Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature search strategy

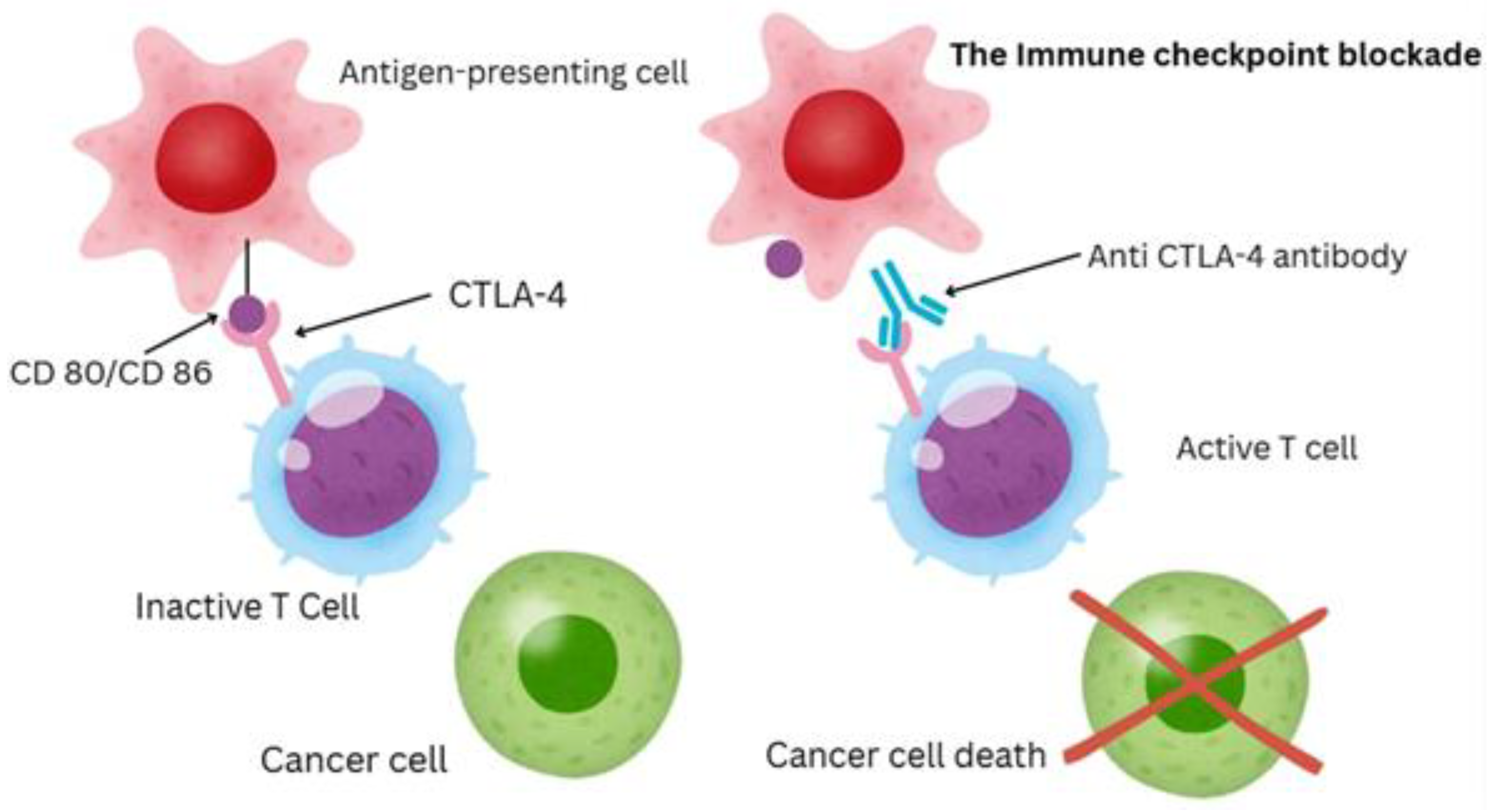

3. Immune Checkpoint Blockade: Mechanism and Clinical Relevance

4. Microbiota: A General Overview

6. Gut Mycobiome in Immunity and Cancer

6.1. Composition and Roles in Health and Disease

6.2. Fungi in Cancer and the “Tumor Mycobiome”

6.3. Mycobiome Influence on Cancer Immunotherapy (ICI Efficacy)

6.4. Fungal-Derived Immune Modulators (β-Glucans and Others)

7. Gut Virome in Immunity and Cancer

7.1. Composition of the Gut Virome and Baseline Role

7.2. Virome Alterations in Cancer and Therapy: Lessons from Virome Depletion

7.3. Clinical Observations: Virome and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Therapy

8. Modulation Strategies for the Gut Microbiome in ICI Therapy

8.1. Dietary Interventions

8.2. Prebiotics and Supplements

8.3. Probiotics and “Mycobiotics”

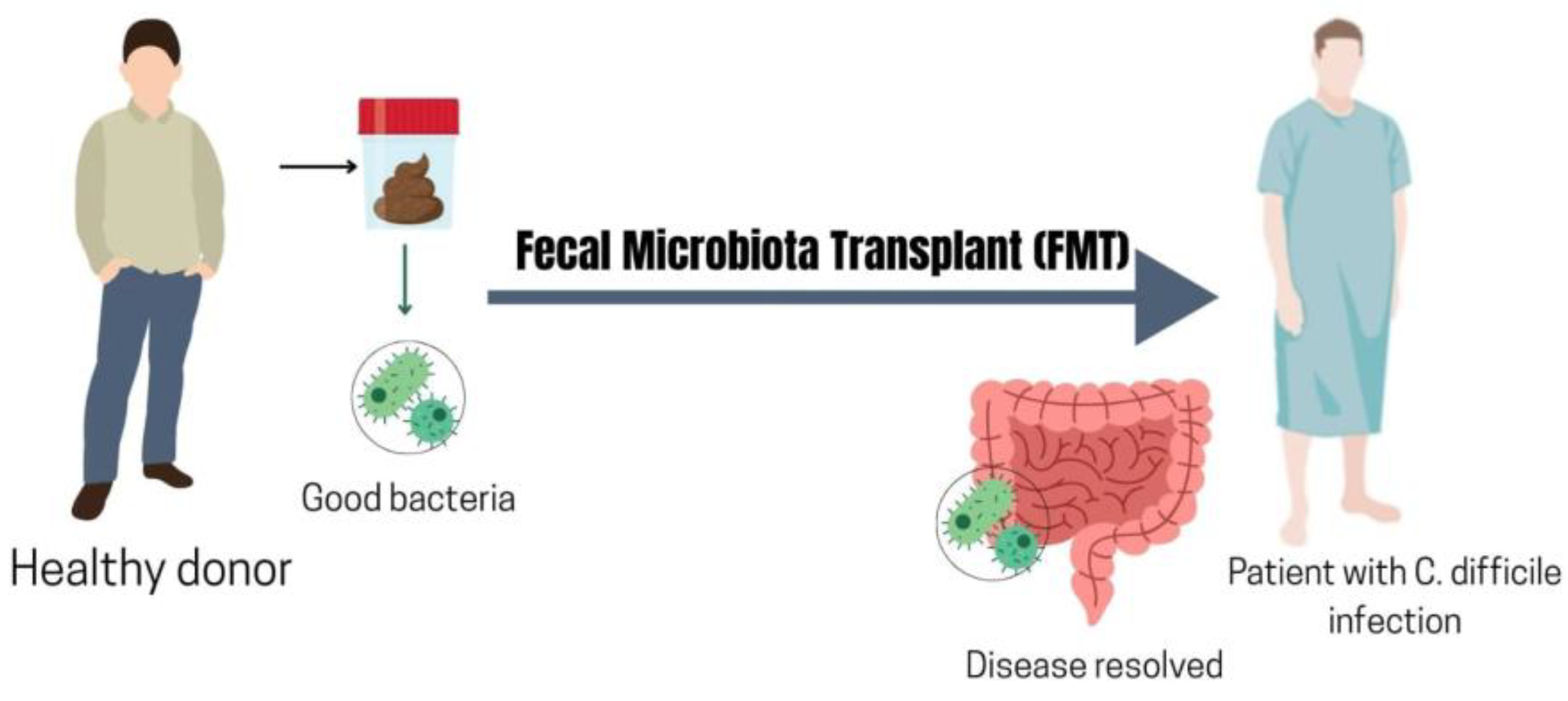

8.4. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

9. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45.

- Garg, P.; Pareek, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Next-generation immunotherapy: Advancing clinical applications in cancer treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Han, Z.; Ma, D. Immune checkpoint therapy for solid tumours: Clinical dilemmas and future trends. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 320. [CrossRef]

- Natanael, R.C.; Măruțescu, L.; Grădișteanu Pircalabioru, G. Immuno-oncology at the crossroads: Confronting challenges in the quest for effective cancer therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Adashek, J.J.; Moran, J.A.; Le, D.T.; Kurzrock, R. Lessons learned from a decade of immune checkpoint inhibition: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 43–58. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, L. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: Current researches in cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 727–742.

- Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Xi, Q.; Shen, H.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 451–472. [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Yahya, E.B.; Mohamed Ibrahim Mohamed, M.; Rashid, S.; Iqbal, M.O.; Kontek, R.; et al. Recent advances in molecular mechanisms of cancer immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, A.; Mustafa, A.S.; Hanif, A.; Tunio, J.H.; Hanif, S.N.M. Recent advances in cancer immunotherapy with a focus on FDA-approved vaccines and neoantigen-based vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 11. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, L.; Shan, B. Future of immune checkpoint inhibitors: Focus on tumor immune microenvironment. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1095. [CrossRef]

- Muthukutty, P.; Woo, H.Y.; Ragothaman, M.; Yoo, S.Y. Recent advances in cancer immunotherapy delivery modalities. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Nebhan, C.A.; Moslehi, J.J.; Balko, J.M. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Long-term implications of toxicity. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 254–267. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Yang, J.; Qian, G.; Sheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; et al. Treatment-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1391724. [CrossRef]

- Gazzaniga, F.; Dennis, L.K. The gut microbiome and cancer response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Clin. Invest. 2025, 135, eXXXXX.

- Xie, J.; Liu, M.; Deng, X.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ou, X.; et al. Gut microbiota reshapes cancer immunotherapy efficacy: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. iMeta 2024, 3, eXXX. [CrossRef]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836.

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; et al. Gut microbiota functions: Metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Hsu, R.; Rafizadeh, D.L.; Wang, L.; Bowlus, C.L.; Kumar, N.; et al. The gut ecosystem and immune tolerance. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 141, 103114. [CrossRef]

- Vétizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillère, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084. [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, R.; Jobin, C. Microbiota and cancer immunotherapy: In search of microbial signals. Gut 2018, 68, 385–388. [CrossRef]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.-L.; et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti–PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108. [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A.K.; McCulloch, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Chauvin, J.-M.; Morrison, R.M.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 595–602. [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Golan, T.; Wargo, J.A. Fecal microbiota transplantation as a means of overcoming immunotherapy-resistant cancers—Hype or hope? Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2021, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2020, 371, 602–609. [CrossRef]

- Verheijden, R.J.; van Eijs, M.J.M.; Paganelli, F.L.; Viveen, M.C.; Rogers, M.R.C.; Top, J.; et al. Gut microbiome and immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicity. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 216, 115221. [CrossRef]

- Chaput, N.; Lepage, P.; Coutzac, C.; Soularue, E.; Roux, K.L.; Monot, C.; et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1368–1379. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xie, M.; Lau, H.C.; Zeng, R.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; et al. Effects of gut microbiota on immune checkpoint inhibitors in multi-cancer and as microbial biomarkers for predicting therapeutic response. Med 2025, 6, 100530. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, M.; Sun, T.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, Y.; et al. Multi-kingdom gut microbiota analyses define bacterial–fungal interplay and microbial markers of pan-cancer immunotherapy across cohorts. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 1930–1943.e4. [CrossRef]

- Broecker, F.; Moelling, K. The roles of the virome in cancer. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 12.

- Swann, J.B.; Smyth, M.J. Immune surveillance of tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 1137–1146. [CrossRef]

- Archilla-Ortega, A.; Domuro, C.; Martín-Liberal, J.; Muñoz, P. Blockade of novel immune checkpoints and new therapeutic combinations to boost antitumor immunity. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Yang, F.; Huang, Z.Q.; Li, Y.Y.; Shi, H.Y.; Sun, Q.; et al. T cells, NK cells, and tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy and the current state of the art of drug delivery systems. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1199173. [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, N.; Crown, J.; Collins, D. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Key trials and an emerging role in breast cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 65, 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Gupta, M.; Sahasranaman, S. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: An introduction to the next-generation cancer immunotherapy. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 56, 157–169. [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, K.; Roudaia, L.; Buhlaiga, N.; Rincón, S.; Papneja, N.; Miller, W. A review of cancer immunotherapy: From the past, to the present, to the future. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 27, S87–S97. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, A.E.; Deshmukh, S.; Reddy, A.; Lightcap, J.; Hayes, M.; McClellan, S.; et al. Cancer immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and the gut microbiota. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Faget, J.; Peters, S.; Quantin, X.; Meylan, E.; Bonnefoy, N. Neutrophils in the era of immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002242. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Seok, S.H.; Yoon, H.Y.; Ryu, J.H.; Kwon, I.C. Advancing cancer immunotherapy through siRNA-based gene silencing for immune checkpoint blockade. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 204, 115306. [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Derosa, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Routy, B. The intimate relationship between gut microbiota and cancer immunotherapy. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 424–428. [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, D.; Kidd, A.; Ansel, S.; Ascierto, M.; Spiliopoulou, P. Oncogenic signalling pathways in cancer immunotherapy: Leader or follower in this delicate dance? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, S.E.; Sosman, J.A.; Chandra, S. Resistance mechanisms in melanoma to immune-oncologic therapy with checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 744–761.

- Hassel, J.C.; Zimmer, L.; Sickmann, T.; Eigentler, T.K.; Meier, F.; Mohr, P.; et al. Medical needs and therapeutic options for melanoma patients resistant to anti-PD-1-directed immune checkpoint inhibition. Cancers 2023, 15, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, R.I.; Gheorghe, A.S.; Zob, D.L.; Stanculeanu, D.L. The importance of predictive biomarkers and their correlation with the response to immunotherapy in solid tumors—Impact on clinical practice. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 9.

- Sankar, K.; Ye, J.; Li, Z.; Zheng, L.; Song, W.; Hu-Lieskovan, S. The role of biomarkers in personalized immunotherapy. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Fang, L. The role of the gut microbiota in tumor, immunity, and immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1–18.

- Lim, M.; Han, S.; Nam, Y.-D. Understanding the role of the gut microbiome in solid tumor responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors for personalized therapeutic strategies: A review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C.; Wu, C.-J.; Hung, Y.; Lin, C.-J.; Chao, Y.; Hou, M.; et al. Association of gut microbiota and metabolites with tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, eXXXX. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Johnson, D. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 306. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wu, L.; Han, L.; Zheng, X.; Tong, R.; Li, L.; et al. Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.-D.; Quan, W.-X.; Tang, X.-L.; Shi, W.-W.; Li, Q.; Li, R.J.; et al. Uncovering the flip side of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A comprehensive review of immune-related adverse events and predictive biomarkers. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 621–642. [CrossRef]

- Mallio, C.A.; Bernetti, C.; Cea, L.; Buoso, A.; Stiffi, M.; Vertulli, D.; et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: A comprehensive imaging-oriented review. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 4700–4723. [CrossRef]

- Di Dalmazi, G.; Ippolito, S.; Lupi, I.; Caturegli, P. Hypophysitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: A 10-year assessment. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 14, 381–398. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Qu, T. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related cutaneous adverse events. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 16, e149–e153. [CrossRef]

- Som, A.; Mandaliya, R.; Alsaadi, D.; Farshidpour, M.; Charabaty, A.; Malhotra, N.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: A comprehensive review. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 405–418. [CrossRef]

- Guitton, R.; Laparra, A.; Chanson, N.; Champiat, S.; Danlos, F.-X.; Michot, J.-M.; et al. Immune-related adverse events occurring rapidly after a single dose of immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, eXXXX. [CrossRef]

- Jayathilaka, B.; Mian, F.; Franchini, F.; Au-Yeung, G.; Iqbal, M.J. Cancer- and treatment-specific incidence rates of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 132, 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yao, J.; Yuan, G.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related new-onset thyroid dysfunction: A retrospective analysis using the US FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Oncologist 2022, 27, e126–e132. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, I.; Yabe, D. Best practices in the management of thyroid dysfunction induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur. Thyroid J. 2025, 14, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, A.E.; Coughlin, L.A.; Kim, J.; Froehlich, T.; Xie, Y.; Frenkel, E.P.; et al. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing and unbiased metabolomic profiling identify specific human gut microbiota and metabolites associated with immune checkpoint therapy efficacy in melanoma patients. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 848–855. [CrossRef]

- Baiden-Amissah, R.; Tuyaerts, S. Contribution of aging, obesity, and microbiota on tumor immunotherapy efficacy and toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3586. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, G.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Shao, N.; et al. Distribution of gut microbiota across intestinal segments and their impact on human physiological and pathological processes. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 47. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, F.; Jiang, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Bacterial–fungal interactions: Mutualism, antagonism, and competition. Life 2025, 15, 8. [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.C. The interplay between gut bacteria and the yeast Candida albicans. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1979877. [CrossRef]

- Easwaran, M.; Abdelrahman, F.; El-Shibiny, A.; Venkidasamy, B.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Sivalingam, P.; et al. Exploring bacteriophages to combat gut dysbiosis: A promising new frontier in microbiome therapy. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 208, 108008. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Kandalgaonkar, M.; Golonka, R.; Yeoh, B.; Vijay-Kumar, M.; Saha, P. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and host immunity: Impact on inflammation and immunotherapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2110. [CrossRef]

- Gierynska, M.; Szulc-Dabrowska, L.; Struzik, J.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P. Integrity of the intestinal barrier: The involvement of epithelial cells and microbiota—A mutual relationship. Animals 2022, 12, 2. [CrossRef]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 313–323. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Chehrazi-Raffle, A.; Placencio-Hickok, V.; Guan, M.; Hendifar, A.; Salgia, R. The gut microbiome and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: Preclinical and clinical strategies. Clin. Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 9. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fan, N.; Ma, S.X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, G. Gut microbiota dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, diseases, prevention, and therapy. MedComm 2025, 6, e70168. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.; Magar, A.T.; Shrestha, J.; Panth, N.; Idrees, S.; Sadaf, T.; et al. Influence of gut and lung dysbiosis on lung cancer progression and their modulation as promising therapeutic targets: A comprehensive review. MedComm 2024, 5, eXXX. [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Routy, B.; Daillère, L.; Bolte, L.; Wargo, J.; McQuade, J.; et al. Gut microbiota in immuno-oncology: A practical guide for medical oncologists with a focus on antibiotics stewardship. ASCO Educ. Book 2025, 45, e472902. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Hu, B.; He, J.; Fu, X.; Liu, N. Intratumor microbiome-derived butyrate promotes chemo-resistance in colorectal cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1510851. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Xu, D. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Mechanisms and new perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gamrath, L.; Pedersen, T.B.; Møller, M.V.; Volmer, L.; Holst-Christensen, L.; Vestermark, L.; et al. Role of the microbiome and diet for response to cancer checkpoint immunotherapy: A narrative review of clinical trials. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 45–58. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, K. Genotoxins: The mechanistic links between Escherichia coli and colorectal cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 4. [CrossRef]

- Buder-Bakhaya, K.; Hassel, J.C. Biomarkers for clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment—A review from the melanoma perspective and beyond. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1474. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, M.; Salehi, R.; Haghjooy Javanmard, S.; Rafiee, L.; Faraji, H.; Jafarpor, S.; et al. The dysbiosis signature of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer—Cause or consequences? A systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 194. [CrossRef]

- Khoudia, D.; Mbaye, B.; Ndir, S.; Favier, A.; Bercovici, M.; Jouvin, M.; et al. Coupling culturomics and metagenomics sequencing to characterize the gut microbiome of patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Gut Pathog. 2025, 17, 1–15.

- Carlson, R.D.; Flickinger, J.C., Jr.; Snook, A.E. Talkin’ toxins: From Coley’s to modern cancer immunotherapy. Toxins 2020, 12, 4. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Wu, Q.; Sun, S. Influence of microbiota on tumor immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 2264–2294. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, M.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Shao, X.; et al. Interplay between gut microbial communities and metabolites modulates pan-cancer immunotherapy responses. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 806–823.e6. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, L.; Hong, Z. Gut microbiota shapes cancer immunotherapy responses. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 1–14.

- Li, S.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W. Gut microbiota affects PD-L1 therapy and its mechanism in melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74, 1–14.

- Jiminez, V.; Yusuf, N. Role of the microbiome in immunotherapy of melanoma. Cancer J. 2023, 29, 70–74. [CrossRef]

- Usyk, M.; Pandey, A.; Hayes, R.; Moran, U.; Pavlick, A.; Osman, I.; et al. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei predict immune-related adverse events in immune checkpoint blockade treatment of metastatic melanoma. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Dubin, K.; Callahan, M.K.; Ren, B.; Khanin, R.; Viale, A.; Ling, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiome analyses identify melanoma patients at risk for checkpoint-blockade-induced colitis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10391. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, T.; Xu, J. Exploring fecal microbiota signatures associated with immune response and antibiotic impact in NSCLC: Insights from metagenomic and machine learning approaches. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Xu, J.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Exploring gut microbiome markers in predicting efficacy of immunotherapy against lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, eXXXX.

- Schwartz, D.J.; Rebeck, O.N.; Dantas, G. Complex interactions between the microbiome and cancer immune therapy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2019, 56, 567–585. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, J.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Akkermansia muciniphila: A potential booster to improve the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 13477–13494. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; McAllister, F. Too much water drowned the miller: Akkermansia determines immunotherapy responses. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100642. [CrossRef]

- Grenda, A.; Iwan, E.; Chmielewska, I.; Krawczyk, P.; Giza, A.; Bomba, A.; et al. Presence of Akkermansiaceae in gut microbiome and immunotherapy effectiveness in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. AMB Express 2022, 12, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Somodi, C.; Dora, D.; Horvath, M.; Szegvari, G.; Lohinai, Z. Gut microbiome changes and cancer immunotherapy outcomes associated with dietary interventions: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 756. [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.A.; Gallegos, A.A.; Ortega, J.A.; Sánchez, E.; Mayora, X.; Yocupicio, O.; et al. The interplay between the gut microbiome and immunotherapy in gastrointestinal malignancies: Mechanisms, clinical implications, and therapeutic potential. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. Stud. 2025, 5, 1–15.

- Xu, M.; Li, X.; Lau, H.C.; Yu, J. The gut microbiota in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1012–1031 . [CrossRef]

- Pei, B.; Peng, S.; Huang, C.; Zhou, F. Bifidobacterium modulation of tumor immunotherapy and its mechanism. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2024, 73, 94. [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Wang, T.; Tang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tang, D.; et al. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 1–12.

- Lee, P.-C.; Wu, C.-J.; Hung, Y.; Lin, C.-J.; Chen-Ta, C.; Lin, I.-C.; et al. Gut microbiota and metabolites associate with outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, eXXXX.

- Mao, J.; Wang, D.; Jiang, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. Gut microbiome is associated with the clinical response to anti-PD-1 based immunotherapy in hepatobiliary cancers. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, eXXXX.

- Peng, K.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yu, P.; Zeng, T.; Lin, C.; et al. The therapeutic promise of probiotic Bacteroides fragilis (BF839) in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1523754. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.-J.; Liu, L.; Huang, Z.; He, D.; Hu, Y. The gut microbiota modulates responses to anti–PD-1 and chemotherapy combination therapy and related adverse events in patients with advanced solid tumors. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1–15.

- Gupta, H.; Fatima, K.; Kaur, J. Understanding crosstalk between the gut and liver microbiome: Pathogenesis to therapeutic approaches in liver cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Joy, S.; Cortes, E.G.; Otsuji, T.; Chen, H.; Dy, G.; Segal, B.; et al. Fluctuations in gut microbiome composition during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. World J. Oncol. 2023, 14, 178–187.

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Q. Role of gut microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: From predictive biomarker to therapeutic target. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wargo, J.A.; Andrews, M.C.; Duong, C.P.M.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Iebba, V.; Chen, W.-S.; et al. Gut microbiota signatures are associated with toxicity to combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade. Nat. Med. 2020, 27, 1432–1441. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, B.; Chen, D.; et al. Gut microbiota composition in patients with advanced malignancies experiencing immune-related adverse events. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, D.; Fang, X.; et al. Relating gut microbiome and its modulating factors to immunotherapy in solid tumors: A systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2020, 11, 1–18.

- Usyk, M.; Huilin, R.B.; Kostic, R.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Ling, H.; Osman, I.; et al. Gut microbiome is associated with recurrence-free survival in patients with resected Stage IIIB-D or Stage IV melanoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. bioRxiv 2024, preprint.

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, N.; Meng, K.; Pan, F. Interaction between gut microbiota and immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1001623. [CrossRef]

- Velikova, T.; Krastev, B.; Lozenov, S.; Gencheva, R.; Peshevska-Sekulovska, M.; Nikolaev, G.; et al. Antibiotic-related changes in microbiome: The hidden villain behind colorectal carcinoma immunotherapy failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Derosa, L.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L.; Routy, B. The negative impact of antibiotics on outcomes in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy: A new independent prognostic factor? Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, X. Big lessons from the little Akkermansia muciniphila in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1524563. [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Carrillo, R.; Zengin, Z.; Pal, S. Microbiome modulation for the treatment of solid neoplasms. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 2734–2738. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Lu, Y.; Pan, G.; Ye, K.; Ma, Y.; Han, X.; et al. The commensal consortium of the gut microbiome is associated with favorable responses to anti-programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) therapy in thoracic neoplasms. Cancer Biol. Med. 2021, 18, 1040–1052.

- Xu, Y.; Pan, G.; Shi, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, X.-J. Gut microbiota as a prognostic biomarker for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with anti-PD-1 therapy. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1–12.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zou, H.; Han, Z.; Xie, T.; Zhang, B.; et al. Correlation of the gut microbiome and immune-related adverse events in gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, B.; Chen, M.; et al. Gut microbiome contributes to the development of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Sakurai, T.; Velasco, M.D.D.; Nagai, T.; Chikugo, T.; Ueshima, K.; et al. Intestinal microbiota and gene expression reveal similarity and dissimilarity between immune-mediated colitis and ulcerative colitis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Pi, Z.; Chen, S.; Kou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, R.; Han, H.; et al. The gut microbiome is associated with clinical response to anti–PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1251–1261.

- Sun, Y.-C.; Lee, P.-C.; Kuo, Y.; Wang, W.-K.; Chang, C.-C.; Chen, L.; et al. An exploratory study for the association of gut microbiome with efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2021, 8, 809–822.

- Iliev, I.D.; Cadwell, K. Effects of intestinal fungi and viruses on immune responses and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L. The fungal mycobiome: A new hallmark of cancer revealed by pan-cancer analyses. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 50. [CrossRef]

- Dohlman, A.B.; Klug, J.; Mesko, M.; Gao, I.H.; Lipkin, S.M.; Shen, X.; et al. A pan-cancer mycobiome analysis reveals fungal involvement in gastrointestinal and lung tumors. Cell 2022, 185, 3807–3822.e12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Li, S.; Ogamune, K.J.; Ahmed, A.A.; Kim, I.H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Fungi in the gut microbiota: Interactions, homeostasis, and host physiology. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1. [CrossRef]

- Sokol, H.; Leducq, V.; Aschard, H.; Pham, H.P.; Jegou, S.; Landman, C.; et al. Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD. Gut 2017, 66, 1039–1048. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Sendid, B.; Hoarau, G.; Colombel, J.-F.; Poulain, D.; Ghannoum, M.A. Mycobiota in gastrointestinal diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 77–87.

- Chehoud, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cotter, P.D.; Scanlan, P.D. Forgotten fungi—The gut mycobiome in human health and disease. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 479–511. [CrossRef]

- Hoarau, G.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Hager, C.; Chandra, J.; Retuerto, M.A.; et al. Bacteriome and mycobiome interactions underscore microbial dysbiosis in familial Crohn's disease. mBio 2016, 7, e01250-16. [CrossRef]

- Briard, B.; Fontaine, T.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; Gow, N.A.R.; Papon, N. Fungal cell wall components modulate our immune system. Cell Surf. 2021, 7, 100067. [CrossRef]

- Marakalala, M.J.; Kerrigan, A.M.; Brown, G.D. Dectin-1: A role in antifungal defense and consequences of genetic polymorphisms in humans. Mamm. Genome 2011, 22, 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Camilli, G.; Tabouret, G.; Quintin, J. The complexity of fungal β-glucan in health and disease: Effects on the mononuclear phagocyte system. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 673. [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.D.; Funari, V.A.; Taylor, K.D.; Nguyen, Q.; Reyes, C.N.; Strom, S.P.; et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science 2012, 336, 1314–1317. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Feng, Y.; Sun, T.; Xu, J. Tumor-related fungi and crosstalk with gut fungi in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 977–994. [CrossRef]

- Narunsky-Haziza, L.; Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Livyatan, I.; Asraf, O.; Martino, C.; Nejman, D.; et al. Pan-cancer analyses reveal cancer-type-specific fungal ecologies and bacteriome interactions. Cell 2022, 185, 3789–3806.e17. [CrossRef]

- Aykut, B.; Pushalkar, S.; Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Abengozar, R.; Kim, J.I.; et al. The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 2019, 574, 264–267. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, M. Do fungi lurking inside cancers speed their growth? Nature 2022, 604, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, D.D.; Feng, J.; Liao, Z.J.; Shu, X.L.; Yang, R.M.; et al. Intestinal fungal signatures and their impact on immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy: A multi-cohort meta-analysis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 188. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Serradell, L.; Liu-Tindall, J.; Planells-Romeo, V.; Aragon-Serrano, L.; Isamat, M.; Gabaldon, T.; et al. The human mycobiome: Composition, immune interactions, and impact on disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 15. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Ye, M.; Song, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Gut microbiota and SCFAs improve the treatment efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy in NSCLC. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 1–14.

- Liu, X.F.; Shao, J.H.; Liao, Y.T.; Wang, L.N.; Jia, Y.; Dong, P.J.; et al. Regulation of short-chain fatty acids in the immune system. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1186892. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, L.; et al. Characterizations of multi-kingdom gut microbiota in immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, eXXXX. [CrossRef]

- Noorbakhsh Varnosfaderani, S.M.; Ebrahimzadeh, F.; Akbari Oryani, M.; Khalili, S.; Almasi, F.; Mosaddeghi Heris, R.; et al. Potential promising anticancer applications of beta-glucans: A review. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR2023XXXX. [CrossRef]

- Geller, A.; Shrestha, R.; Yan, J. Yeast-derived beta-glucan in cancer: Novel uses of a traditional therapeutic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3618. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pan, J.; Xiang, W.; You, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Beta-glucan: A potent adjuvant in immunotherapy for digestive tract tumors. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1424261. [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Lv, Y.; et al. A beta-1,3/1,6-glucan enhances anti-tumor effects of PD1 antibody by reprogramming tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 134660. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bai, Y.; Pei, J.; Li, D.; Pu, X.; Zhu, W.; et al. Beta-glucan combined with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade for immunotherapy in patients with advanced cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 887457. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; He, X.; Xue, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, C.; Qi, C.; et al. An exploratory clinical study of beta-glucan combined with camrelizumab and SOX chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced gastric adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1448485. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ahn, H.; Park, H. A review on the role of gut microbiota in immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer. Mamm. Genome 2021, 32, 223–231. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, L.; Prathikanti, R.; Ma, B.; Mattson, P.; Kedrowski, D.; Lowe, J.; et al. A multicenter, open-label, phase II study of PGG beta-glucan and pembrolizumab in patients with advanced melanoma (MEL) following progression on treatment with checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) or triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) failing front-line chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, TPS3105. [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Lau, H.C.; Yu, J. Modulating gut microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: Harnessing microbes to enhance treatment efficacy. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101478. [CrossRef]

- Szostak, N.; Handschuh, L.; Samelak-Czajka, A.; Tomela, K.; Pietrzak, B.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Gut mycobiota dysbiosis is associated with melanoma and response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2024, 12, 427–439. [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, M.; Hohl, T. Fungal infections associated with the use of novel immunotherapeutic agents. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 7, 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Sugimura, N.; Burgermeister, E.; Ebert, M.P.; Zuo, T.; Lan, P. The gut virome: A new microbiome component in health and disease. eBioMedicine 2022, 81, 104113. [CrossRef]

- Lathakumari, R.H.; Vajravelu, L.K.; Gopinathan, A.; Vimala, P.B.; Panneerselvam, V.; Ravi, S.S.S.; et al. The gut virome and human health: From diversity to personalized medicine. Eng. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 100191. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V.L.; Fitzpatrick, A.D.; Islam, Z.; Maxwell, K.L. The diverse impacts of phage morons on bacterial fitness and virulence. Adv. Virus Res. 2019, 103, 1–31.

- Mahmud, M.R.; Tamanna, S.K.; Akter, S.; Mazumder, L.; Akter, S.; Hasan, M.R.; et al. Role of bacteriophages in shaping gut microbial community. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2390720.

- Duerkop, B.A.; Hooper, L.V. Resident viruses and their interactions with the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 654–659. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.A.; Holtz, L.R. Gut virome in early life: Origins and implications. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 55, 101233. [CrossRef]

- Kernbauer, E.; Ding, Y.; Cadwell, K. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature 2014, 516, 94–98. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wen, B.; Yang, X.; Zhong, W.; et al. Gut virome dysbiosis impairs antitumor immunity and reduces 5-fluorouracil treatment efficacy for colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1501981. [CrossRef]

- Pescarmona, R.; Mouton, W.; Walzer, T.; Dalle, S.; Eberhardt, A.; Brengel-Pesce, K.; et al. Evaluation of TTV replication as a biomarker of immune checkpoint inhibitors efficacy in melanoma patients. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255972. [CrossRef]

- Sanyour, J.; Awada, B.; Mattar, A.; Matar, R.; Yaqoub, N.; Al Haddabi, I.; et al. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr virus reactivation in steroid-refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor colitis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2025, 19, 1276–1282. [CrossRef]

- Harper, H.; Newman, J.; Sun, W.; MacKenzie, E. Cytomegalovirus hepatitis after treatment with dostarlimab for colorectal cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2025, 18, eXXXX. [CrossRef]

- Iwamuro, M.; Tanaka, T.; Makimoto, G.; Ichihara, E.; Hiraoka, S. Two cases of cytomegalovirus colitis during the treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. Cureus 2024, 16, e63308. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Zhou, H.; Du, D.; Zhu, K.; et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 87. [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulou, A.; Samarkos, M.; Diamantopoulos, P.; Vourlakou, C.; Ziogas, D.C.; Avramopoulos, P.; et al. Cytomegalovirus infections in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for solid malignancies. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad164. [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.A.; Muhsen, I.N.; Anand, K.; Xu, J.; Umoru, G.; Arain, A.N.; et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. 2021, 44, 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.A.; Kronenberg, K.; Riquelme, P.; Wenzel, J.J.; Glehr, G.; Schilling, H.L.; et al. Virus-specific memory T cell responses unmasked by immune checkpoint blockade cause hepatitis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1439.

- Seki, M.; Kitano, S.; Suzuki, S. Neurological disorders associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: An association with autoantibodies. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 769–775. [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Jia, A.; Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; et al. Microbiome meets immunotherapy: Unlocking the hidden predictors of immune checkpoint inhibitors. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 1–14.

- Zhou, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, B.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Anti-PD-1 therapy achieves favorable outcomes in HBV-positive non-liver cancer. Oncogenesis 2023, 12, 22. [CrossRef]

- Chesney, J.A.; Puzanov, I.; Collichio, F.A.; Singh, P.; Milhem, M.M.; Glaspy, J.; et al. Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone for advanced melanoma: 5-year final analysis of a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase II trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, eXXXX. [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Gastman, B.; Gogas, H.; Rutkowski, P.; Long, G.V.; Chaney, M.F.; et al. Open-label, phase II study of talimogene laherparepvec plus pembrolizumab for the treatment of advanced melanoma that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy: MASTERKEY-115. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 207, 114120. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Dummer, R.; Puzanov, I.; VanderWalde, A.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Michielin, O.; et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 170, 1109–1119.e10. [CrossRef]

- Harrington, K.; Freeman, D.J.; Kelly, B.; Harper, J.; Soria, J.-C. Optimizing oncolytic virotherapy in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 689–706. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.; Thomas, M.; Dougan, M. Diagnosis and management of hepatitis in patients on checkpoint blockade. Oncologist 2018, 23, 991–997. [CrossRef]

- Tagliamento, M.; Remon, J.; Giaj Levra, M.; De Maria, A.; Bironzo, P.; Besse, B.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer and infection by hepatitis B or C virus: A perspective through the results of a European survey. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2023, 4, 100446. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Ezemenari, S.; Liaukovich, M.; Richard, I.; Boris, A. A rare case of pembrolizumab-induced reactivation of hepatitis B. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2018, 2018, 5985131. [CrossRef]

- Cianci, R.; Caldarelli, M.; Brani, P.; Bosi, A.; Ponti, A.; Giaroni, C.; et al. Cytokines meet phages: A revolutionary pathway to modulating immunity and microbial balance. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 5. [CrossRef]

- Champagne-Jorgensen, K.; Luong, T.; Darby, T.; Roach, D.R. Immunogenicity of bacteriophages. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 1058–1071.

- Spencer, C.N.; McQuade, J.L.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; McCulloch, J.A.; Vétizou, M.; Cogdill, A.P.; et al. Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science 2021, 374, 1632–1640. [CrossRef]

- Pala, B.; Trzeciak, K.; Olejnik-Schmidt, A.; Gapska, Ł.; Mackiewicz, J.; Kaczmarek, M.; et al. A clinical outcome of the anti-PD-1 therapy of melanoma in Polish patients is mediated by population-specific gut microbiome composition. Cancers 2022, 14, 1–20.

- Grafanaki, K.; Mavridis, A.; Anastogianni, A.; Boumpas, A.; Pappa, E.; Sideris, C. Nutrition and diet patterns as key modulators of metabolic reprogramming in melanoma immunotherapy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1–20.

- Severino, A.; Tohumcu, E.; Tamai, L.; Dargenio, P.; Porcari, S.; Rondinella, D.; et al. The microbiome-driven impact of western diet in the development of noncommunicable chronic disorders. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2024, 72, 101923. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Montero, C.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; Gomez-Lahoz, A.M.; Pekarek, L.; Castellanos, A.J.; Noguerales-Fraguas, F.; et al. Nutritional components in western diet versus Mediterranean diet at the gut microbiota–immune system interplay: Implications for health and disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2. [CrossRef]

- Statovci, D.; Aguilera, M.; MacSharry, J.; Melgar, S. The impact of Western diet and nutrients on the microbiota and immune response at mucosal interfaces. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 838. [CrossRef]

- Zeb, F.; Osaili, T.; Obaid, R.S.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; et al. Gut microbiota and time-restricted feeding/eating: A targeted biomarker and approach in precision nutrition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2. [CrossRef]

- Popa, A.D.; Nita, O.; Gherasim, A.; Enache, A.I.; Caba, L.; Mihalache, L.; et al. A scoping review of the relationship between intermittent fasting and the human gut microbiota: Current knowledge and future directions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shao, N.; Qiu, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, C.; Wan, J.; et al. Intestinal microbiota: A bridge between intermittent fasting and tumors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115484. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Lv, X.; Hu, L.; Li, W.; Zi, M.; et al. Impact of diets on response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) therapy against tumors. Life 2022, 12, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Stachowska, E.; Kucharski, R.; Wisniewski, P.; Ulasinski, P.; Stanczak, M.; et al. The impact of enteral immunonutrition on gut microbiota in colorectal cancer and gastric cancer patients in the preoperative period—Preliminary results of randomized clinical trial. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1606187. [CrossRef]

- Bolte, L.A.; Lee, K.A.; Bjork, J.R.; Leeming, E.R.; Campmans-Kuijpers, M.J.E.; de Haan, J.J.; et al. Association of a Mediterranean diet with outcomes for patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade for advanced melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 705–709. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Hussain, N.; Hameed, Z.; Lin, L. Elucidating the role of diet in maintaining gut health to reduce the risk of obesity, cardiovascular and other age-related inflammatory diseases: Recent challenges and future recommendations. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2297864. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wymond, B.; Tandon, H.; Belobrajdic, D.P. Swapping white for high-fibre bread increases faecal abundance of short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria and microbiome diversity: A randomized, controlled, decentralized trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 7. [CrossRef]

- McCrory, C.; Lenardon, M.; Traven, A. Bacteria-derived short-chain fatty acids as potential regulators of fungal commensalism and pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 1106–1118. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Aschenbrenner, D.; Yoo, J.Y.; Zuo, T. The gut mycobiome in health, disease, and clinical applications in association with the gut bacterial microbiome assembly. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e969–e983. [CrossRef]

- Gașpar, B.S.; Roșu, O.; Enache, R.; Manciulea, M.; Pavelescu, L.; Crețoiu, S. Gut mycobiome: Latest findings and current knowledge regarding its significance in human health and disease. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Liu, C.-G.; Zang, D.; Chen, J. Gut microbiota and dietary intervention: Affecting immunotherapy efficacy in non–small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Meslier, V.; Laiola, M.; Roager, H.M.; De Filippis, F.; Roume, H.; Quinquis, B.; et al. Mediterranean diet intervention in overweight and obese subjects lowers plasma cholesterol and causes changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome independently of energy intake. Gut 2020, 69, 1258–1268. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Rampelli, S.; Jeffery, I.B.; Santoro, A.; Neto, M.; Capri, M.; et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: The NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut 2020, 69, 1218–1228. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; D’Angelo, S. Gut microbiota modulation through Mediterranean diet foods: Implications for human health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 6. [CrossRef]

- Abrignani, V.; Salvo, A.; Pacinella, G.; Tuttolomondo, A. The Mediterranean diet, its microbiome connections, and cardiovascular health: A narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mitsou, E.K.; Kakali, A.; Antonopoulou, S.; Mountzouris, K.C.; Yannakoulia, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the gut microbiota pattern and gastrointestinal characteristics in an adult population. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1645–1655. [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.; Denizot, J.; Thevenot, J.; Martinez-Medina, M.; Massier, S.; Sauvanet, P.; et al. Western diet induces a shift in microbiota composition enhancing susceptibility to adherent-invasive E. coli infection and intestinal inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19032. [CrossRef]

- Buttar, J.; Kon, E.; Lee, A.; Kaur, G.; Lunken, G. Effect of diet on the gut mycobiome and potential implications in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, S.; Coen, M.; Leidi, A.; Schrenzel, J. The human gut mycobiome and the specific role of Candida albicans: Where do we stand, as clinicians? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.; Ernst, A.L.; Vorobyev, A.; Beltsiou, F.; Zillikens, D.; Bieber, K.; et al. Impact of diet and host genetics on the murine intestinal mycobiome. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 834. [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, G.; D’Elia, M.; De Prisco, M.; Folliero, V.; Marino, C.; D’Ursi, A.; et al. Modulation of gut bacterial and fungal microbiota in fibromyalgia patients following a carb-free oloproteic diet: Evidence for Candida suppression and symptom improvement. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 9. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Xie, L.; Chen, W.; Qin, J.; Zhang, J.; Lei, M.; et al. Dynamics of the gut bacteria and fungi accompanying low-carbohydrate diet-induced weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 846378. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.-W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 73. [CrossRef]

- Ducarmon, Q.R.; Grundler, F.; Le Maho, Y.; Wilhelmi de Toledo, F.; Zeller, G.; Habold, C.; et al. Remodelling of the intestinal ecosystem during caloric restriction and fasting. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 832–844. [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, M.; Sharma, S.; Caldwell, J.L.; Smith, N.J.; Gomes, C.K.; Bloomer, R.J.; et al. Time of feeding alters obesity-associated parameters and gut bacterial communities, but not fungal populations, in C57BL/6 male mice. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzz145. [CrossRef]

- Kadyan, S.; Park, G.; Singh, P.; Arjmandi, B.; Nagpal, R. Prebiotic mechanisms of resistant starches from dietary beans and pulses on gut microbiome and metabolic health in a humanized murine model of aging. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1106463. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E.; Plazy, C.; Richard, M.-L.; Suau, A.; Mangin, I.; Cornet, M.; et al. Inulin prebiotic reinforces host cancer immunosurveillance via γδ T cell activation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1104224. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.L.; Alvarado, D.A.; Swanson, K.S.; Holscher, H.D. The prebiotic potential of inulin-type fructans: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 492–529. [CrossRef]

- Alves-Santos, A.M.; Sugizaki, C.S.A.; Lima, G.C.; Naves, M.M.V. Prebiotic effect of dietary polyphenols: A systematic review. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 74, 104169. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, K.; Liu, G.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Microbial metabolite butyrate promotes anti-PD-1 antitumor efficacy by modulating T cell receptor signaling of cytotoxic CD8 T cell. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2249143. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ran, X.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Huang, B.; et al. Sodium butyrate inhibits inflammation and maintains epithelium barrier integrity in a TNBS-induced inflammatory bowel disease mice model. EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 317–325. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Zheng, P.; Mao, X.; et al. Fungi in gastrointestinal tracts of human and mice: From community to functions. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 75, 821–829. [CrossRef]

- Galus, L.; Michalak, M.; Lorenz, M.; Stoinska-Swiniarek, R.; Tusien Malecka, D.; Galus, A.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation increases objective response rate and prolongs progression-free time in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer 2023, 129, 2047–2055. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, C.; Li, Z.; et al. Vitamin D, gut microbiota, and cancer immunotherapy—A potentially effective crosstalk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1–20.

- Wu, X.Z.; Wen, Z.G.; Hua, J.L. Effects of dietary inclusion of Lactobacillus and inulin on growth performance, gut microbiota, nutrient utilization, and immune parameters in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4656–4663. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Ji, G.; Zhang, L. Immunomodulatory effects of inulin and its intestinal metabolites. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1224092. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Gao, G.; Hu, J.; Yu, J. Gut microbiome in modulating immune checkpoint inhibitors. eBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104162. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.Y.; Fu, Z.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q.W.; An, J.X.; et al. Probiotics functionalized with a gallium–polyphenol network modulate the intratumor microbiota and promote anti-tumor immune responses in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7096. [CrossRef]

- Danne, C.; Sokol, H. Butyrate, a new microbiota-dependent player in CD8+ T cells immunity and cancer therapy? Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100328. [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Lev-Ari, S. Targeting the gut microbiome to improve immunotherapy outcomes: A review. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, D.; Nigam, P. Biotherapy using probiotics as therapeutic agents to restore the gut microbiota to relieve gastrointestinal tract inflammation, IBD, IBS and prevent induction of cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Dash, J.; Kancharla, S.; Kolli, P.; Mahajan, D.; Senapati, S.; et al. Probiotics: A promising candidate for management of colorectal cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Rukavina, L.; Golčić, M.; Mikolasevic, I. The relationship between the modulation of intestinal microbiota and the response to immunotherapy in patients with cancer. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hamza, T.; Yu, H.; Saint Fleur, A.; et al. A probiotic yeast-based immunotherapy against Clostridioides difficile infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaba0375. [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B.; Dibazar, S.P.; Allahyari, S.; Javadi, M.; Amani, Z.; Farasat, A.; et al. Anticancer properties of probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii supernatant on human breast cancer cells. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 1130–1138. [CrossRef]

- Rebeck, O.N.; Wallace, M.J.; Prusa, J.; Ning, J.; Evbuomwan, E.M.; Rengarajan, S.; et al. A yeast-based oral therapeutic delivers immune checkpoint inhibitors to reduce intestinal tumor burden. Cell Chem. Biol. 2025, 32, 98–110.e7. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Xie, M.Z. A review of a potential and promising probiotic candidate—Akkermansia muciniphila. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 1813–1822.

- Zhang, T.; Li, Q.; Cheng, L.; Buch, H.; Zhang, F. Akkermansia muciniphila is a promising probiotic. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1109–1125. [CrossRef]

- Paaske, S.E.; Baumwall, S.M.D.; Rubak, T.; Birn, F.H.; Ragard, N.; Kelsen, J.; et al. Real-world effectiveness of fecal microbiota transplantation for first or second Clostridioides difficile infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 23, 602–611.e8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; An, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chu, Q.; Wei, J.; Wang, B.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: No longer cinderella in tumour immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 2024, 100, 104967. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, J.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fu, S.; et al. Targeted modulation of gut and intra-tumor microbiota to improve the quality of immune checkpoint inhibitor responses. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 282, 127668. [CrossRef]

- Chacon, J.; Faizuddin, F.; McKee, J.C.; Sheikh, A.; Vasquez, V.M., Jr.; Gadad, S.S.; et al. Unlocking the microbial symphony: The interplay of human microbiota in cancer immunotherapy response. Cancers 2025, 17, 5. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; He, L.; Jia, A.; Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Yu, L.; et al. Microbiota boost immunotherapy? A meta-analysis dives into fecal microbiota transplantation and immune checkpoint inhibitors. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 1–15.

- Oh, B.; Boyle, F.; Pavlakis, N.; Clarke, S.; Eade, T.; Hruby, G.; et al. The gut microbiome and cancer immunotherapy: Can we use the gut microbiome as a predictive biomarker for clinical response in cancer immunotherapy? Cancers 2021, 13, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Cai, Y. Faecal microbiota transplantation enhances efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors therapy against cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 5362–5375. [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Favier, M.; Iebba, V.; Alou, M.T.; Pessione, E.; et al. Gut bacteria composition drives primary resistance to cancer immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma patients. Eur. Urol. 2020, 78, 195–206. [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Waters, N.R.; Smith, N.; Dai, A.; Slingerland, J.; Aleynick, N.; et al. Immune-related colitis is associated with fecal microbial dysbiosis and can be mitigated by fecal microbiota transplantation. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2024, 12, 308–321. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, M.; Li, C.; Peng, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation effectively cures a patient with severe bleeding immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis and a short review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 913217. [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Taxon/Feature | Association with ICI Outcomes | Key References |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Enriched in responders to PD-1/PD-L1 therapy; absence linked to inferior ICI efficacy. Fecal transfer of Akkermansia-rich microbiota improved anti-PD-1 responses in mice. | [24,29,32,94,95,96,97,98,99,102,108,117,118,119] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Consistently enriched in ICI responders across multiple cancers. Produces SCFAs that support T effector and T reg cell metabolism. High baseline abundance is linked to better tumor control (pro-immune environment) but also associated with higher risk of ipilimumab-colitis in melanoma. Illustrates immunity–toxicity trade-off. | [30,31,32,39,98,99,106,114] |

| Bacteroides spp. | Certain Bacteroides are linked to lower GI toxicity: Patients with Bacteroidetes-rich microbiomes had less CTLA-4–induced colitis. B. fragilis produces polysaccharide A which induces regulatory T-cells and was shown to protect against colitis in mice. B. fragilis (and other Bacteroides) also enhanced anti-CTLA-4 tumor responses in preclinical models. However, in some anti–PD-1 studies, non-responders showed higher relative abundance of Bacteroidales showing a context-dependent effect. | [20,39,82,89,90,91,92,105,106,110,111,120,121,122,123,124] |

| Bifidobacterium spp. | Several Bifidobacterium species correlate with improved anti-tumor efficacy. In preclinical models, Bifidobacterium augmented anti–PD-L1 therapy by enhancing dendritic cell function. In patients, higher Bifidobacterium abundance has been noted in melanoma responders. Produces metabolites that stimulate T-cell activity. Not prominently linked to irAEs; generally considered immunostimulatory yet gut friendly. | [21,23,82,93,99,100,101,111,118,122,125] |

| High gut microbiota diversity | Diverse, well-balanced microbiomes are associated with better clinical response to ICIs (observed in melanoma, lung, kidney cancers). Such microbiomes typically include multiple SCFA producers and immunomodulatory taxa. High diversity may also be protective against single-species overgrowth that triggers colitis. Low diversity, dysbiosis – often caused by antibiotics or illness – correlates with poor response and higher risk of complications. | [25,29,39,97,106] |

| Pathobiont enrichment | Overrepresentation of opportunistic bacteria is a red flag for toxicity. Patients with baseline gut expansion of pathobionts had higher odds of severe irAEs. These organisms can provoke inflammation and thrive when beneficial flora are depleted. A post-ICI bloom of pathobionts (and concurrent drop in Clostridial commensals) has been observed at colitis onset. Such dysbiosis likely both predisposes to and results from mucosal inflammation. | [29,116] |

| Fungal Taxon | Association with ICI Efficacy/Toxicity | Key References |

| Schizosaccharomyces octosporus | Enriched in ICI responders in a pan-cancer analysis. A fungal signature including S. octosporus predicted treatment response with high accuracy as this yeast was largely absent in non-responders. It may ferment dietary fibers into short-chain fatty acids, indirectly boosting anti-tumor immunity. Not known to cause disease; its presence is considered beneficial. | [32,143,155] |

| Candida albicans | Mixed effects: Identified as part of a multi-kingdom predictor mode. Moderate colonization might help “prime” immunity, but overgrowth is often a sign of dysbiosis. In responder/non-responder comparisons, C. albicans was generally higher in non-responders, suggesting that an overabundance could be a negative factor for efficacy. | [32,143,156] |

| Core fungal set (n=26) predicted response (AUC 0.87), and multi-kingdom (20 fungi + 17 bacteria) improved AUC to 0.89 | Clear non-responder fungi: Pseudocercospora musae, Daedalea quercina, Lachancea mirantina, Lomentospora prolificans, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Verticillium nonalfalfae; Clear responder fungi: Trichophyton benhamiae, Cryptococcus amylolentus, Suillus clintonianus, Pseudogymnoascus sp. 05NY08, Schizosaccharomyces octosporus, Podospora anserina, (Verticillium longisporum modestly) |

[32] |

| Saccharomyces paradoxus, Malassezia restricta | Saccharomyces paradoxus - ↑Efficacy (better anti-PD-1 response), Malassezia restricta - ↓Efficacy (worse response) | (143) |

| Overall fungal diversity | Higher mycobiome diversity before ICI therapy has been associated with better treatment outcomes, although the effect size is modest. A rich fungal community might indicate a resilient gut ecosystem. There is no firm evidence that higher fungal diversity increases irAE risk; rather, loss of fungal diversity often accompanies antibiotic use and may be a marker of microbiome perturbation. | (142, 146) |

| Opportunistic fungal blooms | Some reports note that patients who develop severe irAEs have expansion of fungi like Candida albicans, Aspergillus spp., Pneumocystis jirovecii or Fusarium spp., leading to ↑Toxicity. Typically occurred with high-dose immunosuppression for irAEs and/or lymphopenia | (157) |

| Viral Factor | Association with ICI Efficacy/Toxicity | References |

| High gut virome diversity | Unlike bacteria/fungi, no specific enteric virus has been identified as a positive or negative predictor of ICI response in humans. Some hypothesize that a diverse gut virome could continually stimulate the immune system, potentially aiding tumor surveillance. However, studies integrating virome analysis have not found strong, consistent differences in viral populations between responders and non-responders. | [32,33,146,159] |

| Blood Anellovirus load/diversity | Anellovirus (TTV) load tracks immune competence—it typically rises with immunosuppression and can reflect host immune tone. In a melanoma anti–PD-1 cohort, TTV load did not differ between responders and non-responders at baseline and didn’t change with therapy, arguing against a simple anellovirus–ICI efficacy link. | [166] |

| Oncolytic virus therapy in combination | Oncolytic viruses can inflame the tumor and attract immune cells. Trials combining oncolytic viruses with ICIs have shown synergistic efficacy. The success of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC, a modified HSV) in melanoma supports the concept that introducing certain viruses to the tumor microenvironment can enhance checkpoint inhibitor activity. This underscores how viruses can modulate ICI outcomes by provoking anti-tumor immune responses. | [177,178,179,180] |

| Latent virus reactivation | Risk factor for toxicity: ICIs can remove immune checks on virus-specific T cells, leading to reactivation of latent infections. For example, PD-1 blockade in hepatitis B carriers can trigger fulminant hepatitis from viral reactivation. Similarly, cases of immune-related hepatitis and myocarditis have been linked to T-cell responses against latent viruses like EBV or CMV in affected tissues. These events suggest that part of irAE pathology in some patients may be an immune attack on cells harboring latent viruses. Patients with high viral antigen burden in certain organs could be predisposed to organ-specific irAEs when treated with ICIs. | [4,167,168,169,170,171,172,181,182,183] |

| Bacteriophages | Emerging interest in bacteriophages which shape the bacterial microbiome. Shifts in the phage community could indirectly affect bacterial composition and thus ICI outcomes. For instance, a rise in phages that target beneficial bacteria might precipitate dysbiosis associated with poor ICI response or colitis. Research in this area is in early stages, and specific phage dynamics in ICI patients remain largely uncharacterized. |

[25,155,184,185] |

| Dietary Intervention | Microbial Effects | Key Refrences |

| High-fiber, plant-rich diet | Increases SCFA-producers: Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium spp., Akkermansia muciniphila, Ruminococcaceae. Reduces overgrowth of Candida albicans; supports a balanced mycobiome. | [78,186,198,199,200,201,202,203] |

| Mediterranean diet | Promotes microbial diversity and beneficial taxa similar to high-fiber diets. Associated with lower pro-inflammatory biomarkers; although some studies found an increase in Candida albicans growth. | [78,98,190,198,202,204,205,206,207,208] |

| Western diet | Increases bile-tolerant and potentially harmful bacteri; decreases beneficial fiber-utilizers. Fuels Candida spp. overgrowth – higher gut Candida load can drive Th17 inflammation and gut toxicity. | [69,189,190,191,202,209,210,211,212] |

| Ketogenic / very low-carb diet | May reduce abundance of fiber-dependent commensal; some increase in protein/fat metabolizers, increases total anaerobic microflora and counts of Bacteroides. Starves Candida of carbs. | [202,213,214,215] |

| Intermittent Fasting / Caloric restriction | Enriches beneficial taxa – fasting has been shown to increase Akkermansia muciniphila and other mucin-degraders. Also boosts Ruminococcaceae and SCFA output when refeeding occurs. Possibly favors fungal commensal balance, not a clear signification has been shown. | [98,192,193,194,212,216,217] |

| Prebiotic/Supplement | Microbial Implications | Key Refrences |

| Inulin, FOS | ↑Bifidobacterium, ↑Lactobacillus, and ↑Faecalibacterium prausnitzii – associated with better ICI responses. | [186,219,220,227,228] |

| Resistant starch | Ruminococcus bromii, ↑Eubacterium rectale(116); ↑overall SCFA levels which enhance cytotoxic T-cell function. | [78,155,218,229] |

| Polyphenols | ↑Lactobacillus and ↑Akkermansia ↓Enterobacteriacea. These shifts correlate with reduced tumor growth in preclinical studies. | [69,202,203,221,230] |

| Vitamin D | ↑Lachnospiraceae and ↑Ruminococcaceae after supplementation. Also associated with ↑Prevotella and ↑Alistipes in some studies – these genera have been linked to responders. | [78,100,226] |

| Butyrate | Directly provides SCFA to host – can compensate for lack of Faecalibacterium/Roseburia. Butyrate in the colon expands Tregs but also can boost CD8⁺ T-cell memory. | [69,155,231,232] |

| β-glucan | Not a prebiotic but a biotic that activates immunity. Still, it may subtly shift microbiota by enhancing pathogen clearance. In mice it can increase Bacteroidetes and decrease Proteobacteria. | [148,149,150,151,152,155,224] |

| Probiotic Organism | Relevance to ICI Outcomes | Key Refrences |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Enriched in responders. Stimulates mucosal immunity and dendritic cell activation. Under development as a therapeutic. May not help if patient already has high baseline Akkermansia (excess could erode mucus). | [24,95,98,117,239,240] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Associated with favorable outcomes. Produces butyrate, fostering regulatory immune balance and potentially enhancing CD8 T-cell function via metabolic support. Strict anaerobe, challenging to deliver alive. Being formulated in some consortia. Might protect against colitis. | [186] |

| Bifidobacterium longum and B. breve | Shown to enhance anti–PD-L1 therapy in mice [21] by increasing dendritic cell activity and CD8 infiltration. Some human data suggest higher bifido is beneficial. Available in some supplements, but typical doses may not colonize effectively in adults. Next-gen products might include specific immunostimulatory bifido strains. | [98,100,101] |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Required for CTLA-4 response in preclinical models (induces Th1 and maturation of dendritic cells in lymph nodes). Some responder microbiomes are high in Bacteroides. Could be part of a cocktail; mono-strain probiotic use would need caution as Bacteroides can cause infection in frail patients – hence likely delivered as part of a controlled mix. | [105,155] |

| Saccharomyces boulardii | Not yet studied in ICI patients but widely used to prevent antibiotic-related dysbiosis. Produces factors that inhibit pathogens and possibly modulate macrophage cytokines. Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii probiotics that secrete miniature anti-PD-L1 checkpoint proteins can be orally delivered to gastrointestinal tumors, where they reduced tumor burden and reshaped immune and microbiome profiles in an ICI-refractory colorectal cancer mouse model, demonstrating a modular, customizable platform for targeted GI cancer therapy. Generally safe except in critically ill. Could be given during antibiotic courses to preserve microbiome and prevent Candida overgrowth. | [236,237,238] |

| FMT Donor Microbes (examples) | Role in Recipient after FMT | Key Refrences |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Engrafts and increases mucosal immunogenicity, linked to improved T-cell responses and sensitivity to PD-1 blockade. In responder-to-patient FMT, Akkermansia often blooms in recipients whose baseline microbiome lacked it. Its presence post-FMT associated with re-sensitization to therapy. | [24,27,94,95,242,245,247] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Drives anti-inflammatory milieu in gut, yet systemically its metabolite butyrate can boost CD8 T cells. Post-FMT increase of Faecalibacterium correlated with reduced colitis and possibly better tumor control. Key butyrate producer; often depleted in antibiotic-treated or ICI-failing patients and restored by FMT. It also indicates overall gut health. | [25,26,242] |

| Ruminococcaceae spp. | Contribute to sustained engraftment of a diverse anaerobic community; produce SCFAs and modulate Tregs/Th17 balance. Higher Ruminococcus post-FMT was observed in responders. Broadly reflects restoration of diversity. Some specific members might enhance antigen presentation indirectly via metabolite cross-talk. | [27,242,247] |

| Bacteroides spp. | Some donors have high Bacteroides; these can take hold in recipients and have been linked to favorable immune changes. Bacteroides can also help exclude enteropathogens. Need to monitor, as overabundance might cause diarrhea in some cases. | [242,247] |

| Overall diversity | The cumulative effect of FMT is to greatly expand microbial diversity in the recipient. High diversity is consistently associated with better ICI outcome. Diversity is likely to ensure multiple pathways of immune stimulation are intact. FMT donors tend to have richer microbiomes than cancer patients who have been heavily treated with antibiotics. | [27,242,248] |

| Candida spp. | Interesting case: FMT also transfers the donor’s mycobiome. C. albicans was detected in donors and subsequently in the patients – but the patients responded to therapy. The role of fungal transfer is unclear; ideally, donors lack overt fungal overgrowth. Donor screening currently focuses on bacteria, but perhaps selecting donors with balanced fungal communities could be beneficial. The ideal FMT would correct bacterial and fungal dysbiosis together. | [26,27,156] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).