Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Microclimate Measurement Equipment

2.3. Measurement of Infection Level in Plants

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microclimatic Parameters Inside the Greenhouse

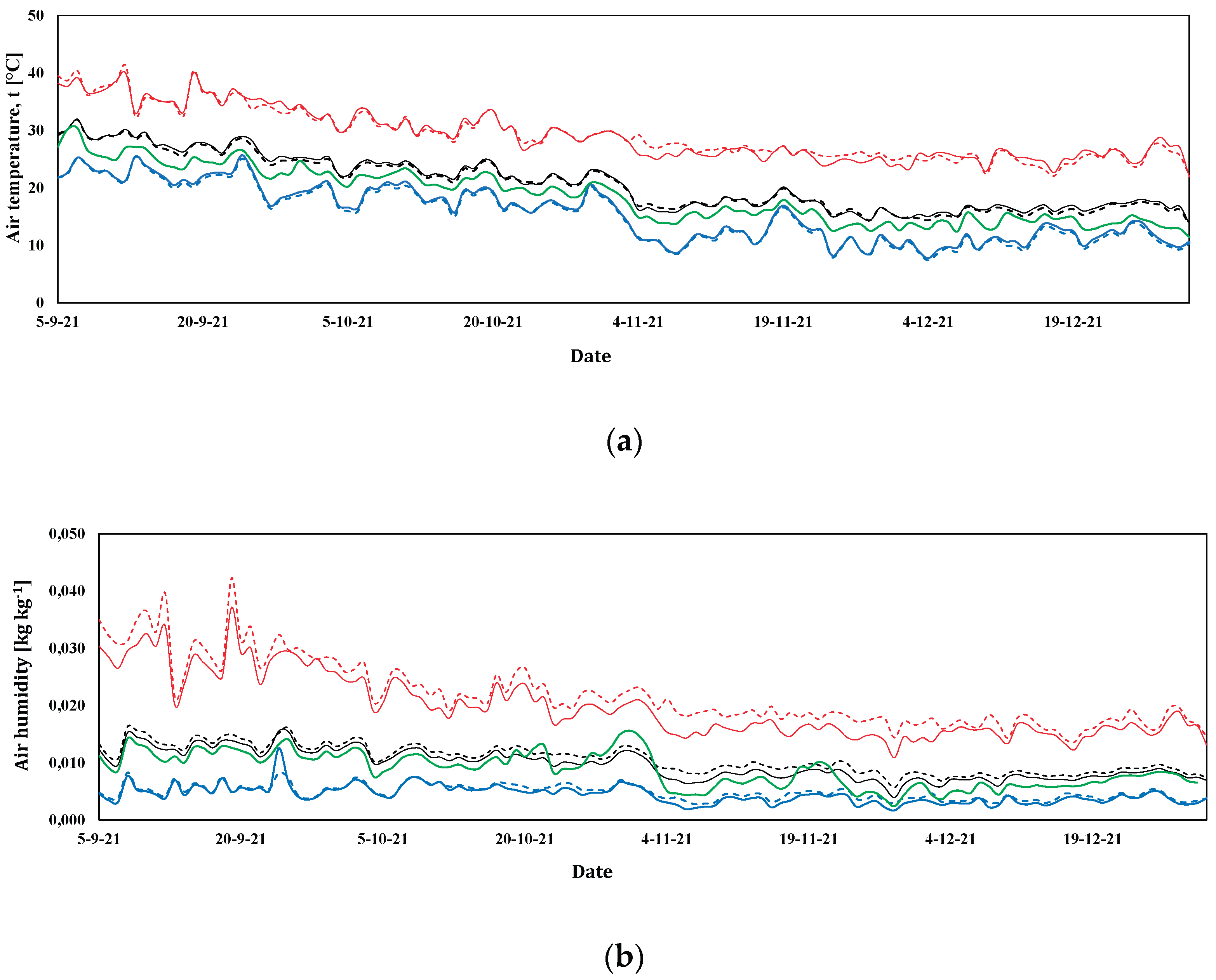

3.1.1. Autumn-Winter Crop Season

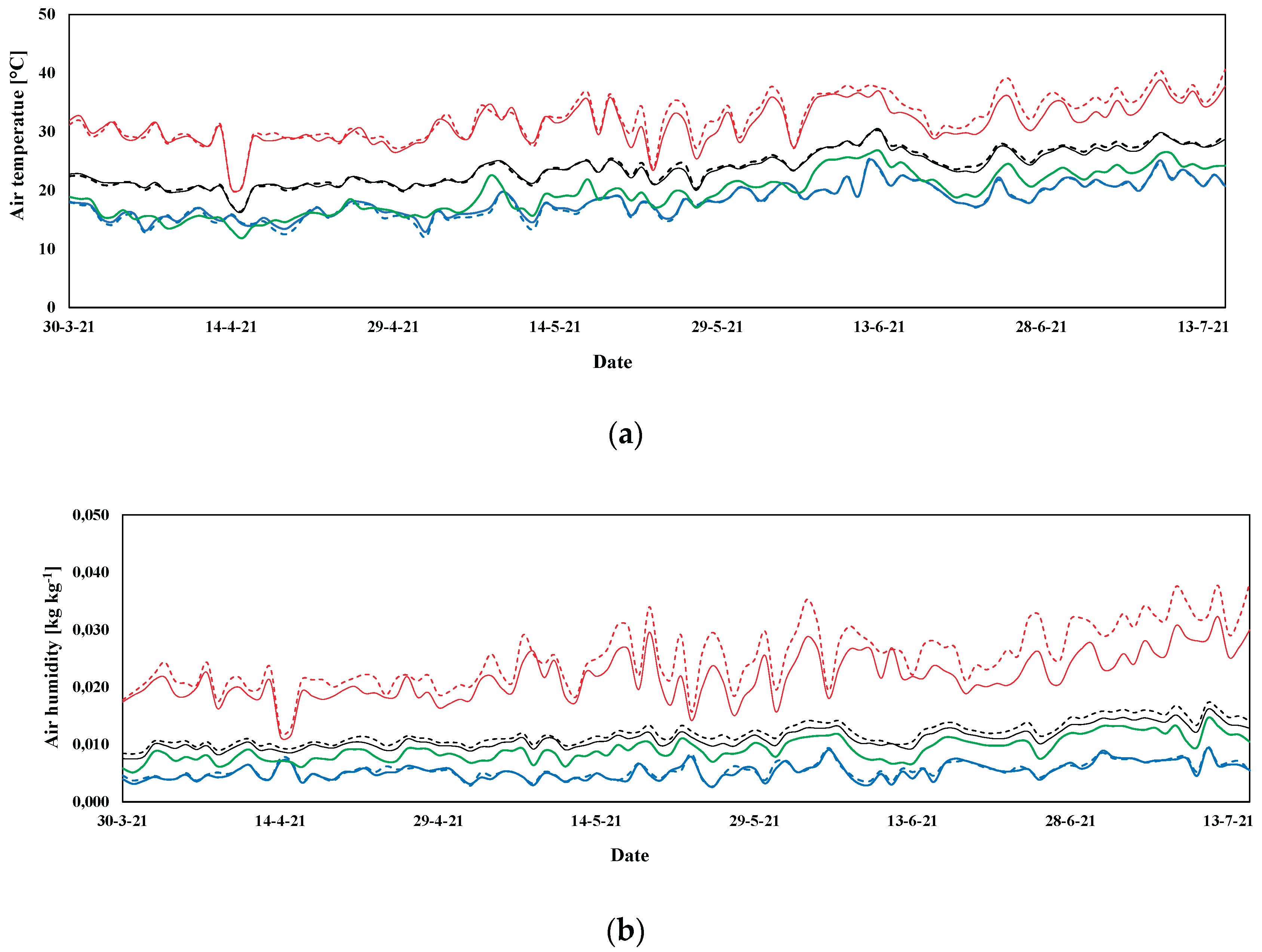

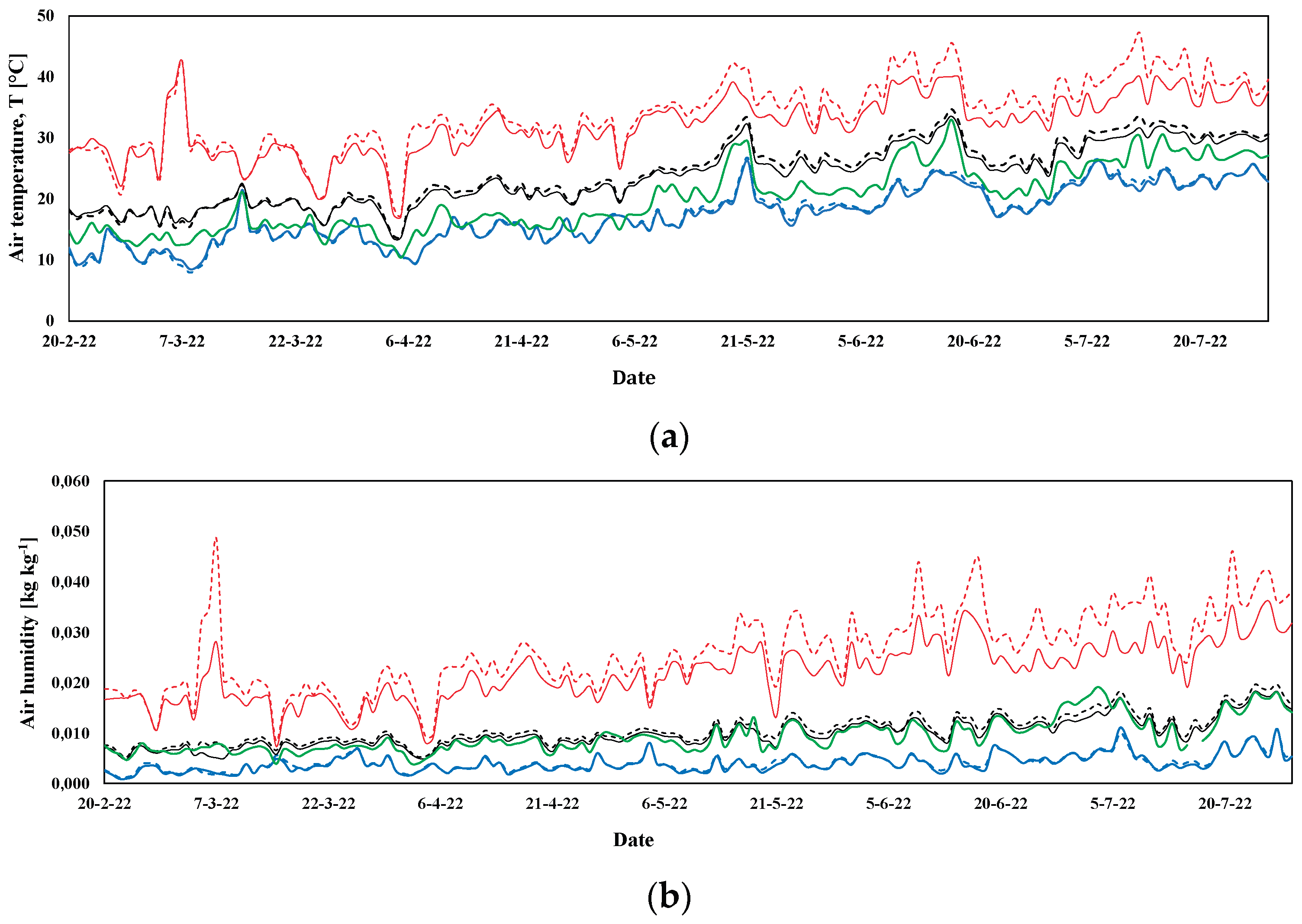

3.1.2. Spring-Summer Crop Season

3.2. Fungal Diseases

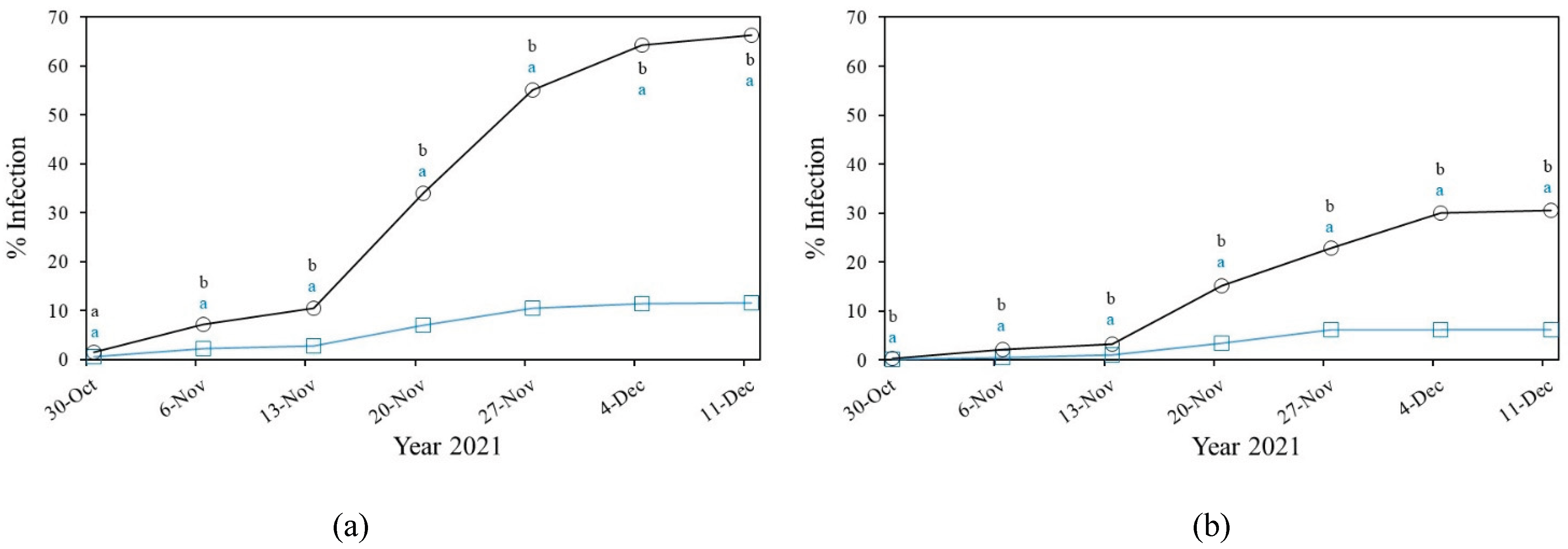

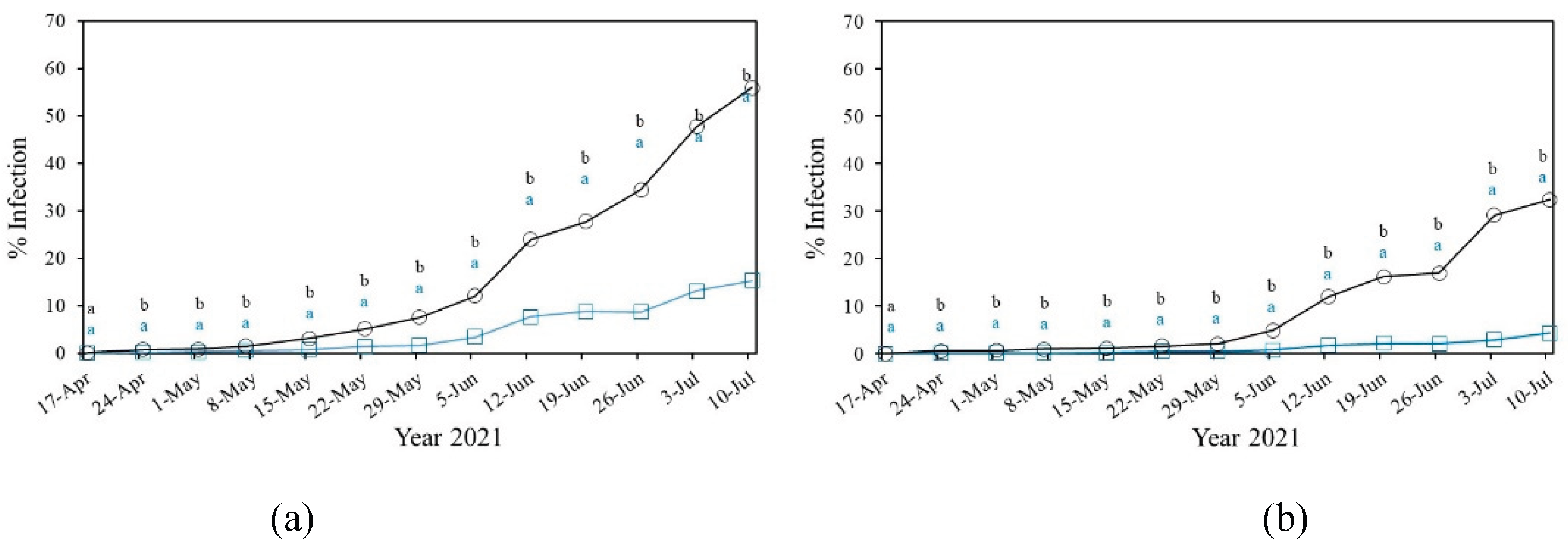

3.2.1. Powdery Mildew

3.2.1.1. Powdery Mildew in Cucurbitaceae

Powdery Mildew in Solanacea

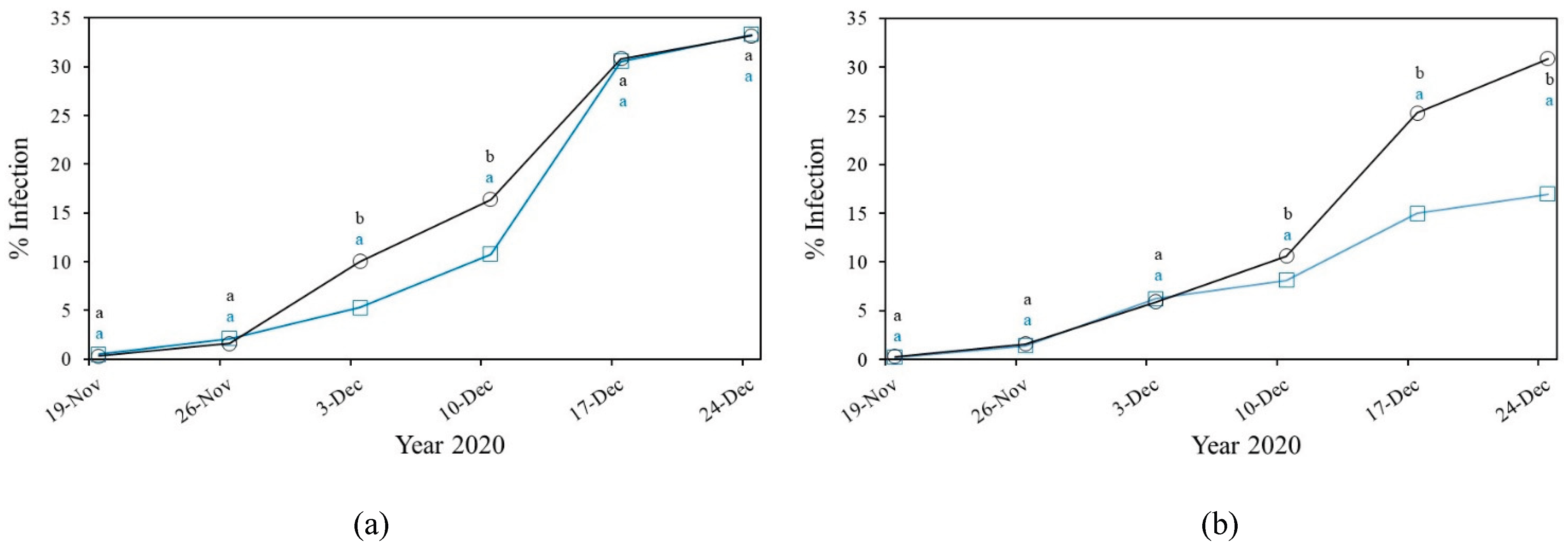

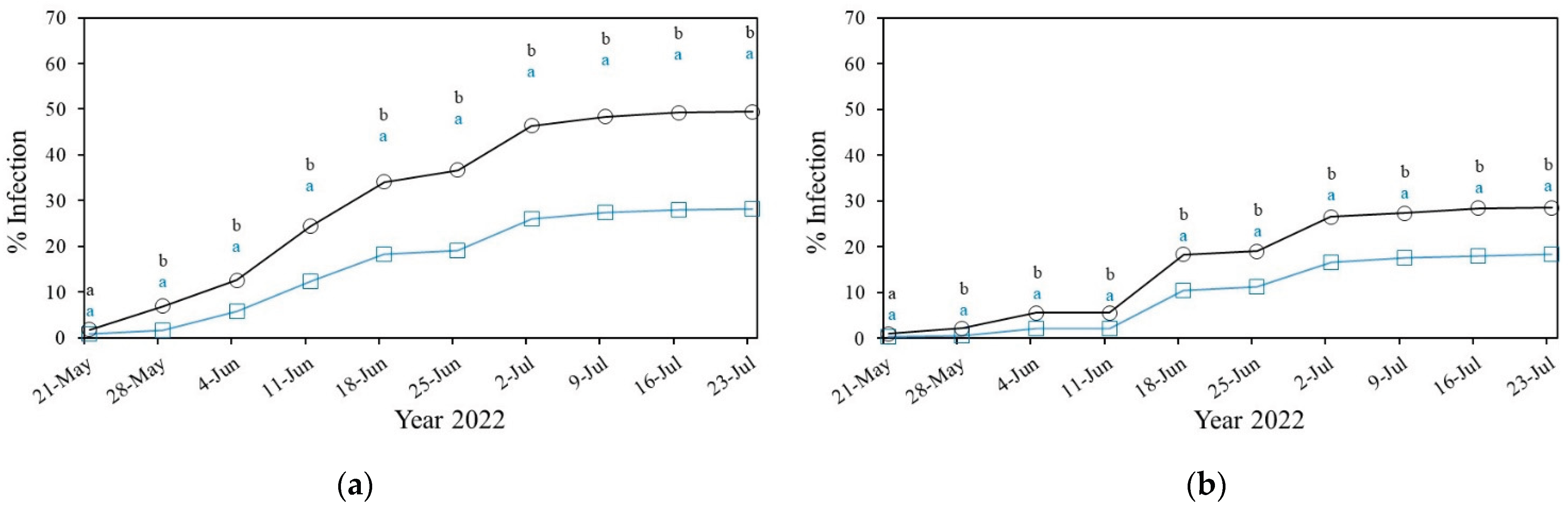

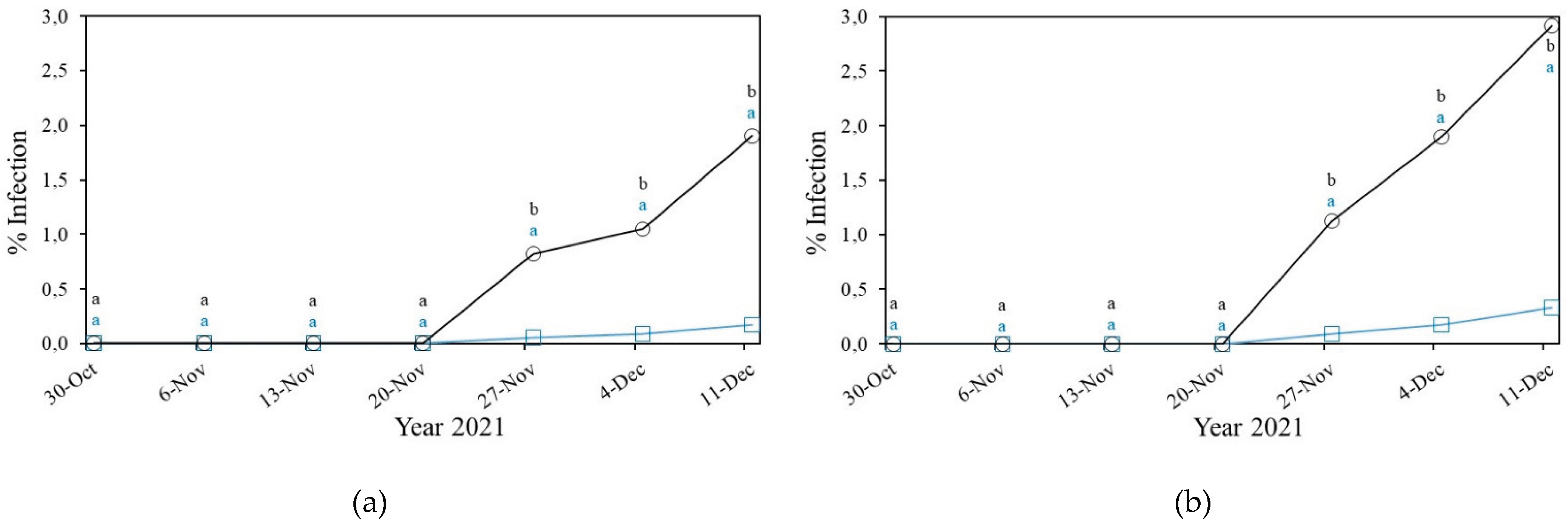

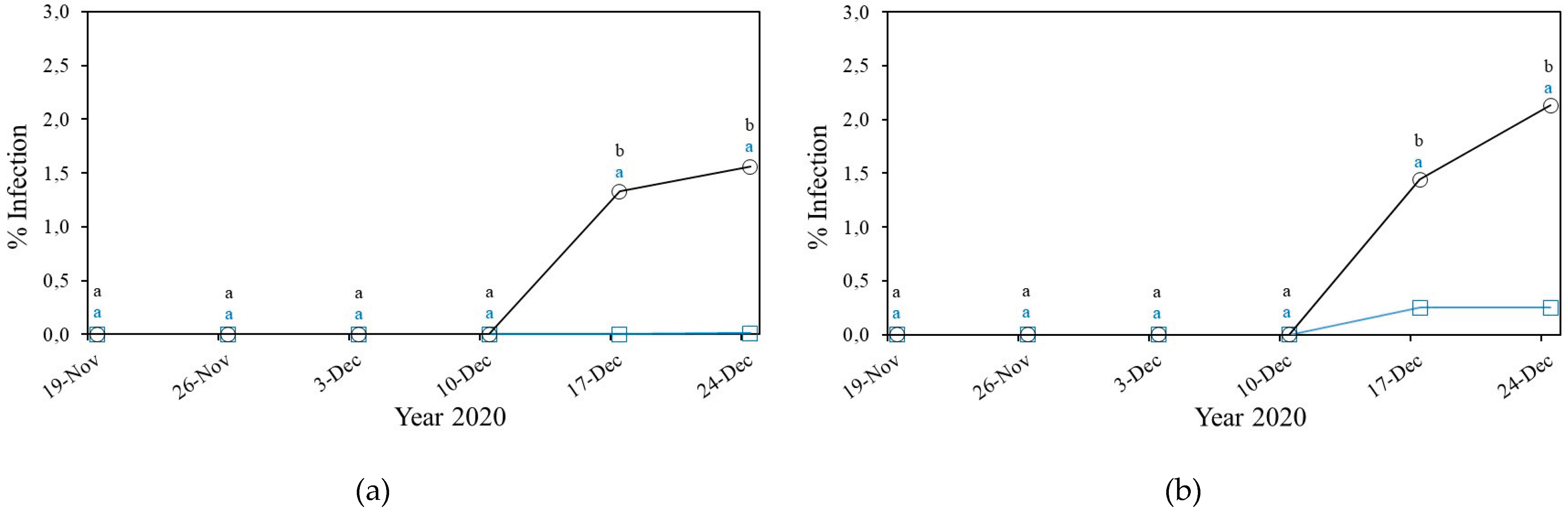

3.2.2. Downey Mildew

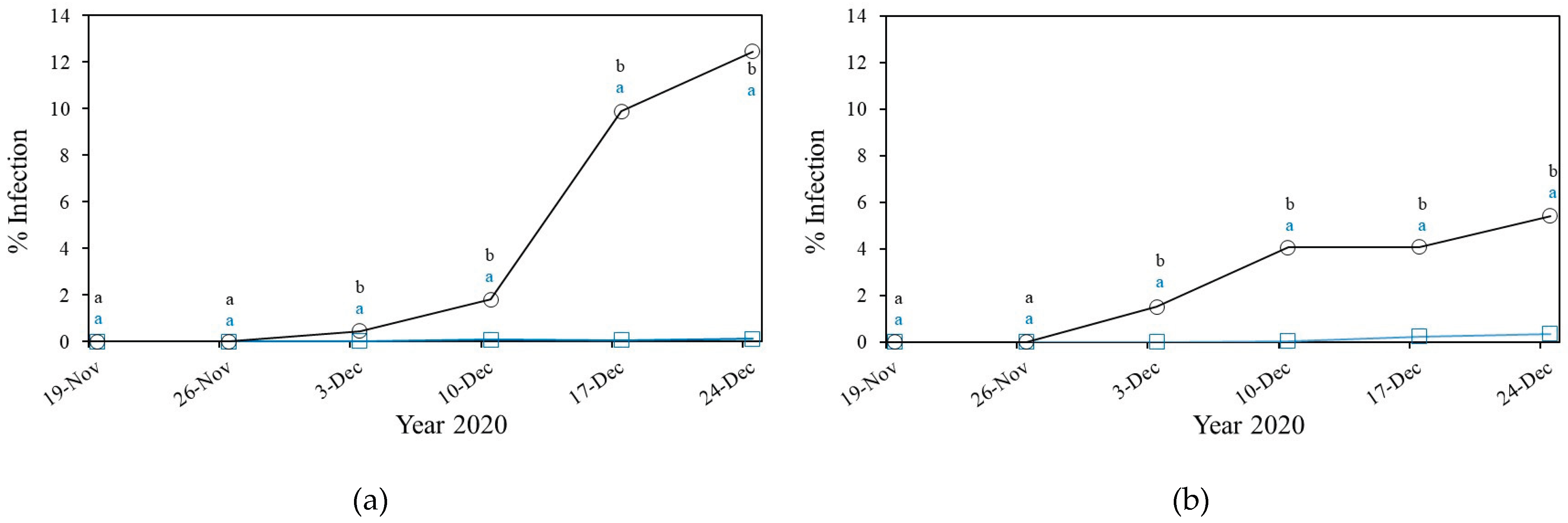

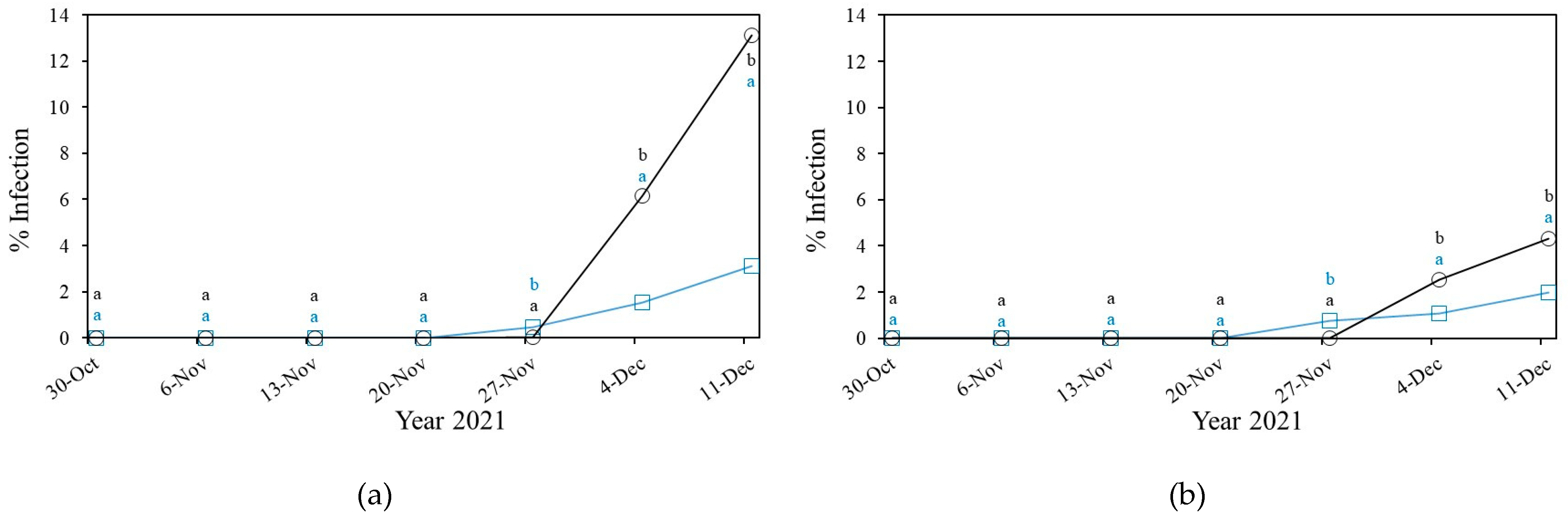

3.2.3. Gummy Stem Blight

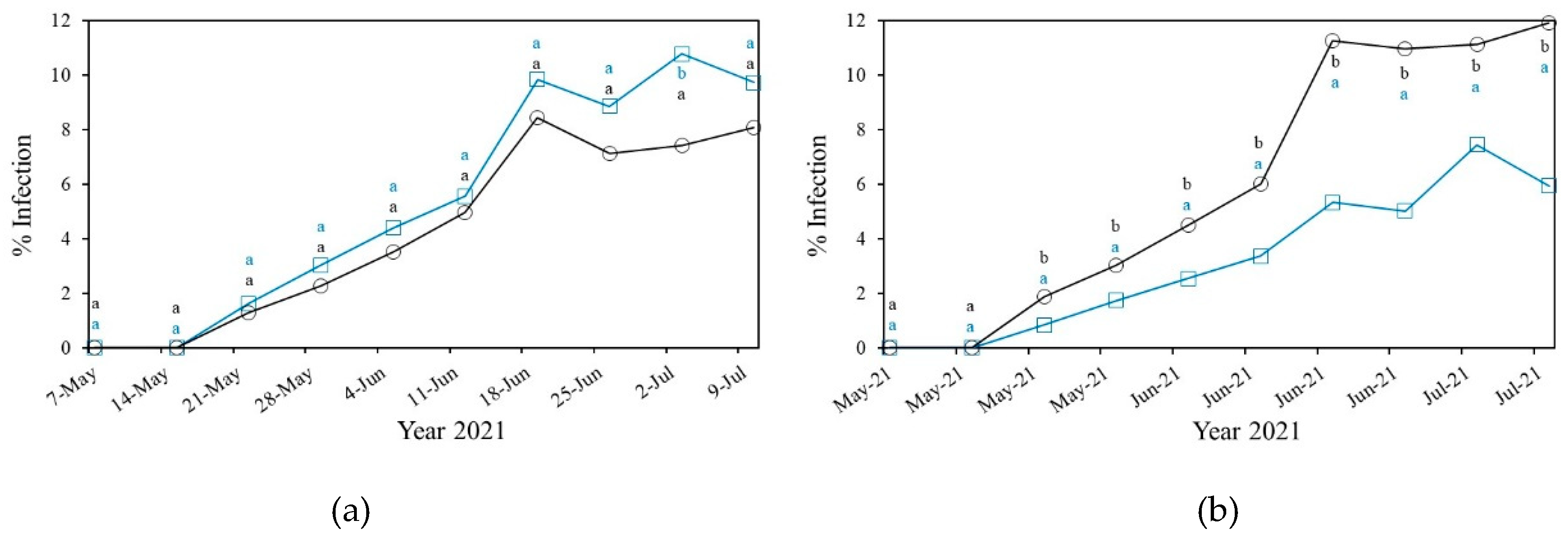

3.2.4. Early Blight in Tomato

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- The use of double roofs with sunlight spectrum photoconverter film combined with increased natural ventilation in the greenhouse reduced the development of downy mildew (Pseudoperonospora cubensis and Leveillula taurica), powdery mildew (Shaerotheca fuliginea), gummy stem blight (Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum) and early blight (Alternaria solani) fungal diseases in cucumber, tomato and pepper crops.

- -

- The double roof combined with increased natural ventilation significantly decreased the free water in the crop, significantly reduced the infection rate and the development of downy mildew (Pseudoperonospora cubensis).

- -

- The double roof combined with increased natural ventilation does not appear to have a significant effect on early blight, although it is not possible to reach a clear conclusion, as this disease appeared due to a climatic anomaly in the area and could only be studied during one growing season.

- -

- Deficit irrigation (20% less than standard irrigation) reduced the infection rate of downy mildew, powdery mildew and gummy stem blight, but not early blight.

- -

- Passive climate control techniques in greenhouses could help to control or reduce the levels of fungal diseases (downy mildew, powdery mildew, gummy stem blight and early blight), avoiding the emergence of resistance to the lower number of active substances allowed for fungal disease control in European horticultural crops.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernández, J.; Bonachela, S.; Granados, M.R.; López, J.C.; Magán, J.J.; Montero, J.I. Microclimate and agronomical effects of internal impermeable screens in an unheated Mediterranean greenhouse. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 163, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Díaz, F.J.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Camacho-Ferre, F.; Tello-Marquina, J.C. The management of agriculture plastic waste in the framework of circular economy: The case of the Almería greenhouse (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Neira, D.; Soler-Montiel, M.; Delgado-Cabeza, M.; Reigada, A. Energy use and carbon footprint of tomato production in heated multi-tunnel greenhouses in Almería within an exporting agri-food system context. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudoin, W.; Nersisyan, A.; Shamilov, A.; Hodder, A.; Gutierrez, D.; De Pascale, S.; Nicola, S.; Gruda, N.; Urban, L. Good Agricultural Practices for Greenhouse Vegetable Production in South East European Countries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 1–449. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, D.L.; Belmonte, L.J.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; López, A. Greenhouse Agriculture in Almería: A Comprehensive Techno-Economic Analysis; Cajamar Caja Rural: Almería, Spain, 2016; 408pp. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Valera, D.L.; Álvarez, A.J. Measurement and simulation of climate inside Almería-type greenhouses using computational fluid dynamics. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 125, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Teruel, M.A.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; López-Martínez, A.; Marín-Membrive, P.; Peña-Fernández, A.; Valera-Martínez, D.L. Influence of different cooling systems on the microclimate, photosynthetic activity and yield of tomato crops in Mediterranean greenhouses. Agronomy 2022, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemek, B.; Demir, Y.; Uzun, S.; Ceyhan, V. Effects of different greenhouse covering materials on energy requirement, growth and yield of aubergine. Energy 2006, 31, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, F. Sistemas pasivos de climatización en periodos fríos. Dobles techos [In Spanish]. In Documentos Técnicos de Cajamar; Cajamar Caja Rural: Almería, Spain, 2015; pp. 10–13. Available online: https://publicacionescajamar.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/sistemas-pasivos-de-climatizacion.pdf.

- Papadakis, G.; Briassoulis, D.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.; Vox, G.; Feuilloley, P.; Stoffers, J.A. Radiometric and thermal properties of greenhouse covering materials. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 2000, 77, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgren, B. Aging tests with covering materials for greenhouses. Acta Hortic. 1985, 170, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.S.; Guo, H.; Tanino, K. Energy-saving techniques for reducing the heating cost of conventional greenhouses. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 178, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.J.; Bomford, M.K. Row covers moderate diurnal temperature flux in high tunnels. Acta Hortic. 2013, 987, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Teruel, M.Á.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Peña-Fernández, A.; López-Martínez, A.; Valera-Martínez, D.L. Effect of diffuse film covers on microclimate, growth and production of tomato in a Mediterranean greenhouse. Agronomy 2021, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abak, K.; Basçetinçelik, A.; Baytorun, N.; Altuntaş, Ö.; Öztürk, H.H. Influence of double plastic cover and thermal screen on greenhouse temperature, yield and quality of tomato. Acta Hortic. 1994, 366, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, K. Action spectra for photosynthesis in higher plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 1976, 17, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.; Smith, H. Linear relationship between phytochrome photoequilibrium and growth in plants under simulated natural radiation. Nature 1976, 262, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.M.; Bakx, E.J. Growth and flower development in roses as affected by light. Acta Hortic. 1997, 418, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.O.; Matsui, S.; Ichihashi, S. Effects of light quality on seed germination and seedling growth of Cattleya orchids in vitro. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 68, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanyu, H.; Shoji, K. Combined effects of blue light and supplemental far-red light and increasing red light with constant far-red light on growth of kidney bean under narrow-band light sources. Environ. Control Biol. 2000, 38, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. Phytochromes and light signal perception by plants: An emerging synthesis. Nature 2000, 407, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y.; Wada, E.; Fukumoto, Y.; Aruga, H.; Shimoi, Y. Effect of spectrum conversion covering film on cucumber grown in soilless culture. Acta Hortic. 2012, 956, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.I.; Kim, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Namgoong, J.W.; Hwang, T.G.; Kim, J.P.; Son, J.E. Quantitative evaluation of spectrum conversion films and plant responses under simulated solar conditions. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bashir, S.M.; Al-Harbi, F.F.; Elburaih, H.; Al-Faifi, F.; Yahia, I.S. Red photoluminescent PMMA nanohybrid films for modifying solar radiation inside greenhouses. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, K.; Yoshida, K.; Shimasaki, K.; Murakami, K.; Yasutake, D.; Kitano, M. Spectrum conversion film for regulation of plant growth. J. Fac. Agric. 2008, 53, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemarié, S.; Guérin, V.; Jouault, A.; Proost, K.; Cordier, S.; Guignard, G.; Demotes-Mainard, S.; Bertheloot, J.; Sakr, S.; Peilleron, F. Productivity of melon and potato crops under optically active greenhouse films. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1296, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, N.; Montero, J.I. Environmental control and crop production in Mediterranean greenhouses. Acta Hortic. 2008, 797, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Valera, D.L.; Peña, A.A.; Gil, J.A.; López, A. A study of natural ventilation in an Almería-type greenhouse with insect screens by means of tri-sonic anemometry. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 104, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y. Combined effects of temperature, leaf wetness and inoculum concentration on cucumber infection by Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Can. J. Bot. 1977, 55, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharis, V.L.; Kemp, T.R.; Knavel, D.E. Host plant-emitted volatiles and susceptibility of Cucumis and Cucurbita spp. to Mycosphaerella melonis. Sci. Hortic. 1982, 17, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, N.V.; Wehner, T.C.; Thomas, C.E.; Doruchowski, R.W.; Shetty, V.K.P. Evidence for downy mildew races in cucumber tested in Asia, Europe and North America. Sci. Hortic. 2002, 94, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtuoso, M.C.S.; Valente, T.S.; Costa-Silva, E.H.; Trevisan Braz, L.; de Cassia Panizzi, R.; Forlan-Vargas, P. Implications of inoculation method and environment in selecting melon genotypes resistant to Didymella bryoniae. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 300, 111066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Z.A.; Bhat, M.A.; Ahangar, Z.A.; Badri, G.; Mir, H.; Mohi-u-Din, F. Survival of Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum under temperate conditions. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 2632–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, F.J.; Bailey, B.J.; Meneses, J.F. Effect of nocturnal ventilation on the occurrence of Botrytis cinerea in Mediterranean unheated tomato greenhouses. Crop Prot. 2012, 32, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargues, A.C.; Campo, J.L.; Monteiro, A. Effect of greenhouse double roof on tomato growth and yield. Acta Hortic. 1994, 357, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hückelhoven, R. Powdery mildew susceptibility and biotrophic infection strategies. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 245, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-García, A.; Romero, D.; Fernández-Ortuño, D.; López-Ruiz, F.; de Vicente, A.; Torés, J.A. Podosphaera xanthii, a constant threat to cucurbits. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeda, A.; Krístková, E.; Sedláková, B.; McCreight, J.D.; Coffey, M.D. Cucurbit powdery mildews: Methodology for race determination. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 144, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, W.R. Managing Diseases in Greenhouse Crops; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ortuño, D.; Torés, J.A.; de Vicente, A.; Pérez-García, A. Field resistance to QoI fungicides in Podosphaera xanthii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeda, A.; Cohen, Y. Cucurbit downy mildew: Biology, epidemiology and control. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 129, 157–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Van den Langenberg, K.M.; Wehner, T.C.; Ojiambo, P.S.; Hausbeck, M.K.; Quesada-Ocampo, L.M. Resurgence of Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savory, E.A.; Granke, L.L.; Quesada-Ocampo, L.M.; Varbanova, M.; Hausbeck, M.K.; Day, B. The cucurbit downy mildew pathogen Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.E.; Turner, A.N.; Brewer, M.T. Evolutionary history and host range variation of Stagonosporopsis species. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bruton, B.D.; Biles, C.L. Cell wall-degrading enzymes of Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum related to fungal growth and virulence. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 139, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmini, G.; Song, R.; Wehner, T.C. Inheritance of resistance to gummy stem blight in watermelon. HortScience 2017, 52, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennberger, G.; Turechek, W.W.; Keinath, A.P. Dynamics of ascospore dispersal of Stagonosporopsis citrulli. Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 1908–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.; Alioto, D.; Tripodi, P. Biotic stresses in pepper (Capsicum spp.): Genetic resistance and breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Nonomura, T.; Appiano, M.; Pavan, S.; Matsuda, Y.; Toyoda, H.; Wolters, A.M.A.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bai, Y.; Vinatzer, B.A. Loss of function in Mlo orthologs reduces powdery mildew susceptibility in pepper and tomato. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guigón López, C.; Muñoz Castellanos, L.N.; Flores Ortiz, N.A.; González, J.A. Control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) in pepper using biological agents. BioControl 2019, 64, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindo, K.; Evenhuis, A.; Kempenaar, C.; Pombo Sué, C.; Zhan, X.; Teklu, M.G.; Kessel, G. Holistic pest management against early blight disease: A review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 3871–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, I.E.; Knapp, S.; Spooner, D.M. New species of wild tomatoes from northern Peru. Syst. Bot. 2005, 30, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, K.P.; Ullah, N.; Saleem, M.Y.; Iqbal, Q.; Asghar, M.; Khan, A.R. Evaluation of tomato genotypes for resistance to early blight caused by Alternaria solani. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotem, J.; Reichert, I. Dew as a principal moisture factor enabling early blight epidemics. Plant Dis. Rep. 1964, 48, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, M.; Zehra, A.; Dubey, M.K.; Aamir, M.; Gupta, V.K.; Upadhyay, R.S. Biochemical changes in tomato infected by Alternaria alternata. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raviv, M.; Reuveni, R. Fungal photomorphogenesis and disease control using photoselective greenhouse covers. HortScience 1998, 33, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Li, F.; Xie, H.Y.; Liu, X.Z. Induction of sporulation in plant pathogenic fungi. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthaparan, A.; Solhaug, K.A.; Bjugstad, N.; Gislerød, H.R.; Gadoury, D.M.; Stensvand, A. Suppression of powdery mildews by UV-B radiation. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.Y.; Qi, Y.L.; Cai, L. Induction of sporulation in plant pathogenic fungi. Mycology 2012, 3, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrios, G.N. Plant Pathology, 5th ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Nonomura, T.; Bóka, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Visser, R.G.F.; Toyoda, H.; Kiss, L.; Bai, Y. Detection and quantification of Leveillula taurica growth in pepper leaves. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvatha Reddy, P. Sustainable Crop Protection under Protected Cultivation; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, H.; Zhu, H.; Deng, Y.; Han, X. Tomato disease classification using multimodal deep learning. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C.; Steiner, U.; Dehne, H.W.; Lindenthal, M. Thermal imaging of cucumber leaves affected by downy mildew. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elad, Y.; Messika, Y.; Brand, M.; David, D.R.; Sztejnberg, A. Effect of colored shade nets on pepper powdery mildew. Phytoparasitica 2007, 35, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Teruel, M.Á.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Peña-Fernández, A.; López-Martínez, A.; Valera-Martínez, D.L. Effect of diffuse film covers on tomato growth and production. Agronomy 2021, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos-Sánchez, E.; Moreno-Teruel, M.Á.; López-Martínez, A.; Molina-Aiz, F.D.; Baptista, F.; Marín-Membrive, P.; Valera-Martínez, D.L. Effect of greenhouse film cover on fungal diseases in tomato and pepper. Agronomy 2023, 13, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, K.R.; Ocamb, C.M.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Nackley, L.L. Reducing powdery mildew in high-tunnel tomato production in Oregon with ultraviolet-C lighting. HortTechnology 2023, 33, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthaparan, A.; Stensvand, A.; Solhaug, K.A.; Torre, S.; Mortensen, L.M.; Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Gislerød, H.R. Suppression of powdery mildew (Podosphaera pannosa) in greenhouse roses by brief exposure to supplemental UV-B radiation. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthaparan, A.; Stensvand, A.; Solhaug, K.A.; Torre, S.; Telfer, K.H.; Ruud, A.K.; Mortensen, L.M.; Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Gislerød, H.R. Suppression of cucumber powdery mildew by supplemental UV-B radiation in greenhouses is influenced by background radiation quality. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthaparan, A.; Solhaug, K.A.; Stensvand, A.; Gislerød, H.R. Daily light integral and daylight quality: Potentials and pitfalls of nighttime UV treatments on cucumber powdery mildew. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2017, 175, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suthaparan, A.; Pathak, R.; Solhaug, K.A.; Gislerød, H.R. Wavelength-dependent recovery of UV-mediated damage: Implications for optical-based powdery mildew management. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2018, 178, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Ergon, Å.; Stensvand, A.; Gislerød, H.R.; Solhaug, K.A.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Suthaparan, A. Functional characterization of Pseudoidium neolycopersici photolyase reveals mechanisms underlying the efficacy of nighttime UV treatments on powdery mildew suppression. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fondevilla, S.; Rubiales, D. Powdery mildew control in pea: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, R.; Fleitas, M.C.; Castro, A.C.; Schierenbeck, M. How foliar fungal diseases affect nitrogen dynamics, milling, and end-use quality of wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 569401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Beest, D.E.; Paveley, N.D.; Shaw, M.W.; van den Bosch, F. Disease–weather relationships for powdery mildew and yellow rust on winter wheat. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lage, D.A.C.; Marouelli, W.A.; Café-Filho, A.C. Management of powdery mildew and behavior of late blight under different irrigation configurations in organic tomato. Crop Prot. 2019, 125, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotem, J.; Cohen, Y.; Bashi, E. Host and environmental influences on sporulation in vivo. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1978, 16, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Hamza, A.; Derbalah, A. Recent approaches for controlling downy mildew of cucumber under greenhouse conditions. Plant Prot. Sci. 2016, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanetis, L.; Holmes, G.J.; Ojiambo, P.S. Survival of Pseudoperonospora cubensis sporangia exposed to solar radiation. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, T.C.; Shetty, N.V. Screening the cucumber germplasm collection for resistance to gummy stem blight in North Carolina field tests. HortScience 2000, 35, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuley, I.K.; Nielsen, B.J.; Labouriau, R. Resistance status of cultivated potatoes to early blight (Alternaria solani) in Denmark. Plant Pathol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sector | Double roof type | Dimensions | SC | SVS | SVR | SV/SC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West | Spectrum conversion film | 24.3 m × 20.1 m | 480 | 77.49 | 47.25 | 26.0 |

| East | Without double roof | 24.3 m × 25.1 m | 600 | 38.90 | 60.75 | 16.6 |

| Crop | Commercial Variety | Data of Transplant | Double Roof Installation | Final Crop Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L) | Insula RZ F1 | 07/09/2020 | 12/10/2020 | 02/01/2021 |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L) | Ramyle RZ F1 | 07/02/2021 | 28/01/2021 | 15/07/2021 |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L) | Insula RZ F1 | 05/09/2021 | 20/10/2021 | 02/01/2022 |

| Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) | Bemol RZ F1 | 20/02/2022 | 19/02/2022 | 29/07/2022 |

| Crop | Active substance | Application data | Applied dose | Application method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cucumber 2020-21 | Azoxistrobin | 09/10/2020 | 45cc/100L | Aerial |

| Azoxistrobin | 05/11/2020 | 75cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Ciflufenamida | 17/11/2020 | 20cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Azoxistrobin | 25/11/2020 | 75cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Sulphur | 01/12/2020 | 300cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Metrafenona | 01/12/2020 | 30cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Tomato 2021 | Sulphur | 17/04/2021 | 150cc/100L | Aerial |

| Cucumber 202-22 | Azoxistrobin | 01/11/2021 | 20cc/100L | Aerial |

| Azoxistrobin | 04/11/2021 | 70cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Azoxistrobin | 23/11/2021 | 80cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Pepper 2022 | Azoxistrobin | 08/06/2022 | 80cc/100L | Aerial |

| Azoxistrobin | 17/06/2022 | 80cc/100L | Aerial | |

| Metrafenona | 24/02/2022 | 30cc/100L | Aerial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).