Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining ACC Samples

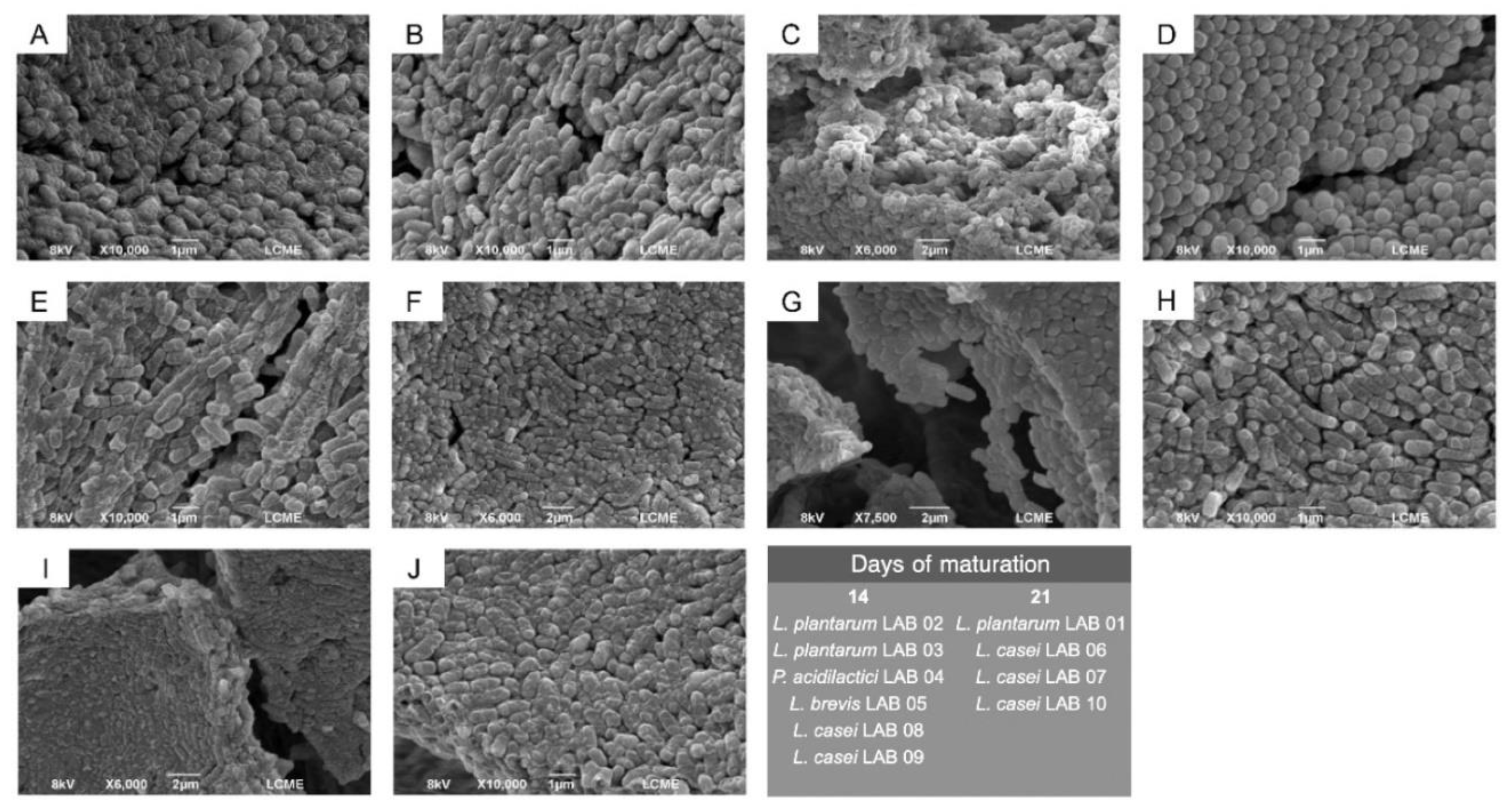

2.2. Isolation and Morphological Characterization of Potentially Probiotic LAB by SEM.

2.3. Genotypic Identification

2.4. Hemolytic Activity:

2.5. Gelatinase Production

2.6. Mucin Degradation Capacity

2.7. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.8. Evaluation of LAB Survival in the Gastrointestinal System In Vitro

2.9. Auto-Aggregation and Hydrophobicity Test

2.10. Lipase Production Assay

2.11. Microencapsulation of LAB Strains

2.12. Survival of LAB After Spray Drying and During Shelf-Life

2.13. Morphology and Size of Microparticles

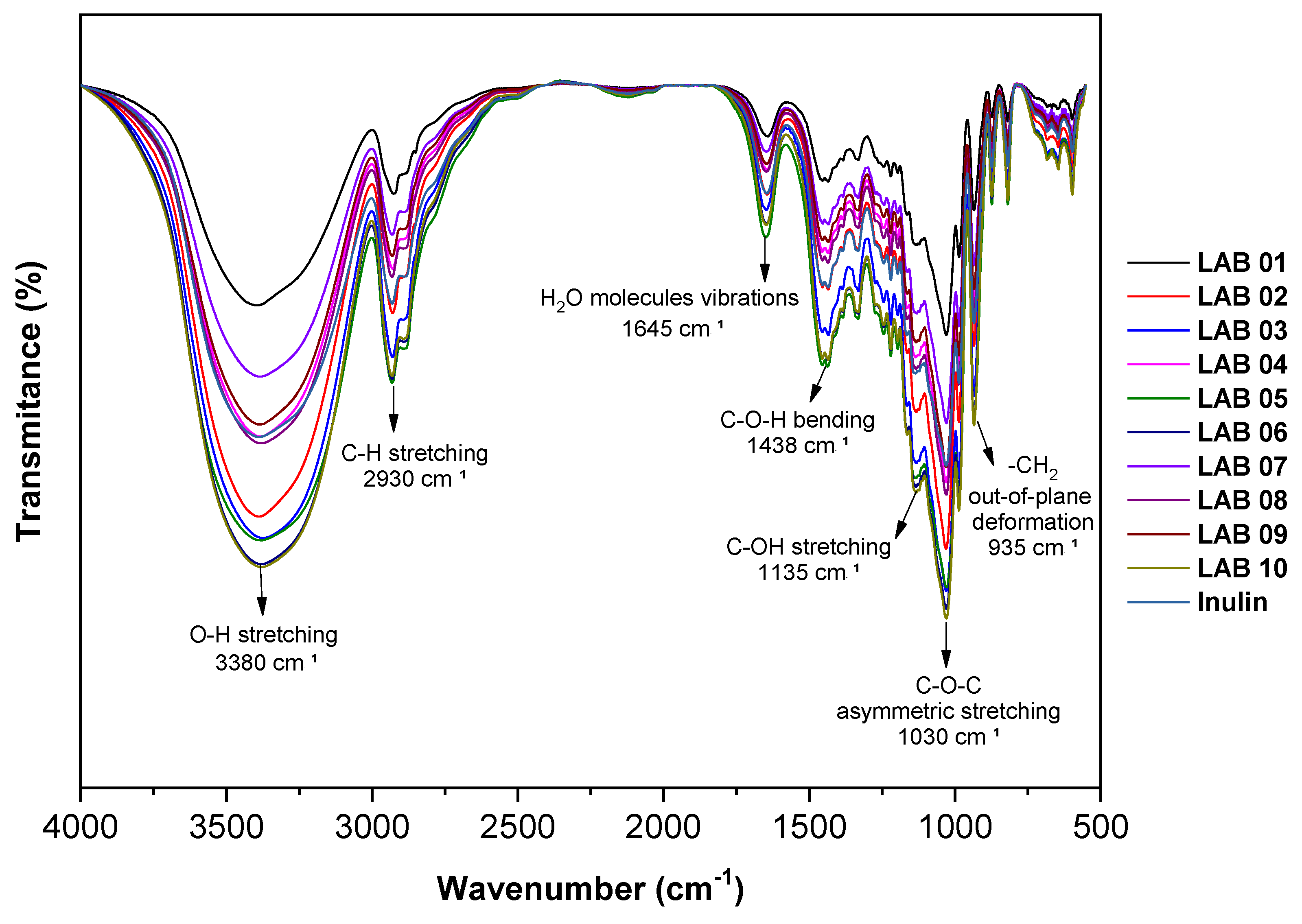

2.14. Interaction Between Microcapsule Components by FTIR

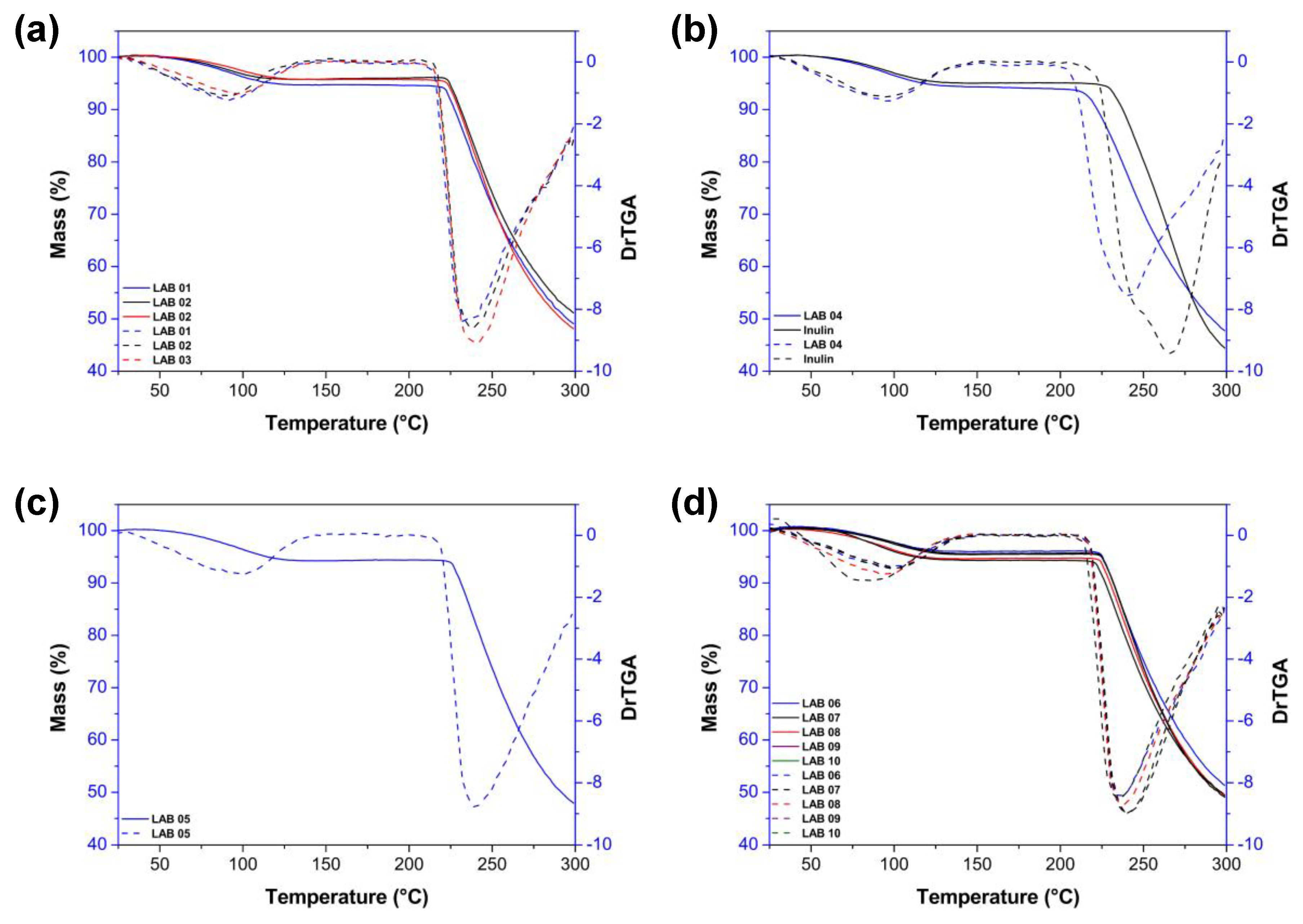

2.15. Thermogravimetric Analysis

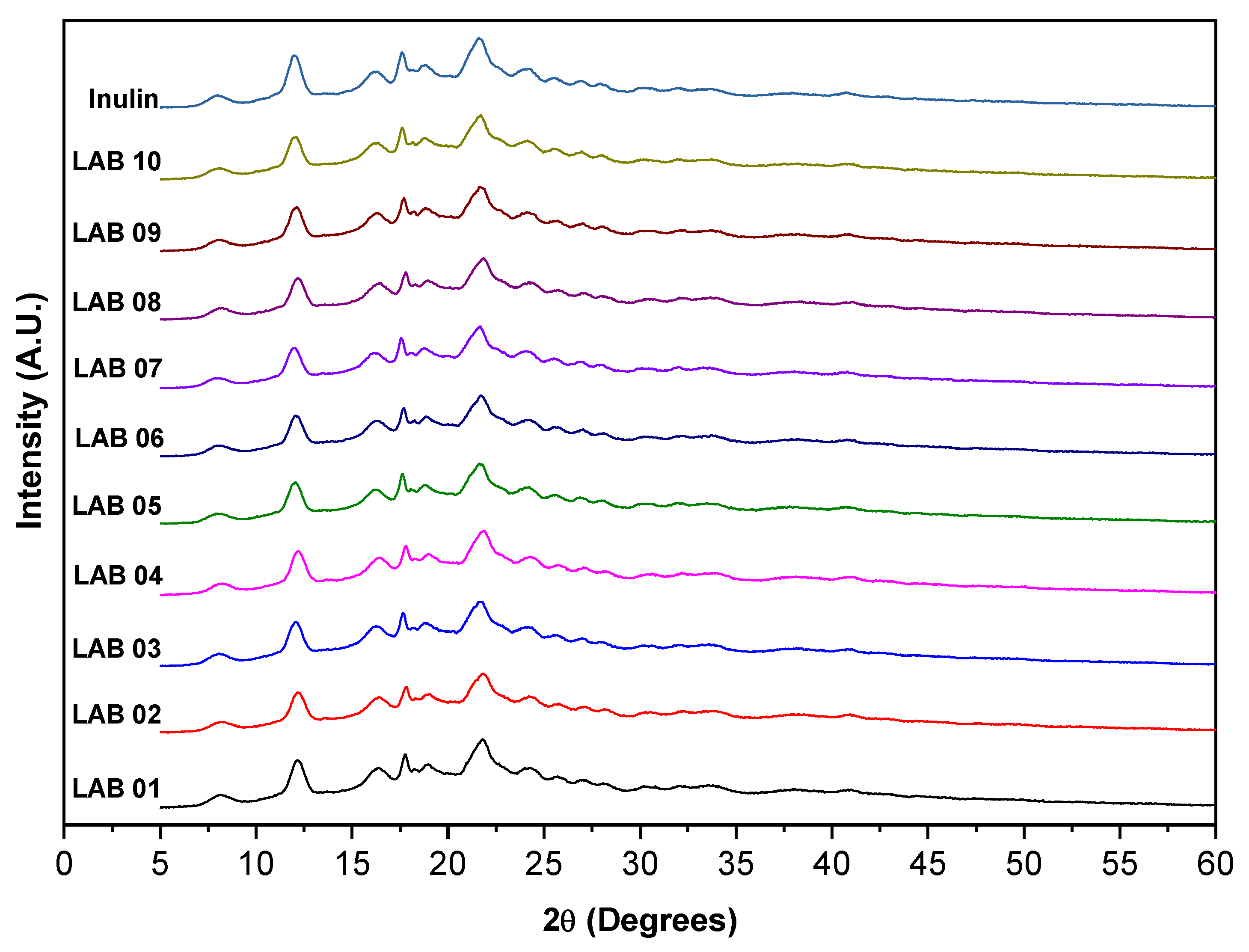

2.16. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.17. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of BAL Strains

3.2. Safety Analyses of LAB Isolates

| Cepas | Antibióticos (µg/mL) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Benzylpenicillin | Streptomycin | Clindamycin | Cephalexin | Metronidazole | Meropenem | ||||||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| L. plantarum LAB 01 | 2 | 4 | 4 | - | 4 | 64 | 0.25 | 0.25 | - | - | - | - | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| L. plantarum LAB 02 | 0.25 | 4 | 16 | 64 | 16 | - | 2 | 16 | 64 | - | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| L. plantarum LAB 03 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 64 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 32 | - | - | - | 0.25 | 4 |

| P. acidilactici LAB 04 | 4 | - | 4 | 64 | 64 | - | 0.5 | 4 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 16 |

| L. brevis LAB 05 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | 32 | 64 | 256 | 2 | 16 | 64 | - | - | - | 2 | 4 |

| L. casei LAB 06 | 0.5 | 8 | 1 | 32 | 2 | 64 | 0.25 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 | - |

| L. casei LAB 07 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 16 | 128 | 0.25 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 4 | 64 |

| L. casei LAB 08 | 8 | 16 | 0.25 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 0.5 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 0.5 | - |

| L. casei LAB 09 | 2 | 32 | 1 | 2 | 32 | 512 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 32 | - | - | - | 0.25 | 2 |

| L. casei LAB 10 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 0.5 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 8 | 64 |

| L. plantarum ATCC 8014 | 4 | - | 4 | 64 | 128 | - | 0.25 | 4 | - | - | - | - | 2 | - |

| L. casei BGP 93 | 4 | - | 4 | - | 128 | 1024 | 0.25 | 4 | - | - | - | - | 2 | - |

| Cutting Point | ||||||||||||||

| L. plantarum | 2 | 0.5 | 16* | 2 | 16 | 4 | 2 | |||||||

| L. casei | 4 | 0.5 | 64 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 2 | |||||||

| L. brevis** | 2 | 0.5 | 64 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 2 | |||||||

| P. acidilactici | 4 | 0.5 | 64 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 2 | |||||||

3.3. Lipase Production

3.4. Survival in the In Vitro Gastrointestinal System

| Strains | LAB Count (Log UFC/g) | Survival Rate (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Stomach | Intestine | Stomach | Intestine | |

| L. plantarum LAB 01 | 8.53±0.02abA | 8.33±0.10aA | 7.65±0.10aB | 97.60±1.39abA | 89.69±1.01aB |

| L. plantarum LAB 02 | 8.65±0.03aA | 8.12±0.12abcB | 7.77±0.02aC | 93.87±1.03abA | 89.76±0.47aB |

| L. plantarum LAB 03 | 8.08±0.40abA | 8.10±0.14abcA | 7.69±0.55aA | 100.37±3.19aA | 95.12±2.13aA |

| P. acidilactici LAB 04 | 8.44±0.03abA | 7.46±0.12bcB | 7.14±0.09aB | 88.43±1.72bA | 84.63±1.38aA |

| L. brevis LAB 05 | 8.77±0.08aA | 8.31±0.11abB | 7.95±0.06aB | 94.73±0.30abA | 90.71±0.16aB |

| L. casei LAB 06 | 8.57±0.27abA | 8.06±0.31abcA | 7.58±0.07aA | 94.08±0.66abA | 88.53±1.90aA |

| L. casei LAB 07 | 8.49±0.13abA | 7.74±0.11abcB | 7.46±0.09aB | 91.22±2.70abA | 87.95±0.23aA |

| L. casei LAB 08 | 7.89±0.07bA | 7.36±0.02cB | 7.02±0.13aB | 93.22±1.14abA | 88.90±0.91aA |

| L. casei LAB 09 | 8.27±0.13abA | 7.90±0.43abcA | 7.45±0.39aA | 95.48±3.73abA | 90.20±6.19aA |

| L. casei LAB 10 | 8.32±0.29abA | 7.45±0.31cA | 7.37±0.28aA | 89.72±6.84abA | 88.76±6.39aA |

3.5. Auto-Aggregation and Hydrophobicity Assay

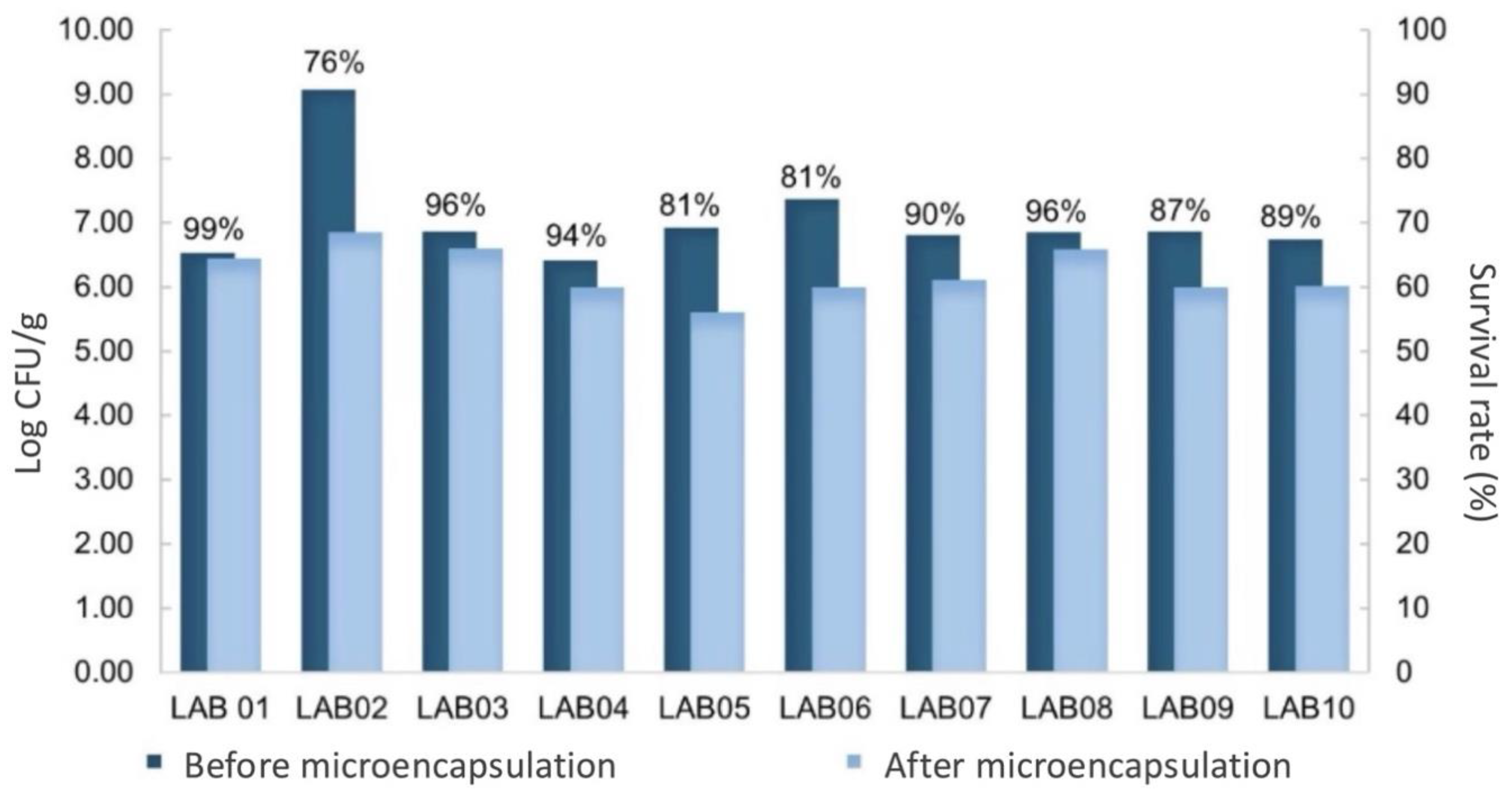

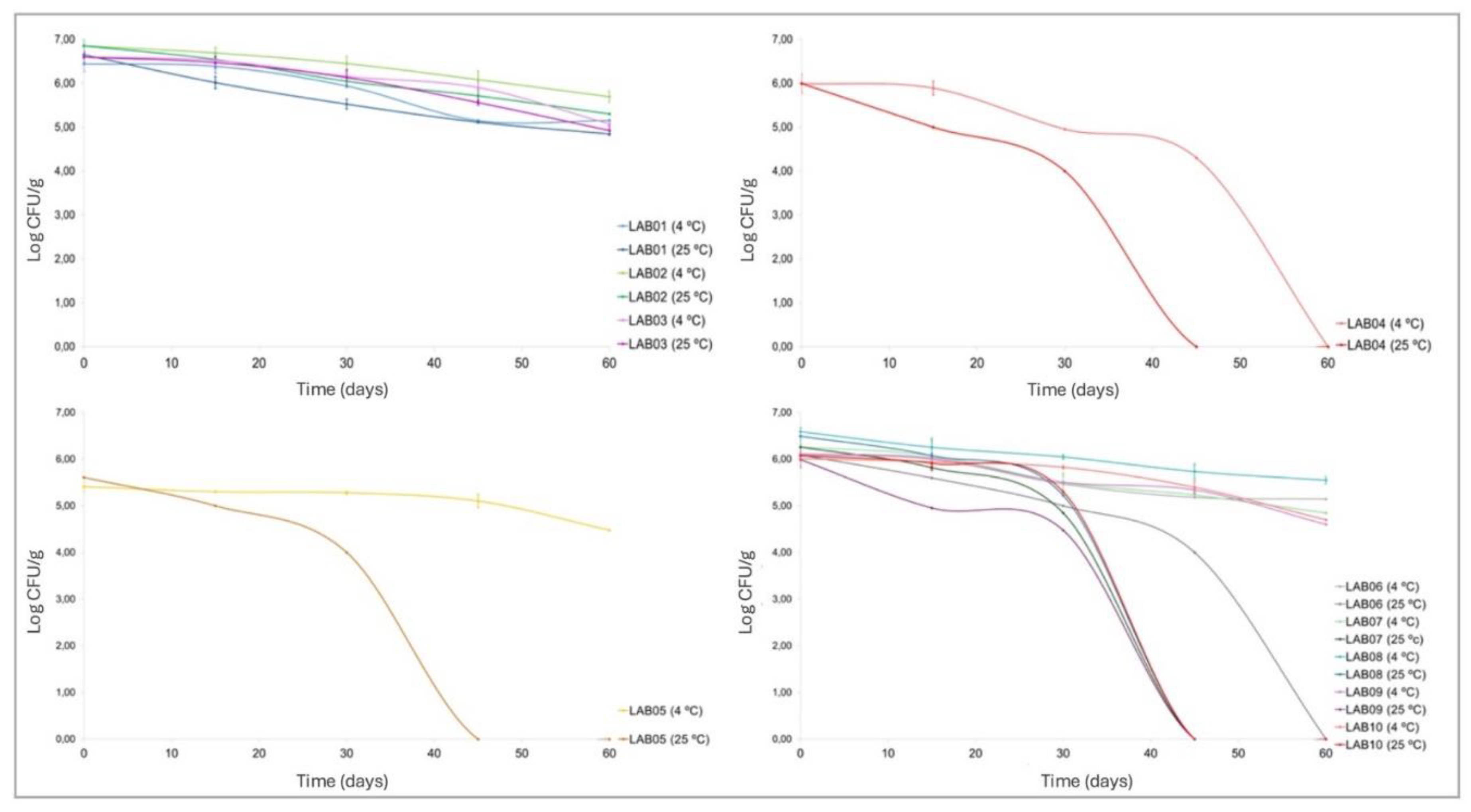

3.6. Survival of LAB After Spray-Drying and During Shelf-Life

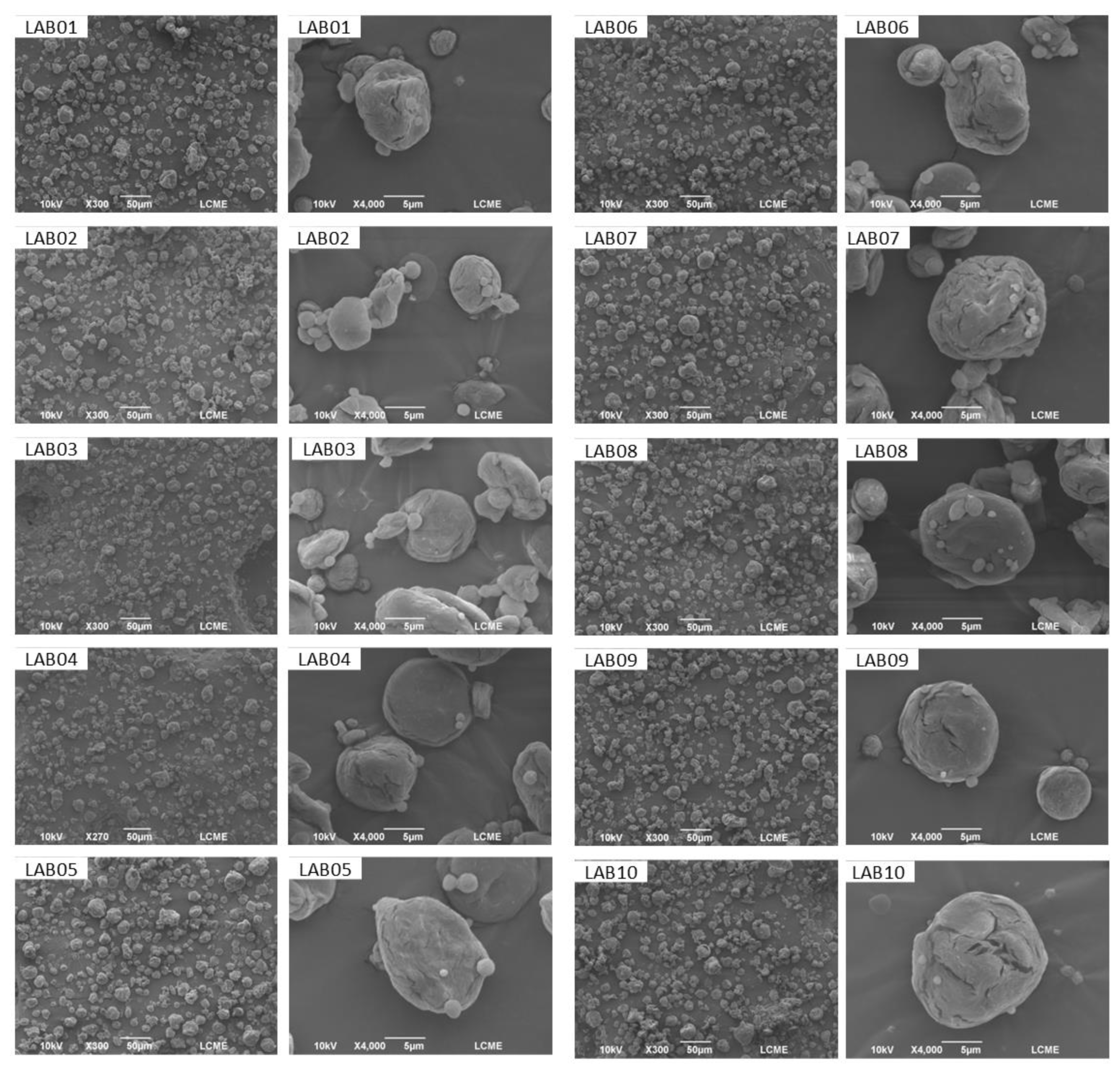

3.7. Morphology and Size of LAB-Containing Microparticles

3.8. Interaction Between Microcapsule Components by FTIR

3.9. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.10. Thermogravimetric Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zanetti, V.C.; Maran, E.M.; Cabral, L.; Miotto Lindner, M.; de Oliveira Costa, A.C.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Louredo, F.J.C.; Tribuzi, G.; Block, J.M.; da Silveira, S.M.; et al. Seasonal Microbial Dynamics Influence on the Biochemical Identity of Artisanal Colonial Cheese from Southern Brazil during Ripening. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2025, 78. [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, B.A.; Magnani, M.; Luciano, W.A.; Campagnollo, F.B.; Pimentel, T.C.; Alvarenga, V.O.; Pelegrino, B.O.; Cruz, A.G.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses: An Overview of Their Characteristics, Main Types and Regulatory Aspects. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1636–1657. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, R.; Carvalho, M.M.; Voidaleski, M.F.; Daros, G.F.; Guaragni, A.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; De Dea Lindner, J. Brazilian Artisanal Colonial Cheese: Characterization, Microbiological Safety, and Survival of Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis during Ripening. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2129–2135. [CrossRef]

- Neviani, E.; Gatti, M.; Gardini, F.; Levante, A. Microbiota of Cheese Ecosystems: A Perspective on Cheesemaking. Foods 2025, 14, 830. [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; Guinee, T.P.; Cogan, T.M.; McSweeney, P.L.H. Overview of Cheese Manufacture. In Fundamentals of Cheese Science; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2017; pp. 11–25.

- da Silva, T.F.; Glória, R. de A.; Americo, M.F.; Freitas, A. dos S.; de Jesus, L.C.L.; Barroso, F.A.L.; Laguna, J.G.; Coelho-Rocha, N.D.; Tavares, L.M.; le Loir, Y.; et al. Unlocking the Potential of Probiotics: A Comprehensive Review on Research, Production, and Regulation of Probiotics. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 16, 1687–1723. [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Liu, S.; Yang, G.; Hou, X.; Fang, Y. Next-Generation Probiotics: Innovations in Safety Assessments. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 61, 101238. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Çon, A.H. Isolation and Characterization of Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Cheese. LWT 2021, 152, 112319. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, D.; Wang, C.-Z.; Wan, J.-Y.; Yao, H.; Yuan, C.-S. Probiotics Fortify Intestinal Barrier Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Camelo-Silva, C.; Figueredo, L.L.; Zanetti, V.C.; Ambrosi, A.; Di Luccio, M.; Verruck, S. Microencapsulation of Probiotics. In Probiotic Foods and Beverages; New York, NY, 2023; pp. 199–212.

- Gruskiene, R.; Lavelli, V.; Sereikaite, J. Application of Inulin for the Formulation and Delivery of Bioactive Molecules and Live Cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 327, 121670. [CrossRef]

- Dantas, A.; Verruck, S.; Machado Canella, M.H.; Maran, B.M.; Murakami, F.S.; de Avila Junior, L.B.; de Campos, C.E.M.; Hernandez, E.; Prudencio, E.S. Current Knowledge about Physical Properties of Innovative Probiotic Spray-Dried Powders Produced with Lactose-Free Milk and Prebiotics. LWT 2021, 151, 112175. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Aryantini, N.P.D.; Yamasaki, E.; Saito, M.; Tsukigase, Y.; Nakatsuka, H.; Urashima, T.; Horiuchi, R.; Fukuda, K. In Vitro Probiotic Characterization and Safety Assessment of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Raw Milk of Japanese-Saanen Goat (Capra Hircus). Animals 2022, 13, 7. [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.L.A.; Balthazar, C.F.; Esmerino, E.A.; Vieira, A.H.; Cappato, L.P.; Neto, R.P.C.; Verruck, S.; Cavalcanti, R.N.; Portela, J.B.; Andrade, M.M.; et al. Effect of Sodium Reduction and Flavor Enhancer Addition on Probiotic Prato Cheese Processing. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, P.-Y. Conservative Fragments in Bacterial 16S RRNA Genes and Primer Design for 16S Ribosomal DNA Amplicons in Metagenomic Studies. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7401. [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-High-Throughput Microbial Community Analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq Platforms. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throuthput Sequence Data. 2010.

- Cock, P.J.A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B.; et al. Biopython: Freely Available Python Tools for Computational Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [CrossRef]

- Masella, A.P.; Bartram, A.K.; Truszkowski, J.M.; Brown, D.G.; Neufeld, J.D. PANDAseq: Paired-End Assembler for Illumina Sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 31. [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, T.Z.; Hugenholtz, P.; Larsen, N.; Rojas, M.; Brodie, E.L.; Keller, K.; Huber, T.; Dalevi, D.; Hu, P.; Andersen, G.L. Greengenes, a Chimera-Checked 16S RRNA Gene Database and Workbench Compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5069–5072. [CrossRef]

- Margalho, L.P.; Feliciano, M.D.; Silva, C.E.; Abreu, J.S.; Piran, M.V.F.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses Are Rich and Diverse Sources of Nonstarter Lactic Acid Bacteria Regarding Technological, Biopreservative, and Safety Properties—Insights through Multivariate Analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 7908–7926. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, M.; Wan, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Tao, X.; Shah, N.P.; Wei, H. Screening Probiotic Strains for Safety: Evaluation of Virulence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Enterococci from Healthy Chinese Infants. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4282–4290. [CrossRef]

- Leska, A.; Nowak, A.; Rosicka-Kaczmarek, J.; Ryngajłło, M.; Czarnecka-Chrebelska, K.H. Characterization and Protective Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria Intended to Be Used in Probiotic Preparation for Honeybees (Apis mellifera L.)—An In Vitro Study. Animals 2023, 13, 1059. [CrossRef]

- ISO, I.O. for S. Susceptibility Testing of Infectious Agents and Evaluation of Performance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Devices – Part 1: Broth Micro-Dilution Reference Method for Testing the in Vitro Activity of Antimicrobial Agents against Rapidly Growing Aerobi; Geneva, 2019;

- EUC, E.C. Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Animal Nutrition on the Criteria for Assessing the Safety of Micro-Organisms Resistant to Antibiotics of Human Clinical and Veterinary Importance; 2003;

- EFSA Guidance on the Assessment of Bacterial Susceptibility to Antimicrobials of Human and Veterinary Importance. EFSA J. 2012, 10. [CrossRef]

- EUCAST European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters.; 2021;

- Gad, G.F.M.; Abdel-Hamid, A.M.; Farag, Z.S.H. Antibiotic Resistance in Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Some Pharmaceutical and Dairy Products. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Celiktas, O.Y.; Kocabas, E.E.H.; Bedir, E.; Sukan, F.V.; Ozek, T.; Baser, K.H.C. Antimicrobial Activities of Methanol Extracts and Essential Oils of Rosmarinus officinalis, Depending on Location and Seasonal Variations. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 553–559. [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static in Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [CrossRef]

- Zoldan, J.; De Marco, I.; Verruck, S.; Gomide, A.I.; Cartabiano, C.E.L.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; De Dea Lindner, J. Evaluation of Viability to Simulated Gastrointestinal Tract Passage of Probiotic Strains and Pioneer Bioaccessibility Analyses of Antioxidants in Chocolate. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102494. [CrossRef]

- Camelo-Silva, C.; Figueredo, L.L.; Cesca, K.; Verruck, S.; Ambrosi, A.; Di Luccio, M. Membrane Emulsification as an Emerging Method for Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG® Encapsulation. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 2651–2667. [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, I.; Saeed, M.; Khan, W.A.; Khaliq, A.; Chughtai, M.F.J.; Iqbal, R.; Tehseen, S.; Naz, S.; Liaqat, A.; Mehmood, T.; et al. In Vitro Probiotic Potential and Safety Evaluation (Hemolytic, Cytotoxic Activity) of Bifidobacterium Strains Isolated from Raw Camel Milk. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 354. [CrossRef]

- Farid, W.; Masud, T.; Sohail, A.; Ahmad, N.; Naqvi, S.M.S.; Khan, S.; Ali, A.; Khalifa, S.A.; Hussain, A.; Ali, S.; et al. Gastrointestinal Transit Tolerance, Cell Surface Hydrophobicity, and Functional Attributes of Lactobacillus acidophilus Strains Isolated from Indigenous Dahi. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 5092–5102. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Gibbs, P.A.; Teixeira, P. Virulence Factors among Enterococci Isolated from Traditional Fermented Meat Products Produced in the North of Portugal. Food Control 2010, 21, 651–656. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Ban, O.-H.; Bang, W.Y.; Chae, S.A.; Oh, S.; Park, C.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.-J.; Yang, J.; Jung, Y.H. Safety Assessment of Lactobacillus reuteri IDCC 3701 Based on Phenotypic and Genomic Analysis. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 10. [CrossRef]

- Colautti, A.; Arnoldi, M.; Comi, G.; Iacumin, L. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Factors in Lactobacilli: Something to Carefully Consider. Food Microbiol. 2022, 103, 103934. [CrossRef]

- Herath, M.; Hosie, S.; Bornstein, J.C.; Franks, A.E.; Hill-Yardin, E.L. The Role of the Gastrointestinal Mucus System in Intestinal Homeostasis: Implications for Neurological Disorders. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Castro-López, C.; García-Galaz, A.; García, H.S.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A. Potential Probiotic Lactobacilli Strains Isolated from Artisanal Mexican Cocido Cheese: Evidence-Based Biosafety and Probiotic Action-Related Traits on in Vitro Tests. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2137–2152. [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, E.A.; Yarullina, D.R. Antibiotic Resistance of Lactobacillus Strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 1407–1416. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; Pan, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, T. Comparative Studies on Antibiotic Resistance in Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Control 2015, 50, 250–258. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Teng, D.; Mao, R.; Hao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. A Critical Review of Antibiotic Resistance in Probiotic Bacteria. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109571. [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, E.; DePetrillo, J.; Qadeer, F. Meropenem Resistant Lactobacillus Endocarditis in an Immunocompetent Patient. SAGE Open Med. Case Reports 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, E.; Gorokhova, I.; Karimullina, G.; Yarullina, D. Alarming Antibiotic Resistance of Lactobacilli Isolated from Probiotic Preparations and Dietary Supplements. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1557. [CrossRef]

- Duche, R.T.; Singh, A.; Wandhare, A.G.; Sangwan, V.; Sihag, M.K.; Nwagu, T.N.T.; Panwar, H.; Ezeogu, L.I. Antibiotic Resistance in Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria of Fermented Foods and Human Origin from Nigeria. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 142. [CrossRef]

- Ammor, M.S.; Belén Flórez, A.; Mayo, B. Antibiotic Resistance in Non-Enterococcal Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 559–570. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.G.; Castro, R.D.; Sant’Anna, F.M.; Barquete, R.M.; Oliveira, L.G.; Acurcio, L.B.; Luiz, L.M.P.; Sales, G.A.; Nicoli, J.R.; Souza, M.R. In Vitro Assessment of the Probiotic Potential of Lactobacilli Isolated from Minas Artisanal Cheese Produced in the Araxá Region, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Arq. Bras. Med. Veterinária e Zootec. 2019, 71, 647–657. [CrossRef]

- Ołdak, A.; Zielińska, D.; Łepecka, A.; Długosz, E.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Polish Regional Cheeses Exhibit Anti-Staphylococcal Activity and Selected Probiotic Properties. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1025–1038. [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Tao, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, R.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Su, J.; Lu, Z.; Chen, X.; Gu, R. Isolation of Novel Lactobacillus with Lipolytic Activity from the Vinasse and Their Preliminary Potential Using as Probiotics. AMB Express 2020, 10, 91. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Torres, M.; Mancheño, J.M.; de las Rivas, B.; Muñoz, R. Characterization of a Halotolerant Lipase from the Lactic Acid Bacteria Lactobacillus plantarum Useful in Food Fermentations. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Konkit, M.; Kim, W. Activities of Amylase, Proteinase, and Lipase Enzymes from Lactococcus chungangensis and Its Application in Dairy Products. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4999–5007. [CrossRef]

- Ait Chait, Y.; Gunenc, A.; Hosseinian, F.; Bendali, F. Antipathogenic and Probiotic Potential of Lactobacillus brevis Strains Newly Isolated from Algerian Artisanal Cheeses. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 2021, 66, 429–440. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Gonçalves dos Santos, M.T.P.; Galván, A.I.; Merchán, A. V.; González, E.; Córdoba, M. de G.; Benito, M.J. Screening of Autochthonous Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains from Artisanal Soft Cheese: Probiotic Characteristics and Prebiotic Metabolism. LWT 2019, 114, 108388. [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Ferguson, L.R.; Shu, Q.; Garg, S. Flow Cytometric Assessment of the Protectants for Enhanced in Vitro Survival of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria through Simulated Human Gastro-Intestinal Stresses. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 345–356. [CrossRef]

- Gomand, F.; Borges, F.; Burgain, J.; Guerin, J.; Revol-Junelles, A.-M.; Gaiani, C. Food Matrix Design for Effective Lactic Acid Bacteria Delivery. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 285–310. [CrossRef]

- Barache, N.; Ladjouzi, R.; Belguesmia, Y.; Bendali, F.; Drider, D. Abundance of Lactobacillus plantarum Strains with Beneficial Attributes in Blackberries (Rubus sp.), Fresh Figs (Ficus carica), and Prickly Pears (Opuntia ficus-indica) Grown and Harvested in Algeria. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1514–1523. [CrossRef]

- Margalho, L.P.; Jorge, G.P.; Noleto, D.A.P.; Silva, C.E.; Abreu, J.S.; Piran, M.V.F.; Brocchi, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Biopreservation and Probiotic Potential of a Large Set of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses: From Screening to in Product Approach. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242, 126622. [CrossRef]

- Yungareva, T.; Urshev, Z. The Aggregation-Promoting Factor in Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus: Confirmation of the Presence and Expression of the Apf Gene and in Silico Analysis of the Corresponding Protein. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 97. [CrossRef]

- García-Cayuela, T.; Korany, A.M.; Bustos, I.; P. Gómez de Cadiñanos, L.; Requena, T.; Peláez, C.; Martínez-Cuesta, M.C. Adhesion Abilities of Dairy Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Showing an Aggregation Phenotype. Food Res. Int. 2014, 57, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Nwoko, E.Q.A.; Okeke, I.N. Bacteria Autoaggregation: How and Why Bacteria Stick Together. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 1147–1157. [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.; Yu, H.; Ai, L.; Wu, Z.; Guo, B.; Chen, W. Aggregation and Adhesion Properties of 22 Lactobacillus Strains. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 4252–4257. [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, H.; Alizadeh Behbahani, B.; Falah, F. Safety, Probiotic Properties, Antimicrobial Activity, and Technological Performance of Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Iranian Raw Milk Cheeses. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4094–4107. [CrossRef]

- Verruck, S.; Balthazar, C.F.; Rocha, R.S.; Silva, R.; Esmerino, E.A.; Pimentel, T.C.; Freitas, M.Q.; Silva, M.C.; da Cruz, A.G.; Prudencio, E.S. Dairy Foods and Positive Impact on the Consumer’s Health. In; 2019; pp. 95–164.

- Verruck, S.; de Liz, G.R.; Dias, C.O.; de Mello Castanho Amboni, R.D.; Prudencio, E.S. Effect of Full-Fat Goat’s Milk and Prebiotics Use on Bifidobacterium BB-12 Survival and on the Physical Properties of Spray-Dried Powders under Storage Conditions. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 643–652. [CrossRef]

- Ananta, E.; Volkert, M.; Knorr, D. Cellular Injuries and Storage Stability of Spray-Dried Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 399–409. [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, D. de L.; Thomazini, M.; Heinemann, R.J.B.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Protection of Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus acidophilus by Microencapsulation Using Spray-Chilling. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 26, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Rashidinejad, A.; Jafari, S.M. Application of Spray Dried Encapsulated Probiotics in Functional Food Formulations. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 2135–2154. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Wani, S.M.; Bhat, A.A.; Khan, A.A.; Hussain, S.Z.; Ganai, S.A.; Anjum, N. Effect of Freeze Drying and Spray Drying on Physical Properties, Morphology and in Vitro Release Kinetics of Vitamin D3 Nanoparticles. Powder Technol. 2024, 432, 119164. [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Ding, Z.; Hou, D.; Prakash, S.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Han, J. Influence of Polysaccharide as Co-Encapsulant on Powder Characteristics, Survival and Viability of Microencapsulated Lactobacillus paracasei Lpc-37 by Spray Drying. J. Food Eng. 2019, 252, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Duongthingoc, D.; George, P.; Katopo, L.; Gorczyca, E.; Kasapis, S. Effect of Whey Protein Agglomeration on Spray Dried Microcapsules Containing Saccharomyces boulardii. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1782–1788. [CrossRef]

- Zaeim, D.; Sarabi-Jamab, M.; Ghorani, B.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Liu, W.; Tromp, R.H. Microencapsulation of Probiotics in Multi-Polysaccharide Microcapsules by Electro-Hydrodynamic Atomization and Incorporation into Ice-Cream Formulation. Food Struct. 2020, 25, 100147. [CrossRef]

- Maleki, O.; Khaledabad, M.A.; Amiri, S.; Asl, A.K.; Makouie, S. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 7469 in Whey Protein Isolate-Crystalline Nanocellulose-Inulin Composite Enhanced Gastrointestinal Survivability. LWT 2020, 126, 109224. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, V.; Gamboa, A.; Caro, N.; Abugoch, L.; Gotteland, M.; Valenzuela, F.; Merchant, H.A.; Basit, A.W.; Tapia, C. Release of Prednisolone and Inulin from a New Calcium-Alginate Chitosan-Coated Matrix System for Colonic Delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 2748–2759. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, B. Differences in Physicochemical, Rheological, and Prebiotic Properties of Inulin Isolated from Five Botanical Sources and Their Potential Applications. Food Res. Int. 2024, 180, 114048. [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.-P.; Ahmad, M.S. Development of Ca-Alginate-Chitosan Microcapsules for Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Imidacloprid to Control Dengue Outbreaks. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 56, 382–393. [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, A.; Paikra, S.K.; Sutar, P.P.; Mishra, M. Characterization and Identification of Inulin from Pachyrhizus erosus and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant and In-Vitro Prebiotic Efficacy. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 328–339. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.; Meghwal, M.; Das, K. Microencapsulation: An Overview on Concepts, Methods, Properties and Applications in Foods. Food Front. 2021, 2, 426–442. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M. Probiotic Survival of Bifidobacterium lactis and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus in Pectin Microcapsule Extracted from Bitter Orange Peel for Ice Cream. Acta Sci. Pol. Tecnol. Aliment. 2025, 2, 283–294.

- Romano, N.; Mobili, P.; Zuñiga-Hansen, M.E.; Gómez-Zavaglia, A. Physico-Chemical and Structural Properties of Crystalline Inulin Explain the Stability of Lactobacillus plantarum during Spray-Drying and Storage. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Mishra, H.N. Co-Microencapsulation of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Probiotic Bacteria in Thermostable and Biocompatible Exopolysaccharides Matrix. LWT 2021, 136, 110293. [CrossRef]

- Ni, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, W.; Pang, X.; Lv, J.; Mu, W. Production and Physicochemical Properties of Food-Grade High-Molecular-Weight Lactobacillus Inulin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 5854–5862. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ahire, J.J.; R., A.; Nain, S.; Taneja, N.K. Microencapsulation of Riboflavin-Producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum MTCC 25,432 and Evaluation of Its Survival in Simulated Gastric and Intestinal Fluid. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 16, 1365–1375. [CrossRef]

| Step | Simulated conditions |

|---|---|

| Gastric Phase | Mixture of oral bolus with SGF (1:1) |

| Inclusion of CaCl2 (0.15 mM in SGF) | |

| Addition of pepsin (2000 U/mL) | |

| Incubation with agitation (2 h, 37 °C, pH 3.0) | |

| Intestinal Phase | Mixture of gastric bolus with SIF (1:1) |

| Addition of bile (10 mM of bile salts) | |

| Inclusion of CaCl2 (0.6 mM in SIF) | |

| Addition of pancreatin (trypsin activity of 100 U/mL) | |

| Incubation in agitation (2 h, 37 °C, pH 7.0) |

| Strains | Auto-aggregation (%) | hydrophobicity (%) | ||

| 3h | 6h | 24h | ||

| L. plantarum LAB 01 | 31.62 ± 4.24aB | 38.96 ± 6.21aB | 73.56 ± 6.24aA | 76.69 ± 4.68d |

| L. plantarum LAB 02 | 33.08 ± 1.36aB | 42.80 ± 0.66aB | 62.72 ± 4.57aA | 87.41 ± 3.98b |

| L. plantarum LAB 03 | 32.47 ± 2.94aB | 37.76 ± 5.06aB | 73.18 ± 6.55aA | 56.06 ± 2.25e |

| P. acidilactici LAB 04 | 30.64 ± 3.17aB | 32.44 ± 6.85aB | 74.33 ± 3.49aA | 45.70 ± 4.40f |

| L. brevis LAB 05 | 29.43 ± 0.18aB | 42.96 ± 2.44aB | 78.44 ± 8.73aA | 99.67 ± 0.09a |

| L. casei LAB 06 | 23.53 ± 0.98aB | 28.41 ± 1.03aB | 68.84 ± 8.83aA | 95.38 ± 0.61ab |

| L. casei LAB 07 | 22.08 ± 5.14aB | 39.68 ± 0.45aAB | 65.69 ± 11.15aA | 97.72 ± 0.20a |

| L. casei LAB 08 | 30.72 ± 11.21aA | 34.10 ± 16.00aA | 78.76 ± 4.12aA | 78.66 ± 0.63cd |

| L. casei LAB 09 | 36.94 ± 0.29aB | 35.83 ± 3.37aB | 77.82 ± 3.09aA | 53.37 ± 0.87ef |

| L. casei LAB 10 | 20.29 ± 7.38aB | 27.50 ± 6.66aB | 75.04 ± 6.82aA | 93.16 ± 0.74ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).