Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. Introduction

2.0. Materials and Methods

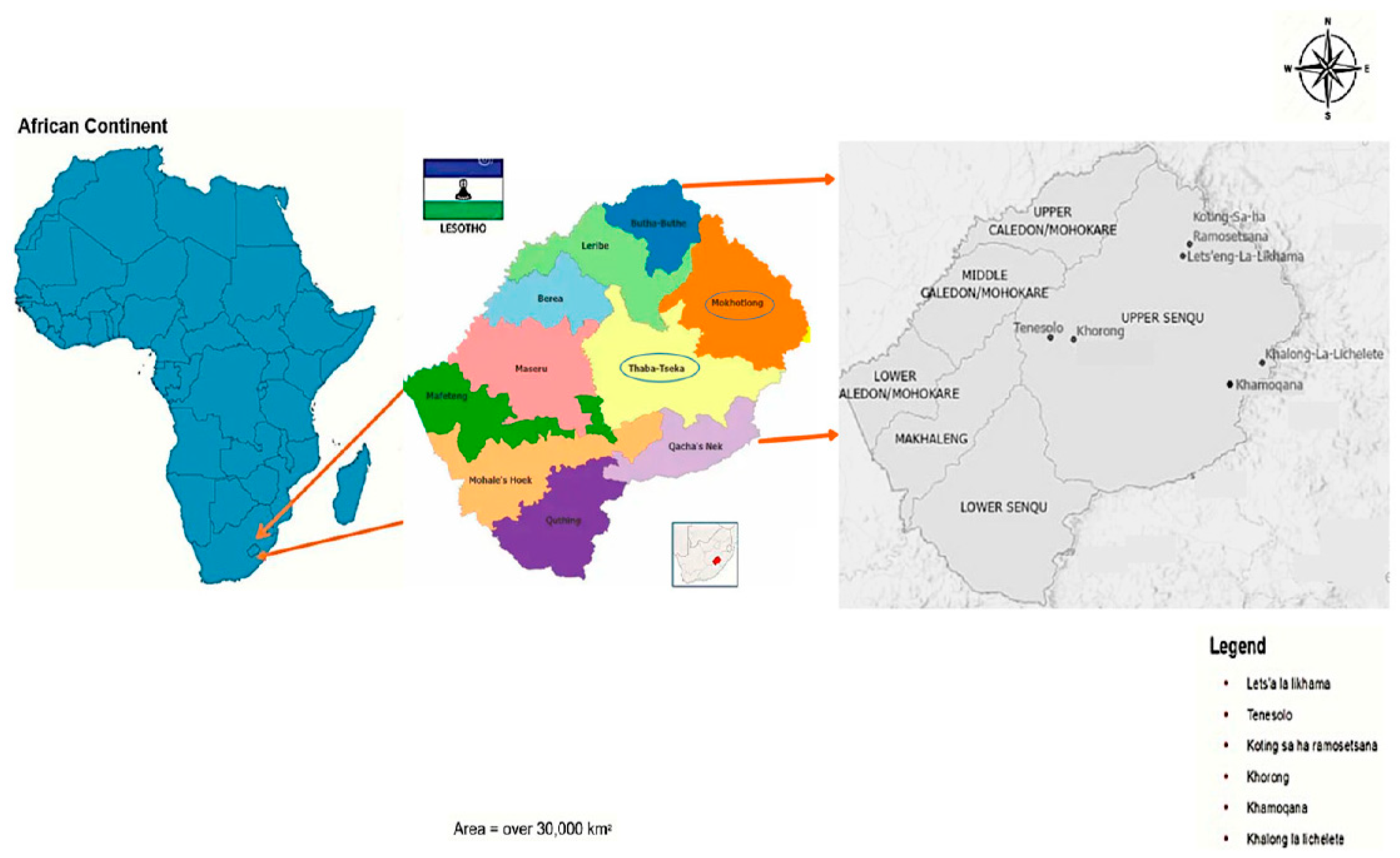

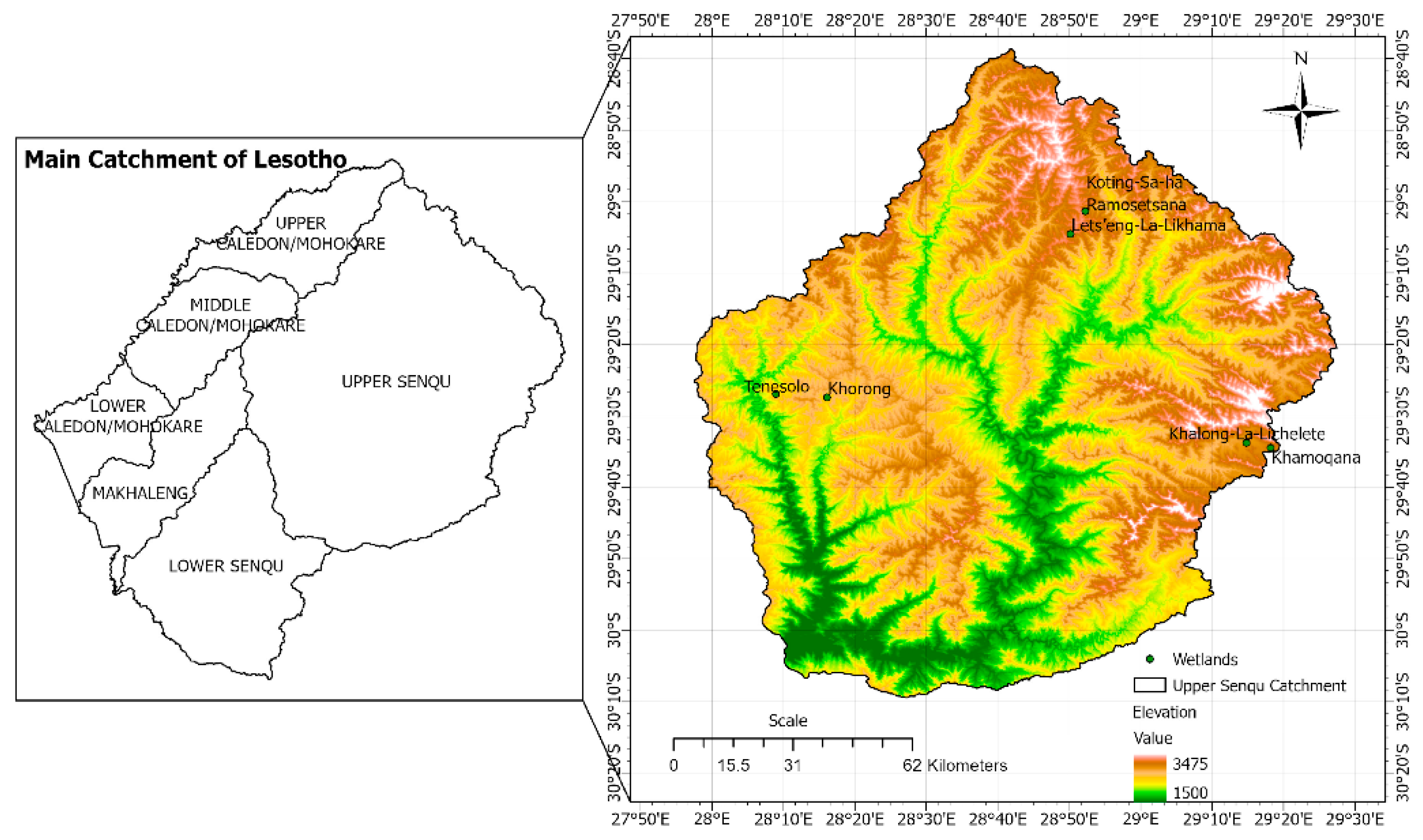

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Senqunyane Sub-Catchment

2.1.2. Khubelu Sub-Catchment

2.1.3. Sani Pass Sub-Catchment

2.1.4. Overall Significance

2.2. Data Sampling and Analysis

2.2.1. Pollution Load Index (PLI)

- CFi = Contamination Factor of the i-th metal

- Ci = Measured concentration of the metal

- Bi = Background or reference value of the metal

- n = Number of metals assessed

- П = Product of the contamination factor

2.2.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI)

- Mi = Measured concentration

- Ii = Ideal value (often 0 for heavy metals) concentration

- Si = Standard or persimible value (e.g. WHO limits)

3.0. Results and Discussion

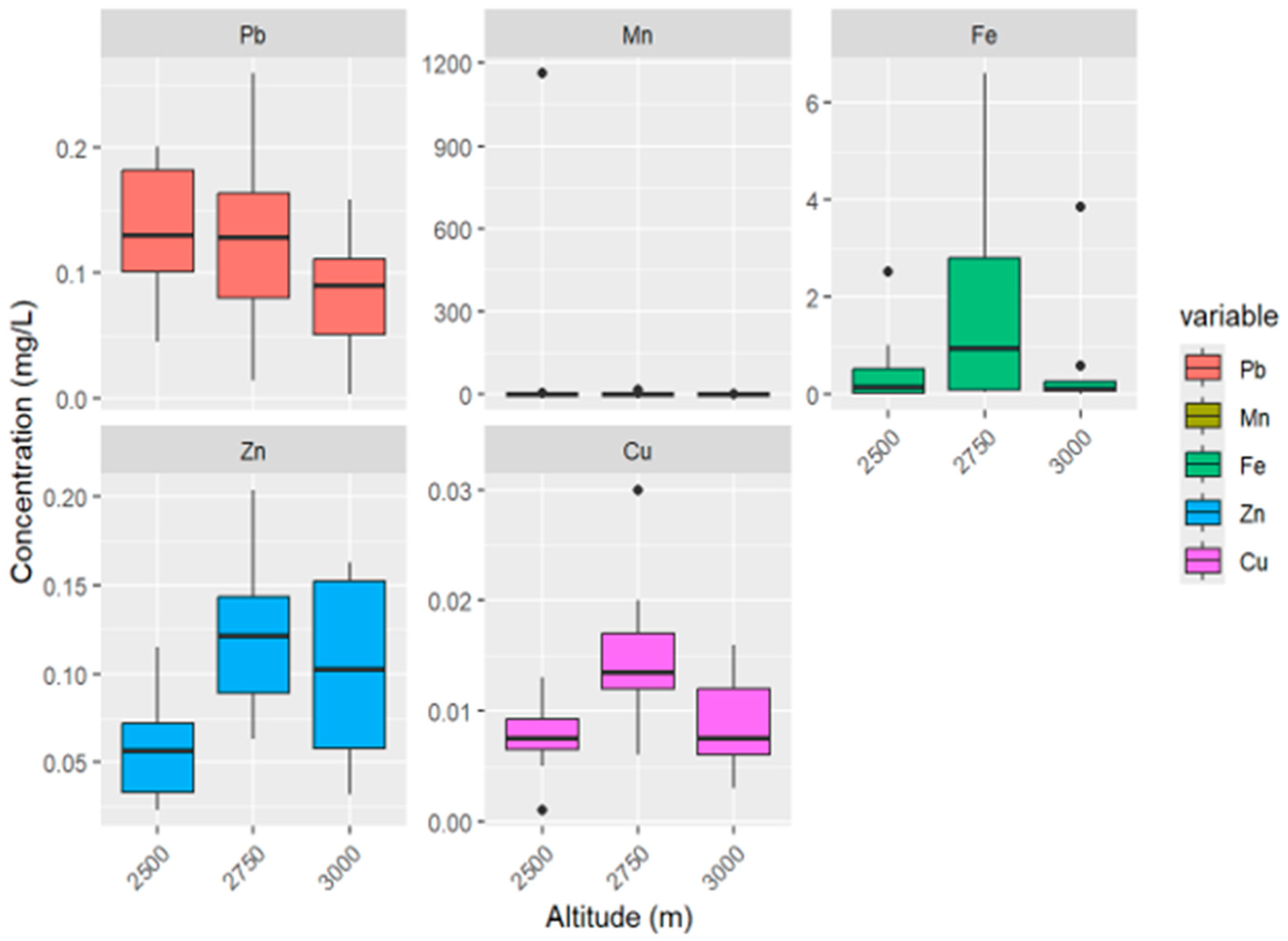

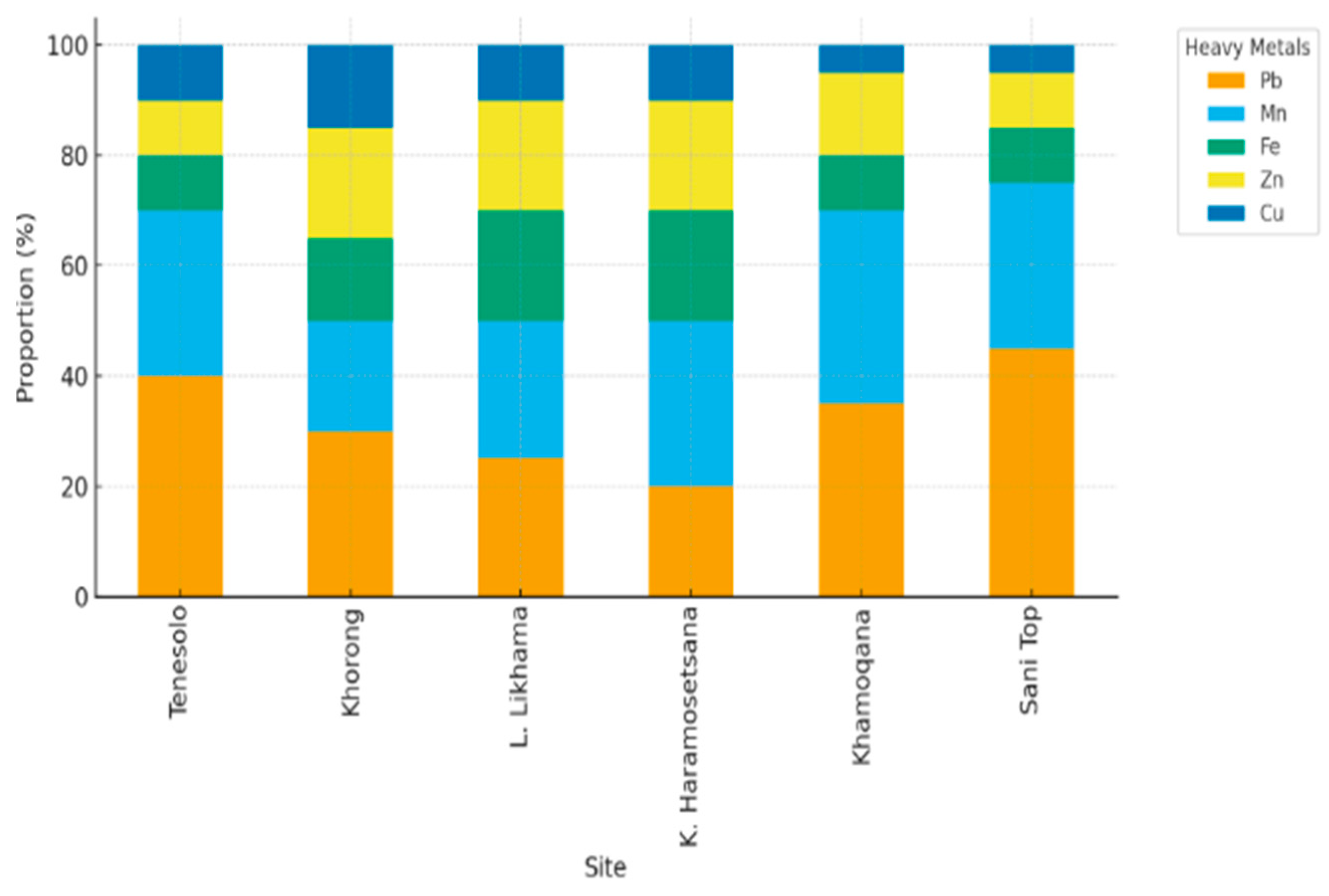

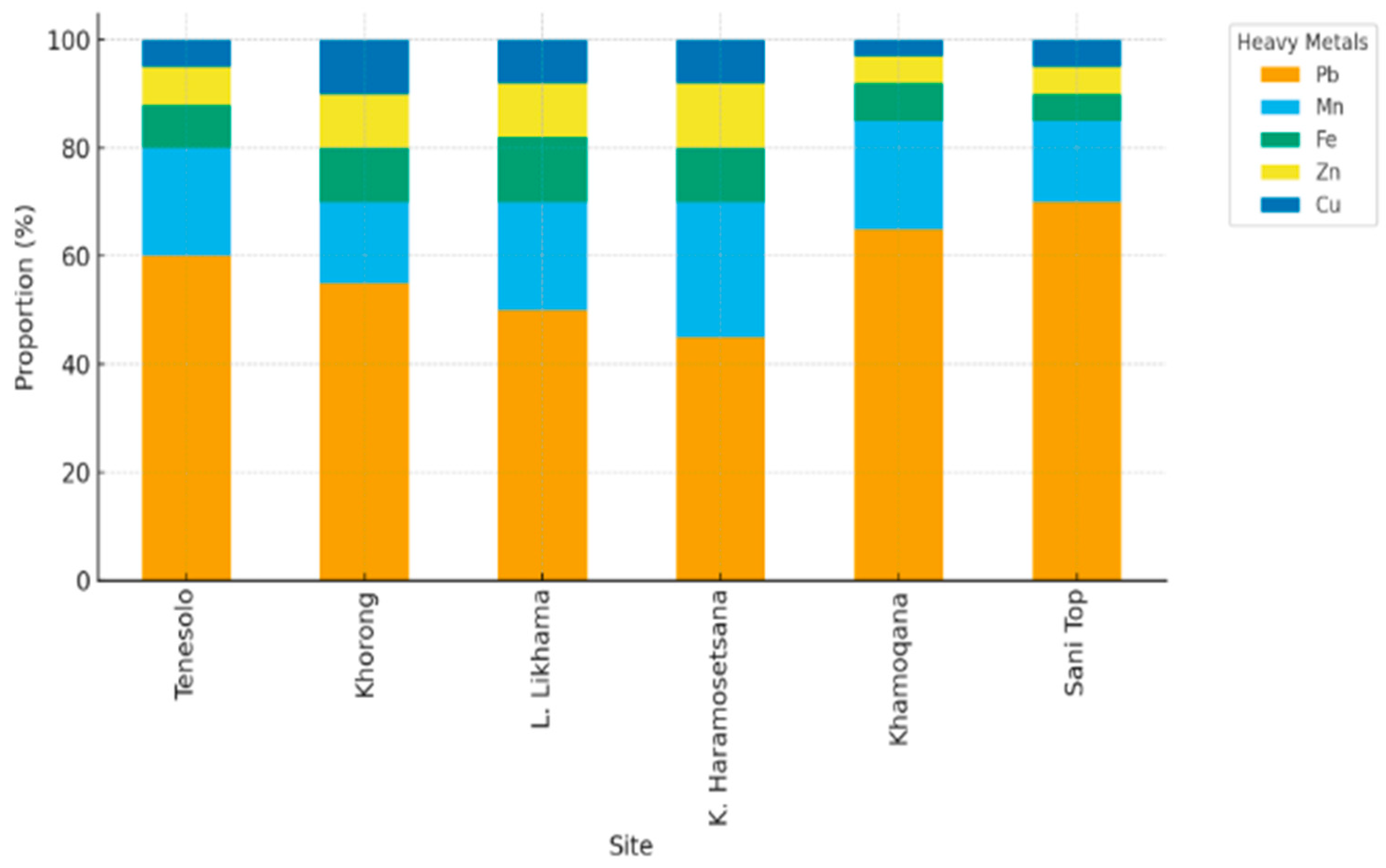

3.1. Characteristics of Heavy Metal Concentrations

3.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Assessment (PLI and HPI)

3.3. PCA, RDA & Correlation Analysis

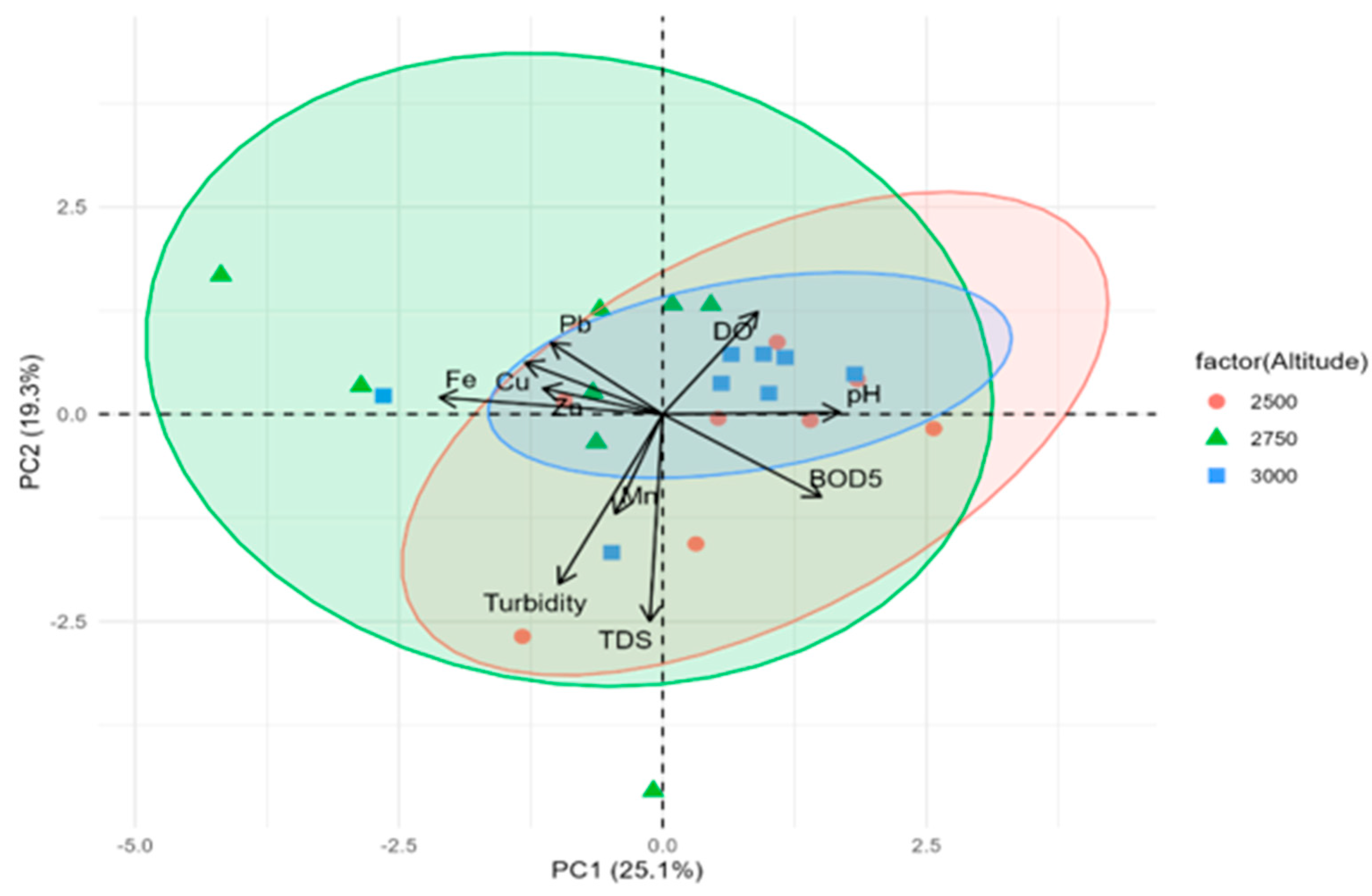

3.3.1. PCA Analysis

- Altitude-Dependent Heavy Metal Distribution Patterns

- a) Heavy Metal Dynamics in the Mid-Elevation Transitional Zone (2750m)

- b) Anthropogenic vs. Geogenic Source Distinction

- c) PCA as an Effective Tool for Heavy Metal Source Identification

- d) Metal-Specific Elevation Patterns

- Lead (Pb): Shows unique behaviour by continuing to increase with elevation, contrasting with other metals that peak at mid-elevations [71]

- Iron (Fe): Generally, it shows the highest concentrations among studied metals, with maximum levels of 1024±94.2 mg/kg reported in high-altitude lake sediments [10].

- Copper (Cu): Shows strong associations with anthropogenic activities, with concentrations 10 times higher than natural crustal values in contaminated areas [70].

- Zinc (Zn): Demonstrates variable patterns depending on local sources, with concentrations ranging from 41.68 to 77,287.5 mg/kg in wetland studies [72].

- e)

- Variance Explanation and Additional Factors

- Statistical Validation

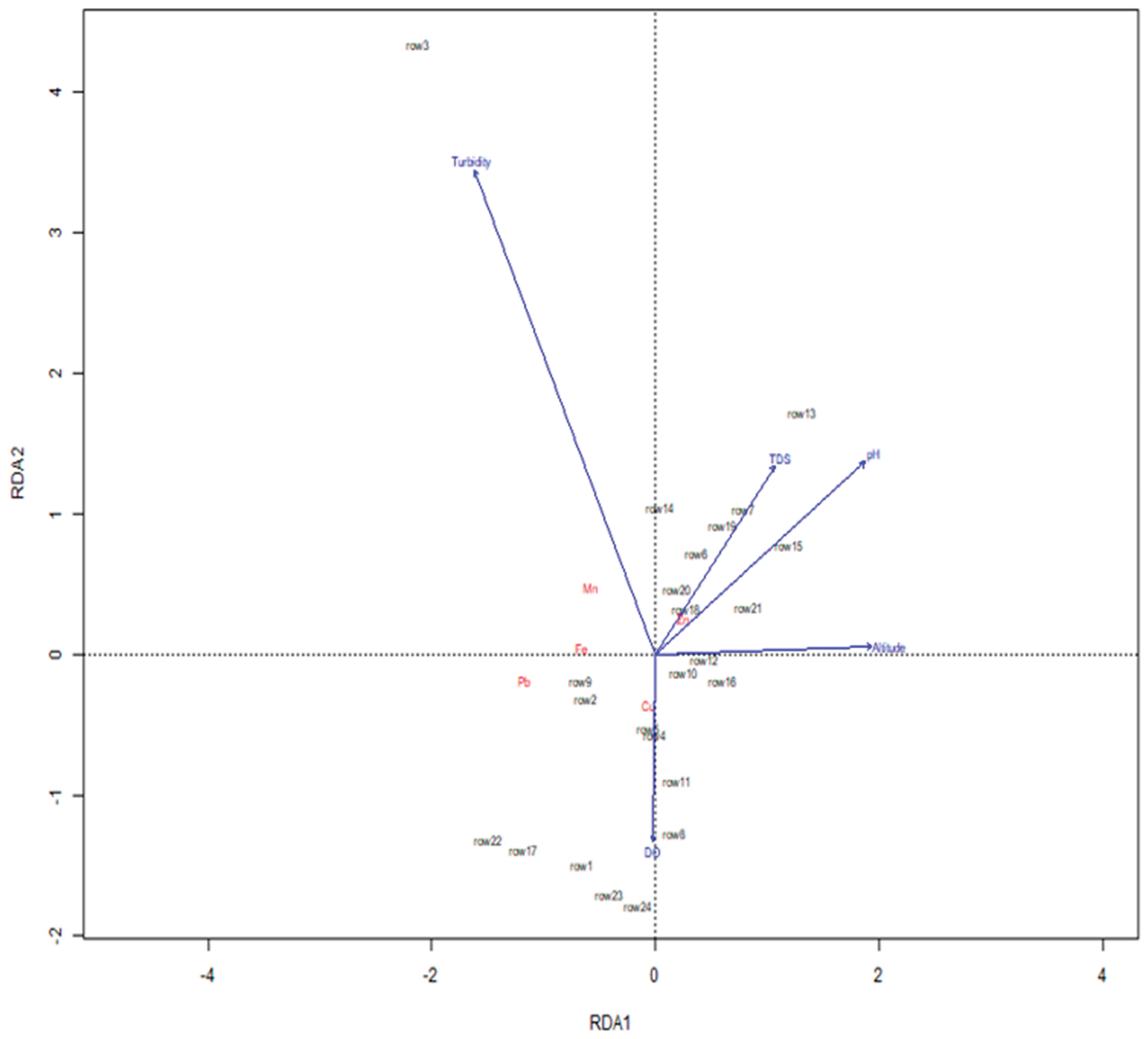

3.3.2. Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

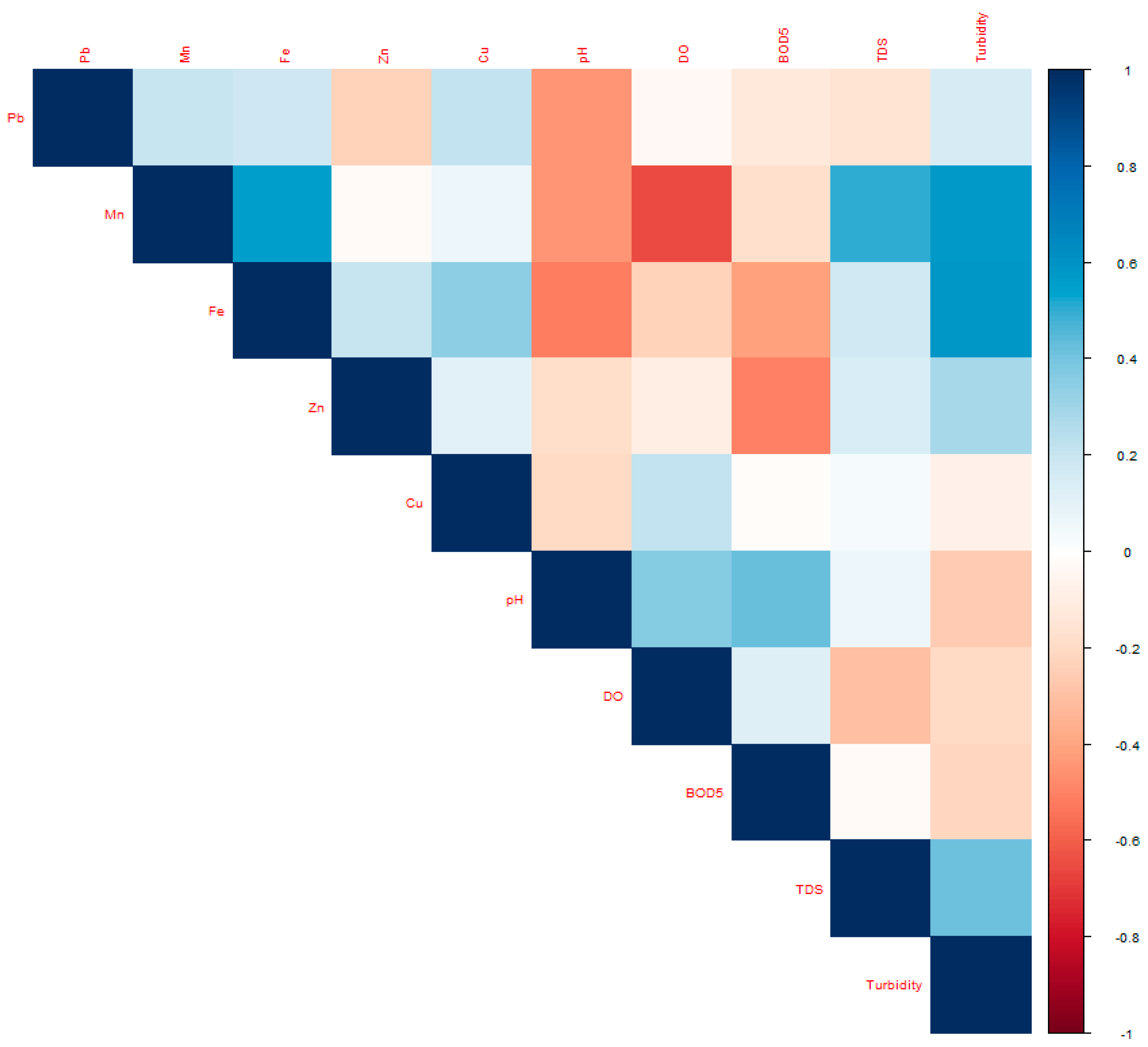

3.3.3. Correlation Analysis

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- a) Conclusions

- b) Recommendations

- c) Risk Assessment and Monitoring

- d) Source-Specific Management Strategies

- e) Contamination Hotspot Identification

- Limitations of the study

- Seasonal hydrological dynamics can influence heavy metal concentrations, and we have highlighted this limitation in the manuscript while interpreting the results, noting that future studies should include multi-seasonal sampling to capture temporal variability.

- The study considered a limited number of parameters and focused on the currently available analytical methods, which may restrict the comprehensiveness of the assessment. Future studies could expand the range of parameters and employ more advanced analytical techniques to provide a more detailed evaluation of wetland contamination.

- This study's limitation is the lack of direct comparisons between water quality and heavy metal concentrations in soils and plants across elevation gradients. While soil and plant research can reveal long-term metal accumulation trends, this study concentrated solely on surface water chemistry, which indicates short-term conditions. Consequently, potential relationships between water quality and metal accumulation in terrestrial or biological media across elevation gradients remain unexamined. Future research incorporating water, sediment, soil, and plant sampling along elevation transects is necessary for a more thorough understanding of how elevation influences metal dynamics.

- One limitation of the study is the lack of assessment of long-range atmospheric transport of pollutants to mountain environments, particularly in Lesotho. This study could not quantify the contribution of regional pollutant transport due to the absence of atmospheric deposition data, leading to a focus on local geogenic and land-use factors. Future research should incorporate atmospheric deposition measurements and back-trajectory analysis for a more comprehensive understanding of pollutant sources in alpine wetlands.

Supplementary Materials

References

- Uğulu; Şahin, I. F.; Akçiçek, E. Source identification and assessment of heavy metal contamination in different plant species in the alpine ecosystems of Mt. Madra. Physics and Chemistry of The Earth 2024, no. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, B. J. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and their Bioavailability, 3rd ed.; Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Yan, J. Constructed wetlands and hyperaccumulators for the removal of heavy metal and metalloids: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, no. 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rall, J. L.; Peters, R.; Mokoena, K. Wetland degradation and restoration potential in Lesotho's alpine zone: A landscape perspective. African Journal of Aquatic Science 2023, vol. 2(no. 48), 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, D.; Meng, J.; Wang, S.; Xiao, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Wu, P. Source apportionment, source-specific health risks, and control factors of heavy metals in water bodies of a typical karst basin in southwestern China. PLOS ONE 2024, vol. 19(no. 8), e0309142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, S. Altitudinal patterns of heavy metals and risk assessment in alpine wetland soils of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2019, no. 170, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPPC. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Shahab, A.; Huang, L.; Ali, M. U.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, Z.; Zou, Q.; Chen, Z.; Kang, B. Heavy Metals in Surface Sediment of Plateau Lakes in Tibet, China: Occurrence, Risk Assessment, and Potential Sources. Toxics 2023, vol. 11(no. 10), 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.; Zhao, H.; Ai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wen, Y.; Tian, L.; Mipam, T. D. Spatial distribution and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in alpine grasslands of the Zoige Basin, China. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2020, vol. 11(no. 1093823), 2593–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Ali, W.; Jadoon, I. A.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, J.; Ullah, H. Assessment of potentially toxic elements contamination in high altitude lake sediments of Swat valley, northern Pakistan. Environmental Earth Sciences 2024, vol. 4(no. 83), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Sun, C.; Wang, J.; Wand, C. Q. Meng, Heavy metal pollution in high-altitude regions: Case study from a typical small watershed in the Qilian Mountains. Environmental Pollution 2017, vol. 31., 90–297. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Shahab, A.; Huang, L.; Ubaid Ali, M.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, Z.; Zou, Q.; Chen, Z.; Kang, B. Heavy Metals in Surface Sediment of Plateau Lakes in Tibet, China: Occurrence, Risk Assessment, and Potential Sources. Toxics 2023, vol. 11(no. 10), 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.; Zhao, H.; Ai, V.; Zhang, S.; Wen, Y.; Tian, L.; Mipam, T.. D. Spatial distribution and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in alpine grasslands of the Zoige Basin, China. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2023, vol. 11, no. 1093823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, F.; Guo, W.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Comparative ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in high-elevation wetlands on the Hengduan Mountains. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, vol. 210, no. 111859. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Khan, M. A.; Shah, M. T.; Rehman, S. Heavy metal contamination and ecological risk assessment in sediments of wetlands in northern Pakistan. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2019, vol. 191(no. 11), 676. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, S.; Jadoon, W. A.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, J.; Ullah, U. Assessment of potentially toxic elements contamination in high altitude lake sediments of Swat valley, northern Pakistan. Environmental Earth Sciences 2024, vol. 4(no. 83), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. Elevational patterns, source identification and ecological risks of heavy metals in tropical alpine soils. Earth and Environment 2025, vol. 53(no. 3), 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonge, B. A.; Tabot, P. T.; Bonsou, L. K.; Mumbang, C. Heavy metal contamination in soils and plants from Mount Cameroon: A volcanic and mining environment. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2015, vol. 12(no. 9), 870–881. [Google Scholar]

- Sishu, F. K.; Melese, T. B.; Aklog, D. Assessment of heavy metal and other chemical pollution in Lake Tana along urban peripheries, Ethiopia. Water Practice and Technology 2024, vol. 4(no. 19), 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astatkie, H.; Ambelu, A.; Mengistie, E. Contamination of stream sediment with heavy metals in the Awetu watershed of southwestern Ethiopia. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, no. 9, 658737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chignell, S. M.; Laituri, M.; Young, N. E.; Evan. Afroalpine wetlands of the Bale Mountains, Ethiopia: Distribution, dynamics, and conceptual flow model. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 2019, vol. 2(no. 109), 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silas, E. N.; Ombaka, O.; Chomba, E.; Muraya, M. M. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in water and sediment of River Thiba, Kirinyaga County, Kenya. International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering 2024, vol. 8(no. 10), 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondiere, V. B.; Vincent, M. O.; Ochieng, A. A.; Oduo, D.O.F. Assessment of heavy metals contamination in Lake Elementaita drainage basin, Kenya. International Journal of Scientific Research in Science, Engineering and Technology 2017, vol. 4(no. 3), 471–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Aji, D.; Li, P.; Hu, C. Characterization of heavy metal contamination in wetland sediments of Bosten Lake, China: Source identification and ecological risk assessment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, vol. 12(no. 31), 18234–18248. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental chemistry and ecotoxicology of hazardous heavy metals: Environmental persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation. Journal of Chemistry 2019, no. 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedunkova; Kuznietsov, P. Dataset on heavy metal pollution assessment in freshwater ecosystems. Scientific Data 11. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Altitudinal distribution of trace metals in mountain soils and influencing factors. Science of The Total Environment 2020, no. 712, 135664. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Application of multivariate statistical methods to evaluate spatial distribution of heavy metals in river water. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, vol. 8(no. 27), 8760–8774. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Sun, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Heavy metal pollution in high-altitude regions: Case study from a typical small watershed in the Qilian Mountains. Environmental Pollution 2017, no. 31, 90–297. [Google Scholar]

- Edenborn, H. M.; Brickett, L. A. Determination of manganese stability in a constructed wetland sediment using redox gel probes. Geomicrobiology Journal 2002, vol. 19(no. 5), 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N. Controlling factors and mechanism of groundwater quality variation in semi-arid region of South India: An approach of water quality index (WQI) and health risk assessment (HRA). Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2020, vol. 6(no. 42), 1725–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, B.; Singh, M. Application of the Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI) and correlation analysis for groundwater contamination assessment. Journal of Environmental Monitoring 2010, vol. 7(no. 12), 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kotze, D. C.; Breen, C. M. The Role and Importance of Wetlands in Lesotho; Institute of Natural Resources, University of Natal.

- Muhammad, S.; Shah, M.; Khan, S. Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals and Their Source Apportionment in Drinking Water of Kohistan Region, Northern Pakistan. Microchemical Journal 2011, no. 98, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WaterNet. Integrated Catchment Management for the Protection of High-Altitude Wetlands in the SADC Region. WaterNet Policy Brief Series, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- APHA (American Public Health Association); American Public Health Association. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (2, 1st ed.; Washington, DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Aji, D.; Li, P.; Hu, C. Characterization of heavy metal contamination in wetland sediments of Bosten Lake and evaluation of potential ecological risk, China. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2024, vol. 12, no. 1398849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Du, W.; Yu, S.; Zhang, W. Distribution, sources, and probabilistic risk assessment of heavy metals in the wetland water–sediment system: Based on CEWQI, PLI, PMF, and two-dimensional Monte Carlo method. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2025, vol. 276(no. 2026), 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatkın, K.; Çiftçi, N.; Ayas, D.; Köşker, A. R. Ecological Risk Assessment of Metal and Metalloid Contamination in a Ramsar-Protected Mediterranean Lagoon (Paradeniz, Türkiye). Thalassas: An International Journal of Marine Sciences 2025, vol. 41(no. 256). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turekian, K. K.; Wedepohl, K. H. Distribution of the elements in some major units of the Earth’s crust. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1961, vol. 72(no. 2), 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, C.; Garrett, R. G. Geochemical background—concept and reality. Science of the Total Environment 2005, vol. 350(no. (1–3)), 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D. L.; Wilson, J. Q.; Harris, C. R.; Jeffrey, D. W. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgoländer 1980, vol. 33, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, D.; Singh, S. K.; Shukla, D. N. Assessment of river water quality and ecological diversity through multivariate statistical techniques, and earth observation dataset of rivers Ghaghara and Gandak, India. International Journal of River Basin Management 2017, no. 15, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Bose, J. Evaluation of heavy metal pollution index for surface and groundwater in and around a coal mining area, India. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2001, no. 173, 643–658. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, S. V.; Nithila, P.; Reddy, S. J. Estimation of heavy metals in drinking water and development of heavy metal pollution index. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 1996, vol. 2(no. 31), 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, R.; Joshi, P. Geogenic manganese enrichment in mountainous groundwater. Environ Earth Sci. 2019, vol. 12(no. 78), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H.; Fujii, K. Turbidity and conductivity variations in alpine spring waters. Hydrol Process 2016, vol. 18(no. 30), 3330–3338. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Ali, S.; Nel, W.; Shah, S. Elevation-dependent variation of heavy metals in sediments of alpine wetlands in northern Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, no. 194, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, C.; Xie, Z.; Li, C. Spatial Distribution, Risk Assessment and Source Analysis of Heavy Metals in the Sediments of Jinmucuo Lake, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Sustainability 2024, vol. 16(no. 23), 10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, P.; He, Q.; Ning, J.; Li, X. Experimental insights into iron and manganese transformation in soil during groundwater fluctuations. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2025, vol. 275, no. 104677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Cao, X.; Xia, X.; Wang, B.; Teng, Y.; Li, X. Elevated Fe and Mn Concentrations in Groundwater in the Songnen Plain, Northeast China, and the Factors and Mechanisms Involved. Agronomy 2021, vol. 11(no. 12), 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, Q.; Qian, S.; Li, F. Spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of antibiotics and heavy metals in the Yitong River basin and ecological risk assessment. Scientific Reports 2023, vol. 13(no. 1), 4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Shahab, A.; Li, J.; Xi, B.; Sun, X.; He, H. Distribution, ecological risk assessment and source identification of heavy metals in surface sediments of Huixian karst wetland, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2019, vol. 185, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Eziz, M.; Hu, Y.; Subi, X. Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal(loid)s in the Overlying Water of Small Wetlands Based on Monte Carlo Simulation. Toxics 2024, vol. 12(no. 7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, M.; Afzali, K. N.; Jahan, S.; Strezov, V.; Soleimani-Sardo, M. Pollution and contamination assessment of heavy metals in the sediments of Jazmurian playa in southeast Iran. Scientific Reports 2020, vol. 10(no. 4775). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C. Dominant environmental factors influencing soil metal concentrations of Poyang Lake wetland, China: Soil property, topography, plant species and wetland type. CATENA 2021, vol. 207(no. 105601). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Zeb, A.; Shaik, M. R.; Assal, M. Spatial distribution of potentially toxic elements pollution and ecotoxicological risk of sediments in the high-altitude lakes ecosystem. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 2024, vol. 135(no. 103655). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar Korkanç, S.; Korkanç, M.; Amiri, A. F. Effects of land use/cover change on heavy metal distribution of soils in wetlands and ecological risk assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2024, vol. 923(no. 171603). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First Addendum; World Health Organization.

- Nuss, P.; Eckelman, M. J. Life Cycle Assessment of Metals: A Scientific Synthesis. PLoS ONE 2014, vol. 7(no. 9), e101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorocki, S.; Korzeniowska, J. Soil Contamination with Metals in Mountainous: A Case Study of Jaworzyna Krynicka in the Beskidy Mountains (Poland). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, vol. 20(no. 6), 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Gong, L.; Xia, S. Spatial distribution, source identification, and risk assessment of heavy metals in riparian soils of the Tibetan plateau. Environmental Research 2023, vol. 237(no. Part 2), 116977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Mei, X.; Gu, Z.; Li, X. Topography-driven variability in atmospheric deposition and soil distribution of cadmium, lead and zinc in a mountainous agricultural area. Scientific Reports 2025, vol. 15(no. 20894). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. T. Principal component analysis. In Springer Series in Statistics, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Forootan, E. Analysis of trends of hydrologic and climatic variables. Soil and Water Research 2019, vol. 14(no. 3), 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonah, U. E.; Mbong, E. O.; Akpan, A. U.; Udo, A.; Chukwudi, P.; Uwagboi, I. S. Assessment of heavy metal contamination and ecological risks in cultivated wetlands of Northern Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Scientia Africana 2025, vol. 24(no. 3), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, N. A.; Stevens, D. K. Transforming Complex Water Quality Monitoring Data into Water Quality Indices. Water Resource Management 2025, vol. 39, 3883–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Mei, X.; Gu, Z.; Li, X. Topography-driven variability in atmospheric deposition and soil distribution of cadmium, lead and zinc in a mountainous agricultural area. Scientific Reports 2025, vol. 15(no. 1), 20894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, A.; Riahi, H. Evaluation of Heavy Metal Pollution Indices for Surface Water of the Sarcheshmeh Copper Mine using Multivariate Statistical Methods and GIS. Iranian Journal of Soil and Water Research 2019, vol. 50(no. 1), 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dusza, Y.; Sanchez-Vallet, A.; Toju, H. PCA-based population structure inference with generic clustering algorithms. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, vol. 1(no. 23), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon 2020, vol. 9(no. 6), e04691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navrátil, T.; Rohovec, J.; Žák, K.; Šebek, O.; Mihaljevič, M.; Drahota, P.; Beneš, V. Metal contamination of the environment by old mining activities in the Ore Mountains (Czech Republic). Applied Geochemistry 2019, no. 48, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sîrbu, J.; Benedek, A. M.; Sîrbu, M. Variation partitioning in double-constrained multivariate analyses: linking communities, environment, space, functional traits, and ecological niches. Oecologia 2021, vol. 197(no. 1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Chang, J.; Peng, L.; Wang, S.; Hong, Y.; Liu, G.; Ding, S. Evaluation of water quality and heavy metals in wetlands along the Yellow River in Henan Province. Sustainability 2020, vol. 12(no. 4), 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Han, X.; Yang, Z.; Dong, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, N.; Qu, Z.; Wang, C. In situ, high-resolution evidence for the release of heavy metals and environmental drivers. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2024, vol. 11(no. 132681). [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K. P.; Malik, A.; Mohan, D.; Sinha, S. Multivariate statistical techniques for the evaluation of spatial and temporal variations in water quality of Gomti River (India). Water Research 2017, vol. 38(no. 18), 3980–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Q. Risk assessment and seasonal variations of dissolved trace elements and heavy metals in the upper Han River, China. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, vol. 181(no. (1–3)), 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R. A. Bed sediment–associated trace metals in an urban stream, Oahu, Hawaii. Environmental Geology 2000, vol. 39, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Shahnaz, Q.-u.-A.; Inamullah, R.; Sajjad, A.; Nawab, D.; Rehman, S. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in drinking water sources of Kohistan region, Pakistan. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2013, vol. 11(no. 48), 137. [Google Scholar]

| Sub -catchment | Wetlands | Coordinates | Altitude (masl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Longitude | |||

| Senqunyane | Khorong | −29.43708 | 28.26923 | 2500-2550 |

| Tenesolo | −29.44836 | 28.14759 | 2552-2600 | |

| Khubelu | Letšeng - La- Likhama | −29.076355 | 28.836095 | 3040-3800 |

| Koting -sa-ha Raramosetsana | −29.022686 | 28.871324 | 3087-3155 | |

| Sani Pass | Sani Top | −29.563552 | 29.247207 | 2891-2995 |

| Khamoqana | −29.457178 | 28.268094 | 2839-2880 | |

| Metal | WHO Limit (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Lead (Pb) | 0.01 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.40 |

| Iron (Fe) | 0.30 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 3.00 |

| Copper (Cu) | 2.00 |

| PLI score | Category |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | Unpolluted |

| 1–2 | Slightly polluted |

| 2–3 | Moderately polluted |

| 3–5 | Highly polluted |

| HPI score | Category |

|---|---|

| 0–20 | Excellent |

| 21–40 | Good |

| 41–60 | Moderate |

| 61–80 | Bad |

| 81–100 | Severe |

| Parameters | Mean | Std deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| Mn | 49.46 | 236.99 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1162.00 | 1162.00 | 4.30 |

| Fe | 0.98 | 1.63 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 6.59 | 6.58 | 1.97 |

| Zn | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.36 |

| Cu | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.27 |

| Turbidity | 201.90 | 312.56 | 40.80 | 0.00 | 954.00 | 954.00 | 1.37 |

| EC | 196.75 | 186.11 | 133.50 | 58.00 | 883.00 | 825.00 | 2.29 |

| Site | PLI | Pollution Level |

|---|---|---|

| Tenesolo | 3.04 | Highly high |

| Khorong | 1.04 | Slightly polluted |

| Letša-la-Likhama | 1.57 | Slightly polluted |

| Koting -sa-ha Raramosetsana | 1.33 | Slightly polluted |

| Khamoqana | 2.23 | Moderately polluted |

| Sani Top | 5.54 | Very highly polluted |

| Site | HPI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Tenesolo | 1,705.8 | Critically Polluted (≫100) |

| Khorong | 847.1 | Highly Polluted |

| Letša-la-Likhama | 951.3 | Highly Polluted |

| Koting -sa-ha Raramosetsana | 565.2 | Highly Polluted |

| Khamoqana | 1,058.2 | Critically Polluted |

| Sani Top | 1,451.4 | Critically Polluted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).