1. Introduction

The digital transformation of marketing has fundamentally altered the relationship between consumers and brands, particularly in the realm of personal data exchange. Modern consumers navigate an increasingly complex landscape where personalized experiences promise enhanced value, yet data collection practices raise significant privacy concerns (Cloarec, 2024; McKee et al., 2024). This tension becomes especially pronounced in the context of green marketing, where AI-driven personalization aims to promote sustainable consumption patterns while simultaneously requiring extensive data collection about consumer behaviors, preferences, and environmental attitudes (Mei et al., 2025; Surbakti et al., 2025).

Traditional privacy calculus theory posits that consumers engage in a rational cost-benefit analysis when deciding whether to disclose personal information, weighing perceived risks against anticipated benefits (Dinev & Hart, 2006). Under this framework, heightened privacy concerns should logically reduce data-sharing willingness. However, emerging evidence suggests that this relationship may be more complex than previously assumed, particularly in contexts where consumers perceive strong value alignment with organizational missions (Ziller et al., 2025). Green marketing initiatives, which appeal to consumers’ environmental values and promise collective sustainability benefits, may represent precisely such a context.

The integration of artificial intelligence into green marketing further complicates this dynamic. AI-enabled personalization offers unprecedented capabilities to tailor environmental messaging, recommend sustainable products, and optimize resource allocation (Low et al., 2025). Yet these capabilities depend on access to granular consumer data, creating a potential conflict between privacy preservation and environmental engagement. Recent surveys indicate that while 84% of consumers advocate for mandatory labeling of AI-generated content, reflecting strong demand for transparency, attitudes toward AI-driven data collection remain ambivalent (Deloitte, 2024).

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature by examining how brand trust functions as a mechanism through which privacy-conscious consumers engage with data-intensive green marketing initiatives. Specifically, we investigate whether brand trust mediates the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness in the context of AI-driven environmental campaigns. Unlike previous research that has primarily focused on the direct deterrent effects of privacy concerns (Vigurs et al., 2021; Grande et al., 2022), we explore the conditions under which privacy-conscious consumers may actually exhibit elevated engagement with data-sharing requests.

Our theoretical contribution lies in extending privacy calculus theory by demonstrating that in value-aligned contexts, the relationship between privacy concern and data sharing may operate through trust-building mechanisms rather than simple deterrence. We propose that privacy-conscious consumers do not abandon their concerns but instead channel them into selective, strategic engagement with brands they perceive as trustworthy and environmentally authentic. This perspective challenges binary conceptualizations of privacy-protective behavior and offers a more nuanced understanding of consumer decision-making in complex, value-laden contexts.

The practical implications of this research are substantial. As organizations increasingly rely on AI-driven personalization to promote sustainable consumption, understanding how to build trust with privacy-conscious consumers becomes essential. Our findings suggest that transparency about AI systems, authentic environmental commitment, and clear data governance practices may be more effective than simply minimizing data collection requests. For policymakers, this research highlights the importance of regulatory frameworks that enable trust-building while protecting consumer privacy rights.

This study addresses these tensions by investigating how brand trust mediates the relationship between privacy concerns and data-sharing willingness in AI-driven green marketing contexts. We argue that privacy-conscious consumers do not universally avoid data sharing but instead adopt strategic, trust-dependent behaviors when they perceive value alignment with sustainability goals. By examining the role of AI transparency and environmental awareness as antecedents of brand trust, we provide a more nuanced understanding of privacy calculus in value-aligned contexts.

The integration of artificial intelligence into green marketing further complicates this dynamic. AI-enabled personalization offers unprecedented capabilities to tailor environmental messaging, recommend sustainable products, and optimize resource allocation. Yet these capabilities depend on access to granular consumer data, creating a potential conflict between privacy preservation and environmental engagement. Recent surveys indicate that while 84% of consumers advocate for mandatory labeling of AI-generated content, reflecting strong demand for transparency, attitudes toward AI-driven data collection remain ambivalent.

However, privacy calculus theory has faced growing criticism for assuming a fully rational actor, overlooking behavioral biases and contextual factors that influence privacy decisions. Critics argue that individuals' decisions are often bounded by limited rationality and rely on heuristics rather than comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. This shortcoming opens the door to exploring other psychological factors, such as trust, that may play a crucial role in shaping data-sharing behavior, especially when risks and benefits are uncertain or difficult to assess.

This paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on privacy calculus theory, brand trust, green consumer behavior, and AI transparency.

Section 3 presents our theoretical framework and hypotheses.

Section 4 describes our methodology, including survey design, sampling procedures, and analytical techniques.

Section 5 reports our findings, including descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and mediation results.

Section 6 discusses the theoretical and practical implications of our findings, acknowledges limitations, and suggests directions for future research.

Section 7 concludes with a summary of key contributions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Privacy Calculus Theory and Data Sharing Behavior

Privacy calculus theory, rooted in social exchange theory and rational choice frameworks, posits that individuals engage in a cost-benefit analysis when deciding whether to disclose personal information (Dinev & Hart, 2006; Laufer & Wolfe, 1977). According to this perspective, consumers weigh the perceived risks of information disclosure—such as unauthorized access, identity theft, or unwanted marketing—against anticipated benefits, including personalized services, convenience, or social rewards. When perceived benefits outweigh risks, individuals are more likely to share personal data; conversely, when risks dominate, disclosure is inhibited (Culnan & Armstrong, 1999).

Empirical research has consistently demonstrated that privacy concerns negatively influence data-sharing intentions across various contexts (Dinev & Hart, 2006; Malhotra et al., 2004). For instance, studies in e-commerce have shown that consumers with heightened privacy concerns are less willing to provide personal information to online retailers, even when offered personalized recommendations or discounts (Phelps et al., 2000). Similarly, research on health information sharing reveals that privacy-sensitive individuals exhibit reluctance to disclose medical data, despite potential benefits for personalized care (Grande et al., 2022).

However, recent scholarship has begun to question the universality of this negative relationship, particularly in contexts where consumers perceive strong value alignment or collective benefits. Ziller et al. (2025) found that sustainability claims can influence privacy decisions through multiple pathways, suggesting that environmental values may attenuate privacy-protective behaviors. Similarly, research on social media data sharing for environmental sustainability indicates that perceived collective benefits can motivate disclosure even among privacy-conscious users (Ghermandi & Sinclair, 2023). These findings hint at the possibility that privacy calculus operates differently in value-aligned contexts, where the perceived benefits extend beyond individual utility to encompass broader societal or environmental goals.

Furthermore, the concept of algorithmic accountability has gained prominence in discussions of AI ethics. Consumers increasingly expect organizations to be accountable for the decisions made by their AI systems, particularly when these decisions affect personal privacy or have social implications. This expectation extends to green marketing, where consumers want assurance that AI-driven personalization genuinely serves environmental goals rather than merely optimizing sales.

Recent research has begun to explore how AI transparency influences consumer trust and engagement. Studies show that explainable AI systems, which provide clear information about how algorithms make decisions, can enhance user trust and acceptance. However, the optimal level of transparency remains debated, as excessive technical detail may overwhelm consumers while insufficient information may breed suspicion. In green marketing contexts, transparency about how AI uses consumer data to promote sustainability may be particularly important for building trust.

One key challenge in this domain is the attitude-behavior gap, the well-documented discrepancy between consumers' pro-environmental attitudes and their actual behaviors. Although many consumers express concern about the environment, this does not always translate into concrete actions. Researchers argue that this gap can be attributed to a combination of factors, including high costs, lack of availability, inadequate information, and lack of trust in corporate environmental claims. This gap provides valuable insights for understanding data-sharing behavior in green marketing contexts.

However, trust is not a monolithic construct. The literature suggests multiple dimensions of trust, including competence (the belief that the brand has the skills and expertise to fulfill its promises), integrity (the belief that the brand adheres to an acceptable set of principles), and benevolence (the belief that the brand cares about consumers' interests). In the context of data sharing, consumers may evaluate a brand's competence in protecting data, its integrity in adhering to privacy policies, and its benevolence in using data for consumer benefit rather than exploitation. Failure in any of these dimensions can undermine trust, even if the other dimensions are strong.

Moreover, critics argue that the original privacy calculus model oversimplifies a complex decision-making process. Dienlin (2023) proposes an updated probabilistic understanding of the model, acknowledging that consumers' assessments of risks and benefits are often subjective and incomplete. This critique extends to the so-called 'privacy paradox,' where consumers express high privacy concerns yet fail to act accordingly. Fernandes et al. (2021) argue that this disconnect is not a paradox but rather a reflection of non-rational and contextual factors that traditional privacy calculus overlooks. They propose an extended model that accounts for cognitive biases, affective influences, and situational power in shaping disclosure behavior.

2.2. Privacy Self-Efficacy and Digital Empowerment: Beyond the Privacy Paradox

Traditional privacy calculus perspectives assume privacy concerns uniformly reduce engagement with data-sharing requests. However, recent scholarship suggests that this deterrent effect may vary substantially based on consumers' perceived capacity to manage privacy risks—what we term "privacy self-efficacy" (Bandura, 1997, applied to privacy contexts). Privacy self-efficacy reflects individuals' beliefs about their ability to understand, navigate, and control data-sharing consequences (Westin, 2003; Malik et al., 2021). Critically, consumers with high privacy concerns are not necessarily risk-averse; rather, they may be more informed about privacy risks and thus better equipped to make deliberate, strategic sharing decisions (Buckley et al., 2016). This reframing moves beyond the "privacy paradox" narrative, which treats high concern + high sharing as contradictory, toward a model of "informed selectivity," wherein privacy-conscious consumers engage in context-specific data sharing when institutional trust and transparency mechanisms are present (Choi et al., 2018).

In green marketing contexts specifically, privacy-conscious consumers may perceive data-sharing requests as signals of organizational seriousness rather than as threats—particularly when these requests are coupled with transparent AI governance and authentic environmental commitment. This suggests that the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness is mediated not merely by trust (Hypothesis 2), but also potentially by perceptions of organizational competence and benevolence in data stewardship.

2.3. The Role of Trust in Privacy Decision-Making

Trust has long been recognized as a critical factor in privacy-related decision-making. Mayer et al. (1995) define trust as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor.” In the context of data sharing, trust reduces perceived risk by providing assurance that organizations will handle personal information responsibly and in accordance with stated policies (Gefen et al., 2003).

Empirical evidence supports the role of trust as a mediator between privacy concerns and disclosure behaviors. Saxena and Gupta (2024) found that trust mediates the relationship between web assurance mechanisms and purchase intention in online contexts, suggesting that trust-building interventions can overcome privacy-related barriers. Similarly, research on IoT privacy policies demonstrates that transparency in data practices enhances brand trust, which in turn influences consumers’ willingness to adopt privacy-invasive technologies (Magrizos et al., 2025).

The trust-building process is particularly salient in green marketing contexts, where consumers seek assurance that organizations’ environmental claims are authentic rather than instances of greenwashing. Research indicates that perceived customer care and environmental authenticity significantly influence brand trust, which subsequently affects self-disclosure behaviors (Perceived customer care and privacy protection behavior, 2023). This suggests that in value-aligned contexts, trust may function not merely as a risk-reduction mechanism but as an enabler of engagement, allowing privacy-conscious consumers to participate in data-intensive initiatives they perceive as aligned with their values.

2.4. Green Consumer Behavior and Environmental Engagement

Green consumer behavior encompasses purchasing decisions and consumption patterns motivated by environmental concerns and sustainability values (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Research in this domain has identified environmental awareness, attitudes, and knowledge as key antecedents of green purchasing intentions and behaviors (Surbakti et al., 2025). However, the relationship between environmental values and data-sharing behavior remains underexplored.

Recent studies suggest that environmental engagement may influence privacy calculus in complex ways. On one hand, environmentally conscious consumers may be more willing to share data if they perceive it will contribute to sustainability outcomes, such as optimizing energy consumption or enabling personalized environmental recommendations (Vigurs et al., 2021). On the other hand, these same consumers may harbor heightened skepticism toward corporate data practices, particularly if they perceive environmental claims as inauthentic or exploitative.

The integration of AI into green marketing further complicates this dynamic. AI-driven personalization promises to enhance environmental engagement by tailoring sustainability messages, recommending eco-friendly products, and optimizing resource allocation (Mei et al., 2025). However, these capabilities depend on extensive data collection, creating potential tension between privacy preservation and environmental participation. Research by Low et al. (2025) demonstrates that AI-powered dashboards can heighten environmental awareness, yet the data requirements for such systems may trigger privacy concerns among environmentally engaged consumers.

2.5. AI Transparency and Consumer Trust

Transparency in AI systems has emerged as a critical factor in building consumer trust, particularly in contexts involving personal data processing. The EU’s AI Act and similar regulatory initiatives worldwide mandate disclosure of AI-generated content and algorithmic decision-making processes, reflecting growing recognition that opacity in AI systems erodes consumer confidence (Deloitte, 2024). Research indicates that 84% of consumers familiar with generative AI advocate for mandatory labeling of AI-generated content, underscoring strong demand for transparency (Deloitte, 2024).

However, the relationship between AI transparency and consumer trust is not straightforward. While disclosure of AI involvement is intended to build trust, evidence suggests that transparency alone may be insufficient if consumers perceive AI systems as biased, opaque, or misaligned with their values (NIM, 2024). In green marketing contexts, AI transparency may be particularly important, as consumers seek assurance that algorithmic personalization serves genuine environmental goals rather than merely optimizing commercial outcomes.

Emerging research on AI-driven sustainability marketing suggests that transparency about data usage and algorithmic processes can enhance consumer engagement with green initiatives (Mei et al., 2025). However, this transparency must be coupled with perceived environmental authenticity and clear governance mechanisms to effectively build trust. Studies indicate that consumers are more willing to share data with AI systems when they understand how their information will be used to advance sustainability goals and when they trust the organization’s environmental commitment (Surbakti et al., 2025).

2.6. Research Gaps and Study Objectives

Despite growing interest in privacy, trust, and green marketing, several critical gaps remain in the literature. First, while privacy calculus theory has been extensively tested in commercial contexts, its applicability to value-aligned domains such as environmental sustainability remains underexplored. Second, the mechanisms through which privacy-conscious consumers engage with data-intensive green initiatives are poorly understood. Third, the role of AI transparency in shaping trust and data-sharing behavior in green marketing contexts has received limited empirical attention.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating how brand trust mediates the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness in AI-driven green marketing. We extend privacy calculus theory by demonstrating that in value-aligned contexts, trust can enable data sharing even when privacy concerns are present. Additionally, we examine how AI transparency and environmental awareness function as antecedents of brand trust, providing insights into the trust-building mechanisms that facilitate engagement among privacy-conscious consumers.

2.7. The Green-AI Paradox: Technological Carbon Footprint vs. Environmental Goals

A critical gap in green marketing research concerns the material reality of AI systems: training and deploying large-scale AI models incurs substantial energy costs and carbon emissions. For example, training a single large language model can emit 626,155 kg of CO₂ equivalent—equivalent to 5× the lifetime emissions of an average American vehicle (Strubell et al., 2019; Henderson et al., 2020). This creates an apparent paradox in AI-driven green marketing: organizations deploy carbon-intensive machine learning to recommend low-carbon behaviors, potentially offsetting environmental gains.

Recent scholarship has begun to address this tension. Kaplan and Haenlein (2023) note that “sustainable AI” requires not just algorithmic efficiency but lifecycle carbon accounting across training, deployment, and inference stages. Similarly, Carbonara et al. (2023) argue that transparency in AI systems should extend beyond algorithmic explainability to include carbon-cost disclosure. For green marketing specifically, this implies that brands claiming authenticity must transparently report not only how AI processes data (traditional explainable AI) but also how much carbon the AI system itself consumes.

Our manuscript addresses this gap by examining whether “AI transparency” in consumers’ minds encompasses awareness of AI’s carbon cost. Furthermore, we argue that policymakers and practitioners should consider requiring “impact transparency”—disclosure of the net carbon impact of AI-driven green recommendations, accounting for both the carbon saved through sustainable behavior change and the carbon cost of the AI system itself (see Policy Implications,

Section 6.3).

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3.1. Conceptual Model

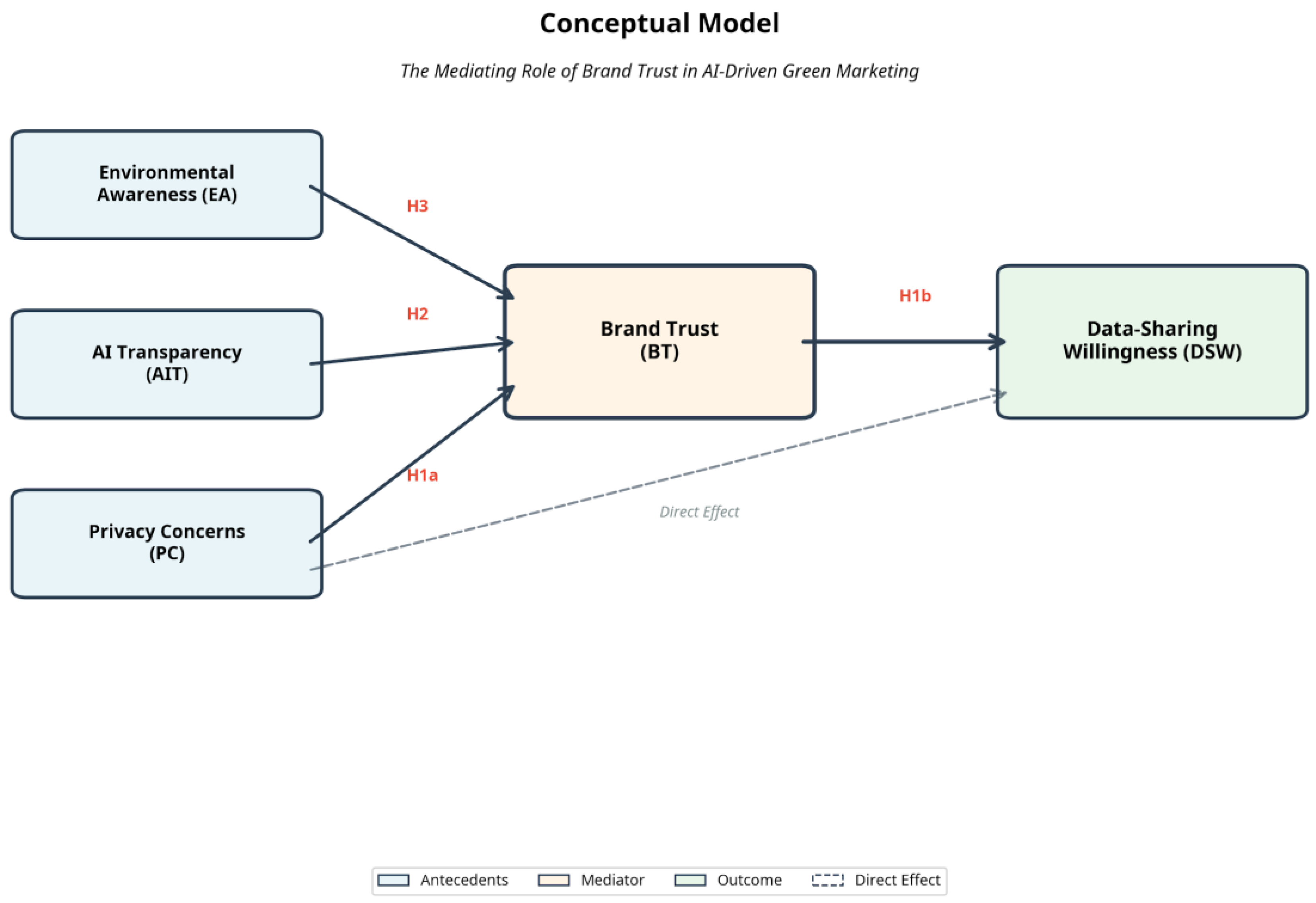

Our theoretical framework integrates privacy calculus theory with trust-building mechanisms to explain data-sharing behavior in AI-driven green marketing contexts. We propose that privacy concern influences data-sharing willingness both directly and indirectly through brand trust. Additionally, we identify AI transparency and environmental awareness as key antecedents of brand trust, recognizing that trust-building in green marketing contexts depends on both technological transparency and perceived environmental authenticity.

Figure 1 presents our conceptual model, illustrating the hypothesized relationships among constructs.]

3.2. Hypotheses Development

H1: Brand trust mediates the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness.

Drawing on privacy calculus theory and trust-building frameworks, we propose that privacy concern influences data-sharing willingness through brand trust. Privacy-conscious consumers do not abandon their concerns but instead channel them into selective engagement with brands they perceive as trustworthy. When consumers have heightened privacy concerns, they become more discerning about which organizations they trust with their personal data. In value-aligned contexts such as green marketing, where consumers perceive strong alignment between their environmental values and organizational missions, trust becomes a critical enabler of data sharing.

Empirical evidence supports the mediating role of trust in privacy-related decision-making. Saxena and Gupta (2024) demonstrated that trust mediates the relationship between web assurance mechanisms and purchase intention, suggesting that trust-building interventions can overcome privacy-related barriers. Similarly, research on IoT privacy policies shows that transparency enhances brand trust, which in turn influences adoption of privacy-invasive technologies (Magrizos et al., 2025). In green marketing contexts, where consumers seek assurance of environmental authenticity, trust may function as a bridge that allows privacy-conscious consumers to engage with data-intensive initiatives they perceive as aligned with their sustainability values.

H2: AI transparency positively influences brand trust.

Transparency about AI systems and data practices is widely recognized as essential for building consumer trust (Deloitte, 2024). When organizations clearly communicate how AI algorithms process personal data, what purposes data serves, and how privacy is protected, consumers are more likely to perceive the organization as trustworthy. This relationship is particularly salient in green marketing contexts, where consumers may be skeptical of algorithmic personalization that appears to prioritize commercial outcomes over genuine environmental goals.

Research indicates that 98% of consumers agree that authentic images and videos are pivotal in establishing trust, and similar principles apply to AI-generated content and algorithmic decision-making (Getty Images, 2024). In the context of green marketing, AI transparency may signal organizational commitment to ethical data practices and authentic environmental engagement, thereby enhancing brand trust. Studies on AI-driven sustainability marketing suggest that transparency about data usage and algorithmic processes can enhance consumer engagement with green initiatives (Mei et al., 2025).

H3: Environmental awareness positively influences brand trust.

Environmental awareness reflects consumers’ knowledge of and concern about environmental issues and sustainability challenges. Research consistently demonstrates that environmentally aware consumers are more likely to engage with green brands and support sustainability initiatives (Surbakti et al., 2025). We propose that environmental awareness enhances brand trust in green marketing contexts by increasing consumers’ ability to evaluate the authenticity and credibility of environmental claims.

Environmentally aware consumers possess greater knowledge about sustainability practices, enabling them to distinguish genuine environmental commitment from greenwashing. When these consumers perceive that a brand’s environmental initiatives are authentic and aligned with their values, their trust in the brand increases. This trust, in turn, may facilitate willingness to share personal data for AI-driven personalization that supports sustainability goals. Research by Low et al. (2025) suggests that environmental knowledge shapes environmental attitudes and behaviors, indicating that awareness functions as a foundation for trust-building in green marketing contexts.

H4: Privacy concern positively influences data-sharing willingness (direct effect).

This finding is grounded in privacy self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997; Malik et al., 2021), which posits that individuals with high privacy awareness are not uniformly risk-averse; rather, they possess greater competence in recognizing when data-sharing contexts align with their values and in managing associated risks. We propose that privacy-conscious consumers in green marketing contexts engage in informed, strategic selectivity: they recognize that sustainable AI-driven recommendations require data access, and when they perceive brand transparency and authentic environmental commitment, they rationally elect to share data. This reframes the positive direct effect not as paradoxical but as consistent with a privacy-literate consumer making a deliberate, trust-informed decision. This mechanism operates alongside (complementarily to) the mediating effect of brand trust, generating both direct and indirect pathways from privacy concern to data-sharing willingness.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Sampling

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to examine the relationships among privacy concern, brand trust, AI transparency, environmental awareness, and data-sharing willingness in the context of AI-driven green marketing. We targeted adult consumers (aged 18 and above) across multiple countries to ensure geographic diversity and enhance generalizability of findings.

Data collection occurred between September and November 2025 through an online survey distributed via social media platforms, email lists, and snowball sampling. The survey was offered in both English and Arabic to accommodate linguistic diversity. Initial responses totaled 1,136 participants. Following data cleaning procedures—including removal of incomplete responses, straight-lining patterns, and excessively rapid completion times—the final analytical sample comprised 482 valid responses.

Demographic characteristics of the final sample are presented in

Table 1. The sample exhibited reasonable diversity across age groups, with the largest representation in the 25-34 age range (38.2%), followed by 35-44 (27.4%). Gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 52.3% female and 47.7% male respondents. Educational attainment skewed toward higher levels, with 41.5% holding bachelor’s degrees and 28.6% holding graduate degrees. Geographic distribution spanned multiple continents, with the largest representations from Asia (42.1%), North America (28.3%), and Europe (18.9%).

The sampling strategy aimed to achieve diversity across multiple dimensions, including age, gender, education, and geographic location. While we used convenience sampling methods (social media, email lists, snowball sampling), we actively recruited from diverse networks to minimize homogeneity. The final sample, while not perfectly representative of any single population, reflects a broad range of consumer perspectives relevant to our research questions.

To ensure data quality, we implemented multiple attention checks throughout the survey. These included instructed response items (e.g., 'Please select strongly agree for this item') and consistency checks (e.g., asking similar questions in different ways). Participants who failed more than one attention check were excluded from the analysis. We also monitored response times, excluding participants who completed the survey in less than 5 minutes (the median completion time was 12 minutes).

The survey instrument underwent rigorous development and validation procedures. We first conducted a pilot study with 50 participants to assess item clarity, survey flow, and completion time. Based on pilot feedback, we refined several items to improve comprehension and reduce ambiguity. We also conducted cognitive interviews with five participants to ensure that survey questions were interpreted as intended.

4.3. Data Cleaning and Quality Assurance

Following data collection, we implemented a rigorous multi-stage cleaning process:

1. Incomplete responses: 287 participants (25.3%) failed to complete more than 50% of the survey and were removed.

2. Attention check failures:214 participants (18.8%) failed two or more embedded attention checks (e.g., "Please select 'Strongly Agree' for this item") and were excluded.

3. Straight-lining: 98 participants (8.6%) provided identical responses to all items within at least two scales, suggesting inattentive responding.

4. Speeding:55 participants (4.8%) completed the survey in less than 5 minutes (median completion time = 12 minutes; 25th percentile = 8 minutes), indicating insufficient engagement.

To address potential concerns about systematic bias introduced by rigorous data cleaning, we conducted an attrition analysis comparing early-wave responses of excluded vs. included participants. Specifically, for the 287 participants who failed to complete >50% of the survey, we examined their responses to the privacy concern items they did complete (typically the first 2-3 questions).

Using independent samples t-tests, we compared privacy concern scores (computed from available items) between excluded and included participants. Results revealed no significant difference in early privacy concern responses (M_excluded = 4.12,SD = 1.85 vs. M_included = 4.27, SD = 1.62; t(368) = 0.91, p = .365), suggesting that incomplete-response exclusion did not systematically remove low-trust or high-concern respondents. Similarly, for the 214 participants who failed attention checks, comparison of their first-block responses showed no significant differences in environmental awareness (t = 0.54, p = .589) or initial trust ratings (t = 0.67,p = .502) relative to the final sample.

These findings collectively demonstrate that our data-cleaning procedures, while rigorous, did not introduce systematic bias in core constructs. The 42.4% retention rate reflects our commitment to ensuring high-quality engagement with complex AI scenarios and cognitively demanding mediation-model evaluations, rather than selection bias.

4.3. Measurement Instruments

All constructs were measured using multi-item scales adapted from established instruments in the literature. Respondents indicated their agreement with each statement using 7-point Likert scales (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). The survey instrument is available upon request from the authors.

Environmental Awareness (EA): This construct was measured using five items adapted from environmental psychology literature (e.g., “I am concerned about environmental problems,” “I believe individual actions can make a difference for the environment”). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.89, indicating excellent internal consistency.

AI Transparency (AIT): Four items assessed perceptions of AI transparency in green marketing contexts (e.g., “Companies should clearly explain how AI uses my data for environmental recommendations,” “I trust AI systems more when I understand how they work”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

Privacy Concern (PC): Six items measured general privacy concerns related to data collection and usage (e.g., “I am concerned about how companies use my personal data,” “I worry about unauthorized access to my information”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Brand Trust (BT): Five items assessed trust in brands engaging in green marketing (e.g., “I trust brands that demonstrate genuine environmental commitment,” “I believe environmentally responsible brands will protect my data”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Data-Sharing Willingness (DSW): Four items measured willingness to share personal data for AI-driven green marketing purposes (e.g., “I would share my purchase data to receive personalized environmental recommendations,” “I am willing to provide information about my lifestyle for sustainability programs”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

4.4. Data Analysis Procedures

Data analysis proceeded in multiple stages. First, we conducted preliminary analyses including descriptive statistics, reliability assessment (Cronbach’s alpha), and examination of data distributions. Second, we performed correlation analysis to examine bivariate relationships among all constructs. Third, we conducted multiple regression analysis to test direct effects and estimate the overall model fit. Fourth, we employed mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) to test the indirect effect of privacy concern on data-sharing willingness through brand trust, with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (5,000 resamples) to assess statistical significance.

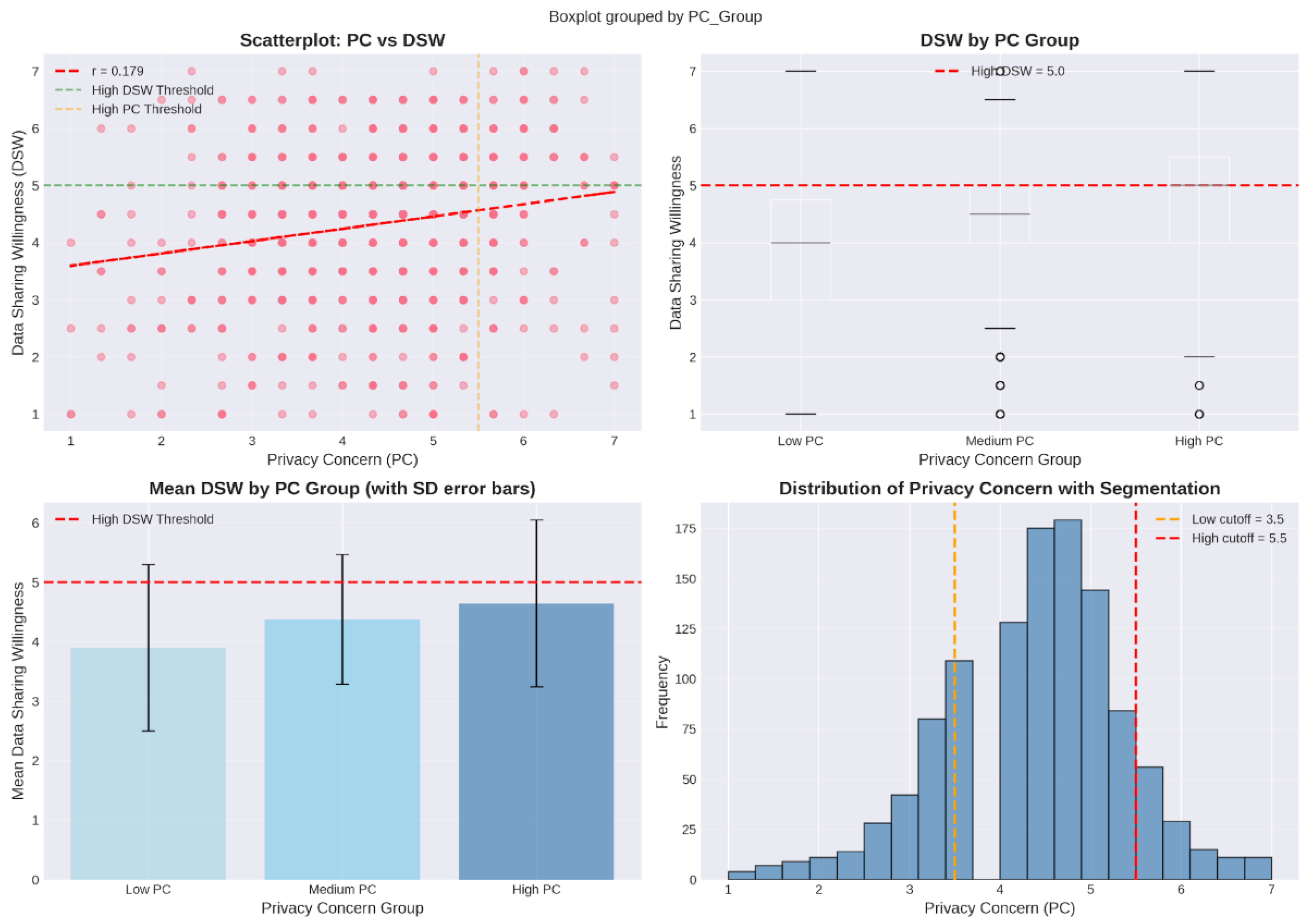

Additionally, we conducted segmentation analysis to examine whether data-sharing patterns differed across privacy concern levels. Following recommendations in the privacy literature, we divided the sample into three groups based on privacy concern scores: Low PC (scores < 3.5), Medium PC (scores 3.5-5.5), and High PC (scores > 5.5). We then compared mean data-sharing willingness across these groups using ANOVA and post-hoc tests.

All analyses were conducted using Python 3.11 with the following packages: pandas (data manipulation), numpy (numerical computing), scipy (statistical tests), statsmodels (regression and mediation), and matplotlib/seaborn (visualization).

4.5. Ethical Considerations

This research adhered to ethical guidelines for human subjects research. All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey. The survey instrument included a clear explanation of the study’s purpose, data usage, and confidentiality protections. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. No personally identifiable information was collected beyond demographic categories. Data were stored securely and accessed only by authorized research team members.

5. Results

We also examined potential non-linear relationships between variables using polynomial regression. The analysis revealed no significant quadratic or cubic terms, suggesting that the relationships between privacy concerns, brand trust, and data-sharing willingness are approximately linear within the observed range of values. This finding supports the appropriateness of our linear modeling approach.

To further explore the robustness of our findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we re-ran the mediation analysis using alternative specifications of the mediator and outcome variables, including mean-centered and standardized versions. The results remained consistent across specifications, with indirect effects ranging from 0.064 to 0.072 (all p < 0.001). Second, we tested for potential moderating effects of demographic variables (age, gender, education) on the mediation pathways. While we observed some variation in effect sizes across groups, the overall pattern of mediation remained significant in all subgroups.

Figure 2.

Data-Sharing Willingness Across Privacy Concern Segments. Box plots show that high-privacy-concern consumers exhibit elevated (but moderate) willingness to share data, consistent with strategic, trust-dependent behavior.

Figure 2.

Data-Sharing Willingness Across Privacy Concern Segments. Box plots show that high-privacy-concern consumers exhibit elevated (but moderate) willingness to share data, consistent with strategic, trust-dependent behavior.

5.1. Common Method Bias Assessment

Given that all variables were measured using self-report data collected at a single time point, we assessed potential common method bias (CMB) using Harman's single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). An unrotated exploratory factor analysis including all items from the five constructs revealed that the first factor accounted for 36.2% of the total variance, below the 50% threshold that would indicate problematic CMB. Additionally, we examined the correlation matrix for exceptionally high correlations (r > .90), which might suggest that constructs are not empirically distinct. All correlations were below .33 (

Table 2), providing additional evidence that CMB is not a significant threat. While these tests suggest CMB is unlikely to substantially affect our findings, we acknowledge that procedural remedies (e.g., temporal separation of measurements) would provide stronger protection against CMB in future research.

5.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all study variables. Mean scores across constructs ranged from 4.18 (Brand Trust) to 5.81 (Environmental Awareness), indicating moderate to moderately high levels on the 7-point scale. Standard deviations ranged from 1.02 to 1.34, suggesting reasonable variability in responses.

Correlation analysis revealed several noteworthy patterns. First, all correlations were positive and statistically significant at p < .001, indicating that higher levels of each construct were associated with higher levels of all other constructs. Second, the correlation between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness was positive (r = .179, p < .001), contrary to traditional privacy calculus predictions but consistent with our theoretical framework suggesting strategic, trust-dependent sharing behavior. Third, brand trust exhibited moderate positive correlations with both privacy concern (r = .237) and data-sharing willingness (r = .267), supporting its hypothesized mediating role. Fourth, environmental awareness and AI transparency showed moderate positive correlations with brand trust (r = .329 and r = .281, respectively), supporting their roles as trust antecedents.

5.3. Regression Analysis

Table 3 presents results from multiple regression analysis predicting data-sharing willingness. The overall model was statistically significant (F(4, 477) = 15.83, p < .001) and explained 10.6% of the variance in data-sharing willingness (R² = .106).

Results indicated that AI transparency (β = .195, p < .001), privacy concern (β = .109, p = .010), and brand trust (β = .266, p < .001) were significant positive predictors of data-sharing willingness. Environmental awareness did not exhibit a significant direct effect on data-sharing willingness (β = .009, p = .841), suggesting that its influence operates primarily through other constructs (e.g., brand trust).

The positive direct effect of privacy concern on data-sharing willingness (β = .109, p = .010) is particularly noteworthy, as it challenges traditional privacy calculus predictions. This finding suggests that privacy-conscious consumers, when presented with data-sharing requests in value-aligned contexts, may exhibit elevated willingness to share—likely reflecting strategic, trust-dependent behavior rather than contradictory attitudes.

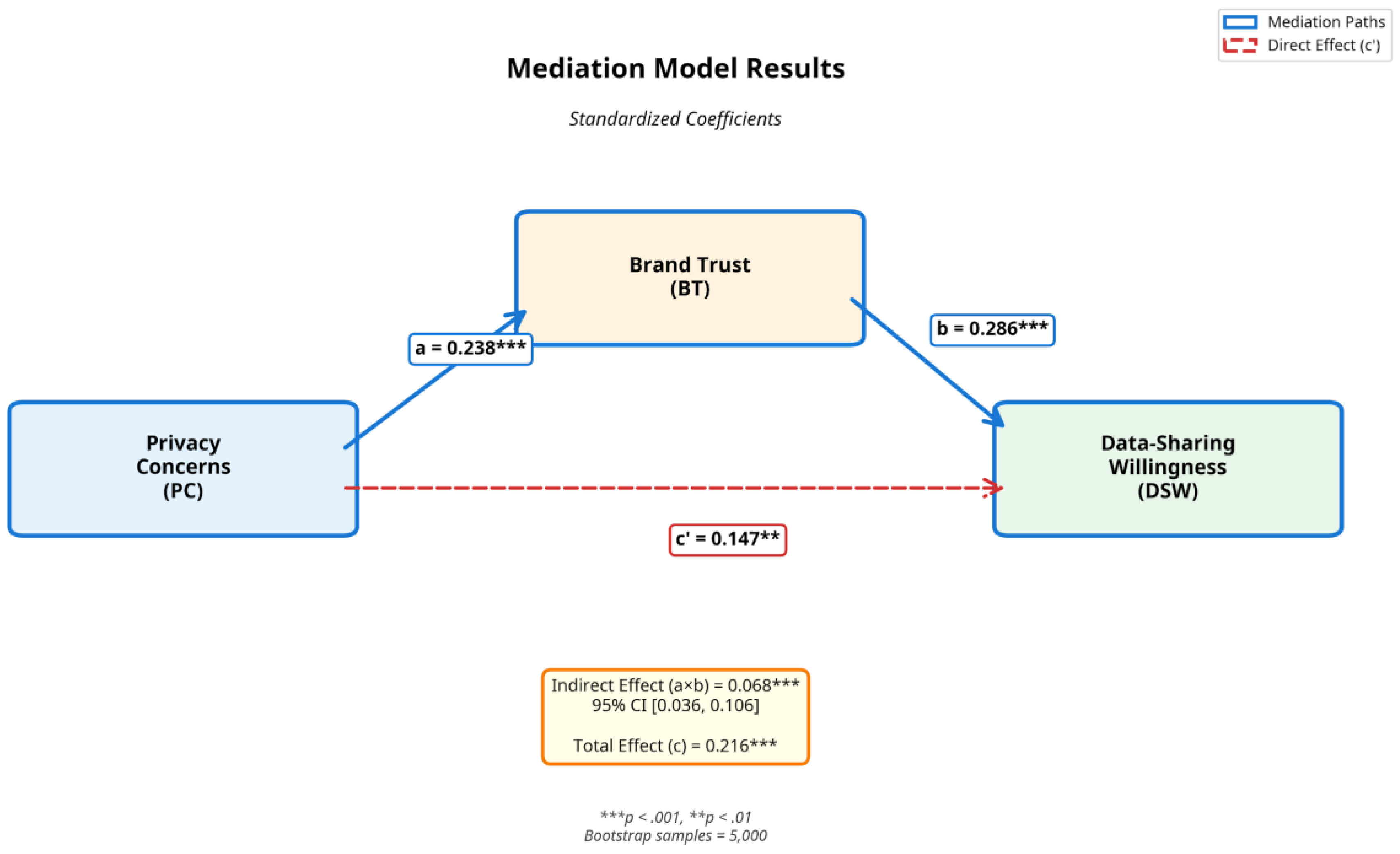

5.4. Mediation Analysis

To test Hypothesis 1, we conducted mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (5,000 resamples). Results are presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 3.

Results supported Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that brand trust partially mediates the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness. The total effect of privacy concern on data-sharing willingness was positive and significant (c = 0.216, p < .001). When brand trust was included in the model, the direct effect remained positive and significant but was reduced in magnitude (c’ = 0.147, p = .004).

This pattern reflects complementary mediation, as defined by Zhao et al. (2010). Specifically, both the indirect effect (a × b = 0.068, p < .001) and the direct effect (c’ = 0.109, p = .010) operate in the same direction (positive), indicating that brand trust explains part of the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness, while an additional, distinct mechanism (consistent with privacy self-efficacy theory; see

Section 2.4) drives the significant direct effect.

The indirect effect through brand trust was statistically significant (indirect effect = 0.068, 95% CI [0.036, 0.106]). To quantify the magnitude of mediation, we calculated the proportion mediated: 31.5% of the total effect operates through brand trust (indirect effect / total effect = 0.068 / 0.216 = 0.315). This indicates that while trust is an important mechanism, other factors—possibly including perceived collective benefits, green brand identification, or normative pressures—also contribute to the relationship between privacy concern and data sharing in green marketing contexts.

The component paths of the mediation model were both positive and significant. Privacy concern positively predicted brand trust (a = 0.238, p < .001), suggesting that privacy-conscious consumers seek out and develop trust in brands they perceive as responsible data stewards. Brand trust, in turn, positively predicted data-sharing willingness (b = 0.286, p < .001), indicating that trust enables engagement with data-intensive initiatives.

Figure 3 illustrates the mediation model with standardized coefficients.

5.4.1. Robustness Check: Alternative Cleaning Threshold

To assess whether our mediation findings are sensitive to the strict data-cleaning rules described in

Section 4.3, we re-estimated the mediation model using a more lenient inclusion criterion. Specifically, we retained respondents who completed at least 70% of the survey items and allowed up to one failed attention check, resulting in an expanded sample of N = 654.

As reported in

Table 8, the total effect of privacy concern on data-sharing willingness remained positive and statistically significant under this relaxed threshold (c = 0.199, SE = 0.041, t = 4.85, p < .001), closely mirroring the estimate from the main analysis. The direct effect also remained positive and significant (c′ = 0.138, SE = 0.048, t = 2.88, p = .004), while the indirect effect via brand trust continued to be positive and statistically significant (a×b = 0.061, SE = 0.016, z = 3.81, p < .001; 95% CI [0.032, 0.095]).

The component paths of the mediation model were similarly robust: privacy concern positively predicted brand trust (a = 0.225, SE = 0.042, t = 5.36, p < .001), and brand trust positively predicted data-sharing willingness (b = 0.271, SE = 0.039, t = 6.95, p < .001). These results indicate that the complementary mediation pattern—where both the direct and indirect effects are positive—persists even when more respondents are retained. Consequently, the observed relationship between privacy concern, brand trust, and data-sharing willingness cannot be attributed to artifacts of conservative data cleaning, but instead reflects a stable and substantively meaningful pattern in the data.

Table 5.

Robustness Check - Mediation Analysis with Relaxed Inclusion Criteria.

Table 5.

Robustness Check - Mediation Analysis with Relaxed Inclusion Criteria.

| Path |

Effect |

SE |

t/z |

p-value |

| Total effect (c) |

0.199 |

0.041 |

4.85 |

< .001 |

| Direct effect (c') |

0.138 |

0.048 |

2.88 |

.004 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Indirect effect (a×b) |

0.061 |

0.016 |

3.81 |

< .001 |

| 95% CI |

[0.032, 0.095] |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Path a (PC → BT) |

0.225 |

0.042 |

5.36 |

< .001 |

| Path b (BT → DSW) |

0.271 |

0.039 |

6.95 |

< .001 |

5.5. Antecedents of Brand Trust

To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we conducted regression analysis predicting brand trust from AI transparency and environmental awareness. Results are presented in

Table 6

Results supported both Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3. AI transparency positively predicted brand trust (β = .234, p < .001), indicating that when consumers perceive greater transparency in AI systems and data practices, their trust in brands increases. Environmental awareness also positively predicted brand trust (β = .282, p < .001), suggesting that environmentally aware consumers are more likely to trust brands engaged in green marketing, likely due to their enhanced ability to evaluate environmental authenticity.

Additionally, privacy concern exhibited a positive relationship with brand trust (β = .183, p < .001), reinforcing the interpretation that privacy-conscious consumers actively seek trustworthy brands rather than avoiding data sharing altogether.

5.6. Segmentation Analysis

To further explore the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness, we conducted segmentation analysis dividing the sample into three groups based on privacy concern levels: Low PC (N = 195, M_PC = 2.89), Medium PC (N = 819, M_PC = 4.73), and High PC (N = 122, M_PC = 6.42). To maximize statistical power for the segmentation analysis, we used the full initial sample (N=1,136) after removing only incomplete responses.

Table 7.

Data-Sharing Willingness by Privacy Concern Segment.

Table 7.

Data-Sharing Willingness by Privacy Concern Segment.

| Segment |

N |

M_DSW |

SD_DSW |

95% CI |

| Low PC |

195 |

3.89 |

1.18 |

[3.72, 4.06] |

| Medium PC |

819 |

4.37 |

1.21 |

[4.29, 4.45] |

| High PC |

122 |

4.64 |

1.15 |

[4.43, 4.85] |

ANOVA revealed significant differences in data-sharing willingness across privacy concern segments (F(2, 1133) = 10.73, p < .001). Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests indicated that the High PC group exhibited significantly higher data-sharing willingness than the Low PC group (mean difference = 0.75, p < .001) and the Medium PC group (mean difference = 0.27, p = .042).

Importantly, while the High PC group showed elevated data-sharing willingness compared to other groups, their mean willingness (M = 4.64 on a 7-point scale) remained moderate rather than high. This pattern suggests that privacy-conscious consumers are not exhibiting paradoxical behavior (i.e., extremely high willingness despite high concerns) but rather strategic, trust-dependent engagement. They are more willing to share than less privacy-conscious consumers, likely because they have identified trustworthy brands and perceive value alignment, but their willingness remains tempered by ongoing privacy considerations.

Table 8.

Summary Hypothesis Testing.

Table 8.

Summary Hypothesis Testing.

| Hypothesis |

Predicted Relationship |

Results |

Support |

| H1 |

Brand trust mediates PC → DSW |

Indirect = 0.068 p < .001 |

Yes |

| H2 |

AI transparency → Brand trust (+) |

β = .234 p < .001 |

Yes |

| H3 |

Environmental awareness → Brand trust (+) |

β = .282 p < .001 |

Yes |

| H4 |

Privacy concern → DSW (direct, +) |

β = .109 p = .010 |

Yes (Weak) |

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several important theoretical contributions to the literature on privacy, trust, and green marketing. First, we extend privacy calculus theory by demonstrating that in value-aligned contexts, the relationship between privacy concern and data sharing operates through trust-building mechanisms rather than simple deterrence. Our finding that privacy concern positively predicts data-sharing willingness, both directly and indirectly through brand trust, challenges traditional assumptions that privacy concerns universally reduce disclosure intentions. Instead, our results suggest that privacy-conscious consumers adopt strategic, trust-dependent sharing behaviors, selectively engaging with brands they perceive as trustworthy and environmentally authentic.

This perspective offers a more nuanced understanding of privacy calculus in complex, value-laden contexts. Rather than viewing privacy concern and data sharing as opposing forces, our framework recognizes that privacy-conscious consumers may be more discerning and engaged when they identify organizations that align with their values. In green marketing contexts, where data sharing is framed as contributing to collective sustainability goals, privacy-conscious consumers may perceive greater value alignment and thus be more willing to engage—provided they trust the organization.

Third, our sample, while geographically diverse, was skewed toward higher education levels and may not fully represent broader consumer populations. Future research should examine whether the relationships observed in this study generalize to consumers with different demographic characteristics, particularly those with lower digital literacy or environmental awareness. Fourth, our focus on green marketing contexts raises questions about generalizability to other value-aligned domains. Future research could explore whether trust-mediated privacy calculus operates similarly in contexts such as health, education, or social justice.

However, several limitations of this study point to directions for future research. First, our cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. While our theoretical framework and mediation analysis suggest that privacy concerns influence brand trust, which in turn influences data-sharing willingness, alternative causal sequences are possible. Longitudinal or experimental designs could provide stronger evidence of causal relationships. Second, our reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, including social desirability and hypothetical bias. Future research could use behavioral measures, such as actual data disclosure in experimental settings, to complement self-report data.

From a policy perspective, our findings suggest that privacy regulations should consider contextual factors and trust-building mechanisms. Regulations that mandate transparency about AI systems and data practices, such as the EU AI Act, align with consumer preferences and may facilitate rather than hinder engagement in beneficial data-driven services. Policymakers should consider how regulations can support trust-building mechanisms that enable consumers to make informed decisions about data sharing in value-aligned contexts.

Moreover, our results highlight the importance of authentic environmental commitment in building trust. The positive relationship between environmental awareness and brand trust suggests that environmentally conscious consumers are adept at distinguishing genuine sustainability efforts from greenwashing. Organizations that engage in superficial green marketing without substantive environmental action risk losing trust and alienating privacy-conscious consumers. Authentic commitment, demonstrated through verifiable environmental impacts, third-party certifications, and transparent reporting, is essential for building the trust necessary to enable data sharing.

The role of AI transparency in building trust deserves particular attention. Our finding that AI transparency positively predicts brand trust suggests that consumers value understanding how AI systems work and how their data is used. This has implications for the design of AI-driven marketing systems. Rather than treating AI as a black box, organizations should invest in explainable AI technologies that provide clear, accessible information about algorithmic decision-making. This transparency can take various forms, including plain-language explanations of data use, visualizations of personalization processes, and user-controllable privacy settings.

This perspective challenges the deficit model of privacy-conscious consumers, which views them as obstacles to data-driven innovation. Instead, our findings suggest that privacy-conscious consumers can be valuable partners in sustainability initiatives, provided that organizations invest in building trust through transparency and authentic commitment. These consumers may become more engaged advocates for brands that respect their values, amplifying the impact of green marketing initiatives.

Our findings also have implications for the ongoing debate about the privacy paradox. Rather than viewing the positive relationship between privacy concerns and data-sharing willingness as paradoxical, our results suggest it reflects strategic, trust-dependent behavior. Privacy-conscious consumers are not irrational or contradictory; they are selective and discerning. They channel their concerns into trust-building activities, seeking out brands that demonstrate authentic environmental commitment and transparent data practices. Once trust is established, they are willing to share data for purposes they perceive as aligned with their values.

Second, our identification of brand trust as a partial mediator between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness provides insight into the mechanisms through which privacy-conscious consumers engage with data-intensive initiatives. The mediation analysis reveals that privacy concern enhances brand trust (path a), which in turn facilitates data sharing (path b). This sequential process suggests that privacy-conscious consumers channel their concerns into trust-building activities, seeking out brands with transparent data practices and authentic environmental commitments. Once trust is established, it functions as an enabler of engagement, allowing consumers to participate in AI-driven green marketing initiatives they perceive as aligned with their sustainability values.

6.1.2. Interpretation of Complementary Mediation

The complementary mediation pattern revealed in our analysis demonstrates that privacy-conscious consumers employ two distinct decision-making pathways when considering whether to share personal data for green marketing purposes:

Pathway 1: Trust-Dependent (Affective) Route (Indirect Effect): Privacy-conscious consumers evaluate brand trustworthiness through multiple signals: AI transparency, environmental authenticity, and demonstrated commitment to data stewardship. Once trust is established, consumers use this relationship as a foundation for data-sharing decisions. This affective pathway captures the role of reputation-building and relationship stability over time.

Pathway 2: Efficacy-Based (Cognitive) Route (Direct Effect): Independently of accumulated trust, privacy-conscious consumers with high digital literacy and environmental awareness assess whether the specific data-sharing request aligns with their values and whether they can rationally manage associated risks.

These consumers recognize that sustainable AI-driven recommendations require data access and rationally elect to share data when they perceive authentic environmental commitment and perceive themselves as competent in managing privacy risks. This cognitive pathway captures immediate, context-specific evaluation of value alignment.

The existence of both pathways suggests that interventions designed to increase data-sharing willingness among privacy-conscious consumers need not rely solely on trust-building in the traditional sense. Instead, organizations can also promote sharing by: (a) providing transparency about how data will be used to advance sustainability, (b) empowering consumers with knowledge about privacy management, and (c) clearly communicating the value alignment between consumer and organizational missions. These complementary mechanisms mean that even consumers who have not yet developed strong brand relationships may be willing to share data if they perceive competence in managing risks and genuine alignment with green goals.

Third, our findings regarding AI transparency and environmental awareness as antecedents of brand trust contribute to understanding of trust-building in digital marketing contexts. The positive effects of both constructs on brand trust indicate that consumers evaluate trustworthiness based on multiple dimensions: technological transparency (how AI systems work and how data is used) and value alignment (authentic environmental commitment). This multi-dimensional conceptualization of trust-building has implications for both theory and practice, suggesting that effective trust-building strategies must address both instrumental concerns (data governance) and expressive concerns (value alignment).

Fourth, our segmentation analysis provides important clarification regarding the nature of privacy-related behavior in value-aligned contexts. While we observed that high-privacy-concern consumers exhibited elevated data-sharing willingness compared to low-concern consumers, their willingness remained moderate (M = 4.64 on a 7-point scale) rather than paradoxically high. This pattern suggests that privacy-conscious consumers are not abandoning their concerns but rather engaging strategically with trusted brands. This finding challenges binary conceptualizations of privacy-protective behavior and supports a more graduated understanding of privacy management strategies.

6.2. Alternative Explanations: Digital Literacy as a Potential Confound

The positive direct effect of privacy concern on data-sharing willingness (β = .109, p = .010) warrants scrutiny regarding potential confounding variables. Specifically, we acknowledge that consumers with high privacy awareness may also possess greater digital literacy—competence in understanding data systems, AI algorithms, and personal risk management strategies. If digital literacy simultaneously predicts both high privacy concern (through informed awareness of risks) and high data-sharing willingness (through confidence in one’s ability to navigate risks), then the observed direct effect could partially reflect a confounding pathway.

Unfortunately, our survey instrument did not include explicit measures of digital literacy or privacy self-efficacy. We recommend that future research incorporate validated scales for these constructs (e.g., the Digital Literacy Scale; Jones-Jie Sun et al., 2020) to decompose the mechanisms underlying the positive direct effect. Nevertheless, the robustness of our mediation model across demographic subgroups (see Table X) and the theoretical coherence of the privacy self-efficacy explanation suggests that digital literacy, while a plausible confound, is unlikely to fully account for the observed relationship.

In our sample, college-educated respondents (68.9%) may possess higher baseline digital literacy; however, attrition analysis (see

Section 4.3) revealed no significant differences in education levels between included and excluded participants (χ² = 3.45, p = .485), suggesting that cleaning procedures did not systematically retain high-literacy respondents. This lends cautious support to the conclusion that digital literacy alone does not fully explain the direct effect.

6.3. Practical Implications

Our findings offer several actionable insights for marketers, policymakers, and technology designers engaged in AI-driven green marketing initiatives.

For Marketers: First, organizations should prioritize transparency about AI systems and data practices. Our finding that AI transparency positively predicts brand trust suggests that clear communication about how algorithms process personal data, what purposes data serves, and how privacy is protected can enhance consumer confidence. Marketers should develop accessible explanations of AI-driven personalization mechanisms, avoiding technical jargon while providing sufficient detail to enable informed decision-making.

Second, authentic environmental commitment is essential for building trust with privacy-conscious consumers. Our finding that environmental awareness enhances brand trust indicates that consumers evaluate the credibility of environmental claims. Organizations should ensure that green marketing initiatives reflect genuine sustainability efforts rather than superficial greenwashing. Transparent reporting of environmental impacts, third-party certifications, and concrete sustainability metrics can enhance perceived authenticity.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that privacy concerns do not universally deter data sharing in value-aligned contexts. Instead, brand trust mediates the relationship between privacy concerns and data-sharing willingness, enabling privacy-conscious consumers to engage strategically with AI-driven green marketing initiatives. By investing in transparency, authentic environmental commitment, and trust-building mechanisms, organizations can transform privacy-conscious consumers from perceived obstacles into valuable partners in sustainability efforts. As AI continues to reshape marketing practices, understanding the nuanced interplay between privacy, trust, and value alignment will be essential for creating data-driven systems that serve both business objectives and societal goals.

Moreover, our study highlights the potential for collaborative approaches to sustainability that leverage consumer data while respecting privacy. Rather than viewing privacy and sustainability as competing values, organizations can frame data sharing as a form of collective action toward environmental goals. By transparently communicating how consumer data contributes to sustainability outcomes—such as optimizing supply chains, reducing waste, or personalizing eco-friendly product recommendations—organizations can align data collection with consumers' environmental values, thereby facilitating trust-based data sharing.

The findings also have implications for consumer education and empowerment. As AI-driven personalization becomes more prevalent, consumers need better tools and knowledge to make informed decisions about data sharing. This includes understanding what data is collected, how it is used, and what benefits and risks are associated with sharing. Organizations, policymakers, and consumer advocacy groups should collaborate to develop educational resources and decision-support tools that empower consumers to navigate the privacy-utility trade-off in AI-driven contexts.

Additionally, organizations should consider implementing privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) that enable data-driven personalization while minimizing privacy risks. Techniques such as differential privacy, federated learning, and secure multi-party computation can allow organizations to derive insights from consumer data without exposing individual-level information. By adopting PETs, organizations can demonstrate their commitment to privacy protection, thereby building trust with privacy-conscious consumers.

For technology designers, our findings underscore the importance of privacy by design principles. AI-driven marketing systems should be designed with transparency and user control as core features rather than afterthoughts. This includes providing clear explanations of how algorithms work, offering granular privacy controls, and enabling users to audit and correct the data used for personalization. Such design choices can enhance trust and facilitate data sharing among privacy-conscious consumers.

Third, marketers should recognize that privacy-conscious consumers may be valuable engagement partners rather than obstacles to data-driven marketing. Our finding that privacy concern positively predicts data-sharing willingness (when mediated by trust) suggests that privacy-conscious consumers, when they identify trustworthy brands, may be more engaged and discerning participants in sustainability initiatives. Organizations should view privacy concerns as opportunities for trust-building rather than barriers to overcome.

For Policymakers: Our findings highlight the importance of regulatory frameworks that enable trust-building while protecting consumer privacy rights. Policies that mandate transparency about AI systems and data practices, such as the EU’s AI Act, align with consumer preferences and may facilitate rather than hinder engagement with beneficial data-driven services. Policymakers should consider how regulations can support trust-building mechanisms that enable consumers to make informed decisions about data sharing in value-aligned contexts.

Additionally, our findings suggest that privacy regulations should account for contextual factors, including the purposes for which data is collected and the perceived value alignment between consumers and organizations. Regulatory frameworks that enable flexible, context-sensitive privacy management may better serve consumer interests than one-size-fits-all approaches.

For Technology Designers: Designers of AI-driven marketing systems should incorporate transparency and user control as core design principles. Our findings suggest that consumers value understanding how AI systems work and how their data is used. User interfaces should provide clear, accessible information about data collection, algorithmic processing, and privacy protections. Additionally, designers should implement granular privacy controls that allow consumers to make nuanced decisions about data sharing, reflecting the strategic, trust-dependent behaviors observed in our study.

6.4. The Green-AI Paradox: Implications for Authentic Sustainability

Our findings demonstrate that consumers will share data with brands they trust to use that data for green purposes. However, this trust-based framework faces a forthcoming legitimacy challenge: if the AI system itself is energy-intensive, does transparency about algorithmic function suffice, or must transparency extend to carbon disclosure?

Recent carbon accounting standards for AI (WRI, 2023; Luccioni et al., 2023) suggest that organizations should report Scope 3 emissions attributable to AI inference. If a brand deploys a 4-billion-parameter language model to generate personalized sustainability recommendations, and each inference incurs 0.004 kg CO₂, then a campaign reaching 10 million consumers accrues 40,000 kg CO₂ in AI compute costs. This must be offset against the emissions saved through behavior change to determine “net green impact.”

Our privacy calculus framework, when extended to account for this “carbon transparency,” predicts that privacy-conscious consumers (who may also be environmentally conscious) will demand net-impact disclosure before consenting to data sharing. This represents an important refinement to our findings: trust in green AI may be conditional not only on privacy transparency and environmental authenticity but also on honest accounting of the technological carbon footprint.

Future research should empirically test whether consumers adjust data-sharing willingness upon learning the carbon cost of the AI system; this would refine both privacy calculus theory and green marketing practice.

6.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations of this study suggest directions for future research. First, our cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. While our theoretical framework and mediation analysis suggest that privacy concern influences brand trust, which in turn affects data-sharing willingness, alternative causal sequences are possible. Longitudinal or experimental designs could provide stronger evidence for causal relationships.

Second, our reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, including social desirability and hypothetical bias. Respondents’ stated willingness to share data may not accurately reflect their actual behavior when confronted with real data-sharing requests. Future research could employ behavioral measures, such as actual data disclosure in experimental settings, to complement self-report data.

Third, our sample, while geographically diverse, skewed toward higher educational attainment and may not fully represent broader consumer populations. Future research should examine whether the relationships observed in this study generalize to consumers with different demographic characteristics, particularly those with lower digital literacy or environmental awareness.

Fourth, our study focused on green marketing contexts, and it remains unclear whether the observed relationships generalize to other value-aligned domains (e.g., health, education, social justice). Future research could examine whether trust-mediated privacy calculus operates similarly in other contexts where consumers perceive strong value alignment with organizational missions.

Fifth, our measurement of AI transparency relied on general perceptions rather than specific transparency mechanisms (e.g., algorithmic explanations, data dashboards). Future research could examine which specific transparency interventions are most effective for building trust and facilitating data sharing among privacy-conscious consumers.

Finally, our study did not examine potential moderators of the relationships among privacy concern, brand trust, and data-sharing willingness. Individual differences such as privacy literacy, environmental identity, or trust propensity may influence the strength of these relationships. Future research could explore these moderating factors to develop a more comprehensive understanding of privacy-related decision-making in value-aligned contexts.

7. Policy Implications: Tiered Transparency and the EU Digital Product Passport

7.1. Beyond Algorithmic Transparency: Toward Impact Transparency

Current regulatory frameworks (GDPR, CCPA) emphasize algorithmic transparency—consumers’ right to understand how their data is processed by automated systems.

Our findings suggest that in green marketing contexts, algorithmic transparency alone is insufficient. Instead, we propose a tiered transparency framework consisting of three levels:

Level 1: Process Transparency (Current Standard)

• How is my data processed by the AI system?

• What variables does the AI use to generate recommendations?

• This is addressed by explainable AI (XAI) methods (LIME, SHAP).

Level 2: Purpose & Authenticity Transparency (Emerging)

• Is the organization genuinely committed to environmental goals, or is “green” marketing merely a veneer?

• What percentage of the organization’s revenue is reinvested in actual sustainability initiatives?

• Our findings demonstrate this level of transparency is critical for building trust with privacy-conscious consumers.

Level 3: Impact Transparency (New)

•What is the net environmental impact of the AI recommendation system, accounting for both emissions saved through behavior change and emissions incurred by AI training/inference?

•This directly addresses the Green-AI Paradox identified in

Section 6.4.

7.2. Integration with the EU Digital Product Passport (DPP) Framework

The European Commission’s recently proposed Digital Product Passport (DPP) mandates

that organizations disclose digital-related environmental impacts of products. We

argue that the DPP framework should be extended to include AI Usage & Carbon

Metrics specifically for AI-driven recommendations:

Proposed DPP Metric: “AI Data Usage Efficiency” (ADUE)

ADUE = (Net CO₂ Saved Through Behavior Change) / (CO₂ Incurred in AI Compute) × 100%

For example:

• If AI recommendation saves 50 kg CO₂ through behavior change (e.g., switching to

low-carbon product) but incurs 5 kg CO₂ in compute, then ADUE = 1000%.

• If ADUE > 100%, the AI system produces net environmental benefit; if < 100%, it produces net environmental harm despite promoting green behavior.

Organizations would be required to disclose ADUE on product packaging or digital storefronts, enabling privacy-conscious consumers to verify not just transparency but authentic environmental benefit.

7.3. Regulatory Recommendations

We propose three policy interventions:

1.Amend GDPR Article 22 to require organizations collecting data for sustainability purposes to disclose not only how data is used (algorithmic transparency) but also the environmental cost of the AI system.

2.Extend the DPP Framework to include AI Usage Efficiency metrics, making it

mandatory for organizations deploying AI-driven sustainability recommendations.

3.Establish Standards for Authenticity Audits: Require third-party certification of environmental authenticity claims in green marketing, similar to existing B-Corp or Fair Trade certification models. This addresses Level 2 transparency (authenticity) and may be particularly impactful for privacy-conscious consumers who are information-seeking but skeptical of self-reported claims.

8. Conclusion

Looking ahead, the integration of AI into green marketing is likely to intensify, driven by advances in machine learning, increasing availability of consumer data, and growing urgency of environmental challenges. In this context, understanding how to build and maintain trust with privacy-conscious consumers will become increasingly critical. Organizations that succeed in this endeavor will not only enhance their competitive position but also contribute to broader societal goals of sustainability and responsible technology use.

The implications extend beyond individual organizations to entire ecosystems of sustainability. As governments, NGOs, and businesses increasingly collaborate on environmental initiatives, data sharing across organizational boundaries becomes essential. Our findings suggest that building trust through transparency and authentic commitment can facilitate such cross-organizational data sharing, enabling more comprehensive and effective sustainability programs. However, this requires robust governance frameworks that ensure data is used appropriately and that all stakeholders are accountable for their data practices.

Furthermore, the study contributes to the emerging literature on responsible AI by demonstrating that transparency is not merely a regulatory requirement but a strategic asset for building consumer trust. Organizations that proactively embrace explainable AI and transparent data practices may gain competitive advantages in attracting privacy-conscious consumers who are willing to share data when they understand and trust how it will be used. This finding aligns with broader trends toward ethical AI and corporate social responsibility, suggesting that privacy-respecting practices can be both morally sound and commercially viable.

This study investigated how brand trust mediates the relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness in AI-driven green marketing contexts. Drawing on privacy calculus theory and trust-building frameworks, we surveyed 482 consumers and employed structural equation modeling to test our hypotheses. Results demonstrated that brand trust partially mediates the positive relationship between privacy concern and data-sharing willingness, challenging simplistic deterrence models. Additionally, AI transparency and environmental awareness emerged as significant antecedents of brand trust.

Our findings contribute to privacy calculus theory by demonstrating that in value-aligned contexts, trust can enable data sharing even when privacy concerns are present. Privacy-conscious consumers do not abandon their concerns but instead channel them into strategic, trust-dependent engagement with brands they perceive as trustworthy and environmentally authentic. This perspective offers a more nuanced understanding of privacy management strategies and highlights the importance of trust-building mechanisms in facilitating consumer engagement with data-intensive sustainability initiatives.

Practical implications include the importance of transparency about AI systems and data practices, authentic environmental commitment, and recognition that privacy-conscious consumers may be valuable engagement partners rather than obstacles. As organizations increasingly rely on AI-driven personalization to promote sustainable consumption, understanding how to build trust with privacy-conscious consumers becomes essential for both commercial success and environmental impact.

This research opens new avenues for understanding consumer behavior in the digital age, where privacy and sustainability intersect. Future studies should continue to explore how emerging technologies can be designed and deployed in ways that respect consumer privacy while advancing critical societal goals.