy

Peripheral diabetic neuropathy was evaluated using the Toronto Clinical Scoring System, sudomotor function, and lower limb sensitivity testing. The Toronto protocol is validated against sural nerve biopsy and correlates well with electrophysiological testing. Symptoms such as pain, numbness, paresthesia, weakness, and upper limb involvement were recorded. Achilles and patellar reflexes were tested. Instrumental evaluations included temperature perception using TipTherm, pressure sensitivity using the 10 g Semmes-Weinstein monofilament, vibratory sensation with the Rydel-Seiffer tuning fork, and pain sensitivity using pinprick testing and the Neuropen.

2.7. Assessment of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

CKD was classified based on eGFR and ACR. CKD was defined as eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m². Microalbuminuria was defined as ACR 30–300 mg/g and macroalbuminuria as ACR >300 mg/g.

2.8. Assessment of Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy (CAN)

CAN was assessed using QTc interval from ECG and cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests (CARTs), including heart rate variability, Valsalva maneuver, orthostatic testing, and isometric exercise blood pressure response. The ESP-01-PA Ewing tester was used. Sudoscan also integrates algorithms combining electrochemical skin conductance with age to estimate CAN risk (Sudoscan-CAN score).

2.9. Evaluation of Sudomotor Function

Sudoscan is an FDA-approved non-invasive device used to assess sudomotor function by analyzing sweat gland activity in the hands and feet. The procedure involves placing the hands and feet on electrodes for approximately three minutes. A low electrical stimulus activates the sweat glands, and the electrochemical response is measured. The device provides useful information about autonomic nervous system function and is applicable in evaluating diabetic neuropathy and CKD. It integrates electrochemical skin conductance data with demographic and clinical factors (e.g., age, height, weight, HbA1c) to generate risk scores for nephropathy (Sudoscan-Nephro) and CAN (Sudoscan-CAN). The procedure is fast, painless, and requires no special preparation.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (Released 2011; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Statistical significance was set at a 95% confidence level. ANOVA was used to compare quantitative variables across groups, and the χ² test for categorical variables. To estimate the independent correlation between diabetic retinopathy and Sudoscan scores, multiple linear regression was applied. Non-normally distributed variables were log10-transformed to meet the assumptions of parametric testing.

3. Results

Patients were divided into three categories based on the presence and severity of diabetic retinopathy: without diabetic retinopathy (DR−), with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), and with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). The results revealed statistically significant differences across several variables (

Table 2.1).

For example, the mean age differed significantly between groups (p = 0.038), with patients in the NPDR group being generally older than those in the PDR group. The duration of diabetes was also significantly longer in patients with retinopathy (NPDR and PDR) compared to those without retinopathy (DR−) (p < 0.001). Regarding body mass index (BMI), significantly higher values were observed in the PDR group (p = 0.043), suggesting a potential association between retinopathy severity and obesity.

Metabolic parameters and renal function showed notable differences. Although blood glucose and HbA1c levels did not differ significantly between groups, the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) was significantly higher in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (p = 0.032), indicating more pronounced renal impairment in this group.

Clinical scores used to assess nerve damage (Toronto Score, Ewing Score, and Sudoscan Score) were significantly higher in patients with retinopathy, reflecting greater severity of neuropathic involvement in these groups (p < 0.001).

Both the Toronto and Ewing scores demonstrated significant intergroup differences, suggesting a strong correlation between these clinical indices and the presence of diabetic retinopathy.

Table 2.1.

Clinical Characteristics and Biochemical Parameters Stratified by the Presence and Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy.

Table 2.1.

Clinical Characteristics and Biochemical Parameters Stratified by the Presence and Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy.

| |

DR - |

NDR |

RDR |

Total |

|

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

P-value |

| Age (years) |

60.96 |

9.25 |

63.48 |

8.76 |

58.14 |

6.72 |

61.59 |

9.07 |

0.038 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) |

6.35 |

4.93 |

11.33 |

6.39 |

13.71 |

6.40 |

8.26 |

6.06 |

<0.001 |

| Height (cm) |

165.71 |

9.17 |

165.96 |

9.70 |

164.64 |

8.65 |

165.73 |

9.28 |

0.885 |

| Weight (kg) |

87.42 |

16.98 |

89.89 |

15.42 |

95.43 |

17.70 |

88.60 |

16.61 |

0.154 |

| BMI (kg/m²) |

31.80 |

5.42 |

32.61 |

4.66 |

35.31 |

6.85 |

32.23 |

5.32 |

0.043 |

| SBP in supine position (mmHg) |

132.68 |

17.84 |

137.77 |

18.33 |

134.21 |

20.90 |

134.34 |

18.24 |

0.110 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) |

182.25 |

81.81 |

198.56 |

82.20 |

215.21 |

111.07 |

189.01 |

83.83 |

0.167 |

| HbA1c (%) |

7.99 |

2.01 |

8.22 |

1.51 |

8.59 |

1.66 |

8.09 |

1.85 |

0.382 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

201.04 |

56.26 |

193.62 |

53.13 |

186.08 |

50.81 |

198.01 |

55.03 |

0.435 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) |

49.77 |

13.31 |

51.81 |

13.66 |

50.00 |

12.47 |

50.42 |

13.36 |

0.518 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) |

112.31 |

49.11 |

103.25 |

49.99 |

105.43 |

42.71 |

109.11 |

49.09 |

0.378 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

212.65 |

151.46 |

222.65 |

139.97 |

171.43 |

79.65 |

213.59 |

145.11 |

0.471 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) |

79.67 |

22.44 |

73.04 |

28.38 |

70.86 |

28.81 |

77.16 |

24.89 |

0.083 |

| UACR (mg/g) |

47.51 |

192.81 |

71.34 |

112.03 |

198.93 |

524.38 |

62.68 |

203.59 |

0.032 |

| Toronto Score |

5.01 |

3.03 |

7.27 |

2.66 |

8.79 |

3.93 |

5.91 |

3.21 |

<0.001 |

| Ewing Score |

3.02 |

2.03 |

4.32 |

1.96 |

4.57 |

2.34 |

3.51 |

2.12 |

<0.001 |

| Sudoscan Nephropathy Score |

68.38 |

16.28 |

57.93 |

13.07 |

64.57 |

14.16 |

64.93 |

15.93 |

<0.001 |

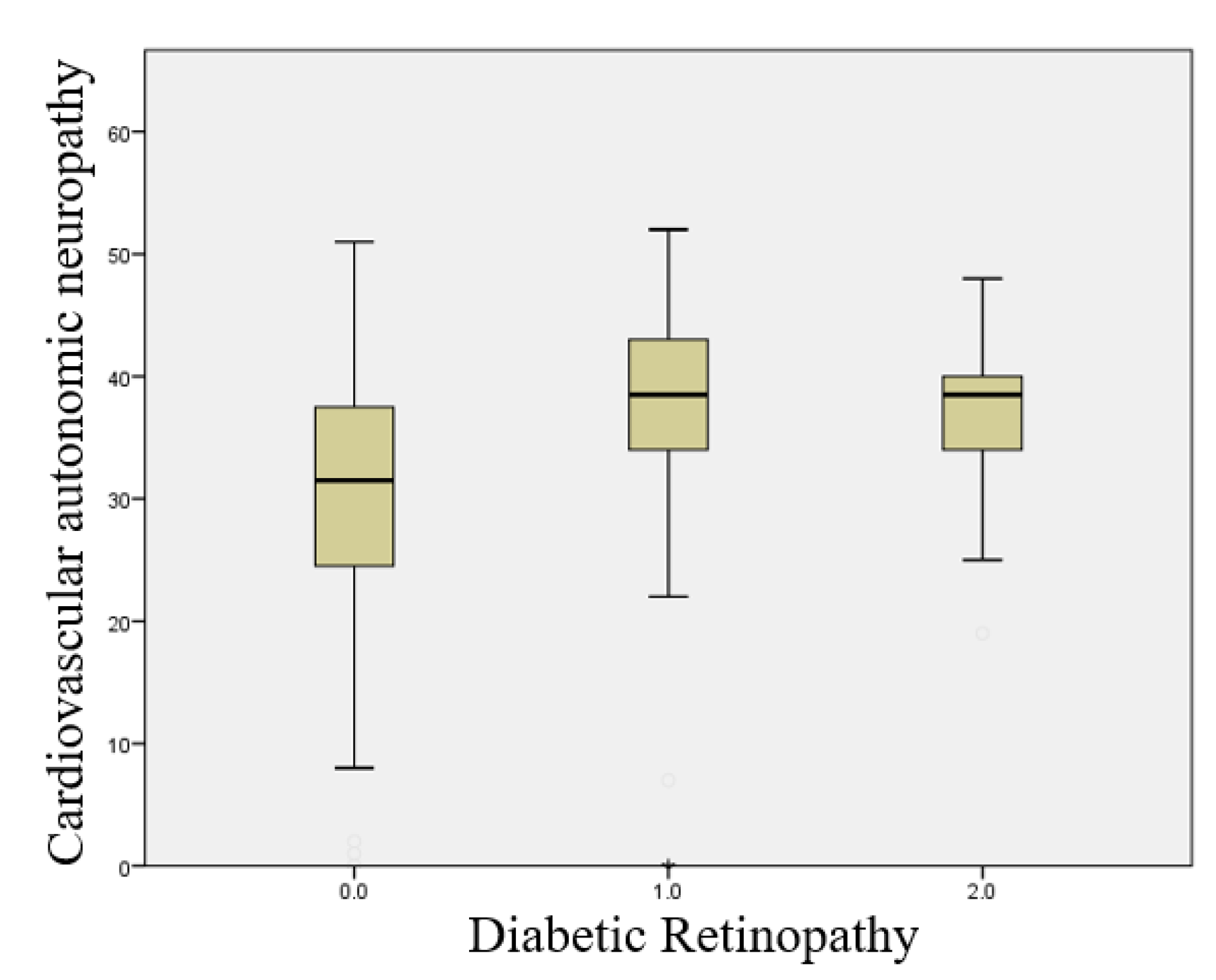

| Sudoscan CAN Score |

31.16 |

9.84 |

37.44 |

8.17 |

37.07 |

7.76 |

33.42 |

9.70 |

<0.001 |

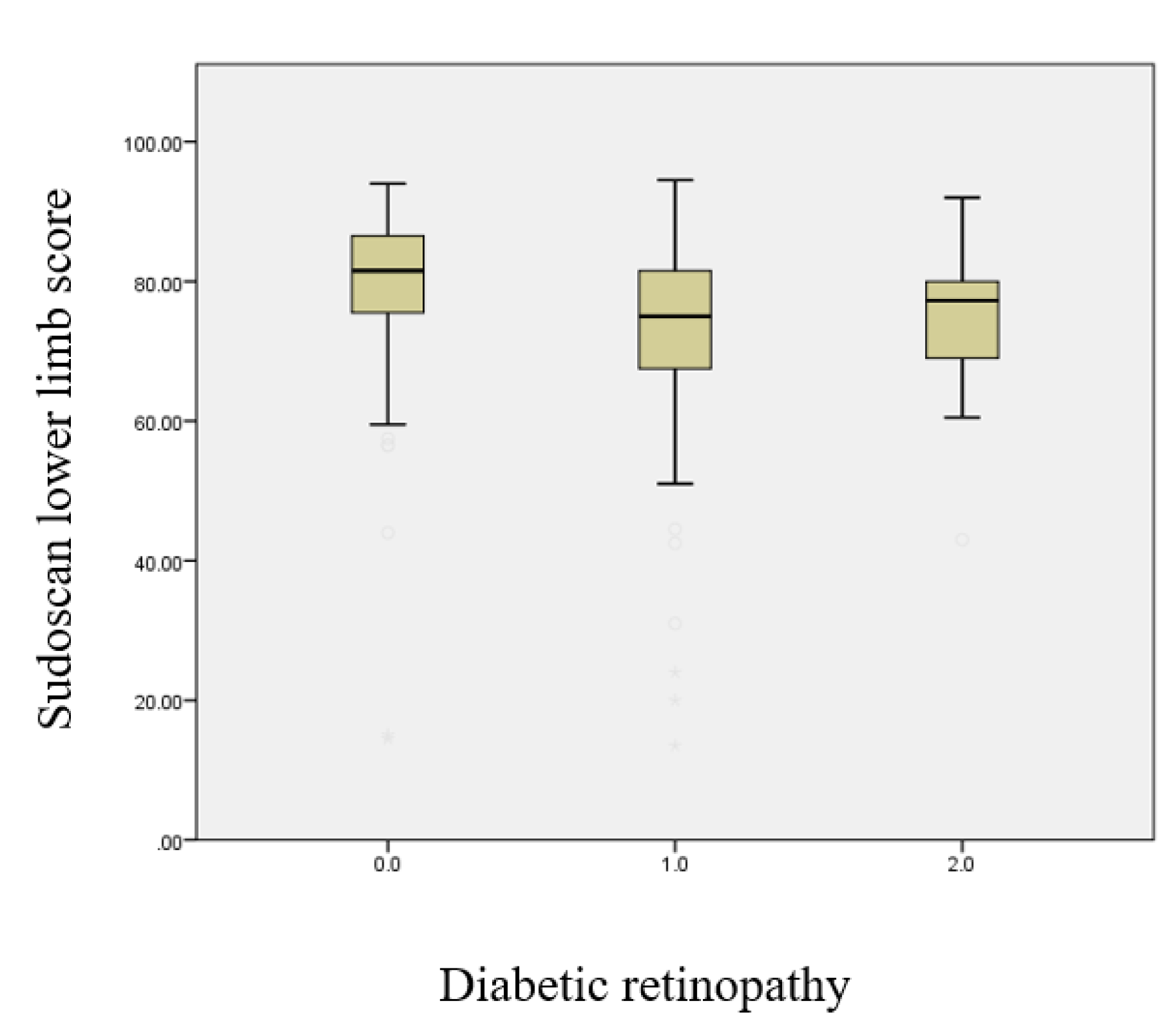

| Sudoscan Lower Limb Score |

79.24 |

11.30 |

71.92 |

15.32 |

73.89 |

12.66 |

76.69 |

13.15 |

<0.001 |

| Sudoscan Upper Limb Score |

69.70 |

13.80 |

66.79 |

15.76 |

72.54 |

18.15 |

68.94 |

14.69 |

0.214 |

The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the study population was 35.8% (n = 97). Among these patients, 85.6% (n = 83) had non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, while 14.4% (n = 14) were diagnosed with proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Female patients accounted for a higher number of DR cases, likely due to their greater representation in the study cohort (Figure 2.1).

Obese individuals showed a higher prevalence of DR compared to non-obese participants (Figure 2.2).

This boxplot illustrates the Sudoscan score for the lower limbs according to the presence and severity of diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2.3). A progressive decline in sudomotor function in the lower limbs is observed with increasing retinopathy severity (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.3.

Boxplot illustrating the relationship between the Sudoscan lower limb score and the severity of diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.3.

Boxplot illustrating the relationship between the Sudoscan lower limb score and the severity of diabetic retinopathy.

This boxplot illustrates the Sudoscan CAN score according to the presence and severity of diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2.4). A significant increase in the risk score for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is observed with increasing retinopathy severity (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.4.

Boxplot illustrating the relationship between the presence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and the severity of diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.4.

Boxplot illustrating the relationship between the presence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and the severity of diabetic retinopathy.

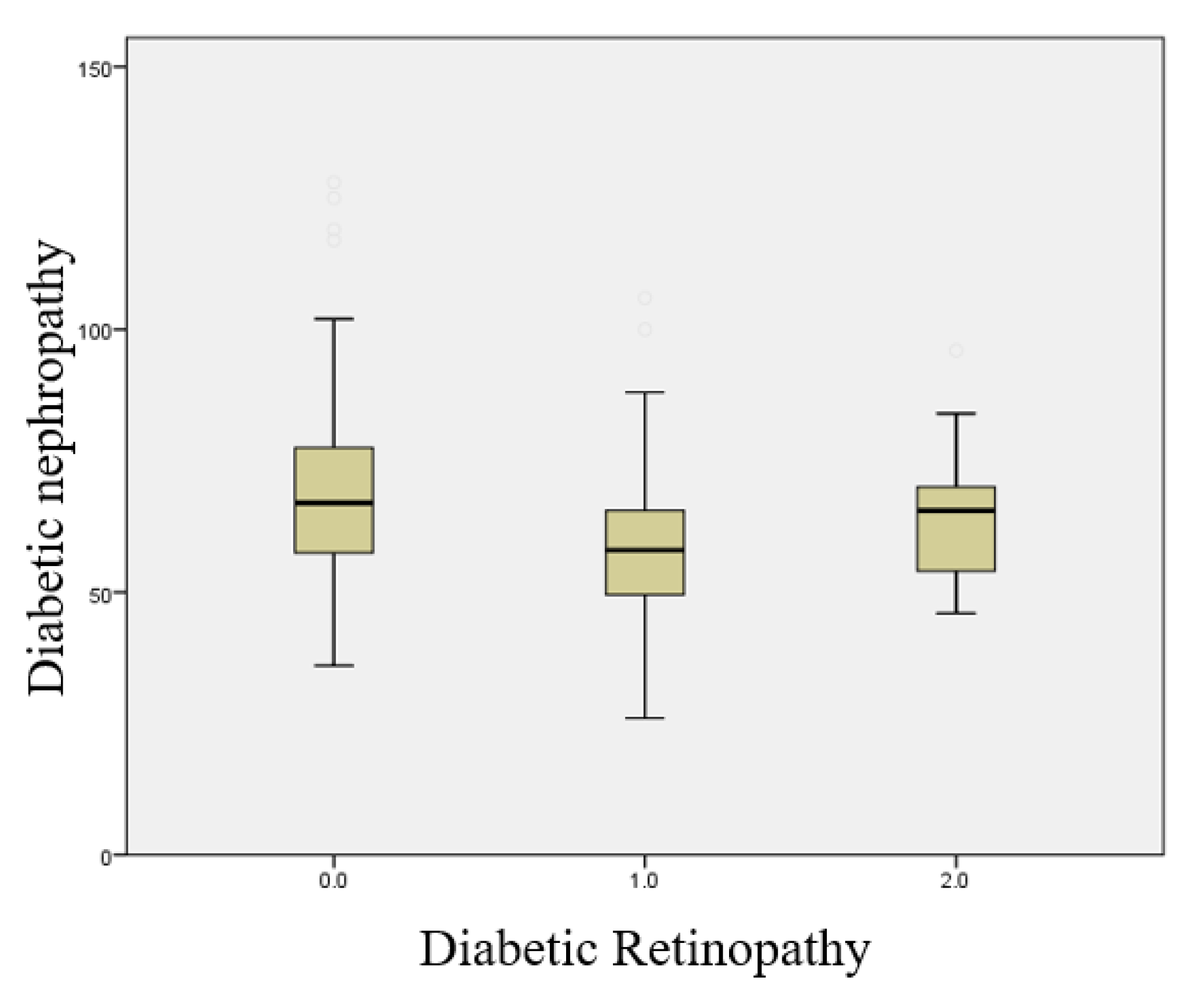

This boxplot illustrates the Sudoscan Nephropathy score according to the presence and severity of diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2.5). A significant increase in the risk score for diabetic nephropathy is observed with increasing retinopathy severity (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.5.

Boxplot illustrating the relationship between the presence of diabetic nephropathy and the severity of diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.5.

Boxplot illustrating the relationship between the presence of diabetic nephropathy and the severity of diabetic retinopathy.

Performance of Sudoscan in the Diagnosis of Diabetic Retinopathy

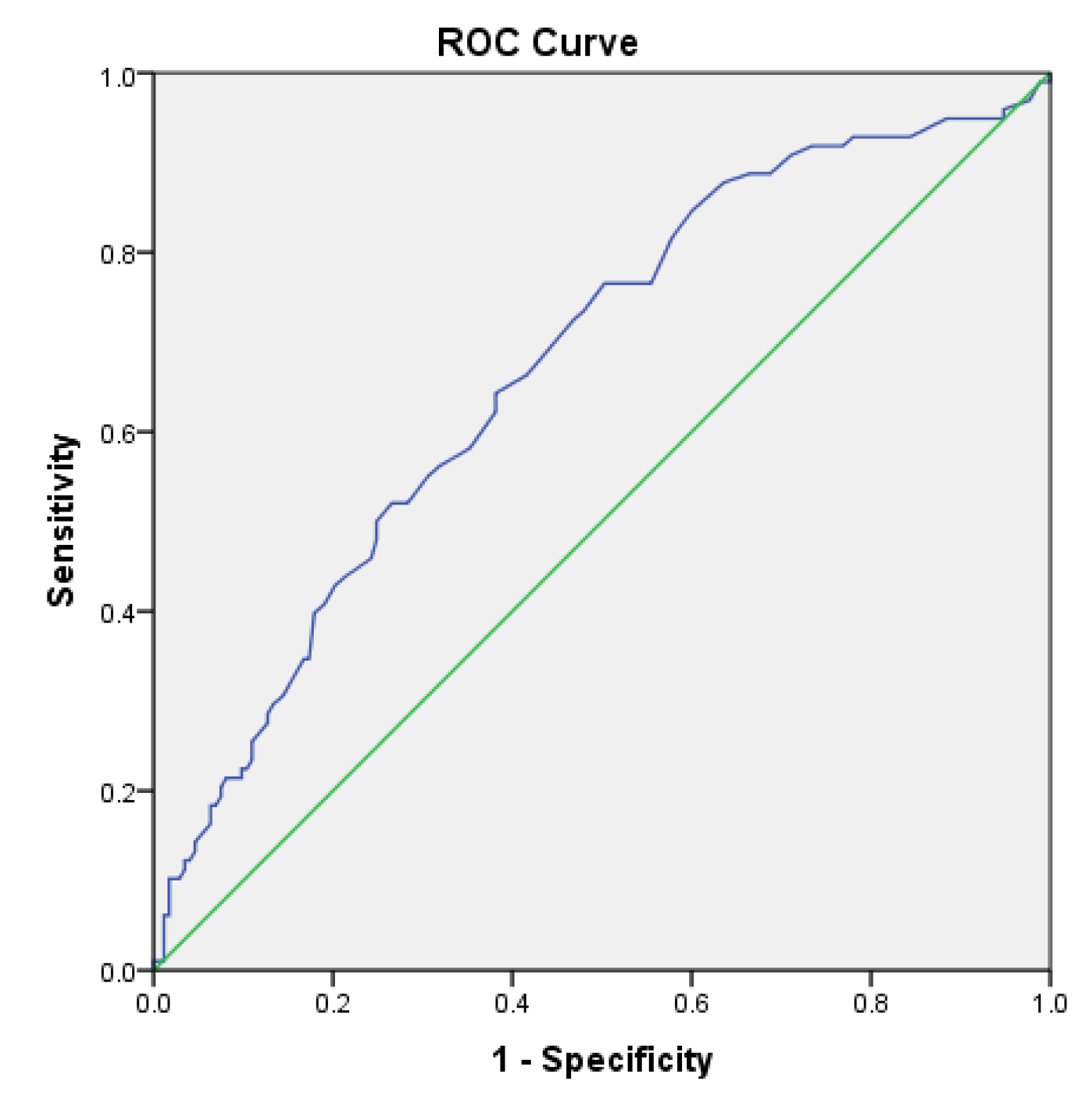

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the Sudoscan lower limb score in predicting diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2.6) was 0.672 (95% CI: 0.605–0.738). The cutoff value for the Sudoscan lower limb score was 81.75, with a sensitivity of 76.5% and a specificity of 50.3% for detecting diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.6.

ROC curve of the Sudoscan lower limb score in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Figure 2.6.

ROC curve of the Sudoscan lower limb score in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

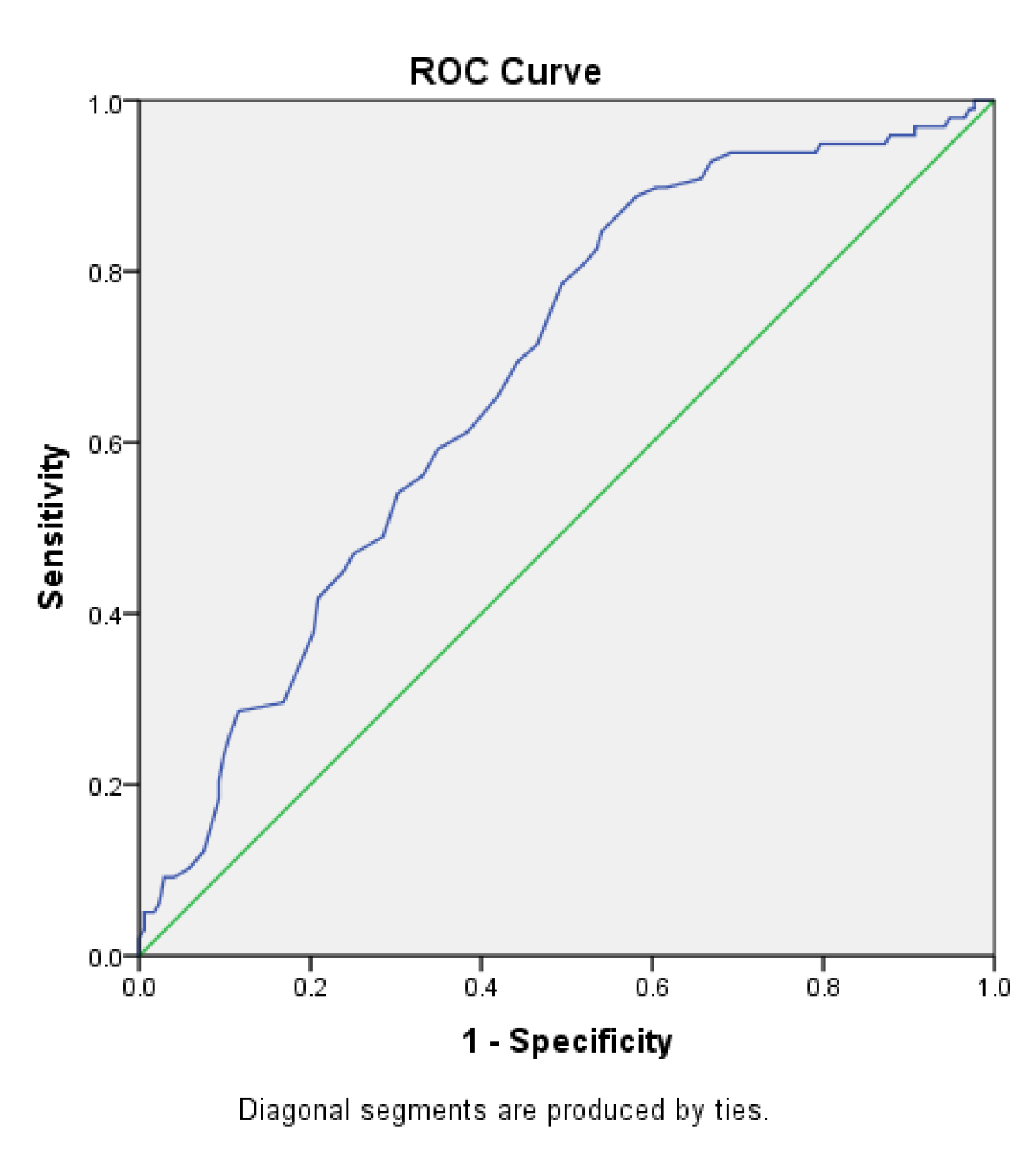

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the Sudoscan Nephropathy score in predicting diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2.7) was 0.679 (95% CI: 0.614–0.743). The cutoff value for the Sudoscan Nephropathy score was 69.5, with a sensitivity of 84.7% and a specificity of 54.1% for detecting diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.7.

ROC curve of the Sudoscan Nephropathy score in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Figure 2.7.

ROC curve of the Sudoscan Nephropathy score in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

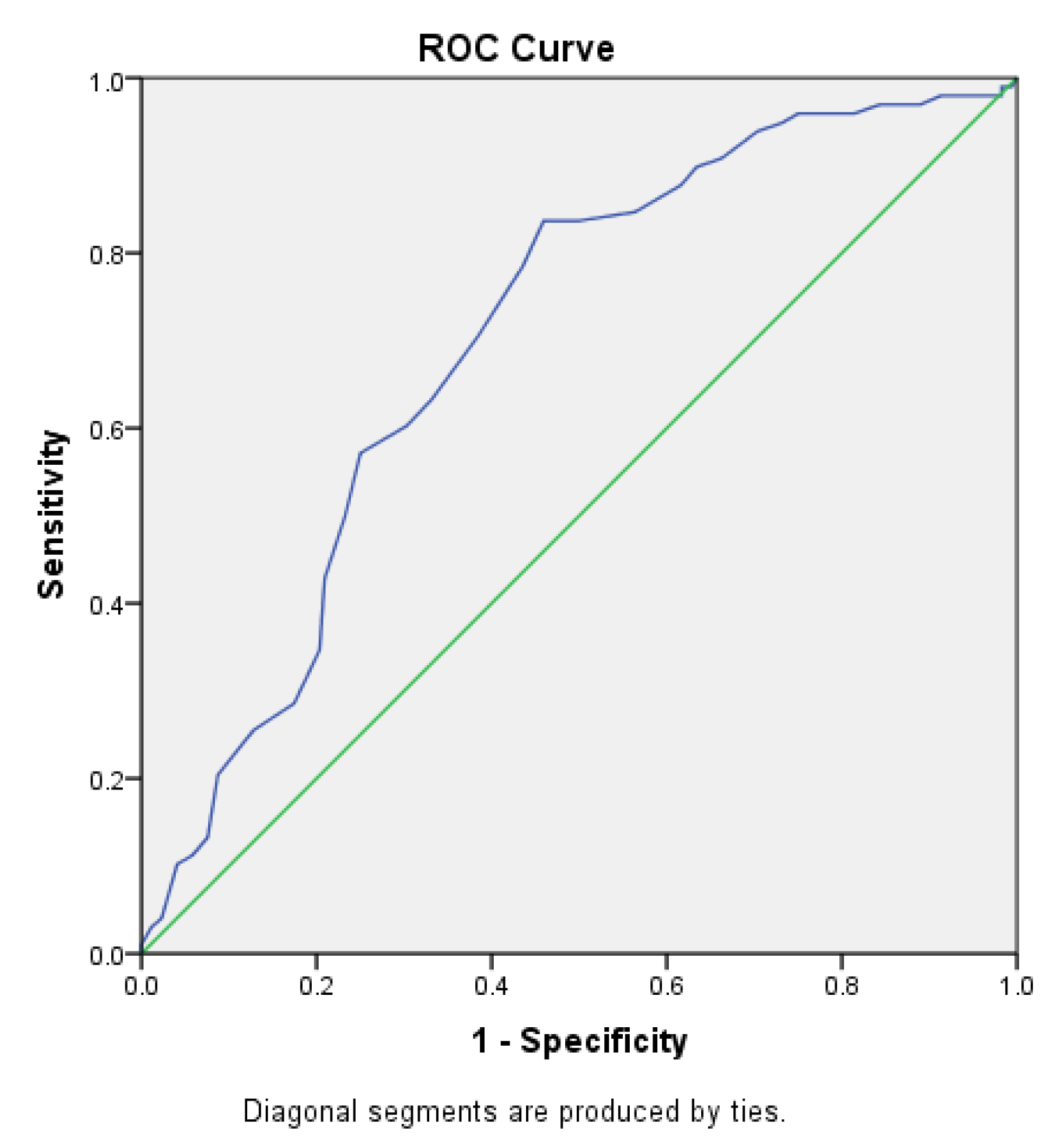

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the Sudoscan CAN score in predicting diabetic retinopathy (Figure 2.8) was 0.702 (95% CI: 0.639–0.765). The cutoff value for the Sudoscan CAN score was 32.5, with a sensitivity of 83.7% and a specificity of 45.9% for detecting diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.8.

ROC curve of the Sudoscan CAN score in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Figure 2.8.

ROC curve of the Sudoscan CAN score in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The statistical analysis presented in Table. 2.2 employs multiple linear regression to investigate the correlation between Sudoscan test variables and diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The multiple regression analysis revealed significant associations between the severity of diabetic retinopathy and several clinical and functional parameters. Lower Sudoscan scores in the lower limbs were correlated with more advanced stages of retinopathy, while higher scores indicating cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN), as well as elevated Ewing and Toronto clinical scores, were positively associated with retinopathy severity. In contrast, Sudoscan scores from the upper limbs and the nephropathy risk score did not show significant correlations. These findings suggest that lower limb sudomotor dysfunction and autonomic nervous system impairment may play a more prominent role in the progression of diabetic retinopathy than other peripheral or renal markers, highlighting the potential utility of these measures in risk stratification and early detection.

In conclusion, the Sudoscan lower limb score, Sudoscan CAN score, Ewing test score, and Toronto Clinical Score showed significant correlations with diabetic retinopathy, suggesting that these measures may be useful in evaluating and monitoring patients with type 2 diabetes for the early detection of diabetic retinopathy.

Table 2.2.

Sudoscan Test Variables in Correlation with Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Using Multiple Linear Regression.

Table 2.2.

Sudoscan Test Variables in Correlation with Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Using Multiple Linear Regression.

| |

Standardized β coefficient |

P-value |

| Sudoscan Lower Limb Score |

-0,272 |

<0.001 |

| Sudoscan Upper Limb Score |

0.036 |

0.571 |

| Sudoscan CAN Score |

0,214 |

0.01 |

| Sudoscan Nephropathy Score |

-0,128 |

0.142 |

| Ewing Score |

0,313 |

<0.001 |

| Toronto Score |

0,219 |

<0.001 |

4. Discussion

A series of systematic reviews and clinical studies have shown that Sudoscan provides high reproducibility and moderate diagnostic accuracy in detecting microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. The review by Novak confirmed the reliability of electrochemical skin conductance measurements, highlighting the test’s consistency and its utility in the early detection of autonomic dysfunction and small fiber neuropathy. Similarly, the meta-analysis by Verdini and colleagues supports the clinical applicability of Sudoscan in screening diabetic complications, particularly in settings with limited resources, such as rural areas or primary care services. Casellini et al. also demonstrated strong correlations between Sudoscan scores and standard neuropathy assessments, validating its use as a non-invasive, easy-to-apply method in clinical practice. The review conducted by Vittrant et al. reinforces these findings, emphasizing Sudoscan’s potential role in the early detection of diabetic microangiopathy. Together, these data support the added value of Sudoscan as a complementary tool that can be integrated into early screening strategies for diabetic retinopathy [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Our study demonstrated a significant correlation between Sudoscan scores and the severity of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown the utility of Sudoscan in detecting diabetic microvascular complications. For example, one study reported a sensitivity of 84.7% and a specificity of 54.1% for detecting diabetic retinopathy, supporting our results, which indicate similar sensitivity and specificity values for the detection of retinopathy [

13].

Multiple clinical studies, including Lin et al., have demonstrated that lower foot electrochemical skin conductance measured by Sudoscan correlates significantly with diabetic retinopathy, independent of neuropathy and nephropathy markers [

8].

Wang and colleagues confirmed that patients with sudomotor dysfunction (ESC < 60 μS) have a significantly increased risk of retinopathy (adjusted OR = 1.57), highlighting the potential of Sudoscan as an early assessment tool [

14].

Several articles highlight that combining Sudoscan scores with clinical tools such as the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI) or albuminuria markers enhances the detection of diabetic retinopathy compared to using individual methods alone [

15,

16].

According to the literature, traditional screening methods include direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy, retinal cameras, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) [

17]. Our study demonstrates that Sudoscan may serve as a valuable complementary tool for diabetic retinopathy screening, as it is non-invasive, provides rapid results, and may enhance traditional screening methods [

18].

Our results showed that the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) was significantly higher in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, indicating more pronounced renal impairment in this group. These findings are consistent with existing literature suggesting that renal dysfunction is frequently associated with the severity of diabetic retinopathy [

19].

The Toronto Score and Ewing tests showed significant positive correlations with the severity of diabetic retinopathy, suggesting that these scores may be useful tools for the evaluation and monitoring of patients with type 2 diabetes in the early detection of diabetic retinopathy. These results are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of these scores in the assessment of diabetic neuropathy [

20].

Our analysis showed that the Sudoscan lower limb score had a significant negative correlation with the severity of diabetic retinopathy, suggesting that a lower score is associated with more severe retinopathy. This finding is consistent with other studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of Sudoscan in monitoring diabetic neuropathy and the risk of diabetic retinopathy [

21].

5. Conclusions

Sudoscan has proven to be effective in detecting diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes, with significant correlations observed between obtained scores and retinopathy severity. Although traditional screening methods remain the gold standard, Sudoscan may serve as a non-invasive complementary method for the early identification of diabetic retinopathy. Although fundus examinations remain the gold standard, the portability and non-invasiveness of Sudoscan make it particularly suitable for screening in rural areas or primary care settings with limited access to ophthalmologists [

9].

Our study confirms findings from existing literature and demonstrates that Sudoscan scores can be used to predict the risk and severity of diabetic retinopathy, thereby providing clinicians with an additional tool for managing patients with complicated type 2 diabetes.

Implementing Sudoscan in clinical practice may enhance the early detection of diabetic complications and guide timely therapeutic interventions, thus contributing to the prevention of diabetic retinopathy progression and other related complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-E.N. and E.R.; methodology A.-E.N., C.D. and G.R.; software A.-E.N. and E.R.; validation, A.-E.N., C.D. and G.R.; formal analysis, A.-E.N. and E.R.; investigation, F.R.; resources, A.-E.N., E.R., C.D. and O.A.P.; data curation, C.S. and O.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-E.N. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, A.-E.N. and E.R.; visualization, F.R.; supervision, G.R.; project administration, A.-E.N.; funding acquisition, A.-E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Nicolae Malaxa” Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania (approval number 2145 on 7 March 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the hospital’s privacy policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DR |

Diabetic Retinopathy |

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| NPDR |

Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| PDR |

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy |

| OCT |

Optical Coherence Tomography |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| HbA1c |

Glycated Hemoglobin |

| ACR |

Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio |

| HDL |

High-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL |

Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| eGFR |

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| CKD |

Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CAN |

Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| CARTs |

Cardiovascular Autonomic Reflex Tests |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| MDRD |

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (equation) |

References

- Hashemi, H.; Rezvan, F.; Pakzad, R.; Ansaripour, A.; Heydarian, S.; Yekta, A.; et al. Global and Regional Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 37, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, Z.L.; Tham, Y.C.; Yu, M.; Chee, M.L.; Rim, T.H.; Cheung, N.; et al. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, H.; Schwartz, M.D.; Wu, B. Age at Diagnosis of Diabetes, Obesity, and the Risk of Dementia among Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, eXXXXXXX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.Y.; Tan, T.E. The Diabetic Retinopathy “Pandemic” and Evolving Global Strategies: The 2023 Friedenwald Lecture. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Wong, J.; Molyneaux, L.; Constantino, M.; Twigg, S.M.; Yue, D.K. Timing Is Everything: Age of Onset Influences Long-Term Retinopathy Risk in Type 2 Diabetes, Independent of Traditional Risk Factors. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, L.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M.; et al. Global Trends and Performances in Diabetic Retinopathy Studies: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1128008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Zeng, Q. The Application of Sudoscan for Screening Microvascular Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, P. Electrochemical Skin Conductance: A Systematic Review. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdini, F.; Mengarelli, A.; Chemello, G.; Salvatori, B.; Morettini, M.; Göbl, C.; et al. Sensors and Devices Based on Electrochemical Skin Conductance and Bioimpedance Measurements for the Screening of Diabetic Foot Syndrome: Review and Meta-Analysis. Biosensors 2025, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinik, A.I.; Erbas, T.; Casellini, C.M. Diabetic Cardiac Autonomic Neuropathy, Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Diabetes Investig. 2013, 4, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittrant, B.; Ayoub, H.; Brunswick, P. From Sudoscan to Bedside: Theory, Modalities, and Application of Electrochemical Skin Conductance in Medical Diagnostics. Front. Neuroanat. 2024, 18, 1454095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvarajah, D.; Cash, T.; Davies, J.; Sankar, A.; Rao, G.; Grieg, M.; et al. SUDOSCAN: A Simple, Rapid, and Objective Method with Potential for Screening for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Chen, N.; Wang, Y.; Ni, J.; Lu, J.; Zhao, W.; et al. Association of Sudomotor Dysfunction with Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrine 2024, 84, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, T.J.; Song, Y.; Jang, H.C.; Choi, S.H. SUDOSCAN in Combination with the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument Is an Effective Tool for Screening Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ulloa, A.C.; Almeda-Valdes, P.; Cuatecontzi-Xochitiotzi, T.E.; Ramírez-García, J.A.; Díaz-Pineda, M.; Garnica-Carrillo, F.; et al. Detection of Sudomotor Alterations Evaluated by Sudoscan in Patients with Recently Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e003005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. 12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S231–S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinik, A.I.; Nevoret, M.L.; Casellini, C.; Parson, H. Diabetic Neuropathy. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2013, 42, 747–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orchard, T.J.; Forrest, K.Y.Z.; Ellis, D.; Becker, D.J. Cumulative Glycemic Exposure and Microvascular Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus: The Glycemic Threshold Revisited. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997, 157, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, S.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Dyck, P.J.; Freeman, R.; Horowitz, M.; Kempler, P.; et al. Diabetic Neuropathies: Update on Definitions, Diagnostic Criteria, Estimation of Severity, and Treatments. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.G.; Russell, J.; Feldman, E.L.; Goldstein, J.; Peltier, A.; Smith, S.; et al. Lifestyle Intervention for Pre-Diabetic Neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).