1. Introduction

Over the past decades, laser systems have found increasing applications in biomedical fields, offering controlled, selective, and minimally invasive energy delivery for the treatment of various pathologies [

1]. Optical fibers play a key role in these applications by guiding laser radiation to target tissues in a controlled manner.

In urology, minimally invasive thermal ablation techniques are increasingly explored for the treatment of pathologies such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and localized prostate cancer. BPH, in particular, affects a significant proportion of aging men, and its management often requires tissue debulking to relieve urinary symptoms 1. Traditional surgical options, though effective, can be associated with bleeding, prolonged recovery, and functional side effects. In contrast, focal laser ablation represents a promising alternative, enabling precise delivery of energy through optical fibers to induce coagulative necrosis with limited harm to surrounding structures 34. This minimally invasive approach allows treatments to be tailored to the patient’s pathology, ranging from debulking to complete ablation, while preserving surrounding healthy tissue and critical anatomical structures. Furthermore, its versatility, reproducibility, and compatibility with advanced planning and guidance systems make it a safe and efficient option for a variety of clinical scenarios [

8].

Various modalities beyond laser ablation have been applied clinically, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [

4], microwave ablation (MWA) [

5], high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) [

6], and cryotherapy [

7], which can be used for focal treatments of the prostate. Among these energy-based techniques, microwave ablation (MWA) has attracted increasing interest in recent years. While microwave systems can provide rapid heating and relatively large ablation volumes, they are often associated with increased system complexity and higher costs. Moreover, the reduced sensitivity of microwave energy deposition to tissue electrical properties, although advantageous in some settings, may limit fine control of the spatial energy distribution, potentially resulting in less precise ablation margins. High intratumoral temperatures and large ablation zones may also increase the risk of collateral thermal damage, particularly in anatomically confined regions or near critical structures. These limitations highlight the need for alternative minimally invasive techniques, such as focal laser ablation, which offer improved spatial selectivity and controlled energy delivery [

3].

However, each of these techniques still presents important limitations. For instance, HIFU, despite its non-invasiveness, has shown variable oncologic control and functional outcomes, with long-term efficacy remaining debated [

6]. Cryotherapy, which relies on repeated freeze–thaw cycles, may result in collateral tissue injury and requires careful probe placement to minimize damage to adjacent structures [

7]. More broadly, systematic reviews indicate that focal therapies, including laser-based approaches, are generally safe and effective in preserving function; however, oncologic outcomes and recurrence rates remain highly variable across techniques, patient selection criteria, and study designs [

4].

In laser-based approaches, most clinical implementations use conventional flat tip fibers, which emit light in a forward direction and often lead to elongated ablation zones rather than more uniformly shaped lesions, as observed in our experiments. Alternative fiber geometries such as conical or spherical (ball) tips have been proposed to improve energy distribution; however, systematic experimental evaluations in biological tissues are still limited in the present study.

Moreover, important fiber parameters like core diameter and numerical aperture have not been exhaustively studied in combination with tip shape to understand their impact on ablation morphology and thermal behaviour. This knowledge gap hinders the design of optimized fiber-based delivery systems for more predictable and efficient ablation.

In this study, we present a systematic experimental comparison of eight different optical fibers varying in core size, numerical aperture, and tip geometry (flat, conical radial-emitting, spherical). Using calf liver as a tissue surrogate for human prostate due to its similar optical and thermal properties we performed ablation experiments with a diode-laser system (1064 nm) integrated in the Echolaser platform [

8], evaluating single-fiber, dual-fiber, and pull-back irradiation strategies. We further explore a novel method to achieve uniform, circular ablations by coupling a flat tip fiber with a balloon catheter filled with a hydroxyapatite-based diffusing medium.

Our results provide new insights into how fiber design influences ablation volume and temperature distribution, with potential impact for the development of minimally invasive, fiber-based laser therapies in urological applications.

2. Materials

2.1. Instruments Used and Optical Fibers Tested

All experiments were conducted at the Elesta Laboratory in Calenzano (Italy) using the following instrumentation:

Two Echolaser X4 systems were employed: one unit was used for tests involving Elesta–Oberon optical fibers equipped with an SMA905 connector featuring a 0.1-mm setback, while the second unit was used for tests performed with Oberon, Thorlabs or Asclepion optical fibers with a standard SMA905 connector;

Ultrasound imaging was carried out using an Esaote MyLabOmega system equipped with a linear probe;

Temperature monitoring was performed using an Agilent Data Acquisition/Switch Unit (SN US37034947) in combination with two type-K thermocouples: one RS thermocouple (SN 6212170) with a 0.3-mm probe diameter, 2-m length, and +600 °C range mounted on a 14G needle, and a second RS thermocouple (SN 8047990) with a 0.076-mm probe diameter, 2-m length, and +260 °C range mounted on a 21G needle;

A Tsunami Medical balloon catheter (PBKK 11/20-20; outer diameter 11G, length 20 cm, balloon volume 5.5 ml) and a Tsunami Medical inflation kit (RK07) were used to perform balloon-assisted procedures;

Optical power measurements were obtained using an Ophir power meter (7Z01565);

Optical fibers were prepared using a Jonard Tools adjustable wire stripper (20–30 AWG, ST-500).

Eight multimode optical fibers were evaluated. Their characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

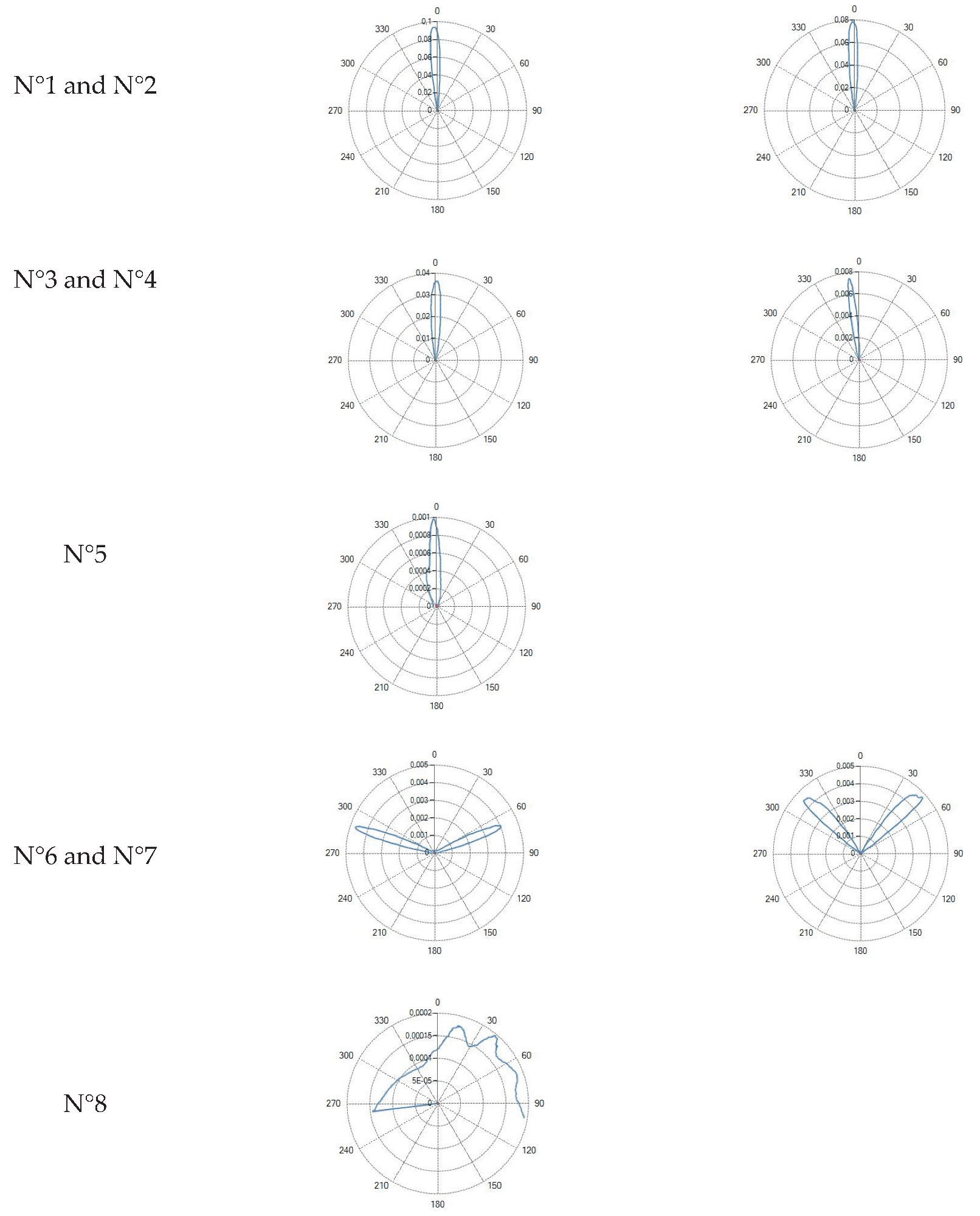

Flat tip (Fiber ID: N°1, N°2, N°3, N°4 and N°5):

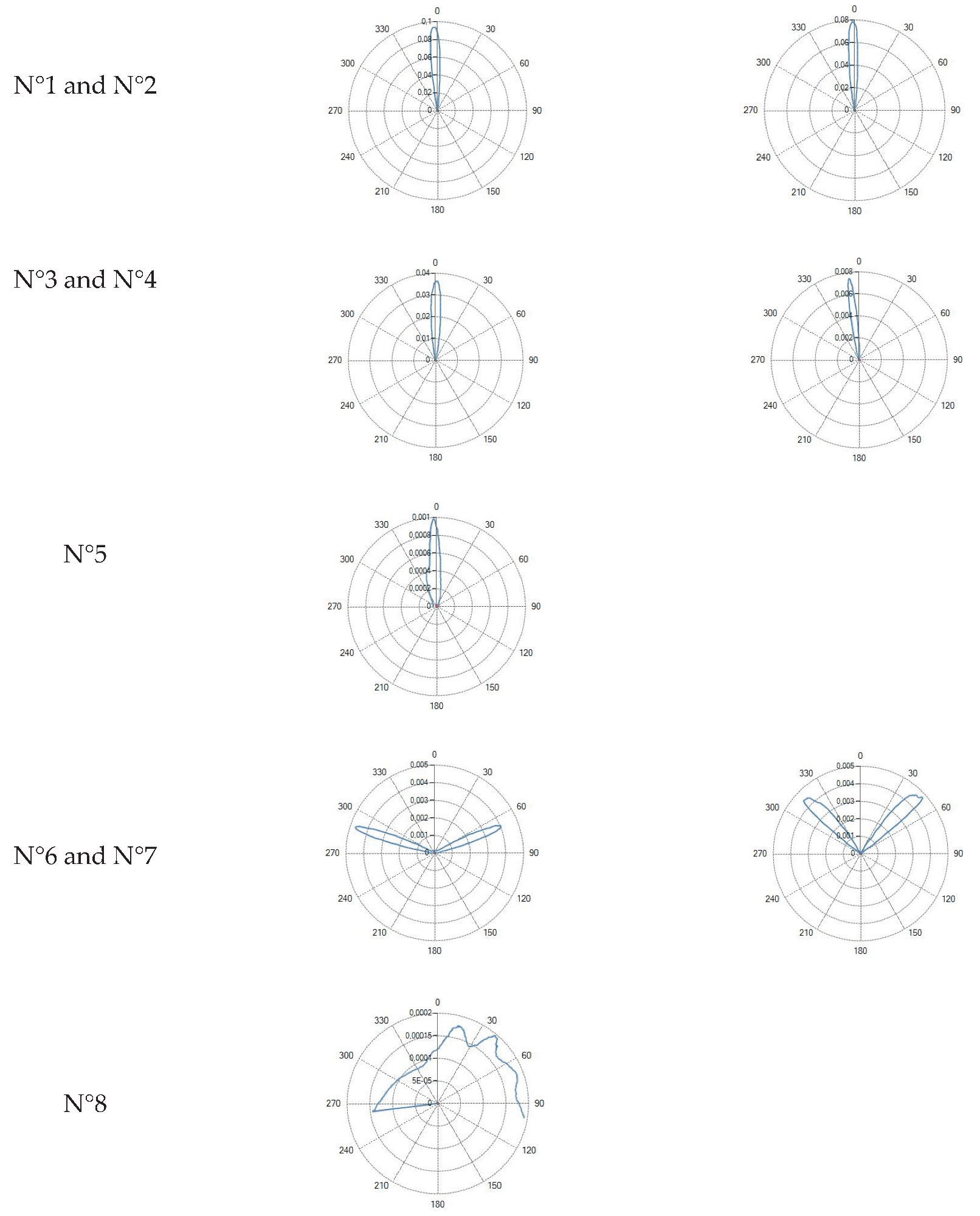

The flat tip fibers exhibited a single central lobe in the polar diagrams, indicative of a predominantly axial emission with an approximately Gaussian-like angular distribution.

In these fiber types, increasing the numerical aperture (NA) from 0.22 to 0.48 resulted in a progressive enlargement of the divergence angle, leading to a broader irradiated spot and consequently a reduction in power density.

Variations in core diameter (from 272 µm to 600 µm) mainly affected the initial spot size, while the overall lobe shape remained essentially unchanged.

Conical tip (Fiber ID: N°6 and N°7):

The conical tip fibers with radial emission exhibited two opposite lateral lobes with a minimal axial component. This behavior is consistent with the conical geometry, which refracts the guided radiation toward lateral directions.

Curved ball tip (Fiber ID: N°8):

The curved ball tip fiber features a spherical distal termination with a curvature toward one side.

The corresponding polar diagram shows, Table III, a right-shifted emission, resulting from beam deviation induced by the curvature of the spherical tip. The emitted radiation is diffuse but not isotropic, exhibiting a pronounced directional component. Such a characteristic may be advantageous in applications requiring selective illumination of specific regions within the optical field.

2.2. Thermocouples for Temperature Measurements

Temperature was measured using a type-K thermocouple placed inside a 14G, 18G or 21G needle positioned:

2.3. Laser System

All tests were performed using the Echolaser (Elesta S.p.A.), a 1064 nm diode laser system. The system integrates a laser source, a guiding ultrasound interface, and a dedicated control software (Echolaser Smart Interface, ESI), allowing precise planning, real-time monitoring, and verification of treatment parameters 88. Operating parameters for this study included: output powers of 3 W, 5 W, and 7 W, with delivered energies ranging from 1200 to 3600 J.

2.4. Angular Optical Power Distribution Measurement System (Goniophotometer)

Angular emission profiles were measured using a goniophotometer system composed of:

The acquisition of the polar emission diagrams for each fiber was performed by first recording the initial reference position of the motorized stage supporting the photosensitive detector connected to the goniophotometer’s control software. The procedure began with a measurement of the background noise level in a dark room. Subsequently, for each fiber, an optical power of 1 W was delivered for the time required to sample the 400 angular points predefined in the software, with an angular spacing of 0.5° between consecutive measurements.

3. Methods

3.1. Optical Fiber Emission Theory – Numerical Aperture (NA)

The emission characteristics of an optical fiber are mainly determined by its core diameter, numerical aperture (NA) and by the geometry of the distal tip. The numerical aperture defines the maximum acceptance (and emission) angle of the fiber and is expressed as:

where

and

are the refractive indices of the core and cladding, respectively, and

is the refractive index of the external medium.

The NA therefore determines the divergence of the output beam: fibers with higher NA produce a larger emission cone, whereas fibers with lower NA generate a more collimated beam.

3.2. Laser Ablation Phenomenon, Radiation-Matter Interaction and Thermal Effects

Laser-tissue interaction produces localized heating, leading to coagulative necrosis, which starts around 60 °C and progresses with exposure time [

9]. The resulting ablation volume in the case of a flat tip fiber is initially ellipsoidal and diverges radially until reaching a saturation plateau. Energy delivery, number of fibers, and spacing determine the final ablation size. The primary laser source is a diode emitting at λ = 1064 nm, with a circular beam profile, maximum output of 7 W per fiber, numerical aperture NA = 0.22, and continuous-wave emission. This wavelength provides optimal penetration in soft tissues while maintaining sharp ablation boundaries, due to a lower absorption coefficient compared to alternative wavelengths (e.g., 532 nm, 980 nm, 1480 nm). A visible red diode (635–670 nm) is also included for aiming purposes.

3.3. Sample Selection, Fiber and Thermocouples Insertion Techniques

Two tissue models were used:

The values reported in

Table 2 show that the thermal and optical properties of the three tissues considered fall within the typical ranges reported in the literature for biological tissues; a set of references is reported in [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In particular, the density, specific heat, and thermal conductivity of the prostate, liver, and porcine muscle are similar, while the water content shows more marked differences: the prostate and liver present higher values than the porcine muscle, the latter being a lean and more fibrous muscle. This makes the liver and prostate more comparable, especially regarding the thermal and optical response to the laser.

Regarding the optical properties at 1064 nm, it is observed that the prostate and liver present comparable absorption and scattering values, while the porcine muscle stands out for significantly lower values, particularly in the diffusion coefficient. Overall, the analysis confirms that the liver, thanks to its greater similarity to the prostate in terms of water content, composition and optical-thermal properties, represents a more suitable model for studying laser ablation phenomena.

Optical fibers and thermocouples are inserted into the tissue using needles, whose dimensions are matched to the outer diameter of the fibers and of the thermocouples. Specifically, 21G, 18G, and 14G needles were used for the fibers, while 21G and 14G needles were employed for the thermocouples. The distance between fiber and thermocouples was set at 10 mm, based on preliminary experiments that indicated this distance as appropriate for positioning the sensors at the periphery of the expected maximum ablation zone.

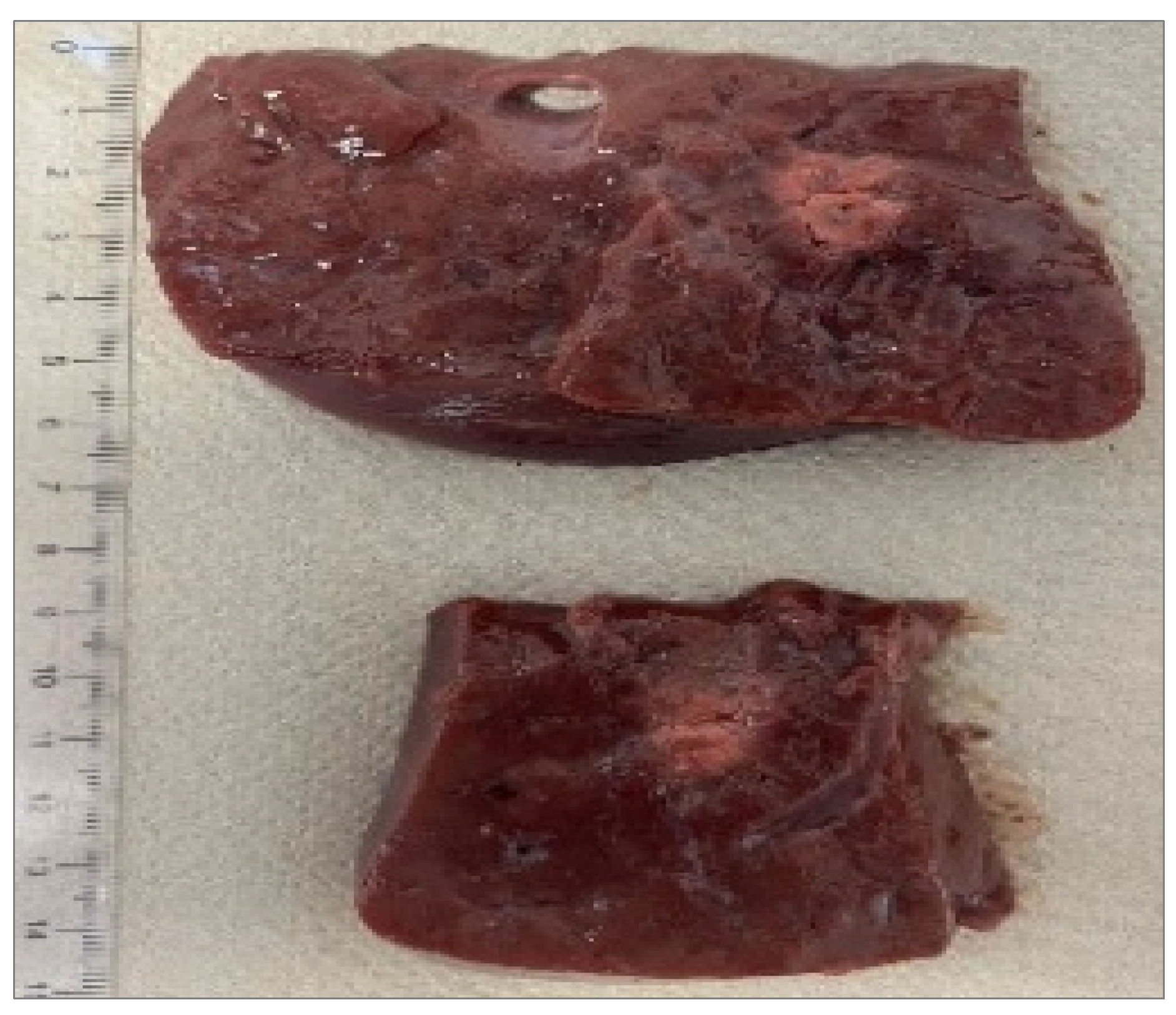

3.4. Recognition of Ablation Size

After sectioning the ablated tissue with a scalpel, an image of the sample is acquired with a ruler placed alongside it to record the scale for dimensional quantification,

Figure 1. The acquired image is then processed on a computer, where an ellipsoid is overlaid onto the ablated region. Using the adjacent ruler, the dimensions L and W (representing the longitudinal and transverse axes of the ellipsoid) are subsequently measured.

3.5. Tissues Irradiation Techniques

In our study, the following experimental configurations were examined:

Single fiber;

Dual fiber with 10 mm spacing;

Pull-back technique (fiber retraction after initial energy delivery);

Balloon catheter with scattering medium (hydroxyapatite suspension) in selected trials.

Depending on the treatment protocol, up to four fibers can be used simultaneously to achieve controlled ablation volumes, with real-time ultrasound guidance and ESI software enabling visualization of needle trajectories, fiber and thermocouples placement, and ablation zones before and during irradiation. The system supports different treatment strategies, including:

Single-fiber and multi-fiber configurations, to adapt ablation volume and shape to tissue geometry;

Pull-back technique, in which fibers are retracted after initial energy delivery to extend the ablation region longitudinally;

The laser powers applied via the optical fibers were set at 3 W, 5 W, and 7 W, corresponding to delivered energy doses ranging from 1200 J to 3600 J, with 1800 J being the most commonly used value. The irradiation time and consequently the duration of each experiment varied depending on the chosen power and energy dose. For a dose of 1800 J, the test duration was 10 minutes at 3 W, 6 minutes at 5 W, and 4 minutes and 17 seconds at 7 W. These parameters were selected to deliver controlled energy to the tissue while ensuring reproducible ablation volumes, and their effects are further analyzed in the Results section.

3.6. Outcome Parameters

Primary outcome measures:

4. Results

4.1. Radiation Profiles of the Eight Types of Optical Fibers Analyzed

Table III reports the radiation profile of the eight optical fibers used used in the experimental phase, as described in the previous sections.

Table 3.

Radiation profiles of the eight types of optical fibers analyzed.

Table 3.

Radiation profiles of the eight types of optical fibers analyzed.

| Type of optical fiber |

Radiation profiles |

|

4.2. Optical Fibers with Flat Tip Geometry

Ablation volumes increased with both core diameter and numerical aperture (NA).

An increase in the core diameter determines an increase in both the longitudinal dimension L and the transverse dimension W, with a more marked impact on the dimension L. Regarding the numerical aperture, it is clear that a higher aperture leads to a greater divergence of the output beam, translating into a prevalent increase in the transverse dimension W.

Core = 272 µm (Fiber N°1) –300 µm (Fiber N°2), NA = 0.22. Produced the smallest lesions, with longitudinal dimensions (L) typically exceeding transverse width (W), yielding an elongated, ellipsoidal profile.

Core = 300 µm (Fiber N°3) – 400 µm (Fiber N°4), NA = 0.37. Resulted in a marked increase in W and a more spherical ablation shape. The transition from NA 0.22 to 0.37 produced the largest relative increase in W among all pairwise comparisons.

Core = 600 µm (Fiber N°5), NA = 0.48. Generated the largest ablations overall. At 7 W, these fibers produced broad coagulation zones but also showed the highest degree of thermal spread, consistent with the combination of high NA and large mode volume.

The ablation dimensions obtained during the tests for the five flat-tip fibers are reported in

Table 4. The L and W values, together with the temperature increase ΔT between the initial and final temperatures, are reported as mean ± standard deviation based on the number of samples tested for each experiment, as the initial temperature of the calf liver varies among tests.

The test end time is determined by the selected power and the delivered dose; for example: Δt (3 W @ 1800 J) = 10 min, Δt (5 W @ 1800 J) = 6 min, and Δt (7 W @ 1800 J) = 4 min 17 s. The effective test duration is longer than the theoretical one due to an initial baseline temperature recording phase.

Across all flat-tip fibers, ablation size scaled with delivered power (3 W→ 5 W → 7 W).

At higher energies (>1800 J), a saturation effect was noted: increases in L and W became progressively smaller, indicating heat diffusion–limited ablation growth.

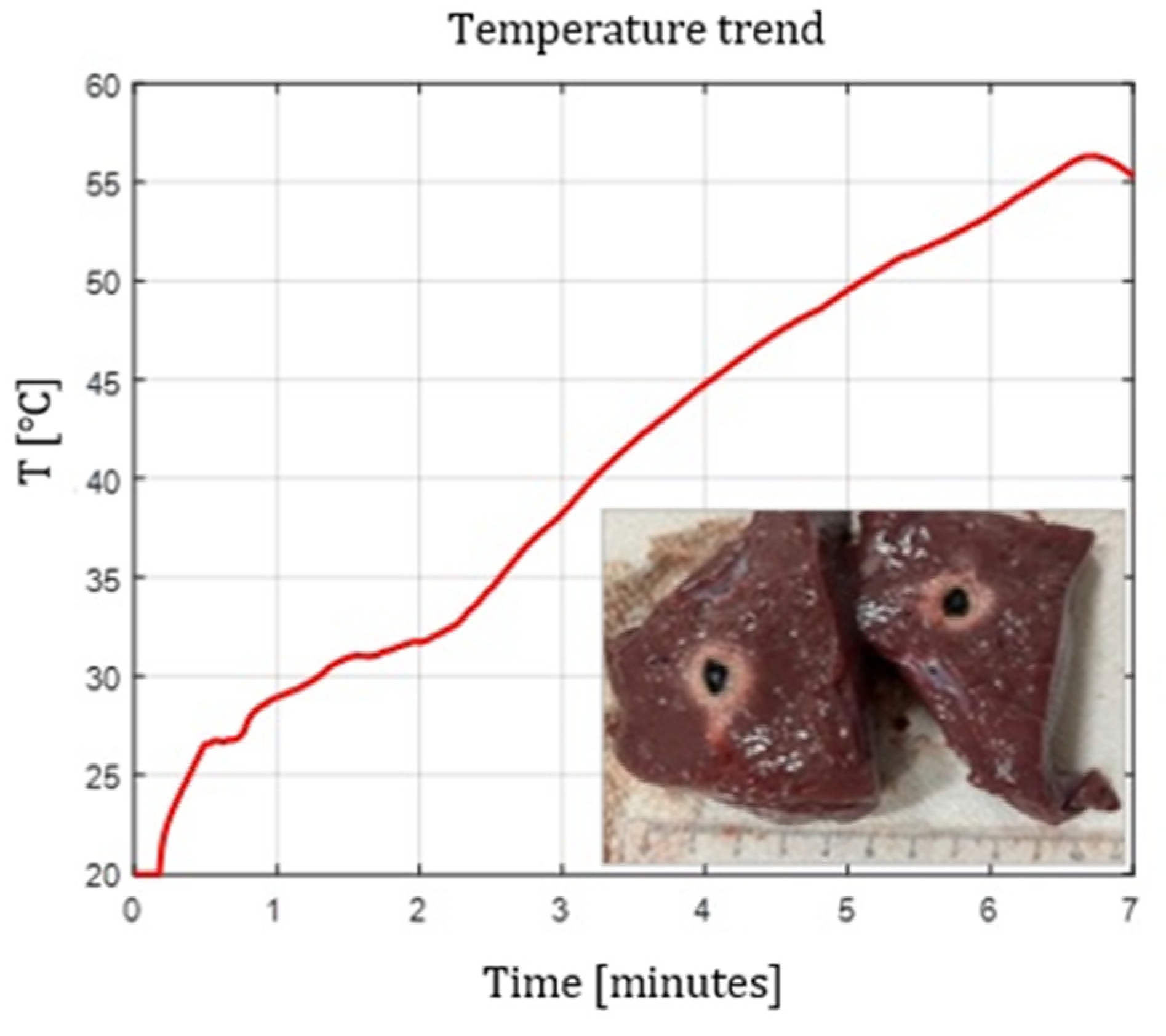

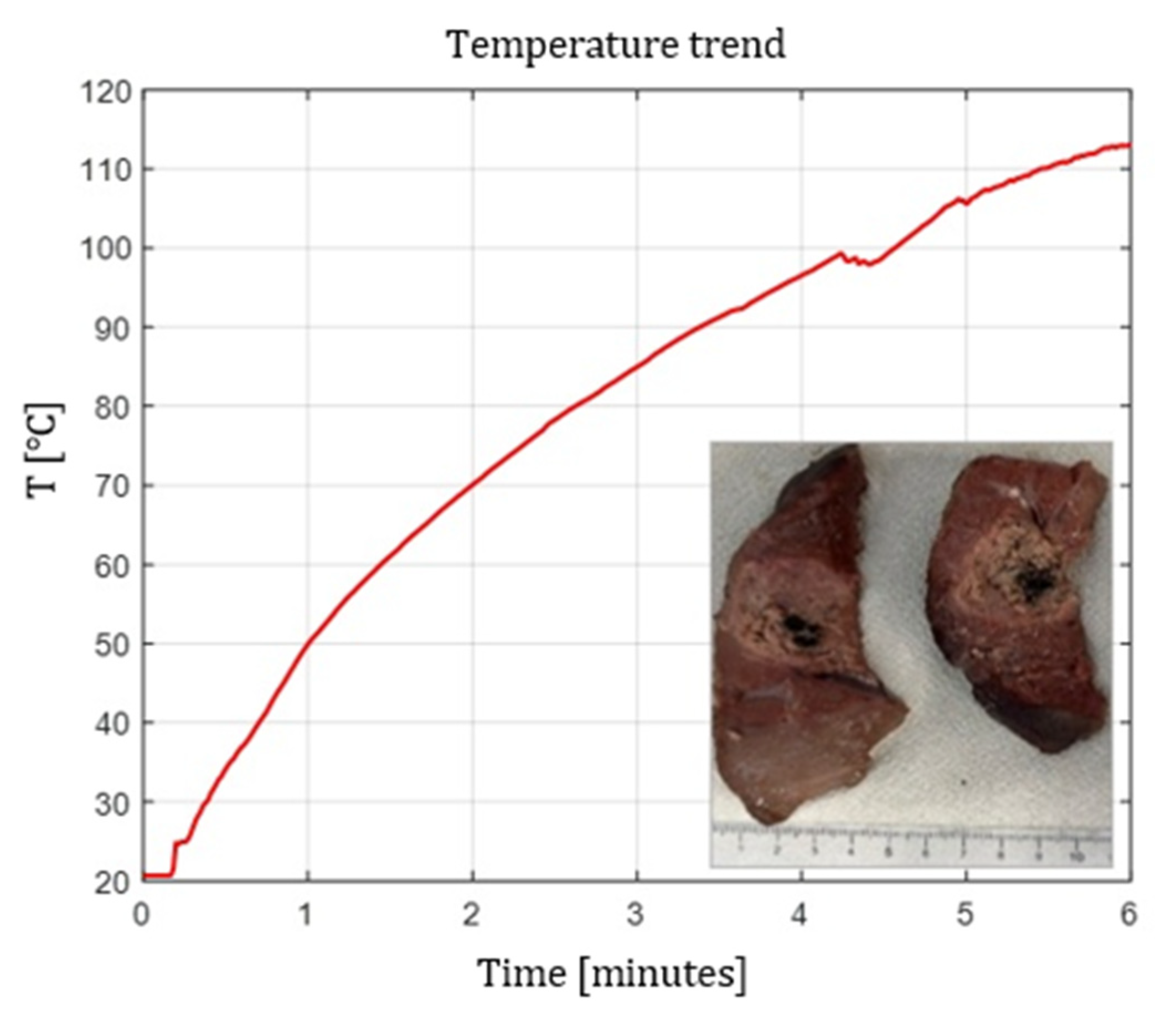

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the effects of laser ablation on calf liver and the temperature profiles recorded as a function of the test duration, using Fiber N°1. The resulting ablation dimensions were: L= [18.0

0.9] mm and W= [12.2

1.0] mm (3W@1800J, 6 samples tested), L= [19.3

1.0] mm and W= [12.5

0.6] mm (5W@1800J, 4 samples tested), L= [23.0

1.2] mm and W= [14.8

1.0] mm (7W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

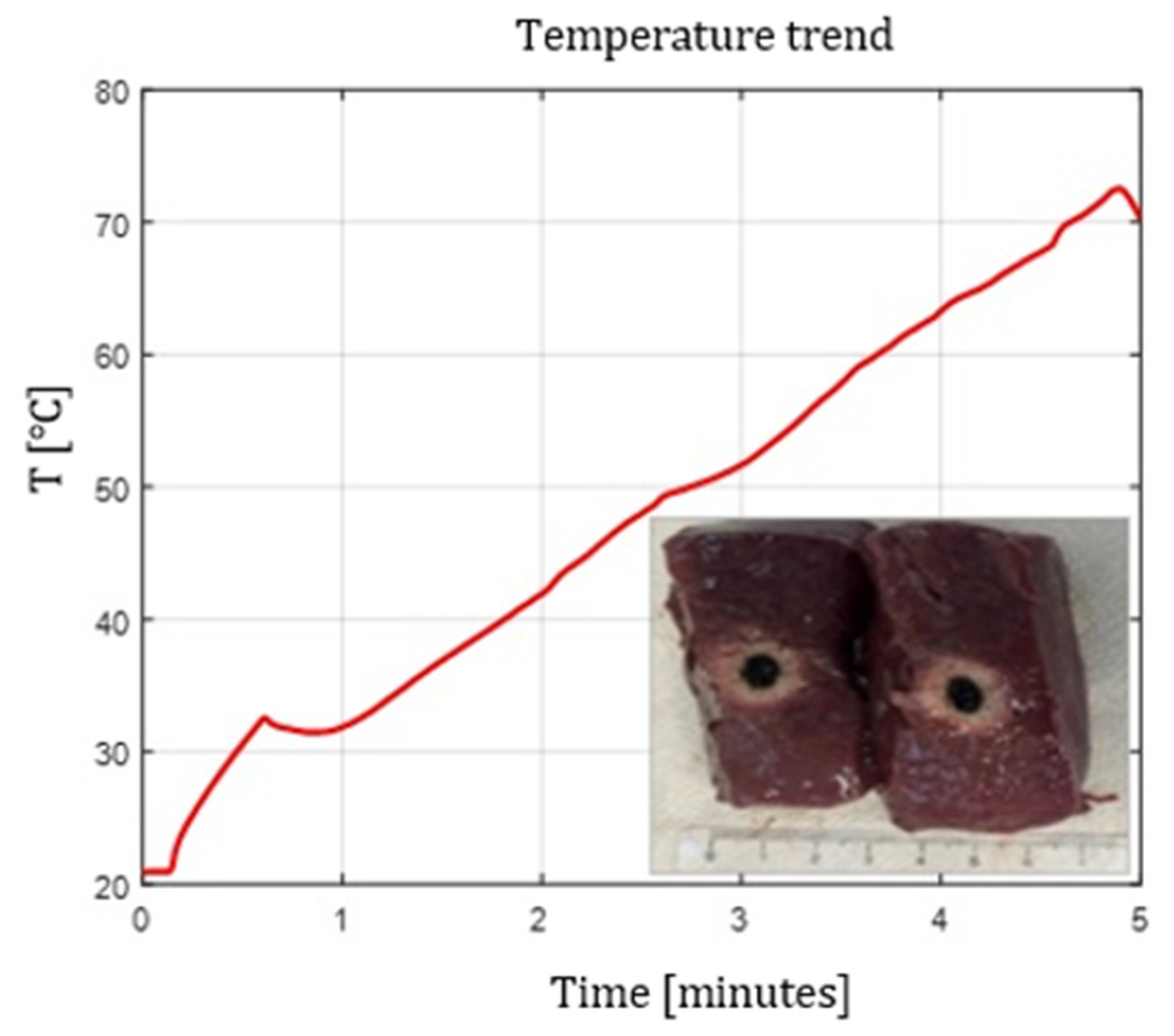

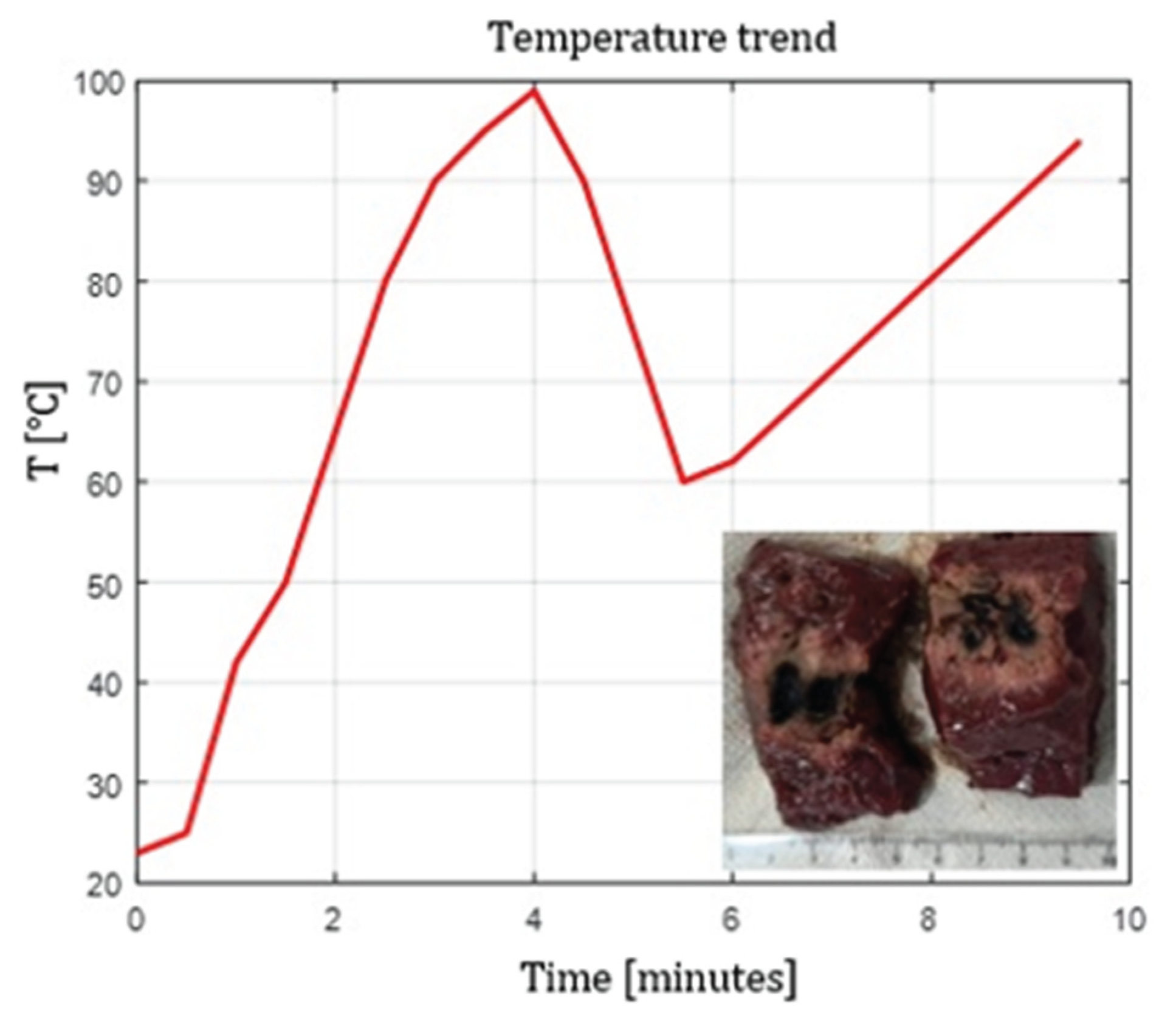

As an example,

Figure 5 shows the ablation effects and the recorded temperature profile for Fiber N° 5 at 7 W@1800 J, which resulted in larger ablation dimensions compared to the other tests, in agreement with Table IV.

4.3. Radial Emission Conical Fibers

Fibers with conical diffusing tips (Fibers N°6–N°7, in Table I) produced radially symmetric thermal profiles, with significantly lower longitudinal extension compared to flat tip fibers.

Ablation shapes were more spherical and homogeneous.

L decreased relative to flat tip fibers, confirming the lateral redistribution of energy.

The 400 µm radial fiber (Fiber N°7) produced slightly larger lesions than the 365 µm version (Fiber N°6), though differences were less pronounced than in flat tip fibers, consistent with the dominating role of the diffuser. For these types of optical fibers, the temperature profile at 10 mm distance from the tip was not analyzed, since the light radiation is not emitted in the axial direction, but laterally, according to two radiation lobes. As can be seen in

Figure 6, the ablation dimensions obtained, for example, in the 3 W @ 1800 J test with Fiber N°6, were L = 13.0 mm and W = 13.0 mm, for a single sample tested.

4.4. Spherical Curved Ball Tip Fiber

The curved ball-tip fiber (Fiber N°8) generated highly isotropic emission, producing ablations with the most uniform W/L ratio among all fibers. The results showed that, even with relatively low doses compared to the other tests (below 1800 J), setting the power to 5 W produces significantly larger ablation areas than those obtained with flat tip fibers. As can be seen in

Figure 7, the ablation dimensions obtained, for example, in the 5 W @ 1800 J test with Fiber N°8, were L = 27.0 mm and W = 20.0 mm, for a single sample tested.

4.5. Temperature Profiles

Temperature measurements at 10 mm showed consistent trends:

Flat tip fibers with higher NA and higher core diameter reached peak temperatures faster.

Radial and ball-tip fibers exhibited lower initial temperature slopes, indicating slower local heating due to redistributed emission.

Across all fibers, increasing laser power produced proportionally higher peak temperatures, though saturation effects were observed at 7 W.

4.6. Multi-Fiber and Pull-Back Configurations

Using two fibers at 10 mm spacing resulted in:

substantial enlargement of the transverse ablation zone;

partial merging of the two thermal fields;

higher measured temperatures at the midpoint compared to single-fiber trials.

The pull-back technique produced elongated lesions with cumulative lengths approximately equal to the sum of the two irradiation steps, providing a controllable method for extending ablation along the longitudinal axis.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the effects of laser ablation on calf liver and the temperature profiles recorded as a function of the test duration, using single and double Fiber N°1 with/without pull-back. The resulting ablation dimensions were: L= [27.0

1.4] mm and W= 15 mm (3W@1800J, 2 samples tested, single Fiber N°1 with pull-back), L= 20 mm and W= 25.5 mm (5W@1800J, 1 sample tested, double Fiber N°1), L= 31 mm and W= 29 mm (7W@1800J, 1 sample tested, double Fiber N°1 with pull-back).

4.7. Balloon Catheter with Scattering Medium

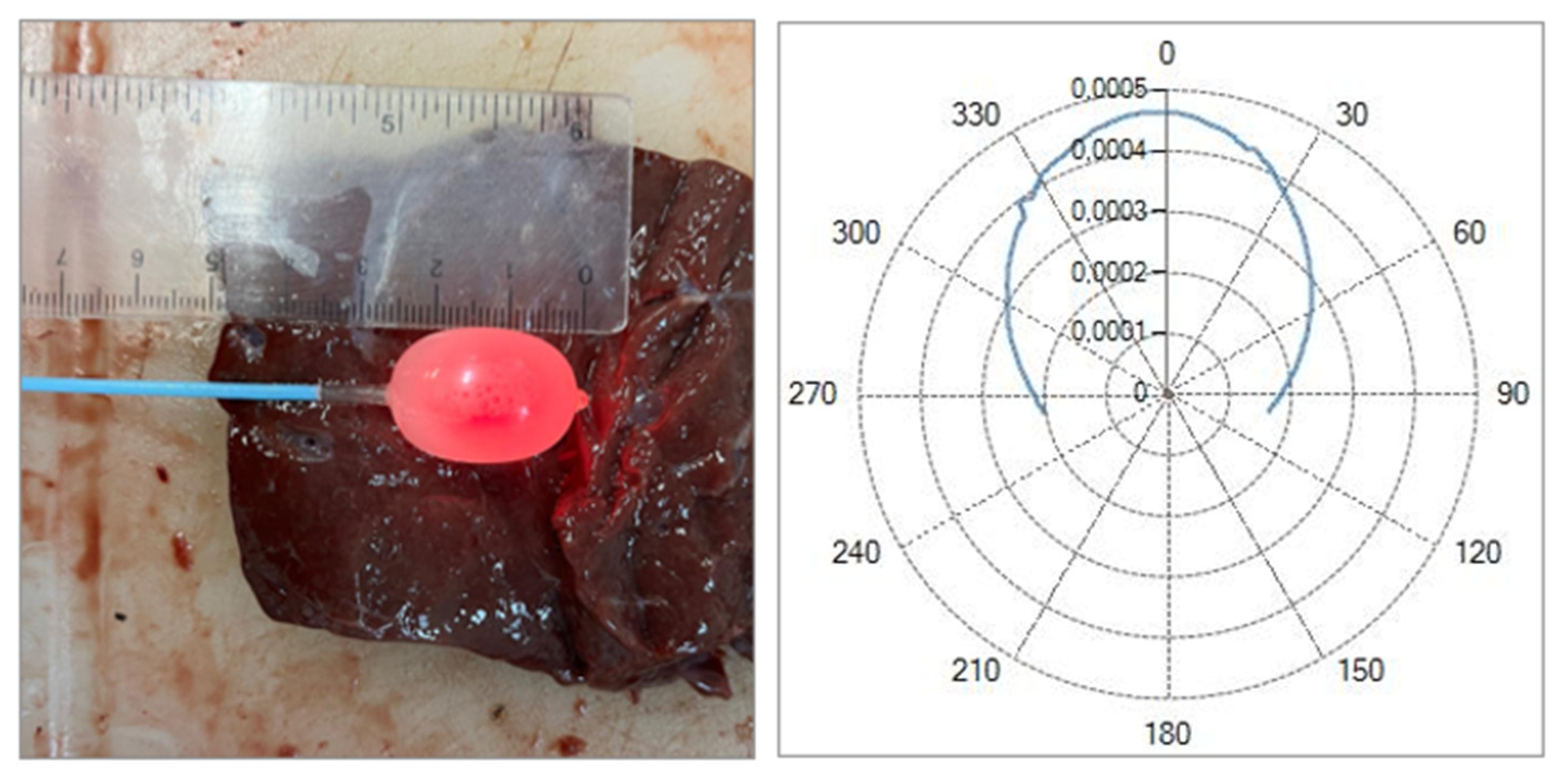

Preliminary tests with a balloon catheter filled with a hydroxyapatite suspension demonstrated the feasibility of generating more circular and homogeneous ablations. A photo of the catheter with the inflated balloon, alongside the calibration ruler, is shown in

Figure 11. In this case, a red light was injected into the optical fiber to highlight the diffusive properties of the solution. Was observed that increasing hydroxyapatite concentration improved uniformity but reduced overall transmitted power. The 0.2

–0.5 g/16 mL mixture produced the best balance between uniformity and ablation extent.

These results suggest a viable approach for distributed, circumferential ablation in confined anatomical spaces.

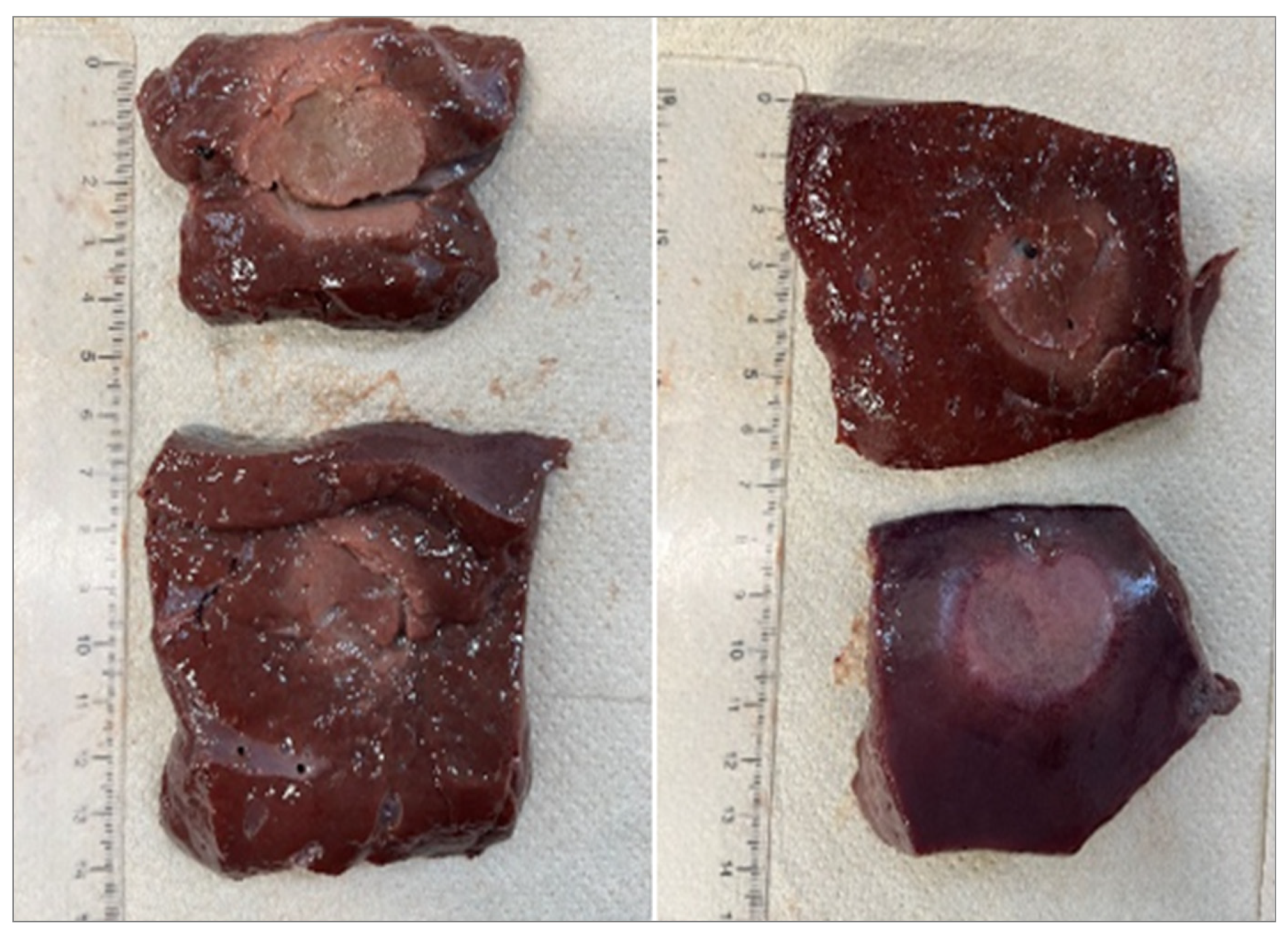

As can be seen in

Figure 12, the ablation dimensions obtained, in the 7 W @ 5400 J test with Fiber N°1, were L = [30.0 ± 1.4] mm and W = [25.5 ± 0.7] mm, for 2 sample tested.

5. Discussion

This study provides a comparative analysis of eight multimode optical fibers for laser ablation with the 1064 nm Echolaser system, highlighting how fiber geometry and optical properties directly influence thermal distribution and lesion morphology.

5.1. Influence of Core Diameter and Numerical Aperture

Flat tip fibers demonstrated that ablation size grows with both core diameter and NA, consistent with the broader emission cone and higher fluence delivered to the tissue.The transition from NA 0.22 to 0.37 produced the largest relative gain in ablation width, confirming NA as a dominant parameter in determining lateral heat diffusion. These findings align with established models of interstitial laser therapy, where higher NA increases beam divergence and enlarges the radius of effective heating.

5.2. Radial and Spherical Emission for Uniform Ablation

Radial diffusers and the curved ball tip fiber shifted the energy pattern from axial to isotropic emission, reducing longitudinal lesion elongation and producing more spherical coagulation volumes.

Radial fibers showed improved symmetry, supporting their potential use in anatomical regions where circumferential ablation is desired;

The ball-tip fiber produced the most extensive ablation dimensions compared to all other fiber types.

5.3. Multi-Fiber and Pull-Back Strategies

The dual fiber configuration highlighted how thermal fields can be combined to increase ablation width, mirroring clinical protocols used for prostate debulking. The pull-back method enabled longitudinal extension while preserving control over local thermal deposition.

5.4. Temperature Evolution and Thermal Spread

Temperature measurements reflected the expected behaviour of interstitial heating:

Large-core, high-NA fibers produced faster temperature rise and higher steady-state values.

Radial and spherical fibers heated more gradually, consistent with their diffused emission patterns.

Saturation effects in lesion growth and temperature at higher powers (7 W) suggest a regime where heat diffusion limits additional thermal spread.

5.5. Balloon Catheter Feasibility

The balloon catheter study provides preliminary evidence that combining a scattering medium with a flat tip fiber can enable controlled, symmetric ablations in constrained environments. Although transmitted power decreases with concentration, the improved uniformity may benefit applications requiring circumferential or cylindrical ablations. This concept could be relevant for endocavitary laser procedures or minimally invasive treatments where preserving tissue symmetry is essential.

5.6. Limitations

Experiments were performed ex-vivo, without perfusion, likely overestimating thermal lesion size compared to in-vivo conditions. Tissue variability and dehydration may introduce minor inconsistencies among samples.

6. Conclusion

This study provides a systematic experimental assessment of eight optical fibers with different core diameters, numerical apertures, and tip geometries for soft tissue ablation using the 1064 nm Echolaser system. Fiber characteristics were shown to strongly influence ablation dimensions, temperature evolution, and lesion uniformity. Flat tip fibers with large core diameters and high NA produced the greatest ablation volumes, while radial and spherical diffusers generated more isotropic and homogeneous lesions.

Multi-fiber and pull-back techniques enabled controlled enlargement of the coagulation zone, and preliminary balloon catheter tests demonstrated a promising approach for uniform circumferential ablations. These findings provide a quantitative reference framework for selecting and designing optical fibers tailored to specific minimally invasive urological applications, while supporting future optimization of laser-based therapeutic devices.

Future research should focus on integrating real-time temperature mapping or thermographic imaging to enhance intraoperative monitoring, optimizing balloon catheter designs for in vivo applications, and evaluating fiber durability under repeated clinical use. Such developments could further improve the safety and reproducibility of fiber-based laser ablation therapies.

References

- Gibson KF, Kernohan WG. Lasers in medicine—A review. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology. 1993;17(5):197–203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8366508/. [CrossRef]

- Walser EM, Zimmerer R, Nance A, Masood I, Saleem A. Anatomic and Clinical Effects of Focal Laser Ablation of the Prostate on Symptomatic Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Cancers. 2025;17(3):475. [CrossRef]

- Tafuri A, Panunzio A, De Carlo F, Luperto E, Di Cosmo F, Cavaliere A, et al. Transperineal Laser Ablation for Benign Prostatic Enlargement: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of Pilot Studies. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5):1860. [CrossRef]

- Fainberg JS, Al Hussein Al Awamlh B, DeRosa AP, Chesnut GT, Coleman JA, Lee T, et al. A Systematic Review of Outcomes after Thermal and Nonthermal Partial Prostate Ablation. Prostate Int. 2021;9(4):169–175. [CrossRef]

- Brace CL. Microwave tissue ablation: biophysics, technology, and applications. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1. [CrossRef]

- Yang C-H, Barbulescu D-V, Marian L, Tung M-C, Ou Y-C, Wu C-H. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Ablation in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. J Pers Med. 2024;14(12):1163. [CrossRef]

- Chin YF, Lynn N. Systematic Review of Focal and Salvage Cryotherapy for Prostate Cancer. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e26400. [CrossRef]

- Elesta S.p.A. (n.d.). EchoLaser: First, Unique, Micro-invasive, Integrated System Offering Diagnostic Ultrasound and Laser Ablation Treatments. https://www.elesta-echolaser.com.

- Papadopoulou-Schultheiss A, Schulze-Osthoff K, Schultheiss G. Thermal cell injury: the significance of temperature and exposure time. Radiother Oncol. 1990;19(2):129–145. PMID:2343609.

- McIntosh R, Anderson V. A Comprehensive Tissue Properties Database Provided for the Thermal Assessment of a Human at Rest. Biophys Rev Lett. 2010;5(3):129−151. [CrossRef]

- Giering K, Lamprecht I, Minet O, Handke A. Determination of the Specific Heat Capacity of Healthy and Tumorous Human Tissue. Thermochim Acta. 1995;251:199–205. [CrossRef]

- Data on thermal conductivity of tissues including statistical information on the standard deviation and the spread in the values: https://itis.swiss/virtual-population/tissue-properties/database/thermal-conductivity/.

- Data on density of tissues including statistical information on the standard deviation and the spread in the values: https://itis.swiss/virtual-population/tissue-properties/database/density/.

- Data on heat capacity of tissues including statistical information on the standard deviation and the spread in the values: https://itis.swiss/virtual-population/tissue-properties/database/heat-capacity/.

- Germer CT, Roggan A, Ritz JP, Isbert C, Albrecht D, Müller G, Buhr HJ. Optical Properties of Native and Coagulated Human Liver Tissue and Liver Metastases in the Near Infrared Range. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;23(4):194–203. PMID: 9829430. [CrossRef]

- Adamczak L, Chmiel M, Florowski T, Pietrzak D. Estimation of Chemical Composition of Pork Trimmings by Use of Density Measurement-Hydrostatic Method. Molecules. 2020;25(7):1736. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang X. Effects of Different Cooking Methods on the Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Quality of Pork Muscle. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6(5):1185–1193. [CrossRef]

- Engineering Toolbox. Specific Heat Capacity of Foods. https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/specific-heat-capacity-food-d_295.html.

- Leitman, S. (1967). Experimental determination of thermal conductivity of various types of meat, including pork. Georgia Institute of Technology. https://repository.gatech.edu/bitstreams/304e0095-b44b-4265-8289-0ad293dd3a70/download.

- Saccomandi, P., Vogel, V., Bazrafshan, B., Maurer, J., Schena, E., Vogl, T. J., Silvestri, S., & Mäntele, W. (2015). Estimation of anisotropy coefficient of swine pancreas, liver and muscle at 1064 nm based on goniometric technique. Journal of Biophotonics, 8(5), 422–428. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jbio.201400057.

- Thomas, S. (2016). Property Tables and Charts (SI Units), Appendix 1. Wright State University, College of Engineering and Computer Science. https://cecs.wright.edu/people/faculty/sthomas/htappendix01.pdf.

- Bergmann, F., Foschum, F., Marzel, L., & Kienle, A. (2021). Ex Vivo Determination of Broadband Absorption and Effective Scattering Coefficients of Porcine Tissue. Photonics, 8(9), 365. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, S., Lanka, P., Stone, N., Konugolu Venkata Sekar, S., Matousek, P., Valentini, G., & Pifferi, A. (2020). Optical Characterization of Porcine Tissues from Various Organs in the 650–1100 nm Range Using Time-Domain Diffuse Spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express, 11(3), 1697–1706. (PubMed Central: PMC7075607). [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Single Fiber N°1 (5W@1800J). L= [19.3 ± 1.0] mm and W= [12.5 ± 0.6] mm (5W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

Figure 1.

Single Fiber N°1 (5W@1800J). L= [19.3 ± 1.0] mm and W= [12.5 ± 0.6] mm (5W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

Figure 2.

Single Fiber N°1. L= [18.0 0.9] mm and W= [12.2 1.0] mm (3W@1800J, 6 samples tested).

Figure 2.

Single Fiber N°1. L= [18.0 0.9] mm and W= [12.2 1.0] mm (3W@1800J, 6 samples tested).

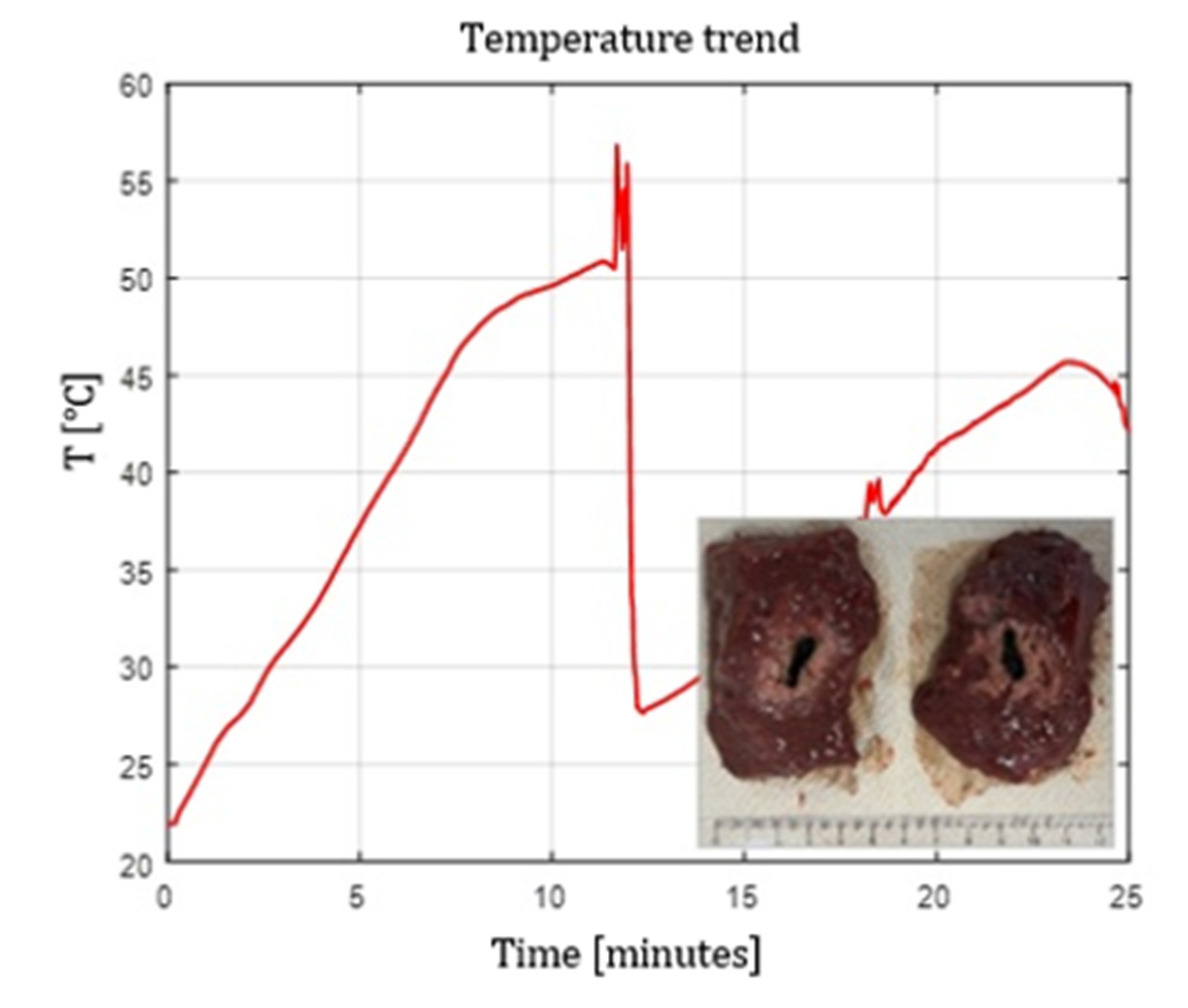

Figure 3.

Single Fiber N°1. L= [19.3 1.0] mm and W= [12.5 0.6] mm (5W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

Figure 3.

Single Fiber N°1. L= [19.3 1.0] mm and W= [12.5 0.6] mm (5W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

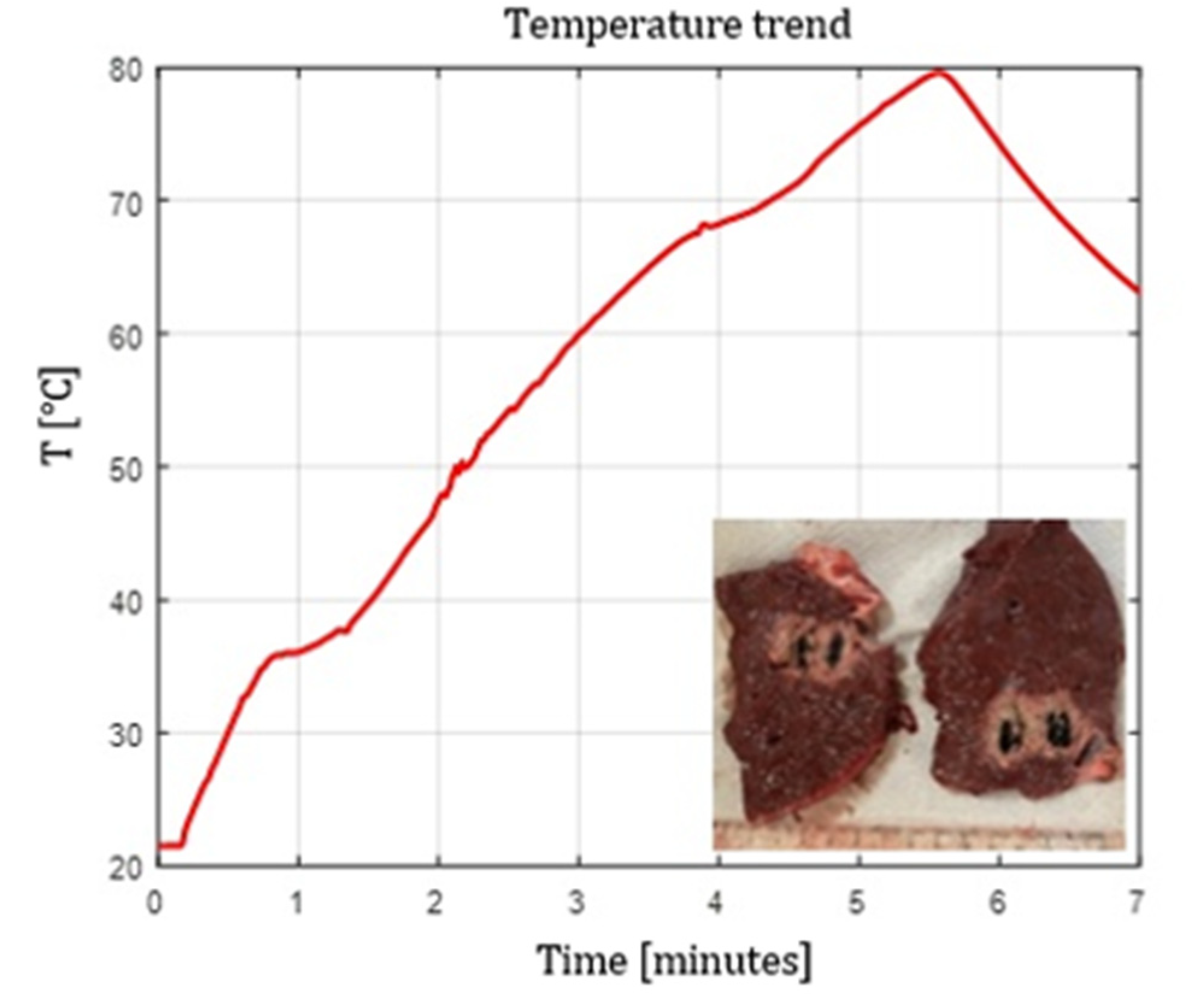

Figure 4.

Single Fiber N°1. L= [23.0 1.2] mm and W= [14.8 1.0] mm (7W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

Figure 4.

Single Fiber N°1. L= [23.0 1.2] mm and W= [14.8 1.0] mm (7W@1800J, 4 samples tested).

Figure 5.

Fiber N°5 (7W@1800J, 2 samples tested). Ablation dimensions: L= [24.5 0.7] mm and W= [16.0 1.4] mm.

Figure 5.

Fiber N°5 (7W@1800J, 2 samples tested). Ablation dimensions: L= [24.5 0.7] mm and W= [16.0 1.4] mm.

Figure 6.

Fiber N°6 (3W@1800J, 1 sample tested). L=13 mm and W=13 mm.

Figure 6.

Fiber N°6 (3W@1800J, 1 sample tested). L=13 mm and W=13 mm.

Figure 7.

Fiber N°8 (5W@1800J, 1 sample tested). L=27 mm and W=20 mm.

Figure 7.

Fiber N°8 (5W@1800J, 1 sample tested). L=27 mm and W=20 mm.

Figure 8.

Single Fiber N°1 with pull-back. L= [27.0 1.4] mm and W= 15 mm (3W@1800J, 2 samples tested).

Figure 8.

Single Fiber N°1 with pull-back. L= [27.0 1.4] mm and W= 15 mm (3W@1800J, 2 samples tested).

Figure 9.

Double Fiber N°1 without pull-back. L= 20 mm and W= 25.5 mm (5W@1800J, 1 sample tested).

Figure 9.

Double Fiber N°1 without pull-back. L= 20 mm and W= 25.5 mm (5W@1800J, 1 sample tested).

Figure 10.

Experimental test-calf liver: double Fiber N°1 with pull-back. Ablation dimensions: L= 31 mm and W= 29 mm (7W@1800J, 1 sample tested).

Figure 10.

Experimental test-calf liver: double Fiber N°1 with pull-back. Ablation dimensions: L= 31 mm and W= 29 mm (7W@1800J, 1 sample tested).

Figure 11.

Balloon geometry of the catheter inflated with a solution containing 0.5 g of hydroxyapatite dispersed in 16 mL of saline solution at an internal pressure of 4 atm, and corresponding radiation emission profile measured under the same conditions.

Figure 11.

Balloon geometry of the catheter inflated with a solution containing 0.5 g of hydroxyapatite dispersed in 16 mL of saline solution at an internal pressure of 4 atm, and corresponding radiation emission profile measured under the same conditions.

Figure 12.

Balloon catheter test with Fiber N°1 at 7 W @ 5400 J. The balloon contains 0.2 g of hydroxyapatite dispersed in 16 mL of saline solution and is inflated to an internal pressure of 4 atm.

Figure 12.

Balloon catheter test with Fiber N°1 at 7 W @ 5400 J. The balloon contains 0.2 g of hydroxyapatite dispersed in 16 mL of saline solution and is inflated to an internal pressure of 4 atm.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tested optical fibers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tested optical fibers.

| Fiber ID |

Core [µm] |

OD [µm] |

NA |

Tip geometry |

Manufacturer |

| N°1 |

272 |

420 |

0.22 |

Flat tip |

Oberon-Elesta custom |

| N°2 |

300 |

350 |

0.22 |

Flat tip |

Asclepion |

| N°3 |

300 |

650 |

0.37 |

Flat tip |

Thorlabs |

| N°4 |

400 |

730 |

0.37 |

Flat tip |

Oberon |

| N°5 |

600 |

1040 |

0.48 |

Flat tip |

Thorlabs |

| N°6 |

365 |

800 |

0.22 |

Conical tip |

Oberon-Elesta custom |

| N°7 |

400 |

950 |

0.22 |

Conical tip |

Oberon |

| N°8 |

600 |

890 |

0.22 |

Curved ball tip |

Oberon |

Table 2.

Thermal and optical properties of tissues: prostate, calf liver and porcine muscle.

Table 2.

Thermal and optical properties of tissues: prostate, calf liver and porcine muscle.

| |

Thermal properties |

%

Water

|

Optical properties (=1064 nm)

|

| |

Tissue density [kg m-3] |

Specific heat[J kg-1 °C-1] |

Thermal conductivity [W m-1 °C-1] |

|

Absorption coefficient [cm-1] |

Diffusion coefficient [cm-1] |

| Prostate |

1045 |

3715 |

0.51 |

82 |

0.4 |

110 |

| Calf liver |

1079 |

3540 |

0.52 |

75 – 81.9 |

0.3 – 0.5 |

150 – 169 |

| Porcine muscle |

1082 - 1100 |

3490 |

0.44 – 0.49 |

73 - 75 |

0.12 – 0.22 |

2.5 – 5.0 |

Table 4.

Ablation dimensions (L, W) and ΔT in single flat tip fiber tests.

Table 4.

Ablation dimensions (L, W) and ΔT in single flat tip fiber tests.

| Fiber |

3W@1800J |

5W@1800J |

7W@1800J |

| N°1 |

L = [18.0 ± 0.9] mm

W = [12.2 ± 1.0] mm

ΔT = [30.9 ± 4.3] °C |

L = [19.3 ± 1.0] mm

W = [12.5 ± 0.6] mm

ΔT = [34.1 ± 3.2] °C |

L = [23.0 ± 1.2] mm

W = [14.8 ± 1.0] mm

ΔT = [48.0 ± 9.8] °C |

| N°2 |

L = [20.0 ± 0.0] mm

W = [13.0 ± 0.0] mm

ΔT = [40.1 ± 0.0] °C |

L = [22.0 ± 0.0] mm

W = [14.0 ± 0.0] mm

ΔT = [45.4 ± 0.0] °C |

L = [23.5 ± 0.7] mm

W = [14.0 ± 0.0] mm

ΔT = [66.4 ± 0.0] °C |

| N°3 |

L = [20.5 ± 0.7] mm

W = [15.5 ± 0.7] mm

ΔT = [34.2 ± 4.7] °C |

L = [22.5 ± 0.7] mm

W = [15.5 ± 0.7] mm

ΔT = [41.6 ± 0.0] °C |

L = [24.5 ± 0.7] mm

W = [17.0 ± 1.4] mm

ΔT = [56.6 ± 0.0] °C |

| N°4 |

L = [20.0 ± 0.0] mm

W = [13.5 ± 0.7] mm

ΔT = [38.3 ± 5.6] °C |

L = [23.0 ± 0.0] mm

W = [15.0 ± 0.0] mm

ΔT = [40.7 ± 4.5] °C |

L = [28.0 ± 0.0] mm

W = [17.0 ± 0.0] mm

ΔT = [54.7 ± 0.0] °C |

| N°5 |

L = [21.5 ± 0.7] mm

W = [15.5 ± 0.7] mm

ΔT = [45.3 ± 1.6] °C |

L = [23.0 ± 1.0] mm

W = [16.0 ± 1.0] mm

ΔT = [55.3 ± 0.0] °C |

L = [24.5 ± 0.7] mm

W = [16.0 ± 1.4] mm

ΔT = [64.2 ± 0.0] °C |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).