1. Introduction

The field of oncology has undergone rapid advancement in recent years. Both academic and industry-led research have provided people with a diagnosis of cancer more access to effective treatment options. Whilst this increase in available treatment options has been accompanied by an improvement in patient outcomes [

1,

2], the costs associated with these new treatments have also increased, limiting their availability and potential impact which has resulted in financial hardship for patients even in affluent countries [

3]. Annual global healthcare expenditure on pharmaceuticals is projected to exceed €2.2 trillion by 2028 [

4]. Of this expenditure, oncology medications are forecast to approach €400 billion per year over the same period [

5]. The situation in Ireland reflects this global trend. A recent report found that annual pharmaceutical expenditure in Ireland reached an all-time high of €2.54 billion in 2021 [

6]. Furthermore, a report conducted by the Health Service Executive (HSE) into pharmaceutical spending indicated that “high-tech drugs” and “high-cost drugs” (of which oncology medications are key members) were two of the leading causes of this increasing expenditure [

7].

Internationally, patients often bear much of the out-of-pocket costs of their cancer treatment [

8] and are therefore acutely aware of these costs. This differs to models employed in many European countries, e.g. Germany, the United Kingdom and Ireland, where medications are largely reimbursed by governmental bodies [

9]. In contrast, in Ireland, most oncology medications are subsidised under the Oncology Drugs Management System (ODMS), Primary Care Reimbursement Scheme (PCRS), local hospital budgeting or the Drug Payment Scheme. Under these programs, the maximum out-of-pocket cost for patients is capped at €80 per family per month [

10], even for drugs that may cost thousands of euros. This lessens the financial burden on individual patients and distributes the cost across society. Given that Irish patients are rarely exposed to the total costs of their treatment; their attitude towards growing prices remains unclear. Few existing studies have assessed patient attitudes towards the societal costs of cancer treatment [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

In 2009, the American Society of Clinical Oncology released a seminal guidance statement outlining the economic issues facing cancer care provision [

16]. In this statement patient-physician cost discussions were endorsed as an important element of high-quality care. The report also highlighted a paucity of research on the influence of societal costs on patient-physician communication. Despite this report being published over a decade ago, few studies have explored the relevance of societal costs to patient-physician communication. Instead, much existing research has focused on the direct out-of-pocket costs to patients [

17,

18,

19]. One of the few studies conducted in this area found a majority of patients believed the societal costs of cancer care were concerning [

20]. Despite these concerns, just 38% of participants indicated that they would like to discuss societal costs with their doctor. Another study found that over half of patients with a cancer diagnosis did not want their doctor to consider societal costs when making medical decisions [

21]. These studies may indicate that cancer patients generally do not wish to engage in societal cost discussions. However, it is important to note that these studies were conducted in the United States, a country which employs predominantly privately provided healthcare delivery.

Increasing oncology drug costs present a significant challenge to clinical practice and to the sustainability of healthcare which is particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries [

22]. Many methods have been proposed to reduce the growing costs of cancer care. The World Health Organisation, for example, has advocated for increased cost transparency to improve the affordability of cancer medications [

23]. Other proposed methods include the use of less expensive alternatives such as generics or “biosimilars”. Few studies have explored patient attitudes towards a broad variety of these cost reduction methods [

20]. Determining patient attitudes towards cost reduction methods may help to inform future policy discussions at national and international levels.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from July 1st and December 20th, 2024, in the breast cancer outpatient clinics at two university hospitals in the South of Ireland: Cork University Hospital (CUH) and The South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital (SIVUH). A three-part questionnaire was designed by the study authors to assess patient attitudes towards societal oncology medication costs and cost reduction methods. A copy of the questionnaire can be found in the supplementary documentation under

Figure S1. The study focused on patients with breast cancer to provide a homogeneous patient cohort.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had a diagnosis of breast cancer, were attending the breast cancer outpatient department and were aged > 18 years old. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, aged < 18 years old, had a cognitive impairment, were unable to read or write, those unable to complete the survey due to high burden of cancer symptoms/acute distress, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 3 or more, or those otherwise inappropriate to approach (in opinion of outpatient staff on day of appointment). Convenience sampling was used for questionnaire distribution. Consent was implied by completion and return of the questionnaire. Incomplete questionnaires were not included in the final analysis. Ethical approval was received from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals on the 12th of February 2024 (ECM 6 (a) 05/03/2024).

The first section of the questionnaire consisted of non-identifiable demographic questions adapted from previous studies [

20,

24]. The second section contained elements from an existing survey [

20] and inquired regarding general patient attitudes towards personal and societal oncology drug costs, using Likert scales. Patients were also asked to provide their views on potential methods to reduce the societal costs of oncology medications.

In the final section, the costs of eleven commonly prescribed breast cancer treatments, outlined in List 1 below, were presented to participants. Participants were first asked if they had been treated with any of the listed medications. They then indicated if the costs presented were more or less expensive than expected and finally, they indicated the acceptability of each cost. Participants were also asked about their overall views of the costs presented in the questionnaire. An explanation of the cost calculations for the costs used in the questionnaire can be found in the supplementary documentation under

Tables S1–S4.

List 1 – Drug List

Oral therapy: tamoxifen, anastrozole and palbociclib.

Intravenous Targeted and Immunotherapy: trastuzumab, pertuzumab, pembrolizumab and atezolizumab.

Chemotherapy: paclitaxel, doxorubicin, docetaxel and cyclophosphamide.

Data were compiled and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse demographic data, general and specific attitudes towards drug costs and drug cost reduction methods. Mann-Whitney U and Chi-square tests were used to investigate associations between participant characteristics and participant attitudes towards oncology drug costs as well as associations of patient desires to be better informed of the societal costs of their cancer treatment.

Participant characteristics investigated in the Mann-Whitney U and Chi-square tests included participant age, education level, annual household income, time from diagnosis, disease and use of expensive medications (defined as a cost > €10,000). Due to the limited research in this area the participant characteristics chosen by the study authors for investigation were selected as they were hypothesized theoretically to be relevant to patient cost acceptability and patient desires to discuss treatment costs. Characteristic selection was also informed by the available existing research16.

3. Results

Three hundred and twenty-one patients were offered the questionnaire, of these 180 fully completed the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 56.1%. Participant demographics are presented in

Table 1. Of the eleven medications presented in the questionnaire, the three most commonly prescribed were anastrozole 48.9% (N = 88/180), tamoxifen 47.2% (N = 85/180) and paclitaxel 15% (N = 27/180).

3.1. Attitudes Towards Societal Medication Costs

Fifty nine percent (N = 106/180) of participants indicated that they understood the societal costs of their treatment. Seventy three percent (N = 131/180) of patients indicated that they would like to be better informed about the societal costs of their cancer treatment. Eighty one percent (N = 146/180) believed that reducing the costs of cancer care to society is important.

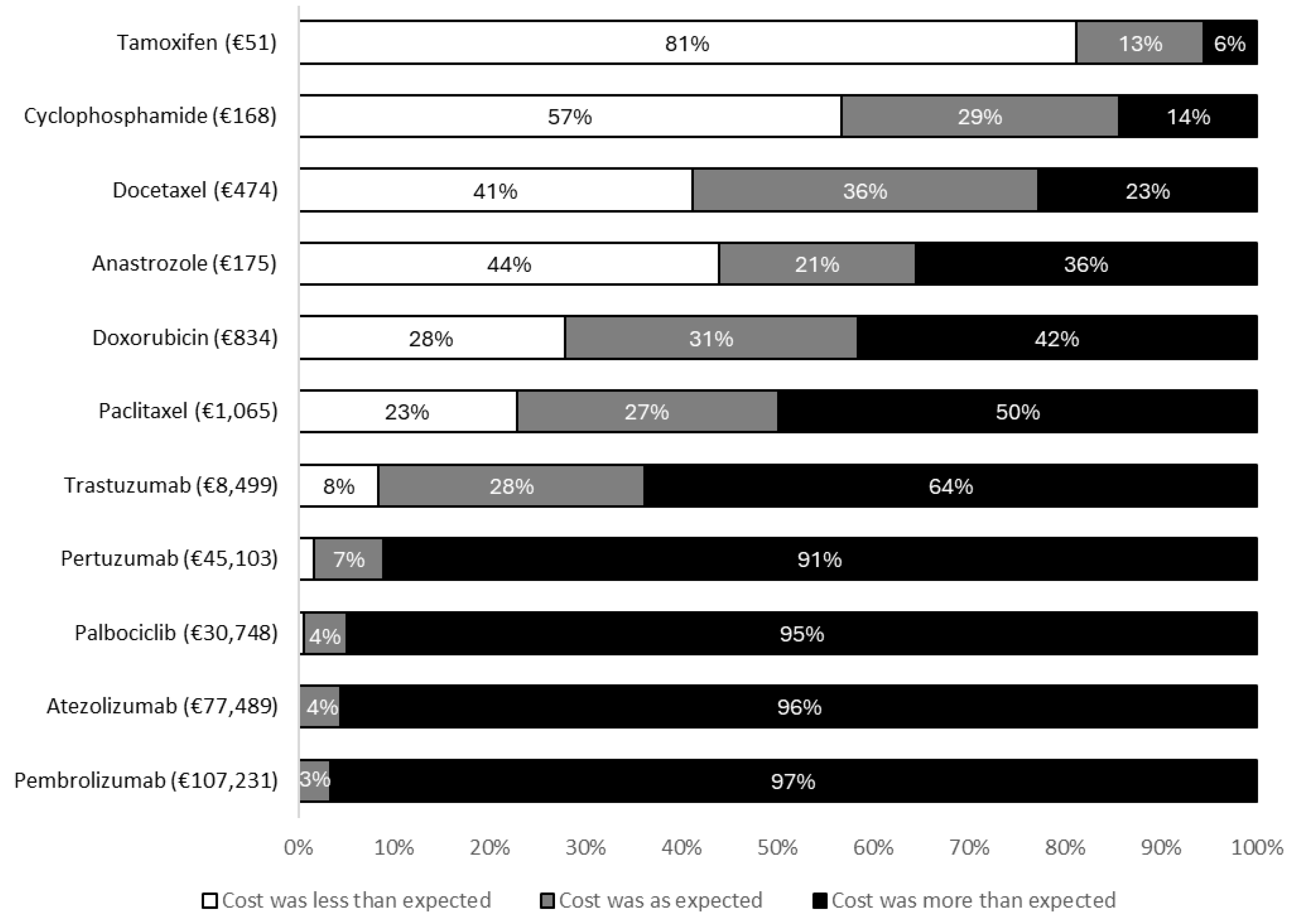

After viewing the costs in the questionnaire, 87.2% (N = 157/180) of patients reported being either surprised or very surprised by the prices presented. Eighty one percent (N = 146/180) believed the costs presented were higher than they had expected. The degree to which the prices presented in the questionnaire agreed with patient expectations are shown in

Figure 1.

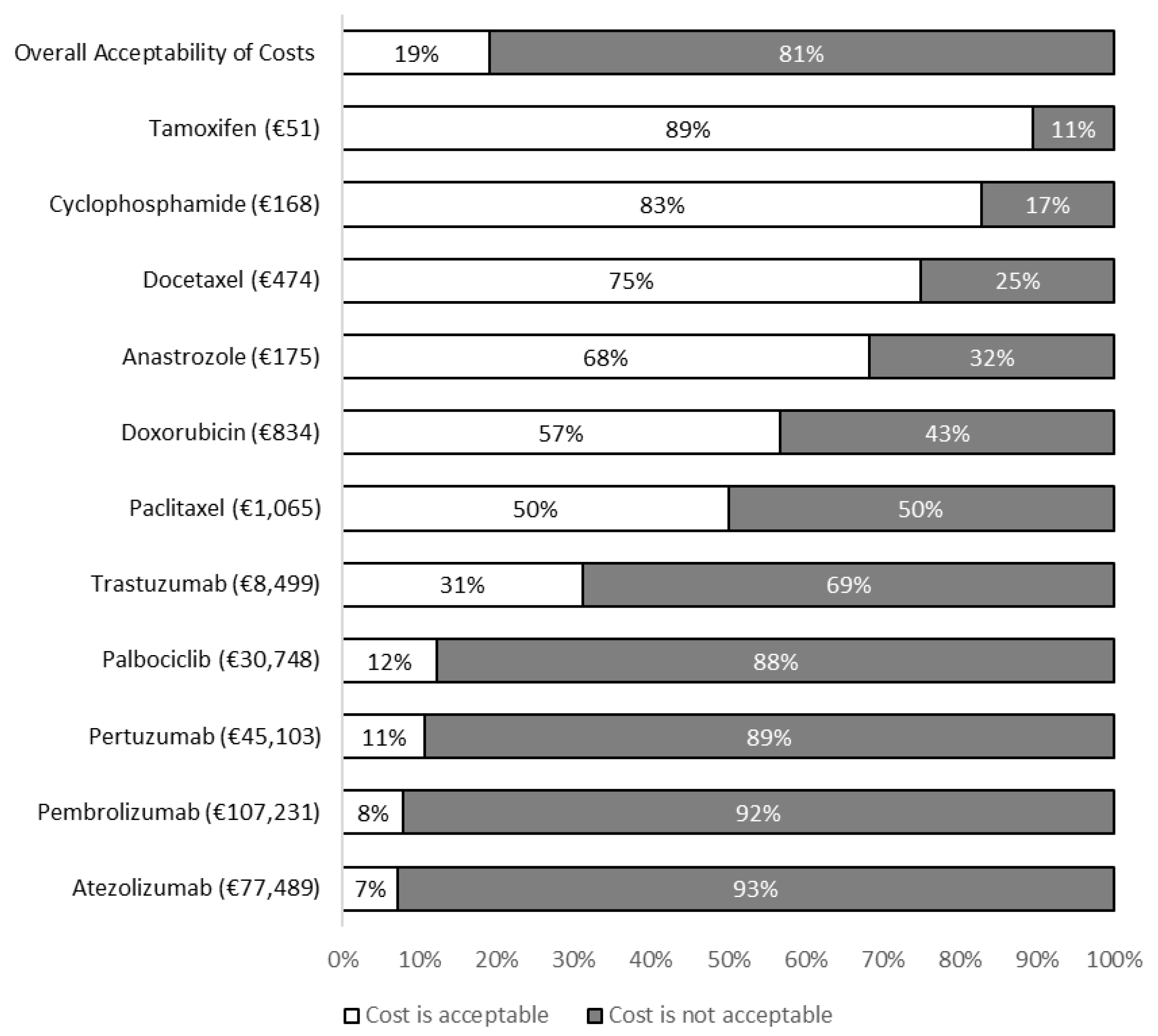

Nineteen percent (N = 35/180) of respondents believed that overall, the costs presented in the questionnaire were acceptable. The proportions of patients finding the costs presented in the questionnaire to be acceptable are presented in

Figure 2. Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine characteristics associated with patients identifying the costs presented in the questionnaire to be acceptable or unacceptable (

Table 2).

Table 3.

Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests for desire to be better informed of societal costs.

Table 3.

Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests for desire to be better informed of societal costs.

| |

Wish To Be Informed of Costs

N (%) |

Do Not Wish to be Informed of Costs

N (%) |

Test Statistic |

Degrees of Freedom |

p-value |

Age

Median (IQR) |

55 (49 – 63) |

54 (47.5 – 58.5) |

2938‡ |

- |

0.383 |

| Education |

|

|

|

|

|

| No Degree |

52 (39.7) |

9 (18.4) |

7.240† |

1 |

0.007 |

| Degree/diploma/certificate |

79 (60.3) |

40 (81.6) |

|

|

|

| Annual Household Income |

|

|

|

|

|

| < €50,000 |

80 (61.1) |

24 (49.0) |

2.136† |

1 |

0.144 |

| ≥ €50,000 |

51 (38.9) |

25 (51.0) |

|

|

|

| Time from Diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

| < 1 year |

23 (17.6) |

10 (20.4) |

0.607† |

2 |

0.738 |

| 1-5 years |

70 (53.4) |

23 (46.9) |

|

|

|

| > 5 years |

38 (29.0) |

16 (32.7) |

|

|

|

| Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

| Early stage |

122 (93.1) |

39 (79.6) |

6.923† |

1 |

0.009 |

| Metastatic |

9 (6.9) |

10 (20.4) |

|

|

|

| Use of Expensive Medications |

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

109 (83.2) |

41 (83.7) |

0.006† |

1 |

0.940 |

| Yes |

22 (16.8) |

8 (16.3) |

|

|

|

3.2. Attitudes Towards Societal Cost Reduction Methods

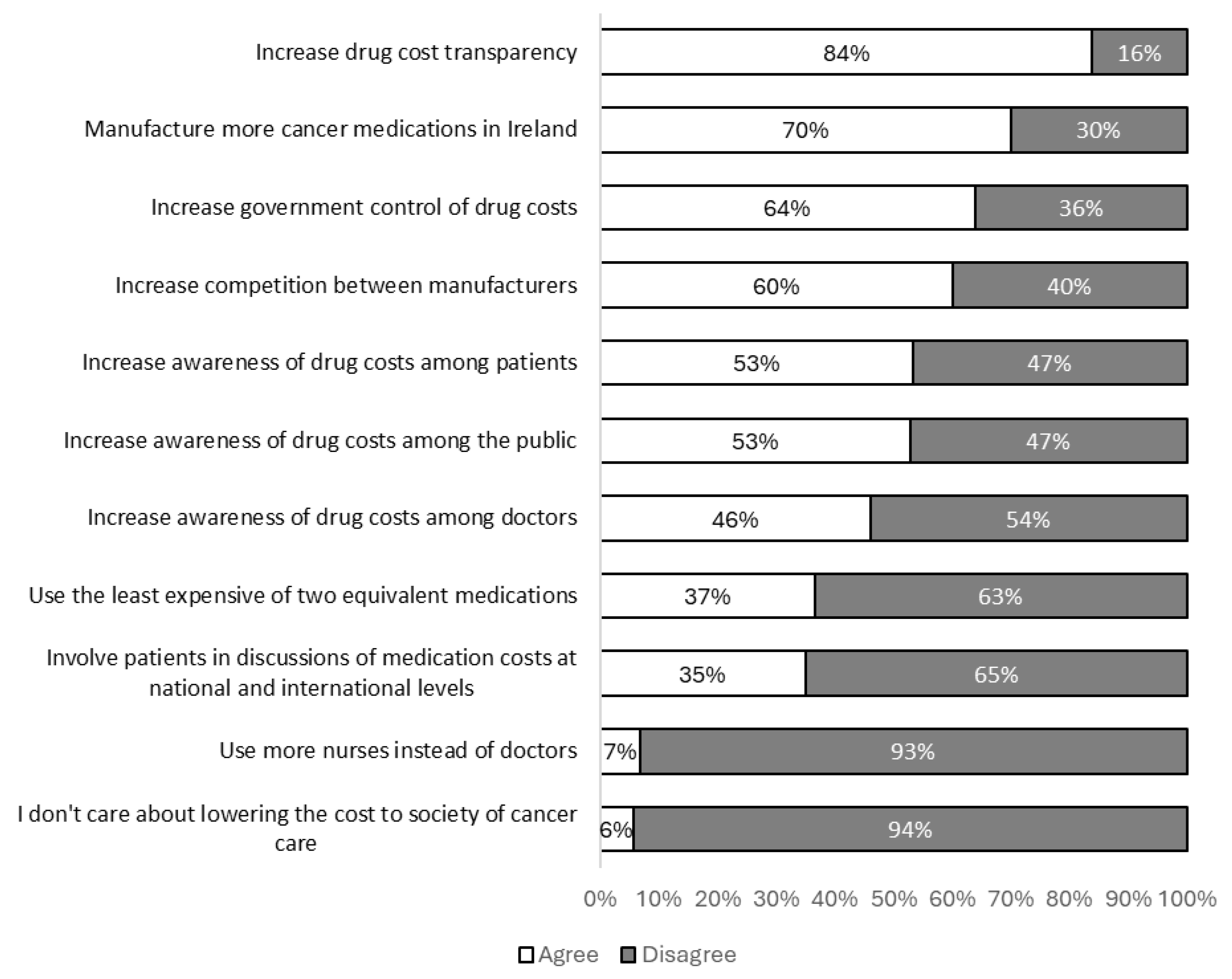

The most popular methods among participants to reduce the societal costs of cancer care were increased drug cost transparency, increased production of cancer medications in Ireland and increased governmental control of medication costs. Specific attitudes towards cost reduction methods are shown in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the attitudes of patients with breast cancer towards the societal costs of cancer care and societal cost reduction methods. Patients found the societal costs presented in the questionnaire to be surprisingly higher than expected. Many patients indicated a desire to be better informed of these costs. Statistical differences in patient desires to be informed of costs were observed between those with early stage and metastatic disease as well as those with a degree/certificate/diploma level education versus those without. Participants found many of the proposed cost reduction methods to be acceptable which adds to existing international work on potential cost reduction methods [

20,

25].

Fewer than one in five participants found the costs of the four most expensive medications in the questionnaire to be acceptable. In contrast, most patients found the costs of the four least expensive medications to be acceptable. The least expensive medications in the questionnaire were also generally the most commonly prescribed in the study population. These findings may indicate that it is the costs of an expensive, infrequently prescribed group of medications which patients find to be unacceptable.

This is one of the first studies of its kind which explicitly presents patients with real-world oncology drug costs to determine their attitudes. In one previous study conducted in the Netherlands, approximately 30% of patients with cancer believed that an annual cost of more than €240,000 was acceptable [

11]. In a large, multi-country study examining the costs that patients, the general population and caregivers deemed should be spent on treatment in exchange for an extra year of life, 40% of those in European Union countries indicated that up to €200,000 or more should be spent and 24% of those in the United States believed

$200,000 plus should be spent [

12]. One study conducted in the United States found that a quarter of breast cancer patients were willing to pay at least

$90,000 for a “hopeful gamble treatment” [

13]. In the context of this study a “hopeful gamble treatment” refers to a treatment which has a chance of increasing survival by a substantial amount. These findings are contrary to those of our study. Higher proportions of patients in our study found the costs of the most expensive medications to be unacceptable even when the costs were significantly lower than those described in international studies.

Two thirds of German patients with melanoma reported they were willing to spend up to €100,000 for the immunotherapy treatment ipilimumab [

14]. However, in the same study, when presented to patients in a societal context, participants chose to allocate €100,000 from health funds at a higher rate towards skin screening (46%) and primary prevention (46%) as compared to ipilimumab (4%). An additional German study also observed similar findings [

15]. When placing patients with melanoma in the hypothetical position of a treating physician, half of the patients opted to spend money on combination immunotherapy which could otherwise be used for prevention measures against cancer despite the high costs associated with combination immunotherapy. In contrast, when presented in a societal perspective, 73% of patients with melanoma favored spending €150’000 from the health fund on skin cancer screening for early cancer detection rather than on immunotherapy or palliative care. These findings indicate that patients with cancer may have different views towards healthcare costs at a societal level compared to an individual care level. The cost of the most expensive medication included in our study was approximately €110,000 per year and just 8% of our study participants found this cost to be acceptable. Taken together, these findings may explain the relatively lower rate of cost acceptability amongst participants in our study compared to the rates observed in other international studies.

Almost three quarters of patients indicated that they would like to be better informed of the societal costs of their cancer care. Our study also found a statistically significant difference in patient desires to be better informed of societal drug costs with respect to disease stage and education level. There was a higher proportion of patients with early-stage breast cancer who wished to be better informed of costs than those with metastatic disease. Therefore, if societal cost information were made available for patients, it may be more appropriate to provide it to those with early-stage disease. This differs from existing research which identified no association between patient desires to discuss societal costs with their doctor and stage of disease [

20]. It remains unclear how this information could be communicated to patients. Previous studies exploring patient attitudes of societal costs found that most patients do not want their doctor to discuss the societal costs of care with them or for their doctor to consider societal costs when making medical decisions [

20,

21,

26]. Interpreting our findings in this context may indicate that whilst patients do desire to be informed of societal costs, they do not wish for their doctor to provide this information. It is important to realise that these previous studies were conducted in the United States so any inferences or extrapolations should be made with caution. Furthermore, exploring the potential means by which such information could be communicated was not an aim of our study. Further cross-sectional research is needed to explore patient perspectives on how best to supply suitable patients with this information.

Over half of participants indicated that increasing cost awareness among patients could help reduce societal costs, however, just 35% of participants selected “involving patients in medication cost discussions at national or international levels” as a potential cost reduction method. This may indicate that whilst patients believe engagement with societal costs at an individual level is appropriate, they see little role for involvement at a collective policy making level.

A key strength of this study is its broad inclusion criteria. This enabled participants from broad socioeconomic backgrounds and patients at varying points in their disease trajectory to take part. Patients within one year of their diagnosis through to those almost 30 years from original diagnosis were included. Furthermore, participants with a variety of education levels participated in this study. A key limitation is the possibility of non-response bias. Reasons for non-response could include a high burden of disease or sociodemographic differences in participants. This study was conducted in the same setting as participants usual clinical care, and participants were recruited by their treating clinical team, therefore social desirability bias is difficult to exclude. The stability of social desirability bias has been previously shown to be influenced by educational history [

27] and this may partially account for the association between desiring to be better informed of drug costs and education.

The issue of increasing costs of innovative anticancer medications is a growing one that affects low-, middle- and high-income countries around the world to varying extents and can limit access to new and effective treatments. For example, in Morrocco 22 out of 39 innovative anticancer drugs that received market authorization were not reimbursed [

28]. The United States has many of the highest absolute costs of anticancer medications when compared to other countries. However, when accounting for per capitata spending power, anticancer drugs are least affordable in poorer countries for example India and China [

29]. The limited availability and affordability of anticancer drugs gives rise to substantial differences in cancer survival between high-income and low-and middle-income countries [

22]. As such it is necessary for future research to evaluate cost reduction methods such as those described in this paper and to identify novel techniques to improve patient access to innovative medications.

5. Conclusions

The rapidly growing costs of cancer care present a significant threat to the sustainability of healthcare systems. Our findings highlight that patients find many societal oncology medication costs to be unacceptable. Our results also indicate that reducing the societal costs of cancer treatment is important to many patients. Furthermore, we identified several cost reduction methods which were acceptable to a majority of patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Drug Cost Calculations - Intravenous Targeted and Immunotherapy; Table S2: Drug Cost Calculations - Oral Therapy; Table S3: Drug Cost Calculations - Chemotherapy; Table S4: Drug Cost Calculation Assumptions; Figure S1: Participant Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Matthew Cronin and Seamus O’Reilly; methodology, Matthew Cronin, Ruth Kieran, Katie Cooke, Clara Steele and Seamus O’Reilly; software, Matthew Cronin; validation, Matthew Cronin; formal analysis, Matthew Cronin; investigation, Matthew Cronin; resources, Matthew Cronin; data curation, Matthew Cronin; writing—original draft preparation, Matthew Cronin; writing—review and editing, Matthew Cronin, Ruth Kieran, Clara Steele and Seamus O’Reilly; visualization, Matthew Cronin; supervision, Seamus O’Reilly; project administration, Matthew Cronin; funding acquisition, Matthew Cronin and Seamus O’Reilly. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Matthew Cronin received a Summer Undergraduate Research Experience (SURE) award to conduct this project (value of €2,400, cost code: 3480 AM1125). The awarding institution was University College Cork School of Medicine and Health, Brookfield Health Sciences Complex, College Road, Cork. This study also received the Pamela Gilligan prize at University College Cork (value of €500). This study was also partially responsible for the receipt of the P. Fitzpatrick Prize in Epidemiology & Public Health Medicine at University College Cork (value of €400).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number for this study can be found below as well as a statement granting an amendment to the original ethical approval application. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (protocol code: ECM 6 (a) 05/03/2024 and date of approval: 12th February 2024). An amendment was also granted by the Ethics Committee of The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (amendment code: ECM 3 (q) 30/07/2024 and date of approval of amendment: 25th July 2024). The amendment added two additional recruitment sites, namely South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital, Cork City, Cork, Ireland and the Consultants Private Clinic, Cork City, Cork, Ireland. No patients were ultimately recruited from Consultants Private Clinic.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were supplied with documentation explaining the rationale and aims of the project as well as how any data collected would be used (including publication). Consent was implied by completion and return of the questionnaire. This method of consent was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of commitments made in the original ethical approval request which prohibits sharing of the data for use by those outside of the study authors. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Matthew Cronin.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank all those patients who participated in this study, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The Summer Undergraduate Research Experience (SURE) prize awarded to Matthew Cronin provided a bursary to allow him to undertake this research project full time for a period from 20/05/2024 - 28/06/2024. All other conflicts of interest other than those listed above are as follows: Matthew Cronin: none; Ruth Kieran: none; Katie Cooke: Bristol Myers Squibb Survey; Clara Steele: none; Seamus O’Reilly: Travel Novartis, Merck, Daichi Sankyo; Honoraria Astra Zeneca.

References

- Li, M; Ka, D; Chen, Q. Disparities in availability of new cancer drugs worldwide: 1990-2022. BMJ Glob Health [Internet] 2024, 9(9), e015700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell-Jin, JL; Sun, LP; Munoz, D; Lu, Y; Li, Y; Huang, H; Hampton, JM; Song, J; Jayasekera, J; Schechter, C; Alagoz, O; Stout, NK; Trentham-Dietz, A; Lee, SJ; Huang, X; Mandelblatt, JS; Berry, DA; Kurian, AW; Plevritis, SK. Analysis of Breast Cancer Mortality in the US-1975 to 2019. JAMA [Internet] 2024, 331(3), 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, S; Luis, IV; Adam, V; Razis, ED; Urruticoechea, A; Arahmani, A; Carrasco, E; Chua, BH; Bliss, J; Straehle, C; Goulioti, T; Lindholm, B; Werustsky, G; Brain, E; Bedard, PL; Curigliano, G; Loi, S; Saji, S; Cameron, D. Advancing equitable access to innovation in breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2025, 11(1), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- The IQVIA Institute. The Global Use of Medicines 2024: Outlook to 2028; The IQVIA Institute: United States, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The IQVIA Institute. Global Oncology Trends 2024: Outlook to 2028; The IQVIA Institute: United States, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, S. Review of High-Tech Drug Expenditure. Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. 2021. Available online: https://igees.gov.ie/.

- Connors, J. Health budget oversight and management: alignment of health budget and national service plan. Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. 2018. Available online: http://www.budget.gov.ie/.

- Agarwal, A; Livingstone, A; Karikios, DJ; Stockler, MR; Beale, PJ; Morton, RL. Physician-patient communication of costs and financial burden of cancer and its treatment: a systematic review of clinical guidelines. BMC Cancer [Internet] 2021, 21(1), 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panteli, D; Arickx, F; Cleemput, I; Dedet, G; Eckhardt, H; Fogarty, E; Gerkens, S; Henschke, C; Hislop, J; Jommi, C; Kaitelidou, D; Kawalec, P; Keskimaki, I; Kroneman, M; Lopez Bastida, J; Pita Barros, P; Ramsberg, J; Schneider, P; Spillane, S; Vogler, S; Vuorenkoski, L; Wallach Kildemoes, H; Wouters, O; Busse, R. Pharmaceutical regulation in 15 European countries review. Health Syst Transit [Internet] 2016, 18(5), 1–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Health Service Executive. Drugs Payment Scheme. [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www2.hse.ie/services/schemes-allowances/drugs-payment-scheme/card/.

- van Dijk, EF; Coşkuntürk, M; Zuur, AT; van der Palen, J; van der Graaf, WT; Timmer-Bonte, JN; Wymenga, AN. Willingness to accept chemotherapy and attitudes towards costs of cancer treatment; A multisite survey study in the Netherlands. Neth J Med [Internet] 2016, 74(7), 292–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ramers-Verhoeven, CW; Geipel, GL; Howie, M. New insights into public perceptions of cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2013, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lakdawalla, DN; Romley, JA; Sanchez, Y; Maclean, JR; Penrod, JR; Philipson, T. How cancer patients value hope and the implications for cost-effectiveness assessments of high-cost cancer therapies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012, 31(4), 676–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, R; Heinzerling, L. Therapy preferences in melanoma treatment--willingness to pay and preference of quality versus length of life of patients, physicians and healthy controls. PLoS One 2014, 9(11), e111237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weiss, J; Kirchberger, MC; Heinzerling, L. Therapy preferences in melanoma treatment-Willingness to pay and preference of quality versus length of life of patients, physicians, healthy individuals and physicians with oncological disease. Cancer Med 2020, 9(17), 6132–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meropol, NJ; Schrag, D; Smith, TJ; Mulvey, TM; Langdon, RM, Jr.; Blum, D; Ubel, PA; Schnipper, LE; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol [Internet] 2009, 27(23), 3868–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, SY; Chino, F; Ubel, PA; Rushing, C; Samsa, G; Altomare, I; Nicolla, J; Schrag, D; Tulsky, JA; Abernethy, AP; Peppercorn, JM. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care [Internet] 2015, 21(9), 607–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, A; Zheng, Z; Zhao, J; de Moor, JS; Ekwueme, DU; Yabroff, KR. Patient-Provider Discussions About Out-of-Pocket Costs of Cancer Care in the U.S. Am J Prev Med [Internet] 2020, 59(2), 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, AB; Nipp, RD; Hasler, JS; Hu, BY; Zahner, GJ; Robbins, S; Wheeler, SB; Tagai, EK; Miller, SM; Peppercorn, JM. National survey of patient perspectives on cost discussions among recipients of copay assistance. Oncologist [Internet] 2024, 29(11), e1540–e1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, B; Kimmick, G; Altomare, I; Marcom, PK; Houck, K; Zafar, SY; Peppercorn, J. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care. Oncologist [Internet] 2014, 19(11), 1135–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, AJ; Hofstatter, EW; Yushak, ML; Buss, MK. Understanding patients' attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract [Internet] 2012, 8(4), e50-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, P; Okediji, RL; Mulema, V; Cliff, ERS; Asante-Shongwe, K; Bychkovsky, BL; Fadelu, T. Advancing Global Pharmacoequity in Oncology. JAMA Oncol Erratum in: JAMA Oncol. 2025 May 1;11(5):570. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2025.0822. PMID: 39541207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.02.017. 2025, 11(1), 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Pricing of cancer medicines and its impacts; Geneva, 2018; p. xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C; Harrington, JM. Seamus O’Reilly. Secondary risk reduction service acceptability amongst Irish breast cancer survivors and clinicians. European journal of public health [Internet] 2023, 33 (Supplement_2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieran, R; Coakley, K; Macanovic, B; Weadick, C; Keogh, R; Cooke, K; Allen, M; Higgins, M; O'Reilly, S. Cutting waste in cancer care: acceptability of novel waste-reduction strategies in oral therapies amongst Irish oncology stakeholders. Ir J Med Sci Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisenberg, BR; Varner, A; Ellis, E; Ebner, S; Moxley, J; Siegrist, E; Weng, D. Patient Attitudes Regarding the Cost of Illness in Cancer Care. Oncologist 2015, 20(10), 1199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haberecht, K; Schnuerer, I; Gaertner, B; John, U; Freyer-Adam, J. The Stability of Social Desirability: A Latent Change Analysis. J Pers. 2015, 83(4), 404–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhima, N; Afani, L; Fadli, ME; Essâdi, I; Belbaraka, R. Investigating the availability, affordability, and market dynamics of innovative oncology drugs in Morocco: an original report. Int J Equity Health 2024, 23(1), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prasad, V; De Jesús, K; Mailankody, S. The high price of anticancer drugs: origins, implications, barriers, solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017, 14(6), 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digital Medicines Information Suite [Internet]. MedicinesComplete. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_159392432?hspl=breast&hspl=cancer.

- MedicinesComplete — Log in [Internet]. www.medicinescomplete.com. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_988968089?hspl=pembrolizumab.

- MedicinesComplete — Log in [Internet]. www.medicinescomplete.com. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_938546664?hspl=doxorubicin.

- MedicinesComplete — Log in [Internet]. www.medicinescomplete.com. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_904039742?hspl=docetaxel.

- Health Service Executive. Cancer Drugs Approved for Reimbursement. [Internet] Dublin. Health Service

Executive: National Cancer Control Program. [updated 2023 Sep 04]. Available from: Cancer Drugs

Approved for Reimbursement - HSE.ie.

- NCCP National SACT Regimen [Internet]. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/chemoprotocols/breast/316-dose-dense-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide-ac-60-600-14-day-followed-by-paclitaxel-175-14-day-and-trastuzumab-therapy-dd-ac-th-.pdf.

- Simoens, S; Vulto, AG; Dylst, P. Simulating Costs of Intravenous Biosimilar Trastuzumab vs. Subcutaneous Reference Trastuzumab in Adjuvant HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: A Belgian Case Study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) [Internet] 2021, 14(5), 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics; Ireland. Cost Effectiveness of Pertuzumab (Perjeta®) in Combination with Trastuzumab and Docetaxel in Adults with HER2-Positive Metastatic or Locally Recurrent Unresectable Breast Cancer Who Have Not Received Previous Anti-HER2 Therapy or Chemotherapy; National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics, Ireland: Dublin, Aug 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association. Price Realignment File for Implementation on 1 March 2023.

Dublin: Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association; 2023 Mar.

- TAMOX: [Internet]. MIMS Ireland; Available from; TAMOX:: MIMS Ireland.

- AMIDEX: [Internet]. MIMS Ireland; Available from; AMIDEX:: MIMS Ireland.

- DOXORUBICIN: [Internet]. MIMS Ireland; Available from; DOXORUBICIN:: MIMS Ireland.

- ENDOXANA: [Internet]. MIMS Ireland; Available from; ENDOXANA:: MIMS Ireland.

- Digital Medicines Information Suite [Internet]. MedicinesComplete. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_465902208?hspl=paclitaxel.

- D’Arpino, A; Savoia, M; Cirillo, L; Despiégel, N; Haffemayer, B; Giannopoulou, A; et al. PCN72 COMPARATIVE COST ANALYSIS OF SUBCUTANEOUS TRASTUZUMAB ORIGINATOR (HERCEPTIN®) VS INTRAVENOUS TRASTUZUMAB BIOSIMILAR (KANJINTI) FROM A HOSPITAL PERSPECTIVE IN ITALY. Value in Health 2019, 22, S449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Service Executive. HSE – PRIMARY CARE REIMBURSEMENT SERVICE UPDATE TO LIST OF AGREED PRESCRIBABLE MEDICINAL PRODUCTS TO BE DISPENSED UNDER THE HIGH TECH SCHEME EFFECTIVE; Health Service Executive: Dublin, Mar 2022; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, B; Keane, M. NCCP National SACT Regimen [Internet]. 2015. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/chemoprotocols/breast/204-pertuzumab-and-trastuzumab-and-docetaxel-therapy-21-day-cycle.pdf.

- NCCP Chemotherapy Regimen NCCP Regimen: Atezolizumab and nab- paclitaxel Therapy [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/chemoprotocols/breast/688.pdf.

- MedicinesComplete — Log in [Internet]. www.medicinescomplete.com. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/29515-q?hspl=pembrolizumab.

- MedicinesComplete — Log in [Internet]. www.medicinescomplete.com. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/14549-q?hspl=Anastrozole.

- MedicinesComplete — Log in [Internet]. www.medicinescomplete.com. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/29584-x?hspl=palbociclib.

- NCCP Chemotherapy Regimen NCCP Regimen: DOCEtaxel and Cyclophosphamide Therapy-21 day [Internet]. 2015. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/chemoprotocols/breast/250-docetaxel-cyclophosphamide-tc-therapy-21-day.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |