1. Introduction

High performance athletes operate in environments that require them to make quick decisions by observing, analyzing, and adapting to environmental information to choose an action option that meets the demands of each competitive situation [

1]. These actions are mediated by cognitive functions, which allow individuals to respond and adapt to their environment [

2]. Among these functions, attentional capacity, processing speed, cognitive flexibility [

3], and decision-making [

4] have been proposed as functional metrics for cognitive performance.

Studies have shown that individuals who practice high-performance sports exhibit efficient executive functioning, particularly in processes such as the efficiency of attentional networks [

5], processing speed [

6], cognitive flexibility [

7], and decision-making [

8]. However, although athletes tend to show more efficient cognitive functioning, their executive performance may vary depending on the specific cognitive demands imposed by the sporting context, which generally require constant adaptation in attention and decision-making [

9,

10].

For effective decision-making in sports, athletes must attend to multiple concurrent stimuli and activities. The minimal form of multitasking, dual-tasking, involves the simultaneous execution of two tasks, requiring coordinated attention and cognitive resources to maintain parallel processing streams [

11]. Research on dual-tasking largely focuses on the measure to which simple tasks interfere with each other during concurrent execution [

12].

Interference between tasks is defined as performance decreases in one or both tasks compared to their execution separately. This phenomenon is quantified as the

Dual-Task Effect (DTE), where a negative DTE indicates a deterioration in performance and a positive DTE indicates a relative improvement [

13]. The DTE in a dual-task is often quantified as longer reaction times in one or both tasks, an increased number of errors, decreased accuracy, and alterations of behavioral variables [

14]. Note that these metrics quantify DTE as deviation of performance, typically calculated as point measures—such as an average reaction time or total errors over a trial—rather than as a continuous, moment-to-moment assessment.

Classical studies have attributed the DTE to the Psychological Refractory Period (PRP), which occurs when two stimuli are presented in rapid succession and responses to the second are delayed if the interval between stimuli is short [

12]. Temporal overlap is also a strongly explanatory factor in DTE contexts, as not only the difficulty of the tasks generates performance interference but also when and how those tasks are combined [

15]. Classical multitasking models have explained dual-task interference from two main perspectives. The bottleneck model proposes that there are specific processing stages that cannot be executed in parallel, so two tasks must be processed sequentially by the same central mechanism [

12]. On the other hand, the shared resources model suggests that the mind has limited resources that must be divided among concurrent tasks, generating interference when demand exceeds available capacity [

16].

Diverse approaches have been used to evaluate dual-tasking. One of the most employed is the Trail Making Test B (TMT-B), which assesses task switching by sequentially connecting numbers and letters [

17], and has been widely applied in athletic populations [

18]. Based on this test, adaptations such as the Trail Walking Test (TWT) have been developed, in which participants perform the task while walking [

19], and other variants that incorporate concurrent motor demands [

20]. In these paradigms, DTE is analyzed as a decrease in performance in terms of time and attentional quality.

This interference can lead to differences in the quality of attention. Attentional quality reflects the efficiency and stability of attentional systems to filter relevant information and inhibit distractions, allowing for task-relevant processing [

21].

When making a decision, the process of selective attention filters relevant stimuli. These are preferentially processed over distractions [

22] and produce increased

attentional gain, understood as the amount of attentional resources allocated to a specific task [

23]. This gain can amplify overall perceptual system activity, although it does not necessarily increase processing selectivity [

24]. To optimize performance under high-demand conditions, the cognitive system relies on

attentional focus, which promotes the selectivity and precision with which allocated cognitive resources are applied to task-relevant information [

25].

Furthermore, cognitive flexibility has been described as a central function in dual-tasking [

26]. During dual-tasking, the cognitive system regulates balance between maintaining focus on a primary task and being prepared to respond to a secondary task when necessary, even under pressure conditions [

27]. In parallel, attention is also divided between tasks, which involves a redistribution of cognitive resources that may be reduced in each of them [

28].

Given that most sports require dividing attention among multiple stimuli, single-task tasks do not adequately capture the nature of sports performance. Dual-task paradigms allow for observing how cognitive resources are distributed when demand exceeds attentional capacity. However, there is scarce evidence on the use of attentional control in sports contexts, and attentional gain and focus have hardly been quantified in athletes through tasks specifically designed for this purpose.

In this context, dual-task paradigms represent a key tool for studying how athletes distribute attentional resources and regulate interference between concurrent tasks. The simultaneous performance of a continuous visuomotor tracking task and a stimulus-response attentional vigilance task allows for evaluation of both the allocation of cognitive resources (attentional gain) and the quality of processing and filtering of relevant information (attentional focus), as well as the interference effects derived from competition for shared resources or structural bottlenecks.

Based on this framework, we developed a dual-task protocol combining the mentioned tasks to evaluate how high-performance athletes coordinate attention, inhibit distractions, and maintain performance under concurrent cognitive demand.

We aim to evaluate athletes’ attentional gain and focus through determining the DTE as an expression of performance interference during dual-tasking. In this sense, we can understand DTE not only as a global phenomenon but also as the accumulated expression of interferences that emerge in perceptual, decision-making, motor planning and execution stages of cognitive processing. In turn, we expect the temporal analysis of behavioral performance to enable the study of dual-task interference throughout time: from early perception stages to later decision and response phases.

Based on the objective of this task, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.- The simultaneous execution of the visuomotor tracking task (T1) and the attentional vigilance task (T2) will generate a negative Dual-Task Effect, evidenced by a decrease in performance in the tracking task. H2.- The latency and duration of the Dual-Task Effect will vary depending on the load imposed by the secondary task, reflected in different levels of visuomotor performance deterioration during concurrent execution. H3.- The Dual-Task Effect will present distinct temporal dynamics for different stages of processing, observable through shifts in behavioral execution. H4.- The time windows for distinct dynamics will show different interference for independent procesing stages.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study employed a cross-sectional, within-subject experimental design with repeated measures. Thirty-six participants voluntarily performed the experimental protocol. All participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. A dual-task paradigm combining continuous visuomotor tracking and an attentional vigilance task was implemented to assess dual-task interference by comparing task performance across multiple time windows relative to task-relevant events. Event-locked behavioral responses were analyzed to characterize the temporal dynamics, latency, amplitude, and duration of the dual-task effect.

The dual-task computational protocol was executed with the use of a mouse and a 1920x1080 pixels computer screen, at a distance of approximately 60 cm from the participant. The experimental protocol was implemented using PsychoPy [

29]) following the methodological principles described by [

30]. Participants were presented with a gray screen (RGB: 128,128,128) where they had to perform two tasks simultaneously:

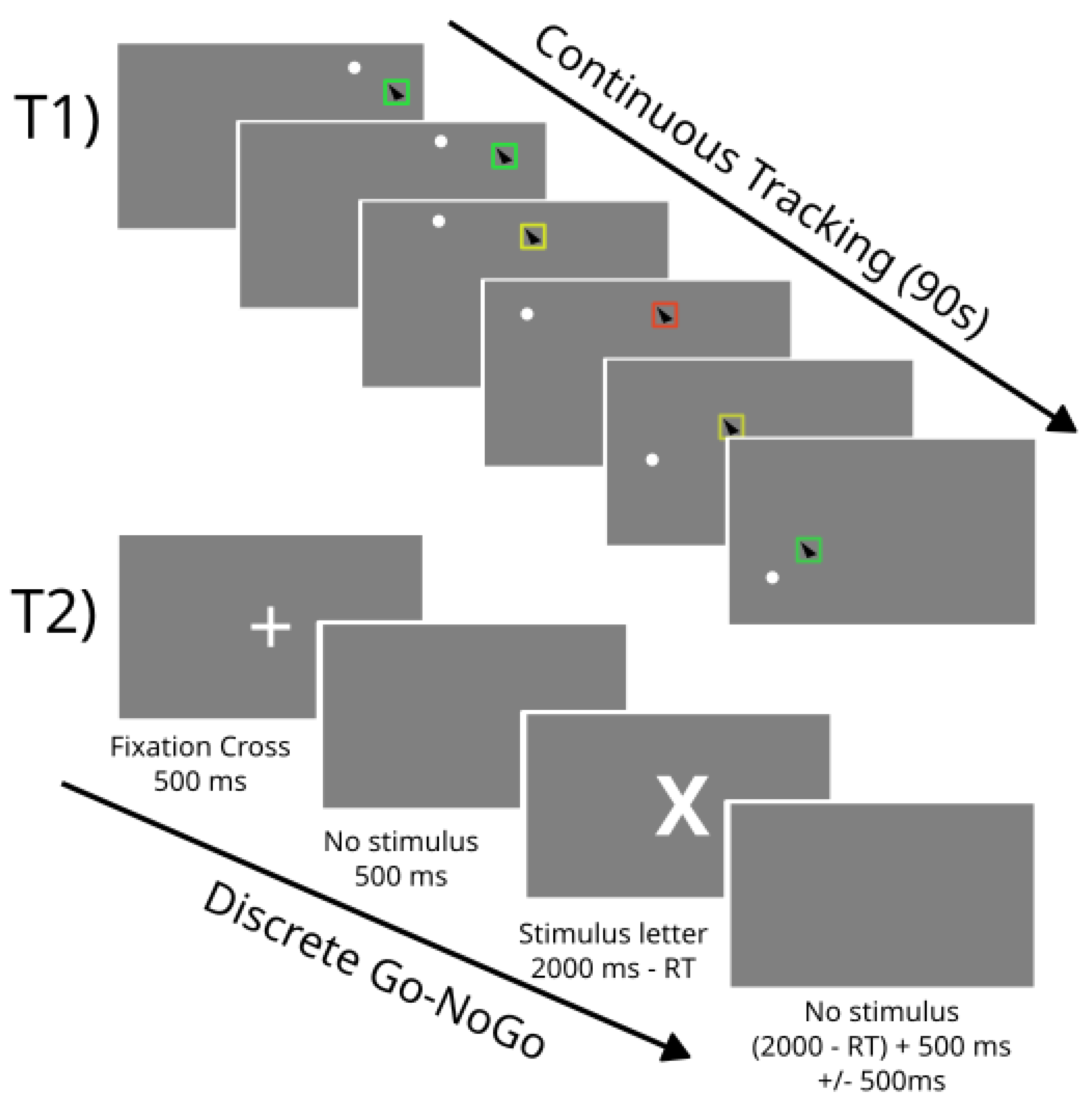

Task T1 was a continuous tracking task where participants used a mouse to track and follow a 10px moving target on a computer screen with the cursor. They received visual feedback in the form of a colored rectangle around the cursor, which changed color based on the distance from the cursor to the target (green for close, yellow for moderate distance, and red for far). The target trajectory was determined by a random direction vector with a constant speed of 15 pixels per frame, updating at a rate of 20 frames per second. The direction vector was altered with a 20% probability at each frame, introducing variability in the target’s movement. When the target reached the screen boundaries, it reflected off the edge, maintaining its speed but changing direction accordingly. The performance metric for T1 was defined as the distance to the target calculated as the Euclidean distance between the cursor and the target positions on the screen.

Task T2 was a letter Go/NoGo task where participants had to respond to the letter "X" (Go) by pressing the left mouse button and withhold their response for other letters, "M", "N", "Y", "A", "U", "H" (NoGo). Letters were presented randomly on the screen at intervals of 2 seconds with a random jitter of ±0.5 seconds. Participants performed six blocks of the dual-task protocol, each lasting 90 seconds. The performance metrics for T2 consist in the reaction times and accuracies for each trial.

Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of the dual-task experimental protocol.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the dual-task experimental protocol. Participants performed a continuous tracking task T1, while responding to target letters and ignoring non-target letters from task T2. A rectangle around the cursor provided feedback on the distance to the target in T1, changing color based on proximity (green, yellow, red). Letters were presented every 2 seconds with a jitter of ±0.5 seconds.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the dual-task experimental protocol. Participants performed a continuous tracking task T1, while responding to target letters and ignoring non-target letters from task T2. A rectangle around the cursor provided feedback on the distance to the target in T1, changing color based on proximity (green, yellow, red). Letters were presented every 2 seconds with a jitter of ±0.5 seconds.

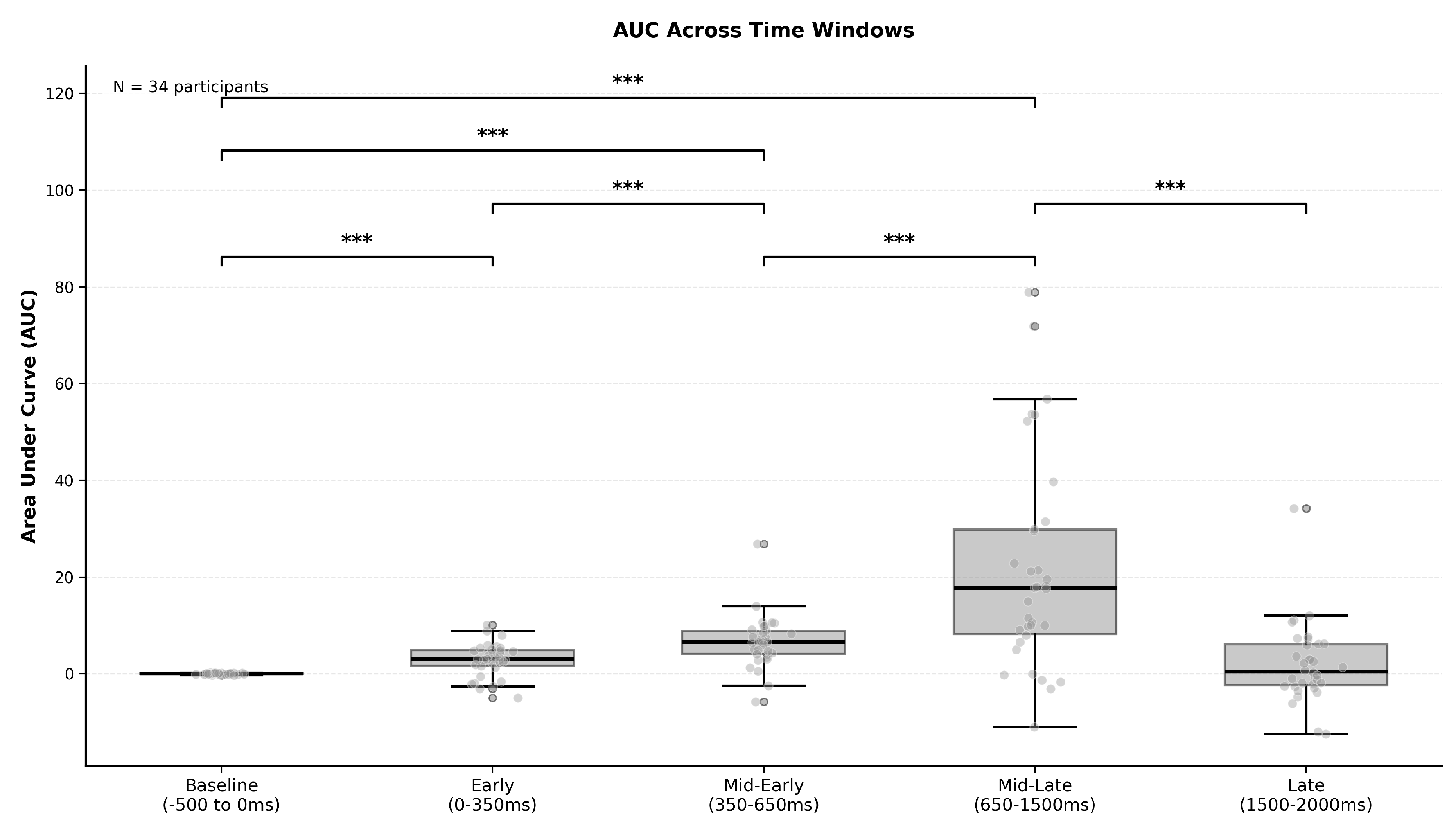

Figure 2.

AUC of the ERBP waveform in four different time windows after T2 stimulus onset compared to the 500ms baseline.

Figure 2.

AUC of the ERBP waveform in four different time windows after T2 stimulus onset compared to the 500ms baseline.

For every T2 event, the corresponding performance metric data from T1 was extracted in a time window from -500 ms to +2000 ms relative to the event onset: The stimulus letter. Linear interpolation was used to align the event onset with the continuous performance metric. The performance data from the baseline time window (-500 ms to 0 ms) were used to calculate a baseline performance for each event. The performance data were then baseline-corrected by subtracting the average performance from the entire time window. This process, similar to event-related potential (ERP) analysis in EEG research [

31], allowed us to isolate the changes in distance related to T2 events. We refer to these as event-related behavioral potentials (ERBPs).

3. Results

Participant ages ranged from 13 to 28 years (M = 16.58, SD = 3.92). Of these, 20 were females (55.6%). Participants from seven different sports were included, which were later grouped into two sport groups: interceptive (n = 22; 61.1%) and static (n = 14; 38.9%).

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Average accuracy for all participants in T2 was 77.01% (SD = 30.92) and the response time was 594ms (SD = 146ms).

The performance metric for T1 was evaluated grouped in five temporal windows: Baseline (-500 to 0 ms), Early (0 to 350 ms), Mid-Early (350 to 650 ms), Mid-Late (650 to 1500 ms), and Late (1500 to 2000 ms) relative to T2 event onset. Participants’ average AUC for each time window were tested using a Friedman test, followed by post-hoc pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni correction.

A Friedman test revealed significant differences in AUC values across the five time windows (

(4) = 85.32, p < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.595). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni correction indicated significant differences between all the time windows between 0 and 1500 ms, but not between the late window (1500-2000 ms) and the baseline. Detailed results of the pairwise comparisons, including effect sizes, are presented in

Table 2.

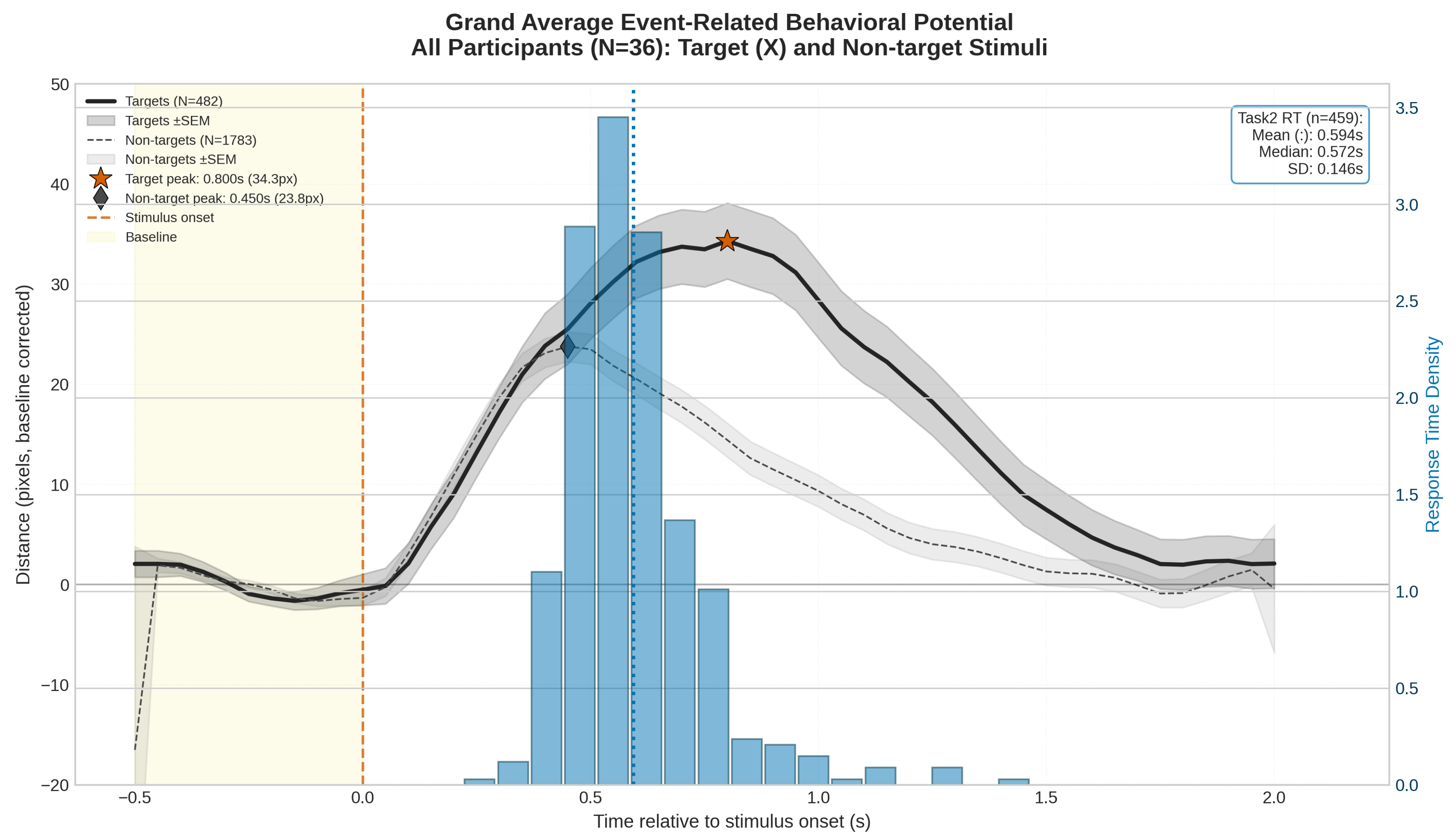

3.1. Event Related Behavioral Potentials

For a more detailed evaluation of time-locked behavioral responses to T2 events, we computed the grand average ERBP waveforms across all participants. The maximum peak was identified in the grand average ERBP waveform within a time window of 0 ms to 2000 ms after the event onset.

Figure 3 illustrates the grand average ERBP waveform for target and non-target events, including a histogram of the response times for T2. Target events elicited a pronounced increase in distance and latency compared to non-target events. With a difference in peak latency of 350 ms and a difference in peak amplitude of 10.5 px between target and non-target events.

The difference between target and non-target ERBP suggests a split of the DTE into two components: an early component around 450 ms post-event, likely reflecting perceptual processing interference, and a later component between 450 and 1400 ms, likely associated with decision-making, motor planning, and execution interference.

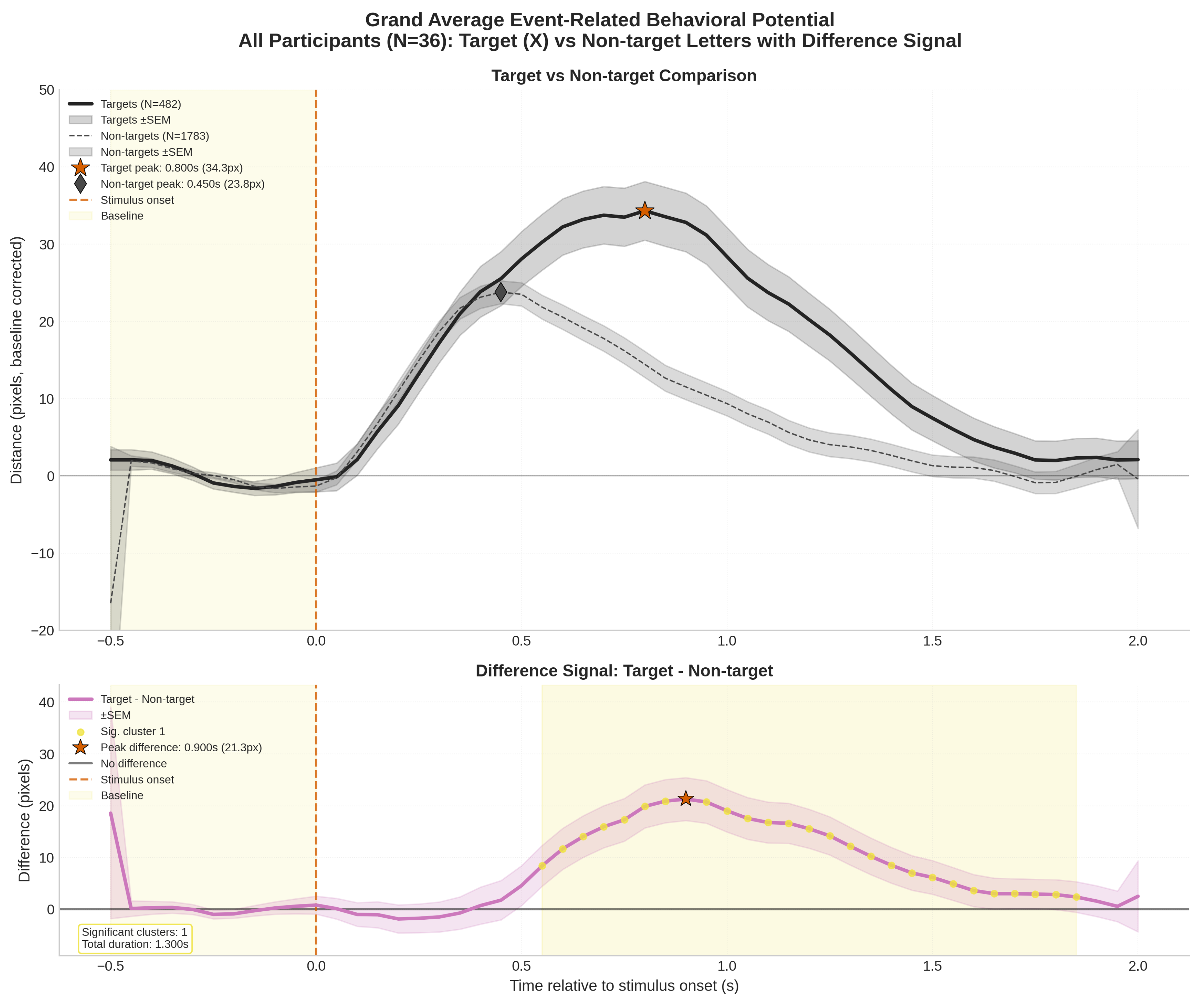

By subtracting the non-target ERBP from the target ERBP, we obtained the difference waveform shown in the lower panel of

Figure 4. A cluster permutation test was executed to evaluate relevant timepoints where the waveform significantly differ from the baseline. It revealed a significant cluster (p < 0.001) between 500 ms and 1400 ms after event onset, indicating a significant increase in distance to the objective being tracked in Task 1 during this time window: A dip in the performance metric reflecting the DTE.

3.2. Exploratory analysis: Sport Group Comparison

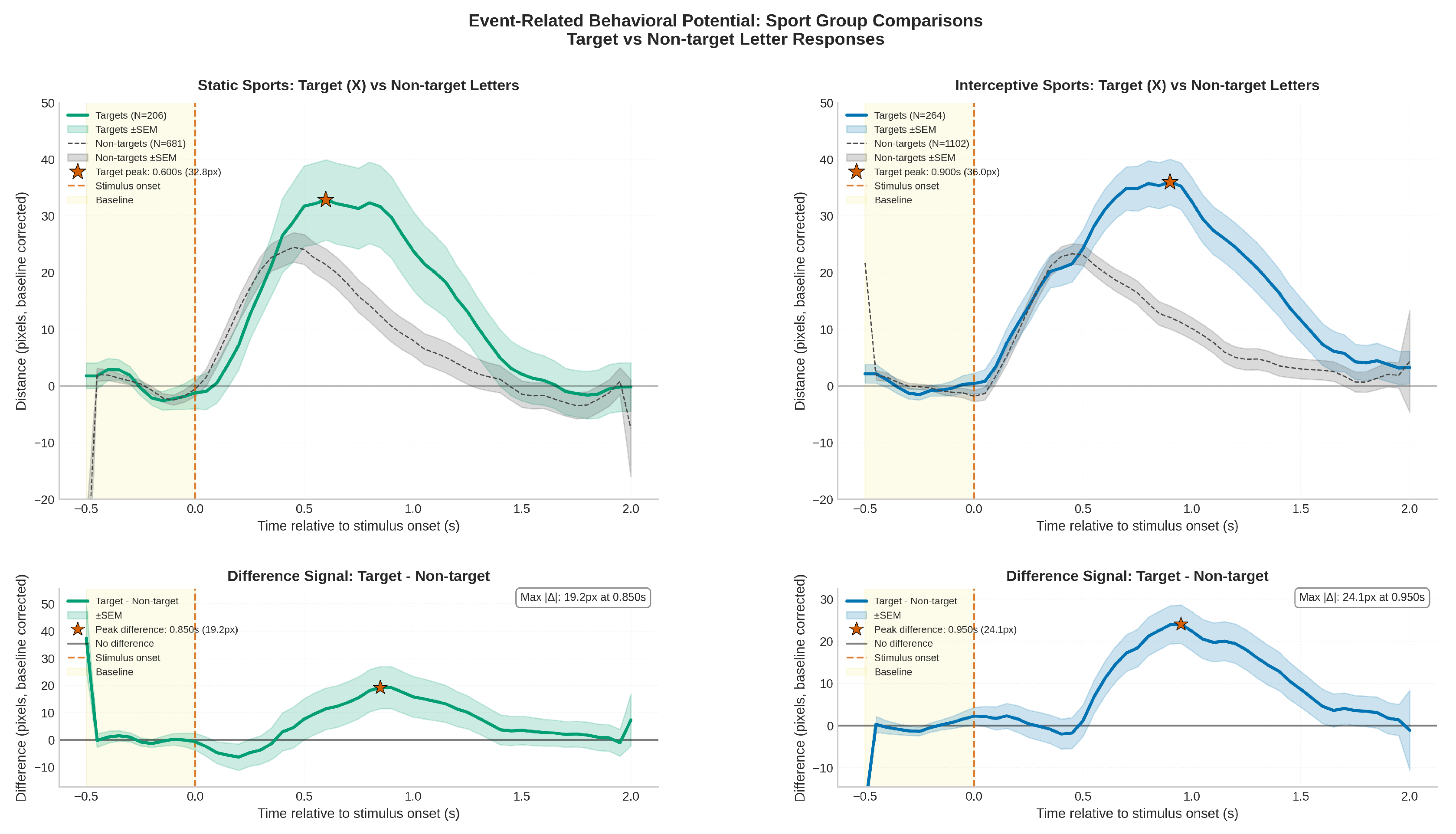

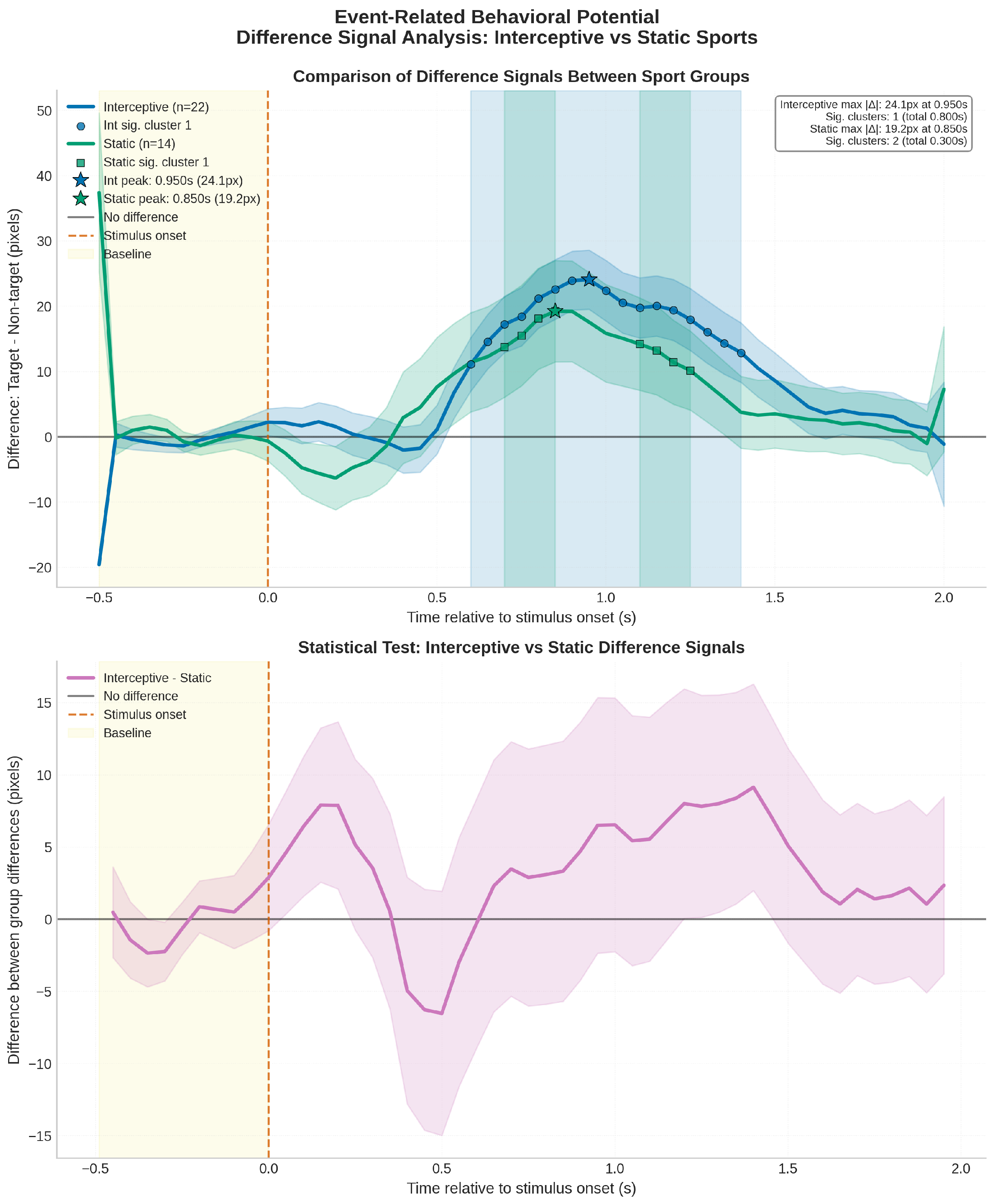

To investigate possible trends and relevant time windows in dual-task interference, we compared the ERBP waveforms of the interceptive and static sport groups.

Figure 5 displays the grand average ERBP waveforms for both sport groups, with target and non-target events. Just as in the overall analysis, target events elicited a pronounced increase in distance and latency even after subtracting the non-target waveform.

Figure 6 illustrates the difference signal between both of the sport groups’ difference waveforms (target minus non-target). Although both sport groups exhibited a DTE, cluster permutation tests revealed no significant clusters deviating from the baseline when comparing the two sport groups to each other. However the difference wave between sport groups shows a trend where the static sport group appears to experience a less pronounced DTE compared to the static sport group, except for a brief period around 500 ms post-event.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was the development and implementation of a dual-, visuomotor-tracking-, and attentional-vigilance-task designed to evaluate how high-performance athletes coordinate attention, inhibit distractions, and maintain performance under concurrent cognitive demand. The developed task aimed to examine how the simultaneous execution of a continuous tracking task and an attentional vigilance task affects athletes’ behavioral performance, as well as to characterize the temporal dynamics of dual-task interference through a behaviorally event-related approach.

4.1. Temporal Dynamics of Dual-Task Interference

A significant Dual-Task Effect (DTE) was observed in the studied population, characterized by an increase in distance to the target in Task 1 (T1) following target events in Task 2 (T2), with performance returning to baseline approximately 1500 ms after the event. These results indicate that the introduction of a discrete attentional demand induces transient interference in continuous visuomotor performance. The accuracy rates obtained in T2 were lower than those reported by [

32], who found a correct response percentage of 97.8% in a similar continous performance task, while reaction times were higher than those reported by [

33], who described a mean reaction time of 317 ms in a comparable Go/NoGo task. Those observations were made under single task conditions. This pattern suggests that the concurrent task demands imposed by the dual-task paradigm increased cognitive load and response uncertainty.

The present study also investigated the cognitive-motor performance of young athletes from interceptive and static sports using a dual-task protocol. Our results are consistent with previous evidence documenting dual-task interference in paradigms combining continuous tasks with discrete executive demands. In particular, [

34] demonstrated that serial temporal gait velocity and stability were negatively affected when performed concurrently with executive tasks involving inhibition, updating, or switching, generating a bidirectional Dual-Task Effect. Similar to our findings, the authors observed that interference is not uniform but depends on attentional resource allocation and the nature of the cognitive process involved.

Borrowing methods from ERP analysis, we computed ERBPs to examine, visualize, and test time-locked behavioral responses to T2 events. The ERBP analysis allowed for the identification of distinct temporal components of the DTE, as well as statistical quantification of distinct time windows with respect to baseline. Evaluating the performance metric in those time windows allowed us to quantify the extent and duration of dual-task interference. A clear temporal division of the DTE was observed by comparing target and non-target ERBPs. Target events elicited a pronounced increase in distance and latency compared to non-target events, with a difference in peak latency of 350 ms and a difference in peak amplitude of 10.5 px between target and non-target events. This indicates that the performance metric is sensitive to the decision-making process, even if there is no motor response required for T2. The difference waveform between target and non-target ERBPs suggests a behavioral interference DTE, with a component associated with motor planning and execution.

Exploratory studies comparing ERBP waveforms between sport groups revealed trends suggesting that, by contrasting participants with training in diverse cognitive strategies, critical time windows of dual-task interference may emerge. Although no significant differences were found between sport groups, the static sport group appeared to experience a less pronounced DTE compared to the interceptive sport group, except for a brief period around 500 ms post-event. This trend could indicate a time window after perceptual encoding where athletes with specific training may experience less interference, possibly due to enhanced attentional control or resource allocation strategies developed through their sport-specific training.

4.2. Adaptation Through Resource Redistribution

When dual-task demands exceed cognitive capacity, resources are redistributed between primary and secondary tasks. The efficiency of this redistribution has been shown to be influenced by the athletes’ sport-specific cognitive control strategies and limited cognitive capacity [

35]. Time pressure plays a crucial role in this model, as participants had a limited window to respond. This mirrors the time constraints athletes face when executing motor actions or making decisions during competition [

1].

Similar to our findings, [

27] demonstrated that attentional flexibility and stability do not always increase or decrease in tandem. An individual may maintain a constant focus on the primary task while being inflexible in detecting the secondary task, or vice versa. This suggests that attention and its control are not unitary constructs; rather, the mind adapts its strategy based on situational demands. In sports like modern pentathlon (one of the disciplines evaluated), this adaptability is crucial, as athletes must frequently shift their focus or sustain it over extended periods while inhibiting distractions.

According to [

12], interference occurs when tasks share sensory perception and response processes, leading to conflict when both demand similar resources. This could suggest a content-based interference model. We contend that, the dual-task paradigm serves as a "controlled cognitive stressor," revealing deficits or strengths not observable under single-task conditions.

4.3. Continuous Assessment of DTE

There have been approaches considering a time continuum as an important element in establishing a DTE. While [

34] characterized the DTE primarily based on global changes in performance variability and accuracy, the current approach allows for decomposing dual-task interference into differentiated temporal components aligned with specific behavioral events. In this sense, the analysis of Event-Related Behavioral Potentials (ERBP) extends these findings by showing that interference emerges in specific temporal windows following relevant events from the secondary task, suggesting the coexistence of early perceptual and late decisional components of the DTE.

The DTE is the performance cost of performing two concurrent tasks [

12]. Previous studies have expressed DTE in terms of task execution speed [

20], accuracy in both tasks [

36], and reaction times [

12]. In this work, we identified properties of the DTE that had not been previously defined, stemming from the use of a continuous performance variable for temporal processing in concurrent tasks.

We were able to identify characteristics of the DTE such as Amplitude, Latency, and Duration in different temporal windows. Defining characteristics of this nature allows us to observe different execution patterns, explaining how the DTE can vary among individuals and even identifying the influence of sport type on it [

13]. Here, the amplitude of the DTE is expressed using the distance in pixels to the target over time. This continuous performance measure allows us to evaluate changes in the DTE over time with previously inaccessible precision. Thanks to the explored methodology, we can identify the latency of the DTE, seen as the time it takes for a significant decrease in performance of Task 1 to appear after the stimulus of Task 2. In PRP dual-task paradigms, the latency of the response to the second task (T2) systematically increases as the stimulus interval decreases, reflecting temporal interference in the response selection stage due to central processing limitations [

16]. Unlike previous works, we can clearly establish the moment when the significant decrease in performance of a continuous task begins. Duration of the DTE can be measured as the length of the cluster significantly different from baseline around the maximum interference in the time-locked signal of the performance metric. This measure has been previously explored in ecologically valid conditions, such as dual driving tasks where the DTE could persist for more than 10 seconds after the concurrent event [

37]. This supports the idea that temporal measures like DTE duration are critical behavioral dimensions for characterizing how interference manifests and resolves in dual-task paradigms.

According to the results obtained, we can identify that the DTE can be decomposed into characteristics such as Amplitude, Latency, and Duration of the DTE in different temporal windows. We were able to measure the amplitude, latency, and duration of the DTE, as well as some of its temporal components, allowing us to identify specific characteristics of interference between tasks. Based on these characteristics, functional criteria were established for selecting explanatory models of the DTE, depending on how athletes allocate and redistribute their attentional resources under concurrent demand.

4.4. Aligment with Multitasking Models

Traditional multitasking models, such as the bottleneck model [

12] and the shared resources model [

16], posit that interference can originate either from a structural limitation in a central processing stage or from gradual competition for limited cognitive resources, respectively [

38]. The dual-task developed in this study allows for empirical distinction between both mechanisms, as the latency and duration of the DTE are consistent with a central bottleneck when interference manifests as a well-defined temporal delay, while sustained performance reduction and changes in DTE amplitude are more compatible with a shared resources model. This approach aligns with contemporary proposals suggesting that different types of dual-task interference may require differentiated explanatory models, depending on the temporal dynamics and cognitive load of the tasks involved [

16].

Due to the temporal characterization of the DTE, functional criteria can be established to infer characteristics of the compatible models of the observed effects. Since the movement of the T1 tracked objective is a random variable of known distribution, non-action from the participant will lead to a predictable increase in distance to the target over time. This produces a decrease in the performance metric over time. The expected decrease in this distribution is proportional to the distribution of the target movement speed and represents a state of resources being fully relocated from T1 to T2. This aligns with the bottleneck model [

12], where both tasks compete for a central stage, generating a transient delay, manifested as a temporal displacement of performance rather than sustained degradation. In contrast, a change in the rate of increase of the distance waveform represents a measurable partial allocation of resources from T1 to T2, resulting in a slower performance decrease, which is more compatible with the shared resources model [

16]. This pattern indicates that both tasks are executed partially in parallel, but compete for a limited pool of attentional resources. In this scenario, interference affects the overall quality of performance over an extended time interval.

The dual-task developed in this study allows for empirical distinction between both mechanisms, as the latency and duration of the DTE are consistent with a central bottleneck when interference manifests as a well-defined temporal delay, while sustained performance reduction and changes in DTE amplitude are more compatible with a shared resources model. This approach aligns with contemporary proposals suggesting that different types of dual-task interference may require differentiated explanatory models, depending on the temporal dynamics and cognitive load of the tasks involved [

16].

In the present study, attentional gain was operationalized through global performance costs and DTE amplitude, reflecting the magnitude of resource allocation to concurrent task demands. In contrast, attentional focus was indexed by temporal parameters such as DTE latency, duration, and recovery to baseline, capturing the efficiency and selectivity with which attentional resources were applied and re-stabilized following interference. Given that the amplitude of the DTE reflects how much T1 is affected after a T2 event and that the overall decrease in performance indicates attentional prioritization of the secondary event, we can support [

39] proposal that interference indicates a greater reallocation of resources. This is because relevant events in T2 capture attention and degrade continuous performance [

40]. These responses can be characterized as attentional gain.

Now, understanding that the onset latency of the DTE reflects the moment when interference accesses the central system [

12], the duration of the DTE indicates the stability of focus and the ability to sustain relevant processing [

41], and recovery to baseline performance expresses the ability to reorient attention and inhibit distractions [

21]. It can be understood that these indicators reflect the selectivity of processing and the quality of attentional control, which is broadly related to attentional focus [

25]. In this way, work such as this will enable us to understand how athletes allocate attentional resources to two concurrent tasks and how they regulate their processing and filtering of relevant information, as well as how interference occurs in their attentional states. This information can help athletes, coaches, and sports psychologists develop tools to intervene in their dual-tasking processes. This will result in improved performance and understanding of their own processes.

4.5. Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study is the sample size, as 36 athletes participated, making it difficult to search for significant differences between post-hoc groupings. Another limitation is the age heterogeneity of the participants (13-28 years). While this variability allows for exploring dual-task performance in an ecologically representative sports sample, it limits the generalization of results and reduces statistical power to detect more subtle differences between subgroups. The cross-sectional design of this work prevents establishing causal conclusions about the relationship between sports experience, attentional strategies, and DTE magnitude. The use of specific tasks may represent a limitation, as the results are a product of this combination of demands. Additionally, the absence of parametric manipulation of difficulty in each task limits the possibility of directly evaluating how gradual changes in cognitive demand modulate DTE amplitude and duration.

4.6. Outlook

The usage of time-locked average behavioral responses to characterize dual-task interference turns a reliable research method from the field of cognitive neuroscience to a novel framework for dissecting the temporal dynamics of cognitive-motor performance under concurrent demand. This approach can be extended to investigate how different cognitive domains (e.g., working memory, inhibition, task switching) interact with continuous behavioral tasks, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of cognitive resource allocation in complex environments. By characterizing statistically significant time windows of interference, future research may explore precisely timed interference effects for different cognitive processes, characterizing inter-individual differences and their relationship to performance, and aiding the management of cognitive demands for individuals in environments with multiple simultaneous demands. Trends between sport groups hint at task sensitivity to different phases of perception, cognition, and motor execution, which could in turn be helpful mechanisms to understand mental strategies implemented by participants as they solve the task. Future research, incorporating larger sample sizes from diverse populations, could further illustrate how sport-specific training influences dual-task performance and its temporal dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the utility of a dual-task protocol combined with ERBP analysis to investigate cognitive-motor performance. An example was presented including young athletes with different sport backgrounds. The observed DTE and its temporal components provide insights into the cognitive processes underlying dual-task interference: showing significant performance interference during simultaneous task execution. This approach offers a promising methodology for future research into cognitive-behavioral interactions and the effects of multiple objectives on behavioral task performance, and serves as a foundational example on the combined study of attention as continuous and discrete cognitive variables in experimental psychology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.C., A.G.R., and L.C.G.; methodology, A.B.C. and A.G.R.; software, A.B.C.; validation, A.B.C. and A.G.R.; formal analysis, A.B.C.; investigation, A.B.C., A.G.R, E.V. and L.C.G ; resources, A.G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.C. and A.G.R.; writing—review and editing, A.B.C., A.G.R., E.V., L.C.G.; visualization, A.B.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Psychology Institute of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León (FP-UANL-25-011, 18/08/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study, and their written informed consent has been obtained to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This study was partly enabled with the support of the Research Abroad Grant from the Graz University of Technology. During the preparation of this study, the authors used Github Copilot for the purposes of software development, data analysis, and text manipulation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gómez Rosales, A.d.J.; Morquecho Méndez, A.; Ródenas Cuenca, L.T. Memoria de trabajo y control inhibitorio en beisbolistas universitarios. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación 2021, 939–946. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, J.; Matthaeus, L. Athletics and Executive Functioning: How Athletic Participation and Sport Type Correlate with Cognitive Performance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2014, 15, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestberg, T.; Reinebo, G.; Maurex, L.; Ingvar, M.; Petrovic, P. Core Executive Functions Are Associated with Success in Young Elite Soccer Players. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0170845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, Y. Differences in Executive Function of the Attention Network between Athletes from Interceptive and Strategic Sports. Journal of Motor Behavior 2021, 53, 419–430, [32654658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoubi, S.; Behgam, N.; Sadeghi-Bahmani, D.; Heidari, H.; Maghbooli, Z.; Eskandarieh, S. Response Inhibition, Attention and Processing Speed in Male Athlete and Non-athlete Adolescents. Caspian Journal of Neurological Sciences 2024, 10, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, N.E.; Henry, D.A.; Hillman, C.H.; Kramer, A.F. Trained Athletes and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2023, 21, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, M.A.; Kassim, A.F.M.; Miswan, M.S.; Zainuddin, N.F. The Comparison of Decision-Making Skills between Athletes and Non-athletes among University Students. Journal of Human Centered Technology 2023, 2, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongtawee, A.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.; Woo, M. Athletes Have Different Dominant Cognitive Functions Depending on Type of Sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2022, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qizi, Y.D.I. TECHNICAL AND TACTICAL SKILLS IN SPORTS. American Journal Of Social Sciences And Humanity Research 2023, 3, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, S.E. Definition: Dual-tasking and Multitasking. Cortex 2018, 106, 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashler, H. Dual-Task Interference in Simple Tasks: Data and Theory. Psychological Bulletin 1994, 116, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Eskes, G. Measuring Treatment Effects on Dual-Task Performance: A Framework for Research and Clinical Practice. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künstler, E.C.S.; Penning, M.D.; Napiórkowski, N.; Klingner, C.M.; Witte, O.W.; Müller, H.J.; Bublak, P.; Finke, K. Dual Task Effects on Visual Attention Capacity in Normal Aging. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobach, T. Cognitive Control and Meta-Control in Dual-Task Coordination. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2024, 31, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigman, M.; Dehaene, S. Brain Mechanisms of Serial and Parallel Processing during Dual-Task Performance. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 7585–7598, [18650336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cubillo, I.; Periáñez, J.A.; Adrover-Roig, D.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.M.; Ríos-Lago, M.; Tirapu, J.; Barceló, F. Construct Validity of the Trail Making Test: Role of Task-Switching, Working Memory, Inhibition/Interference Control, and Visuomotor Abilities. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2009, 15, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokgöz, O.; Korkmaz, N.; Pancar, S. The Comparison of Trail Making Test Scores of Open and Closed Skill Sports Athletes. The Journal of Eurasia Sport Sciences and Medicine 2021, 3, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Holfelder, B.; Klotzbier, T.J.; Eisele, M.; Schott, N. Hot and Cool Executive Function in Elite- and Amateur- Adolescent Athletes From Open and Closed Skills Sports. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotzbier, T.J.; Schott, N. Skillful and Strategic Navigation in Soccer – a Motor-Cognitive Dual-Task Approach for the Evaluation of a Dribbling Task under Different Cognitive Load Conditions. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarter, M.; Givens, B.; Bruno, J.P. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Sustained Attention: Where Top-down Meets Bottom-Up. Brain Research Reviews 2001, 35, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolari, M.; Byers, A.; Serences, J.T. Optimal Deployment of Attentional Gain during Fine Discriminations. Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32, 7723–7733, [22649250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlin, J.R.; Shahin, A.J.; Miller, L.M. Attentional Gain Control of Ongoing Cortical Speech Representations in a “Cocktail Party”. Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, T.W.; Dixon, M.L.; Anderson, A.K.; De Rosa, E. Distinguishing Attentional Gain and Tuning in Young and Older Adults. Neurobiology of Aging 2014, 35, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G. Attentional Focus and Motor Learning: A Review of 15 Years. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2013, 6, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, I.; Poljac, E.; Müller, H.; Kiesel, A. Cognitive Structure, Flexibility, and Plasticity in Human Multitasking—An Integrative Review of Dual-Task and Task-Switching Research. Psychological Bulletin 2018, 144, 557–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boag, R.J.; Strickland, L.; Heathcote, A.; Loft, S. The Dynamics of Stability and Flexibility: How Attentional and Cognitive Control Support Multitasking under Time Pressure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2025, 154, 1699–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, S.C.; Strayer, D.L.; Matzke, D.; Heathcote, A. Cognitive Workload Measurement and Modeling under Divided Attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 2019, 45, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, J.; Gray, J.R.; Simpson, S.; MacAskill, M.; Höchenberger, R.; Sogo, H.; Kastman, E.; Lindeløv, J.K. PsychoPy2: Experiments in Behavior Made Easy. Behavior Research Methods 2019, 51, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reips, U.D.; Krantz, J.H. Conducting True Experiments on the Web. In Advanced Methods for Conducting Online Behavioral Research; American Psychological Association, 2010; pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, S.J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique, 2 ed.; MIT Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Lopez, J.; Silva-Pereyra, J.; Fernandez, T. Sustained Attention in Skilled and Novice Martial Arts Athletes: A Study of Event-Related Potentials and Current Sources. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, H.; Mori, S. Sport-Specific Decision-Making in a Go/Nogo Reaction Task: Difference among Nonathletes and Baseball and Basketball Players. Perceptual and Motor Skills 2008, 106, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.W.; Collier, S.A.; Night, J.C. Timing and Executive Resources: Dual-task Interference Patterns between Temporal Production and Shifting, Updating, and Inhibition Tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 2013, 39, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boag, R.J.; Strickland, L.; Loft, S.; Heathcote, A. Strategic Attention and Decision Control Support Prospective Memory in a Complex Dual-Task Environment. Cognition 2019, 191, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, K.M.; Shaw, T.H.; Helton, W.S. Evaluating the Dual-Task Decrement within a Simulated Environment: Word Recall and Visual Search. Applied Ergonomics 2023, 106, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuako, P.A.G.; Stojan, R.; Bock, O.; Mack, M.; Voelcker-Rehage, C. Multitasking: Does Task-Switching Add to the Effect of Dual-Tasking on Everyday-like Driving Behavior? Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 2025, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Q. Dual-Task Interference: Bottleneck Constraint or Capacity Sharing? Evidence from Automatic and Controlled Processes. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 2024, 86, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. On the Psychology of Prediction. Psychological Review 1973, 80, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Johnston, W.A. Driven to Distraction: Dual-Task Studies of Simulated Driving and Conversing on a Cellular Telephone. Psychological Science 2001, 12, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Castro, S.C.; Turrill, J.; Cooper, J.M. The Persistence of Distraction: The Hidden Costs of Intermittent Multitasking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 2022, 28, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).