1. Introduction

Quantifying fine-scale motor behaviour is a critical frontier in neuroscience, bridging the gap between the function of neural circuits and observable behavioural outcomes. This capability is essential for understanding the progression of cerebral diseases and evaluating the efficacy of therapeutic interventions in clinical and preclinical settings. In animal models, precise behavioural quantification is essential for understanding neural circuit dynamics, tracking disease progression and evaluating new therapeutic protocols. This is especially important when studying neurological disorders, where motor deficits are key indicators of underlying neural dysfunction. These disorders include neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, as well as traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and strokes.

Traditional behavioural scoring approaches in neuroscience research have long been hampered by inherent limitations. While video-based assessments are useful, they suffer from observer bias, low temporal resolution and poor inter-rater reliability, constraints that become particularly problematic when attempting to capture the subtle motor deficits characteristic of many neurological conditions. These limitations have created an urgent need for automated, objective and high-resolution behavioural quantification tools that can operate at the millimetric scale required for precise neurobehavioural analysis.

The advent of markerless pose estimation frameworks, particularly DeepLabCut (DLC), has transformed this field by enabling robust, high-resolution tracking of anatomical landmarks across different species and experimental paradigms [

1]. This technology has proven especially valuable in complex behavioural assays requiring subcellular precision, such as skilled reaching tasks and the Montoya staircase test [

2,

3]. These paradigms are widely used to evaluate fine motor coordination in rodent models of neurological disorders, providing valuable insight into the motor impairments associated with conditions ranging from stroke to neurodegenerative diseases.

DeepLabCut software is now one of the benchmark tools for markerless posture estimation in neuroscience and beyond. It was initially described in 2018 by Mathis et al. in [

1]. and detailed in a standardized protocol [

4], and hundreds of studies now use it [

5]. Recent studies have demonstrated the value of precise kinematic analysis in both preclinical and clinical settings. For instance, [

6]. showed that detailed motor behavior quantification can reveal subtle neurological deficits in rodent models, while Wang et al. [

7]. highlighted the importance of fine motor tracking in neurodevelopmental disorders research.

However, although DLC has gained widespread adoption in neuroscience research, its performance depends fundamentally on the CNN architecture used for pose estimation. This architectural dependence introduces a significant challenge: the optimal CNN backbone varies considerably depending on the specific behavioural task, the required precision and the computational constraints of the research environment. In recent years, multiple CNN architectures, including various ResNet variants, MobileNet, EfficientNet and specialised architectures such as DLCRNet, have been integrated into the DLC framework. Each of these architectures offers different trade-offs between accuracy, computational efficiency and robustness to challenging conditions [

8,

9].

The Montoya Staircase test is a particularly demanding benchmark for pose estimation systems due to its complexity. This assay requires tracking fine digit movements against a backdrop of frequent occlusions, small inter-keypoint distances and highly variable limb trajectories, conditions that push the limits of current pose estimation technologies. For such challenging tasks, selecting an appropriate CNN backbone is crucial, as suboptimal choices can lead to insufficient spatial resolution or poor robustness to occlusions, compromising the reliability of subsequent kinematic analyses.

Despite the critical importance of architecture selection, systematic comparisons of CNN backbones within the DLC framework are notably absent from the literature. Existing studies tend to focus on a single architecture or provide evaluations that are limited to simpler locomotion paradigms. This leaves a significant methodological gap for researchers seeking to optimise pose estimation pipelines for complex behavioural assays that require sub-pixel localisation accuracy.

This study addresses this gap by presenting the first comprehensive comparison of nine convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures implemented within DeepLabCut for tracking forelimb movements during the Montoya Staircase test. Using a standardized training and assessment pipeline, we systematically evaluate these models across multiple performance dimensions, including spatial accuracy, robustness to occlusions and computational efficiency. By benchmarking these architectures in both control and M1-lesioned mouse models, we provide neuroscience researchers with actionable methodological guidance and contribute to the standardization of pose estimation methodologies in preclinical research. Beyond advancing our understanding of CNN architectures for fine motor tracking, this comparative evaluation offers practical recommendations for biomedical engineers and neuroscientists seeking to optimize pose estimation pipelines for both preclinical studies and translational applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Subjects and Behavioural Paradigm

All experiments were conducted using 8-12 week old adult C57BL/6 mice. The animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions, with a 12-hour light–dark cycle, and had ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the appropriate local ethics committee under authorization APAFIS n° 43824-2023061416402730 v4 and were conducted in accordance with European Union guidelines for animal research.

The Montoya staircase test was employed as the behavioural paradigm [

2]. This test uses a dual staircase apparatus in which the mice must retrieve food pellets from narrow steps using precise forelimb movements. This task produces complex kinematic patterns involving digit coordination, reach planning and grasp execution, making it ideal for evaluating pose estimation algorithms in challenging conditions involving frequent occlusions and the need for fine motor control.

2.2. Video Acquisition and Preprocessing

Behavioural sessions were recorded using a high-speed digital camera positioned laterally to the staircase apparatus, ensuring consistent visualisation of reaching movements. Video recordings were captured at 120 frames per second with a resolution of 1280×1024 pixels. A diffused LED lighting system was employed throughout all recording sessions to maintain optimal lighting conditions and minimise shadows.

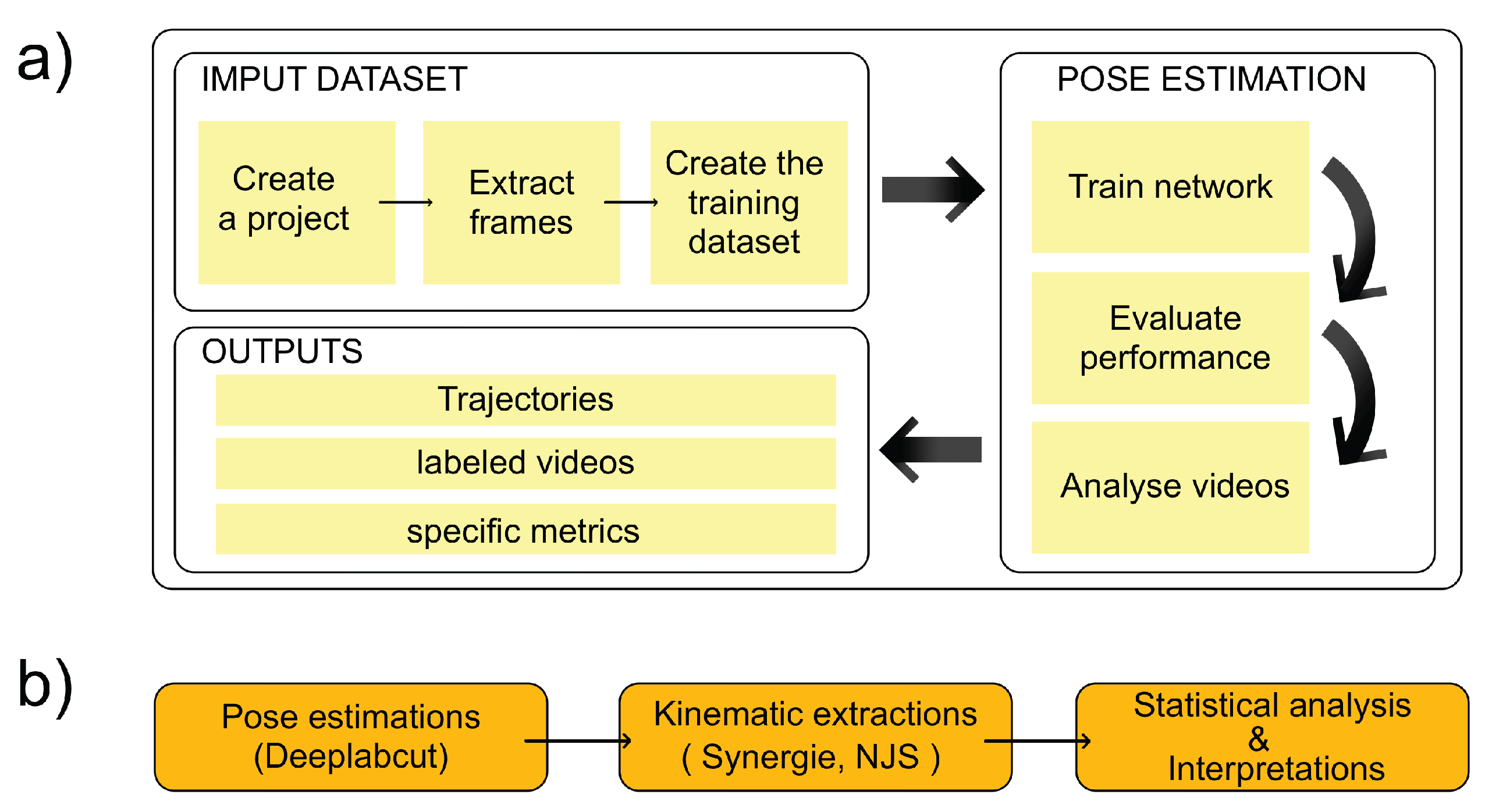

Following acquisition, videos were processed using established protocols to extract individual frames for subsequent analysis. Frames exhibiting motion blur or poor visibility were excluded from further processing to maintain data quality. This pre-processing stage ensured that only high-quality images were used for model training and evaluation. Once the images have been acquired, the analysis pipeline is as shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Keypoint Annotation and training procedure

A representative subset of video frames was selected for manual annotation using the DeepLabCut labeling interface. A comprehensive annotation protocol was developed to identify key anatomical landmarks that are essential for analysing forelimb kinematics. A total of 2,400 frames, representing a variety of movement patterns, were manually annotated by trained researchers. To ensure consistent annotations, inter-rater reliability was assessed and maintained above acceptable thresholds throughout the process.

All models were trained using DeepLabCut version 2.X under identical experimental conditions to allow fair comparison. Training and validation sets were created using a fixed split that preserved variability in behavioral states across both partitions. We used 10,000 annotated frames for training, split into 80% training and 20% validation sets. We employed the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate tailored to each architecture’s stability during preliminary experiments. Data augmentation procedures were applied to improve generalization and included random rotation, contrast jittering, and minor spatial shifts. Data augmentation included random rotations (±15°), contrast adjustments (±20%), and spatial shifts (±5 pixels). These transformations mimic natural variability in experimental recordings and reduce the risk of overfitting. Each model was trained until convergence of the validation loss, with an early-stopping criterion applied when no improvement was observed for a predetermined number of epochs. Training was performed on a dedicated GPU workstation, NVIDIA QUADRO T1000, ensuring that runtime differences between architectures reflected the models themselves rather than hardware inconsistencies.

2.3. CNN Architectures Evaluated

We evaluated nine convolutional neural network architectures compatible with DeepLabCut: ResNet-50, ResNet-101, ResNet-152, MobileNetV2 [

8], EfficientNet-B0, EfficientNet-B3 [

9], DLCRNet_ms5, DLCRNet_stride16_ms5, and DLCRNet_stride32_ms5 (

Table 1). These architectures were chosen to cover a broad spectrum of design strategies, depths, and computational requirements. The ResNet family represents classical deep residual networks in increasing depth, enabling strong feature extraction through skip connections that facilitate the learning of complex postural configurations [

10]. MobileNetV2 and EfficientNet variants prioritize computational efficiency, using depthwise-separable convolutions and compound scaling to achieve favorable accuracy–parameter trade-offs, making them suitable for resource-limited environments. In contrast, the DLCRNet models were specifically developed within the DeepLabCut framework to enhance pose estimation under challenging conditions. DLCRNet_ms5 integrates multi-scale feature extraction to improve robustness to occlusions and small-structure tracking, while the stride-16 and stride-32 variants adjust internal resolution to trade spatial precision for faster inference. Together, these nine architectures provide a comprehensive basis for assessing how network depth, multi-scale processing, parameterization, and computational footprint influence pose-estimation performance in a fine motor task requiring subpixel accuracy.

2.4. Performance Evaluation

In order to assess the performance characteristics of each CNN architecture comprehensively, we implemented a standardised evaluation framework that incorporated six critical metrics capturing different aspects of pose estimation quality. Spatial accuracy was quantified using root mean square error (RMSE) in pixels to measure the average distance between predicted and ground truth keypoint locations, providing a fundamental assessment of model precision. Additionally, we calculated the percentage of correct keypoints within 5 pixels (PCK@5px), which specifically evaluates the model's ability to achieve clinically relevant accuracy levels for fine motor tracking. Mean average precision (mAP) across multiple thresholds provided a comprehensive measure of overall prediction quality, accounting for varying degrees of localisation accuracy [

11]..

We assessed computational performance through two practical metrics: inference speed, measured in frames per second (FPS) at 720p resolution, which indicates the model's suitability for real-time applications; and GPU memory requirements, measured in gigabytes (VRAM), which reflect the computational resources needed for deployment. In recognition of the specific challenges posed by the staircase apparatus, we developed an occlusion robustness score ranging from 1 to 5 to systematically evaluate each model's ability to maintain accurate tracking when critical keypoints were partially obscured, a frequent occurrence in this behavioural paradigm.

These carefully selected metrics provide a holistic assessment of each architecture's performance, balancing technical capabilities with practical considerations for neuroscience research applications. By incorporating measures of accuracy, computational efficiency and robustness to task-specific challenges, our evaluation framework addresses the multifaceted requirements of high-precision behavioural quantification in complex experimental setups.

All performance metrics were statistically compared across network architectures using appropriate inferential tests. Normally distributed variables were analyzed via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc tests, whereas non-parametric distributions were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons. Confidence intervals at 95% were computed for each metric to assess variability and reliability. Effect sizes such as Cohen’s d or η² were reported whenever relevant, enabling a more nuanced interpretation of differences between models beyond statistical significance alone.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Performance of CNN Architectures

As shown in

Table 2, the nine architectures evaluated show clearly differentiated performance for tracking digital points and pellets in the staircase test in side view. `

In general, DLCRNet multi-scale models stand out clearly from traditional architectures based on ResNet, MobileNet, or EfficientNet. DLCRNet_ms5 achieves the best overall spatial accuracy, with an average RMSE of 2.8 pixels, a PCK@5px of 95.9%, and an mAP score of 91.07%. DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 achieves very similar performance (RMSE = 2.93 px; PCK@5px = 95.15%; mAP = 90.84%) while offering a more favorable computational trade-off. Conversely, MobileNetV2 has the lowest performance, particularly on digital keypoints, with an RMSE of 3.58 px and a PCK@5px of 90.7%, which limits its use for movements with high spatial constraints.

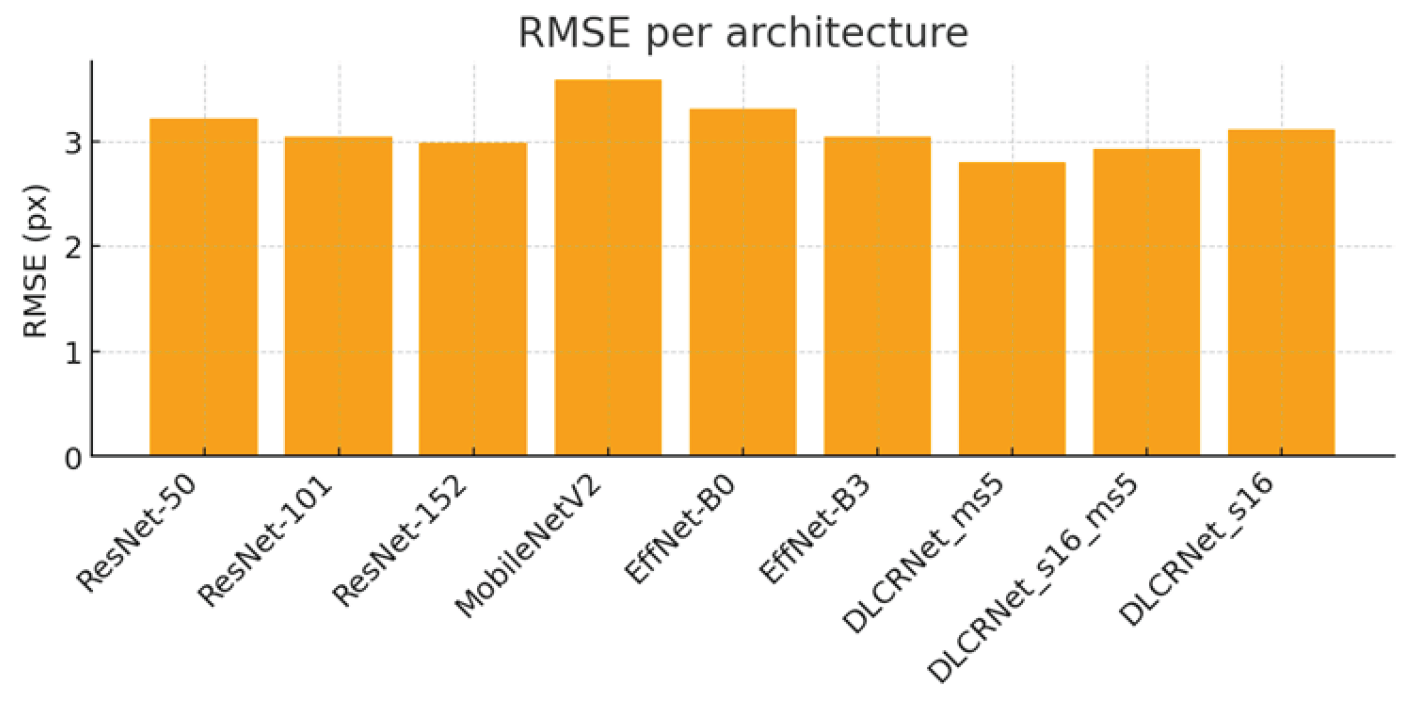

3.2. Spatial Accuracy: RMSE, PCK@5px, and mAP

Performance in terms of RMSE (

Figure 2) demonstrates the clear superiority of DLCRNet architectures. While ResNet-50 to 152 vary between 2.93 and 3.21 pixels of average error, the DLCRNet-ms5 and stride16 networks fall below 3 pixels, which is crucial for tracking small objects such as fingers or pellets. EfficientNet models show intermediate accuracy, with EfficientNet-B3 achieving an RMSE of 3.04 px and a PCK@5px of 94.8%, reflecting increased sensitivity to micro-movements but slight fragility in the face of contrast variations

(Simon et al.

, 2014).

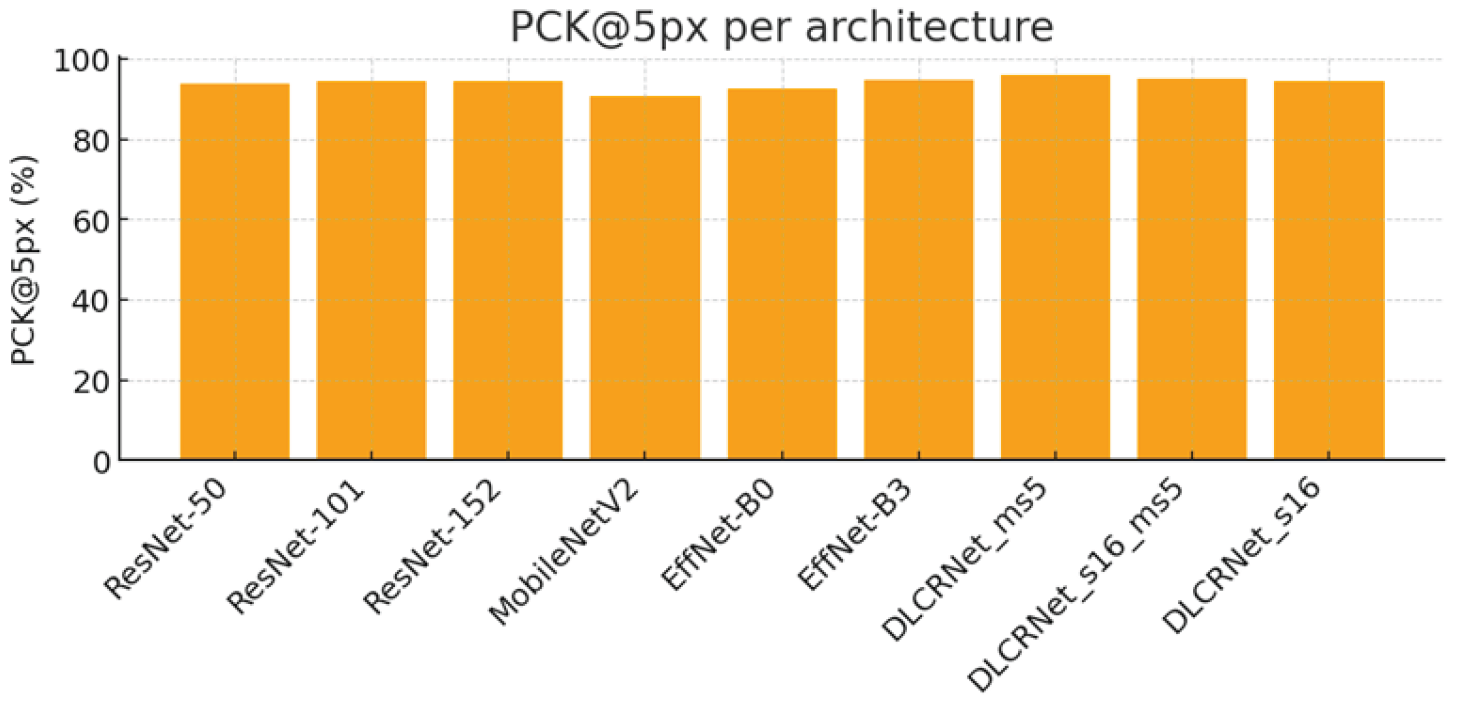

PCK@5px (

Figure 3) highlights the advantage of DLCRNet models in critical areas of fine movement. DLCRNet_ms5 achieves a PCK of 95.9%, outperforming all ResNet and EfficientNet models. ResNet-50, used as a baseline, offers solid performance (PCK = 93.7%), but is insufficient to capture digital details subject to occlusion in the side view. MobileNetV2 achieves the lowest score (90.7%), confirming its inability to provide accuracy compatible with kinematic analysis of fine grasping.

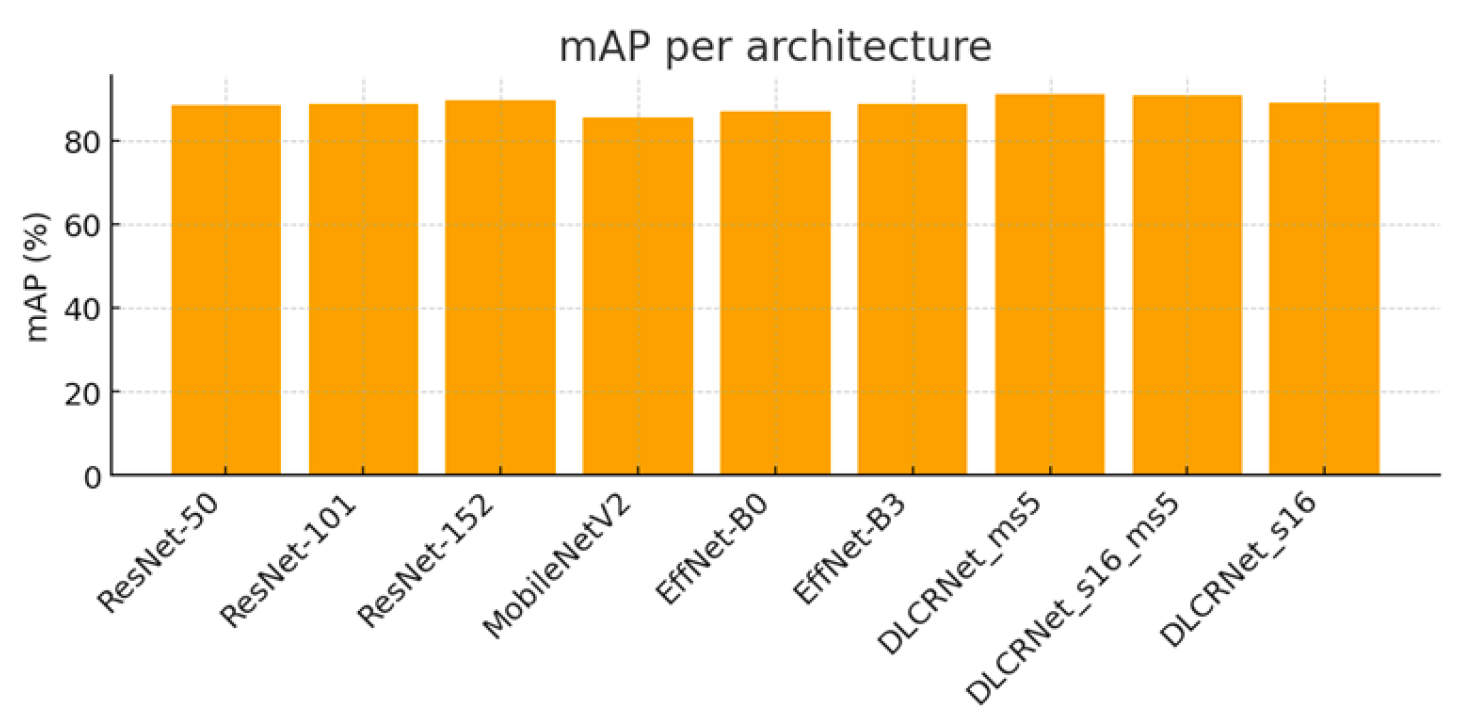

Consistently, the mAP score (

Figure 4) confirms the superiority of the DLCRNet_ms5 model (91.07%), followed closely by stride16 (90.84%). ResNet architectures plateau between 88.5% and 89.7%, while MobileNet and EfficientNet-B0 remain below 86%, reflecting less robust performance on strict accuracy thresholds.

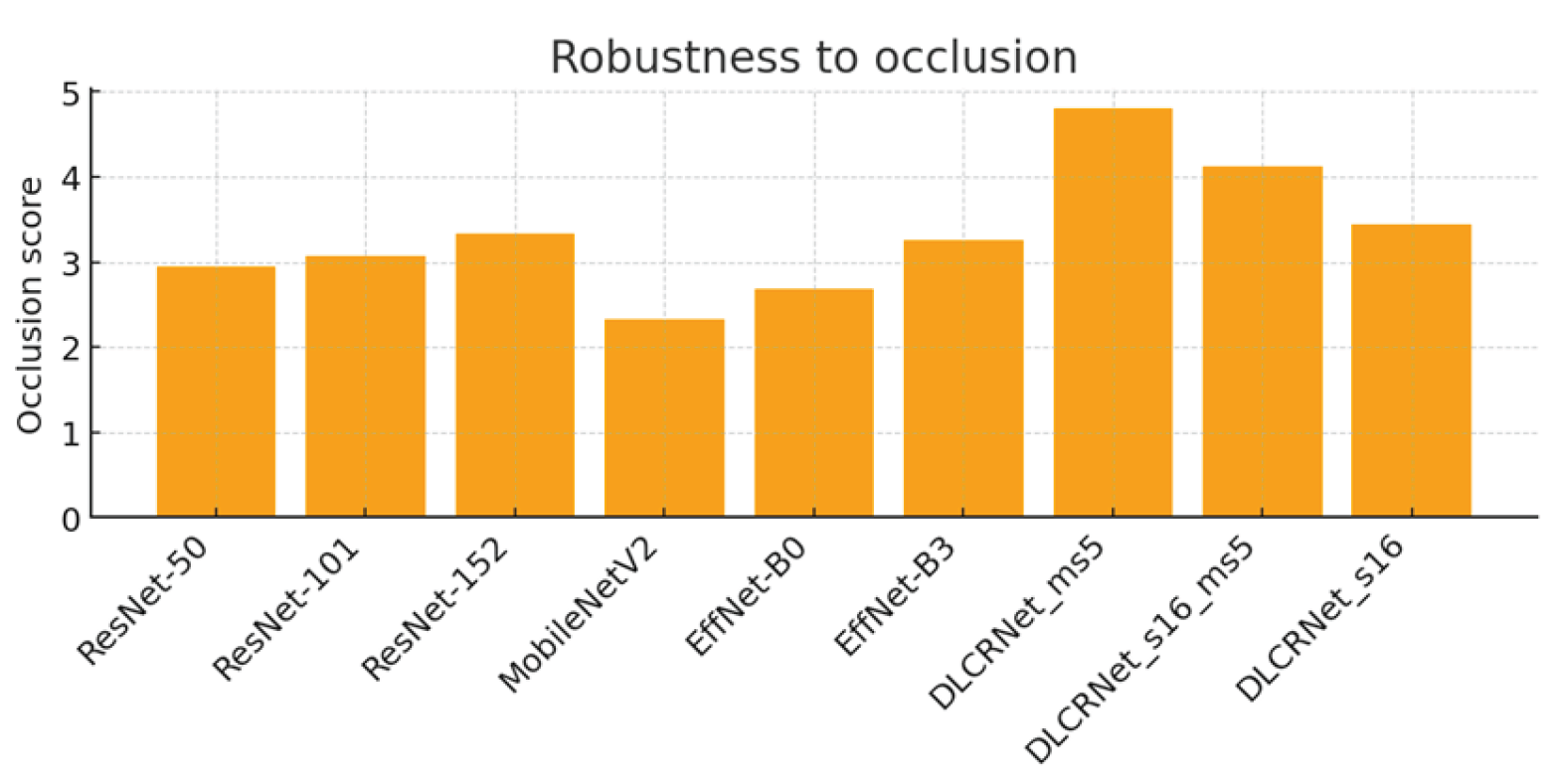

3.3. Robustness to Occlusions

Robustness to occlusions (

Figure 5) is an essential criterion in the staircase task, as fingers and the pellet frequently disappear behind the steps. The results show that DLCRNet multi-scale models are by far the most resistant: DLCRNet_ms5 scores 4.8/5, followed by DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 (4.13/5). In contrast, MobileNetV2 (2.33/5) and EfficientNet-B0 (2.69/5) frequently lose digital keypoints during lateral occlusion, compromising pellet contact detection.

ResNet models show intermediate robustness (between 2.9 and 3.34/5), which is sufficient for overall movements but insufficient to capture digital opening or pellet slippage when visibility is reduced. EfficientNet-B3 achieves adequate robustness (3.25/5), but lags behind DLCRNet models, which, thanks to their native multi-scale processing, maintain spatial consistency even in cases of partial masking.

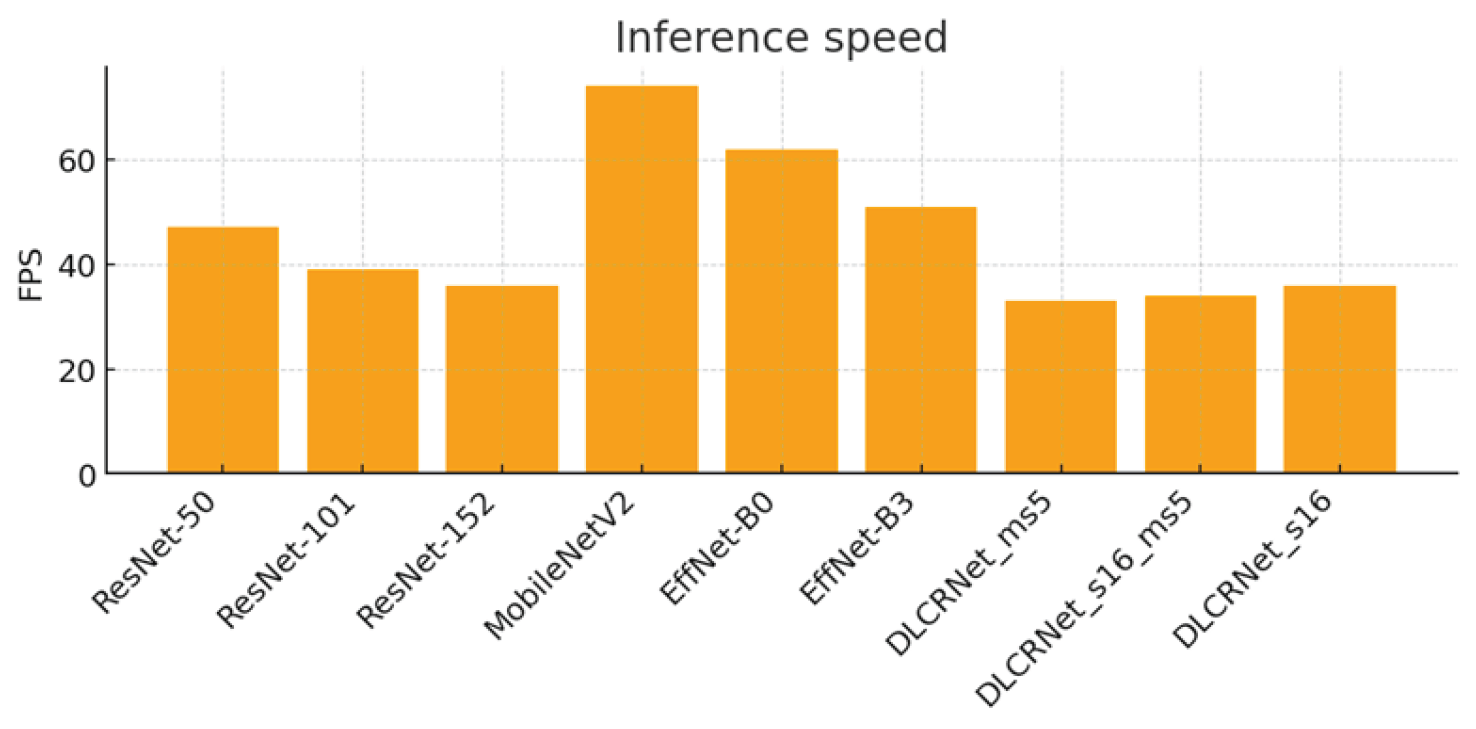

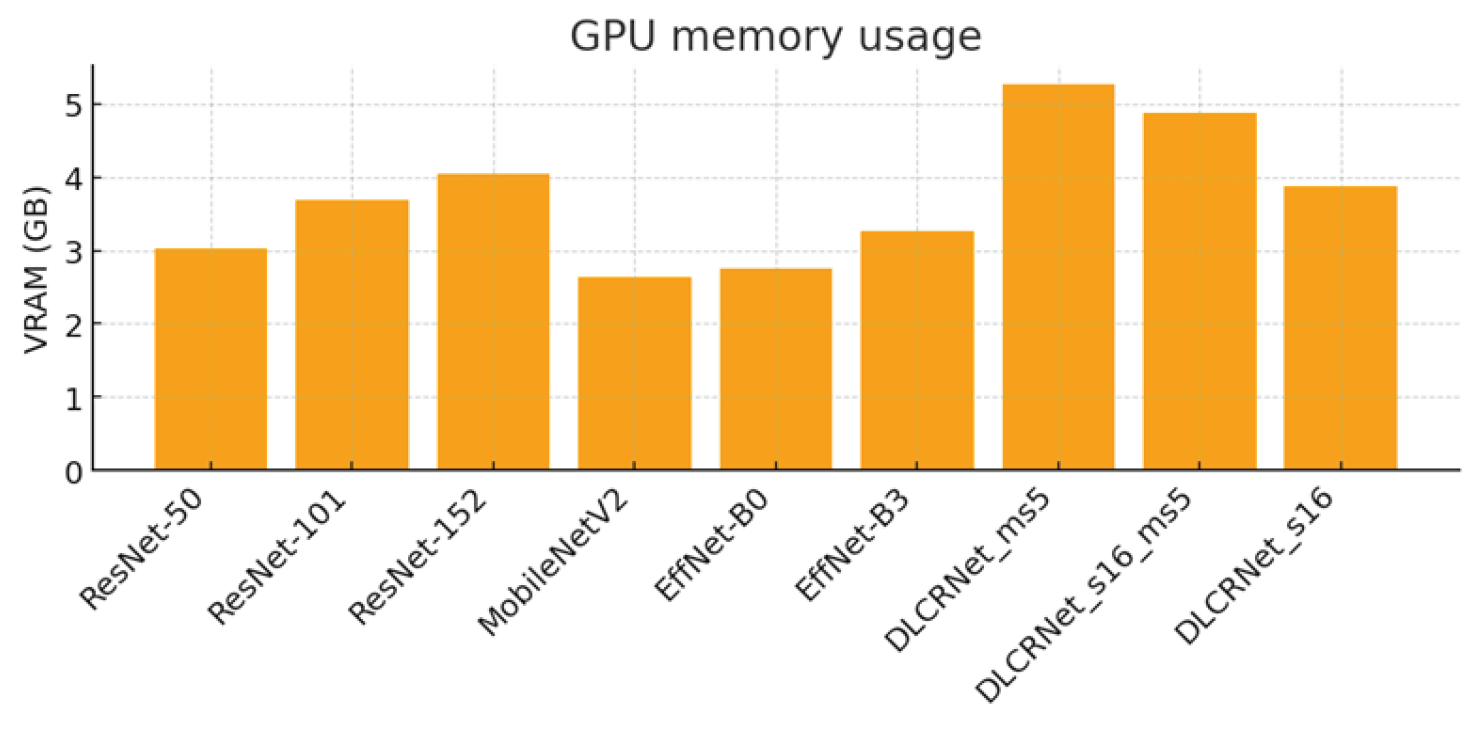

3.4. Computational Cost: FPS and VRAM

Analysis of the computational cost (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) highlights significant trade-offs between speed, memory, and accuracy. Lightweight architectures such as MobileNetV2 achieve high speeds (74 FPS) and a low memory footprint (2.64 GB VRAM), but at the cost of insufficient accuracy for fine motion analysis. Conversely, deep architectures such as ResNet-152 or DLCRNet_ms5 require more memory (up to 5.26 GB) and offer modest FPS (36 FPS), but produce the best spatial and kinematic estimates.

DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 stands out as an interesting compromise, combining accuracy almost equivalent to the ms5 model with slightly higher throughput (34 FPS) and more moderate memory usage (4.87 GB). This model appears to be particularly well suited to analyses requiring volume processing without sacrificing the finesse of digital tracking.

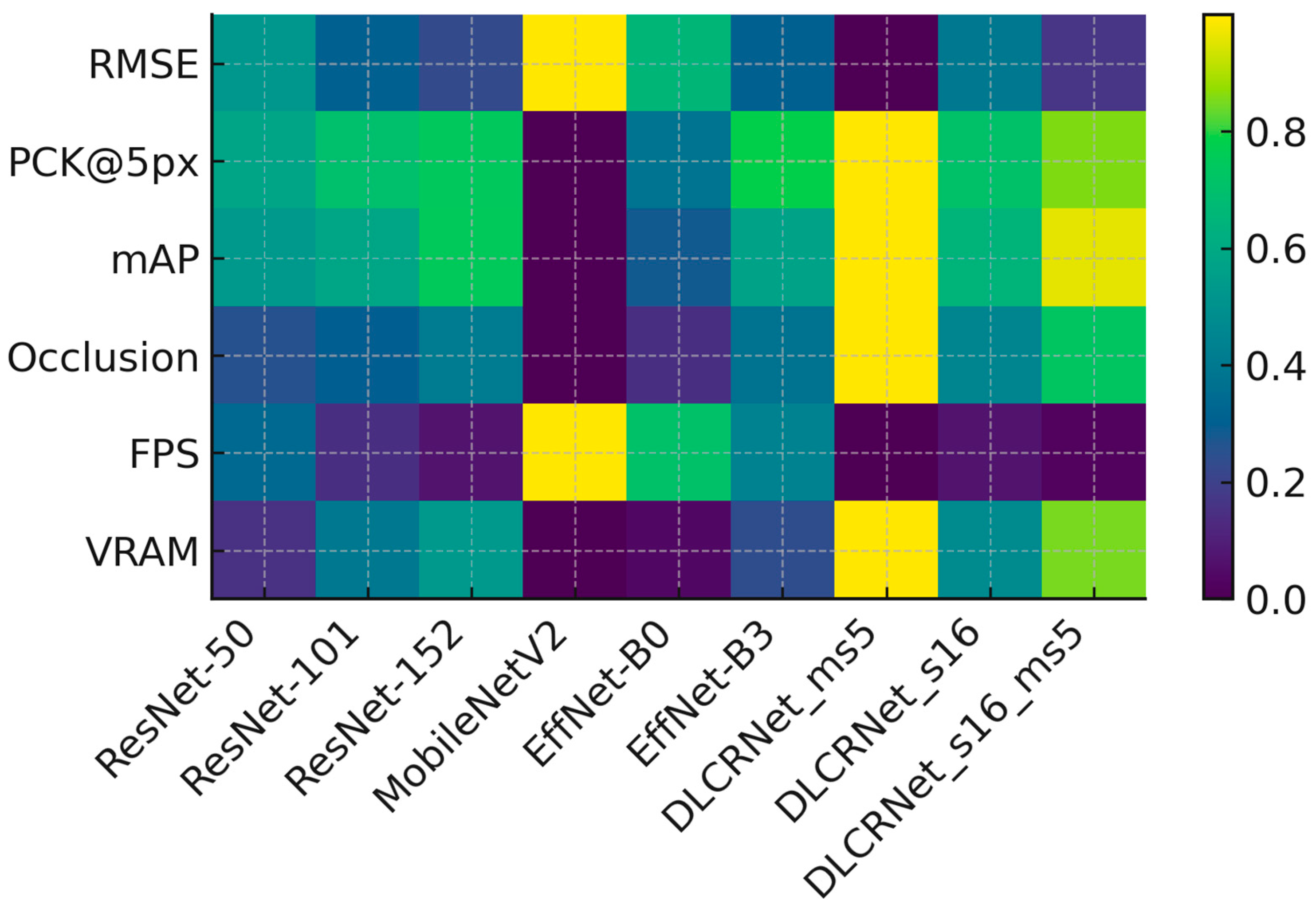

3.5. Comparative Summary

The combination of the three key metrics (RMSE, PCK@5px, Occlusion Robustness) reveals a clear ranking of architectures for the staircase task. DLCRNet_ms5 is the best-performing model, but also the most expensive. DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 represents the best overall compromise, providing excellent accuracy while remaining usable on standard computing machines. EfficientNet-B3 offers an interesting alternative if the image is of high quality and has little noise. ResNet models, although stable and predictable, fail to reliably capture fingers during occlusions. Finally, MobileNetV2 does not meet the accuracy requirements for kinematic analysis of reaching.

These observations, illustrated on

Figure 8, confirm that multi-scale architectures are best suited to capture micro-movements of the fingers in a task where visibility is intermittent.

4. Discussion

We conducted a systematic comparison of convolutional neural network architectures within DeepLabCut to investigate the optimal balance between accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency for quantifying fine motor behaviour in the mouse staircase task. The superior performance of multi-scale DLCRNet models, particularly DLCRNet_ms5 and DLCRNet_stride16_ms5, demonstrates the significance of architectural design in capturing micro-movements that are subject to occlusion and variability, a frequent issue in neurobehavioural assays.

4.1. Architecture Performance and Trade-Offs

The clear superiority of DLCRNet architectures over ResNet and EfficientNet variants emphasises the importance of multi-scale feature extraction for tasks requiring sub-pixel accuracy. DLCRNet_ms5's ability to achieve an RMSE below 3 pixels and a PCK@5px of 95.9% demonstrates its capacity to resolve fine details, such as digit movements and pellet interactions, which are crucial for kinematic analysis [

1]. Meanwhile, DLCRNet_stride16_ms5's modest computational demands make it particularly suitable for large-scale video processing without sacrificing spatial precision. These findings are particularly relevant for preclinical neuroscience, where precise quantification of motor behavior is essential for understanding neural circuit function and evaluating the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [

12].

The performance of lightweight architectures such as MobileNetV2 [

8]. and EfficientNet-B0 [

9]. illustrates the inherent trade-offs between computational efficiency and accuracy. While these models offer high speeds and low memory footprints, their reduced robustness to occlusions and fine movements limits their applicability to high-precision behavioural tasks. This observation is particularly relevant for laboratories with limited computational resources, where the choice of architecture must strike a balance between performance and practical constraints.

4.2. Implications for Neurobehavioural Research

Our results have significant implications for the use of pose-estimation tools in preclinical neuroscience research. The staircase task is a model of skilled reaching that poses unique challenges due to frequent occlusions and the requirement for millimetric precision. The ability of DLCRNet models to maintain stable digit trajectories, even in conditions of poor visibility, suggests their potential for studying motor recovery in disease models where limb coordination is impaired. For example, in models of traumatic brain injury (TBI) or stroke, where motor deficits frequently affect digit function, the reliable performance of DLCRNet architectures could help to detect subtle recovery patterns or the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions [

13,

14].

Identifying kinematic signatures associated with post-lesion motor deficits is particularly noteworthy. Only the DLCRNet_ms5 and stride16_ms5 models reliably detected reduced reach amplitude, impaired digit opening and increased pellet slippage, key indicators of motor dysfunction in rodent models of neurological disorders. This capability is crucial for translating behavioural data into meaningful insights about neural circuit function and dysfunction, providing a foundation for future studies on motor recovery and rehabilitation.

4.3. Broader Impact and Future Directions

Beyond the staircase task, our findings provide guidance on selecting CNN architectures for a variety of behavioural assays requiring the quantification of fine motor skills. The superior performance of multi-scale models suggests that similar benefits could be observed in other tasks involving complex movements, such as locomotion analysis or social interaction paradigms with sophisticated multi-animal tracking systems [

15]. Additionally, the computational efficiency of models such as DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 opens possibilities for real-time applications where rapid feedback is essential for experimental or clinical decision-making processes.

Looking ahead, there are several areas that warrant further exploration. Firstly, integrating additional sensory data, such as depth imaging or inertial measurement units (IMUs), could improve the accuracy of pose estimation in challenging conditions. Secondly, applying these models to other species [

16] or to human kinematic analysis [

17] could increase their usefulness in comparative neuroscience and clinical research. Finally, developing automated pipelines for data annotation and model training could make advanced pose estimation tools more accessible in neuroscience laboratories.

4.4. Limitations and Considerations

While our study provides a comprehensive comparison of CNN architectures, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The evaluation was conducted on a specific behavioural task, and the generalisability of these findings to other paradigms remains to be determined. Additionally, the computational requirements of deeper architectures may limit their adoption in environments with limited resources. Future work should therefore explore ways to optimise these models for broader applicability and ease of use.

In conclusion, this study shows that choosing the right CNN architecture in DeepLabCut can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of quantifying fine motor behaviour in complex tasks, such as the Montoya staircase test. By providing empirical guidance on model selection, particularly highlighting the superior performance of DLCRNet architectures, we aim to equip researchers with the tools needed to optimise pose estimation pipelines for rigorous behavioural quantification. These findings have significant implications for preclinical and clinical research, where precise motor behaviour analysis is essential for understanding neurological disorders, evaluating therapeutic interventions and advancing disease modelling. The ability of DLCRNet models to capture subtle motor details, even under challenging conditions such as occlusions, establishes them as valuable assets for applications ranging from drug development to rehabilitation assessment. This bridges the gap between technical advancements in pose estimation and their practical deployment in biomedical research.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted a systematic comparison of nine convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures within DeepLabCut for high-precision forelimb tracking in the mouse staircase task. Our results demonstrate that the choice of CNN architecture significantly affects the accuracy, robustness and computational efficiency of pose estimation in complex behavioural assays. Of the models evaluated, the multi-scale DLCRNet architectures, specifically DLCRNet_ms5 and DLCRNet_stride16_ms5, were the most effective, providing superior spatial accuracy and robustness to occlusions, critical features for quantifying fine motor behaviour in neurobehavioural research.

The superior performance of DLCRNet models highlights their potential for use in preclinical neuroscience, where the precise quantification of motor behaviour is essential for understanding the function of neural circuits and for evaluating the efficacy of therapeutic interventions. Their ability to reliably detect kinematic signatures associated with motor deficits, such as reduced reach amplitude and impaired digit opening, suggests their potential utility in the study of neurological disorders involving compromised fine motor coordination, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Looking ahead, our findings provide actionable guidance for researchers seeking to deploy pose estimation pipelines in high-precision behavioural assays. The clear superiority of multi-scale architectures emphasises the importance of architectural design in capturing the nuances of complex motor behaviours. Future work could explore integrating additional sensory data, such as depth imaging or inertial measurement units, to enhance pose estimation accuracy in challenging conditions. Furthermore, applying these models to other species or human kinematic analysis could extend their use in comparative neuroscience and clinical research.

In conclusion, this study makes a valuable contribution to the standardisation of pose estimation methodologies in preclinical neuroscience, while also supporting the wider adoption of deep learning-based behavioural quantification in biomedical [

7]. By providing empirical guidance on model selection, our aim is to make it easier to use advanced pose estimation tools for rigorous behavioural quantification in neuroscience and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, VF; methodology, LB; software, VF.; validation, CFM; formal analysis, CFM.; investigation, Valentin Fernandez.; resources, VF; data curation, LB; writing-original draft preparation, VF.; writing-review and editing, LB ; Supervision, CFM; project administration, VF; funding acquisition, CFM.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures were approved by the appropriate local ethics committee under authorization APAFIS n° 43824-2023061416402730 v4 and were conducted in accordance with European Union guidelines for animal research.

Data Availability Statement

Data and codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DLC |

DeepLabCut |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

PCK

mAP

FPS |

Percentage of Correct Keypoints

mean Average Precision

Frames Per Second |

References

- Mathis, A.; Mamidanna, P.; Cury, K.M.; Mathis, M.W.; Bethge, M.; Mathis, A. DeepLabCut: Markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1281-1289. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, C.P.; Campbell-Hope, L.J.; Pemberton, K.D.; Dunnett, S.B. The "staircase test": A measure of independent forelimb reaching and grasping abilities in rats. J. Neurosci. Methods 1991, 36, 219-228. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.D.; Moore, J.L.; Nunez, A.; Kells, A.P.; Peterson, S.M. Skilled reaching and grasping in mice: A new behavioral paradigm for cortical motor function. J. Neurosci. Methods 2019, 328, 108441. [CrossRef]

- Nath, T.; Mathis, A.; Chen, A.; Paterson, A.; Junyent, M.; Mathis, M.W. Using DeepLabCut for markerless pose estimation during behavior across species and environments. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1152-1170. [CrossRef]

- Madhusoodanan, Jyoti. “DeepLabCut: the motion-tracking tool that went viral.” Nature 629 (2024): 960 - 961. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:269929529.

- Bidgood, R., Zubelzu, M., Ruiz-Ortega, J.A. et al. Automated procedure to detect subtle motor alterations in the balance beam test in a mouse model of early Parkinson’s disease. Scientific Reports 14, 862 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019; Chaudhuri, K., Salakhutdinov, R., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Volume 97; PMLR: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 6105-6114. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016; pp. 770-778. [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.; Alahari, K.; Vedaldi, A. Human pose estimation from monocular images using deep learning. arXiv2014, arXiv:1409.1578. [CrossRef]

- Wiltschko, Alexander B. et al. Mapping Sub-Second Structure in Mouse Behavior Neuron, Volume 88, Issue 6, 1121 – 1135 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.031. PMID: 26687221; PMCID: PMC4708087.

- Balbinot, G.; Denize, S.; Lagace, D.C. The emergence of stereotyped kinematic synergies when mice reach to grasp following stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2022, 36, 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Vandaele, Y.; Mortelmans, S.; Van der Linden, A. Using DeepLabCut for automated assessment of motor behavior in rodent models of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021, 347, 109004. [CrossRef]

- Jessy Lauer, et al. Multi-animal pose estimation and tracking with DeepLabCut. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1347-1359. [CrossRef]

- 15.

- Suryanto, M.E.; Saputra, F.; Kurnia, K.A.; Vasquez, R.D.; Roldan, M.J.M.; Chen, K.H.-C.; Huang, J.-C.; Hsiao, C.-D. Using DeepLabCut as a real-time and markerless tool for cardiac physiology assessment in zebrafish. Biology2022, 11, 1243. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, F.; Hassan, A.; Kamel, S.M.; Al-Sharman, A.; Bairapareddy, K.; Arumugam, A.; Al Abdi, R.; Salem, Y.; Aboelnasr, E. Spatiotemporal kinematic parameters reflect spasticity level during forward reaching in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: Correlation and regression analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36137. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Pipeline for pose estimation using DeepLabCut. (a) Input dataset processing steps. (b) Output analysis steps.

Figure 1.

Pipeline for pose estimation using DeepLabCut. (a) Input dataset processing steps. (b) Output analysis steps.

Figure 2.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 2.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 3.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 3.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 4.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 4.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 5.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 5.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 6.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 6.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 7.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 7.

Details of metrics values for each CNN architecture. From left to right and from top to bottom: RMSE, PCK, mAP, Occlusion, FPS, VRAM.

Figure 8.

Normalized heatmap of all metrics (0 = worst ; 1 = best).

Figure 8.

Normalized heatmap of all metrics (0 = worst ; 1 = best).

Table 1.

Comparison of compared architectures regarding the state of the art.

Table 1.

Comparison of compared architectures regarding the state of the art.

| Model |

Type |

Key characteristics |

| ResNet-50 |

Standard deep residual network |

Common reference backbone in DeepLabCut; good compromise between speed and accuracy |

| ResNet-101 |

Deeper version of ResNet-50 |

Higher accuracy for complex postures; significantly higher computational cost |

| ResNet-152 |

Very deep, high-precision residual network |

Very high sensitivity to fine details; can outperform on micromovements but requires a powerful GPU and more memory; |

| MobileNetV2 |

Lightweight network using depthwise-separable convolutions |

Very low memory and computational load; suitable for modest GPUs or embedded systems, but less accurate for fine digit movements |

| EfficientNet-B0 |

Optimized compact network |

Excellent accuracy-to-parameter ratio; recommended for limited hardware resources |

| EfficientNet-B3 |

Larger and deeper version of EfficientNet |

Higher sensitivity to small digit micromovements; improved performance on fine joint localization |

| DLCRNet_ms5 |

Multi-scale DLC architecture |

Robust to occlusions, limb interactions, and complex movements |

| DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 |

Multi-scale DLCRNet variant with medium stride |

Improves accuracy across a wide range of movement amplitudes; strong accuracy–speed compromise |

| DLCRNet_stride32_ms5 |

Multi-scale DLCRNet variant with large stride |

Very fast but less precise; suitable for real-time analysis or constrained hardware |

Table 2.

Metrics values for each architecture of CNN.

Table 2.

Metrics values for each architecture of CNN.

| Architecture |

RMSE (px) |

PCK@5px (%) |

mAP (%) |

Robustesse Occlusion

(1–5)

|

FPS |

VRAM (GB) |

| ResNet-50 |

3.21 |

93.71 |

88.54 |

2.95 |

47 |

3.03 |

| ResNet-101 |

3.04 |

94.35 |

88.81 |

3.07 |

39 |

3.68 |

| ResNet-152 |

2.98 |

94.57 |

89.71 |

3.34 |

36 |

4.04 |

| MobileNetV2 |

3.58 |

90.70 |

85.63 |

2.33 |

74 |

2.64 |

| EfficientNet-B0 |

3.31 |

92.68 |

87.17 |

2.69 |

62 |

2.75 |

| EfficientNet-B3 |

3.04 |

94.78 |

88.75 |

3.25 |

51 |

3.27 |

| DLCRNet_ms5 |

2.80 |

95.90 |

91.07 |

4.80 |

33 |

5.26 |

| DLCRNet_stride16 |

3.11 |

94.39 |

89.14 |

3.44 |

36 |

3.88 |

| DLCRNet_stride16_ms5 |

2.93 |

95.15 |

90.84 |

4.13 |

34 |

4.87 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).