1. Introduction

Coastal dune systems are dynamic barriers formed by the accumulation of terrigenous and marine sand transported by the wind [

1]. These systems provide ecosystem services by controlling floods and storm surges, modulating the effects of extreme events on human systems, acting as rainwater filtration zones, providing essential habitat for plants and invertebrates, and serving as feeding and nesting sites for birds and turtles. They also provide very relevant recreational services [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Coastal dunes serve as regulators of natural hazards [

1,

5,

6] and stabilizers of the coastline, becoming the most relevant sedimentation environments on the planet [

7,

8,

9].

Highly specialized (such as psammophilous and halophytic plants), rare, and endangered species abound in these environments [

10]. Vegetation plays an important role in the dynamics of coastal dunes. Pioneer plants (mostly psammophilous and halophytic) promote dune formation by acting as obstacles that slow or stop the movement of wind-driven sediments [

11]. In later stages of ecological succession (mainly on foredunes or transgressive dune fields), plant communities stabilize dune systems, retain sand, and help mitigate erosion by wind, rain, and waves by decreasing sand mobility. In addition to its protective and stabilizing role on the coast [

9,

12], vegetation increases the landscape value and tourist appeal of beaches [

13].

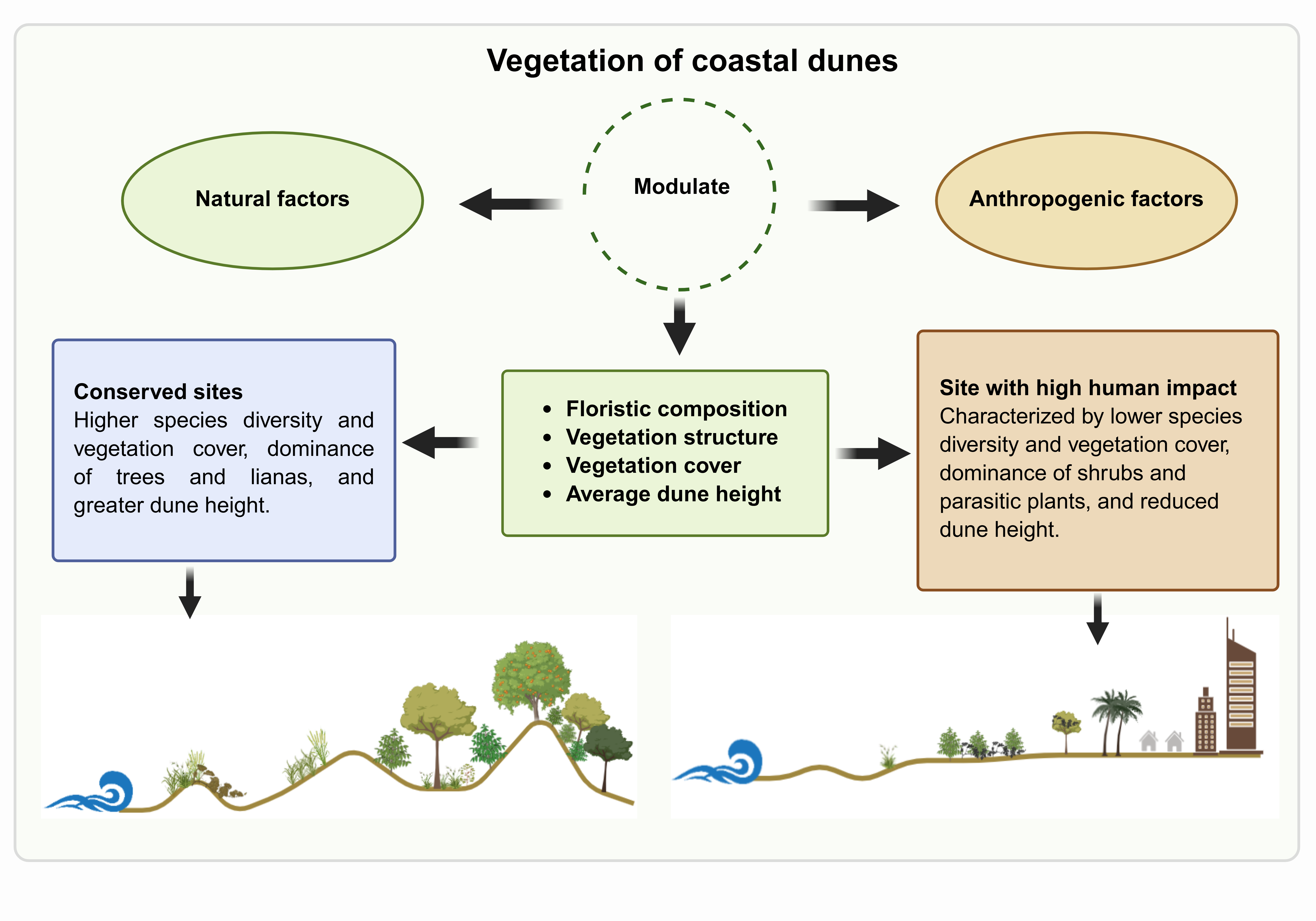

The dynamics of coastal dunes and their plant communities are commonly affected and shaped by both natural and human-induced disturbances. The proximity to the ocean determines an inland gradient that affects the distribution and composition of the flora [

14,

15,

16]. Some environmental factors that affect the ocean-inland gradient plant distribution include salt spray and soil salinity [

17], soil moisture, soil texture, organic matter content, radiation and temperatures [

18], sand movement and freshwater flooding [

16], terrain inclination [

19], and nutrient contents [

16,

20]. Climatic factors, such as strong winds [

18], tropical cyclones, and winter storms, alter the topography and plant communities, which contribute to the natural dynamics of the coasts [

21].

Anthropogenic factors also have an increasing impact on the vegetation of the beach and coastal dunes [

22]. Urban and tourist development have modified dune systems, reducing their extension and vegetation cover [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Waste disposal has turned these ecosystems into sinks of anthropogenic waste [

28], altering the sedimentation mechanisms and structure of the dunes [

29]. Other factors, such as mining, invasive species, and vehicular traffic, have negatively impacted the topography and food webs of these ecosystems [

30].

Recent studies show the influence of natural and anthropogenic factors and their interaction in explaining the variation in vegetation cover and floristic diversity [

22,

31]. However, the precise degree to which these pressures, individually or in interaction, modulate the floristic diversity of the coastal dune system is still unknown. The conservation level of the beach and coastal dunes vegetation can be site- or region-specific, given the local particularity of the stressing agents and their intensity. In particular, the few studies [

32,

33] focused on the sandy coastal systems of the northern Colombian Caribbean reveal intense natural and human-induced disturbances [

30,

34]. However, the floristic baseline of the region is unknown, and the natural and anthropogenic disturbance agents influencing the conservation status of beaches and dunes have not yet been identified. Such knowledge is necessary to plan appropriate strategies for the conservation and restoration of these ecosystems.

Based on the above, the study has the following objectives: (1) to determine the impact of natural and anthropogenic factors that may be affecting floristic diversity in coastal dune systems and (2) to evaluate the conservation status among coastal dune systems in the northern Colombian Caribbean. The study shows differences in the composition and structure of plant communities that are associated with natural and human-induced disturbances. Management alternatives should consider the environmental factors (natural and anthropogenic) affecting vegetation to improve the conservation of the plant diversity of the coastal dunes along the Colombian Caribbean coast.

2. Results

We found differences between the study sites regarding natural and human-induced agents, which, in turn, affected plant composition and community structure.

2.1. Natural Factors

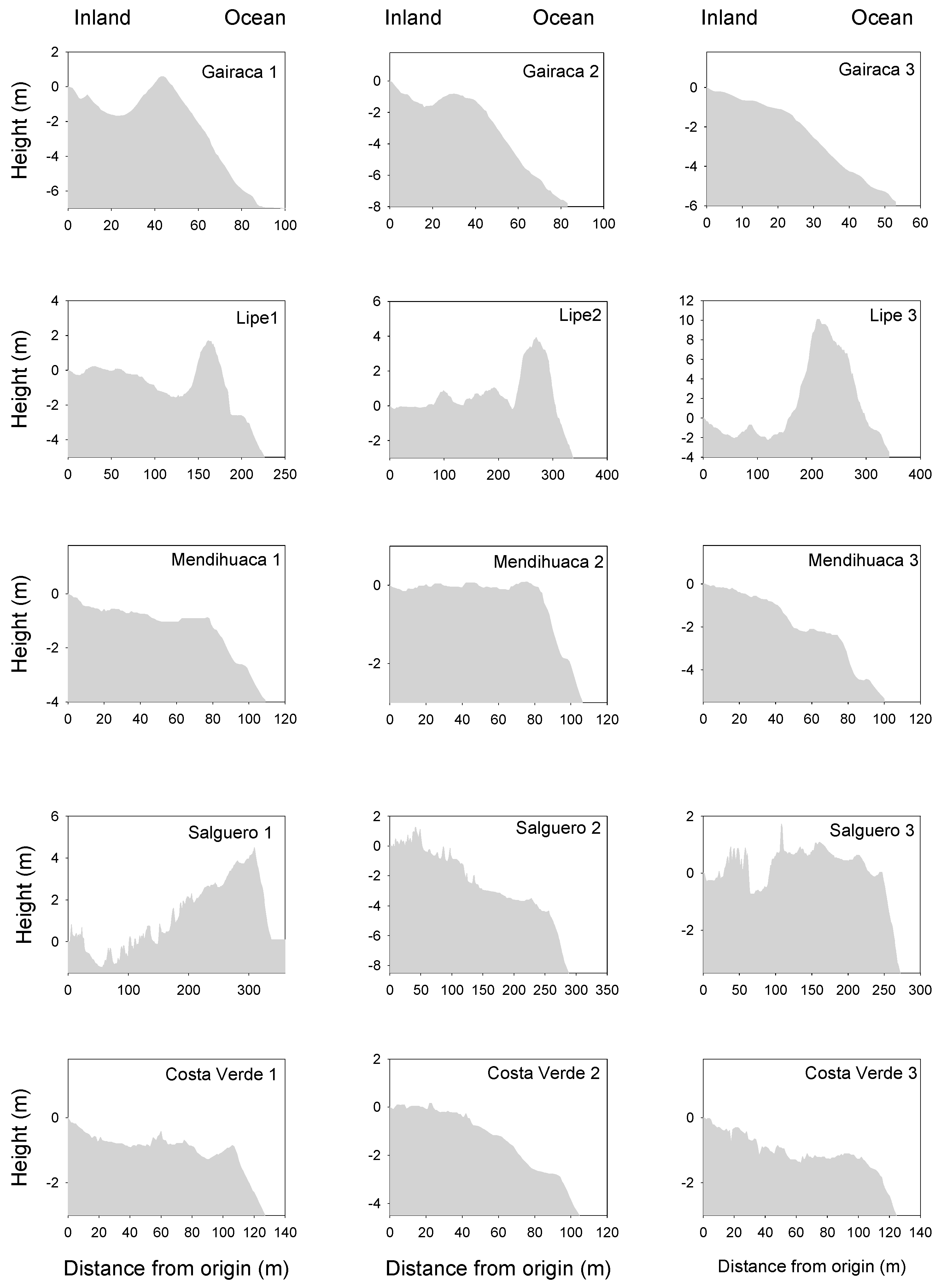

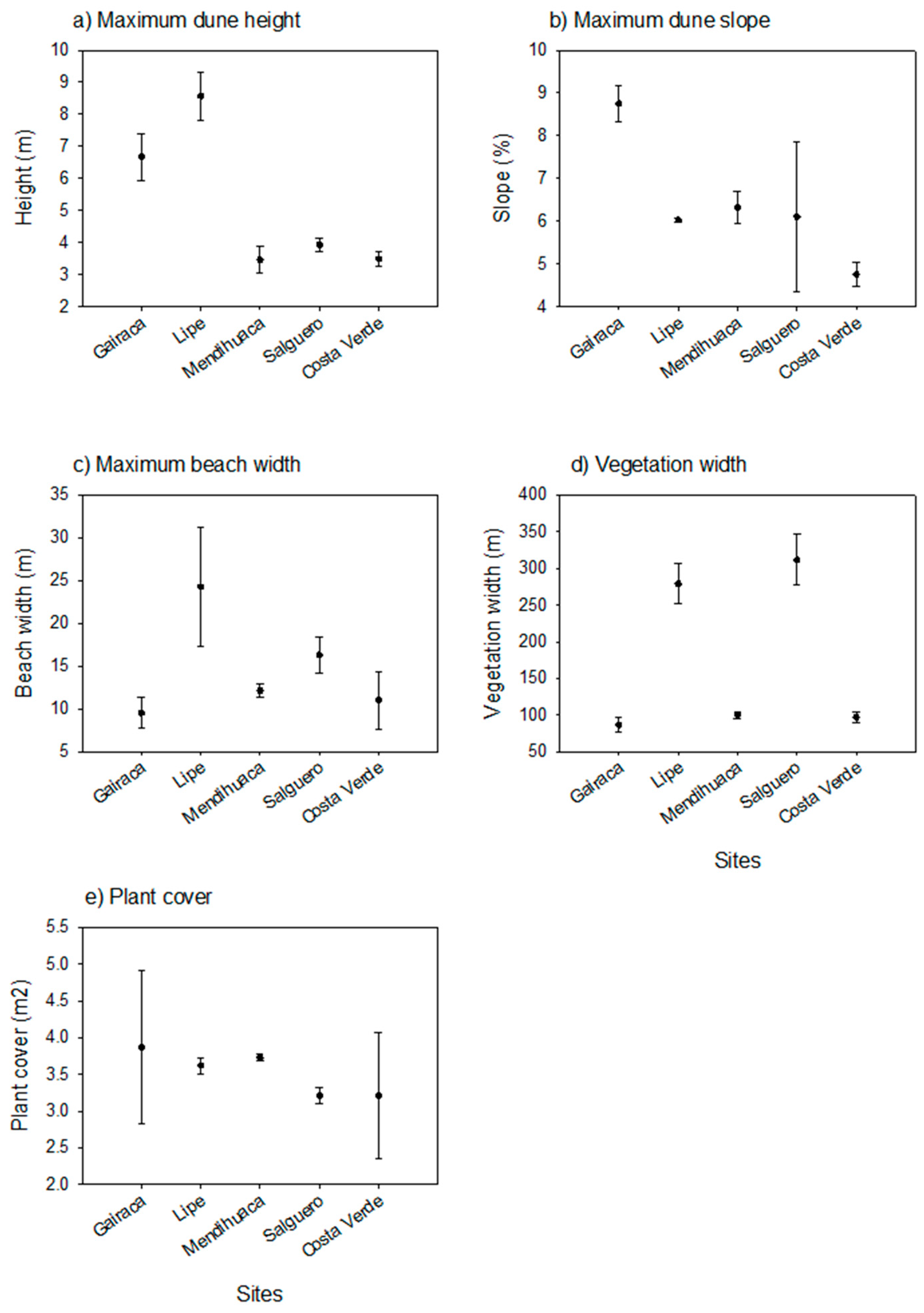

Differences in the natural environmental factors were identified among the five sites. The most preserved sites (Gairaca and Lipe) stood out for having the highest dune height (

Figure 1), whereas the most disturbed beaches showed steeper slopes, especially closest to the beach (see for instance, Salguero and Costa Verde). The mean maximum dune slope was measured in Gairaca, while the maximum mean plant cover per plot was observed in Lipe, the second most preserved site (

Figure 2). In turn, beach width was noticeably larger in Lipe, compared with the other sites (

Figure 2). The width of sampled vegetation was very ample in Lipe and Salguero, while plant cover was very variable in Gairaca, but mean values were similar between sites (

Figure 2).

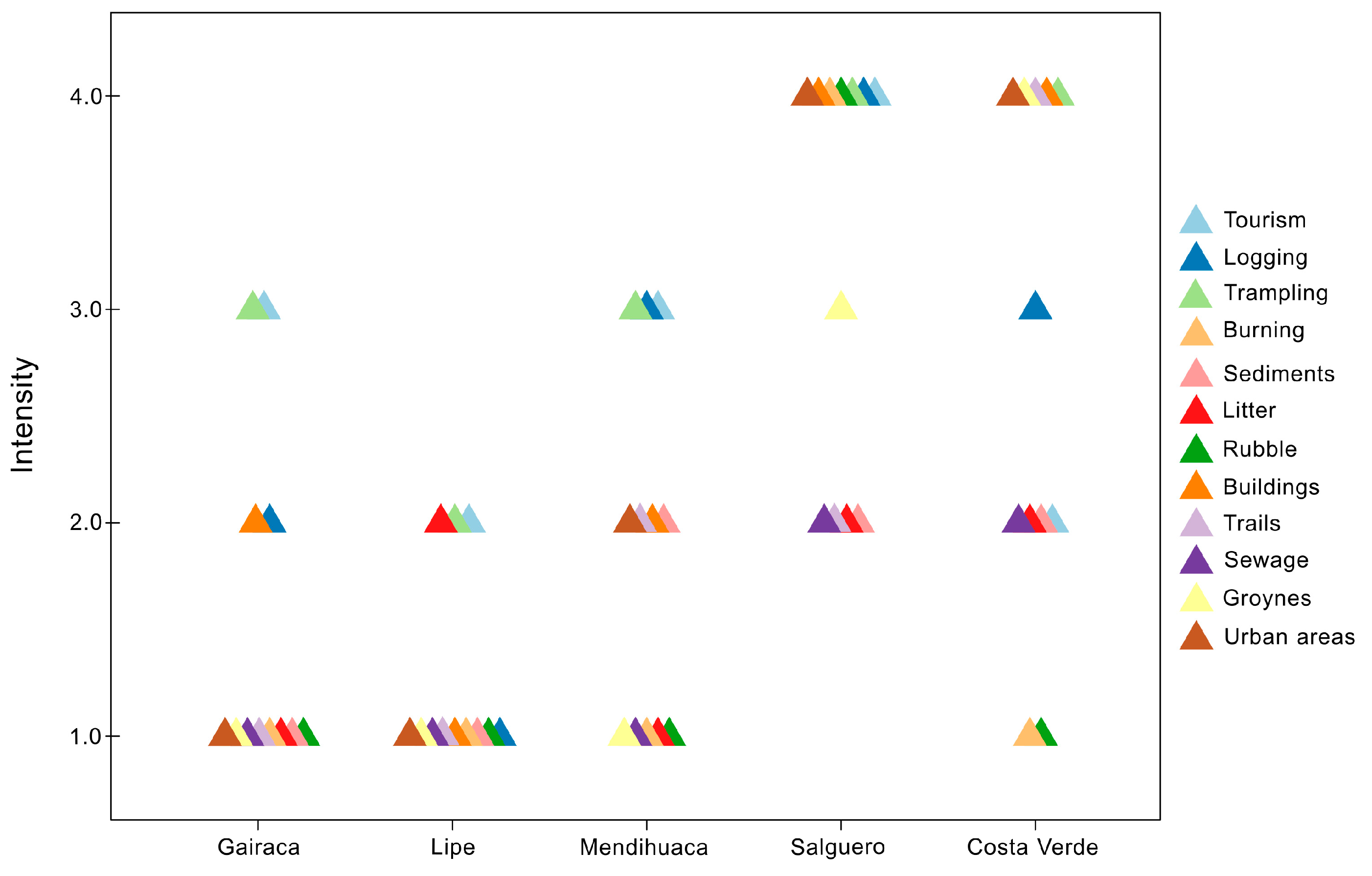

2.2. Anthropogenic Factors

The analysis of 12 anthropogenic factors determined the intensity of disturbance at the five beaches. All exhibit a gradient of disturbance intensity, from low (2) to intermediate (3) and high (4). According to this analysis, Lipe and Gairaca were relatively well-preserved beaches with a lower intensity of anthropogenic activities. In turn, Salguero and Costa Verde are highly exposed to a larger number of more intense human disturbances (

Figure 3). Urbanization, construction, and trampling were the most significant disturbances factors affecting the beaches. Mendihuaca showed intermediate conservation values because the high coverage values are associated with the presence of agriculturally important or introduced species

The two beaches with the greatest intensity of disturbance were undoubtedly Salguero and Costa Verde. At Costa Verde, there was high anthropogenic disturbance in five variables: construction, trampling, groins, and roads, and intermediate disturbance in logging, with low disturbance in sewage, roads, and sediments. In turn, Salguero had the highest anthropogenic disturbance; of the 12 variables considered, seven are in the high category (urbanized areas, construction, burning, debris, trampling, logging, and tourism), 1 in the intermediate category (jetties), and 4 in the low category, in sewage, roads, garbage, and sediment extraction (

Figure 3).

2.3. Floristic Composition

A total of 133 species, included in 113 genera and 55 families, were identified in our study sites, the northern Colombian Caribbean coast (see Appendix 1). The families with the largest number of species were Fabaceae with 29 species, Poaceae (10 species), Malvaceae (8 species), Capparaceae (7), Cactaceae (5), Polygonaceae (4), and Bignoniaceae, Convolvulaceae, and Cyperaceae (3 species each). Morisonia was the most represented genus with seven species, followed by Coccoloba, Ipomoea, and Melochia with three each; the genera Bursera, Erythroxylum, Portulaca, Chloris, Cenchrus, Cyperus, Tephrosia, and Spermacoce had two species, and the remaining 35 genera only had one species. Morisonia was recorded on preserved beaches such as Gairaca and Lipe, with 6 and 2 species, respectively. Morisonia odoratissima was a common species among these beaches and was absent from the remaining ones.

Among the most frequently found species are: Alternanthera flavescens, Neltuma juliflora, and Pithecellobium dulce in Lipe, Gairaca, Salguero, and Costa Verde, while creepers such as Ipomoea pes-caprae and Canavalia rosea were present in Mendihuaca, Gairaca, and Costa Verde. Leuenbergeria guamacho and Melochia tomentosa are common in sites such as Lipe, Gairaca, and Salguero. Sporobolus virginicus is a common species on the beaches of Gairaca, Salguero, and Costa Verde. It is worth noting that 47 species were recorded on a single beach.

Introduced species such as Calotropis procera and Tribulus cistoides were found on the beaches of Lipe, Salguero, and Costa Verde. Hymenocallis littoralis (Amaryllidaceae), a rare species with a limited distribution, was recorded in Mendihuaca (see Appendix 1).

2.4. Diversity

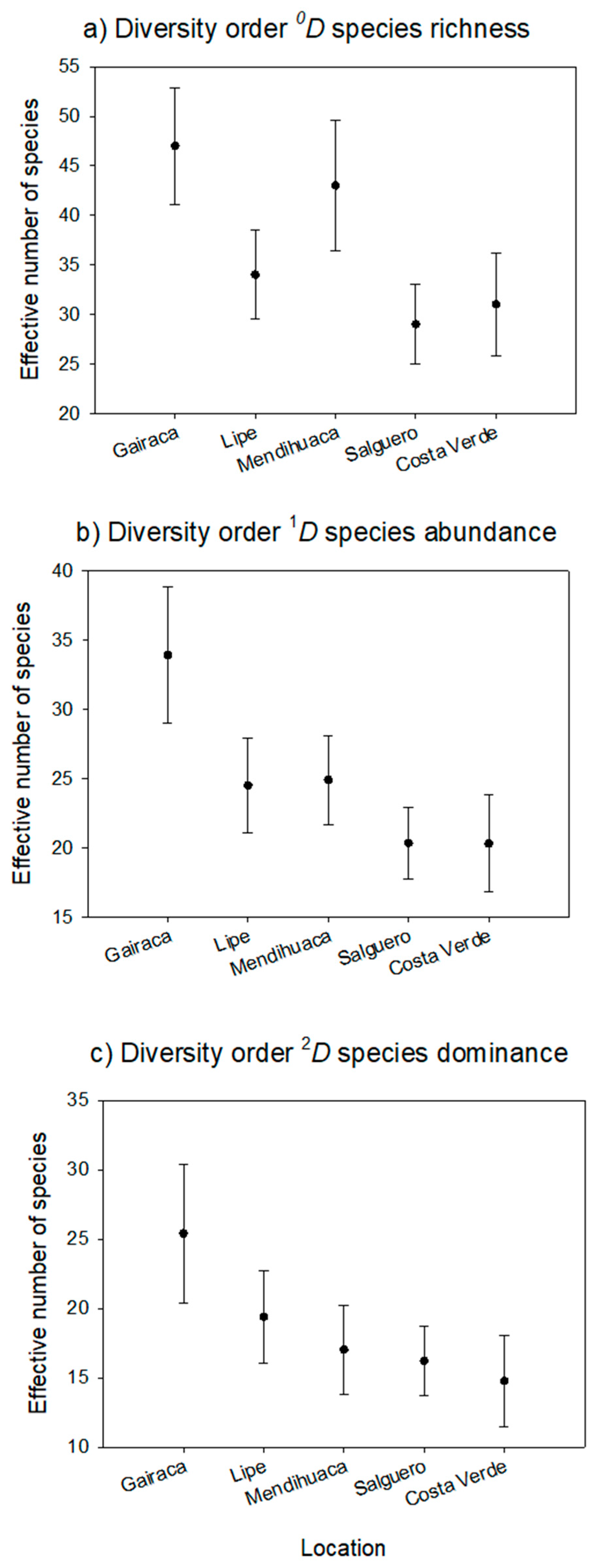

A completeness analysis was performed based on incidence, obtaining values of ≥ 93% for Lipe, ≥ 89% for Gairaca, ≥ 93% for Mendihuaca, ≥ 90% for Salguero, and ≥ 96 % for Costa Verde. A total of 133 species richness scores were recorded at the five sites, with 47 species at Gairaca, 44 at Mendihuaca, 34 at Lipe, 31 at Costa Verde, and 29 at Salguero.

Analyses performed with 95% confidence intervals (CI) showed significant differences for the diversity orders (

0D, 1D,

2D) between the beaches studied. Species richness (

0D) was similar between Gairaca and Mendihuaca and significantly higher in these sites compared with the others three (

Figure 4). For the

1D order, Gairaca showed significantly higher values than the rest, which indicated greater evennes. Finally, for the

2D order, the true diversity values gradually decreased from the most preserved site, Gairaca (with thelowest dominance), to the least, Costa Verde (

Figure 4).

The total Jaccard dissimilarity (b

jac) among sites was generally high (>0.80) (

Table 1), indicating marked heterogeneity in species composition. The highest dissimilarity was observed between Gairaca (the most preserved site) and the disturbed sites (Mendihuaca, Salguero, and Costa Verde) (

Table 1). However, Mendihuaca showed the highest dissimilarity values compared to the other sites, confirming it as the most distinct beach in terms of biological composition. The most disturbed site, Costa Verde, showed high dissimilarity with the other locations. In brief, floristic dissimilarity increased with disturbance intensity.

In contrast with species turnover, nestedness (b

jne) showed low values (<0.05), indicating that variation in species richness contributed little to the observed differences. Slight nestedness contributions were recorded only between Gairaca and Salguero, albeit at minimal levels. Overall, these results demonstrate that community divergence among beaches is primarily driven by turnover rather than by net gains or losses of species, with Mendihuaca standing out as ecologically unique compared to the other sites (

Table 1).

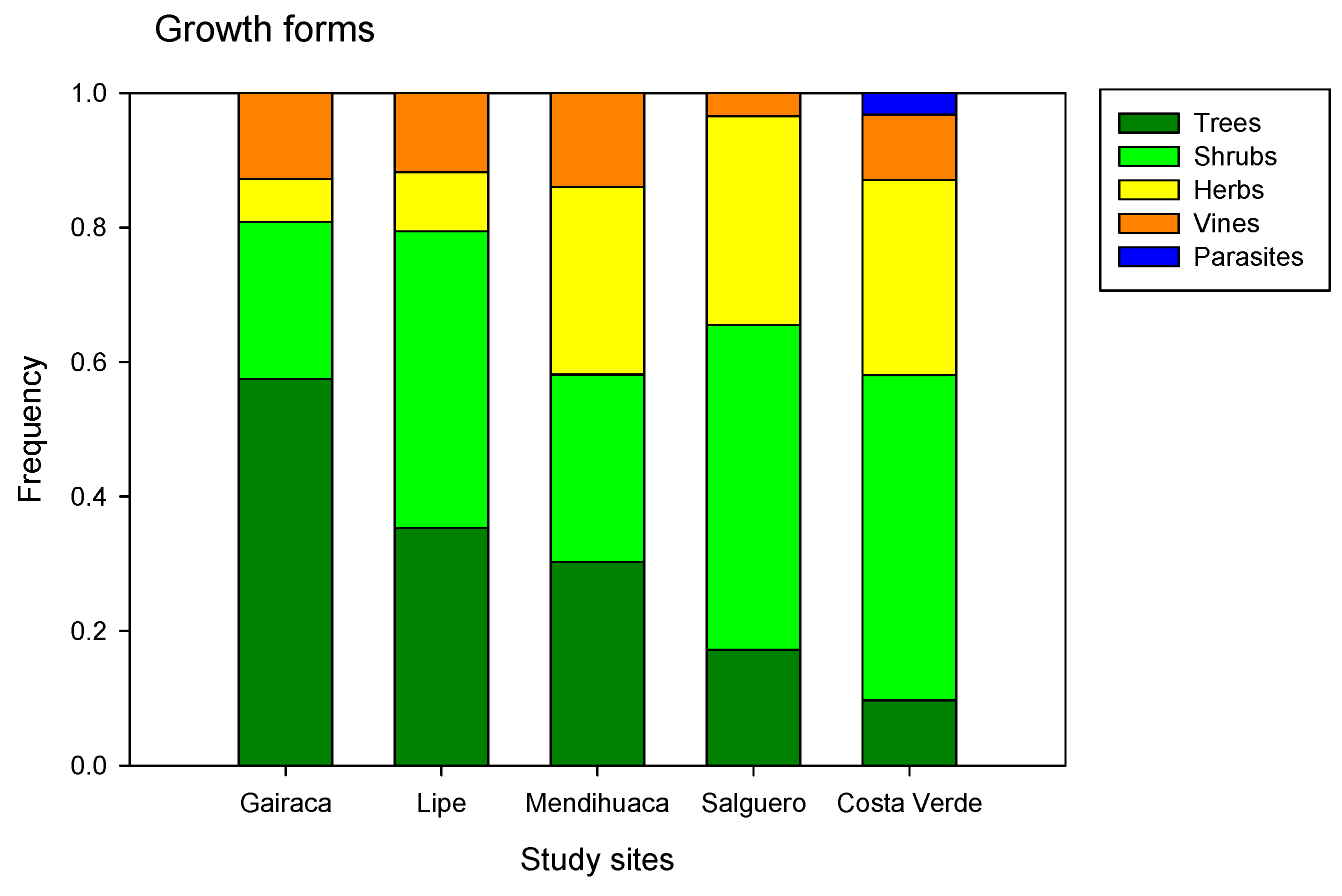

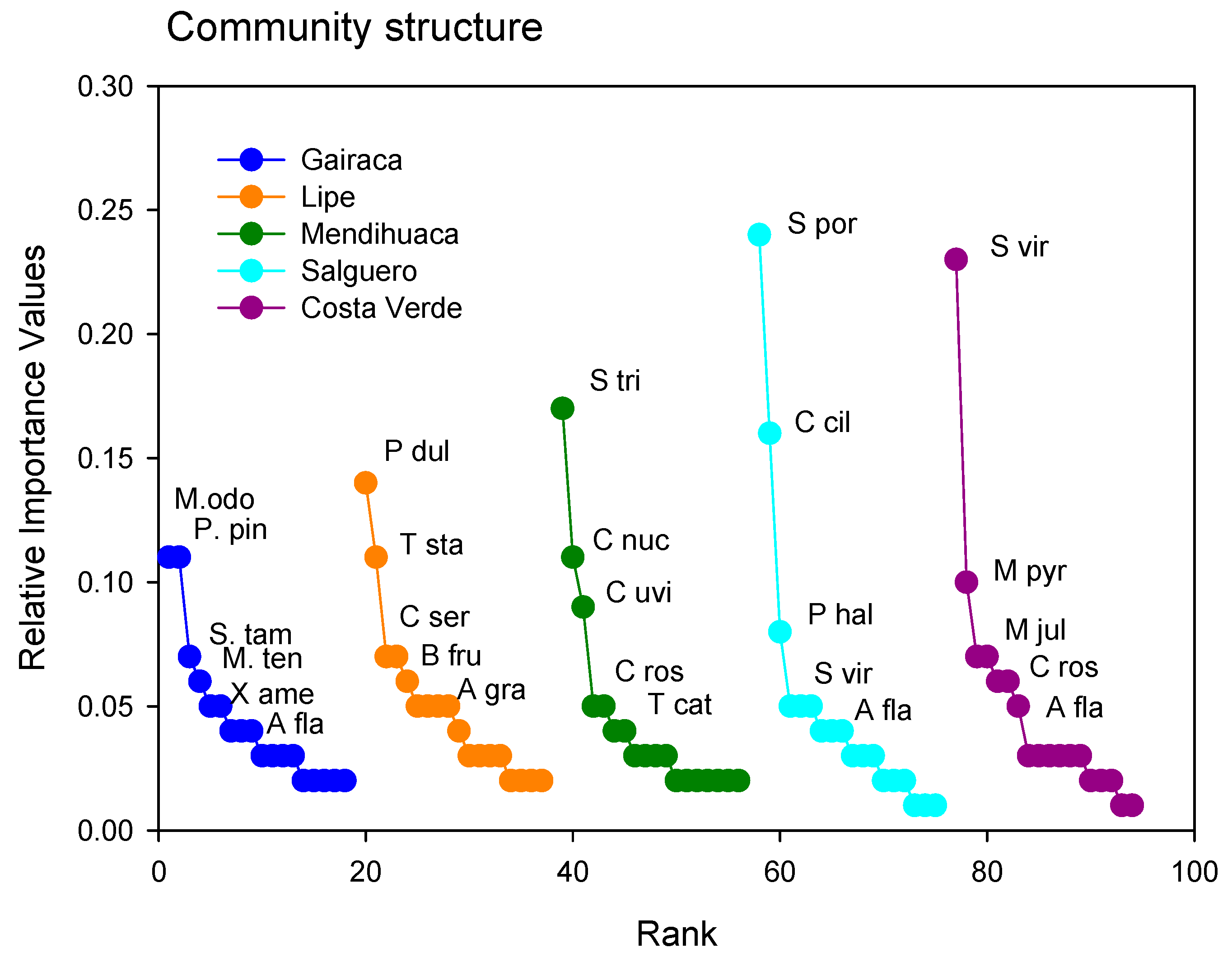

2.5. Community Structure

Trees and shrubs were more abundant in the best-preserved locations, while grasses were predominant in the most disturbed ones (

Figure 5). Thus, in Gairaca, located within a national park, trees such as

Morisonia odoratissima and

M. tenuisiliqua (Capparaceae),

Platymiscium pinnatum and

Senegalia tamarindifolia (Fabaceae), and

Ximenia americana (Olacaceae) were abundant. Other trees were found on Lipe beach,

Pithecellobium dulce (Fabaceae),

Astronium graveolens (Anacardiaceae),

Bonellia frutescens (Primulaceae),

Tecoma stans (Bignoniaceae), and

Guaiacum officinale. In turn, perennial herbs (

Sesuvium portulacastrum - Aizoaceae and

Sporobolus virginicus - Poaceae) were abundant on the most disturbed beaches, Salguero and Costa Verde.

The highest relative frequency of tree plants, occurring in Gairaca (60%), indicates a more mature and well-preserved vegetation formation compared to the other beaches. Lipe (35%) and Mendihuaca (30%) had lower proportions of trees, reflecting a mixture with other life forms, such as shrubs or herbaceous plants (

Figure 5). Finally, Salguero (18%) and Costa Verde (10%) have a very low proportion of trees, which could indicate an open vegetation cover dominated by herbaceous plants and shrubs in degraded areas. Costa Verde was the only location where parasitic plants were observed (

Figure 5).

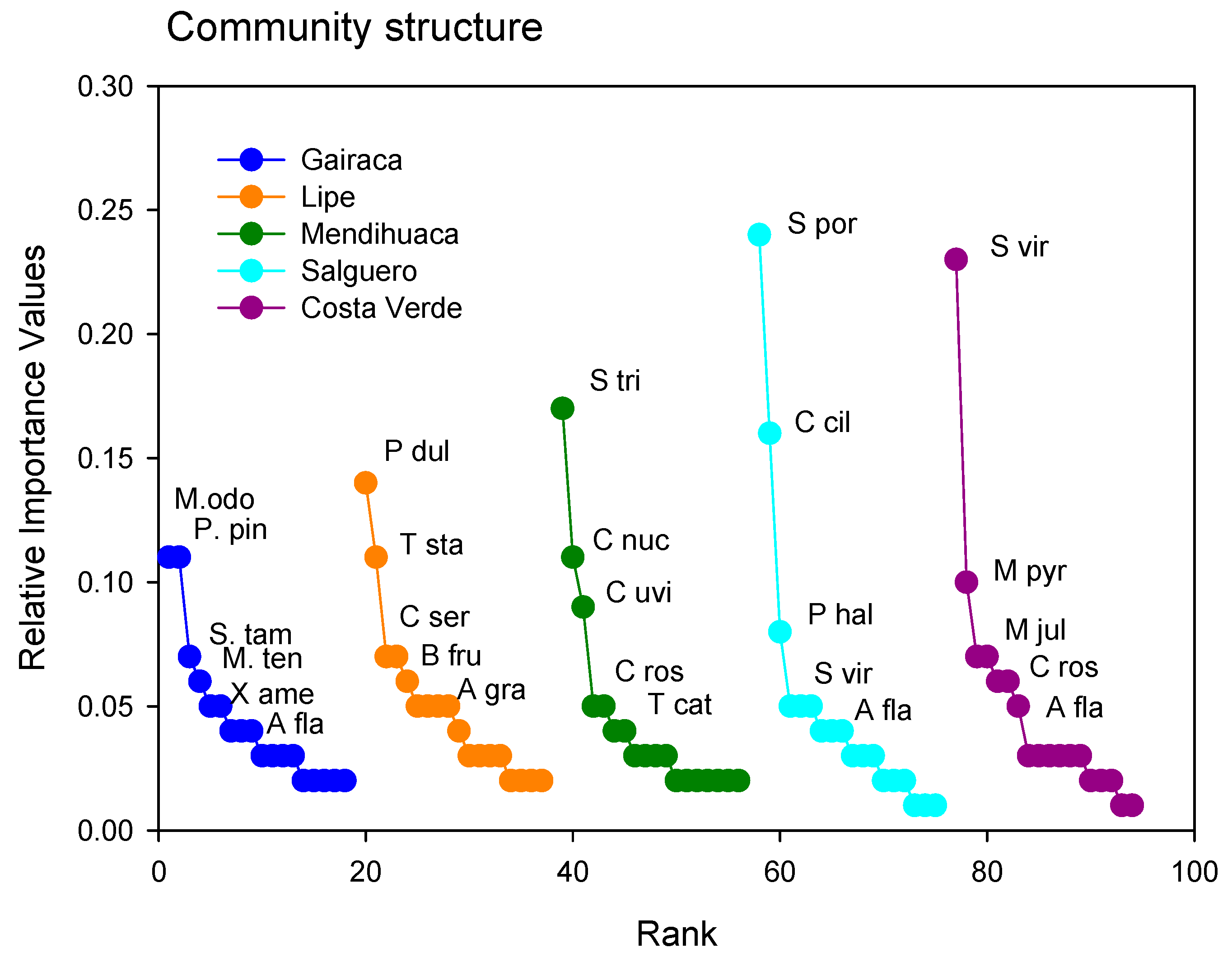

The Rank-Importance curves varied between sites (

Figure 6), and the important species changed notably, with only a few being widely represented. The curve for Gairaca is indicative of a more equitative community with trees such as

Morisonia odoratissima and

Platymiscium pinnatum being the dominant species. In contrast, herbs such as

Sesuvium portulacastrum and

Sporobolus virginicus were clearly dominant in Salguero and Costa Verde (

Figure 5), and the plant communities here were less equitative and dominated by one species.

Interestingly, the dominant species in one location were relatively scarce in other locations. For instance,

Sporobolus viginicus, the dominant species in Costa Verde, was very scarce on other sites. The same occurred for

Sesuvium portulacastrum, the dominant species in Salguero and very scarce elsewhere. Similar trends were observed in the other sites, where the dominant species were absent (

Figure 6).

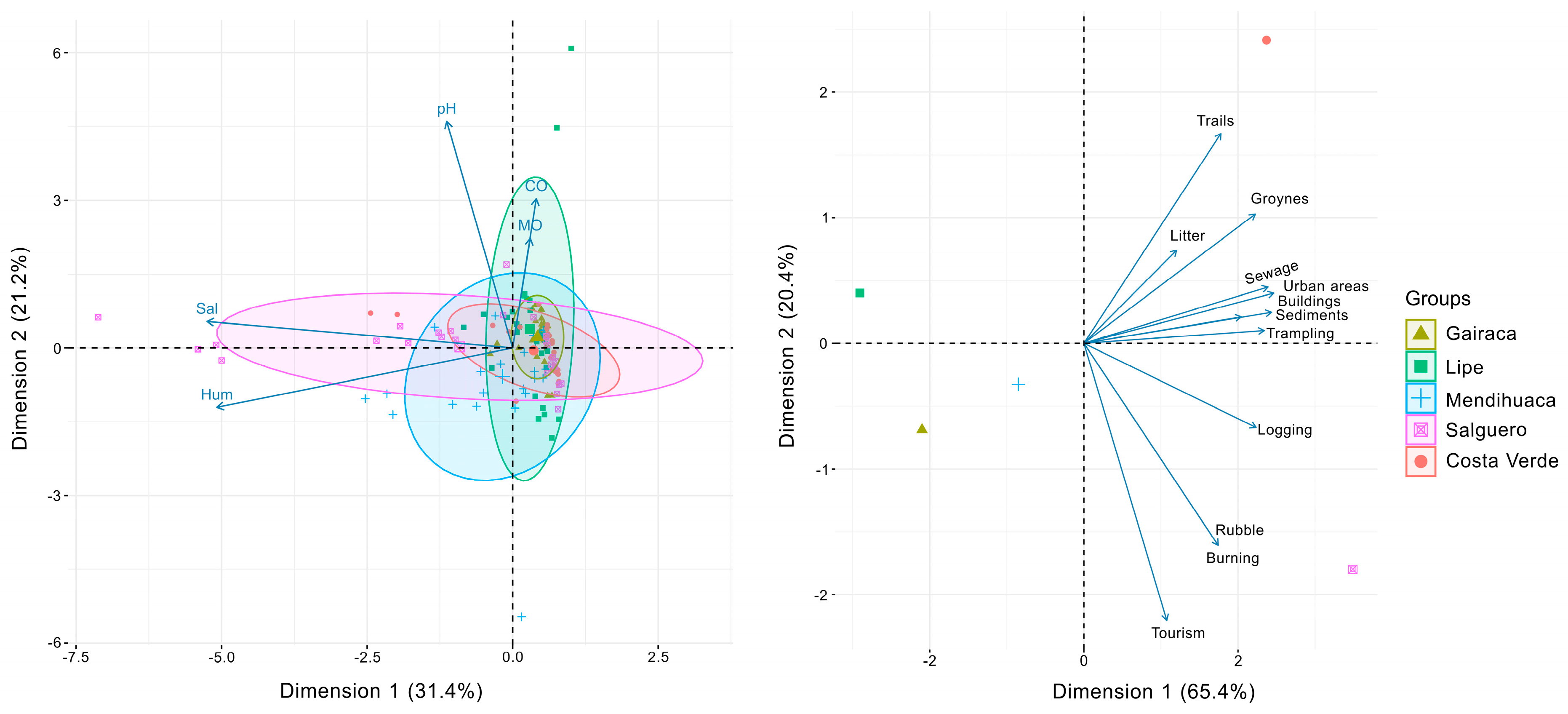

2.6. The Role of Environmental Variables in Plant Communities

The Canonical Correspondence Analysis shows the influence of the gradient of environmental variables —salinity, humidity, pH, organic matter (OM), and organic carbon (OC) —on the distribution of plant species among sites. Axis 1 and 2 explained 31.4% and 21.2%, respectively, accumulating 52.5% of the total variance of the environmental variables (

Figure 7). The variables pH, OM, and CO exhibited similar vector lengths. Salguero was correlated with pH, salinity and humidity. However, the floristic groups formed were not clearly distinguishable, indicating that, in general, the correlation between plant species and natural environmental sites was similar across sites.

In turn, the Canonical Correspondence analysis performed with anthropogenic variables clearly showed how they were most relevant in the most disturbed sites: Salguero and Costa Verde (

Figure 7). Axis 1 and 2 explained 65.4% and 20.4%, respectively, accounting for 85.8% of the total variance in the anthropogenic variables. In this case, the anthropogenic variables clearly showed differences between sites.

3. Discussion

This study shows that natural and anthropogenic factors varied between the study sites which were correlated with the composition and structure of the plant communities from the beach and coastal dunes along the Colombian Caribbean coast. Human disturbances (urbanized areas, construction, burning, debris, trampling, logging, tourism, groins, sewage, roads, garbage, and sediment extraction) were particularly relevant. The sites less affected by human activities showed higher plant cover and species diversity, a higher percentage of trees and vines, and a reduced dominance of species. In turn, the opposite occurred in the disturbed sites, characterized by lower plant cover and diversity, abundant shrubs and parasitic plants, and the dominance of a few herbaceous species. Management alternatives should consider the environmental factors affecting vegetation to improve the conservation of plant biodiversity in the coastal dunes along the Colombian Caribbean coast.

3.1. Environmental Factors: Natural and Anthropogenic

Natural characteristics and disturbances may limit the diversity and abundance of species, leaving only those that have the necessary adaptations to survive in the specific conditions of a site [

35,

36].

Among the observed natural factors that may be modulating biodiversity were geomorphological dune attributes (dune height and slope) and beach characteristics (beach width and width of the area covered by vegetation [

37]. The high plant cover of sandy dunes observed in Gairaca, Lipe, and Mendihuaca suggests that they are stabilized and help retain sand, preventing wind erosion and promoting the accumulation of more sediments.

Considering the environmental ocean-land gradient, saltwater flooding (salinity) in the zone closest to the sea limits plant growth, and only those adapted to saline environments remain. For instance, areas exposed to regular flooding in Mendihuaca promoted the dominance of species such as

S. trolibata, which is tolerant to salinity. Similar results were observed by Bernal et al. [

38], who highlighted the dominance of herbaceous plants such as

S. trilobata in association with higher contents of gravel and sand, low slopes, and seawater flooding.

S. trilobata grows in coastal dunes and structureless soils, with high salinity, temperatures, and direct exposure to solar radiation [

39,

40,

41].

High anthropogenic impacts were observed to coincide with previous studies, such as those by Pereira et al. [

30,

37,

42]. These authors mention urbanization and garbage problems [

43], the presence of invasive plants, such as

Calotropis procera and

Cryptostegia madagascariensis [

44], sand extraction, and an increase in human traffic [

37] in the disturbed sites.

In the most disturbed sites, Salguero and Costa Verde, burning, the construction of housing and infrastructure for tourism, and the installation of groins have resulted in habitat loss and alteration of the natural landscape [

45,

46]. These beaches are also affected by trampling, roads, and excessive logging, which negatively affect germination, reproduction, survival, species richness, cover, and diversity [

45,

47,

48]. In general, human disturbances promoted the invasibility of coastal vegetation by facilitating the colonization of new propagules of exotic plant species, resulting in the loss of native species [

44,

49] such as

Calotropis procera and

Tribulus cistoides. Additionally,

Cenchrus ciliaris, Chloris barbata, Tephrosia purpuria, Cocos nucifera, and

Azadirachta indica are also negatively affected by human disturbances.

3.2. Floristic Composition and Community Structure

A total of 133 species, included in 112 genera and 53 families, were identified on the beach coastal dunes of the northern Colombian Caribbean. These results improve previous findings in the area, which have reported a maximum of 70 species and 38 families [

50]. The dominance of the Fabaceae (26 species) aligns with the findings of Pinilla & Zuluaga [

51] and Rangel et al. [

30].

The dominant families coincide with the findings in other beaches and coastal dunes. For example, studies in the Venezuelan Caribbean highlight the diversification of families present in beaches and dunes: Poaceae (15), Cyperaceae (11), Fabaceae (8), Euphorbiaceae (5), Boraginaceae (5), Malvaceae (5), and Asteraceae (4), among others, for a total of 97 species with 73 genera included in 34 families [

20]. A high biodiversity from Mexican coastal dunes [

52] reports 153 families, included in 897 genera, and 2,075 species. Again, Fabaceae and Poaceae were the most abundant families with the greatest number of species. Plan diversity in the Brazilian Catinga is lower than in the above-mentioned studies, with 86 species in 37 families. Once more, the Fabaceae family (24 species) was considered the most important due to its richness [

53]. In all cases, a reduced percentage of plant species is considered typical of the beach and coastal dunes environments. The plant cover of stabilized dunes contains species from surrounding vegetation types, including tropical forests, scrublands, mangroves, and freshwater wetlands [

52], thus contributing to the biodiversity of the study sites.

Two species are worth mentioning. Among the Poaceae, the most common dune-forming species was

Sporobolus virginicus, dominant in Salguero and Costa Verde, the two the most disturbed beaches. Espejel et al. [

52] indicate that

Sporobolus virginicus is the most common grass on beaches and embryo dunes, occupying large areas. This grass tolerates salinity and sand movement [

33], which explains its occurrence along the transects, especially close to the ocean. In addition to

Sporobolus virginicus, clumps of

Cenchrus ciliaris, a species native to Colombia, are frequently found; in short, these grasses are more common in disturbed environments.

In addition to

S. virginicus,

Morisonia (Capparaceae) was the most representative genus with seven species. This genus was recorded on preserved beaches such as Gairaca and Lipe, with 6 and 2 species respectively, denoting

Morisonia odoratissima as a common species among these and absent on the remaining beaches. The abundance of trees and shrubs in the preserved sites (Gairaca and Lipe) coincides with previous studies [

53] on beaches of San Bernardo Island, where more than half of all sampled species were woody. On the other hand, Rangel [

30] and Gomez et al. [

33] recorded the herbaceous growth habit as the most important in their study, similar to the results observed on beaches with high anthropogenic disturbances.

In line with the results on species richness, biodiversity was highest in the preserved sites (Gairaca and Lipe) compared to those with more intense anthropogenic activity (Salguero and Costa Verde). This finding aligns with the study by Rangel Buitrago [

30], which showed a reduced biodiversity due to anthropogenic impact. It is interesting to note that Mendihuaca, the moderately disturbed site, had the highest biodiversity. This finding was probably the result of a combination of species typical of preserved sites coexisting with species from moderately perturbed locations, which follows Connell's [

54] intermediate disturbance hypothesis and coincides with the study by Pinna et al [

55].

3.3. Management Alternatives

Effective management of the beach and coastal dunes along the coastline of Magdalena needs several approaches. Locally, due to intensive tourism activities, it is necessary to estimate and monitor the carrying capacity of each beach [

56,

57,

58]. Also, regulating trampling through the use of boardwalks, designated access points, and restricted areas is necessary for the recovery of natural vegetation [

59].

In a broader territorial scale, there are several regulations concerning beach setbacks for construction on consolidated land, which may vary according to beach dynamics. Nonetheless, along the coastline of Magdalena, many buildings are close to the high tide line. This results in the disruption of coastal dynamics and exacerbates erosion processes, thereby generating both ecological and economic risks. In the Colombian Caribbean, coastal erosion issues affecting these constructions and settlements in high-risk areas have been documented, with mitigation relying primarily on hard-engineering solutions. These interventions often lead to severe impacts, highlighting the need for preventive approaches and soft-engineering alternatives [

5,

43,

60].

The establishment of clear state policies is essential to delimit and ensure the protection of natural protected areas within these ecosystems. Such policies could be aligned with international certifications such as the Blue Flag and hotel sustainability labels. Furthermore, in degraded areas, programs of ecological restoration with native species, invasive species control, and the promotion of ecotourism are necessary. Regulatory strategies for resource extraction and effective waste management are also required to safeguard the integrity of coastal ecosystems, since waste accumulation undermines scenic and recreational value and threatens dune system regeneration and stability [

43]. Finally, awareness-raising initiatives that foster the social appropriation of these ecosystems, along with participatory environmental monitoring, are necessary to alleviate pressures and ensure the maintenance of the ecosystem services provided by dunes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Sites

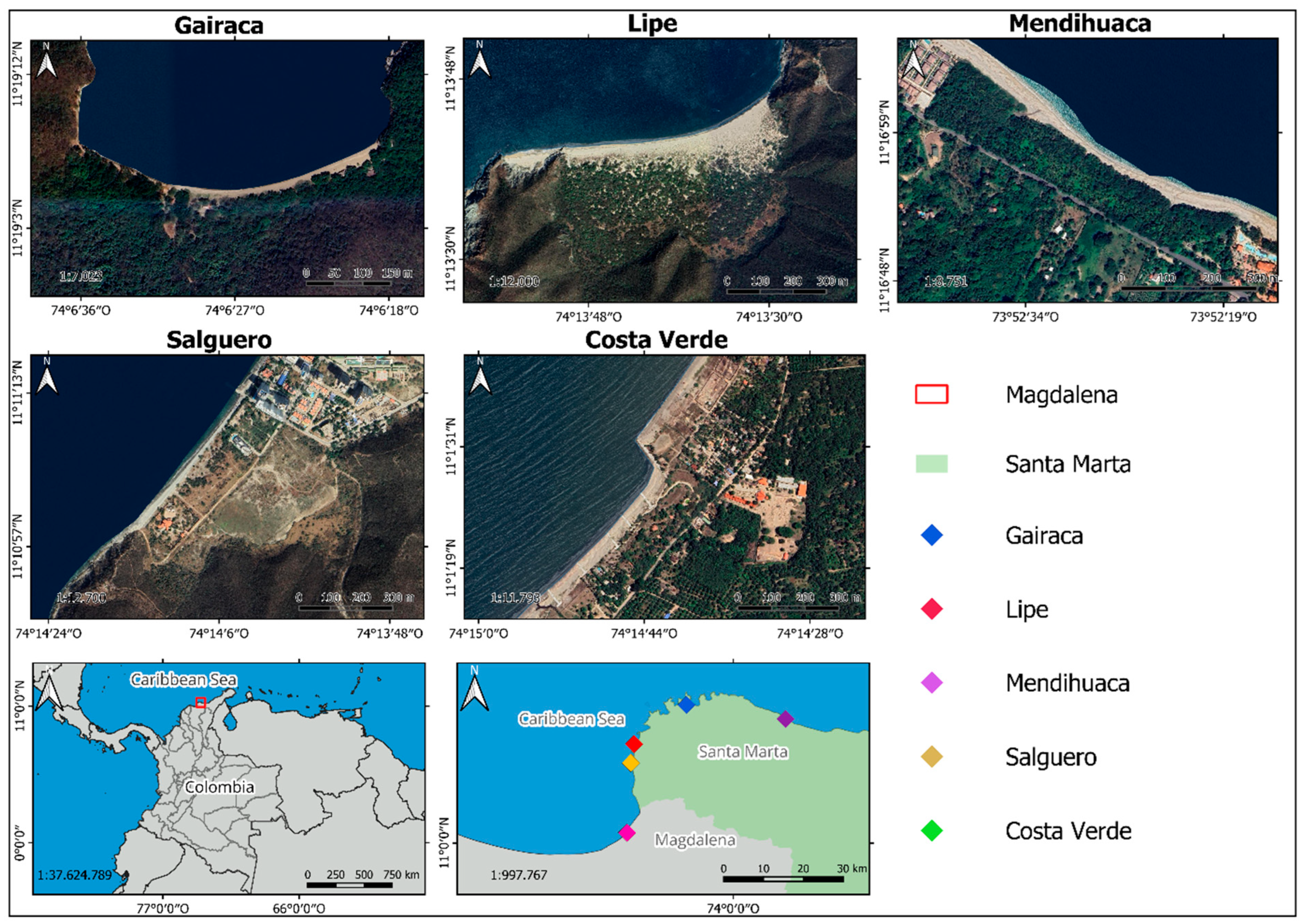

The study area included coastal dunes from five beaches: Gairaca (Tayrona National Natural Park), Lipe, Mendihuaca, Salguero, and Costa Verde in the department of Magdalena, in the Colombian Caribbean (

Figure 8,

Table 2). Five sites were selected along the coastline with different degrees of anthropogenic and natural stressors: a) Gairaca (moderately visited beach within a National Natural Park; b) Lipe (beach exposed to natural events and protected by its geomorphological conditions; c) Mendihuaca (beach moderately visited by tourists; d) Salguero (highly visited by tourists) and e) Costa Verde (with unplanned urban and tourism expansion and crops).

The climate in the coastal zone is warm and dry, with an average annual temperature of 28°C, a minimum of 25°C, and a maximum of 34°C. The mean annual rainfall varies between 362 and 500 mm [

61]. The climate is determined by the influence of the coastal mountain range Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (5900 m), the trade winds, and ocean currents [

62,

63]. The precipitation regime is defined by the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), resulting in a bimodal pattern with two rainy periods: April to June and August to November, alternating with two dry seasons: December to March and June to August. However, below 200 meters above sea level, the system is monomodal; the north face presents a tropical climate with precipitation between July and November and a single well-marked dry period between December and June. In contrast, the coastal area of the northwestern face is characterized by four distinctive periods: major dry (December-April), minor rainy (May-June), minor dry (July-August), and major rainy (September-November) [

64]. Consequently, the north face is the wettest (Mendihuaca and Gairaca), the eastern face is the driest (towards the interior of the continent), and the northwestern face shows an intermediate condition (Lipe, Salguero, and Costa Verde beaches).

4.2. Environmental Variables: Natural and Anthropogenic

The environmental variables used in this study included topography (dune height, slope), beach width, vegetation width, and plant cover. Dune topography was measured starting at a point of known height (x = 0 and y = 0). Then we used a laboratory-made inclinometer following the same methods as Maximiliano-Cordova et al. [

21] to measure vertical distances. The instrument allowed measuring changes in topography between two points established at distances of 0.5 or 1 m, depending on the topography.

For each site, three profiles were measured from the dunes towards the ocean and in each one, we estimated the maximum height (m) of the frontal dune through the vertical distance from sea level to the dune crest. Using the x, y coordinates, the slope of the dune along each profile was calculated as the slope of the straight line (Equation 8) and then expressed as a percent change (Equation 1).

where x

1 and y

1 correspond to the coordinates of the first point of the segment (initial distance and height), and x

2 and y

2 represent the coordinates of the second point (final distance and height) of the segment, and thus, the inclination was calculated.

Other environmental variables measured in the field included the width of the beach (measured with a measuring tape), from the highest water mark to the beginning of the foredune. Tides in Colombia are very narrow with no significant changes throughout the day. We also measured the width of the space covered with vegetation and the mean plant cover per plot.

In addition, sedimentological variables were assessed. Three sediment samples were collected in each plot from three subsamples from the top 15 cm of soil to obtain a total of 400 g [

65,

66]. In each sample, we measured pH of the sand, moisture, salinity, organic matter, and carbon [

67]

.

Twelve anthropogenic variables were used: 1) tourism, 2) logging, 3) trampling, 4) burning, 5) sediment extraction, 6) garbage, 7) debris, 8) constructions, 9) roads, 10) sewage, 11) spurs, and 12) urban areas. We used ordinal values for each variable, which varied from 1 to 4. The ordinal scale of presence/intensity was used as follows: 1 indicates the absence of the variable at the site, while values from 2 to 4 indicate the presence of the anthropogenic effect, with the scale value increasing as the intensity increases. The dataset was analyzed using the mirt package in RStudio, applying a modified item–person map (also known as an un-Wright map) to visualize the relative intensity and distribution of the different anthropogenic factors among sites [

68].

4.3. Vegetation Sampling

At each site, three transects of different lengths were carried out perpendicular to the coastline until there was a change in the morphology of the terrain and vegetation. In each of the transects, nine plots of 2 x 2 m were set, interspersed on the right and left, for a total of 27 to 54 plots per site. The organization of the sampling numbering was carried out considering the plot closest to the sea as number 1, and plot 9 as the most distant [

15,

65]. Species richness and plant cover per species was visually estimated in each plot.

Plant samples were collected from each plot, pressed, and herbarized [

69]. The collection of biological material was deposited at the Center for Biological Collections (CBUMAG) of the University of Magdalena. The floristic composition was determined using specialized morphological taxonomic keys for the different groups. The identifications were corroborated using reference virtual herbaria such as the Colombian National Herbarium (COL) (

http://www.biovirtual.unal.edu.co), the New York Botanical Garden (NY), and Tropicos (

http://www.tropicos.org), along with consultation with specialist herbaria and visits to the COL herbarium to clarify difficult identifications. The scientific names and growth habits were updated with POWO (

https://powo.science.kew.org/) and The WFO Plant List (

https://wfoplantlist.org/).

4.4. Data Analyses

First, alpha diversity was determined for each site using the effective number of species [

70] according to the Hill series [

71], from the

qD notation (Equation 2) with R Studio.

where

qD is the community diversity according to the selected index,

q exponent and superscript is the "order of diversity",

pi is the relative abundance (proportional abundance) of the ith species, and

S is the number of species. In this case,

q = 0 (

0D) represents true species richness,

q =1 (

1D) represents common species (Shannon diversity), and

q = 2 (

2D) represents dominant species (Simpson diversity) [

70]. Comparisons of diversity values were performed through coefficient intervals (CI) overlapping at 95 % [

72]. Analyses were performed with the iNEXT library [

73] in R Studio (R version 3.6.1 "Action of the Toes") [

74].

Second, beta diversity was calculated based on the dissimilarity between sites by computing Jaccard’s dissimilarity index (βjac) (Equation 3). The two partitioning components were considered: species turnover (b

jtu) and species nestedness (b

jne) [

75] to better interpret biodiversity patterns [

75,

76].

where: a is the number of species shared across both sites, b is the number of species found at the first site but not at the second, and c is the number of species found at the second site but not at the first [

76]. The index takes values on a scale between 0 (zero dissimilarity) and 1 (complete dissimilarity) [

76]. Analyses were performed using the betapart package [

76] in R Studio version 4.4.1.

Third, the species importance value index (IVI) was estimated per site,

IVI = [(Fr+Cr)/2], where the relative frequency (

Fr) is defined as the number of plots where the species appears, and the relative cover (

Cr) is the plant cover per species divided by the total plant cover. The cover of each species, estimated as a percentage within each plot, was converted into square meters for the IVI calculation. The relative cover was considered as the total cover of the species in the plots where it was present, divided by the total cover of all species in the plots [

77]. The IVI obtained a maximum value of 1 to facilitate interpretation [

77,

78].

Finally, a Canonical Correspondence Analysis was performed to explore the correlation between the different environmental variables (natural and anthropogenic) with plant communities in terms of species composition. The Vegan R library was used to conduct this analysis [

79].

5. Conclusions

Natural and anthropogenic factors varied between the study sites and were correlated with the composition and structure of the plant communities from the beach and coastal dunes along the Colombian Caribbean coast. Specifically, human activities such as urban expansion, infrastructure development, trampling, logging, burning, road construction, and tourism represented the main drivers affecting the coastal dune vegetation. In Salguero and Costa Verde, these pressures have led to a marked reduction in vegetation cover, species richness, and diversity. In contrast, sites such as Gairaca and Lipe exhibit better conservation status, associated with lower levels of human disturbance, greater vegetation cover, and a higher abundance of arboreal species. Overall, the best-preserved sites are linked to more stable geomorphological conditions, particularly greater dune height and vegetation cover.

In Salguero and Costa Verde, high-intensity anthropogenic pressures demand the implementation of integrated coastal management plans. These should include establishing setbacks to restrict new construction within the beach strip and developing clear governmental policies to delineate and safeguard conservation areas. Such strategies could be aligned with national and international hotel sustainability certification schemes. Furthermore, ecological restoration programs should be prioritized in degraded sectors, emphasizing the reintroduction of native species, control of invasive plants, and recovery of ecological functions. Complementary measures include promoting ecotourism, regulating pedestrian mobility through elevated walkways to minimize trampling, and implementing solid waste management and resource extraction control protocols. Additionally, community-based environmental education programs and participatory monitoring schemes are required to reduce anthropogenic pressures and ensure the long-term provision of dune ecosystem services.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LMO; methodology, MAN; software, ARV; formal analysis, CMC; data curation, ARV; writing—original draft preparation and supervision, LMO and MAN; review and editing, MLM and OPM; visualization, CMC, ARV, MLM; supervision, MLM; project administration, LMO; funding acquisition, MAN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following projects: a) "Characterization of halophytic plant communities with adaptive traits for their potential use in beach and dune restoration against coastal erosion in the department of Magdalena, Minciencias, Proposals of the Science, Technology and Innovation Fund of the General Royalties System and approved by the OCAD; b) "Functional features of vegetation and its relationship with sedimentological variables of coastal dunes" VIN 2022157, and c) "Characterization of the vegetation cover of the beaches of the Department of Magdalena" VIN2023187, both with financial support of Vicerrectoría de Investigación de la Universidad del Magdalena;

Data Availability Statement

The collected plant material was deposited in the Scientific Collections Center of the Universidad del Magdalena (CBUMAG). Each specimen was taxonomically identified and labeled, with detailed collection data including georeferencing, date, and habitat description. Guaiacum officinale, an endangered species, was photographically documented. All specimens are available for public consultation. The collection was conducted within the framework of the project “Functional traits of vegetation and their relationship with environmental and geomorphological variables.” Specimens are registered in the Biodiversity Information System (SIB). The data used in this article can be made available upon request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

MIKU Research Group on Management and Conservation of Neotropical Fauna, Flora and Strategic Ecosystems, INECOL, the PhD in Marine Sciences, and for technical support to Nain Gonzalez, Sandra Estrada, Aldair Castrillo, Karina Herrera, Adriana Comas, Lineth Cantillo, Gabriela Pérez, Jhuliet Martínez, Ana Isabel Miranda, Sebastián González, Luis De Luque, and Alberto Manco.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Species identified on the beach coastal dunes of the northern Colombian Caribbean. Study sites are listed from most to least preserved: G = Gairaca, L = Lipe, M = Mendihuaca, S = Salguero, and CV = Costa Verde.

Table A1.

Species identified on the beach coastal dunes of the northern Colombian Caribbean. Study sites are listed from most to least preserved: G = Gairaca, L = Lipe, M = Mendihuaca, S = Salguero, and CV = Costa Verde.

| Family |

Species |

G |

L |

M |

S |

CV |

| Fabaceae |

Alysicarpus vaginalis (L.) DC. |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Canavalia rosea (Sw.) DC. |

x |

|

x |

|

x |

|

Chamaecrista serpens (L.) |

|

x |

|

x |

|

|

Coulteria mollis Kunth |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Coursetia caribaea (Jacq.) Lavin |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Dalbergia brownei (Jacq.) Schinz |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Desmodium sp |

|

|

x |

|

x |

|

Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Guilandina bonduc L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Leucaena trichodes (Jacq.) Benth. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Libidibia punctata (Willd.) Britton |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Mimosa arenosa (Willd.) Poir. |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

Muellera sanctae-marthae (Pittier) M.J.Silva & A.M.G. Azevedo |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Neltuma juliflora (Sw.) Raf. |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Neptunia plena (L.) Benth. |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Platymiscium pinnatum (Jacq.) Dugand |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

Pterocarpus officinalis Jacq. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Senegalia tamarindifolia (L.) Britton & Rose |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Senna atomaria (L.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Sesbania sesban (L.) Merr. |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Stylosanthes humilis Kunth |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Tephrosia cinerea (L.) Pers. |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers. |

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

Vachellia tortuosa (L.) Seigler & Ebinger |

|

x |

|

x |

|

|

Vigna marina (Burm.) Merr. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Poaceae |

Cenchrus ciliaris L. |

|

x |

|

x |

|

|

Cenchrus pilosus Kunth |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Chloris barbata Sw. |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Chloris virgata Sw. |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Coix lacryma-jobi L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Eleusine tristachya (Lam.) Lam. |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Eragrostis sp |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Panicum sp |

x |

|

x |

|

|

|

Sporobolus virginicus (L.) Kunth |

x |

|

|

x |

x |

| Malvaceae |

Corchorus aestuans L. |

|

|

x |

|

x |

|

Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. |

x |

|

x |

|

|

|

Malvastrum coromandelianum (L.) Garcke |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Melochia crenata Vahl |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Melochia pyramidata L. |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Melochia tomentosa L. |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Pseudabutilon umbellatum (L.) Fryxell |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Waltheria indica L. |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Cnidoscolus urens (L.) Janti |

|

x |

|

x |

|

|

Croton ovalifolius Vahl |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Euphorbia hirta L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Euphorbia hyssopifolia L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Jatropha gossypiifolia L. |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Manihot carthagenensis (Jacq.) Müll.Arg. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Sapium glandulosum (L.) Morong |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Capparaceae |

Morisonia americana L. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Morisonia indica (L.) ined. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Morisonia linearis (Jacq.) Christenh. & Byng |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Morisonia odoratissima (Jacq.) Christenh. & Byng |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

Morisonia pachaca (Kunth) Christenh. & Byng |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Morisonia tenuisiliqua (Jacq.) Christenh. & Byng |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Morisonia verrucosa (Jacq.) Christenh. & Byng |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Cactaceae |

Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Hummelinck |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Leuenbergeria guamacho (F.A.C.Weber) Lodé |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Opuntia caracassana Salm-Dyck |

|

x |

|

x |

|

|

Pilosocereus lanuginosus (L.) Byles & G.D.Rowley |

|

x |

|

x |

|

|

Stenocereus griseus (Haw.) Buxb. |

|

x |

|

x |

|

| Polygonaceae |

Coccolaba acuminata Kunth |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Coccoloba obtusifolia Jacq. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Coccoloba uvifera (L.) L. |

|

|

x |

|

x |

|

Enneatypus ramiflorus (Jacq.) Roberty & Vautier. |

|

x |

|

|

|

| Rubiaceae |

Morinda royoc L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Oldenlandia corymbosa L. |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Spermacoce exilis (L.O.Williams) C.D.Adams ex |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Spermacoce latifolia Aubl. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Bignoniaceae |

Crescentia cujete L. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Handroanthus billbergii (Bureau & K.Schum.) S.O.Grose |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth |

|

x |

|

|

|

| Convolvulaceae |

Ipomoea incarnata (Vahl) Choisy |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Ipomoea carnea Jacq. |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Ipomoea pes-caprae (L.) R.Br. |

x |

|

x |

|

x |

| Cyperaceae |

Cyperus sp1 |

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Cyperus sp2 |

|

|

x |

|

x |

|

Fimbristylis sp |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Apocynaceae |

Calotropis procera (Aiton) W.T.Aiton |

|

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Ibatia maritima (Jacq.) Decne. |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

| Asteraceae |

Sphagneticola trilobata (L.) Pruski |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Trixis inula Crantz |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Boraginaceae |

Cordia dentata Poir. |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Varronia bullata L. |

|

|

|

x |

|

| Burseraceae |

Bursera graveolens (Kunth) Triana & Planch. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Bursera simaouruba (L.) Sarg. |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Erythroxylaceae |

Erythroxylum carthagenense Jacq. |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

Erythroxylum hondense Kunth |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Moraceae |

Ficus insipida Willd. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Maclura tinctoria (L.) D.Don ex G.Don |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Portulacaceae |

Portulaca halimoides L. |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Portulaca pilosa L. |

|

x |

|

|

|

| Verbenaceae |

Lantana camara L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

Phyla nodiflora (L.) Greene |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Zygophyllaceae |

Guaiacum officinale L. |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Tribulus cistoides L. |

|

x |

|

x |

x |

| Acanthaceae |

Ruellia blechum L. |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Aizoaceae |

Sesuvium portulacastrum (L.) L. |

|

|

|

x |

x |

| Amaranthaceae |

Alternanthera flavescens Kunth |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

| Amaryllidaceae |

Hymenocallis littoralis (Jacq.) Salisb. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Anacardiacee |

Astronium graveolens Jacq. |

x |

x |

|

|

|

| Arecaceae |

Cocos nucifera L. |

|

|

x |

|

x |

| Chrysobalanaceae |

Parinari pachyphylla Salm-Dyck |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Combretaceae |

Terminalia catappa L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Commelinaceae |

Commelina sp |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Cucurbitaceae |

Momordica charantia L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Hernandiaceae |

Gyrocarpus americanus Jacq. |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Linderniaceae |

Lindernia dubia (L.) Pennell |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Loganiaceae |

Spigelia anthelmia L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Loranthaceae |

Passovia pedunculata (Jacq.) Kuijt |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Meliaceae |

Azadirachta indica A.Juss. |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Molluginaceae |

Mollugo verticillata L. |

|

|

x |

x |

|

| Monimiaceae |

Mollinedia ovata Ruiz & Pav. |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Muntingiaceae |

Muntingia calabura L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Musaceae |

Musa acuminata Colla |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Myrtaceae |

Psidium guajava L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Nyctaginaceae |

Commicarpus scandens (L.) Standl. |

|

x |

|

|

|

| Olacaceae |

Ximenia americana L. |

x |

x |

|

|

|

| Passifloraceae |

Passiflora foetida L. |

|

|

|

|

x |

| Petiveriaceae |

Petiveria alliacea L. |

x |

|

|

|

|

| Phyllanthaceae |

Phyllanthus urinaria L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Piperaceae |

Piper bredemeyeri J.Jacq. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Primulaceae |

Bonellia frutescens (Mill.) B.Ståhl & Källersjö |

|

x |

|

x |

|

| Sapindaceae |

Cardiospermum halicacabum L. |

x |

x |

|

|

|

| Sapotaceae |

Sideroxylon obtusifolium (Roem. & Schult.) T.D.Penn. |

x |

|

|

x |

|

| Schizaeaceae |

Lygodium venustum Sw. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Solanaceae |

Solanum incanum L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Talinaceae |

Talinum fruticosum (L.) Juss. |

|

|

|

x |

|

| Tetrachondraceae |

Polypremum procumbens L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Urticaceae |

Cecropia peltata L. |

|

|

x |

|

|

| Vitaceae |

Cissus trifoliata (L.) L. |

|

x |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Silva, R.; Martínez, M.; Moreno, P.; Mendoza, E.; López, J.; Lithgow, D.; Vázquez, G.; Martínez, R.; Monroy, R.; Cáceres, J. Aspectos Generales de La Zona Costera; UNAM; INECOL: Coatepec, Mexico, 2017; pp. 54.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis, Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2005; pp. 137.

- Everard, M.; Jones, L.; Watts, B. Have We Neglected the Societal Importance of Sand Dunes? An Ecosystem Services Perspective. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2010, 20, 476–487. [CrossRef]

- Schlacher, T.A.; De Jager, R.; Nielsen, T. Vegetation and Ghost Crabs in Coastal Dunes as Indicators of Putative Stressors from Tourism. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 284–294. [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.G.; Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T. Coastal Erosion along the Caribbean Coast of Colombia: Magnitudes, Causes and Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 114, 129–144. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Pranzini, E.; Anfuso, G. The Management of Coastal Erosion. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 156, 4–20. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Casasola, P. Entornos veracruzanos: la costa de La Mancha; INECOL: Xalapa/Veracruz, Mexico, 2006; pp. 576.

- Pedroza, D.; Cid, A.; García, O.; Silva-Casarín, R.; Villatoro, M.; Delgadillo, M.; Mendoza, E.; Espejel, I.; Moreno-Casasola, P.; Martínez, M.L. Manejo de Ecosistemas de Dunas Costeras, Criterios Ecológicos y Estrategias. Secr. Medio Ambiente Recur. Nat. México DF México 2013.

- Arkema, K.K.; Guannel, G.; Verutes, G.; Wood, S.A.; Guerry, A.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Kareiva, P.; Lacayo, M.; Silver, J.M. Coastal Habitats Shield People and Property from Sea-Level Rise and Storms. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 913–918. [CrossRef]

- Pafumi, E.; Angiolini, C.; Sarmati, S.; Bacaro, G.; Fanfarillo, E.; Fiaschi, T.; Foggi, B.; Gennai, M.; Maccherini, S. Spatial Patterns of Coastal Dune Plant Diversity Reveal Conservation Priority Hotspots in and out a Network of Protected Areas. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 54, e03085. [CrossRef]

- Pye, K.; Tsoar, H. Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 457.

- Dewhurst, D. Coastal Dunes: Dune Protection and Improvement Manual for the Texas Gulf Coast. Tex. Gen. Land Off. Austin 2002.

- Williams, A.T. Some Scenic Evaluation Techniques. In In Coastal Scenery; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 43–65.

- Tordoni, E.; Bacaro, G.; Weigelt, P.; Cameletti, M.; Janssen, J.A.M.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Bagella, S.; Filigheddu, R.; Bergmeier, E.; Buckley, H.L.; et al. Disentangling Native and Alien Plant Diversity in Coastal Sand Dune Ecosystems Worldwide. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e12861. [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, D.; Bona, C. Exploring the Functional Strategies Adopted by Coastal Plants Along an Ecological Gradient Using Morpho-Functional Traits. Estuaries Coasts 2022, 45, 114–129. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.L. Dunas Costeras. Investigación y ciencia 2008, 383, 26–35.

- Barbour, M.G.; De Jong, T.M.; Pavlik, B.M. Marine Beach and Dune Plant Communities. In Physiological Ecology of North American Plant Communities; Chabot, B.F., Mooney, H.A., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1985; pp. 296–322. [CrossRef]

- Hesp, P.A. Ecological Processes and Plant Adaptations on Coastal Dunes. J. Arid Environ. 1991, 21, 165–191. [CrossRef]

- Den Dubbelden, K.C.; Knops, J.M.H. The Effect of Competition and Slope Inclination on Aboveground Biomass Allocation of Understorey Ferns in Subtropical Forest. Oikos 1993, 67, 285. [CrossRef]

- Medina, E. Physiological Ecology of Psammophytic and Halophytic Plant Species from Coastal Plains in Northern South America. In Sabkha Ecosystems; Khan, M.A., Boër, B., Ȫzturk, M., Clüsener-Godt, M., Gul, B., Breckle, S.-W., Eds.; Tasks for Vegetation Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 29–56. [CrossRef]

- Maximiliano-Cordova, C.; Martínez, M.L.; Silva, R.; Hesp, P.A.; Guevara, R.; Landgrave, R. Assessing the Impact of a Winter Storm on the Beach and Dune Systems and Erosion Mitigation by Plants. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 734036. [CrossRef]

- Calderisi, G.; Cogoni, D.; Pinna, M.S.; Fenu, G. Recognizing the Relative Effects of Environmental versus Human Factors to Understand the Conservation of Coastal Dunes Areas. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 48, 102070. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cordero, A.I.; Hernández-Calvento, L.; Espino, E.P.-C. Vegetation Changes as an Indicator of Impact from Tourist Development in an Arid Transgressive Coastal Dune Field. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, D.; Pinna, M.S.; Alquini, F.; Cogoni, D.; Ruocco, M.; Bacchetta, G.; Sarti, G.; Fenu, G. Development of a Coastal Dune Vulnerability Index for Mediterranean Ecosystems: A Useful Tool for Coastal Managers? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 187, 84–95. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.C.; Morton, J.K.; Baldry, A.; Bishop, M.J. Backshore Nourishment of a Beach Degraded by Off-Road Vehicles: Ecological Impacts and Benefits. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138115. [CrossRef]

- Prisco, I.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Stanisci, A. A Bridge between Tourism and Nature Conservation: Boardwalks Effects on Coastal Dune Vegetation. J. Coast. Conserv. 2021, 25, 14. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Osorio, Y.T.; Mendoza-González, G.; Martínez, M.L. Sun and Sand Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development in Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8807. [CrossRef]

- Gallitelli, L.; D’Agostino, M.; Battisti, C.; Cózar, A.; Scalici, M. Dune Plants as a Sink for Beach Litter: The Species-Specific Role and Edge Effect on Litter Entrapment by Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166756. [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Fanelli, G.; Gallitelli, L.; Scalici, M. Dunal Plants as Sink for Anthropogenic Marine Litter: The Entrapping Role of Salsola Kali L. (1753) in a Mediterranean Remote Beach (Sardinia, Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 192, 115033. [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Gracia C, A.; Neal, W.J. Dune Ecosystems along the Central Caribbean Coast of Colombia: Evolution, Human Influences, and Conservation Challenges. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 243, 106767. [CrossRef]

- Tirgan, S.; Naqinezhad, A.; Moradi, H.; Kazemi, Z.; Vasefi, N.; Fenu, G. Caspian Remnant Coastal Dunes: How Do Natural and Anthropogenic Factors Impact on Plant Diversity and Vegetation? Plant Biosyst. - Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2022, 156, 1456–1469. [CrossRef]

- Escobar, H.A.T.; Cubides, N.J.G. Caracterización de La Vegetación de La via Parque Isla de Salamanca, Magdalena-Colombia. Colomb. For. 2001, 7, 102–115.

- Gómez, J.F.; Byrne, M.-L.; Hamilton, J.; Isla, F. Historical Coastal Evolution and Dune Vegetation in Isla Salamanca National Park, Colombia. J. Coast. Res. 2017, 33, 632–641. [CrossRef]

- Villate, D.A.; Portz, L.; Manzolli, R.P.; Alcántara-Carrió, J. Human Disturbances of Shoreline Morphodynamics and Dune Ecosystem at the Puerto Velero Spit (Colombian Caribbean). J. Coast. Res. 2020, 95, 711. [CrossRef]

- García-Mora, M.R.; Gallego-Fernández, J.B.; García-Novo, F. Plant Functional Types in Coastal Foredunes in Relation to Environmental Stress and Disturbance. J. Veg. Sci. 1999, 10, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.M.D.; Hesp, P.; Peixoto, J.; Dillenburg, S.R. Foredune Vegetation Patterns and Alongshore Environmental Gradients: Moçambique Beach, Santa Catarina Island, Brazil. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2008, 33, 1557–1573. [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Gracia C., A. From the Closet to the Shore: Fashion Waste Pollution on Colombian Central Caribbean Beaches. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 199, 115976. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, G.; Urrego, L.E.; Gomez Garcia, A.M.; Betancur, S.; Osorio, A.F. Evolucion geomorfologica y vegetacion costera de playa Palmeras, Parque Nacional Natural Isla Gorgona, Pacifico Colombiano. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2014, 42, 622–638. [CrossRef]

- Bertness, M.D.; Gough, L.; Shumway, S.W. Salt Tolerances and The Distribution of Fugitive Salt Marsh Plants. Ecology 1992, 73, 1842–1851. [CrossRef]

- Glenn, E.P.; Nagler, P.L.; Brusca, R.C.; Hinojosa-Huerta, O. Coastal Wetlands of the Northern Gulf of California: Inventory and Conservation Status. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2006, 16, 5–28. [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; Monteiro, M. A Familia Asteracea En a Planicie Litorânea de Picinguaba, Ubatuba, São Paulo. Hoehnea 2006, 33, 71–72.

- Pereira, C.I.; Carvajal, A.F.; Milanés Batista, C.; Botero, C.M. Regulating Human Interventions in Colombian Coastal Areas: Implications for the Environmental Licensing Procedure in Middle-Income Countries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 79, 106284. [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Williams, A.; Anfuso, G. Killing the Goose with the Golden Eggs: Litter Effects on Scenic Quality of the Caribbean Coast of Colombia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 127, 22–38. [CrossRef]

- Gracia C., A.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Castro-Barros, J.D. Non-Native Plant Species in the Atlantico Department Coastal Dune Systems, Caribbean of Colombia: A New Management Challenge. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 603–610. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.A.; Shaltout, K.H.; Kamal, S.A. Mediterranean Sand Dunes in Egypt: Threatened Habitat and Endangered Flora. Life Sci J 2014, 11, 946–956.

- Fois, M.; Cuena-Lombraña, A.; Fenu, G.; Bacchetta, G. Using Species Distribution Models at Local Scale to Guide the Search of Poorly Known Species: Review, Methodological Issues and Future Directions. Ecol. Model. 2018, 385, 124–132. [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, M.; Bartak, V.; Carranza, M.L.; Simova, P.; Acosta, A.T.R. Landscape Pattern and Plant Biodiversity in Mediterranean Coastal Dune Ecosystems: Do Habitat Loss and Fragmentation Really Matter? J. Biogeogr. 2018, 45, 1367–1377. [CrossRef]

- Seif El-Nasr, M.; Bidak, L. Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants Project: National Survey, North Western Coastal Region. First Q. Rep. Mubarak City Sci. Res. Technol. Appl. Egypt 2005.

- Acosta, A.; Carranza, M.L.; Izzi, C.F. Are There Habitats That Contribute Best to Plant Species Diversity in Coastal Dunes? Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 1087–1098. [CrossRef]

- Flórez, C.A.; Etter, A. Caracterización ecológica de las islas Múcura y Tintipán, archipielago de San Bernardo, Colombia. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Exactas Físicas Nat. 2023, 27, 343–356. [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-Agudelo, G.; Zuluaga-Ramírez, S. Notas sobre la vegetación desértica del Parque Eólico Jepírachi, Alta Guajira, Colombia. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Exactas Físicas Nat. 2014, 38, 43. [CrossRef]

- Espejel, I.; Jiménez-Orocio, O.; Castillo-Campos, G.; P. Garcillán, P.; Álvarez, L.; Castillo-Argüero, S.; Durán, R.; Ferrer, M.; Infante-Mata, D.; Iriarte, S.; et al. Flora en playas y dunas costeras de México. Acta Bot. Mex. 2017, 39–81. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.L.B.D.; Queiroz, L.P.D.; Pirani, J.R. Plant Species and Habitat Structure in a Sand Dune Field in the Brazilian Caatinga: A Homogeneous Habitat Harbouring an Endemic Biota. Rev. Bras. Botânica 2004, 27, 739–755. [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. Response: Intermediate-Disturbance Hypothesis. Science 1979, 204, 1345–1345.

- Pinna, M.S.; Bacchetta, G.; Cogoni, D.; Fenu, G. Is Vegetation an Indicator for Evaluating the Impact of Tourism on the Conservation Status of Mediterranean Coastal Dunes? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 674, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, C.P. Beach Carrying Capacity Assessment: How Important Is It? J. Coast. Res. 2002, 36, 190–197. [CrossRef]

- De Ruyck, M.; Soares, A.G.; McLachlan, A. Social Carrying Capacity as a Management Tool for Sandy Beaches. J. Coast. Res. 1997, 822–830.

- Huamantinco Cisneros, M.A.; Revollo Sarmiento, N.V.; Delrieux, C.A.; Piccolo, M.C.; Perillo, G.M.E. Beach Carrying Capacity Assessment through Image Processing Tools for Coastal Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 130, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Kutiel, P.; Zhevelev, H.; Harrison, R. The e!Ect of Recreational Impacts on Soil and Vegetation of Stabilised Coastal Dunes in the Sharon Park, Israel.

- Sanò, M.; Jiménez, J.A.; Medina, R.; Stanica, A.; Sanchez-Arcilla, A.; Trumbic, I. The Role of Coastal Setbacks in the Context of Coastal Erosion and Climate Change. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 943–950. [CrossRef]

- Gónima, L.; Mancera-Pineda, J.E.; Botero, L. Aplicación de Imágenes de Satélite al Diagnóstico Ambiental de Un Complejo Lagunar Estuarino Tropical: Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Caribe Colombiano; Invemar: Santa Marta, Colombia, 1998; pp. 56.

- Franco, H.A. Oceanografía de la ensenada de Gaira; Utadeo: Colombia, 2005; pp.21.

- Posada Posada, B.O.; Henao Pineda, W. Diagnóstico de La Erosión En La Zona Costera Del Caribe Colombiano; Invemar: Colombia, 2008; pp. 200.

- Mancera-Pineda, J.E.; Pinto, G.; Vilardy, S. Patrones de Distribución Estacional de Masas de Agua En La Bahía de Santa Marta, Caribe Colombiano: Importancia Relativa Del Upwelling y Outwelling. Bol. Investig. Mar. Costeras-INVEMAR 2013, 42, 329–360.

- Bona, C.; Moryel Pellanda, R.; Bergmann Carlucci, M.; Giese De Paula Machado, R.; Ciccarelli, D. Functional Traits Reveal Coastal Vegetation Assembly Patterns in a Short Edaphic Gradient in Southern Brazil. Flora 2020, 271, 151661. [CrossRef]

- Sanromualdo-Collado, A.; O’Keeffe, N.; Gallego-Fernández, J.B.; Delgado-Fernández, I.; Martínez, M.L.; Ferrer-Valero, N.; Hernández-Calvento, L. Resultados preliminares del análisis de relaciones entre variables ecológicas y sedimentológicas en la duna costera (foredune) de un sistema de dunas árido. 2019.

- Sánchez, A.M.Z.; Roa, C.E.P.; Gallardo, J.F.; Guzmán, I.D.G. Métodos Analíticos Del Laboratorio de Suelos; Igac: Colombia, 2006;

- Stelmack, J.; Szlyk, J.P.; Stelmack, T.; Babcock-Parziale, J.; Demers-Turco, P.; Williams, R.T.; Massof, R.W. Use of Rasch Person-Item Map in Exploratory Data Analysis: A Clinical Perspective. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2004, 41, 233. [CrossRef]

- Villarreal H., M. Álvarez, S. Córdoba, F.; Escobar, G. Fagua, F. Gast, H. Mendoza, M.; Ospina, A,Umaña M. Manual de Métodos Para El Desarrollo de Inventarios de Biodiversidad; Instituto Alexander Von Humboldt: Bogotá, Colombia, 2004; pp. 236.

- Jost, L. Entropy and Diversity. Oikos 2006, 113, 363–375.

- Hill, M.O. Diversity and Evenness: A Unifying Notation and Its Consequences. Ecology 1973, 54, 427–432. [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.; Fidler, F.; Vaux, D.L. Error Bars in Experimental Biology. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 177, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.H.; Chao, A. iNEXT: An R Package for Rarefaction and Extrapolation of Species Diversity ( H Ill Numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Httpwww R-Proj. Org 2016.

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the Turnover and Nestedness Components of Beta Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 134–143. [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A.; Orme, C.D.L. Betapart: An R Package for the Study of Beta Diversity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 808–812.

- Gallego-Fernández, J.B.; Martínez, M.L. Environmental Filtering and Plant Functional Types on Mexican Foredunes along the Gulf of Mexico. Écoscience 2011, 18, 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.K.; Zinnert, J.C. Topography and Disturbance Influence Trait-based Composition and Productivity of Adjacent Habitats in a Coastal System. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03139. [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Communities in R: Vegan Tutorial.

Figure 1.

Dune profiles along three transects placed on five beaches and coastal dunes on the coast of the Colombian Caribbean. These areas are exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances, with Gairaca being the least disturbed and Costa Verde the most.

Figure 1.

Dune profiles along three transects placed on five beaches and coastal dunes on the coast of the Colombian Caribbean. These areas are exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances, with Gairaca being the least disturbed and Costa Verde the most.

Figure 2.

Environmental variables in five beach-coastal dune systems along the Colombian Caribbean coast. (a) Mean maximum dune height; (b) Mean maximum dune slope; (c) Mean beach width; (d) Mean vegetation width sampled, and (e) Mean plant cover per plot (m2).

Figure 2.

Environmental variables in five beach-coastal dune systems along the Colombian Caribbean coast. (a) Mean maximum dune height; (b) Mean maximum dune slope; (c) Mean beach width; (d) Mean vegetation width sampled, and (e) Mean plant cover per plot (m2).

Figure 3.

Qualitative intensity of anthropogenic disturbances in five beach-coastal dune systems along the Colombian Caribbean coast.

Figure 3.

Qualitative intensity of anthropogenic disturbances in five beach-coastal dune systems along the Colombian Caribbean coast.

Figure 4.

Alpha plant diversity of five beaches from the northern Colombian Caribbean. The following were evaluated: 0D, species richness; 1D, number of common species; and 2D, dominant species in the community. Error bars correspond to the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Alpha plant diversity of five beaches from the northern Colombian Caribbean. The following were evaluated: 0D, species richness; 1D, number of common species; and 2D, dominant species in the community. Error bars correspond to the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Frequency of different plant growth forms in five beaches along the Colombian Caribbean, exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances. Gairaca was the least disturbed, and Costa Verde was the most.

Figure 5.

Frequency of different plant growth forms in five beaches along the Colombian Caribbean, exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances. Gairaca was the least disturbed, and Costa Verde was the most.

Figure 6.

Relative Importance Values of plant species growing on the beach and coastal dunes in five beaches along the Colombian Caribbean, exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances, with Gairaca being the least disturbed and Costa Verde the most. The most important species are indicated in each beach through abbreviated nomenclature: M. odo (Morisonia odoratissima), P. pin (Platymiscium pinnatum), S. tam (Senegalia tamarindifolia), M. ten (Morisonia tenuisiliqua) E. hon (Erythroxylum hondense), A. fla (Althernantera flavescens), P. dul (Pithecellobium dulce), T sta (Tecoma stans), A. grav (Astronium graveolens) C. ser (Chamaecrista serpens), B. fru (Bonellia frutescens), S. tri (Sphagneticola trilobata), C. nuc (Cocos nucifera), C. uvi (Coccoloba uvifera), C. ros (Canavalia rosea), S. por (Sesuvium portulacastrum), C. cil (Cenchrus ciliaris), S. vir (Sporobolus virginicus), P. hal (Portulaca halimoides), M. pyr (Melochia pyramidata). N. Jul (Neltuma juliflora), I. pes (Ipomoea pes-caprae).

Figure 6.

Relative Importance Values of plant species growing on the beach and coastal dunes in five beaches along the Colombian Caribbean, exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances, with Gairaca being the least disturbed and Costa Verde the most. The most important species are indicated in each beach through abbreviated nomenclature: M. odo (Morisonia odoratissima), P. pin (Platymiscium pinnatum), S. tam (Senegalia tamarindifolia), M. ten (Morisonia tenuisiliqua) E. hon (Erythroxylum hondense), A. fla (Althernantera flavescens), P. dul (Pithecellobium dulce), T sta (Tecoma stans), A. grav (Astronium graveolens) C. ser (Chamaecrista serpens), B. fru (Bonellia frutescens), S. tri (Sphagneticola trilobata), C. nuc (Cocos nucifera), C. uvi (Coccoloba uvifera), C. ros (Canavalia rosea), S. por (Sesuvium portulacastrum), C. cil (Cenchrus ciliaris), S. vir (Sporobolus virginicus), P. hal (Portulaca halimoides), M. pyr (Melochia pyramidata). N. Jul (Neltuma juliflora), I. pes (Ipomoea pes-caprae).

Figure 7.

Canonical correspondence analyses showing how natural (a) and anthropogenic (b) variables affect community composition of plant species growing on the beach and coastal dunes in five locations along the Colombian Caribbean, exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances, with Gairaca being the least disturbed and Costa Verde the most.

Figure 7.

Canonical correspondence analyses showing how natural (a) and anthropogenic (b) variables affect community composition of plant species growing on the beach and coastal dunes in five locations along the Colombian Caribbean, exposed to increasing anthropogenic disturbances, with Gairaca being the least disturbed and Costa Verde the most.

Figure 8.

Location of the study sites in the northern Colombian Caribbean. Satellite images from Google Earth.

Figure 8.

Location of the study sites in the northern Colombian Caribbean. Satellite images from Google Earth.

Table 1.

Jaccard’s species turnover between five beach-coastal dune systems along the Colombian Caribbean coast. Values closest to 1 show maximum dissimilarity between sites (the sites do not share any species). Bold letters highlight the highest values. Sites are organized from least (Gairaca) to most disturbed (Salguero)

Table 1.

Jaccard’s species turnover between five beach-coastal dune systems along the Colombian Caribbean coast. Values closest to 1 show maximum dissimilarity between sites (the sites do not share any species). Bold letters highlight the highest values. Sites are organized from least (Gairaca) to most disturbed (Salguero)

| Turnover component (bjtu) |

| |

Gairaca |

Lipe |

Mendihuaca |

Salguero |

| Lipe |

0.755 |

|

|

|

| Mendihuaca |

0.938 |

0.985 |

|

|

| Salguero |

0.893 |

0.912 |

0.873 |

|

| Costa Verde |

0.863 |

0.651 |

0.982 |

0.840 |

| Nestedness component (bjne) |

| |

Gairaca |

Lipe |

Mendihuaca |

Costa_Verde |

| Lipe |

0.051 |

|

|

|

| Mendihuaca |

0.003 |

0.002 |

|

|

| Costa_Verde |

0.024 |

0.003 |

0.023 |

|

| Salguero |

0.036 |

0.030 |

0.003 |

0.006 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study sites located along the northern Colombian Caribbean coast. Sites are organized from least to most disturbed. Physical-chemical characteristics of the sand in each site are: pH, Salinity (%); Condunctivity (µs/cm); Humidity (%) and Organuc Matter (%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study sites located along the northern Colombian Caribbean coast. Sites are organized from least to most disturbed. Physical-chemical characteristics of the sand in each site are: pH, Salinity (%); Condunctivity (µs/cm); Humidity (%) and Organuc Matter (%).

| Study site |

Location |

Tourism |

Environmental attributes |

Anthropogenic activities |

Sand |

| Gairaca |

Located in a protected Natural Area |

Medium intensity tourism |

Located between two hills. Moderately accessible |

Some houses, some food provision |

pH = 7.1(0.9); Sal=0.1(0.1); Cond=357(191); Hum=1.6(1.9); OM=1.7(0.9) |

| Lipe |

Close to the city of Santa Marta and a river |

Low tourism. |

Limited accessibility through paths and by boat |

Some paths. |

pH = 6.9(1.1); Sal=0.1(0.3); Cond=215(232); Hum=3.1(2.3); OM=0.9(0.8) |

| Mendihuaca |

Close to the Mendihuaca River |

Moderate-density houses, hotels, and restaurants |

Easily accessible |

Local inhabitants and tourists visit the beach. |

pH = 6.5(0.6); Sal=0.2(0.5); Cond=478(975); Hum=6.9(6.9); OM=1.4(0.9) |

| Salguero |

Close to the Gaira River. |

High-density hotels |

Easily accessible |

High intensity tourism. |

pH = 6.9(0.8); Sal=0.1(4); Cond=8141(18553); Hum=5.4(6.7); OM=1.5(1.1) |

| Costa Verde |

Close to Costa Verde mangroves and the Córdoba river. |

Unplanned urban and tourism expansion. |

Easily accessible |

Growing tourism, crops. |

pH =6.8(0.8); Sal=0.2(0.6); Cond=363(746); Hum=2.2(4.2); OM=1.8(0.8) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).