1. Introduction

Photovoltaic (PV) deployment has expanded rapidly worldwide, with the volume of end-of-life (EoL) modules requiring collection, safe handling, and recycling. Projections by the IRENA and IEA- PVPS highlight that PV module waste may reach millions of tonnes by 2030 and tens of millions of tonnes by the middle-century under different “regular- loss” and “early- loss” scenarios, making EoL management a central sustainability challenge and a potential resource- recovery opportunity (glass, aluminum, silicon, silver, and other metals) [

1].

In the European Union (EU), PV panels are covered under the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) framework, which establishes obligations for separate collection and treatment and supports extended producer responsibility [

2]. In practice, however, logistics and economics remain challenging, especially for dispersed waste streams, damaged laminates, and low-value fractions (e.g., polymeric backsheets and encapsulants). The IEA-PVPS has documented that PV module recycling technologies and routes are evolving but remain constrained by the complexity of laminated module structures and the difficulty of economically separating and valorizing materials at high quality [

3].

Moreover, agrivoltaics (APVs) are promoted as a sustainable solution, enabling the dual use of land for energy and agricultural production [

4]. Evidence from drylands shows that agrivoltaics can provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus when appropriately designed and managed [

5]. However, PV structures can reshape the microclimate and redistribute rainfall—concentrating runoff at drip lines while sheltering areas beneath panels—effects that can be beneficial or harmful depending on vegetation cover and stormwater management [

6,

7,

8].

Soil protection is a key sustainability dimension for PVs located on agricultural land. The loss of permeable surfaces (“soil sealing”) is widely recognized as a driver of increased runoff, reduced infiltration, and altered hydrological response; EU guidance documents emphasize limiting and mitigating soil-sealing effects [

9]. Impervious surface coverage has long been treated as a core environmental indicator because it is correlated with watershed impacts and landscape function [

10]. Even small sealed or vegetation-suppressed patches can matter locally when they persist for years and create zones of concentrated flow or bare soil susceptible to erosion processes; erosion frameworks emphasize the role of cover and runoff concentration [

11].

PV module failures—and the resulting replacement or repowering cycles—are central drivers of EoL flows. A detailed IEA-PVPS Task 13 synthesis summarizes field failure mechanisms across manufacturing, transport, installation, and exposure conditions [

12]. Importantly, long-term monitoring under moderate climates has shown that some “first-tier” PV panels can begin to fail substantially earlier than the often-reported 25-year lifetime—on the order of 10–12 years—with practical implications for repowering and service costs [

13]. These timescales align with the repowering timeline of many early utility-scale plants built in Central Europe from approximately 2009–2010.

Research gap. While the PV waste literature extensively addresses global mass flows, recycling technologies, and circular-economic frameworks, there is limited field-based quantification of a specific but increasingly observed practice: on-site storage of damaged/decommissioned PV modules directly on agricultural soil (e.g., stacked on grassland within the PV parcel) following repowering. Such storage can persist due to economic barriers, contractual constraints, and logistical friction, yet land-occupation and stewardship impacts are rarely reported via reproducible metrics.

Aim and contribution. This brief report provides two anonymized case studies from Czechia to (i) quantify the land area, PV panel area, and stored PV module area via GIS/orthophoto interpretation supported by field photographs; (ii) estimate the number and mass of stored modules from observable stacks and the literature- consistent with module mass ranges; and (iii) discuss sustainability implications and propose practical reporting indicators supporting improved EoL management of agricultural land.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Case Study Sites and Anonymization

Two ground-mounted PV power plants in Czechia were selected on the basis of repeated observations of damaged module storage on agricultural land within plant parcels. Because the authors do not have explicit permission from plant/land owners to disclose precise locations, both sites are anonymized and presented as Locality 1 (L1) and Locality 2 (L2).

Locality 1 (L1): Commissioned 2010; nominal installed capacity 0.861 MWp; repowered 2022; land area: 19,560 m².

Locality 2 (L2): Commissioned 2009; nominal installed capacity 1.109 MWp; repowered 2021; land area: 22,100 m².

2.2. Field Observations and Photographic Documentation

Both sites were visited and photographed. The stored modules were visibly damaged (e.g., cracked backsheets and/or broken front glass). Modules were stored on-site, stacked in piles and placed within accessible parts of the parcel and along fencing.

Figure 1.

Representative anonymized field photographs showing stacked storage of damaged PV modules on grass/soil and the resulting vegetation suppression beneath and adjacent to the stacks.

Figure 1.

Representative anonymized field photographs showing stacked storage of damaged PV modules on grass/soil and the resulting vegetation suppression beneath and adjacent to the stacks.

2.3. GIS/Orthophoto Mapping of Land Occupation

Orthophoto imagery was used as a basis for GIS delineation [

14].

The land-occupation metrics were derived via orthophoto--based GIS interpretation. We delineated three plan-view (projected) areas:

- (i)

Land area (Aland, m²): total land parcel area of the PV plant;

- (ii)

PV panel area (APV, m²): plan-view (projected) area occupied by PV panel rows/tables visible in the orthophoto;

- (iii)

stored PV module area (Astore, m²): plan-view storage footprint occupied by stored PV modules placed directly on soil/grass.

These areas represent 2D projected footprints and do not capture 3D stacking heights; however, they represent the soil surface area directly covered and rendered unavailable for vegetation management.

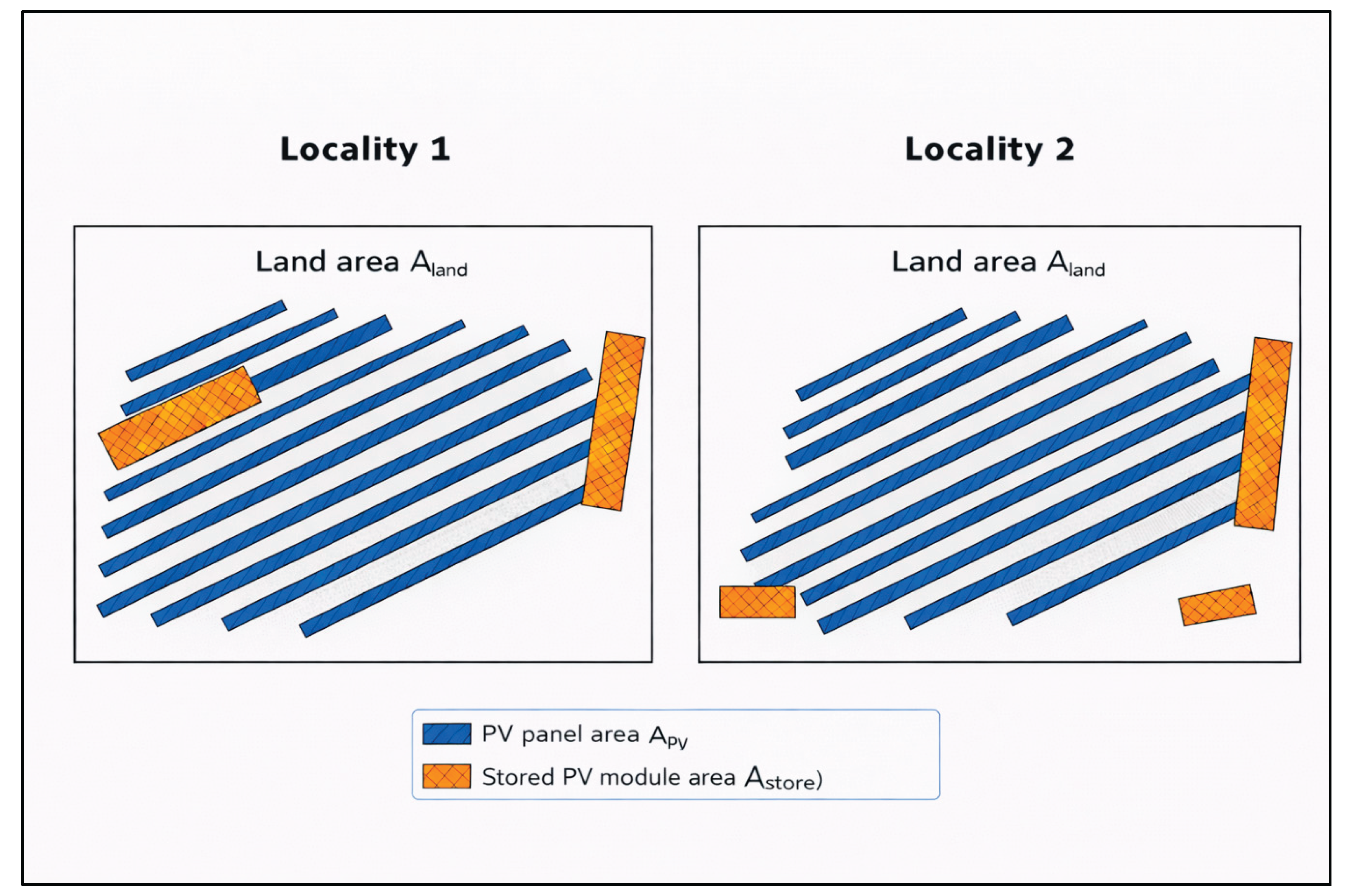

Figure 2.

Schematic GIS delineation of the PV panel area (APV) and stored PV module area (Astore) at Locality 1 and Locality 2 (anonymized; polygons and annotations by the authors; orthophoto referenced in GIS analysis).

Figure 2.

Schematic GIS delineation of the PV panel area (APV) and stored PV module area (Astore) at Locality 1 and Locality 2 (anonymized; polygons and annotations by the authors; orthophoto referenced in GIS analysis).

2.4. Estimation of Stored Module Counts

Module counts were estimated from orthophoto interpretations supported by field photographs. Because modules were stored in visible piles with discernible stack arrangements, counts were estimated by (i) counting stacks/piles and their approximate base dimensions; (ii) estimating the number of modules per stack from visible edges and stack height; and (iii) cross-checking totals against the storage footprint.

Estimated counts:

2.5. Estimation of Stored Mass

The PV module mass varies by technology, size, and frame/glass thickness. To reflect variability across manufacturers and module generations while remaining conservative, we used a mass range:

consistent with typical crystalline-silicon module examples reported in PV EoL syntheses [

1]. The stored mass was estimated as follows:

2.6. Context: Recycling Economics and Barriers (Literature-Based)

Economic barriers to timely removal can be linked to the treatment and transport costs discussed in the techno-economic and LCA literature. For contextualization (order of magnitude), we refer to the IEA-PVPS Task 12 LCA reporting on PV recycling and treatment assumptions [

15]. These values are used for qualitative interpretation only; site-specific contractual costs were not available.

3. Results

3.1. Land Area, PV Panel Area, and Stored PV Module Area

Table 1 summarizes the key site characteristics and plan-view land- occupation metrics.

Although

Astore represents <1% of

the land area (Aland), stored modules occupy specific locations that become persistently inaccessible for mowing and vegetation maintenance, leading to degraded grass cover beneath and adjacent to stacks (

Figure 1).

3.2. Mass of Stored PV Modules

Using 18–25 kg/module [

1], the stored masses are as follows:

Normalized by the nominal capacity:

L1: 37.6–52.3 t/MWp

L2: 32.5–45.1 t/MWp

3.3. Derived Indicators: Footprint Efficiency and Surface Loading

Stacking compresses large module counts into compact plan- view footprints. The effective storage footprint per stored module is as follows:

Combining the footprint and mass yields an implied surface loading at the storage footprint:

These indicators demonstrate that even a small storage footprint can correspond to tens of tonnes of material resting directly on agricultural soil.

3.4. Evidence of Early Replacement Context

Both sites were commissioned from 2009–2010 and repowered from 2021–2022 (≈11–13 years after commissioning). This interval is consistent with published field evidence that some first-tier PV panels in moderate climates can begin to fail substantially earlier than the nominal 25-year lifetime, with practical consequences for repowering and service costs [

13]. This observation aligns with broader failure mechanisms summarized by IEA-PVPS Task 13 [

12] and supports the interpretation that accelerated replacement cycles can generate significantly damaged-module streams earlier than often assumed.

4. Discussion

4.1. Why On-Site Storage on Agricultural Land is a Sustainability Issue

On-site storage of damaged PV modules directly on agricultural soil introduces several sustainability impacts that are not captured when the PV EoL is discussed purely as a recycling-plant problem.

Land occupation and vegetation suppression. When stacks rest on grasslands, the vegetation beneath them is physically suppressed and often degrades into anaerobic patches or bare soil. Functionally, this resembles the soil-sealing effects (loss of soil functions at the footprint) discussed in soil-sealing guidance [

9]. While A

store accounts for <1% of the land area (A

land), it can persist for months/years and is spatially concentrated.

Water and erosion relevance (qualitative, not modeled). By covering soil and suppressing vegetation at the storage footprint, on-site module piles likely reduce local soil functions (including infiltration capacity) and may promote edge runoff concentration during storm events. PV structures can redistribute rainfall through sheltering and runoff concentrations [

6,

7,

8], and erosion sensitivity to cover and flow concentrations is well recognized in erosion frameworks [

11]. We did not quantify the hydrological response or erosion rates; nevertheless, the mechanism reinforces why prolonged storage on soil is undesirable.

Contradiction with agrivoltaic narratives. Agrivoltaics is framed as a dual-use sustainability approach [

4,

5]. Leaving damaged modules on fields undermines this narrative by creating unmanaged “dead zones” within agricultural parcels and increasing land-stewardship burdens.

4.2. Regulatory Context and the Practice–Policy Gap

The EU WEEE policy frames PV modules within regulated waste streams and producer responsibility [

2]. However, the observed practice—long-term on-site storage on agricultural land—suggests a practice–policy gap likely driven by (i) transaction costs and logistics (collection coordination, documentation, and access to certified treatment); (ii) economic misalignment where deferral is less expensive than timely removal; and (iii) limited enforcement capacity relative to the number of dispersed PV sites.

IEA-PVPS notes that recycling routes for crystalline- silicon modules can be constrained by material separation difficulties and by the polymeric fraction [

3]. These technical constraints translate into economic barriers, which can incentivize local buffering of waste at the PV site itself.

4.3. Economic Barriers: Why Storage Can Appear Rational to Operators

Techno-economic and circular-economic studies emphasize that collection, transport, and processing costs can dominate EoL economics when recovery values are low or volatile [

16,

17,

18]. LCA-oriented PV recycling work further indicates that logistics and treatment assumptions strongly influence net impacts and feasibility [

15,

19,

20].

In this context, storing damaged modules on-site can become the de facto operator strategy when (i) unit collection is inefficient; (ii) minimum batch sizes are economically preferred by treatment routes; and (iii) the immediate cost of removal is not clearly internalized or reimbursed through producer-responsibility mechanisms. The sustainability problem is that deferral shifts burdens from the waste system to the land system—creating unpriced externalities (soil function loss at Astore, visual pollution, and potential environmental risk).

4.4. Circular-Economic Perspective and Design-for-Recycling

Circular-economic framing for PVs emphasizes high recovery of glass and metals and improved recovery of silicon and silver [

1,

20]. However, reviews highlight persistent challenges: separation of encapsulant/backsheet polymers, contamination of glass streams, heterogeneity of module designs across generations, and economics of recovering low-mass high-value metals [

16,

19,

21,

22,

23]. Research increasingly focuses on improving polymer separation and recovery [

23] and on alternative design/recycling concepts aimed at facilitating disassembly and circularity. For example, Poulek et al. proposed a recycling--oriented module lamination concept using soft polysiloxane gels to facilitate separation and reduce EoL burdens [

24]. While such approaches are not yet mainstream, they illustrate how design-for-recycling could reduce incentives to store damaged modules on agricultural land.

4.5. Environmental Risk Beyond Land Use: Leaching and Toxicity Context

This manuscript does not present soil chemistry measurements. Nevertheless, the broader literature indicates that damaged modules—especially crushed or weathered fragments—can release metals depending on conditions (e.g., pH and exposure time), and toxicity assessment remains an active research area [

25]. A European Commission study prepared during WEEE recast impact assessment discussed leaching behavior and emphasized the importance of proper treatment routes [

26]. Independent studies have also addressed the potential leaching of heavy metals/metalloids from crystalline-silicon PV systems under certain scenarios [

27]. This does not imply contamination at the studied sites; rather, it supports a precautionary sustainability argument: storing broken modules outdoors on agricultural soil is not aligned with best practices when regulated treatment routes exist.

4.6. Scaling and Monitoring: Why Simple Indicators Matter

The two sites in this study store ~3800 modules on 209 m², corresponding to ~68–95 t of material on agricultural soil. As PV deployment expands and repowering accelerates, early-loss scenarios suggest increasing EoL streams [

1]. If replacement cycles shorten toward 10–15 years (as field reliability observations may imply for some module populations in specific contexts) [

13], the frequency of damaged-module streams could increase.

A practical response is to standardize minimum indicators that can be collected cheaply and compared across sites and countries. Remote sensing and orthophoto-based monitoring are increasingly central to environmental monitoring frameworks [

28] and can support scalable reporting of A

store, vegetation conditions, and changes over time.

4.7. Simple Projection for a Second Repowering Cycle (Persistence Scenario)

The observed onsite module piles represent the outcome of the first repowering cycle. If the currently stored modules remain onsite until a subsequent repowering event and an additional wave of damaged/decommissioned modules is generated, cumulative storage on agricultural land may increase. To illustrate the potential magnitude transparently, we define a simple persistence scenario assuming the following: (i) the next repowering produces approximately the same number of damaged modules as currently stored (ΔNstore ≈ Nstore), and (ii) the new modules are stored with a similar plan-view stacking density (i.e., comparable Astore per module) as that observed in this study. Under these assumptions, the cumulative storage indicators would approximately double.

For

Locality 1, A

store would increase from

109 to ~218 m² (≈

1.12% of land area), N

store would increase from

~1,800 to ~3,600 modules, and Mstore would increase from

~32.4–45.0 to ~64.8–90.0 t (18–25 kg/module). For

Locality 2, A

store would increase from

100 to ~200 m² (≈

0.91% of the land area), N

store would increase from

~2,000 to ~4,000 modules, and M

store would increase from

~36.0–50.0 to ~72.0–100.0 t. Across both sites, cumulative onsite storage would reach

~418 m² and

~7,600 modules (≈

136.8–190.0 t) stored on agricultural soil. Although the projected fractions remain near ~1% of the land area, the sustainability concern is the

persistence and repetition of unmanaged storage patches on farmland. Moreover, if operators avoid footprint expansion by stacking vertically on the same footprint, the land area impact may not increase proportionally, but

surface loading and handling risks would increase. This scenario reinforces the need for time-bound onsite storage rules and reporting indicators aligned with WEEE objectives and early-loss waste projections. [

1,

2,

13]

4.8. Practical reporting indicators (submission-ready proposal)

To enable comparability across studies and jurisdictions, we propose that PV sites report the following metrics whenever damaged/decommissioned modules are stored on-site:

Astore (m²): plan-view area occupied by stored modules on soil;

Nstore (pcs): number of modules stored;

Mstore (t): mass range or best estimate (with stated assumption);

tstore (months): storage duration since removal from operation;

Conditions: intact/cracked glass/broken glass/delaminated/unknown;

Storage interface: on soil/on pallets/on impermeable pad/under cover;

Runoff/erosion controls: none/berm/geotextile/drainage diversion.

These metrics are inexpensive (GIS + inspection) and directly support sustainability reporting and enforcement alignment with WEEE principles.

5. Conclusions

This brief report documents and quantifies a largely overlooked sustainability problem associated with the repowering of PV systems on agricultural land: on-site storage of damaged/decommissioned PV modules directly on soil. Two Czech case studies (0.861 and 1.109 MWp) show that approximately 1800 and 2000 modules, respectively, are stored within the PV parcels following repowering (2021–2022). Orthophoto-based GIS mapping quantified the stored PV module area (Astore) as 109 m² and 100 m², whereas the corresponding stored masses are substantial—~32–45 t and ~36–50 t—on the basis of a literature-consistent range of 18–25 kg/module.

Although storage footprints represent <1% of land area (Aland), they create persistent vegetation-suppressed patches and concentrate tens of tonnes of material directly on agricultural soil. Under a simple persistence scenario in which the current onsite stock remains until a second repowering event and a comparable number of modules are generated and stored again, cumulative onsite storage could approximately double (Astore ≈ 200–218 m² per site; Mstore ≈ 65–100 t per site). We interpret on-site storage on farmland as a practice–policy gap relative to EU WEEE circular-economic goals and recommend minimal, low-cost reporting indicators (Astore, Nstore, Mstore, storage duration, condition class, and storage interface) to make the issue visible and actionable in repowering projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K. (Martin Kozelka), V.P. (Vladislav Poulek), M.L. (Martin Libra). Methodology: M.K., T.F. (Tomáš Finsterle). GIS analysis: M.K. Investigation and field documentation: M.K., V.B. (Václav Beránek), J.M. Data curation: M.K. Formal analysis: M.K., V.P. Economic/agronomic context: A.K.-K. (Agnieszka Klimek-Kopyra), M.Kop. (Marcin Kopyra), F.K. (František Kumhála). Writing—original draft: M.K., V.P. Writing—review and editing: all authors. Supervision: V.P. All the authors have read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the internal research project, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, IGA 2024: 31160/1312/3107.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The derived GIS area measurements and calculation sheets can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to site anonymization constraints.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Weckend, S.; Wade, A.; Heath, G. End-of-Life Management: Solar Photovoltaic Panels; IRENA and IEA-PVPS: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2016. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2016/IRENA_IEAPVPS_End-of-Life_Solar_PV_Panels_2016.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Directive 2012/19/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) (Recast) Text with EEA Relevance; 2012. Vol. 197. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32012L0019 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Komoto, K.; Lee, J.-S.; Zhang, J.; Ravikumar, D.; Sinha, P.; Wade, A.; Heath, G. End-of-Life Management of Photovoltaic Panels: Trends in PV Module Recycling Technologies; 2018; p. NREL/TP--6A20-73847, 1561523. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/End_of_Life_Management_of_Photovoltaic_Panels_Trends_in_PV_Module_Recycling_Technologies_by_task_12.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Libra, M.; Kozelka, M.; Šafránková, J.; Belza, R.; Poulek, V.; Beránek, V.; Sedláček, J.; Zholobov, M.; Šubrt, T.; Severová, L. Agrivoltaics: Dual Usage of Agricultural Land for Sustainable Development. Int. Agrophys. 2024, 38, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics Provide Mutual Benefits across the Food–Energy–Water Nexus in Drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Mange, A.; Dejean, C.; Liron, F.; Belaud, G. Rain Concentration and Sheltering Effect of Solar Panels on Cultivated Plots. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrou, H.; Dufour, L.; Wery, J. How Does a Shelter of Solar Panels Influence Water Flows in a Soil–Crop System? Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 50, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, R.; Zaliwciw, D.; Cibin, R.; McPhillips, L. Minimizing Environmental Impacts of Solar Farms: A Review of Current Science on Landscape Hydrology and Guidance on Stormwater Management. Environ. Res.: Infrastruct. Sustain. 2022, 2, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview of Best Practices for Limiting Soil Sealing or Mitigating Its Effects in EU-27—Publications Office of the EU. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c20f56d4-acf0-4ca8-ae69-715df4745049/language-en (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Arnold, C.L.; Gibbons, C.J. Impervious Surface Coverage: The Emergence of a Key Environmental Indicator. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavidez, R.; Jackson, B.; Maxwell, D.; Norton, K. A Review of the (Revised) Universal Soil Loss Equation ((R)USLE): With a View to Increasing Its Global Applicability and Improving Soil Loss Estimates. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 6059–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köntges, M.; Kurtz, S.; Packard, C.; Jahn, U.; Berger, K.A.; Kato, K. Performance and Reliability of Photovoltaic Systems: Subtask 3.2: Review of Failures of Photovoltaic Modules: IEA PVPS Task 13: External Final Report; International Energy Agency, Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme: Sankt Ursen, 2014; Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/IEA-PVPS_T13-01_2014_Review_of_Failures_of_Photovoltaic_Modules_Final.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025)ISBN 978-3-906042-16-9.

- Poulek, V.; Aleš, Z.; Finsterle, T.; Libra, M.; Beránek, V.; Severová, L.; Belza, R.; Mrázek, J.; Kozelka, M.; Svoboda, R. Reliability Characteristics of First-Tier Photovoltaic Panels for Agrivoltaic Systems – Practical Consequences. Int. Agrophys. 2024, 38, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech Office for Surveying; Mapping and Cadastre (ČÚZK). Ortofoto České republiky (Orthophoto of the Czech Republic) [Dataset]. Geoportál ČÚZK. Available online: https://geoportal.cuzk.cz/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Stolz, P.; Frischknecht, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Current Photovoltaic Module Recycling. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Life_Cycle_Assesment_of_Current_Photovoltaic_Module_Recycling_by_Task_12.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Deng, R.; Chang, N.L.; Ouyang, Z.; Chong, C.M. A Techno-Economic Review of Silicon Photovoltaic Module Recycling. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 109, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiella, F.; D’Adamo, I.; Rosa, P. End-of-Life of Used Photovoltaic Modules: A Financial Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.; Malandrino, O.; Supino, S.; Testa, M.; Lucchetti, M.C. Management of End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels as a Step toward a Circular Economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2934–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunussa, C.E.L.; Ardente, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Mancini, L. Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Recycling Process for Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 156, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardente, F.; Latunussa, C.E.L.; Blengini, G.A. Resource Efficient Recovery of Critical and Precious Metals from Waste Silicon PV Panel Recycling. Waste Manag. 2019, 91, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.F.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahim, N.A.; Amin, N.; Nor Adzman, N. Global Challenges and Prospects of Photovoltaic Materials Disposal and Recycling: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerold, E.; Antrekowitsch, H. Advancements and Challenges in Photovoltaic Cell Recycling: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Królikowski, M.; Fotek, M.; Żach, P.; Michałowski, M. Development of a Recycling Process and Characterization of EVA, PVDF, and PET Polymers from End-of-Life PV Modules. Materials 2024, 17, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulek, V.; Beranek, V.; Kozelka, M.; Finsterle, T. Environmentally Sustainable Recycling of Photovoltaic Panels Laminated with Soft Polysiloxane Gels: Promoting the Circular Economy and Reducing the Carbon Footprint. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Shaw, S.; Libby, C.; Preciado, N.; Bicer, B.; Tamizhmani, G. A Review of Toxicity Assessment Procedures of Solar Photovoltaic Modules. Waste Manag. 2024, 174, 646–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Study on Photovoltaic Panels Supplementing the Impact Assessment for a Recast of the WEEE Directive. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/waste/weee/Study%20on%20PVs%20Bio%20final.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Robinson, S.A.; Meindl, G.A. Potential for Leaching of Heavy Metals and Metalloids from Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Systems. JNRD 2019, 9, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihervaara, P.; Auvinen, A.-P.; Mononen, L.; Törmä, M.; Ahlroth, P.; Anttila, S.; et al. How Essential Biodiversity Variables and Remote Sensing Can Help National Biodiversity Monitoring. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).